Submitted:

02 January 2026

Posted:

04 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

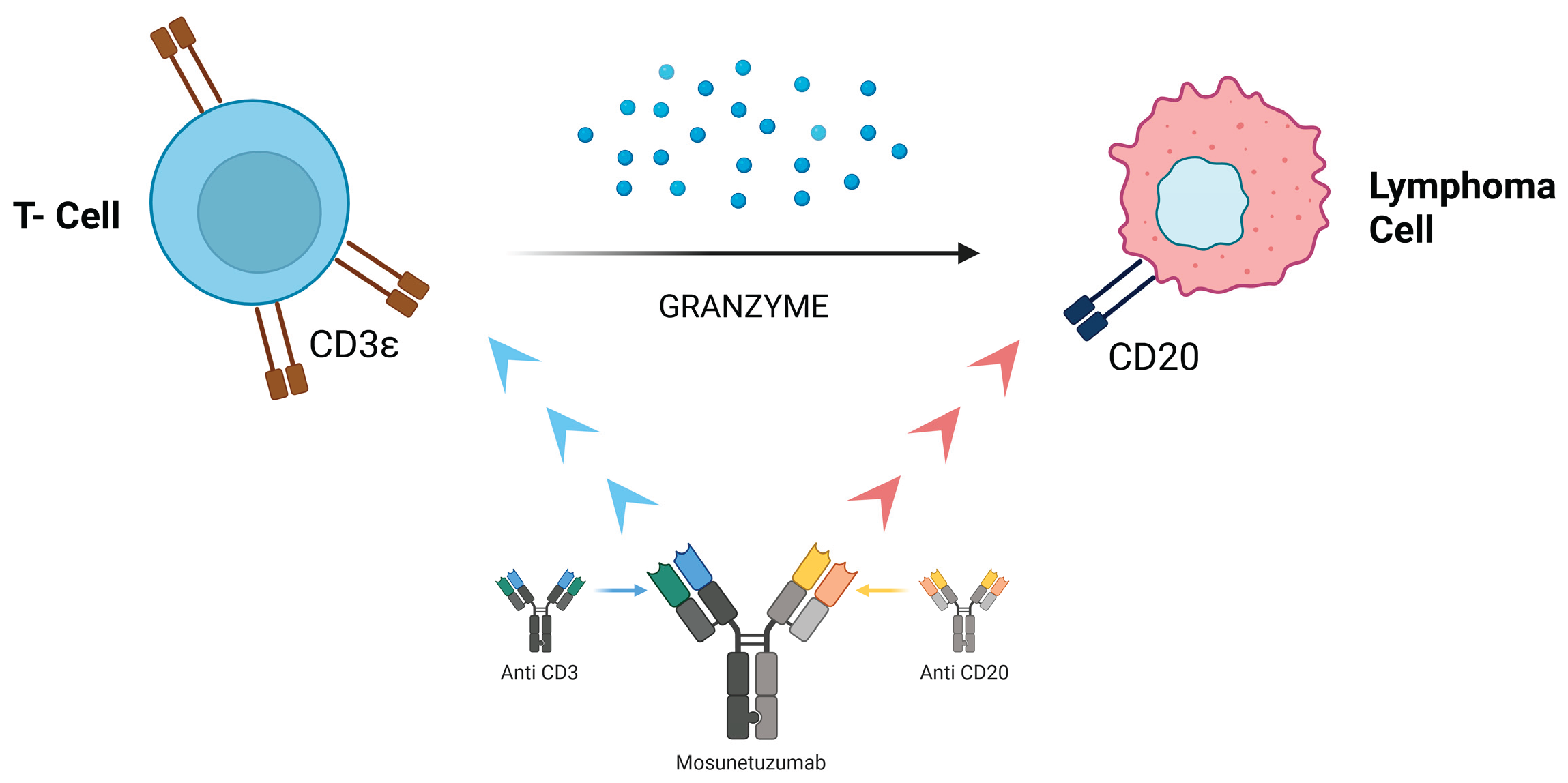

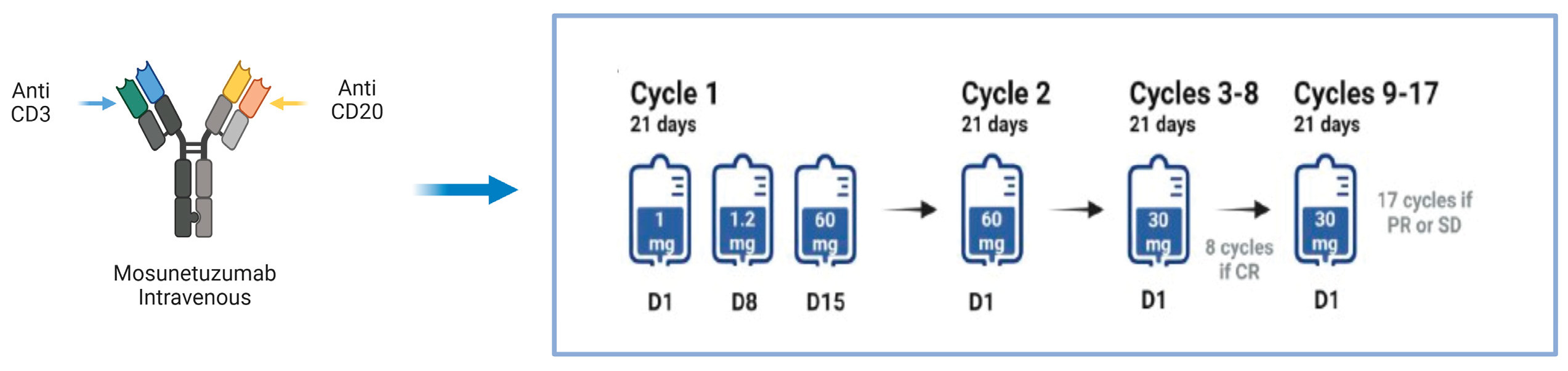

Follicular lymphoma (FL) is the second most common form of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (NHL) and accounts for about 5% of all hematological malignancies. Despite therapeutic advances, FL follicular lymphoma remains an incurable disease, with frequent relapses and increasingly shorter disease control intervals. Bispecific antibodies (bsAbs) are molecules that target two different epitopes or antigens. The mechanism of action is determined by the molecular targets and structure of the bsAbs. Several bsAbs have already changed the therapeutic landscape of hematological malignancies and some solid tumors. In particular, in this article we review the general principles on follicular lymphoma and established and innovative therapies including bsAbs, in particular the bsAb mosunetuzumab, a new bispecific antibody that acts on CD3 epitopes of T lymphocytes and CD20 epitopes of B lymphocytes with the aim of inducing T lymphocyte-mediated elimination of malignant B lymphocytes, its safety and efficacy with the analysis of no. 3 patients who completed treatment with the drug mosunetuzumab in the A.O. Pia Fondazione di Culto e Religione ‘Card. G. Panico’, Tricase (Lecce).

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Follicular Lymphoma

2.1. Clinical Manifestations and Pathological Features of Follicular Lymphoma

2.2. Diagnosis

2.3. Prognosis

2.4. Treatment of FL in Stage I-IV

2.5. Treatment of Relapsed or Refractory Follicular Lymphoma

3. Bispecific Antibodies: Focus on Mosunetuzumab

4. Experience in the “A.O. Card G. Panico”: Patient Cases

4.1. Patient Cases

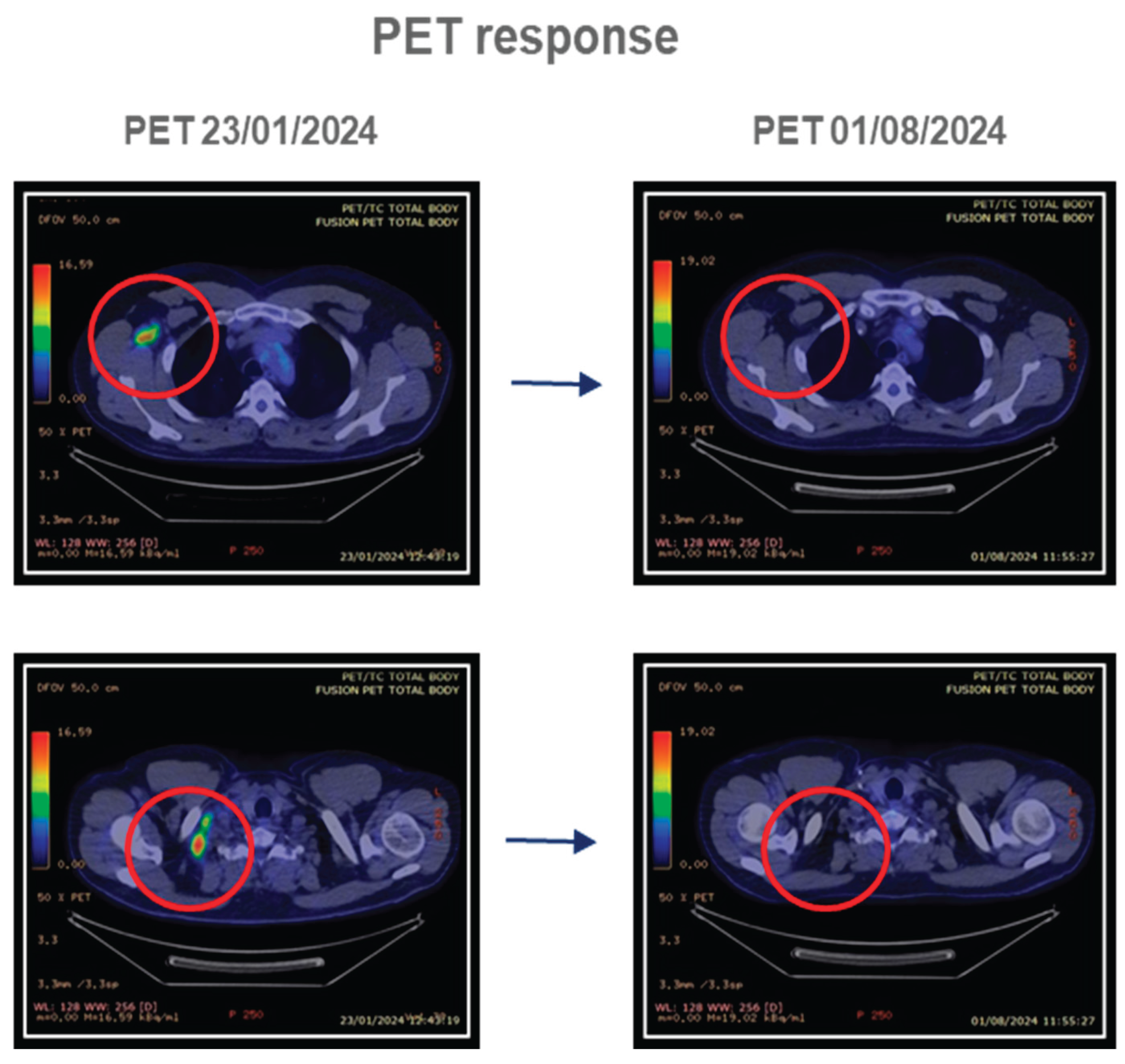

4.1.1. Patient 1

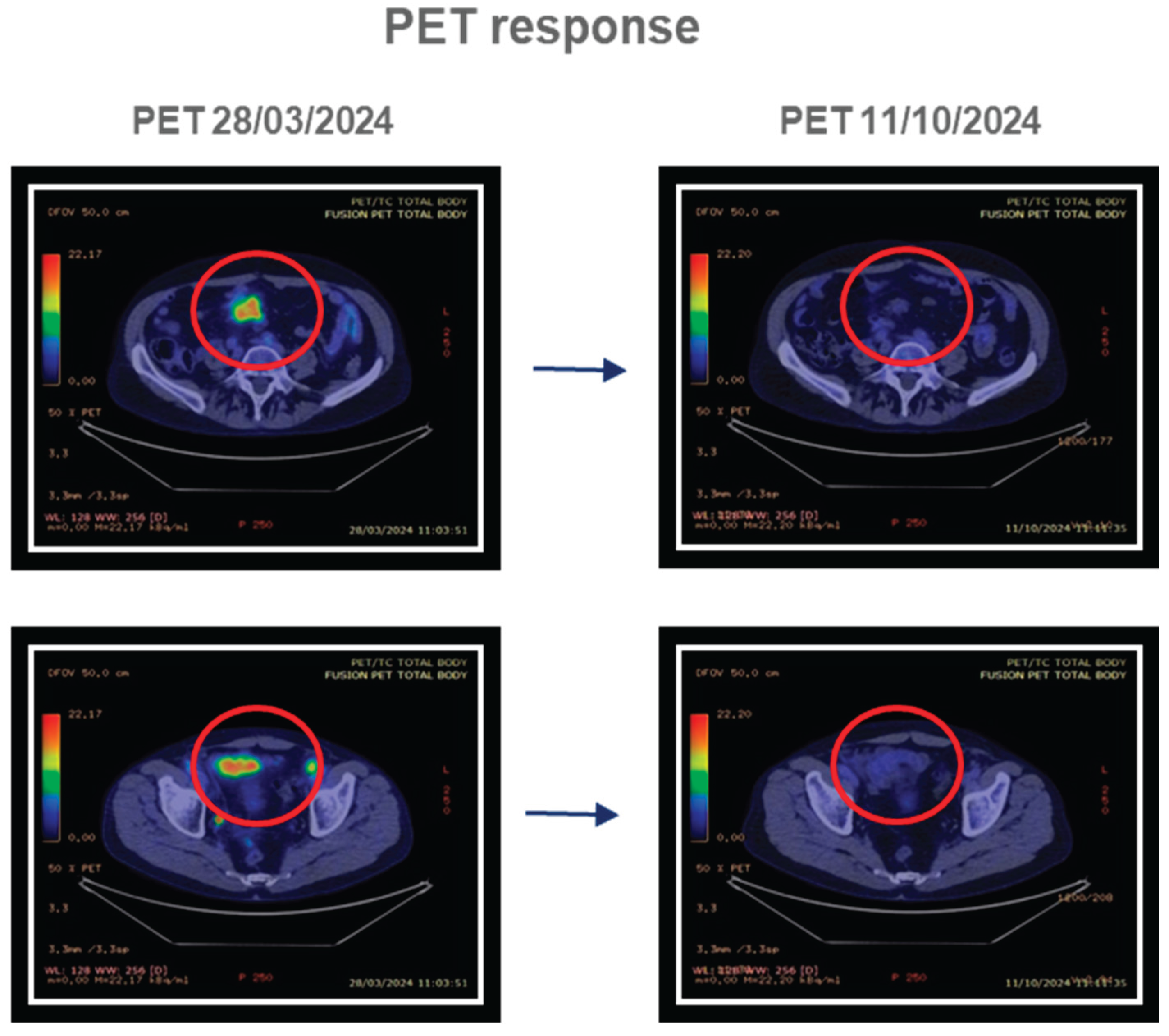

4.1.2. Patient 2

4.1.3. Patient 3

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pier Luigi Zinzani, Javier Muñoz and Judith Trotman, et.al. Current and future therapies for follicular lymphoma. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Casulo C, Friedberg JW, Ahn KW, Flowers C, DiGilio A, Smith SM, et al. Autologous transplantation in follicular lymphoma with early therapy failure: a National LymphoCare Study and Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research Analysis. Biol Blood Marrow Transpl. 2018;24(6):1163–71. [CrossRef]

- World health organization classification of tumours of haematopoietic and lymphoid tissues, revised 4th edition, Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Harris NL, et al. (Eds), IARC, Lyon 2017.

- Ottensmeier CH, Thompsett AR, Zhu D, et al. Analysis of VH genes in follicular and diffuse lymphoma shows ongoing somatic mutation and multiple isotype transcripts in early disease with changes during disease progression. Blood 1998; 91:4292.

- Jennifer R Brown, MD, PhDArnold S Freedman, MDJon C Aster, MD, PhD Andrew Lister, Rebecca F Connor, et al. Pathobiology of follicular lymphoma 2025.

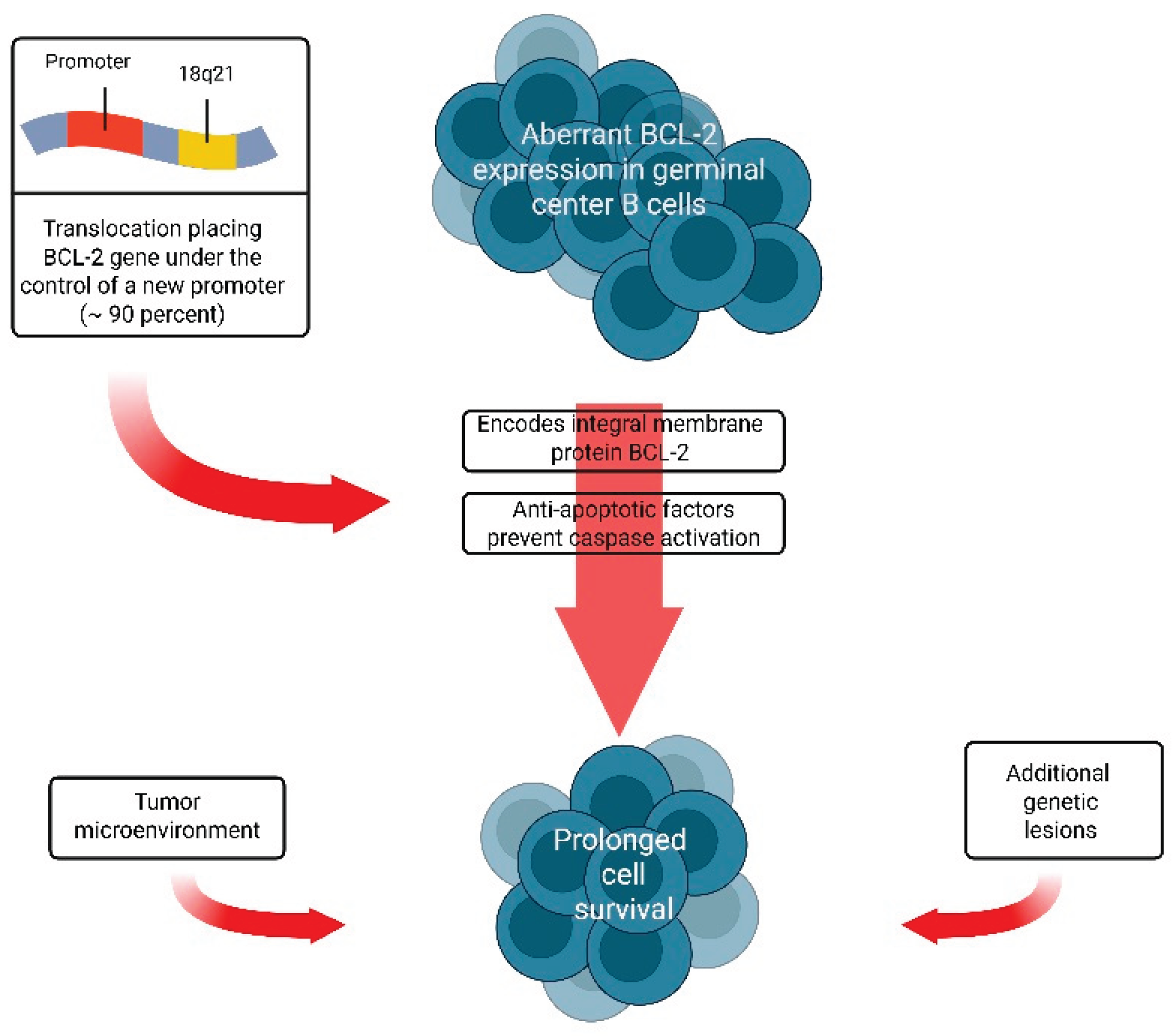

- Nuñez G, Hockenbery D, McDonnell TJ, et al. Bcl-2 maintains B cell memory. Nature 1991; 353:71. [CrossRef]

- McDonnell TJ, Deane N, Platt FM, et al. bcl-2-immunoglobulin transgenic mice demonstrate extended B cell survival and follicular lymphoproliferation. Cell 1989; 57:79. [CrossRef]

- Bende RJ, Smit LA, van Noesel CJ. Molecular pathways in follicular lymphoma. Leukemia 2007; 21:18. [CrossRef]

- Lindhout E, Mevissen ML, Kwekkeboom J, et al. Direct evidence that human follicular dendritic cells (FDC) rescue germinal centre B cells from death by apoptosis. Clin Exp Immunol 1993; 91:330. [CrossRef]

- Dave SS, Wright G, Tan B, et al. Prediction of survival in follicular lymphoma based on molecular features of tumor-infiltrating immune cells. N Engl J Med 2004; 351:2159. [CrossRef]

- Glas AM, Knoops L, Delahaye L, et al. Gene-expression and immunohistochemical study of specific T-cell subsets and accessory cell types in the transformation and prognosis of follicular lymphoma. J Clin Oncol 2007; 25:390. [CrossRef]

- Coupland SE. The challenge of the microenvironment in B-cell lymphomas. Histopathology 2011; 58:69. [CrossRef]

- Laurent C, Müller S, Do C, et al. Distribution, function, and prognostic value of cytotoxic T lymphocytes in follicular lymphoma: a 3-D tissue-imaging study. Blood 2011; 118:5371. [CrossRef]

- Jennifer R Brown, MD, PhDArnold S Freedman, MDJon C Aster, MD, PhD Andrew Lister, Rebecca F Connor, et al. Clinical manifestations, pathological features, diagnosis, and prognosis of follicular lymphoma 2025.

- World Health Organization Classification of Tumours of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues, Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Harris NL, et al. (Eds), IARC Press, Lyon 2008.

- Solal-Céligny P, Roy P, Colombat P, et al. Follicular lymphoma international prognostic index. Blood 2004; 104:1258.

- Martin AR, Weisenburger DD, Chan WC, et al. Prognostic value of cellular proliferation and histologic grade in follicular lymphoma. Blood 1995; 85:3671. [CrossRef]

- Anderson T, Chabner BA, Young RC, et al. Malignant lymphoma. 1. The histology and staging of 473 patients at the National Cancer Institute. Cancer 1982; 50:2699. [CrossRef]

- Fernández de Larrea C, Martínez-Pozo A, Mercadal S, et al. Initial features and outcome of cutaneous and non-cutaneous primary extranodal follicular lymphoma. Br J Haematol 2011; 153:334. [CrossRef]

- Rasmussen PK, Coupland SE, Finger PT, et al. Ocular adnexal follicular lymphoma: a multicenter international study. JAMA Ophthalmol 2014; 132:851.

- Weindorf SC, Smith LB, Owens SR. Update on Gastrointestinal Lymphomas. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2018; 142:1347.

- Louissaint A Jr, Ackerman AM, Dias-Santagata D, et al. Pediatric-type nodal follicular lymphoma: an indolent clonal proliferation in children and adults with high proliferation index and no BCL2 rearrangement. Blood 2012; 120:2395. [CrossRef]

- Canioni D, Brice P, Lepage E, et al. Bone marrow histological patterns can predict survival of patients with grade 1 or 2 follicular lymphoma: a study from the Groupe d’Etude des Lymphomes Folliculaires. Br J Haematol 2004; 126:364. [CrossRef]

- Sarkozy C, Baseggio L, Feugier P, et al. Peripheral blood involvement in patients with follicular lymphoma: a rare disease manifestation associated with poor prognosis. Br J Haematol 2014; 164:659. [CrossRef]

- Flenghi L, Bigerna B, Fizzotti M, et al. Monoclonal antibodies PG-B6a and PG-B6p recognize, respectively, a highly conserved and a formol-resistant epitope on the human BCL-6 protein amino-terminal region. Am J Pathol 1996; 148:1543.

- Pittaluga S, Ayoubi TA, Wlodarska I, et al. BCL-6 expression in reactive lymphoid tissue and in B-cell non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas. J Pathol 1996; 179:145. [CrossRef]

- Campo E, Jaffe ES, Cook JR, et al. The International Consensus Classification of Mature Lymphoid Neoplasms: a report from the Clinical Advisory Committee. Blood 2022; 140:1229. [CrossRef]

- Jegalian AG, Eberle FC, Pack SD, et al. Follicular lymphoma in situ: clinical implications and comparisons with partial involvement by follicular lymphoma. Blood 2011; 118:2976. [CrossRef]

- Tellier J, Menard C, Roulland S, et al. Human t (14;18) positive germinal center B cells: a new step in follicular lymphoma pathogenesis? Blood 2014; 123:3462. [CrossRef]

- Yoshino T, Chott A. Duodenal-type follicular lymphoma. In: WHO Classification of Tumours: Digestive System Tumours, 5th, International Agency for Research on Cancer, Lyon 2019. p.383.

- Schmatz AI, Streubel B, Kretschmer-Chott E, et al. Primary follicular lymphoma of the duodenum is a distinct mucosal/submucosal variant of follicular lymphoma: a retrospective study of 63 cases. J Clin Oncol 2011; 29:1445. [CrossRef]

- Mori M, Kobayashi Y, Maeshima AM, et al. The indolent course and high incidence of t (14;18) in primary duodenal follicular lymphoma. Ann Oncol 2010; 21:1500. [CrossRef]

- Horning SJ, Rosenberg SA. The natural history of initially untreated low-grade non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas. N Engl J Med 1984; 311:1471. [CrossRef]

- Casulo C, Byrtek M, Dawson KL, et al. Early Relapse of Follicular Lymphoma After Rituximab Plus Cyclophosphamide, Doxorubicin, Vincristine, and Prednisone Defines Patients at High Risk for Death: An Analysis From the National LymphoCare Study. J Clin Oncol 2015; 33:2516. [CrossRef]

- Hans CP, Weisenburger DD, Vose JM, et al. A significant diffuse component predicts for inferior survival in grade 3 follicular lymphoma, but cytologic subtypes do not predict survival. Blood 2003; 101:2363. [CrossRef]

- Horn H, Schmelter C, Leich E, et al. Follicular lymphoma grade 3B is a distinct neoplasm according to cytogenetic and immunohistochemical profiles. Haematologica 2011; 96:1327. [CrossRef]

- Jennifer R Brown, MD, PhDArnold S Freedman, MDJon C Aster, MD, PhD Andrew Lister, Rebecca F Connor, et al. Initial treatment of stage I follicular lymphoma 2025.

- Jennifer R Brown, MD, PhDArnold S Freedman, MDJon C Aster, MD, PhD Andrew Lister, Rebecca F Connor, et al. Initial treatment of stage II to IV follicular lymphoma 2025.

- Cheson BD, Fisher RI, Barrington SF, et al. Recommendations for initial evaluation, staging, and response assessment of Hodgkin and non-Hodgkin lymphoma: the Lugano classification. J Clin Oncol 2014; 32:3059. [CrossRef]

- Luminari S, Biasoli I, Arcaini L, et al. The use of FDG-PET in the initial staging of 142 patients with follicular lymphoma: a retrospective study from the FOLL05 randomized trial of the Fondazione Italiana Linfomi. Ann Oncol 2013; 24:2108. [CrossRef]

- Friedberg JW, Taylor MD, Cerhan JR, et al. Follicular lymphoma in the United States: first report of the national LymphoCare study. J Clin Oncol 2009; 27:1202. [CrossRef]

- Dinnessen MAW, van der Poel MWM, Tonino SH, et al. Stage-specific trends in primary therapy and survival in follicular lymphoma: a nationwide population-based analysis in the Netherlands, 1989-2016. Leukemia 2021; 35:1683. [CrossRef]

- Nooka AK, Nabhan C, Zhou X, et al. Examination of the follicular lymphoma international prognostic index (FLIPI) in the National LymphoCare study (NLCS): a prospective US patient cohort treated predominantly in community practices. Ann Oncol 2013; 24:441. [CrossRef]

- Friedberg JW, Taylor MD, Cerhan JR, et al. Follicular lymphoma in the United States: first report of the national LymphoCare study. J Clin Oncol 2009; 27:1202. [CrossRef]

- Ardeshna KM, Qian W, Smith P, et al. Rituximab versus a watch-and-wait approach in patients with advanced-stage, asymptomatic, non-bulky follicular lymphoma: an open-label randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 2014; 15:424. [CrossRef]

- Cartron G, Bachy E, Tilly H, et al. Randomized Phase III Trial Evaluating Subcutaneous Rituximab for the First-Line Treatment of Low-Tumor Burden Follicular Lymphoma: Results of a LYSA Study. J Clin Oncol 2023; 41:3523. [CrossRef]

- Marcus R, Imrie K, Belch A, et al. CVP chemotherapy plus rituximab compared with CVP as first-line treatment for advanced follicular lymphoma. Blood 2005; 105:1417. [CrossRef]

- Schulz H, Bohlius J, Skoetz N, et al. Chemotherapy plus Rituximab versus chemotherapy alone for B-cell non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2007:CD003805. [CrossRef]

- Marcus R, Davies A, Ando K, et al. Obinutuzumab for the First-Line Treatment of Follicular Lymphoma. N Engl J Med 2017; 377:1331. [CrossRef]

- Czuczman MS, Koryzna A, Mohr A, et al. Rituximab in combination with fludarabine chemotherapy in low-grade or follicular lymphoma. J Clin Oncol 2005; 23:694. [CrossRef]

- Federico M, Luminari S, Dondi A, et al. R-CVP versus R-CHOP versus R-FM for the initial treatment of patients with advanced-stage follicular lymphoma: results of the FOLL05 trial conducted by the Fondazione Italiana Linfomi. J Clin Oncol 2013; 31:1506. [CrossRef]

- Jennifer R Brown, MD, PhDArnold S Freedman, MDJon C Aster, MD, PhD Andrew Lister, Rebecca F Connor, et al. Treatment of relapsed or refractory follicular lymphoma 2025.

- Casulo C, Byrtek M, Dawson KL, et al. Early Relapse of Follicular Lymphoma After Rituximab Plus Cyclophosphamide, Doxorubicin, Vincristine, and Prednisone Defines Patients at High Risk for Death: An Analysis From the National LymphoCare Study. J Clin Oncol 2015; 33:2516. [CrossRef]

- Maurer MJ, Bachy E, Ghesquières H, et al. Early event status informs subsequent outcome in newly diagnosed follicular lymphoma. Am J Hematol 2016; 91:1096. [CrossRef]

- Yamshon S, Christos PJ, Demetres M, et al. Venous thromboembolism in patients with B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma treated with lenalidomide: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Blood Adv 2018; 2:1429. [CrossRef]

- Marcus R, Davies A, Ando K, et al. Obinutuzumab for the First-Line Treatment of Follicular Lymphoma. N Engl J Med 2017; 377:1331. [CrossRef]

- Cheson BD, Chua N, Mayer J, et al. Overall Survival Benefit in Patients With Rituximab-Refractory Indolent Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma Who Received Obinutuzumab Plus Bendamustine Induction and Obinutuzumab Maintenance in the GADOLIN Study. J Clin Oncol 2018; 36:2259. [CrossRef]

- Hiddemann W, Barbui AM, Canales MA, et al. Immunochemotherapy With Obinutuzumab or Rituximab for Previously Untreated Follicular Lymphoma in the GALLIUM Study: Influence of Chemotherapy on Efficacy and Safety. J Clin Oncol 2018; 36:2395. [CrossRef]

- Van Oers MH, Klasa R, Marcus RE, et al. Rituximab maintenance improves clinical outcome of relapsed/resistant follicular non-Hodgkin lymphoma in patients both with and without rituximab during induction: results of a prospective randomized phase 3 intergroup trial. Blood 2006; 108:3295. [CrossRef]

- Van Oers MH, Van Glabbeke M, Giurgea L, et al. Rituximab maintenance treatment of relapsed/resistant follicular non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma: long-term outcome of the EORTC 20981 phase III randomized intergroup study. J Clin Oncol 2010; 28:2853. [CrossRef]

- Mosunetuzumab product information. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/lunsumio-epar-product-information_en.pdf.

- Mosunetuzumab-axgb injection, for intravenous use. United States prescribing information. US Food and Drug Administration. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2022/761263s000lbl.pdf.

- Epcoritamab-bysp injection. US Food & Drug Administration (FDA) approved product information. US National Library of Medicine. (Available online at www.dailymed.nlm.nih.gov/dailymed/index.cfm).

- Oliansky DM, Gordon LI, King J, et al. The role of cytotoxic therapy with hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in the treatment of follicular lymphoma: an evidence-based review. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2010; 16:443. [CrossRef]

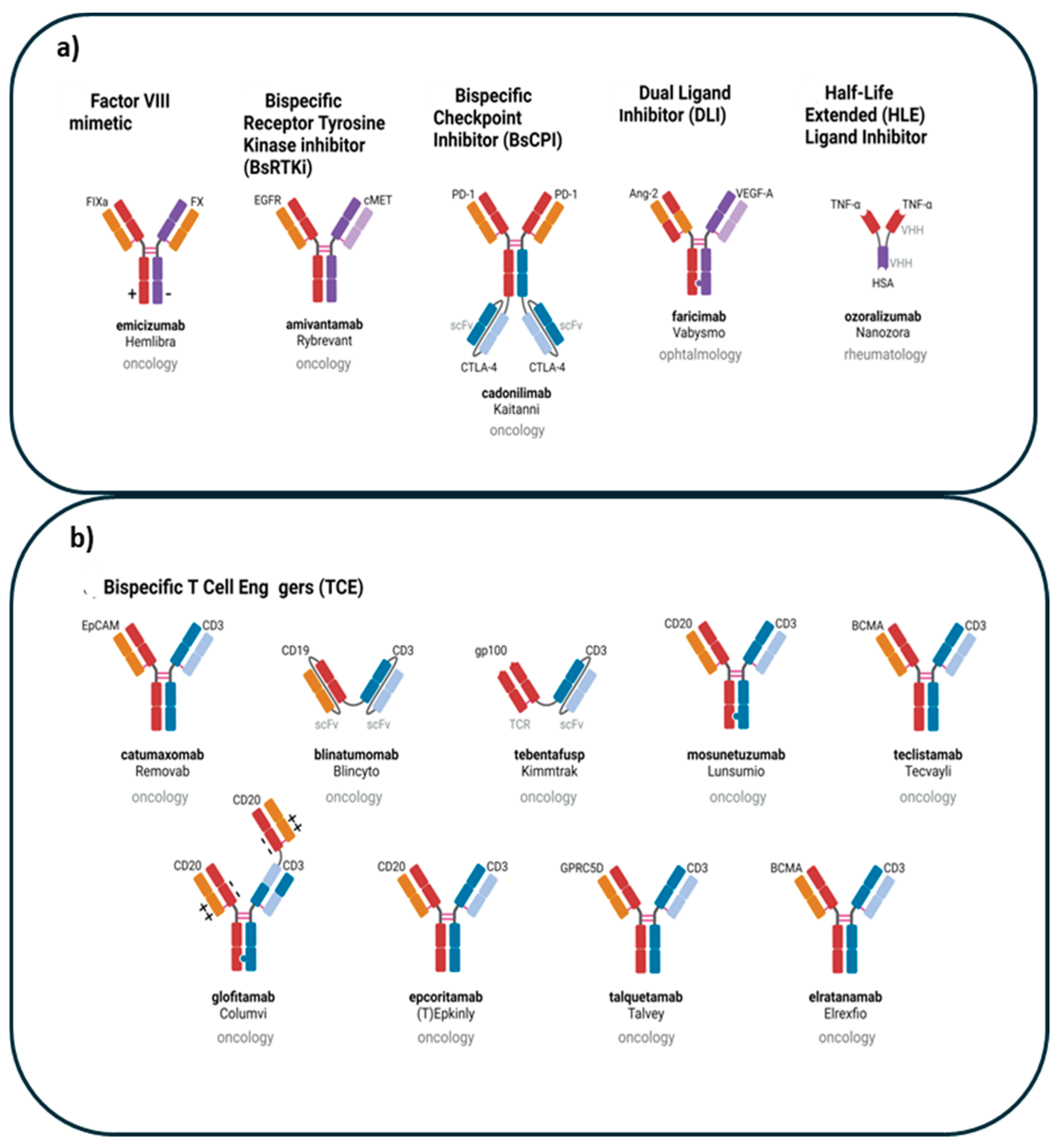

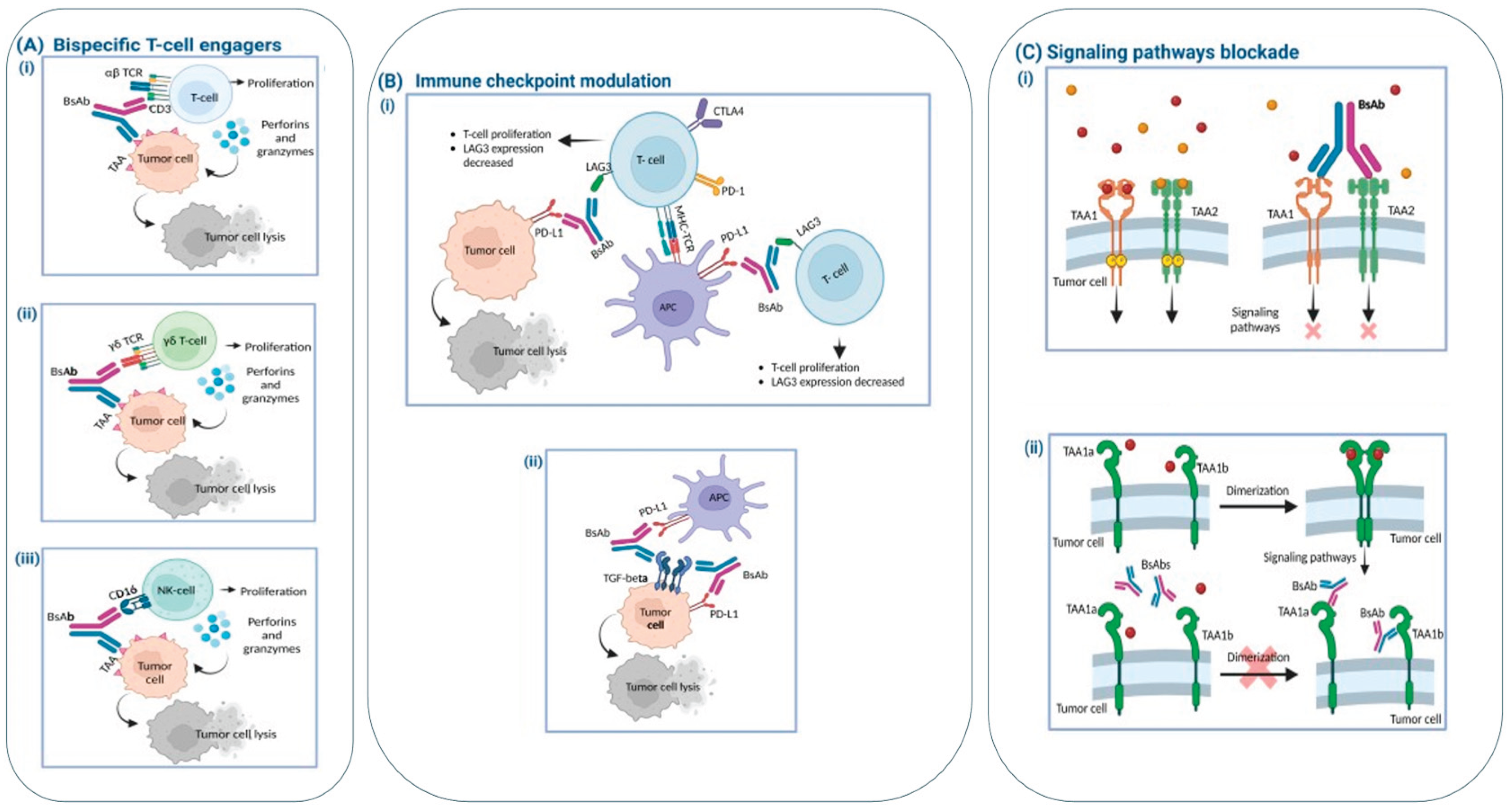

- Mercedes Herrera, Giulia Pretelli, Jayesh Desai, Elena Garralda, Lillian L. Siu, Thiago M. Steiner, and Lewis Au, et al. Bispecific antibodies: advancing precision oncology 2024. [CrossRef]

- Longhitano, A.P. et al. (2021) Bispecific antibody therapy, its use and risks for infection: bridging the knowledge gap. Blood Rev. 49, 100810. [CrossRef]

- Park, K. et al. (2023) Management of infusion-related reactions (IRRs) in patients receiving amivantamab in the CHRYSALIS study. Lung Cancer 178, 166–171. [CrossRef]

- Labrijn, A. et al. (2019) Bispecific antibodies: a mechanistic review of the pipeline. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 18, 585–608. [CrossRef]

- Chiu, M.L. et al. (2019) Antibody structure and function: the basis for engineering therapeutics. Antibodies (Basel) 8, 55. [CrossRef]

- Brinkmann, U. and Kontermann, R.E. (2017) The making of bispecific antibodies. MAbs 9, 182–212.

- Ko, S. et al. (2022) An Fc variant with two mutations confers prolonged serum half-life and enhanced effector functions on IgG antibodies. Exp. Mol. Med. 54, 1850–1861. [CrossRef]

- Yu, J. et al. (2020) How to select IgG subclasses in developing anti-tumor therapeutic antibodies. J. Hematol. Oncol. 13, 45. [CrossRef]

- Dreier, T. et al. (2003) T cell costimulus-independent and very efficacious inhibition of tumor growth in mice bearing subcutaneous r leukemic human B cell lymphoma xenografts by a CD19-/CD3- bispecific single-chain antibody construct. J. Immunol. 170, 4397–4402. [CrossRef]

- van der Merwe, P.A. and Dushek, O. (2011) Mechanisms for T cell receptor triggering. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 11, 47–55. [CrossRef]

- Van de Donk, N.W.C.J. and Zweegman, S. (2023) T-cell engaging bispecific antibodies in cancer. Lancet 402, 142–158.

- Mollavelioglu, B. et al. (2022) High co-expression of immune checkpoint receptors PD-1, CTLA-4, LAG-3, TIM-3, and TIGIT on tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in early-stage breast cancer. World J. Surg. Oncol. 20, 349. [CrossRef]

- Huang, S. et al. (2020) Bispecific antibodies targeting dual tumor-associated antigens in cancer therapy. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 146, 3111–3122. [CrossRef]

- Ma, J. et al. (2021) Bispecific antibodies: from research to clinical application. Front. Immunol. 12, 626616. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y. et al. (2015) Multifunctional receptor-targeting antibodies for cancer therapy. Lancet Oncol. 16, e543–e554. [CrossRef]

- Gogesch, P. et al. (2021) The role of Fc receptors on the effectiveness of therapeutic monoclonal antibodies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22, 8947. [CrossRef]

- Westover, D. et al. (2018) Mechanisms of acquired resistance to first- and second-generation EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors. Ann. Oncol. 29, i10–i19. [CrossRef]

- Shimabukuro-Vornhagen, A. et al. (2018) Cytokine release syndrome. J. Immunother. Cancer 6, 56.

- Leclercq-Cohen, G. et al. (2023) Dissecting the mechanisms underlying the cytokine release syndrome (CRS) mediated by T-cell bispecific antibodies. Clin. Cancer Res. 29, 4449–4463. [CrossRef]

- Markouli, M. et al. (2023) Toxicity profile of chimeric antigen receptor T-cell and bispecific antibody therapies in multiple myeloma: pathogenesis, prevention and management. Curr. Oncol. 30, 6330–6352. [CrossRef]

- Ball, K. et al. (2023) Strategies for clinical dose optimization of T cell-engaging therapies in oncology. MAbs 15, 2181016. [CrossRef]

- Morris, E.C. et al. (2022) Cytokine release syndrome and associated neurotoxicity in cancer immunotherapy. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 22, 85–96. [CrossRef]

- Gu, T. et al. (2022) Mechanisms of immune effector cell associated neurotoxicity syndrome after CAR-T treatment. WIREs Mech. Dis. 14, e1576. [CrossRef]

- Calogiuri, G. et al. (2008) Hypersensitivity reactions to last generation chimeric, humanized [correction of umanized] and human recombinant monoclonal antibodies for therapeutic use. Curr. Pharm. Des. 14, 2883–2891. [CrossRef]

- Rombouts, M.D. et al. (2020) Systematic review on infusion reactions to and infusion rate of monoclonal antibodies used in cancer treatment. Anticancer Res. 40, 1201–1218. [CrossRef]

- Doessegger, L. and Banholzer, M.L. (2015) Clinical development methodology for infusion-related reactions with monoclonal antibodies. Clin. Transl. Immunol. 4, e39. [CrossRef]

- Cáceres, M.C. et al. (2019) The importance of early identification of infusion-related reactions to monoclonal antibodies. Ther. Clin. Risk Manag. 15, 965–977. [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, G. et al. (2023) Infections following bispecific antibodies in myeloma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Blood Adv. 7, 5898–5903. [CrossRef]

- Ferl GZ, et al. 2018 A Preclinical Population Pharmacokinetic Model for Anti-CD20/CD3 T-Cell-Dependent Bispecific Antibodies;11:296–304;

- Cancemi, G.; Campo, C.; Caserta, S.; Rizzotti, I.; Mannina, D. Single-Agent and Associated Therapies with Monoclonal Antibodies: What About Follicular Lymphoma? Cancers 2025, 17, 1602. [CrossRef]

- Vital EM, et al. B-cell depletion. In: Rheumatology 2015:472–78.

- Budde LE, Sehn LH, Matasar M, Schuster SJ, Assouline S, Giri P, Kuruvilla J, Canales M, Dietrich S, Fay K. et al. Safety and efficacy of Mosunetuzumab, a bispecific antibody, in patients with relapsed or refractory follicular lymphoma: a single-arm, multicentre, phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol. 2022;23(8):1055–1065. [CrossRef]

- Alfredo Rivas-Delgado, Ivan Landego & Lorenzo Falchi (2024) The landscape of T-cell engagers for the treatment of follicular lymphoma, OncoImmunology, 13:1, 2412869. [CrossRef]

- Carbone A, Roulland S, Gloghini A, Younes A, von Keudell G, López Guillermo A, Fitzgibbon J. Follicular lymphoma. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2019;5(1):83.

- Salles G, Ghesquières H. Current and future management of follicular lymphoma. Int J Hematol. 2012; 96:544–51. [CrossRef]

- Sarkozy C, Maurer MJ, Link BK, Ghesquieres H, Nicolas E, Thompson CA, et al. Cause of death in follicular lymphoma in the first decade of the rituximab era: a pooled analysis of French and US cohorts. J Clin Oncol. 2019;37(2):144. [CrossRef]

- Marcus R, Davies A, Ando K, Klapper W, Opat S, Owen C, et al. Obinutuzumab for the first-line treatment of follicular lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(14):1331–44. [CrossRef]

- Morschhauser F, Nastoupil L, Feugier P, De Colella J-MS, Tilly H, Palomba ML, et al. Six-year results from RELEVANCE: lenalidomide plus rituximab (R2) versus rituximab-chemotherapy followed by rituximab maintenance in untreated advanced follicular lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2022;40(28):3239. [CrossRef]

- Mauro GP, Medici CTM, Casimiro LC, Weltman E. Radiotherapy for early and advanced stages follicular lymphoma. Clinics. 2021;76: e2059. [CrossRef]

- MacManus M, Fisher R, Roos D, O’Brien P, Macann A, Davis S, et al. Randomized trial of systemic therapy after involved-field radiotherapy in patients with early-stage follicular lymphoma: TROG 99.03. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(29):2918–25. [CrossRef]

- Casulo C, Larson MC, Lunde JJ, Habermann TM, Lossos IS, Wang Y, et al. Treatment patterns and outcomes of patients with relapsed or refractory follicular lymphoma receiving three or more lines of systemic therapy (LEO CReWE): a multicentre cohort study. Lancet Haematol. 2022;9(4): e289–300. [CrossRef]

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. B-Cell Lymphomas. (Version 5.2022). 2022. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/b-cell. pdf. Accessed 20 Aug 2023.

- Hill BT, Nastoupil L, Winter AM, Becnel MR, Cerhan JR, Habermann TM, et al. Maintenance rituximab or observation after frontline treatment with bendamustine- rituximab for follicular lymphoma. Br J Haematol. 2019;184(4):524–35. [CrossRef]

- Casulo C, Friedberg JW, Ahn KW, Flowers C, DiGilio A, Smith SM, et al. Autologous transplantation in follicular lymphoma with early therapy failure: a National LymphoCare Study and Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research Analysis. Biol Blood Marrow Transpl. 2018;24(6):1163–71. [CrossRef]

- Wu Y, Yi M, Zhu S, Wang H, Wu K. Recent advances and challenges of bispecific antibodies in solid tumors. Exp Hematol Oncol. 2021;10(1):1–14. [CrossRef]

- Budde LE, Sehn LH, Matasar M, Schuster SJ, Assouline S, Giri P, et al. Safety and efficacy of Mosunetuzumab, a bispecific antibody, in patients with relapsed or refractory follicular lymphoma: a single-arm, multicentre, phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol. 2022;23(8):1055–65. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).