Submitted:

02 January 2026

Posted:

04 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

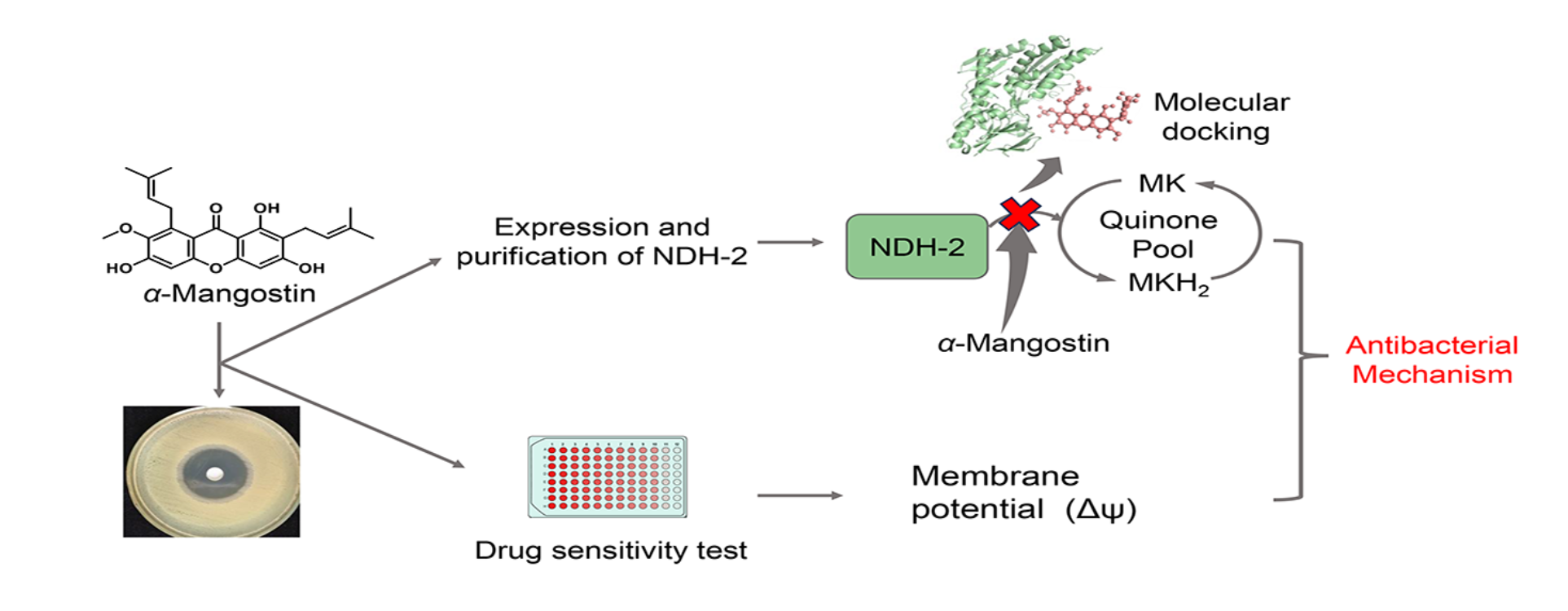

Abstract

Keywords:

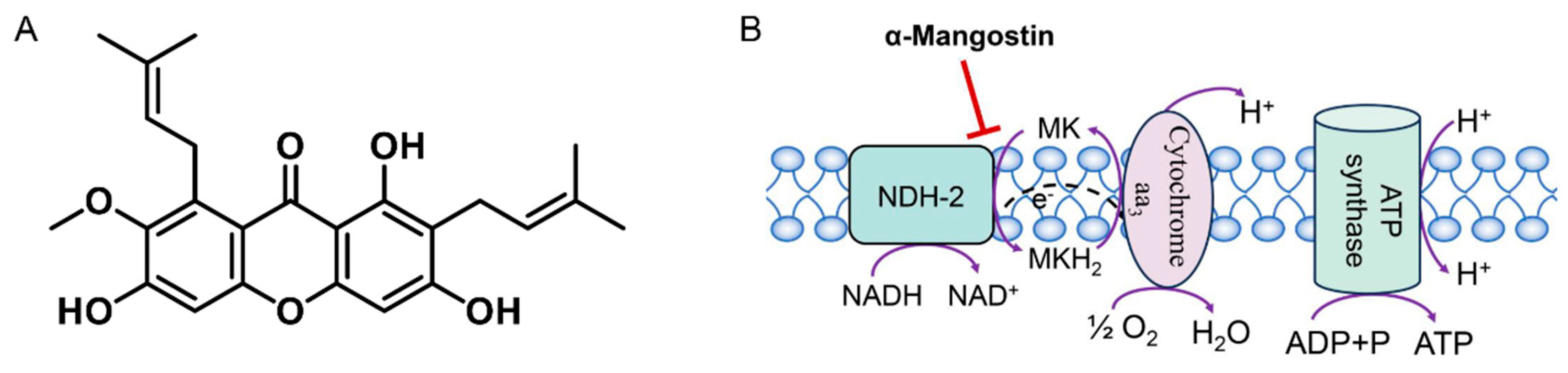

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials, Chemicals, and Reagents

2.2. Antimicrobial Susceptibility Assay

2.3. Expression and Purification of the Enzyme

2.4. Determination of NDH-2 Activity

2.5. Inhibition of NDH-2 by α-Mangostin

2.6. Fluorescence Spectroscopy Analysis of the Interaction between α-Mangostin and NDH-2

2.7. Molecular Docking

2.8. Measurement of Membrane Potential

3. Results

3.1. Minimum Inhibitory Concentrations (MICs) and Minimum Bactericidal Concentrations (MBCs)

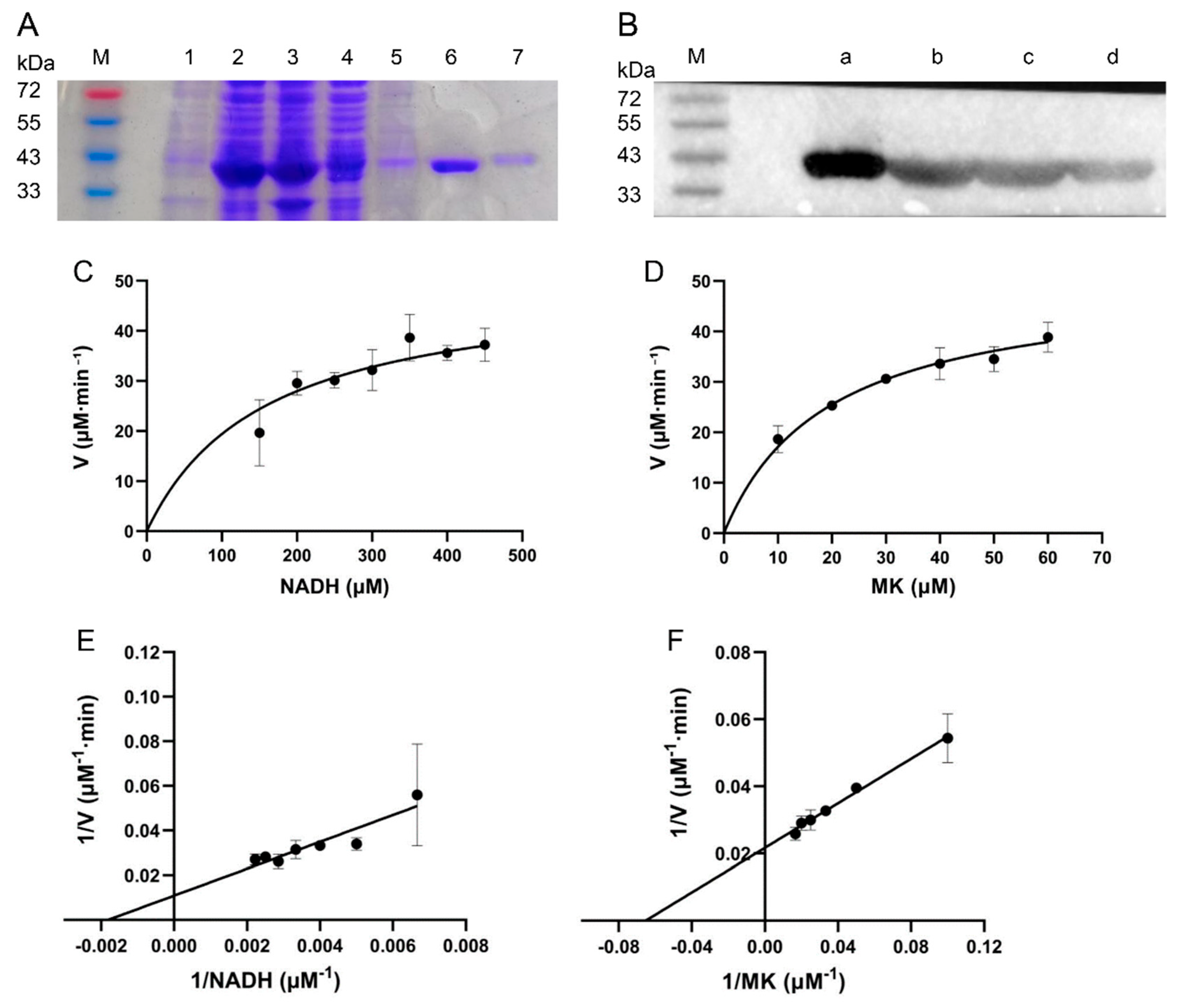

3.2. Protein Purification and Enzymatic Characterization

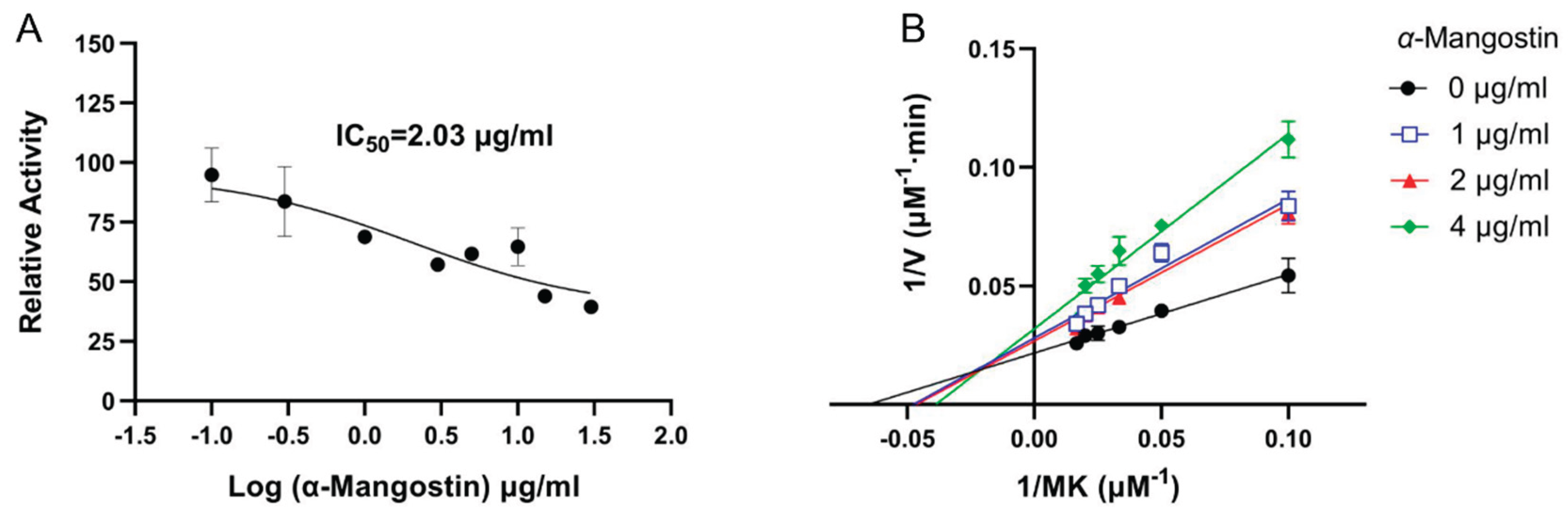

3.3. Inhibitory Effect of α-Mangostin on NDH-2 Activity

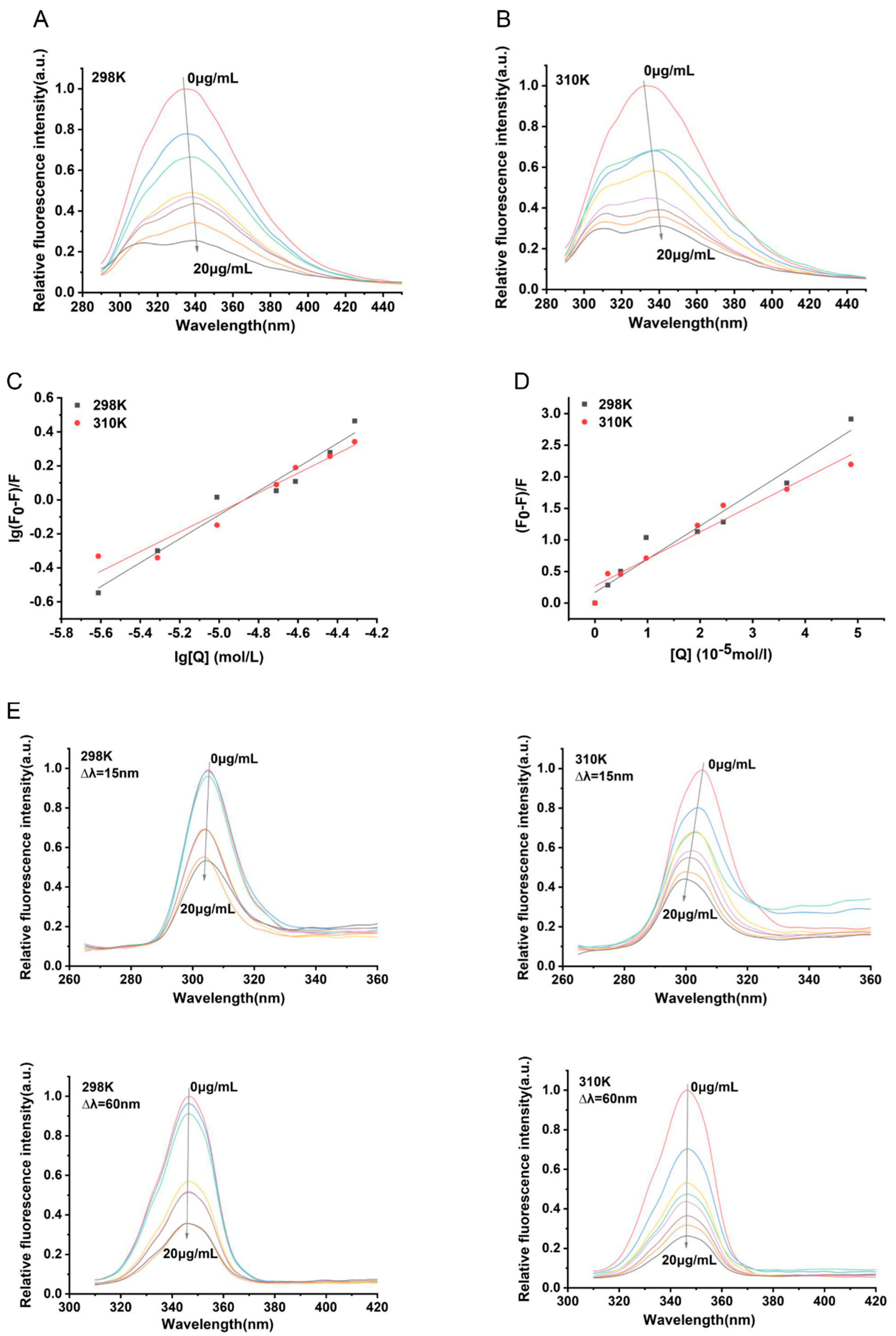

3.4. Analysis of the Binding Properties Between α-Mangostin and NDH-2

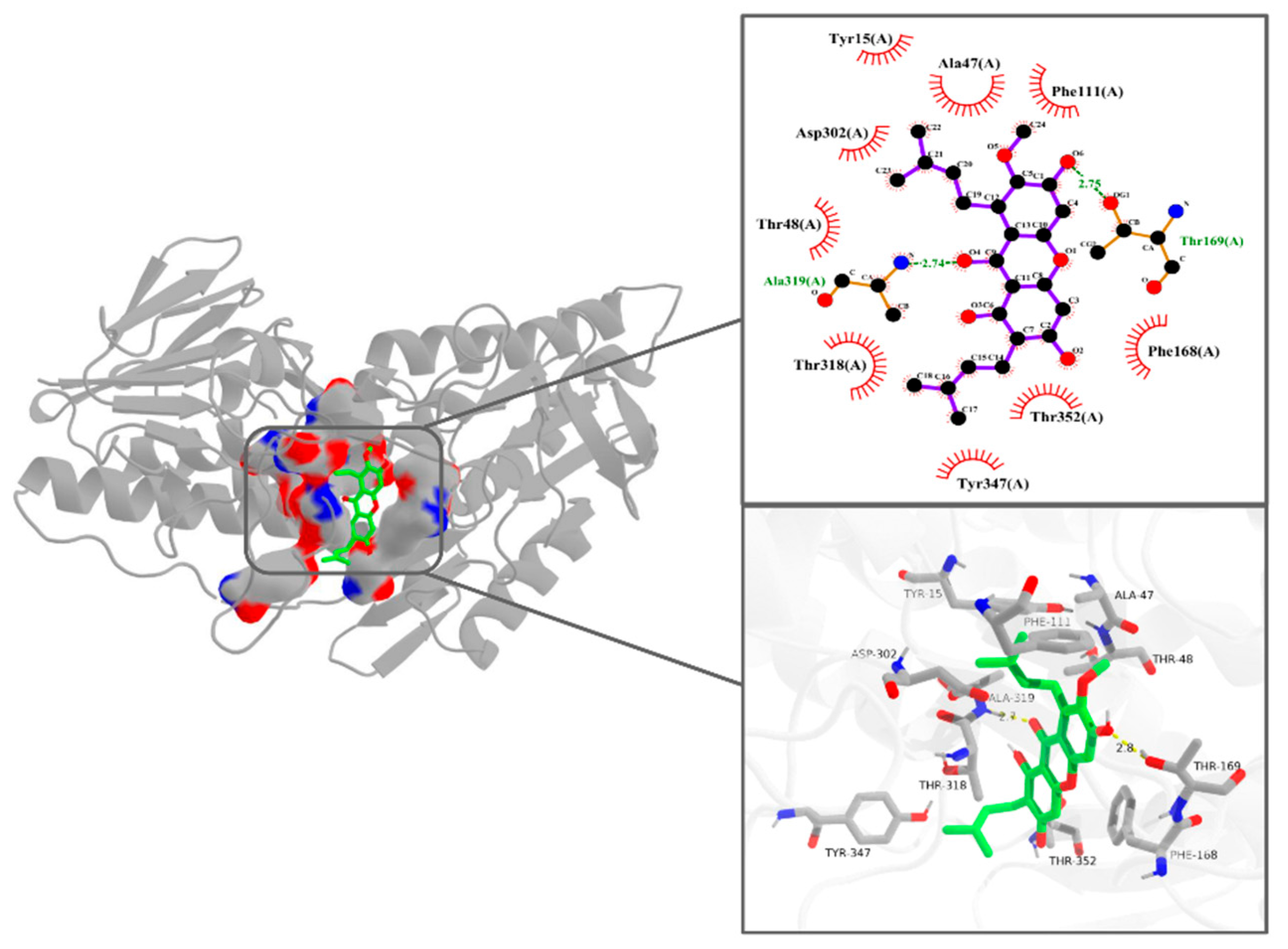

3.5. Interaction Pattern Between α-Mangostin and NDH-2

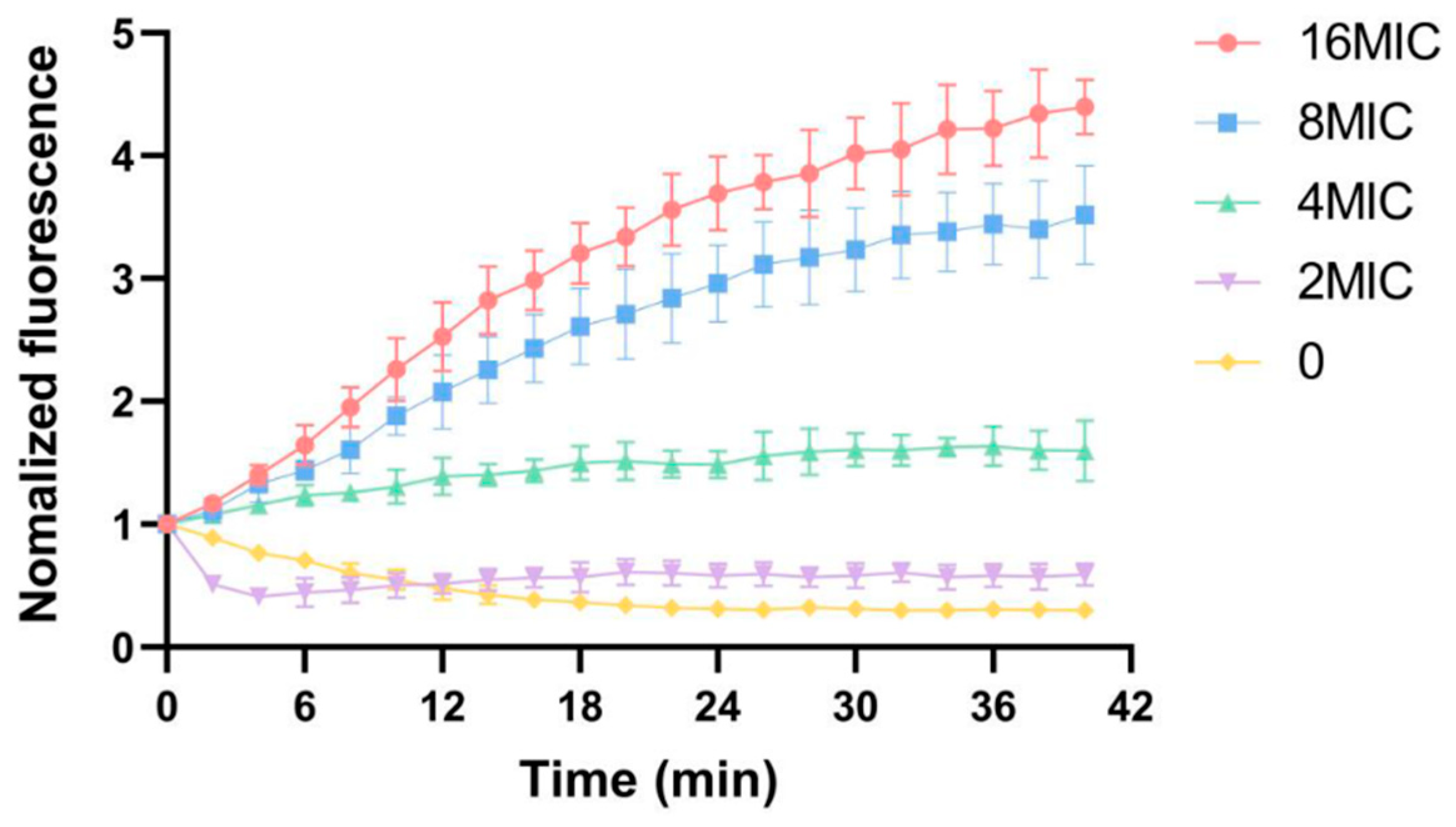

3.6. Influence of Membrane Potential

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- GBD 2021 Antimicrobial Resistance Collaborators. Global burden of bacte-rial antimicrobial resistance 1990-2021: a systematic analysis with forecaststo 2050. Lancet 2024, 404(10459), 1199–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talan, DA; Krishnadasan, A; Gorwitz, RJ; Fosheim, GE; Limbago, B; Albrecht, V; et al. Comparison of Staphylococcus aureus from skin and soft-tissue infections in US emergency department patients, 2004 and 2008. Clin Infect Dis. 2011, 53, 144–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurosu, M; Siricilla, S; Mitachi, K. Advances in MRSA drug discovery: where are we and where do we need to be? Expert Opin Drug Discov 2013, 8, 1095–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cushnie, TPT; Lamb, AJ. Antimicrobial activity of flavonoids. Int J Antimicrob Agents 2005, 26, 343–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, TLA; Bhattacharya, D. Antimicrobial activity of quercetin: An ap-proach to its mechanistic principle. Molecules 2022, 27, 2494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, Y; Guan, T; Wang, S; Zhou, C; Wang, M; Wang, X; et al. Novel xanth-one antibacterials: Semi-synthesis, biological evaluation, and the action me-chanisms. Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry 2023, 83, 117232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iinuma, M; Tosa, H; Tanaka, T; Asai, F; Kobayashi, Y; Shimano, R; et al. Antibacterial activity of xanthones from guttiferaeous plants against methicil-lin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. J Pharm Pharmacol. 1996, 48, 861–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakagami, Y; Iinuma, M; Piyasena, KGNP; Dharmaratne, HRW. Antibacterial activity of alpha-mangostin against vancomycin resistant Enterococci (VRE) and synergism with antibiotics. Phytomedicine 2005, 12, 203–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koh, JJ; Qiu, S; Zou, H; Lakshminarayanan, R; Li, J; Zhou, X; et al. Rapid bactericidal action of alpha-mangostin against MRSA as an outcome of membrane targeting. Biochim Biophys Acta 2013, 1828, 834–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L; Yan, Y; Zhu, J; Xia, X; Yuan, G; Li, S; et al. Quinone pool, a key target of plant flavonoids inhibiting Gram-Positive Bacteria. Molecules 2023, 28, 4972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaila, VRI; Wikström, M. Architecture of bacterial respiratory chains. Nat Rev Microbiol 2021, 19, 319–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurosu, M; Begari, E. Vitamin K2 in electron transport system: are enzymes involved in vitamin K2 biosynthesis promising drug targets? Molecules 2010, 15, 1531–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sena, FV; Sousa, FM; Pereira, AR; Catarino, T; Cabrita, EJ; Pinho, MG; et al. The two alternative NADH:quinone oxidoreductases from Staphylococcus aureus: Two players with different molecular and cellular roles. Microbiol Spectr. 2024, 12, e0415223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sena, FV; Batista, AP; Catarino, T; Brito, JA; Archer, M; Viertler, M; et al. Type-II NADH:quinone oxidoreductase from Staphylococcus aureus has two distinct binding sites and is rate limited by quinone reduction. Mol Microbiol. 2015, 98, 272–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schurig-Briccio, LA; Yano, T; Rubin, H; Gennis, RB. Characterization of the type 2 NADH:menaquinone oxidoreductases from Staphylococcus aureus and the bactericidal action of phenothiazines. Biochim Biophys Acta 2014, 1837, 954–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clinical and Laboratory and Standards Institute (CLSI). Methods for Dilution Antimicrobial Susceptibility Tests for Bacteria That Grow Aerobically, Approved Standards, CLSI Document M07-A10. Clinical and Laboratory and Standards Institute: Wayne, PA, USA, 2024.

- Xu, X; Xu, L; Yuan, G; Wang, Y; Qu, Y; Zhou, M. Synergistic combinationof two antimicrobial agents closing each other’s mutant selection windows to prevent antimicrobial resistance. Sci Rep. 2018, 8, 7237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Z; Li, P; Zhang, D; Zhu, J; Yuan, G; et al. A novel antimicrobial mechanism of Azalomycin F acting on lipoteichoic acid synthase and cell envelope. Molecules 2024, 29, 856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, GM; Huey, R; Lindstrom, W; Sanner, MF; Belew, RK; et al. AutoDock4 and AutoDockTools4: Automated docking with selective receptor flexibility. J Comput Chem. 2009, 30, 2785–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, JH; Liu, JX; Liu, Y; Chen, SW; Dai, WT; Xiao, ZX; et al. DrugRep: an automatic virtual screening server for drug repurposing. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2023, 44, 888–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schrödinger, LLC. The PyMOL molecular graphics system, Version 1.8 2015.

- Laskowski, RA; Swindells, MB. LigPlot+: multiple ligand-protein interaction diagrams for drug discovery. J Chem Inf Model. 2011, 51, 2778–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y; Jia, Y; Yang, K; Li, R; Xiao, X; Zhu, K; et al. Metformin restores tetracyclines susceptibility against multidrug resistant bacteria. Advanced Science 2020, 7, 1902227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mogi, T; Matsushita, K; Murase, Y; Kawahara, K; Miyoshi, H; Ui, H; et al. Identification of new inhibitors for alternative NADH dehydrogenase (NDH-II). FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2009, 291, 157–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petri, J; Shimaki, Y; Jiao, W; Bridges, HR; Russell, ER; Parker, EJ; et al. Structure of the NDH-2 - HQNO inhibited complex provides molecular insight into quinone-binding site inhibitors. Biochim Biophys Acta Bioenerg. 2018, 1859, 482–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, L; Wang, Y; He, Q; Zhang, Q; Du, L. Interaction between Pin1 and its natural product inhibitor epigallocatechin-3-gallate by spectroscopy and molecular dynamics simulations. Spectrochimica Acta Part A: Molecular and Biomolecular Spectroscopy 2016, 169, 134–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, M; Hancock, REW. Interaction of the cyclic antimicrobial cationic peptide bactenecin with the outer and cytoplasmic membrane. Journal of Biological Chemistry 1999, 274, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Górecka, H; Guźniczak, M; Buzalewicz, I; Ulatowska-Jarża, A; Korzekwa, K; Kaczorowska, A. Alpha-mangostin: A review of current research on its potential as a novel antimicrobial and anti-biofilm ggent. Int J Mol Sci. 2025, 26(11), 5281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paudel, A; Hamamoto, H; Panthee, S; Sekimizu, K. Menaquinone as a potential target of antibacterial agents. Drug Discov Ther. 2016, 10, 123–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boersch, M; Rudrawar, S; Grant, G; Zunk, M. Menaquinone biosynthesis inhibition: a review of advancements toward a new antibiotic mechanism. RSC Adv. 2018, 8, 5099–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yano, T; Rahimian, M; Aneja, KK; Schechter, NM; Rubin, H; Scott, CP. M-ycobacterium tuberculosis Type II NADH-menaquinone oxidoreductase cat-alyzes electron transfer through a two-site ping-pong mechanism and has two quinone-binding sites. Biochemistry 2014, 53, 1179–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, M; Liu, Y; Li, T; Liu, X; Hao, Z; Shen, J; et al. Plant natural flavonoids against multidrug resistant pathogens. Advanced Science 2021, 8, 2100749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geberetsadik, G; Inaizumi, A; Nishiyama, A; Yamaguchi, T; Hamamoto, H; Panthee, S; et al. Lysocin E targeting menaquinone in the membrane of my-cobacterium tuberculosis is a promising lead compound for antituberculosisdrugs. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2022, 66(9), e0017122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamamoto, H; Urai, M; Ishii, K; Yasukawa, J; Paudel, A; Murai, M; et al. Lysocin E is a new antibiotic that targets menaquinone in the bacterial membrane. Nat Chem Biol. 2015, 11, 127–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Parameters | 298 K | 310 K |

|---|---|---|

| Ksv (×104 L·mol-1) | 5.275 ± 0.045 | 4.273 ± 0.045 |

| Kq (×1012 L·mol-1) | 5.275 ± 0.045 | 4.273 ± 0.037 |

| Ra | 0.979 | 0.978 |

| Ka (L·mol-1) | 2.649×103 | 646.725 |

| N | 0.702 ± 0.065 | 0.577 ± 0.059 |

| Rb | 0.979 | 0.975 |

| ΔH (kJ·mol-1) | -90.239 | -90.239 |

| ΔG (kJ·mol-1) | -19.528 | -16.680 |

| ΔS (kJ·mol-1·K-1) | -0.237 | -0.237 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).