Submitted:

01 January 2026

Posted:

05 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Plain language summary

Main body

Introduction

Extracellular vesicles as sources of biomarkers

Box 1. Areas in which isolating EV-based biomarkers from inaccessible tissues in peripheral biofluids could lead to improved clinical outcomes for patients.

|

Extracellular vesicle-based biomarkers of neuropathological conditions

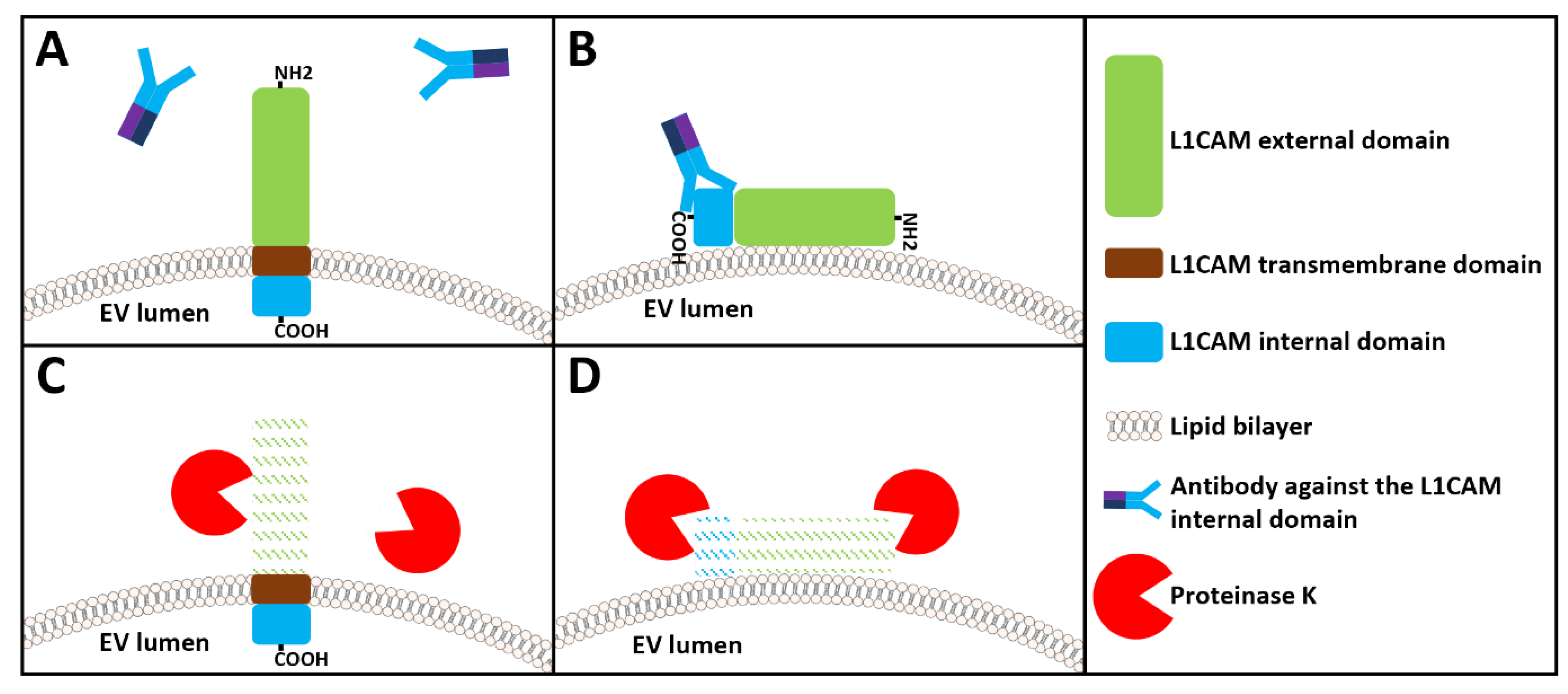

The case of L1CAM for the immunocapture of brain-derived neuronal extracellular vesicles

Unanswered questions regarding the use of L1CAM for the immunocapture of brain-derived neuronal extracellular vesicles

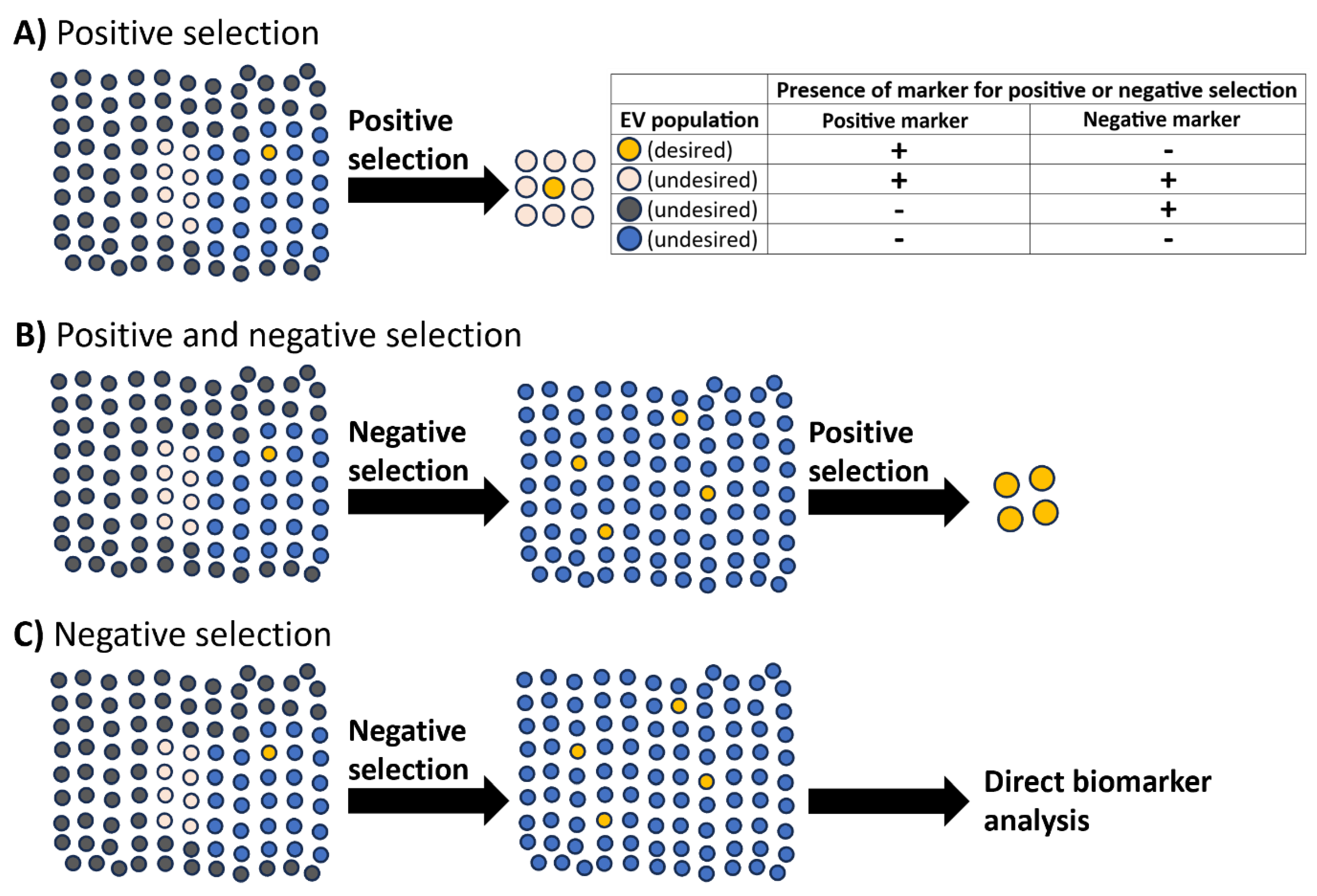

Negative selection by immunodepletion: a key step for enrichment and specificity of rare extracellular vesicle-based biomarkers?

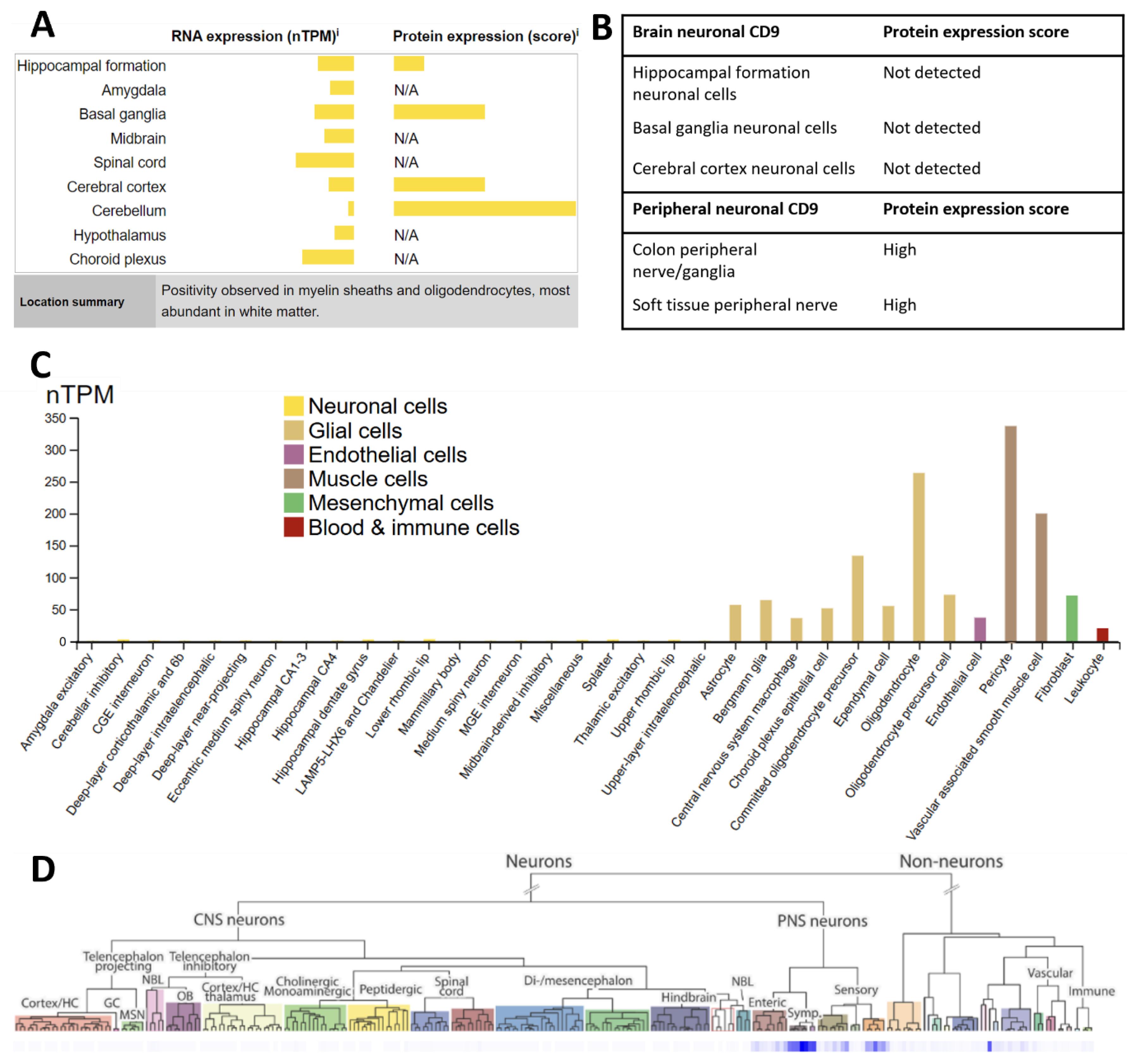

Taking advantage of the heterogeneity of common extracellular vesicle markers for immunodepletion

Untouched isolation to select for tissue-derived extracellular vesicles

Selection of future targets to isolate biomarkers in rare extracellular vesicle populations

Grant information

Data statement

Competing interests

References

- Almousa S, Kim S, Kumar A, Su Y, Singh S, Mishra S, Fonseca MM, Rather HA, Romero-Sandoval EA, Hsu FC, Singh R, Yadav H, Mishra S, Deep G. Bacterial nanovesicles as interkingdom signaling moieties mediating pain hypersensitivity. ACS Nano. 2025 Jan 28;19(3):3210-3225. [CrossRef]

- Amin S, Massoumi H, Tewari D, Roy A, Chaudhuri M, Jazayerli C, Krishan A, Singh M, Soleimani M, Karaca EE, Mirzaei A, Guaiquil VH, Rosenblatt MI, Djalilian AR, Jalilian E. Cell type-specific extracellular vesicles and their impact on health and disease. Int J Mol Sci. 2024 Feb 27;25(5):2730. [CrossRef]

- An J, Park H, Kim J, Park H, Kim TH, Park C, Kim J, Lee MH, Lee T. Extended-gate field-effect transistor consisted of a CD9 aptamer and MXene for exosome detection in human serum. ACS Sens. 2023 Aug 25;8(8):3174-3186.

- Arduise C, Abache T, Li L, Billard M, Chabanon A, Ludwig A, Mauduit P, Boucheix C, Rubinstein E, Le Naour F. Tetraspanins regulate ADAM10-mediated cleavage of TNF-alpha and epidermal growth factor. J Immunol. 2008 Nov 15;181(10):7002-13. [CrossRef]

- Arystarkhova E, Sweadner KJ. Isoform-specific monoclonal antibodies to Na,K-ATPase alpha subunits. Evidence for a tissue-specific post-translational modification of the alpha subunit. J Biol Chem. 1996 Sep 20;271(38):23407-17.

- Ashrafzadeh-Kian S, Figdore D, Larson B, Deters R, Abou-Diwan C, Bornhorst J, Algeciras-Schimnich A. Head-to-head comparison of four plasma neurofilament light chain (NfL) immunoassays. Clin Chim Acta. 2024 Jul 15;561:119817. [CrossRef]

- Athauda D, Gulyani S, Karnati HK, Li Y, Tweedie D, Mustapic M, Chawla S, Chowdhury K, Skene SS, Greig NH, Kapogiannis D, Foltynie T. Utility of neuronal-derived exosomes to examine molecular mechanisms that affect motor function in patients with Parkinson disease: a secondary analysis of the exenatide-pd trial. JAMA Neurol. 2019 Apr 1;76(4):420-429.

- Auber M, Svenningsen P. An estimate of extracellular vesicle secretion rates of human blood cells. J Extracell Biol. 2022 Jun 2;1(6):e46. [CrossRef]

- Banerjee SA, Patterson PH. Schwann cell CD9 expression is regulated by axons. Mol Cell Neurosci. 1995 Oct;6(5):462-73. [CrossRef]

- Banks WA, Sharma P, Bullock KM, Hansen KM, Ludwig N, Whiteside TL. Transport of extracellular vesicles across the blood-brain barrier: brain pharmacokinetics and effects of inflammation. Int J Mol Sci. 2020 Jun 21;21(12):4407. [CrossRef]

- Blommer J, Pitcher T, Mustapic M, Eren E, Yao PJ, Vreones MP, Pucha KA, Dalrymple-Alford J, Shoorangiz R, Meissner WG, Anderson T, Kapogiannis D. Extracellular vesicle biomarkers for cognitive impairment in Parkinson’s disease. Brain. 2023 Jan 5;146(1):195-208. [CrossRef]

- Brambilla D, Sola L, Ferretti AM, Chiodi E, Zarovni N, Fortunato D, Criscuoli M, Dolo V, Giusti I, Murdica V, Kluszczyńska K, Czernek L, Düchler M, Vago R, Chiari M. EV Separation: Release of intact extracellular vesicles immunocaptured on magnetic particles. Anal Chem. 2021 Apr 6;93(13):5476-5483. [CrossRef]

- Bravo-Miana RDC, Arizaga-Echebarria JK, Sabas-Ortega V, Crespillo-Velasco H, Prada A, Castillo-Triviño T, Otaegui D. Tetraspanins, GLAST and L1CAM quantification in single extracellular vesicles from cerebrospinal fluid and serum of people with multiple sclerosis. Biomedicines. 2024 Oct 2;12(10):2245. [CrossRef]

- Cao Z, Du W, Li G, Cao H. DEEPSMP: A deep learning model for predicting the ectodomain shedding events of membrane proteins. J Bioinform Comput Biol. 2020 Jun;18(3):2050017. [CrossRef]

- Chen G, Huang AC, Zhang W, Zhang G, Wu M, Xu W, Yu Z, Yang J, Wang B, Sun H, Xia H, Man Q, Zhong W, Antelo LF, Wu B, Xiong X, Liu X, Guan L, Li T, Liu S, Yang R, Lu Y, Dong L, McGettigan S, Somasundaram R, Radhakrishnan R, Mills G, Lu Y, Kim J, Chen YH, Dong H, Zhao Y, Karakousis GC, Mitchell TC, Schuchter LM, Herlyn M, Wherry EJ, Xu X, Guo W. Exosomal PD-L1 contributes to immunosuppression and is associated with anti-PD-1 response. Nature. 2018 Aug;560(7718):382-386. [CrossRef]

- Chen MM, Lee CY, Leland HA, Lin GY, Montgomery AM, Silletti S. Inside-out regulation of L1 conformation, integrin binding, proteolysis, and concomitant cell migration. Mol Biol Cell. 2010 May 15;21(10):1671-85. [CrossRef]

- Chen Z, Li W, Meng B, Xu C, Huang Y, Li G, Wen Z, Liu J, Mao Z. Neuronal-enriched small extracellular vesicles trigger a PD-L1-mediated broad suppression of T cells in Parkinson’s disease. iScience. 2024 Jun 11;27(7):110243. [CrossRef]

- Cheng L, Vella LJ, Barnham KJ, McLean C, Masters CL, Hill AF. Small RNA fingerprinting of Alzheimer’s disease frontal cortex extracellular vesicles and their comparison with peripheral extracellular vesicles. J Extracell Vesicles. 2020 Jun 4;9(1):1766822. [CrossRef]

- Ciferri MC, Quarto R, Tasso R. extracellular vesicles as biomarkers and therapeutic tools: from pre-clinical to clinical applications. Biology (Basel). 2021 Apr 23;10(5):359. [CrossRef]

- Dagur RS, Liao K, Sil S, Niu F, Sun Z, Lyubchenko YL, Peeples ES, Hu G, Buch S. Neuronal-derived extracellular vesicles are enriched in the brain and serum of HIV-1 transgenic rats. J Extracell Vesicles. 2019 Dec 20;9(1):1703249. [CrossRef]

- de la Torre-Escudero E, Gerlach JQ, Bennett APS, Cwiklinski K, Jewhurst HL, Huson KM, Joshi L, Kilcoyne M, O’Neill S, Dalton JP, Robinson MW. Surface molecules of extracellular vesicles secreted by the helminth pathogen Fasciola hepatica direct their internalisation by host cells. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2019 Jan 18;13(1):e0007087. [CrossRef]

- Dias T, Figueiras R, Vagueiro S, Domingues R, Hung YH, Sethi J, Persia E, Arsène P. An electro-optical platform for the ultrasensitive detection of small extracellular vesicle sub-types and their protein epitope counts. iScience. 2024 Apr 30;27(6):109866. [CrossRef]

- Doh-Ura K, Mekada E, Ogomori K, Iwaki T. Enhanced CD9 expression in the mouse and human brains infected with transmissible spongiform encephalopathies. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2000 Sep;59(9):774-85. [CrossRef]

- Droste M, Tertel T, Jeruschke S, Dittrich R, Kontopoulou E, Walkenfort B, Börger V, Hoyer PF, Büscher AK, Thakur BK, Giebel B. Single extracellular vesicle analysis performed by imaging flow cytometry and nanoparticle tracking analysis evaluate the accuracy of urinary extracellular vesicle preparation techniques differently. Int J Mol Sci. 2021 Nov 18;22(22):12436. [CrossRef]

- Dunlop RA, Banack SA, Cox PA. L1CAM immunocapture generates a unique extracellular vesicle population with a reproducible miRNA fingerprint. RNA Biol. 2023 Jan;20(1):140-148. [CrossRef]

- Dutta S, Hornung S, Kruayatidee A, Maina KN, Del Rosario I, Paul KC, Wong DY, Duarte Folle A, Markovic D, Palma JA, Serrano GE, Adler CH, Perlman SL, Poon WW, Kang UJ, Alcalay RN, Sklerov M, Gylys KH, Kaufmann H, Fogel BL, Bronstein JM, Ritz B, Bitan G. α-Synuclein in blood exosomes immunoprecipitated using neuronal and oligodendroglial markers distinguishes Parkinson’s disease from multiple system atrophy. Acta Neuropathol. 2021 Sep;142(3):495-511.

- Dutta S, Hornung S, Taha HB, Bitan G. Biomarkers for parkinsonian disorders in CNS-originating EVs: promise and challenges. Acta Neuropathol. 2023 May;145(5):515-540. [CrossRef]

- Eitan E, Thornton-Wells T, Elgart K, Erden E, Gershun E, Levine A, Volpert O, Azadeh M, Smith DG, Kapogiannis D. Synaptic proteins in neuron-derived extracellular vesicles as biomarkers for Alzheimer’s disease: novel methodology and clinical proof of concept. Extracell Vesicles Circ Nucl Acids. 2023 Mar;4(1):133-150. [CrossRef]

- Fiandaca MS, Kapogiannis D, Mapstone M, Boxer A, Eitan E, Schwartz JB, Abner EL, Petersen RC, Federoff HJ, Miller BL, Goetzl EJ. Identification of preclinical Alzheimer’s disease by a profile of pathogenic proteins in neurally derived blood exosomes: a case-control study. Alzheimers Dement. 2015 Jun;11(6):600-7.e1. [CrossRef]

- Fordjour FK, Abuelreich S, Hong X, Chatterjee E, Lallai V, Ng M, Saftics A, Deng F, Carnel-Amar N, Wakimoto H, Shimizu K, Bautista M, Phu TA, Vu NK, Geiger PC, Raffai RL, Fowler CD, Das S, Christenson LK, Jovanovic-Talisman T, Gould SJ. Exomap1 mouse: a transgenic model for in vivo studies of exosome biology. Extracell Vesicle. 2023 Dec;2:100030. [CrossRef]

- Foroni C, Zarovni N, Bianciardi L, Bernardi S, Triggiani L, Zocco D, Venturella M, Chiesi A, Valcamonico F, Berruti A. When less is more: specific capture and analysis of tumor exosomes in plasma increases the sensitivity of liquid biopsy for comprehensive detection of multiple androgen receptor phenotypes in advanced prostate cancer patients. Biomedicines. 2020 May 22;8(5):131. [CrossRef]

- Fortunato D, Giannoukakos S, Giménez-Capitán A, Hackenberg M, Molina-Vila MA, Zarovni N. Selective isolation of extracellular vesicles from minimally processed human plasma as a translational strategy for liquid biopsies. Biomark Res. 2022 Aug 7;10(1):57. [CrossRef]

- Ganesh S, Lam TT, Garcia-Milian R, Cyril D’Souza D, Nairn AC, Elgert K, Eitan E, Ranganathan M. Peripheral signature of altered synaptic integrity in young onset cannabis use disorder: A proteomic study of circulating extracellular vesicles. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2023 Sep-Oct;24(7):603-613.

- Gelibter S, Marostica G, Mandelli A, Siciliani S, Podini P, Finardi A, Furlan R. The impact of storage on extracellular vesicles: A systematic study. J Extracell Vesicles. 2022 Feb;11(2):e12162.

- Gilboa T, Ter-Ovanesyan D, Wang SC, Whiteman S, Kannarkat GT, Church GM, Chen-Plotkin AS, Walt DR. Measurement of α-synuclein as protein cargo in plasma extracellular vesicles. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2024 Nov 5;121(45):e2408949121. [CrossRef]

- Girbes Minguez M, Wolters-Eisfeld G, Lutz D, Buck F, Schachner M, Kleene R. The cell adhesion molecule L1 interacts with nuclear proteins via its intracellular domain. FASEB J. 2020 Aug;34(8):9869-9883.

- Gomes DE, Witwer KW. L1CAM-associated extracellular vesicles: a systematic review of nomenclature, sources, separation, and characterization. J Extracell Biol. 2022 Mar;1(3):e35. [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez-López MD, Gilsanz A, Yáñez-Mó M, Ovalle S, Lafuente EM, Domínguez C, Monk PN, González-Alvaro I, Sánchez-Madrid F, Cabañas C. The sheddase activity of ADAM17/TACE is regulated by the tetraspanin CD9. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2011 Oct;68(19):3275-92. [CrossRef]

- Hoshino A, Costa-Silva B, Shen TL, Rodrigues G, Hashimoto A, Tesic Mark M, Molina H, Kohsaka S, Di Giannatale A, Ceder S, Singh S, Williams C, Soplop N, Uryu K, Pharmer L, King T, Bojmar L, Davies AE, Ararso Y, Zhang T, …Lyden D. Tumour exosome integrins determine organotropic metastasis. Nature. 2015 Nov 19;527(7578):329-35. [CrossRef]

- Hoshino A, Kim HS, Bojmar L, Gyan KE, Cioffi M, Hernandez J, Zambirinis CP, Rodrigues G, Molina H, Heissel S, Mark MT, Steiner L, Benito-Martin A, Lucotti S, Di Giannatale A, Offer K, Nakajima M, Williams C, Nogués L, Pelissier Vatter FA, …Lyden D. Extracellular vesicle and particle biomarkers define multiple human cancers. Cell. 2020 Aug 20;182(4):1044-1061.e18. [CrossRef]

- Hotta N, Tadokoro T, Henry J, Koga D, Kawata K, Ishida H, Oguma Y, Hirata A, Mitsuhashi M, Yoshitani K. Monitoring of post-brain injuries by measuring plasma levels of neuron-derived extracellular vesicles. Biomark Insights. 2022 Oct 26;17:11772719221128145. [CrossRef]

- Huang WY, Wu KP. SheddomeDB 2023: A Revision of an ectodomain shedding database based on a comprehensive literature review and online resources. J Proteome Res. 2023 Aug 4;22(8):2570-2576.

- Huang Y, Arab T, Russell AE, Mallick ER, Nagaraj R, Gizzie E, Redding-Ochoa J, Troncoso JC, Pletnikova O, Turchinovich A, Routenberg DA, Witwer KW. Toward a human brain extracellular vesicle atlas: characteristics of extracellular vesicles from different brain regions, including small RNA and protein profiles. Interdiscip Med. 2023 Oct;1(4):e20230016. [CrossRef]

- Huang Y, Feng J, Xu J, Dong L, Su W, Li B, Witwer KW, Zheng L. Associations of age and sex with characteristics of extracellular vesicles and protein-enriched fractions of blood plasma. Aging Cell. 2025 Jan;24(1):e14356. [CrossRef]

- Ishibashi T, Ding L, Ikenaka K, Inoue Y, Miyado K, Mekada E, Baba H. Tetraspanin protein CD9 is a novel paranodal component regulating paranodal junctional formation. J Neurosci. 2004 Jan 7;24(1):96-102. [CrossRef]

- Jeyaram A, Jay SM. Preservation and storage stability of extracellular vesicles for therapeutic applications. AAPS J. 2017 Nov 27;20(1):1. [CrossRef]

- Johnsen KB, Gudbergsson JM, Andresen TL, Simonsen JB. What is the blood concentration of extracellular vesicles? Implications for the use of extracellular vesicles as blood-borne biomarkers of cancer. Biochim Biophys Acta Rev Cancer. 2019 Jan;1871(1):109-116. [CrossRef]

- Jouannet S, Saint-Pol J, Fernandez L, Nguyen V, Charrin S, Boucheix C, Brou C, Milhiet PE, Rubinstein E. TspanC8 tetraspanins differentially regulate the cleavage of ADAM10 substrates, Notch activation and ADAM10 membrane compartmentalization. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2016 May;73(9):1895-915. [CrossRef]

- Kabe Y, Sakamoto S, Hatakeyama M, Yamaguchi Y, Suematsu M, Itonaga M, Handa H. Application of high-performance magnetic nanobeads to biological sensing devices. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2019 Mar;411(9):1825-1837. [CrossRef]

- Kagawa T, Mekada E, Shishido Y, Ikenaka K. Immune system-related CD9 is expressed in mouse central nervous system myelin at a very late stage of myelination. J Neurosci Res. 1997 Oct 15;50(2):312-20. [CrossRef]

- Kaprielian Z, Cho KO, Hadjiargyrou M, Patterson PH. CD9, a major platelet cell surface glycoprotein, is a ROCA antigen and is expressed in the nervous system. J Neurosci. 1995 Jan;15(1 Pt 2):562-73. [CrossRef]

- Karimi N, Dalirfardouei R, Dias T, Lötvall J, Lässer C. Tetraspanins distinguish separate extracellular vesicle subpopulations in human serum and plasma - Contributions of platelet extracellular vesicles in plasma samples. J Extracell Vesicles. 2022 May;11(5):e12213. [CrossRef]

- Khanna K, Salmond N, Halvaei S, Johnson A, Williams KC. Separation and isolation of CD9-positive extracellular vesicles from plasma using flow cytometry. Nanoscale Adv. 2023 Jul 13;5(17):4435-4446. [CrossRef]

- Kluge A, Bunk J, Schaeffer E, Drobny A, Xiang W, Knacke H, Bub S, Lückstädt W, Arnold P, Lucius R, Berg D, Zunke F. Detection of neuron-derived pathological α-synuclein in blood. Brain. 2022 Sep 14;145(9):3058-3071. [CrossRef]

- Ko J, Hemphill MA, Gabrieli D, Wu L, Yelleswarapu V, Lawrence G, Pennycooke W, Singh A, Meaney DF, Issadore D. Smartphone-enabled optofluidic exosome diagnostic for concussion recovery. Sci Rep. 2016 Aug 8;6:31215. [CrossRef]

- Ko J, Wang Y, Sheng K, Weitz DA, Weissleder R. Sequencing-based protein analysis of single extracellular vesicles. ACS Nano. 2021 Mar 23;15(3):5631-5638. [CrossRef]

- Kugeratski FG, Hodge K, Lilla S, McAndrews KM, Zhou X, Hwang RF, Zanivan S, Kalluri R. Quantitative proteomics identifies the core proteome of exosomes with syntenin-1 as the highest abundant protein and a putative universal biomarker. Nat Cell Biol. 2021 Jun;23(6):631-641. [CrossRef]

- Kuhn PH, Koroniak K, Hogl S, Colombo A, Zeitschel U, Willem M, Volbracht C, Schepers U, Imhof A, Hoffmeister A, Haass C, Roßner S, Bräse S, Lichtenthaler SF. Secretome protein enrichment identifies physiological BACE1 protease substrates in neurons. EMBO J. 2012 Jun 22;31(14):3157-68. [CrossRef]

- Kumar A, Sharma M, Su Y, Singh S, Hsu FC, Neth BJ, Register TC, Blennow K, Zetterberg H, Craft S, Deep G. Small extracellular vesicles in plasma reveal molecular effects of modified Mediterranean-ketogenic diet in participants with mild cognitive impairment. Brain Commun. 2022 Oct 19;4(6):fcac262. [CrossRef]

- Ladang A, Kovacs S, Lengelé L, Locquet M, Reginster JY, Bruyère O, Cavalier E. Neurofilament light chain concentration in an aging population. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2022 Feb;34(2):331-339. [CrossRef]

- Li Y, He X, Li Q, Lai H, Zhang H, Hu Z, Li Y, Huang S. EV-origin: Enumerating the tissue-cellular origin of circulating extracellular vesicles using exLR profile. Comput Struct Biotechnol J. 2020 Oct 14;18:2851-2859. [CrossRef]

- Liu CJ, Xie GY, Miao YR, Xia M, Wang Y, Lei Q, Zhang Q, Guo AY. EVAtlas: a comprehensive database for ncRNA expression in human extracellular vesicles. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022 Jan 7;50(D1):D111-D117. [CrossRef]

- Llorens-Bobadilla E, Zhao S, Baser A, Saiz-Castro G, Zwadlo K, Martin-Villalba A. Single-cell transcriptomics reveals a population of dormant neural stem cells that become activated upon brain injury. Cell Stem Cell. 2015 Sep 3;17(3):329-40. [CrossRef]

- Lobete M, Salinas T, Izquierdo-Bermejo S, Socas S, Oset-Gasque MJ, Martín-de-Saavedra MD. A methodology to globally assess ectodomain shedding using soluble fractions from the mouse brain. Front Psychiatry. 2024 Jun 19;15:1367526. [CrossRef]

- Malong L, Napoli I, Casal G, White IJ, Stierli S, Vaughan A, Cattin AL, Burden JJ, Hng KI, Bossio A, Flanagan A, Zhao HT, Lloyd AC. Characterization of the structure and control of the blood-nerve barrier identifies avenues for therapeutic delivery. Dev Cell. 2023 Feb 6;58(3):174-191.e8. [CrossRef]

- Małys MS, Köller MC, Papp K, Aigner C, Dioso D, Mucher P, Schachner H, Bonelli M, Haslacher H, Rees AJ, Kain R. Small extracellular vesicles are released ex vivo from platelets into serum and from residual blood cells into stored plasma. J Extracell Biol. 2023 May 12;2(5):e88. [CrossRef]

- Maretzky T, Schulte M, Ludwig A, Rose-John S, Blobel C, Hartmann D, Altevogt P, Saftig P, Reiss K. L1 is sequentially processed by two differently activated metalloproteases and presenilin/gamma-secretase and regulates neural cell adhesion, cell migration, and neurite outgrowth. Mol Cell Biol. 2005 Oct;25(20):9040-53. [CrossRef]

- Matamoros-Angles A, Karadjuzovic E, Mohammadi B, Song F, Brenna S, Meister SC, Siebels B, Voß H, Seuring C, Ferrer I, Schlüter H, Kneussel M, Altmeppen HC, Schweizer M, Puig B, Shafiq M, Glatzel M. Efficient enzyme-free isolation of brain-derived extracellular vesicles. J Extracell Vesicles. 2024 Nov;13(11):e70011.

- Mondal SK, Whiteside TL. Immunoaffinity-based isolation of melanoma cell-derived and T cell-derived exosomes from plasma of melanoma patients. Methods Mol Biol. 2021; 2265:305-321.

- Morton MC, Neckles VN, Seluzicki CM, Holmberg JC, Feliciano DM. Neonatal subventricular zone neural stem cells release extracellular vesicles that act as a microglial morphogen. Cell Rep. 2018 Apr 3;23(1):78-89. [CrossRef]

- Mustapic M, Eitan E, Werner JK Jr, Berkowitz ST, Lazaropoulos MP, Tran J, Goetzl EJ, Kapogiannis D. Plasma extracellular vesicles enriched for neuronal origin: a potential window into brain pathologic processes. Front Neurosci. 2017 May 22;11:278. [CrossRef]

- Mustapic M, Tran J, Craft S, Kapogiannis D. Extracellular vesicle biomarkers track cognitive changes following intranasal insulin in Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2019;69(2):489-498. [CrossRef]

- Nakamura Y, Iwamoto R, Mekada E. Expression and distribution of CD9 in myelin of the central and peripheral nervous systems. Am J Pathol. 1996 Aug;149(2):575-83.

- Newman LA, Useckaite Z, Wu T, Sorich MJ, Rowland A. Analysis of extracellular vesicle and contaminant markers in blood derivatives using multiple reaction monitoring. Methods Mol Biol. 2023;2628:301-320.

- Nogueras-Ortiz CJ, Eren E, Yao P, Calzada E, Dunn C, Volpert O, Delgado-Peraza F, Mustapic M, Lyashkov A, Rubio FJ, Vreones M, Cheng L, You Y, Hill AF, Ikezu T, Eitan E, Goetzl EJ, Kapogiannis D. Single-extracellular vesicle (EV) analyses validate the use of L1 Cell Adhesion Molecule (L1CAM) as a reliable biomarker of neuron-derived EVs. J Extracell Vesicles. 2024 Jun;13(6):e12459. [CrossRef]

- Norman M, Ter-Ovanesyan D, Trieu W, Lazarovits R, Kowal EJK, Lee JH, Chen-Plotkin AS, Regev A, Church GM, Walt DR. L1CAM is not associated with extracellular vesicles in human cerebrospinal fluid or plasma. Nat Methods. 2021 Jun;18(6):631-634. [CrossRef]

- Notarangelo M, Zucal C, Modelska A, Pesce I, Scarduelli G, Potrich C, Lunelli L, Pederzolli C, Pavan P, la Marca G, Pasini L, Ulivi P, Beltran H, Demichelis F, Provenzani A, Quattrone A, D’Agostino VG. Ultrasensitive detection of cancer biomarkers by nickel-based isolation of polydisperse extracellular vesicles from blood. EBioMedicine. 2019 May;43:114-126. [CrossRef]

- Paget D, Checa A, Zöhrer B, Heilig R, Shanmuganathan M, Dhaliwal R, Johnson E, Jørgensen MM, Bæk R; Oxford Acute Myocardial Infarction Study (OxAMI); Wheelock CE, Channon KM, Fischer R, Anthony DC, Choudhury RP, Akbar N. Comparative and integrated analysis of plasma extracellular vesicle isolation methods in healthy volunteers and patients following myocardial infarction. J Extracell Biol. 2022 Nov 23;1(11):e66. [CrossRef]

- Polanco JC, Li C, Durisic N, Sullivan R, Götz J. Exosomes taken up by neurons hijack the endosomal pathway to spread to interconnected neurons. Acta Neuropathol Commun. 2018 Feb 15;6(1):10. [CrossRef]

- Ramirez MI, Amorim MG, Gadelha C, Milic I, Welsh JA, Freitas VM, Nawaz M, Akbar N, Couch Y, Makin L, Cooke F, Vettore AL, Batista PX, Freezor R, Pezuk JA, Rosa-Fernandes L, Carreira ACO, Devitt A, Jacobs L, Silva IT, Coakley G, Nunes DN, Carter D, Palmisano G, Dias-Neto E. Technical challenges of working with extracellular vesicles. Nanoscale. 2018 Jan 18;10(3):881-906. [CrossRef]

- Reyes R, Cardeñes B, Machado-Pineda Y, Cabañas C. Tetraspanin CD9: A key regulator of cell adhesion in the immune system. Front Immunol. 2018 Apr 30;9:863. [CrossRef]

- Rissin DM, Kan CW, Campbell TG, Howes SC, Fournier DR, Song L, Piech T, Patel PP, Chang L, Rivnak AJ, Ferrell EP, Randall JD, Provuncher GK, Walt DR, Duffy DC. Single-molecule enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay detects serum proteins at subfemtomolar concentrations. Nat Biotechnol. 2010 Jun;28(6):595-9. [CrossRef]

- Roy D, Pascher A, Juratli MA, Sporn JC. The potential of aptamer-mediated liquid biopsy for early detection of cancer. Int J Mol Sci. 2021 May 25;22(11):5601. [CrossRef]

- Rufino-Ramos D, Lule S, Mahjoum S, Ughetto S, Cristopher Bragg D, Pereira de Almeida L, Breakefield XO, Breyne K. Using genetically modified extracellular vesicles as a non-invasive strategy to evaluate brain-specific cargo. Biomaterials. 2022 Feb;281:121366. [CrossRef]

- Rufino-Ramos D, Leandro K, Perdigão PRL, O’Brien K, Pinto MM, Santana MM, van Solinge TS, Mahjoum S, Breakefield XO, Breyne K, Pereira de Almeida L. Extracellular communication between brain cells through functional transfer of Cre mRNA mediated by extracellular vesicles. Mol Ther. 2023 Jul 5;31(7):2220-2239. [CrossRef]

- Salmond N, Khanna K, Owen GR, Williams KC. Nanoscale flow cytometry for immunophenotyping and quantitating extracellular vesicles in blood plasma. Nanoscale. 2021 Jan 28;13(3):2012-2025. [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Arias JC, Candlish RC, van der Slagt E, Swayne LA. Pannexin 1 regulates dendritic protrusion dynamics in immature cortical neurons. eNeuro. 2020 Aug 26;7(4):ENEURO.0079-20.2020. [CrossRef]

- Schaeffer E, Kluge A, Schulte C, Deuschle C, Bunk J, Welzel J, Maetzler W, Berg D. association of misfolded α-synuclein derived from neuronal exosomes in blood with parkinson’s disease diagnosis and duration. J Parkinsons Dis. 2024;14(4):667-679. [CrossRef]

- Schmidt C, Künemund V, Wintergerst ES, Schmitz B, Schachner M. CD9 of mouse brain is implicated in neurite outgrowth and cell migration in vitro and is associated with the alpha 6/beta 1 integrin and the neural adhesion molecule L1. J Neurosci Res. 1996 Jan 1;43(1):12-31. [CrossRef]

- Sharafeldin M, Yan S, Jiang C, Tofaris GK, Davis JJ. Alternating magnetic field-promoted nanoparticle mixing: the on-chip immunocapture of serum neuronal exosomes for Parkinson’s disease diagnostics. Anal Chem. 2023 May 23;95(20):7906-7913. [CrossRef]

- Spitzberg JD, Ferguson S, Yang KS, Peterson HM, Carlson JCT, Weissleder R. Multiplexed analysis of EV reveals specific biomarker composition with diagnostic impact. Nat Commun. 2023 Mar 4;14(1):1239. [CrossRef]

- Su X, Júnior GPO, Marie AL, Gregus M, Figueroa-Navedo A, Ghiran IC, Ivanov AR. Enhanced proteomic profiling of human plasma-derived extracellular vesicles through charge-based fractionation to advance biomarker discovery potential. J Extracell Vesicles. 2024 Dec;13(12):e70024. [CrossRef]

- Taha HB. Rethinking the reliability and accuracy of biomarkers in CNS-originating EVs for Parkinson’s disease and multiple system atrophy. Front Neurol. 2023 Sep 5;14:1192115. [CrossRef]

- Théry C, Witwer KW, Aikawa E, Alcaraz MJ, Anderson JD, Andriantsitohaina R, Antoniou A, Arab T, Archer F, Atkin-Smith GK, Ayre DC, Bach JM, Bachurski D, Baharvand H, Balaj L, Baldacchino S, Bauer NN, Baxter AA, Bebawy M, Beckham C, …Zuba-Surma EK. Minimal information for studies of extracellular vesicles 2018 (MISEV2018): a position statement of the International Society for Extracellular Vesicles and update of the MISEV2014 guidelines. J Extracell Vesicles. 2018 Nov 23;7(1):1535750. [CrossRef]

- Tien WS, Chen JH, Wu KP. SheddomeDB: the ectodomain shedding database for membrane-bound shed markers. BMC Bioinformatics. 2017 Mar 14;18(Suppl 3):42. [CrossRef]

- Tole S, Patterson PH. Distribution of CD9 in the developing and mature rat nervous system. Dev Dyn. 1993 Jun;197(2):94-106. [CrossRef]

- Tordoff E, Allen J, Elgart K, Elsherbini A, Kalia V, Wu H, Eren E, Kapogiannis D, Gololobova O, Witwer K, Volpert O, Eitan E. A novel multiplexed immunoassay for surface-exposed proteins in plasma extracellular vesicles. J Extracell Vesicles. 2024 Nov;13(11):e70007. [CrossRef]

- Tóth EÁ, Turiák L, Visnovitz T, Cserép C, Mázló A, Sódar BW, Försönits AI, Petővári G, Sebestyén A, Komlósi Z, Drahos L, Kittel Á, Nagy G, Bácsi A, Dénes Á, Gho YS, Szabó-Taylor KÉ, Buzás EI. Formation of a protein corona on the surface of extracellular vesicles in blood plasma. J Extracell Vesicles. 2021 Sep;10(11):e12140. [CrossRef]

- Trivedi R, Bhat KP. Liquid biopsy: creating opportunities in brain space. Br J Cancer. 2023 Nov;129(11):1727-1746. [CrossRef]

- Truffi M, Garofalo M, Ricciardi A, Cotta Ramusino M, Perini G, Scaranzin S, Gastaldi M, Albasini S, Costa A, Chiavetta V, Corsi F, Morasso C, Gagliardi S. Neurofilament-light chain quantification by Simoa and Ella in plasma from patients with dementia: a comparative study. Sci Rep. 2023 Mar 10;13(1):4041. [CrossRef]

- Tüshaus J, Müller SA, Kataka ES, Zaucha J, Sebastian Monasor L, Su M, Güner G, Jocher G, Tahirovic S, Frishman D, Simons M, Lichtenthaler SF. An optimized quantitative proteomics method establishes the cell type-resolved mouse brain secretome. EMBO J. 2020 Oct 15;39(20):e105693. [CrossRef]

- Tutrone R, Lowentritt B, Neuman B, Donovan MJ, Hallmark E, Cole TJ, Yao Y, Biesecker C, Kumar S, Verma V, Sant GR, Alter J, Skog J. ExoDx prostate test as a predictor of outcomes of high-grade prostate cancer - an interim analysis. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2023 Sep;26(3):596-601. [CrossRef]

- Uhlén M, Fagerberg L, Hallström BM, Lindskog C, Oksvold P, Mardinoglu A, Sivertsson Å, Kampf C, Sjöstedt E, Asplund A, Olsson I, Edlund K, Lundberg E, Navani S, Szigyarto CA, Odeberg J, Djureinovic D, Takanen JO, Hober S, Alm T, …Pontén F. Proteomics. Tissue-based map of the human proteome. Science. 2015 Jan 23;347(6220):1260419. [CrossRef]

- UniProt Consortium. UniProt: the universal protein knowledgebase in 2025. Nucleic Acids Res. 2025 Jan 6;53(D1):D609-D617.

- Vassileff N, Spiers JG, Lee JD, Woodruff TM, Ebrahimie E, Mohammadi Dehcheshmeh M, Hill AF, Cheng L. A panel of mirna biomarkers common to serum and brain-derived extracellular vesicles identified in mouse model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Mol Neurobiol. 2024 Aug;61(8):5901-5915. [CrossRef]

- van Niel G, D’Angelo G, Raposo G. Shedding light on the cell biology of extracellular vesicles. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2018 Apr;19(4):213-228. [CrossRef]

- Welsh JA, Goberdhan DCI, O’Driscoll L, Buzas EI, Blenkiron C, Bussolati B, Cai H, Di Vizio D, Driedonks TAP, Erdbrügger U, Falcon-Perez JM, Fu QL, Hill AF, Lenassi M, Lim SK, Mahoney MG, Mohanty S, Möller A, Nieuwland R, Ochiya T, …Witwer KW. Minimal information for studies of extracellular vesicles (MISEV2023): from basic to advanced approaches. J Extracell Vesicles. 2024 Feb;13(2):e12404. doi: 10.1002/jev2.12404. Erratum in: J Extracell Vesicles. 2024 May;13(5):e12451. [CrossRef]

- Xue F, Chen Y, Wen Y, Abhange K, Zhang W, Cheng G, Quinn Z, Mao W, Wan Y. Isolation of extracellular vesicles with multivalent aptamers. Analyst. 2021 Jan 4;146(1):253-261.

- Yan S, Jiang C, Davis JJ, Tofaris GK. Methodological considerations in neuronal extracellular vesicle isolation for α-synuclein biomarkers. Brain. 2023 Nov 2;146(11):e95-e97. [CrossRef]

- Yang Y, Boza-Serrano A, Dunning CJR, Clausen BH, Lambertsen KL, Deierborg T. Inflammation leads to distinct populations of extracellular vesicles from microglia. J Neuroinflammation. 2018 May 28;15(1):168. [CrossRef]

- Yildizhan Y, Vajrala VS, Geeurickx E, Declerck C, Duskunovic N, De Sutter D, Noppen S, Delport F, Schols D, Swinnen JV, Eyckerman S, Hendrix A, Lammertyn J, Spasic D. FO-SPR biosensor calibrated with recombinant extracellular vesicles enables specific and sensitive detection directly in complex matrices. J Extracell Vesicles. 2021 Feb;10(4):e12059. [CrossRef]

- You Y, Zhang Z, Sultana N, Ericsson M, Martens YA, Sun M, Kanekiyo T, Ikezu S, Shaffer SA, Ikezu T. ATP1A3 as a target for isolating neuron-specific extracellular vesicles from human brain and biofluids. Sci Adv. 2023 Sep 15;9(37):eadi3647.

- Yu ZL, Liu XC, Wu M, Shi S, Fu QY, Jia J, Chen G. Untouched isolation enables targeted functional analysis of tumour-cell-derived extracellular vesicles from tumour tissues. J Extracell Vesicles. 2022 Apr;11(4):e12214. [CrossRef]

- Zarovni N, Mladenović D, Brambilla D, Panico F, Chiari M. Stoichiometric constraints for detection of EV-borne biomarkers in blood. J Extracell Vesicles. 2025 Feb;14(2):e70034. [CrossRef]

- Zanirati G, Dos Santos PG, Alcará AM, Bruzzo F, Ghilardi IM, Wietholter V, Xavier FAC, Gonçalves JIB, Marinowic D, Shetty AK, da Costa JC. Extracellular vesicles: the next generation of biomarkers and treatment for central nervous system diseases. Int J Mol Sci. 2024 Jul 5;25(13):7371. [CrossRef]

- Zeisel A, Hochgerner H, Lönnerberg P, Johnsson A, Memic F, van der Zwan J, Häring M, Braun E, Borm LE, La Manno G, Codeluppi S, Furlan A, Lee K, Skene N, Harris KD, Hjerling-Leffler J, Arenas E, Ernfors P, Marklund U, Linnarsson S. Molecular architecture of the mouse nervous system. Cell. 2018 Aug 9;174(4):999-1014.e22. [CrossRef]

- Zhang K, Yue Y, Wu S, Liu W, Shi J, Zhang Z. Rapid capture and nondestructive release of extracellular vesicles using aptamer-based magnetic isolation. ACS Sens. 2019 May 24;4(5):1245-1251. [CrossRef]

- Zhao Z, Fan J, Hsu YS, Lyon CJ, Ning B, Hu TY. Extracellular vesicles as cancer liquid biopsies: from discovery, validation, to clinical application. Lab Chip. 2019 Mar 27;19(7):1114-1140. [CrossRef]

- Zhou E, Li Y, Wu F, Guo M, Xu J, Wang S, Tan Q, Ma P, Song S, Jin Y. Circulating extracellular vesicles are effective biomarkers for predicting response to cancer therapy. EBioMedicine. 2021 May;67:103365. [CrossRef]

| Protein | Highest expression level in CNS neurons | CNS neuron subtype showing highest expression | Highest expression level in PNS neurons | PNS neuron subtype showing highest expression | Concentration in human plasma |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L1CAM | 2.3 |

Cholinergic neurons, hindbrain (rhombencephalon) | 7.4 | Cholinergic enteric neurons (neural crest) | 13 ng/ml |

| VAMP2 | 15.7 | Excitatory neurons, hindbrain (rhombencephalon) | 13.0 | Noradrenergic erector muscle neurons (neural crest) | 5.2 ng/ml |

| β-III-tubulin | 18.3 | Cholinergic neurons, septal nucleus, Meissnert and diagonal band (diencephalon) | 115.1 | Noradrenergic neurons, sympathetic (neural crest) | 71 ng/ml |

| GAP43 | 42.7 | Cholinergic neurons, septal nucleus, Meissnert and diagonal band (diencephalon) | 79.7 | Noradrenergic erector muscle neurons (neural crest) | 0.029 ng/ml |

| CD9 | 0.9 | Central canal neurons, spinal cord (spinal cord) | 79.7 | Noradrenergic erector muscle neurons (neural crest) | 4.2 ng/ml |

| Publication | Organism | CD9 expression summary and detection method |

|---|---|---|

| Banerjee and Patterson, 1995 | Rat (neonatal and embryonic) |

|

| Doh-Uhra et al., 2000 | Mouse and human (adult) |

|

| Ishibashi et al., 2004 | Mouse (8 weeks old) |

|

| Kagawa et al., 1997 | Mouse (postnatal day 10 to adults) |

|

| Kaprielian et al., 1995 | Rat (adult) |

|

| Llorens-Bobadilla et al., 2015 | Mouse (8-12 weeks old) |

|

| Morton et al., 2018 | Mouse (neonatal) |

|

| Nakamura et al., 1996 | Human (adult) |

|

| Polanco et al., 2018 | Mouse (embryonic) |

|

| Sanchez-Arias et al., 2020 | Mouse (neonatal) |

|

| Schmidt et al., 1996 | Rats (11-day old embryos, postnatal day 4, and adult) and mouse (6 day old) |

|

| Tole and Patterson, 1993 | Rat (embryonic and adult) |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).