Submitted:

01 January 2026

Posted:

04 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Need of Yield Prediction

1.2. Problem Statement

- Focus on single-model approaches.

- Are restricted to short-term forecasting horizons.

- Ignore yield instability and volatility characteristics.

- Lack systematic comparison across statistical, ML, and DL models.

1.3. Contribution of the Study

- Proposes a unified hybrid artificial intelligence framework combining statistical ML and DL models for crop yield forecasting.

- Performs a systematic comparison of classical models (ARIMA, ETS), volatility-based models (Generalized autoregressive conditional heteroscedasticity (GARCH family)), ML models (ANN, support vector machine (SVM), partial least squares (PLS)), and deep learning models (long-short term memory (LSTM)).

- Introduces signal decomposition-based hybrid models (Wavelet-ANN and empirical mode decomposition (EMD)-ANN) to handle nonstationary yield series.

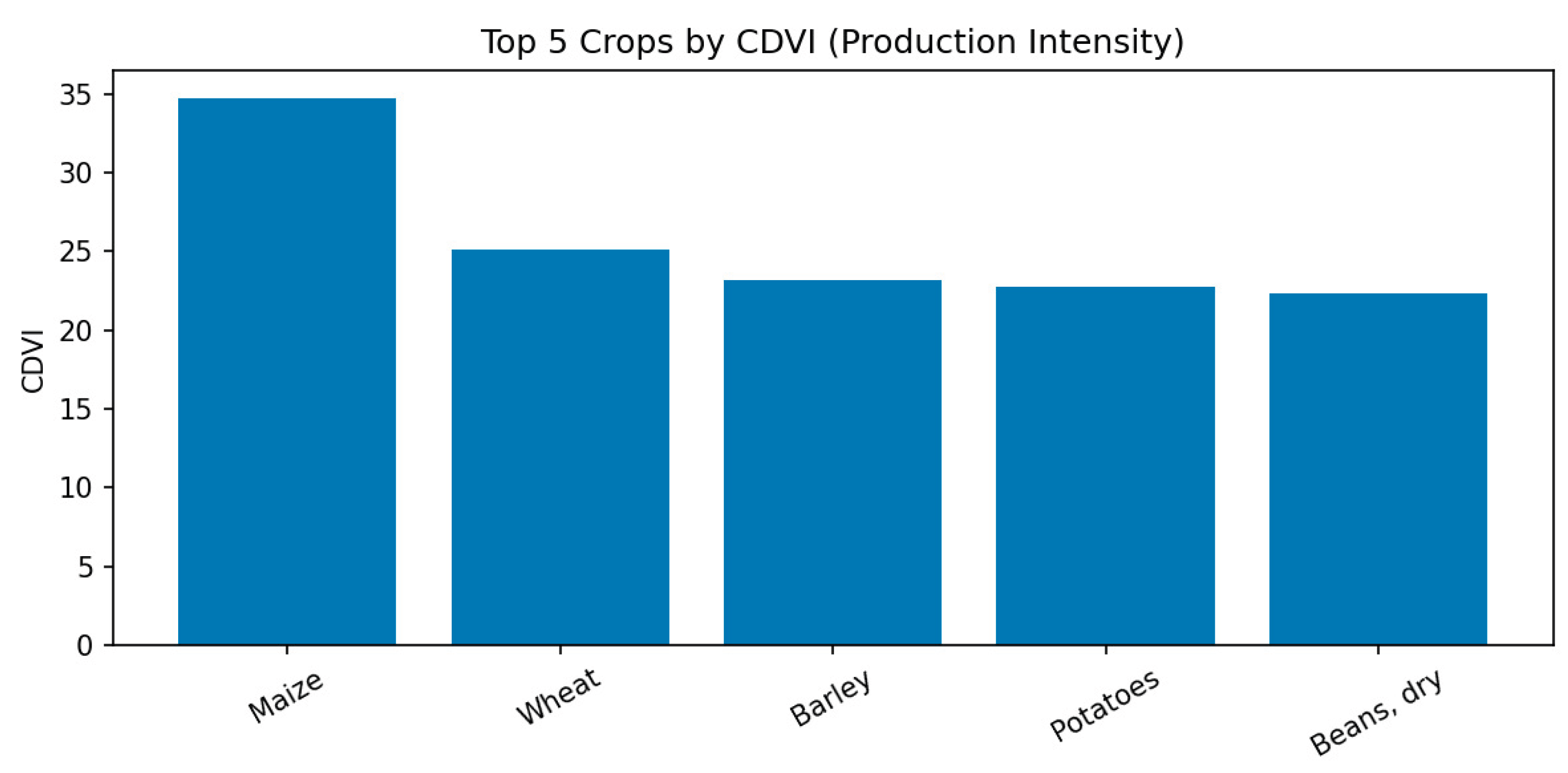

- Incorporates yield instability and heteroscedasticity diagnostics using Cuddy–Della Valle Index (CDVI) and autoregressive conditional heteroscedasticity- lagrange multiplier (ARCH-LM) tests.

- Evaluates model performance using various performance evaluation metrics root mean squared error (RMSE), mean absolute error (MAE), r-squared (R²), and mean absolute percentage error (MAPE).

- Generates long-term (20-year) forecasts for multiple crops, which are rarely addressed in existing literature.

2. Literature Review

3. Methods and Materials

3.1. Dataset Description

- Temporal coverage: Multiple decades (annual frequency)

- Spatial scope: International-level aggregated crop yields

- Data type: Time-series

- Source: Government agricultural databases - UNFAO (2025)

- Dependent Variable: Crop yield (tonnes per hectare)

-

Independent Variables:

- Lagged crop yield values (time-lag features)

- Decomposed components (trend and residuals from Wavelet and EMD)

-

Volatility measures (for GARCH-based models)

- Climatic and economic variables are not explicitly included; instead, their effects are implicitly captured through temporal yield dynamics.

3.2. Preprocessing Steps

- Handling missing values using interpolation

- Normalization for machine learning and deep learning models

- Train–test split (80:20) preserving temporal order

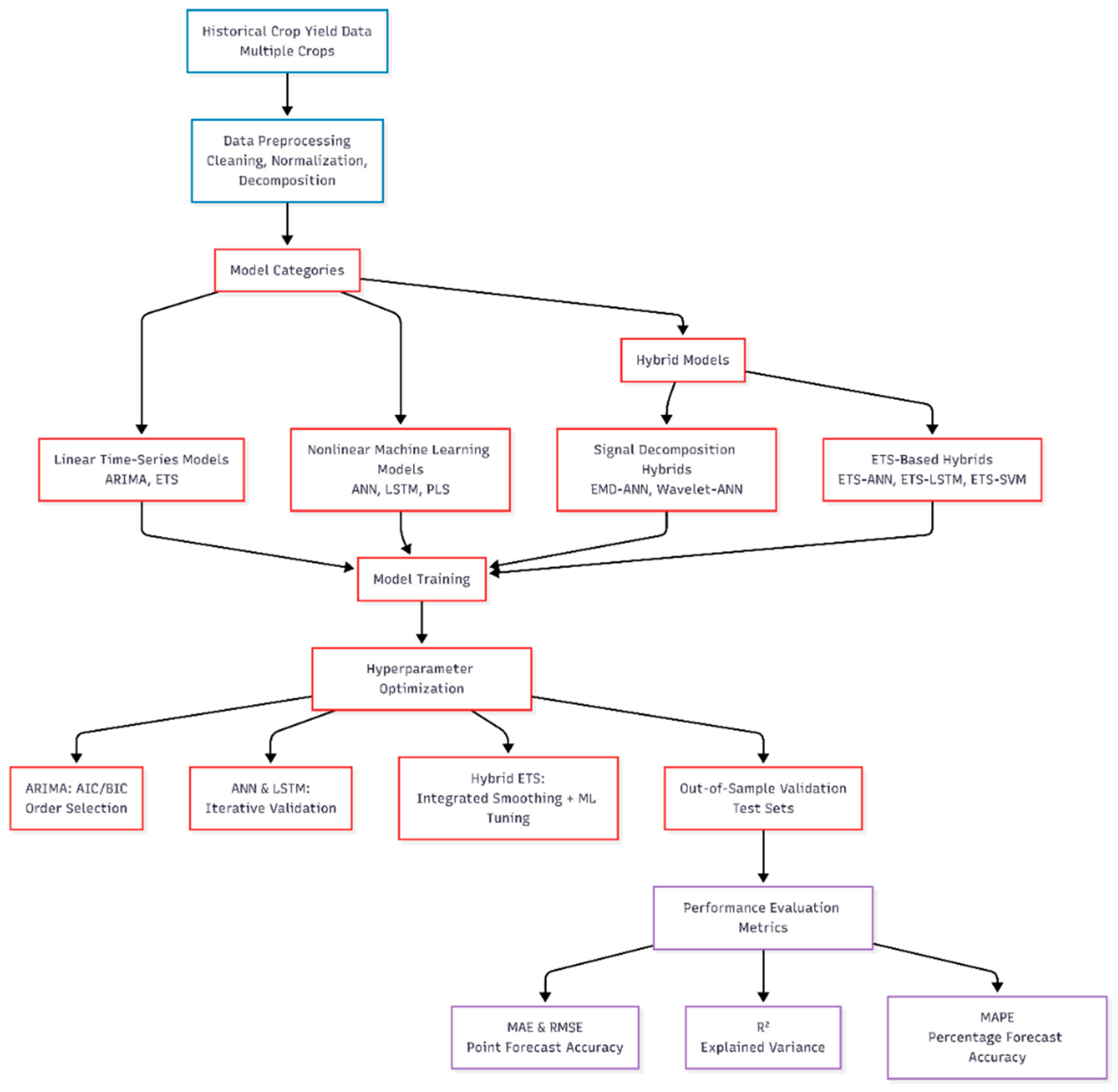

3.3. Proposed Solution

- Combines linear, nonlinear, and deep temporal representations.

- Captures trend, volatility, and nonlinear dependencies.

- Provides robust long-term yield forecasts.

3.4. Model Selection

3.5. Performance Evaluation Metrics

4. Results and Analysis

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ANN | Artificial Neural Network |

| ARIMA | Autoregressive Integrated Moving Average |

| EMD-ANN | Empirical Mode Decomposition–Artificial Neural Network |

| ETS-ANN | Error–Trend–Seasonality–Artificial Neural Network |

| ETS-LSTM | Error–Trend–Seasonality–Long Short-Term Memory |

| ETS-SVM | Error–Trend–Seasonality–Support Vector Machine |

| LSTM | Long Short-Term Memory |

| PLS | Partial Least Squares |

| Wavelet-ANN | Wavelet Transform–Artificial Neural Network |

References

- Norton, G. W.. Jeffery. Alwang, and W. A.. Masters, Economics of agricultural development: world food systems and resource use; Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Pawlak, K.; Kołodziejczak, M. The role of agriculture in ensuring food security in developing countries: Considerations in the context of the problem of sustainable food production. Sustainability (Switzerland) 2020, vol. 12(no. 13). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahar, N. H. A. Meeting the food security challenge for nine billion people in 2050: What impact on forests? Global Environmental Change 2020, vol. 62, 102056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alebele, Y. Estimation of crop yield from combined optical and SAR imagery using Gaussian kernel regression. IEEE J Sel Top Appl Earth Obs Remote Sens 2021, vol. 14, 10520–10534. [Google Scholar]

- Shafi, U. Tackling food insecurity using remote sensing and machine learning-based crop yield prediction. IEEE Access 2023, vol. 11, 108640–108657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erenstein; Jaleta, M.; Sonder, K.; Mottaleb, K.; Prasanna, B. M. Global maize production, consumption and trade: trends and R&D implications; Springer Science and Business Media B.V, 01 Oct 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Ma, S.; Zhang, H.; Aakur, S. Enhancing corn yield prediction: Optimizing data quality or model complexity? Smart Agricultural Technology 2024, vol. 9, 100671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Di, L.; Sun, Z.; Shen, Y.; Lai, Z. County-level soybean yield prediction using deep CNN-LSTM model. Sensors 2019, vol. 19(no. 20), 4363. [Google Scholar]

- Bali, N.; Singla, A. Emerging Trends in Machine Learning to Predict Crop Yield and Study Its Influential Factors: A Survey. Archives of Computational Methods in Engineering 2022, vol. 29(no. 1), 95–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, B. Varun; Rao, P. V. Gopi Krishna. An effective hybrid attention model for crop yield prediction using IoT-based three-phase prediction with an improved sailfish optimizer. Expert Syst Appl 2024, vol. 255, 124740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yewle, A. D.; Mirzayeva, L.; Karakuş, O. Multi-modal data fusion and deep ensemble learning for accurate crop yield prediction. Remote Sens Appl 2025, vol. 38, 101613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Ayed, R.; Hanana, M. Artificial Intelligence to Improve the Food and Agriculture Sector. In Hindawi Limited; 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashwitha, A.; Latha, C. A. Crop Recommendation and Yield Estimation Using Machine Learning. Journal of Mobile Multimedia 2022, vol. 18(no. 3), 861–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badshah; Yousef Alkazemi, B.; Din, F.; Zamli, K. Z.; Haris, M. Crop Classification and Yield Prediction Using Robust Machine Learning Models for Agricultural Sustainability. IEEE Access 2024, vol. 12, 162799–162813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiabul Hoque, M. D. Incorporating Meteorological Data and Pesticide Information to Forecast Crop Yields Using Machine Learning. IEEE Access 2024, vol. 12, 47768–47786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Screpnik; Zamudio, E.; Gimenez, L. Artificial Intelligence in Agriculture: A Systematic Review of Crop Yield Prediction and Optimization. IEEE Access, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, P.; Dadheech, P.; Aneja, N.; Aneja, S. Predicting Agriculture Yields Based on Machine Learning Using Regression and Deep Learning. IEEE Access 2023, vol. 11, 111255–111264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Kumar, M. Developing an XAI-Based Crop Recommendation Framework Using Soil Nutrient Profiles and Historical Crop Yields. In IEEE Transactions on Consumer Electronics; 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shams, M. Y.; Gamel, S. A.; Talaat, F. M. Enhancing crop recommendation systems with explainable artificial intelligence: a study on agricultural decision-making. Neural Comput Appl 2024, vol. 36(no. 11), 5695–5714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elavarasan; Durairaj Vincent, P. M. Crop Yield Prediction Using Deep Reinforcement Learning Model for Sustainable Agrarian Applications. IEEE Access 2020, vol. 8, 86886–86901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waqar, M.; Kim, Y. W.; Byun, Y. C. A Stacking Ensemble Framework Leveraging Synthetic Data for Accurate and Staple Crop Yield Forecasting. In IEEE Access; 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J. Crop Yield Estimation in the Canadian Prairies Using Terra/MODIS-Derived Crop Metrics. IEEE J Sel Top Appl Earth Obs Remote Sens 2020, vol. 13, 2685–2697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dey, T.; Bera, S.; Mukherjee, A.; De, D.; Buyya, R. FLyer: Federated Learning-Based Crop Yield Prediction for Agriculture 5.0. IEEE Transactions on Artificial Intelligence vol. 6(no. 7), 1943–1952, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Osibo, B. K. Enhancing Crop Yield Estimation Through Iterative Querying and Bayesian-Optimized Gated Networks. IEEE Geoscience and Remote Sensing Letters 2025, vol. 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, M. S.; Singh, A.; Reddy, N. V. S.; Acharya, D. U. Crop prediction using machine learning. In Journal of Physics: Conference Series; IOP Publishing Ltd, Jan 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crecco, L.; Bajocco, S.; Bregaglio, S. CrYP: An open-source Google earth engine tool for spatially explicit crop yield predictions. Comput Electron Agric 2025, vol. 237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ransom, J. Statistical and machine learning methods evaluated for incorporating soil and weather into corn nitrogen recommendations. Comput Electron Agric 2019, vol. 164, 104872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panda, S. S.; Ames, D. P.; Panigrahi, S. Application of vegetation indices for agricultural crop yield prediction using neural network techniques. Remote Sens (Basel) 2010, vol. 2(no. 3), 673–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lykhovyd, P. Sweet corn yield simulation using normalized difference vegetation index and leaf area index. Journal of Ecological Engineering 2020, vol. 21(no. 3). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahhosseini, M.; Hu, G.; Archontoulis, S. V. Forecasting corn yield with machine learning ensembles. Front Plant Sci 2020, vol. 11, 1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crane-Droesch, A. Machine learning methods for crop yield prediction and climate change impact assessment in agriculture. Environmental Research Letters 2018, vol. 13(no. 11), 114003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kross. Using artificial neural networks and remotely sensed data to evaluate the relative importance of variables for prediction of within-field corn and soybean yields. Remote Sens (Basel) 2020, vol. 12(no. 14), 2230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maimaitijiang, M.; Sagan, V.; Sidike, P.; Hartling, S.; Esposito, F.; Fritschi, F. B. Soybean yield prediction from UAV using multimodal data fusion and deep learning. Remote Sens Environ 2020, vol. 237, 111599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terliksiz, A. S.; Alt\`ylar, D. T. Use of deep neural networks for crop yield prediction: A case study of soybean yield in lauderdale county, alabama, usa. 2019 8th international conference on Agro-Geoinformatics (Agro-Geoinformatics), 2019; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Schwalbert, R. A.; Amado, T.; Corassa, G.; Pott, L. P.; Prasad, P. V. V.; Ciampitti, I. A. Satellite-based soybean yield forecast: Integrating machine learning and weather data for improving crop yield prediction in southern Brazil. Agric For Meteorol 2020, vol. 284, 107886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MirhoseiniNejad, S. M.; Abbasi-Moghadam, D.; Sharifi, A. ConvLSTM-ViT: A deep neural network for crop yield prediction using Earth observations and remotely sensed data. IEEE J Sel Top Appl Earth Obs Remote Sens, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Debalke, B.; Abebe, J. T. Maize yield forecast using GIS and remote sensing in Kaffa Zone, South West Ethiopia. Environmental Systems Research 2022, vol. 11(no. 1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, J. Downscaling Administrative-Level Crop Yield Statistics to 1 km Grids Using Multisource Remote Sensing Data and Ensemble Machine Learning. IEEE J Sel Top Appl Earth Obs Remote Sens 2024, vol. 17, 14437–14453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitra, A. Cotton Yield Prediction: A Machine Learning Approach With Field and Synthetic Data. IEEE Access 2024, vol. 12, 101273–101288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haider, S. T. An Ensemble Machine Learning Framework for Cotton Crop Yield Prediction Using Weather Parameters: A Case Study of Pakistan. IEEE Access 2024, vol. 12, 124045–124061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y. J.; Lai, M. H.; Wang, C. H.; Huang, Y. S.; Lin, J. Target-Aware Yield Prediction (TAYP) Model Used to Improve Agriculture Crop Productivity. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2024, vol. 62, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashfaq, M.; Khan, I.; Alzahrani, A.; Tariq, M. U.; Khan, H.; Ghani, A. Accurate wheat yield prediction using machine learning and climate-NDVI data fusion. IEEE Access 2024, vol. 12, 40947–40961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, S. Crop Yield Prediction Using Multimodal Meta-Transformer and Temporal Graph Neural Networks. IEEE Transactions on AgriFood Electronics 2024, vol. 2(no. 2), 545–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, M.; Bari, B. S.; Yusup, Y.; Kamaruddin, M. A.; Khan, N. A Comprehensive Review of Crop Yield Prediction Using Machine Learning Approaches with Special Emphasis on Palm Oil Yield Prediction; Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramzan, Z.; Asif, H. M. S.; Yousuf, I.; Shahbaz, M. A Multimodal Data Fusion and Deep Neural Networks Based Technique for Tea Yield Estimation in Pakistan Using Satellite Imagery. IEEE Access 2023, vol. 11, 42578–42594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudhamathi, T.; Perumal, K. Ensemble regression based Extra Tree Regressor for hybrid crop yield prediction system. Measurement: Sensors 2024, vol. 35, 101277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmud, T. An Approach for Crop Prediction in Agriculture: Integrating Genetic Algorithms and Machine Learning. IEEE Access 2024, vol. 12, 173583–173598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleem, R. M. Internet of Things Based Weekly Crop Pest Prediction by Using Deep Neural Network. IEEE Access 2023, vol. 11, 85900–85913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dangi, S.; Mullapudi, S. K.; Raghaw, C. S.; Dar, S. S.; Rehman, M. Z. U.; Kumar, N. A multi-temporal multi-spectral attention-augmented deep convolution neural network with contrastive learning for crop yield prediction. Comput Electron Agric 2025, vol. 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Wang, D.; Guo, H.; Han, C.; Zeng, W. MT-CYP-Net: Multi-task network for pixel-level crop yield prediction under very few samples. International Journal of Applied Earth Observation and Geoinformation 2025, vol. 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vemunuri, J.; Murthy, D. G. Precision agriculture through biochemical urease-aware crop yield prediction using enhanced fuzzy logic and deep learning. Smart Agricultural Technology 2025, vol. 12, 101340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mena. Adaptive fusion of multi-modal remote sensing data for optimal sub-field crop yield prediction. Remote Sens Environ 2025, vol. 318, 114547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, S.; Ko, J.; Ban, J. oh; Shin, T.; Yeom, J. min. Deep learning-enhanced remote sensing-integrated crop modeling for rice yield prediction. Ecol Inform 2024, vol. 84, 102886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramaniam, L. K.; Marimuthu, R. Crop yield prediction using effective deep learning and dimensionality reduction approaches for Indian regional crops. e-Prime - Advances in Electrical Engineering, Electronics and Energy 2024, vol. 8, 100611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirhan. A deep learning framework for prediction of crop yield in Australia under the impact of climate change. Information Processing in Agriculture 2025, vol. 12(no. 1), 125–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajakumaran, M.; Arulselvan, G.; Subashree, S.; Sindhuja, R. Crop yield prediction using multi-attribute weighted tree-based support vector machine. Measurement: Sensors 2024, vol. 31, 101002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M. Seasonal prediction of crop yields in Ethiopia using an analog approach. Agric For Meteorol 2023, vol. 331, 109347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iniyan, S.; Varma, V. Akhil; Naidu, C. Teja. Crop yield prediction using machine learning techniques. Advances in Engineering Software 2023, vol. 175, 103326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maya Gopal, P. S.; Bhargavi, R. A novel approach for efficient crop yield prediction. Comput Electron Agric 2019, vol. 165, 104968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cedric, L. S. Crops yield prediction based on machine learning models: Case of West African countries. Smart Agricultural Technology 2022, vol. 2, 100049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gawade, S. D.; Bhansali, A.; Chopade, S.; Kulkarni, U. Optimizing crop yield prediction with R2U-Net-AgriFocus: A deep learning architecture with leveraging satellite imagery and agro-environmental data. Expert Syst Appl 2026, vol. 296, 128942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sr. No. | References | Research Subject/Crop | ML/DL techniques | Accuracy | Limitation |

| 1 | [13] | Karnataka State crop | Decision tree, k-NN, XGBoost, SVM, DBSCAN, agglomerative, Random forest, logistic regression, naïve bayes, gradient boosting-means, linear regression, stochastic gradient descent | 99.93% (RF) | Limited to the Karnataka State crop in India, not globally |

| 2 | [46] | Cassava, Maize, Plantains and others, Potatoes, Rice, paddy, Sorghum, Soybeans, Sweet, potatoes, Wheat,Yams |

KPCA, LESSO, ER-ETR | 95% | Model overfitting due to small dataset |

| 3 | [14] | Mango, papaya, apple, banana, orange, pomegranate, grapes, watermelon, muskmelon, coconut, mung beans, mung bean, chickpea, kidney beans, pigeon peas, black gram, cotton, coffee, jute, and moth beans | DT, RF, SVM, KNN, GNB, ETC, LR | 99.7% (RF) | Limited to regression models only |

| 4 | [43] | Sugarbeet crop | Temporal graph neural network, multimodal meta transfer | 97% | Only limited to the Sugarbeet crop |

| 5 | [47] | Pigeon peas, Chickpea, Coffee, Pomegranate, Kidney beans, Apple, Muskmelon, Rice, Black gram, Cotton, Maize, Coconut, Grapes, Moth beans, Banana, Jute, Watermelon, Mung beans, Papaya, Lentil, Orange, and Mango. | GA and ML, accuracy = 99.3% | 99.3% | Focus on dataset of ICAR |

| 6 | [48] | Crop pests | IoT, DL, accuracy = 94% | 94% | Focus on sensors generated dataset |

| 7 | [49] | Crop | MTMS-YieldNet Sentinel-2 dataset | MAPE = 0.331 | Focus on Sentinel-1, Sentinel-2, and e Landsat-8 datasets only |

| 8 | [50] | soybean, maize, rice | MT-CYP-Net | RMSE = 0.1472, MAE = 0.0706 | Focus on satellite Sentinel-2 dataset for soybean, maize, rice |

| 9 | [51] | Crops (apple, banana, blackgram, chickpea, coconut, coffee, cotton, grapes, jute, kidney beans, lentil, maize, mango, moth beans, mung beans, muskmelon, orange, papaya, pigeonpeas, pomegranate, rice, and watermelon) |

EL-Fuzzy, TL-SFGRU |

MSE = 0.1087, RMSE = 0.3296, and MAE = 0.1057 | Limited to the Indian crop only |

| 10 | [52] | soybean, wheat, rapeseed | Multi-modal Gated Fusion (MMGF) | R2 = 0.80 |

Depend on Sentinel-2 satellites, weather data Limited to Argentina, Uruguay, and Germany area crop |

| 11 | [53] | Rice crop | LSTM, bidirectional LSTM, FFNN, GRU | RMSE of 0.101, PBIAS of 0.74, and NSE of 0.9960 | Focus only on the rice crop |

| 12 | [17] | Indian Crop | Random forest, XGBoost, decision tree (regression), CNN, LSTM (deep learning) | 98.96% (RF) | Limited to the Indian crop only |

| 13 | [54] | South Indian Crop of both season | SEKPCA, WTDCNN | 98.96% | Limited to the South Indian crop only |

| 14 | [55] | oats, corn, rice, and wheat | DNN | MAE and RMSE (19-40%) | Focus on Australia crops |

| 15 | [56] | Indian Crop | Z-score, GA, PCA, MAWT-SVM, | Not specified | Overhead due to GA |

| 16 | [57] | Ethiopia Seasonal Crop | CREST, DSSAT | R2 = 0.60 (Dangishta sites) | Limited to Maize crop of Ethiopia |

| 17 | [58] | Not Specified | LASSO, GB, LSTM, Ridge, MLR, DTR, PLS, Elastic Net | 86.3% (LSTM) | Unclear generalization of dataset |

| 18 | [59] | Tamilnadu State crop | SVR, RF, ANN, MLR, KNN, MLR-ANN | 0.99 (MLR-ANN | Limited to the Tamilnadu State crop paddy (rice) in India, not globally |

| 19 | [60] | West African | DT, Logistic regression, KNN | R2 = 95.3% (DT) | Focus on only country level prediction |

| 20 | [61] | General Crop | R2U-Net-AgriFocus, CNN, VGG16, HHPA | MSE = 0.002, MAE = 0.001, NMSE = 0, RMSE = 0.039, MAPE = 0 | Model computational complexity is very high |

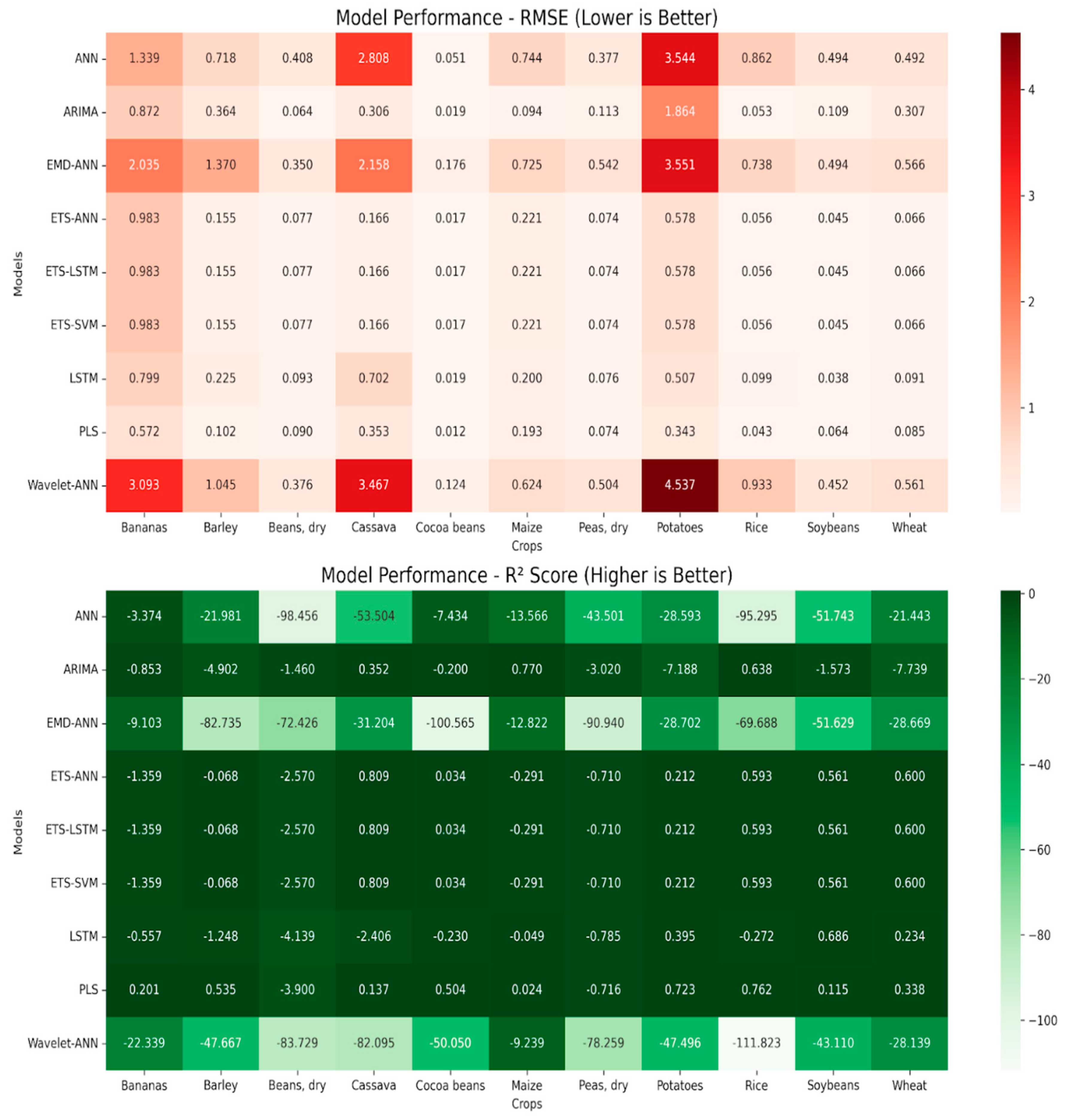

| Model | MAE_mean | MAE_std | RMSE_mean | RMSE_std | R2_mean | R2_std | MAPE_mean | MAPE_std |

| ANN | 0.9506 | 0.9765 | 1.0761 | 1.1006 | -39.8991 | 32.7213 | 16.8396 | 6.2405 |

| ARIMA | 0.3437 | 0.5129 | 0.3786 | 0.5495 | -2.2886 | 3.0593 | 4.9255 | 3.123 |

| EMD-ANN | 1.0302 | 0.9323 | 1.155 | 1.0341 | -52.5893 | 32.3121 | 20.8727 | 9.2781 |

| ETS-ANN | 0.1988 | 0.2707 | 0.2218 | 0.2971 | -0.199 | 1.0167 | 3.0636 | 1.3533 |

| ETS-LSTM | 0.1988 | 0.2707 | 0.2218 | 0.2971 | -0.199 | 1.0167 | 3.0636 | 1.3533 |

| ETS-SVM | 0.1988 | 0.2707 | 0.2218 | 0.2971 | -0.199 | 1.0167 | 3.0636 | 1.3533 |

| LSTM | 0.2226 | 0.2353 | 0.2588 | 0.2784 | -0.7609 | 1.4087 | 3.6877 | 1.6926 |

| PLS | 0.142 | 0.1338 | 0.1756 | 0.1747 | -0.1161 | 1.3192 | 2.7283 | 1.3218 |

| Wavelet-ANN | 1.294 | 1.3847 | 1.4287 | 1.5167 | -54.9043 | 30.8017 | 21.1054 | 5.7466 |

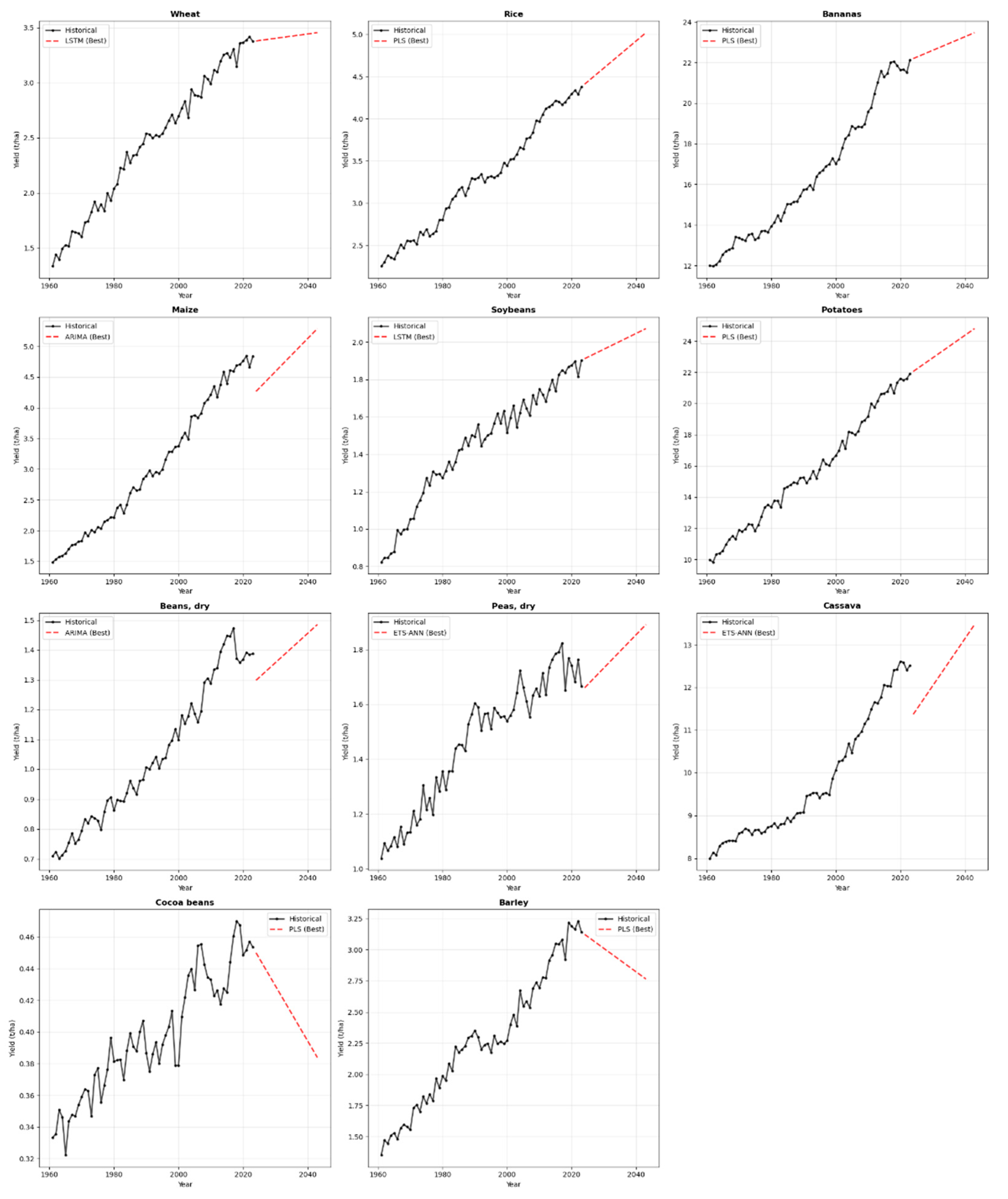

| Crop | Model | MAE | RMSE | R² | MAPE |

| Bananas | PLS | 0.438 | 0.572 | 0.201 | 2.03 |

| Rice | PLS | 0.031 | 0.043 | 0.762 | 0.74 |

| Wheat | ETS-ANN | 0.050 | 0.066 | 0.600 | 1.53 |

| Soybeans | LSTM | 0.034 | 0.038 | 0.686 | 1.90 |

| Maize | ARIMA | 0.073 | 0.094 | 0.770 | 1.61 |

| Cassava | ETS-ANN | 0.147 | 0.166 | 0.809 | 1.20 |

| Crop Name | Rank 1 Model | Rank 2 Model | Rank 3 Model | Rank 4 Model | Rank 5 Model |

| Wheat | ETS-ANN | ETS-LSTM | ETS-SVM | PLS | LSTM |

| Rice | PLS | ARIMA | ETS-ANN | ETS-LSTM | ETS-SVM |

| Bananas | PLS | LSTM | ARIMA | ETS-ANN | ETS-LSTM |

| Maize | ARIMA | PLS | LSTM | ETS-ANN | ETS-LSTM |

| Soybeans | LSTM | ETS-ANN | ETS-LSTM | ETS-SVM | PLS |

| Potatoes | PLS | LSTM | ETS-ANN | ETS-LSTM | ETS-SVM |

| Beans (Dry) | ARIMA | ETS-ANN | ETS-LSTM | ETS-SVM | PLS |

| Peas (Dry) | ETS-ANN | ETS-LSTM | ETS-SVM | PLS | LSTM |

| Cassava | ETS-ANN | ETS-LSTM | ETS-SVM | ARIMA | PLS |

| Cocoa Beans | PLS | ETS-ANN | ETS-LSTM | ETS-SVM | ARIMA |

| Barley | PLS | ETS-ANN | ETS-LSTM | ETS-SVM | LSTM |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.