1. Introduction

Chemsex represents a specific form of sexualized substance use (SSU) and refers to the intentional consumption of specific psychoactive substances before or during sexual activity with the aim of enhancing, sustaining, or prolonging sexual experiences [

1] . While chemsex is not exclusive to any single demographic group, it is particularly prevalent among men who have sex with men (MSM) [

1], especially in contexts such as sex parties (Party-n-Play, PnP) and group sexual encounters [

2].

Several terms have emerged to describe similar forms of perisexual drug use, including “wired sex” and “sex on chems.” Some languages even offer unique descriptors for this phenomenon; for example, the Filipino term pampalibog refers specifically to substances used to increase sexual arousal [

3].

Although chemsex is often initiated with the intention of enhancing sexual pleasure, its consequences extend far beyond the sexual context. The practice is associated with a wide range of harms, including psychiatric and somatic complications linked to substance use, an increased risk of sexually transmitted infections (STIs), heightened addiction and overdose potential, and substantial deterioration in mental health [

4].

The aim of this review is to provide a comprehensive overview of chemsex, with particular emphasis on its role in the transmission of sexually transmitted infections (STIs). In addition, the review examines the associated psychiatric and somatic risks, explores the underlying motivations that sustain chemsex practices, and identifies potential avenues for prevention and intervention.

2. Methods

A narrative review was conducted using PubMed through December 11, 2025. Search terms combined chemsex-related terminology, substance names, and health outcomes. Recent English-language publications (2020-2025) were prioritized. Evidence was synthesized thematically across epidemiology, health complications, motivations, and interventions.

3. Epidemiology and Risk Factors

Estimating the global prevalence of chemsex remains challenging due to substantial heterogeneity in study designs, recruitment strategies, and the impact of national drug policies. A further limitation is that most research focuses on men who have sex with men (MSM), restricting the generalizability of findings to the wider population. As a result, recent systematic reviews report a broad range of global prevalence estimates, spanning from 3% to 52.5%. Even within MSM populations, prevalence rates vary considerably across studies [

5,

6]. For instance, a pan-European survey assessing chemsex in the previous four weeks demonstrated substantial inter-city differences: Brighton and Manchester reported the highest prevalences (16.3% and 15.5%, respectively), whereas Sofia reported only 0.4% [

7].

Evidence from non-MSM samples, although limited, highlights similarly diverse patterns. A study among women in Kazakhstan found a chemsex prevalence of 15.61%, notably lower than in the Kazakh general population (25.78%) [

8]. Research from Spain reported that 12% of heterosexual men and women engaged in SSU, with no significant sex differences [

9]. In Brazil, transgender women had 2.44-times higher odds of SSU engagement compared with MSM, independent of pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) use [

10].

A global survey (n = 22,289) further revealed that heterosexual men engage in sex less frequently than homosexual and bisexual men (p < .001), and heterosexual women less frequently than bisexual women (p < .004). Despite these differences, drug use with the intention of enhancing sexual experiences was ≥20% across all groups [

11].

Findings from a recent systematic review indicate that both SSU and chemsex represent notable behavioral phenomena, with pooled prevalences of 19.92% in the general population and 15.61% among women. SSU appears to be the more widespread pattern: in the general population, its prevalence (29.40%) substantially exceeds that of chemsex (12.66%). Among women, the disparity is even more pronounced, with SSU reaching 25.78% and chemsex only 3.50%. These results suggest that SSU represents a broader behavioral trend, whereas chemsex constitutes a more specific subset of this spectrum [

8].

Identified risk factors for chemsex also vary by population. Among university students, potential predictors include the use of dating applications and pornography, bisexual orientation, and having a partner who uses chemsex-related substances [

6]. In contrast, risk factors among MSM include younger age, recent STI diagnosis, having more than five sexual partners, decreased condom use, post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) use, and dating app use [

6,

12]. Mobile applications are believed to facilitate encounters where recreational drug use occurs, and meeting partners via apps, regardless of substance use, is associated with increased risks of HIV transmission and condomless anal intercourse [

4].

Clinic-based data reinforce this pattern. In a Spanish STI clinic, 96% of individuals reporting chemsex within the past year were men, the majority identifying as MSM (84%), with very low reporting among bisexual men or men who have sex exclusively with women (6%) [

6]. Chemsex was more frequent among individuals living with HIV (43%), those without a stable partnership (71%), and those engaging in group sex (63%) or reporting ≥12 partners in the past year [

6].

Slamming (or slamsex), the intravenous administration of drugs in sexualized contexts, is another high-risk form of chemsex. Its prevalence varies considerably across countries, with rates of around 10% among MSM in Australia and England. Slamming appears more common among MSM and women who have sex with women (WSW) than among heterosexual individuals [

4].

4. Substances Implied in Chemsex

Commonly used substances in chemsex settings include cocaine, ketamine, mephedrone and other synthetic cathinones, gamma-hydroxybutyrate/gamma-butyrolactone (GHB/GBL), ecstasy/MDMA (3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine), marijuana, and amphetamines/methamphetamines [

1]. Some authors additionally categorize phosphodiesterase 5 (PDE-5) inhibitors—such as sildenafil, tadalafil, and vardenafil, as “chemsex drugs” [

13]. Beyond these, virtually any psychoactive substance, including cannabis and synthetic cannabinoids [

13], may be used to intensify sexual pleasure and can therefore be considered within the broader spectrum of chemsex-related substances.

This review primarily focuses on agents whose principal function in this context is the enhancement of sexual activity.

Although a wide range of substances can be used to enhance sexual activity, and no universally accepted classification exists, they can be broadly grouped according to their primary effects: (1) agents that induce euphoria and intensify sexual pleasure, (2) substances that promote disinhibition, (3) compounds with dissociative properties, (4) drugs with muscle-relaxing and vasodilatory effects, and (5) medications used to treat erectile dysfunction.

The first group includes (synthetic) cathinones, amphetamines/methamphetamines, MDMA, and cocaine [

4]. Cocaine and amphetamine-derivatives, such as “speed,” although still used in sexual contexts, are increasingly being supplanted by designer drugs such as synthetic cathinones [

4].Cathinones, such as mephedrone and 4-methylmethcathinone (4-MMC), are synthetic derivatives inspired by the khat plant and possess amphetamine-like properties. Synthetic cathinones are often sold under labels such as “bath salts not suitable for human consumption” to circumvent legal restrictions. These substances produce effects similar to those of amphetamines and cocaine, including agitation, empathy, euphoria, and enhanced libido and sexual performance. Approximately 30% of users develop addiction to synthetic cathinones [

4].

They are frequently combined with other substances such as GHB/GBL, ketamine, cocaine, and methamphetamine. Cathinones are primarily administered orally or via inhalation, but some forms can be injected or used rectally, a practice colloquially referred to as “booty bumping” [

4].

Amphetamines and methamphetamine (meth) also fall within this category, as they are commonly used in chemsex due to their stimulant properties that enhance sexual activity. These substances act as potent dopamine agonists and likely exert synergistic effects on dopaminergic reward pathways [

3]. Meth use has additionally been associated with increased feelings of love and sociability. Crystal meth is of particular interest because it produces stronger stimulant effects and carries a higher addictive potential compared with cocaine or other amphetamines. Administration routes include oral ingestion, smoking, injection, or intrarectal application (“booty bumping”)[

4]. Among MSM in Asia, methamphetamine is considered the predominant chemsex substance, followed by GHB/GBL and ketamine [

3].

MDMA (ecstasy, “Molly,” or the “love drug”) is another commonly used chemsex substance. It is both empathogenic and entactogenic, promoting disinhibition as well as heightened feelings of intimacy, which may further enhance its effects on dopaminergic reward pathways [

3].

The second group comprises substances with disinhibiting properties. Prominent examples include gamma-hydroxybutyrate (GHB) and its more affordable prodrug, gamma-butyrolactone (GBL), the latter typically available as a colorless, oily liquid for oral use. Both substances are often mixed with beverages prior to consumption. GHB generally appears as a white crystalline powder and can also be administered intravenously. The primary purpose of these agents in sexual contexts is to facilitate penetration by promoting muscle relaxation through central disinhibition [

4,

13].

The third group includes substances with dissociative and euphoric effects, with ketamine being particularly common in chemsex. Ketamine, a phencyclidine (PCP) derivative, acts as a noncompetitive N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor antagonist. At low doses, its euphoric and dissociative effects are highly sought after during sexual activity [

4]. Ketamine can be administered orally or via inhalation [

4].

The fourth group consists of muscle-relaxing vasodilators, primarily alkyl nitrites such as isoamyl nitrite, isopentyl nitrite, isopropyl nitrite, and isobutyl nitrite, commonly marketed as “poppers” [

1,

14]. These substances, usually in liquid form, act as potent vasodilators, relaxing smooth muscles in the throat and anus, thereby facilitating sexual practices such as deep-throating and anal intercourse. Alkyl nitrites may also induce mild euphoria, warmth, and dizziness. They are typically consumed by inhalation and have short-acting effects [

13,

14].

The fifth group consists of non-psychoactive erectile dysfunction agents, including sildenafil, tadalafil, and vardenafil. These drugs are primarily used to facilitate penile erection and enhance sexual performance. Within chemsex contexts, they may also be employed to prolong sexual activity and counteract the negative effects of other psychoactive substances. Administration is typically oral [

4].

5. Mental Health Effects

A systematic review indicated that depression was the most commonly reported mental health outcome associated with chemsex, with 50% of the included studies highlighting depressive symptoms [

15]. This was followed by 33.3% of studies reporting a positive association between chemsex and anxiety, and 25% identifying a link with suicidal ideation. Some studies also associated substance use in chemsex with psychosis [

15]. Depressive symptoms were particularly pronounced among methamphetamine users [

15].

Slamsex was more common among individuals with self-reported psychiatric diagnoses. Participants who engaged in slamsex reported higher rates of depressive symptoms (61.8 percent compared to 28 percent), anxiety (47.1 percent compared to 23.1 percent), and addictive symptoms (38.2 percent compared to 15.4 percent) than those who used substances non-intravenously [

15]. Slamsex was also associated with psychiatric disorders such as psychotic symptoms, agitation, anxiety, or suicide attempts in 50 percent of cases, acute intoxication in 25 percent of cases including three deaths, and dependence or abuse in 17 percent of cases. Slamsex participants also reported poorer mental health and higher antidepressant use over the previous 12 months. The mean mental health score was 51.8 for those who engaged in slamsex and 66.5 for those who never did [

15].

A systematic review reported that the prevalence of psychotic symptoms among chemsex users ranged from 6.7 percent to 37.2 percent. Slamsex, poly-drug use, and methamphetamine smoking were identified as triggers for psychosis, conferring a threefold increased risk [

16]. Additional important risk factors included belonging to a foreign or ethnic minority, living in a large city, stress, anxiety, trauma, loneliness, STIs, hepatitis, and a prior history of psychosis [

16].

Besides depression and anxiety, somatization were also significantly more common in chemsex-engaging MSM in Germany, when compared to overall population. In addition, the same group reported a higher number of non-consensual sexual intercourse, whose effects on mental health requires further investigation [

17]. Most commonly reported psychiatric symptoms in the German setting were impaired social functioning (33.6%), psychosis (13.2%) and physical aggression toward others (2.9%) [

17].

An electroencephalography (EEG) study demonstrated that chemsex users exhibit electrophysiological changes in cortical areas responsible for inhibitory control and executive functions, which may explain the increased hypersexuality and risk-taking behavior observed in this group [

18].

Substances used in chemsex can mimic or trigger various psychiatric syndromes and may worsen pre-existing symptoms. The type and severity of these effects depend on the specific substance, as well as the dose and frequency of use.

Synthetic cathinones can cause confusion, agitation, combative behavior, visual hallucinations, and persecutory ideas, thereby mimicking psychotic disorders, avoidant personality traits, and delirium [

4]. Suicidal ideation and suicide attempts have also been reported in association with their use [

4]. Signs of sympathetic autonomic activation, such as hypertension, chest pain, and mydriasis, may support the diagnosis but can be easily mistaken for panic attacks or the effects of cocaine and other stimulants. The presence of myoclonus, observed in only 19 percent of cases, may serve as a key clue for cathinone use. Depending on the severity of psychiatric symptoms, hospitalization and symptomatic management with benzodiazepines may be necessary [

4].

Other stimulant substances, such as cocaine and amphetamines, increase the release of dopamine, noradrenaline, adrenaline, and serotonin. These effects may exacerbate underlying psychiatric conditions, such as bipolar disorder, potentially triggering mania or hypomania in vulnerable individuals [

4]. They may also precipitate a first psychotic episode in susceptible individuals or worsen existing primary psychotic disorders, such as schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder. Crystal meth is of particular concern due to its especially strong stimulant effects [

4]. Anxiety disorders and depression are also common among amphetamine or methamphetamine users. Severe psychopathological symptoms should be managed pharmacologically with antipsychotics, particularly aripiprazole, and benzodiazepines. N-acetylcysteine may be considered as a treatment option for methamphetamine dependence [

4].

Acute MDMA use produces enhanced mood and increase sociability, however chronic or heavy MDMA use may result in sleep disturbances, depression, anxiety, hostility and impulsivity. Furthermore, MDMA users perform worse on learning and memory tests, even after months of abstinence [

18,

19].

GHB and GBL, often used for their disinhibiting effects to facilitate sexual activity, can cause repeated comas, potentially impairing cognitive functions such as memory and emotion regulation. These effects may occasionally mimic certain forms of dementia in the differential diagnosis [

4]. Dependence on GHB or GBL can be diagnosed using standard substance use disorder criteria, and potential options for withdrawal symptoms include baclofen and diazepam [

4]. Ketamine can cause dissociation even in lower-doses used for depression treatment, however usually in the context of chemsex higher doses are used [

20].

„Poppers“ can cause headache, light-headedness, acute euphoria or excitement and disorders of perception such as a slowed time perception and visual distortions [

21].

Finally, PDE-5 inhibitor sildenafil has been reported to cause psychosis in a case report [

22].

6. Chemsex and STI Risk

Chemsex has been linked to several negative health outcomes, particularly a substantially increased risk of acquiring sexually transmitted infections (STIs). It often facilitates high-risk sexual behaviors, including condomless intercourse, engagement with multiple partners, and prolonged sexual encounters, which together amplify opportunities for STI transmission. These behaviors, combined with reduced inhibition and altered judgment under the influence of substances, make chemsex a significant driver of STI burden in affected populations [

5]. A Norwegian study reported that nearly 50 percent of MSM from a walk-in STI clinic engaged in unprotected sexual intercourse, further increasing STI risk [

12].

A systematic review highlighted a striking difference in HIV incidence between chemsex-engaged and non-chemsex MSM in low- and middle-income countries. Among chemsex users, HIV incidence ranged from 13.1 to 16.2 per 100 person-years, whereas among MSM not engaging in chemsex, incidence was substantially lower at 5.4 to 7.7 per 100 person-years. This disparity underscores chemsex as a significant driver of HIV acquisition risk in resource-limited settings and reinforces the need for targeted prevention strategies [

5].

MSM engaging in chemsex are more likely to acquire HIV. HIV-positive MSM are also more likely to participate in chemsex, and chemsex itself is a known risk factor for condomless anal intercourse compared with HIV-negative MSM. This combination of higher chemsex prevalence and increased condomless sex may further amplify onward HIV transmission within this population [

1].

There are concerns that PrEP could contribute to increased STI incidence in the context of chemsex or other substance use. While PrEP effectively prevents HIV, it may coincide with reduced condom use and engagement in higher-frequency sexual networks, behaviors often amplified during chemsex. Recent data from Spain showed a statistically significant association between PrEP use and certain STIs, including higher rates of gonorrhoea (p < 0.001), chlamydia (p < 0.001), genital herpes (p = 0.020), and syphilis. Several studies also indicate that PrEP users are more likely to engage in chemsex [

23,

24].

A Dutch study further supports the link between chemsex-related substance use and elevated STI risk among MSM. Use of ecstasy/MDMA, cocaine, and GHB/GBL was significantly associated with STI diagnoses. The risk increased with the number of substances used: participants using three or more chemsex drugs had markedly higher STI positivity over the preceding six months (44%) compared with those using one to two drugs (21%) or none (12%), demonstrating a clear dose–response relationship [

25].

The same Dutch study also reported high-risk sexual and drug-related practices among chemsex participants. Rates of condomless sex were high—64.4% reported condomless receptive anal intercourse, 59.8% condomless insertive anal intercourse, and 35.6% condomless receptive anal sex with toys. Prolonged sexual activity was common, with 39.1% reporting sessions lasting ≥12 hours, and 20.7% engaging in fisting. Group sex occurred in 36.8% of sessions, and 21.8% involved casual partners whose identities were unknown. Although no participants shared needles, 4.6% shared syringes, 5.7% engaged in slamming, 12.6% practiced booty bumping, and 37.9% shared snorting tubes. Collectively, these behaviors highlight the multifaceted risk environment surrounding chemsex and its strong association with STI transmission [

25].

Data from the UK arm of the 2017–2018 European MSM Internet Survey (n = 9,375) show clear differences in chemsex engagement across HIV-status groups. Among HIV-positive MSM, 25% reported participating in multipartner chemsex, while 28% of MSM using PrEP engaged in multipartner chemsex. In contrast, only 5% of HIV-negative MSM not on PrEP reported multipartner chemsex. These findings indicate that chemsex, particularly in multipartner settings, is concentrated among populations with diagnosed HIV or using biomedical prevention strategies, highlighting targets for sexual-health interventions [

26].

Participation in multipartner chemsex was consistently associated with higher odds of bacterial STI diagnoses across all MSM subgroups. Among HIV-diagnosed MSM, chemsex was linked to increased odds of recent syphilis (aOR 2.6), gonorrhoea (aOR 3.9), and chlamydia (aOR 2.9). PrEP users showed a similar but slightly lower risk elevation, and MSM not living with HIV and not using PrEP still faced substantially higher risk [

26]. In contrast, dyadic chemsex did not show the same risk pattern. Among HIV-positive MSM, dyadic chemsex was not associated with increased odds of bacterial STIs, while specific STI elevations were observed in other subgroups. These findings suggest that heightened STI risk linked to chemsex is largely driven by multipartner contexts, whereas dyadic chemsex confers more limited, subgroup-specific risks [

26].

However, dyadic chemsex did not show the same risk pattern as multipartner chemsex. Among HIV-positive MSM, dyadic chemsex was not associated with increased odds of bacterial STIs. In contrast, specific STI elevations were observed in other subgroups: PrEP users engaging in dyadic chemsex had higher odds of recent gonorrhoea (aOR 2.4, 95% CI 1.2–4.7), while HIV-negative, non-PrEP MSM showed increased odds of recent syphilis (aOR 2.8, 95% CI 1.4–5.6). Overall, these findings suggest that the heightened STI risk linked to chemsex is largely driven by multipartner contexts, whereas dyadic chemsex confers more limited and subgroup-specific risks [

26].

Individuals engaging in slamsex constitute a high-risk subgroup for bloodborne infections, showing a strong association between HIV and hepatitis C. HIV seroprevalence in this group was four times higher than among those who do not participate in slamsex [

15].

Positively, some studies indicate that chemsex users more frequently utilize prevention strategies such as PrEP, PEP, and hepatitis B vaccination. However, reported need for PrEP and PEP among chemsex participants was 4.5% and 14%, respectively [

2]. Sexual minority men, particularly those using stimulants or chemsex drugs, may face adherence challenges with daily oral PrEP. Adherence appears to improve following recent condomless anal sex, though retention in PrEP care can remain problematic [

27].

Finally, a study reported that 9.3% of MSM exhibited compulsive sexual behavior traits associated with chemsex, which may contribute to an increased risk of STIs [

28].

Table 1.

summarizes the contributors to STI transmission under chemsex.

Table 1.

summarizes the contributors to STI transmission under chemsex.

| Table 1. Contributors to STI Transmission under Chemsex |

| Increased rate of unprotected sexual intercourse |

| Increased rate of sexual intercourse with HIV-positive individuals |

| Negligence of other protective measures due to PrEP use |

| Simultaneous chemsex with more than 2 persons |

| Use of ecstasy/MDMA, GHB/GBL and cocaine as chemsex substances |

| Intravenous use of chemsex substances (slamming, slamsex) |

|

STI: sexually transmitted infection, PrEP: pre-exposure prophylaxis, HIV: human immunodeficiency virus, MDMA: 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine, GHB: gamma-hydroxybutyrate, GBL: gamma-butyrolactone |

7. Non-STI Somatic Complications

Non-STI somatic complications associated with chemsex substances are highly variable and depend on the specific drug used.

Methamphetamines and amphetamines are linked to increased cardiovascular risk, including cardiomyopathy, arrhythmias, acute and chronic coronary syndromes, pulmonary hypertension, and systemic hypertension [

4,

29]. Dental and periodontal diseases are also common among users. In individuals practicing slamsex (intravenous administration of amphetamines), soft-tissue and vascular injuries, as well as overdoses, may occur [

29]. Given that methamphetamines are not the only substances used during chemsex, and considering the heightened cardiovascular risk in this population, further research is warranted [

30].

MDMA has a similar cardiovascular risk to methamphetamines and amphetamines, but it can also cause hyponatremia, which can eventually lead to seizures and multiple organ failure [

31]. If combined with other serotonergic agents, it may result in serotonin syndrome [

32].

Synthetic cathinones can induce a severe delirium-like syndrome with serious somatic consequences, including skeletal muscle breakdown and dehydration, which may lead to rhabdomyolysis and renal dysfunction, often accompanied by severe hyperthermia. Cases of multiorgan failure and death have also been reported. Although the exact mechanism of this hyperthermia remains unclear, central dopamine dysregulation has been proposed as a potential contributor [

29].

GHB and GBL can cause extreme sleepiness and hypothermia in cases of overdose, potentially resulting in coma or death [

4].

Ketamine, in contrast, may lead to urological complications, including ulcerative cystitis and, less commonly, hydronephrosis. Typical symptoms of ketamine-induced ulcerative cystitis include urinary frequency, dysuria, urgency, incontinence, and sometimes painful hematuria [

4].

Alkyl nitrites, commonly known as “poppers,” can induce a sudden drop in blood pressure with reflex tachycardia, cardiovascular and respiratory failure, methemoglobinemia, coma, and, in severe cases, death [

33]. A case series of seven patients also reported maculopathy leading to visual impairment [

34].

The most significant side effects of PDE-5 inhibitors such as sildenafil, tadalafil, and vardenafil are headache, facial flushing, nasal congestion, dyspepsia, and dizziness, primarily due to systemic vasodilation [

35].

Table 2 provides an overview to chemsex substances, sought-after effects motivating their use, associated psychiatric and somatic risks.

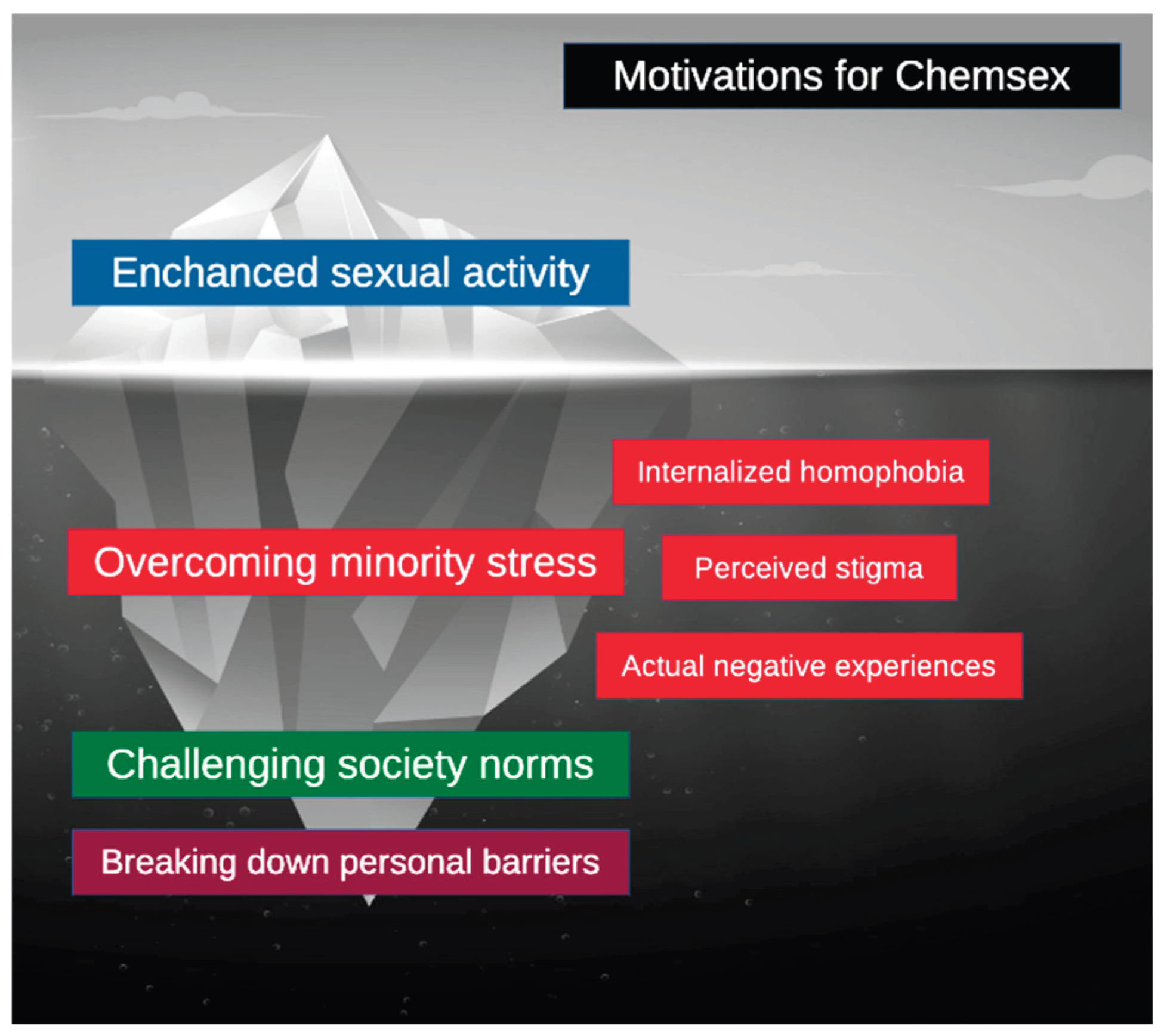

8. Unseen Motivations

Before presenting possible intervention strategies, it is important to understand the motivations driving chemsex beyond increased sexual pleasure. Several theories, including minority stress theory, aim to explain the potential stressors experienced by sexual minorities [

36].

Minority stress theory posits that sexual minorities face specific stressors arising from long-standing sociocultural structures. Three processes contribute to this minority stress: (1) internalized homophobia, involving the adoption of society’s negative attitudes toward one’s sexual orientation; (2) perceived stigma, characterized by anticipated rejection and discrimination; and (3) actual negative experiences [

36,

37]. This stress can lead to a phenomenon called “identity threat,” which may result in emotional dysregulation, substance abuse, and increased vulnerability to STIs [

37,

38].

Although chemsex carries evident risks to physical and mental health, it can also serve as a coping mechanism for minority stress and provide a temporary escape [

38]. It may additionally help restore damaged self-esteem [

5]. For some individuals in sexual minority groups, chemsex may emerge as a “forbidden” yet liberating way to challenge established sociocultural norms [

5]. Others describe it as a means to break down personal barriers related to sexuality and identity, with effects extending far beyond sexual activity [

5]. All of these factors may contribute to continued engagement in chemsex despite its associated risks and should be considered when aiming to achieve long-lasting abstinence [

38].

Importantly, long-standing chemsex behavior can lead to an inability to enjoy sex without substances [

38]. A recent UK-based survey reported that 35% of 123 participants no longer enjoyed sober sex after engaging in chemsex. This phenomenon may ultimately increase the desire for longer sexual sessions and more intense highs, potentially leading to intravenous drug use [

3].

Since the first step toward self-withdrawal from chemsex is help-seeking behavior, some authors advocate for the decriminalization and destigmatization of chemsex. This approach could facilitate access to support, as individuals are more likely to seek help when they face no risk of stigmatization or pathologization [

38].

Figure 1. summarizes motivations driving chemsex.

9. Intervention and Treatment Strategies

Chemsex should be conceptualized as a complex, multifaceted addiction syndrome, involving not only substance dependence but also elements of compulsive sexual behavior and sociocultural/psychological context. As illustrated in published case reports and clinical studies, successful treatment typically requires addressing all of these components simultaneously [

39]. To facilitate abstinence, symptom-oriented pharmacotherapy can be combined with cognitive-behavioral interventions, tailored to the individual’s mental and physical health status and informed by their personal experiences [

40].

Although no standardized pharmacological treatment exists for compulsive sexual behavior, agents such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), naltrexone, and topiramate have been used empirically. Psychotherapeutic strategies focusing on emotion regulation, sexual functioning, group-based interventions, and the treatment of attachment-related issues may further support recovery [

39].

Biobehavioral interventions targeting chemsex behavior alone appear to reduce the frequency of condomless anal intercourse with serodiscordant partners (MD: –1.30, 95% CI: –1.58 to –1.03; p < 0.001), and may nonsignificantly reduce the total number of sexual partners. These effects can meaningfully contribute to reducing HIV transmission, although such interventions do not reduce substance use during sexual activity [

41].

Digital and mobile-health tools represent an emerging adjunct to traditional harm-reduction services. These interventions can deliver drug-related information, warn against dangerous drug combinations, improve PrEP and medication adherence, facilitate rapid access to support networks, and provide emergency guidance in cases of overdose or adverse reactions [

42]. Users with limited social support tend to rely more heavily on non–drug-related features, including PrEP support functions, self-care reminders, and hydration prompts [

40].

When prioritizing treatment modalities, evidence suggests that peer-led harm-reduction interventions, delivered by individuals with lived chemsex experience, are significantly more effective and should be implemented preferentially [

43].

10. Discussion

This review demonstrates that chemsex represents a significant public health challenge with elevated STI risk, psychiatric morbidity, and somatic complications, particularly among MSM.

The wide prevalence variation (3-52.5%) reflects geographic and cultural differences, necessitating locally tailored interventions [

5,

6,

7]. Research predominantly focuses on MSM, limiting understanding of chemsex in other populations [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10].

HIV incidence is 2-3 fold higher among chemsex users (13.1-16.2 vs 5.4-7.7 per 100 person-years) [

5], driven by disinhibition, prolonged sessions, multipartner encounters, and reduced condom use. Multipartner contexts confer greater STI risk than dyadic chemsex [

26]. PrEP-associated increases in bacterial STIs [

23,

24] highlight the need for integrated sexual health services combining biomedical prevention with comprehensive screening and behavioral support.

High rates of depression (50%), anxiety (33%), and psychosis (6.7-37.2%) [

15,

16] reflect bidirectional relationships between mental health and chemsex. Minority stress theory explains how stigma and discrimination drive chemsex as a coping mechanism while generating new psychological harm [

5,

36,

37,

38]. Slamming users show particularly elevated psychiatric morbidity [

15].

Effective interventions integrate pharmacotherapy, behavioral therapy, harm reduction, and peer support [

39,

40,

41,

42,

43]. Peer-led approaches show superior effectiveness [

43], while digital tools enhance engagement [

42]. Destigmatization is essential, stigma at all levels impedes help-seeking [

38].

Limitations include the narrative approach, MSM-focused literature, and predominantly cross-sectional studies. Future research should examine longitudinal trajectories, intervention effectiveness, non-MSM populations, and implementation strategies.

Clinicians should routinely screen for chemsex using non-judgmental communication and provide integrated care. Policy priorities include decriminalization, service integration, peer-led programming, provider training, and digital innovation. Multidisciplinary, destigmatized approaches are essential to reduce chemsex-associated health burdens.

11. Conclusion

Chemsex represents a complex behavioral pattern involving many aspects, such as substance use, sexuality, and sociocultural stressors. Evidence indicates that chemsex is associated with significantly elevated risks for psychiatric morbidity, somatic complications, and acquisition of STIs, particularly HIV, syphilis, gonorrhoea, and chlamydia. These risks are highest among individuals engaging in multipartner chemsex, slamming, or polysubstance use. Motivational factors, especially minority stress and internalized stigma, play an essential role in sustaining chemsex behaviors and must be integrated into any comprehensive treatment plan.

Current data indicate that interventions targeting chemsex must extend beyond traditional substance-use management. Effective strategies include cognitive-behavioral approaches, preferably peer-led harm-reduction programs, targeted pharmacotherapy for psychiatric symptoms, and digital/mobile-based support tools, which have been shown to improve PrEP adherence and provide real-time guidance. Decriminalization, destigmatization, and improved access to culturally competent sexual health services may further facilitate help-seeking and long-term behavior change.

Given the increasing prevalence and its substantial public health implications, clinicians, especially addiction specialists, sexual health professionals, and policymakers, must collaborate to establish integrated care pathways. Future research should focus on longitudinal outcomes, culturally tailored interventions, and the role of digital therapeutics. Addressing chemsex requires a holistic, highly individualized approach acknowledging the many aspects leading to and sustaining this phenomenon.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.S.O., S.C.R. and D.I.H..; methodology, H.S.O., S.C.R and D.I.H.; validation, H.S.O., S.C.R and D.I.H.; resources, H.S.O., S.C.R and D.I.H.; data curation, H.S.O., S.C.R and D.I.H.; writing—original draft preparation, H.S.O., S.C.R. and D.I.H.; writing—review and editing, H.S.O., S.C.R. and D.I.H.; visualization, H.S.O., S.C.R. and D.I.H.; supervision, S.C.R. and D.I.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

a large language model, ChatGPT 5.1. was used to assist with syntax, punctuation, and grammar corrections.

Conflicts of Interest

H.S.O. previously worked as a study physician in industry-sponsored clinical trials funded by Abbott, Abbott Cardiovascular, Orchestra BioMed and Medtronic, all outside of this work, and states that no current financial relationship exists. S.C.R. reports honoraria for advisory board participation and travel support from Camurus AB. All other authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| SDU |

Sexualized Drug Use |

| SSU |

Sexualized Substance Use |

| MSM |

Men who have sex with men |

| HIV |

Human immunodeficiency virus |

| PrEP |

Pre-exposure prophylaxis |

| PEP |

Post-exposure prophylaxis |

| SSRI |

Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitor |

| PDE-5 |

Phosphodiesterase 5 |

| GHB |

Gamma-hydroxybutyrate |

| GBL |

Gamma-butyrolactone |

| MDMA |

3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine |

| STI |

Sexually transmitted infection |

| NMDA |

N-methyl-D-aspartate |

| PCP |

Phencyclidine |

| 4-MMC |

4-methylmethcathinone |

| WSW |

Women who have sex with women |

References

- Maxwell, S; Shahmanesh, M; Gafos, M. Chemsex behaviours among men who have sex with men: A systematic review of the literature. Int J Drug Policy 2019, 63, 74–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malandain, L; Blanc, JV; Ferreri, F; Thibaut, F. Pharmacotherapy of Sexual Addiction. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2020, 22(6), 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schifano, F; Bonaccorso, S; Arillotta, D; et al. Drugs Used in "Chemsex"/Sexualized Drug Behaviour-Overview of the Related Clinical Psychopharmacological Issues. Brain Sci. 2025, 15(5), 424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donnadieu-Rigole, H; Peyrière, H; Benyamina, A; Karila, L. Complications Related to Sexualized Drug Use: What Can We Learn From Literature? Front Neurosci. 2020, 14, 548704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lunchenkov, N; Cherchenko, N; Altynbekov, K; et al. A way to liberate myself": A qualitative study of perceived benefits and risks of chemsex among gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men in Almaty, Kazakhstan. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2024, 264, 112464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosas Cancio-Suárez, M; Ron, R; Díaz-Álvarez, J; et al. Prevalence, characteristics, and associated risk factors of drug consumption and chemsex use among individuals attending an STI clinic (EpITs STUDY). Front Public Health 2023, 11, 1285057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, AJ; Bourne, A; Weatherburn, P; et al. Illicit drug use among gay and bisexual men in 44 cities: Findings from the European MSM Internet Survey (EMIS). Int J Drug Policy 2016, 38, 4–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramazanova, M; Turdaliyeva, B; Igissenova, AI; et al. Prevalence of Sexualized Substance Use and Chemsex in the General Population and Among Women: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Cross-Sectional Studies. Healthcare (Basel) 2025, 13(8), 899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Íncera-Fernández, D; Román, FJ; Gámez-Guadix, M. Risky Sexual Practices, Sexually Transmitted Infections, Motivations, and Mental Health among Heterosexual Women and Men Who Practice Sexualized Drug Use in Spain. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2022, 19(11), 6387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalil, EM; Torres, TS; de A Pereira, CC; et al. High Rates of Sexualized Drug Use or Chemsex among Brazilian Transgender Women and Young Sexual and Gender Minorities. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2022, 19(3), 1704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawn, W; Aldridge, A; Xia, R; Winstock, AR. Substance-Linked Sex in Heterosexual, Homosexual, and Bisexual Men and Women: An Online, Cross-Sectional "Global Drug Survey" Report. J Sex Med. 2019, 16(5), 721–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berg, RC; Amundsen, E; Haugstvedt, Å. Links between chemsex and reduced mental health among Norwegian MSM and other men: results from a cross-sectional clinic survey. BMC Public Health 2020, 20(1), 1785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giorgetti, R; Tagliabracci, A; Schifano, F; Zaami, S; Marinelli, E; Busardò, FP. When "Chems" Meet Sex: A Rising Phenomenon Called "ChemSex. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2017, 15(5), 762–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romanelli, F; Smith, KM; Thornton, AC; Pomeroy, C. Poppers: epidemiology and clinical management of inhaled nitrite abuse. Pharmacotherapy 2004, 24(1), 69–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Íncera-Fernández, D; Gámez-Guadix, M; Moreno-Guillén, S. Mental Health Symptoms Associated with Sexualized Drug Use (Chemsex) among Men Who Have Sex with Men: A Systematic Review. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021, 18(24), 13299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Gámez, L; Hernández-Huerta, D; Lahera, G. Chemsex and Psychosis: A Systematic Review. Behav Sci (Basel) 2022, 12(12), 516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bohn, A; Sander, D; Köhler, T; et al. Chemsex and Mental Health of Men Who Have Sex With Men in Germany. Front Psychiatry 2020, 11, 542301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarz, J; Gertzen, M; Rabenstein, A; et al. What Chemsex does to the brain - neural correlates (ERP) regarding decision making, impulsivity and hypersexuality. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2025, 275(1), 227–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ung, H; McKeon, G; Jokovic, Z; et al. Long-term neurocognitive side effects of MDMA in recreational ecstasy users following sustained abstinence: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Psychopharmacol. [CrossRef]

- Nikayin, S; Murphy, E; Krystal, JH; Wilkinson, ST. Long-term safety of ketamine and esketamine in treatment of depression. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2022, 21(6), 777–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radparvar, S. The Clinical Assessment and Treatment of Inhalant Abuse. Perm J 2023, 27(2), 99–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shalbafan, M; Orooji, M; Kamalzadeh, L. Psychosis beas a rare side effect of sildenafil: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2022, 16(1), 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Pozo-Herce, P; Baca-García, E; Martínez-Sabater, A; et al. Descriptive study on substance uses and risk of sexually transmitted infections in the practice of Chemsex in Spain. Front Public Health 2024, 12, 1391390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Psomas, CK; Penaranda, G; Retornaz, F; et al. A cohort analysis of sexually transmitted infections among different groups of men who have sex with men in the early era of HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis in France. J Virus Erad. 2022, 8(1), 100065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evers, YJ; Van Liere, GAFS; Hoebe, CJPA; Dukers-Muijrers, NHTM. Chemsex among men who have sex with men living outside major cities and associations with sexually transmitted infections: A cross-sectional study in the Netherlands. PLoS One 2019, 14(5), e0216732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacGregor, L; Kohli, M; Looker, KJ; et al. Chemsex and diagnoses of syphilis, gonorrhoea and chlamydia among men who have sex with men in the UK: a multivariable prediction model using causal inference methodology. Sex Transm Infect. 2021, 97(4), 282–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viamonte, M; Ghanooni, D; Reynolds, JM; Grov, C; Carrico, AW. Running with Scissors: a Systematic Review of Substance Use and the Pre-exposure Prophylaxis Care Continuum Among Sexual Minority Men. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2022, 19(4), 235–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jennings, TL; Gleason, N; Nieblas, F; Borgogna, NC; Kraus, SW. Chemsex and compulsive sexual behavior among sexual minority men. J Sex Med. 2025, 22(4), 658–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muschialli, L; Yang, JC; Engstrom, T; et al. Sexualized drug use and chemsex: A bibliometric and content analysis of published literature. J Psychoactive Drugs 2025, 57(3), 321–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D'Silva, A. Beware the Possible Dangers of Chemsex-Is Illicit Drug-Related Sudden Cardiac Death Underestimated? JAMA Cardiol. 2022, 7(10), 1080–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atila, C; Straumann, I; Vizeli, P; et al. Oxytocin and the Role of Fluid Restriction in MDMA-Induced Hyponatremia: A Secondary Analysis of 4 Randomized Clinical Trials. JAMA Netw Open 2024, 7(11), e2445278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parrott, AC. Recreational Ecstasy/MDMA, the serotonin syndrome, and serotonergic neurotoxicity. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2002, 71(4), 837–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Łukasik-Głebocka, M; Matuszkiewicz, E. Methaemoglobinaemia and respiratory tract irritation connected with poppers inhalation. Przegl Lek. 2010, 67(8), 640–642. [Google Scholar]

- Davies, AJ; Kelly, SP; Naylor, SG; et al. Adverse ophthalmic reaction in poppers users: case series of 'poppers maculopathy'. Eye (Lond) 2012, 26(11), 1479–1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, JE, 3rd; Carson, CC, 3rd. Phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitors as a treatment for erectile dysfunction: Current information and new horizons. Arab J Urol. 2013, 11(3), 222–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaspal, R. Chemsex, Identity and Sexual Health among Gay and Bisexual Men. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2022, 19(19), 12124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McConnell, EA; Janulis, P; Phillips, G, 2nd; Truong, R; Birkett, M. Multiple Minority Stress and LGBT Community Resilience among Sexual Minority Men. Psychol Sex Orientat Gend Divers. 2018, 5(1), 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frost, DM; Meyer, IH. Minority stress theory: Application, critique, and continued relevance. Curr Opin Psychol. 2023, 51, 101579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatcherian, E; Arango-Arroyave, S; Zullino, D; Achab, S. Integrative treatment approach to problematic sexualized drug use (Chemsex) of 3-methylmethcathinone: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2025, 19(1), 486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strong, C; Joson, PA; Huang, P; et al. Developing and testing a digital harm reduction app for GBMSM engaging in chemsex: a feasibility study grounded in users' lived experiences. Harm Reduct J 2025, 22(1), 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lagden, K. Chemsex Interventions for Men Who Have Sex With Men: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Cureus 2025, 17(10), e95731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herrijgers, C; Platteau, T; Vandebosch, H; Poels, K; Florence, E. Using Intervention Mapping to Develop an mHealth Intervention to Support Men Who Have Sex With Men Engaging in Chemsex (Budd): Development and Usability Study. JMIR Res Protoc. 2022, 11(12), e39678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pozo-Herce, PD; Martínez-Sabater, A; Sanchez-Palomares, P; et al. Effectiveness of Harm Reduction Interventions in Chemsex: A Systematic Review. Healthcare (Basel) Published. 2024, 12(14), 1411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).