1. Introduction

Industrial Internet of Things (IIoT) infrastructures are rapidly expanding across various sectors, including energy and power systems such as smart grids, wind and solar farms, and oil and gas pipelines and other Critical National Infrastructures (CNIs) that are based on IIoT sensors, Supervisory Control and Data Acquisition (SCADA) systems, and pressure/flow sensors for remote monitoring and real-time telemetry [

1,

2]. Predictive maintenance of transformers, turbines, and pipelines is also enabled by IIoT. This adoption is not limited to energy; it spans water and waste management, manufacturing and industrial automation, transportation, logistics, healthcare, defence, smart cities, and public infrastructures [

3].

This widespread integration dramatically increases interconnectivity and expands the cyber attack surface. DDoS attacks remain one of the most prevalent and disruptive threats, which is capable of disrupting power grids, water treatment plants, and manufacturing systems within seconds [

4,

5]. Unlike conventional IT/OT environments, IIoT systems are inherently cyber-physical, coupling network communication with real-world sensors and actuators. Consequently, a successful DDoS attack not only consumes computational resources and bandwidth, but also produces measurable effects on physical parameters [

5,

6].

Traditional signature-based and threshold-based Intrusion Detection Systems (IDSs), designed primarily for enterprise or cloud contexts, fail to capture these intertwined cyber-physical dynamics and suffer from high false-positive rates (FPR), as well as complete failure against zero-day attacks [

7]. Machine Learning (ML)-based approaches, such as Random Forest (RF) and Support Vector Machines (SVM), rely on static packet features, while recurrent models like Long-Short-Term-Memory (LSTM) networks, which are sequence-aware, impose heavy computational demands and high latency, which is unsuitable for delay-sensitive critical systems [

8]. Recent advancements in DRL (DRL) show promise for dynamic cybersecurity problems, enabling agents to adaptively learn optimal detection policies in uncertain, evolving environments [

9,

10]. However, most DRL-based solutions remain experimental, and they lack deployment-oriented implementations with real-time inference, edge optimisation, and interoperability [

11,

12].

Recent studies have explored DRL for adaptive DDoS mitigation, reporting high accuracies with inference latencies exceeding 1 ms, which renders them unacceptable for real-time protection of critical systems [

13,

14].

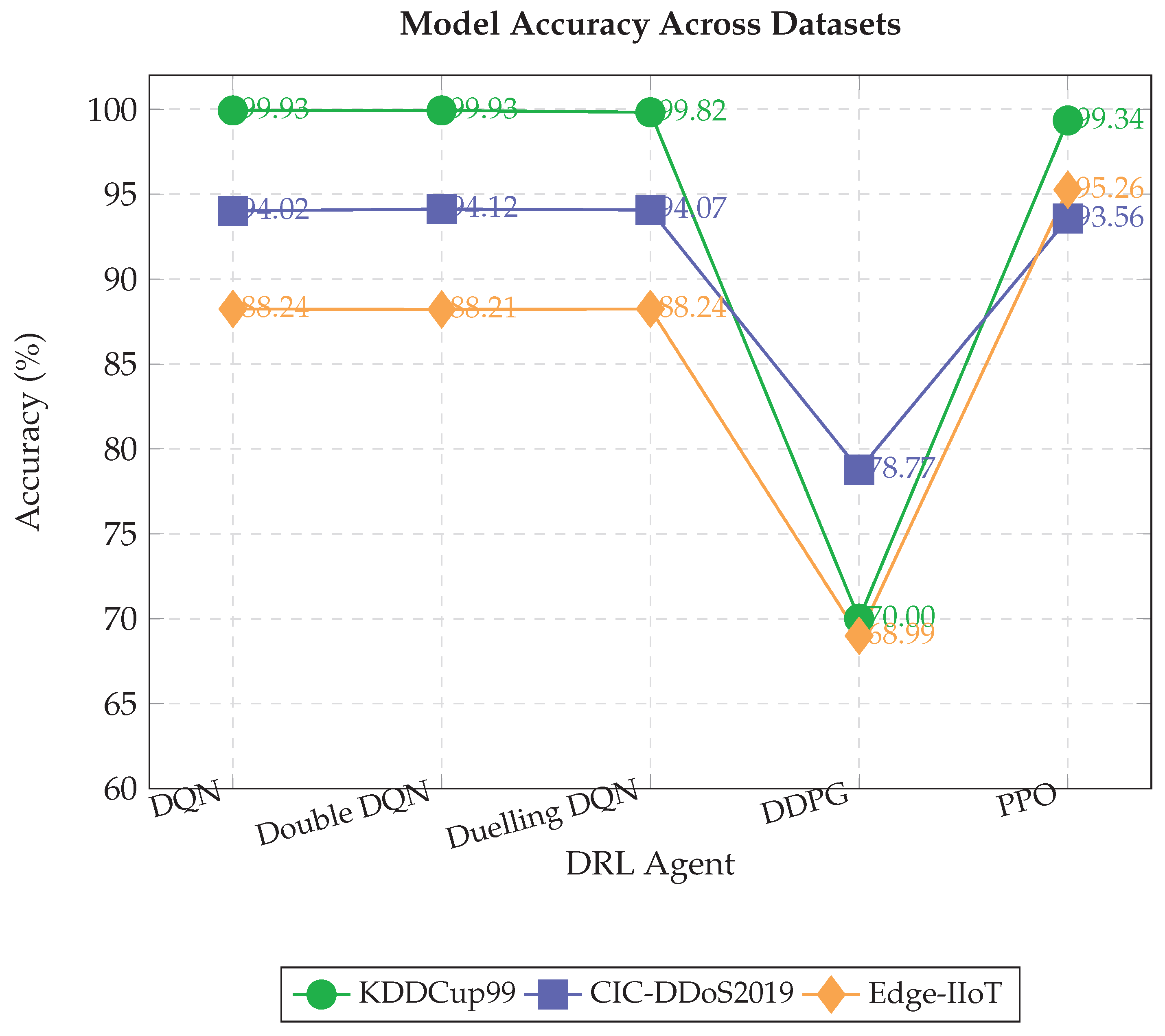

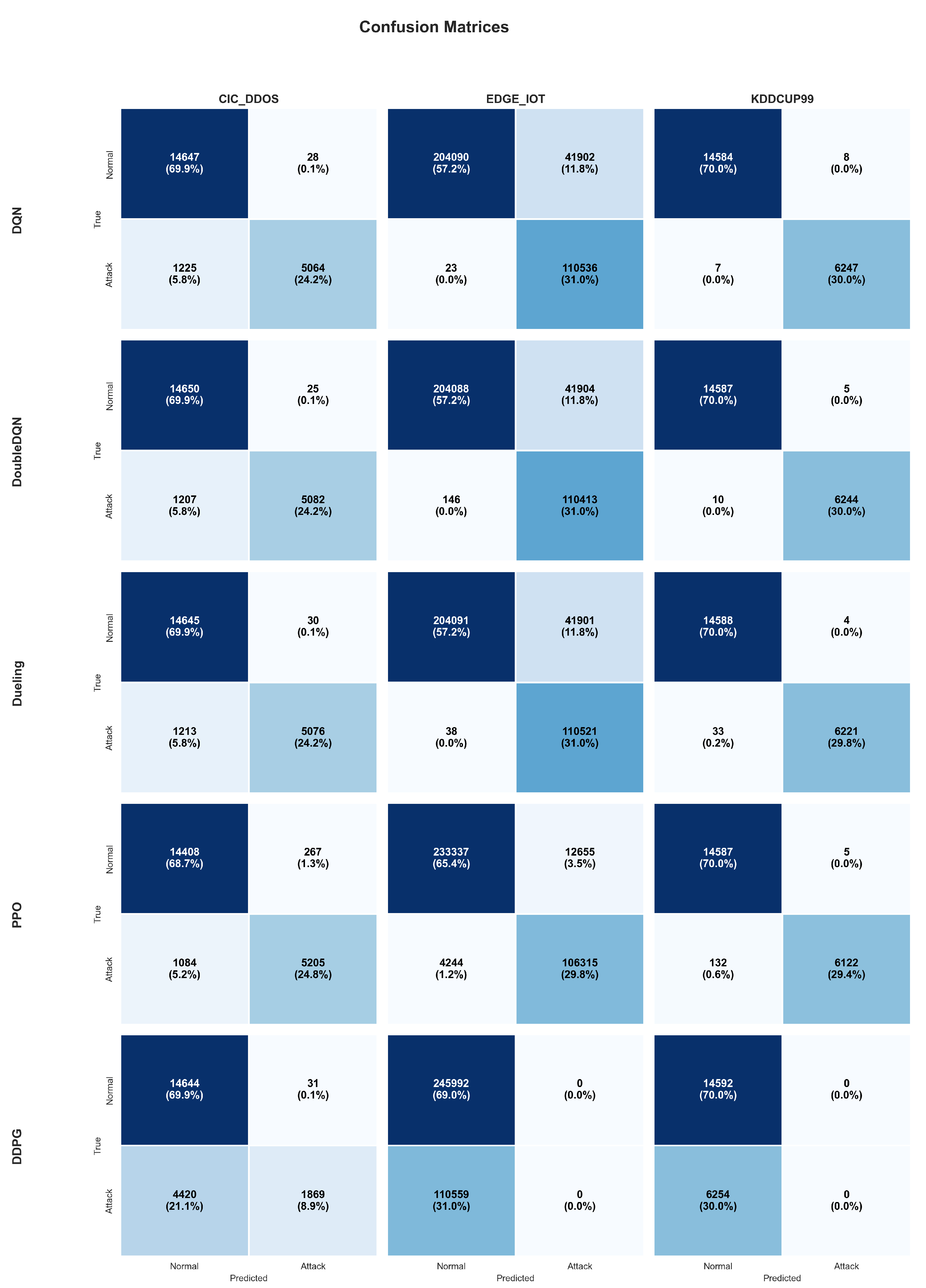

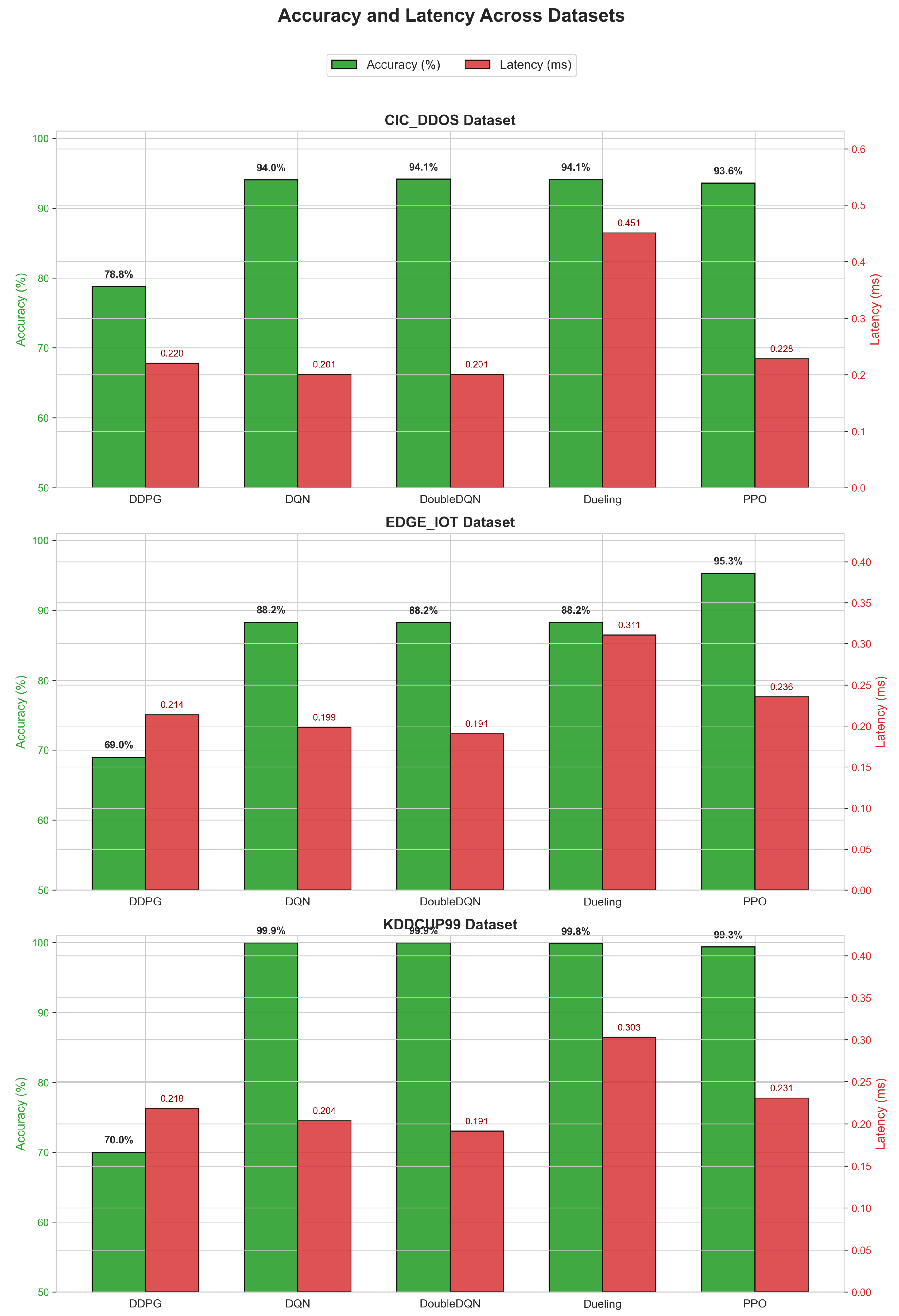

This paper addresses these gaps by presenting a comprehensive multi-model, multi-dataset evaluation of DRL for real-time DDoS detection in IIoT environments. Five state-of-the-art DRL agents: DQN, Double DQN, Duelling DQN, DDPG, and PPO are systematically trained and compared across three benchmark datasets: KDDCup99, CIC-DDoS2019, and Edge-IIoT. A unified preprocessing pipeline with class balancing and robust scaling is applied consistently. Results demonstrate that PPO significantly outperforms the others, achieving 99.3% accuracy on KDDCup99, 93.7% on CIC-DDoS2019, and 95.5% on Edge-IIoT, with inference latency below 0.23 ms per sample and low false positives/negatives.

The main contributions of this work are as follows:

- 1.

A robust, unified preprocessing pipeline applied across three diverse benchmark datasets, enabling fair multi-model comparison.

- 2.

Comprehensive evaluation of five DRL agents, establishing PPO as the superior method for DDoS detection in IIoT environments in terms of accuracy, convergence speed, and real-time performance.

- 3.

End-to-end benchmarking including accuracy, precision, recall, F1-score, FPR/NR, inference latency, and throughput.

- 4.

Export of the best-performing PPO models (one per dataset) to Open Neural Network Exchange (ONNX) format, enabling lightweight, PyTorch-independent deployment on resource-constrained industrial gateways.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows:

Section 2 discusses related work;

Section 3 details the methodology and DRL training pipeline;

Section 4 presents experimental results and evaluation metrics;

Section 5 discusses findings and limitations; and

Section 6 concludes with future research directions.

2. Related Work

RL and DRL have been increasingly explored for intrusion and DDoS detection, particularly in IoT/IIoT settings, with most works evaluated using confusion-matrix-based metrics such as accuracy, precision, recall, F1-score, FPR and FNR.

Based on the survey work, Gueriani et al. [

15] provide a focused survey on DRL-based intrusion detection for IoT environments. They classify existing systems by application domain, such as wireless sensor networks, DQN-based schemes, healthcare, hybrid, and miscellaneous approaches and by the underlying DRL algorithm. The authors synthesise how these systems are designed: state, action, reward, network architecture and how they are evaluated. The result is a clear taxonomy showing that accuracy, precision, recall, FNR, FPR, and F-measure are the dominant metrics used to compare DRL-based IDS models. They give a compact yet detailed map of DRL-IDS design choices and performance trends. However, they do not implement or benchmark new models themselves, so no new confusion matrices or datasets are introduced. Instead, they report on many existing datasets, including NSL-KDD, CICIDS, AWID, and IoT botnet traces used in the surveyed works.

Yang et al. [

16] review DRL techniques for network intrusion detection more broadly, including but not limited to IoT. They focus on what DRL adds compared to conventional deep learning, particularly in handling sequential decision-making, online adaptation, and partial observability. They highlight technical challenges such as training efficiency, detecting minority and unknown attack classes, feature selection, and class imbalance, and systematically compare reported accuracy, recall, precision, and F1-score between DRL and non-DRL models. The strength of this survey includes its algorithmic depth. It dissects how DQN, Double DQN, duelling networks, and actor-critic families are instantiated in NIDS. However, just like Gueriani et al. ([

15]), it is descriptive rather than experimental and uses reported results from other papers.

A complementary survey in SN Computer Science in [

17] systematically categorises RL-based IDS approaches across different environments, including enterprise networks, IoT, and cloud. The authors analyse RL algorithms, including Q-learning, SARSA, DQN, and actor-critic, which are used, observations such as packet/flow features, host-level metrics they consume, and actions such as alerting, rate-limiting, and moving-target defence that they take. Their results are a structured taxonomy and a summary of performance ranges, reported in terms of accuracy, detection rate, precision, and F1-score. The strength here is the unifying view. The paper shows where RL has clear benefits, including adaptive thresholding and sequential defence policies. However, it does not run new experiments, and performance comparisons are indirect because different works use different datasets and label granularities. As in previous surveys, common datasets discussed include NSL-KDD, KDD’99, and CICIDS2017.

A more general survey on cyber security and RL [

18] covers IDS/IPS, IoT, and identity and access management (IAM) systems. It identifies key use-cases such as anomaly-based NIDS, adaptive firewalls, moving-target defence, access-control policy optimisation and summarises how RL models are trained and evaluated. The reported result is that RL-based IDS typically achieve competitive or improved detection rate and accuracy relative to static baselines on datasets such as NSL-KDD, CICIDS, and AWID. The strength is to broaden the view beyond IDS into other control-plane tasks. However, it lacks a unified benchmark or head-to-head comparison, so conclusions about absolute performance are qualitative. The paper aggregates results from a broad set of existing corpora.

In [

19], the authors introduce a transformer-based federated Double Q-Network framework for dynamic intrusion detection in IoT networks. Conceptually, it uses a transformer encoder as a federated aggregator to capture global cross-client patterns, while a dual-layer Q-network separates feature extraction from decision optimisation on each client. Soft Actor-Critic (SAC) is used locally to handle non-IID data and client heterogeneity. The results reported include detection accuracies above 99% on multiple NetFlow-based datasets, including NF-BoT-IoT, NF-ToN-IoT, NF-CSE-CIC-IDS2018-v2, NF-UNSW-NB15-v2 and additional UNSW-MG24 and CIC IIoT 2025 datasets, along with improved F1-scores and reduced FPR compared to centralised or non-transformer baselines. Strong generalisation across heterogeneous datasets and robustness to non-IID client data has been demonstrated. However, the limitations include increased model complexity, higher communication overhead in federated training, and the fact that evaluations are limited to lab-scale environments rather than large production IIoT systems.

Rashid et al. [

20] designed a federated learning-based approach for intrusion detection in IIoT networks, motivated by the privacy and governance limitations of centralised machine learning. Their method trains local models on the Edge-IIoTset dataset, which is an IIoT-specific dataset containing DoS/DDoS, information gathering, MITM, injection, and malware attacks, then aggregates parameters on a central server. They report that their federated global model achieves 92.49% accuracy, very close to their centralised baseline, and comparable precision, recall and F1-scores, which indicates that privacy-preserving training does not dramatically degrade detection quality. Privacy preservation has received serious attention in this work. Raw IIoT traffic never leaves the premises, yet global performance remains high. However, there exists communication overhead between clients and server, sensitivity to client participation patterns, and evaluation on a single dataset, which is Edge-IIoTset; therefore, cross-domain generality is not demonstrated.

The authors in [

21] propose SFedRL-IDS, a federated DRL-based IDS in the agricultural IoT context. The authors combine federated learning with DRL agents deployed across distributed agricultural IIoT nodes. Each node locally learns to detect anomalies using DRL while parameter updates are aggregated securely to form a global model. They show that this approach yields higher accuracy than non-federated DRL or centralised baselines on IoT intrusion datasets, especially under poisoning and unreliable-client scenarios. The strengths are resilience to adversarial or malfunctioning clients and preservation of local data privacy. However, experiments are conducted mostly with synthetic and small-scale real agricultural traces, and the architectural and energy overhead on constrained field devices is not deeply analysed.

In the healthcare domain, the authors in [

22] target the Internet of Medical Things (IoMT) by combining CNN and LSTM for feature extraction with DRL decision-making via DQN and PPO. The system first performs Enhanced Mutual Information Feature Selection, then feeds the selected features to a CNN-LSTM backbone. Finally, a DRL layer, which uses DQN and PPO, refines decisions. Evaluation is conducted on the CICIoMT2024 dataset, it attains a binary-classification accuracy of 99.58 % and a multi-class accuracy of 77.73 % across 18 benign/attack classes, which demonstrates strong binary but moderate multi-class performance. This approach achieves near-perfect detection in binary settings, and its integration of temporal and spatial features with DRL is successful. However, the performance is low on rare attack classes, and it is tailored to IoMT traffic, with no direct evaluation on industrial IoT or DDoS-heavy datasets.

Shi et al. [

23] introduce ID-RDRL, which combines recursive feature elimination and a decision-tree classifier with DRL to build an intrusion-detection model. They first apply recursive feature elimination (RFE) with a tree-based model to remove about 80% of redundant features from the CSE-CIC-IDS2018 dataset. Then, they use a DRL agent with policy, value, and Q-function networks to learn policies that maximise detection rewards. Their reported results include an accuracy of around 96.2% with balanced precision and recall over multiple attack classes, including DoS/DDoS. The efficient feature reduction, which leads to faster inference and strong detection performance across known and some previously unseen attacks make the approach promising. However, sensitivity to hyperparameters and evaluation limited to general-purpose CSE-CIC-IDS2018 rather than IIoT-specific corpora, makes the accuracy questionable.

In [

24], the authors address learning moving-target defence (MTD) strategies by combining federated and reinforcement learning (FRL) in IoT platforms. Rather than directly classifying packets, their approach learns which configuration changes, i.e. MTD actions to perform in response to anomalies detected by a separate analytics module. Its FRL agents choose MTD techniques based on device fingerprinting and anomaly-detection feedback. The results show faster learning and improved attack-mitigation rates compared to centralised RL, as well as robustness when some clients behave maliciously. The main strength is that it operates on real hardware. Ten heterogeneous IoT devices are used in the testbed. However, this work is not focused solely on DDoS; coverage spans various malware and intrusion behaviours, and its performance is measured more in mitigation success and learning time than in accuracy on a specific labelled dataset, which is a testbed in a custom IoT environment with real devices.

López-Martín et al. [

25] reformulate supervised IDS training as a DRL task, replacing the live environment with a “pseudo-environment” that samples labelled records and generates rewards from detection errors. They test four DRL variants: DQN, Double DQN (DDQN), policy gradient, and actor-critic on NSL-KDD and AWID datasets. The results show that DDQN yields the best detection performance, with accuracy and F1-scores that match or exceed classic ML baselines, including SVM, Random Forest, while offering faster inference than deeper architectures. A clean DRL formulation of a supervised problem and the systematic comparison across four RL algorithms are demonstrated in this work. The age and characteristics of the datasets used in this work do not fit NSL-KDD, and AWID are not IIoT-specific, and the approach lacks evaluation on modern, highly imbalanced IoT traffic.

Another DRL-based NIDS, “Network Intrusion Detection using Deep Reinforcement Learning,” [

26] proposes a relatively simple policy network and evaluates several RL variants on multiple intrusion datasets. The authors demonstrate that DRL can improve detection rate and accuracy over non-RL baselines and support online adaptation. However, the architecture and experimental details are lighter than in López-Martín et al. Strengths include architectural simplicity, which makes it easier to deploy and achieve gains in detection metrics on benchmark datasets. The work does not deeply analyse low-rate DDoS, IIoT resource constraints, or latency and energy overhead.

Complementing these general and federated approaches, prior contributions focus more directly on DRL-based DDoS detection and mitigation in SDN and IoT/IIoT environments. A flexible SDN-based framework for slow-rate DDoS attack mitigation combines a deep-learning-based IDS with a DRL-based IPS to counter Slow HTTP Read and similar low-rate attacks [

27]. The IDS that is typically CNN/LSTM-based detects anomalies, and a DRL agent then learns mitigation policies such as flow-rule installation or rate-limiting in an SDN controller. Emulation results in an SDN data-centre testbed show very high detection accuracy, on the order of the high-90% range, and near-perfect DDoS mitigation rate, with limited impact on benign traffic. The evaluation is expressed using confusion-matrix metrics and mitigation ratios. The end-to-end coverage, including detection and mitigation, explicit targeting of stealthy slow-rate attacks and compatibility with SDN are promising. However, the evaluation is only in an emulated data-centre setting and no explicit consideration of highly resource-constrained IoT gateways. The dataset and traffic are based on CICDDoS-style traces plus synthetic workloads in Mininet/ONOS.

A collaborative stealthy DDoS detection method at the IoT edge employs Soft Actor-Critic to dynamically tune lightweight unsupervised detectors deployed on gateways [

13]. In this design, each gateway runs a fast histogram-based outlier score (HBOS) classifier, while a central RL agent learns optimal parameter settings, such as the number of bins and the threshold, based on detection quality feedback from multiple gateways. The results include high detection accuracy for both volumetric and low-rate IoT-based DDoS in experiments using N-BaIoT and a real IoT testbed, while keeping CPU utilisation on gateways under about 2%. The approach is lightweight on-device workload and provides early detection close to the attack source. However, it relies on a central edge server for coordination.

In [

28], an IEEE P2668-compliant multi-layer IoT-DDoS defence system (DRL-MLDS) further integrates DRL with standardised IoT performance indicators. The system learns to classify and mitigate multi-protocol DDoS attacks, including ICMP, TCP SYN, UDP, HTTP, MQTT, and CoAP floods, using DRL to drive per-IP blocking decisions. The results show single-protocol detection accuracies above 96% and multi-layer DDoS detection around 97%, with low FPR and improved applicability index (ADex) values that meet or exceed IEEE P2668’s recommended thresholds. The multi-layer protocol coverage and integration with an IoT readiness standard are promising. Limitations are specialised testbed assumptions and training overhead that may be non-trivial for very constrained devices. The testbed used in this work is a custom multi-layer IoT DDoS environment published as an IEEE DataPort dataset.

Overall, from generic DRL-based NIDS to specialised IoT/IIoT, federated, and DDoS-focused frameworks, the pattern is consistent. RL and DRL models are trained and compared primarily through confusion-matrix metrics such as accuracy, precision, recall, F1-score, FPR, and FNR. In many cases, ID-RDRL, HCLR-IDS, FedT-DQN, and DDoS-oriented systems reported accuracies are above 95%, with notable gains over non-RL baselines in detecting or mitigating DDoS and related attacks [

19,

22,

23,

27].

Table 1.

RL/DRL-based approaches for intrusion and DDoS detection in IoT/IIoT environments

Table 1.

RL/DRL-based approaches for intrusion and DDoS detection in IoT/IIoT environments

| Ref. |

Year |

Approach |

Product/System |

Achievement |

Limitations |

Dataset/Testbed |

| [15] |

2023 |

DRL-based IDS survey |

IoT intrusion detection landscape |

Comprehensive taxonomy of DRL-based IDS |

No implementation or report of its own confusion matrix |

NSL-KDD, CICIDS, andAWID |

| [16] |

2024 |

DRL NIDS survey |

DRL network intrusion detection |

Classifies DRL NIDS by algorithm, state/action/reward design. |

No unified experimental comparison or no new model |

– |

| [17] |

2024 |

RL-based IDS survey |

RL approaches for IDS |

Systematic review of Q-learning, DQN, actor–critic etc. |

Lacks head-to-head benchmarks; largely conceptual |

NSL-KDD, and CIC family |

| [18] |

2022 |

RL for cyber-security survey |

IDS/IPS, IoT, IAM |

Brief overview of RL in security. discusses the use of various metrics. |

Limited depth on IoT/IIoT; no concrete evaluation. |

Multiple cybersecurity datasets surveyed. |

| [19] |

2025 |

Transformer-based federated Double Q-network (FedT–DQN) |

Collaborative IoT IDS |

>99% detection accuracy over centralised baselines |

High training complexity, communication overhead in FL. |

NF-BoT-IoT, NF-ToN-IoT, NF-CSE-CIC-IDS2018-v2, NF-UNSW-NB15-v2, UNSW-MG24, CIC IIoT 2025 |

| [20] |

2023 |

Federated learning with conventional ML |

IIoT IDS for Edge–IIoTset |

Global FL model reaches 92.49 % accuracy, close to centralised training, for multi-class. |

Accuracy slightly below centralised ML. assumes reliable server |

Edge-IIoTset |

| [21] |

2024 |

Secure federated DRL (SFedRL–IDS) |

Agricultural IoT IDS |

Higher detection accuracy and better robustness than non-federated DRL. |

Evaluated mainly in simulated settings. |

Generic sensor-network traces |

| [22] |

2025 |

CNN–LSTM & DRL (DQN/PPO) |

HCLR-IDS for IoMT healthcare |

Binary classification accuracy 99.58%. 18-class multi-class accuracy 77.73%. |

Multi-class performance is notably lower for rare attack types. |

CICIoMT2024 intrusion dataset |

| [23] |

2022 |

Recursive feature elimination & DRL (policy/value/Q-networks) |

ID-RDRL IDS |

Accuracy 96.2% on CSE-CIC-IDS2018. removes ≈ 80% of features with minimal performance loss |

Trained on a single dataset. |

CSE-CIC-IDS2018 |

| [24] |

2023 |

Federated reinforcement learning for moving-target defence |

CyberForce framework for malware mitigation |

Faster learning and higher mitigation success than centralised RL |

Not DDoS-specific, focuses on generic malware. |

Testbed of 10 heterogeneous IoT devices infected by malware |

| [25] |

2020 |

DQN, DDQN, policy gradient, actor–critic |

Supervised DRL-based NIDS |

DDQN, achieves competitive or better accuracy than classic ML, reduced inference time vs. deep networks |

Uses offline labelled data, sensitive to dataset bias |

NSL-KDD and AWID |

| [26] |

2023 |

Deep RL for NIDS |

Generic network intrusion detector |

Improves detection rate and accuracy over non-RL baselines on benchmark NIDS datasets |

Limited details on low-rate DDoS and IIoT scenarios |

NSL-KDD and CICIDS |

| [27] |

2023 |

DL-based IDS & DRL-based IPS for slow-rate DDoS |

SDN data-center slow HTTP DDoS mitigation |

High detection accuracy and near-100% mitigation success in emulated SDN DC. Minimal impact on benign flows |

Tuned for HTTP slow-rate attacks |

CICDDoS2019 & Mininet/ONOS data-center testbed |

| [13] |

2023 |

SAC-tuned HBOS & collaborative RL |

Collaborative IoT edge DDoS detector |

Achieves ≈ 99% accuracy on volumetric and stealthy low-rate IoT-based DDoS with CPU utilisation. |

Requires a central RL server at the edge. HBOS still relies on hand-crafted features |

N-BaIoT dataset & real IoT testbed |

| [28] |

2023 |

DRL-MLDS (IEEE P2668-compliant multi-layer defence) |

Multi-layer IoT DDoS defence system |

Accuracy for single-protocol such as ICMP, TCP SYN, UDP, HTTP, MQTT, CoAP floods and ≈ 97% for multi-layer attacks. |

Tested on a controlled IEEE DataPort testbed. mainly IoT protocols |

Custom multi-layer IoT-DDoS testbed & released dataset (IEEE DataPort) |

3. Methodology

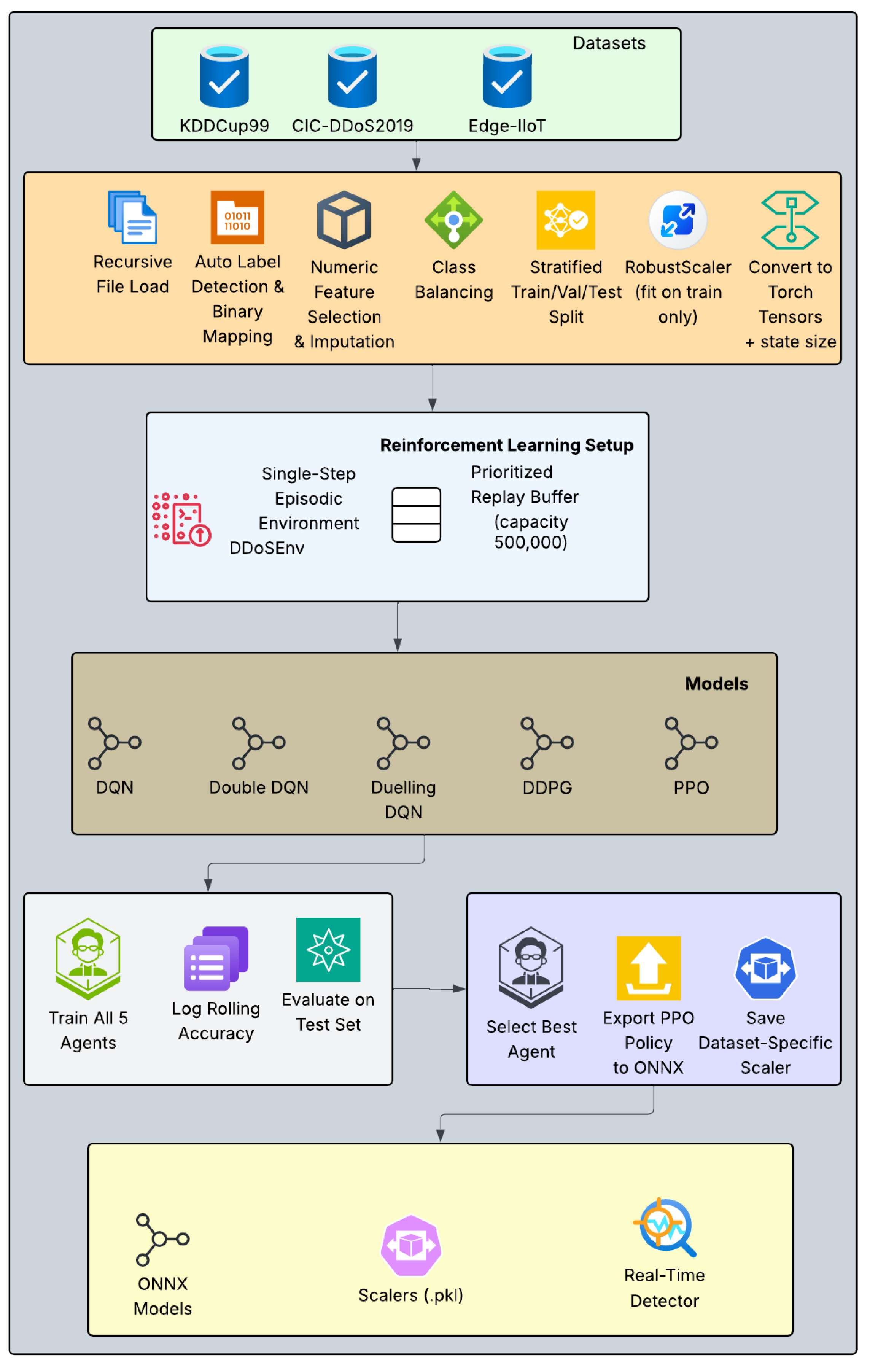

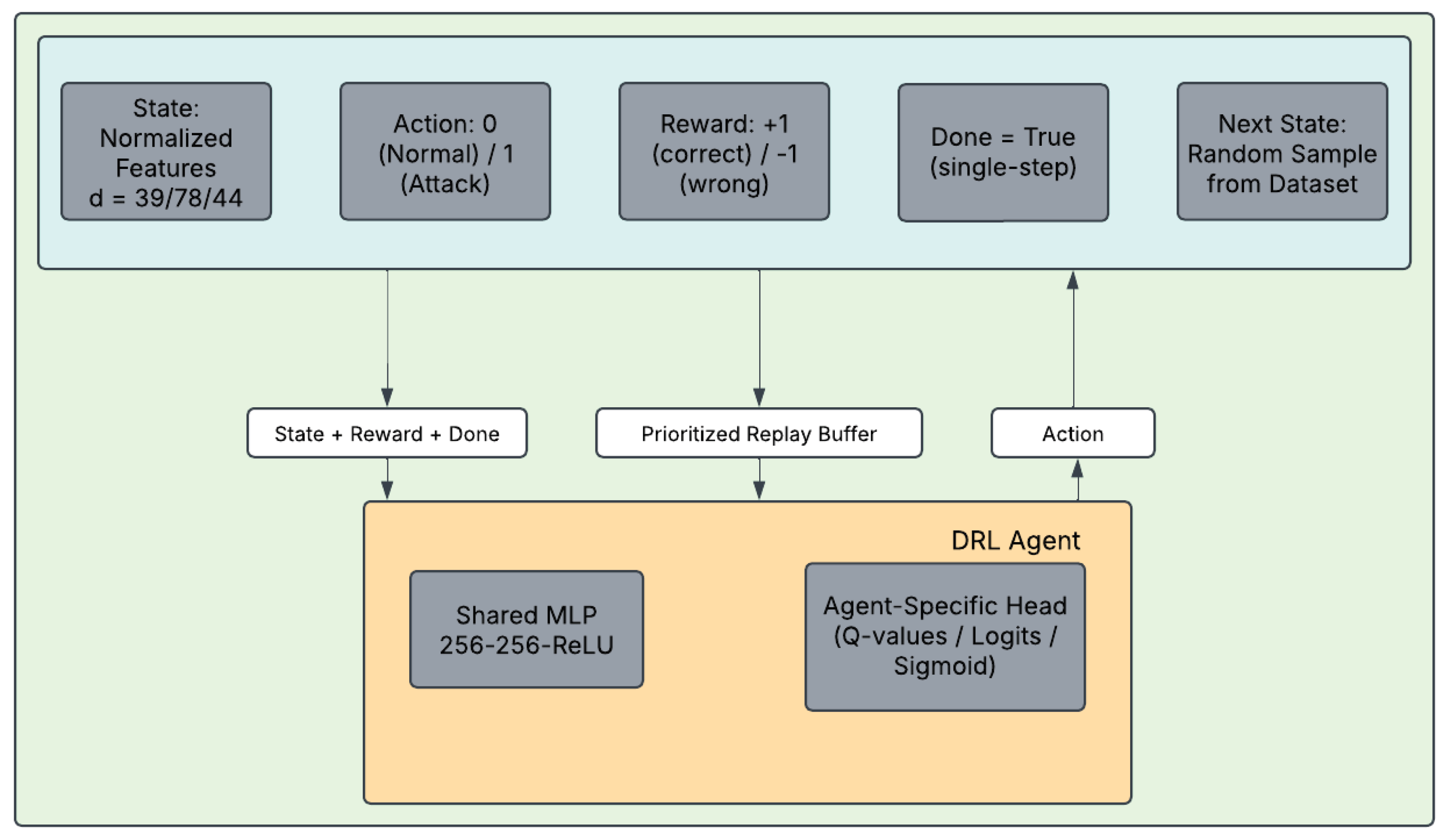

The detection pipeline implemented in this work follows a sequential, modular design comprising data ingestion, unified feature engineering, normalisation, reinforcement learning setup, multi-model agent training, evaluation, and model export. The design ensures stability, interoperability, and deployability across diverse IIoT environments while maintaining real-time performance constraints as illustrated in

Figure 1.

3.1. Datasets

To ensure robust generalisation and enable a fair multi-model comparison, three widely recognised benchmark datasets are employed: KDDCup99, CIC-DDoS2019, and Edge-IIoT. These datasets collectively span diverse network behaviours, attack types, and scales, which make them highly relevant to real-world IIoT security scenarios.

-

KDD Cup 1999

The KDD Cup 1999 dataset remains a foundational benchmark. It comprises approximately 4.9 million simulated connections from the 1998 DARPA evaluation, featuring 41 attributes from TCP/IP headers and payload statistics. Attacks are grouped into DoS, Probe, R2L, and U2R categories, with severe imbalance (

% normal). Numeric features are retained (39 after preprocessing), and undersampling is applied to achieve

% attack ratio, which yields 138,967 balanced samples suitable for edge evaluation [

29].

-

CIC-DDoS2019

The CIC-DDoS2019 dataset provides a modern representation of reflection/amplification attacks captured in 2019. It includes 12 contemporary attack types alongside benign traffic, with 78 engineered flow-level features. After incremental loading and undersampling to

% attack ratio, 139,758 balanced samples are obtained [

30].

-

Edge-IIoTset

The Edge-IIoTset dataset is a comprehensive collection for IIoT security, which features 15 attack families on a multi-layer testbed. It provides 44 features from traffic and logs, with a natural attack ratio of

% . The full balanced portion is retained (test split: 356,551 samples) [

31].

3.2. Data Preprocessing

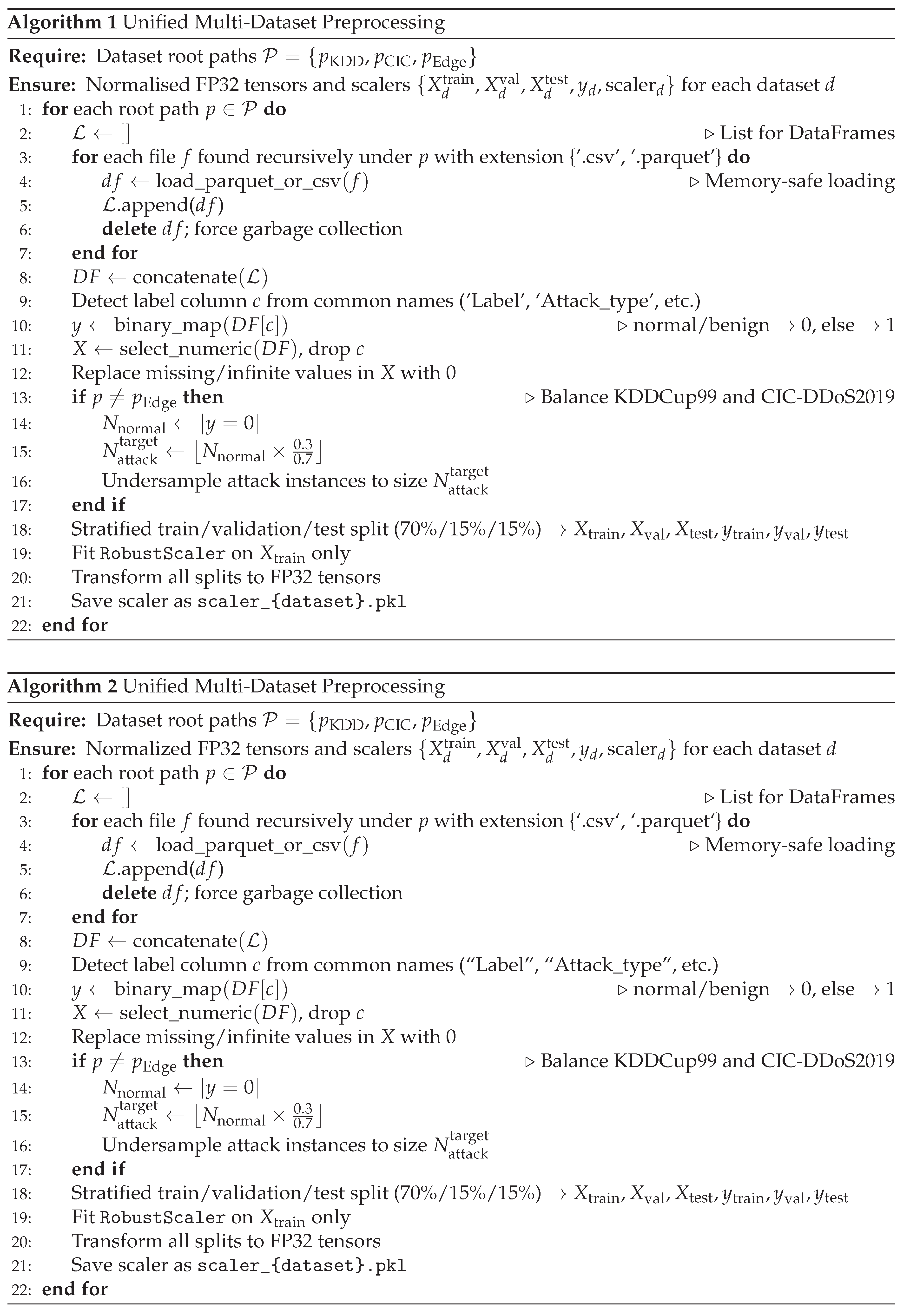

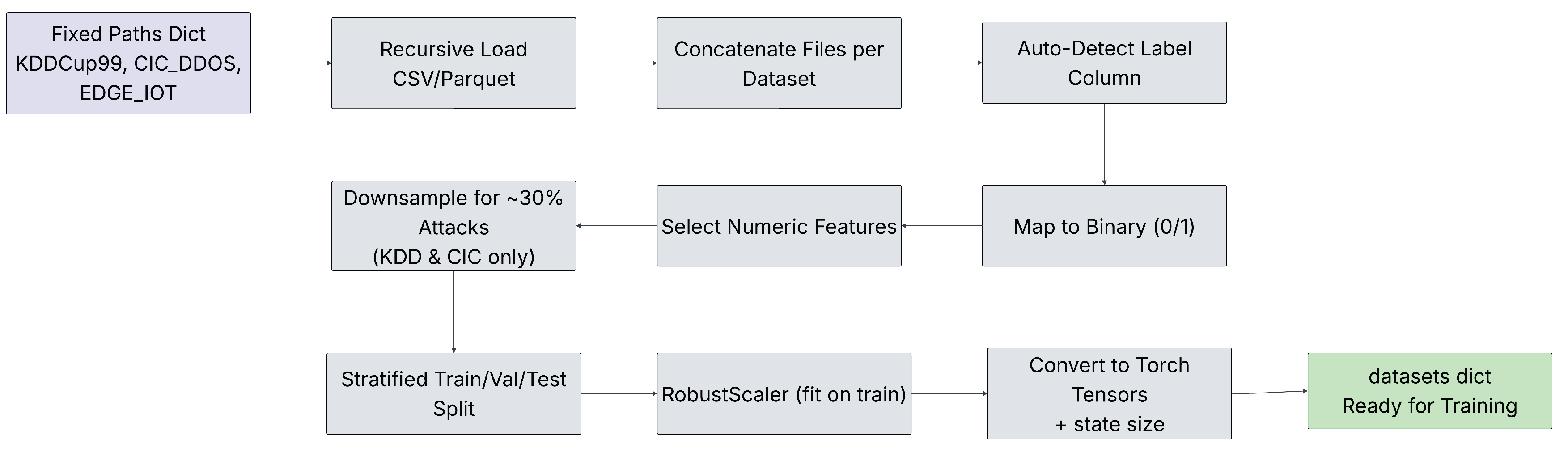

Figure 2 is applied consistently across all three datasets to ensure fair comparison and reproducibility. The pipeline comprises the following steps:

Recursive File Loading and Concatenation: All CSV and Parquet files within the dataset-specific directories are discovered recursively and loaded incrementally to manage memory efficiently, particularly for large collections such as CIC-DDoS2019, which contains multiple files and Edge-IIoTset, which contains two large files. The loaded DataFrames are concatenated into a single unified DataFrame per dataset.

Automatic Binary Label Mapping: The label column is automatically detected using common names (e.g., ’Label’, ’Attack_type’...). Labels are mapped to binary classes (normal/benign = 0, attack/DDoS = 1) via keyword-based rules, to accommodate variations across datasets.

Numeric Feature Selection with Imputation: Only numeric features are retained after dropping the original label column. Missing and infinite values are replaced with zeros to ensure compatibility with downstream tensor operations.

Class Balancing by Under-sampling: KDDCup99 and CIC-DDoS2019 are highly imbalanced. Under-sampling of the majority, which is the normal class, is applied to achieve approximately 30 % attack ratio, in order to prevent artificially inflated accuracy from skewed distributions. Edge-IIoTset exhibits a more balanced natural distribution and is used without further down-sampling.

Stratified Train/Validation/Test Split: A stratified 70%/15%/15% split is performed with a fixed random seed, preserving class proportions in each subset for reliable evaluation.

Normalisation withRobustScaler: The RobustScaler is fitted exclusively on the training split and applied to validation and test splits. This scaler, based on the interquartile range, provides robust handling of outliers prevalent in network traffic data.

This pipeline ensures identical conditions for all five DRL agents while preserving dataset-specific characteristics.

3.3. Data Normalisation and Training

Data normalisation is performed using the

RobustScaler from scikit-learn, which scales features based on the interquartile range and is particularly effective for network traffic data containing outliers [

32]. This approach ensures numerical stability during policy gradient updates, accelerates convergence, and contributes to consistent performance across different hardware environments.

A stratified train/validation/test split of 70%/15%/15% is applied to each dataset, preserving class balance within each split. The exact split sizes are as follows: KDDCup99 used 97,276 samples for training, 20,845 samples for validation, and 20,846 samples for testing. CIC-DDoS2019 used 97,830 samples for training, 20,964 samples for validation, and 20,964 samples for testing. Edge-IIoT used 1,663,900 samples for training, 356,550 samples for validation, and 356,551 samples for testing.

The scaler is fitted exclusively on the training split of each dataset and applied to validation and test splits. Separate scaler files (scaler_kddcup99.pkl, scaler_cic_ddos.pkl, scaler_edge_iot.pkl) are saved to enable correct preprocessing during deployment.

The state representation

for the reinforcement learning agents consists of the full set of normalised numeric features from each respective dataset: 39 numeric features in KDDCup99, 78 numeric features in CIC-DDoS2019, and 44 numeric features in Edge-IIoT. No manual physics-informed features are added beyond the automatic numeric selection, as the benchmark datasets lack synchronised sensor telemetry, unlike the original TON-IoT study. The robust scaling ensures that high-variance network metrics, including packet counts and flow durations, do not dominate gradient updates [

32].

The normalised feature vector

is computed as:

where median and interquartile range (IQR) are estimated from the training data only. This formulation provides outlier resistance while maintaining interpretability for real-time inference on edge gateways.

Training is conducted for 3000 episodes per agent per dataset using Adam optimisation. Rolling accuracy of 1000 episode window monitors convergence. Final evaluation uses the held-out test set, with metrics including accuracy, precision, recall, F1-score, TPR, TNR, FPR, FNR, and inference latency measured on CPU. The best-performing agent (PPO) from each dataset is exported to ONNX format for deployment.

Figure 1 illustrates the complete pipeline from multi-dataset ingestion to production-ready ONNX models.

3.4. Algorithms

The multi-model, multi-dataset training and deployment pipeline is formalised in Algorithm 3, which encapsulates the complete workflow from data ingestion to production-ready ONNX export. This algorithm ensures deterministic reproducibility through fixed random seeds, memory-efficient loading, unified preprocessing, including class balancing and robust scaling, and consistent agent architectures across all three datasets. By iterating over datasets and agents in a nested manner, it systematically trains the five DRL models while logging convergence metrics and selecting the best-performing PPO agent for deployment, resulting in lightweight, PyTorch-independent models optimised for real-time inference on industrial IIoT gateways.

3.5. Reinforcement Learning Formulation

The binary DDoS detection task is formulated as a single-step episodic Markov Decision Process (MDP) to transform the supervised classification problem into a reinforcement learning framework [

33]. Although this results in an effectively one-step classifier, the RL paradigm is adopted for several concrete advantages that supervised learning cannot easily replicate, particularly in security-critical IIoT applications.

The custom environment DDoSEnv implements the MDP as follows:

State : Continuous state space consisting of the normalized numeric feature vector of the current network flow or sample. The dimensionality d adapts automatically to each dataset:

KDDCup99:

CIC-DDoS2019:

Edge-IIoT:

Action : Discrete binary action space (0 = Normal/Benign, 1 = Attack/DDoS).

Transition Dynamics : Deterministic single-step transitions. Upon execution of action , the episode terminates (done = True), and the next state is uniformly sampled from the training set to enable continuous offline training.

Reward Function : Dense scalar reward based on the ground-truth label

:

This dense reward encourages accurate classification at every step [

11].

Discount Factor : Retained for algorithmic compatibility, though its influence is limited in single-step episodes.

A prioritized experience replay buffer with capacity 500,000 is employed to enhance sample efficiency by prioritizing transitions with high temporal-difference (TD) error (

), combined with importance-sampling weights to correct bias [

34].

While the single-step design yields a classifier, the RL formulation provides key benefits over standard supervised learning:

Cost-sensitive learning: The reward can be asymmetric, e.g., heavier penalty for false negatives, without modifying loss functions. Which is critical when missed attacks are far costlier than false alarms.

Online adaptation: The same agent can continue learning from live traffic with minimal code changes, enabling drift handling and zero-day response.

Policy stability: PPO’s clipped objective ensures bounded updates, reducing catastrophic shifts under distribution shift.

Future extensibility: Sequential context, active mitigation, or hierarchical decisions can be incorporated by extending the environment without redesigning the learning algorithm.

Empirically, PPO’s on-policy stability yields faster convergence and higher accuracy than value-based methods across heterogeneous datasets, validating RL even in this simplified setting (

Figure 3).

3.6. DRL Agents

Five state-of-the-art DRL agents are implemented and rigorously compared using a consistent neural network backbone to ensure fair evaluation across all three datasets. The shared architecture consists of a three-layer fully-connected multilayer perceptron (MLP) with 256 units per hidden layer:

where

is the normalised state (input dimension

d adapts automatically: 39 for KDDCup99, 78 for CIC-DDoS2019, 44 for Edge-IIoT), and

is the ReLU activation (PPO uses Tanh in the shared layers for smoother gradients).

The agents are defined as follows:

DQN: Standard Deep Q-Network that combines experience replay with a fixed target network to stabilise training [

35]. Q-values for both actions are estimated directly from the shared MLP backbone, followed by

selection during inference. This baseline provides reliable performance on structured data but can suffer from Q-value overestimation in more complex environments [

36].

Double DQN: An extension of DQN that mitigates overestimation bias by decoupling action selection and value evaluation [

36]. The online network selects the action (

), while the target network evaluates its value, which yields the target

. This simple modification significantly improves stability and final performance on challenging datasets.

Duelling DQN: Further improves value estimation by factorising the Q-function into separate state value

and action advantage

streams, both derived from the shared feature representation [

11]. The final Q-value is reconstructed as

, enabling better credit assignment and often accelerating learning in environments with many similar states [

11].

DDPG: Originally designed for continuous action spaces, the Deterministic Policy Gradient actor-critic algorithm is adapted here for discrete binary actions. The actor network outputs a sigmoid probability for the attack class, with inference performed via thresholding at 0.5. The critic estimates Q-values using the same shared backbone. Exploration is achieved through added noise during training. Despite the adaptation, DDPG shows limited effectiveness on this discrete task compared to on-policy methods [

37].

PPO: Proximal Policy Optimisation, an on-policy clipped policy gradient method with actor-critic architecture. Separate policy (actor) and value (critic) heads are attached to the shared MLP backbone, allowing simultaneous policy improvement and value function estimation [

38]. The clipped surrogate objective prevents large policy updates, ensuring stable and monotonic improvement. PPO demonstrates superior sample efficiency, fastest convergence, and the highest final accuracy across all three datasets, making it the recommended approach for real-time IIoT DDoS detection [

38,

39].

Value-based agents which are DQN, Double DQN, and Duelling DQN, employ prioritised experience replay and periodic target network updates. Hyperparameters, including learning rate, batch size, and discount factor (), are kept consistent where applicable to isolate algorithmic differences. This controlled setup ensures that observed performance variations are attributable to the learning algorithms rather than architectural discrepancies.

3.7. DRL Algorithms and Training

Five DRL agents: DQN, Double DQN, Duelling DQN, DDPG, and PPO are implemented and compared using a consistent neural network architecture to ensure fair evaluation across all three datasets. All agents share a three-layer fully-connected multilayer perceptron (MLP) with 256 units per hidden layer and ReLU activations:

where

is the normalised state (input dimension

d adapts automatically: 39 for KDDCup99, 78 for CIC-DDoS2019, 44 for Edge-IIoT),

is the ReLU activation, and the output dimension is 2 (Q-values or policy logits) for discrete agents.

The agents are defined as follows:

DQN: Standard Deep Q-Network with experience replay and fixed target network [

11]. Q-values are estimated directly from the shared architecture. Trained using Huber loss on the TD error:

Double DQN: Reduces Q-value overestimation by decoupling action selection and evaluation [

25,

36]:

Duelling DQN: Factorises Q-values into state value

and advantage

streams [

11]:

improving credit assignment and convergence.

DDPG: which is adapted for discrete actions [

36,

40]. Actor-critic method with a deterministic policy network outputting a sigmoid probability for the attack class. Action selection uses thresholding at 0.5. The critic estimates Q-values using the same architecture as DQN. Updates follow the deterministic policy gradient with added exploration noise.

PPO: On-policy actor-critic algorithm with separate policy (actor) and value (critic) heads on the shared backbone [

11]:

Trained using the clipped surrogate objective:

combined with value function loss and entropy regularisation for exploration.

Value-based agents which are DQN, Double DQN, Duelling DQN employ prioritised experience replay (capacity 500,000,

) with importance-sampling weights (

annealed from 0.4). Target networks are updated every 50 episodes. PPO uses minibatch updates over collected trajectories with 4 epochs per update. All agents are trained for 3000 episodes on each dataset, as shown on

Table 2, using the Adam optimiser. Hyperparameters, which include learning rates, batch size 256, and discount

are kept consistent where applicable. Despite identical network capacity,

PPO consistently achieves the highest accuracy and fastest convergence across all datasets, reaching over 93 % accuracy within 1500 episodes on the most challenging datasets and 99.3 % on KDDCup99.

The best-performing agent PPO is exported to ONNX format for each dataset using PyTorch’s native exporter with opset 18 and dynamic batch axes. This results in three lightweight models, approximately 1-2 MB each, supporting CPU-only execution via ONNX Runtime, eliminating any PyTorch dependency in production. Inference latency remains consistently below 0.23 ms per sample across all datasets on standard CPU hardware, confirming real-time capability for delay-sensitive IIoT applications. Separate scalers and ONNX models per dataset ensure correct preprocessing and optimal performance in heterogeneous environments.

5. Discussion and Limitations

The results confirm that PPO is the most effective DRL algorithm for binary DDoS detection across diverse IIoT-relevant datasets. PPO’s on-policy clipped objective provides superior stability and sample efficiency compared to off-policy value-based methods, which enables faster convergence and higher final accuracy even on high-dimensional inputs i.e. 78 features in CIC-DDoS2019. While value-based agents, including DQN, Double DQN, and Duelling DQN, achieve near-perfect performance on the structured KDDCup99 dataset, their effectiveness decreases on more heterogeneous traffic patterns, which highlights limitations in handling complex distributions with standard Q-learning [

41]. DDPG’s poor performance underscores the mismatch between continuous-action algorithms and discrete classification tasks.

A recent hybrid approach [

42] combines supervised base learners (Random Forest and CatBoost) with a PPO agent that dynamically adjusts ensemble weights via an MLP meta-learner. While achieving high accuracy on several datasets, this method differs fundamentally from our pure DRL formulation. Our work employs PPO (and four other DRL agents) as standalone classifiers that directly map normalized features to binary decisions within a single-step Markov Decision Process. In contrast, the hybrid method uses PPO solely as a meta-controller to weight predictions from pre-trained supervised models. This architectural difference yields several advantages in our favor:

First, our approach eliminates the need for multiple large supervised base learners, resulting in significantly lower model complexity and resource requirements. The hybrid method must maintain and inference with both RF and CatBoost models alongside the PPO controller, whereas our solution uses a single lightweight MLP backbone (256–256 units) shared across agents. Consequently, our exported ONNX PPO models require only 1–2 MB storage and achieve sub-0.23 ms latency on CPU, compared to the substantially higher footprint and overhead of running an ensemble stack.

Second, direct end-to-end reinforcement learning enables richer representation learning through dense reward feedback, rather than relying on potentially biased confidence scores from supervised models. This contributes to PPO’s robust performance across heterogeneous datasets (KDDCup99, CIC-DDoS2019, Edge-IIoT) without requiring hand-crafted ensemble weighting strategies.

Third, our pure DRL design offers greater interpretability and deployability: a single policy produces the final decision, with no intermediate supervised components. The hybrid approach introduces additional failure points and calibration challenges when base learner confidences are unreliable.

Finally, our comprehensive five-agent comparison establishes clear benchmarks, showing that a single well-designed DRL agent (PPO) can match or exceed complex ensembles while being dramatically simpler and more suitable for resource-constrained IIoT gateways. These advantages lower complexity, reduced resource demands, direct feature-to-decision mapping, and streamlined deployment, which make our pure DRL approach superior for real-time DDoS detection in critical industrial environments.

The multi-dataset evaluation reveals important insights into generalisation: PPO maintains strong performance 93.7 % – 99.3 % across datasets with varying feature types and class distributions, which demonstrates robustness beyond the original physics-informed setting. The low FN rates achieved by PPO are particularly valuable for security applications, where missed attacks are costlier than false alarms [

7]. Inference latency below 0.23 ms per sample on CPU confirms real-time feasibility, with ONNX export enabling lightweight deployment without PyTorch dependencies. This addresses a key gap in prior DRL security research, which often remains simulation-only [

36,

43].

Limitations include:

Dataset-specific training is required for optimal performance; direct cross-dataset transfer yields low accuracy due to domain shift.

Evaluation is offline; online adaptation in live IIoT traffic remains future work.

Computational cost during training may limit frequent retraining in production.

Despite these, the proposed pipeline establishes PPO as a practical, high-performance solution for IIoT DDoS detection.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.A.,M.C.G., H.K., C.A.K., G.R; Methodology, M.A.,M.C.G., H.K., C.A.K., G.R; Software, M.A.,M.C.G., H.K., G.R; Validation, M.A.,M.C.G., H.K., G.R; Formal Analysis, M.A.,M.C.G., H.K., C.A.K., G.R; Investigation, M.A.,M.C.G., H.K., C.A.K., G.R; Resources, M.A.,M.C.G., H.K., C.A.K., G.R; Data Curation, M.A.,M.C.G., H.K., C.A.K., G.R; Writing—Original Draft, M.A.,M.C.G., H.K., C.A.K., G.R; Writing—Review and Editing, M.A.,M.C.G., H.K., C.A.K., G.R; Visualization, M.A.,M.C.G., H.K., C.A.K., G.R; Supervision, M.C.G., H.K., C.A.K., G.R; Project Administration, M.A.,M.C.G., H.K., C.A.K., G.R; Funding Acquisition, M.A., M.C.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.