1. Introduction

Dendrobium officinale (DO) is a highly valued medicinal and edible plant with a long history of use in traditional Chinese medicine [

1]. Fresh DO is highly perishable, and its bioactive components are prone to degradation or loss during storage and transportation. To overcome this limitation, DO is commonly processed into “Fengdou” for long-term preservation and commercial distribution [

2,

3]. Polysaccharides are widely recognized as one of the major active constituents of DO. They exhibit multiple biological activities, such as antioxidant, anti-aging, constipation-relieving, and hypolipidaemic effects, together with low toxicity and excellent biocompatibility, making them more suitable than many synthetic drugs for long-term dietary intervention [

4,

5]. Notably, thermal treatment and dehydration steps during processing may alter the molecular weight, monosaccharide composition, and molecular conformation of polysaccharides, thereby markedly affecting their physicochemical properties and bioactivities [

6,

7,

8]. However, systematic comparative studies on the structural characteristics and activity changes of DO polysaccharides before and after processing are still limited. Clarifying such changes is essential for the relationships between the structure and activity of the bioactive components and for guiding the rational application of DO.

In traditional Chinese medicine theory, DO is attributed to the stomach and kidney meridians and has long been used to “invigorate the stomach, promote fluid production, nourish yin and clear heat” [

9]. Modern pharmacological studies further indicate that DO has potential benefits in improving gastrointestinal function and regulating glucose and lipid metabolism [

10,

11,

12]. Based on this, the present study focuses on the effects of DO polysaccharides on relieving constipation and modulating blood lipids. These two increasingly prevalent disorders are pathophysiologically linked, as intestinal motility and microbiota homeostasis play a role in lipid digestion and metabolism, while dyslipidemia can exacerbate intestinal dysfunction [

13]. Therefore, identifying natural components that can simultaneously improve intestinal motility and lipid metabolism is of considerable value. Clinically, constipation is often treated with agents such as polyethylene glycol, domperidone, and lactulose. Although these can alleviate symptoms, they are associated with adverse effects, including unpleasant taste, arrhythmia, abdominal pain, and diarrhoea, which limit their long-term safety and patient compliance [

14]. Meanwhile, shifts in dietary patterns and lifestyle have contributed to a rising incidence of hyperlipidaemia, with onset occurring at younger ages [

15]. As a major risk factor for cardiovascular morbidity and mortality, hyperlipidaemia has made lipid-lowering intervention a public health priority [

16]. Although statins are effective in lowering blood lipids, they are associated with potential side effects such as hepatotoxicity, elevated blood glucose, and gastrointestinal discomfort [

17]. Accordingly, there is a growing need to identify natural products with higher safety profiles that possess both constipation-relieving and lipid-lowering activities, providing new candidates for functional foods and adjunctive therapies.

To evaluate these activities in vivo, zebrafish were employed as an experimental model in this study. Zebrafish share up to 70% genome similarity with humans, and their intestinal tissue architecture, epithelial cell lineages, and peristaltic function are highly comparable to those of mammals, making them well-suited for investigating intestinal motility and related mechanisms [

18,

19,

20]. In addition, key regulators of lipid metabolism, such as SREBF1, PPARα/γ, and ApoB, are conserved in zebrafish, and their responses to high-fat or high-cholesterol diets closely resemble those observed in mammals, enabling the establishment of stable in vivo models of hyperlipidaemia, hepatic steatosis, and systemic lipid accumulation. The optical transparency of zebrafish embryos and larvae further allows real-time imaging of lipid deposition and metabolic dynamics using lipophilic fluorescent probes or specific stains, providing an attractive high-throughput platform for screening natural compounds with lipid-modulating and gut-protective activities [

21,

22].

Taken together, this study aimed to isolate and purify polysaccharide fractions from fresh DO and its processed product, Fengdou, systematically compare their structural characteristics, including molecular weight, monosaccharide composition, spectral features, and morphology, and, using zebrafish models, evaluate in vivo their dual activities in relieving constipation and regulating blood lipids. These findings are expected to provide a scientific basis for the development of DO-derived dietary polysaccharides with dual regulatory functions on intestinal and metabolic health.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials and Chemicals

Fresh stems of DO and the processed product Fengdou were obtained from a DO production facility in Longling County, Yunnan Province, China. Processing was conducted in accordance with local standard procedures. Cellulose-DEAE-52 cellulose column (26 mm × 50 cm) and Sephadex-G-150 column (26 mm × 50 cm) were procured from Shanghai Yuanye Biotechnology Co. (Shanghai, China).

Wild-type AB strain zebrafish were provided by the China Zebrafish Resource Center and maintained under standard conditions. Breeding was achieved through natural pairing. All animal experiments were performed in compliance with the Guidelines for the Ethical Treatment of Laboratory Animals issued by the Ministry of Science and Technology of China. The experimental protocol was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Institute of Agricultural Products Processing, Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences (Approval No. 20240811-06).

Anhydrous ethanol, sodium hydroxide, hydrochloric acid, concentrated sulfuric acid, and sodium chloride were all purchased from China National Pharmaceutical Group Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China). Trifluoroacetic acid, 4-nitrophenyllauric acid ester, pancreatic lipase, orlistat, and P-nitrophenyl butyrate (PNPB) were all purchased from Shanghai McLean Biochemical Technology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). Anhydrous glucose, D-galacturonic acid, meta hydroxybiphenyl, and monosaccharides fucose (Fuc), rhamnose (Rha), arabinose (Ara), galactose (Gal), glucose (Glc), mannose (Man), gluconic acid (GlcA), and galacturonic acid (GalA) were all purchased from Solarbio Technology Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China). Formaldehyde, phenol, Oil Red O dye, Nile Red dye, Tricaine, and 3% methylcellulose were all purchased from Guangda Hengyi Technology Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China). Loperamide hydrochloride, domperidone, egg yolk powder, atorvastatin, and PBS buffer were all purchased from Yuanye Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). All other chemicals are analytical grade or chromatographic grade.

2.2. Extraction and Purification of Dendrobium officinale Polysaccharides

2.2.1. Polysaccharide Extraction from Dendrobium officinale

DO polysaccharides were extracted with modifications based on the method of Zhou et al. [

22]. Fresh stems and Fengdou samples, with equivalent dry weights, were weighed and soaked in ultrapure water for 30 min at a solid-to-liquid ratio of 1:20 (w/v). The mixtures were then incubated in hot water at 80 °C for 2 h. After extraction, the two filtrates were combined and concentrated to one-quarter of their original volume. Anhydrous ethanol was slowly added to the concentrated solution to achieve a final ethanol concentration of 80%, followed by overnight standing at 4 °C. The resulting precipitates were repeatedly washed with 80% ethanol and dried at room temperature. The dried product was then re-dissolved, mixed with 4% activated carbon, and decolorized at 40 °C for 1 h. After centrifugation, the supernatant was treated with Sevag reagent (chloroform: n-butanol = 4:1) at a ratio of 1:4 (v/v) to remove proteins. The deproteinized supernatant was then subjected to rotary evaporation to remove residual organic solvents and concentrated appropriately. The resulting concentrate was dialyzed against distilled water for 3 days with water changes every 4 hours. Finally, the solution was freeze-dried to obtain two groups of crude DO polysaccharides.

2.2.2. Purification of DO Polysaccharides

500 mg crude polysaccharide was initially fractionated by anion-exchange chromatography on a DEAE-52 cellulose column (26 mm × 50 cm) using a linear gradient of 0–0.5 M NaCl. All collected eluates were subjected to ultrasonic treatment. Further purification was performed by gel filtration on a Sephadex G-150 column (26 mm × 50 cm). The carbohydrate content in the eluted fractions was monitored by the phenol-sulfuric acid method, measuring absorbance at 490 nm. Based on the resulting elution profile, target fractions were pooled, concentrated, dialyzed, and finally lyophilized under vacuum for storage. The purified polysaccharides obtained from fresh and dried stems of Dendrobium officinale were designated as FDOP and DDOP, respectively.

2.3. Ultraviolet-Visible Spectroscopy (UV) Analysis

Accurately weigh 10.0 mg of FDOP and DDOP, respectively, and dissolve them in ultrapure water to prepare polysaccharide solutions at a concentration of 1 mg/mL. The solutions are then placed in quartz cuvettes and scanned across a wavelength range of 190–500 nm using a UV spectrophotometer (Shimadzu, Japan) with ultrapure water as the background reference.

2.4. Molecular Weight Determination

The molecular weight distribution of the two polysaccharides was determined using high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) coupled with multi-angle light scattering detection. Analyses were performed on a Waters HPLC system equipped with an 18-angle light scattering detector and a Shodex 806 column. The mobile phase consisted of 0.1 M sodium chloride solution, delivered at a flow rate of 0.5 mL/min with the column temperature maintained at 35 °C. A series of dextran standards with known molecular weights was dissolved in ultrapure water (2 mg/mL), filtered through a 0.45 μm aqueous membrane, and injected (100 μL). Similarly, polysaccharide samples (10 mg) were dissolved in 5 mL of 0.1 M sodium chloride, filtered through a 0.45 μm aqueous membrane, and injected for chromatographic analysis.

2.5. FT-IR Analysis

The polysaccharide samples and anhydrous potassium bromide powder were thoroughly crushed and transferred into the mold of the pressing container to produce uniform, transparent, and crack-free flakes, which were examined using an FT-IR spectrometer (TENSOR 27, USA) across the range of 4000 cm-1 to 400 cm-1 [

23].

2.6. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

FDOP and DDOP samples were horizontally placed on the sample stage with uniform thickness and securely pressed into position. After gold coating, the samples were transferred to a Hitachi SU8010 instrument for observation. The microstructural morphology of the samples was examined at a magnification of 500×.

2.7. Monosaccharide Analysis

Monosaccharide composition was detected by ion chromatography (IC) according to the method described by Wang et al. with minor modifications [

24]. 10 mg of FDOP and DDOP were loaded in a hydrolysis tube, and then 4 mL of 4 mol/L trifluoroacetic acid was added, purging with nitrogen for 1 min to exhaust the air from the tube. The polysaccharides were hydrolyzed at 120 ℃ for 4 h after tightening the screw cap. Upon cooling, the hydrolysate was dried with nitrogen blow, subsequently introducing methanol in the requisite quantity to eliminate surplus trifluoroacetic acid. Following this, ultrapure water was incorporated to achieve a 20-fold dilution and then filtered over a 0.2 µm membrane. Chromatographic separation conditions: CarboPacTMPA20 3×150 mm column; eluent: ultrapure water, 250 mM NaOH, and 1 M NaAc; detector: pulsed amperometric detector with gold electrode; flow rate of 0.5 mL/min; injection volume: 10 µL; column temperature: 35 ℃; the conditions of the mobile phase are detailed in

Table S1.

2.8. Methylation Analysis

The methylation analyses of the sample were performed in accordance with a previously described method by Zhang et al. [

25]. After post-treatment, the resultant products were hydrolyzed with 2 M TFA at 120 °C for 2 h, followed by reduction with NaBD4 and acetylation with acetic anhydride to yield partially methylated alditol acetates. These acetates were analyzed with GC–MS using an HP-5 MS fused silica capillary column (30 m × 0.25 mm, 0.25 μm, Agilent). The column temperature was set to 120 °C during injection, then increased by 4 °C/min to 280 °C and maintained at 280 °C for 5 min. Helium was used as the carrier gas. Mass spectra were interpreted to identify the compounds that corresponded to each peak. The molar ratio of each residue was calculated based on peak areas.

2.9. NMR Analysis

FDOP and DDOP (50 mg) were dissolved completely in 500 µL of D2O, respectively. The 1H NMR, 13C NMR, COSY, HSQC, and HMBC spectra were recorded using a Bruker spectrometer (700 MHz).

2.10. Animal Experimental Design

Wild-type AB strain zebrafish were provided by the Zebrafish Resource Center of China and were maintained in a recirculating aquaculture system in our laboratory. All experimental protocols and procedures were approved by the Ethics Committee of the Institute of Agro-Products Processing, Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences (Approval No. 230320). The environmental temperature was maintained at 28–30 °C, with feeding occurring twice daily, in the morning and evening, according to a 14-hour light and 10-hour dark cycle. Zebrafish were bred through natural pairing, and their living environment was regularly cleaned to ensure optimal conditions.

2.11. Constipation-Relieving Activity Test

The zebrafish constipation model was established according to the method of Lu et al., with minor modifications [

26]. Briefly, 5 days post-fertilization (dpf) larvae were incubated with 10 μg/L Nile Red for 16 h to fluorescently label intestinal lipids, followed by rinsing with embryo culture water. Constipation was modeled by exposing larvae to 10 μg/mL loperamide hydrochloride for 24 h to inhibit intestinal motility, while the blank group was maintained in embryo culture water under the same conditions. After treatment, zebrafish were euthanized by immersion in 0.2% tricaine methanesulfonate (MS-222) and immobilized in 3% (w/v) methylcellulose to preserve intestinal morphology during imaging. Intestinal fluorescence intensity was quantified using ImageJ software, and statistical analyses were performed with SPSS to verify successful model establishment.

Constipated larvae were randomly divided into eight groups (n = 30 per group): a blank group, a model group, a domperidone (positive control), a polyethylene glycol group, and groups treated with FDOP or DDOP at different concentrations. After 24 h of administration, larvae were rinsed three times with embryo culture water. Intestinal motility was evaluated indirectly by measuring the fluorescence intensity of Nile Red in the gut, with higher fluorescence indicating greater retention of intestinal contents and more severe constipation.

2.12. Hypolipidemic Activity Test

2.12.1. In Vivo Lipid-Lowering Activity in Zebrafish

The 5 dpf zebrafish were immersed in a 0.2% egg yolk powder solution for 48 h with daily water changes to promote rapid lipid buildup and to establish a high lipid model following the method of Xiao et al., with minor modification [

27]. After modelling, larvae were randomly divided into eight groups (n = 30 per group): control group, model group, atorvastatin group (0.4 µM), and five FDOP- or DDOP-treated groups at 12.5, 25, 50, 100, and 200 µg/mL. Larvae were incubated with the respective treatments for 24 h. At the end of treatment, the egg yolk solution was removed, the fish were rinsed three times with PBS, and euthanized by immersion in 0.2% tricaine methanesulfonate (MS-222). The larvae were then fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde at 4 °C overnight, dehydrated through a graded methanol series (0, 25, 50, 75, and 100%), stained with 1 µg/mL Oil Red O, and rehydrated with methanol in reverse order. After three additional washes with PBS, the stained larvae were embedded in 3% (w/v) methylcellulose and photographed under a microscope. The integrated optical density (IOD) of Oil Red O-stained lipids was quantified using Image-Pro Plus software, and statistical analysis was performed with SPSS to evaluate lipid accumulation in vivo.

2.12.2. In Vitro Pancreatic Cholesterol Esterase (PCE) and Pancreatic Lipase (PL) Activity Test

1. Inhibition of PCE

The inhibitory activity of FDOP and DDOP against PCE was assessed according to the method of Long et al., with slight modifications [

28]. Briefly, PCE and polysaccharide samples were separately dissolved in distilled water, with the latter serially diluted to target concentrations. The reaction system consisted of 1.0 mL of phosphate buffer (5.16 mmol/L, pH 7.0, containing 0.10 mol/L NaCl), 100 µL of enzyme solution, and 100 µL of polysaccharide sample. After pre-incubation at 25 °C for 5 min, the reaction was initiated by adding 50 µL of p-nitrophenyl butyrate (PNPB) substrate. Following 30 min of incubation at 25 °C, the absorbance of the released p-nitrophenol was measured at 405 nm using a microplate reader. The inhibitory activity was calculated using the following formula:

where A

1, A

2, A

3, and A

4 correspond to the absorbance of the blank control, blank background control, sample measurement, and sample background control, respectively. All assays were carried out with three independent replicates.

2. Inhibition of pancreatic lipase

The inhibitory effect of FDOP and DDOP on PL activity was determined based on the method described by Chang et al. [

29]. The reaction was performed in 50 mmol/L phosphate buffer (pH 8.0). Each assay mixture contained 100 µL of polysaccharide sample, 100 µL of buffer, and 100 µL of PL solution (10 mg/mL in the same buffer). After pre-incubation at 37 °C for 10 min, the reaction was initiated by adding 100 µL of substrate solution (0.5 mmol/L 4-nitrophenyl laurate) and continued for 20 min at 37 °C. The release of 4-nitrophenol was monitored by measuring the increase in absorbance at 405 nm. The inhibition rate was calculated as follows:

A1 denotes the absorbance of the blank control, A2 represents the absorbance of the blank background control, A3 is the absorbance of the sample well, and A4 corresponds to the absorbance of the sample background control. Each experiment was conducted in triplicate.

2.13. Statistical Analysis

All data were expressed as mean ± SD, analyzed by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) using SPSS 26.0, and plotted using OriginPro 2021, Prism, and MestReNova software.

3. Results and Discussion

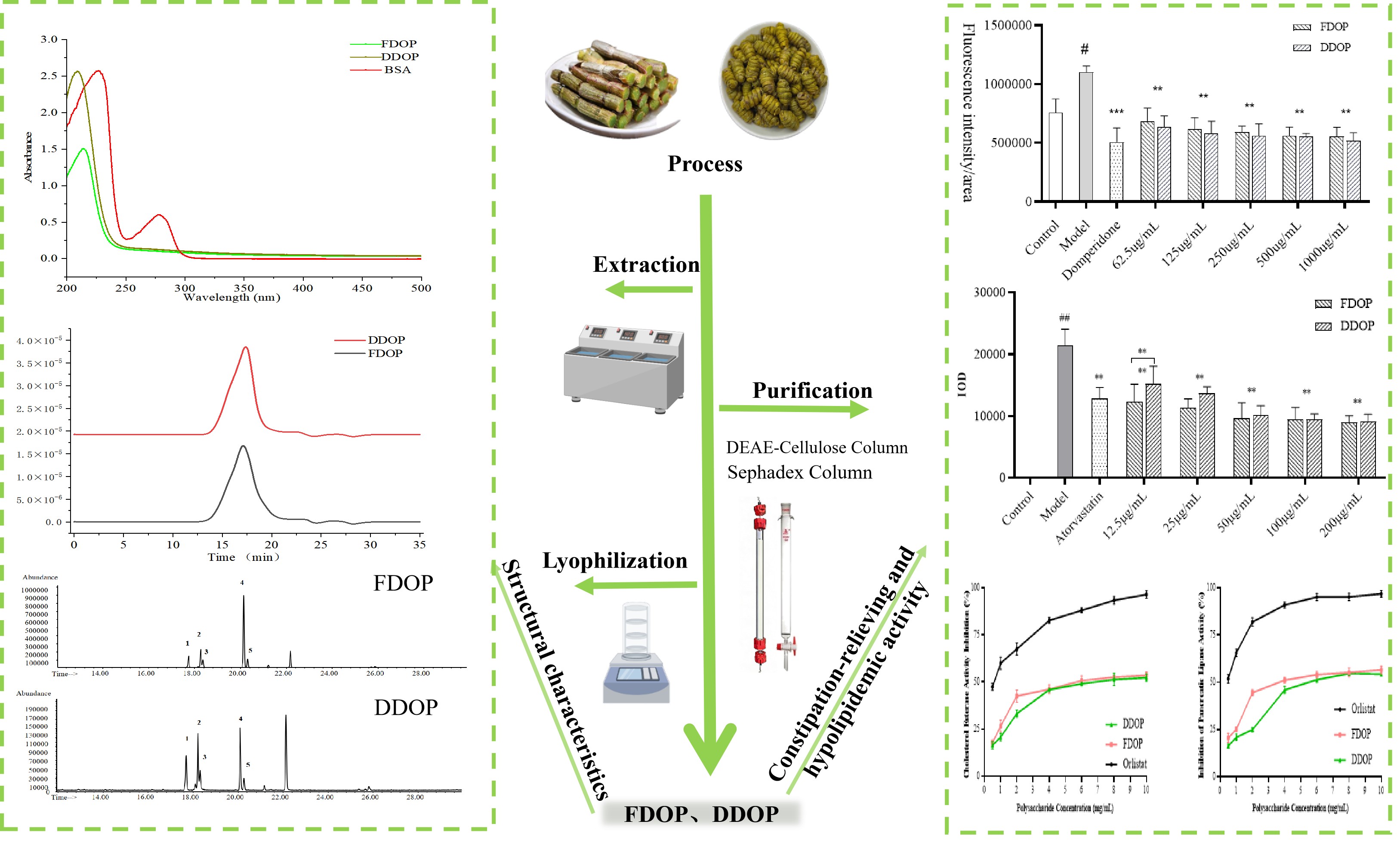

3.1. Isolation and Purification of Polysaccharides

The polysaccharides, designated as FDOP and DDOP, were sequentially purified using DEAE-52 cellulose anion exchange chromatography and Sephadex G-150 gel filtration. The extraction yields of the crude polysaccharides were 18.74% for FDOP and 15.52% for DDOP, suggesting potential compositional or structural differences between the two source materials. Following dissolution in distilled water, the crude extracts were fractionated on a DEAE-52 cellulose column, yielding distinct elution profiles as shown in

Figure 1A,B. To further enhance purity and homogeneity, the collected fractions were subjected to size-exclusion chromatography on a Sephadex G-150 column. The corresponding elution curves (

Figure 1D,E) displayed symmetrical single peaks, confirming the successful isolation of homogeneous polysaccharide fractions. Final purity, as determined by the phenol-sulfuric acid method, reached 89.4% ± 0.13% for FDOP and 84.5% ± 0.23% for DDOP, indicating high recovery and effective removal of non-polysaccharide impurities. Uronic acid content, quantified via the m-hydroxybiphenyl method, was measured at 2.54% for FDOP and 1.56% for DDOP. The consistently higher polysaccharide yield, purity, and uronic acid content in FDOP compared to DDOP suggest that FDOP may possess a more preserved or structurally distinct polysaccharide fraction. These compositional differences could contribute to variations in bioactivity, warranting further structural and functional characterization.

3.2. UV Analysis

Proteins and nucleic acids exhibit characteristic ultraviolet absorption at specific wavelengths, making UV spectroscopy a valuable method for detecting these impurities in polysaccharide samples. As shown in the full-wavelength UV scan (

Figure 1C), neither FDOP nor DDOP displayed absorption peaks at 260 nm or 280 nm, indicating the absence of common UV-absorbing contaminants such as proteins and nucleic acids. This result confirms the effectiveness of the purification steps applied and is consistent with reports on similar Dendrobium polysaccharides. It should be noted, however, that UV spectroscopy only detects impurities with characteristic chromophores. Therefore, sample homogeneity should be comprehensively assessed together with other analytical data, such as the single symmetric peak observed in gel chromatography.

3.3. Molecular Weight Analysis

The HPSEC-MALLS-RI analysis (

Figure 1F) revealed that both FDOP and DDOP exhibited a single symmetrical peak in the refractive index (RI) signal, confirming the homogeneity of the purified polysaccharides. Their weight-average molecular weights were determined to be 187.1 kDa for FDOP and 125.1 kDa for DDOP. This notable difference is likely attributable to the distinct processing histories of their source materials. FDOP was extracted from fresh Dendrobium stems, while DDOP was obtained from the processed product Fengdou. Traditional Fengdou processing involves steps such as hot-scalding, twisting, and drying. The associated high-temperature and high-humidity conditions may induce hydrolysis and cleavage of glycosidic bonds in the polysaccharide chains, thereby directly reducing the average molecular weight, as observed in DDOP [

30]. The narrow molecular weight distribution further supports the high purity of both samples despite their size disparity.

3.4. FT-IR Analysis

The FT-IR spectra are shown in

Figure 1G,H. The infrared spectra of both FDOP and DDOP exhibited numerous distinctive absorption peaks typical of polysaccharides within the range of 4000-400 cm-1. A prominent absorption peak was observed around 3400 cm-1 for both FDOP and DDOP, corresponding to the O-H stretching vibration in the sugar residues. The presence of absorption peaks at 2933.50 cm-1 and 2892.12 cm-1 for FDOP and 2924.93 cm-1 and 2893.44 cm-1 for DDOP were asymmetric C-H stretching vibrations of sugars and may contain -CH2 or -CH3 [

31]. In addition, the presence of the -O-acetyl structure was detected in the infrared spectra of the two sugars, with absorption peaks around 1735 cm-1, 1380 cm-1, and 1250 cm-1 attributed to the stretching vibration absorption peaks of C=O, C-H, and C-O, respectively, in the -O-COCH3 structure. Attributed to C=O and C=H stretching vibrations near 1640 cm-1 and 1420 cm-1 [

32]. The absorption peaks appearing around 1250 cm-1 are due to stretching and bending vibrations of the hydroxyl O-H, while those around 1060 and 1030 cm-1 indicate the presence of a pyran-type sugar ring. The absorption bands near 810 and 870 cm-1 were caused by intraring stretching vibrations and C2-H bond deformation vibrations of the mannopyranose ring [

33]. Overall, the FT-IR spectra of FDOP and DDOP were highly similar, indicating that both polysaccharides share comparable functional groups and contain O-acetylated pyranosyl structures.

3.5. SEM

The surface morphologies of FDOP and DDOP were examined at 500× magnification, revealing considerable differences between the two polysaccharides. As shown in

Figure 1I, FDOP appeared as irregular flakes with a loose structure, consisting of small, smooth spherical particles and rod-like elements attached to fragmented flake assemblies. In contrast, DDOP exhibited a rougher surface with subtle bead-like textures and distinct corrugated folds, morphological features that may be attributed to processing-induced alterations.

3.6. Analysis of Monosaccharide Composition

The ion chromatography analysis results of the monosaccharide composition of the two polysaccharide fractions of DO are shown in

Figure 1J. Both polysaccharides consisted predominantly of mannose and glucose, with other monosaccharides present only at trace levels that could not be accurately quantified, which was basically consistent with the study of Luo et al. [

33]. The molar ratios were 79.8:19.6 and 68.8:30.9, respectively. These results are consistent with the report by Zhang et al., which indicated that processing alters monosaccharide ratios, generally reducing mannose and increasing glucose content [

34].

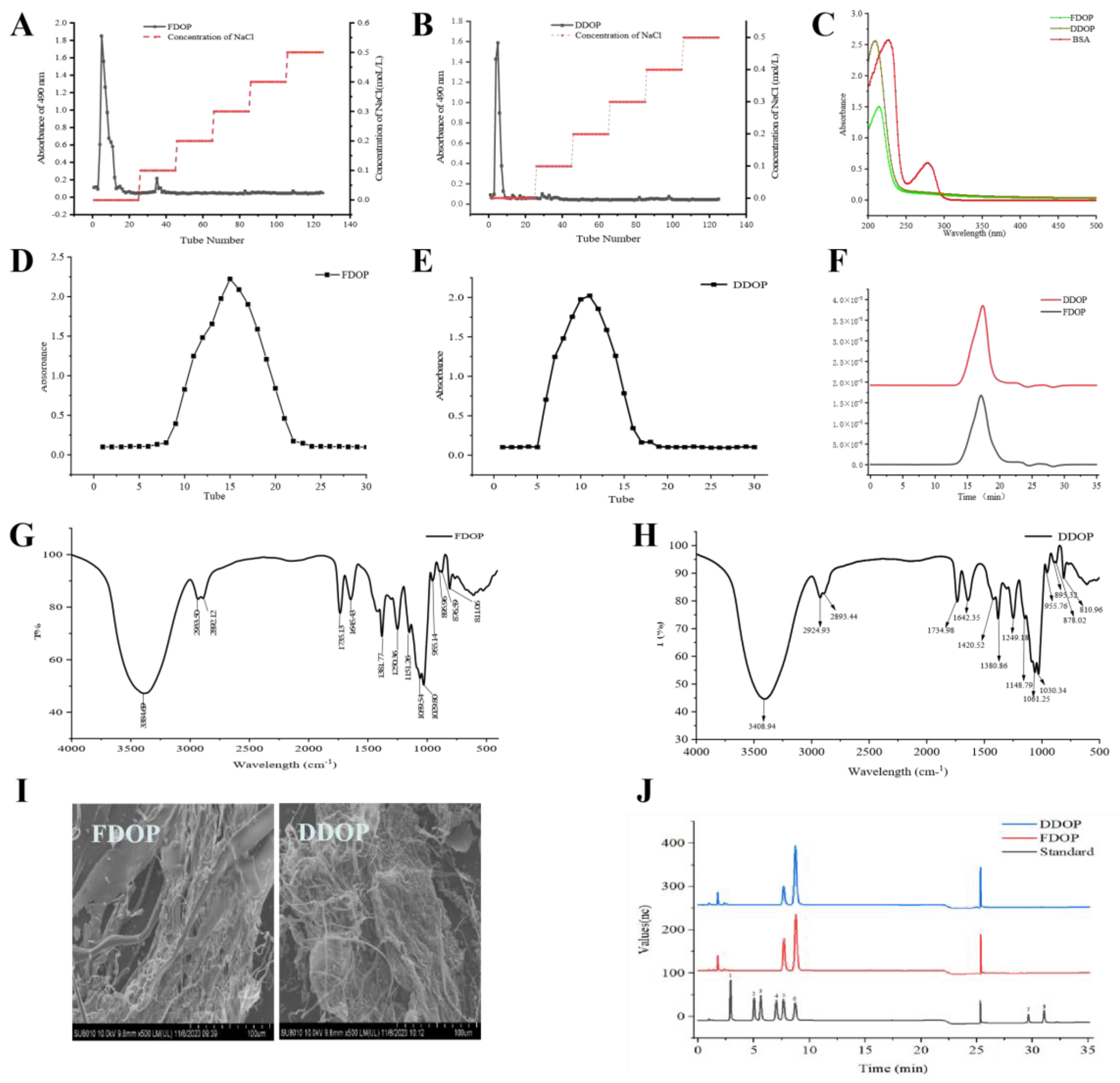

3.7. Methylation Analysis

Methylation analysis was employed to determine the glycosidic linkages and branching patterns of FDOP and DDOP. As shown in

Figure 2A, B, the predominant identified chain types were t-Glcp, 1,4-Glcp, 1,4-Manp, 1,4-Glcp (3-O-Ac), and 1,4-Manp (3-O-Ac), with their corresponding partial methylation patterns illustrated in

Figure 2C–E [

35]. Typically, partially methylated alditol acetates (PMAAs) with higher molecular weight and a greater degree of acetylation exhibit longer retention times [

36]. The PMAAs were identified by analyzing their retention times and characteristic fragment ions, as summarized in

Table 1. Notably, the hydroxyl group at the 4-position remained unacetylated during the derivatization process, likely due to steric hindrance or reaction selectivity, resulting in the formation of 1,5-diacetyl-2,3,6-tri-O-methyl-4-hydroxyhexanol rather than the fully methylated derivative [

37]. Based on the relative molar ratios of the individual aldol acetates and the analysis of the monosaccharides, it can be deduced that both FDOP and DDOP were mainly composed of 1,4-Glcp and 1,4-Manp, which aligns with findings from previous studies [

38,

39].

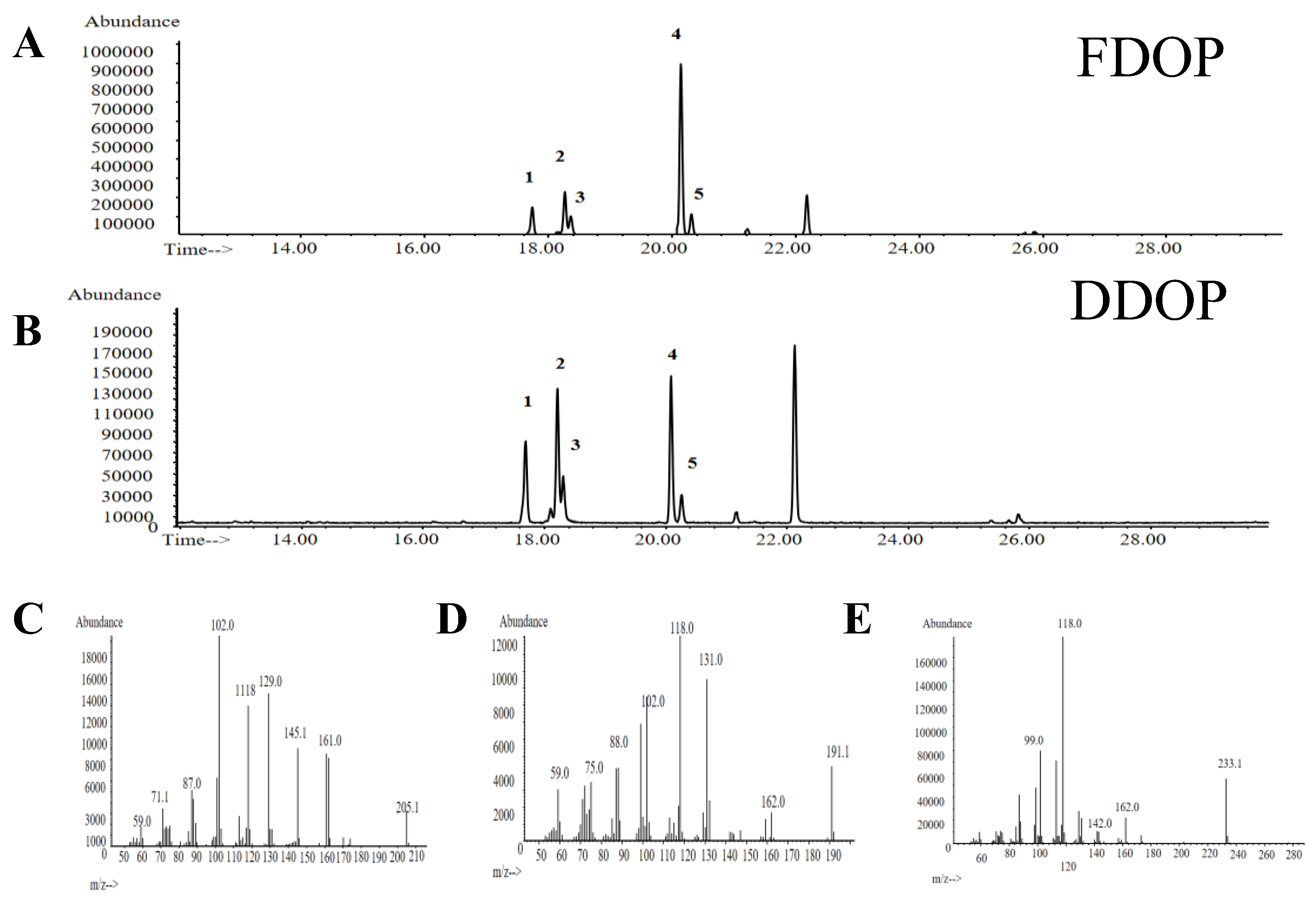

3.8. NMR Analysis

NMR spectroscopy was employed to elucidate the linkage patterns and glycosyl residues in FDOP and DDOP. In polysaccharides, the number and types of sugar residues can be inferred from the anomeric proton and carbon signals in the

1H and

13C NMR spectra [

40]. In the

1H NMR spectrum of FDOP, distinct anomeric proton signals were observed at δH 5.39, 5.39, 5.22, 4.73, 4.73, 4.65, and 4.51. Through analysis of the HSQC spectrum, these proton signals were correlated with anomeric carbon signals at δC 99.71, 99.71, 91.72, 100.08, 100.08, 96.95, and 102.44 in the

13C NMR spectrum, respectively. To facilitate the analysis and identification of sugar residues, the fragments were sequentially labeled as A through G. The

1H and

13C chemical shifts of each residue (A–G) were unambiguously assigned by combining 1D NMR (

1H,

13C;

Figure S2) with 2D NMR experiments, including HSQC, HMBC and

1H–

1H COSY (

Figure 3A–C) [

41,

42]. The corresponding chemical shift data are summarized in

Table S2. Based on the combined results of monosaccharide composition, methylation analysis, and 1D/2D NMR data, the structure of FDOP was was elucidated to possess a backbone mainly composed of →4)-3-O-acetyl-α-D-Glcp-(1→, →4)-α-D-Manp-(1→, →4)-3-O-acetyl-β-D-Manp-(1→, →4)-β-D-Manp-(1→, and →4)-β-D-Glcp-(1→ residues (

Figure 4A) [

43,

44,

45].

In contrast, six anomeric proton signals at δH 5.41, 5.23, 4.76, 4.76, 4.65, and 4.53 were observed in the

1H NMR spectrum of DDOP, which correlated with carbon signals at δC 99.29, 91.73, 100.05, 100.05, 95.59, and 102.42, respectively. The corresponding sugar residues were labeled A–F according to decreasing proton chemical shift, and the detailed chemical shifts are listed in

Table S3. The

1H and

13C signals of each residue (A–F) were further assigned using

1H NMR and

13C NMR (

Figure S3), together with

1H–

1H COSY, HSQC, and HMBC spectra (

Figure 3d–f) [

42,

43]. Consequently, the backbone of DDOP was proposed to consist mainly of →4) -3-O-acetyl-α-D-Glcp-(1→, →4)-3-O-acetyl-β-D-Manp-(1→ and →4)-β-D-Manp-(1→residues, as illustrated in

Figure 4B [

42,

43,

44,

45].

A direct comparison of the NMR data highlights key structural differences between the two polysaccharides. FDOP presented seven anomeric proton signals, indicating a greater diversity of glycosyl residues in its backbone, which includes →4)-α-D-Manp-(1→ and →4)-β-D-Glcp-(1→ units not present in DDOP. In comparison, DDOP showed only six anomeric signals and a simpler backbone structure. This suggests that the traditional processing of fresh DO into Fengdou may induce partial cleavage and rearrangement of the polysaccharide chains, leading to the loss or reduction of specific α-D-Manp and β-D-Glcp segments, thereby simplifying the overall architecture in DDOP.

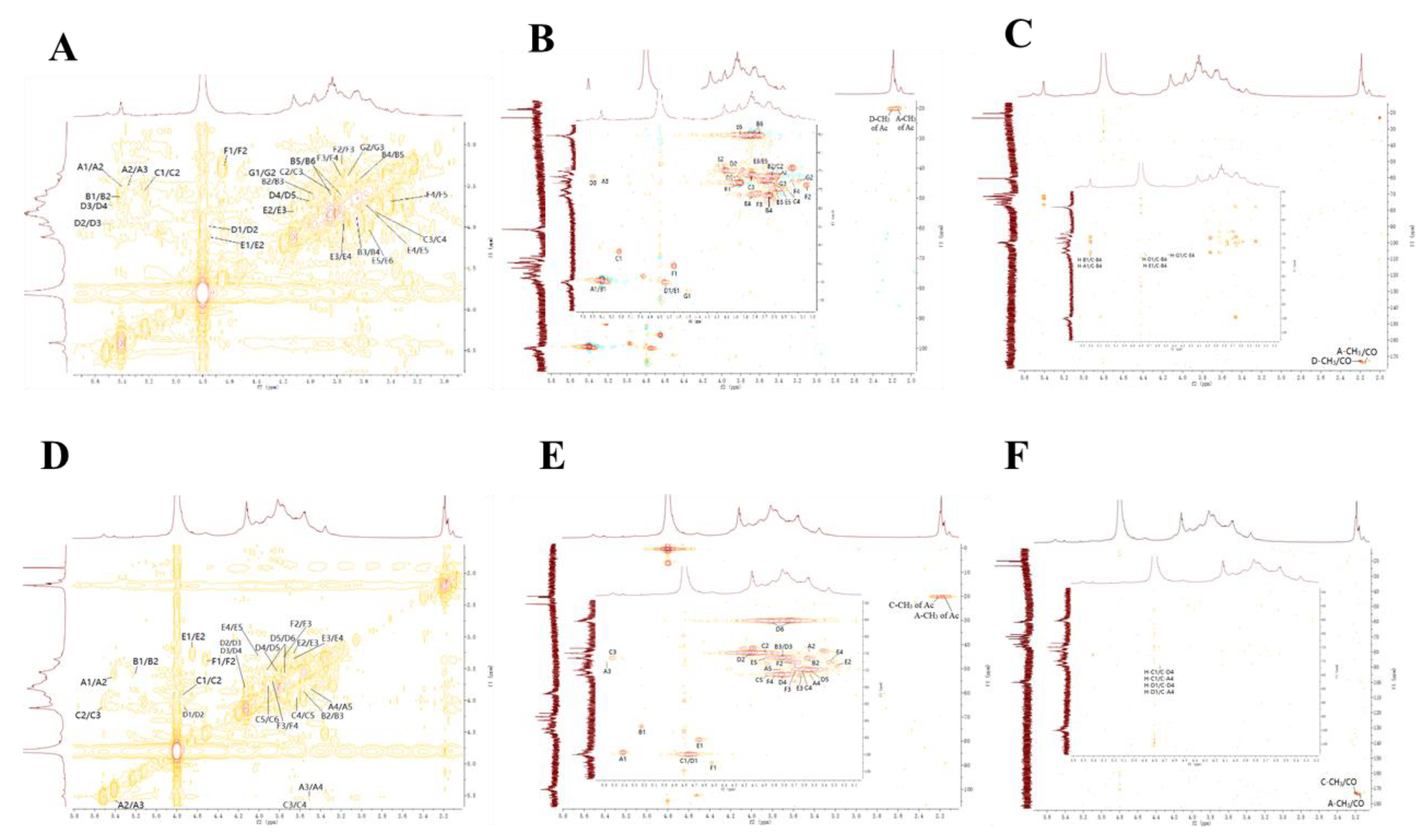

3.9. Evaluation of Constipation-Relieving Activity

The effects of FDOP and DDOP on the distribution of Nile Red in the zebrafish intestine are shown in

Figure 5. The intestinal fluorescence intensity in the model group was significantly higher than that in the blank group (p < 0.05), indicating that loperamide successfully induced constipation. In contrast, treatment with domperidone, polyethylene glycol, FDOP, or DDOP markedly reduced intestinal fluorescence compared with the model group (p < 0.01), demonstrating their ability to alleviate loperamide-induced constipation. Moreover, the intestinal fluorescence intensity gradually decreased with increasing doses of FDOP and DDOP, confirming that DO polysaccharides exert a concentration-dependent effect in relieving constipation and restoring intestinal motility. Notably, DDOP produced a stronger decrease in gut fluorescence than FDOP at the same concentrations, indicating the more superior efficacy of DDOP in alleviating constipation, may attributed to their distinct structural properties, which influence key physiological mechanisms.

Our structural analysis revealed critical differences between the two polysaccharides. FDOP possesses a higher mannose-to-glucose ratio and a more complex, high-molecular-weight backbone. In contrast, DDOP has a higher glucose content, a lower molecular weight, and a notably simplified backbone structure, likely be fermented by beneficial gut bacteria more easily, leading to increased production of short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) [

46,

47]. These fatty acids, in turn, increase stool volume and softness, stimulate intestinal peristalsis, and directly contribute to constipation relief. In addition, the higher glucose content in DDOP likely enhances its capacity to sequester bile acids. This sequestration not only reduces bile acid reabsorption but also stimulates colonic secretion and motility, thereby providing an additional mechanism for constipation relief [

48,

49,

50]. Taken together, the combined effects of lower molecular weight, a simplified backbone architecture and higher glucose content provide a reasonable explanation for why DDOP exhibits more pronounced constipation-relieving activity than FDOP, providing new insight and potential strategies for the use of DO-derived polysaccharides in constipation management.

3.10. Evaluation of Hypolipidemic Activity

3.10.1. In Vivo Lipid-Lowering Activity Test

The inhibitory effects of FDOP and DDOP on lipid accumulation were evaluated in a zebrafish hyperlipidemia model using Oil Red O staining (

Figure 6A–H). Larvae fed a high-fat diet containing egg yolk powder for 48 h exhibited marked lipid deposition in the caudal vasculature and abdominal region, whereas almost no staining was observed in the blank group. Quantitative analysis showed that the integrated optical density (IOD) of the model group was significantly higher than that of the blank group (p < 0.01), confirming the successful establishment of the hyperlipidemic model. Treatment with graded concentrations of FDOP and DDOP significantly reduced the IOD values relative to the model group (p < 0.01), indicating a clear dose-dependent inhibition of lipid accumulation. At the lowest tested concentration (12.5 μg/mL), FDOP produced a stronger lipid-lowering effect than DDOP (p < 0.05). However, when the concentration reached 100 μg/mL, the hypolipidemic activities of FDOP and DDOP were essentially comparable.

3.10.2. In Vitro Activity Assay

PCE is a crucial digestive enzyme responsible for hydrolyzing a variety of lipid substrates and is closely associated with the development of hyperlipidaemia. Therefore, inhibiting enzyme activity is regarded as a potential strategy for preventing dietary cholesterol absorption [

51]. As shown in

Figure 6J,K, both FDOP and DDOP exhibited concentration-dependent inhibition of PCE and PL within the range of 0.5–6.0 mg/mL. Beyond 6.0 mg/mL, no further significant increase in inhibition was observed, suggesting that the enzyme systems were approaching saturation. These findings corroborate earlier reports on the lipid-lowering activity of DO polysaccharides, which include inhibition of PCE and PL, reduction of lipid accumulation in zebrafish, and amelioration of dyslipidaemia in diabetic rats [

52].

The half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC

50) values further quantified the differential efficacy of the two polysaccharides. FDOP exhibited lower IC

50 values against both PCE (5.9 mg/mL) and PL (4.7 mg/mL) compared to DDOP (6.8 and 6.5 mg/mL, respectively), confirming its stronger direct inhibitory effect on these key digestive enzymes. This superior activity is consistent with the distinct structural profile of FDOP, characterized by its higher molecular weight, greater mannose content and more complex backbone architecture. Wang et al. indicated that polysaccharides with higher molecular weight have a longer retention time in the intestinal tract and are able to bind with lipids such as cholesterol and excrete them from the body, thus lowering blood lipid levels [

53] Concurrently, the enriched mannose component may contribute specific bioactivity. For example, Huang et al. reported that two mannose-rich polysaccharides from Cordyceps militaris (IPCM-2 and EPCM-2, containing 51.94% and 44.51% mannose, respectively) significantly improved blood lipid profiles in hyperlipidaemic mice [

54]. In addition, the more complex and extended backbone of FDOP may provide additional binding interfaces and stronger steric hindrance for interaction with pancreatic lipase and pancreatic cholesterol esterase, thereby enhancing enzyme inhibition. Taken together, the more potent enzyme-inhibitory and overall hypolipidaemic activity of FDOP arises from a synergistic combination of its structural attributes, elevated molecular weight, mannose enrichment, and a structurally diversified backbone. Optimizing these parameters, particularly molecular weight and mannose-rich backbone domains, may therefore represent a promising strategy for enhancing the lipid-lowering potential of DO-derived polysaccharides.

4. Conclusions

In this study, polysaccharides from fresh (FDOP) and their traditional processed product, Fengdou (DDOP), were isolated, structurally characterized, and comparatively evaluated for their gastrointestinal and lipid-regulating activities. Both polysaccharides were identified as mannose–glucose heteropolysaccharides; however, processing induced significant structural changes. FDOP exhibited a higher molecular weight, a higher mannose-to-glucose ratio, and a more structurally diversified linked backbone, whereas DDOP showed a lower molecular weight, increased glucose proportion, and a simplified backbone architecture.

Functionally, both FDOP and DDOP significantly alleviated loperamide-induced constipation and reduced lipid accumulation in zebrafish models, demonstrating dual regulatory effects on intestinal motility and lipid metabolism. DDOP exerted a more pronounced constipation-relieving effect, which is likely related to its lower molecular weight and simplified backbone that may favor solubility, microbial fermentation, and bile acid interaction in the gut. By contrast, FDOP displayed stronger inhibitory activity against pancreatic cholesterol esterase and pancreatic lipase, as well as superior hypolipidaemic efficacy. These effects are attributable to its higher molecular weight, enriched mannose content, and more complex →4-linked backbone, which collectively provide greater steric hindrance and binding capacity toward lipid-digesting enzymes.

Overall, these findings indicate that traditional processing of DO not only improves stability and storability, but also reshapes the structure-activity profile of its polysaccharides, differentiating FDOP and DDOP into functionally distinct yet complementary candidates for gut-metabolic modulation. The clarified relationships between structure and biological activity provide a useful rationale for the targeted design and optimization of DO-derived polysaccharides as natural ingredients for functional foods or adjuvant interventions aimed at constipation and dyslipidaemia.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on

Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Tingting Ding: Data curation, Writing-original draft, Formal analysis. Qingquan Ma: Writing-original draft, Visualization. Xin Xu: Data curation, Investigation. Caiyue Chen: Conceptualization, Supervision. Xiang Zou: Data curation, Software. Shuqi Gao: Software, Supervision. Tingting Zhang: Software. Ya Song: Data curation. Fengzhong Wang: Conceptualization, Supervision, Funding acquisition. Jing Sun: Conceptualization, Writing-review & editing, and Funding acquisition. Bei Fan: Investigation, Supervision, and Funding acquisition.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/

supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the National Key R&D Program of China (2022YFD1600303), Yunnan Major Science and Technology Special Project (202402AE090011), and the Mount Taishan Scholar Young Expert Program.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.:

References

- Bao, H.; Bao, H.; Wang, Y.; Wang, F.; Jiang, Q.; Li, H.; Ding, Y.; Zhu, C. Variations in cold resistance and contents of bioactive compounds among Dendrobium officinale Kimura et Migo Strains. Foods 2024, 13, 1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, P.; Fan, B.; Mu, Y.; Tong, L.; Lu, C.; Li, L.; Liu, J.; Sun, J.; Wang, F. Plant-Wide target metabolomics provides a novel interpretation of the changes in chemical components during Dendrobium officinale traditional processing. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 1995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, L.; Jiang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Niu, Z.; Xue, Q.; Liu, W.; Ding, X. The large single-copy (LSC) region functions as a highly effective and efficient molecular marker for accurate authentication of medicinal Dendrobium species. Acta Pharm Sin B 2020, 10, 1989–2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Z.; He, Z.; Dou, P.; Wang, K.; Zhang, Y. Study on the intestinal metabolism and absorption of polysaccharides from Dendrobium officinale. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 331, 148390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bu, Y.; Yin, B.; Qiu, Z.; Li, L.; Zhang, B.; Zheng, Z.; Li, M. Structural characterization and antioxidant activities of polysaccharides extracted from Polygonati rhizoma pomace. Food Chem X 2024, 23, 101778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, G.; Dong, H.; Liu, S.; Wu, W.; Yang, H. Comparative evaluation of the physiochemical properties, and antioxidant and hypoglycemic activities of Dendrobium officinale leaves processed using different drying techniques. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 1911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Yang, J.; Jin, H.; Gu, D.; Wang, Q.; Liu, Y.; Zan, K.; Fan, J.; Wang, R.; Wei, F.; Ma, S. Comparisons of physicochemical features and hepatoprotective potentials of unprocessed and processed polysaccharides from Polygonum multiflorum Thunb. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 235, 123901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, M.; Chang, C.; Chao, C.; Hsu, Y. Structural changes, and anti-inflammatory, anti-cancer potential of polysaccharides from multiple processing of Rehmannia glutinosa. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 206, 621–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Zhang, X.; Zhu, X.; Hua, Y. Chemical constituents, bioactivities, and pharmacological mechanisms of Dendrobium Officinale: A review of the past decade. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2023, 71, 14870–14889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Jin, H.; Dong, Y.; Wang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Wei, F. Structural characterization of Dendrobium huoshanense polysaccharides and its gastroprotective effect on acetic acid-induced gastric ulcer in mice. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 311, 143361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, H.; Xu, L.; Zhu, H.; Bu, T.; Li, Z.; Zhao, S.; Yang, K.; Sun, P.; Cai, M. Structural characterization of oligosaccharide from Dendrobium Officinale and its properties in vitro digestion and fecal fermentation. Food Chem. 2024, 460, 140511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, J.; Lin, Y.; Xie, H.; Farag, M.A.; Feng, S.; Li, J.; Shao, P. Dendrobium Officinale leaf polysaccharides ameliorated hyperglycemia and promoted gut bacterial associated SCFAs to alleviate type 2 diabetes in adult mice. Food Chem X 2022, 13, 100207. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, H.; He, S.; Xiong, Z.; Su, J.; Wang, Y.; Zheng, B.; Zhang, Y. Gut microbiota-metabolic axis insight into the hyperlipidemic effect of lotus seed resistant starch in hyperlipidemic mice. Carbohydr. Polym. 2023, 314, 120939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, R.; Xu, S.; Li, B.; Zhang, B.; Chen, W.; Dai, D.; Liu, Z. Gut indigenous Ruminococcus gnavus alleviates constipation and stress-related behaviors in mice with loperamide-induced constipation. Food Funct. 2023, 14, 5702–5715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Chen, J.; Gao, M.; Ouyang, Z.; Li, Y.; Liu, D.; Zhu, M.; Sun, H.; Wang, J.; Chen, J.; et al. Research progress on the mechanism of action and screening methods of probiotics for lowering blood lipid levels. Foods 2025, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, F.; Huang, J.; He, H.; Ju, X.; Ji, Y.; Deng, F.; Wang, Z.; He, R. Study on the hypolipidemic activity of rapeseed protein-derived peptides. Food Chem. 2023, 423, 136315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Xu, F.; Xia, Q.; Liu, K.; Lin, H.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, Y. The peptide lltragl derived from Rapana venosa exerts protective effect against inflammatory bowel disease in zebrafish model by regulating multi-pathways. Mar. Drugs 2024, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwiatkowska, I.; Hermanowicz, J.M.; Iwinska, Z.; Kowalczuk, K.; Iwanowska, J.; Pawlak, D. Zebrafish—An optimal model in experimental oncology. Molecules 2022, 27, 4223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lachowicz, J.; Szopa, A.; Ignatiuk, K.; Świąder, K.; Serefko, A. Zebrafish as an animal model in cannabinoid research. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 10455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Li, W.; Li, S.; Zhu, S.; Pan, F.; Gu, Q.; Song, D. Hypolipidemic effect of polysaccharide from Sargassum fusiforme and its ultrasonic degraded polysaccharide on zebrafish fed high-fat diet. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 276, 133771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Huang, Y.; Long, F.; Yang, D.; Huang, Y.; Han, Y.; Wu, Y.; Zhong, K.; Bu, Q.; Gao, H.; Huang, Y. Insight into structural characteristics of theabrownin from Pingwu Fuzhuan brick tea and its hypolipidemic activity based on the in vivo zebrafish and in vitro lipid digestion and absorption models. Food Chem. 2023, 404, 134382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, W.; Tao, W.; Wang, M.; Liu, W.; Xing, J.; Yang, Y. Dendrobium Officinale Xianhu 2 polysaccharide helps forming a healthy gut microbiota and improving host immune system: An in vitro and in vivo study. Food Chem. 2023, 401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Huo, Y.; Xu, L.; Xu, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhou, T. Purification, characterization and antioxidant activity of polysaccharides from Porphyra haitanensis. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 165, 2116–2125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, T.; Wu, Z.; Li, M.; Cao, B.; Li, J.; Jiang, J.; Liu, H.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, S. TCP80-1, a new levan-neoseries fructan from Tupistra chinensis baker rhizomes alleviates ulcerative colitis induced by dextran sulfate sodium in Drosophila melanogaster model. Food Res. Int. 2025, 203, 115860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.; Xing, N.; Jiao, Y.; Li, J.; Wang, T.; Zhang, Q.; Hu, X.; Li, C.; Kuang, W. An arabinan from Citrus Grandis fruits alleviates ischemia/reperfusion-induced myocardial cell apoptosis via the nrf2/keap1 and ire1/grp78 signaling pathways. Carbohydr. Polym. 2025, 347, 122728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Yi, H.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, L. Screening of intestinal peristalsis-promoting probiotics based on a zebrafish model. Food Funct. 2019, 10, 2075–2082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Zhong, K.; Bai, J.-R.; Wu, Y.-P.; Zhang, J.-Q.; Gao, H. The biochemical characteristics of a novel fermented loose tea by Eurotium cristatum (MF800948) and its hypolipidemic activity in a zebrafish model. LWT-Food SCI Technol. 2020, 117, 108629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, X.; Hu, X.; Xiang, H.; Chen, S.; Li, L.; Qi, B.; Li, C.; Liu, S.; Yang, X. Structural characterization and hypolipidemic activity of Gracilaria Lemaneiformis polysaccharide and its degradation products. Food Chem X 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, S.; Lei, X.; Xie, Q.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, Y.; Xi, J.; Duan, J.; Ge, J.; Nian, F. In vitro study on antioxidant and lipid-lowering activities of tobacco polysaccharides. Bioresour. Bioprocessing 2024, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goudar, G.; Sharma, P.; Janghu, S.; Longvah, T. Effect of processing on barley β-glucan content, its molecular weight and extractability. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 162, 1204–1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, M.; Zhu, H.; Xu, L.; Wang, J.; Xu, J.; Li, Z.; Yang, K.; Wu, J.; Sun, P. structure, anti-fatigue activity and regulation on gut microflora in vivo of ethanol-fractional polysaccharides from Dendrobium Officinale. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 234, 123572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuang, M.-T.; Li, J.-Y.; Yang, X.-B.; Yang, L.; Xu, J.-Y.; Yan, S.; Lv, Y.-F.; Ren, F.-C.; Hu, J.-M.; Zhou, J. Structural characterization and hypoglycemic effect via stimulating glucagon-like peptide-1 secretion of two polysaccharides from Dendrobium Officinale. Carbohydr. Polym. 2020, 241, 116326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, Q.; Tang, Z.; Zhang, X.; Zhong, Y.; Yao, S.; Wang, L.; Lin, C.; Luo, X. Chemical properties and antioxidant activity of a water-soluble polysaccharide from Dendrobium Officinale. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2016, 89, 219–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, W.; Liu, X.; Sun, X.; Han, R.; Yu, N.; Liang, J.; Zhou, A. Comparison of the antioxidant activities and polysaccharide characterization of fresh and dry Dendrobium Officinale Kimura et Migo. Molecules 2022, 27, 6654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sims, I.M.; Carnachan, S.M.; Bell, T.J.; Hinkley, S.F.R. Methylation analysis of polysaccharides: Technical Advice. Carbohydr. Polym. 2018, 188, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, J.; Huang, Y.; Zhu, X.; Zhou, F.; Wu, T.; Jia, J.; Liu, X.; Kuang, H.; Xia, Y. Structural identification, rheological properties and immunological receptor of a complex galacturonoglucan from fruits of Schisandra chinensis (Turcz.) Baill. Carbohydr. Polym. 2024, 346, 122644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciucanu, I.; Kerek, F. A simple and rapid method for the permethylation of carbohydrates. Carbohydrate Research 1984, 131, 209–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Yi, X.; Jia, S.; Liu, C.; Han, Z.; Han, B.; Jiang, G.; Ding, Z.; Wang, R.; Lv, G. Optimization of three extraction methods and their effect on the structure and antioxidant activity of polysaccharides in Dendrobium huoshanense. Molecules 2023, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Zhang, H.; Fan, J.; Jia, S.; Yi, X.; Han, Z.; Wang, R.; Qiu, H.; Lv, G. Study on differences in structure and anti-inflammatory activity of polysaccharides in five species of Dendrobium. Polymers 2025, 17, 1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Li, L.; Chang, H.; Cai, B.; Gao, H.; Chen, G.; Hou, W.; Jappar, Z.; Yan, Y. Research progress on extraction, purification, structure and biological activity of Dendrobium officinale polysaccharides. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butt, H.S.; Ulriksen, E.S.; Rise, F.; Wangensteen, H.; Duus, J.Ø.; Inngjerdingen, M.; Inngjerdingen, K.T. Structural elucidation of novel pro-inflammatory polysaccharides from Daphne mezereum L. Carbohydr. Polym. 2024, 324, 121554. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, F.; Chen, W.; He, P.; Zhan, Q.; Wang, Q.; Wu, H.; Zhang, M. Structural characterization of polysaccharides with potential antioxidant and immunomodulatory activities from Chinese water chestnut peels. Carbohydr. Polym. 2020, 246, 116551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bi, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Hu, J.; Ding, J.; Yang, P.; Liu, Y.; Lu, Y.; Jin, Y.; Tang, H.; Liu, Y.; et al. A Novel Polysaccharide from Lonicerae Japonicae Caulis: Characterization and Effects on the Function of Fibroblast-like Synoviocytes. Carbohydr. Polym. 2022, 292, 119674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Cheong, K.L.; Song, Z.; Shi, Y.; Huang, X. Structure and protective effect on UVB-induced keratinocyte damage of fructan from white garlic. Carbohydr. Polym. 2013, 92, 200–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, G.; Li, J.; Zhang, J.; Liu, H.; Ye, Q.; Wang, Z. Structural characterization and antitumor activity of a polysaccharide from Dendrobium wardianum. Carbohydr. Polym. 2021, 269, 118253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Huang, Z.; Xue, X.; Luo, X.; Guo, Z.; Miao, S.; Zheng, B. Effect of fucoidan molecular weight on gut microbiota composition and anti-inflammatory activity after in vitro dynamic digestion and fermentation. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 330, 147976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, X.; Xv, W.; Fu, S.; Li, S.; Fu, X.; Tan, C.; Wang, P.; Dou, Z.; Chen, C. The effect of the molecular weight of blackberry polysaccharides on gut microbiota modulation and hypoglycemic effect in vivo. Food Funct. 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Q.; Liang, J.; Liu, H. In Vitro Effects of four polysaccharides containing β-D-Glup on intestinal function. Int. J. Food Prop. 2019, 22, 1064–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.W.; Siesel, A.E. Hypocholesterolemic effects of oat products. ADV EXP MED BIOL. 1990, 270, 17–36. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, J.; Nie, S.; Li, J.; Li, C.; Cui, S.W.; Xie, M. Mechanism of interactions between calcium and viscous polysaccharide from the seeds of Plantago asiatica L. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2012, 60, 7981–7987. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, H.; Wang, J.; Ao, J.; Ye, L.; Shi, Y.; Liu, Y.; Li, M.; Luo, A. The inhibitory mechanism of pentacyclic triterpenoid acids on pancreatic lipase and cholesterol esterase. Food Bioscience 2023, 51, 102341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Nie, Q.; Hu, J.; Huang, X.; Huang, W.; Nie, S. Metabolism amelioration of Dendrobium Officinale polysaccharide on type II diabetic rats. Food Hydrocoll. 2020, 102, 105582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Zang, X.; Yang, Y.; Wang, W.; Zhang, J.; Que, Y.; Liang, F.; Wang, T.; Zhang, J.; Ma, H.; Guan, L. Physicochemical properties and fermentation characteristics of a novel polysaccharide degraded from Flammulina velutipes residues polysaccharide. Food Chem X 2024, 24, 102049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, S.; Wang, Y.; Jiang, X. Structural characterization of polysaccharides from Cordyceps militaris and their hypolipidemic effects in high fat diet fed mice. RSC Adv. 2018, 8, 41012–41022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

DEAE-52 elution curve of FDOP and DDOP (A,B); Elution curve of Sephadex G150 of FDOP and DDOP (D,E); The molecular weight distribution of FDOP and DDOP (F); UV–vis spectrum of FDOP and DDOP (C); FT-IR spectrum of FDOP and DDOP (G,H); SEM images of FDOP and DDOP (500×) (I); IC spectra of monosaccharide standards, Monosaccharide composition of FDOP and DDOP (J); 1-Fuc, 2-Rha, 3-Ara, 4-Gal, 5-Glc, 6-Man, 7-GalA, 8-GlcA.

Figure 1.

DEAE-52 elution curve of FDOP and DDOP (A,B); Elution curve of Sephadex G150 of FDOP and DDOP (D,E); The molecular weight distribution of FDOP and DDOP (F); UV–vis spectrum of FDOP and DDOP (C); FT-IR spectrum of FDOP and DDOP (G,H); SEM images of FDOP and DDOP (500×) (I); IC spectra of monosaccharide standards, Monosaccharide composition of FDOP and DDOP (J); 1-Fuc, 2-Rha, 3-Ara, 4-Gal, 5-Glc, 6-Man, 7-GalA, 8-GlcA.

Figure 2.

The methylation analysis of FDOP (A) and DDOP (B); Mass spectra of Peak 1 (C), Peak 2 and 3 (D), and Peak 4 and 5 (E).

Figure 2.

The methylation analysis of FDOP (A) and DDOP (B); Mass spectra of Peak 1 (C), Peak 2 and 3 (D), and Peak 4 and 5 (E).

Figure 3.

The COSY (A, D), HSQC (B, E), HMBC (C, F) of FDOP and DDOP, respectively.

Figure 3.

The COSY (A, D), HSQC (B, E), HMBC (C, F) of FDOP and DDOP, respectively.

Figure 4.

The prediction structure repetition unit spectra of FDOP (A) and DDOP (B), respectively.

Figure 4.

The prediction structure repetition unit spectra of FDOP (A) and DDOP (B), respectively.

Figure 5.

Results of relieving constipation activities in different groups of zebrafish. Control (A), Model (B), Domeperidone (C), FDOP: 125, 250, 500, 1000, 2000 µg/mL (D-H), DDOP: 125, 250, 500, 1000, 2000 µg/mL (I-M), fluorescence intensity of FDOP and DDOP (N).

Figure 5.

Results of relieving constipation activities in different groups of zebrafish. Control (A), Model (B), Domeperidone (C), FDOP: 125, 250, 500, 1000, 2000 µg/mL (D-H), DDOP: 125, 250, 500, 1000, 2000 µg/mL (I-M), fluorescence intensity of FDOP and DDOP (N).

Figure 6.

Results of hypolipidemic activities in different groups of zebrafish. Lipid accumulation levels in control (A), model (B), atorvastatin (C), 12.5, 25, 50, 100, 200 µg/mL of FDOP and DDOP (D-H), Integral optical density (IOD) of FDOP and DDOP (I); Pancreatic cholesterol esterase inhibition rate (J); Pancreatic lipase inhibition rate (K).

Figure 6.

Results of hypolipidemic activities in different groups of zebrafish. Lipid accumulation levels in control (A), model (B), atorvastatin (C), 12.5, 25, 50, 100, 200 µg/mL of FDOP and DDOP (D-H), Integral optical density (IOD) of FDOP and DDOP (I); Pancreatic cholesterol esterase inhibition rate (J); Pancreatic lipase inhibition rate (K).

Table 1.

Linkage analysis of FDOP and DDOP by methylation and GC-MS.

Table 1.

Linkage analysis of FDOP and DDOP by methylation and GC-MS.

| No. |

Methylation debris |

Majorfragments (m/z)

|

Types of linkages |

Molecular ratio % |

| FDOP |

DDOP |

| 1 |

1,5-di-O-acetyl-(1-deuterio)-2,3,4,6-tetra-O-methyl glucitol |

59.0,71.7,87.0,102.0,111.8,129.0,145.1,161.0,205.1 |

t-Glcp

|

11.1 |

20.9 |

| 2 |

1,5-tri-O-acetyl-(1-deuterio)-2,3,6-tri-O-methyl-4-hydroxyl-manitol |

59.0,75.0,88.0,102.0,118.0,131.0,162.0,191.1 |

1,4-Manp(3-O-Ac) |

15.9 |

30.3 |

| 3 |

1,5-tri-O-acetyl-(1-deuterio)-2,3,6-tri-O-methyl-4-hydroxyl-glcitol |

59.0,75.0,88.0,102.0,118.0,131.0,162.0,191.1 |

1,4-Glcp(3-O-Ac) |

7.9 |

11.7 |

| 4 |

1,4,5-tri-O-acetyl-(1-deuterio)-2,3,6-tri-O-methyl-manitol |

99.0,118.0,142.0,162.0,233.1 |

1,4-Manp

|

57.1 |

30.4 |

| 5 |

1,4,5-tri-O-acetyl-(1-deuterio)-2,3,6-tri-O-methyl-glucitol |

99.0,118.0,142.0,162.0,233.1 |

1,4-Glcp

|

8.1 |

6.7 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).