Submitted:

31 December 2025

Posted:

02 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

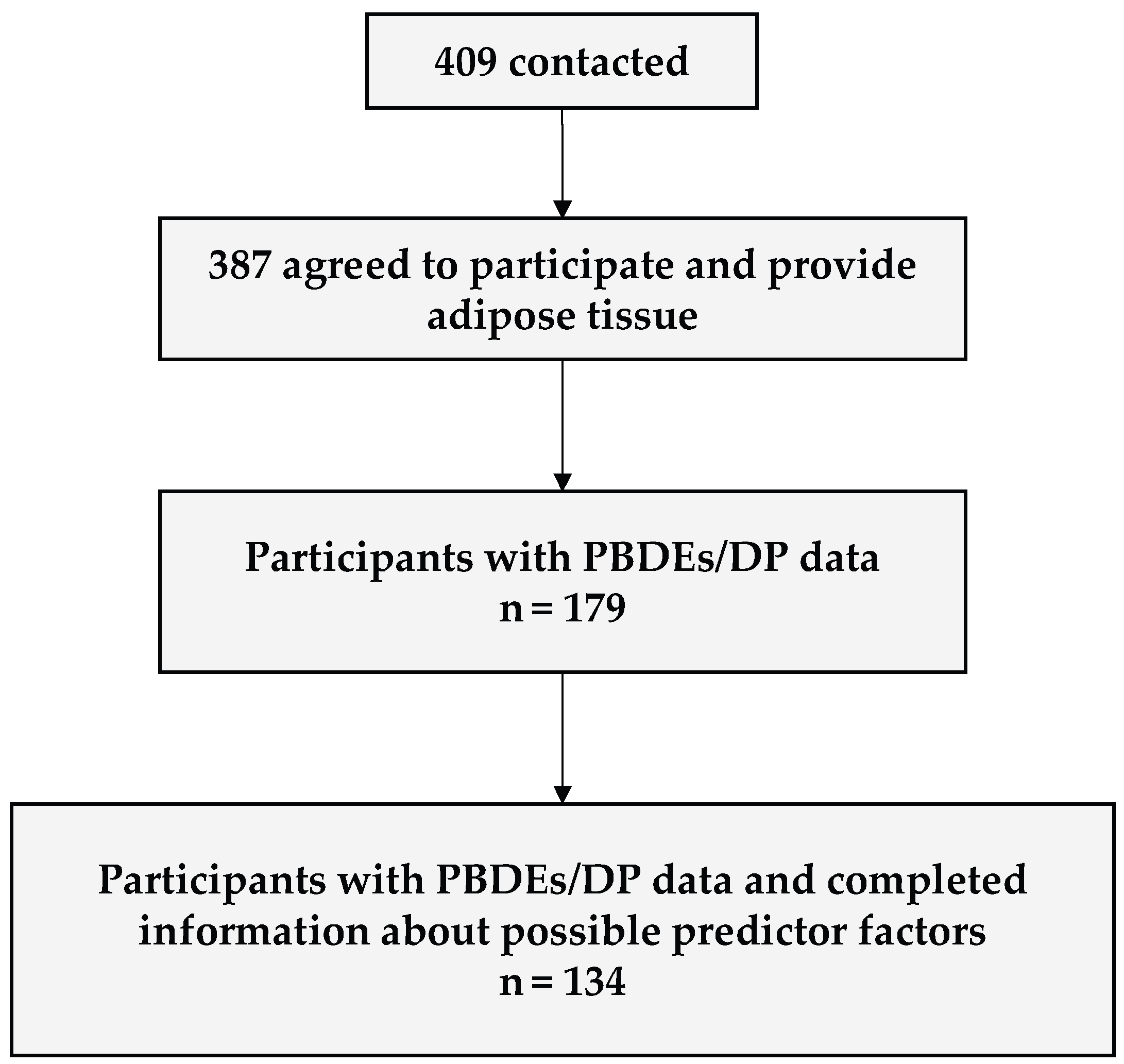

2.1. Study Design and Population

2.2. Laboratory Analyses

2.3. Sociodemographic, Lifestyle and Clinical Information

2.4. Statistical Analyses

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Description of the Study Population and Adipose Tissue Pollutant Concentrations

3.2. Factors Associated with Adipose Tissue PBDEs and DP Concentrations

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BDE | Bromodiphenyl ether |

| BIC | Bayesian information criterion |

| BMI | Body mass index |

| BTBPE | 1,3,5-tribromo-2-[2-(2,4,6-tribromophenoxy) ethoxy] benzene |

| CI | Confidence interval |

| DMC | Dichloromethane |

| DP | Dechlorane plus |

| EDC | Endocrine disruptor chemical |

| IQR | Interquartile range |

| LOQ | Limit of quantification |

| LVI | Large volume injection |

| MMI | Multimode inlet |

| PBDEs | Polibromodiphenyl ethers |

| POPs | Persistent organic pollutants |

| SD | Standard deviation |

| SNHS | Spanish National Health Survey |

| SIM | Selected ion monitoring |

| β | Beta coefficient |

References

- González-Casanova, J.E.; Pertuz-Cruz, S.L.; Caicedo-Ortega, N.H.; Rojas-Gomez, D.M. Adipogenesis Regulation and Endocrine Disruptors: Emerging Insights in Obesity. BioMed Res. Int. 2020, 2020, 7453786. [CrossRef]

- Mrema, E.J.; Rubino, F.M.; Brambilla, G.; Moretto, A.; Tsatsakis, A.M.; Colosio, C. Persistent Organochlorinated Pesticides and Mechanisms of Their Toxicity. Toxicology 2013, 307, 74–88. [CrossRef]

- Yilmaz, B.; Terekeci, H.; Sandal, S.; Kelestimur, F. Endocrine Disrupting Chemicals: Exposure, Effects on Human Health, Mechanism of Action, Models for Testing and Strategies for Prevention. Rev. Endocr. Metab. Disord. 2020, 21, 127–147. [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Yin, Q.; Xu, L.; Hua, M.; Zhang, Z.; Xu, Y.; Xia, W.; Qian, H.; Hong, J.; Jin, J. Serum Polybrominated Diphenyl Ether Exposure and Influence Factors in Blood Donors of Wuxi Adults from 2013 to 2016. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 63932–63940. [CrossRef]

- Ding, G.; Yu, J.; Cui, C.; Chen, L.; Gao, Y.; Wang, C.; Zhou, Y.; Tian, Y. Association between Prenatal Exposure to Polybrominated Diphenyl Ethers and Young Children’s Neurodevelopment in China. Environ. Res. 2015, 142, 104–111. [CrossRef]

- Zafar, M.I.; Kali, S.; Ali, M.; Riaz, M.A.; Naz, T.; Iqbal, M.M.; Masood, N.; Munawar, K.; Jan, B.; Ahmed, S.; et al. Dechlorane Plus as an Emerging Environmental Pollutant in Asia: A Review. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 42369–42389. [CrossRef]

- Shaw, S.D.; Harris, J.H.; Berger, M.L.; Subedi, B.; Kannan, K. Brominated Flame Retardants and Their Replacements in Food Packaging and Household Products: Uses, Human Exposure, and Health Effects. In Toxicants in Food Packaging and Household Plastics; Snedeker, S.M., Ed.; Molecular and Integrative Toxicology; Springer London: London, 2014; pp. 61–93 ISBN 978-1-4471-6499-9.

- McGrath, T.J.; Morrison, P.D.; Ball, A.S.; Clarke, B.O. Concentrations of Legacy and Novel Brominated Flame Retardants in Indoor Dust in Melbourne, Australia: An Assessment of Human Exposure. Environ. Int. 2018, 113, 191–201. [CrossRef]

- Chain (CONTAM), E.P. on C. in the F. Scientific Opinion on Polybrominated Diphenyl Ethers (PBDEs) in Food. EFSA J. 2011, 9, 2156. [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Liu, B.; Yu, Y.; Li, H.; Li, Q.; Cui, Y.; Ma, Y. Polybrominated Diphenyl Ethers (PBDEs) in Household Dust: A Systematic Review on Spatio-Temporal Distribution, Sources, and Health Risk Assessment. Chemosphere 2023, 314, 137641. [CrossRef]

- Brasseur, C.; Pirard, C.; Scholl, G.; De Pauw, E.; Viel, J.-F.; Shen, L.; Reiner, E.J.; Focant, J.-F. Levels of Dechloranes and Polybrominated Diphenyl Ethers (PBDEs) in Human Serum from France. Environ. Int. 2014, 65, 33–40. [CrossRef]

- Brasseur, C.; Pirard, C.; Scholl, G.; De Pauw, E.; Viel, J.-F.; Shen, L.; Reiner, E.J.; Focant, J.-F. Levels of Dechloranes and Polybrominated Diphenyl Ethers (PBDEs) in Human Serum from France. Environ. Int. 2014, 65, 33–40. [CrossRef]

- Sverko, E.; Tomy, G.T.; Reiner, E.J.; Li, Y.-F.; McCarry, B.E.; Arnot, J.A.; Law, R.J.; Hites, R.A. Dechlorane Plus and Related Compounds in the Environment: A Review. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2011, 45, 5088–5098. [CrossRef]

- Regulation (EU) 2019/1021 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 20 June 2019 on Persistent Organic Pollutants; 2019; Vol. 169;.

- Stockholm Convention Stockholm Convention on Persistent Organic Pollutants (POPs) 2023.

- van Der Schyff, V.; Kalina, J.; Govarts, E.; Gilles, L.; Schoeters, G.; Castaño, A.; Esteban-López, M.; Kohoutek, J.; Kukucka, P.; Covaci, A.; et al. Exposure to Flame Retardants in European Children - Results from the HBM4EU Aligned Studies. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 2023, 247. [CrossRef]

- Fromme, H.; Cequier, E.; Kim, J.-T.; Hanssen, L.; Hilger, B.; Thomsen, C.; Chang, Y.-S.; Völkel, W. Persistent and Emerging Pollutants in the Blood of German Adults: Occurrence of Dechloranes, Polychlorinated Naphthalenes, and Siloxanes. Environ. Int. 2015, 85, 292–298. [CrossRef]

- Gomes, J.; Begum, M.; Kumarathasan, P. Polybrominated Diphenyl Ether (PBDE) Exposure and Adverse Maternal and Infant Health Outcomes: Systematic Review. Chemosphere 2024, 347, 140367. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Zhao, L.; Guo, L. Dechloranes Exhibit Binding Potency and Activity to Thyroid Hormone Receptors. J. Environ. Sci. 2022, 112, 16–24. [CrossRef]

- Mortensen, Å.-K.; Verreault, J.; François, A.; Houde, M.; Giraudo, M.; Dam, M.; Jenssen, B.M. Flame Retardants and Their Associations with Thyroid Hormone-Related Variables in Northern Fulmars from the Faroe Islands. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 806, 150506. [CrossRef]

- Gascon, M.; Vrijheid, M.; Martínez, D.; Forns, J.; Grimalt, J.O.; Torrent, M.; Sunyer, J. Effects of Pre and Postnatal Exposure to Low Levels of Polybromodiphenyl Ethers on Neurodevelopment and Thyroid Hormone Levels at 4 Years of Age. Environ. Int. 2011, 37, 605–611. [CrossRef]

- Byrne, S.C.; Miller, P.; Seguinot-Medina, S.; Waghiyi, V.; Buck, C.L.; Von Hippel, F.A.; Carpenter, D.O. Associations between Serum Polybrominated Diphenyl Ethers and Thyroid Hormones in a Cross Sectional Study of a Remote Alaska Native Population. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8. [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.R.; Harden, F.A.; Toms, L.-M.L.; Norman, R.E. Health Consequences of Exposure to Brominated Flame Retardants: A Systematic Review. Chemosphere 2014, 106, 1–19. [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Chen, J.; Du, Q.; Wang, B.; Qu, Y.; Chang, Z. Toxic Effects of Dechlorane plus on the Common Carp (Cyprinus Carpio) Embryonic Development. Chemosphere 2020, 249, 126481. [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Chen, Y.; Huang, C.; Dong, Q.; Roper, C.; Tanguay, R.L.; Zhu, Y.; Zhang, Y. Neurodevelopmental Toxicity Assessments of Alkyl Phenanthrene and Dechlorane Plus Co-Exposure in Zebrafish. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2019, 180, 762–769. [CrossRef]

- Angerer, J.; Aylward, L.L.; Hays, S.M.; Heinzow, B.; Wilhelm, M. Human Biomonitoring Assessment Values: Approaches and Data Requirements. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 2011, 214, 348–360. [CrossRef]

- Zota, A.R.; Adamkiewicz, G.; Morello-Frosch, R.A. Are PBDEs an Environmental Equity Concern? Exposure Disparities by Socioeconomic Status. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2010, 44, 5691–5692. [CrossRef]

- Gravel, S.; Aubin, S.; Labrèche, F. Assessment of Occupational Exposure to Organic Flame Retardants: A Systematic Review. Ann. Work Expo. Health 2019, 63, 386–406. [CrossRef]

- Horton, M.K.; Bousleiman, S.; Jones, R.; Sjodin, A.; Liu, X.; Whyatt, R.; Wapner, R.; Factor-Litvak, P. Predictors of Serum Concentrations of Polybrominated Flame Retardants among Healthy Pregnant Women in an Urban Environment: A Cross-Sectional Study. Environ. Health 2013, 12, 23. [CrossRef]

- Cequier, E.; Marcé, R.M.; Becher, G.; Thomsen, C. Comparing Human Exposure to Emerging and Legacy Flame Retardants from the Indoor Environment and Diet with Concentrations Measured in Serum. Environ. Int. 2015, 74, 54–59. [CrossRef]

- Fraser, A.J.; Webster, T.F.; McClean, M.D. Diet Contributes Significantly to the Body Burden of PBDEs in the General U.S. Population. Environ. Health Perspect. 2009, 117, 1520–1525. [CrossRef]

- Herbstman, J.B.; Sjödin, A.; Apelberg, B.J.; Witter, F.R.; Patterson, D.G.; Halden, R.U.; Jones, R.S.; Park, A.; Zhang, Y.; Heidler, J.; et al. Determinants of Prenatal Exposure to Polychlorinated Biphenyls (PCBs) and Polybrominated Diphenyl Ethers (PBDEs) in an Urban Population. Environ. Health Perspect. 2007, 115, 1794–1800. [CrossRef]

- Bramwell, L.; Harrad, S.; Abou-Elwafa Abdallah, M.; Rauert, C.; Rose, M.; Fernandes, A.; Pless-Mulloli, T. Predictors of Human PBDE Body Burdens for a UK Cohort. Chemosphere 2017, 189, 186–197. [CrossRef]

- Mustieles, V.; Arrebola, J.P. How Polluted Is Your Fat? What the Study of Adipose Tissue Can Contribute to Environmental Epidemiology. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2020, 74, 401–407. [CrossRef]

- Xie, B.; Lin, X.; Wu, K.; Chen, J.; Qiu, S.; Luo, J.; Huang, Y.; Peng, L. Adipose Tissue Levels of Polybrominated Diphenyl Ethers in Relation to Prognostic Biomarkers and Progression-Free Survival Time of Breast Cancer Patients in Eastern Area of Southern China: A Hospital-Based Study. Environ. Res. 2023, 216, 114779. [CrossRef]

- Aaseth, J.; Javorac, D.; Djordjevic, A.B.; Bulat, Z.; Skalny, A.V.; Zaitseva, I.P.; Aschner, M.; Tinkov, A.A. The Role of Persistent Organic Pollutants in Obesity: A Review of Laboratory and Epidemiological Studies. Toxics 2022, 10, 65. [CrossRef]

- Arrebola, J.P.; Martin-Olmedo, P.; Fernandez, M.F.; Sanchez-Cantalejo, E.; Jimenez-Rios, J.A.; Torne, P.; Porta, M.; Olea, N. Predictors of Concentrations of Hexachlorobenzene in Human Adipose Tissue: A Multivariate Analysis by Gender in Southern Spain. Environ. Int. 2009, 35, 27–32. [CrossRef]

- Cifras oficiales de población de los municipios españoles en aplicación de la Ley de Bases del Régimen Local (Art. 17); Granada: Población por municipios y sexo. (2871) Available online: https://www.ine.es/jaxiT3/Datos.htm?t=2871#_tabs-tabla (accessed on 19 July 2024).

- Covaci, A.; Voorspoels, S.; Roosens, L.; Jacobs, W.; Blust, R.; Neels, H. Polybrominated Diphenyl Ethers (PBDEs) and Polychlorinated Biphenyls (PCBs) in Human Liver and Adipose Tissue Samples from Belgium. Chemosphere 2008, 73, 170–175. [CrossRef]

- Lipičar, E.; Fras, D.; Javernik, N.; Prosen, H. Simultaneous Method for Selected PBDEs and HBCDDs in Foodstuffs Using Gas Chromatography—Tandem Mass Spectrometry and Liquid Chromatography—Tandem Mass Spectrometry. Toxics 2023, 11, 15. [CrossRef]

- Saini, R.K.; Prasad, P.; Shang, X.; Keum, Y.-S. Advances in Lipid Extraction Methods—A Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 13643. [CrossRef]

- Grande, C.; Castaño, A.; Ramos, J.J. Sensitive Instrumental Method for Quantitative Determination of High-Brominated Flame Retardants in Human Serum Samples. J. AOAC Int. 2023, 106, 880–885. [CrossRef]

- Rivas, A.; Fernandez, M.F.; Cerrillo, I.; Ibarluzea, J.; Olea-Serrano, M.F.; Pedraza, V.; Olea, N. Human Exposure to Endocrine Disrupters: Standardisation of a Marker of Estrogenic Exposure in Adipose Tissue. APMIS Acta Pathol. Microbiol. Immunol. Scand. 2001, 109, 185–197. [CrossRef]

- Phillips, D.L.; Pirkle, J.L.; Burse, V.W.; Bernert, J.T.; Henderson, L.O.; Needham, L.L. Chlorinated Hydrocarbon Levels in Human Serum: Effects of Fasting and Feeding. Arch. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 1989, 18, 495–500. [CrossRef]

- Regidor, E. The Goldthorpe social class classification: Framework of reference for the proposal for the measure of social class by the Working Group of the Spanish Epidemiological Society. Rev. Esp. Salud Publica 2001, 75, 13–22.

- Linares, V.; Bellés, M.; Domingo, J.L. Human Exposure to PBDE and Critical Evaluation of Health Hazards. Arch. Toxicol. 2015, 89, 335–356. [CrossRef]

- Paliya, S.; Mandpe, A.; Kumar, M.S.; Kumar, S.; Kumar, R. Assessment of Polybrominated Diphenyl Ether Contamination and Associated Human Exposure Risk at Municipal Waste Dumping Sites. Environ. Geochem. Health 2022, 44, 4437–4453. [CrossRef]

- Pietron, W.J.; Malagocki, P.; Warenik-Bany, M. Feed as a Source of Polybrominated Diphenyl Ethers (PBDEs). Environ. Res. 2023, 231, 116257. [CrossRef]

- Arvaniti, O.S.; Kalantzi, O.-I. Determinants of Flame Retardants in Non-Occupationally Exposed Individuals – A Review. Chemosphere 2021, 263, 127923. [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; He, C.; Han, W.; Song, J.; Li, H.; Zhang, Y.; Jing, X.; Wu, W. Exposure Pathways, Levels and Toxicity of Polybrominated Diphenyl Ethers in Humans: A Review. Environ. Res. 2020, 187, 109531. [CrossRef]

- Thiese, M.S.; Ronna, B.; Ott, U. P Value Interpretations and Considerations. J. Thorac. Dis. 2016, 8, E928–E931. [CrossRef]

- Greenland, S. Modeling and Variable Selection in Epidemiologic Analysis. Am. J. Public Health 1989, 79, 340–349. [CrossRef]

- R Core Team R: The R Project for Statistical Computing. 4.5.0. 2025.

- Sjoberg, D.D.; Whiting, K.; Curry, M.; Lavery, J.A.; Larmarange, J. Reproducible Summary Tables with the Gtsummary Package. R J. 2021, 13, 570–580.

- Instituto nacional de estadística Encuesta nacional de salud de España Available online: https://www.sanidad.gob.es/estadEstudios/estadisticas/encuestaNacional/encuestaNac2003/home.htm (accessed on 7 September 2025).

- Bjermo, H.; Aune, M.; Cantillana, T.; Glynn, A.; Lind, P.M.; Ridefelt, P.; Darnerud, P.O. Serum Levels of Brominated Flame Retardants (BFRs: PBDE, HBCD) and Influence of Dietary Factors in a Population-Based Study on Swedish Adults. Chemosphere 2017, 167, 485–491. [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, M.F.; Araque, P.; Kiviranta, H.; Molina-Molina, J.M.; Rantakokko, P.; Laine, O.; Vartiainen, T.; Olea, N. PBDEs and PBBs in the Adipose Tissue of Women from Spain. Chemosphere 2007, 66, 377–383. [CrossRef]

- Ingelido, A.M.; Ballard, T.; Dellatte, E.; di Domenico, A.; Ferri, F.; Fulgenzi, A.R.; Herrmann, T.; Iacovella, N.; Miniero, R.; Päpke, O.; et al. Polychlorinated Biphenyls (PCBs) and Polybrominated Diphenyl Ethers (PBDEs) in Milk from Italian Women Living in Rome and Venice. Chemosphere 2007, 67, S301-306. [CrossRef]

- Wu, N.; Herrmann, T.; Paepke, O.; Tickner, J.; Hale, R.; Harvey, L.E.; La Guardia, M.; McClean, M.D.; Webster, T.F. Human Exposure to PBDEs: Associations of PBDE Body Burdens with Food Consumption and House Dust Concentrations. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2007, 41, 1584–1589. [CrossRef]

- Eljarrat, E.; de la Cal, A.; Raldua, D.; Duran, C.; Barcelo, D. Brominated Flame Retardants in Alburnus Alburnus from Cinca River Basin (Spain). Environ. Pollut. Barking Essex 1987 2005, 133, 501–508. [CrossRef]

- Fängström, B.; Hovander, L.; Bignert, A.; Athanassiadis, I.; Linderholm, L.; Grandjean, P.; Weihe, P.; Bergman, A. Concentrations of Polybrominated Diphenyl Ethers, Polychlonnated Biphenyls, and Polychlorobiphenylols in Serum from Pregnant Faroese Women and Their Children 7 Years Later. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2005, 39, 9457–9463. [CrossRef]

- Thomas, G.O.; Wilkinson, M.; Hodson, S.; Jones, K.C. Organohalogen Chemicals in Human Blood from the United Kingdom. Environ. Pollut. 2006, 141, 30–41. [CrossRef]

- Thuresson, K.; Höglund, P.; Hagmar, L.; Sjödin, A.; Bergman, Å.; Jakobsson, K. Apparent Half-Lives of Hepta- to Decabrominated Diphenyl Ethers in Human Serum as Determined in Occupationally Exposed Workers. Environ. Health Perspect. 2006, 114, 176–181. [CrossRef]

- Fraser, A.J.; Webster, T.F.; McClean, M.D. Diet Contributes Significantly to the Body Burden of PBDEs in the General U.S. Population. Environ. Health Perspect. 2009, 117, 1520–1525. [CrossRef]

- Bjermo, H.; Aune, M.; Cantillana, T.; Glynn, A.; Lind, P.M.; Ridefelt, P.; Darnerud, P.O. Serum Levels of Brominated Flame Retardants (BFRs: PBDE, HBCD) and Influence of Dietary Factors in a Population-Based Study on Swedish Adults. Chemosphere 2017, 167, 485–491. [CrossRef]

- Kuo, L.-J.; Cade, S.E.; Cullinan, V.; Schultz, I.R. Polybrominated Diphenyl Ethers (PBDEs) in Plasma from E-Waste Recyclers, Outdoor and Indoor Workers in the Puget Sound, WA Region. Chemosphere 2019, 219, 209–216. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Yang, X.; Du, Y.; Li, R.; Zhou, T.; Wang, Y.; Chen, T.; Wang, D.; Shi, Z. Polybrominated Diphenyl Ethers in Serum from Residents Living in a Brominated Flame Retardant Production Area: Occurrence, Influencing Factors, and Relationships with Thyroid and Liver Function. Environ. Pollut. Barking Essex 1987 2021, 270, 116046. [CrossRef]

- Sjödin, A.; Wong, L.-Y.; Jones, R.S.; Park, A.; Zhang, Y.; Hodge, C.; DiPietro, E.; McClure, C.; Turner, W.; Needham, L.L.; et al. Serum Concentrations of Polybrominated Diphenyl Ethers (PBDEs) and Polybrominated Biphenyl (PBB) in the United States Population: 2003–2004. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2008, 42, 1377–1384. [CrossRef]

- Sjödin, A.; Jones, R.S.; Wong, L.-Y.; Caudill, S.P.; Calafat, A.M. Polybrominated Diphenyl Ethers and Biphenyl in Serum: Time Trend Study from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey for Years 2005/06 through 2013/14. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2019, 53, 6018–6024. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Song, Q.; Cao, Z.; Su, X.; Hua, J.; Zhang, Y.; He, X. Umbilical Cord Blood PBDEs Concentrations in Relation to Placental Size at Birth. Chemosphere 2018, 201, 20–24. [CrossRef]

- Vizcaino, E.; Grimalt, J.O.; Fernández-Somoano, A.; Tardon, A. Transport of Persistent Organic Pollutants across the Human Placenta. Environ. Int. 2014, 65, 107–115. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.G.; Sun, X.W.; Ai, H. Levels and Congener Profiles of Polybrominated Diphenyl Ethers (PBDEs) in Primipara Breast Milk from Shenzhen and Exposure Risk for Breast-Fed Infants. J. Environ. Monit. 2012, 14, 893–900. [CrossRef]

- Gómara, B.; Herrero, L.; Pacepavicius, G.; Ohta, S.; Alaee, M.; González, M.J. Occurrence of Co-Planar Polybrominated/Chlorinated Biphenyls (PXBs), Polybrominated Diphenyl Ethers (PBDEs) and Polychlorinated Biphenyls (PCBs) in Breast Milk of Women from Spain. Chemosphere 2011, 83, 799–805. [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.H.; Lee, Y.J.; Lee, E.; Patra, N.; Lee, J.; Kwack, S.J.; Kim, K.B.; Chung, K.K.; Han, S.Y.; Han, J.Y.; et al. Exposure Assessment of Polybrominated Diphenyl Ethers (PBDE) in Umbilical Cord Blood of Korean Infants. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health A 2009, 72, 1318–1326. [CrossRef]

- Arbuckle, T.E.; Kubwabo, C.; Walker, M.; Davis, K.; Lalonde, K.; Kosarac, I.; Wen, S.W.; Arnold, D.L. Umbilical Cord Blood Levels of Perfluoroalkyl Acids and Polybrominated Flame Retardants. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 2013, 216, 184–194. [CrossRef]

- Foster, W.G.; Gregorovich, S.; Morrison, K.M.; Atkinson, S.A.; Kubwabo, C.; Stewart, B.; Teo, K. Human Maternal and Umbilical Cord Blood Concentrations of Polybrominated Diphenyl Ethers. Chemosphere 2011, 84, 1301–1309. [CrossRef]

- Arrebola, J.P.; Fernández, M.F.; Olea, N.; Ramos, R.; Martin-Olmedo, P. Human Exposure to p,P′-Dichlorodiphenyldichloroethylene (p,P′-DDE) in Urban and Semi-Rural Areas in Southeast Spain: A Gender Perspective. Sci. Total Environ. 2013, 458–460, 209–216. [CrossRef]

- Salcedo-Bellido, I.; Amaya, E.; Pérez-Díaz, C.; Soler, A.; Vela-Soria, F.; Requena, P.; Barrios-Rodríguez, R.; Echeverría, R.; Pérez-Carrascosa, F.M.; Quesada-Jiménez, R.; et al. Differential Bioaccumulation Patterns of α, β-Hexachlorobenzene and Dicofol in Adipose Tissue from the GraMo Cohort (Southern Spain). Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2022, 19. [CrossRef]

- Sjödin, A.; Wong, L.-Y.; Jones, R.S.; Park, A.; Zhang, Y.; Hodge, C.; DiPietro, E.; McClure, C.; Turner, W.; Needham, L.L.; et al. Serum Concentrations of Polybrominated Diphenyl Ethers (PBDEs) and Polybrominated Biphenyl (PBB) in the United States Population: 2003–2004. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2008, 42, 1377–1384. [CrossRef]

- Garí, M.; Grimalt, J.O. Inverse Age-Dependent Accumulation of Decabromodiphenyl Ether and Other PBDEs in Serum from a General Adult Population. Environ. Int. 2013, 54, 119–127. [CrossRef]

- Jain, R.B. Effect of Smoking and Caffeine Consumption on Polybrominated Diphenyl Ethers (PBDE) and Polybrominated Biphenyls (PBB). J. Toxicol. Environ. Health A 2013, 76, 515–532. [CrossRef]

- Wolff, M.S.; Britton, J.A.; Teitelbaum, S.L.; Eng, S.; Deych, E.; Ireland, K.; Liu, Z.; Neugut, A.I.; Santella, R.M.; Gammon, M.D. Improving Organochlorine Biomarker Models for Cancer Research. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 2005, 14, 2224–2236. [CrossRef]

- Estill, C.F.; Slone, J.; Mayer, A.; Chen, I.-C.; LaGuardia, M. Worker Exposure to Flame Retardants in Manufacturing, Construction and Service Industries. Environ. Int. 2020, 135, 105349. [CrossRef]

- Estill, C.F.; Mayer, A.C.; Chen, I.-C.; Slone, J.; LaGuardia, M.J.; Jayatilaka, N.; Ospina, M.; Sjodin, A.; Calafat, A.M. Biomarkers of Organophosphate and Polybrominated Diphenyl Ether (PBDE) Flame Retardants of American Workers and Associations with Inhalation and Dermal Exposures. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2024, 58, 8417–8431. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Feng, Y.; Chen, Y.; Li, T.; Tan, Y.; Ma, Y.; Zhang, Z. Annual Flux Estimation and Source Apportionment of PCBs and PBDEs in the Middle Reach of Yangtze River, China. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 885, 163772. [CrossRef]

- Siddiqi, M.A.; Laessig, R.H.; Reed, K.D. Polybrominated Diphenyl Ethers (PBDEs): New Pollutants-Old Diseases. Clin. Med. Res. 2003, 1, 281–290. [CrossRef]

- Kim, U.-J.; Lee, I.-S.; Kim, H.S.; Oh, J.-E. Monitoring of PBDEs Concentration in Umbilical Cord Blood and Breast Milk from Korean Population and Estimating the Effects of Various Parameters on Accumulation in Humans. Chemosphere 2011, 85, 487–493. [CrossRef]

- Yin, H.; Ma, J.; Li, Z.; Li, Y.; Meng, T.; Tang, Z. Polybrominated Diphenyl Ethers and Heavy Metals in a Regulated E-Waste Recycling Site, Eastern China: Implications for Risk Management. Molecules 2021, 26, 2169. [CrossRef]

- Le Daré, B.; Lagente, V.; Gicquel, T. Ethanol and Its Metabolites: Update on Toxicity, Benefits, and Focus on Immunomodulatory Effects. Drug Metab. Rev. 2019, 51, 545–561. [CrossRef]

- Leung, T.M.; Lu, Y. Alcoholic Liver Disease: From CYP2E1 to CYP2A5. Curr. Mol. Pharmacol. 2017, 10, 172–178. [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Zhu, X.; Badawy, S.; Ihsan, A.; Liu, Z.; Xie, C.; Wang, X. Metabolism and Mechanism of Human Cytochrome P450 Enzyme 1A2. Curr. Drug Metab. 2021, 22, 40–49. [CrossRef]

- Hukkanen, J.; Jacob, P.; Peng, M.; Dempsey, D.; Benowitz, N.L. Effect of Nicotine on Cytochrome P450 1A2 Activity. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2011, 72, 836–838. [CrossRef]

- Washio, I.; Maeda, M.; Sugiura, C.; Shiga, R.; Yoshida, M.; Nonen, S.; Fujio, Y.; Azuma, J. Cigarette Smoke Extract Induces CYP2B6 through Constitutive Androstane Receptor in Hepatocytes. Drug Metab. Dispos. Biol. Fate Chem. 2011, 39, 1–3. [CrossRef]

- Stapleton, H.M.; Kelly, S.M.; Pei, R.; Letcher, R.J.; Gunsch, C. Metabolism of Polybrominated Diphenyl Ethers (PBDEs) by Human Hepatocytes in Vitro. Environ. Health Perspect. 2009, 117, 197–202. [CrossRef]

- Erratico, C.A.; Szeitz, A.; Bandiera, S.M. Oxidative Metabolism of BDE-99 by Human Liver Microsomes: Predominant Role of CYP2B6. Toxicol. Sci. 2012, 129, 280–292. [CrossRef]

- Feo, M.L.; Gross, M.S.; McGarrigle, B.P.; Eljarrat, E.; Barceló, D.; Aga, D.S.; Olson, J.R. Biotransformation of BDE-47 to Potentially Toxic Metabolites Is Predominantly Mediated by Human CYP2B6. Environ. Health Perspect. 2013, 121, 440–446. [CrossRef]

- Ma, S.; Ren, G.; Zheng, K.; Cui, J.; Li, P.; Huang, X.; Lin, M.; Liu, R.; Yuan, J.; Yin, W.; et al. New Insights into Human Biotransformation of BDE-209: Unique Occurrence of Metabolites of Ortho-Substituted Hydroxylated Higher Brominated Diphenyl Ethers in the Serum of e-Waste Dismantlers. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 56, 10239–10248. [CrossRef]

- Ni, K.; Lu, Y.; Wang, T.; Kannan, K.; Gosens, J.; Xu, L.; Li, Q.; Wang, L.; Liu, S. A Review of Human Exposure to Polybrominated Diphenyl Ethers (PBDEs) in China. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 2013, 216, 607–623. [CrossRef]

- Bocio, A.; Llobet, J.M.; Domingo, J.L.; Corbella, J.; Teixidó, A.; Casas, C. Polybrominated Diphenyl Ethers (PBDEs) in Foodstuffs: Human Exposure through the Diet. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2003, 51, 3191–3195. [CrossRef]

- Fraser, A.J.; Webster, T.F.; McClean, M.D. Diet Contributes Significantly to the Body Burden of PBDEs in the General U.S. Population. Environ. Health Perspect. 2009, 117, 1520–1525. [CrossRef]

- Wu, N.; Herrmann, T.; Paepke, O.; Tickner, J.; Hale, R.; Harvey, E.; La Guardia, M.; McClean, M.D.; Webster, T.F. Human Exposure to PBDEs: Associations of PBDE Body Burdens with Food Consumption and House Dust Concentrations. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2007, 41, 1584–1589. [CrossRef]

- Pardo, O.; Fernández, S.F.; Quijano, L.; Marín, S.; Villalba, P.; Corpas-Burgos, F.; Yusà, V. Polybrominated Diphenyl Ethers in Foods from the Region of Valencia: Dietary Exposure and Risk Assessment. Chemosphere 2020, 250, 126247. [CrossRef]

- Schecter, A.; Haffner, D.; Colacino, J.; Patel, K.; Päpke, O.; Opel, M.; Birnbaum, L. Polybrominated Diphenyl Ethers (PBDEs) and Hexabromocyclodecane (HBCD) in Composite U.S. Food Samples. Environ. Health Perspect. 2010, 118, 357–362. [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Wang, M.; Yang, Y.; Lei, B.; Ma, S.; Yu, Y. Influence of Nutrients on the Bioaccessibility and Transepithelial Transport of Polybrominated Diphenyl Ethers Measured Using an in Vitro Method and Caco-2 Cell Monolayers. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2021, 208, 111569. [CrossRef]

- Jin, W.; Otake, M.; Eguchi, A.; Sakurai, K.; Nakaoka, H.; Watanabe, M.; Todaka, E.; Mori, C. Dietary Habits and Cooking Methods Could Reduce Avoidable Exposure to PCBs in Maternal and Cord Sera. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 17357. [CrossRef]

- Horton, M.K.; Bousleiman, S.; Jones, R.; Sjodin, A.; Liu, X.; Whyatt, R.; Wapner, R.; Factor-Litvak, P. Predictors of Serum Concentrations of Polybrominated Flame Retardants among Healthy Pregnant Women in an Urban Environment: A Cross-Sectional Study. Environ. Health 2013, 12, 23. [CrossRef]

| Variable | All (n = 134) | Females (n = 61) | Males (n = 73) |

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | |

| Sex = Female | 61 (45.5%) | 61 (100.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Residence | |||

| Urban | 24 (17.9%) | 6 (9.8%) | 18 (24.7%) |

| Semirural | 59 (44.0%) | 39 (63.9%) | 20 (27.4%) |

| Rural | 51 (38.1%) | 16 (26.2%) | 35 (47.9%) |

| Social occupational class = Manual workers | 104 (77.6%) | 48 (78.7%) | 56 (76.7%) |

| Alcohol consumers | 69 (51.5%) | 18 (29.5%) | 51 (69.9%) |

| Smoking habit | |||

| No smoker | 51 (38.1%) | 38 (62.3%) | 13 (17.8%) |

| Former smoker | 34 (25.4%) | 10 (16.4%) | 24 (32.9%) |

| Smoker | 49 (36.6%) | 13 (21.3%) | 36 (49.3%) |

| Sample collection’s surgery | |||

| Hernia | 63 (47.0%) | 16 (26.2%) | 47 (64.4%) |

| Gallbladder | 20 (14.9%) | 14 (23.0%) | 6 (8.2%) |

| Benign tumor/hyperplasia | 14 (10.4%) | 10 (16.4%) | 4 (5.5%) |

| Other | 37 (27.6%) | 21 (34.4%) | 16 (21.9%) |

| Mean (SD1) | Mean (SD1) | Mean (SD1) | |

| Age (years) | 50 (17.3) | 51 (17.3) | 50 (17.4) |

| BMI3 (kg/m2) | 27.9 (5.6) | 27.6 (5.7) | 28.0 (5.6) |

| Median (IQR2) | Median (IQR2) | Median (IQR2) | |

| BDE4-28 | 73.1 (35.0, 127.2) | 58.6 (31.8, 115.9) | 93.7 (41.5, 136.0) |

| BDE4-47 | 353.0 (203.5, 546.7) | 266.2 (179.4, 456.3) | 393.6 (276.8, 579.4) |

| BDE4-99 | 130.8 (89.9, 230.7) | 117.4 (81.4, 184.8) | 140.5 (102.0, 294.6) |

| BDE4-100 | 301.4 (173.0, 453.4) | 287.3 (159.3, 403.0) | 313.6 (194.6, 455.7) |

| BDE4-153 | 1,335.2 (918.2, 2,432.2) | 1,205.1 (842.7, 1,831.0) | 1,501.5 (994.5, 3,116.0) |

| BDE4-154 | 429.7 (306.6, 678.7) | 412.0 (277.8, 583.1) | 483.3 (325.6, 689.6) |

| BDE4-183 | 419.2 (247.2, 595.7) | 412.3 (248.5, 581.8) | 420.0 (242.2, 677.8) |

| BDE4-197 | 564.5 (338.5, 990.9) | 560.1 (342.7, 974.0) | 569.0 (321.0, 1,001.1) |

| BDE4-209 | 614.4 (308.2, 1,052.4) | 543.7 (190.9, 1,006.4) | 693.3 (342.0, 1,121.0) |

| Syn-DP5 | 82.9 (39.9, 163.9) | 79.7 (37.2, 147.4) | 84.4 (42.8, 182.1) |

| Anti-DP5 | 247.0 (157.7, 417.6) | 274.3 (179.6, 350.3) | 226.7 (148.5, 481.5) |

| BDE-281 | BDE-471 | BDE-991 | BDE-1001 | BDE-1531 | BDE-1541 | BDE-1831 | BDE-1971 | BDE-2091 | Syn-DP2 | Anti-DP2 | ||

| β3 (95% CI)4 | ||||||||||||

| Sex = male | 0.37 (0.02, 0.71) | 0.47 (0.12, 0.82) | 0.42 (0.05, 0.79) | 1.06 (0.27, 1.84) | ||||||||

| Age (years) | -0.01 (-0.02, 0.00) | -0.01 (-0.02, 0.00) | -0.01 (-0.02, 0.00) | |||||||||

| BMI5 (Kg/m2) | -0.04 (-0.07, -0.01) | -0.03 (-0.05, -0.01) | -0.05 (-0.07, -0.02) | -0.04 (-0.07, -0.01) | -0.04 (-0.06, -0.02) | |||||||

| Occupation = Manual worker | -0.54 (-0.95, -0.13) | 0.33 (0.01, 0.64) | 0.51 (0.07, 0.94) | 0.38 (0.06, 0.69) | ||||||||

| Residence | ||||||||||||

| Urban6 | Ref. | |||||||||||

| Semirural7 | -0.16 (-0.51, 0.20) | |||||||||||

| Rural8 | -0.36 (-0.72, 0.00) | |||||||||||

| BDE-281 | BDE-471 | BDE-991 | BDE-1001 | BDE-1531 | BDE-1541 | BDE-1831 | BDE-1971 | BDE-2091 | Syn-DP2 | Anti-DP2 | |

| Perceived exposure to | β3 (95% CI)4 | ||||||||||

| Paints = Yes | 0.61 (0.16, 1.06) | 0.85 (0.40, 1.30)* | 0.80 (0.41, 1.19) | 0.56 (0.05, 1.08) | 0.67 (0.22, 1.13) | ||||||

| Solvents = Yes | 0.42 (0.02, 0.82) | 0.58 (0.18, 0.98) | 0.44 (-0.01, 0.89) | ||||||||

| Toxic Metals = Yes | -0.74 (-1.27, -0.22) | -0.38 (-0.82, 0.06) | -1.05 (-1.58, -0.52)* | -0.38 (-0.75, -0.01) | |||||||

| Alcohol consumption = Yes | -0.80 (-1.59, -0.02) | 0.32 (-0.04, 0.69) | |||||||||

| Smoking habit | |||||||||||

| No smoker | Ref. | ||||||||||

| Former smoker | 0.48 (0.11, 0.85) | ||||||||||

| Smoker | 0.16 (-0.19, 0.50) | ||||||||||

| BDE-281 | BDE-471 | BDE-991 | BDE-1001 | BDE-1531 | BDE-1541 | BDE-1831 | BDE-1971 | BDE-2091 | Syn-DP2 | Anti-DP2 | |

| β3 (95% CI)4 | |||||||||||

| Fish consumption ≥ 2 portions/week | 0.38 (0.11, 0.65) | 0.38 (0.08, 0.69) | |||||||||

| Oily fish consumption = Yes | 0.45 (0.14, 0.77) | ||||||||||

| Meat consumption > 2 portions/week | 0.45 (0.11, 0.80) | ||||||||||

| Vegetables consumption > 2 portions/week | 0.42 (-0.07, 0.91) | -0.54 (-0.96, -0.12) | -0.35 (-0.70, 0.00) | ||||||||

| Fruit consumption > 2 portions/week | 0.36 (-0.01, 0.74) | 0.46 (0.04, 0.88) | 0.50 (-0.01, 1.01) | ||||||||

| Bread consumption > 1 portions/week | 0.35 (-0.07, 0.77) | ||||||||||

| Cheese consumption > 2 portions/week | 0.49 (0.16, 0.82) | ||||||||||

| Number of glasses of milk per day | 0.20 (0.06, 0.35) | ||||||||||

| Egg consumption | |||||||||||

| ≤ 1 portion/week | Ref. | ||||||||||

| 2 portions/week | -0.35 (-0.70, -0.01) | ||||||||||

| > 2 portions/week | -0.34 (-0.72, 0.05) | ||||||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.