1. Introduction

Melanin is the primary pigment determining the coloration of skin, hair, and eyes, while simultaneously providing essential protection against DNA damage induced by ultraviolet (UV) radiation [

1]. Melanogenesis, the biosynthetic pathway producing melanin, involves an intricate enzymatic cascade initiated by the tyrosinase-catalyzed conversion of L-tyrosine into L-3,4-dihydroxyphenylalanine (L-DOPA), followed by progressive oxidation and polymerization into melanin macromolecules [

2,

3]. The microphthalmia-associated transcription factor (MITF) serves as the master regulator of this process, governing the transcriptional activation of key melanogenic enzymes, including tyrosinase (TYR), tyrosinase-related protein-1 (TRP-1), and dopachrome tautomerase (DCT/TRP-2) [

2,

4,

5]. Multiple intracellular signaling cascades, notably the cAMP-dependent protein kinase A (PKA), MAPK, and Wnt/β-catenin pathways, converge to modulate MITF activity in response to external stimuli such as UV radiation, hormones, and inflammatory mediators [

2,

6,

7,

8]. While photoprotective, excessive melanin deposition characterizes hyperpigmentation disorders such as melasma, solar lentigines, and post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation (PIH), which present substantial aesthetic and psychological burdens to affected individuals [

9,

10].

PIH represents one of the most common acquired pigmentary disorders, characterized by darkened patches of skin that develop following inflammatory or traumatic insults to the epidermis and dermis [

11]. PIH can arise from diverse triggers, including acne vulgaris, atopic dermatitis, infections, and cosmetic procedures, significantly impacting patients' quality of life [

11]. The pathogenesis of PIH involves a complex interplay between inflammatory mediators and melanocyte activity. During the inflammatory response, keratinocytes, fibroblasts, and immune cells (including mast cells and macrophages) release various mediators such as prostaglandins, cytokines (IL-1α, IL-6, TNF-α), reactive oxygen species, and histamine. These mediators stimulate melanocyte activity, leading to increased melanin synthesis and transfer to surrounding keratinocytes [

12]. Despite its clinical prevalence, current therapeutic options primarily targeting tyrosinase activity or epidermal turnover frequently yield slow or incomplete responses and carry risks of adverse effects [

11]. Histamine is a potent stimulator of melanogenesis, particularly in pruritic inflammatory conditions that lead to pronounced PIH [

13,

14]. Early investigations demonstrated that histamine induces morphological changes, including cell enlargement and increased dendricity, alongside elevated tyrosinase activity and melanin content [

13]. Subsequent studies confirmed that histamine also enhances melanocyte proliferation and migration [

15]. Mechanistically, H2 receptor activation increases intracellular cyclic AMP (cAMP) accumulation, which activates PKA, ultimately upregulating MITF and its downstream targets [

13].

Intracellular calcium (Ca2+) serves as another critical second messenger in melanogenesis, directly influencing melanin synthesis by modulating cAMP and tyrosinase activity [

16,

17,

18,

19]. Elevated intracellular Ca2+ enhances melanin production, while disruption of calcium homeostasis impairs pigmentation [

16,

17,

20]. Ca2+-dependent kinases, such as CaMKII and PKC, transduce calcium signals by phosphorylating key regulators like CREB and MITF [

21]. Among various calcium entry mechanisms, store-operated calcium entry (SOCE) has emerged as a key regulator. Previous studies have established that ORAI1 mediates melanin synthesis triggered by endothelin-1 (ET-1) and UVB, where pharmacological inhibition or siRNA-mediated ORAI1 downregulation significantly reduces Ca2+ entry and tyrosinase activity [

22,

23,

24].

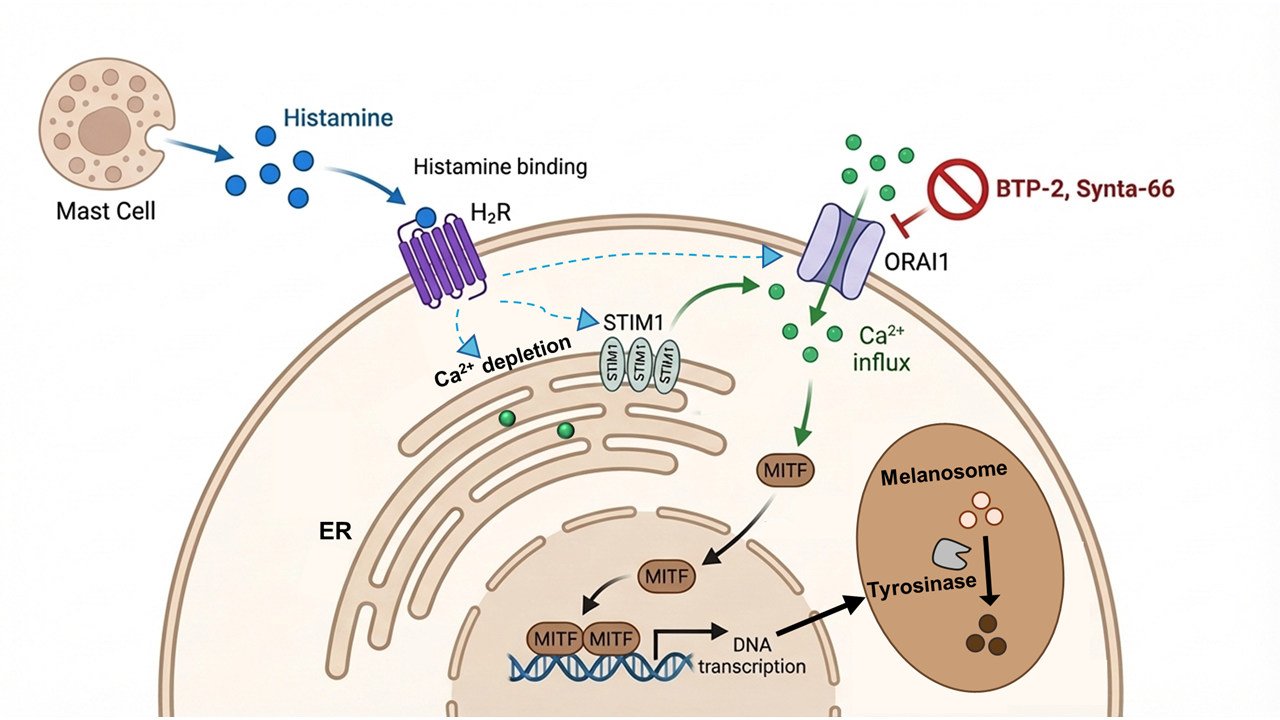

Despite these advances, critical gaps remain regarding how inflammatory mediators drive sustained melanin overproduction in PIH. While histamine signals via H2 receptors and ORAI1 mediates ET-1-induced melanogenesis, the potential crosstalk between these systems remains unexplored. Significantly, in other pathological models, chronic exposure to inflammatory stimuli has been shown to induce 'SOCE remodeling', a phenotypic shift that enhances the Ca2+signaling machinery.

Building on these observations, we hypothesized that chronic histamine exposure might remodel the SOCE machinery in melanocytes, thereby enhancing Ca2+ entry to drive sustained melanin production. In this study, we investigated the role of ORAI1 channels in histamine-induced melanogenesis. We aimed to determine the effects of histamine on SOCE capacity and the specific contribution of ORAI1 to melanin production in both B16F10 melanoma cells and normal human epidermal melanocytes (NHEMs). Our findings identify ORAI1 as a potential therapeutic target for inflammation-associated pigmentary disorders.

3. Discussion

In this study, we investigated the role of ORAI1 calcium channels in histamine-induced melanogenesis and uncovered a novel calcium-dependent mechanism linking inflammatory mediators to melanin production. Our key findings demonstrate that: (1) histamine significantly increases melanin content in both B16F10 melanoma cells and primary human melanocytes (NHEMs) through H2 receptor activation; (2) while acute histamine application does not trigger immediate calcium influx, chronic histamine pretreatment significantly enhances the capacity for SOCE ; (3) intracellular calcium is essential for histamine-induced melanogenesis; (4) ORAI1 and STIM1 serve as the primary molecular mediators of SOCE in melanocytes ; and (5) pharmacological inhibition or genetic silencing of ORAI1 or STIM1 effectively suppresses histamine-induced melanin production. These findings reveal ORAI1-STIM1 mediated calcium signaling as a critical pathway in histamine-induced melanogenesis and establish ORAI1 channels as a potential therapeutic target for PIH.

Our results confirm previous findings that histamine-induced melanogenesis is mediated specifically through H2 receptors, as demonstrated by the complete blockade with the H2 antagonist famotidine while H1 and H3 antagonists showed no effect. This is consistent with earlier reports by Yoshida et al., who established that histamine stimulates melanogenesis via H2 receptor-cAMP/PKA signaling in human melanocytes [

13]. However, our study reveals a previously unrecognized role for calcium signaling in this process.

A pivotal finding of this study is the temporal distinction in histamine's effect on calcium signaling. Acute histamine application (1–100 μM) failed to trigger immediate calcium influx, yet chronic histamine pretreatment (48 hours in B16F10 cells, 6 days in NHEMs) significantly enhanced SOCE capacity by approximately 2.8-fold. This time-dependent effect suggests that histamine does not directly activate calcium channels but rather induces a functional remodeling of the Ca2+ signaling machinery over time. The requirement for chronic exposure aligns with the clinical observation that PIH develops gradually during sustained inflammation rather than appearing immediately after inflammatory insults [

10]. This distinguishes the histamine-H2 receptor pathway from other stimuli like ET-1, which acutely triggers calcium influx through ORAI1 channels.

Mechanistically, this SOCE remodeling may involve H2 receptor-mediated upregulation of ORAI1 or STIM1 protein expression, or enhanced trafficking of these proteins to the plasma membrane. Notably, STIM1 has been shown to directly activate adenylyl cyclase 6 (AC6) in melanocytes, creating a positive feedback loop that amplifies cAMP signaling [

25]. Thus, the histamine-induced enhancement of SOCE likely leads to increased cAMP accumulation, further upregulating the MITF axis and driving the excessive melanin production characteristic of PIH. Future investigations using Western blot analysis to quantify ORAI1 and STIM1 protein levels after chronic exposure will be essential to further validate this remodeling hypothesis.

The pivotal role of ORAI1 in melanogenesis has been increasingly recognized across diverse stimuli. Previous studies have shown that ORAI1 mediates ET-1-induced pigmentation, where its knockdown significantly reduces both calcium influx and tyrosinase activity [

22]. Similarly, ORAI1 inhibition has been shown to block UV-induced melanogenesis, with ORAI1-targeting agents suppressing melanin production by up to 60% [

24]. Interestingly, recent reports on echinochrome A (Ech A) further support this paradigm; Ech A not only downregulates the cAMP/PKA-CREB-MITF cascade but also potently inhibits ORAI1/STIM1 channels at similar concentrations [

26,

27]. This dual inhibitory action suggests a synergistic interplay between cAMP and calcium signaling pathways, a concept that aligns with our identification of the ORAI1-STIM1 complex as a central hub for histamine-induced signaling.

Our findings extend these observations by identifying histamine as a novel upstream stimulus that converges on the ORAI1-STIM1 machinery. However, we reveal a distinct temporal signature: while ET-1 and UV typically trigger immediate calcium influx through direct channel activation, chronic histamine exposure enhances SOCE capacity without eliciting an acute response [

22]. This suggests that different melanogenic stimuli engage ORAI1 through specialized mechanisms either through rapid gating or through the functional remodeling we observed here. Despite these upstream differences, the convergence of multiple pathways (UV, ET-1, and histamine) on ORAI1-mediated calcium entry marks it as a critical and universal step in melanogenesis. From a clinical perspective, this makes ORAI1 an ideal therapeutic target. Unlike conventional tyrosinase inhibitors that often interfere with basal pigmentation [

28], ORAI1-targeted therapy could specifically suppress stimulus-induced hypermelanosis while potentially preserving the skin's natural baseline coloration.

While this study provides compelling evidence for ORAI1’s role in both B16F10 cells and NHEMs, certain aspects warrant further investigation. Although we focused on the functional outcomes of melanin content, future studies mapping the precise temporal expression dynamics of MITF and tyrosinase proteins would complement our current findings. Furthermore, while two-dimensional cultures established the fundamental signaling logic, validating these pathways in three-dimensional skin models or in vivo PIH models will be essential to account for the complex interactions within the skin microenvironment.

Ultimately, the development of topically applicable ORAI1 inhibitors presents a promising translational opportunity. By targeting the ORAI1-STIM1 complex locally, it may be possible to mitigate inflammatory hyperpigmentation with high specificity and minimal systemic exposure. These findings establish a strong foundation for advancing ORAI1-targeted interventions as a next-generation treatment strategy for PIH and related pigmentary disorders.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Chemicals and Cell Lines

Histamine, pyrilamine, famotidine, thioperamine, BTP-2, synta-66, BAPTA-AM, kojic acid, and thapsigargin were procured from Sigma. Both the B16F10 cell line and Normal Human Epithelial primary Melanocytes (NHEMs) were purchased from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) (Manassas, VA, USA).

4.2. Cell Culture

Experiments were performed on B16F10 and NHEM cells. B16F10 were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM, Welgene Inc., Daegu, Korea) with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Welgene Inc.) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (P/S, Life technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA) at 37oC in a 5% CO2 incubator. Melanoma cells with passage 5-15 were used. NHEMs were cultured in dermal cell basal medium (ATCC, Cat# PCS-200-030, Manassas, VA, USA) supplemented with adult human melanocyte growth supplement (ATCC, Cat# PCS-200-013, Manassas, VA, USA) and Penicillin-Streptomycin-Amphotericin B (ATCC, Cat# PCS-999-002, Manassas, VA, USA) at 37oC in a 5% CO2 incubator. The primary melanocytes with passage 2-6 were used.

4.3. Cell Viability

B16F10 cells were cultured in 96-well plate with density 1 x 104 cells per well. After one day, various concentrations of Histamine were added. Following 24, 48, and 72 hours of incubation, cells were exposed to 10 uM CCK-8 (Dojindo Laboratories, Japan) for 120 minutes. The optical density (OD) was measured at 450 nm and normalized to the value of blank and control cells to calculate viability.

4.4. Melanin Content Measurement

B16F10 cells were seeded into a 6-well plate at a density of 1 x 105 cells per well. After culturing overnight, cells were treated with various concentrations of histamine with or without other chemicals for 48 hours. NHEMs were seeded into 100 mm plates at a density of 1 x 106 cells per well. After culturing overnight, cells were treated with histamine 10 μM with or without other chemicals for 6 days. To maintain consistent drug exposure during this extended treatment period, the culture medium containing fresh chemicals was replaced every 48 hours.

Following treatment, cells were harvested and washed twice with phosphate buffered saline (PBS). The pelleted cells were lysed in 1N sodium hydroxide (NaOH) and then heated at 80oC for 1 h. Cell lysates were transferred to a 96-well plate, and the absorbance was measured at 405 nm using a microplate reader. Relative melanin content was normalized to total protein measured using Pierce™ BCA Protein Assay Kit.

4.5. Small Interfering RNA Transfection

B16F10 cells were seeded into a 6-well plate at a density of 1 x 105 cells per well. After culturing overnight, cells were transfected with each siRNA (100 nM) using TurboFect Transfection Reagent for 48 hours. NHEMs were seeded into 100 mm plates at a density of 1 x 106 cells per well. After culturing overnight, cells were transfected with siRNA (300 nM) using Turbofect reagent for 6 days, the medium containing siRNA was changed every 48 hours. Pools of three or five target-specific siRNA directed against ORAI1, ORAI2, ORAI3, STIM1, and STIM2 for human and mouse were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA).

4.6. Calcium Imaging

Ca2+ influx measurements were performed with B16F10 and NHEM cells. B16F10 cells were seeded into a 6-well plate at a density of 1 x 105 cells per well. After culturing overnight, cells were treated with histamine 10 μM for 48 hours. NHEMs were seeded into 100 mm plates at a density of 1 x 106 cells per well. After culturing overnight, cells were treated with histamine 10 μM for 6 days. To maintain consistent drug exposure during this extended treatment period, the culture medium containing fresh chemicals was replaced every 48 hours.

Ca2+ influx measurements were conducted in the normal Tyrode’s (NT) solution, including 145 mM NaCl, 3.6 mM KCl, 10 mM HEPES, 1 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EGTA, 5 mM glucose, and adjusted to 7.4 pH with NaOH. B16F10 and NHEM cells were incubated with Fura-2 acetoxymethyl ester (Fura-2 AM, Thermo Fisher Scientific) at 2 μM final concentration in 30 min at 37oC. Then, these cells were loaded onto 14 mm coverslips coated with poly-L-Lysine. The ORAI1 channels were activated through store depletion induced by exposure to thapsigargin 1 μM. Fura-2 AM was excited at wavelengths of 340 nm and 380 nm and collected at an emission wavelength of 510 nm. Fluorescence signal was measured by a digital system including an illuminator (pE-340 fura; CoolLED, Andover, UK) and a camera (sCMOS pco.edge 4.2; PCO, Kelheim, Germany). The 340/380 ratio was obtained every 10 s and analyzed using NIS-Element AR Version 5.00.00 (Nikon).

4.7. Statistical Analysis

The results were analysed using GraphPad Prism 8.0 (GraphPad Software, Boston, MA, USA) and Origin 2021b (MicroCal). All data are shown as the mean ± standard deviation (SD). One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by Dunnett’s post-hoc test, was used for multiple comparisons. Statistical significance was defined as p-value < 0.05.

Figure 1.

Histamine induces melanin production in melanocytes. (A) Cell viability was assessed over 72 hours following treatment with increasing concentrations of histamine (0-100 μM) in B16F10 cells. Cell density was measured by optical density (OD) and normalized to the value of day 0. (B) Representative images showing B16F10 pellets treated with histamine (0-30 μM) for 48 hours. (C) Quantification of melanin content normalized to total protein in B16F10 cells. Data are expressed as fold change relative to untreated control (0 μM). (D) Representative images of NHEM pellets showing melanin accumulation at indicated time points (days 0, 2, 4, 6, and 8) in the absence (0 μM) or presence (10 μM) of histamine. (E) Quantification of melanin content normalized to total protein over the 8-day culture period in NHEMs. Data are expressed as fold change relative to control at day 0. Data are presented as mean ± SD from three independent experiments. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by Dunnett’s post-hoc test, was used for multiple comparisons. *p < 0.05, ***p < 0.001, ns: not significant.

Figure 1.

Histamine induces melanin production in melanocytes. (A) Cell viability was assessed over 72 hours following treatment with increasing concentrations of histamine (0-100 μM) in B16F10 cells. Cell density was measured by optical density (OD) and normalized to the value of day 0. (B) Representative images showing B16F10 pellets treated with histamine (0-30 μM) for 48 hours. (C) Quantification of melanin content normalized to total protein in B16F10 cells. Data are expressed as fold change relative to untreated control (0 μM). (D) Representative images of NHEM pellets showing melanin accumulation at indicated time points (days 0, 2, 4, 6, and 8) in the absence (0 μM) or presence (10 μM) of histamine. (E) Quantification of melanin content normalized to total protein over the 8-day culture period in NHEMs. Data are expressed as fold change relative to control at day 0. Data are presented as mean ± SD from three independent experiments. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by Dunnett’s post-hoc test, was used for multiple comparisons. *p < 0.05, ***p < 0.001, ns: not significant.

Figure 2.

Histamine induces melanogenesis in melanocytes through histamine H2 receptors. (A) Representative images showing B16F10 pellets (upper) and quantification of melanin content normalized to total protein (lower). Cells were treated with vehicle control (Ctrl), histamine (His, 10 μM), or histamine in combination with selective histamine receptor antagonists: pyrilamine (H1 antagonist, 10 μM), famotidine (H2 antagonist, 10 μM), or thioperamide (H3 antagonist, 10 μM) for 48 hours. Data are expressed as fold change relative to vehicle control. (B) Representative images showing NHEM pellets (upper) and quantification of melanin content normalized to total protein (lower). Cells were treated with vehicle control (Ctrl), histamine (His, 10 μM), or histamine in combination with pyrilamine (10 μM), famotidine (10 μM), or thioperamide (10 μM) for 6 days. Data are expressed as fold change relative to vehicle control. Data are presented as mean ± SD from three independent experiments. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by Dunnett's post-hoc test, was used for multiple comparisons. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ns: not significant.

Figure 2.

Histamine induces melanogenesis in melanocytes through histamine H2 receptors. (A) Representative images showing B16F10 pellets (upper) and quantification of melanin content normalized to total protein (lower). Cells were treated with vehicle control (Ctrl), histamine (His, 10 μM), or histamine in combination with selective histamine receptor antagonists: pyrilamine (H1 antagonist, 10 μM), famotidine (H2 antagonist, 10 μM), or thioperamide (H3 antagonist, 10 μM) for 48 hours. Data are expressed as fold change relative to vehicle control. (B) Representative images showing NHEM pellets (upper) and quantification of melanin content normalized to total protein (lower). Cells were treated with vehicle control (Ctrl), histamine (His, 10 μM), or histamine in combination with pyrilamine (10 μM), famotidine (10 μM), or thioperamide (10 μM) for 6 days. Data are expressed as fold change relative to vehicle control. Data are presented as mean ± SD from three independent experiments. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by Dunnett's post-hoc test, was used for multiple comparisons. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ns: not significant.

Figure 3.

Histamine enhances store-operated calcium entry (SOCE) in melanocytes. (A) Representative trace (left) and averaged peak value (right) of cytosolic Ca²⁺ levels in response to increasing concentrations of histamine (1, 3, 10, 30, and 100 μM) in the presence of extracellular calcium (1.3 mM Ca²⁺) in B16F10 cells (n = 24 cells). (B) Representative trace (left) and averaged peak value (right) of cytosolic Ca²⁺ levels in response to increasing concentrations of histamine (1, 3, 10, 30, and 100 μM) in the presence of extracellular calcium (1.3 mM Ca²⁺) in NHEMs (n = 24 cells). (C) Representative traces (left) show SOCE in B16F10 cells pretreated with vehicle control (Ctrl, black trace, n = 29 cells) or histamine (His, 10 μM, blue trace, n = 16 cells) for 48 hours. Thapsigargin (Tg, 1 μM) was applied in the absence of extracellular calcium (0 Ca²⁺) to deplete intracellular Ca²⁺ stores, followed by the presence of extracellular calcium (1.3 mM Ca²⁺) to measure SOCE. Quantitative SOCE amplitude (ΔF340/F380) (right) shows the change in cytosolic calcium level before and after the presence of extracellular calcium. (D) Representative traces show SOCE in NHEMs pretreated with vehicle control (Ctrl, left, n = 19 cells) or histamine (His, 10 μM, n = 18 cells) (middle) for 6 days. Tg (1 μM) was applied in the absence of extracellular calcium (0 Ca²⁺), followed by the presence of extracellular calcium (1.3 mM Ca²⁺). Quantitative SOCE amplitude (ΔF340/F380) (right) shows the change in cytosolic calcium level before and after the presence of extracellular calcium. Data are presented as mean ± SD. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by Dunnett's post-hoc test, was used for multiple comparisons. Student's t-test was used for comparison between two groups. **p< 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ns: not significant.

Figure 3.

Histamine enhances store-operated calcium entry (SOCE) in melanocytes. (A) Representative trace (left) and averaged peak value (right) of cytosolic Ca²⁺ levels in response to increasing concentrations of histamine (1, 3, 10, 30, and 100 μM) in the presence of extracellular calcium (1.3 mM Ca²⁺) in B16F10 cells (n = 24 cells). (B) Representative trace (left) and averaged peak value (right) of cytosolic Ca²⁺ levels in response to increasing concentrations of histamine (1, 3, 10, 30, and 100 μM) in the presence of extracellular calcium (1.3 mM Ca²⁺) in NHEMs (n = 24 cells). (C) Representative traces (left) show SOCE in B16F10 cells pretreated with vehicle control (Ctrl, black trace, n = 29 cells) or histamine (His, 10 μM, blue trace, n = 16 cells) for 48 hours. Thapsigargin (Tg, 1 μM) was applied in the absence of extracellular calcium (0 Ca²⁺) to deplete intracellular Ca²⁺ stores, followed by the presence of extracellular calcium (1.3 mM Ca²⁺) to measure SOCE. Quantitative SOCE amplitude (ΔF340/F380) (right) shows the change in cytosolic calcium level before and after the presence of extracellular calcium. (D) Representative traces show SOCE in NHEMs pretreated with vehicle control (Ctrl, left, n = 19 cells) or histamine (His, 10 μM, n = 18 cells) (middle) for 6 days. Tg (1 μM) was applied in the absence of extracellular calcium (0 Ca²⁺), followed by the presence of extracellular calcium (1.3 mM Ca²⁺). Quantitative SOCE amplitude (ΔF340/F380) (right) shows the change in cytosolic calcium level before and after the presence of extracellular calcium. Data are presented as mean ± SD. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by Dunnett's post-hoc test, was used for multiple comparisons. Student's t-test was used for comparison between two groups. **p< 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ns: not significant.

Figure 4.

Intracellular calcium is required for histamine-induced melanogenesis. (A) Representative images showing B16F10 pellets (upper) and quantification of melanin content normalized to total protein (lower). Cells were treated with vehicle control (Ctrl), histamine (His, 10 μM), histamine and BAPTA-AM (intracellular calcium chelator, 10 μM) or Kojic acid (tyrosynase inhibitor, 50 μM) for 48 hours. Data are expressed as fold change relative to vehicle control. (B) Representative images showing NHEM pellets (upper) and quantification of melanin content normalized to total protein (lower). Cells were treated with vehicle control (Ctrl), histamine (His, 10 μM), histamine and BAPTA-AM (10 μM), or KA (50 μM) for 6 days. Data are expressed as fold change relative to vehicle control. Data are presented as mean ± SD from three independent experiments. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by Dunnett's post-hoc test, was used for multiple comparisons. ***p < 0.001.

Figure 4.

Intracellular calcium is required for histamine-induced melanogenesis. (A) Representative images showing B16F10 pellets (upper) and quantification of melanin content normalized to total protein (lower). Cells were treated with vehicle control (Ctrl), histamine (His, 10 μM), histamine and BAPTA-AM (intracellular calcium chelator, 10 μM) or Kojic acid (tyrosynase inhibitor, 50 μM) for 48 hours. Data are expressed as fold change relative to vehicle control. (B) Representative images showing NHEM pellets (upper) and quantification of melanin content normalized to total protein (lower). Cells were treated with vehicle control (Ctrl), histamine (His, 10 μM), histamine and BAPTA-AM (10 μM), or KA (50 μM) for 6 days. Data are expressed as fold change relative to vehicle control. Data are presented as mean ± SD from three independent experiments. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by Dunnett's post-hoc test, was used for multiple comparisons. ***p < 0.001.

Figure 5.

ORAI1 and STIM1 are the essential molecular components of store-operated calcium entry (SOCE) in melanocytes. (A-F) Representative traces showing SOCE in NHEMs. Cells were transfected with siRNAs targeting ORAI1 (siORAI1, n = 36), ORAI2 (siORAI2, n = 21), ORAI3 (siORAI3, n = 27), STIM1 (siSTIM1, n = 37), or STIM2 (siSTIM2, n = 24) for 6 days. Thapsigargin (Tg, 1 μM) was applied in the absence of extracellular calcium (0 Ca²⁺) to deplete intracellular Ca²⁺ stores, followed by the presence of extracellular calcium (1.3 mM Ca²⁺) to measure SOCE. (G) Quantitative SOCE amplitude (ΔF340/F380) shows the change in cytosolic calcium level before and after the presence of extracellular calcium. Data are presented as mean ± SD. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by Dunnett's post-hoc test, was used for multiple comparisons. ***p < 0.001, ns: not significant.

Figure 5.

ORAI1 and STIM1 are the essential molecular components of store-operated calcium entry (SOCE) in melanocytes. (A-F) Representative traces showing SOCE in NHEMs. Cells were transfected with siRNAs targeting ORAI1 (siORAI1, n = 36), ORAI2 (siORAI2, n = 21), ORAI3 (siORAI3, n = 27), STIM1 (siSTIM1, n = 37), or STIM2 (siSTIM2, n = 24) for 6 days. Thapsigargin (Tg, 1 μM) was applied in the absence of extracellular calcium (0 Ca²⁺) to deplete intracellular Ca²⁺ stores, followed by the presence of extracellular calcium (1.3 mM Ca²⁺) to measure SOCE. (G) Quantitative SOCE amplitude (ΔF340/F380) shows the change in cytosolic calcium level before and after the presence of extracellular calcium. Data are presented as mean ± SD. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by Dunnett's post-hoc test, was used for multiple comparisons. ***p < 0.001, ns: not significant.

Figure 6.

Histamine-induced melanogenesis is specifically mediated through the ORAI1-STIM1 dependent SOCE pathway. (A) Representative images showing B16F10 pellets (upper) and quantification of melanin content normalized to total protein (lower). Cells were treated with vehicle control (Ctrl), histamine (His, 10 μM), histamine and BTP-2 (CRAC channel inhibitor, 5 μM), Synta-66 (ORAI1 inhibitor, 10 μM), or Kojic acid (KA, tyrosinase inhibitor, 50 μM) for 48 hours. Data are expressed as fold change relative to vehicle control. (B) Representative images of NHEM pellets (upper) and quantification of melanin content normalized to total protein (lower). Cells were treated with vehicle control (Ctrl), histamine (His, 10 μM), histamine and BTP-2 (5 μM), Synta-66 (10 μM), or KA (50 μM) for 6 days. Data are expressed as fold change relative to vehicle control. (C) Representative images showing B16F10 pellets (upper) and quantification of melanin content normalized to total protein (lower). Cells were treated with histamine (His, 10 μM) and transfected with siRNAs targeting Orai1 (siOrai1), Orai2 (siOrai2), Orai3 (siOrai3), Stim (siStim1), or Stim2 (siStim2) for 48 hours. Data are expressed as fold change relative to vehicle control. (D) Representative images showing NHEM pellets (upper) and quantification of melanin content normalized to total protein (lower). Cells were treated with histamine (His, 10 μM) and transfected with siRNAs targeting ORAI1 (siORAI1), ORAI2 (siORAI2), ORAI3 (siORAI3), STIM1 (siSTIM1), or STIM2 (siSTIM2) for 6 days. Data are expressed as fold change relative to vehicle control. Data are presented as mean ± SD from three independent experiments. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by Dunnett's post-hoc test, was used for multiple comparisons. ***p < 0.001, ns: not significant.

Figure 6.

Histamine-induced melanogenesis is specifically mediated through the ORAI1-STIM1 dependent SOCE pathway. (A) Representative images showing B16F10 pellets (upper) and quantification of melanin content normalized to total protein (lower). Cells were treated with vehicle control (Ctrl), histamine (His, 10 μM), histamine and BTP-2 (CRAC channel inhibitor, 5 μM), Synta-66 (ORAI1 inhibitor, 10 μM), or Kojic acid (KA, tyrosinase inhibitor, 50 μM) for 48 hours. Data are expressed as fold change relative to vehicle control. (B) Representative images of NHEM pellets (upper) and quantification of melanin content normalized to total protein (lower). Cells were treated with vehicle control (Ctrl), histamine (His, 10 μM), histamine and BTP-2 (5 μM), Synta-66 (10 μM), or KA (50 μM) for 6 days. Data are expressed as fold change relative to vehicle control. (C) Representative images showing B16F10 pellets (upper) and quantification of melanin content normalized to total protein (lower). Cells were treated with histamine (His, 10 μM) and transfected with siRNAs targeting Orai1 (siOrai1), Orai2 (siOrai2), Orai3 (siOrai3), Stim (siStim1), or Stim2 (siStim2) for 48 hours. Data are expressed as fold change relative to vehicle control. (D) Representative images showing NHEM pellets (upper) and quantification of melanin content normalized to total protein (lower). Cells were treated with histamine (His, 10 μM) and transfected with siRNAs targeting ORAI1 (siORAI1), ORAI2 (siORAI2), ORAI3 (siORAI3), STIM1 (siSTIM1), or STIM2 (siSTIM2) for 6 days. Data are expressed as fold change relative to vehicle control. Data are presented as mean ± SD from three independent experiments. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by Dunnett's post-hoc test, was used for multiple comparisons. ***p < 0.001, ns: not significant.