I. Introduction

Near Field Communication (NFC) is a wireless communication technology that will allow for new applications on mobile devices, e.g., smartphones

1.

NFC is an extension of the RFID protocol, which means it allows mobile devices to assume the capabilities of an RFID tag or reader and, therefore, utilize a radio frequency (RF) connection interactively

2. RFID tags consist of an integrated circuit (microchip) that stores and processes data (e.g., name, fingerprint, or product number) and can transmit and receive information wirelessly. These tiny chips can be embedded in products such as bar code stickers, public transport tickets, and passports.

NFC enables the creation of a Wireless Personal Area Network (WPAN) between mobile handsets and RFID hardware. This will allow a mobile device to communicate wirelessly with other NFC-capable devices, such as the user’s own RFID cards, another smartphone, a payment terminal, a so-called `smart poster’ from which users can receive extra information or an access control terminal. Having NFC functionality available in a mobile handset would allow for use cases including payment, electronic banking, access control, exchange of digital coupons or interactive advertising.

RFID-based applications for access control and public transport ticketing systems are already in place and are likely to make the transition to NFC-enabled mobile phones. In my opinion, this transition warrants some security research. NFC systems require security features (similar to those relied upon in RFID technology) in order to qualify as a trusted platform. This will allow NFC to meet the security criteria for applications where assets of value are exchanged. One of the required features is, e.g., the ability to run signed code, which can be remotely updated. A hardware component that provides the required features is called a Secure Element (SE) and lies at the core of the security architecture that NFC applications build on. Access to the SE is regulated by a Trusted Service Manager (TSM) who holds the private key necessary to update applications running on it.

Running trusted code on mobile devices has been deemed feasible, but widespread adoption of the technology is hampered by the limitations the payment card industry and telecom providers impose on their products. The payment card industry’s current standards dictate that their cards may not be modified after production, and Mobile Network Operators (MNOs) have similar provisions regarding the SIM cards they issue.

A. Motivation

Our aim is to present a succinct overview of current research on NFC technology with an emphasis on the security risks potentially involved, and possible countermeasures.

In this paper, I will describe various applications of NFC technology, see Section II and show how these relate to different NFC architectures, see Section III. In Section IV, I will also summarize some of the known vulnerabilities surrounding NFC applications and investigate what possible countermeasures exist. Section V will describe what other applications NFC might have in the near future and what problems might occur during the implementation of NFC. I hypothesize that most new vulnerabilities will be found in applications built on top of NFC systems rather than in the NFC architecture itself. I envision that vendors might try to apply existing business rules to this new technology while they do not fully understand the risks associated with it, which might result in inadequate security measures being taken. In the conclusion, see Section VI, I will answer my research question and hypothesis.

II. Applications

While NFC is an emerging technology, some areas in which it is likely to be applied can already be identified. Various parties throughout the areas of public transport [

1], advertising [

2], access control [

3] and banking [

4,

5] have expressed interest in employing NFC technology.

For illustrative purposes, a few applications in which NFC can be used are mentioned below.

A. Public Transport

Public transport companies in the Netherlands have largely adopted RFID technology for their electronic ticketing system through infrastructure provider

Trans Link Systems (TLS). TLS was created as a joint venture between Dutch public transport companies to realize an electronic payment system for their services. They have also been investigating the feasibility of mobile phone-based payment applications using NFC. [

6]

Support for NFC-enabled devices in TLS’s system could improve user experience by giving users the option to check or increase the balance of their electronic ticket account at any given time, alleviating the often-heard complaint of currently only being able to do so at (most) train stations.

The use of NFC technology for electronic ticketing in public transport is currently considered unfeasible by TLS because it would require users to own an NFC-enabled handset, devices which so far have no significant market penetration in the Netherlands. Also, the relatively high cost of an NFC-enabled phone, as well as the requirement to keep the device powered on during the length of a trip, are aspects of NFC that go against TLS’s aim for a low threshold in using their electronic ticket system. TLS is still investigating the possibility of adopting NFC technology as an alternative payment method in the future. [

1]

B. Payment

In the summer of 2004, Japanese telecommunications provider

NTT DoCoMo initiated wide deployment of RFID technology for payment applications in Japan, where now virtually every issuer of payment cards supports its trademark

Osaifu-Keitai (`mobile wallet’) system. Osaifu-Keitai is based on the

FeliCa RFID chip developed by

Sony and is interoperable with

FeliCa RFID applications such as the

Suica public transport card and the

Edy electronic payment card. [

7]

With the ability to directly transfer data between two parties, NFC technology might come to be used as a medium for peer-to-peer electronic payments. This concept has been explored in mFerio, a proof of concept peer-to-peer mobile payment system that was designed to be as fast and easy to learn and use and to be as available as cash. The proposed system should also improve accuracy and speed while still meeting security criteria like transaction integrity, anonymity, tamper-resistance, impossibility to replicate, and theft resilience.

In

mFerio, the

Secure Element (SE) contains the electronic cash and personal details of the user, which by design will not be accessible by unauthorized users if the SE is hardware protected [

8].

Another possibility is to create an offline payment system with the use of cryptographically signed vouchers in a

Public Key Infrastructure. [

9] In this scheme, an

Issuer can distribute so-called `eVouchers’ to

Beneficiaries via SMS. Beneficiaries can then exchange vouchers amongst themselves or transfer an eVoucher to an

Affiliate’s payment terminal to exchange it for services or goods using an applet running on the Secure Element. The eVoucher issuer holds two RSA keys: one is used for signing (eVouchers and certificates used in affiliate terminals and user devices), and the other is used to encrypt communication to these devices (which can be verified using the aforementioned signing keys). The client’s eVoucher applet, as well as the affiliate payment terminals, also holds an RSA keypair and a certificate signed by the issuer, providing the means for mutual authentication between either two of the three parties involved.

Users are able to check the balance, history, and expiration date of the eVouchers they hold.

The Secure Element will only accept software from an issuer, which will have the private key to authenticate to the SE. The SE will store the eVouchers and also encrypt them if a user decides to send them to another user. [

10]

C. Advertisement

Advertisement is another area in which NFC can be used. By equipping advertisement media (e.g., billboards, flyers, posters) with an NFC/RFID tag, users can receive the details of a product immediately on their mobile phones. For example, by supplying the tag with a URL, a user can immediately visit a website and take further action there, e.g., sign up or fill in a form. As I will see later on, this can create a security problem for a user that is unaware. [

2,

11]

D. Access Control

It is also possible to use NFC to gain access to a certain area, e.g., a building or room. The company

Nedap Healthcare developed an application for caretakers in the home care industry. By using an NFC-enabled phone, the caretaker can gain access to the house of the client. Upon arrival and leaving, the caretaker holds the phone next to the membership card of the client, which will register the visit of the caretaker and give care. [

12,

13]

E. Bluetooth Bootstrapping

Wireless Personal Area Network (WPAN) technology is already widely available in mobile devices in the form of Bluetooth.

Bluetooth uses an interactive login to set up a connection between devices, which means that both parties have to type in a key. Establishing a connection between devices (a process called `pairing’ in Bluetooth terminology) can be made simpler by making use of NFC, relying on the close proximity required to set up a connection. Using this principle of required proximity, NFC can be used to `bootstrap’ a Bluetooth pairing between devices by simply touching the devices and confirming the connection to be established, as opposed to more complex user interface interactions traditionally required for this process. [

14]

III. System Architecture

With the development of mobile payment applications comes the requirement to ensure the security of the financial assets involved. An architecture for the application of mobile devices for `electronic cash’ must provide a means to authenticate transactions before authorizing their execution, whether that be online or offline.

Traditional mechanisms of authenticating payment transactions in electronic banking rely on verification of the data stored on the magnetic stripe and verification of the client’s signature on the card by visual inspection. Transactions can be authenticated more securely by using a cryptographic solution relying on Integrated Circuit Cards.

Integrated Circuit Cards (ICCs), commonly known as smart cards or chip cards, are cards that contain an integrated circuit that can communicate to the outside world via contact points on the card. The microchips embedded in these cards can be used to cryptographically sign data using a preconfigured secret key that is contained within the chip. [

15,

16] The chips in smart cards are designed to minimize the risk of an attacker extracting the secret key it holds. Smart cards can be issued with various anti-tampering mechanisms, adding to the intrinsic tamper resistance of the chip due to its small scale. [

17] Europay, Mastercard, and Visa have jointly designed the EMV standard for smart card interoperability, describing a secure means of transaction authentication using smart cards. The enhanced security provided by the EMV system has effected a liability shift where the non-EMV-compliant party can be held liable for any fraud committed. [

18]

A similar application of smart cards can be found in mobile telephony networks. Worldwide, most mobile telephones make use of the

Global System for Mobile Communications (GSM) system. The GSM standard already provides a mechanism for authentication to the network by means of a smart card, albeit in a different form factor, called a

Universal Integrated Circuit Card (UICC). In GSM networks, the UICC is running a

Subscriber Identify Module (SIM) application, which provides a mobile handset access to the encryption routines required for authentication on the network while the required secret key remains stored securely inside.

3

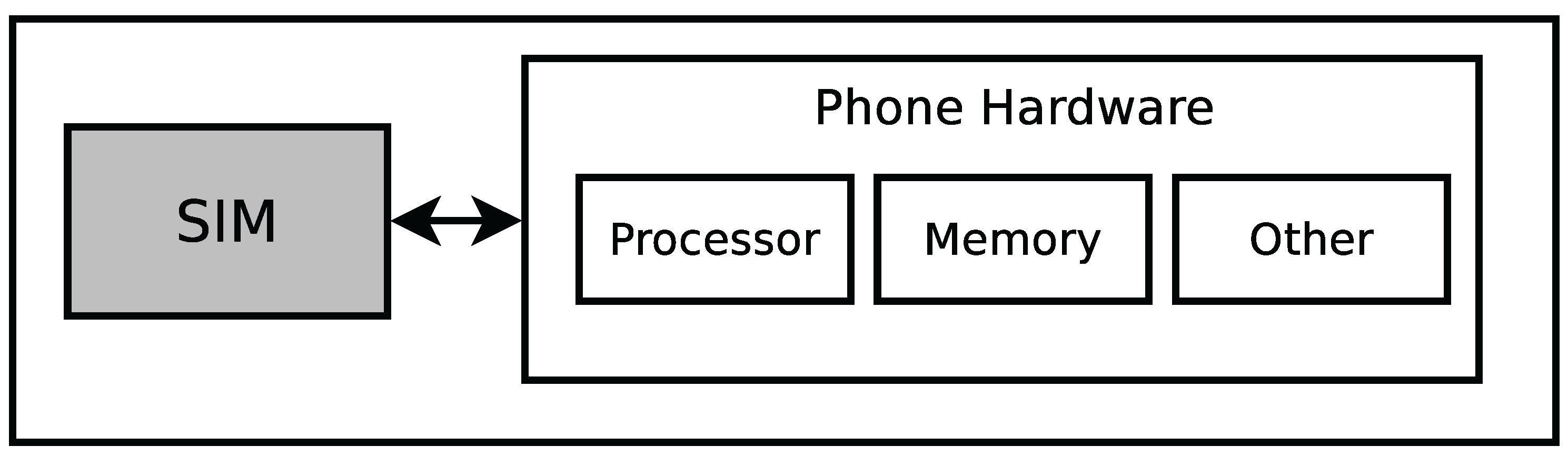

Figure 1.

A UICC (SIM) card, as used in GSM, holds the Mobile Network Operator’s secret key.

Figure 1.

A UICC (SIM) card, as used in GSM, holds the Mobile Network Operator’s secret key.

These types of cards, also known as SIM cards, remain property of the Mobile Network Operator (MNO) after distribution, much like a bank card or passport, which remains the property of their respective issuers. The contents of the card may normally not be modified by third parties. Due to this, the current generation of mobile devices lacks a common infrastructure for third parties to make use of such a secure computation platform for their own applications.

A. Secure Elements

Just like SIM cards and RFID cards, NFC-enabled handsets require a secure storage and processing module to be included in their design, as conventional storage on and operation of mobile devices is liable to tampering by the user or a malicious third party.

Secure storage for NFC applications similar to that provided by smart cards has been implemented in the

Secure Element (SE) architecture. The software on the SEs can be updated over the air by a

Trusted Services Manager (TSM), provided the TSM’s certificate is trusted by it. Several possible configurations proposed by

GlobalPlatform, the industry forum for smart card infrastructure development, are outlined below. [

19,

20]

- 1)

-

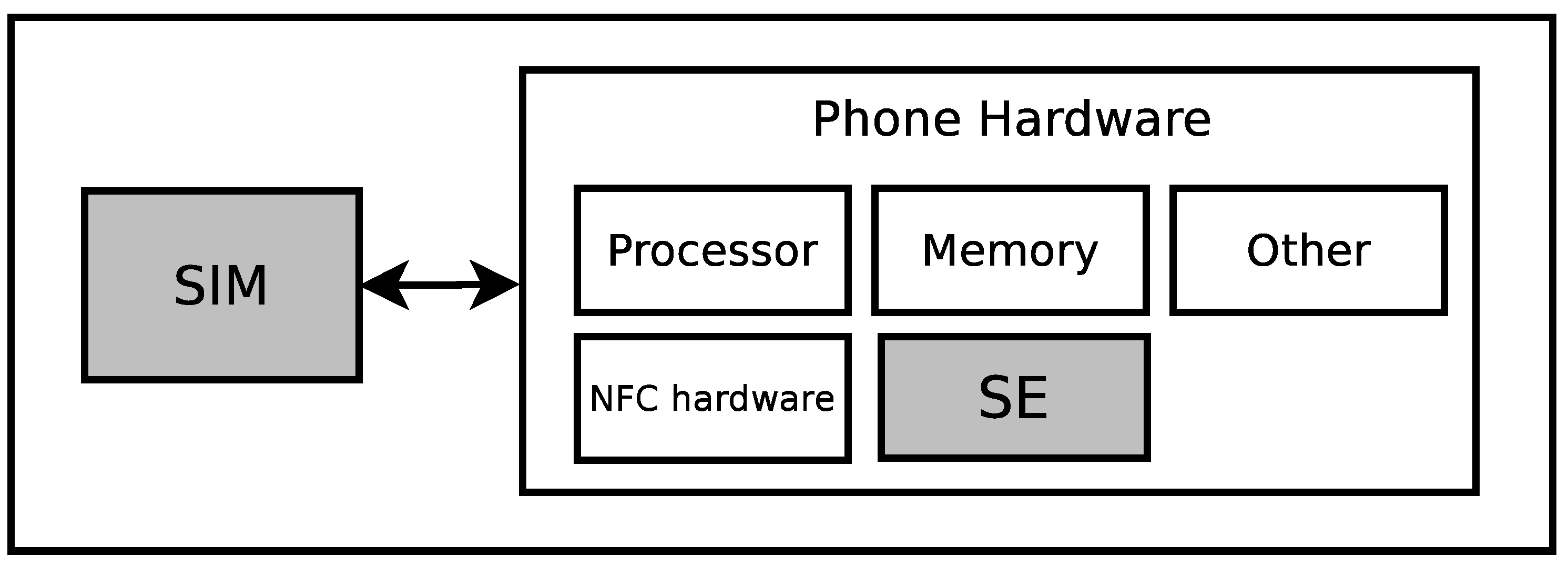

One option would be to integrate the SE into the handset hardware directly. This works for the intended cryptographic use but limits the device to communicate with the services using its pre-programmed certificates unless it is capable of securely updating itself with new certificates.

The handset hardware consists of the usual components like a processor, memory and possibly others, but also the hardware to provide NFC features and an embedded Secure Element. The downside to this design is that the data contained in the SE is not easily portable to a new NFC device.

- 2)

-

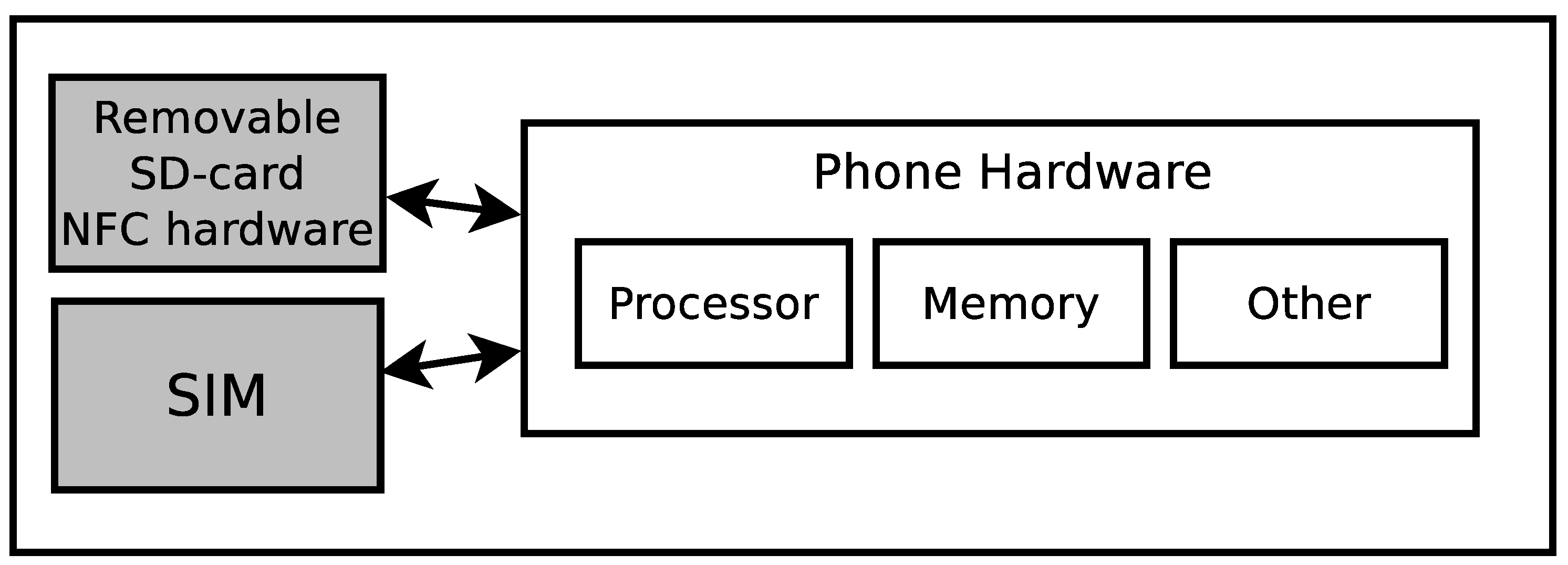

Another option is a flash memory card like a

Secure Digital (SD) card, which houses all the hardware needed to enable NFC and also the Secure Element, as depicted in

Figure 2.

In this configuration, a third party can issue an SD card to its customers, which provides NFC functionality without relying on any aspect of the handset to handle confidential data. If the user wishes to use applications from several third parties, they need SD cards from all of those parties. This can be a downside because the user has to switch the SD card if they want to use a different application.

- 3)

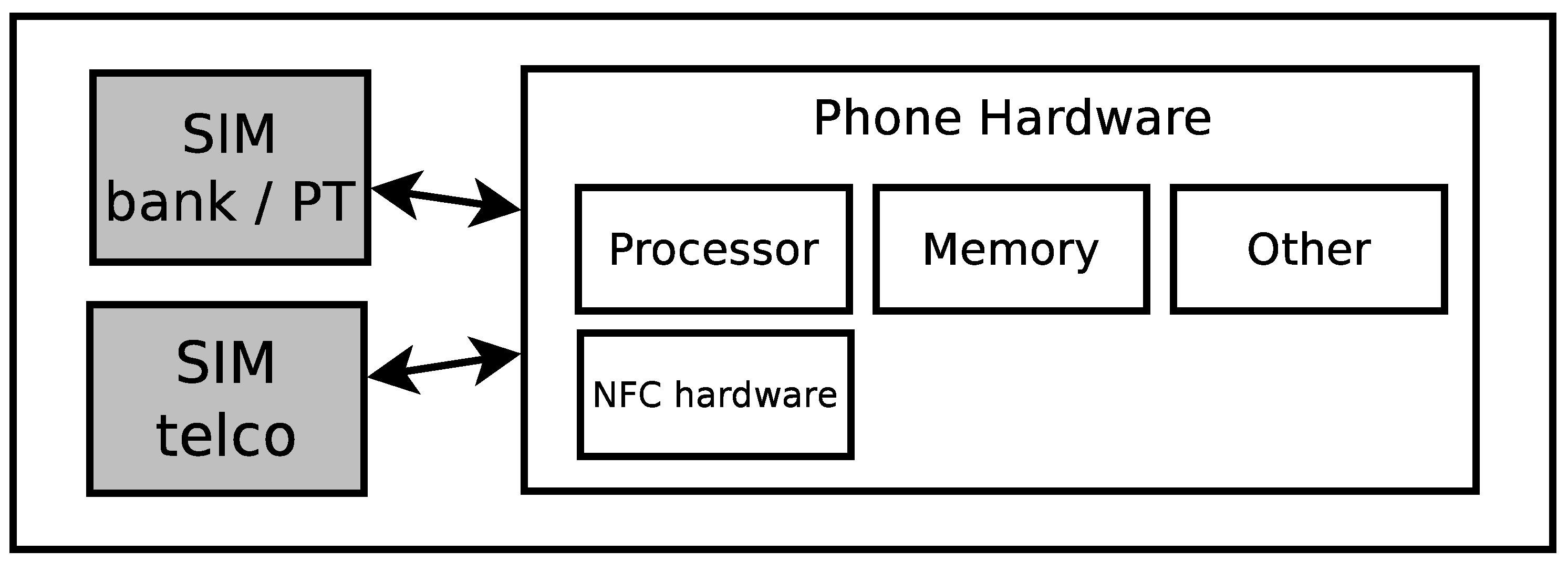

Related to the above architecture is the one depicted in

Figure 3. Here, the architecture consists of a handset with multiple UICC slots. In this design, various applications have access to their own UICC, which takes on the role of an SE. This way, applications from different providers can coexist on the handset without the need for them to trust one another or a TSM operating on their behalf.

- 4)

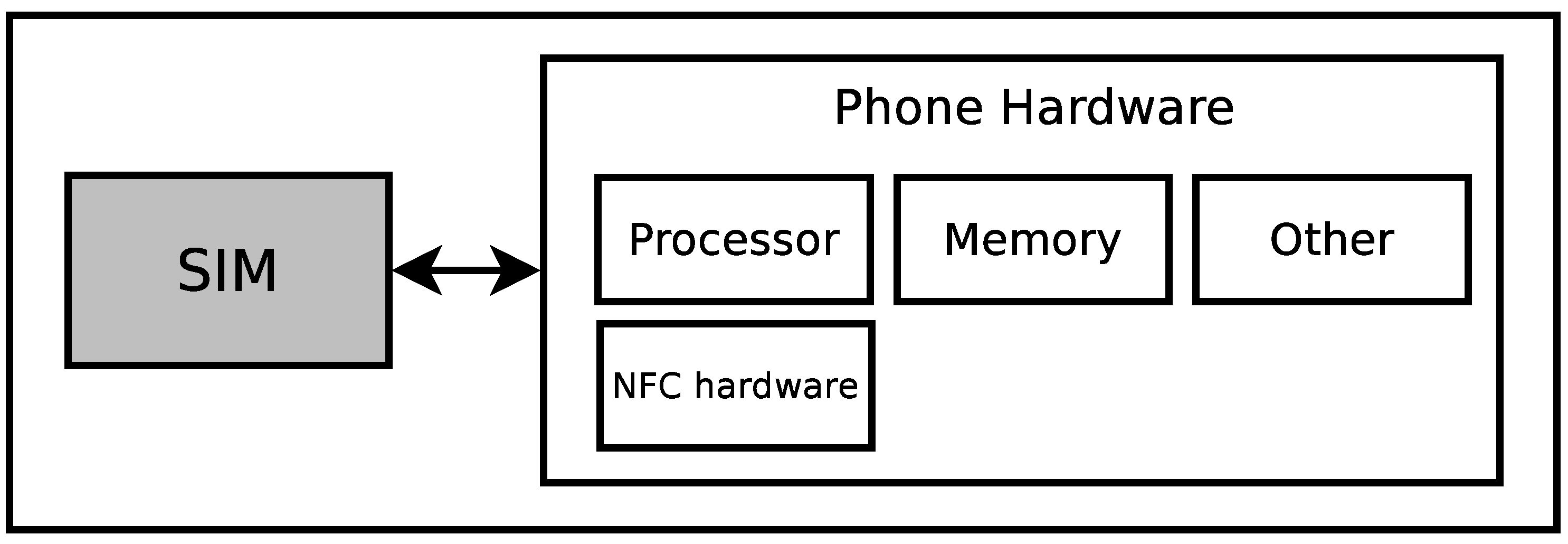

It is also possible to split the resources available on the SE between various parties, granted they trust each other to not abuse the privilege of being able to access one another’s data. This sharing of resources is possible because smart cards, in general, are becoming more powerful. This makes two different architectures possible. The first one, as pictured in

Figure 4, uses the SIM card as a Secure Element. In this design, the handset will include the NFC communication hardware and utilize a UICC (SIM card) with applications from the Mobile Network Operator and applications from various third parties chosen by the user, e.g., a bank for payment and a public transport company. The second option resembles a combination of the first one and the one with the SD card architecture. Here, a SIM card has all the hardware needed to make NFC possible, and it also acts as a Secure Element (see

Figure 5). Like in the first option, the resources of the SIM card will be split among the involved parties.

IV. Security Research

While consumers might see NFC applications as gadgets that will make their lives easier, this development towards contactless payment systems has raised questions from security researchers.

Because NFC will be used in payment and access control, it should be assumed that attackers will try to exploit this technology. NFC’s security features have been the subject of research, and some attacks have been found possible, which will be summarized below. Because NFC will be used in payment and access control, it should be assumed that attackers will try to exploit this technology for their own gain.

A. Relay Attacks

RFID, a direct ancestor of NFC, is prone to relay attacks. A relay attack is a combination of a man-in-the-middle

4 and replay attack

5. The goal is that the attacker will gain something, but the victim will lose something (e.g., the attacker will get a product from a retailer, but the victim is the one who is paying).

To achieve a relay attack, an attacker will need a device that emulates an RFID card (called the

ghost) and a device that acts as an RFID reader (called the

leech). The

ghost will be used to communicate with a genuine reader, and the

leech will be used to communicate with a genuine card (the victim). The attacker must trick the user into making a legitimate purchase at the

leech terminal and have the devices set up in such a way that they operate at a much larger distance than the normal operational distance of 10 centimeters so that the attack will go unnoticed. [

21]

For example, with this attack, it could be possible to gain access to public transport. The check-in gate will communicate with the ghost, which will relay the communication to the leech, which will then relay it to the victim and vice versa. The check-in gate will conclude it is communicating with the victim, but because the attacker is closer to the gate than the victim, he will gain access first and the victim will pay.

B. Countermeasures Against Relay Attacks

There are three possible countermeasures: a Faraday cage, interactive confirmation of a transaction by the user, or two-factor authentication. A Faraday cage

6 will block all RF communication so an attacker can not make contact with the device.

This is not a feasible countermeasure for a mobile phone because it will not have any connectivity.

The other alternatives affect a relatively slight decrease in usability, namely because there will be an extra step for a user to switch on NFC features. Interactive confirmation to activate the connection will prevent the user from accidentally making a transaction.

By implementing this, it will not be possible for an attacker to stealthily communicate with a target phone at all times because users will actually be notified of all connections to be established.

With two-factor authentication, the user will be asked to present something they know to uniquely identify them (e.g., a password or PIN code or a shared secret that is agreed upon verbally between users).

If the user is aware that the NFC connection is not necessary (because he is not near a payment terminal) and declines or does not type the password this attack can prevented.[

21]

Overall the relay attack on NFC will have lower feasibility than relay attacks on RFID cards, precisely because the user can be presented with the option of accepting or declining transactions.

Another countermeasure against a relay attack is the use of a distance bounding protocol. Using a distance bounding protocol, it is possible for an NFC-enabled mobile device (Verifier) to check if the payment terminal or access gate (Prover) is within a set distance. To achieve this, the Verifier sends a challenge to the Prover which has to solve the challenge before the Verifier will allow it to engage in further communication. This countermeasure works on the principle that any latency incurred in transmitting the challenge to a Verifier must not exceed a certain threshold, ensuring that both communicating parties are within the allowed range of each other.

The Verifier will measure the round-trip time between the sending of the challenge and the reception of a valid reply from the Prover. By subtracting a typical Prover’s processing time from the round-trip time, the distance between the two devices can be roughly determined. This means that the Prover can not easily fake being closer to the Verifier than it really is.

C. Malware Distribution

Smart poster technology can be used to distribute malware. It has been proven to be possible to mislead a user to visit a malicious website through a modified RFID tag using a technique called

Smart poster URI spoofing, which exploits a vulnerability in a user’s browser. To exploit such a vulnerability, an attacker would target a user known to be running a vulnerable browser with a specially crafted message that contains a malicious

Uniform Resource Identifier (URI) that is disguised to look innocent. By using whitespace characters like space, tab, and new line characters in the transmitted URI, it can be made to appear to identify a different resource than it actually does when presented to the user. The URI addressing malicious content is therefore not shown to the user, but the user is still directed thereupon to visit the innocent-looking link communicated by the smart poster. [

11]

The different services a user can be directed to through URI spoofing depend on the platform under attack but could include the World Wide Web, file sharing, instant messaging, (internet) telephony, or text messaging.

It is also possible to hide and spread a computer worm that propagates via NFC. When a phone infected by such a worm is in proximity to an RFID tag, it will attempt to overwrite the data contained in the tag with a malicious URL where a copy of the worm is located, likely disguised as benign software. If this effort is successful, users who read the tag after its infection will be directed to said website, where they will be tricked into downloading and installing a copy of the worm. [

22]

D. Countermeasures Against Malware Distribution

This vector is similar to other networking attacks, the best defense against these kinds of attacks is user vigilance in spotting malicious messages. These attacks can possibly be mitigated by taking preventative measures in the client software.

E. Differential Analysis Attacks

Differential analysis attacks are a class of side-channel attacks where signal fluctuations (like power usage and electromagnetic radiation) in the system are collected and statistically analyzed to yield information about the key or plaintext.

A side channel attack is based on information that can be collected by analyzing the physical operation of a cryptographic system (cryptosystem), e.g., by analyzing the power usage, electromagnetic radiation leakage, or timing of a cryptosystem. It is possible to prevent this from happening by implementing random behavior to skew measurements, adding extra shielding, or filtering inputs and outputs.

DPA attacks are a common problem in devices where the cryptosystem is designed to be small, cheap, and have low power usage (like the Secure Elements used in NFC). With DPA, the power consumption is measured to extract information about the workings of the cryptosystem. When the cryptosystem is processing, the power usage will vary during the different operations. This information can be statistically analyzed to determine the encryption key or plaintext, or it can give information about the key, which can be used to aid a different attack (such as a statistical brute-force attack).

Differential analysis of signals can also be applied to electromagnetic radiation, which is called Differential Frequency Analysis (DFA). Information about the cryptosystem can be collected from the RF noise given off by the electronic signals representing the data traveling to and from the Secure Element and memory.

Many measurements of these variations might be necessary to produce the entire key because of noise (e.g., inaccuracies, outside influence, intentional random fluctuations) that is collected during measurements.By aligning the measurements, an attacker can compare data on single points of interest. By averaging the collected data, the usable signal can amplified, and the noise is filtered out.

Other kinds of statistical information about the cryptosystem can be collected by techniques called fuzzing and glitching, where, respectively, some bits of input are changed, or the function of the device is otherwise tampered with in order to detect statistical anomalies by correlating these changes with changes measured from the cryptosystem’s output(s). These techniques can also be repeated, and the resulting data can be statistically analyzed to get the key.

F. Countermeasures Against Differential Power Analysis

A DPA attack is successful if enough information can be collected to retrieve the key in the cryptosystem to retrieve the plaintext. By increasing the number of required measurements to be performed by the attacker, it will take more time to collect the information needed to retrieve the key. There are several ways to increase the number of measurements required. For example, randomly generated noise can be added to the operations of the cryptosystem, which will make it harder to filter out the signal from the noise, causing more measurements to be needed. Another way is to reduce the signal size, making it harder to pick up. If the cryptosystem is designed to self-destruct after a certain amount of operations and the number of measurements needed to retrieve the key is higher than the allowed number of operations, this adds another level of defense against an attacker retrieving the key.

Another countermeasure to prevent information from being collected is clock skipping. Normally a cryptosystem uses an external clock for its processing. With clock skipping, an internal clock is used in the cryptosystem. This will create more noise and will prevent the attacker from aligning the points of interest in the collected data and making it more difficult to identify the signal.

A countermeasure that can also be effective against DPA is, to use a random number generator to add an amount of unpredictability in the order in which the crypto operations are executed. The result is that it will be harder for the attacker to find the points of interest in the collected data, making it more difficult to extract the key. [

23]

G. Denial of Service

A denial of service attack is also possible, with the goal of rendering the service unusable. By using a tag that sends out malformed messages, taped on top of the original tag, the phone of the user will crash when he attempts to read the tag. By putting a copper wire or mesh sticker on top of a tag or a terminal, it is possible to create a small Faraday cage, preventing the terminal from sending out its RF signal or reducing the range of the signal. [

22]

H. Countermeasures Denial of Service

There are not many countermeasures that you can take to prevent an attack like this. As suggested before, preventive measures taken in client software might help dealing with malformed messages. As for Faraday cages in sticker form, only regular checking of the original equipment used, will reduce the impact.

V. Future Work

During my literature study I have come across several areas that warrant further research. One interesting application of NFC is in the healthcare system. As mentioned it is possible for caretakers to register their work activities with an NFC-enabled device, but the list of applications is longer. It is possible for RFID devices to be surgically implanted in a patient. The sensors inside such a medical tag may measure all kinds of information about a patient, like blood pressure, blood sugar level, or eye pressure. It may be possible to equip a pacemaker with NFC, facilitating readouts of diagnostic information like battery status and adjusting the device’s configuration without requiring the patient to undergo surgery. The security model of such an application should be highly trustworthy, as malicious reconfiguration may cost lives. I am so far only aware that the feasibility of such applications is being investigated, but I feel the need to stress its possible development should be held to rigorous security standards.

During the research, I became aware that NFC truly is an upcoming technology. I learned that NFC would not become available on smartphones until early in the year 2011. Payment and transport applications are being developed and tested.

It is not guaranteed that NFC will become a success; its success depends on the willingness of the parties involved to push for the deployment of NFC technology. If consumers do not request NFC applications, the other stakeholders like banks and public transport companies will not rush developing them. Another problem that relates to the above is the possible trust issues between the involved parties regarding the use of a single Secure Element shared between them. Banks and MNOs may rightfully be reluctant to share their Secure Element with another party because they do not want any of the parties with which they share to have access to their private application data. Also, MNOs do not want other parties to use their UICC as a Secure Element because it might interfere with the primary function of the device, namely network authentication. Also marketing plays a role: one party may not want to share the same branded card with a competitor.

In this paper I mainly looked at how NFC is implemented from the client-side point of view. The back-end systems that execute and process the transactions, e.g., billing for a public transport system, will probably have vulnerabilities as well. For example, a cross-site scripting or SQL-injection attack might be possible through emulation of malicious RFID tags.[

22] The security architectures adopted by these kinds of application attacks appear to be worthy of further research as they are developed.

VI. Conclusions

At the start of this research, I had the following research question and hypothesis.

What is the security architecture of NFC applications for mobile devices, and what are some of the known and foreseen vulnerabilities?

I think that most new vulnerabilities will be found in applications built on top of NFC systems rather than in the NFC architecture itself. I envision vendors might try to apply existing business rules to this new system, even if their understanding of it is oversimplified.

During my research I looked at several possible applications for NFC currently being developed and tested. The most likely applications to initially make use of NFC appear to be payment and public transport. In these two sectors, it is likely that NFC will become available for consumers because pilots have already started, and some research into making such applications feasible has been published. Because of the current state of affairs in the development of NFC applications, I was unable to test this hypothesis thoroughly.

Making use of the UICC to function as a Secure Element, as proposed by GlobalPlatform, is hampered by the reluctance of Mobile Network Operators to share the resource with other parties. The network attacks summarized in this paper are practical attacks against SEs that behave similar to RFID tags, and work regardless of the internal architecture employed by the handset for accessing its SE.

I find it likely that the development of malware for smartphones will be boosted when the deployment of NFC payment applications becomes widespread. Smartphone devices, which often already play a central role in their user’s lives, will actually become directly financially valuable for criminal interests.

References

- Baud, J.; Osinga, T. OV-chipkaart voor interoperabiliteit in het openbaar vervoer. http://www.open-standaarden.nl/fileadmin/os/documenten/FS6-JochemBaud-ThomasOsinga.pdf, 2008.

- Shannon, R.; Stabeler, M.; Quigley, A.; Nixon, P. Profiling and targeting opportunities in pervasive advertising. In Proceedings of the Pervasive 2009 workshop on Pervasive Advertising, Nara, Japan, 2009.

- Finkenzeller, K. RFID Handbook: Fundamentals and Applications in Contactless Smart Cards and Identification; John Wiley and Sons, Ltd., 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Bradford, T. Paper, Plastic... or Phone? Payments System Research Briefing 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Ondrus, J.; Pigneur, Y. An assessment of NFC for future mobile payment systems. In Proceedings of the Management of Mobile Business, 2007. ICMB 2007. International Conference on the. IEEE, 2007, p. 43.

- World, N. Transport ticketing alliance debuts ‘Cipurse’ open alternative to Mifare. Available online: http://www.nearfieldcommunicationsworld.com/2010/12/16/35479/ospt-alliance-debuts-cipurse-open-alternative-to-mifare/.

- Yamauchi, K.; Chen, W.; Wei, D. An intensive survey of 3G mobile phone technologies and applications in Japan. In Proceedings of the Computer and Information Technology, 2006. CIT’06. The Sixth IEEE International Conference. IEEE Computer Society, 2006, p. 265.

- Balan, R.K.; Ramasubbu, N.; Prakobphol, K.; Christin, N.; Hong, J. mFerio: the design and evaluation of a peer-to-peer mobile payment system. In Proceedings of the MobiSys ’09: Proceedings of the 7th international conference on Mobile systems, applications, and services. ACM, 2009, pp. 291–304.

- Rivest, R.; Shamir, A.; Adleman, L. A method for obtaining digital signatures and public-key cryptosystems. Communications of the ACM 1978, 21, 120–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Damme, G.; Wouters, K.; Karahan, H.; Preneel, B. Offline NFC payments with electronic vouchers. In Proceedings of the MobiHeld ’09: Proceedings of the 1st ACM workshop on Networking, systems, and applications for mobile handhelds. ACM, 2009, pp. 25–30.

- Mulliner, C. Vulnerability Analysis and Attacks on NFC-enabled Mobile Phones. In Proceedings of the 2009 International Conference on Availability, Reliability and Security. IEEE Computer Society, 2009, pp. 695–700.

- Nedap. Omzetontwikkeling Nedap goed van start in 2007. http://www.nedap.com/nieuws.php?id=52.

- Nedap, O. Registreren in de thuiszorg. http://www.nedap-healthcare.com/zorgregistratie.html.

- Scarfone, K.; Padgette, J. Guide to Bluetooth security. http://csrc.nist.gov/publications/nistpubs/800-121/SP800-121.pdf, 2008.

- Herzberg, A. Payments and banking with mobile personal devices. Communications of the ACM 2003, 46, 53–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khu-Smith, V.; Mitchell, C. Using EMV cards to protect e-commerce transactions. E-Commerce and Web Technologies 2002, 388–399. [Google Scholar]

- Kömmerling, O.; Kuhn, M. Design principles for tamper-resistant smartcard processors. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the USENIX Workshop on Smartcard Technology. USENIX Association, 1999, p. 2.

- Povey, I. Assessing the impact of EMV migration: A pragmatic delivery approach. Journal of Payments Strategy & Systems 2008, 2, 349–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reveilhac, M.; Pasquet, M. Promising Secure Element Alternatives for NFC Technology. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2009 First International Workshop on Near Field Communication. IEEE Computer Society, 2009, pp. 75–80.

- Inc., G. Proposition for NFC Mobile: Secure Element Management and Messaging. http://www.globalplatform.org/documents/GlobalPlatform_NFC_Mobile_White_Paper.pdf, 2009. White paper.

- Kfir, Z.; Wool, A. Picking Virtual Pockets using Relay Attacks on Contactless Smartcard. In Proceedings of the SECURECOMM ’05: Proceedings of the First International Conference on Security and Privacy for Emerging Areas in Communications Networks. IEEE Computer Society, 2005, pp. 47–58.

- Rieback, M.; Crispo, B.; Tanenbaum, A. Is your cat infected with a computer virus? In Proceedings of the Pervasive Computing and Communications, Fourth Annual IEEE International Conference. IEEE Computer Society, 2006, pp. 10–179.

- Kocher, P.; Jaffe, J.; Jun, B. Differential power analysis. http://www.google.com/patents, 2009. US Patent 7,634,083.

| 1 |

A smartphone is a mobile phone that has other functionalities besides calling and text-messaging, like internet connectivity, email, agenda and the possibility to install third-party software. |

| 2 |

By interactive usage, I mean that both parties act as both the sender and the receiver. |

| 3 |

The only difference between an ICC and UICC is that a UICC is only used in mobile telephony networks and runs a SIM application in GSM networks |

| 4 |

In a man-in-the-middle attack, a malicious attacker places himself or herself between two communicating parties without either party knowing that their communication flows through this man in the middle. |

| 5 |

In a replay attack, the data used for an authentic transaction is intercepted and retransmitted (i.e. `replayed’) for malicious purposes |

| 6 |

A Faraday cage is a room or cage made out of a mesh of conducting material, e.g., copper. This will block out RF signals with wavelengths larger than the mesh spacing. |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).