Submitted:

30 December 2025

Posted:

31 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

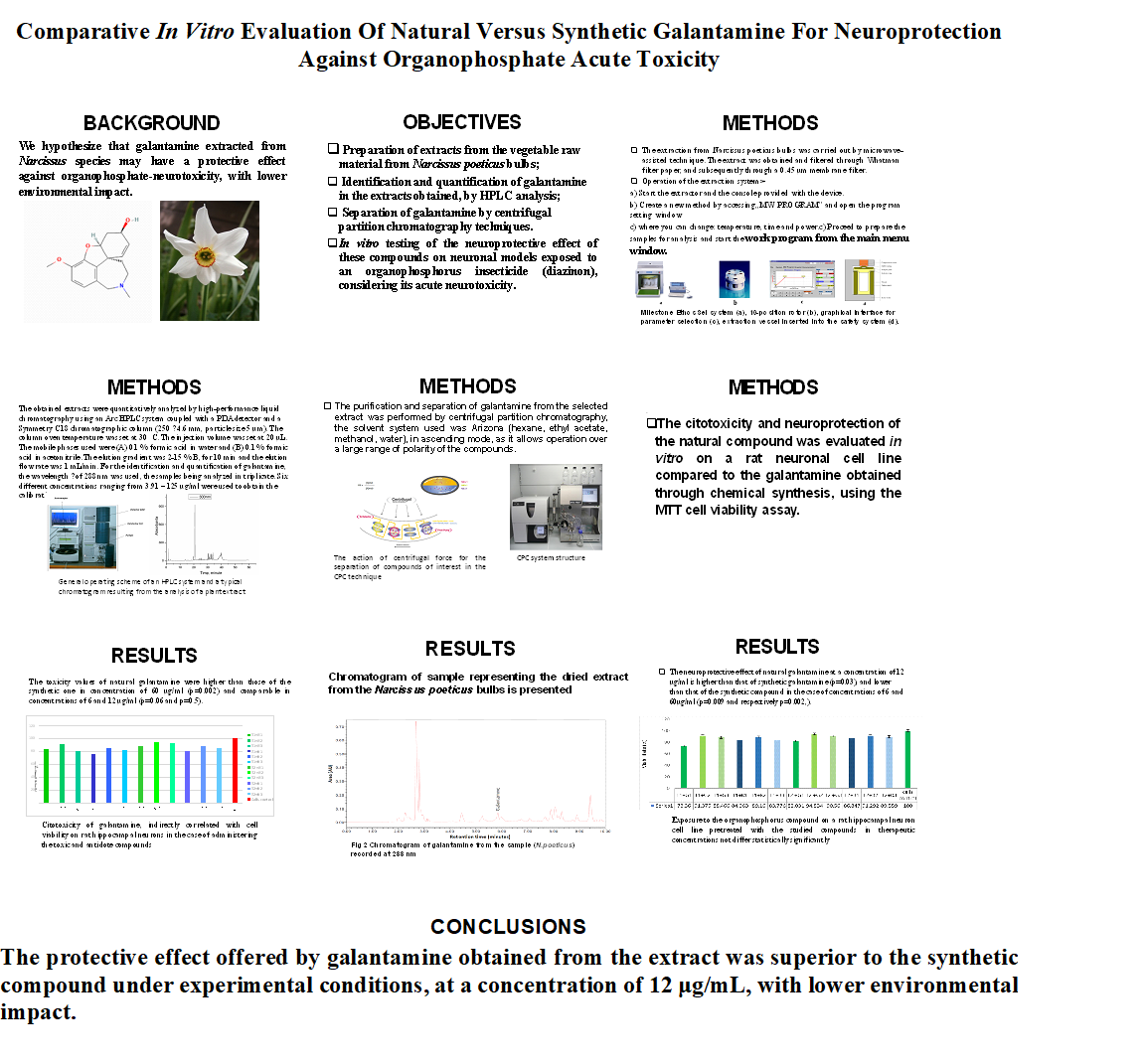

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods:

2.1. Materials and Reagents

2.2. Cell Lines

2.3. Equipment

2.4. Methods

2.5. Identification of Galantamine from Dried Natural Extracts Using HPLC Analysis

2.6. Reaction Conditions of the Chromatographic System

2.7. Advanced Natural Galantamine Isolation Tests Using Centrifugal Partition Chromatography

3. Results and Discussions

3.1. Identification of Galantamine in Dried Natural Extracts Using the HPLC Analysis

3.2. Advanced Isolation of Galantamine Using Centrifugal Partition Chromatography

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- K. Sinha and A. Sharma, Organophosphate poisoning a review, Medical Journal of Indonesia, 2003 vol. 12, no. 2, p. 120.

- S. M. Bester, M. A. Guelta, J. Cheung et al., Structural insights of stereospecific inhibition of human acetylcholinesterase by VX and subsequent reactivation by HI-6, Chemical Research in Toxicology, 2018 vol. 31, no. 12, pp. 1405–1417. [CrossRef]

- Mirjana Colovic, Tamara Lasarevicz Pasti, Daniela Carstic et al.: Acetylcholinesterase Inhibitors: Pharmacology and Toxicology. Current Neuropharmacology · 2013 May, 11(3) 315-35. [CrossRef]

- J. Misik, Ruzena Pavlikova, Jiri Cabal, et al. Acute toxicity of some nerve agents and pesticides in rats Drug Chem. Toxicol. 2014, Vol.38: 32-36. [CrossRef]

- Organisation for the prohibition of chemical weapons, 2019. https://www.opcw.org/.

- Maria Alozi, Mutasem Rawas-Qalaji: Treating organophosphates poisoning: management challenges and potential solutions Crit Rev Toxicol. 2020, 50:764-779. [CrossRef]

- Mona A. H. Yehia, Sabah G. El-Banna, Aly B. Okab: Diazinon toxicity affects histophysiological and biochemical parameters in rabbits Experimental-and-toxicologic-pathology 2007 vol 59 issue 3-4, p. 215-225.

- Dyah Ayu O. A., Zulfa Aulia Aulanni, Fajar Sotiq Permata: The study of organophosphates Diazinon toxicity toward liver histopathology and malonaldehyde serum levels on rats. Veterinary Biomedical and Clinical Journal Vet Bio Clin J. 2019 Vol. 1, 15. [CrossRef]

- Saeed Samarghandian, Tahereh Farkhondeh, Shahnaz Yousefizadeh: Toxicity Evaluation of the Subacute Diazinon in Aged Male Rats: Hematological Aspects. Cardiovasc Hematol Disord Drug Targets. 2020, vol 20, 198-201. [CrossRef]

- Elspeth J., Hulse James, D. Haslam, Stevan R. Emmet, Tom Woolley: Organophosphorus nerve agent poisoning: managing the poisoned patient British Journal of Anaesthesia 2019 Volume. 123: 457-463. [CrossRef]

- Sakib Aman, Shrebash Paul, Fazle Rabbi Chowdhury: Management of Organophosphorus Poisoning: Standard Treatment and Beyond. Crit Care Clin. 2021, Vol 37:673-686. [CrossRef]

- Aroniadou-Anderjaska, V. Apland, J. P. Figueiredo, T.H. De Araujo Furtado, Braga, M. F. Acetylcholinesterase inhibitors as weapons of mass destruction: History, mechanism of action, and medical countermeasures. Neuropharmacology. 2020, Vol 15, 181 108298. [CrossRef]

- Lukas Gorecki: Ondrej Soukup, Jan Korabecn: Countermeasures in organophosphorus intoxication: pitfalls and prospects Trends in Pharmacological Sciences 2022 Volume 43 pag. 593-606. [CrossRef]

- Bajgar J., Fusek J., Hrdina V., Patocka J., Vachek J. Acute toxicities of 2-dialkylaminoalkyl-(dialkyamido)-fluoro-phosphates. Physiol. Res. 1992; Vol 41 pag 399–402.

- Kamil Kuca, Jorge AlbertoValle da Silva, Eugenie Nepovimova, Ngo Pham , Wenda Wu, Martin Valis, Qinghua Wu, Tanos Celmar: Pralidoxime-like reactivator with increased lipophilicity - Molecular modeling and in vitro study Chemico-Biological Interactions 2023 Volume 385, 1. [CrossRef]

- Trond Myhrer, Pål Aas: Pretreatment and prophylaxis against nerve agent poisoning: Are undesirable behavioral side effects unavoidable? J.neubiorev. 2016 Volume 71, pag. 657-670. [CrossRef]

- Nikolina Maček Hrvat, Zrinka Kovarik: Counteracting poisoning with chemical warfare nerve agents Arh Hig Rada Toksikol. 2020, Vol 31 pag 266-284. [CrossRef]

- Lorke, D. E., Petroianu, G. A: Reversible cholinesterase inhibitors as pretreatment for exposure to organophosphates a review. J. Appl. Toxicol. 2018 vol 39 issue 1. Pag. 101-116. [CrossRef]

- Petroianu G. A., Nurulain S.M., Hasan M.Y., et al. Reversible cholinesterase inhibitors as pre-treatment for exposure to organophosphates: assessment using azinphos-methyl. J. Appl. Toxicol. 2014 Vol 35 issue 5 pag 493-499. [CrossRef]

- Amourette C., Lamproglou I., Barbier L., et al.: Gulf War illness: Effects of repeated stress and pyridostigmine treatment on blood-brain barrier permeability and cholinesterase activity in rat brain. Behav. Brain Res. 2009, 203, pag. 207-214. DOI. 10.1016/j.bbr.2009.05.002.

- Dames M. Madsen, Charles G. Hurst, Roger Macintosh, Dames A. Romano: Clinical Considerations in the Use of Pyridostigmine Bromide as Pretreatment for Nerve-agent Exposure U.S. Army Medical Research Institute in Chemical Defense Usamricd- SP-03-01 2003 pag 1-35. [CrossRef]

- Dietrich E. Lorke, Syed M. Nurulain, Mohamed Y. Hasan, Kamil Kuča, Georg A. Petroianu Oximes as pretreatment before acute exposure to paraoxon Journal of Applied Toxicology Vol 39 issue 11 pag 1505-1515 . [CrossRef]

- Xia, D. Y., Wang L. X., Pei S. Q The inhibition and protection of cholinesterase by physostigmine and pyridostigmine against Soman poisoning in vivo Fundam. Appl. Toxicol. Volume 1, Issue 2, March 1981, Pages 217–221. [CrossRef]

- Wigenstam, E. Artursson, A. Bucht, L.Thors: Pharmacological prophylaxis with pyridostigmine bromide against nerve agents adversely impact on airway function in an ex vivo rat precision-cut lung slice model Toxicology Mechanisms and Methods 2023 Volume 33, 9:732-740. [CrossRef]

- Walday P., A. P., Haider T, Fonnum,F.: Effect of pyridostigmine pre-treatment, HI-6 and Toxogonin treatment on rat tracheal smooth muscle response to cholinergic stimulation after organophosphorus inhalation exposure. Arch. Toxicol. 1993 67:212-219. [CrossRef]

- L. Brunton, J. S. Lazo, and I. L. O. Buxton, Goodman &Gilman’s The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics, McGraw-Hill, New York, NY, USA, 14th edition, 2022. [Google Books].

- T. H. Indu, D. Raja, B. Manjunatha, S.Ponnusankar: Can Galantamine act as an antidote for organophosphate poisoning? A Review. JSS Medical College, Indian J Pharm Sci 2016;78(4):428-435 20165700151041721000136,10.4172/pharmaceutical-sciences.1000136.

- Gabriella Marucci, Michela Buccioni, Diego Dal Ben, Catia Lambertucci, Rosaria Volpini: Francesco Amenta Efficacy of acetylcholinesterase inhibitors in Alzheimer's disease. Neuropharmacology 2021, 1:190. [CrossRef]

- Zueva I., José Dias, Sofya Lushchekina, et al.: New evidence for dual binding site inhibitors of acetylcholinesterase as improved drugs for treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. Neuropharmacology. 2019 DOI 155:131-141. 10.1016/j.neuropharm.05.025.

- Malcolm Lane, D Arice Carter, Joseph D. Pescrille, et al.: Oral Pretreatment with Galantamine Effectively Mitigates the Acute Toxicity of a SupraLethal Dose of Soman in Cynomolgus Monkeys Post-treated with. Conventional Antidotes Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 2020, Vol 375(1) pag. 115-126. [CrossRef]

- 31 Rama Rao Golime, Meehir Palit, J Acharya, D K Dubey: Neuroprotective Effects of Galantamine on Nerve Agent-Induced Neuroglial and Biochemical Changes Neurotox Res. 2018, 33:738-748. [CrossRef]

- Farlow M: Clinical pharmacokinetics of galantamine. Clin Pharmacokinet. 42:1383-1392. [CrossRef]

- Van Beijsterveldt L, Geerts R., Verhaeghe T., Willems B., Bode W., Lavrijsen K., Meuldermans W: Pharmacokinetics and tissue distribution of galantamine and galantamine-related radioactivity after single intravenous and oral administration in the rat. Arzneimittelforschung. 01 May 1991, 30(5):447-455. PMID: 1865992. [CrossRef]

- Alexander, M.Ajazuddin, R.J. Patel, S.SarafRecent expansion of pharmaceutical nanotechnologies and targeting strategies in the field of phytopharmaceuticals for the delivery of herbal extracts and bioactives J. Contr. Release, 241(2016), pp.110-124. [CrossRef]

- Marta Pérez-Gómez Moreta, Natalia Burgos-Alonso, María Torrecilla, José Marco-Contelles, Cristina Bruzos-Cidón: Efficacy of Acetylcholinesterase Inhibitors on Cognitive Function in Alzheimer's Disease. Review of Reviews Biomedicine Nov. 2021, Nov 15;9(11):1689. [CrossRef]

- Edna F, R Pereira: Yasco Aracava, Manickavasagom Alkondon, Miriam Akkerman, Istvan Merchenthaler, Edson X Albuquerque: Molecular and cellular actions of galantamine: clinical implications for treatment of organophosphorus poisoning. J Mol Neurosci. 2010, 40:196-203. [CrossRef]

- Vaibhav Rathi-Galantamine Naturally Occurring Chemicals Against Alzheimer's DiseaseChapter3.1.4 2021:83-92. [CrossRef]

- Aarti Yadav, Surender Singh Yadav, Sandeep Singh: Rajesh Dabur Natural products: Potential therapeutic agents to prevent skeletal muscle atrophy European Journal of Pharmacology. 2022, 15:174995. [CrossRef]

- Yu Pong Ng, Terry Cho Tsun Or, Nancy Y: Plant alkaloids as drug leads for Alzheimer's disease Neurochemistry International Volume 2015 89: 260-270. [CrossRef]

- Michael Heinrich, Hooi Lee Teoh: Galanthamine from snowdrop the development of a modern drug against Alzheimer’s disease from local Caucasian knowledge Journal of Ethnopharmacology 2004 Volume. 92:147-162. [CrossRef]

- Rezaul Islam, Shopnil Akash, Mohammed Murshedul Islam, Nadia Sarkar, Ajoy Kumer, Sandip Chakraborty, Kuldeep Dhama, Majed Ahmed Al-Shaeri, Yasir Anwar, Polrat Wilairatana, Abdur Rauf, Ibrahim F. Halawani, Fuad M. Alzahrani, Haroon Khan: Alkaloids as drug leads in Alzheimer's treatment: Mechanistic and therapeutic insights Brain Research Volume. 1834,1:2024-148886. [CrossRef]

- J. Egea.D. Martín-de-Saavedra, E. Parada, A. Romero , L. del Barrio, A.O. Rosa, A.G. García, M. G. López: Galantamine elicits neuroprotection by inhibiting iNOS, NADPH oxidase and ROS in hippocampal slices stressed with anoxia/reoxygenation. Neuropharmacology 2012 Vol 311 DOI1082-1090. [CrossRef]

| Current Number | Dry extract sample (P) | Mass of maceration dried extract (MAC) (g)/100 g bulbs | Mass ultrasonic dried extract (UAE) (g)/100 g bulbs |

| 1 | Narcissus poeticus (P4) | 10.65 ± 0.02 | 10.25 ± 0.01 |

| 2 | N.pseudonarcissus (P5) | 10.02 ± 0.007 | 9.24 ± 0.008 |

| 3 | Narcissus double (P6) | 10.04 ± 0.05 | 9.13 ± 0.003 |

| Current number | Sample code | Galantamine (mg/100 mg dry extract) |

| 1 | P4 MAC SOLID | 7.928±0.016 |

| 2 | P5 MAC SOLID | 2.114±0.024 |

| 3 | P6 MAC SOLID | 5.893±0.004 |

| 4 | P4 UAE SOLID | 2.682±0.017 |

| 5 | P5 UAE SOLID | 0.768±0.014 |

| 6 | P6 UAE SOLID | 1.597±0.067 |

| Current Number | Initial value of galantamine in the fraction collected by the method described above (mg/dL) | Final value of galantamine in the fraction collected by the method described above (mg/dl) | Percentage of galantamine recovered (%) |

| 1 | 2.352±0.0025 | 2.231 ±0.0016 | 94.89 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.