1. Introduction

The use of veno-venous extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (VV-ECMO) to treat patients with severe acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) has increased since the 2009 H1N1 influenza pandemic and peaked during the COVID-19 pandemic (1). Most VV-ECMO cannulations are done while patients are heavily sedated and mechanically ventilated. The awake ECMO strategy, i.e cannulating patients with ARDS for ECMO while awake and spontaneously breathing, and treating them without sedation and mechanical ventilation has several potential advantages. These include reducing ventilatory-induced lung injury and ventilatory-associated pneumonia, and increasing functional residual capacity (2). Moreover, by contracting the diaphragm, patients who breathe spontaneously achieve more balanced ventilation-perfusion matching (2), and avoid ventilatory-induced diaphragmatic damage (3). Patients treated with ECMO while awake can undergo physiotherapy and rehabilitation much earlier, during the peak of their disease severity. At this disease stage, patients treated conservatively are in deep sedation and even under muscle relaxants. Awake patients can communicate and potentially have a reduced risk for delirium (4).

Currently, there is a notable absence of large-scale studies of patients treated with ECMO that directly compared outcomes between those cannulated while awake and while sedated. Though individual case reports and small-scale studies have provided insights into the potential benefits of awake ECMO (5-10), a comprehensive comparison of outcomes between these two approaches is lacking in the existing literature.

We recently published our experience in awake ECMO cannulation of patients with ARDS (4). We demonstrated, as a proof-of-concept, the feasibility of treating patients with severe ARDS using VV-ECMO without sedation and mechanical ventilation in selected patients.

In the current study, we collected and analyzed data from all the Israeli intensive care units that practiced awake ECMO in patients with COVID-19 ARDS. We compared the outcomes of patients treated by awake versus matched mechanically ventilated ECMO.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Population

We conducted a multicenter, retrospective cohort study in eight ECMO centers in Israel. Data were gathered from the Israeli ECMO registry of patients with COVID-19-induced ARDS who were treated with ECMO. The Israeli ECMO Society and ECMO registry were founded in 2019 and include 13 medical centers that operate ECMO.

We included patients with confirmed COVID-19 via polymerase chain reaction who were treated with VV-ECMO for COVID-19-induced ARDS from April 2020 to December 2022. Patients were excluded if they were under 18 years of age or if their records indicated poor data collection.

The study group was defined as patients who were cannulated for ECMO while awake and spontaneously breathing. The control group was established by using propensity score matching in a 1:4 ratio, by age, sex, and body mass index, of patients who were cannulated for ECMO after sedation and mechanical ventilation.

Notably, specific guidelines and criteria have not been issued regarding the selection of patients for whom to attempt awake ECMO. During the study period, diagnoses and clinical decisions, including the decision to initiate ECMO, were made at each of the included centers according to the judgment of the treating team. For patients deemed to require mechanical ventilation with a high likelihood of eventually requiring ECMO, decisions were made as to whether to intubate or attempt awake ECMO. Generally, when patients were alert enough and able to collaborate, awake ECMO was considered an alternative to mechanical ventilation (4).

2.2. Data Collection

The data collected included demographic information, comorbidities, and pre-ECMO baseline parameters, including respiratory support modality, gas exchange data, and the duration of invasive mechanical ventilation when it was used. ECMO-related parameters during the ECMO therapy were also recorded: total ECMO duration, maximal blood flow, maximal gas flow, and ECMO-related complications.

2.3. Definitions

ARDS was defined according to the "Berlin criteria" (11).

Thrombotic events were defined as either venous or arterial thrombosis, heparin-induced thrombocytopenia, or ECMO circuit thrombosis necessitating circuit change. Bleeding was defined as bleeding necessitating treatment with blood products. Secondary infections were defined as ventilatory-induced pneumonia, bacteremia, or any other non-COVID-19-induced sepsis.

2.4. Outcomes

The primary outcome was mortality during six months of follow-up. Secondary outcomes were: mortality on ECMO, the duration of ECMO therapy, the duration of invasive mechanical ventilation-free ECMO therapy, and the duration of invasive mechanical ventilation.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

Covariate balance after matching was assessed using standardized mean differences, with values <0.1 indicating acceptable balance. A Cox regression model was used to estimate the hazard ratio (HR) with a 95% confidence interval (CI), of mortality during a six-month follow-up of patients who were awake compared to sedated during ECMO cannulation. COVID-19 variants were adjusted to control for possible confounders. No imputation was performed to handle missing data. All the statistical analyses were performed using R software (version 4.3.1; R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

3. Results

We identified 24 patients who were cannulated for ECMO during the study period, while awake and spontaneously breathing, and matched them to 96 controls.

Table 1 shows baseline characteristics of the study population. The mean age was 52 years (standard deviation [SD] 11), and 78% were males. The mean body mass index (BMI) was 32 kg/m2 (SD 8). Among those who were cannulated for ECMO while awake (the study group) compared to those who were cannulated while sedated (the control group), the mean Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score was lower (5.2 vs. 9.1, p<0.001). For the study compared to the control group, pre-ECMO PO2 and PCO2 were lower: 53 mmHg vs 62 mmHg, p=0.02; and 43 mmHg vs 65 mmHg, p<0.001, respectively. Although the dominant COVID-19 variant shifted during the study period (from wild type to Alpha, Delta, and Omicron), variant distribution did not differ significantly between groups (p=0.1). Nor did the mean ECMO blood flow differ between the groups.

Fifteen of the 24 patients (63%) who were cannulated for ECMO while awake were eventually intubated during the ECMO run. Intubation occurred after a mean of 12 (SD 12) days from cannulation. The mean mechanical ventilation-free days in the study group was 12.3 (SD 15).

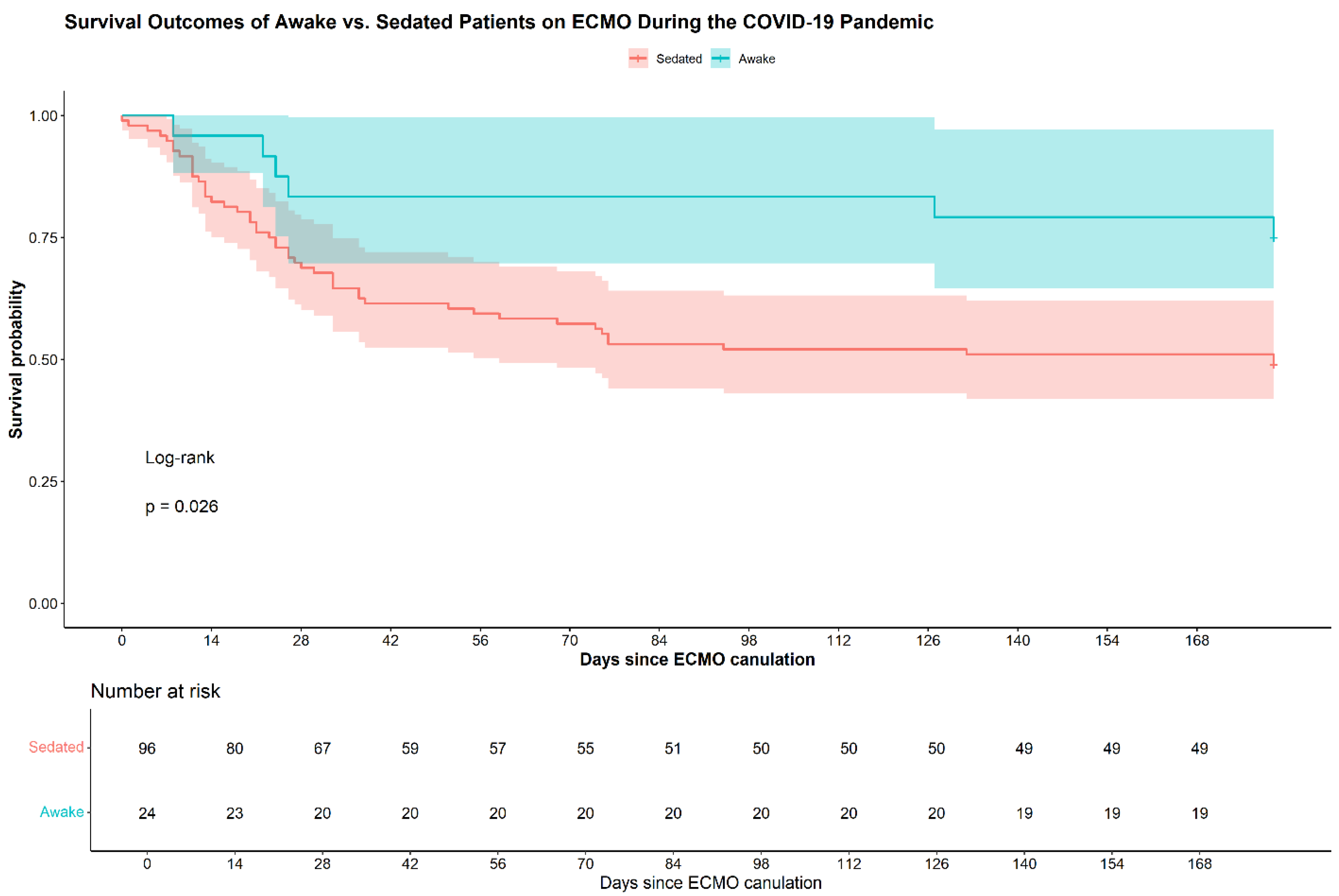

Table 2 compares the outcomes of the study and control groups. Durations of time on ECMO and in the intensive care unit did not differ significantly between the groups. Six-month survival was higher in the study compared to the control group (75% vs 49%, p=0.02).

Figure 1 shows the Kaplan-Meier plots of the two groups.

Rates of mechanical and infectious complications were lower in the study compared to the control group: 21% vs 67% p<0.001, and 21% vs 40%, p<0.001, respectively. Among the subgroup of patients who were cannulated while awake and never required ventilation, no infectious complications occurred during the entire ECMO run. Hemostatic complications either thrombotic or hemorrhagic, occurred more frequently in the study than the control group (54% vs 29%, p = 0.021).

The HR for six-month mortality was 0.40 for the study compared to the control group (95% CI 0.17-0.92, p=0.032). Adjustment for the COVID-19 variant yielded a HR of 0.44, suggesting a continued protective effect, though the association was of borderline statistical significance (95% CI: 0.19–1.03; p=0.059).

4. Discussion

Our study demonstrates improved clinical outcomes in patients with COVID-19-induced ARDS who underwent awake VV-ECMO cannulation compared to those cannulated under sedation and mechanical ventilation.

A number of studies reported better outcomes of awake compared to sedated ECMO in patients with respiratory failure awaiting lung transplantation (12-14). While those patients and patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease have reasonable toleration for being awake on ECMO, for patients with ARDS, respiratory drive control is more difficult to achieve. This is consequent to their lung pathophysiology, which includes severe inflammation, large parenchymal consolidation, and low lung compliance. Hence, among awake patients with ARDS, intubation is more common (15). Despite these challenges, several case series have shown the feasibility of an awake ECMO strategy in patients with ARDS (4, 16-19), though evidence of the actual benefit of this strategy is scarce. Although 63% of awake ECMO patients were eventually intubated, they had a mean of 12.3 (SD 15) mechanical-ventilation-free days. Notably, none of the patients who remained non-intubated experienced infectious complications, highlighting the potential benefits of avoiding intubation in patients with ARDS.

Awake veno-arterial-ECMO cannulation was also found to be associated with improved mortality (20). Mohamed et al analyzed data of 28,627 patients from the ELSO registry, and compared the outcomes of 797 patients who were cannulated for VV-ECMO while awake and spontaneously breathing to those who were cannulated while on mechanical ventilation (21). Among the patients who underwent awake cannulation, the mean age was older, and the prevalence of chronic lung diseases and ischemic heart disease was greater. Thirty-five percent of them were cannulated with the intent of pursuing a lung transplant, compared to only 4.7% in the mechanically ventilated group. Survival to hospital discharge did not differ significantly between the groups. The population of that study was diverse, and included patients who were cannulated for VV-ECMO due to various lung pathologies, for which disease course and prognosis vary widely. This contrasts with our focus on a highly specific group of patients with COVID-19-induced ARDS. This may explain the differences in outcomes between the two studies.

We report lower pre-ECMO PO2 and PCO2 in the study group compared to the control group. In their large-scale study, Mohamed et al also found lower PCO2 in the awake group, though the PO2 was higher (21). We assume that the difference between our findings does not reflect a difference in disease severity, but merely differences resulting from the ventilation status (i.e, spontaneous vs mechanical ventilation). In patients on mechanical ventilation, the use of lung protective ventilation and high positive end expiratory pressure may result in permissive hypercapnea and higher PO2.

We found a lower mean SOFA score among those cannulated while awake compared to the control group (5.2 vs. 9.1, p<0.001). Mechanical ventilation status and the level of consciousness are major parameters in the SOFA scoring, and by definition, differed between the two groups. This study has several strengths. It is the largest study to date to focus on the prognosis of awake ECMO cannulation, specifically in patients with viral ARDS. Patients were included from eight hospitals that practice an awake ECMO cannulation strategy. This study has several limitations. First, the relatively small number of patients who were cannulated while awake may have led to statistical error. Second, the retrospective design raises the possibility of selection bias. It may be argued that physicians choose patients with better health profiles for awake cannulation, and that this could account for their better outcomes, though differences in medical background and disease status were not found.

Authors should discuss the results and how they can be interpreted from the perspective of previous studies and of the working hypotheses. The findings and their implications should be discussed in the broadest context possible. Future research directions may also be highlighted.

5. Conclusions

Awake VV-ECMO cannulation in COVID-19-induced ARDS may be associated with improved survival compared to traditional sedated ECMO strategies. Prospective studies are warranted to confirm these findings and refine patient selection criteria.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, O.G. and E.I.; Methodology, O.G., A.B., and N.S.; Formal Analysis, O.G., A.B., and N.S.; Investigation, O.G., E.I., D.S., Y.K., Y.H., M.M., A.S., M.Z.D., and D.F.; Data Curation, A.B.; Writing – Original Draft Preparation, O.G. and A.B.; Writing – Review and Editing, O.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the amended Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of each participating center. For the Soroka University Medical Center Helsinki board, the approval number was SOR-0158-21, and the approval date was August 30, 2021. For the Sheba Medical Center Helsinki board, the approval number was SMC- 8186-21 and the approval date March 30, 2022. For the Rambam Medical Center Helsinki board, the approval number was 0286-21-RMB-D and the approval date was May 1, 2021. For the Wolfson Medical Center Helsinki board, the approval number was WOMC-0109-21 and the approval date was June 14, 2021. For the Kaplan Medical Center Helsinki Board, the approval number was KMC- 0212-021 and the approval date was January 25, 22. For the Shaare Zedek Medical Center Helsinki board, the approval number was SZMC-0205-21 and the approval date July 26, 2021. For the Shamir Medical Center Helsinki board, the approval number was RMC-0072-21 and the approval date was January 28, 2021. For the Tel-Aviv Sourasky Medical Center Helsinki board, the approval number was TLV0432-2 and the approval date was Nov 23, 2023.

Informed Consent Statement

A waiver of informed consent was granted, as this was a retrospective observational study based on data from the Israeli ECMO Registry, and no personally identifiable patient information was collected or analyzed.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

We thank Cindy Cohen who provided English and scientific editing services.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interests.

Financial\nonfinancial disclosures: None declared. There are no ethical or financial conflicts of interest for any of the authors.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ARDS |

Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome |

| BMI |

body mass index |

| ECMO |

extracorporeal membrane oxygenation |

| LOS |

Length of Stay |

| ICU |

Intensive Care Unit |

| HR |

hazard ratio |

| OR |

Odds Ratio |

| SOFA |

Sequential Organ Failure Assessment |

| VV |

veno-venous |

References

- ELSO Registry [Internet]. Available from: https://www.elso.org/registry/internationalsummaryandreports/reports.aspx#SummaryOctober2024.

- Langer, T.; Santini, A.; Bottino, N.; Crotti, S.; Batchinsky, A.I.; Pesenti, A.; Gattinoni, L. “Awake” extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO): pathophysiology, technical considerations, and clinical pioneering. Crit. Care 2016, 20, 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Marin-Corral, J.; Dot, I.; Boguña, M.; Cecchini, L.; Zapatero, A.; Gracia, M.P.; Pascual-Guardia, S.; Vilà, C.; Castellví, A.; Pérez-Terán, P.; et al. Structural differences in the diaphragm of patients following controlled vs assisted and spontaneous mechanical ventilation. Intensiv. Care Med. 2019, 45, 488–500. [CrossRef]

- Galante, O.; Hasidim, A.; Almog, Y.; Cohen, A.; Makhoul, M.; Soroksky, A.; Zikri-Ditch, M.; Fink, D.; Ilgiyaev, E. Extracorporal Membrane Oxygenation in Nonintubated Patients (Awake ECMO) With COVID-19 Adult Respiratory Distress Syndrome: The Israeli Experience. Asaio J. 2023, 69, e363–e367. [CrossRef]

- Assanangkornchai, N.M.; Slobod, D.M.; Qutob, R.; Tam, M.C.; Shahin, J.M.; Samoukovic, G.M. Awake Venovenous Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation for Coronavirus Disease 2019 Acute Respiratory Failure. Crit. Care Explor. 2021, 3, e0489. [CrossRef]

- Azzam, M.H.M.; Mufti, H.N.M.M.; Bahaudden, H.M.; Ragab, A.Z.; Othman, M.M.; Tashkandi, W.A.M. Awake Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation in Coronavirus Disease 2019 Patients Without Invasive Mechanical Ventilation. Crit. Care Explor. 2021, 3, e0454. [CrossRef]

- Ghizlane, E.A.; Manal, M.; Sara, B.; Choukri, B.; Samia, B.; Abderrahim, E.K.; Hamid, Z.; Amine, B.; Houssam, B.; Brahim, H. Early initiation of awake venovenous extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) in critical COVID-19 pneumonia: A case reports. Ann. Med. Surg. 2021, 68, 102641. [CrossRef]

- Loyalka, P.; Cheema, F.H.; Rao, H.; Rame, J.E.; Rajagopal, K.M. Early Usage of Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation in the Absence of Invasive Mechanical Ventilation to Treat COVID-19-related Hypoxemic Respiratory Failure. Asaio J. 2021, 67, 392–394. [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.; Li, W.; Jiang, F.; Wang, T. Successfully treatment of application awake extracorporeal membrane oxygenation in critical COVID-19 patient: a case report. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2020, 15, 1–4. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.-C.; Li, T. Awake extracorporeal membrane oxygenation support for a critically ill COVID-19 patient: A case report. World J. Clin. Cases 2021, 9, 5963–5971. [CrossRef]

- ARDS Definition Task Force Ranieri VM: Acute respiratory distress syndrome: the Berlin definition. JAMA 2012;307:2526–2533.

- Fuehner, T.; Kuehn, C.; Hadem, J.; Wiesner, O.; Gottlieb, J.; Tudorache, I.; Olsson, K.M.; Greer, M.; Sommer, W.; Welte, T.; et al. Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation in Awake Patients as Bridge to Lung Transplantation. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2012, 185, 763–768. [CrossRef]

- Biscotti, M.; Gannon, W.D.; Agerstrand, C.; Abrams, D.; Sonett, J.; Brodie, D.; Bacchetta, M. Awake Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation as Bridge to Lung Transplantation: A 9-Year Experience. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2017, 104, 412–419. [CrossRef]

- Benazzo, A.; Schwarz, S.; Frommlet, F.; Schweiger, T.; Jaksch, P.; Schellongowski, P.; Staudinger, T.; Klepetko, W.; Lang, G.; Hoetzenecker, K.; et al. Twenty-year experience with extracorporeal life support as bridge to lung transplantation. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2019, 157, 2515–2525.e10. [CrossRef]

- Crotti, S.; Bottino, N.; Ruggeri, G.M.; Spinelli, E.; Tubiolo, D.; Lissoni, A.; Protti, A.; Gattinoni, L. Spontaneous Breathing during Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation in Acute Respiratory Failure. Anesthesiology 2017, 126, 678–687. [CrossRef]

- Hoeper, M.M.; Wiesner, O.; Hadem, J.; Wahl, O.; Suhling, H.; Duesberg, C.; Sommer, W.; Warnecke, G.; Greer, M.; Boenisch, O.; et al. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation instead of invasive mechanical ventilation in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome. Intensiv. Care Med. 2013, 39, 2056–2057. [CrossRef]

- Yeo, H.J.; Cho, W.H.; Kim, D. Awake extracorporeal membrane oxygenation in patients with severe postoperative acute respiratory distress syndrome. 2016, 8, 37-42–42. [CrossRef]

- Stahl, K.; Seeliger, B.; Hoeper, M.M.; David, S. “Better be awake”—a role for awake extracorporeal membrane oxygenation in acute respiratory distress syndrome due to Pneumocystis pneumonia. Crit. Care 2019, 23, 1–2. [CrossRef]

- Sklienka, P.; Burša, F.; Frelich, M.; Máca, J.; Vodička, V.; Straková, H.; Bílená, M.; Romanová, T.; Tomášková, H. Optimizing the safety and efficacy of the awake venovenous extracorporeal membrane oxygenation in patients with COVID-19-related ARDS. Ther. Adv. Respir. Dis. 2024, 18. [CrossRef]

- Montero, S.; Huang, F.; Rivas-Lasarte, M.; Chommeloux, J.; Demondion, P.; Bréchot, N.; Hékimian, G.; Franchineau, G.; Persichini, R.; Luyt, C.; et al. Awake venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for refractory cardiogenic shock. Eur. Hear. Journal. Acute Cardiovasc. Care 2021, 10, 585–594. [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, A.; Saeed, O.M.; Fazzari, M.; Gong, M.; Uehara, M.; Forest, S.; Carlese, A.; Rahmanian, M.; Alsunaid, S.; Mansour, A.; et al. “Awake” Cannulation of Patients for Venovenous Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygen: An Analysis of the Extracorporeal Life Support Organization Registry. Crit. Care Explor. 2024, 6, e1181. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |