Submitted:

29 December 2025

Posted:

30 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Accurate snow monitoring is critical for understanding hydrological processes and managing water resources. However, traditional snow sensing networks in the United States, such as the United States Department of Agriculture’s (USDA) SNOwpack TELemetry (SNOTEL) system, are costly and limited in spatial coverage. This study presents the design and deployment of a lower-cost, open-source snow sensing station aimed at improving the accessibility and affordability of snow hydrology monitoring. The system integrates research-grade environmental sensors with an Arduino-based Mayfly datalogger, providing high temporal resolution measurements of snow depth, radiation fluxes, air and soil temperatures, and soil moisture. Designed for adaptability, the station supports multiple sensor types, various power configurations—including solar and battery-only setups—multiple telemetry options, and capability for diverse deployment environments, including forested and open terrain. A multi-site case study at Tony Grove Ranger Station in northern Utah, USA demonstrated the station’s performance across different physiographic conditions. Results show that the system significantly reduces costs while increasing the spatial resolution of data, offering a scalable solution for enhancing snow monitoring networks. This study contributes an open-source hardware and software design that facilitates replication and adaptation by other researchers, supporting advancements in snow hydrology research.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Requirements and Design Considerations

- Must collect environmental measurements that facilitate the modeling and prediction of snow hydrology processes.

- Must support common sensor inputs to facilitate use of research grade sensors and to enable further development of these stations with sensors other than those listed in this final design.

- Must collect data at regular intervals and record observations along with their timestamps in local storage on the datalogger.

- Must be constructed using easily available, off-the-shelf components that are available locally or online.

- Assembly and deployment of the station must be possible by anyone with the proper tools.

- Must be deployable on a variety of terrains, such as slopes and under tree canopies.

- Must be autonomously powered and configurable to use a variety of power sources and systems appropriate for selected deployment locations.

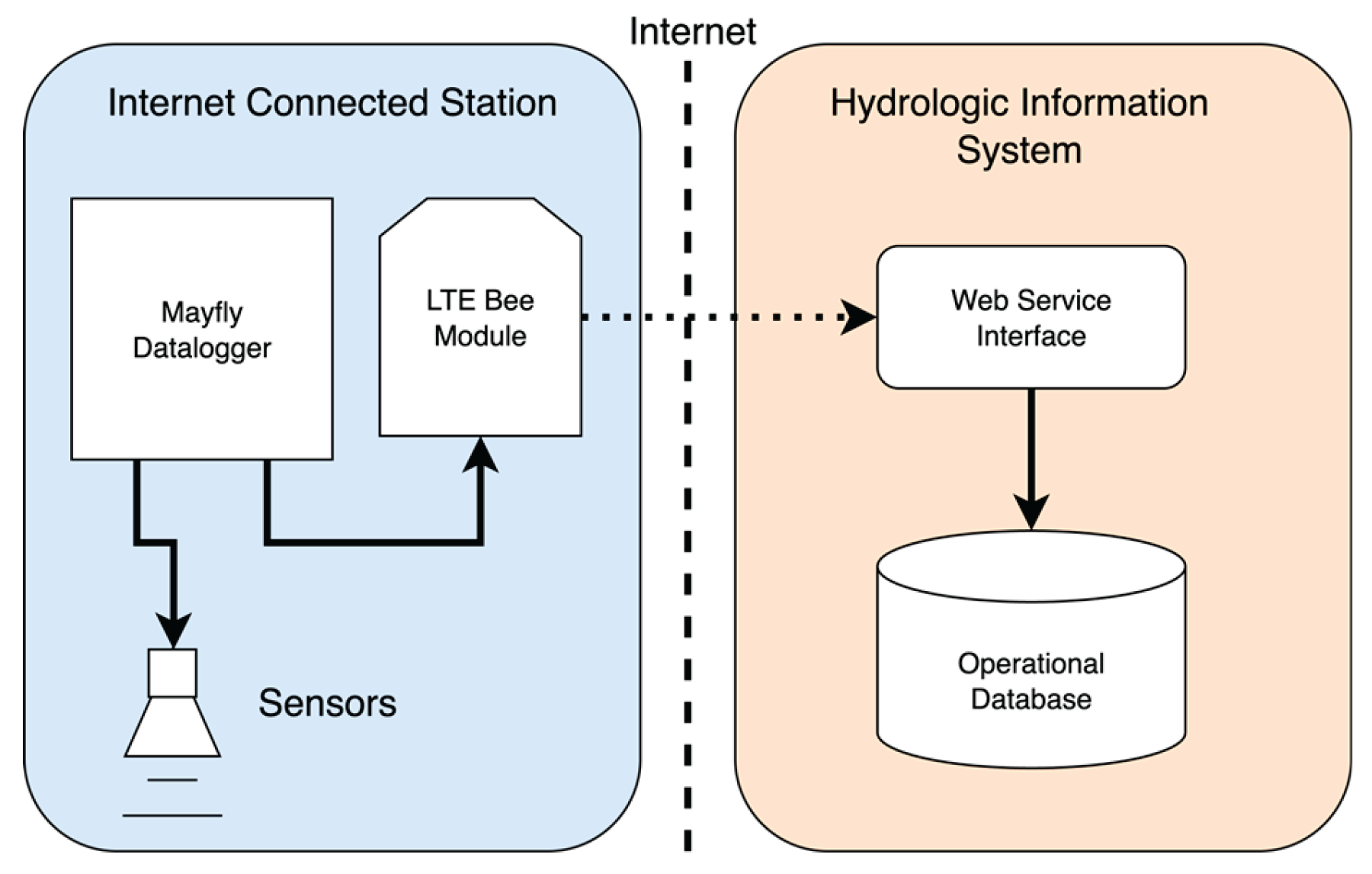

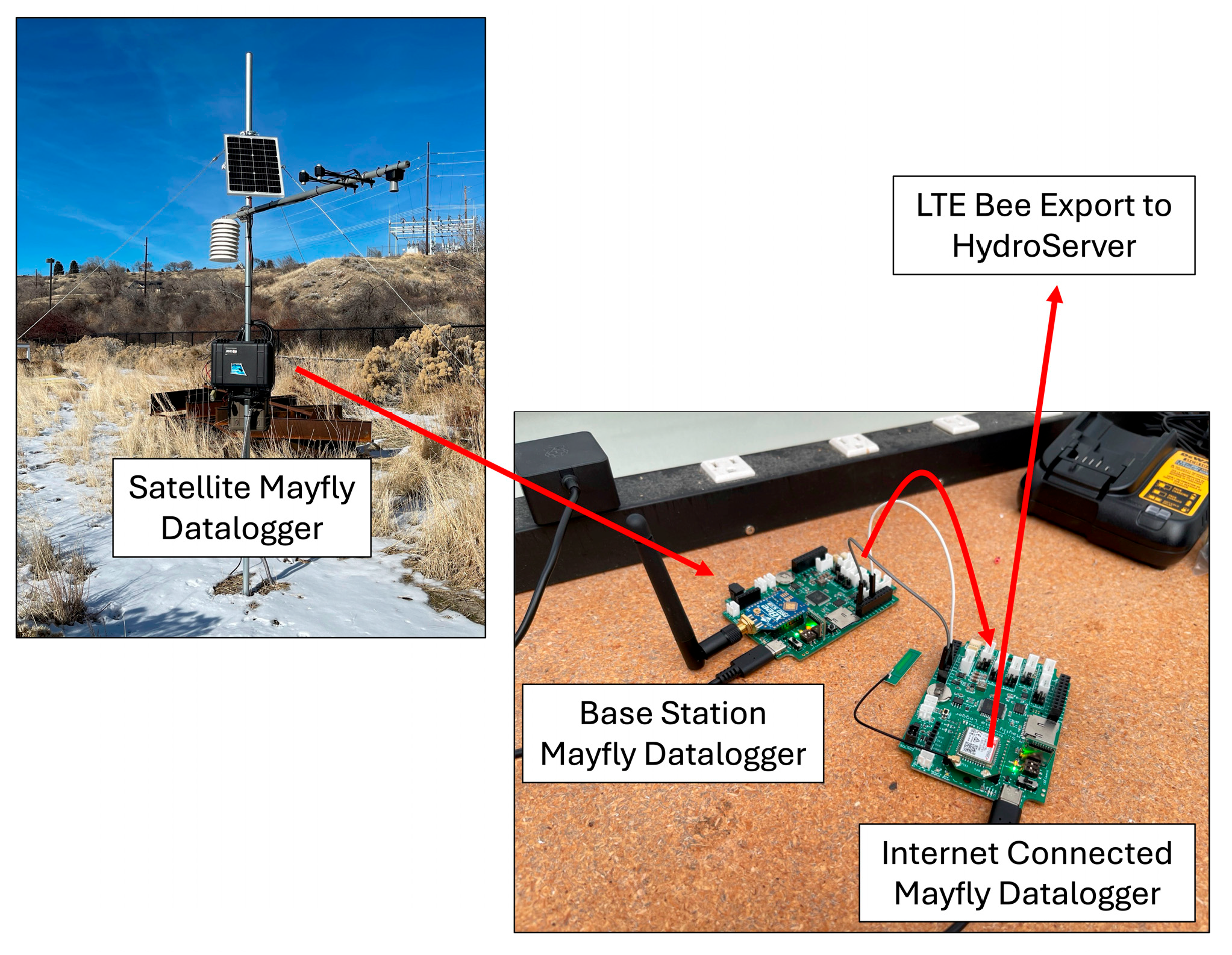

- Must be capable of connecting to the Internet directly with cellular data coverage or by wirelessly sending data to another station that has an Internet connection.

- Must be capable of transmitting data and integrating with existing radio telemetry systems (e.g., stations must be capable of joining a radio network with other, existing stations).

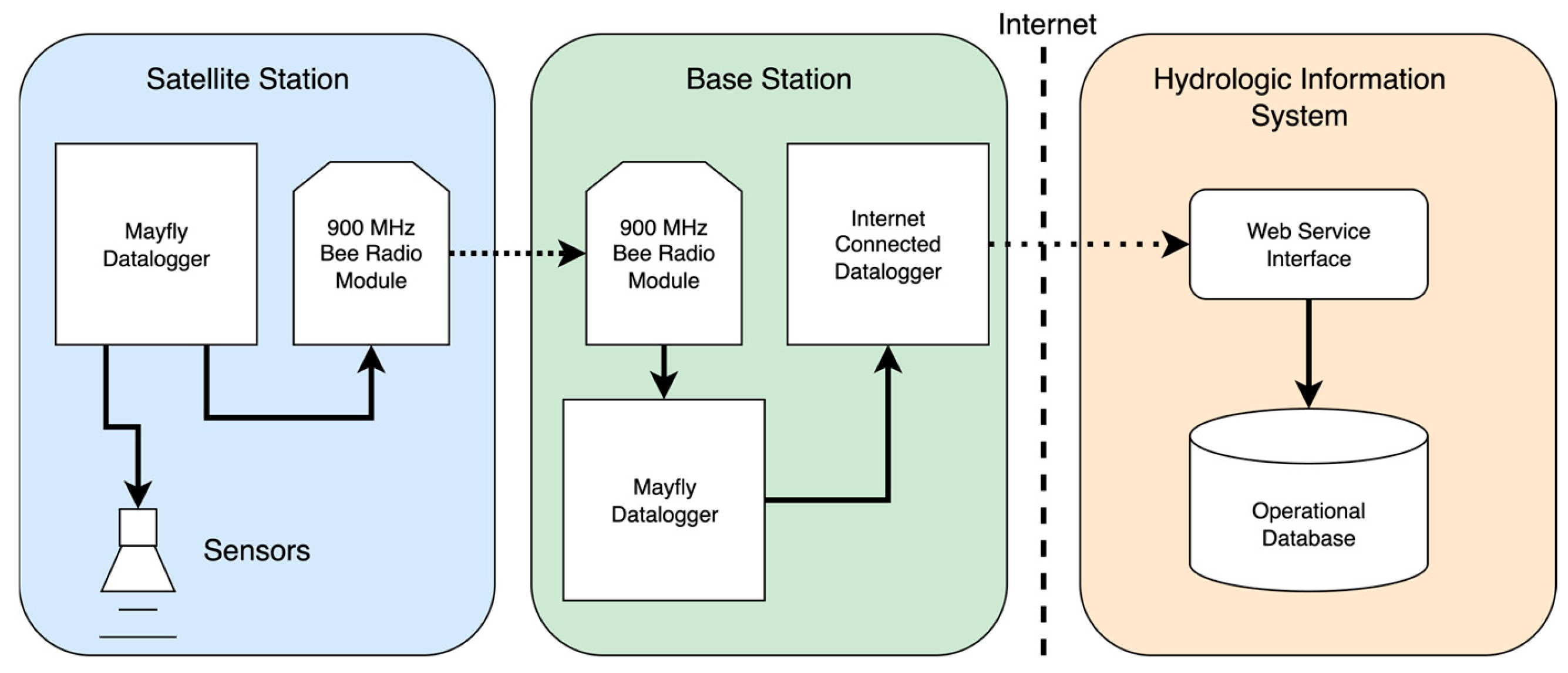

- Must be capable of participating in hybrid networks that mix radio technologies (e.g., multiple stations communicating data using 900 MHz spread-spectrum radios to a station that has a cellular Internet connection).

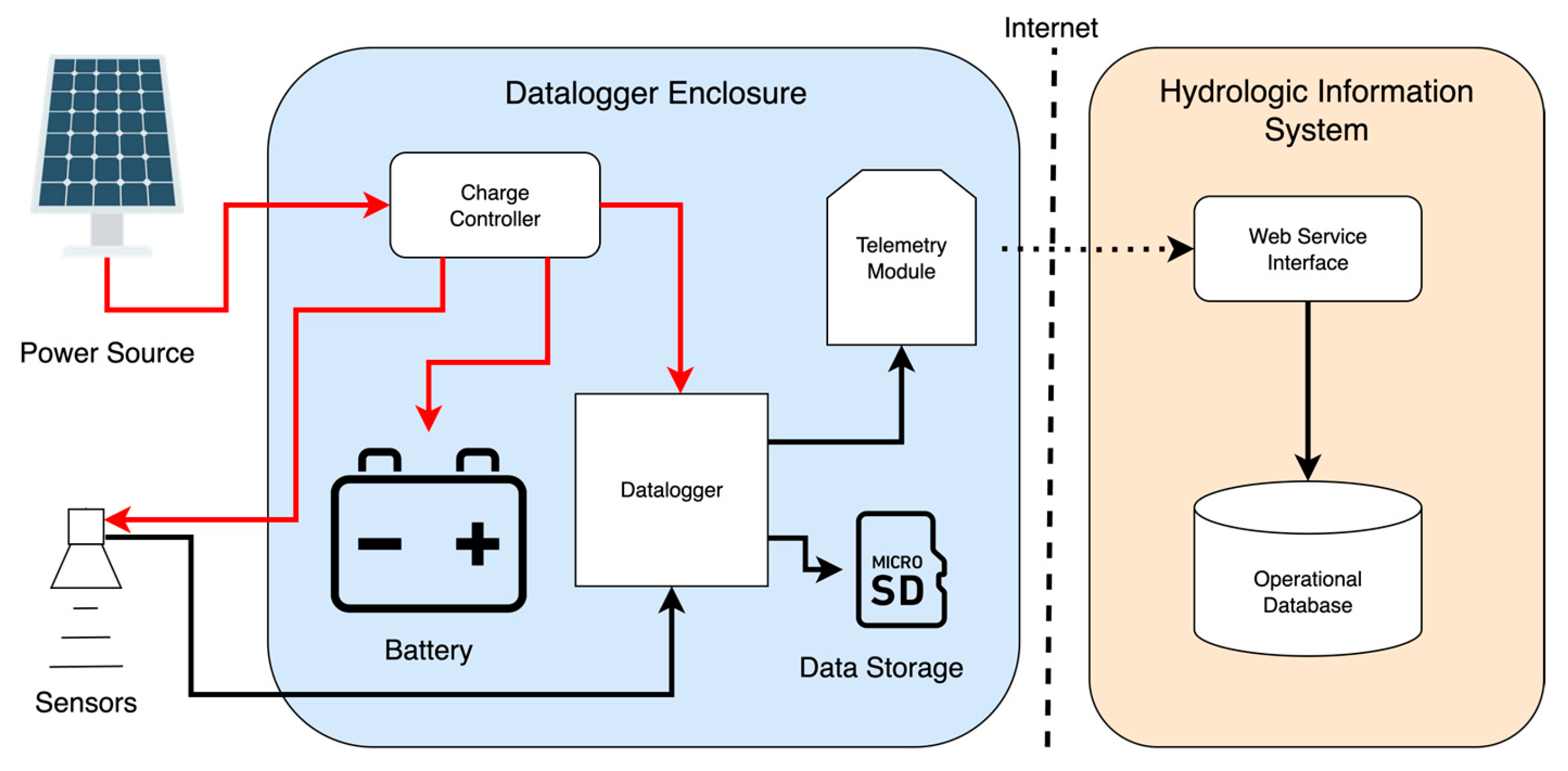

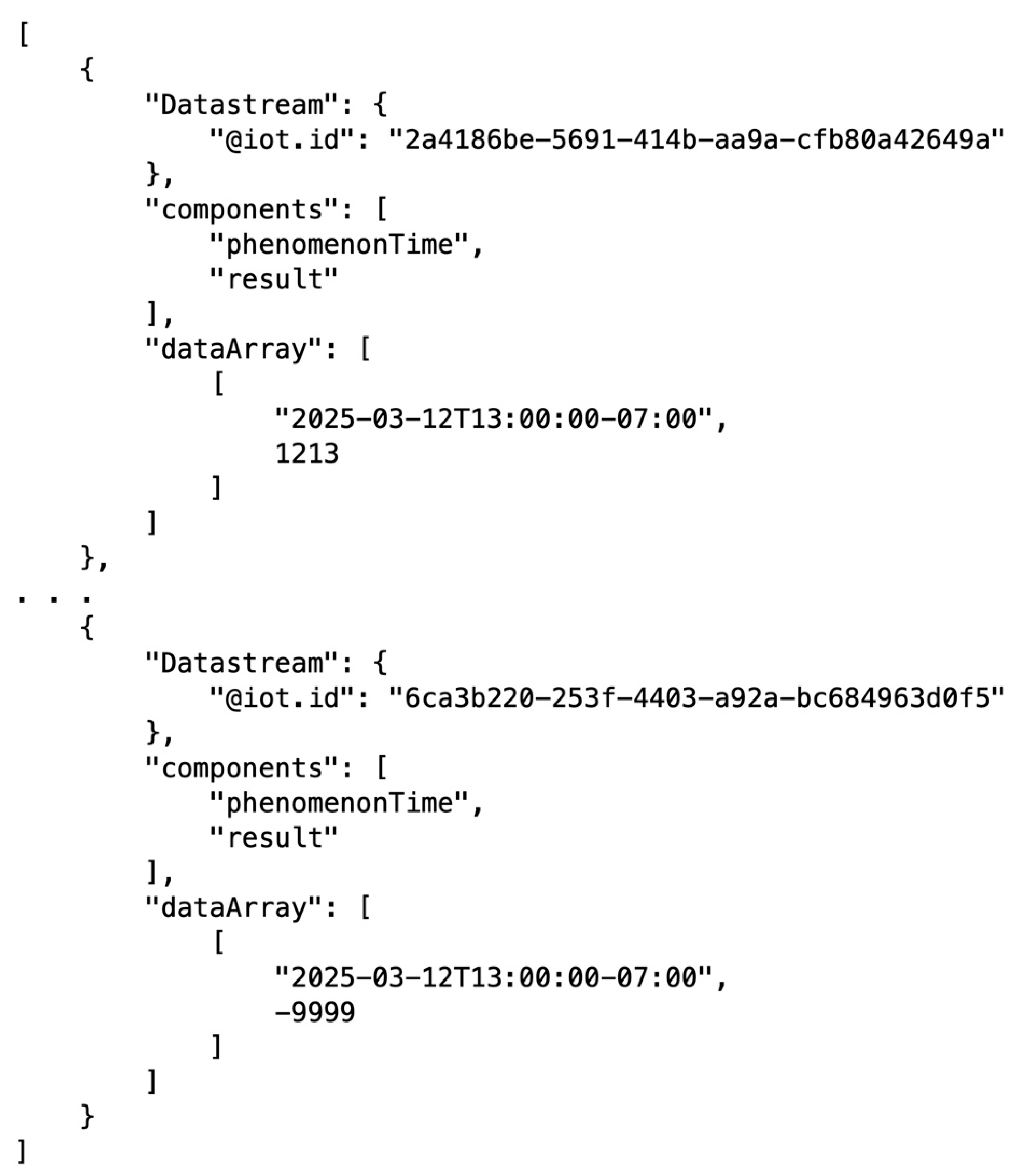

- Must be capable of manual data downloads or integration with a Hydrologic Information System (HIS) for real-time delivery of data to an operational system that enables storage, management, and sharing of the data.

2.2. Station Architecture, Sensing, and Data Logging Hardware Design

2.2.1. Sensors

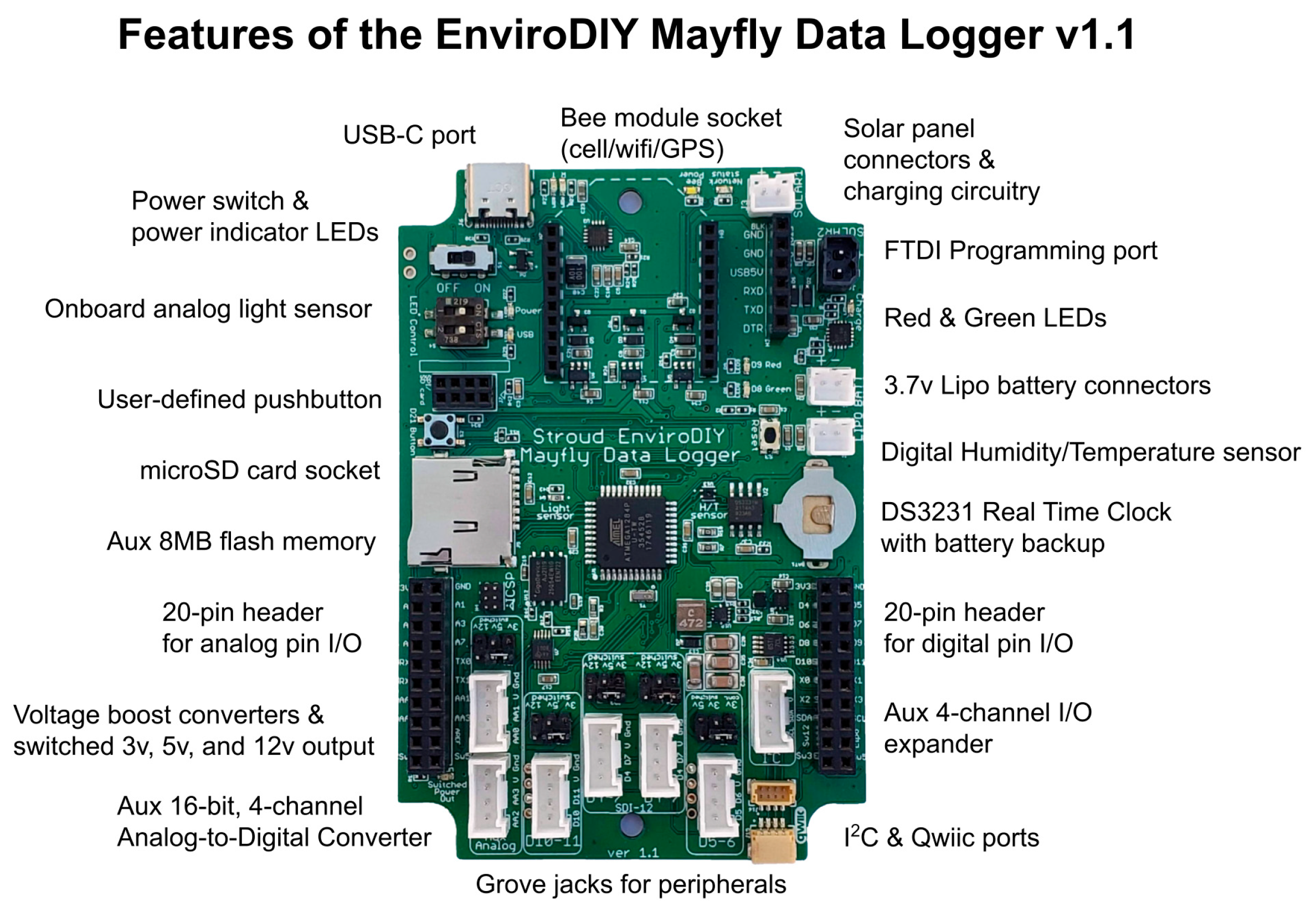

2.2.2. Datalogger

2.3. Code

2.4. Power

2.4.1. Power Relay

2.4.2. Battery

2.4.3. Charge Controller

2.4.4. Solar Panel

2.5. Communications and Telemetry

- For sites without cellular network service, the Bee module used for communication must be capable of 900 MHz spread-spectrum radio transmissions.

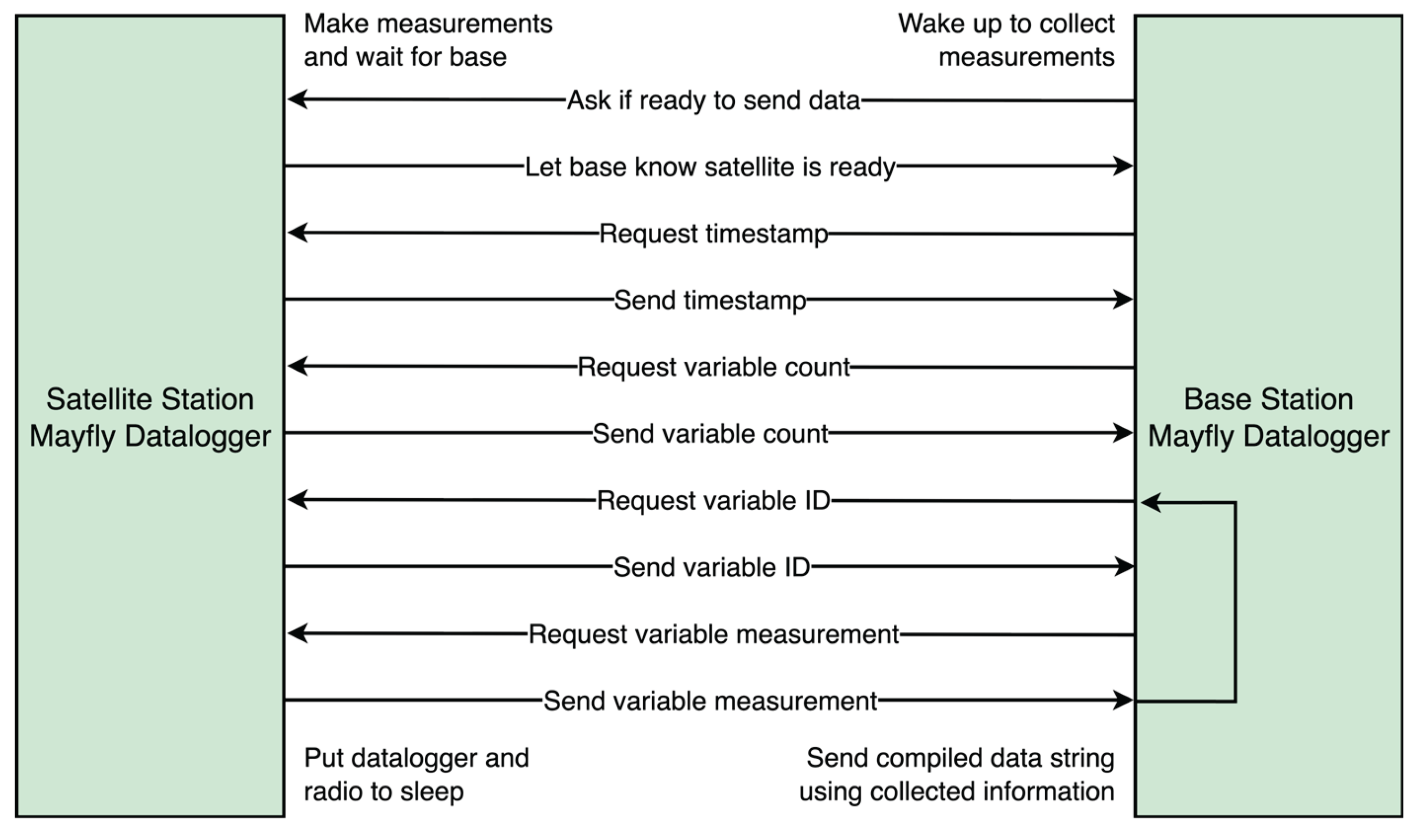

- In networks without cellular coverage and where data transmission to an Internet-connected datalogger cannot be made without having other stations relay the message, the selected RF Bee module needs to have the ability to mesh network. Mesh networking is the collaboration of wireless modules in a network to help transmit messages along to other modules, regardless of which module a message is addressed to. Without mesh networking, every satellite station would need direct line-of-sight communication with the base station, potentially limiting the locations at which stations could be deployed and reducing potential distances between stations within a network.

- The selected RF module must be capable of integrating with multiple antenna types to enable longer transmission distances where necessary.

- The RF module must have pin-driven, low-power mode capabilities so that the Mayfly datalogger can decide when the power to its radio is turned on or off.

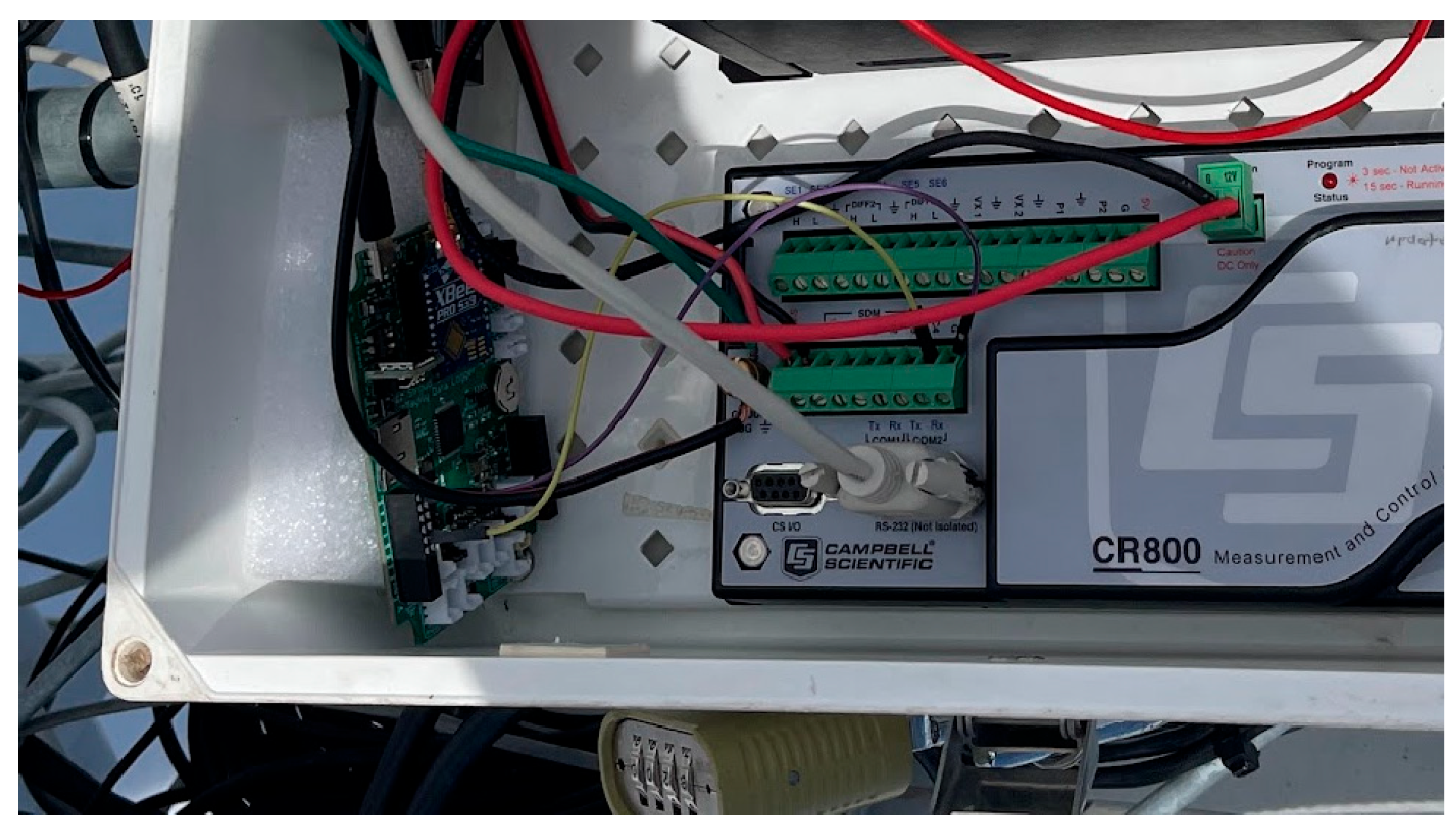

- If expanding on an existing monitoring network that uses dataloggers other than the Mayfly (e.g., a network of Campbell Scientific Dataloggers), the datalogger that will interface with the new network of Mayflies needs to have Universal Asynchronous Receive Transmit (UART) serial capabilities.

2.5.1. 900 MHz Radio Module Selection

2.5.2. LTE Radio Module Selection

2.5.3. Mesh Network Design

2.5.4. Communication Protocols

2.6. Deployment Platform

3. Results

3.1. Case Study Implementations

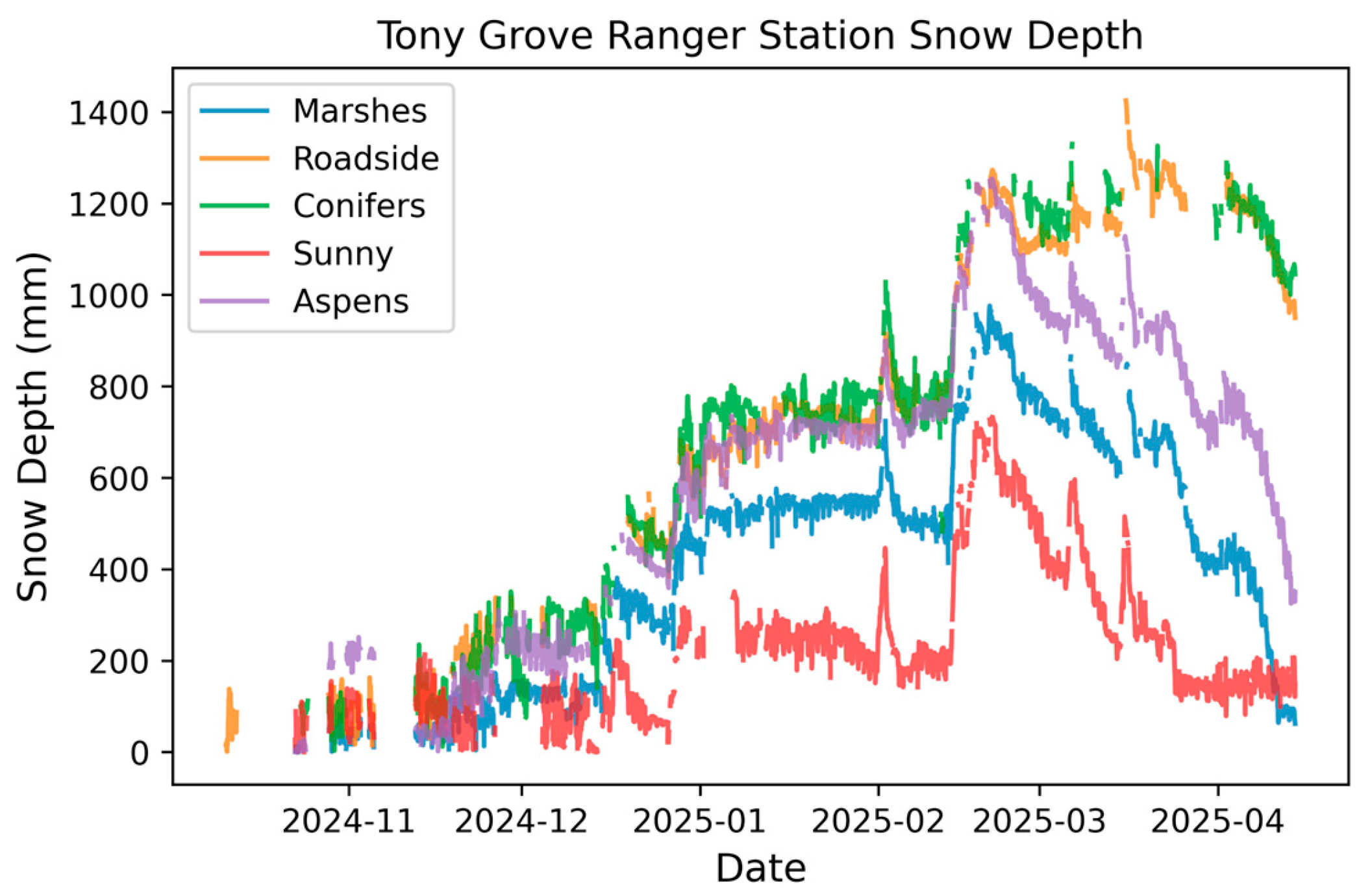

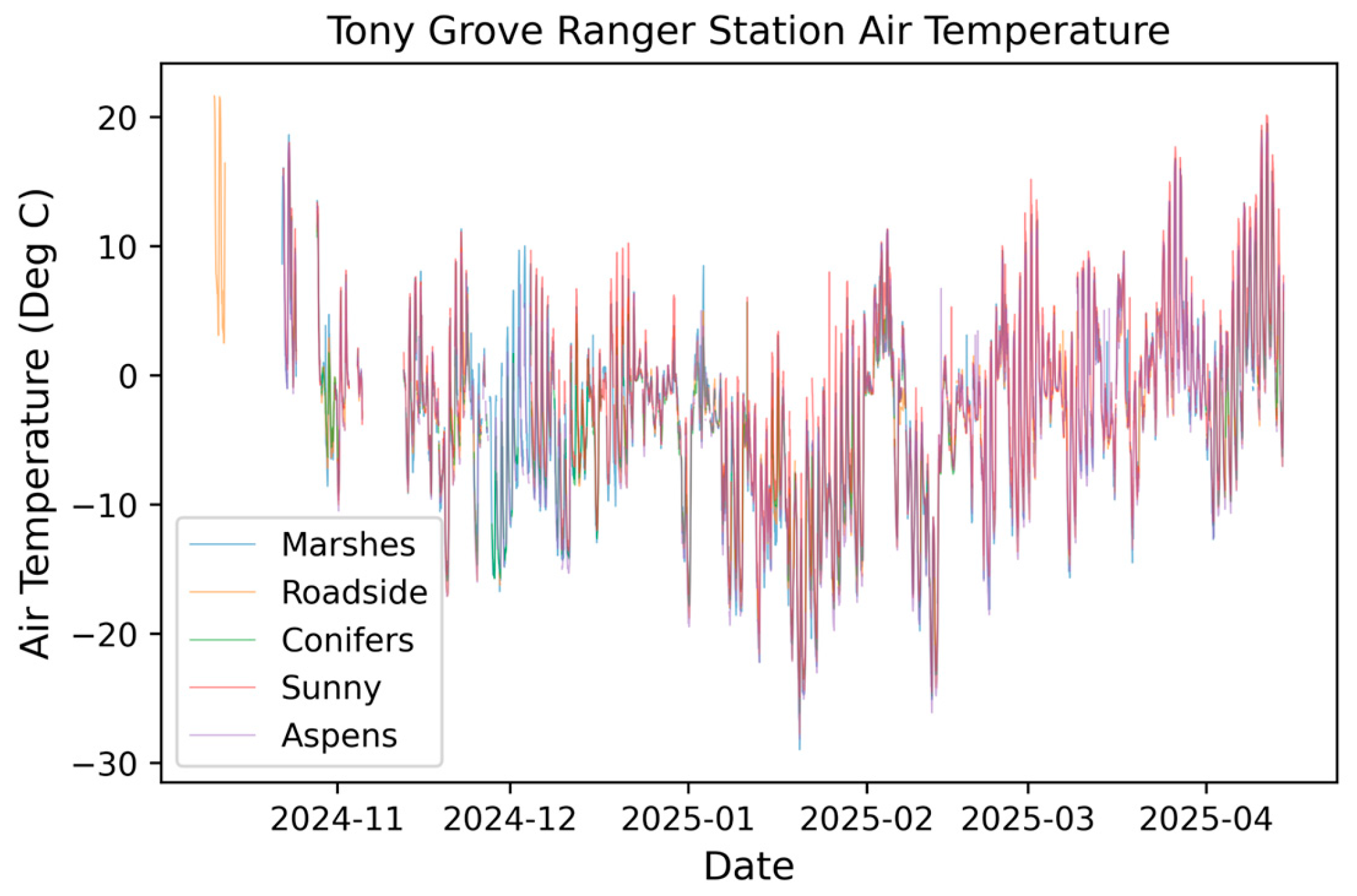

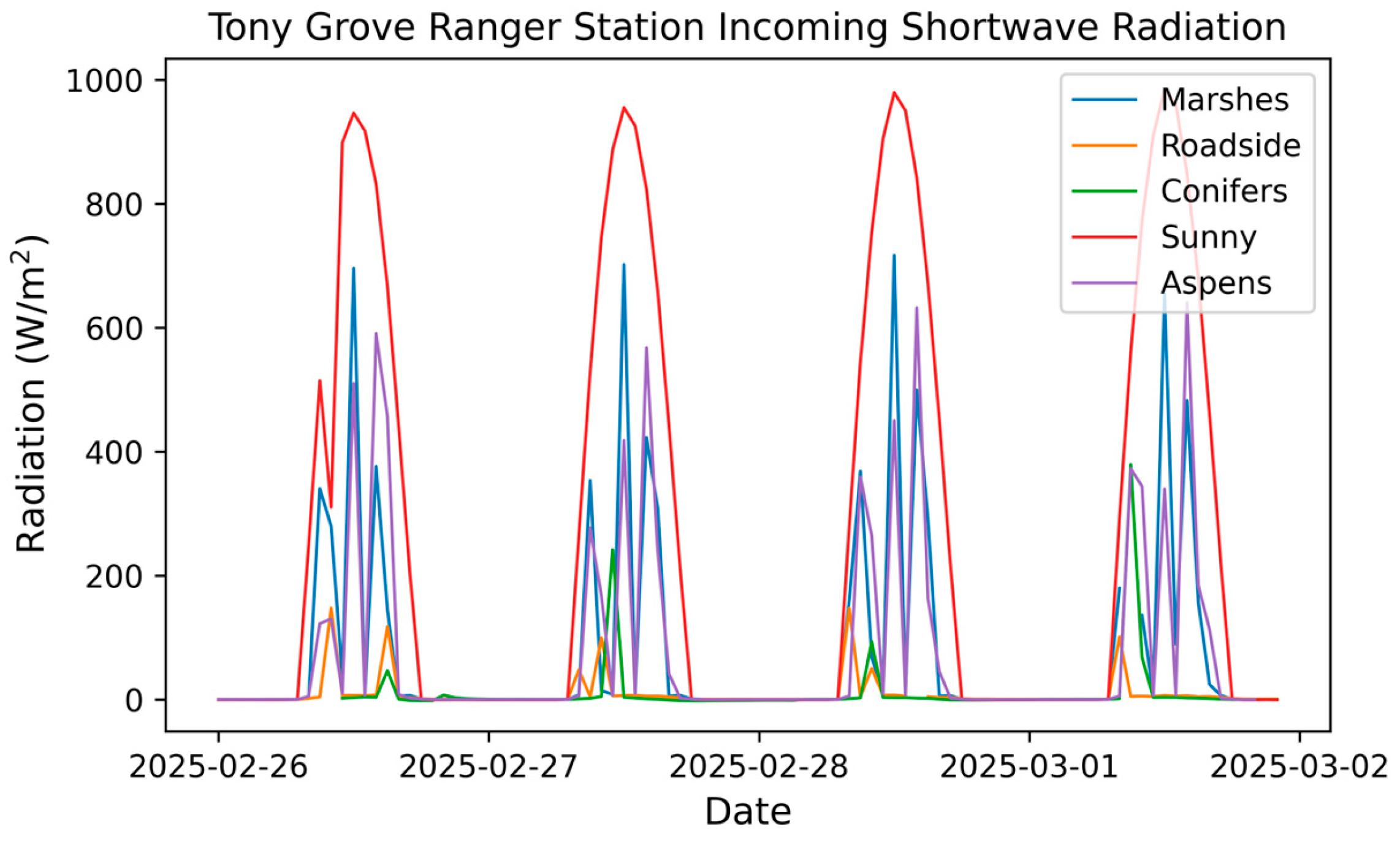

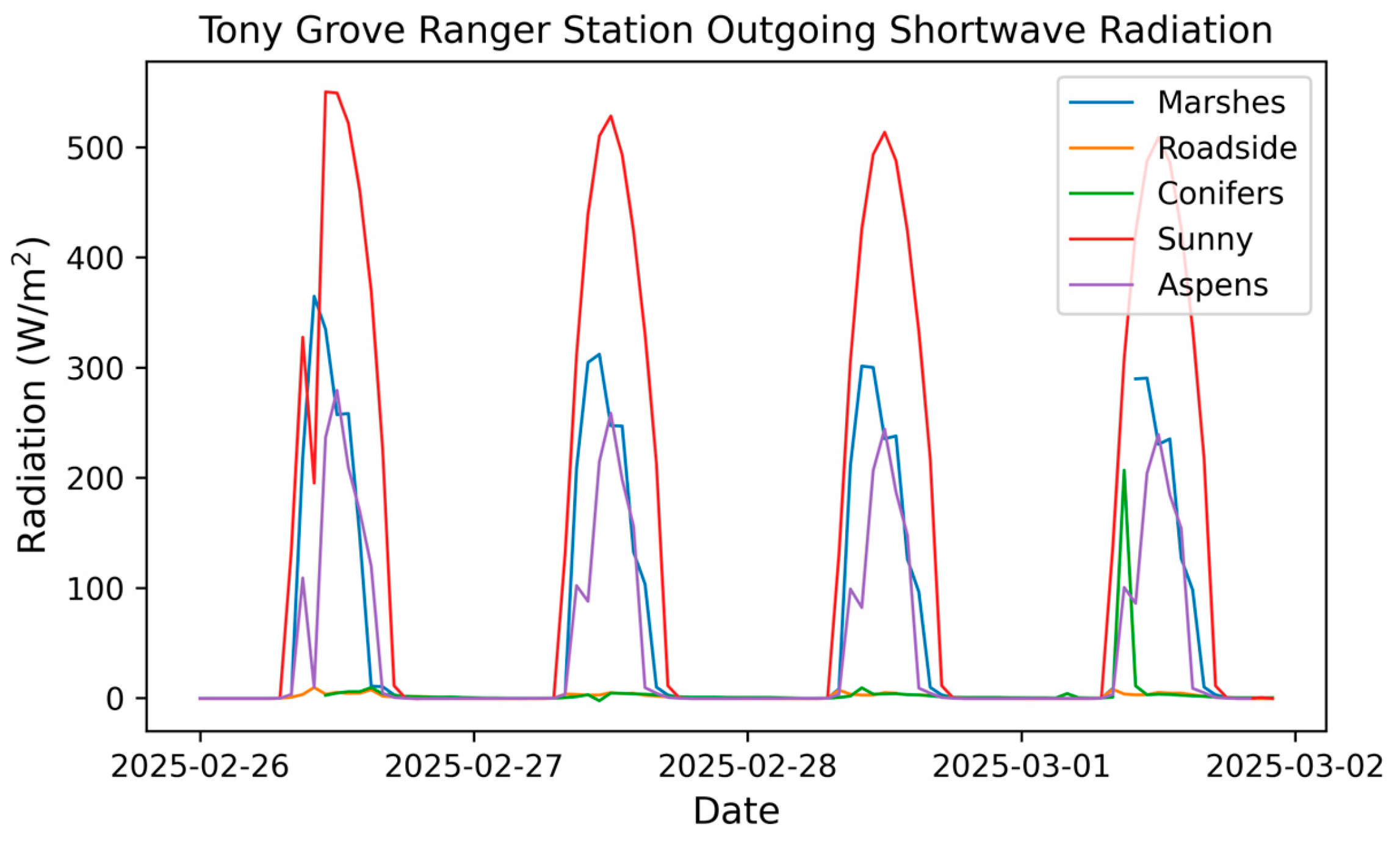

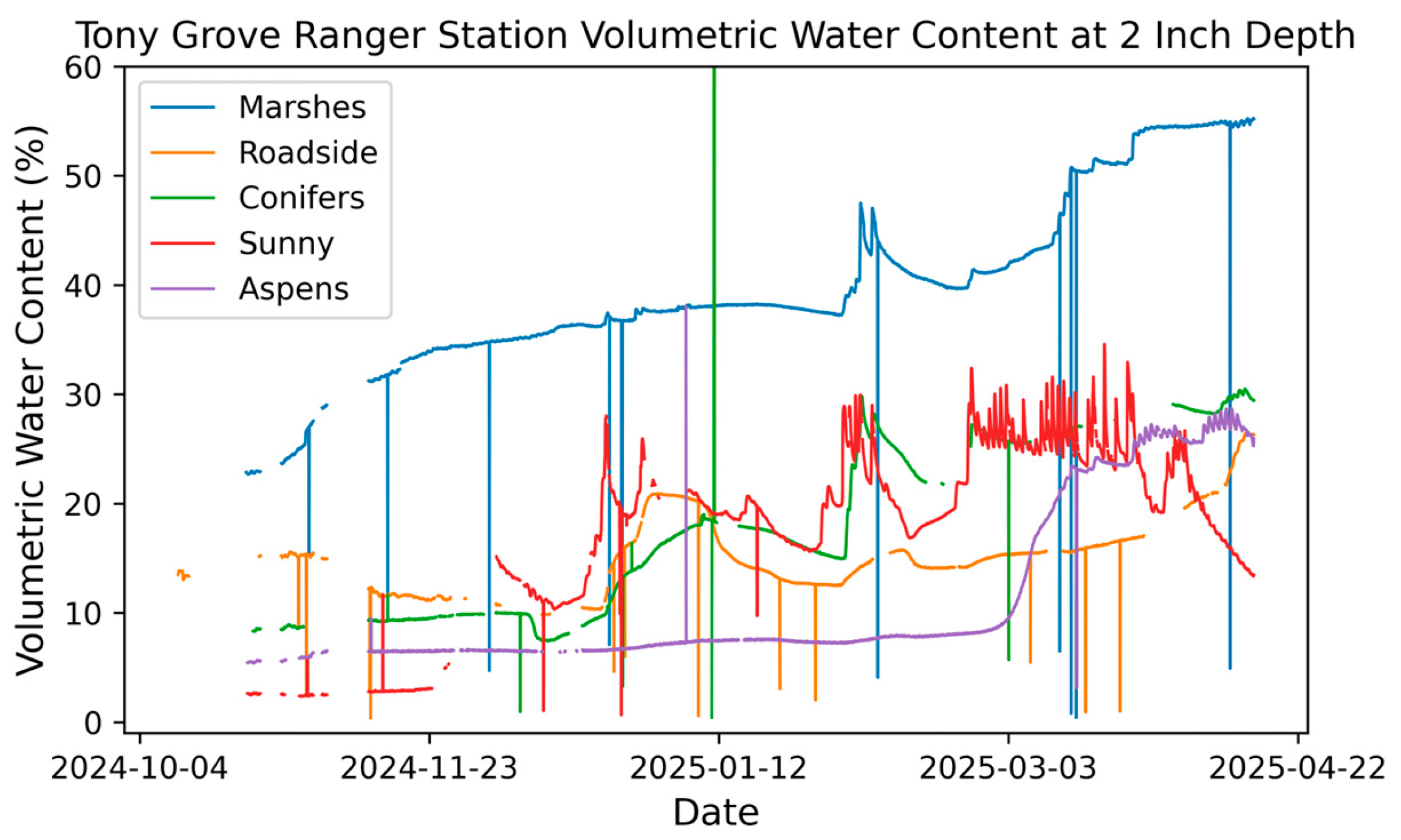

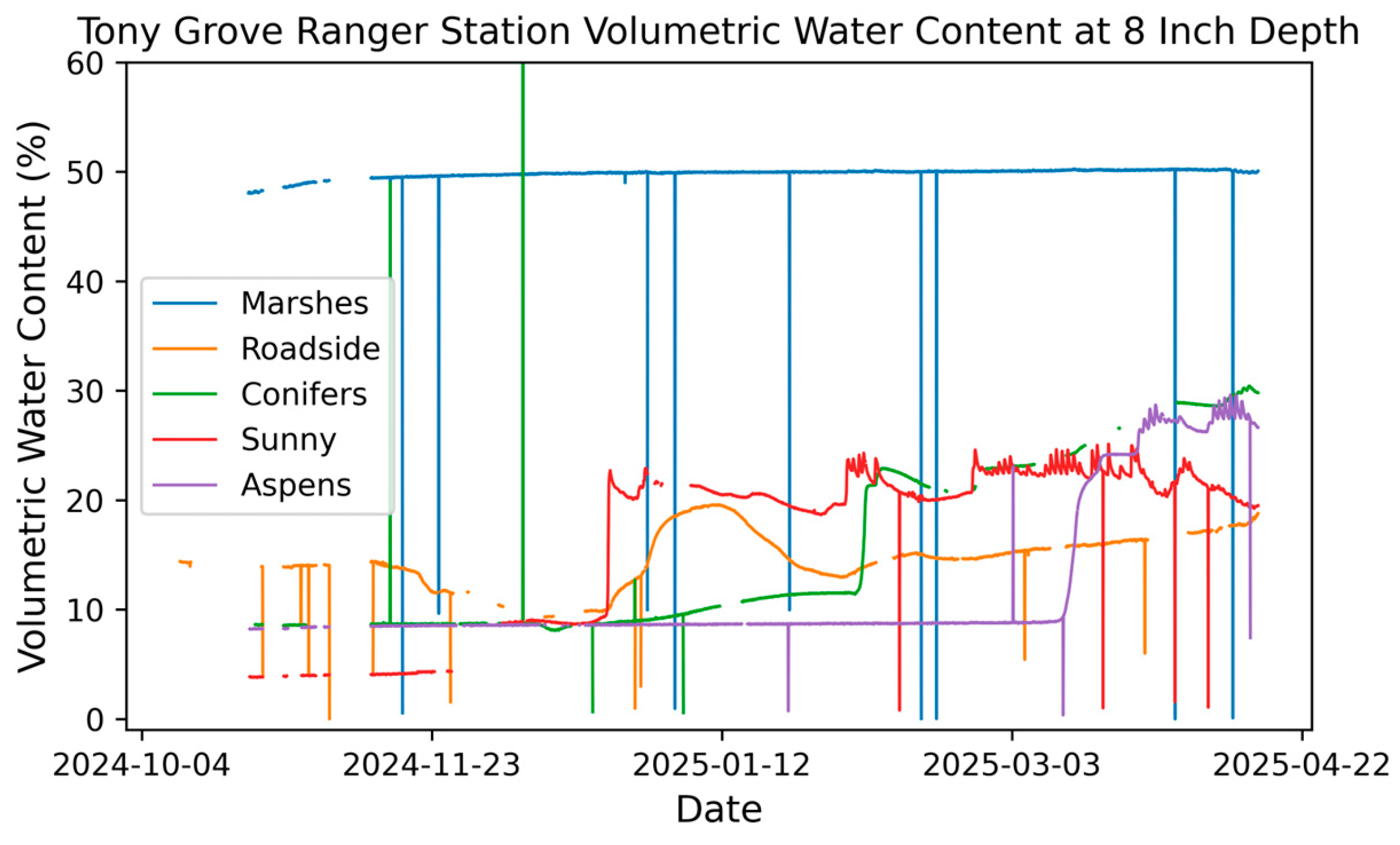

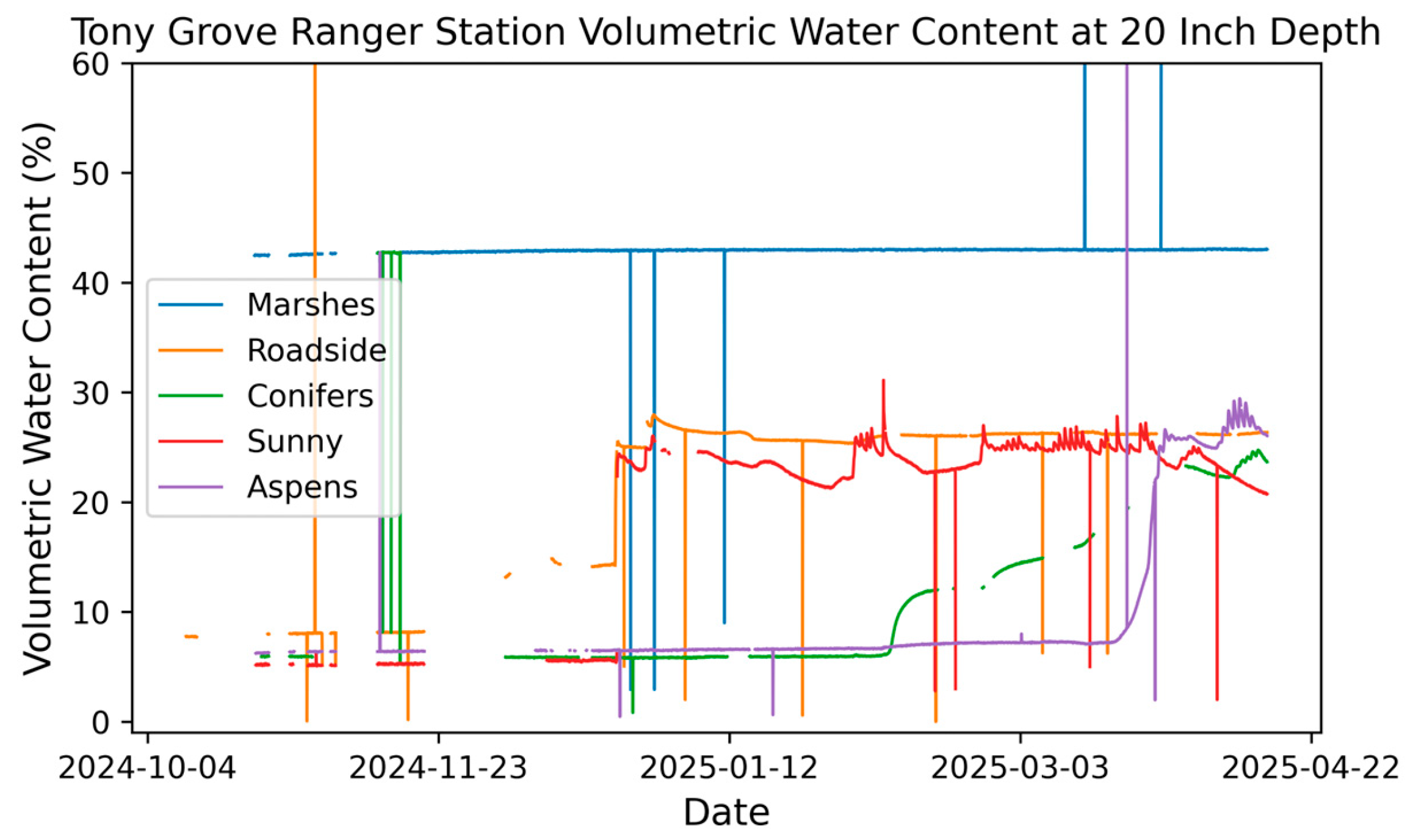

- Roadside: This site was chosen for its mix of coniferous and deciduous trees within the vicinity as well as its north facing aspect and lack of sun exposure.

- Aspens: This site was chosen for its heavy aspen representation, generally east facing aspect, and for having partial day sun exposure.

- Conifers: This site was chosen for its heavy conifer canopy, north facing aspect, and no sun exposure.

- Sunny: This site was chosen for its south-facing aspect, lack of tree canopy, full sun exposure, and dry soils.

- Marshes: This site was chosen for its general flat aspect, consistently wet soil, and aspen tree canopy.

3.1.1. Station Power Considerations

3.1.2. Solar Panel Selection

3.1.3. Station Battery Capacities

3.1.4. Station Charge Controllers

3.1.5. Sensors and Data

3.1.6. Communications and Telemetry

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Software and Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ADC | Analog to digital converter |

| API | Application programming interface |

| CIROH | Cooperative Institute for Research to Operations in Hydrology |

| HIS | Hydrologic Information System |

| I2C | Inter-integrated circuit |

| IDE | Interactive development environment |

| IoT | Internet of Things |

| JSON | JavaScript Object Notation |

| LRO | Logan River Observatory |

| NOAA | National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration |

| NREL | National Renewable Energy Laboratory |

| PCB | Printed circuit board |

| RF | Radio frequency |

| RSMA | Reverse SubMiniature version A |

| SD | Secure digital |

| SLA | Sealed lead acid |

| SMA | SubMiniature version A |

| SNOTEL | SNOwpack TELemetry |

| SWE | Snow water equivalent |

| TGRS | Tony Grove Ranger Station |

| TTL | Transistor-transistor logic |

| UART | Universal Asynchronous Receive Transmit |

| USDA | United States Department of Agriculture |

| USGS | United States Geological Survey |

| UUID | Universally unique identifier |

| UWRL | Utah Water Research Laboratory |

Appendix A

A.1. Meter Teros 12

A.2. MaxBotix MB7374

A.3. Apogee SP-710-SS

A.4. Apogee SL-510-SS and SL-610-SS

A.5. Apogee ST-110-SS

Appendix B

B.1. Snow Depth

B.2. Air Temperature

B.3. Shortwave Radiation

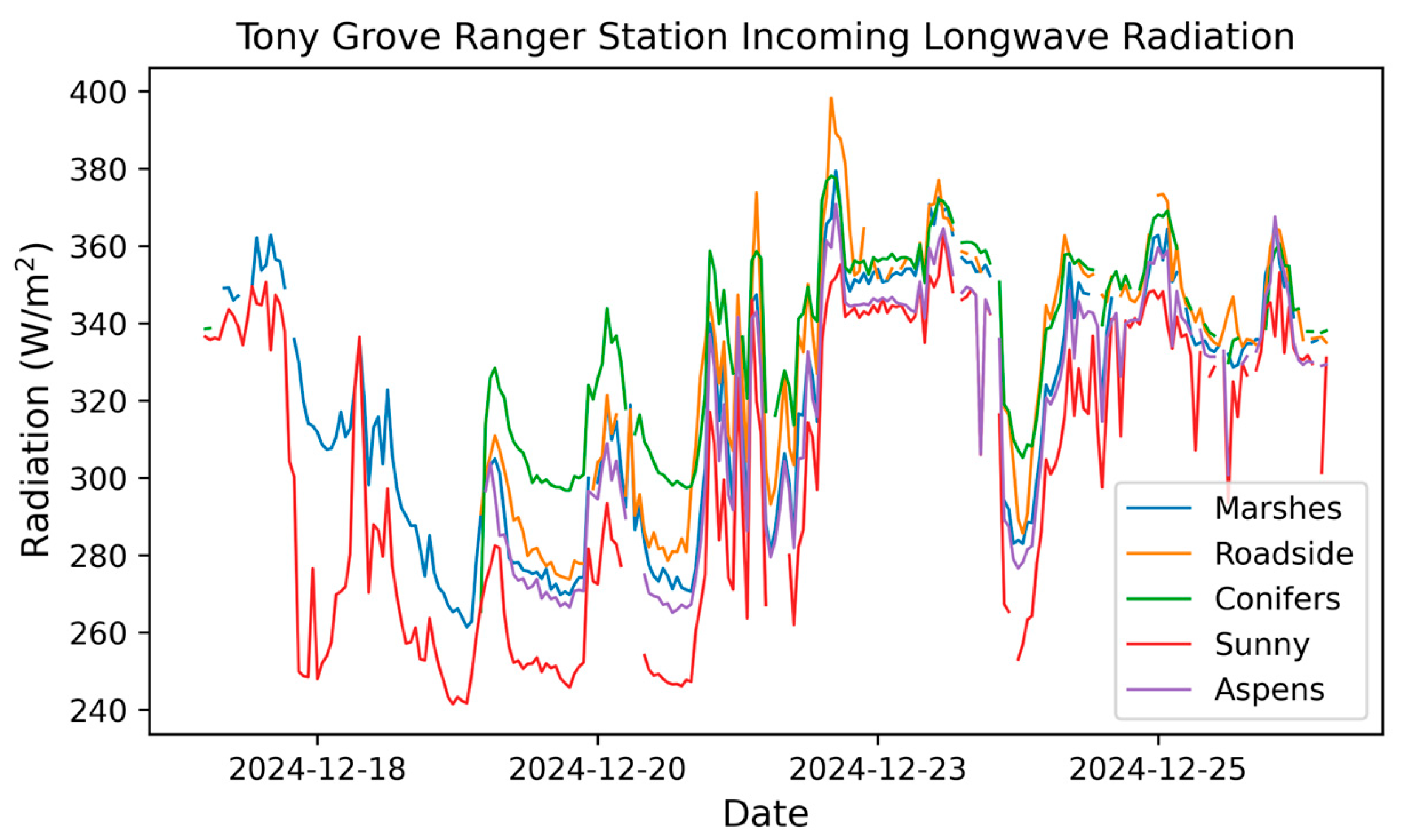

B.4. Longwave Radiation

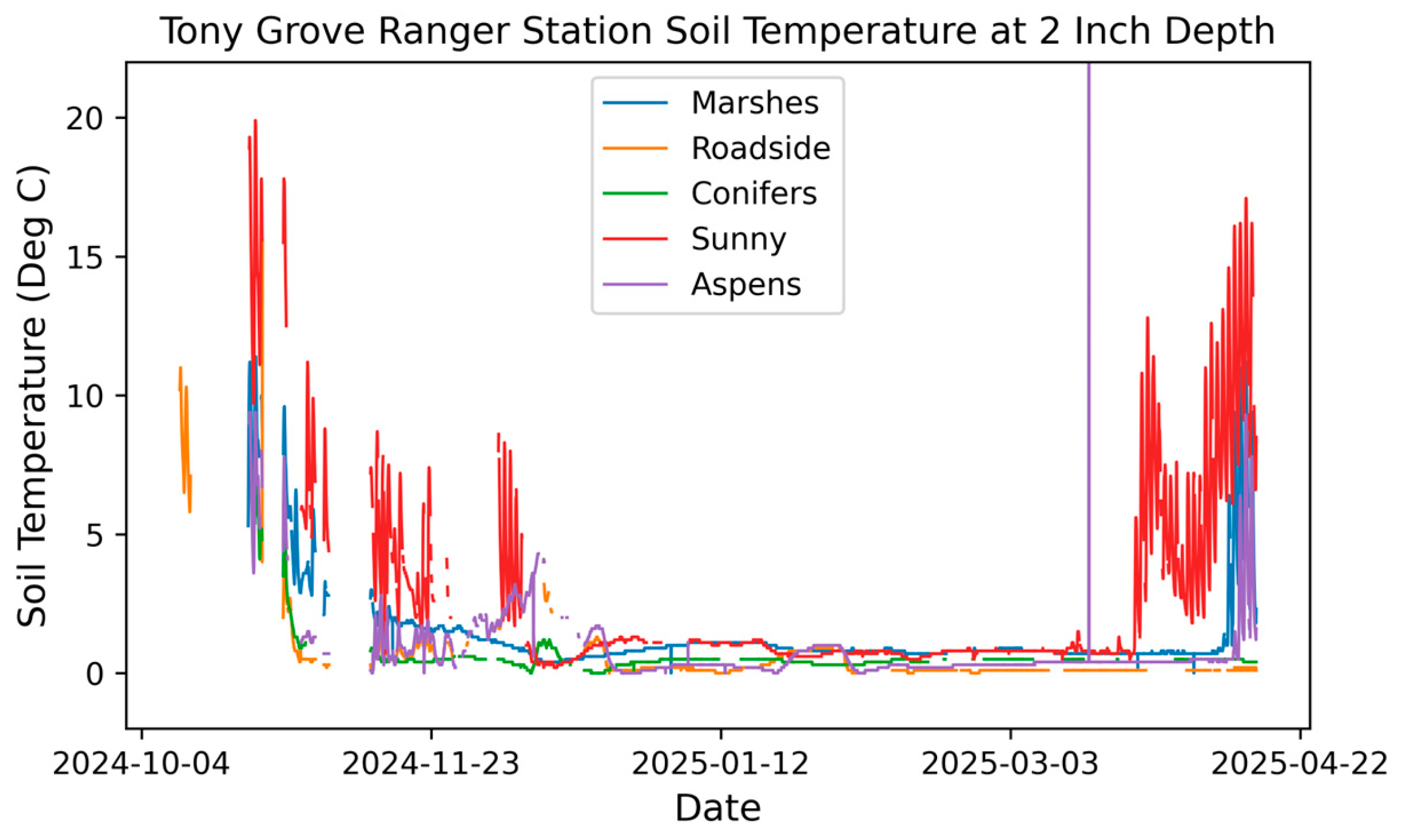

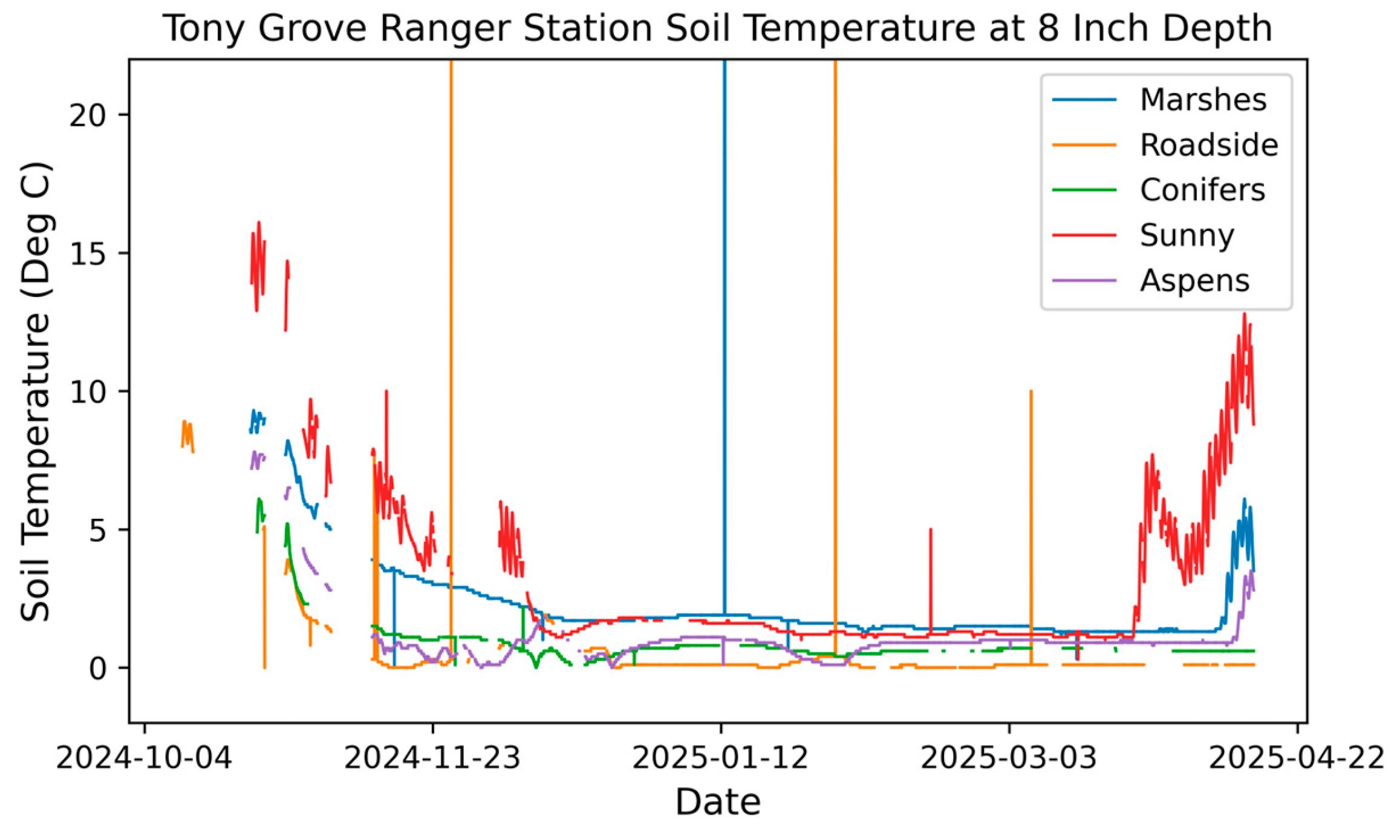

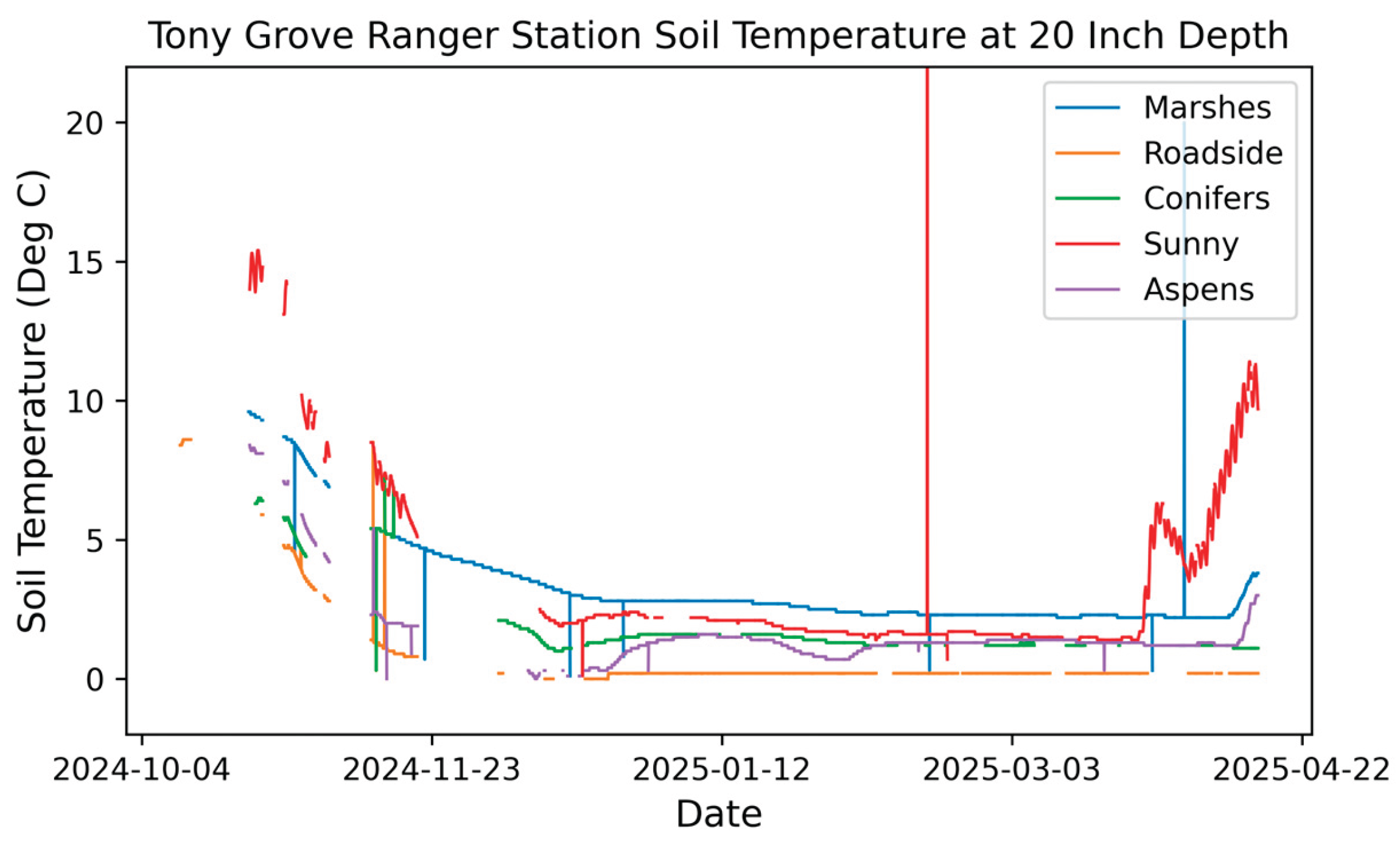

B.5. Soil Temperature

B.6. Soil Volumetric Water Content

References

- Dozier, J.; Bair, E.H.; Davis, R.E. Estimating the spatial distribution of snow water equivalent in the world’s mountains. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Water 2016, 3(3), 461-474. [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Wrzesien, M.L.; Durand, M.; Adam, J.; Lettenmaier, D.P. How much runoff originates as snow in the western United States, and how will that change in the future? Geophys Res Lett 2017, 44(12), 6163–6172. [CrossRef]

- Julander, R.P.; Clayton, J.A. Determining the proportion of streamflow that is generated by cold season processes versus summer rainfall in Utah, USA. J Hydrol Reg Stud 2018, 17, 36–46. [CrossRef]

- Tarboton, D.G.; Luce. C.H. Utah Energy Balance Snow Accumulation and Melt Model (UEB). Computer model technical description and users guide, Utah Water Research Laboratory and USDA Forest Service Intermountain Research Station 1996, https://hydrology.usu.edu/dtarb/snow/snowrep.pdf.

- Tyson, C.; Longyang, Q.; Neilson, B.T.; Zeng, R.; Xu, T. Effects of meteorological forcing uncertainty on high-resolution snow modeling and streamflow prediction in a mountainous karst watershed. J Hydrol 2023, 619, 129304. [CrossRef]

- Clark, M.P.; Nijssen, B.; Lundquist, J.D.; Kavetski, D.; Rupp, D.E.; Woods, R.A.; Freer, J.E.; Gutmann, E.D.; Wood, A.W.; Gochis, D.J.; Rasmussen, R.M.; Tarboton, D.G.; Mahat, V.; Flerchinger, G.N.; Marks, D.G. A unified approach for process-based hydrologic modeling: 2. Model implementation and case studies. Water Resour Res 2015, 51(4), 2515–2542. [CrossRef]

- Meister, R. Influence of strong winds on snow distribution and avalanche activity. Ann Glaciol 1989, 13, 195–201. [CrossRef]

- Luce, C.H.; Lopez-Burgos, V.; Holden, Z. Sensitivity of snowpack storage to precipitation and temperature using spatial and temporal analog models. Water Resour Res 2014, 50(12), 9447–9462. [CrossRef]

- Drake, S.A.; Selker, J.S.; Higgins, C.W. Pressure-driven vapor exchange with surface snow. Front Earth Sci 2019, 7. [CrossRef]

- Strasser, U.; Bernhardt, M.; Weber, M.; Liston, G.E.; Mauser, W. Is snow sublimation important in the alpine water balance? The Cryosphere 2008, 2, 53–66. [CrossRef]

- Barnhart, T.B.; Tague, C.L.; Molotch, N.P. The counteracting effects of snowmelt rate and timing on runoff. Water Resour Res 2020, 56(8), e2019WR026634. [CrossRef]

- Pomeroy, J.W.; Gray, D.M.; Shook, K.R.; Toth, B.; Essery, R.L.H.; Pietroniro, A.; Hedstrom, N. An evaluation of snow accumulation and ablation processes for land surface modelling. Hydrol Process 1998, 12(15), 2339–2367. [CrossRef]

- DeBeer, C.M.; Pomeroy, J.W. Influence of snowpack and melt energy heterogeneity on snow cover depletion and snowmelt runoff simulation in a cold mountain environment. J Hydrol 2017, 553, 199–213. [CrossRef]

- Stewart, B. Measuring what we manage - The importance of hydrological data to water resources management. IAHS-AISH Proceedings and Reports 2015, 80–85. [CrossRef]

- Fleming, S.W.; Zukiewicz, L.; Strobel, M.L.; Hofman, H.; Goodbody, A.G. SNOTEL, the Soil Climate Analysis Network, and water supply forecasting at the Natural Resources Conservation Service: Past, present, and future. J Am Water Resour Assoc. 2023, 59(4), 585-599. [CrossRef]

- World Meteorological Organization. The 2022 GCOS ECVs Requirements. World Meteorological Society e-Library 2022, GCOS-245, https://library.wmo.int/idurl/4/58111.

- Molotch, N.P.; Bales, R.C. Scaling snow observations from the point to the grid element: Implications for observation network design. Water Resour Res 2005, 41(11), 1–16. [CrossRef]

- United States Department of Agriculture. Chapter 3: Data Site Selection. Part 622 Snow Survey and Water Supply Forecasting National Engineering Handbook 2011, https://directives.nrcs.usda.gov//sites/default/files2/1720456649/Chapter%203%20-%20Data%20Site%20Selection.pdf.

- United States Department of Agriculture. Chapter 4: Site Installation. Part 622 Snow Survey and Water Supply Forecasting National Engineering Handbook 2014, https://directives.nrcs.usda.gov//sites/default/files2/1720456672/Chapter%204%20-%20Site%20Installation.pdf.

- Molotch, N.P.; Bales, R.C. SNOTEL representativeness in the Rio Grande headwaters on the basis of physiographics and remotely sensed snow cover persistence. Hydrol Process 2006, 20(4), 723–739. [CrossRef]

- Hund, S.V.; Johnson, M.S.; Keddie, T. Developing a hydrologic monitoring network in data-scarce regions using open-source Arduino dataloggers. Agricultural & Environmental Letters 2016, 1(1), 160011. [CrossRef]

- Pacheco, C.J.B.; Horsburgh, J.S.; Tracy, J.R. A low-cost, open source monitoring system for collecting high temporal resolution water use data on magnetically driven residential water meters. Sensors 2020, 20(13), 1–30. [CrossRef]

- Iribarren Anacona, P.; Luján, J.P.; Azócar, G.; Mazzorana, B.; Medina, K.; Durán, G.; Rojas, I.; Loarte, E. Arduino data loggers: A helping hand in physical geography. Geographical Journal 2022, 189(2), 314-328. [CrossRef]

- Filhol, S.; Lefeuvre, P.-M.; Ibañez, J.D.; Hulth, J.; Hudson, S.R.; Gallet, J.-C.; Schuler, T.V.; Burkhart, J.F. A new approach to meteorological observations on remote polar glaciers using open-source internet of things technologies. Front Environ Sci 2023, 11. [CrossRef]

- Pohl, S.; Garvelmann, J.; Wawerla, J.; Weiler; M. Potential of a low-cost sensor network to understand the spatial and temporal dynamics of a mountain snow cover. Water Resour Res 2014, 50(3), 2533–2550. [CrossRef]

- Abdelal, Q.; Al-Hmoud, A. Low-cost, low-energy, wireless hydrological monitoring platform: Design, deployment, and evaluation.” J Sens 2021. [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, M.D.; Dumontier, M.; Aalbersberg, I.J.; Appleton, G.; Axton, M.; Baak, A.; Blomberg, N.; Boiten, J.W.; da Silva Santos, L.B.; Bourne, P.E.; Bouwman, J.; Brookes, A.J.; Clark, T.; Crosas, M.; Dillo, I.; Dumon, O.; Edmunds, S.; Evelo, C.T.; Finkers, R.; Gonzalez-Beltran, A.; Gray, A.J.G.; Groth, P.; Goble, C.; Grethe, J.S.; Heringa, J.; Hoen, P.A.C.t; Hooft, R.; Kuhn, T.; Kok, R.; Kok, J.; Lusher, S.J.; Martone, M.E.; Mons, A.; Packer, A.L.; Persson, B.; Rocca-Serra, P.; Roos, M.; van Schaik, R.; Sansone, S.A.; Schultes, E.; Sengstag, T.; Slater, T.; Strawn, G.; Swertz, M.A.; Thompson, M.; Van Der Lei, J.; Van Mulligen, E.; Velterop, J.; Waagmeester, A.; Wittenburg, P.; Wolstencroft, K.; Zhao, J.; Mons, B. The FAIR Guiding Principles for scientific data management and stewardship. Sci Data 2016, 3, 160018. [CrossRef]

- Mahbub, M. Design and implementation of multipurpose radio controller unit using nRF24L01 wireless transceiver module and Arduino as MCU. International Journal of Digital Information and Wireless Communications 2019, 9(2), 61–72. [CrossRef]

- Nordic Semiconductor. nRF24L01+ Single Chip 2.4GHz Transceiver. 2008, https://cdn.sparkfun.com/assets/3/d/8/5/1/nRF24L01P_Product_Specification_1_0.pdf.

- Nedelkovski, D. Arduino wireless weather station project. 2018, Accessed February 2, 2025. https://howtomechatronics.com/tutorials/arduino/arduino-wireless-communication-nrf24l01-tutorial/.

- Sadler, J.M.; Ames, D.P.; Khattar, R. A recipe for standards-based data sharing using open source software and low-cost electronics. Journal of Hydroinformatics 2016, 18(2), 185–197. [CrossRef]

- Kerkez, B.; Glaser, S.D.; Bales, R.C.; Meadows, M.W. Design and performance of a wireless sensor network for catchment-scale snow and soil moisture measurements. Water Resour Res 2012, 48(9). [CrossRef]

- EnviroDIY. Getting started with the Mayfly data logger. 2025, Accessed January 12, 2025. https://www.envirodiy.org/mayfly/.

- EnviroDIY. 2025. Mayfly data logger hardware. 2025, Accessed January 12, 2025. https://www.envirodiy.org/mayfly/hardware/.

- Damiano, S. ModularSensors: An Arduino library to give environmental sensors a common interface of functions for use with Arduino-framework dataloggers, such as the EnviroDIY Mayfly. 2024, Accessed January 29, 2025. https://github.com/EnviroDIY/ModularSensors.

- Adafruit. ADS1115 16-bit ADC. 2025, Accessed January 12, 2025. https://www.adafruit.com/product/1085.

- Seeed Technology Company. Grove—2-coil latching relay. 2025, Accessed January 12, 2025. https://www.seeedstudio.com/Grove-2-Coil-Latching-Relay.html?srsltid=AfmBOorvhjtxsKd7fymKXFh9oEJSwrF_SNlV7I7oKoSTy3MO-4ieg_R1.

- Hicks, S. How to determine battery and power supply. 2024, Accessed January 22, 2025. https://www.envirodiy.org/topic/how-to-determine-battery-and-power-supply/.

- Power Sonic Corporation. The complete guide to lithium vs lead acid batteries. 2025, Accessed January 22, 2025. https://www.power-sonic.com/blog/lithium-vs-lead-acid-batteries/#:~:text=COLD%20TEMPERATURE%20BATTERY%20PERFORMANCE,is%20below%2032%C2%B0F.

- Albright G.; Edie, J.; Al-Hallaj, S. A comparison of lead acid to lithium-ion in stationary storage applications. AllCell Technologies LLC 2012, Accessed January 29, 2025. https://www.batterypoweronline.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/07/Lead-acid-white-paper.pdf.

- SOLPERK. SOLPERK 10A solar charge controller. 2025, Accessed January 29, 2025. https://solperk.shop/products/solperk-10a-solar-charge-controller-waterproof-solar-panel-controller-12v-24v-pwm-solar-panel-battery-intelligent-regulator-for-rv-boat-car-with-led-display.

- National Renewable Energy Laboratory. PVWatts Calculator. 2025, Accessed January 12, 2025. https://pvwatts.nrel.gov/.

- Digi. Digi XBee-Pro 900HP RF Module. 2025, Accessed January 29, 2025. https://www.digi.com/products/embedded-systems/digi-xbee/rf-modules/sub-1-ghz-rf-modules/xbee-pro-900hp.

- EnviroDIY. EnviroDIY LTE Bee. 2025, Accessed January 29, 2025. https://www.envirodiy.org/product/envirodiy-lte-bee/.

- Digi. XBee®-PRO 900HP/XSC RF Modules S3 and S3B user guide. 2020, Accessed January 29, 2025. https://docs.digi.com/resources/documentation/digidocs/pdfs/90002173.pdf.

- Torres, J.P.N.; Nashih, S.K.; Fernandes, C.A.F.; Leite, J.C. The effect of shading on photovoltaic solar panels. Energy Systems 2018, 9(1), 195–208. [CrossRef]

- Horsburgh, J.S.; Lippold, K.; Slaugh, D.L.; Ramirez, M. Adapting OGC’s SensorThings API and data model to support data management and sharing for environmental sensors. Environmental Modelling and Software 2025, 183, 106241. [CrossRef]

- Horsburgh, J.S.; Lippold, K.; Slaugh, D.L. HydroServer: A software stack supporting collection, communication, storage, management, and sharing of data from in situ environmental sensors. Environmental Modelling and Software 2025, 193, 106637. [CrossRef]

- Dority, B.; Horsburgh, J.S. snow_sensing: Hardware and software for lower cost snow monitoring stations. 2025, Accessed January 12, 2025. https://github.com/CIROH-Snow/snow_sensing.

- Dority, B.; Horsburgh, J.S. Increasing the spatial resolution of snow hydrology data and augmenting existing hydrology monitoring networks using low-cost snow sensing stations. HydroShare 2025. https://www.hydroshare.org/resource/c6a97963db734091a4ad22602c9cdd57.

- METER Group. TEROS 12: Advanced soil moisture sensor + temperature and EC. 2025, Accessed January 29, 2025. https://metergroup.com/products/teros-12/.

- MaxBotix. MB7374 HRXL-MaxSonar-WRST7. 2025, Accessed January 29, 2025. https://maxbotix.com/products/mb7374.

- Apogee Instruments. Thermopile pyranometer support. 2025, Accessed January 22, 2025. https://www.apogeeinstruments.com/thermopile-pyranometer-support/.

- Apogee Instruments. SL-510-SS: Pyrgeometer upward-looking. 2025, Accessed January 29, 2025. https://www.apogeeinstruments.com/sl-510-ss-pyrgeometer-upward-looking/.

- Apogee Instruments. SL-610-SS: Pyrgeometer downward-looking. 2025, Accessed January 29, 2025. https://www.apogeeinstruments.com/sl-610-ss-pyrgeometer-downward-looking/.

- Apogee Instruments. SN-500-SS: Net Radiometer. 2025, Accessed January 29, 2025. https://www.apogeeinstruments.com/sn-500-ss-net-radiometer/.

- Apogee Instruments. ST-110-SS: Thermistor temperature sensor. 2025, Accessed March 6, 2025. https://www.apogeeinstruments.com/st-110-ss-thermistor-temperature-sensor/.

| Sensors | Quantity | Unit Price | Total Price |

|---|---|---|---|

| METER Teros 12 Soil Sensors (3 depths) | 3 | $258.00 | $774.00 |

| MaxBotix MB7374 Snow Depth Sensor | 1 | $134.00 | $134.00 |

| Apogee SL-510-SS Pyrgeometer | 1 | $599.00 | $599.00 |

| Apogee SL-610-SS Pyrgeometer | 1 | $599.00 | $599.00 |

| Apogee SP-710-SS Pyranometer package | 1 | $663.00 | $663.00 |

| Apogee ST-110-SS Air Temperature Sensor | 1 | $85.00 | $85.00 |

| Sensors Total | $2,854.00 |

| Datalogger and Peripherals | Quantity | Unit Price | Total Price |

|---|---|---|---|

| EnviroDIY Mayfly Datalogger | 1 | $120.00 | $120.00 |

| CR1220 Coin cell battery | 1 | $1.12 | $1.12 |

| Grove cable connectors pack | 2 | $3.50 | $7.00 |

| Grove screw terminals | 4 | $1.70 | $6.80 |

| XBee S3B RF Module | 1 | $79.00 | $79.00 |

| Omnidirectional 900 MHz antenna | 1 | $3.99 | $3.99 |

| 3-port lever wire connectors (pack of 10) | 1 | $7.98 | $7.98 |

| MicroSD card (pack of 2) | 1 | $6.23 | $6.23 |

| EnvrioDIY grove to 3.5mm stereo jack | 3 | $7.00 | $21.00 |

| Compact wire splice connector quick terminal block | 2 | $2.87 | $5.74 |

| Prototype PCB solderable breadboard | 1 | $1.70 | $1.70 |

| Adafruit ADS1115 ADC | 2 | $14.95 | $29.90 |

| 6-pin PCB screw terminal block connector | 4 | $0.81 | $3.24 |

| Jumper cables (male-to-male) (pack of 120) | 1 | $6.88 | $6.88 |

| I2C Qwiic cable pack | 1 | $9.99 | $9.99 |

| PVC Jacketed 22 Gauge 5 conductor wire - cabling for MaxBotix sensor | 10 | $0.59 | $5.90 |

| Datalogger and Communications Total | $316.47 |

| Power Components | Quantity | Unit Price | Total Price |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2-coil latching relay | 1 | $7.60 | $7.60 |

| 10 W solar panel with mounting bracket | 1 | $214.00 | $214.00 |

| 12V 35Ah sealed lead acid battery | 1 | $86.99 | $86.99 |

| CH150 12 V charging regulator | 1 | $312.00 | $312.00 |

| 12V DC to 5V USB-C female DC step-down converter | 1 | $8.99 | $8.99 |

| Primary wire (black) | 1 | $7.54 | $7.54 |

| Primary wire (red) | 1 | $6.63 | $6.63 |

| 16 AWG extension cable for solar panel (25-ft length) | 1 | $15.50 | $15.50 |

| Alligator clips | 2 | $0.67 | $1.34 |

| Power Total | $660.59 |

| Power Components | Quantity | Unit Price | Total Price |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2-coil latching relay | 1 | $7.60 | $7.60 |

| 30 W solar panel and 12 V solar charger | 1 | $74.99 | $74.99 |

| 12V 35Ah sealed lead acid battery | 1 | $86.99 | $86.99 |

| 12V DC to 5V USB-C female DC step-down converter | 1 | $8.99 | $8.99 |

| Primary wire (black) | 1 | $7.54 | $7.54 |

| Primary wire (red) | 1 | $6.63 | $6.63 |

| 16 AWG extension cable for solar panel (25-ft length) | 1 | $15.50 | $15.50 |

| Alligator Clips | 2 | $0.67 | $1.34 |

| Power Total | $209.58 |

| Setting Name | Value | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Network ID (ID) | *varies* | A meaningful ID for all radio stations on the same network. Helps privatize the network. |

| Unicast Mac Retries (RR) | F | Maximum number of times the radio module will attempt to establish communication with neighboring radios. |

| Mesh Unicast Retries (MR) | 5 | Number of times a network of radio modules attempts to get a message from its source to its endpoint, 5 being the maximum. |

| Node Identifier (NI) | *varies* | A meaningful name for the station the module is used at. |

| Transmit Options (TO) | C0 | Sets the module to operate in Digi’s mesh configuration. |

| API Enable (AP) | API Mode Without Escapes |

Sets the data frame format as API mode and does not include escape characters. |

| Sleep Mode (SM) | Asynchronous Pin Sleep |

Configures the radio module to operate in a power saving mode unless woken up by driving a sleep pin low. |

| Platform Components | Quantity | Unit Price | Total Price |

|---|---|---|---|

| CM106B 10’ Campbell Scientific tripod and grounding kit | 1 | $926.40 | $926.40 |

| Campbell Scientific guy wire kit | 1 | $385.00 | $385.00 |

| CM206 6’ Campbell Sci. instrumentation crossarm with mounting bracket | 1 | $162.24 | $162.24 |

| Pelican 1450 weather proof case for instrumentation | 1 | $162.95 | $162.95 |

| U-bolts | 2 | $2.08 | $4.16 |

| AM-130 Albedometer Mounting Fixture with 12” Rod | 2 | $42.00 | $84.00 |

| AM-240: Rod-based Mounting Fixture | 2 | $84.00 | $168.00 |

| MaxBotix MB7950 Mounting Hardware | 1 | $3.43 | $3.43 |

| Command strips package | 1 | $9.98 | $9.98 |

| Polycase HD-22F NEMA Polycarbonate Enclosure for Maxbotix sensor | 1 | $7.40 | $7.40 |

| Cable glands package | 1 | $8.49 | $8.49 |

| Radiation shield for air temperature sensor | 1 | $54.99 | $54.99 |

| UV-resistant zip ties pack | 1 | $7.49 | $7.49 |

| Duct seal (16 oz.) | 1 | $4.68 | $4.68 |

| Southwire 3/4” aluminum conduit | 4 | $1.03 | $4.12 |

| Mounting Total | $1,993.33 |

| Platform Components | Quantity | Unit Price | Total Price |

|---|---|---|---|

| Down guy wire kit | 1 | $52.00 | $52.00 |

| Galvanized steel fence post mast | 1 | $28.77 | $28.77 |

| U-post | 1 | $5.98 | $5.98 |

| Grounding cable | 4 | $1.98 | $7.92 |

| Grounding rod and wire clamp | 1 | $19.70 | $19.70 |

| Grounding clamp | 1 | $8.98 | $8.98 |

| Rebar stakes | 1 | $20.49 | $20.49 |

| CM206 6’ Campbell Sci. instrumentation crossarm with mounting bracket | 1 | $162.24 | $162.24 |

| Pelican 1450 weather proof case for instrumentation | 1 | $162.95 | $162.95 |

| U-bolts | 2 | $2.08 | $4.16 |

| AM-130 Albedometer Mounting Fixture with 12” Rod | 2 | $42.00 | $84.00 |

| AM-240: Rod-based Mounting Fixture | 2 | $84.00 | $168.00 |

| MaxBotix MB7950 Mounting Hardware | 1 | $3.43 | $3.43 |

| Command strips package | 1 | $9.98 | $9.98 |

| Polycase HD-22F NEMA Polycarbonate Enclosure for Maxbotix sensor | 1 | $7.40 | $7.40 |

| Cable glands package | 1 | $8.49 | $8.49 |

| Radiation shield for air temperature sensor | 1 | $54.99 | $54.99 |

| UV-resistant zip ties pack | 1 | $7.49 | $7.49 |

| Duct seal (16 oz.) | 1 | $4.68 | $4.68 |

| Southwire 3/4” aluminum conduit | 4 | $1.03 | $4.12 |

| Mounting Total | $825.77 |

| Process | Current In (mA) |

Time Duration (minutes) |

Portion Cycle pn |

Inpn (mA) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quiescent | 20 | 32.5 | 0.54 | 10.8 |

| Heaters On | 92 | 20 | 0.33 | 30.4 |

| Logging | 34 | 0.5 | 0.01 | 0.3 |

| Data Transmission | 40 | 7 | 0.12 | 4.8 |

| Total | -- | 60 | 1.00 | 46.3 |

| Station | Ireq (A) | Vreq (V) | NREL Lowest Solar Power (kWh) | Minimum Power (W) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Marshes | 0.046 | 12 | 1.30 | 10.3 |

| Aspens | 0.046 | 12 | 1.30 | 10.3 |

| Sunny | 0.046 | 12 | 2.60 | 5.1 |

| Roadside | 0.046 | 12 | 0 | Undefined |

| Conifers | 0.046 | 12 | 0 | Undefined |

| Station | Load (A) |

Time (h) |

Efficiency | Required Capacity (Ah) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sunny | 0.046 | 168 | 0.60 | 12.9 |

| Marshes | 0.046 | 168 | 0.60 | 12.9 |

| Aspens | 0.046 | 168 | 0.60 | 12.9 |

| Station | Load (A) |

Battery Capacity (Ah) | Efficiency | Time (days) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Roadside | 0.046 | 100 | 0.90 | 81 |

| Conifers | 0.046 | 100 | 0.90 | 81 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).