Submitted:

30 December 2025

Posted:

30 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

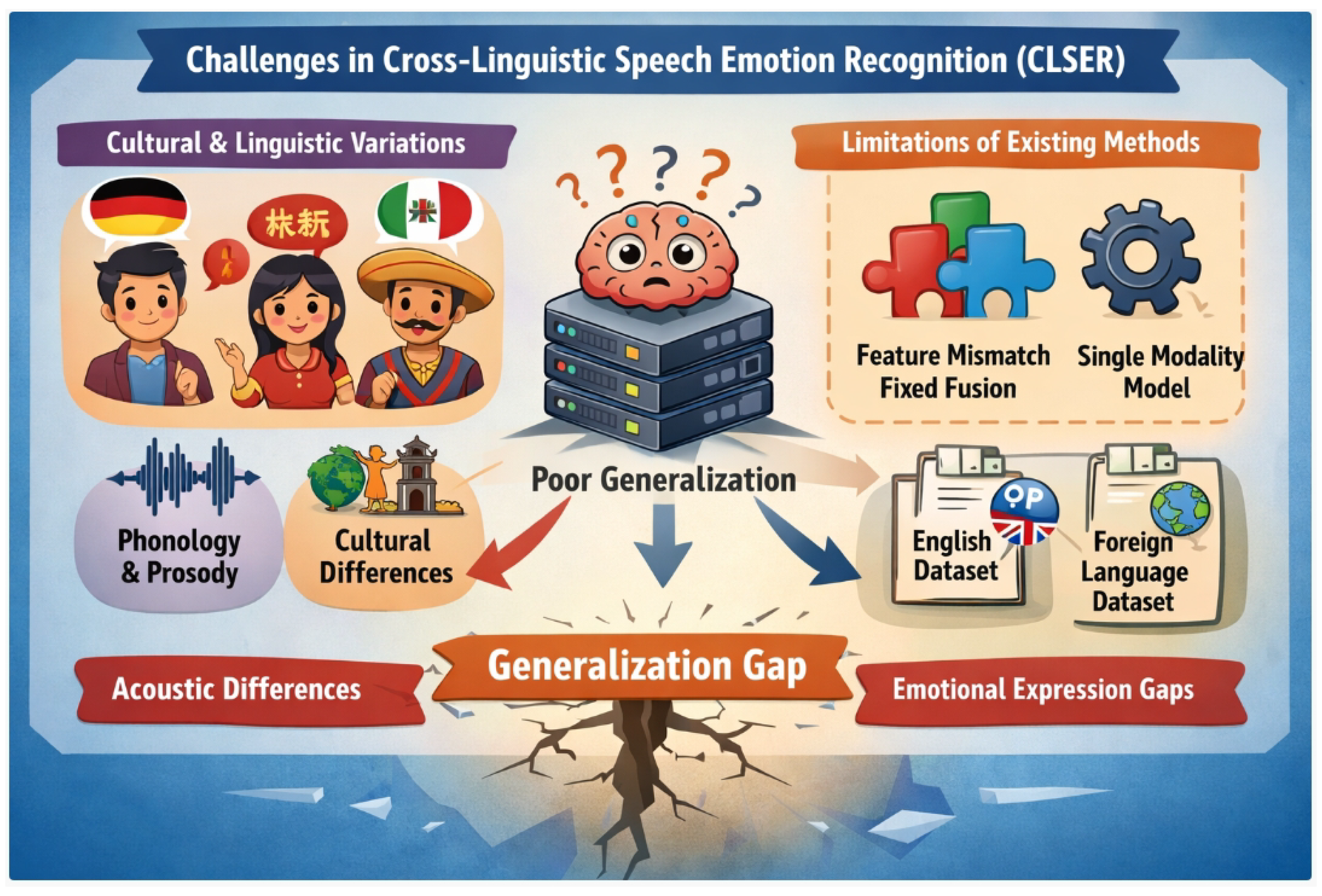

1. Introduction

- We propose the Adaptive Contextualized Multi-feature Fusion Network (ACMF-Net), a novel architecture for CLSER that effectively integrates heterogeneous speech features based on a “contextualize first, then adaptively fuse” paradigm.

- We introduce a novel Dynamic Gating mechanism within ACMF-Net, which adaptively learns to weigh the contributions of different feature modalities, significantly enhancing robustness against cross-linguistic feature discrepancies.

- We demonstrate the superior performance of ACMF-Net on a source language dataset (IEMOCAP) against strong baselines and existing multi-feature fusion models, highlighting its potential for robust generalization in cross-linguistic emotion recognition tasks.

2. Related Work

2.1. Cross-Linguistic Speech Emotion Recognition and Robust Feature Learning

2.2. Advanced and Adaptive Multi-feature Fusion Strategies

3. Method

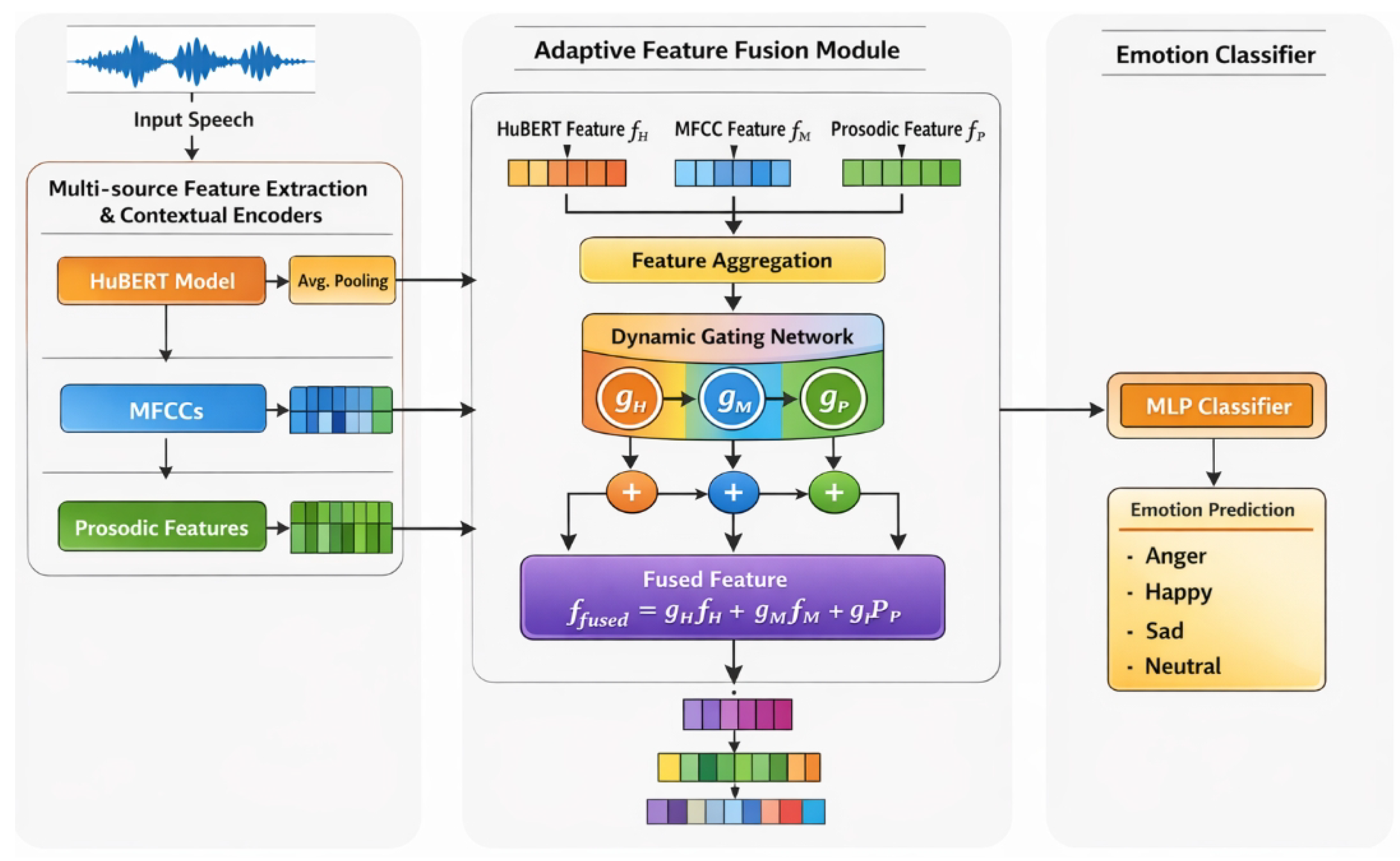

3.1. Overall Architecture of ACMF-Net

3.2. Multi-source Feature Extraction and Contextual Encoders

3.2.1. HuBERT Self-supervised Speech Representation

3.2.2. Mel-frequency Cepstral Coefficient (MFCC) Contextual Encoder

3.2.3. Prosodic Features Contextual Encoder

3.3. Adaptive Feature Fusion Module

3.3.1. Dynamic Gating Mechanism

3.4. Emotion Classifier

4. Experiments

4.1. Experimental Setup

4.1.1. Datasets

4.1.2. Feature Extraction

- Mel-frequency Cepstral Coefficients (MFCCs): A standard set of 39 MFCCs (including and ) are extracted with a window size of 25 ms and a hop size of 10 ms.

- Linear Prediction Cepstral Coefficients (LPCCs): Similar to MFCCs, a 39-dimensional LPCC feature set is also extracted.

- Spectrograms: Log-Mel spectrograms are computed to capture time-frequency representations.

- Prosodic Features: A rich set of prosodic features is extracted, including fundamental frequency (F0) contours, energy, speaking rate, and speech duration. Statistical functionals (mean, standard deviation, quartiles, range) are computed over segment-level features to capture overall prosodic characteristics.

- HuBERT Embeddings: We leverage a pre-trained large-scale HuBERT model [15] to extract deep contextualized speech representations. Specifically, the hidden states from the 12th transformer layer are used, which have been shown to capture both acoustic and semantic information relevant for various speech tasks.

4.1.3. Training Strategy

4.1.4. Evaluation Metrics

4.2. Performance on Source Language Dataset

4.3. Ablation Study

- Impact of Dynamic Gating: Removing the Dynamic Gating mechanism and replacing it with a fixed concatenation strategy leads to a significant performance drop of 2.74% UAR (from 76.92% to 74.18

- Impact of Contextual MFCC Encoder: Replacing the lightweight Transformer encoder for MFCCs with a simple global average pooling mechanism results in a decrease of 1.27% UAR (from 76.92% to 75.65%). This demonstrates that capturing local temporal dependencies and contextual information within MFCC sequences, rather than just raw spectral content, is vital for enhanced emotional discriminative power.

- Impact of Contextual Prosodic Encoder: Similarly, substituting the dedicated Transformer encoder for prosodic features with conventional statistical aggregation (e.g., mean, std-dev) leads to a performance reduction of 1.71% UAR (from 76.92% to 75.21%). This confirms that modeling the long-term dependencies and dynamic patterns of prosody more effectively through a Transformer encoder is superior to static statistical summaries.

- Combined Impact of Contextual Encoders: When both MFCC and prosodic contextual encoders are replaced by simpler pooling/statistical methods, the performance further degrades to 73.80% UAR. This cumulative drop highlights the synergistic effect of contextualizing each feature modality before fusion.

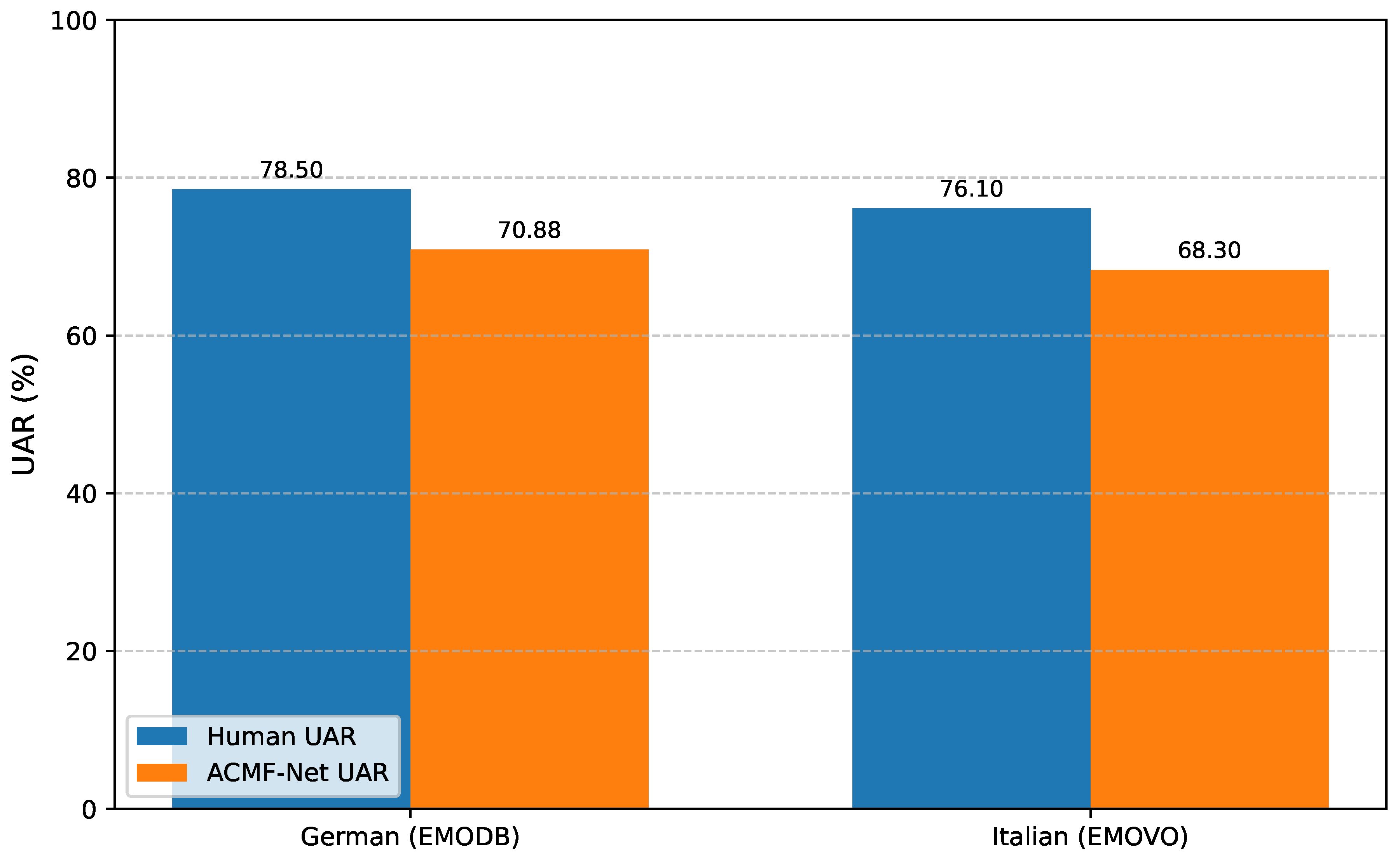

4.4. Cross-Linguistic Performance and Human Evaluation

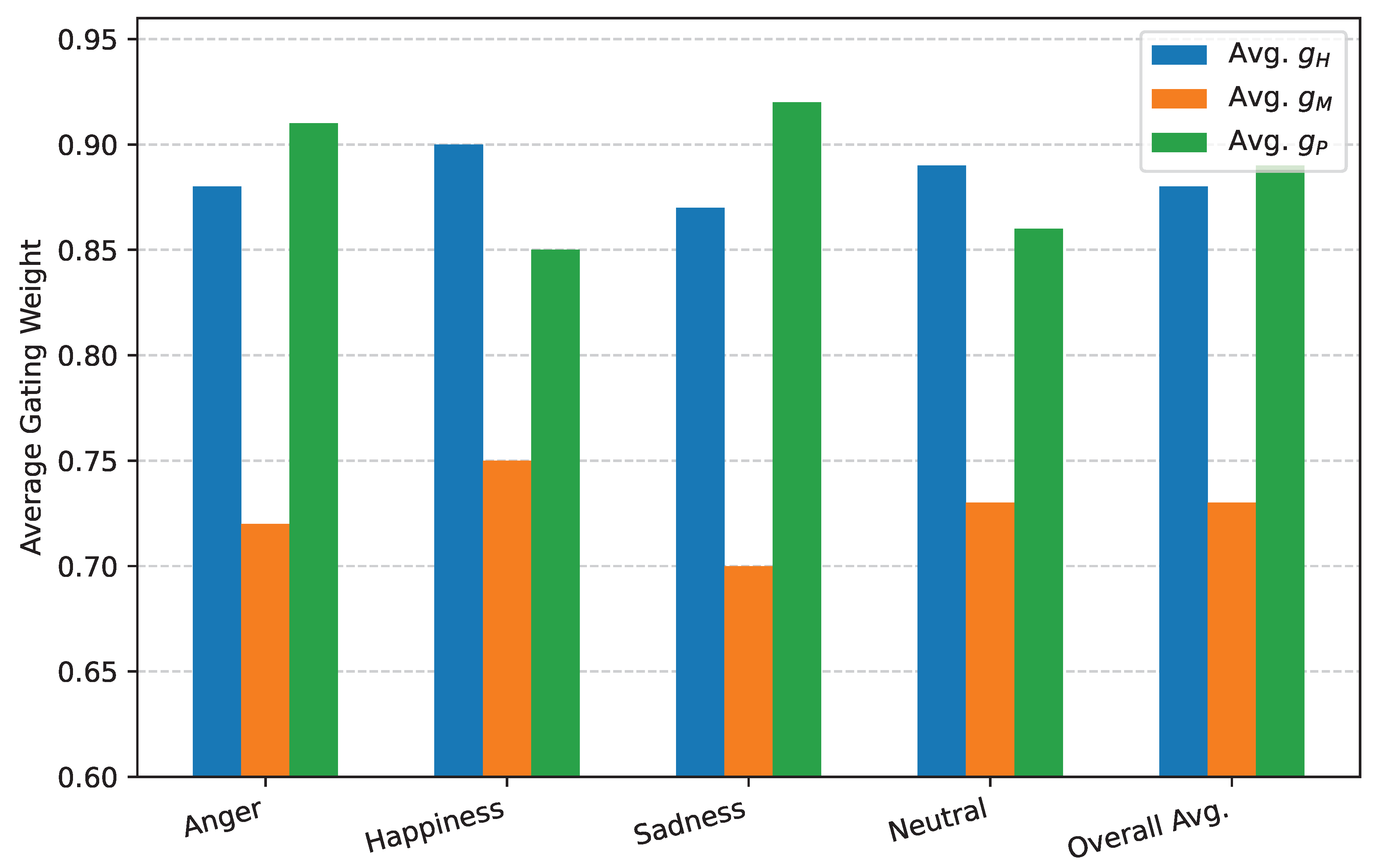

4.5. Analysis of Dynamic Gating Weights

4.6. Per-Class Performance Analysis

5. Conclusions

References

- Sun, Y.; Yu, N.; Fu, G. A Discourse-Aware Graph Neural Network for Emotion Recognition in Multi-Party Conversation. In Proceedings of the Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: EMNLP 2021; Association for Computational Linguistics, 2021; pp. 2949–2958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turcan, E.; Muresan, S.; McKeown, K. Emotion-Infused Models for Explainable Psychological Stress Detection. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2021 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, 2021; Association for Computational Linguistics; pp. 2895–2909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Z.; Ramesh, A.; Ruan, J.; Hao, P.; Al Jallad, N.; Jang, H.; Ly-Mapes, O.; Fiscella, K.; Xiao, J.; Luo, J. Use of artificial intelligence to detect dental caries on intraoral photos. Quintessence International 2025, 56. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, Z.; Lin, Z.; Zhao, D.; Zhao, W.; Flynn, D.; Ansari, S.; Wei, C. Evaluating scenario-based decision-making for interactive autonomous driving using rational criteria: A survey. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2501.01886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, L.; Tian, Z.; He, Y.; Liu, S.; Chen, H.; Yuan, F.; Peng, Y. Enhanced mean field game for interactive decision-making with varied stylish multi-vehicles. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2509.00981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z.; Tian, Z.; Lan, J.; Zhao, D.; Wei, C. Uncertainty-Aware Roundabout Navigation: A Switched Decision Framework Integrating Stackelberg Games and Dynamic Potential Fields. IEEE Transactions on Vehicular Technology 2025, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, L.; et al. Real-time Threat Identification Systems for Financial API Attacks under Federated Learning Framework. Academic Journal of Business & Management 2025, 7, 65–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Li, X.; Wang, Q.; Shen, J. Visual In-Context Learning for Large Vision-Language Models. Proceedings of the Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics, ACL 2024, Bangkok, Thailand and virtual meeting 2024, 2024, 15890–15902. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, F.; Li, H.; Qian, S.; Wang, X.; Lian, Z.; Wu, H.; Zhu, Z.; Gao, Y.; Li, Q.; Zheng, Y.; et al. Rethinking Facial Expression Recognition in the Era of Multimodal Large Language Models: Benchmark, Datasets, and Beyond. arXiv arXiv:2511.00389. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Song, L.; Shen, J. MAM: Modular Multi-Agent Framework for Multi-Modal Medical Diagnosis via Role-Specialized Collaboration. In Proceedings of the Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: ACL 2025, Vienna, Austria, 2025; pp. 25319–25333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Z.; Hua, H.; Luo, J. MIRA: Multimodal Iterative Reasoning Agent for Image Editing. arXiv arXiv:2511.21087. [CrossRef]

- Huang, S. Measuring Supply Chain Resilience with Foundation Time-Series Models. European Journal of Engineering and Technologies 2025, 1, 49–56. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, S. LSTM-Based Deep Learning Models for Long-Term Inventory Forecasting in Retail Operations. Journal of Computer Technology and Applied Mathematics 2025, 2, 21–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csordás, R.; Irie, K.; Schmidhuber, J. The Devil is in the Detail: Simple Tricks Improve Systematic Generalization of Transformers. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2021 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, 2021; Association for Computational Linguistics; pp. 619–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, W.; Bolte, B.; Tsai, Y.H.; Lakhotia, K.; Salakhutdinov, R.; Mohamed, A. HuBERT: Self-Supervised Speech Representation Learning by Masked Prediction of Hidden Units. IEEE ACM Trans. Audio Speech Lang. Process. 2021, 3451–3460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Long, G. Multimodal Event Transformer for Image-guided Story Ending Generation. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 17th Conference of the European Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics, 2023; pp. 3434–3444. [Google Scholar]

- Hua, H.; Zeng, Z.; Song, Y.; Tang, Y.; He, L.; Aliaga, D.; Xiong, W.; Luo, J. MMIG-Bench: Towards Comprehensive and Explainable Evaluation of Multi-Modal Image Generation Models. arXiv arXiv:2505.19415.

- Joshi, A.; Bhat, A.; Jain, A.; Singh, A.; Modi, A. COGMEN: COntextualized GNN based Multimodal Emotion recognitioN. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2022 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, 2022; Association for Computational Linguistics; pp. 4148–4164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagarajan, B.; Oruganti, V.R.M. Deep Learning as Feature Encoding for Emotion Recognition. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1810.12613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, N.T.; Dang, D.N.M.; Nguyen, S.D. Hybrid Data Augmentation and Deep Attention-based Dilated Convolutional-Recurrent Neural Networks for Speech Emotion Recognition. CoRR 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Li, S.; Zhang, X.; Zhan, J.; Wang, P.; Zhou, Y.; Qiu, X. SpeechGPT: Empowering Large Language Models with Intrinsic Cross-Modal Conversational Abilities. In Proceedings of the Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: EMNLP 2023, 2023; Association for Computational Linguistics; pp. 15757–15773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Wang, C.; Tang, Y.; Tran, C.; Tang, Y.; Pino, J.; Baevski, A.; Conneau, A.; Auli, M. Multilingual Speech Translation from Efficient Finetuning of Pretrained Models. Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 59th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics and the 11th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing 2021, Volume 1, 827–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Pergola, G.; Gui, L.; Zhou, D.; He, Y. Topic-Driven and Knowledge-Aware Transformer for Dialogue Emotion Detection. Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 59th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics and the 11th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing 2021, Volume 1, 1571–1582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Lee, W. CoMPM: Context Modeling with Speaker’s Pre-trained Memory Tracking for Emotion Recognition in Conversation. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2022 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, 2022; Association for Computational Linguistics; pp. 5669–5679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ao, J.; Wang, R.; Zhou, L.; Wang, C.; Ren, S.; Wu, Y.; Liu, S.; Ko, T.; Li, Q.; Zhang, Y.; et al. SpeechT5: Unified-Modal Encoder-Decoder Pre-Training for Spoken Language Processing. Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 60th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics 2022, Volume 1, 5723–5738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ElSherief, M.; Ziems, C.; Muchlinski, D.; Anupindi, V.; Seybolt, J.; De Choudhury, M.; Yang, D. Latent Hatred: A Benchmark for Understanding Implicit Hate Speech. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2021 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, 2021; Association for Computational Linguistics; pp. 345–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Tang, F.; Zhao, M.; Zhu, Y. EmoCaps: Emotion Capsule based Model for Conversational Emotion Recognition. In Proceedings of the Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: ACL 2022; Association for Computational Linguistics, 2022; pp. 1610–1618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Cheng, Z.Q.; Zhao, J.; Peng, X.; Li, X. LEAF: unveiling two sides of the same coin in semi-supervised facial expression recognition. Computer Vision and Image Understanding 2025, 104451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.; Huang, L.; Xue, H.; Hu, S. Supervised Prototypical Contrastive Learning for Emotion Recognition in Conversation. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2022 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, 2022; Association for Computational Linguistics; pp. 5197–5206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Yu, Y.; Niu, D.; Guo, W.; Xu, Y. ConFEDE: Contrastive Feature Decomposition for Multimodal Sentiment Analysis. Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 61st Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics 2023, Volume 1, 7617–7630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Zhan, P.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, L.; Xu, Z. Multimodal Fusion with Co-Attention Networks for Fake News Detection. In Proceedings of the Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: ACL-IJCNLP 2021, 2021; Association for Computational Linguistics; pp. 2560–2569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Wang, Y.; Yin, G.; Liu, K.; Liu, Y.; Yu, T. Learning Language-guided Adaptive Hyper-modality Representation for Multimodal Sentiment Analysis. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2023 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, 2023; Association for Computational Linguistics; pp. 756–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Xu, B.; Zhu, C.; Zhao, T. CLMLF:A Contrastive Learning and Multi-Layer Fusion Method for Multimodal Sentiment Detection. In Proceedings of the Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: NAACL 2022, 2022; Association for Computational Linguistics; pp. 2282–2294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, W.; Cahyawijaya, S.; Liu, Z.; Fung, P. Multimodal End-to-End Sparse Model for Emotion Recognition. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2021 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, 2021; Association for Computational Linguistics; pp. 5305–5316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Mao, S.; Li, Q.; Peng, X. 3d landmark detection on human point clouds: A benchmark and a dual cascade point transformer framework. Expert Systems with Applications 2026, 301, 130425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Bao, H.; Huang, S.; Dong, L.; Wei, F. MiniLMv2: Multi-Head Self-Attention Relation Distillation for Compressing Pretrained Transformers. In Proceedings of the Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: ACL-IJCNLP 2021, 2021; Association for Computational Linguistics; pp. 2140–2151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.; Li, K.; Jin, X.; Cichocki, A.; Zhao, Q.; Kong, W. CTFN: Hierarchical Learning for Multimodal Sentiment Analysis Using Coupled-Translation Fusion Network. Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 59th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics and the 11th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing 2021, Volume 1, 5301–5311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, F.; Zhang, L.; Yin, S.; Zhao, X.; Liu, S.; Li, B.; Liu, Y. A Novel Global Feature-Oriented Relational Triple Extraction Model based on Table Filling. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2021 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, 2021; Association for Computational Linguistics; pp. 2646–2656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, J.; Zhang, G.; Chen, Z.; Yu, N. Multi-homed abnormal behavior detection algorithm based on fuzzy particle swarm cluster in user and entity behavior analytics. Scientific Reports 2022, 12, 22349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, J.; Chen, Z.; Tian, L.; Zhang, G. Overview of user and entity behavior analytics technology based on machine learning. Computer Engineering 2022, 48, 10–24. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, J.; Hu, F.; Berkeley, G.; Lyu, W.; Shen, X. Visual Gait Alignment for Sensorless Prostheses: Toward an Interpretable Digital Twin Framework. Proceedings of the Proceedings of the AAAI Symposium Series 2025, Vol. 7, 488–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Method | Validation UAR (%) | Test UAR (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Baseline (Prosody + LPCC) | 76.01 | 72.45 |

| HuBERT Only | 77.05 | 74.82 |

| HuMP-CAT (Multi-feature Fusion) | 78.50 | 75.80 |

| ACMF-Net (Ours) | 79.85 | 76.92 |

| Model Configuration | Test UAR (%) |

|---|---|

| ACMF-Net (Full Model) | 76.92 |

| w/o Dynamic Gating (Fixed Concatenation) | 74.18 |

| w/o MFCC Contextual Encoder (Global Average Pooling) | 75.65 |

| w/o Prosodic Contextual Encoder (Statistical Aggregation) | 75.21 |

| w/o Contextual Encoders (Global Avg. Pooling for both) | 73.80 |

| Target Language | HuBERT Only | HuMP-CAT | ACMF-Net (Ours) |

|---|---|---|---|

| German (EMODB) | 68.21 | 69.55 | 70.88 |

| Italian (EMOVO) | 65.90 | 67.12 | 68.30 |

| French | 63.45 | 64.98 | 66.15 |

| Spanish | 67.03 | 68.30 | 69.42 |

| Mandarin | 64.18 | 65.50 | 66.71 |

| Arabic | 62.80 | 64.05 | 65.23 |

| Hindi | 61.15 | 62.48 | 63.60 |

| Average UAR | 64.67 | 65.99 | 67.18 |

| Target Language | Avg. | Avg. | Avg. |

|---|---|---|---|

| German (EMODB) | 0.87 | 0.70 | 0.90 |

| Italian (EMOVO) | 0.89 | 0.74 | 0.86 |

| Mandarin | 0.90 | 0.71 | 0.87 |

| Arabic | 0.88 | 0.69 | 0.89 |

| Emotion Class | Accuracy (%) |

|---|---|

| Anger | 79.15 |

| Happiness (Excitement) | 77.80 |

| Sadness | 80.55 |

| Neutral | 70.18 |

| Overall UAR | 76.92 |

| Emotion Class | Accuracy (%) |

|---|---|

| Anger | 75.20 |

| Boredom | 65.50 |

| Disgust | 60.15 |

| Fear | 68.90 |

| Happiness | 72.85 |

| Sadness | 77.65 |

| Neutral | 70.50 |

| Overall UAR | 70.88 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).