1. Introduction

Sulforaphane (SFN) is an aliphatic isothiocyanate derived from glucoraphanin, a major glucosinolate abundant in cruciferous vegetables such as broccoli, kale, and cauliflower. It is widely recognized as a bioactive dietary phytochemical with diverse biological activities [

1]. SFN exerts pleiotropic cytoprotective, anti-inflammatory, and stress-adaptive effects by regulating redox homeostasis, mitochondrial function, immune responses, and cellular detoxification pathways, that are central to cellular stress control [

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7].

At a fundamental biological level, many of these effects are mediated by the activation of the nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2)–antioxidant response element (ARE) pathway, that enhances cellular antioxidant capacity and detoxification systems, and by the modulation of inflammatory and metabolic signaling networks [

8]. Consistent with these properties, SFN has been implicated in the protection against cardiovascular, metabolic, and neurodegenerative disorders, underscoring its role as a systemic regulator of cellular stress responses and homeostasis [

9,

10,

11,

12,

13].

Given that dysregulated redox balance, chronic inflammation, metabolic reprogramming, and impaired stress adaptation are the central hallmarks of carcinogenesis, these broad biological properties provide a strong mechanistic rationale for the relevance of SFN in cancer prevention and therapy [

14]. Consistent with this concept, recent epidemiological analyses have linked the sustained consumption of cruciferous vegetables to a reduced risk of multiple malignancies, including lung, colorectal, prostate, and breast cancers, underscoring the translational potential of SFN in oncology [

15,

16,

17,

18]. These observations prompted extensive mechanistic investigations to elucidate how SFN interferes with cancer initiation and progression at the molecular level [

14]. Importantly, the biological activities of SFN appear to be particularly relevant to cancer prevention and early interception, and its role in established malignancies is increasingly being explored in supportive or adjunctive therapeutic contexts rather than as a standalone anticancer agent [

19]. Accordingly, the translational potential of SFN is best viewed within prevention-oriented and mechanism-guided intervention frameworks rather than as a conventional cytotoxic anticancer agent.

In cancer-specific contexts, SFN exhibits multifaceted anticancer effects [

20]. It robustly activates the Nrf2–ARE pathway, thereby upregulating detoxification and antioxidant enzymes and enhancing cellular defense against carcinogenic insults [

21]. SFN also modulates epigenetic regulators, such as histone deacetylases (HDACs) and DNA methyltransferases, leading to the reprogramming of aberrant chromatin states in cancer cells [

22]. Additionally, SFN triggers multiple programmed cell death pathways including apoptosis, autophagy, and ferroptosis [

23,

24,

25]. SFN further suppresses oncogenic signaling and tumor-promoting stress responses, thereby reinforcing its broad anticancer effects [

26,

27]. Notably, the magnitude and nature of these molecular responses to SFN are increasingly recognized to vary according to genetic background, gut microbiome composition, and patterns of dietary exposure, highlighting the importance of inter-individual heterogeneity in shaping SFN bioactivity and translational outcomes [

19].

Consistent with these molecular actions, preclinical studies across diverse cancer models have demonstrated that SFN inhibits cell proliferation, reduces tumor growth, impairs metastatic potential, and suppresses associated phenotypes [

28,

29]. Moreover, translational and early phase clinical investigations have begun to confirm that SFN administered via broccoli-derived preparations or stabilized formulations is well-tolerated in short-term clinical settings [

30]. SFN metabolites are detectable in biological fluids and tissues. They activate cytoprotective gene expression programs and facilitate the detoxification of environmental carcinogens, thereby providing a mechanistic basis for chemopreventive and supportive clinical applications [

31,

32].

However, significant challenges remain before SFN can be widely used in clinical oncology. The bioavailability of active SFN remains highly variable and is influenced by factors such as the food matrix, myrosinase activity, individual microbiome composition, and formulation stability [

33,

34,

35,

36]. Additionally, optimal dosing regimens, long-term safety data, and standardized endpoints for cancer prevention and therapy are lacking [

19,

37]. These limitations hinder consistent translation from the bench to bedside [

38,

39,

40].

Therefore, this review aimed to comprehensively integrate and critically evaluate the current evidence on SFN, from epidemiological associations, biochemical and metabolic pathways, and molecular mechanisms to preclinical data and emerging clinical findings, and to discuss the major translational challenges and future directions for harnessing SFN as a credible, evidence-based agent for cancer prevention and therapy.

A focused literature search was performed utilizing PubMed, Google Scholar, and ClinicalTrials.gov using the keyword “sulforaphane.” Only peer-reviewed, English-language, full-text articles published until December 2025 were included.

2. Chemistry, Metabolism, and Bioavailability

SFN is a low-molecular-weight aliphatic isothiocyanate generated from the glucosinolate precursor glucoraphanin, which is abundant in broccoli, Brussels sprouts, kale, and other cruciferous vegetables [

41]. Glucoraphanin is relatively inert and water soluble, whereas SFN is a highly reactive electrophile capable of covalently modifying protein thiols, a property that underlies its biological activity [

33,

42].

2.1. Glucoraphanin-to-Sulforaphane Conversion

In intact plant tissues, glucoraphanin and β-thioglucosidase myrosinase are spatially compartmentalized. However, tissue damage caused by cutting, chewing, or insect attack brings them into contact, leading to the rapid hydrolysis of glucoraphanin and the formation of SFN as the major isothiocyanate product [

33,

43]. The balance between SFN and alternative hydrolysis products, such as sulforaphane nitrile, is influenced by factors such as pH, the presence of epithiospecifier proteins, and metal ions [

44]. Cooking markedly affects this bioconversion, as plant myrosinase is heat-labile and is largely inactivated by prolonged boiling or microwaving, whereas brief steaming preserves substantial enzyme activity [

45]. When plant myrosinase is inactivated, the conversion of glucoraphanin to SFN depends predominantly on the metabolic capacity of the gut microbiota, which possesses myrosinase-like activities capable of generating SFN and related metabolites in the colon [

46].

2.2. Human Metabolism and the Mercapturic Acid Pathway

Once absorbed from the small intestine, SFN is predominantly metabolized via the mercapturic acid pathway, beginning with its rapid conjugation to glutathione (GSH), which is catalyzed by glutathione

S-transferases to form the SFN–GSH conjugate [

47]. SFN–GSH is subsequently processed by γ-glutamyltransferase, dipeptidases, and

N-acetyltransferases to yield sequential cysteinyl-glycine (SFN–CysGly), cysteine (SFN–Cys), and

N-acetylcysteine (SFN–NAC) conjugates, which represent the classical mercapturic acid pathway metabolites of SFN [

48].

In human feeding studies with broccoli sprout preparations, these SFN conjugates are readily detected in plasma and urine and typically account for the majority of the administered dose, with reports of 60–80% recovery of SFN equivalents in urine within 24 h after ingestion [

46]. As these mercapturic acid pathway metabolites represent the dominant in vivo forms of SFN, they serve as robust biomarkers for SFN exposure and pharmacokinetic behavior in clinical and nutritional intervention studies [

47,

49].

2.3. Determinants of Sulforaphane Bioavailability in Humans

The human bioavailability of SFN is influenced by multiple interacting dietary and host factors. First, the presence of active myrosinase in the ingested food matrix is a critical determinant of SFN bioavailability. Fresh broccoli sprouts or microgreens, which retain endogenous myrosinase due to minimal processing, yield substantially higher systemic exposure to SFN than myrosinase-inactive supplements or boiled broccoli, even at comparable glucoraphanin doses [

33]. Second, the formulation strongly influenced SFN kinetics. Soups, beverages, and combined glucoraphanin–myrosinase preparations can enhance absorption and shift the time to peak concentration compared to capsule-based supplements [

50]. Third, inter-individual variability in gut microbiota composition contributes to the wide differences in glucoraphanin-to-SFN conversion efficiency between subjects, particularly when plant myrosinase is absent or inactivated [

46]. Genetic polymorphisms in enzymes, such as glutathione

S-transferases, may further modulate SFN conjugation and excretion, although their effect appears modest compared to diet and microbiome-related factors in most studies [

51]. Collectively, these determinants explained the substantial variability in systemic SFN exposure among individuals receiving comparable doses of glucoraphanin. An integrated overview of SFN generation, absorption, metabolism, and systemic bioavailability, as well as the major factors contributing to interindividual variability, is schematically illustrated in

Figure 1.

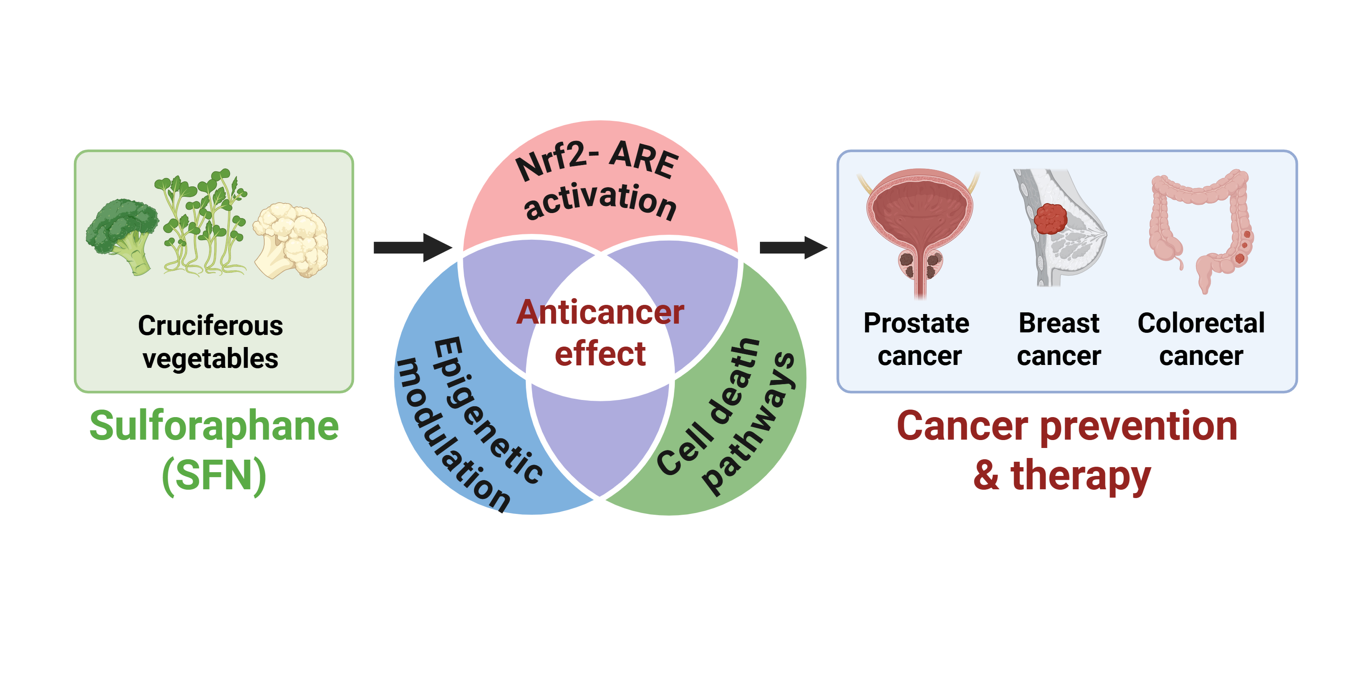

3. Molecular Mechanisms of SFN

SFN exerts anticancer effects through multiple molecular mechanisms, including the activation of the Nrf2–ARE antioxidant pathway, epigenetic regulation, and modulation of programmed cell death and oncogenic signaling. An integrated schematic summarizing these multilayered mechanisms is presented in

Figure 2.

3.1. Nrf2–ARE Activation

Nrf2 is the master transcriptional regulator of cellular antioxidant defense, and SFN robustly activates this pathway by disrupting the negative regulator Kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1 (Keap1). SFN treatment in vitro and in vivo leads to the nuclear translocation of Nrf2 and upregulation of downstream cytoprotective genes, including those encoding detoxification enzymes and antioxidant proteins, such as heme oxygenase 1 (HO-1), NAD(P)H quinone dehydrogenase 1 (NQO1), and glutathione-related enzymes [

52]. Activation of the Nrf2–ARE pathway by SFN has been demonstrated to ameliorates oxidative and electrophilic stress in disparate tissues, thereby reducing cellular damage and suppressing processes that can initiate carcinogenesis or promote tumor progression [

53]. In addition to its canonical antioxidant role, Nrf2 activation by SFN contributes to metabolic reprogramming, that enhances cellular resilience under carcinogen-induced stress [

20]. SFN-induced Nrf2 signaling upregulates enzymes involved in glutathione synthesis and nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) regeneration, thereby strengthening redox homeostasis and improving the detoxification capacity of premalignant and malignant cells [

54]. Additionally, recent studies demonstrate that SFN-mediated Nrf2 activation modulates inflammatory signaling by suppressing nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-κB)-driven transcription, thereby reducing the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines implicated in tumor initiation and progression [

55]. Although Nrf2 activation can exhibit context-dependent effects in established tumors, preclinical evidence consistently indicates that SFN-driven Nrf2 signaling supports chemopreventive activity by maintaining genomic stability and mitigating oxidative damage during early carcinogenesis [

56]. Importantly, accumulating evidence indicates that the biological consequences of Nrf2 activation are highly dependent on its magnitude, duration, and cellular context. Transient, diet-derived activation by SFN predominantly confers cytoprotective and chemopreventive effects, in contrast to the sustained oncogene-driven Nrf2 hyperactivation observed in certain advanced malignancies [

20,

56].

3.2. Epigenetic Modulation

SFN is a well-characterized dietary HDAC inhibitor, and multiple studies have demonstrated that SFN decreases HDAC activity and increases histone H3/H4 acetylation in cancer cells [

57]. SFN-mediated HDAC inhibition leads to chromatin relaxation and reactivation of tumor-suppressive genes, such as p21 and BAX, promoting cell cycle arrest and apoptosis in colorectal and prostate cancer models [

58]. In addition to histone acetylation, SFN influences DNA methylation. In prostate cancer transgenic adenocarcinoma of mouse prostate (TRAMP) C1 cells, SFN demethylates CpG sites within the Nrf2 promoter and reduces DNA methyltransferase (DNMT)1 binding, resulting in the restoration of Nrf2 transcriptional activity [

59]. SFN-induced inhibition of DNMT has also been reported in colon epithelial cells, where promoter demethylation of cytoprotective genes enhances antioxidant and detoxification capacities [

60]. Collectively, these findings indicate that SFN targets multiple epigenetic layers, including HDACs, DNMTs, and chromatin architecture, to reverse cancer-associated epigenetic abnormalities and shift transcriptional programs toward a tumor-suppressive phenotype [

61].

3.3. Cell Death and Anticancer Signaling

SFN has been demonstrated to induce intrinsic apoptosis in multiple tumor types. In oral squamous cell carcinoma, SFN induces mitochondrial cytochrome

c release, activates caspase-9 and caspase-3, and increases p53 expression, culminating in robust and dose-dependent apoptotic cell death [

62]. Consistent with these observations, SFN promoted apoptotic cell death in pancreatic cancer models, where it suppressed proliferation and metastasis and induced G2/M cell cycle arrest in PANC-1 pancreatic carcinoma cells, further supporting its role as an apoptosis-modulating agent in gastrointestinal malignancies [

63].

In addition to apoptosis, SFN modulates autophagy in a context-dependent manner. In esophageal squamous cell carcinoma cells, SFN induces protective autophagy via reactive oxygen species (ROS)-dependent AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK)/mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) signaling, and pharmacological inhibition of autophagy enhances SFN-induced apoptosis, suggesting that autophagy may partially attenuate SFN cytotoxicity under these conditions

[64]. In contrast, in non-small cell lung cancer, SFN suppresses autophagy by downregulating fatty acid synthase and perturbing tumor lipid metabolism, thereby enhancing susceptibility to apoptosis and limiting malignant progression [

65]. Collectively, these findings indicate that the effect of SFN on autophagy reflects a context-dependent balance between cytoprotective and pro-death signaling pathways in various tumor types.

Accumulating evidence indicates that SFN participates in non-apoptotic cell death pathways, particularly in ferroptosis. In acute myeloid leukemia cells, SFN induces lipid peroxidation, iron accumulation, and glutathione peroxidase 4 (GPX4) suppression in a dose-dependent manner, resulting in the concurrent activation of apoptotic and ferroptotic cell death programs [

25]. SFN also induces ferroptosis in small cell lung cancer and promotes sirtuin-3–dependent ferroptosis in colorectal cancer through AMPK-mediated metabolic signaling, underscoring its potential to target therapy-resistant tumor subpopulations [

66,

67].

At the signaling level, SFN inhibits multiple oncogenic and prosurvival pathways, including NF-κB, signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3), phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K)/ protein kinase B (AKT), mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK), and noncoding RNA regulatory circuits, collectively suppressing proliferation, inflammation, invasion, and metastasis [

38,

68]. For example, SFN downregulates the STAT3– creatine kinase, mitochondrial 2 antisense RNA 1 (CKMT2-AS1) oncogenic axis, thereby reducing STAT3-associated transcriptional activity and limiting cancer cell proliferation [

69]. SFN also disrupts PI3K/AKT signaling in multiple tumor models, decreasing downstream anti-apoptotic signaling and rendering cancer cells more susceptible to programmed cell death [

70]. Moreover, SFN attenuates interleukin-1 beta (IL-1β)–induced interleukin-6 (IL-6) expression in colorectal cancer cells by reducing ROS production and disrupting MAPK/activator protein-1 (AP-1) signaling, highlighting its capacity to concurrently modulate inflammatory and survival pathways relevant to tumor promotion [

71].

4. Preclinical & Clinical Evidence

4.1. Preclinical Summary

In the SFN oncology literature, prostate, breast, colorectal, and lung cancers have been among the most frequently investigated indications in preclinical studies. Therefore,

Table 1 was organized to reflect the relative breadth of the available evidence and improve readability.

4.1.1. Prostate Cancer

In androgen-responsive prostate cancer models, including LNCaP (lymph node carcinoma of the prostate) and 22Rv1 cells, SFN suppresses key lipogenic regulators, such as acetyl-CoA carboxylase 1 (ACC1), fatty acid synthase (FASN), carnitine palmitoyltransferase 1A (CPT1A), and sterol regulatory element-binding protein 1 (SREBP1), supporting a mechanism centered on the inhibition of fatty acid synthesis and metabolic reprogramming. Consistent with these in vitro findings, SFN administration in the TRAMP model led to a marked reduction in lipid-related metabolites (such as total free fatty acids and phospholipids) and energy-associated intermediates (e.g., acetyl-CoA and ATP), concomitantly activating Nrf2–associated cytoprotective signaling, indicating a coordinated metabolic and stress response axis in vivo [

72]. Beyond metabolic regulation, SFN also targets prostate cancer stem-like properties by decreasing tumorsphere formation and downregulating stemness-associated markers, including cluster of differentiation 44 (CD44) and aldehyde dehydrogenase 1 (ALDH1), accompanied by suppression of Wnt/β-catenin and hedgehog signaling and induction of pro-apoptotic effects [

73].

4.1.2. Breast Cancer

In triple-negative breast cancer cells (MDA-MB-231), SFN attenuates metastatic potential by targeting the rapidly accelerated fibrosarcoma (RAF)/mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase (MEK)/extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) signaling cascade, as evidenced by the reduced expression of RAF family proteins and decreased activation of downstream MEK and ERK [

28]. In addition to suppressing invasion-associated signaling, SFN inhibits breast cancer cell proliferation in both MDA-MB-231 and ZR-75-1 estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer cells by inducing mitotic delay, accompanied by modulation of key cell-cycle regulators, including cyclin B1, cell division cycle 2 (CDC2), and cell division cycle 25C (CDC25C), and activation of cyclin-dependent kinase 5 regulatory subunit 1 (CDK5R1)/cyclin-dependent kinase 5 (CDK5)-associated signaling, ultimately resulting in G2/M arrest and apoptosis [

74]. Beyond proliferative and migratory control, SFN also targets breast cancer stem-like phenotypes by reducing mammosphere formation and cancer stem cell (CSC)-enriched populations in vitro and by suppressing tumor growth in xenograft models, concomitant with the downregulation of Cripto-1 (teratocarcinoma-derived growth factor 1, TDGF1)-related stemness markers, suggesting that SFN may limit tumor growth as well as recurrence- and resistance-associated subpopulations in breast cancer [

75].

4.1.3. Colorectal Cancer

In HCT116 colorectal cancer cells, SFN promotes ferroptosis-associated features, including suppression of solute carrier family 7 member 11 (SLC7A11), increased ROS production, enhanced lipid peroxidation, and altered intracellular ferrous iron (Fe ⁺) levels, that are mechanistically linked to the activation of sirtuin 3 (SIRT3)–AMPK–mTOR signaling axis [

67]. Beyond the direct regulation of ferroptotic cell death, SFN also modulates inflammatory signaling in HT-29 cells by suppressing IL-1β–induced IL-6 transcription and secretion through the attenuation of ROS accumulation and inhibition of p38 MAPK–AP-1 and STAT3 activation, accompanied by reduced invasion and migration phenotypes [

71]. In addition to cell death induction and inflammatory control, SFN inhibits proliferation and motility in HT-29 and SW480 colorectal cancer models while engaging an extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK)–Nrf2–UDP-glucuronosyltransferase family 1 member A (UGT1A)–dependent metabolic detoxification axis, together with cell-cycle arrest and apoptosis-associated signatures, supporting a multi-layered mechanism that integrates signaling suppression with enhanced detoxification capacity [

76].

4.2. Clinical Studies

As of December, 2025, a search of the ClinicalTrials.gov registry using the keyword “sulforaphane” identified approximately 80–90 registered clinical studies, of which approximately 20 trials were related to cancer prevention or therapeutic intervention. These cancer-focused studies primarily evaluated SFN- or SFN-rich preparations in prostate, breast, lung, and colorectal cancer settings, as well as in cancer risk- or biomarker-based intervention trials. Among these registered studies, clinical trials with available outcome data or reported results are selectively summarized in

Table 2 to highlight the current state of clinical evidence supporting the anticancer potential of SFN.

Clinical evidence for the anti-cancer effects of SFN has primarily been derived from prostate cancer–related clinical studies. Early phase clinical trials employing SFN or SFN-rich broccoli sprout preparations have demonstrated favorable modulation of prostate cancer–associated biomarkers, including a reduction in prostate-specific antigen (PSA) levels in a subset of patients and increased urinary excretion of SFN metabolites, supporting systemic bioavailability and target engagement [

80,

81,

82,

83]. Additionally, pre-surgical or biopsy window studies have further confirmed that oral administration of SFN-rich preparations lead to a measurable accumulation of SFN metabolites in prostate tissue, indicating effective tissue penetration in humans [

82,

83].

In breast cancer-related clinical studies, SFN has been primarily evaluated using presurgical window-of-opportunity designs. These trials demonstrated that short-term administration of SFN-rich broccoli sprout preparations resulted in decreased HDAC activity and modulation of cancer-associated biomarkers in breast tissue, supporting the epigenetic activity of SFN in a clinical context [

84,

85,

86,

87]. Although these studies were not designed to evaluate long-term clinical outcomes, they provide supportive mechanistic evidence that SFN exposure is associated with the modulation of cancer-related molecular endpoints in human breast tumors.

Clinical investigations of lung cancer risk have largely focused on cancer risk reduction and biomarker modulation, rather than direct therapeutic efficacy. In individuals at an elevated risk of lung cancer, including former smokers, SFN-rich interventions were evaluated primarily through histopathological and proliferation-related biomarkers, including changes in the bronchial dysplasia index and modulation of the cell proliferation marker Ki-67 in the bronchial epithelium, with modest biomarker modulation but without definitive between-group efficacy signals [

88]. These findings support the potential role of SFN in modulating biological processes associated with early carcinogenesis rather than promoting the regression of established tumors.

Collectively, the available clinical studies suggest that SFN is well tolerated in humans and can modulate cancer-related biomarkers in multiple organ sites. However, current clinical evidence is largely derived from small-scale, short-term studies relying on surrogate endpoints, highlighting the need for larger, well-designed trials to establish the preventive or therapeutic efficacy of SFN in oncology.

5. Application & Future Perspectives

5.1. Formulation Standardization and Bioavailability

Future clinical applications of SFN are limited by substantial inter-individual variability in systemic exposure, even when similar doses are administered [

39,

50,

89]. This variability arises from multiple factors, including differences in glucoraphanin content, myrosinase activity, food processing conditions, and gut microbiota composition, which together represent a major translational barrier [

33,

89,

90]. As inconsistent SFN generation and stability directly compromise reproducibility across clinical studies, recent reviews emphasize that controlling enzymatic conversion and improving SFN stabilization are critical for achieving reliable and comparable bioavailability profiles [

40,

91,

92]. Accordingly, the development of optimized extraction, stabilization, and manufacturing strategies is a prerequisite for advancing SFN from dietary supplementation to clinically deployable interventions [

90,

93].

5.2. Biomarker-Guided and Mechanism-Driven Clinical Trial Design

Given the predominance of biomarker-based outcomes in existing SFN trials, future clinical studies should integrate pharmacokinetic and target-engagement biomarkers, such as urinary dithiocarbamate metabolites or tissue-level molecular readouts, to support dose optimization and mechanistic interpretation [

40,

94]. This biomarker-centered approach is particularly relevant in cancer prevention and early interception settings, where long-term clinical endpoints, such as cancer incidence or survival, are impractical to assess within a feasible study period [

14,

19,

26]. Under these circumstances, surrogate molecular changes function as the principal indicators of biological activity, underscoring the importance of carefully selecting and validating biomarkers [

40]. Accordingly, the harmonization of biomarker panels and outcome definitions across studies is essential to enable cross-trial comparisons and improve the interpretability and translational value of emerging clinical evidence [

14,

40].

5.3. Advanced Delivery Systems and Combination Strategies

A major limitation of the therapeutic application of SFN is its physicochemical instability and rapid metabolism, which limit sustained systemic and tissue-level exposure following conventional administration [

95]. Advanced delivery approaches, including microencapsulation, enzyme-stabilized formulations, and nanotechnology-based carriers, have been explored to improve SFN stability, bioaccessibility, and pharmacokinetic consistency, with preclinical studies indicating enhanced intracellular uptake and tissue accumulation compared to free SFN [

91,

93,

96]. Nevertheless, delivery optimization alone is unlikely to establish SFN as a primary anticancer therapy, given the ongoing challenges related to scalability, long-term safety, regulatory complexity, and interstudy heterogeneity [

97]. Accordingly, the therapeutic potential of SFN is realized using combination strategies rather than monotherapies [

98]. In this context, SFN has been demonstrated to modulate redox homeostasis, stress-response signaling, epigenetic regulation, and cancer stem cell–associated pathways implicated in therapeutic resistance, thereby providing a mechanistic rationale for its use as an adjunctive agent [

37,

99]. Based on these properties, combination regimens that pair SFN with cytotoxic chemotherapy, targeted therapies, or radiotherapy represent a rational translational approach, particularly when guided by a mechanism-informed design and biomarker-based evaluations of pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic interactions [

14,

98,

100].

6. Conclusions

SFN is a well-characterized dietary isothiocyanate with substantial experimental and clinical evidence supporting its role in cancer prevention and biological modulation of tumor-related processes. Preclinical studies have consistently demonstrated that SFN exerts anticancer effects by regulating redox homeostasis, epigenetic mechanisms, and stress-response signaling, thereby influencing key processes involved in carcinogenesis.

Human studies further indicate that SFN, predominantly administered as SFN-rich preparations, is generally well tolerated and is associated with the modulation of cancer-relevant molecular biomarkers in clinical settings, despite its low and variable systemic bioavailability. Although current clinical evidence is largely derived from early phase and biomarker-driven trials rather than from definitive outcome studies, these findings provide important proof-of-mechanism for the biological activity of SFN in humans.

Collectively, these data suggest that SFN is unlikely to function as a standalone anticancer drug. However, its translational potential is considered more appropriate within cancer prevention frameworks or as a supportive mechanism-based intervention that complements established therapeutic strategies. Future progress in this field will depend on the development of standardized formulations with reproducible bioavailability, biomarker-guided clinical trial designs, and rigorous integration of mechanistic endpoints.

Thus, SFN is a scientifically substantiated dietary phytochemical with significant potential for cancer prevention and translational oncology research. Continued efforts to align formulation science, mechanistic understanding, and clinical study design are essential to define its optimal role in evidence-based cancer intervention paradigms.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.Y.J., D.K., N.K.L., E.I., and N.D.K.; Investigation, J.Y.J.; Writing—Original draft preparation, J.Y.J.; Writing—Review and Editing, D.K., N.K.L., E.I., and N.D.K.; Supervision, E.I. and N.D.K.; Project Administration, J.Y.J. and N.D.K.; Funding acquisition, N.D.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF), funded by the Ministry of Education (2022R1A6A3A01085858 and RS-2025-25437656; J.Y.J.), and by a National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korean government (MSIT) (2021R1F1A1051265; N.D.K.).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data presented in this study are available upon request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AKT |

Protein kinase B |

| AMPK |

AMP-activated protein kinase |

| AP-1 |

Activator protein 1 |

| ARE |

Antioxidant response element |

| CKMT2-AS1 |

Creatine kinase, mitochondrial 2 antisense RNA 1 |

| DNMT |

DNA methyltransferase |

| GPX4 |

Glutathione peroxidase 4 |

| G2/M |

G2/M phase of the cell cycle |

| HDAC |

Histone deacetylase |

| HO-1 |

Heme oxygenase 1 |

| IL-1β |

Interleukin-1 beta |

| IL-6 |

Interleukin-6 |

| Keap1 |

Kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1 |

| MAPK |

Mitogen-activated protein kinase |

| mTOR |

Mechanistic target of rapamycin |

| NADPH |

Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate |

| NF-κB |

Nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells |

| NQO1 |

NAD(P)H quinone dehydrogenase 1 |

| Nrf2 |

Nuclear factor erythroid 2–related factor 2 |

| PI3K |

Phosphoinositide 3-kinase |

| ROS |

Reactive oxygen species |

| SFN |

Sulforaphane |

| STAT3 |

Signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 |

| TRAMP |

Transgenic adenocarcinoma of mouse prostate |

References

- Briones-Herrera, A.; Eugenio-Pérez, D.; Reyes-Ocampo, J.G.; Rivera-Mancía, S.; Pedraza-Chaverri, J. New highlights on the health-improving effects of sulforaphane. Food funct. 2018, 9, 2589–2606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bessetti, R.N.; Litwa, K.A. Broccoli for the brain: A review of the neuroprotective mechanisms of sulforaphane. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2025, 19, 1601366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treasure, K.; Harris, J.; Williamson, G. Exploring the anti-inflammatory activity of sulforaphane. Immunol. Cell Biol. 2023, 101, 805–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conzatti, A.; Colombo, R.; Siqueira, R.; Campos-Carraro, C.; Turck, P.; de Castro, A.L.; Belló-Klein, A.; da Rosa Araujo, A.S. Sulforaphane improves redox homeostasis and right ventricular contractility in a model of pulmonary hypertension. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 2024, 83, 612–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, P.; Tian, S.; Teng, C.; Huang, L.; Liu, X.; Wang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Li, B.; Shan, Y. Sulforaphane improves lipid metabolism by enhancing mitochondrial function and biogenesis in vivo and in vitro. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2019, 63, 1800795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahn, A.; Castillo, A. Potential of sulforaphane as a natural immune system enhancer: A review. Molecules 2021, 26, 752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merchant, H.J.; Forteath, C.; Gallagher, J.R.; Dinkova-Kostova, A.T.; Ashford, M.L.; McCrimmon, R.J.; McNeilly, A.D. Activation of the Nrf2 pathway by sulforaphane improves hypoglycaemia-induced cognitive impairment in a rodent model of type 1 diabetes. Antioxidants 2025, 14, 308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, K.; Liang, W.; Fragoulis, A.; Yan, W.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, Q.; Ma, C.; He, Z.; Buhl, E.M.; Li, Y.; et al. Sulforaphane regulates hepatic autophagy and apoptosis by modulating Kupffer cells’ polarization via Nrf2/HO-1 pathway in the murine hemorrhagic shock/resuscitation model. Eur. J. Trauma Emerg. Surg. 2025, 51, 218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Wang, Z.; Jin, X.; Zhang, M.; Shen, M.; Li, D. Oral sulforaphane intervention protects against diabetic cardiomyopathy in db/db Mice: Focus on cardiac lipotoxicity and substrate metabolism. Antioxidants 2025, 14, 603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masoumvand, M.; Ramezani, E.; Eshaghi Milasi, Y.; Baradaran Rahimi, V.; Askari, V.R. New horizons for promising influences of sulforaphane in the management of metabolic syndrome: A mechanistic review. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch. Pharmacol. 2025, 398, 4933–4946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, S.; Sharma, R.; Verma, A.K. Sulforaphane and gut-brain axis: An overview of its impact on intestinal inflammation, microbiota composition, and neurodegeneration. ACS Food Sci. Technol. 2025, 5, 3645–3661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reihani, A.; Mohammadi, E.; Amiri, F.T.; Seyedabadi, M.; Shaki, F. Sulforaphane attenuates oxidative stress, senescence, and ferroptosis induced by cigarette smoke extract in vitro and in vivo via upregulating the expression of SIRT1. Res. Pharm. Sci. 2025, 20, 853–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dana, A.-H.; Alejandro, S.-P. Role of sulforaphane in endoplasmic reticulum homeostasis through regulation of the antioxidant response. Life Sci. 2022, 299, 120554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Chen, Q.; Qiao, X.; Wang, J.; Ali, Z.T.A.; Li, J.; Yin, L. Sulforaphane in cancer precision medicine: From biosynthetic origins to multiscale mechanisms and clinical translation. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1702860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.-x.; Zou, Y.-j.; Zhuang, X.-b.; Chen, S.-x.; Lin, Y.; Li, W.-l.; Lin, J.-j.; Lin, Z.-q. Sulforaphane suppresses EMT and metastasis in human lung cancer through miR-616-5p-mediated GSK3β/β-catenin signaling pathways. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2017, 38, 241–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernkopf, D.B.; Daum, G.; Brückner, M.; Behrens, J. Sulforaphane inhibits growth and blocks Wnt/β-catenin signaling of colorectal cancer cells. Oncotarget 2018, 9, 33982–33994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mordecai, J.; Ullah, S.; Ahmad, I. Sulforaphane and its protective role in prostate cancer: A mechanistic approach. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 6979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuran, D.; Pogorzelska, A.; Wiktorska, K. Breast cancer prevention-is there a future for sulforaphane and its analogs? Nutrients 2020, 12, 1559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ElKhalifa, D.; Al-Ziftawi, N.; Awaisu, A.; Alali, F.; Khalil, A. Efficacy and tolerability of sulforaphane in the therapeutic management of cancers: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Front. Oncol. 2023, 13, 1251895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, P.; Zhang, B.; Li, Y.; Yuan, Q. Potential mechanisms of cancer prevention and treatment by sulforaphane, a natural small molecule compound of plant-derived. Mol. Med. 2024, 30, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russo, M.; Spagnuolo, C.; Russo, G.L.; Skalicka-Woźniak, K.; Daglia, M.; Sobarzo-Sánchez, E.; Nabavi, S.F.; Nabavi, S.M. Nrf2 targeting by sulforaphane: A potential therapy for cancer treatment. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2018, 58, 1391–1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atwell, L.L.; Beaver, L.M.; Shannon, J.; Williams, D.E.; Dashwood, R.H.; Ho, E. Epigenetic regulation by sulforaphane: Opportunities for breast and prostate cancer chemoprevention. Curr. Pharmacol. Rep. 2015, 1, 102–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, Y.; Park, M.N.; Choi, M.; Upadhyay, T.K.; Kang, H.N.; Oh, J.M.; Min, S.; Yang, J.-U.; Kong, M.; Ko, S.-G. Sulforaphane regulates cell proliferation and induces apoptotic cell death mediated by ROS-cell cycle arrest in pancreatic cancer cells. Front. Oncol. 2024, 14, 1442737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herman-Antosiewicz, A.; Johnson, D.E.; Singh, S.V. Sulforaphane causes autophagy to inhibit release of cytochrome C and apoptosis in human prostate cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2006, 66, 5828–5835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greco, G.; Schnekenburger, M.; Catanzaro, E.; Turrini, E.; Ferrini, F.; Sestili, P.; Diederich, M.; Fimognari, C. Discovery of sulforaphane as an inducer of ferroptosis in U-937 leukemia cells: Expanding its anticancer potential. Cancers 2021, 14, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coutinho, L.d.L.; Junior, T.C.T.; Rangel, M.C. Sulforaphane: An emergent anti-cancer stem cell agent. Front. Oncol. 2023, 13, 1089115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.H.; Sung, B.; Kang, Y.J.; Hwang, S.Y.; Kim, M.J.; Yoon, J.-H.; Im, E.; Kim, N.D. Sulforaphane inhibits hypoxia-induced HIF-1α and VEGF expression and migration of human colon cancer cells. Int J. Oncol. 2015, 47, 2226–2232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Lu, Q.; Li, N.; Xu, M.; Miyamoto, T.; Liu, J. Sulforaphane suppresses metastasis of triple-negative breast cancer cells by targeting the RAF/MEK/ERK pathway. NJP Breast Cancer 2022, 8, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shankar, S.; Ganapathy, S.; Srivastava, R.K. Sulforaphane enhances the therapeutic potential of TRAIL in prostate cancer orthotopic model through regulation of apoptosis, metastasis, and angiogenesis. Clin. Cancer Res. 2008, 14, 6855–6866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clack, G.; Moore, C.; Ruston, L.; Wilson, D.; Koch, A.; Webb, D.; Mallard, N. A phase 1 randomized, placebo-controlled study evaluating the safety, tolerability, and pharmacokinetics of enteric-coated stabilized sulforaphane (SFX-01) in male participants. Adv. Ther. 2025, 42, 216–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Egner, P.A.; Chen, J.G.; Zarth, A.T.; Ng, D.K.; Wang, J.B.; Kensler, K.H.; Jacobson, L.P.; Muñoz, A.; Johnson, J.L.; Groopman, J.D.; et al. Rapid and sustainable detoxication of airborne pollutants by broccoli sprout beverage: Results of a randomized clinical trial in China. Cancer Prev. Res. (Phila.) 2014, 7, 813–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauman, J.E.; Hsu, C.H.; Centuori, S.; Guillen-Rodriguez, J.; Garland, L.L.; Ho, E.; Padi, M.; Bageerathan, V.; Bengtson, L.; Wojtowicz, M.; et al. Randomized crossover trial evaluating detoxification of tobacco carcinogens by broccoli seed and sprout extract in current smokers. Cancers (Basel) 2022, 14, 2129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahey, J.W.; Holtzclaw, W.D.; Wehage, S.L.; Wade, K.L.; Stephenson, K.K.; Talalay, P. Sulforaphane bioavailability from glucoraphanin-rich broccoli: Control by active endogenous myrosinase. PloS one 2015, 10, e0140963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barba, F.J.; Nikmaram, N.; Roohinejad, S.; Khelfa, A.; Zhu, Z.; Koubaa, M. Bioavailability of glucosinolates and their breakdown products: Impact of processing. Front. Nutr. 2016, 3, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahey, J.W.; Wade, K.L.; Stephenson, K.K.; Panjwani, A.A.; Liu, H.; Cornblatt, G.; Cornblatt, B.S.; Ownby, S.L.; Fuchs, E.; Holtzclaw, W.D.; et al. Bioavailability of sulforaphane following ingestion of glucoraphanin-rich broccoli sprout and seed extracts with active myrosinase: A pilot study of the effects of proton pump inhibitor administration. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, G.; Liu, G.; Wang, P.; Li, J. Microorganisms-an effective tool to intensify the utilization of sulforaphane. Foods 2022, 11, 3775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asif Ali, M.; Khan, N.; Kaleem, N.; Ahmad, W.; Alharethi, S.H.; Alharbi, B.; Alhassan, H.H.; Al-Enazi, M.M.; Razis, A.F.A.; Modu, B.; et al. Anticancer properties of sulforaphane: Current insights at the molecular level. Front. Oncol. 2023, 13, 1168321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, H.; Rani, I.; Sharma, V.; Sharma, U.; Dimri, T.; Kumar, M.; Chauhan, R.; Chauhan, A.; Kaur, D.; Haque, S. Sulforaphane: A natural organosulfur having potential to modulate apoptosis and survival signalling in cancer. Discov. Oncol. 2025, 16, 2049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baralić, K.; Živanović, J.; Marić, Đ.; Bozic, D.; Grahovac, L.; Antonijević Miljaković, E.; Ćurčić, M.; Buha Djordjevic, A.; Bulat, Z.; Antonijević, B.; et al. Sulforaphane-a compound with potential health benefits for disease prevention and treatment: Insights from pharmacological and toxicological experimental studies. Antioxidants (Basel) 2024, 13, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saito, A.; Ishikawa, S.; Yang, K.; Sawa, A.; Ishizuka, K. Sulforaphane as a potential therapeutic agent: A comprehensive analysis of clinical trials and mechanistic insights. J. Nutr. Sci. 2025, 14, e65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Tang, L. Discovery and development of sulforaphane as a cancer chemopreventive phytochemical 1. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2007, 28, 1343–1354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dmytriv, T.R.; Lushchak, O.; Lushchak, V.I. Glucoraphanin conversion into sulforaphane and related compounds by gut microbiota. Front. Physiol. 2025, 16, 1497566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldelli, S.; Lombardo, M.; D’Amato, A.; Karav, S.; Tripodi, G.; Aiello, G. Glucosinolates in human health: Metabolic pathways, bioavailability, and potential in chronic disease prevention. Foods 2025, 14, 912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Men, X.; Han, X.; Oh, G.; Im, J.-H.; Lim, J.S.; Cho, G.H.; Choi, S.-I.; Lee, O.-H. Plant sources, extraction techniques, analytical methods, bioactivity, and bioavailability of sulforaphane: A review. Food Sci. Biotechnol. 2024, 33, 539–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R., G.; Pandav, A.K.; S., S.; Devi, R.A.; Gatla, S. Impact of different technologies and methods to increase the shelf life and maintain the sulforaphane content in broccoli: A review. J. Adv. Biol. Biotechnol. 2024, 27, 900–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouranis, J.A.; Beaver, L.M.; Wong, C.P.; Choi, J.; Hamer, S.; Davis, E.W.; Brown, K.S.; Jiang, D.; Sharpton, T.J.; Stevens, J.F. Sulforaphane and sulforaphane-nitrile metabolism in humans following broccoli sprout consumption: Inter-individual variation, association with gut microbiome composition, and differential bioactivity. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2024, 68, 2300286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egner, P.A.; Kensler, T.W.; Chen, J.-G.; Gange, S.J.; Groopman, J.D.; Friesen, M.D. Quantification of sulforaphane mercapturic acid pathway conjugates in human urine by high-performance liquid chromatography and isotope-dilution tandem mass spectrometry. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2008, 21, 1991–1996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, S.; Winnik, B.; Buckley, B.; Mi, L.; Chung, F.-L.; Cook, T.J. Simultaneous determination of sulforaphane and its major metabolites from biological matrices with liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectroscopy. J. Chromatogr. B Analyt. Technol. Biomed. Life Sci. 2006, 840, 99–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al Janobi, A.A.; Mithen, R.F.; Gasper, A.V.; Shaw, P.N.; Middleton, R.J.; Ortori, C.A.; Barrett, D.A. Quantitative measurement of sulforaphane, iberin and their mercapturic acid pathway metabolites in human plasma and urine using liquid chromatography-tandem electrospray ionisation mass spectrometry. J. Chromatogr. B. Analyt. Technol. Biomed. Life Sci. 2006, 844, 223–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egner, P.A.; Chen, J.G.; Wang, J.B.; Wu, Y.; Sun, Y.; Lu, J.H.; Zhu, J.; Zhang, Y.H.; Chen, Y.S.; Friesen, M.D. Bioavailability of sulforaphane from two broccoli sprout beverages: Results of a short-term, cross-over clinical trial in Qidong, China. Cancer Prev. Res. 2011, 4, 384–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, J.D.; Hsu, A.; Riedl, K.; Bella, D.; Schwartz, S.J.; Stevens, J.F.; Ho, E. Bioavailability and inter-conversion of sulforaphane and erucin in human subjects consuming broccoli sprouts or broccoli supplement in a cross-over study design. Pharmacol. Res. 2011, 64, 456–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahey, J.W.; Liu, H.; Batt, H.; Panjwani, A.A.; Tsuji, P. Sulforaphane and brain health: From pathways of action to effects on specific disorders. Nutrients 2025, 17, 1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savic, N.; Markelic, M.; Stancic, A.; Velickovic, K.; Grigorov, I.; Vucetic, M.; Martinovic, V.; Gudelj, A.; Otasevic, V. Sulforaphane prevents diabetes-induced hepatic ferroptosis by activating Nrf2 signaling axis. BioFactor 2024, 50, 810–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinkova-Kostova, A.T.; Fahey, J.W.; Kostov, R.V.; Kensler, T.W. KEAP1 and done? Targeting the NRF2 pathway with sulforaphane. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 69, 257–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.; Gu, C.; Lian, P.; Wazir, J.; Lu, R.; Ruan, B.; Wei, L.; Li, L.; Pu, W.; Peng, Z.; et al. Sulforaphane alleviates psoriasis by enhancing antioxidant defense through KEAP1-NRF2 pathway activation and attenuating inflammatory signaling. Cell Death Dis. 2023, 14, 768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, L.; Palliyaguru, D.L.; Kensler, T.W. Frugal chemoprevention: Targeting Nrf2 with foods rich in sulforaphane. Semin. Oncol. 2016, 43, 146–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dashwood, R.H.; Ho, E. Dietary agents as histone deacetylase inhibitors: Sulforaphane and structurally related isothiocyanates. Nutr. Rev. 2008, 66, S36–S38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dashwood, R.H.; Ho, E. Dietary histone deacetylase inhibitors: From cells to mice to man. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2007, 17, 363–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Su, Z.-Y.; Khor, T.O.; Shu, L.; Kong, A.-N.T. Sulforaphane enhances Nrf2 expression in prostate cancer TRAMP C1 cells through epigenetic regulation. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2013, 85, 1398–1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.W.; Wang, M.; Sun, N.X.; Qing, Y.; Yin, T.F.; Li, C.; Wu, D. Sulforaphane-induced epigenetic regulation of Nrf2 expression by DNA methyltransferase in human Caco-2 cells. Oncol. Lett. 2019, 18, 2639–2647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, X.; Jiang, X.; Meng, L.; Dong, X.; Shen, Y.; Xin, Y. Anticancer activity of sulforaphane: The epigenetic mechanisms and the Nrf2 signaling pathway. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2018, 2018, 5438179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adtani, P.N.; Al-Bayati, S.A.A.F.; Elsayed, W.S. Sulforaphane from brassica oleracea induces apoptosis in oral squamous carcinoma cells via p53 activation and mitochondrial membrane potential dysfunction. Pharmaceuticals 2025, 18, 393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Z.; Feng, J.; Yang, M.; Feng, D.; Wang, X.; Liu, W. Mechanism of sulforaphane in treatment of pancreatic cancer cell based on network pharmacology and in vitro experiments. Bioorg. Chem. 2025, 163, 108754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Z.; Ren, Y.; Yang, L.; Jia, A.; Hu, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Zhao, W.; Yu, B.; Zhao, W.; Zhang, J. Inhibiting autophagy enhances sulforaphane-induced apoptosis via targeting NRF2 in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2021, 11, 1246–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Li, J.; Zheng, Z.; Hu, Y.; Li, L.; Wu, W. Sulforaphane downregulated fatty acid synthase and inhibited microtubule-mediated mitophagy leading to apoptosis. Cell Death Dis. 2021, 12, 917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iida, Y.; Okamoto-Katsuyama, M.; Maruoka, S.; Mizumura, K.; Shimizu, T.; Shikano, S.; Hikichi, M.; Takahashi, M.; Tsuya, K.; Okamoto, S. Effective ferroptotic small-cell lung cancer cell death from SLC7A11 inhibition by sulforaphane. Oncol. Lett. 2021, 21, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, B.; Cao, P.; Wang, J.-h.; Feng, W.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, H. Sulforaphane triggers Sirtuin 3-mediated ferroptosis in colorectal cancer cells via activating the adenosine 5 ‘-monophosphate (AMP)-activated protein kinase/mechanistic target of rapamycin signaling pathway. Hum. Exp. Toxicol. 2024, 43, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otoo, R.A.; Allen, A.R. Sulforaphane’s multifaceted potential: From neuroprotection to anticancer action. Molecules 2023, 28, 6902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.-t.; Zhang, B.; Liu, C.; Wang, T.; Li, M.-m.; Han, Y.-z.; Xu, Q.-m.; Lu, R.-h.; Xu, K.; Wang, Y.-d. Sulforaphane targets STAT3-CKMT2-AS1 to suppress gastric cancer via PSMB8 downregulation and AIMP1 stabilization. Phytomedicine 2025, 157428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saavedra-Leos, M.Z.; Jordan-Alejandre, E.; Puente-Rivera, J.; Silva-Cázares, M.B. Molecular pathways related to sulforaphane as adjuvant treatment: A nanomedicine perspective in breast cancer. Medicina 2022, 58, 1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sah, D.K.; Arjunan, A.; Park, S.Y.; Lee, B.; Jung, Y.D. Sulforaphane inhibits IL-1β-induced IL-6 by suppressing ROS production, AP-1, and STAT3 in colorectal cancer HT-29 cells. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, K.B.; Kim, S.H.; Hahm, E.R.; Pore, S.K.; Jacobs, B.L.; Singh, S.V. Prostate cancer chemoprevention by sulforaphane in a preclinical mouse model is associated with inhibition of fatty acid metabolism. Carcinogenesis 2018, 39, 826–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xuan, Y.; Xu, J.; Que, H.; Zhu, J. Effects of sulforaphane on prostate cancer stem cells-like properties: In vitro and molecular docking studies. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2024, 762, 110216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, C.M.; Tsai, T.H.; Lee, K.T.; Hsu, Y.C. Sulforaphane-induced cell mitotic delay and inhibited cell proliferation via regulating CDK5R1 upregulation in breast cancer cell lines. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, N.P.; Rangel, M.C.; Merchant, A.S.; MacKinnon, G.; Cuttitta, F.; Salomon, D.S.; Kim, Y.S. Sulforaphane suppresses the growth of triple-negative breast cancer stem-like cells in vitro and in vivo. Cancer Prev. Res. (Phila.) 2019, 12, 147–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hao, Q.; Wang, M.; Sun, N.X.; Zhu, C.; Lin, Y.M.; Li, C.; Liu, F.; Zhu, W.W. Sulforaphane suppresses carcinogenesis of colorectal cancer through the ERK/Nrf2-UDP glucuronosyltransferase 1A metabolic axis activation. Oncol. Rep. 2020, 43, 1067–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Sun, Y.; Huang, X.; Qiao, C.; Zhang, W.; Liu, P.; Wang, M. Sulforaphane inhibits self-renewal of lung cancer stem cells through the modulation of sonic Hedgehog signaling pathway and polyhomeotic homolog 3. AMB Express 2021, 11, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, M.J.; Kim, Y.H. Anti-cancer effect of sulforaphane in human pancreatic cancer cells Mia PaCa-2. Cancer Rep. (Hoboken) 2024, 7, e70074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, L.; Wang, J.; Wang, X.; Zheng, S.; Liang, K.; Kang, Y.E.; Chang, J.W.; Koo, B.S.; Liu, L.; Gal, A.; et al. Sulforaphane suppresses bladder cancer metastasis via blocking actin nucleation-mediated pseudopodia formation. Cancer lett. 2024, 601, 217145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Effects of Sulforaphane in Patients With Biochemical Recurrence of Prostate Cancer. 2010. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT01228084 (accessed on 29 December 2025).

- Alumkal, J.J.; Slottke, R.; Schwartzman, J.; Cherala, G.; Munar, M.; Graff, J.N.; Beer, T.M.; Ryan, C.W.; Koop, D.R.; Gibbs, A.; et al. A phase II study of sulforaphane-rich broccoli sprout extracts in men with recurrent prostate cancer. Invest. New Drugs 2015, 33, 480–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chemoprevention of Prostate Cancer, HDAC Inhibition and DNA Methylation. 2010. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT01265953 (accessed on 29 December 2025).

- Zhang, Z.; Garzotto, M.; Davis, E.W., 2nd; Mori, M.; Stoller, W.A.; Farris, P.E.; Wong, C.P.; Beaver, L.M.; Thomas, G.V.; Williams, D.E.; et al. Sulforaphane bioavailability and chemopreventive activity in men presenting for biopsy of the prostate gland: A randomized controlled trial. Nutr. Cancer 2020, 72, 74–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sulforaphane: A Dietary Histone Deacetylase (HDAC) Inhibitor in Ductal Carcinoma in Situ (DCIS). 2009. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT00843167 (accessed on 29 December 2025).

- Atwell, L.L.; Zhang, Z.; Mori, M.; Farris, P.; Vetto, J.T.; Naik, A.M.; Oh, K.Y.; Thuillier, P.; Ho, E.; Shannon, J. Sulforaphane bioavailability and chemopreventive activity in women scheduled for breast biopsy. Cancer Prev. Res. (Phila.) 2015, 8, 1184–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Atwell, L.L.; Farris, P.E.; Ho, E.; Shannon, J. Associations between cruciferous vegetable intake and selected biomarkers among women scheduled for breast biopsies. Public Health Nutr. 2016, 19, 1288–1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evaluating the Effect of Broccoli Sprouts (Sulforaphane) on Cellular Proliferation, an Intermediate Marker of Breast Cancer Risk. 2009. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT00982319 (accessed on 29 December 2025).

- Randomized Clinical Trial of Lung Cancer Chemoprevention With Sulforaphane in Former Smokers. 2017. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT03232138 (accessed on 29 December 2025).

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, W.; Zhao, Y.; Peng, R.; Zhang, Z.; Xu, Z.; Simal-Gandara, J.; Yang, H.; Deng, J. Bioactive sulforaphane from cruciferous vegetables: advances in biosynthesis, metabolism, bioavailability, delivery, health benefits, and applications. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2025, 65, 3027–3047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, W.; Cremonini, E.; Mastaloudis, A.F.; Mitchell, A.E.; Bornhorst, G.M.; Oteiza, P.I. Optimization of sulforaphane bioavailability from a glucoraphanin-rich broccoli seed extract in a model of dynamic gastric digestion and absorption by Caco-2 cell monolayers. Food Funct. 2025, 16, 314–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangla, B.; Javed, S.; Sultan, M.H.; Kumar, P.; Kohli, K.; Najmi, A.; Alhazmi, H.A.; Al Bratty, M.; Ahsan, W. Sulforaphane: A review of its therapeutic potentials, advances in its nanodelivery, recent patents, and clinical trials. Phytother. Res. 2021, 35, 5440–5458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houghton, C.A. Sulforaphane: Its “coming of age” as a clinically relevant nutraceutical in the prevention and treatment of chronic disease. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2019, 2019, 2716870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redha, A.A.; Torquati, L.; Bows, J.R.; Gidley, M.J.; Cozzolino, D. Microencapsulation of broccoli sulforaphane using whey and pea protein: In vitro dynamic gastrointestinal digestion and intestinal absorption by Caco-2-HT29-MTX-E12 cells. Food Funct. 2025, 16, 71–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, J.M.; Kensler, T.W.; Dacic, S.; Hartman, D.J.; Wang, R.; Balogh, P.A.; Sufka, P.; Turner, M.A.; Fuhrer, K.; Seigh, L.; et al. Randomized phase II clinical trial of sulforaphane in former smokers at high risk for lung cancer. Cancer Prev. Res. (Phila.) 2025, 18, 335–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, H.F.; Mao, X.Y.; Du, M. Metabolism, absorption, and anti-cancer effects of sulforaphane: An update. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2022, 62, 3437–3452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshammari, A.N.; Alfawaz, M.S.; Alenezi, Y.M.; Al-Ghafari, A.B.; Al Doghaither, H.A.; Elmorsy, E.M.; Atta, M.M.F.; El-Raghi, A.A. Nanoliposome-mediated delivery of sulforaphane suppresses Ehrlich ascites carcinoma growth and improves liver integrity and therapeutic outcomes in a murine model. BMC Cancer 2025, 25, 1838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, R.; Zhu, Y. Encapsulation of sulforaphane from cruciferous vegetables in mPEG-PLGA nanoparticles enhances cadmium’s inhibitory effect on HepG2 cells. Nanomaterials 2025, 15, 615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhazmi, N.; Subahi, A. Impact of sulforaphane on breast cancer progression and radiation therapy outcomes: A systematic review. Cureus 2025, 17, e78060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.M.; Wu, H.; Tollefsbol, T.O. A novel combinatorial approach using sulforaphane-and withaferin A-rich extracts for prevention of estrogen receptor-negative breast cancer through epigenetic and gut microbial mechanisms. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 12091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sailo, B.L.; Liu, L.; Chauhan, S.; Girisa, S.; Hegde, M.; Liang, L.; Alqahtani, M.S.; Abbas, M.; Sethi, G.; Kunnumakkara, A.B. Harnessing sulforaphane potential as a chemosensitizing agent: A comprehensive review. Cancers 2024, 16, 244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Figure 1.

Metabolism, bioavailability, and systemic actions of sulforaphane (SFN). SFN is generated from its precursor, glucoraphanin, which is abundant in cruciferous vegetables, through the action of plant-derived or gut microbiota–derived myrosinase during food processing and digestion. Following intestinal absorption, SFN circulates in both free and conjugated forms and exerts pleiotropic biological effects, including activation of the Nrf2–antioxidant response element (ARE) pathway, epigenetic modulation, and regulation of programmed cell death pathways. Concurrently, SFN is rapidly metabolized via the mercapturic acid pathway as a hepatic detoxification process through sequential conjugation with glutathione (SFN–GSH), cysteine (SFN–CYS), and N-acetylcysteine (SFN–NAC), leading to subsequent renal or fecal excretion. Inter-individual variability in SFN bioavailability is influenced by factors such as myrosinase activity, gut microbiome composition, and formulation stability, resulting in rapid systemic clearance and a relatively short biological half-life. Figure created using BioRender.com. ARE, antioxidant response element; CYS, cysteine; GSH, glutathione; NAC, N-acetylcysteine; Nrf2, nuclear factor erythroid 2–related factor 2; SFN, sulforaphane.

Figure 1.

Metabolism, bioavailability, and systemic actions of sulforaphane (SFN). SFN is generated from its precursor, glucoraphanin, which is abundant in cruciferous vegetables, through the action of plant-derived or gut microbiota–derived myrosinase during food processing and digestion. Following intestinal absorption, SFN circulates in both free and conjugated forms and exerts pleiotropic biological effects, including activation of the Nrf2–antioxidant response element (ARE) pathway, epigenetic modulation, and regulation of programmed cell death pathways. Concurrently, SFN is rapidly metabolized via the mercapturic acid pathway as a hepatic detoxification process through sequential conjugation with glutathione (SFN–GSH), cysteine (SFN–CYS), and N-acetylcysteine (SFN–NAC), leading to subsequent renal or fecal excretion. Inter-individual variability in SFN bioavailability is influenced by factors such as myrosinase activity, gut microbiome composition, and formulation stability, resulting in rapid systemic clearance and a relatively short biological half-life. Figure created using BioRender.com. ARE, antioxidant response element; CYS, cysteine; GSH, glutathione; NAC, N-acetylcysteine; Nrf2, nuclear factor erythroid 2–related factor 2; SFN, sulforaphane.

Figure 2.

Multi-target anticancer mechanisms of sulforaphane (SFN). SFN exerts pleiotropic anticancer effects by concurrently modulating multiple interconnected molecular pathways. SFN activates the Nrf2–antioxidant response element (ARE) signaling axis by disrupting Keap1, resulting in the induction of cytoprotective and detoxification enzymes, including HO-1 and NQO1. In parallel, SFN suppresses major pro-survival and inflammatory signaling pathways, such as nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-κB), signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3), phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K)/protein kinase B (AKT), and mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK). SFN also modulates epigenetic regulators, including histone deacetylases (HDACs) and DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs), thereby contributing to epigenetic reprogramming of aberrant transcriptional states in cancer cells. Collectively, these signaling alterations converge to induce multiple programmed cell death pathways, such as apoptosis, autophagy, and ferroptosis, and suppress cancer stem cell–associated properties, underpinning the broad anticancer potential of SFN across diverse tumor contexts. Figure created using BioRender.com. Ac, acetylation; AKT, protein kinase B; ARE, antioxidant response element; DNMTs, DNA methyltransferases; HDACs, histone deacetylases; HO-1, heme oxygenase-1; Keap1, Kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1; MAPK, mitogen-activated protein kinase; NF-κB, nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells; NQO1, NAD(P)H quinone dehydrogenase 1; Nrf2, nuclear factor erythroid 2–related factor 2; PI3K, phosphoinositide 3-kinase; SFN, sulforaphane; sMaf, small musculoaponeurotic fibrosarcoma protein; STAT3, signal transducer and activator of transcription 3.

Figure 2.

Multi-target anticancer mechanisms of sulforaphane (SFN). SFN exerts pleiotropic anticancer effects by concurrently modulating multiple interconnected molecular pathways. SFN activates the Nrf2–antioxidant response element (ARE) signaling axis by disrupting Keap1, resulting in the induction of cytoprotective and detoxification enzymes, including HO-1 and NQO1. In parallel, SFN suppresses major pro-survival and inflammatory signaling pathways, such as nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-κB), signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3), phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K)/protein kinase B (AKT), and mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK). SFN also modulates epigenetic regulators, including histone deacetylases (HDACs) and DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs), thereby contributing to epigenetic reprogramming of aberrant transcriptional states in cancer cells. Collectively, these signaling alterations converge to induce multiple programmed cell death pathways, such as apoptosis, autophagy, and ferroptosis, and suppress cancer stem cell–associated properties, underpinning the broad anticancer potential of SFN across diverse tumor contexts. Figure created using BioRender.com. Ac, acetylation; AKT, protein kinase B; ARE, antioxidant response element; DNMTs, DNA methyltransferases; HDACs, histone deacetylases; HO-1, heme oxygenase-1; Keap1, Kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1; MAPK, mitogen-activated protein kinase; NF-κB, nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells; NQO1, NAD(P)H quinone dehydrogenase 1; Nrf2, nuclear factor erythroid 2–related factor 2; PI3K, phosphoinositide 3-kinase; SFN, sulforaphane; sMaf, small musculoaponeurotic fibrosarcoma protein; STAT3, signal transducer and activator of transcription 3.

Table 1.

Summary of preclinical evidence for the anticancer effects of SFN across multiple cancer types.

Table 1.

Summary of preclinical evidence for the anticancer effects of SFN across multiple cancer types.

| Cancer Type |

Models

(In vitro / In vivo) |

Key Findings |

Major Mechanisms |

Refs. |

| Prostate cancer |

LNCaP, 22Rv1 cells (in vitro) |

↓: ACC1, FASN, CPT1A, SREBP1 |

↓: fatty-acid synthesis pathway |

[72] |

| TRAMP mice (in vivo) |

↓: total free fatty acids, total phospholipids, acetyl-CoA, ATP, neutral lipid droplets |

↓: fatty-acid metabolism

↑: Nrf2-mediated cytoprotective signaling |

[72] |

| PC-3 CSC-like cells (in vitro) |

↓: tumor sphere formation, PCSC markers (CD44, ALDH1, Oct4, Nanog) |

↓: Wnt/β-catenin & Hedgehog pathways

↑: apoptosis |

[73] |

Breast

cancer |

MDA-MB-231 (in vitro) |

↓: RAF family proteins (ARAF, BRAF, and CRAF), MEK, p-ERK |

↓: metastasis signaling |

[28] |

| MDA-MB-231, ZR-75-1 cells (in vitro) |

↓: Cyclin B1, CDC2, CDC25C

↑: MPM-2 activity, CDK5R1, CDK5 |

↓: proliferation

↑: apoptosis, mitotic arrest (G2/M) |

[74] |

| MDA-MB-231-Luc-D3H1 CSC-like cells (in vitro) |

↓: mammosphere formation (1 , 2 , 3 ), CSC population (CD44⁺/CD24⁻/CD49f⁺), CSC-associated stemness signaling(CR1, CR3, WNT3, NOTCH4, FOXD3) |

↓: stemness pathway, self-renewal capacity |

[75] |

| MDA-MB-231-Luc-D3H1 xenograft (in vivo) |

↓: tumor volume, Cripto-1 protein expression (CR1/CR3; IHC trend) |

↓: CSC-driven tumor growth |

[75] |

Cololectal

cancer |

HCT116 cells (in vitro) |

↓: cell viability, SLC7A11

↑: ROS, MDA, intracellular Fe ⁺ |

↑: SIRT3–AMPK–mTOR axis–mediated ferroptosis |

[67] |

| HT-29 cells (in vitro) |

↓: IL-6 mRNA, IL-6 secretion, IL-6 promoter activity, ROS, p-p38 MAPK, p-STAT3, p-c-Jun/AP-1, invasion, migration |

↓: ROS–p38 MAPK–AP-1/STAT3 inflammatory signaling |

[71] |

| HT-29, SW480 cells (in vitro) |

↓: cell viability, colony formation, EdU proliferation, migration (wound healing & transwell)

↑: ROS, G0/G1 arrest, apoptosis, p-ERK/ERK ratio, Nrf2, UGT1A |

↑: ERK–Nrf2–UGT1A metabolic detoxification pathway |

[76] |

| Lung cancer |

A549, H460 CD133⁺ cells (in vitro) |

↓: cell viability, tumorsphere formation,

SHH signaling (Shh, Smo, Gli1), PHC3 |

↓: Sonic Hedgehog signaling and PHC3-associated self-renewal |

[77] |

| Pancreatic cancer |

Mia PaCa-2 cells (in vitro) |

↓: cell viability, p-NF-κB p65, NF-κB p65, NF-κB p50, c-Myc, BCL-2

↑: p-GSK-3β, β-catenin, cleaved caspase-3 and PARP |

↑: apoptosis via modulation of the GSK-3β/β-catenin pathway |

[78] |

| Bladder cancer |

T24, UMUC3 cells (in vitro) |

↓: pseudopodia formation (lamellipodia, filopodia, invadopodia), cell migration and invasion, CTTN (cortactin), WASL, ACTR2/ARP2, ATP production, ECAR, OCR |

↓: actin nucleation–driven pseudopodia formation (CTTN–WASL–ARP2/3, AKT1-ATP axis) |

[79] |

| T24-luc tail-vein metastasis model (in vivo) |

↓: lung metastatic burden, metastatic tumor growth, Actr2s/Arp2 and CTTN expression in metastatic lung tissue |

↓: pseudopodia-dependent metastatic colonization |

[79] |

Table 2.

Clinical trials evaluating SFN in cancer and cancer-risk settings with reported outcomes.

Table 2.

Clinical trials evaluating SFN in cancer and cancer-risk settings with reported outcomes.

| Cancer Type |

Phase |

Study Design |

Main Outcomes |

Clinical Trial ID |

Refs. |

| Prostate cancer |

Phase 2 |

Single-arm interventional study |

≥50% PSA decline achieved in 1 of 20 patients |

NCT01228084 |

[80,81] |

| Not applicable |

Interventional biopsy window study |

Increase in urinary SFN metabolites |

NCT01265953 |

[82,83] |

| Breast cancer |

Phase 2 |

Randomized, placebo-controlled presurgical window study |

HDAC activity decreased in breast tissue |

NCT00843167 |

[84,85,86] |

| Phase 2 |

Interventional breast tissue biomarker study |

Cancer-related biomarkers showed changes in breast tissue |

NCT00982319 |

[87] |

| Lung cancer risk (former smokers) |

Phase 2 |

Randomized, placebo-controlled lung tissue biomarker study |

Modulation of bronchial dysplasia index and Ki-67 proliferation marker over 12 months |

NCT03232138 |

[88] |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).