Submitted:

29 December 2025

Posted:

30 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

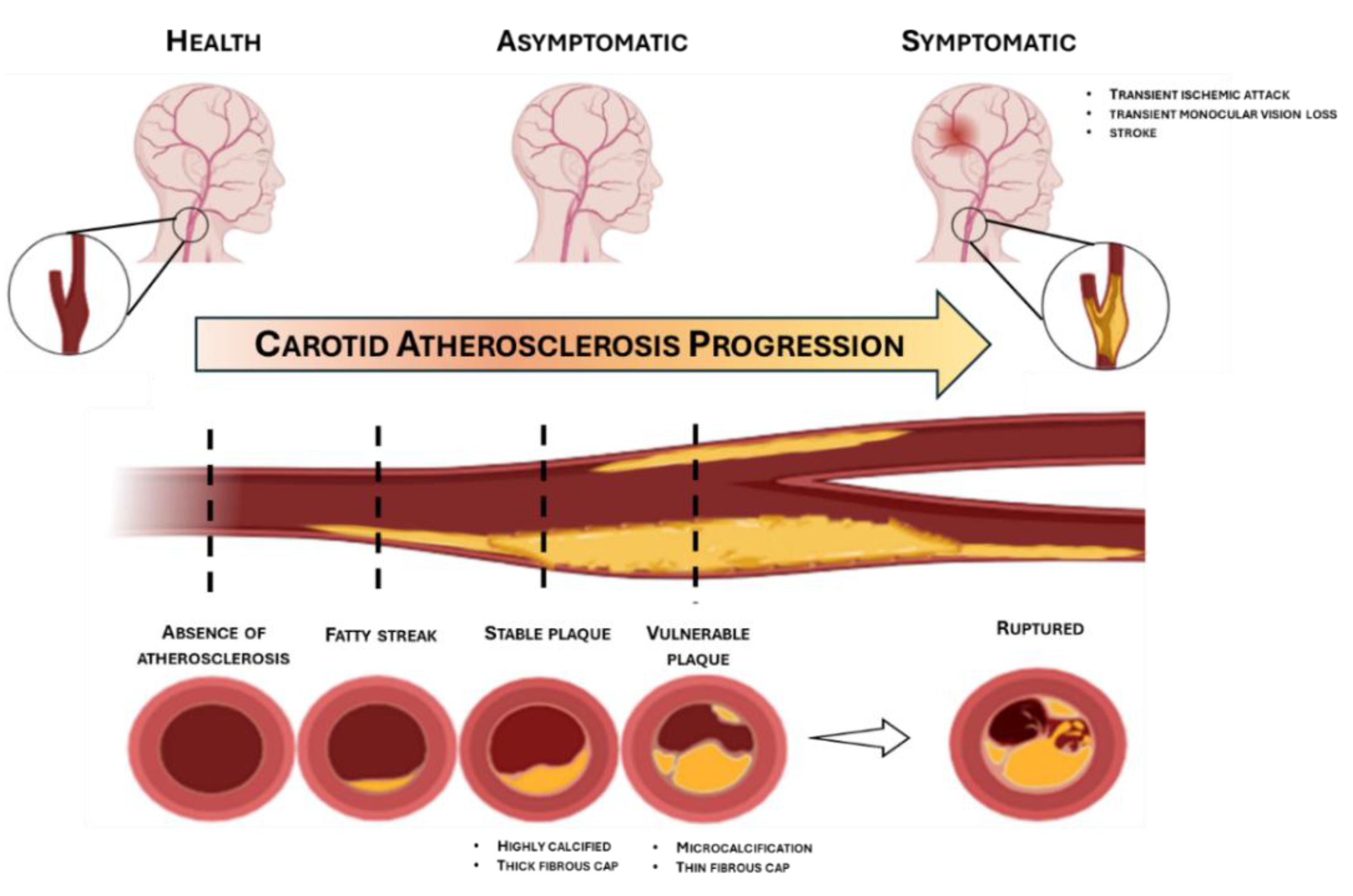

Background and aims. Carotid atherosclerosis remains one of the primary etiological factors underlying ischemic stroke, contributing to adult neurological disability and mortality. In recent years, non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs) have emerged as key regulators of gene expression, actively modulating molecular pathways involved in atherogenesis. This systematic review, the first to be exclusively focused on carotid atherosclerosis, aimed at synthesizing current findings on the differential expression of ncRNAs throughout the natural history of the disease, thus providing the first comprehensive attempt to delineate a stage-specific ncRNA expression profile in carotid disease. Methods. A comprehensive literature search was conducted in PubMed and Scopus databases in January 2025, following PRISMA guidelines. Original studies involving human subjects with carotid atherosclerosis, evaluating the expression of intracellular or circulating ncRNAs were included and then categorized according to their association with cardiovascular risk factors, carotid intima-media thickness (cIMT), presence of atherosclerotic plaques, plaque vulnerability, clinical symptoms, and ischemic stroke. Results. Out of 148 articles initially identified, 49 met the inclusion criteria and were analyzed in depth. Among the different classes of ncRNAs, microRNAs (miRNAs) were the most frequently reported as dysregulated, followed by circular RNAs (circRNAs) and long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs). Notably, the majority of identified ncRNAs were implicated in key pathogenic mechanisms such as inflammatory signaling, vascular smooth muscle cell (VSMC) phenotypic modulation, and ABCA1-mediated cholesterol efflux. Conclusions. Collectively, the evidence underscores the association and possible involvement of ncRNAs in the initiation and progression of carotid atherosclerosis and its cerebrovascular complications. Their relative stability in biological fluids and cell-specific expression profiles highlight their strong potential as minimally invasive biomarkers and – possibly – novel therapeutic targets.

Keywords:

Introduction

Methods

Study Design and Search Strategy

Systematic Search Phases

Study Risk of Bias Assessment

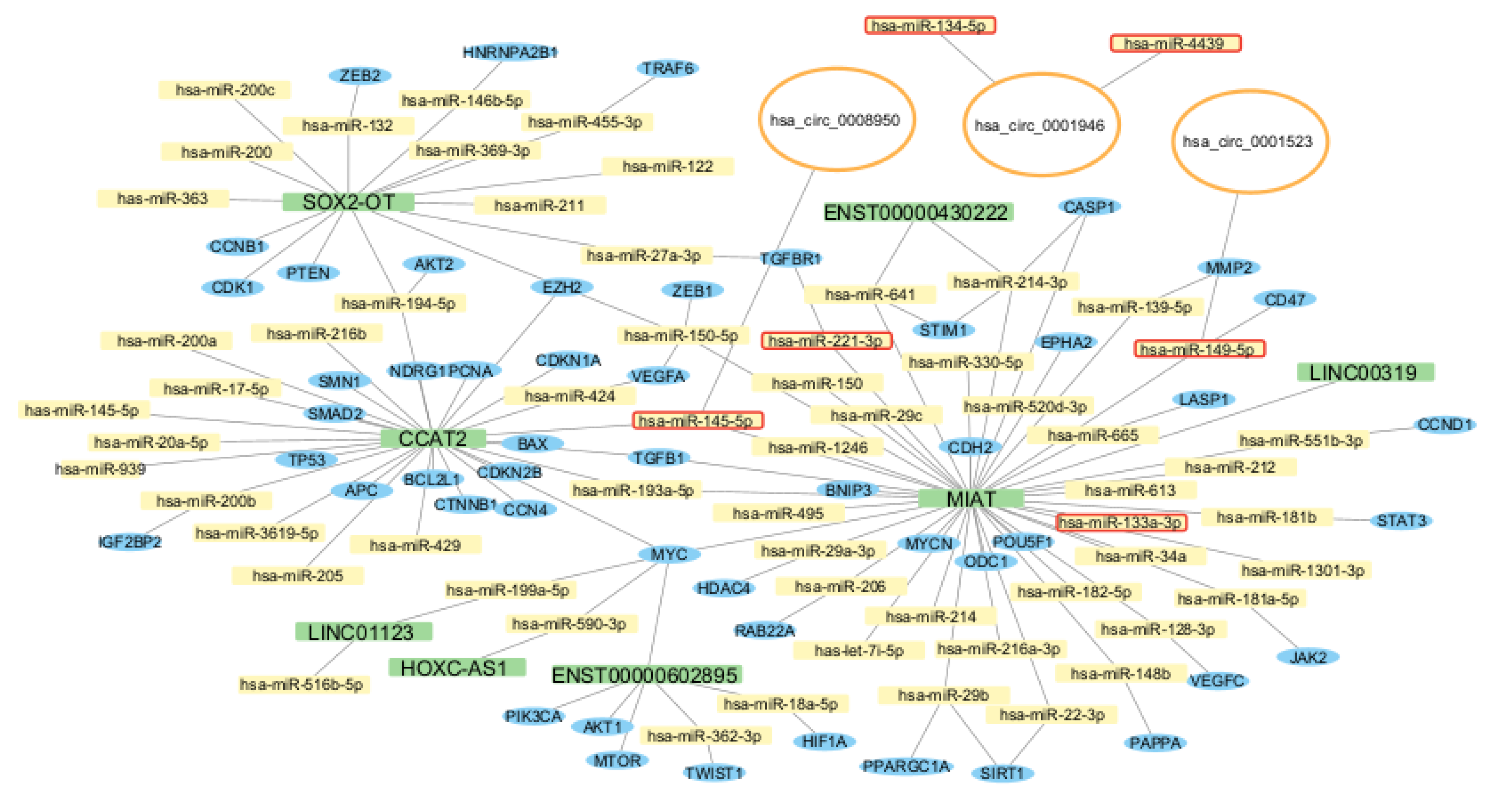

Network-Level Analysis of Identified ncRNAs

Results

Flow Diagram

Study Selection and Characteristics

Synthesized Findings

Discussion

Limitations

Conclusion

List of Abbreviations

| ABCA1 | ATP Binding Cassette Subfamily A Member 1 |

| APC | Adenomatous Polyposis Coli |

| CEA | carotid endarterectomy |

| cIMT | carotid Intima- Media Thickness |

| circRNAs | circular RNAs |

| COX2 | cycloxigenase-2 |

| GSEA | Gene Set Enrichment Analysis |

| HDL | high-density lipoproteins |

| HIF-1 | Hypoxia Inducible Factor 1 |

| hs-CRP | high-sensitivity C-reactive protein |

| ICAM | intracellular adhesion molecules |

| IL | interleukin |

| KLF5 | Krueppel-like factor 5 |

| LDL | low-density lipoproteins |

| lncRNAs | long non-coding RNAs |

| Lp PLA 2 | phospholipase a2 |

| LRNC | lipid-rich necrotic core |

| MCP-1 | monocyte chemoattractant factor-1 |

| miRNAs | microRNAs |

| MSigDB | Molecular Signatures Database |

| ncRNAs | non-coding RNAs |

| NLRP3 | Nod-like receptor protein 3 |

| NO | nitric oxide |

| OSF | Open Science Framework |

| PBMC | peripheral blood mononuclear cells |

| PICOS | Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcomes, and Study Design |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses |

| RBPs | RNA-binding proteins |

| RISC | RNA-induced silencing complex |

| TNF-a | tumor necrosis factor- a |

| VCAM | vascular cell adhesion molecules |

| VSMC | vascular smooth muscle cells |

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Authors’ contributions

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Libby, P; Buring, JE; Badimon, L; Hansson, GK; Deanfield, J; Bittencourt, MS; et al. Atherosclerosis. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2019, 5, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamaguchi, T; Morino, K. Perivascular mechanical environment: A narrative review of the role of externally applied mechanical force in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis. Vol. 9, Front Cardiovasc Med. 2022, 19:9, 944356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dempsey, RJ; Vemuganti, R; Varghese, T; Hermann, BP. A review of carotid atherosclerosis and vascular cognitive decline: A new understanding of the keys to symptomology. Neurosurgery 2010, Vol. 67 67, 484–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weber, C; Noels, H. Atherosclerosis: Current pathogenesis and therapeutic options. Nat Med. 2011, Vol. 17 17, 1410–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gimbrone, MA; García-Cardeña, G. Endothelial Cell Dysfunction and the Pathobiology of Atherosclerosis. Circ Res. 2016, 118, 620–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, MR; Sinha, S; Owens, GK. Vascular Smooth Muscle Cells in Atherosclerosis. Circ Res. 2016, 118, 692–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, K. Pathophysiology and medical treatment of carotid artery stenosis. Int J Angiol. 2014, 24, 158–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bir, SC; Kelley, RE. Carotid atherosclerotic disease: a systematic review of pathogenesis and management. Brain Circ. 2022, 8, 127–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theofilis, P; Sagris, M; Oikonomou, E; Antonopoulos, AS; Siasos, G; Tsioufis, C; et al. Inflammatory mechanisms contributing to endothelial dysfunction. Biomedicines 2021, 9, 781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck-Joseph, J; Lehoux, S. Molecular Interactions Between Vascular Smooth Muscle Cells and Macrophages in Atherosclerosis. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2021, 8, 737934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saba, L; Cau, R; Vergallo, R; Kooi, ME; Staub, D; Faa, G; et al. Carotid artery atherosclerosis: mechanisms of instability and clinical implications. Eur Heart J. 2025, 46, 904–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, D; Rai, V; Agrawal, DK. Non-Coding RNAs in Regulating Plaque Progression and Remodeling of Extracellular Matrix in Atherosclerosis. Int J Mol Sci. 2022, 23, 13731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shang, R; Lee, S; Senavirathne, G; Lai, EC. microRNAs in action: biogenesis, function and regulation. Nat Rev Genet. 2023, 24, 816–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mattick, JS; Amaral, PP; Carninci, P; Carpenter, S; Chang, HY; Chen, LL; et al. Long non-coding RNAs: definitions, functions, challenges and recommendations. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2023, 24, 430–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z; Yang, T; Xiao, J. Circular RNAs: Promising Biomarkers for Human Diseases. EBioMedicine 2018, 34, 267–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D; Liberati, A; Tetzlaff, J; Altman, DG; Antes, G; Atkins, D; et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 3, e123-30. [Google Scholar]

- Page, MJ; McKenzie, JE; Bossuyt, PM; Boutron, I; Hoffmann, TC; Mulrow, CD; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 29, 372:n71. [Google Scholar]

- Downes, MJ; Brennan, ML; Williams, HC; Dean, RS. Development of a critical appraisal tool to assess the quality of cross-sectional studies (AXIS). BMJ Open 2016, 6, e011458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafieian-Kopaei, M; Setorki, M; Doudi, M; Baradaran, A; Nasri, H. Atherosclerosis: Process, Indicators, Risk Factors and New Hopes. Int J Prev Med. 2014, 5, 927–46. [Google Scholar]

- Poredos, P; Gregoric, ID; Jezovnik, MK. Inflammation of carotid plaques and risk of cerebrovascular events. Ann Transl Med. 2020, 8, 1281–1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Libby, P; Ridker, PM; Hansson, GK. Inflammation in Atherosclerosis. From Pathophysiology to Practice. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009, 54, 2129–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B; Yang, H; Lu, X; Wang, L; Li, H; Chen, S; et al. MiR-520b inhibits endothelial activation by targeting NF-κB p65-VCAM1 axis. Biochem Pharmacol. 2021, 188, 114540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Sala, L; Prattichizzo, F; Ceriello, A. The link between diabetes and atherosclerosis. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2019, 26, 15–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H; Mai, P; He, F; Zhang, Y. Expression of miRNA-29c in the carotid plaque and its association with diabetic mellitus. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2024, 11, 1276066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henning, RJ. Obesity and obesity-induced inflammatory disease contribute to atherosclerosis: a review of the pathophysiology and treatment of obesity. Am J Cardiovasc Dis. 2021, 11, 504–29. [Google Scholar]

- Roush, S; Slack, FJ. The let-7 family of microRNAs. Trends in Cell Biology 2008, Vol. 18 18, 505–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brennan, E; Wang, B; McClelland, A; Mohan, M; Marai, M; Beuscart, O; et al. Protective effect of let-7 miRNA family in regulating inflammation in diabetes-associated atherosclerosis. Diabetes 2017, 66, 2266–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aroca-Esteban, J; Souza-Neto, F V.; Aguilar-Latorre, C; Tribaldo-Torralbo, A; González-López, P; Ruiz-Simón, R; et al. Potential protective role of let-7d-5p in atherosclerosis progression reducing the inflammatory pathway regulated by NF-κB and vascular smooth muscle cells proliferation. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis. 2024, 1870, 167327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandolini, C; Santovito, D; Marcantonio, P; Buttitta, F; Bucci, M; Ucchino, S; et al. Identification of microRNAs 758 and 33b as potential modulators ofABCA1 expression in human atherosclerotic plaques. Nutr, Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2015, 25, 202–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanashyan, MM; Shabalina, AA; Kuznetsova, PI; Raskurazhev, AA. miR-33a and Its Association with Lipid Profile in Patients with Carotid Atherosclerosis. Int J Mol Sci. 2023, 24, 6376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rayner, KJ; Esau, CC; Hussain, FN; McDaniel, AL; Marshall, SM; Van Gils, JM; et al. Inhibition of miR-33a/b in non-human primates raises plasma HDL and lowers VLDL triglycerides. Nature 2011, 478, 404–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramirez, CM; Dávalos, A; Goedeke, L; Salerno, AG; Warrier, N; Cirera-Salinas, D; et al. MicroRNA-758 regulates cholesterol efflux through posttranscriptional repression of ATP-binding cassette transporter A1. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2011, 31, 2707–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levine, GN; Al-Khatib, SM; Beckman, JA; Birtcher, KK; Bozkurt, B; Brindis, RG; et al. Guideline for the Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Management of High Blood Pressure in Adults. Hypertension 2018, 71, 13–115. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, B; Mancia, G; Spiering, W; Agabiti Rosei, E; Azizi, M; Burnier, M; et al. 2018 Practice guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension of the European Society of Hypertension (ESH) and the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Blood Press 2018, 27, 314–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z; Qian, H; Tao, Z; Xie, Y; Zhi, S; Sheng, L; et al. Circulating circular RNAs as biomarkers for the diagnosis of essential hypertension with carotid plaque. Clin Exp Hypertens. 2022, 44, 601–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, H; Zhang, Z; Tao, Z; Xie, Y; Yin, Y; He, W; et al. Association of Circular RNAs levels in blood and Essential Hypertension with Carotid Plaque. Clin Exp Hypertens. 2023, 45, 2180020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Oord, SCH; Sijbrands, EJG; ten Kate, GL; van Klaveren, D; van Domburg, RT; van der Steen, AFW; et al. Carotid intima-media thickness for cardiovascular risk assessment: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Atherosclerosis 2013, Vol. 228 228(1), 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minin, EOZ; Paim, LR; Lopes, ECP; Bueno, LCM; Carvalho-Romano, LFRS; Marques, ER; et al. Association of circulating mir-145-5p and mir-let7c and atherosclerotic plaques in hypertensive patients. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 1840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, J; Hu, Y. Diagnostic and prognostic significance of lncRNA SOX2-OT in patients with carotid atherosclerosis. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2022, 22, 211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, YX; Lu, YK; Liu, YH; Zhang, J; Wang, S; Dong, J; et al. Identification of circular RNA hsa_circ_0034621 as a novel biomarker for carotid atherosclerosis and the potential function as a regulator of NLRP3 inflammasome. Atherosclerosis 2024, 391, 117491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, S; Jun, J; Kim, J; Park, H; Cho, Y; Kim, G. Expression of miRNAs targeting ATP binding cassette transporter 1 (ABCA1) among patients with significant carotid artery stenosis. Biomedicines 2021, 9, 920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magenta, A; Sileno, S; D’Agostino, M; Persiani, F; Beji, S; Paolini, A; et al. Atherosclerotic plaque instability in carotid arteries: MiR-200c as a promising biomarker. Clin Sci. 2018, 132, 2423–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raskurazhev, AA; Tanashyan, MM; Shabalina, AA; Kuznetsova, PI; Kornilova, AA; Burmak, AG. Micro-RNA in Patients with Carotid Atherosclerosis. Hum Physiol. 2020, 46, 880–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X; Shi, H; Wang, Y; Hu, J; Sun, Z; Xu, S. Down-regulation of hsa-miR-148b inhibits vascular smooth muscle cells proliferation and migration by directly targeting HSP90 in atherosclerosis. Am J Transl Res. 2017, 9, 629–37. [Google Scholar]

- Tsai, PC; Liao, YC; Wang, YS; Lin, HF; Lin, RT; Juo, SHH. Serum microrna-21 and microrna-221 as potential biomarkers for cerebrovascular disease. J Vasc Res. 2013, 50, 346–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markus, B; Grote, K; Worsch, M; Parviz, B; Boening, A; Schieffer, B; et al. Differential expression of microRNAs in endarterectomy specimens taken from patients with asymptomatic and symptomatic carotid plaques. PLoS One 2016, 11, e0161632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, P; He, XY; Xu, M. The Role of miRNA-146a and Proinflammatory Cytokines in Carotid Atherosclerosis. Biomed Res Int. 2020, 2020, 6657734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L; Wang, Y; Qiao, F. microRNA-223 and microRNA-126 are clinical indicators for predicting the plaque stability in carotid atherosclerosis patients. J Hum Hypertens. 2022, 37, 788–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y; Wu, Y; Wang, C; Hu, W; Zou, S; Ren, H; et al. MiR-127-3p enhances macrophagic proliferation via disturbing fatty acid profiles and oxidative phosphorylation in atherosclerosis. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2024, 193, 36–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R; Qin, Y; Zhu, G; Li, Y; Xue, J. Low serum miR-320b expression as a novel indicator of carotid atherosclerosis. J Clin Neurosci. 2016, 33, 252–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luque, A; Farwati, A; Krupinski, J; Aran, JM. Association between low levels of serum miR-638 and atherosclerotic plaque vulnerability in patients with high-grade carotid stenosis. J Neurosurg. 2019, 131, 72–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Z; Hu, H; Yin, M; Li, X; Li, J; Liu, L; et al. miR-145 is critical for modulation ofvascular smooth muscle cell proliferation in human carotid artery stenosis. J Biol Regul Homeost Agents 2018, 32, 507–16. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, CQ; Jin, WX; Yu, GF. Correlation between carotid atherosclerotic plaque properties and serum levels of lncRNA CCAT2 and miRNA-216b. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2020, 24, 7033–7038. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Eken, SM; Jin, H; Chernogubova, E; Li, Y; Simon, N; Sun, C; et al. MicroRNA-210 enhances fibrous cap stability in advanced atherosclerotic lesions. Circ Res. 2017, 120, 633–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, Y; Luo, Q; Huang, K; Sun, T; Luo, S. Long Noncoding RNA AC078850.1 Induces NLRP3 Inflammasome-Mediated Pyroptosis in Atherosclerosis by Upregulating ITGB2 Transcription via Transcription Factor HIF-1α. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 1734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fasolo, F; Jin, H; Winski, G; Chernogubova, E; Pauli, J; Winter, H; et al. Long Noncoding RNA MIAT Controls Advanced Atherosclerotic Lesion Formation and Plaque Destabilization. Circulation 2021, 144, 1567–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, G; Gu, M; Zhang, Y; Zhao, G; Gu, Y. LINC01123 promotes cell proliferation and migration via regulating miR-1277-5p/KLF5 axis in ox-LDL-induced vascular smooth muscle cells. J Mol Histol. 2021, 52, 943–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, C; Li, T. Long non-coding RNA SENCR alleviates endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition via targeting miR-126a. Arch Med Sci. 2019, 19, 180–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, JJ; Jin, J; Li, YH; Wang, C; Bai, J; Jiang, QJ; et al. LncRNA FGF7-5 and lncRNA GLRX3 together inhibits the formation of carotid plaque via regulating the miR-2681-5p/ERCC4 axis in atherosclerosis. Cell Cycle 2022, 22, 165–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C; Hu, YW; Zhao, JJ; Ma, X; Zhang, Y; Guo, FX; et al. Long noncoding RNA HOXC-AS1 suppresses Ox-LDL-induced cholesterol accumulation through promoting HOXC6 expression in THP-1 macrophages. DNA Cell Biol. 2016, 35, 722–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raju, S; Turner, ME; Cao, C; Abdul-Samad, M; Punwasi, N; Blaser, MC; et al. Multiomics unveils extracellular vesicle-driven mechanisms of endothelial communication in human carotid atherosclerosis. bioRxiv [Preprint] 2024, 23, 2024.06.21.599781. [Google Scholar]

- Thiriet, M; Delfour, M; Garon, A. Vascular Stenosis: An Introduction Hemodynamics and Drug Elution. In PanVascular Medicine, Second Edition; Lanzer, Ed.; Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 2015; pp. 781–868. [Google Scholar]

- North American Symtomatic Carotid Endarectomy Trial Collaborators. Beneficial effects of CEA in symptomatic patients with high grade carotid stenosis. N Engl J Med. 1991, 325, 445–53. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raskurazhev, AA; Kuznetsova, PI; Shabalina, AA; Tanashyan, MM. MicroRNA and Hemostasis Profile of Carotid Atherosclerosis. Int J Mol Sci. 2022, 23, 10974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balestrini, S; Lupidi, F; Balucani, C; Altamura, C; Vernieri, F; Provinciali, L; et al. One-year progression of moderate asymptomatic carotid stenosis predicts the risk of vascular events. Stroke 2013, 44, 792–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolz, S; Górriz, D; Tembl, JI; Sánchez, D; Fortea, G; Parkhutik, V; et al. Circulating MicroRNAs as novel biomarkers of stenosis progression in asymptomatic carotid stenosis. Stroke 2017, 48, 10–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawai, K; Kawakami, R; Finn, A V.; Virmani, R. Differences in Stable and Unstable Atherosclerotic Plaque. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2024, 44, 1474–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redgrave, JN; Gallagher, P; Lovett, JK; Rothwell, PM. Critical cap thickness and rupture in symptomatic carotid plaques. Stroke 2008, 39, 1722–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miceli, G; Basso, MG; Pintus, C; Pennacchio, AR; Cocciola, E; Cuffaro, M; et al. Molecular Pathways of Vulnerable Carotid Plaques at Risk of Ischemic Stroke: A Narrative Review. Int J Mol Sci. 2024, Vol. 25 25, 4351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L; Xu, L. Combined Value of Serum miR-124, TNF-α and IL-1β for Vulnerable Carotid Plaque in Acute Cerebral Infarction. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak 2020, 30, 385–8. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, S; ming, Ye Z; Chen, S; ying, Luo X; li, Chen S; Mao, L; et al. MicroRNA-23a-5p promotes atherosclerotic plaque progression and vulnerability by repressing ATP-binding cassette transporter A1/G1 in macrophages. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2018, 123, 139–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, R; Cao, Y; Li, H; Hu, Z; Zhang, H; Zhang, L; et al. miR-532-3p-CSF2RA Axis as a Key Regulator of Vulnerable Atherosclerotic Plaque Formation. Can J Cardiol. 2020, 36, 1782–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saba, L; Nardi, V; Cau, R; Gupta, A; Kamel, H; Suri, JS; et al. Carotid Artery Plaque Calcifications: Lessons from Histopathology to Diagnostic Imaging. Stroke 2022, 53, 290–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katano, H; Nishikawa, Y; Yamada, H; Yamada, K; Mase, M. Differential Expression of microRNAs in Severely Calcified Carotid Plaques. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2018, 27, 108–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vasuri, F; Ciavarella, C; Fittipaldi, S; Pini, R; Vacirca, A; Gargiulo, M; et al. Different histological types of active intraplaque calcification underlie alternative miRNA-mRNA axes in carotid atherosclerotic disease. Virchows Archiv 2020, 476, 307–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, X; Sun, Y; Han, T; Zhu, J; Xie, Y; Wang, S; et al. Upregulation of miR-330-5p is associated with carotid plaque’s stability by targeting Talin-1 in symptomatic carotid stenosis patients. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2019, 19, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badacz, R; Przewłocki, T; Gacoń, J; Stępień, E; Enguita, FJ; Karch, I; et al. Circulating miRNA levels differ with respect to carotid plaque characteristics and symptom occurrence in patients with carotid artery stenosis and provide information on future cardiovascular events. Advances in Interventional Cardiology 2018, 14, 75–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, MH; Zhang, RQ; Huang, XS; Zhou, J; Guo, Z; Xu, BF; et al. Transcriptomic and Proteomic Profiling of Human Stable and Unstable Carotid Atherosclerotic Plaques. Front Genet. 2021, 12, 755507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Y; Chun, Y; Qing Lian, Z; Wei Yong, Z; Mei Lan, Y; Huan, L; et al. circRNA-0006896-miR1264-DNMT1 axis plays an important role in carotid plaque destabilization by regulating the behavior of endothelial cells in atherosclerosis. Mol Med Rep. 2021, 23, 311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X; Deng, Y; Ye, L; Chen, B; Tong, J; Shi, W; et al. RNA Sequencing Reveals the Differentially Expressed circRNAs between Stable and Unstable Carotid Atherosclerotic Plaques. Genet Res. 2023, 2023, 7006749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanashyan, MM; Shabalina, AA; Annushkin, VA; Mazur, AS; Kuznetsova, PI; Raskurazhev, AA. Circulating microRNAs in Carotid Atherosclerosis: Complex Interplay and Possible Associations with Atherothrombotic Stroke. Int J Mol Sci. 2024, 25, 10026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grosse, GM; Derda, AA; Stauss, RD; Neubert, L; Jonigk, DD; Kühnel, MP; et al. Circulating microRNAs in Symptomatic and Asymptomatic Carotid Stenosis. Front Neurol. 2021, 12, 755827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caparosa, EM; Sedgewick, AJ; Zenonos, G; Zhao, Y; Carlisle, DL; Stefaneanu, L; et al. Regional Molecular Signature of the Symptomatic Atherosclerotic Carotid Plaque. Neurosurgery 2019, 85, E284–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Golledge, J; Greenhalgh, RM; Davies, AH. The Symptomatic Carotid Plaque. Stroke 2000, 31, 774–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J; Liu, Y; Tian, P; Xing, L; Huang, X; Fu, C; et al. Exosomal circSCMH1/miR-874 ratio in serum to predict carotid and coronary plaque stability. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2023, 11:10, 1277427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B; Xi, W; Bai, Y; Liu, X; Zhang, Y; Li, L; et al. FTO-dependent m6A modification of Plpp3 in circSCMH1-regulated vascular repair and functional recovery following stroke. Nat Commun. 2023, 14, 489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazan, HA; Hatfield, SA; O’Malley, CB; Brooks, AJ; Lightell, D; Woods, TC. Acute Loss of MIR-221 and MIR-222 in the Atherosclerotic Plaque Shoulder Accompanies Plaque Rupture. Stroke 2015, 46, 3285–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazan, HA; Hatfield, SA; Brug, A; Brooks, AJ; Lightell, DJ; Woods, TC. Carotid Plaque Rupture Is Accompanied by an Increase in the Ratio of Serum circR-284 to miR-221 Levels. Circ Cardiovasc Genet. 2017, 10, e001720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, XC; Wu, JJ; Yuan, ST; Yuan, FL. Recent insights and perspectives into the role of the miRNA-29 family in innate immunity. Int J Mol Med. 2025, 55, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vavassori, C; Cipriani, E; Colombo, GI. Circulating MicroRNAs as Novel Biomarkers in Risk Assessment and Prognosis of Coronary Artery Disease. Eur Cardiol. 2022, 17, 17:e06. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiełbowski, K; Żychowska, J; Bakinowska, E; Pawlik, A. Non-Coding RNA Involved in the Pathogenesis of Atherosclerosis—A Narrative Review. Diagnostics 2024, 14, 1981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Study and reference | City and Country | Number of participants | ncRNA | Dysregulation | Source of ncRNA | Proposed mechanism |

| Endothelial inflammation | ||||||

| Yang, et al. 2021[22] | Beijing (China) | N=3 control N=3 CA |

hsa-miR-520b | downregulated in CA | tissue | Direct interaction of hsa-miR-520b and RelA transcript |

| Diabetes mellitus (DM) | ||||||

| Wang, et al. 2024 [24] | Luoyang (China) | N= 25 DM N= 15 non-DM |

hsa-miR-29c | Downregulated in DM patients | tissue | VSMC phenotype switching |

| Obesity | ||||||

| Aroca-Esteban, et al. 2024 [28] | Madrid (Spain) | N=7 control N=4 lean CA N=10 overweight CA N=5 obese CA |

let-7d-5p | upregulated in overweight (but not obese) | plasma (extracellular vesicle) | protective role in the inflammation and stenosis of atherosclerotic plaque |

| Hypercholesterolemia | ||||||

| Mandolini, et al. 2015 [29] | Chieti (Italy) | N=15 control N=16 hypercholesterolemia |

hsa-miR-33b; hsa-miR-758 | upregulated in hypercholesterolemic group | tissue | hsa-miR-33b and hsa-miR-758 target ABCA1 |

| Tanashyan, et al. 2023 [30] | Moscow (Russia) | N=26 control N=35 hypercholesterolemia |

hsa-miR-33a-5p and -3p | upregulated in hypercholesterolemic group | blood | cholesterol efflux by targeting the ABCA1 |

| Essential hypertension (EH) | ||||||

| Zhang, et al. 2022 [35] | Ningbo (China) | N=100 control N=100 EH and CA |

circ-0105130; circ-0109569; circ-0072659; circ-0079586; circ-0064684 | upregulated in EH with carotid plaque | blood | possible target of hsa-miR-124 and hsa-miR-135a (in silico prediction) |

| Qian, et al. 2023[36] | Ningbo (China) | N= 64 control N=64 EH N=64 EH and CA |

circ-0127342 | downregulated in EH with carotid plaque | blood | circ-0127342 acts as sponge for hsa-miR-136-5p, hsa-miR-153-5p and hsa-miR-197-3p (bioinformatic analysis) |

| circ-0124782; circ-0131618; circ-0127342 | downregulated in EH with carotid plaque compared to healthy control |

| Study and reference | City and Country | Number of participants | Comparisons | Source of ncRNA | ncRNA | Dysregulation |

| Minin, et al. 2021[38] | São Paulo (Brazil) | N=72 IMT N=105 CA |

carotid plaque vs IMT of carotid plaque in hypertensive patients | serum | hsa-miR-145-5p; hsa-miR-let7c | upregulated in carotid plaque group |

| Tao, et al. 2022[58] | Shanghai (China) | N=90 control N=95 IMT |

asymptomatic CA patients vs healthy patients | serum | SOX2-OT | upregulated in IMT group |

| Yan, et al. 2024 [40] | Beijing (China) | N=131 CA N=119 IMT N=123 controls |

carotid plaque vs IMT in hypertensive patients | blood (PBMCs) | circ-0043621 | upregulated in CA compared to IMT; upregulated in IMT compared to control |

| Study 2020. | City and Country | Number of participants | Source of ncRNA | ncRNA | Dysregulation | Regulated process | |

| Huang et al. 2020[47] | Deyang (China) | N= 90 control N= 180 CA |

peripheral blood (PBMC) | hsa-miR-146a | upregulated in CA | Inflammation | |

| Aroca-Esteban, et al. 2024 [28] | Madrid (Spain) | N=7 control N=19 CA |

EV (from plasma) | let-7d-5p | upregulated in CA | Inflammation | |

| Jeong, et al. 2021[41] | Seoul (Korea) | N=6 control N=50 CA |

plasma | hsa-miR-33a-5p; hsa-miR-33b-5p; hsa-miR-148a-3p | upregulated in CA | Cholesterol efflux | |

| Tsai, et al. 2013 [45] | Kaohsiung and Taichung (Taiwan) | N= 157 control N= 66 CA |

serum | hsa-miR-21 | upregulated in CA | VSMC proliferation | |

| Liu, et al. 2024 [49] | Shanghai (China) | N=5 control N=23 CA |

tissue | hsa-miR-127-3p | upregulated in CA | Inflammation | |

| Magenta, et al. 2018 [42] | Rome (Italy) | N=19 control N= 24 CA |

plasma | hsa-miR-200c; hsa-miR-33a; hsa-miR-33b | upregulated in CA | Endothelial dysfunction | |

| N=10 arterioles N= 22 plaque |

tissue | hsa-miR-200c; hsa-miR-33a; hsa-miR-33b | upregulated in plaque | ||||

| Zhu, et al. 2022[48] | Hangzhou (China) | N= 25 control N=52 CA |

serum | hsa-miR-135a, hsa-miR-137, hsa-miR-149, hsa-miR-219a | upregulated in CA | - | |

| hsa-miR-126, hsa-miR-223, hsa-miR-101, hsa-miR-577, hsa-miR-384, hsa-miR-148 | downregulated in CA | ||||||

| Raskurazhev, et al. 2020[43] | Moscow (Russia) | N=11 control N=25 CA |

serum | hsa-miR-33a | upregulated in CA | Cholesterol efflux | |

| hsa-miR-126-3p; hsa-miR-126-5p; miR21-3p; hsa-miR-21-5p | downregulated in CA | Inflammation and shearstress | |||||

| Markus, et al. 2016 [46] | Marburg (Germany) | N= 15 control N=24 CA |

tissue | hsa-miR-19b; hsa-miR-21; hsa-miR-22; hsa-miR-143 | upregulated in CA (asymptomatic patients) | Macrophage infiltration and foam cell formation | |

| hsa-miR-1; hsa-miR-29b; let-7f | downregulated in CA | ||||||

| Zhang, et al. 2016 [50] | Tianjin (China) | N= 155 control N=177 CA |

serum | hsa-miR-320b | downregulated in CA | - | |

| Luque, et al. 2019 [51] | Barcelona (Spain) | N=36 control N= 22 CA |

serum | hsa-miR-638 | downregulated in CA (symptomatic patients) | VSMC migration and proliferation | |

| Han, et al. 2018[52] | Harbin (China) | N=50 control N= 37 CA |

plasma and tissue | hsa-miR-145 | downregulated in CA | VSMC proliferation | |

| Zhang, et al. 2017 [44] | Jinan (China) | N=46 control N=46 plaque |

tissue | hsa-miR-148b | downregulated in plaque | Endothelial dysfunction | |

| Eken, et al. 2017[54] | Stockholm (Sweden) | N=7 control N=7 plaque |

tissue | hsa-miR-210 | downregulated in plaque | VSMC proliferation | |

| Tian, et al. 2023 [55] | Harbin (China) | N=9 control N=18 CA |

blood (PBMC) | lncRNA AC078850.1 | upregulated in CA | Inflammation | |

| Fasolo, et al. 2021[56] | Stockholm (Sweden) | N=13 contol N=77 plaque |

tissue | MIAT | upregulated in plaque | VSMC proliferation, macrophages trans differentiation, inflammation | |

| Huang, et al. 2020 [53] | Wenzhou (China) | N=60 control N=60 CA |

serum | CCAT2 | upregulated in CA | - | |

| hsa-miR-216b | downregulated in CA | ||||||

| Weng, et al. 2020 [57] | Hainan (China) | N= 33control N= 35 CA |

serum | LINC01123 | upregulated in CA | VSMC migration and proliferation | |

| hsa-miR-1277-5p | downregulated in CA | ||||||

| N= 8 normal artery N= 8 plaque |

tissue | LINC01123 | upregulated in plaque | ||||

| Huang, et al. 2016 [60] | Canton (China) | N=5 normal renal artery N= 5 plaque |

tissue | HOXC-AS1 | downregulated in plaque | Foam cells formation | |

| Lou, et al. 2019 [58] | Ankang (China) | N=3 control N=5 CA |

tissue | SENCR | downregulated in CA | Endothelial to mesenchymal transiction | |

| hsa-miR-126a | upregulated in CA | ||||||

| Wu, et al. 2022 [59] | Shanghai (China) | N=50 control N=54 CA |

serum | lncRNA FGF7-5; lncRNA GLRX3 | downregulated in CA | Endothelial dysfunction | |

| hsa-miR-2681-5p | upregulated in CA | ||||||

| Yan, et al. 2024 [40] | Beijing (China) | N=50 control N=50 CA |

blood (PBMCs) | circ-0043621; circ-0051995; circ-123388 | upregulated in CA | Inflammation | |

| hsa-miR-223-3p | downregulated in CA |

| Study and reference | City and Country | Number of participants | Source of ncRNA | ncRNA | Dysregulation | Plaque’s features | |||

| Regional differences | |||||||||

| Raju, et al. 2024[61] | Toronto (Canada) | N=20 (paired: plaque and marginal zones) | tissue (EV) | hsa-miR-146a, hsa-miR-155, let-7a, hsa-miR-200b, hsa-miR-223, hsa-miR-181b | upregulated in plaque | fibroatheroma and calcification in all plaque samples. Plaque zones contained more macrophages (EV source), while VSMC predomitate in marginal zones. EVs per milligram of tissue compared to their matched marginal zones | |||

| Yan, et al. 2024[40] | Beijing (China) | N= 16 (paired: plaque vs proximal adjacent region) | tissue | circ-0043621 | upregulated in plaque | - | |||

| hsa-miR-223-3p | downregulated in plaque | ||||||||

| Jeong, et al. 2021[41] | Seoul (Korea) | N=50 (paired: internal vs common carotid region) | tissue | hsa-miR-148a-3p | upregulated in internal carotid | The internal carotid artery exhibited accumulated plaque and shrunken arterial walls compared with the common carotid artery | |||

| Stenosis severity | |||||||||

| Huang, et al. 2020 [47] | Deyang (China) | N=64 mild N=62 moderate N=54 severe |

peripheral blood (PBMC) | hsa-miR-146a | upregulated as the degrees of CAS stenosis increases | - | |||

| Raskurazhev, et al. 2022 [64] | Moscow (Russia) | N=31 moderate N= 30 advanced |

blood (leukocytes) | hsa-miR-126-5p/3p; hsa-miR-21-5p/3p; hsa-miR-29-3p | downregulated in advanced CA | - | |||

| hsa-miR-33a-5p/3p | upregulated in advanced CA | ||||||||

| Stenosis progression | |||||||||

| Dolz, et al. 2016 [66] | Valencia (Spain) | N=19 with stenosis progression N=41 without stenosis progression |

plasma (exosomes) | hsa-miR-199b-3p; hsa-miR-130a-3p; hsa-miR-24-3p | upregulated in ACAS progression group | - | |||

| Plaque stability | |||||||||

| Wang, et al. 2020 [70] | Linyi (China) | N= 73 stable N=87 vulnerable |

serum | hsa-miR-124 | upregulated in vulnerable plaque group | stable: fibrous and calcified plaque; vulnerable: lipid and mixed plaque | |||

| Huang, et al. 2020 [47] | Deyang (China) | N=96 stable N=84 vulnerable |

peripheral blood (PBMC) | hsa-miR-146a | upregulated in vulnerable paque | - | |||

| Yang, et al. 2018 [71] | Wuhan (China) | N=13 stable N=13 vulnerable |

plasma | hsa-miR-23a-5p; hsa-miR-320a; hsa-miR-2110; hsa-miR-134-5p | upregulated in vulnerable plaque | - | |||

| hsa-miR-4439 | downregulated in vulnerable plaque | ||||||||

| Huang, et al. 2020 [72] | Chongqing (China) | N=50 stable N=50 vulnerable |

tissue | hsa-miR-532-3p | downregulated in vulnerable plaque group | - | |||

| Zhang, et al. 2016[50] | Tianjin (China) | N= 156 stable N=21 vulnerable |

serum | hsa-miR-320b | downregulated in vulnerable plaque group | - | |||

| Vasuri, et al. 2019 [75] | Bologna (Italy) | N=19 calcific core N=18 protruding nodules |

tissue | hsa-miR-30a-5p; hsa-miR-30d | upregulated in protruding nodules | calcific core= heavy calcium deposits superimposed over necrotic lipid plaque cores. protruding nodules= concentric nodular calcifications eroding the arterial walls, regardless of the amount of lipids |

|||

| Katano, et al. 2018 [74] | Nagoya (Japan) | N= 5 highly calcified N=5 low calcified |

tissue | hsa-miR-4530; hsa-miR-133b; hsa-miR-1-3p | upregulated in low calcified plaques | Macroscopic hemorrhages were relatively more frequent in the low-calcified plaques compared with the high-calcified plaques. No difference found between the high- and low-calcified plaques concerning the degrees of stenoses. | |||

| Magenta, et al. 2018 [42] | Rome (Italy) | N=10 stable N=12 unstable |

tissue | hsa-miR-200c | upregulated in unstable plaque | - | |||

| Liu, et al. 2024 [49] | Shanghai (China) | N=12 stable N=11 unstable |

tissue | hsa-miR-127-3p | upregulated in unstable plaque | - | |||

| Wei, et al. 2019[76] | Shanghai (China) | N=10 stable N=10 unstable |

tissue | hsa-miR-330-5p | upregulated in unstable plaque | - | |||

| Eken, et al. 2017 [54] | Stockholm (Sweden) | N=10 stable N=7 unstable |

tissue | hsa-miR-210; hsa-miR-21 | downregulated in ruptured plaque | cap thickness below (unstable) or above (stable) 200 µm. | |||

| Zhu, et al. 2022 [48] | Hangzhou (China) | N=23 stable N=29 unstable |

serum | hsa-miR-126; hsa-miR-223 | downregulated in unstable plaque | - | |||

| Badacz, et al. 2018 [77] | Krakow (Poland) | N = 24 hypoechogenic N=47 moderately echogenic |

serum | hsa-miR-124-3p; hsa-miR-134-5p; hsa-miR-34a-5p; hsa-miR-375 | downregulated in hypoechogenic | hypoechogenic (or echolucent): soft, lipid rich (unstable) moderately echogenic: heterogeneous hyperechogenic: fibrotic and calcified (stable) | |||

| hsa-miR-133b | upregulated in hypoechogenic | ||||||||

| N=47 moderately echogenic N = 21 hyperechogenic |

hsa-miR-134-5p; hsa-miR-34a-5p; hsa-miR-375 | upregulated in hyperechogenic | |||||||

| hsa-miR-16-5p | downregulated in hyperechogenic | ||||||||

| N = 24 hypoechogenic N = 21 hyperechogenic |

hsa-miR-16-5p | upregulated in hyperechogenic | |||||||

| N= 64 non-ulcerated N= 28 ulcerated |

hsa-miR-1-3p; hsa-miR-16-5p | upregulated in ulcerated | |||||||

| Fasolo, et al. 2021 [56] | Stockholm (Sweden) | N=10 stable N=10 unstable |

tissue |

MIAT |

upregulated in unstable plaque |

- |

|||

| Huang, et al. 2020[53] | Wenzhou (China) | N=60 stable N=75 unstable |

serum | CCAT2 | upregulated in unstable plaque | - | |||

| hsa-miR-216b | downregulated in unstable plaque | ||||||||

| Bao, et al. 2021 [78] | Jilin (China) | N=5 stable N=5 unstable |

tissue | ENST00000430222; ENST00000602895; circ-013041; circ-025902 | upregulated in unstable plaque | - | |||

| ENST00000631338; MSTRG18183; circ-054182; circ-037511 | downregulated in unstable plaque | ||||||||

| Wen, et al. 2021[79] | Shenzhen (China) | N=22 stable N=20 unstable |

serum (exosomes) | circRNA-0006896 | upregulated in unstable plaque | - | |||

| Lin, et al. 2023 [80] | Shanghai (China) | N=3 stable N=3 unstable |

tissue | circ-0001523; circ-0008950; circ-0000571 | upregulated in unstable plaque | - | |||

|

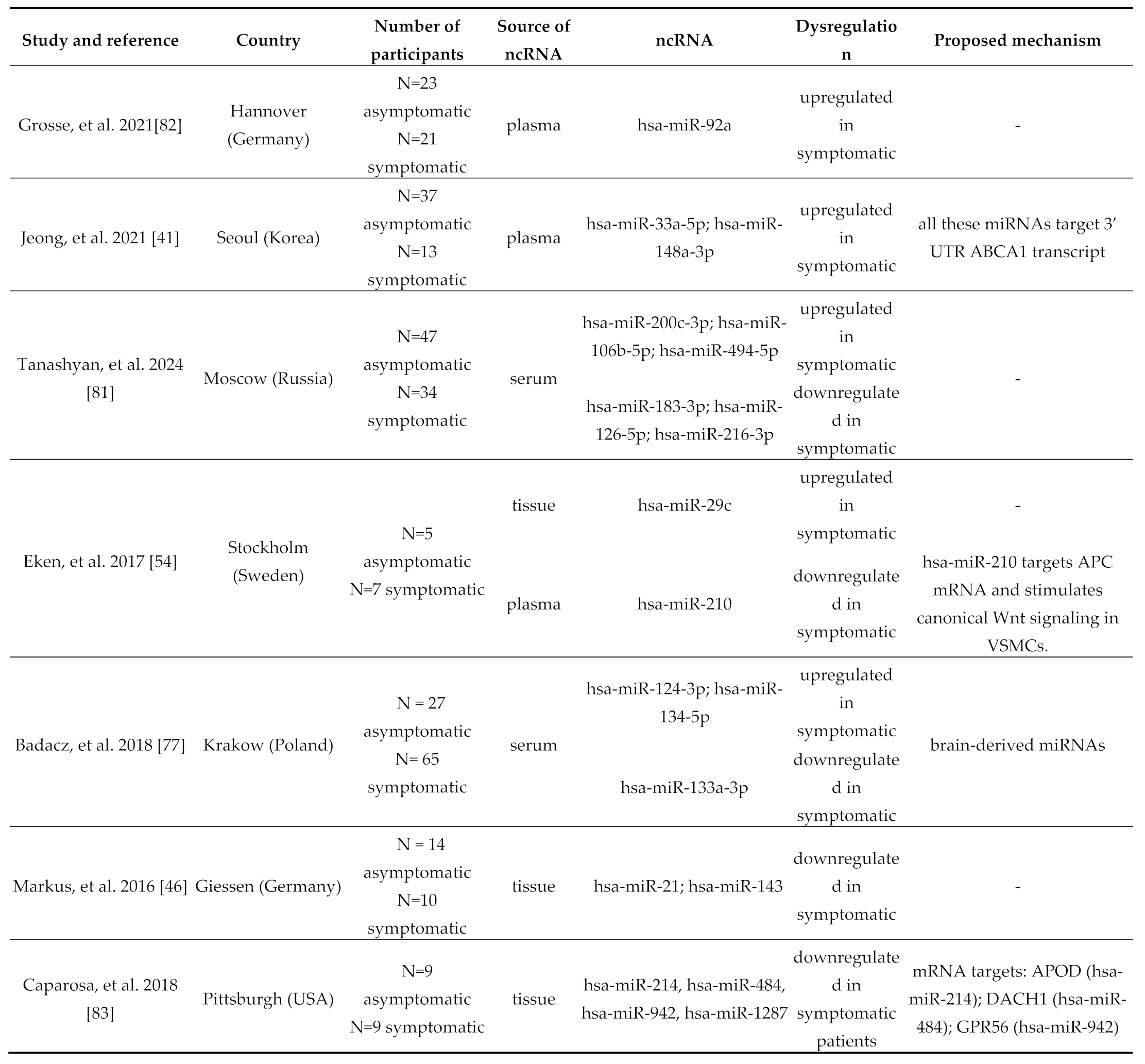

| Study and reference | Country | Number of participants | Source of ncRNA | ncRNA | Dysregulation | Proposed mechanism |

| Wang, et al. 2024 [24] | Luoyang (China) | N=18 without cerebral stroke N=22 with cerebral stroke |

tissue | hsa-miR-29c | upregulated in cerebral stroke group | VSMC proliferation |

| Tsai, et al. 2013 [45] | Kaohsiung and Taichung (Taiwan) | N= 157 control N= 167 stroke |

serum | hsa-miR-21 | upregulated in stroke group | hsa-miR-21 is involved in apoptosis inhibition and in VSMC proliferation targeting PDCD4, PTEN and PI3K/Akt genes |

| hsa-miR-221 | downregulated in stroke group | |||||

| Bazan, et al. 2015 [87] | New Orleans (USA) | N = 31 asymptomatic N=20 symptomatic N=25 cerebrovascular event |

tissue | hsa-miR-221; hsa-miR-222 | downregulated in cerebrovascular event (urgent) group | both miRNAs target p27Kip1, promoting VSMC proliferation |

| Bazan, et al. 2017 [88] | New Orleans (USA) | N=24 asymptomatic N= 17 cerebrovascular event |

serum | hsa-miR-221 | downregulated in cerebrovascular event (urgent) group | hsa-miR-221 is negatively regulated by circ-284. |

| Luque, et al. 2019[51] | Barcelona (Spain) | N=36 control N= 11 stroke |

serum | hsa-miR-638 | downregulated stroke patients | - |

| Wang, et al. 2023[85] | Jinan (China) | N= 67 control (no plaque) N= 73 plaque with low risk of cerebrovascular event N=85 plaque with medium-high risk of cerebrovascular event |

serum (exosomes) | circSCMH1 | downregulated in MH-risk compared to control and L-risk | presence of interaction sites within circSCMH1 and hsa-miR-874 sequence (bioinformatic analysis) |

| hsa-miR-874 | upregulated in MH-risk compared to control and L-risk | |||||

| Bazan, et al. 2017[88] | New Orleans (USA) | N=48 asymptomatic N= 41 cerebrovascular event |

serum | circR-284 | upregulated in urgent group | hsa-miR-221 is negatively regulated by circ-284. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).