1. Introduction

The World Health Organization (WHO) classifies grade II meningiomas as intermediate malignancy based on histology. However, these tumors exhibit heterogeneous clinical behavior that is not fully explained by conventional histological grading [

1,

2]. Some tumors progress or recur rapidly, while others remain dormant for years [

3]. This clinical unpredictability suggests that factors beyond standard morphological features significantly contribute to disease progression [

4,

5]. Consistent with these findings, recent studies have identified prognostic groups (MG1-MG4) that extend beyond histological grading [

6]. These studies have confirmed that the grade II meningioma patient population is not monolithic but rather comprises distinct biological archetypes. These archetypes include "immunogenic" (MG1) and "proliferative" (MG4) subtypes with different immune profiles and clinical outcomes. These data indicate that, at least in part, the variable disease progression observed in grade II meningioma patients may be related to underlying biological and immunological differences within the tumor microenvironment.

Within this framework, the balance between immune surveillance and immune evasion in the tumor immune microenvironment (TIME) is a plausible determinant of clinical heterogeneity [

7,

8]. This immunological balance is likely influenced by the origin of meningiomas in the immunologically active meninges [

9,

10]. Key TIME components, such as tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) and the B7-H3 immune checkpoint molecule, are recognized as regulators of tumor progression [

11,

12]. TAMs are the main immune infiltrate in meningiomas [

7], while B7-H3 is associated with tumor immune evasion and protumor functions [

13]. Accordingly, the concurrent evaluation of TAM density and B7-H3 expression may approximate the functional equilibrium between host immune defense and tumor escape mechanisms. Therefore, the two immune components may serve as surrogate indicators for immune-related variability in the clinical behavior of meningiomas.

A precise assessment of the impact of TIME on disease progression requires characterization of tumor growth kinetics beyond conventional volumetric analysis. Standard risk assessment based on absolute volume changes has important limitations because large tumors naturally exhibit greater absolute volume expansion than smaller ones, even when their growth rates are similar [

14,

15]. In contrast, the relative growth rate (RGR), derived from serial imaging, can address this limitation by quantifying tumor growth as a percentage increase per unit of time [

16,

17]. By normalizing growth to the baseline volume, RGR reduces confounding by initial physical dimensions. Thus, RGR provides a more appropriate metric for describing the intrinsic growth dynamics of the tumor and for exploring their relationship with the immune microenvironment.

To clarify the biological drivers, this study aimed to investigate the association between the density of Iba1-positive macrophages (defined as TAMs) and B7-H3-positive tumor cells, and tumor growth kinetics measured by RGR. We hypothesized that, reflecting the known biological heterogeneity, these immune components would segregate into distinct immunophenotypic clusters (e.g., "immune-hot" vs. "immune-cold") associated with differences in RGR, rather than showing a simple linear correlation. Such a combined assessment may provide a dynamic biological basis for more refined risk stratification in this patient population.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Ethical Approval

This single-center retrospective cohort study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical approval was obtained from the Institutional Review Board of Aichi Medical University (approval number: 24-895). Given that all data were collected as part of routine clinical care, individual informed consent was waived; an opt-out notice detailing the study was made available on the hospital website. All personal identifiers were removed before analysis.

2.2. Patient Selection

We reviewed the clinical and radiological records of 18 consecutive patients who underwent surgical resection for WHO grade II intracranial meningiomas between January 2014 and December 2023 [

18]. We included patients with histopathologically confirmed WHO grade II meningiomas and suitable contrast-enhanced T1-weighted magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) data from at least two time points prior to treatment for volumetric analysis. Patients with neurofibromatosis type 2, other tumor-predisposition syndromes, spinal or extracranial tumors, or multifocal disease were excluded. Consequently, three patients were excluded due to incomplete imaging data. The remaining 15 patients were included in the final analysis.

2.3. Volumetric Analysis and Calculation of Growth Metrics

Contrast-enhanced T1-weighted MRI DICOM datasets from two time points were imported into an image-processing workstation (Zaio; Ziosoft, Tokyo, Japan). All examinations used thin-slice protocols with a slice thickness of ≤1.5 mm. The median interscan interval was 63.0 days (range, 33-1,815 days). An experienced neurosurgeon, blinded to the clinical outcomes, manually outlined tumor borders on every axial slice using a freehand tool for each scan pair. Volumes were computed by slice summation:

where

is the lesion area on slice

,

is slice thickness, and

is the inter-slice gap. Two prespecified growth metrics were derived using the interval in months:

Relative growth rate (RGR, %/month) was calculated as

Monthly volume change (MVC, cm

3/month) was calculated as

The mean value was used to analyze each volume, which was measured twice.

2.4. Histological Processing and Immunohistochemistry

This procedure was conducted according to the previous studies [

18,

19,

20]. Briefly, formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded meningioma tissue was sectioned at 4 µm and mounted on silane-coated slides. One section was stained with hematoxylin and eosin for morphological assessment. Adjacent sections underwent multicolor immunohistochemistry using the following primary monoclonal antibodies (mAbs): anti-Iba1 (clone EPR16589; Abcam), anti-CD4 (clone EPR6855; Abcam), and anti-B7-H3/CD276 (clone EPR20115; Abcam). The Histofine Simple Stain system (Nichirei, Tokyo, Japan) was used for detection, with distinct chromogenic substrates applied to each target according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The substrates were diaminobenzidine (DAB; Nichirei) for CD4 (brown), HistoGreen (Cosmo Bio, Tokyo, Japan) for B7-H3 (light green), and First Red II (Nichirei) for Iba1 (red). Areas of overlap between the Iba1 and B7-H3 signals appeared dark brown in the composite staining. All sections were counterstained with hematoxylin.

2.5. Image Analysis

This procedure was conducted according to the previous studies [

18,

19,

20]. Briefly, whole-slide images were obtained at 20× magnification using a NanoZoomer-SQ system (Hamamatsu Photonics, Hamamatsu, Japan). The digital images were then imported into QuPath software (version 0.6.0) for analysis [

21]. Tumor regions were outlined using automated pixel classification. Cell detection algorithms were then used to categorize cells into the following groups: tumor cells, CD4-positive T cells, TAMs, B7-H3-positive tumor cells, and others. Then, cell classification algorithms were applied to all digital slides to ensure consistent classification across cases. A quantitative analysis was conducted encompassing the measurement of the tumor area and characterization of the classified cells, including their spatial distribution and morphometric parameters. Cell densities were quantified as the number of positive cells per square millimeter of the tumor area.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

This procedure was conducted according to the previous studies [

18,

19,

20]. Statistical analyses were performed using EZR (version 1.68; Saitama Medical Center, Jichi Medical University, Saitama, Japan). The primary outcome examined the association between TAM density and RGR. The secondary outcomes examined the relationships between B7-H3-positive tumor cell density, total tumor cell density, and CD4-positive T cell density in relation to RGR and MVC. Continuous variables are reported as medians with ranges. Group comparisons were performed using the Mann–Whitney U test, and associations were assessed using Spearman’s rank correlation coefficients. Statistical significance was defined as a two-sided

P < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Clinical Characteristics of the Patient Cohort

We summarized the clinical characteristics of the 15 patients who underwent resection for WHO grade II meningiomas (

Table 1). The median RGR, used as a proxy for proliferative activity, was 4.5% per month from serial preoperative MRI. The median MVC, reflecting absolute volume increase, was 1.51 cm

3 per month. The median postoperative follow-up duration was 36 months (range, 11–136 months). No cases of recurrence were identified within this cohort during this period.

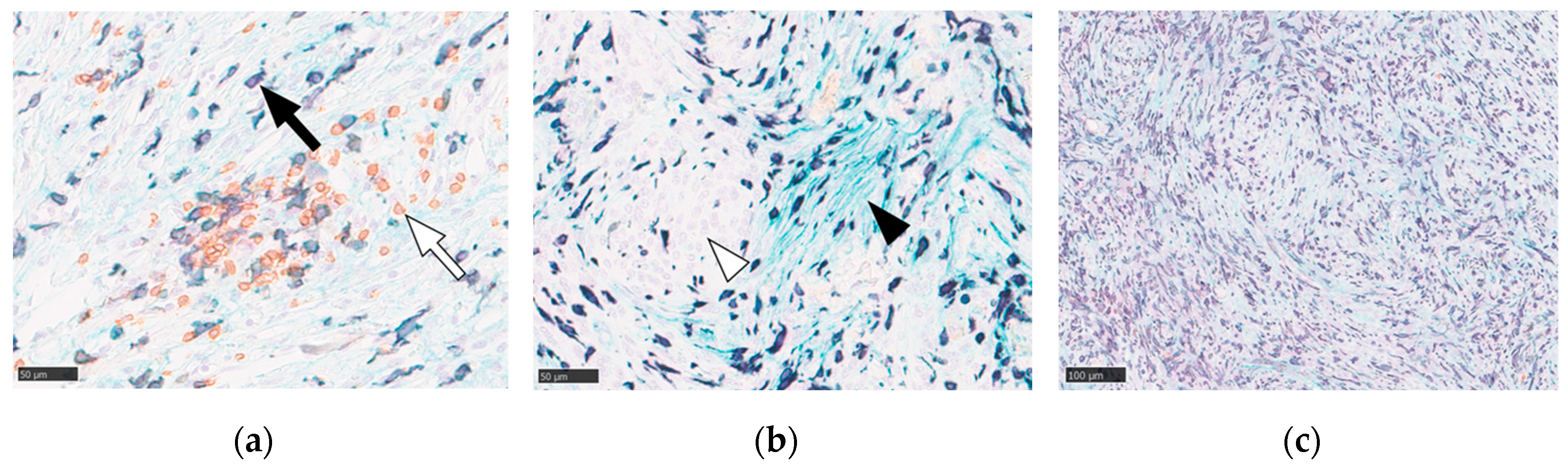

3.2. Immunohistochemical Characterization of the Tumor Immune Microenvironment

We subsequently characterized the TIME of WHO grade II meningiomas using multicolor immunohistochemistry and digital image analysis. This analysis confirmed the presence of both Iba1-positive TAMs and CD4-positive helper T cells distributed throughout the tumor parenchyma (

Figure 1a). B7-H3 immunoreactivity was specifically localized to the cell membranes of tumor cells. Notably, the expression of B7-H3-positive tumor cells was heterogeneous within the tumors, with some neoplastic cells exhibiting distinct membrane staining and others being negative (

Figure 1b). The density of immune cell infiltration varied significantly among the cases, with some tumors displaying dense macrophage accumulation (

Figure 1c).

3.3. Association of Immune Marker Densities with Tumor Growth Rate

We then examined the quantitative relationship between these immunodistinct cell populations and tumor growth kinetics (

Table 2). First, we assessed the simple linear correlations between immune cell density and growth metrics. This analysis revealed a weak, non-significant inverse correlation between TAM density and RGR (Spearman’s

R = -0.36,

P = 0.187) and a weak, non-significant positive correlation between B7-H3-positive tumor cell density and RGR (Spearman’s

R = 0.352,

P = 0.199). No significant correlations were identified between any of the immune markers and the absolute growth metric, MVC.

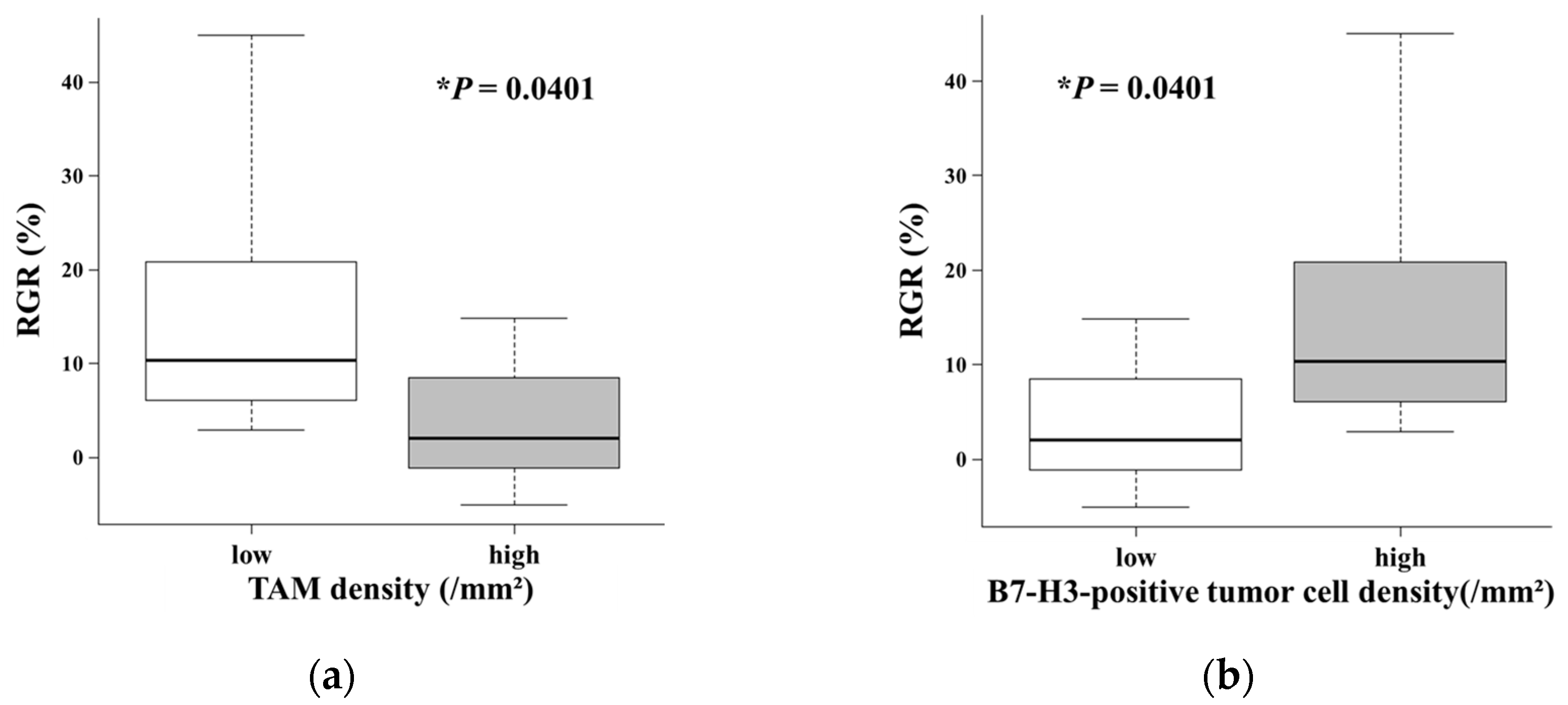

Due to the absence of a robust linear relationship, we stratified the patients into "low" and "high" density groups based on the median value for each cell density (TAM density: 2,053.3 cells/mm

2; B7-H3-positive tumor cell density: 1,828.4 cells/mm

2) to explore potential nonlinear associations. Comparative analyses between these groups revealed significant differences in the results. Tumors with low TAM density exhibited a significantly higher RGR than those with high TAM density (

P = 0.0401;

Figure 2a). Conversely, patients with a high density of B7-H3-positive tumor cells showed a significantly higher RGR than those with a low density of B7-H3-positive tumor cells (

P = 0.0401;

Figure 2b).

3.4. Inverse Relationship Between TAM Infiltration and B7-H3 Expression

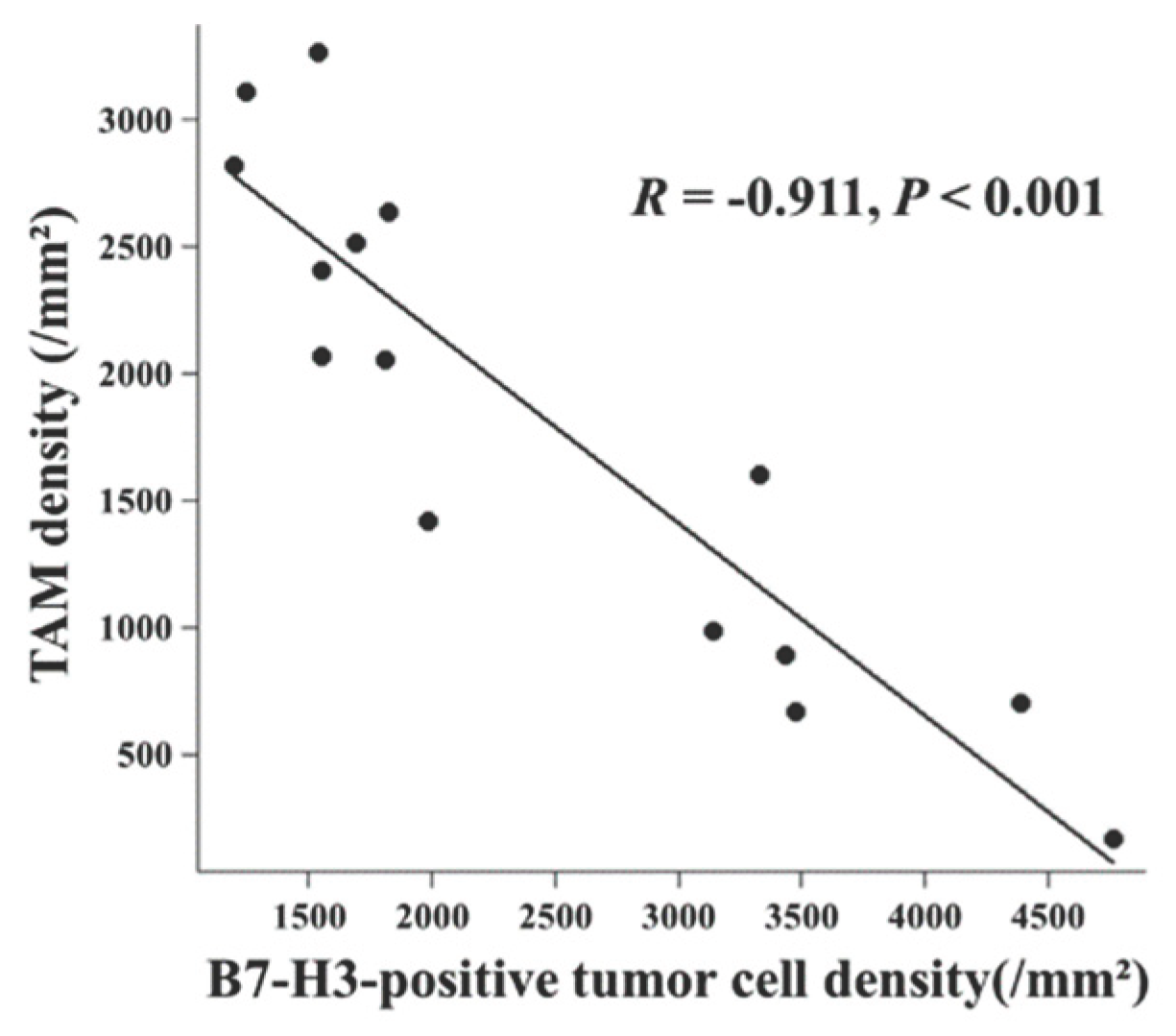

We investigated the relationship between these key cellular components within the TIME. We found a significant inverse correlation between the density of Iba1-positive TAMs and that of B7-H3-positive tumor cells (

Figure 3,

R = -0.911,

P < 0.001). In summary, the inverse correlation between TAM infiltration and B7-H3-positive tumor cells suggested a polarized immune balance within the microenvironment. This mutual exclusivity suggests a polarization of the meningioma TIME, defining two distinct immunophenotypes with contrasting tumor growth kinetics.

4. Discussion

The central finding of this study is that distinct immunophenotypes, defined by the density of TAMs and B7-H3-positive tumor cells, appear to be associated with the intrinsic growth kinetics of WHO grade II meningiomas. Despite the limited cohort size, we observed that tumors exhibiting an “immune-cold” phenotype, characterized by low TAM density and high B7-H3-positive tumor cell density, demonstrated significantly higher RGR compared with their “immune-hot” counterparts (

Figure 2). Furthermore, the significant inverse relationship identified between TAMs and B7-H3-positive tumor cells (

Figure 3) suggests that these tumors may segregate into two biologically distinct archetypes. These observations imply that the “Low TAM/High B7-H3-positive tumor cell” profile may serve as a potential indicator of aggressive tumor behavior, warranting further validation.

Our findings regarding the relationship between immune patterns and tumor growth rates aligns with the recently reported molecular classification of WHO grade II meningiomas [

6]. These genomic studies have identified four groups (MG1-MG4), which include an “immunogenic” subtype (MG1) and an aggressive “proliferative” subtype (MG4). Our "high TAM" group exhibited slower growth (

Figure 2a) and clinical behavior similar to the "immunogenic" MG1 subtype, which is characterized by dense immune infiltration and a favorable outcome. In contrast, our "high B7-H3-positive tumor cell" group exhibited rapid growth (

Figure 2b) similar to the "proliferative" MG4 subtype, which has been described as an "immune-cold" type. While these molecular studies defined the broad immune landscape, they did not specifically evaluate B7-H3 expression as a specific driver of rapid growth. Our findings extend this classification by identifying B7-H3 expression on tumor cells as a key feature of the "immune-cold" phenotype that directly correlates with accelerated RGR. This suggests that B7-H3 expression may have tumor-intrinsic functions beyond its immunological role and contribute to tumor progression by enhancing migration and invasion as observed in other malignancies [

22,

23,

24]. Therefore, our data suggest that the density of B7-H3-positive tumor cells may increase in rapidly growing tumors within this "immune-cold" environment.

The significant inverse correlation observed in this study (R = -0.911;

Figure 3) suggests that WHO grade II meningiomas may segregate into distinct biological archetypes rather than forming a continuous spectrum. This finding stands in contrast to reports in other solid malignancies, where B7-H3 expression often correlates positively with TAM density due to its role in promoting M2 macrophage polarization via STAT3-dependent CCL2-CCR2 signaling [

25,

26]. The divergence observed in our cohort, specifically the "Low TAM/High B7-H3-positive tumor cell” phenotype, implies that the biological function of B7-H3 in these meningiomas may differ from the classical immunosuppressive paradigm. In the absence of TAM infiltration, the high RGR observed in this group raises the possibility that non-immunological, tumor-intrinsic proliferative effects drive tumor growth [

27,

28]. Therefore, these tumors appear to rely less on macrophage-mediated immune evasion and potentially more on intrinsic oncogenic signaling driven by molecules such as B7-H3.

The key methodological finding of our study is the superiority of RGR over MVC as a biologically relevant endpoint (

Table 2). Our results demonstrate that the immunophenotype correlates significantly with RGR, but not with MVC. This strongly suggests that RGR, which normalizes for baseline tumor size, is a more sensitive metric for assessing the TIME's impact on tumor growth dynamics [

29]. This implies a deeper biological significance: the TIME likely modulates the tumor's intrinsic proliferative potential (a rate), which is captured by RGR, rather than the absolute volume increase (an amount), which is captured by MVC and confounded by initial tumor size [

16,

17,

29]. Therefore, RGR represents the biologically appropriate metric for capturing the true growth dynamics driven by the immune microenvironment.

This study has several limitations that necessitate a cautious interpretation. First, the very small sample size (n=15) severely limits statistical power and the generalizability of our findings; the associations identified, while significant, require validation in larger cohorts. Second, our interpretation linking these immunophenotypes to the Nassiri et al. subtypes is entirely hypothesis-generating [

6], as our cohort was not molecularly subtyped. Third, the wide heterogeneity in imaging intervals (range, 33-1,815 days) may introduce variability in RGR calculations. While RGR is designed to adjust for observation duration under the assumption of exponential growth [

16,

17], it may not perfectly capture the dynamics of tumors exhibiting linear or Gompertzian growth patterns. Shorter intervals are more susceptible to measurement error, while very long intervals may not adequately capture steady-state proliferation dynamics. Finally, the use of a pan-macrophage marker (Iba1) precluded functional differentiation between potentially anti-tumoral (M1) and pro-tumoral (M2) macrophage populations, limiting a deeper functional characterization of the immune microenvironment [

30]. Despite these limitations, our findings provide a compelling rationale for further investigation into the immunokinetic properties of meningiomas.

5. Conclusions

This study identifies an immunophenotype in WHO grade II meningiomas characterized by a paucity of TAMs and an elevation of B7-H3-positive tumor cell density, which is associated with rapid tumor proliferation. Our data indicate that B7-H3-positive tumor cells may play a role in the aggressive behavior of these tumors, independent of macrophage-mediated immunosuppression. Concurrent evaluation of these components offers a potent strategy for risk stratification and highlights high B7-H3-positive tumor cells as a potential therapeutic target.

Author Contributions

EI, MO, SK, and MF conceptualized the project. EI, MO, SK, and TN acquired the funding. MO and MF supervised the project and conducted the project administration. EI, TI, and TW provided resources. EI, MO, and MF developed the methodology. EI, MY, and TI acquired raw data. EI, MO, and MF carried out formal analyses. EI wrote the original draft. MO, SK, TN, and MF edited the manuscript. All the Authors have reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI (23K15677 to SK, 24K10381 to TN, 24K12219 to EI, and 25K12376 to MO).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Aichi Medical University (approval number 24-895).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all the patients included in this case report, ensuring adherence to ethical guidelines.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are not publicly available because of institutional policy and the risk of compromising patient privacy in this small cohort. De-identified data may be made available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request and with permission from the Institutional Review Board of Aichi Medical University.

Acknowledgments

They also thank Aichi Pathological Diagnostic Clinic (aichi-path-cl.com) for the immunohistochemical (IHC) staining.

Conflicts of Interest

The Authors declare no conflicts of interest in relation to this study.

Artificial Intelligence (AI) Disclosure: During the preparation of this manuscript, Gemini 3.0 pro, Perplexity, and DeepL were used solely for language editing and stylistic improvements in select paragraphs.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| DAB |

Diaminobenzidine |

| DWI |

Diffusion-weighted imaging |

| IHC |

Immunohistochemistry |

| mAb |

Monoclonal antibody |

| MRI |

Magnetic resonance imaging |

| MVC |

Monthly volume change |

| RGR |

Relative growth rate |

| TAM |

Tumor-associated macrophage |

| TIME |

Tumor immune microenvironment |

| WHO |

World Health Organization |

References

- Durand, A; Labrousse, F; Jouvet, A; Bauchet, L; Kalamaridès, M; Menei, P; Deruty, R; Moreau, JJ; Fèvre-Montange, M; Guyotat, J. WHO grade II and III meningiomas: a study of prognostic factors. J Neurooncol 2009, 95, 367–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louis, DN; Perry, A; Wesseling, P; Brat, DJ; Cree, IA; Figarella-Branger, D; Hawkins, C; Ng, HK; Pfister, SM; Reifenberger, G; Soffietti, R; von Deimling, A; Ellison, DW. The 2021 WHO Classification of Tumors of the Central Nervous System: a summary. Neuro Oncol 2021, 23, 1231–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamada, S; Hirayama, R; Iwata, T; Kuroda, H; Nakagawa, T; Takenaka, T; Kijima, N; Okita, Y; Kagawa, N; Kishima, H. Growth risk classification and typical growth speed of convexity, parasagittal, and falx meningiomas: a retrospective cohort study. J Neurosurg 2023, 138, 1235–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budohoski, KP; Clerkin, J; Millward, CP; O'Halloran, PJ; Waqar, M; Looby, S; Young, AMH; Guilfoyle, MR; Fitzroll, D; Devadass, A; Allinson, K; Farrell, M; Javadpour, M; Jenkinson, MD; Santarius, T; Kirollos, RW. Predictors of early progression of surgically treated atypical meningiomas. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2018, 160, 1813–1822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, B; Desai, R; Pugazenthi, S; Butt, OH; Huang, J; Kim, AH. Identification and Management of Aggressive Meningiomas. Front Oncol 2022, 12, 851758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nassiri, F; Liu, J; Patil, V; Mamatjan, Y; Wang, JZ; Hugh-White, R; Macklin, AM; Khan, S; Singh, O; Karimi, S; Corona, RI; Liu, LY; Chen, CY; Chakravarthy, A; Wei, Q; Mehani, B; Suppiah, S; Gao, A; Workewych, AM; Tabatabai, G; Boutros, PC; Bader, GD; de Carvalho, DD; Kislinger, T; Aldape, K; Zadeh, G. A clinically applicable integrative molecular classification of meningiomas. Nature 2021, 597, 119–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Proctor, DT; Huang, J; Lama, S; Albakr, A; Van Marle, G; Sutherland, GR. Tumor-associated macrophage infiltration in meningioma. Neurooncol Adv 2019, 1, vdz018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garzon-Muvdi, T; Bailey, DD; Pernik, MN; Pan, E. Basis for Immunotherapy for Treatment of Meningiomas. Front Neurol 2020, 11, 945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ransohoff, RM; Engelhardt, B. The anatomical and cellular basis of immune surveillance in the central nervous system. Nat Rev Immunol 2012, 12, 623–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Louveau, A; Smirnov, I; Keyes, TJ; Eccles, JD; Rouhani, SJ; Peske, JD; Derecki, NC; Castle, D; Mandell, JW; Lee, KS; Harris, TH; Kipnis, J. Structural and functional features of central nervous system lymphatic vessels. Nature 2015, 523, 337–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quail, DF; Joyce, JA. Microenvironmental regulation of tumor progression and metastasis. Nat Med 2013, 19, 1423–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, X; Chang, M; Wang, Y; Xing, B; Ma, W. B7-H3 in Brain Malignancies: Immunology and Immunotherapy. Int J Biol Sci 2023, 19, 3762–3780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, YH; Martin-Orozco, N; Zheng, P; Li, J; Zhang, P; Tan, H; Park, HJ; Jeong, M; Chang, SH; Kim, BS; Xiong, W; Zang, W; Guo, L; Liu, Y; Dong, ZJ; Overwijk, WW; Hwu, P; Yi, Q; Kwak, L; Yang, Z; Mak, TW; Li, W; Radvanyi, LG; Ni, L; Liu, D; Dong, C. Inhibition of the B7-H3 immune checkpoint limits tumor growth by enhancing cytotoxic lymphocyte function. Cell Res 2017, 27, 1034–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oya, S; Kim, SH; Sade, B; Lee, JH. The natural history of intracranial meningiomas. J Neurosurg 2011, 114, 1250–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islim, AI; Mohan, M; Moon, RDC; Srikandarajah, N; Mills, SJ; Brodbelt, AR; Jenkinson, MD. Incidental intracranial meningiomas: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prognostic factors and outcomes. J Neurooncol 2019, 142, 211–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashimoto, N; Rabo, CS; Okita, Y; Kinoshita, M; Kagawa, N; Fujimoto, Y; Morii, E; Kishima, H; Maruno, M; Kato, A; Yoshimine, T. Slower growth of skull base meningiomas compared with non-skull base meningiomas based on volumetric and biological studies. J Neurosurg 2012, 116, 574–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakasu, S; Nakasu, Y. Natural History of Meningiomas: Review with Meta-analyses. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo) 2020, 60, 109–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inomo, T; Ohno, M; Nagasaka, T; Kuramitsu, S; Ito, E; Watanabe, T; Fujita, M. Characterization of Tumor Immune Microenvironment in Meningiomas: Correlation of Tumor-infiltrating Lymphocyte Aggregates With Tumor Grade. Anticancer Res 2025, 45, 3487–3496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nohira, S; Kuramitsu, S; Ohno, M; Fujita, M; Yamashita, K; Nagasaka, T; Haimoto, S; Sakakura, N; Matsushita, H; Saito, R. Tertiary Lymphoid Structures in Brain Metastases of Lung Cancer: Prognostic Significance and Correlation With Clinical Outcomes. Anticancer Res 2024, 44, 3615–3621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohno, M; Kuramitsu, S; Yamashita, K; Nagasaka, T; Haimoto, S; Fujita, M. Tumor-Infiltrating B Cells and Tissue-Resident Memory T Cells as Prognostic Indicators in Brain Metastases Derived from Gastrointestinal Cancers. Cancers (Basel) 2024, 16, 3765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bankhead, P; Loughrey, MB; Fernández, JA; Dombrowski, Y; McArt, DG; Dunne, PD; McQuaid, S; Gray, RT; Murray, LJ; Coleman, HG; James, JA; Salto-Tellez, M; Hamilton, PW. QuPath: Open source software for digital pathology image analysis. Sci Rep 2017, 7, 16878. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, X; Li, DC; Zhu, XG; Gan, WJ; Li, Z; Xiong, F; Zhang, ZX; Zhang, GB; Zhang, XG; Zhao, H. B7-H3 overexpression in pancreatic cancer promotes tumor progression. Int J Mol Med 2013, 31, 283–91. [Google Scholar]

- Picarda, E; Ohaegbulam, KC; Zang, X. Molecular Pathways: Targeting B7-H3 (CD276) for Human Cancer Immunotherapy. Clin Cancer Res 2016, 22, 3425–3431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutton, MN; Glazer, SE; Muzzioli, R; Yang, P; Gammon, ST; Piwnica-Worms, D. Dimerization of the 4Ig isoform of B7-H3 in tumor cells mediates enhanced proliferation and tumorigenic signaling. Commun Biol 2024, 7, 21. [Google Scholar]

- Miyamoto, T; Murakami, R; Hamanishi, J; Tanigaki, K; Hosoe, Y; Mise, N; Takamatsu, S; Mise, Y; Ukita, M; Taki, M; Yamanoi, K; Horikawa, N; Abiko, K; Yamaguchi, K; Baba, T; Matsumura, N; Mandai, M. B7-H3 Suppresses Antitumor Immunity via the CCL2-CCR2-M2 Macrophage Axis and Contributes to Ovarian Cancer Progression. Cancer Immunol Res 2022, 10, 56–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luan, S; Zhao, Y; Yu, Y; Xu, J; Xu, J; Ren, T; Tang, X; Xie, L. The relevance of B7-H3 and tumor-associated macrophages in the tumor immune microenvironment of solid tumors: recent advances. Am J Transl Res 2025, 17, 2835–2849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, WT; Jin, WL. B7-H3/CD276: An Emerging Cancer Immunotherapy. Front Immunol 2021, 12, 701006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Getu, AA; Tigabu, A; Zhou, M; Lu, J; Fodstad, Ø; Tan, M. New frontiers in immune checkpoint B7-H3 (CD276) research and drug development. Mol Cancer 2023, 22, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fountain, DM; Soon, WC; Matys, T; Guilfoyle, MR; Kirollos, R; Santarius, T. Volumetric growth rates of meningioma and its correlation with histological diagnosis and clinical outcome: a systematic review. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2017, 159, 435–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurga, AM; Paleczna, M; Kuter, KZ. Overview of General and Discriminating Markers of Differential Microglia Phenotypes. Front Cell Neurosci 2020, 14, 198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).