Submitted:

29 December 2025

Posted:

30 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

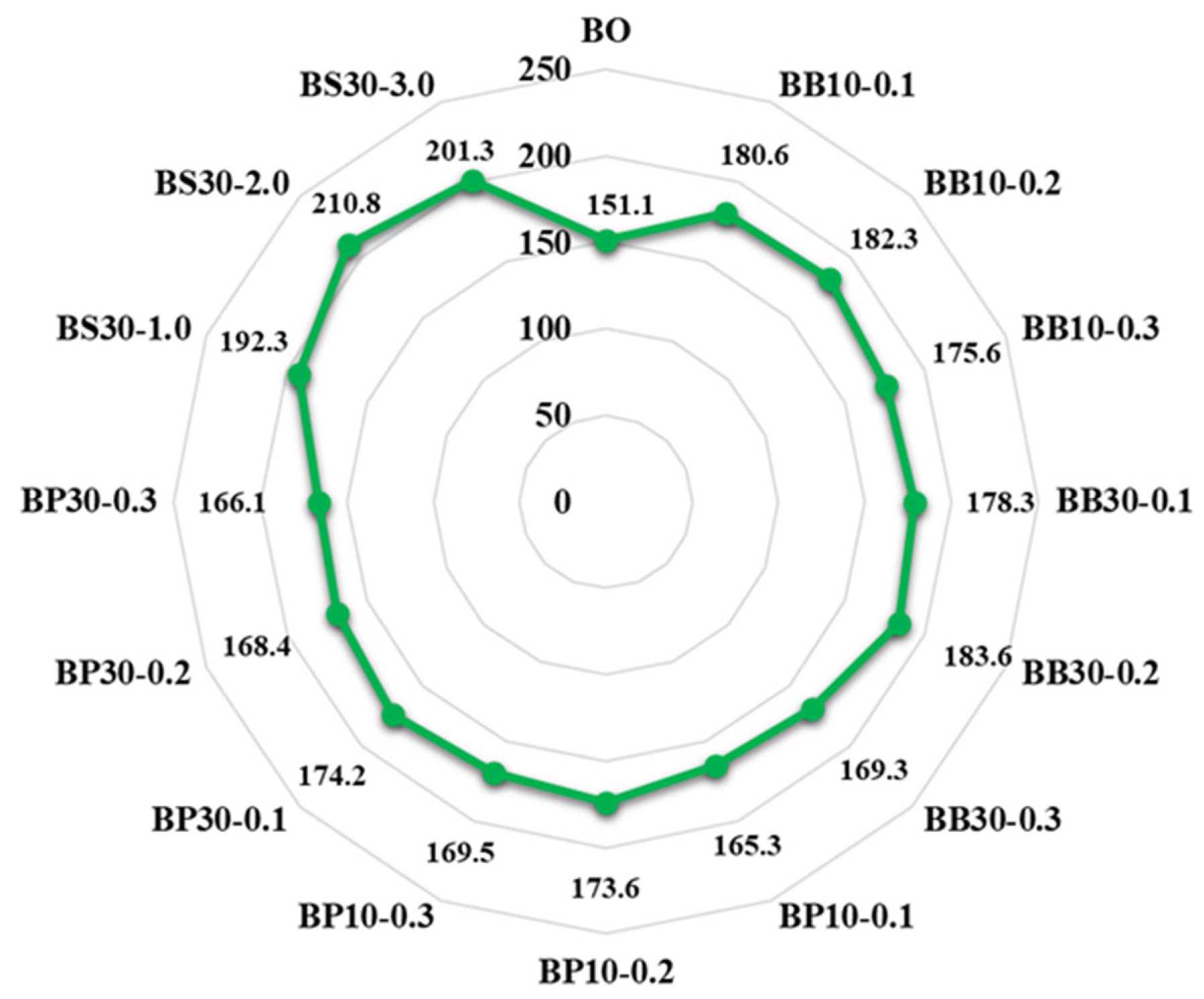

2.1. Construction of the Testing Samples

2.2. Materials

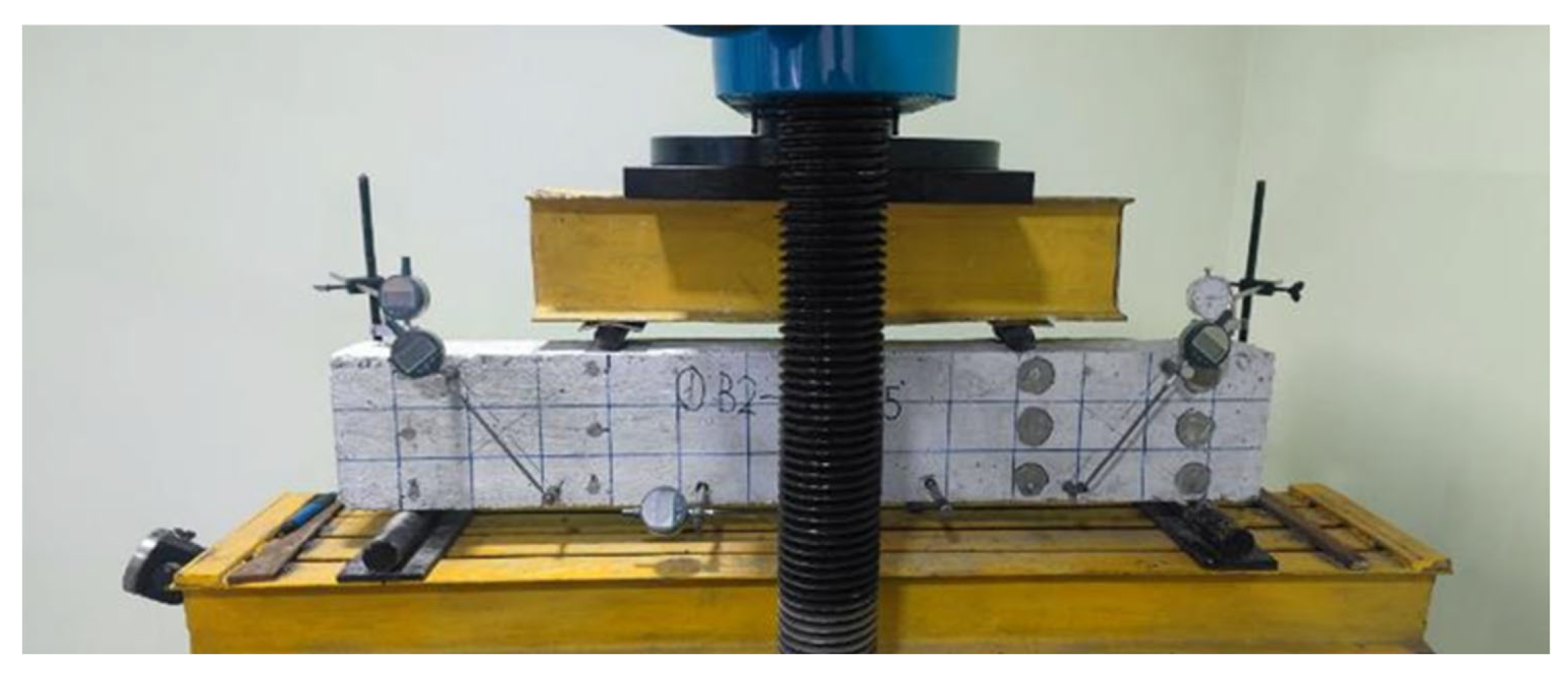

2.3. Testing Methodology

3. Results

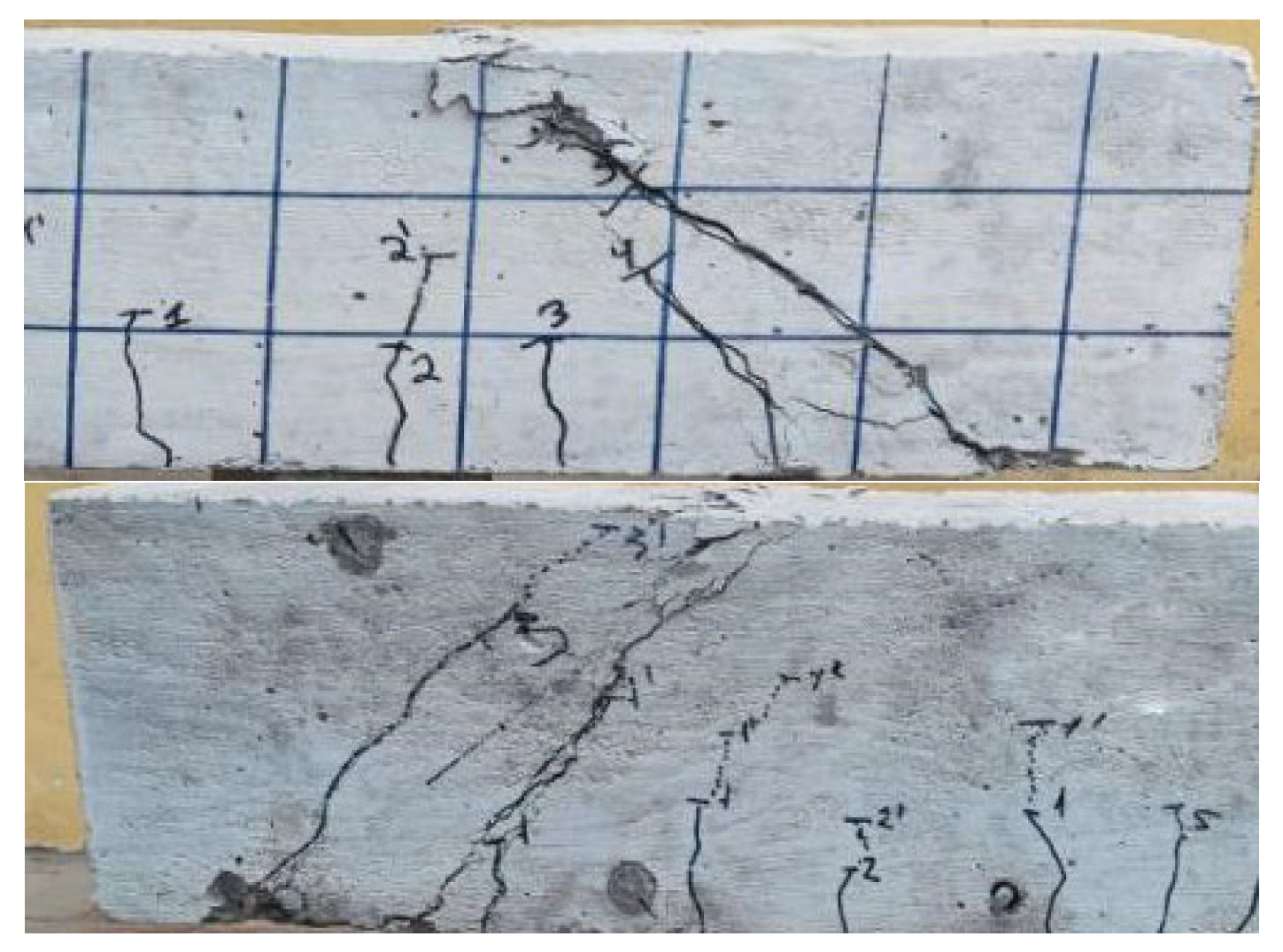

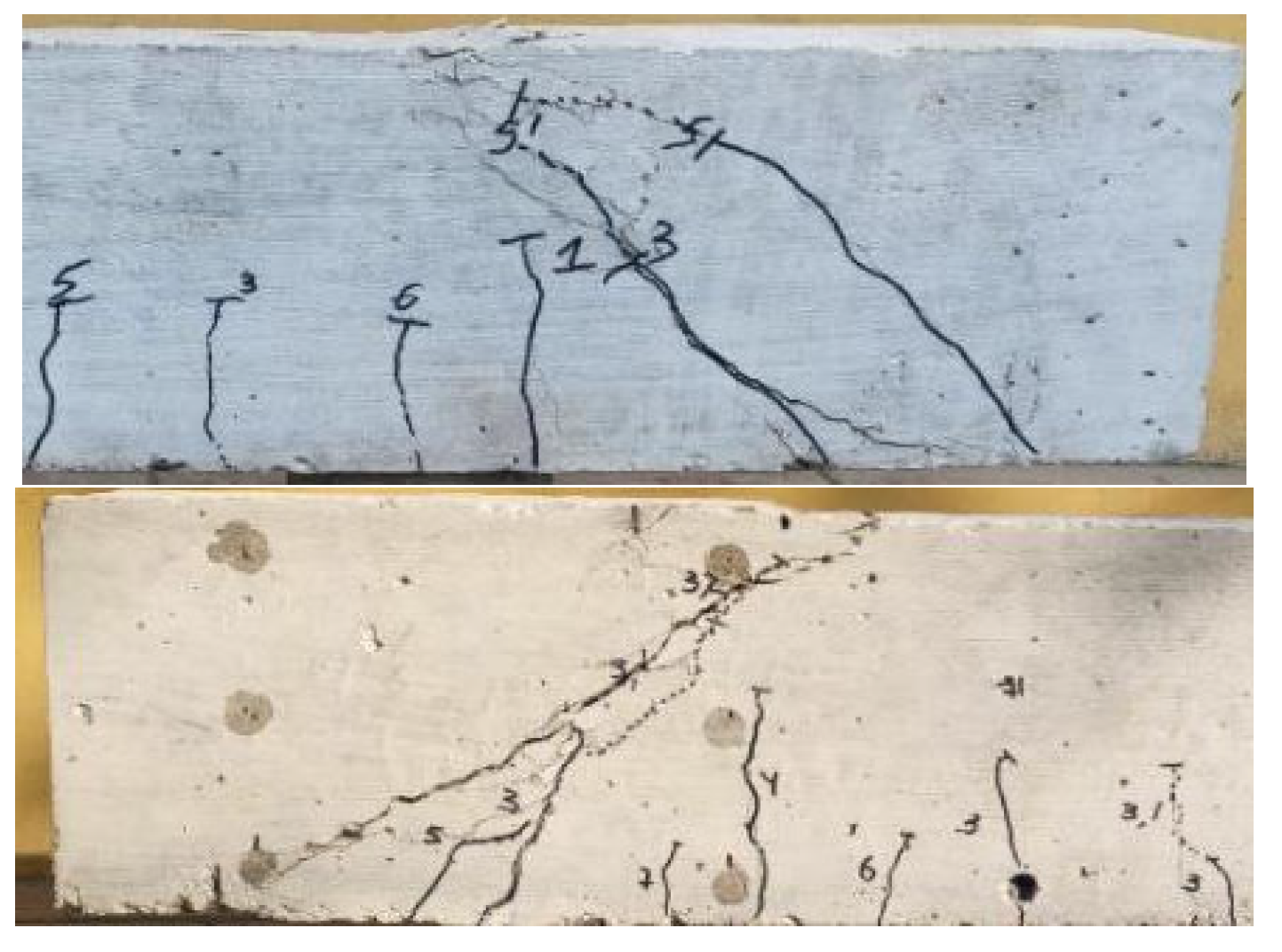

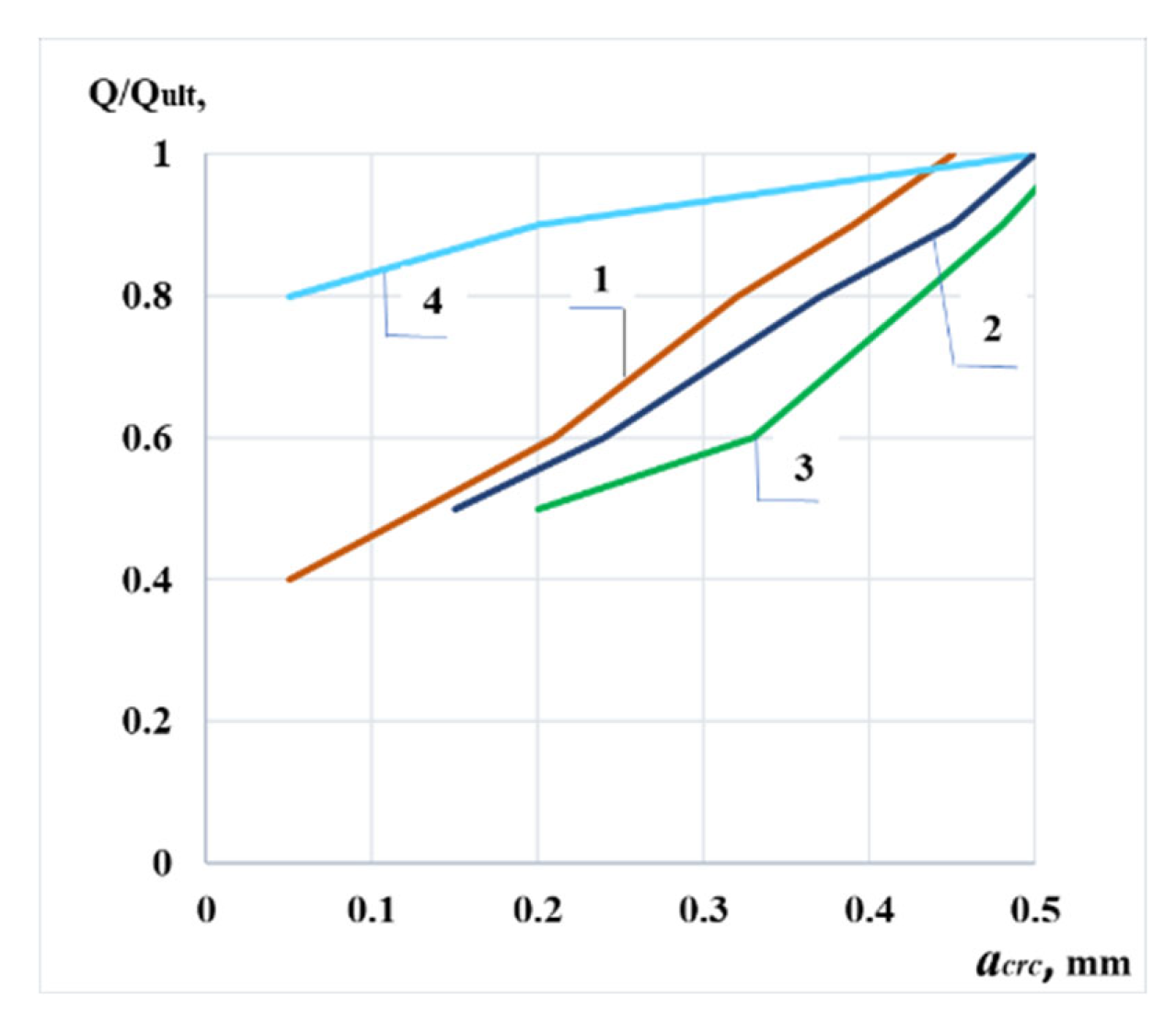

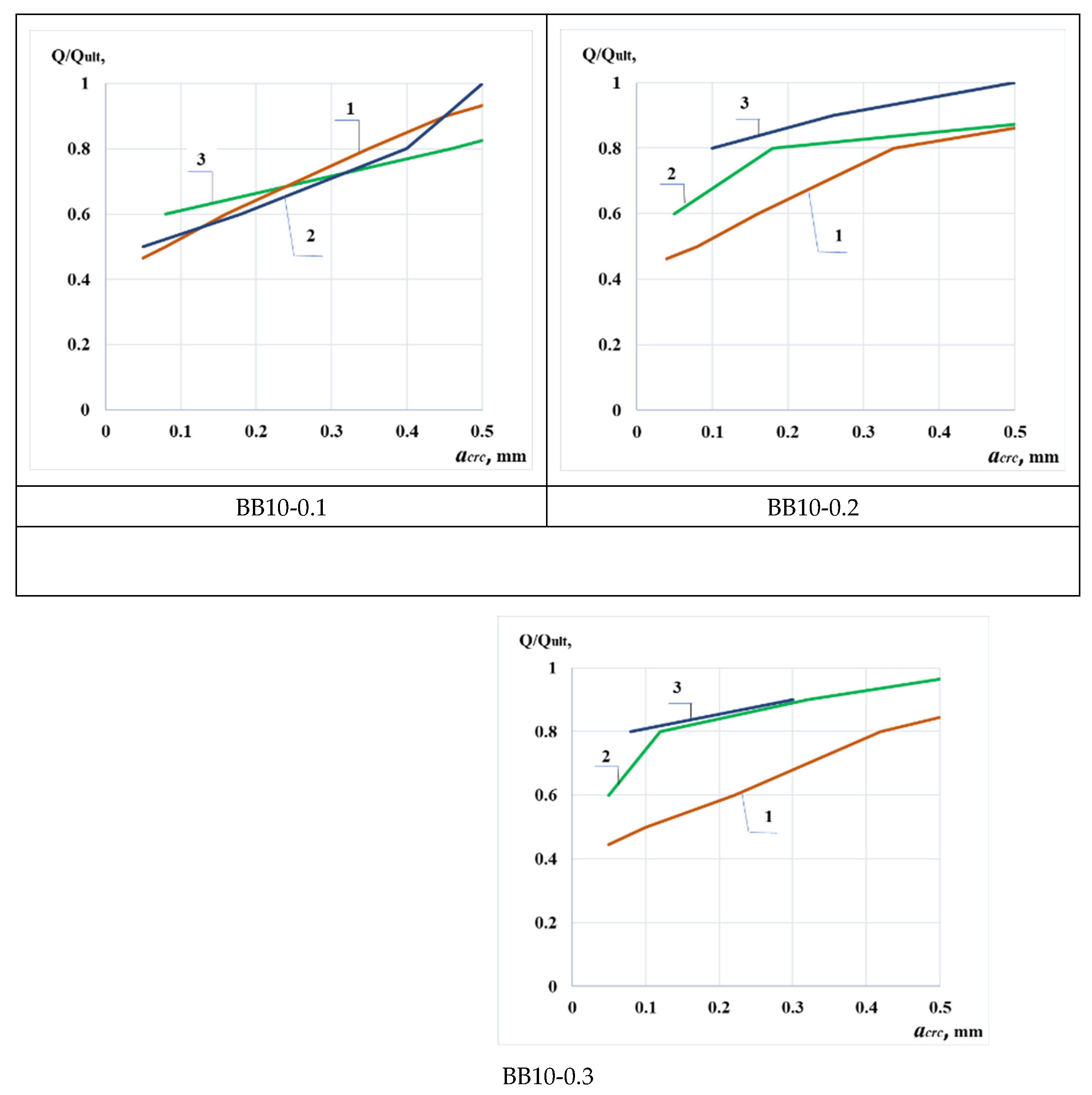

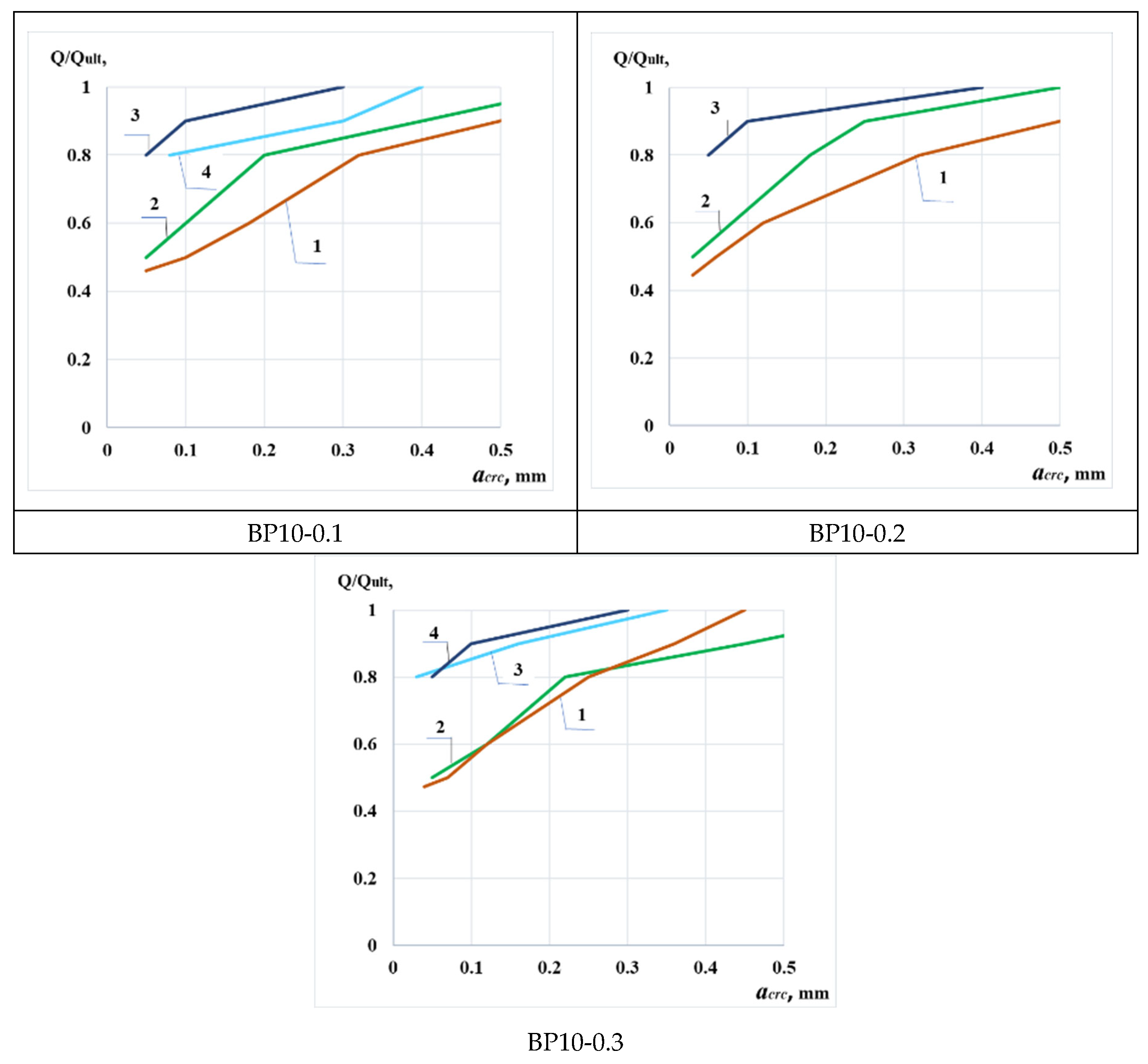

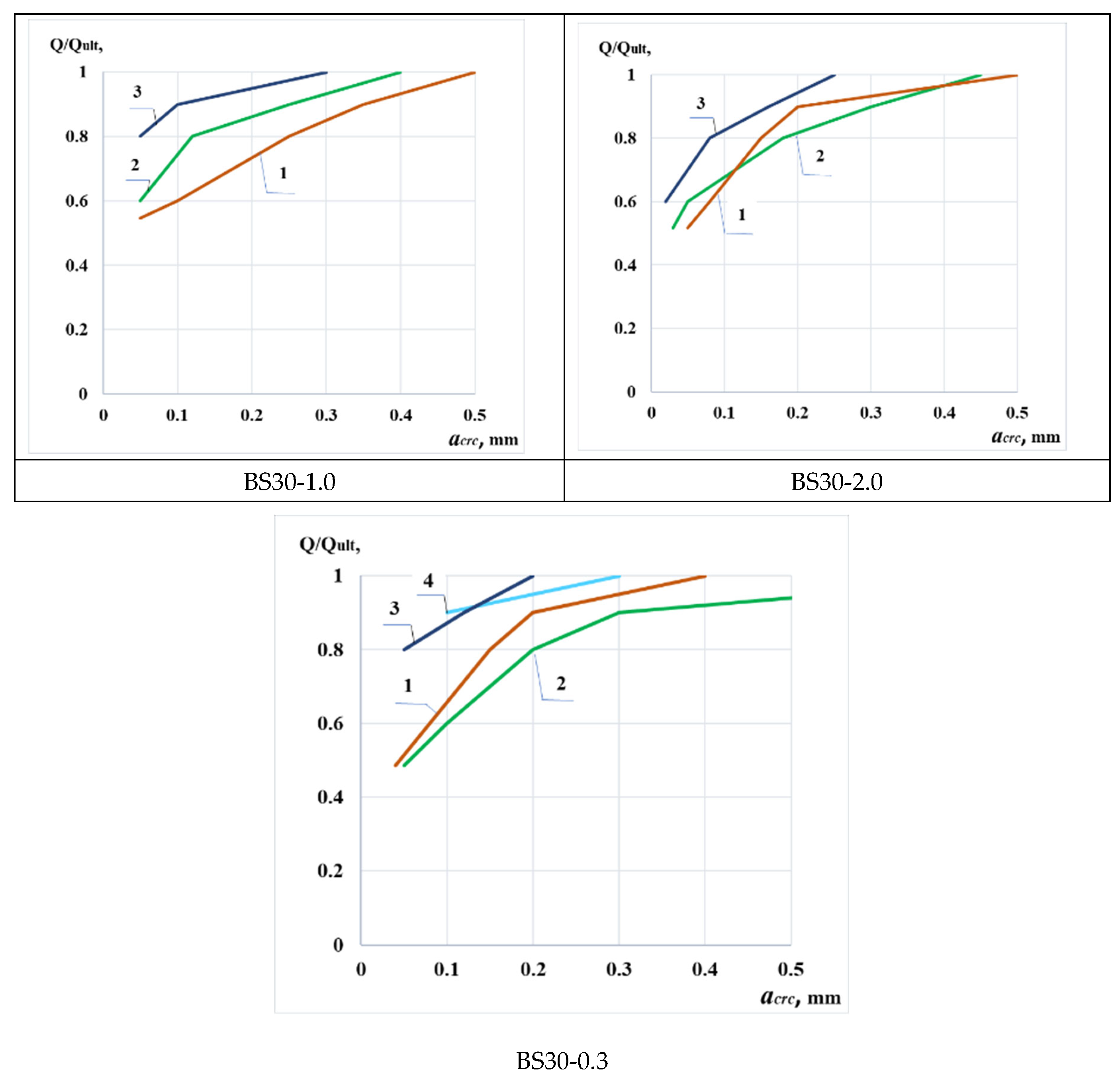

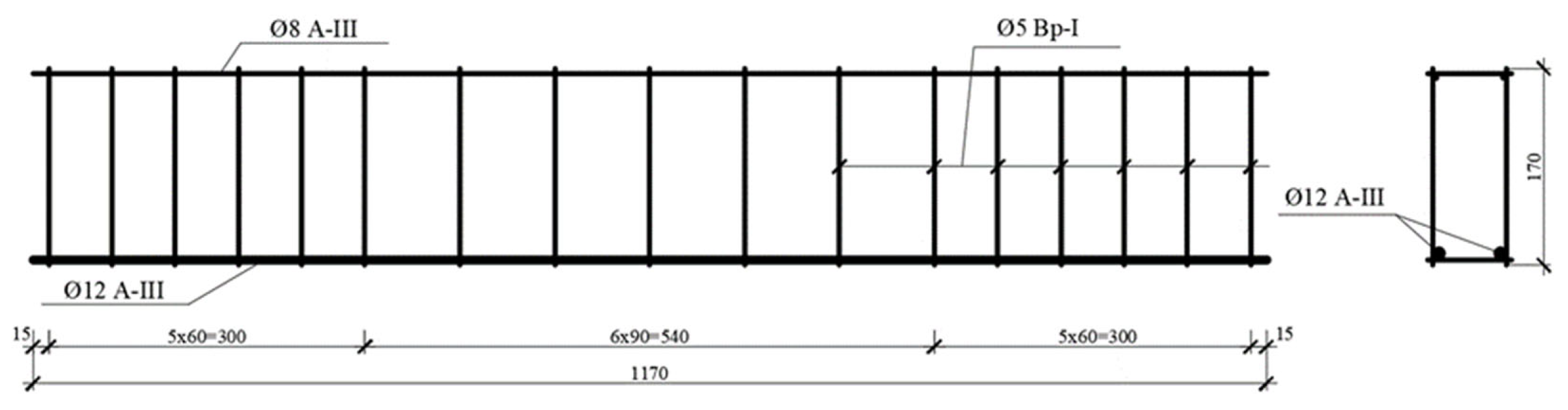

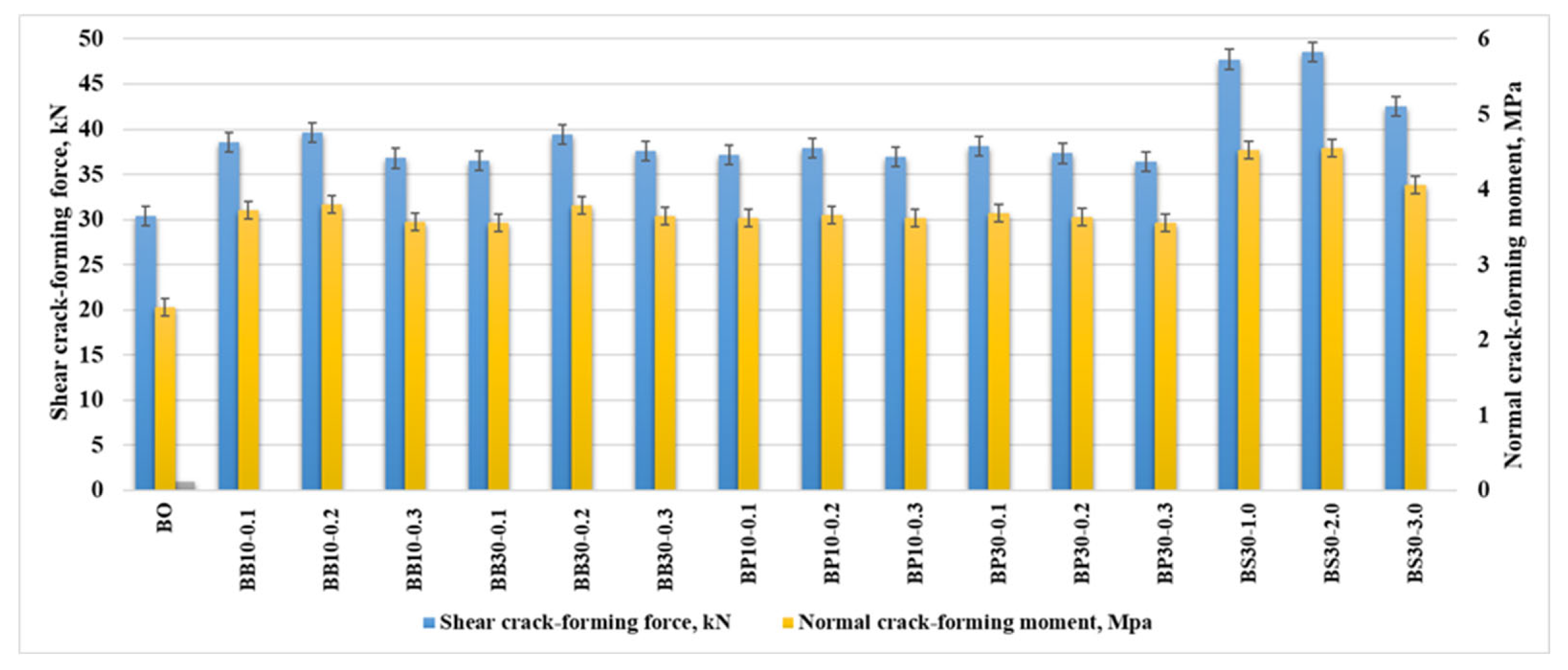

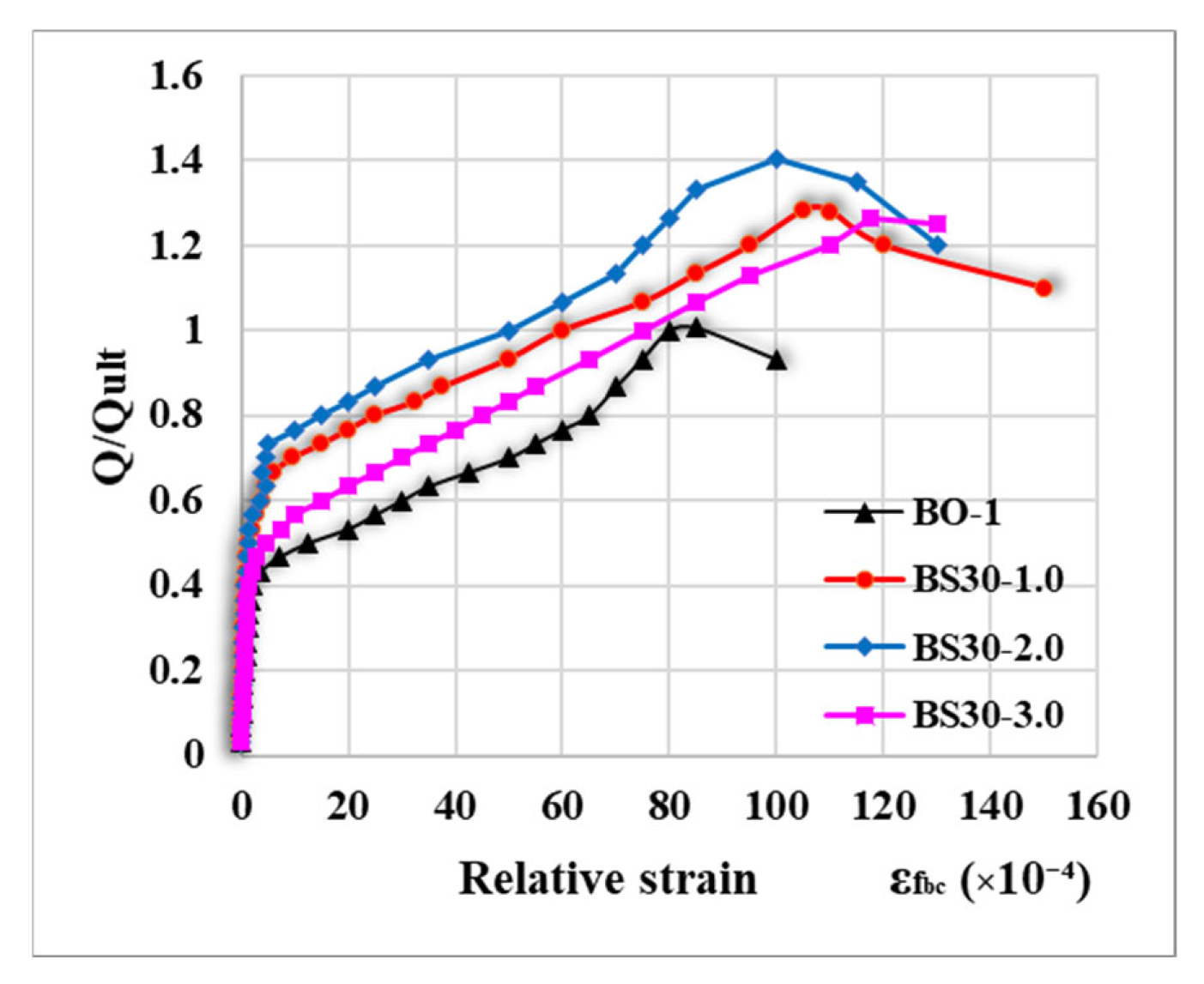

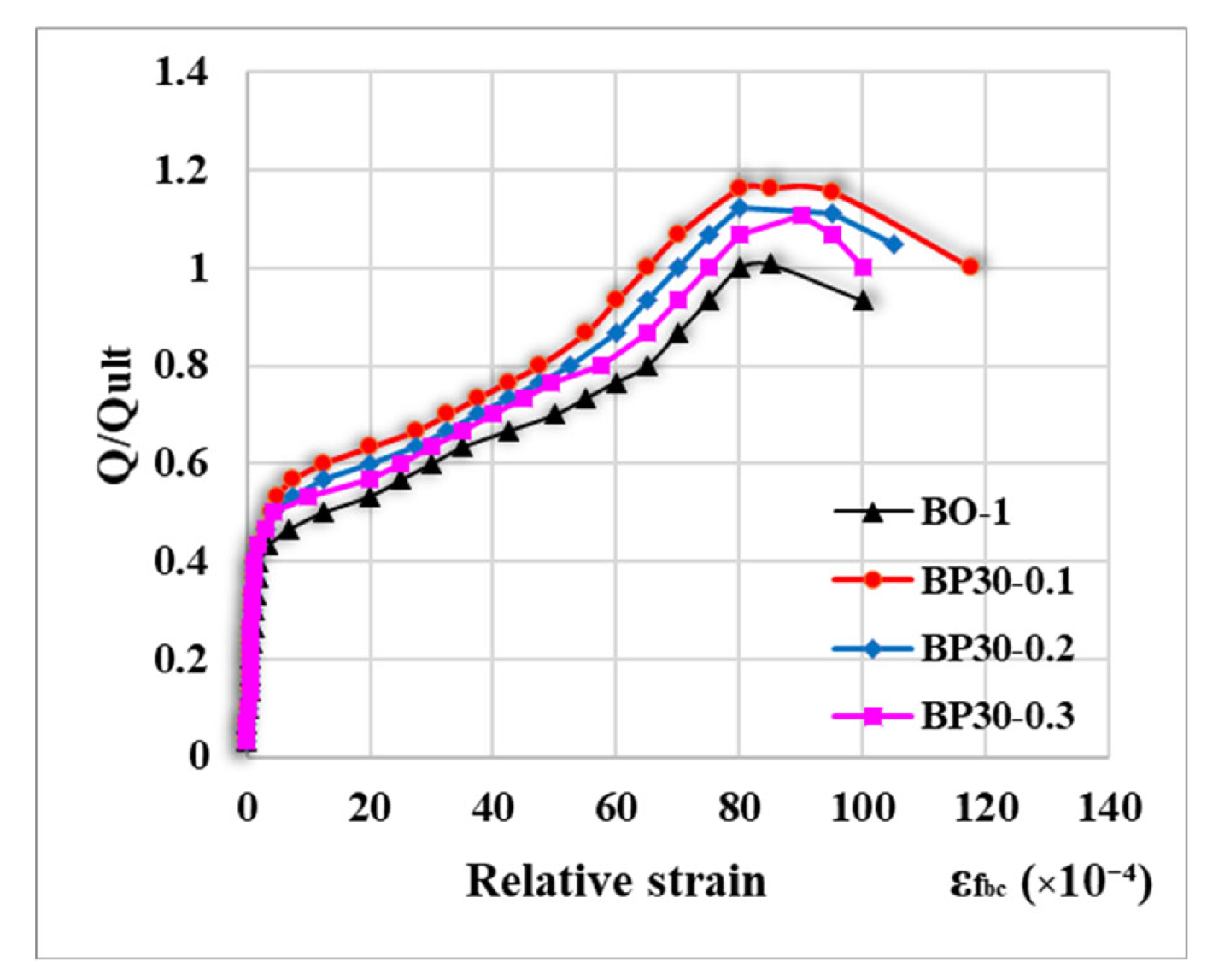

3.1. Formation and Development of Cracks in the Shear Section of Fiber-Reinforced Concrete Beams

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chia, E.; Nguyen, H.B.; Le, K.N.; Bi, K.; Pham, T.M. Performance of hybrid basalt-recycled polypropylene fibre reinforced concrete. Structures 2025, 75, 108711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, M.J. Effect of basalt macro fiber on shear strength of high-strength concrete beams with web openings: A finite element parametric study. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2025, e05088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chia, E.; Nguyen, H.B.K.; Le, K.N.; Bi, K.; Pham, T.M. Performance of hybrid basalt-recycled polypropylene fibre reinforced concrete. Structures 2025, 75, 108711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Cai, L.; Guo, R. Experimental study on the mechanical behaviour of short chopped basalt fibre reinforced concrete beams. Structures 2022, 45, 1110–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheikh, N.A.; Katkhuda, H.; Shatarat, N. Effect of 3D, 4D, 5D steel fibers on the shear behavior of reinforced concrete beams made of recycled coarse aggregate. Constr. Build. Mater. 2025, 460, 139842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhuo, J.; Zhang, Y.; Wan, C. A review of the mechanical properties and durability of basalt fiber-reinforced concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 359, 129360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vairagade, V.S.; Dhale, S.A. Hybrid fibre reinforced concrete–A state of the art review. Hybrid Adv. 2023, 3, 100035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.-F.; Kou, S.-C.; Xing, F. Mechanical and durable properties of chopped basalt fiber reinforced recycled aggregate concrete and the mathematical modeling. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 298, 123901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, C.; Fan, K.; Wu, F.; Chen, D. Experimental study on the mechanical properties and microstructure of chopped basalt fibre reinforced concrete. Mater. Des. 2014, 58, 187–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vedhasakthi, K.; Chithra, R. Strength attributes and microstructural characterization of basalt fibre incorporated self-compacting concrete. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 78, 107592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousavi, S.S.; Dehestani, M. Influence of mixture composition on the structural behaviour of reinforced concrete beam-column joints: A review. Structures 2022, 42, 29–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ralegaonkar, R.; Gavali, H.; Aswath, P.; Abolmaali, S. Application of chopped basalt fibers in reinforced mortar: A review. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 164, 589–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shyamala, G. Impact of reinforcement and geometry of deep beam–Research perspective. Mater. Today Proc. 2022, 68, 1556–1561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Chen, B.; Liu, X.; Liu, C.; Miao, J.; Weng, C.; Luo, Y. Experimental study on bond performance between corroded reinforcement and basalt-polypropylene fiber reinforced concrete after high temperature. Constr. Build. Mater. 2025, 474, 140944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, K.; Gao, Z.; Kang, L. Flexural behavior of steel fiber-reinforced recycled aggregate concrete beam reinforced with hybrid steel and FRP bars. Structures 2025, 80, 109665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Zhou, M.; Wei, B.; Wu, C.; Tang, Z.; Zhang, S.; He, J. Study on flexural cracking characteristics of polypropylene fiber reinforced concrete beams with BFRP bars. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2025, 22, e04372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shabani, H.; Asadian, A.; Galal, K. Flexural and serviceability behaviour of macro-synthetic fibre-reinforced concrete beams reinforced with GFRP bars. Constr. Build. Mater. 2025, 494, 143217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, W.; Chen, W.; Xie, Q.; Wang, P.; Zhang, G. Flexural performance of basalt fiber reinforced recycled aggregate concrete subjected to sulfate corrosion. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2025, e05156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Xiao, J.; Deng, Z.; Yang, H.; Mei, J.; Huang, J. Experimental and modelling investigation of stress-strain behavior of basalt fiber-reinforced coral aggregate concrete under uniaxial and triaxial compression. Constr. Build. Mater. 2025, 496, 143856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Kong, D.; Wang, L.; Liu, A.; Xu, F.; Fang, Z.; Wang, S. Performance of red mud concrete reinforced with single and hybrid Polyvinyl alcohol and Basalt fibers. J. Build. Eng. 2025, 113879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; Li, J.; Liu, Z.; Wu, C.; Liu, J. Behaviour of hybrid polypropylene and steel fibre reinforced ultra-high performance concrete beams against single and repeated impact loading. Structures 2023, 55, 324–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Y.; Xie, T.; Guo, T.; Dong, B.; Zhao, J.; Feng, J. Durability evaluation and life prediction of basalt fiber reinforced aeolian sand concrete in different freeze-thaw media. J. Build. Eng. 2025, 114924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esakki, A.K.D.K.; Dev, S.K.A.; Gomathy, T.; Chella Gifta, C. Influence of adding steel–glass–polypropylene fibers on the strength and flexural behaviour of hybrid fiber reinforced concrete. Mater. Today Proc. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, K.; Wu, Z.; Zheng, K.; Shi, J. Shear behavior of regular oriented steel fiber-reinforced concrete beams reinforced with glass fiber polymer (GFRP) bars. Structures 2024, 63, 106339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mashayekhi, A.; Hassanli, R.; Zhuge, Y.; Ma, X.; Chow, C.W.K.; Bazli, M.; Manalo, A. Shear performance of fibre-reinforced seawater sea-sand concrete–fibre hybridization and synergy effects. Constr. Build. Mater. 2025, 472, 140955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirzaaghabeik, H.; Mashaan, N.S.; Shukla, S.K. Impact of geometrical dimensions on the shear behaviour of UHPC deep beams reinforced with steel and synthetic fibres. Structures 2025, 78, 109260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Yufeng, X.; Saijie, L.; Zhiqiang, X. Experimental study on shear performance of basalt fiber concrete beams without web reinforcement. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2022, 17, e01602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, X.; Wang, F.; Luo, Y.; Liu, X.; Yang, Z.; Mao, H. Mechanical performance study of basalt-polyethylene fiber reinforced concrete under dynamic compressive loading. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 409, 133935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L.; Wu, F.; Ma, Y.; Li, Z.; Chen, A.; Zhao, B.; Cao, J. Flexural performance of steel fiber reinforced MPCC beams: Experimental study and theoretical analysis. Eng. Struct. 2025, 343, 121018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, S.U.; Waseem, S.A. An experimental study on mechanical and fracture characteristics of hybrid fibre reinforced concrete. Structures 2024, 68, 107053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, B.; Chen, H.; Xu, Y.; Fan, C.; Li, H.; Liu, D. Study on fracture characteristics of steel fiber reinforced manufactured sand concrete using DIC technique. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2024, 20, e03200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Z.; Li, H.; Pan, Z.; Li, X.; Lu, L.; He, M.; Li, H.; Liu, F.; Feng, P.; Li, L. Fracture properties and mechanisms of steel fiber and glass fiber reinforced rubberized concrete. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 86, 108866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Rousan, E.T.; Khalid, H.R.; Rahman, M.K. Fresh, mechanical, and durability properties of basalt fiber-reinforced concrete (BFRC): A review. Dev. Built Environ. 2023, 14, 100155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousefi, M.; Khandestani, R.; Gharaei-Moghaddam, N. Flexural behavior of reinforced concrete beams made of normal and polypropylene fiber-reinforced concrete containing date palm leaf ash. Structures 2022, 37, 1053–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azandariani, M.G.; Vajdian, M.; Asghari, K.; Mehrabi, S. Mechanical properties of polyolefin and polypropylene fibers-reinforced concrete–An experimental study. Compos. Part C Open Access 2023, 12, 100410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GOST 10180-2012; The method of determining the accuracy of the control method. Standartinform: Moscow, 2018.

| № | Series | Designation | Fiber type | Fiber length (mm) | Fiber content (%) | Number of specimens |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | S1 (Control) | BO | (Plain concrete) | - | - | 3 |

| 2 | S2 | BB10-0.1 | Basalt | 10 | 0.1 | 3 |

| 3 | BB10-0.2 | Basalt | 10 | 0.2 | 3 | |

| 4 | BB10-0.3 | Basalt | 10 | 0.3 | 3 | |

| 5 | BB30-0.1 | Basalt | 30 | 0.1 | 3 | |

| 6 | BB30-0.2 | Basalt | 30 | 0.2 | 3 | |

| 7 | BB30-0.3 | Basalt | 30 | 0.3 | 3 | |

| 8 | S3 | BP10-0.1 | Polypropylene | 10 | 0.1 | 3 |

| 9 | BP10-0.2 | Polypropylene | 10 | 0.2 | 3 | |

| 10 | BP10-0.3 | Polypropylene | 10 | 0.3 | 3 | |

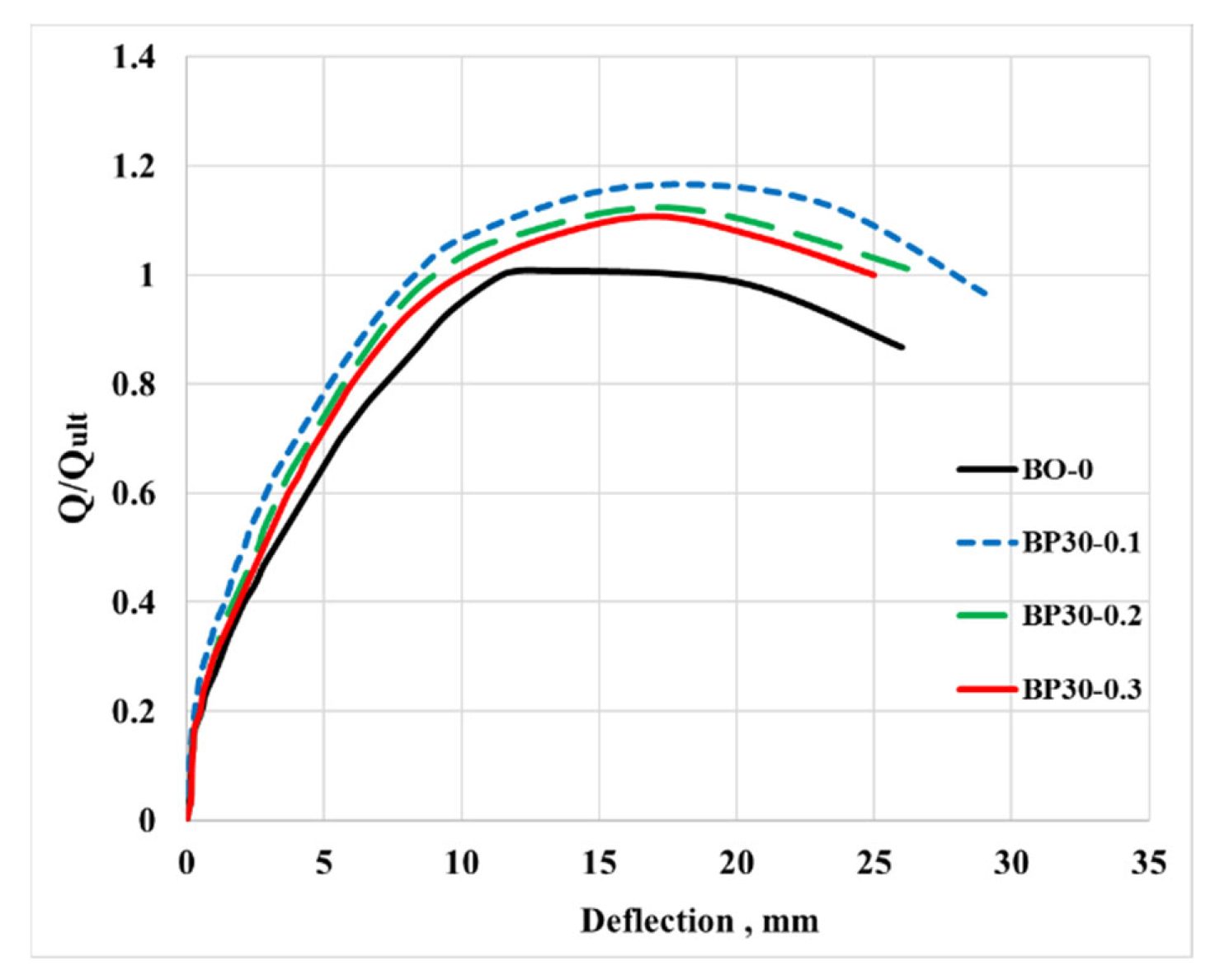

| 11 | BP30-0.1 | Polypropylene | 30 | 0.1 | 3 | |

| 12 | BP30-0.2 | Polypropylene | 30 | 0.2 | 3 | |

| 13 | BP30-0.3 | Polypropylene | 30 | 0.3 | 3 | |

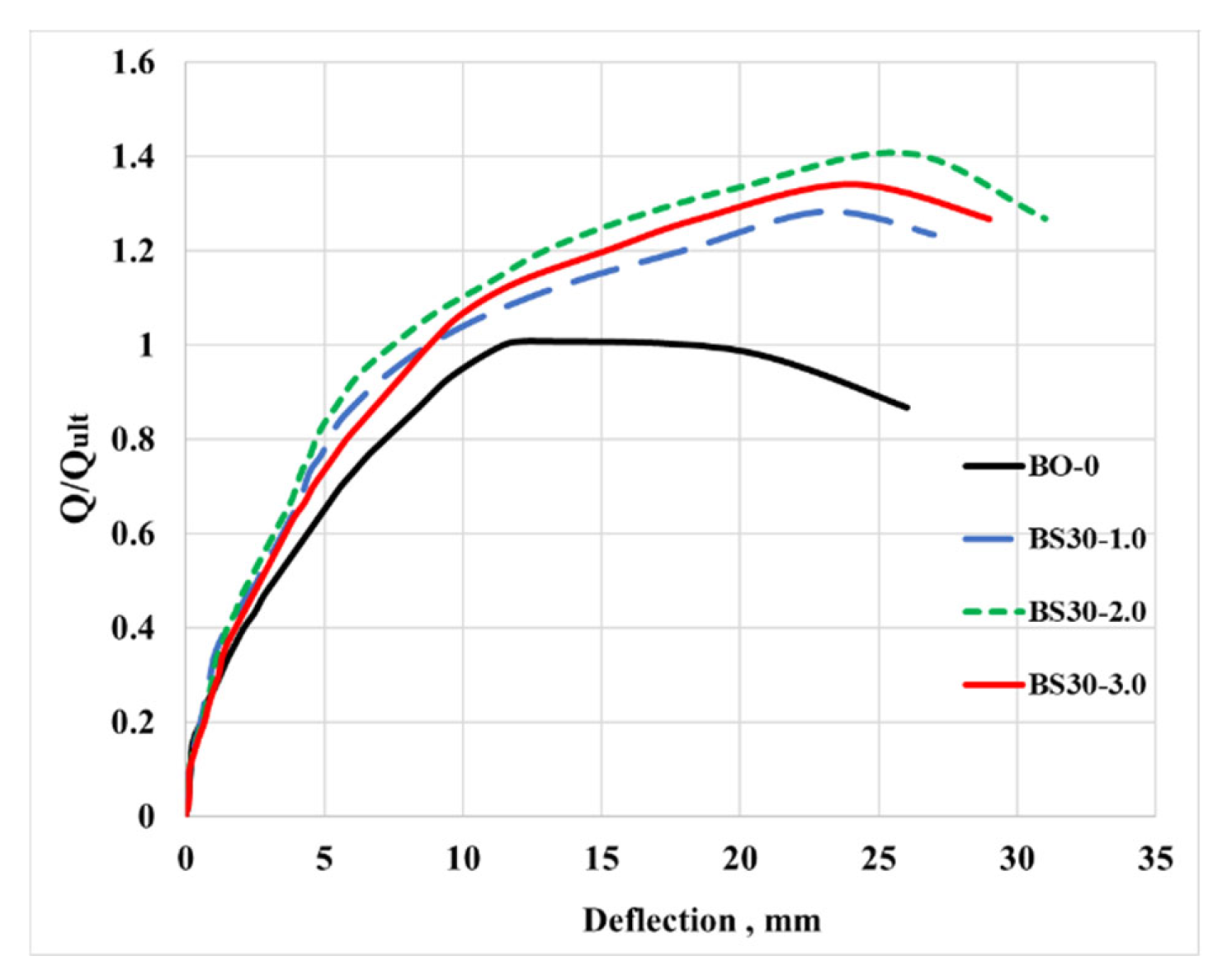

| 14 | S4 | BS30-1.0 | Steel | 30 | 0.1 | 3 |

| 15 | BS30-2.0 | Steel | 30 | 0.2 | 3 | |

| 16 | BS30-3.0 | Steel | 30 | 0.3 | 3 |

| Fiber type | Density (kg/m³) | Tensile strength (MPa) | Elastic modulus (GPa) | Fiber length (mm) | Fiber diameter (mm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Basalt | 2650 | 3500 | 110 | 10, 30 | 0.017 |

| Polypropylene | 910 | 500 | 35 | 10, 30 | 0.018 |

| Steel | 7850 | 250 | 200 | 30 | 0.3 |

| Designation | Compressive strength (MPa) | Tensile strength (MPa) | Residual tensile strength (MPa) | Flexural strength (MPa) | Elastic modulus (GPa) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BO | 34.6 | 2.21 | – | 4.41 | 30.91 |

| BB10-0.1 | 40.7 | 2.81 | 1.16 | 5.52 | 34.9 |

| BB10-0.2 | 41.8 | 2.89 | 1.29 | 5.81 | 35.4 |

| BB10-0.3 | 39.9 | 2.68 | 1.19 | 5.49 | 34.2 |

| BB30-0.1 | 39.8 | 2.66 | 1.21 | 5.61 | 33.7 |

| BB30-0.2 | 41.1 | 2.87 | 1.32 | 5.76 | 35.0 |

| BB30-0.3 | 40.2 | 2.74 | 1.26 | 5.68 | 34.1 |

| BP10-0.1 | 38.6 | 2.71 | 1.25 | 5.54 | 34.6 |

| BP10-0.2 | 39.9 | 2.76 | 1.20 | 5.73 | 34.8 |

| BP10-0.3 | 38.2 | 2.69 | 1.12 | 5.30 | 33.4 |

| BP30-0.1 | 39.7 | 2.78 | 1.23 | 5.62 | 35.1 |

| BP30-0.2 | 38.9 | 2.72 | 1.18 | 5.42 | 34.6 |

| BS30-0.3 | 38.1 | 2.65 | 1.10 | 5.31 | 34.1 |

| BS30-1.0 | 45.1 | 3.48 | 1.62 | 6.42 | 35.6 |

| BS30-2.0 | 47.2 | 3.54 | 1.75 | 6.56 | 36.8 |

| BS30-3.0 | 44.3 | 3.10 | 1.53 | 6.33 | 34.8 |

| Series | ID | Mcrc,(kN‧m) | Qcrc,(kN) | Crack width at 50% Qmax, (mm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| S1 (Control) | BO | 2.69 | 32.23 | 0.37 |

| S2 | BB10-0.1 | 4.37 | 41.97 | 0.21 |

| BB10-0.2 | 4.46 | 42.12 | 0.19 | |

| BB10-0.3 | 4.02 | 39.06 | 0.22 | |

| BB30-0.1 | 4.09 | 38.92 | 0.20 | |

| BB30-0.2 | 4.25 | 40.69 | 0.18 | |

| BB30-0.3 | 3.90 | 39.87 | 0.25 | |

| S3 | BP10-0.1 | 3.80 | 38.05 | 0.21 |

| BP10-0.2 | 3.99 | 41.14 | 0.24 | |

| BP10-0.3 | 3.92 | 38.28 | 0.26 | |

| BP30-0.1 | 4.01 | 40.49 | 0.20 | |

| BP30-0.2 | 3.87 | 39.10 | 0.25 | |

| BS30-0.3 | 3.81 | 38.56 | 0.20 | |

| S4 | BS30-1.0 | 4.60 | 52.59 | 0.15 |

| BS30-2.0 | 5.00 | 54.42 | 0.10 | |

| BS30-3.0 | 4.71 | 48.62 | 0.12 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).