Submitted:

29 December 2025

Posted:

30 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

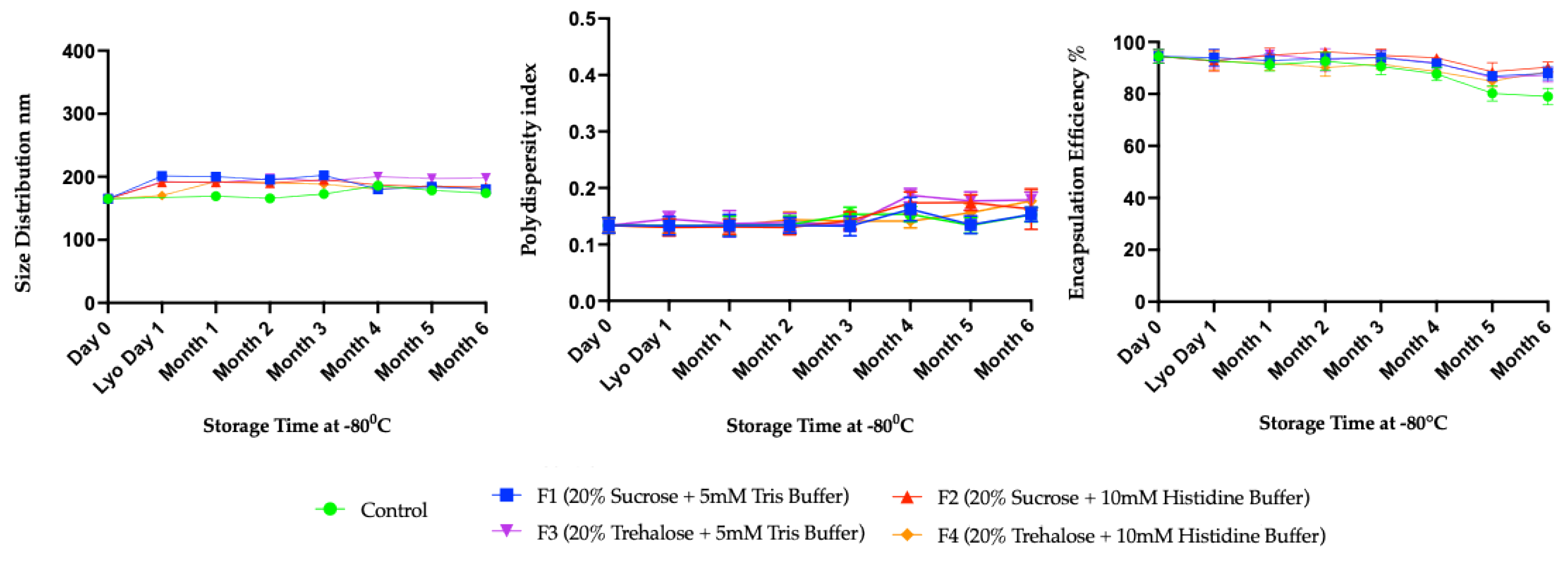

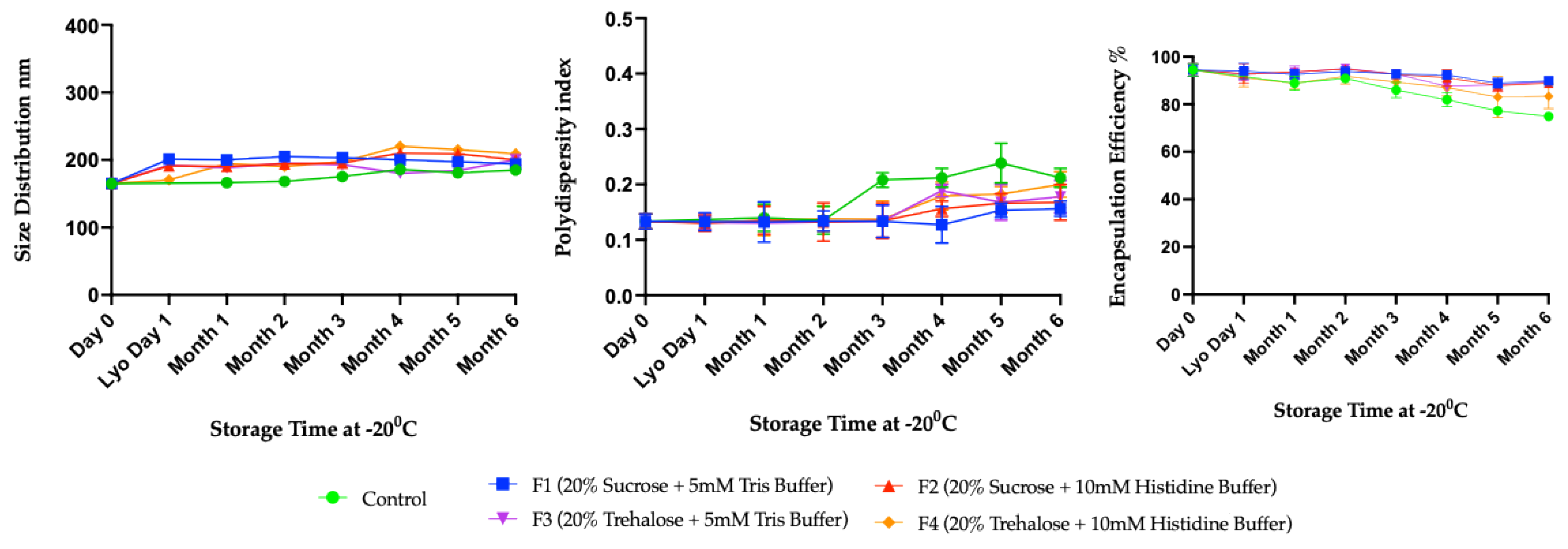

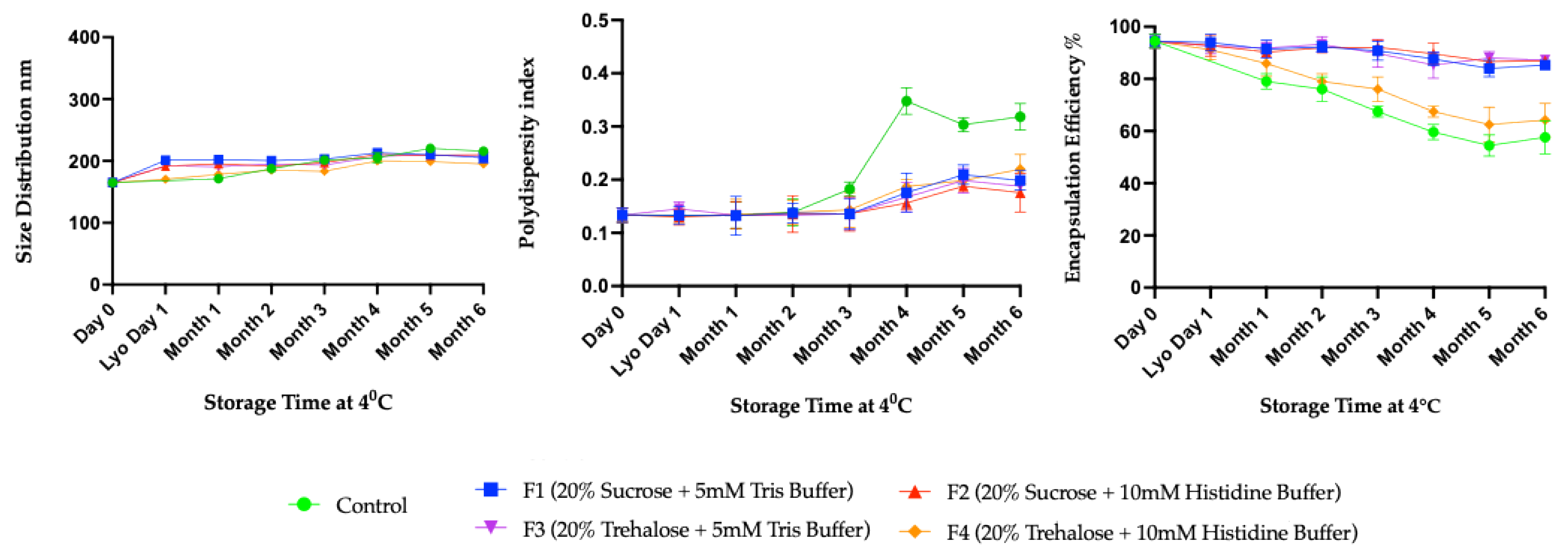

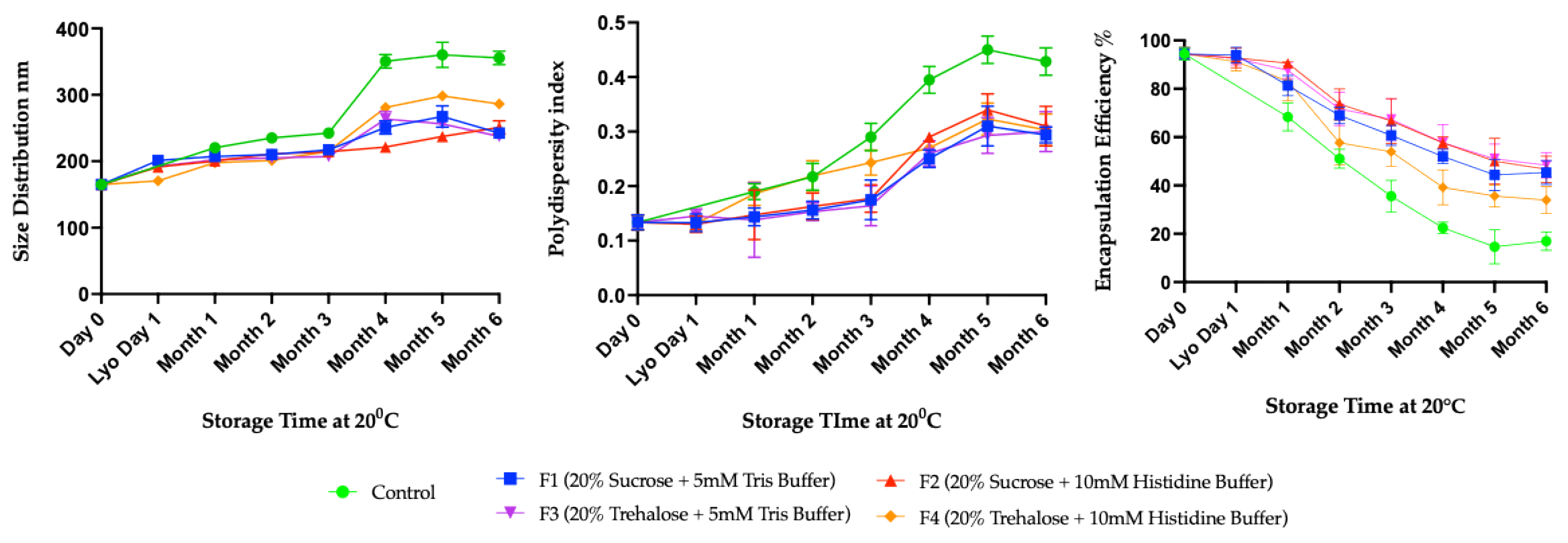

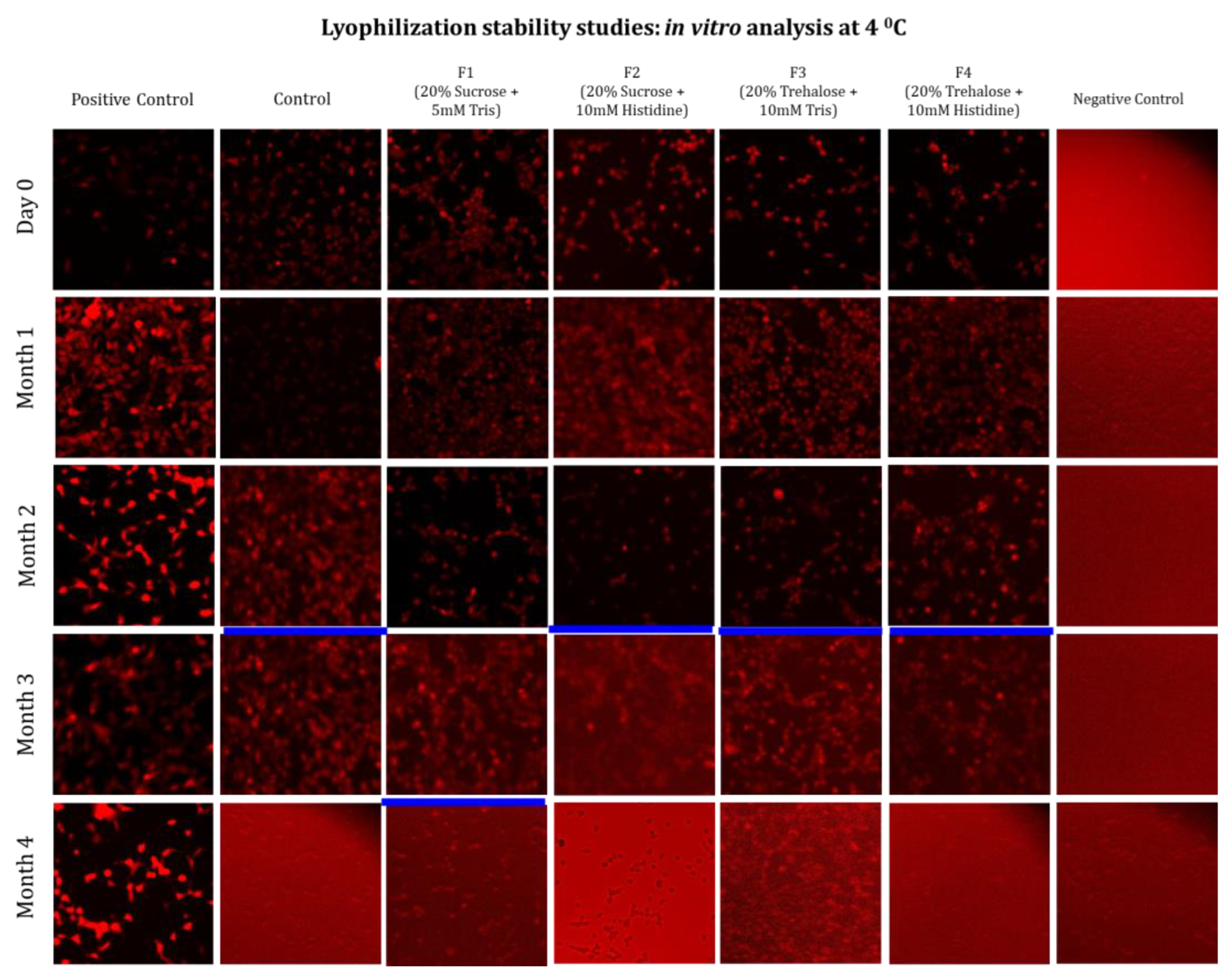

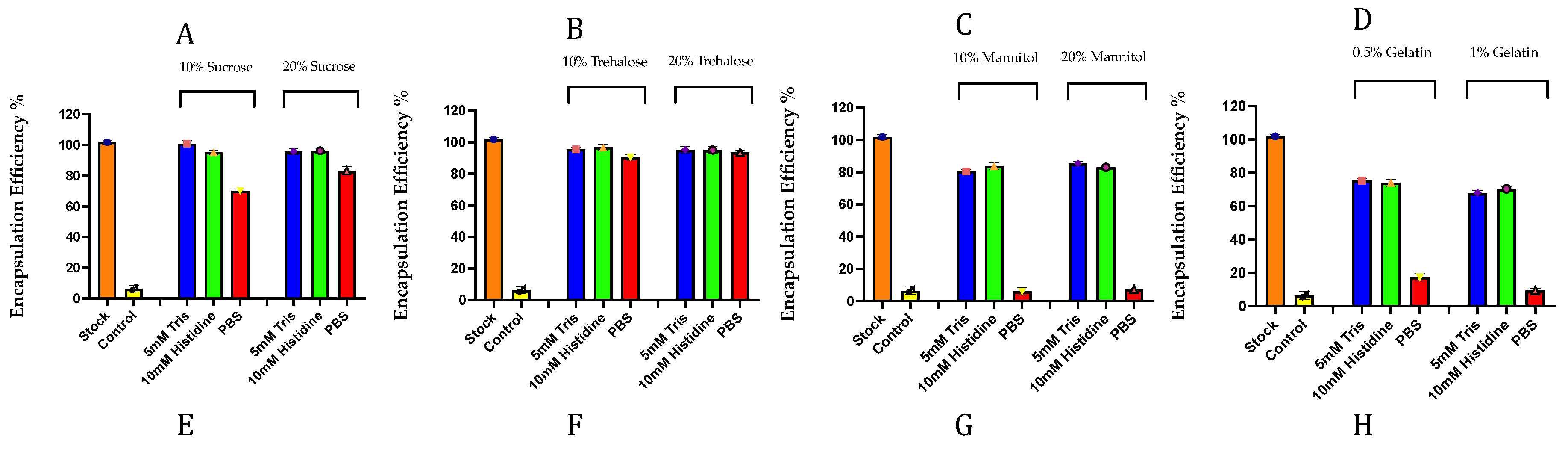

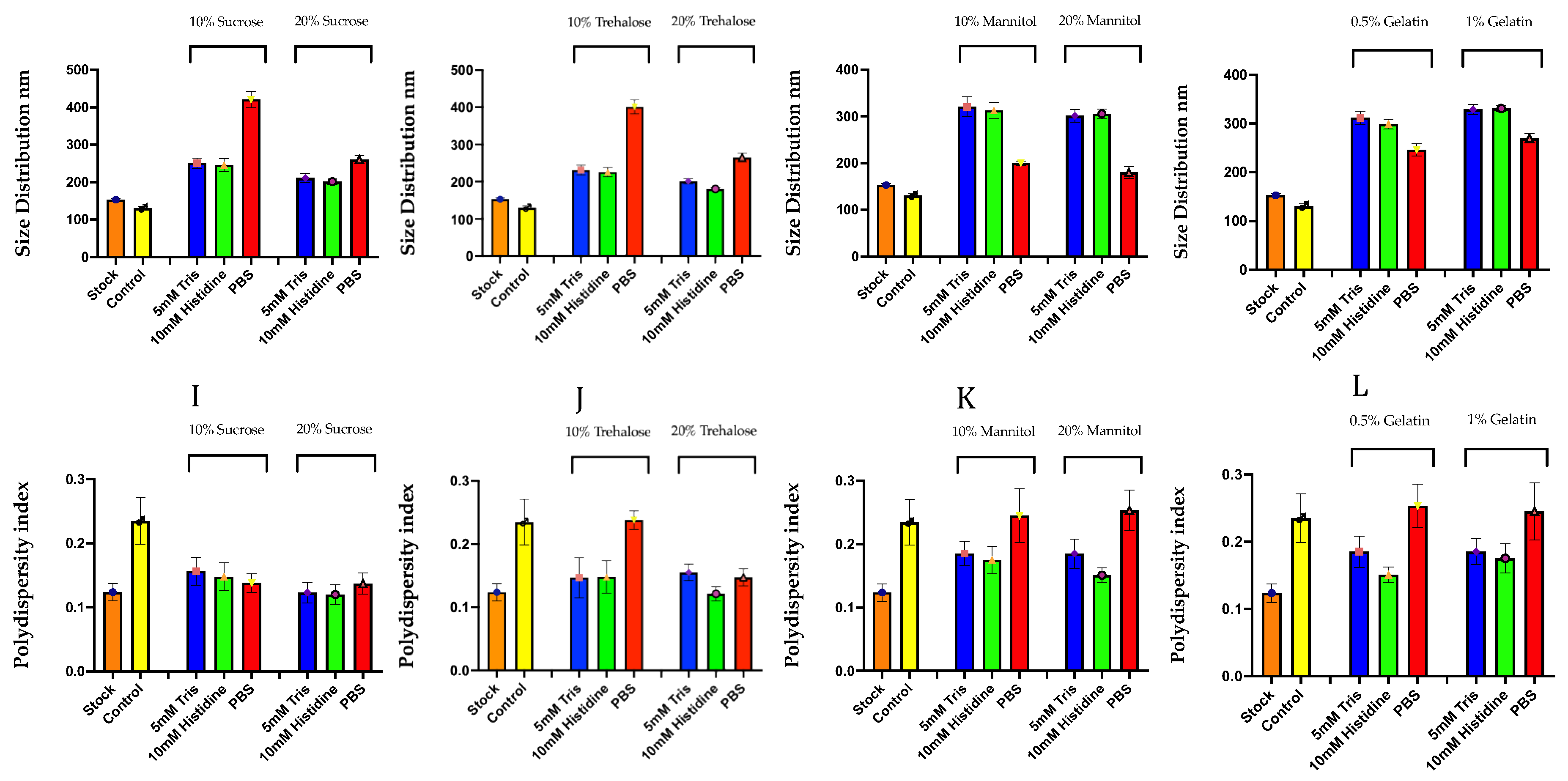

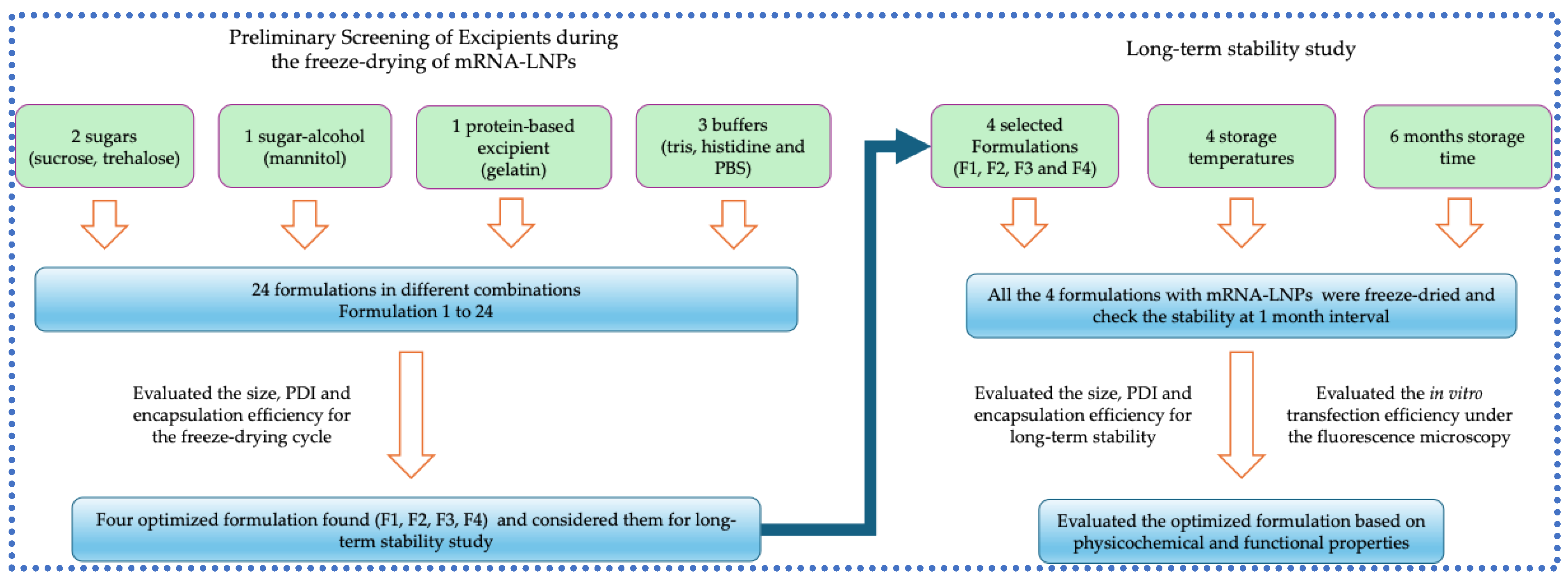

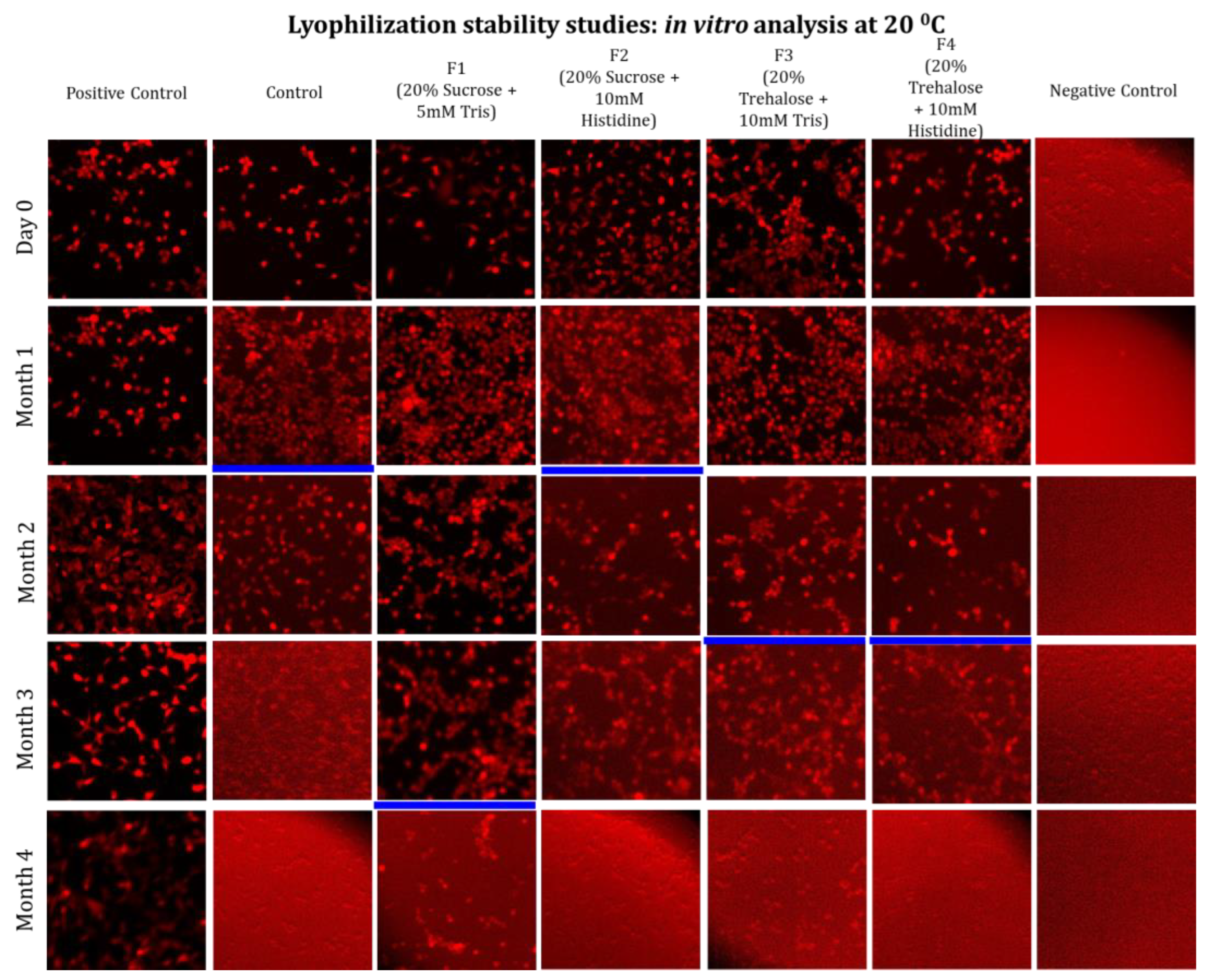

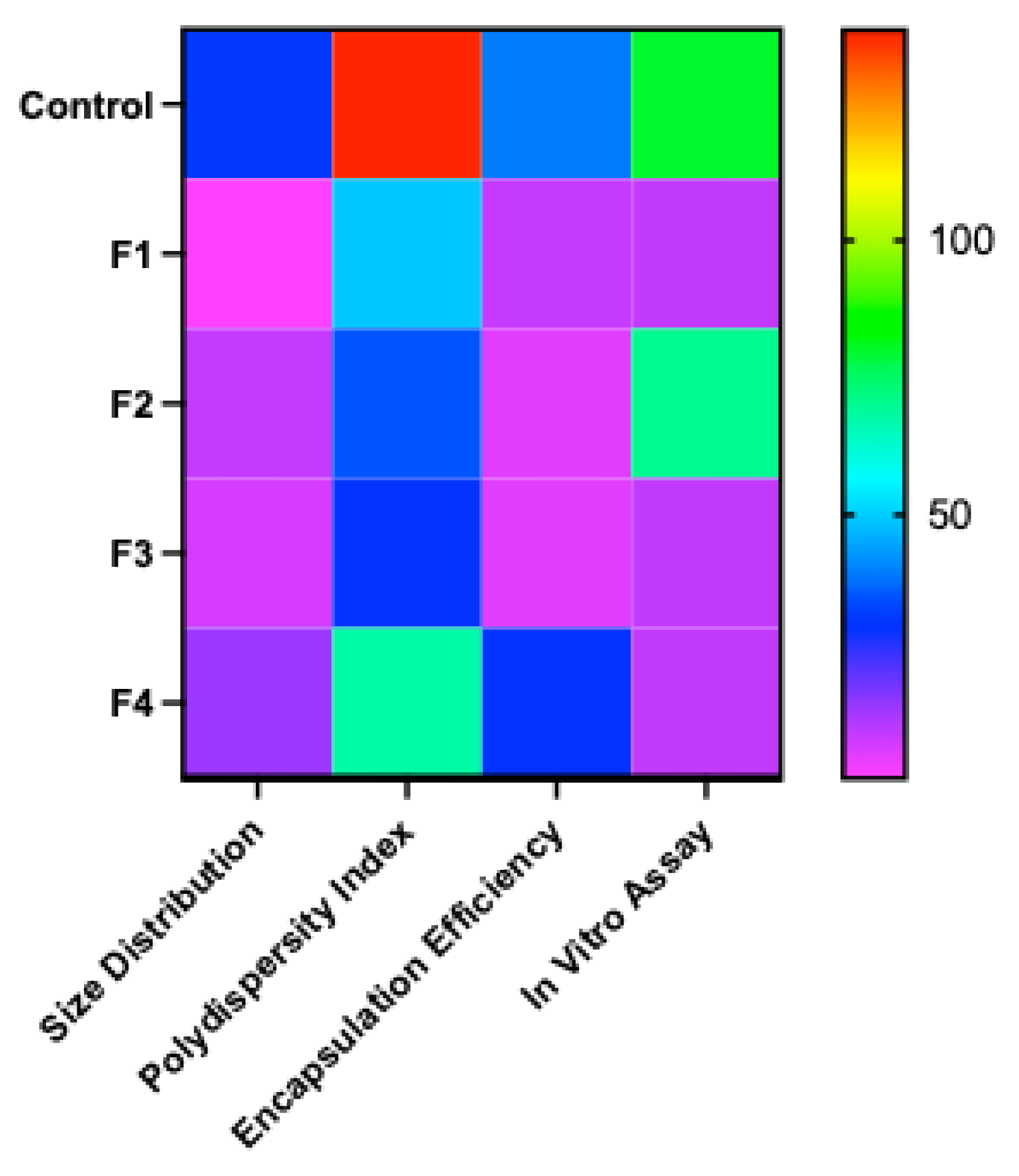

Background: Thermostability remains a key bottleneck for equitable access to mRNA–LNP vaccines, largely due to cold-chain requirements. Objectives and methods: Here, we optimized freeze-drying formulations by screening excipients (sugars, sugar-alcohols, and proteins) and buffers to preserve mRNA–LNP physicochemical (size, polydispersity index -PDI and encapsulation efficiency -EE) and fluorescence intensity-based, functional integrity assay (in vitro transfection) during long-term storage of up to 6 months. Results: In a preliminary screening study, different sugars (sucrose, trehalose), sugar alcohol (mannitol), protein (gelatin) and different buffers (Tris, PBS, histidine) were evaluated. The preliminary result showed that sucrose and trehalose, along with Tris and histidine buffers, had a positive effect on maintaining the physicochemical properties during freeze-drying, while mannitol, gelatin and PBS buffer had a negative effect. Based on these findings, the optimized formulations containing sucrose/Tris, sucrose/histidine, trehalose/Tris and trehalose/histidine were chosen, and a stability study was performed at −80, −20, 4, and 20 °C for six months. Conclusions: Overall, except for the samples maintained at 20 °C, no significant changes in the physicochemical quality of the freeze-dried mRNA-LNPs were observed over six months at −80, −20, and 4 °C. The in vitro stability study demonstrated stability at 4 °C for four months across all formulations, while a formulation with sucrose/Tris maintained satisfactory stability even at 20 °C for the same duration. The main results of this study demonstrate the feasibility of storing mRNA drug products as solid formulations at non-freezing temperatures (≤ 4 °C).

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Preparation of mRNA-LNPs

2.2. Freeze-Drying

| Freezing | Primary Drying | Secondary drying | |

| Temperature | -50 °C | -30 °C | 20 °C |

| Pressure | - | mTorr | 30 mTorr |

2.3. Stability Study

2.4. mRNA-LNP Characterization

2.4.1. Encapsulation Efficiency (EE%)

2.4.2. Particle Size and Polydispersity Index (PDI)

2.5. In Vitro Assay for mRNA-LNPs

3. Results

3.1. Preliminary Screening of Excipients During the Freeze-Drying of mRNA-LNPs

3.2. Long-Term Stability Study

4. Discussion

Impact of Manual Mixing on Initial mRNA–LNP Physicochemical Properties

Freeze-Drying–Induced Stresses and Their Effects on mRNA–LNP Stability

Role of Excipients in Preserving Particle Size and Polydispersity During Lyophilization

Structural Rearrangements of Lipid Nanoparticles During Freeze-Drying

Mechanistic Basis of Encapsulation Efficiency Loss in Excipient-Free Formulations

Sugars Are Better Cryoprotectants for mRNA-LNPs Than Sugar Alcohols and Proteins(Gelatin)

Buffer-Dependent Modulation of pH, Ionic Strength, and LNP Integrity

Glass Transition and Vitrification Effects in Stabilizing mRNA–LNPs

Long-Term Stability of Freeze-Dried mRNA–LNPs at Subzero and Refrigerated Temperatures

Limitations of Ambient Temperature Storage (20 °C)

5. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- M. Li et al., “Lyophilization process optimization and molecular dynamics simulation of mRNA-LNPs for SARS-CoV-2 vaccine,” NPJ Vaccines, vol. 8, no. 1, p. 153, Oct. 2023. [CrossRef]

- M. Youssef, C. Hitti, J. Puppin Chaves Fulber, M. F. H. Khan, A. Sudalaiyadum Perumal, and A. A. Kamen, “Preliminary Evaluation of Formulations for Stability of mRNA-LNPs Through Freeze-Thaw Stresses and Long-Term Storage,” May 2025. [CrossRef]

- M. F. H. Khan, F. Baudin, A. S. Perumal, and A. A. Kamen, “Freeze-Drying of mRNA-LNPs Vaccines: A Review,” Vaccines 2025, Vol. 13, Page 853, vol. 13, no. 8, p. 853, Aug. 2025. [CrossRef]

- M. F. H. Khan, M. Youssef, S. Nesdoly, and A. A. Kamen, “Development of Robust Freeze-Drying Process for Long-Term Stability of rVSV-SARS-CoV-2 Vaccine,” Viruses, vol. 16, no. 6, p. 942, Jun. 2024. [CrossRef]

- G. Zhang, T. Tang, Y. Chen, X. Huang, and T. Liang, “mRNA vaccines in disease prevention and treatment,” Signal Transduct Target Ther, vol. 8, no. 1, p. 365, Sep. 2023. [CrossRef]

- N. Pardi, M. J. Hogan, F. W. Porter, and D. Weissman, “mRNA vaccines — a new era in vaccinology,” Nature Reviews Drug Discovery 2018 17:4, vol. 17, no. 4, pp. 261–279, Jan. 2018. [CrossRef]

- K. Hashiba et al., “Overcoming thermostability challenges in mRNA–lipid nanoparticle systems with piperidine-based ionizable lipids,” Commun Biol, vol. 7, no. 1, Dec. 2024. [CrossRef]

- M. N. Uddin and M. A. Roni, “Challenges of Storage and Stability of mRNA-Based COVID-19 Vaccines,” Vaccines (Basel), vol. 9, no. 9, p. 1033, Sep. 2021. [CrossRef]

- C. J. Decker and R. Parker, “Mechanisms of mRNA degradation in eukaryotes,” Trends Biochem Sci, vol. 19, no. 8, pp. 336–340, Aug. 1994. [CrossRef]

- L. Schoenmaker et al., “mRNA-lipid nanoparticle COVID-19 vaccines: Structure and stability,” Int J Pharm, vol. 601, p. 120586, May 2021. [CrossRef]

- R. E. Young, S. I. Hofbauer, and R. S. Riley, “Overcoming the challenge of long-term storage of mRNA-lipid nanoparticle vaccines,” Molecular Therapy, vol. 30, no. 5, pp. 1792–1793, May 2022. [CrossRef]

- H. Zhang and M. Barz, “Investigating the stability of RNA-lipid nanoparticles in biological fluids: Unveiling its crucial role for understanding LNP performance,” Journal of Controlled Release, vol. 381, p. 113559, May 2025. [CrossRef]

- E. Oude Blenke et al., “The Storage and In-Use Stability of mRNA Vaccines and Therapeutics: Not A Cold Case,” J Pharm Sci, vol. 112, no. 2, pp. 386–403, Feb. 2023. [CrossRef]

- F. Cheng et al., “Research Advances on the Stability of mRNA Vaccines,” Viruses, vol. 15, no. 3, p. 668, Mar. 2023. [CrossRef]

- T. Alejo et al., “Comprehensive Optimization of a Freeze-Drying Process Achieving Enhanced Long-Term Stability and In Vivo Performance of Lyophilized mRNA-LNPs,” Int J Mol Sci, vol. 25, no. 19, p. 10603, Oct. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Y. Fan et al., “Physicochemical and structural insights into lyophilized mRNA-LNP from lyoprotectant and buffer screenings,” Journal of Controlled Release, vol. 373, pp. 727–737, Sep. 2024. [CrossRef]

- T. Wang, T. Yu, W. Li, Q. Liu, T.-C. Sung, and A. Higuchi, “Design and lyophilization of mRNA-encapsulating lipid nanoparticles,” Int J Pharm, vol. 662, p. 124514, Sep. 2024. [CrossRef]

- S. Meulewaeter et al., “Continuous freeze-drying of messenger RNA lipid nanoparticles enables storage at higher temperatures,” Journal of Controlled Release, vol. 357, pp. 149–160, May 2023. [CrossRef]

- L. Ai et al., “Lyophilized mRNA-lipid nanoparticle vaccines with long-term stability and high antigenicity against SARS-CoV-2,” Cell Discov, vol. 9, no. 1, p. 9, Jan. 2023. [CrossRef]

- A. Ruppl, D. Kiesewetter, M. Köll-Weber, T. Lemazurier, R. Süss, and A. Allmendinger, “Formulation screening of lyophilized mRNA-lipid nanoparticles,” Int J Pharm, vol. 671, Feb. 2025. [CrossRef]

- X. Jiao et al., “Insights into the formulation of lipid nanoparticles for the optimization of mRNA therapeutics,” Wiley Interdiscip Rev Nanomed Nanobiotechnol, vol. 16, no. 5, p. e1992, Sep. 2024. [CrossRef]

- B. Wang et al., “Lyophilized monkeypox mRNA lipid nanoparticle vaccines with long-term stability and robust immune responses in mice,” Hum Vaccin Immunother, vol. 21, no. 1, p. 2477384, Dec. 2025. [CrossRef]

- S. Dash et al., “A rapid procedure to generate stably transfected HEK293 suspension cells for recombinant protein manufacturing: Yield improvements, bioreactor production and downstream processing,” Protein Expr Purif, vol. 210, p. 106295, Oct. 2023. [CrossRef]

- T. J. Collins, “ImageJ for microscopy,” Biotechniques, vol. 43, no. 1 Suppl, Jul. 2007. [CrossRef]

- D. M. Strelkova Petersen, N. Chaudhary, M. L. Arral, R. M. Weiss, and K. A. Whitehead, “The mixing method used to formulate lipid nanoparticles affects mRNA delivery efficacy and organ tropism,” European Journal of Pharmaceutics and Biopharmaceutics, vol. 192, pp. 126–135, Nov. 2023. [CrossRef]

- B. J. Heiser et al., “Systematic screening of excipients to stabilize aerosolized lipid nanoparticles for enhanced mRNA delivery,” RSC Pharmaceutics, vol. 2, no. 5, pp. 1139–1154, Sep. 2025. [CrossRef]

- J. B. Simonsen, “A perspective on bleb and empty LNP structures,” Journal of Controlled Release, vol. 373, pp. 952–961, Sep. 2024. [CrossRef]

- M. I. Henderson, Y. Eygeris, A. Jozic, M. Herrera, and G. Sahay, “Leveraging Biological Buffers for Efficient Messenger RNA Delivery via Lipid Nanoparticles,” Mol Pharm, vol. 19, no. 11, pp. 4275–4285, Nov. 2022. [CrossRef]

- H. Muramatsu et al., “Lyophilization provides long-term stability for a lipid nanoparticle-formulated, nucleoside-modified mRNA vaccine,” Molecular Therapy, vol. 30, no. 5, pp. 1941–1951, May 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. F. H. Khan, C. E. Wagner, and A. A. Kamen, “Development of Long-Term Stability of Enveloped rVSV Viral Vector Expressing SARS-CoV-2 Antigen Using a DOE-Guided Approach,” Vaccines (Basel), vol. 12, no. 11, Nov. 2024. [CrossRef]

- S. Kanti Dey, R. Islam, T. Islam, S. Islam, and N. Hasan, “Molecular Epidemiology of Influenza in Asia,” EASTERN JOURNAL OF MEDICINE, vol. 19, no. 3, pp. 119–125, Jan. 2015, Accessed: Jul. 25, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://dergipark.org.tr/en/pub/ejm/issue/5369/72760.

- F. Ahmed, A. Alim, F. Alam, T. Islam, and A. A. Talukder, “Bio-Geo-Chemical Characterization of Bangladeshi Textile Effluents,” Adv Microbiol, vol. 05, no. 05, pp. 317–324, 2015. [CrossRef]

- A. K. M. F. Mahmud, K. M. Z. Rahman, S. K. Dey, T. Islam, and A. A. Talukder, “Genome Annotation and Comparative Genomics of ORF Virus,” Adv Microbiol, vol. 04, no. 15, pp. 1117–1131, 2014. [CrossRef]

- T. Islam et al., “Optimization of Acetic Acid Production Rate by Thermotolerant <i>Acetobacter</i> spp.,” Adv Microbiol, vol. 07, no. 11, pp. 749–759, 2017. [CrossRef]

- X. H. Liu, H. P. Song, L. L. Tao, Z. Zhai, J. X. Huang, and Y. X. Cheng, “Trehalose-loaded LNPs enhance mRNA stability and bridge in vitro in vivo efficacy gap,” NPJ Vaccines, vol. 10, no. 1, pp. 1–12, Dec. 2025. [CrossRef]

- A. Torge, P. Grützmacher, F. Mücklich, and M. Schneider, “The influence of mannitol on morphology and disintegration of spray-dried nano-embedded microparticles,” European Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences, vol. 104, pp. 171–179, Jun. 2017. [CrossRef]

- K. Ogawa et al., “Stable and inhalable powder formulation of mRNA-LNPs using pH-modified spray-freeze drying,” Int J Pharm, vol. 665, p. 124632, Nov. 2024. [CrossRef]

- “Identifying Critical Quality Attributes for mRNA/LNP.” Accessed: May 26, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.biophorum.com/news/an-industry-standard-for-mrna-lnp-analytics/.

- H. K. Wayment-Steele et al., “Theoretical basis for stabilizing messenger RNA through secondary structure design,” bioRxiv, Aug. 2021. [CrossRef]

- D. Shirane et al., “Development of an Alcohol Dilution–Lyophilization Method for the Preparation of mRNA-LNPs with Improved Storage Stability,” Pharmaceutics, vol. 15, no. 7, p. 1819, Jun. 2023. [CrossRef]

- J. Kim, Y. Eygeris, M. Gupta, and G. Sahay, “Self-assembled mRNA vaccines,” Adv Drug Deliv Rev, vol. 170, pp. 83–112, Mar. 2021. [CrossRef]

- C. Zeng, C. Zhang, P. G. Walker, and Y. Dong, “Formulation and Delivery Technologies for mRNA Vaccines,” Curr Top Microbiol Immunol, vol. 440, p. 71, 2022. [CrossRef]

- P. Zhao et al., “Long-term storage of lipid-like nanoparticles for mRNA delivery,” Bioact Mater, vol. 5, no. 2, pp. 358–363, Jun. 2020. [CrossRef]

- B. Kim et al., “Optimization of storage conditions for lipid nanoparticle-formulated self-replicating RNA vaccines,” Journal of Controlled Release, vol. 353, pp. 241–253, Jan. 2023. [CrossRef]

| Buffer | Concentration | Excipients | Concentration | Formulations |

| Tris | 5 mM | Sucrose | 10% | 1 |

| Sucrose | 20% | 2 | ||

| Trehalose | 10% | 3 | ||

| Trehalose | 20% | 4 | ||

| Mannitol | 10% | 5 | ||

| Mannitol | 20% | 6 | ||

| Gelatin | 0.5% | 7 | ||

| Gelatin | 1% | 8 | ||

| Histidine | 10 mM | Sucrose | 10% | 9 |

| Sucrose | 20% | 10 | ||

| Trehalose | 10% | 11 | ||

| Trehalose | 20% | 12 | ||

| Mannitol | 10% | 13 | ||

| Mannitol | 20% | 14 | ||

| Gelatin | 0.5% | 15 | ||

| Gelatin | 1% | 16 | ||

| PBS | 1 X | Sucrose | 10% | 17 |

| Sucrose | 20% | 18 | ||

| Trehalose | 10% | 19 | ||

| Trehalose | 20% | 20 | ||

| Mannitol | 10% | 21 | ||

| Mannitol | 20% | 22 | ||

| Gelatin | 0.5% | 23 | ||

| Gelatin | 1% | 24 |

| F1 | F2 | F3 | F4 |

| Sucrose 20% | Sucrose 20% | Trehalose 20% | Trehalose 20% |

| Tris 5mM | Histidine 10 mM | Tris 5mM | Histidine 10 mM |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).