Submitted:

27 December 2025

Posted:

29 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Cohort and Imaging Data

2.2. Experimental Design and Comparison Groups

2.3. Measurement Methods and Quality Control

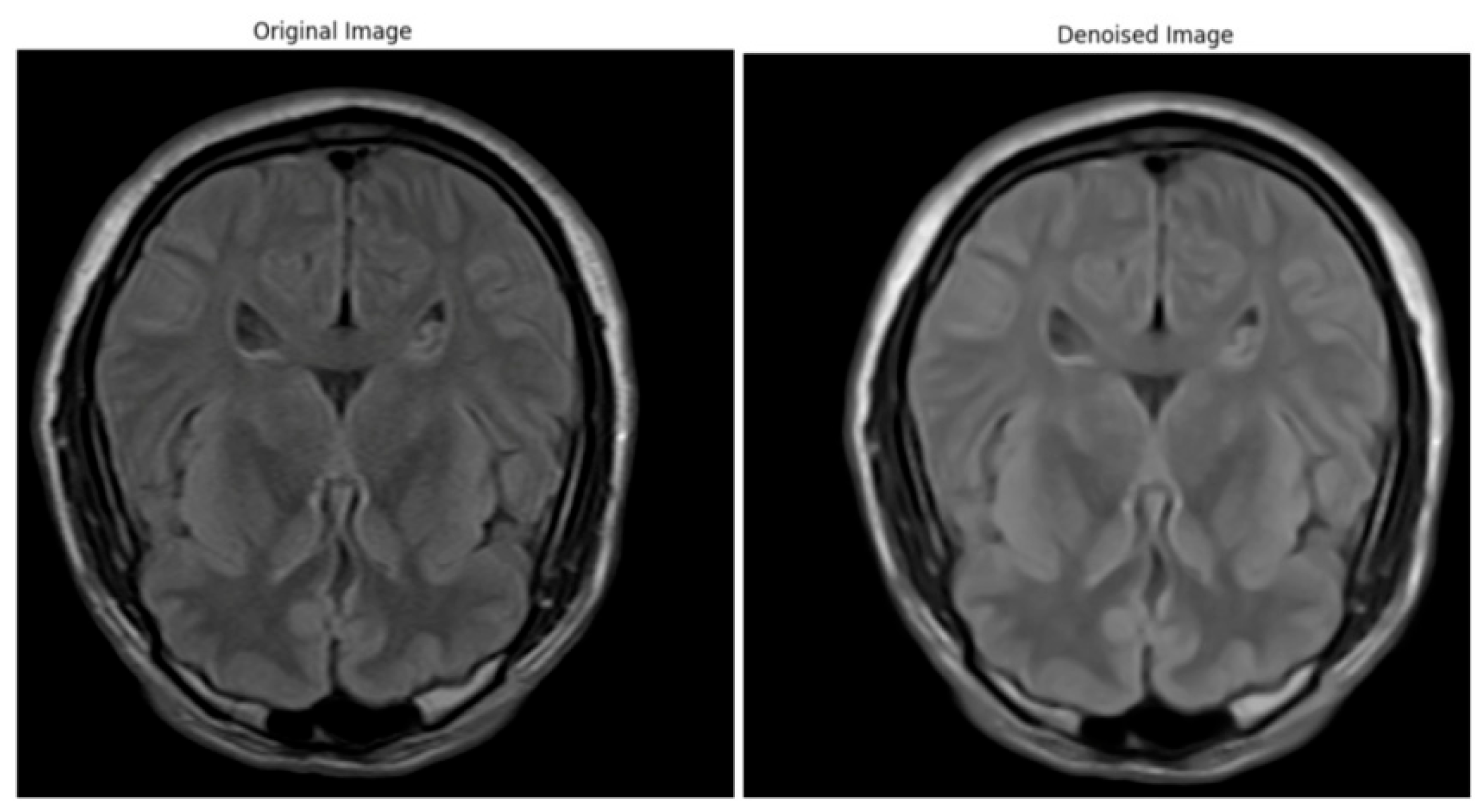

2.4. Data Processing and Model Computation

2.5. Statistical Analysis and Evaluation Metrics

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Segmentation Accuracy on Public Datasets

3.2. Small-Lesion Sensitivity and Lesion-Level Results

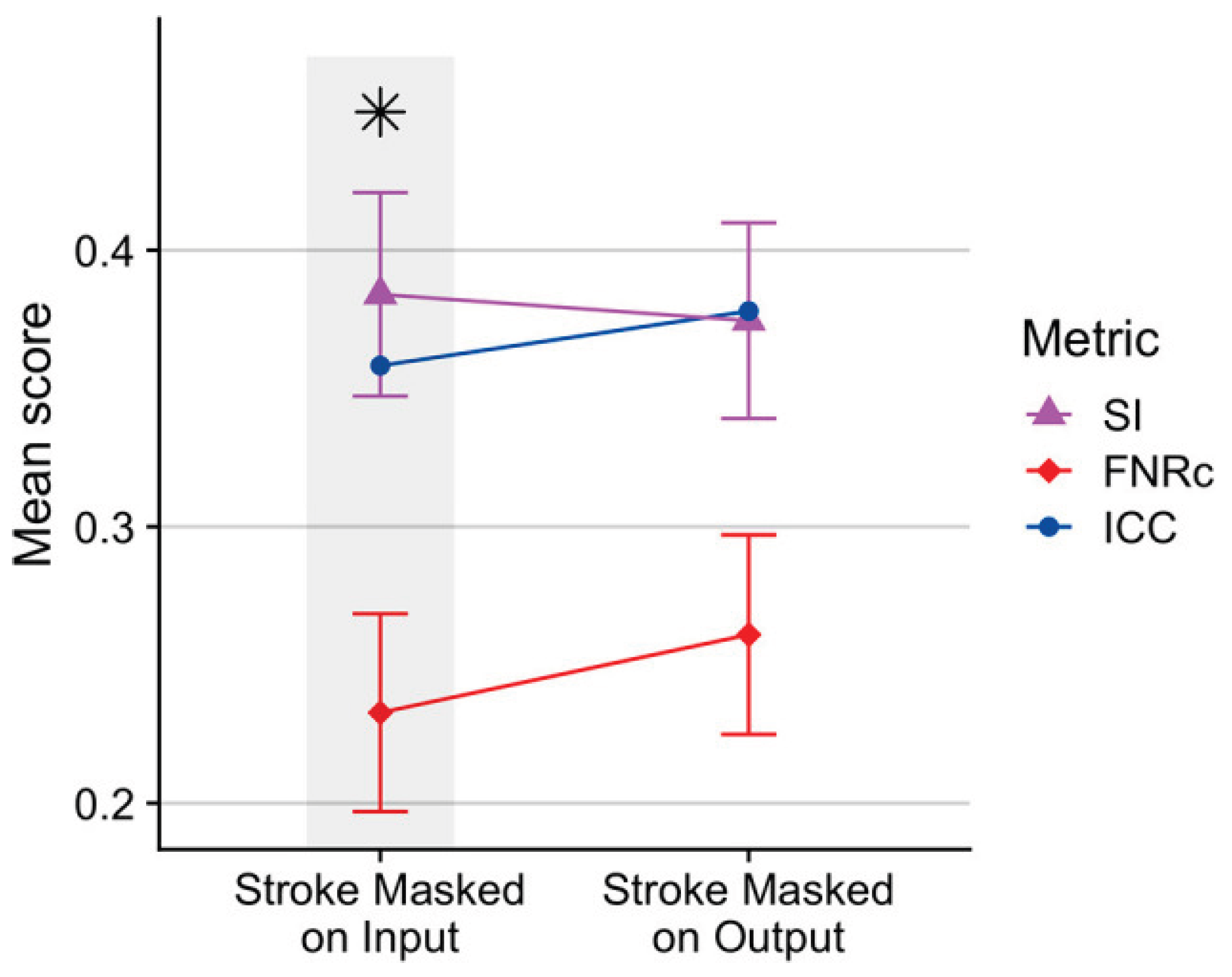

3.3. Cross-Dataset Testing and Clinical Relevance

3.4. Ablation Analysis and Relation to Foundation-Model Research

4. Conclusions

References

- Clèrigues, A.; Valverde, S.; Bernal, J.; Freixenet, J.; Oliver, A.; Lladó, X. Acute ischemic stroke lesion core segmentation in CT perfusion images using fully convolutional neural networks. Comput. Biol. Med. 2019, 115, 103487. [CrossRef]

- Roh, J.; Ryu, D.; Lee, J. CT synthesis with deep learning for MR-only radiotherapy planning: a review. Biomed. Eng. Lett. 2024, 14, 1259–1278. [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y., Yang, Z., Liu, C., Su, Y., Hong, Z., Gong, Z., & Xu, J. (2025). CenterMamba-SAM: Center-Prioritized Scanning and Temporal Prototypes for Brain Lesion Segmentation. arXiv preprint arXiv:2511.01243.

- Wang, Y. Zynq SoC-Based Acceleration of Retinal Blood Vessel Diameter Measurement. Arch. Adv. Eng. Sci. 2025, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Sasidharan, S.M.; Mdletshe, S.; Wang, A. Machine Learning in Stroke Lesion Segmentation and Recovery Forecasting: A Review. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 10082. [CrossRef]

- Gui, H.; Zong, W.; Fu, Y.; Wang, Z. Residual unbalance moment suppression and vibration performance improvement of rotating structures based on medical devices. 2025.

- Hassanzadeh, T.; Sachdev, S.; Wen, W.; Sachdev, P.S.; Sowmya, A. A robust deep learning framework for cerebral microbleeds recognition in GRE and SWI MRI. NeuroImage: Clin. 2025, 48, 103873. [CrossRef]

- Zha, D.; Gamez, J.; Ebrahimi, S.M.; Wang, Y.; Verma, N.; Poe, A.J.; White, S.; Shah, R.; Kramerov, A.A.; Sawant, O.B.; et al. Oxidative stress-regulatory role of miR-10b-5p in the diabetic human cornea revealed through integrated multi-omics analysis. Diabetologia 2025, 69, 198–213. [CrossRef]

- Gurav, U.; Jadhav, S. Prompt-SAM: A Vision-Language and SAM based Hybrid Framework for Prompt-Augmented Zero-Shot Segmentation. Human-Centric Intell. Syst. 2025, 5, 431–449. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wen, Y.; Wu, X.; Wang, L.; Cai, H. Assessing the Role of Adaptive Digital Platforms in Personalized Nutrition and Chronic Disease Management. World J. Innov. Mod. Technol. 2025, 8, 24–31. [CrossRef]

- Chaitanya, K., Erdil, E., Karani, N., & Konukoglu, E. (2020). Contrastive learning of global and local features for medical image segmentation with limited annotations. Advances in neural information processing systems, 33, 12546-12558.

- Wen, Y.; Wu, X.; Wang, L.; Cai, H.; Wang, Y. Application of Nanocarrier-Based Targeted Drug Delivery in the Treatment of Liver Fibrosis and Vascular Diseases. J. Med. Life Sci. 2025, 1, 63–69. [CrossRef]

- Lumetti, L.; Pipoli, V.; Marchesini, K.; Ficarra, E.; Grana, C.; Bolelli, F. Taming Mambas for 3D Medical Image Segmentation. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 89748–89759. [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Liu, S.; Chen, D.; Liu, J.; Wu, J.; Wang, H.; Su, Y.; Kwak, G.; Zuo, X.; Rao, D.; et al. A Two-Pronged Pulmonary Gene Delivery Strategy: A Surface-Modified Fullerene Nanoparticle and a Hypotonic Vehicle. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2021, 60, 15225–15229. [CrossRef]

- Biswas, M., Rahman, S., Tarannum, S. F., Nishanto, D., & Safwaan, M. A. (2025). Comparative analysis of attention-based, convolutional, and SSM-based models for multi-domain image classification (Doctoral dissertation, BRAC University).

- Li, W.; Zhu, M.; Xu, Y.; Huang, M.; Wang, Z.; Chen, J.; Wu, H.; Sun, X. SIGEL: a context-aware genomic representation learning framework for spatial genomics analysis. Genome Biol. 2025, 26, 1–27. [CrossRef]

- Zha, D.; Mahmood, N.; Kellar, R.S.; Gluck, J.M.; King, M.W. Fabrication of PCL Blended Highly Aligned Nanofiber Yarn from Dual-Nozzle Electrospinning System and Evaluation of the Influence on Introducing Collagen and Tropoelastin. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2025, 11, 6657–6670. [CrossRef]

- Kasaraneni, C.K.; Guttikonda, K.; Madamala, R. (2025). Multi-modality Medical (CT, MRI, Ultrasound Etc.) Image Fusion Using Machine Learning/Deep Learning. In Machine Learning and Deep Learning Modeling and Algorithms with Applications in Medical and Health Care (pp. 319-345). Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland.

- Pouramini, A.; Faili, H. Matching tasks to objectives: Fine-tuning and prompt-tuning strategies for encoder-decoder pre-trained language models. Appl. Intell. 2024, 54, 9783–9810. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.