1. Introduction

Transmissible viral proventriculitis (TVP), characterized by proventricular enlargement, ingesta retention in the lumen, and fragility of the gastric isthmus, has become a major issue worldwide in poultry flocks since the 1970s [

1]. TVP is an infectious disease characterized by poor growth, retarded feathering, diarrhoea, passing partially digested feed in the faeces, and increased mortality mostly in broilers aged 21-49 days [

2,

3,

4,

5]. The clinical picture can mimic the runting stunting syndrome (RSS) [

6]. Cases in broiler breeders and layer pullets have also been reported [

7].

Typical macroscopic lesions are enlarged and pale or mottled grey-white proventriculi with a widened isthmus. The organ's wall is thickened, some glands are distended, and a thick white substance can be expelled into the lumen. The mucosa can be reddened. Characteristic histopathological lesions include necrosis of the glandular epithelium accompanied by mild to severe infiltration, predominantly of lymphocytes, macrophages, and plasma cells, as well as hyperplasia of the glandular epithelium, the formation of lymphoid nodules, and occasional fibrosis [

3,

5,

8,

9].

The disease has a profound negative economic impact on the flock production [

10,

11]. Researchers have attempted to identify the aetiology of TVP, and recently, a birnavirus, the chicken proventricular necrosis virus (CPNV) was proposed as the cause of TVP [

1,

12].

Two poultry flocks in Bangladesh—a white layer flock and a coloured meat-type PS—displayed stunted growth and proventricular lesions during on-farm examination. To clarify the underlying cause, proventricular samples were collected from the affected coloured meat-type PS and subjected to histopathological and molecular analyses, with a focus on determining the possible involvement of TVP.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Collection

Suspected cases of TVP were identified in a white layer flock and in a coloured meat-type PS in Bangladesh, based on the presence of RSS-like clinical signs and gross lesions consistent with TVP, including enlarged and pale proventriculi. From the coloured meat-type PS, proventricular samples showing characteristic lesions were collected for laboratory analyses. Tissue specimens were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin for histopathology, and additional samples were applied to an FTA card from the cut surface of four affected proventricular walls for subsequent PCR-based diagnostics.

2.2. Histopathology

The proventricular tissue samples were initially fixed in 10% neutral buffered formaldehyde solution at room temperature. Following fixation, the samples underwent trimming and dehydration through a graded series of ethanol and xylene using an automated tissue processor. The dehydrated specimens were subsequently embedded in paraffin blocks, from which 4 µm thick sections were manually cut and mounted onto glass slides. The paraffin-embedded sections were deparaffinised and rehydrated using xylene and ethanol, respectively. Histological analysis was conducted via routine Haematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) staining, as well as Masson's trichrome staining, both of which were performed on an automated staining system. Slide digitization was performed with a Pannoramic Midi slide scanner (3D Histech LLC, Hungary).

2.3. Molecular Detection of the Virus

The samples received on the FTA card (one card with four samples) were pooled, dissolved in sterile 1X phosphate buffer solution (PBS), and then centrifuged for 5 minutes at 3000 rpm.

Viral RNA was extracted from 200 µl samples using the MagCore® Plus II automated nucleic acid extraction machine (RBC Bioscience, Taiwan) and the MagCore® Viral Nucleic Acid Extraction Kit 202 (RBC Bioscience) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The RNA samples were stored at -80 °C until further analysis.

The samples were analysed by RT-PCR to detect the VP1 gene of CPNV, as described by

GUY et al. in 2011 [

12]. The tests were run on a QIAamplifier 96 instrument (Qiagen, Germany) using the OneStep RT-PCR Kit (Qiagen, Germany) and specific primers (Forward: B2F 5’-CGTAGACCTCGTCCTTCTGC-3’; Reverse: B2R 5’-GGGCGGTAACCATTCAGATA-3). The temperature profile for the reaction was as follows: reverse transcription was 50 °C for 30 min, 95 °C for 15 min, followed by 45 cycles of 95 °C for 30 s, 55 °C for 1 min, 72 °C for 1 min, with a final extension at 72 °C for 10 minutes. We also examined possible coinfections, such as infectious bronchitis virus (IBV) [

13], infectious bursal disease virus (IBDV) [

14], avian reovirus (ARV) [

15], and fowl adenovirus (FAdV) [

16], using conventional PCR and RT–PCR.

The PCR products were visualized by agarose gel electrophoresis. Gel electrophoresis was performed on a 1.8% TopVision Agarose gel (Thermo Fisher Scientific, US) at 120 V for an average of 30 minutes. The PCR products were detected with the DuoVIEW Transilluminator gel documentation system (Cleaver Scientific, US).

2.4. Sequencing and Phylogenetic Analysis

Amplicons of appropriate size were manually excised with a sterile scalpel, and the purification process was performed using the QIAquick Gel Extraction Kit (Qiagen, Germany) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Capillary electrophoresis was performed at a commercial service provider (Eurofins BIOMI Kft., Hungary).

Chromas 2.6.6 software (Technelysium Pty Ltd, Australia) was used to visualize the chromatograms, and the sequences were proofread. The forward and reverse sequences were assembled using the MAFFT version 7 online software, applying the E-INS-I method.

For the phylogenetic analysis, 33 reference CPNV VP1 gene sequences were downloaded from GenBank. Maximum Likelihood (ML) analysis was conducted using the MEGAX software [

17], and a bootstrap analysis with 1000 repetitions was performed to test the support for the branches of the phylogenetic tree.

3. Results

3.1. Clinical Signs and Necropsy Results

3.1.1. White Layer Flock Case

In a floor-reared white layer flock at 5 weeks of age, affected birds exhibited poor growth and intermittent huddling, accompanied by an increase in mortality. Necropsy of clinically impacted birds revealed lesions characteristic of TVP, including proventricular enlargement and pallor (

Figure 1), thickening of the proventricular wall (

Figure 2), and mucosal congestion and haemorrhages (

Figure 3). Mild enteritis and the presence of incompletely digested feed in the faeces were also observed.

3.1.2. Coloured Meat-Type Parent Stock Case

An outbreak consistent with TVP occurred in a flock of approximately 11,000 coloured meat-type PS kept on a floor system at 5 weeks of age. More than 300 birds displayed clinical signs, including growth retardation (

Figure 4), abnormal feathering, and diarrhoea containing undigested feed. The gross lesions closely aligned with the changes observed in the white layer flock, with marked proventricular enlargement and pallor (

Figure 5), thickening of the proventricular wall (

Figure 6), and, in some cases, mucosal congestion and haemorrhages (

Figure 7). Mild enteritis (

Figure 8) and undigested feed within the large intestines (

Figure 9) were also recorded.

3.2. Histology Results

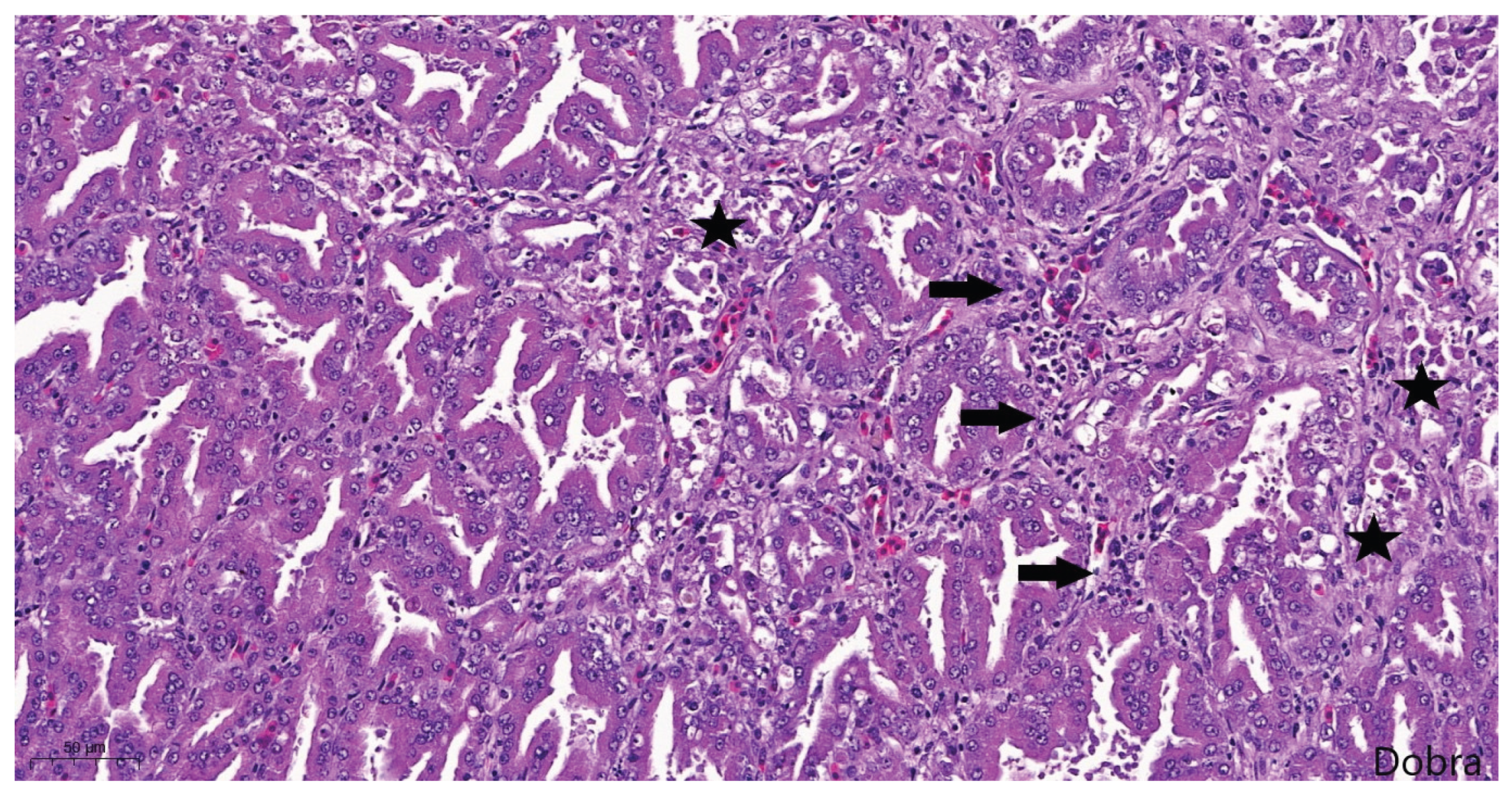

Most proventricular glands exhibited lesions consistent with chronic TVP, including ductal epithelial hyperplasia, epithelial metaplasia, and mild multifocal, lymphocytic infiltration (

Figure 10). Masson's trichrome staining confirmed interstitial fibrosis (

Figure 11). In addition, acute lesions characterized by glandular epithelial degeneration and necrosis with diffuse lymphocytic infiltration were present in some areas (

Figure 12).

3.3. PCR Results

Proventricular samples applied to an FTA card were pooled and subjected to molecular screening. Reverse-transcription PCR was employed to detect the CPNV, IBV, IBDV, and ARV genomes, whereas conventional PCR was used to assess the presence of FAdV. The pooled sample tested positive for CPNV, IBV, IBDV, and ARV, while no amplification indicative of FAdV was observed.

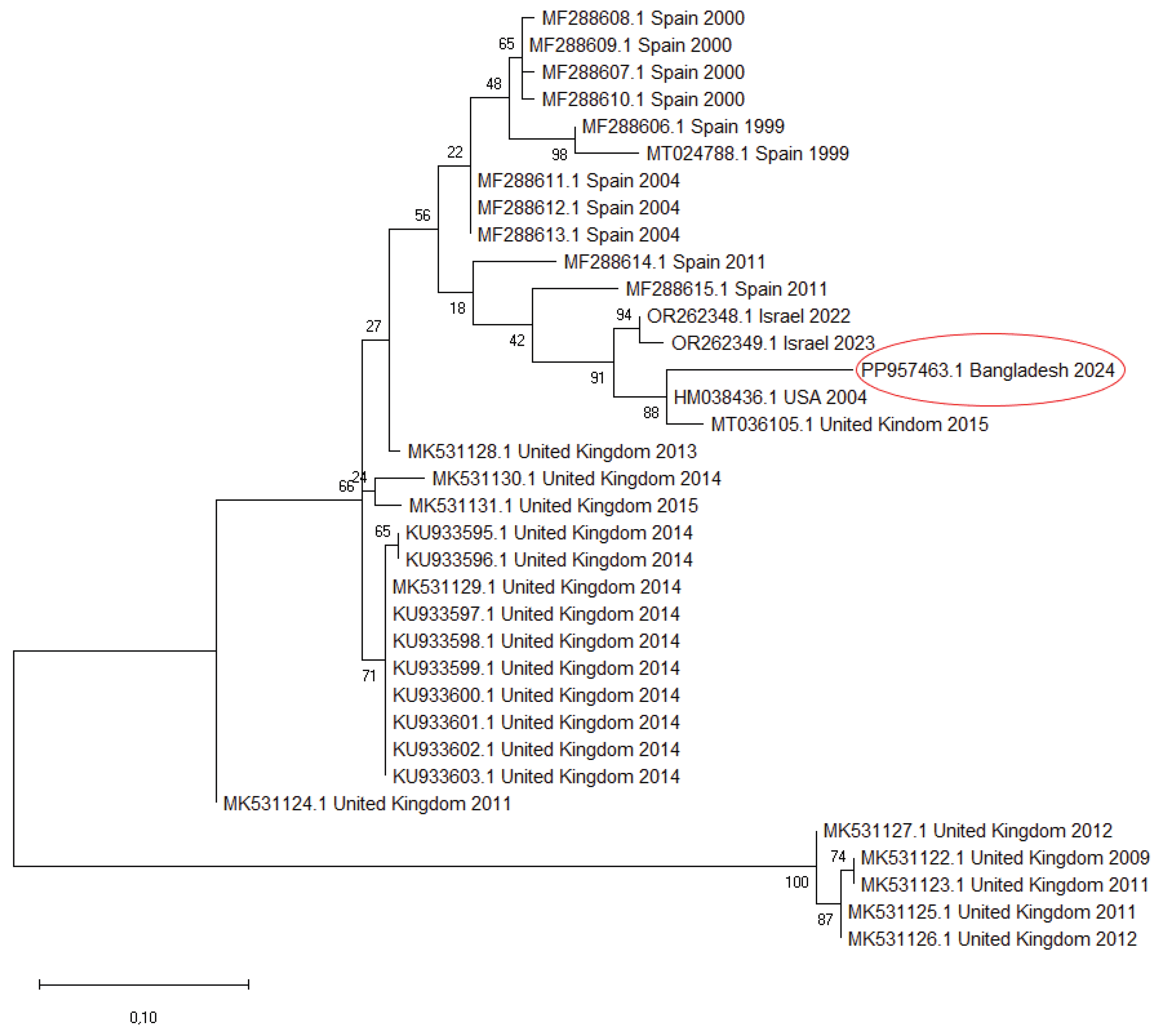

3.4. Phylogenetic Analysis

We sequenced the partial VP1 fragment (171 nt) of CPNV detected in the pooled sample and uploaded it to the GenBank (accession number: PP957463). Partial VP1 sequences were downloaded from the GenBank and compared with each other and with the sequence originating from Bangladesh. Pairwise nucleotide identity values ranged from 63.29–92.40%, with the highest similarity observed between the Bangladesh strain and the USA sequence (HM038436). Alignment of the corresponding amino acid sequences revealed eight characteristic amino acid substitutions across the examined fragment. Starting from the first codon of the sequence, these mutations are: P14S, G17A, T18I, Q21H, K22L, E37V, G38H, and Q/S42L.

A phylogenetic tree was constructed using a set of reference VP1 sequences (

Figure 13). The phylogenetic analysis placed our sequence within the same cluster as the HM038436 strain from the USA and the MT036105 strain from the UK. This subgroup branched separately but clustered with strains from Israel and showed a relatively close relationship to sequences from Spain. The other CPNV sequences collected in the UK formed distinct clusters with strong bootstrap support, indicating multiple lineages circulating there.

4. Discussion

This study documents the first confirmed detection of CPNV associated with TVP in Bangladesh. TVP has been reported in multiple poultry-producing regions worldwide [

4,

8,

9,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27], yet reports from South Asia remain scarce, and its occurrence is likely underrecognized. The clinical signs observed in both affected flocks—including growth retardation, poor feathering, and diarrhoea—were consistent with previous descriptions of TVP in commercial poultry [

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

11]. Likewise, the gross lesions, particularly proventricular enlargement, pallor, and mucosal congestion, corresponded well with the characteristic pathological changes reported in earlier cases [

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

11].

Histopathological evaluation of proventricular tissues further supported a diagnosis of TVP [

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

11]. The lesions observed in this study, including glandular epithelial degeneration and necrosis, mononuclear infiltration, epithelial hyperplasia, metaplasia, and varying degrees of interstitial fibrosis, align closely with the classical microscopic features described in experimental infections with TVP-affected proventricular homogenates [

2,

4,

10,

28] and CPNV [

29]. The concurrent presence of both acute and chronic lesions suggests that the infection in the flock may have persisted or occurred in multiple waves.

Molecular analysis confirmed CPNV in the sampled proventricular tissue, strengthening its etiological association with the observed lesions. Additional viral nucleic acids, including those of IBV, IBDV, and ARV, were also detected by RT-PCR. However, the flock had been vaccinated with live IBDV (hatchery-administered immune complex vaccine, GUMBOHATCH), IBV (administered at the hatchery and again at 4 days of age on the farm; Nobilis 4/91), and ARV (administered at 9 days of age; Nobilis Reo 1133) vaccines prior to sampling, making it plausible that the detected nucleic acids originated from vaccine strains rather than field infections. This limitation highlights the difficulty of interpreting PCR results in the context of recent vaccination and reinforces the importance of integrating molecular findings with pathological evidence when diagnosing TVP.

The majority of currently available CPNV sequences correspond to the same 171 nt long VP1 fragment, which limits the strength and reliability of comparative genetic analyses. In our study, the strain from Bangladesh clustered with strains from the USA and the UK, forming a subgroup that branched separately yet remained closely related to sequences from Israel and Spain. This suggests that related CPNV lineages circulate across geographically distant regions. In contrast, most UK sequences formed distinct clusters that reflect their collection dates, indicating the co-circulation of multiple independent lineages over time within a single country. Pairwise nucleotide identity among all sequences further supports the virus’s moderate genetic diversity. Eight characteristic amino acid substitutions were detected in our strain. Our results provide an initial overview of CPNV genetic relationships, but future studies employing complete VP1 or full genome sequences are needed to achieve a more accurate understanding of viral evolution and epidemiological patterns.

The emergence of TVP in Bangladesh carries practical implications for poultry health management. As the poultry sector expands, early recognition of underdiagnosed conditions such as TVP becomes increasingly important. The clinical presentation of TVP can mimic RSS and other causes of poor growth, leading to misdiagnosis and suboptimal control measures. Routine inclusion of proventricular examination during necropsy, supported by histopathology and targeted molecular testing, may improve diagnostic accuracy. Furthermore, enhanced surveillance is warranted to clarify the prevalence and epidemiological patterns of CPNV in the region, not only in broiler operations—where TVP is most frequently reported—but also in layer and parent stock flocks.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, the present study confirms, for the first time, the presence of CPNV-associated TVP in Bangladesh. The combined gross, histopathological, and molecular findings underscore the importance of CPNV as a relevant pathogen in cases of growth retardation and proventricular pathology. Future studies should aim to clarify transmission dynamics, evaluate potential production impacts, and explore effective prevention strategies to mitigate the disease burden in regional poultry farms.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.F.D. and L.K.; investigation, L.K., P.F.D., L.D., K.S. and B.I.; resources, M.M..; data curation, L.D.; writing—original draft preparation, L.K. and P.F.D.; writing—review and editing, L.K., P.F.D., L.D., R.P. and R.H.; visualization, P.F.D. and B.I.; supervision, M.M.; project administration, P.F.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The identified partial VP1 sequence of CPNV is available in the GenBank under accession number PP957463.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful for the support of their corresponding organizations.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Guy, J.S.; West, A.M.; Fuller, F.J. Physical and genomic characteristics identify chicken proventricular necrosis virus (R11/3 virus) as a novel birnavirus. Avian Dis. 2011, 55, 2–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayyari, G.R.; Huff, W.E.; Balog, J.M.; Rath, N.C.; Beasley, J.N. Experimental reproduction of proventriculitis using homogenates of proventricular tissue. Poult. Sci. 1995, 74, 1799–1809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hafner, S.; Guy, J.S. Proventriculitis and proventricular dilatation of broiler chickens. In Diseases of Poultry, 13th ed.; Swayne, D.E., Glisson, J.R., McDouglald, L.R., Nolan, L.K., Suarez, D.L., Nair, V.L., Eds.; Wiley-Blackwell: United States, 2013; pp. 1328–1332. [Google Scholar]

- Kouwenhoven, B.; Davelaar, F.G.; Van Walsum, J. Infectious proventriculitis causing runting in broilers. Avian Pathol. 1978, 7, 183–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodwin, M.A.; Hafner, S.; Bounous, D.I.; Latimer, K.S.; Player, E.C.; Niagro, F.D.; Campagnoli, R.P.; Brown, J. Viral proventriculitis in chickens. Avian Pathol. 1996, 25, 369–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noiva, R.; Guy, J.S.; Hauck, R.; Shivaprasad, H.L. Runting stunting syndrome associated with transmissible viral proventriculitis in broiler chickens. Avian Dis. 2015, 59, 384–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marusak, R.A.; West, M.A.; Davis, J.F.; Fletcher, O.J.; Guy, J.S. Transmissible Viral Proventriculitis Identified in Broiler Breeder and Layer Hens. Avian Dis. Dig. 2012, 7, e39–e40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauck, R.; Stoute, S.; Senties-Cue, C.G.; Guy, J.S.; Shivaprasad, H.L. A Retrospective Study of Transmissible Viral Proventriculitis in Broiler Chickens in California: 2000–18. Avian Dis. 2020, 64, 525–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grau-Roma, L.; Schock, A.; Nofrarías, M.; Ali Wali, N.; De Fraga, A.P.; Garcia-Rueda, C.; De Brot, S.; Majó, N. Retrospective study on transmissible viral proventriculitis and chicken proventricular necrosis virus (CPNV) in the UK. Avian Pathol. 2020, 49, 99–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guy, J.S.; Barnes, H.J.; Smith, L.; Owen, R.; Fuller, F.J. Partial Characterization of an Adenovirus-Like Virus Isolated from Broiler Chickens with Transmissible Viral Proventriculitis. Avian Dis. 2005, 49, 344–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dormitorio, T.V.; Giambrone, J.J.; Hoerr, F.J. Transmissible proventriculitis in broilers. Avian Pathol. 2007, 36, 87–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guy, J.S.; West, M.A.; Fuller, F.J.; Marusak, R.A.; Shivaprasad, H.L.; Davis, J.L.; Fletcher, O.J. Detection of chicken proventricular necrosis virus (R11/3 virus) in experimental and naturally occurring cases of transmissible viral proventriculitis with the use of a reverse transcrip-tase-PCR procedure. Avian Dis. 2011, 55, 70–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sellers, H.S.; Koci, M.D.; Linnemann, E.; Kelley, L.A.; Schultz-Cherry, S. Development of a Multiplex Reverse Transcription–Polymerase Chain Reaction Diagnostic Test Specific for Turkey Astrovirus and Coronavirus. Avian Dis. 2004, 48, 531–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackwood, D.J.; Sommer-Wagner, S. Genetic characteristics of infectious bursal disease viruses from four continents. Virology 2007, 365, 369–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pantin-Jackwood, M.J.; Day, J.M.; Jackwood, M.W.; Spackman, E. Enteric Viruses Detected by Molecular Methods in Commercial Chicken and Turkey Flocks in the United States Between 2005 and 2006. Avian Dis. 2008, 52, 235–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanson, L.A.; Rudis, M.R.; Vasquez-Lee, M.; Montgomery, R.D. A broadly applicable method to characterize large DNA viruses and adenoviruses based on the DNA polymerase gene. Virol. J. 2006, 3, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Stecher, G.; Li, M.; Knyaz, C.; Tamura, K. MEGA X: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis across Computing Platforms. Mol Biol Evol. 2018, 35, 1547–1549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leão, P.A.; Amaral, C.I.; Santos, W.H.M.; Moreira, M.V.L.; De Oliveira, L.B.; Costa, E.A.; Resende, M.; Wenceslau, R.; Ecco, R. Retrospective and prospective studies of transmissible viral proventriculitis in broiler chickens in Brazil J. Vet. Diagn. Investig. 2021, 33, 605–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marguerie, J.; Leon, O.; Albaric, O.; Guy, J. S.; Guerin, J. Birnavirus-associated proventriculitis in French broiler chickens. Vet. Rec. 2011, 169, 394–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coman, A.; Rusvai, M.; Demeter, Z.; Palade, E.A.; Cătană, N. Histopathological changes of transmissible viral proventriculitis in broiler flocks. Bull. Univ. Agric. Sci. Vet. Med. Cluj-Napoca-Vet. Med. 2011, 68, 93–95. Available online: https://journals.usamvcluj.ro/index.php/veterinary/article/view/6882 (accessed on 16 December 2025).

- Allawe, A.B.; Abbas, A.A.; Taha, H.Z.; Odisho, S.M. Detection of transmissible viral proventriculitis in Iraq. J. Entomol. Zool. Stud. 2017, 5, 974–978. Available online: https://www.entomoljournal.com/archives/2017/vol5issue5/PartM/5-4-48-219.pdf (accessed on 16 December 2025).

- Śmiałek, M.; Gesek, M.; Śmiałek, A.; Koncicki, A. Identification of transmissible viral proventriculitis (TVP) in broiler chickens in Poland. Pol. J. Vet. Sci. 2017, 20, 417–420. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28865208/ (accessed on 16 December 2025). [CrossRef]

- Grau-Roma, L.; Marco, A.; Martínez, J.; Chaves, A.; Dolz, R.; Majó, N. Infectious bursal disease-like virus in cases of transmissible viral proventriculitis. Vet. Rec. 2010, 167, 836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Jiang, Y.; Low, S.; Wang, Z.; Nam, S.J.; Liu, W.; Kwang, J. Characterization of three infectious bronchitis virus isolates from China associated with proventriculus in vaccinated chickens. Avian Dis. 2001, 45, 416–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.-R.; Yoon, S.-J.; Lee, H.S.; Kwon, Y.-K. Identification of a picornavirus from chickens with transmissible viral proventriculitis using metagenomic analysis. Arch. Virol. 2015, 160, 701–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dervović, J.; Goletić, Š.; Šeho-Alić, A.; Prašović, S.; Goletić, T.; Alić, A. Transmissible Viral Proventriculitis in Broiler Chickens from Bosnia and Herzegovina. Pathogens 2025, 14, 438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gornatti-Churria, C.D.; Majó, N.; Macías-Rioseco, M.; Valle, R.M.; García, P.A.; Jerry, C.F. Diagnostic Findings of Transmissible Viral Proventriculitis Associated with Chicken Proventricular Necrosis Virus in Processed Broiler Chickens in Argentina. Viruses 2025, 17, 519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Śmiałek, M.; Gesek, M.; Dziewulska, D.; Niczyporuk, J.S.; Koncicki, A. Transmissible Viral Proventriculitis Caused by Chicken Proventricular Necrosis Virus Displaying Serological Cross-Reactivity with IBDV. Animals 2020, 11, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guy, J.S.; Smith, L.G.; Evans, M.E.; Barnes, H.J. Experimental Reproduction of Transmissible Viral Proventriculitis by Infection of Chickens with a Novel Adenovirus-Like Virus (Isolate R11/3). Avian Dis. 2007, 51, 58–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Figure 1.

Layer chicken: enlarged and pale proventriculus.

Figure 1.

Layer chicken: enlarged and pale proventriculus.

Figure 2.

Layer chicken: thickened proventricular wall.

Figure 2.

Layer chicken: thickened proventricular wall.

Figure 3.

Layer chicken: congestion and haemorrhages in the proventricular mucosa.

Figure 3.

Layer chicken: congestion and haemorrhages in the proventricular mucosa.

Figure 4.

Meat-type PS chicken: growth retardation and weight loss.

Figure 4.

Meat-type PS chicken: growth retardation and weight loss.

Figure 5.

Meat-type PS chicken: proventricular enlargement with pallor.

Figure 5.

Meat-type PS chicken: proventricular enlargement with pallor.

Figure 6.

Meat-type PS chicken: thickened proventricular wall.

Figure 6.

Meat-type PS chicken: thickened proventricular wall.

Figure 7.

Meat-type PS chicken: congestion and haemorrhages in the proventricular mucosa.

Figure 7.

Meat-type PS chicken: congestion and haemorrhages in the proventricular mucosa.

Figure 8.

Meat-type PS chicken: mild enteritis.

Figure 8.

Meat-type PS chicken: mild enteritis.

Figure 9.

Meat-type PS chicken: undigested feed in the large intestine.

Figure 9.

Meat-type PS chicken: undigested feed in the large intestine.

Figure 10.

Meat-type PS chicken, proventriculus: epithelial hyperplasia and metaplasia, mild, multifocal, lymphocytic infiltration of the interstitium (encircled), Haematoxylin-Eosin staining, scale bar = 50 µm.

Figure 10.

Meat-type PS chicken, proventriculus: epithelial hyperplasia and metaplasia, mild, multifocal, lymphocytic infiltration of the interstitium (encircled), Haematoxylin-Eosin staining, scale bar = 50 µm.

Figure 11.

Meat-type PS chicken, proventriculus: interstitial fibrosis (proliferated connective tissue fibres appear in blue), Masson's trichrome staining, scale bar = 200 µm.

Figure 11.

Meat-type PS chicken, proventriculus: interstitial fibrosis (proliferated connective tissue fibres appear in blue), Masson's trichrome staining, scale bar = 200 µm.

Figure 12.

Meat-type PS chicken, proventriculus: degeneration, necrosis and detachment of glandular epithelial cells (stars), and mild, diffuse, lymphocytic infiltration of the interstitium (arrows), Haematoxylin-Eosin staining, scale bar = 50 µm.

Figure 12.

Meat-type PS chicken, proventriculus: degeneration, necrosis and detachment of glandular epithelial cells (stars), and mild, diffuse, lymphocytic infiltration of the interstitium (arrows), Haematoxylin-Eosin staining, scale bar = 50 µm.

Figure 13.

Phylogenetic tree based on the Maximum Likelihood method for 35 partial (171 nt) VP1 CPNV sequences.

Figure 13.

Phylogenetic tree based on the Maximum Likelihood method for 35 partial (171 nt) VP1 CPNV sequences.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).