1. Introduction

Machine Translation (MT) stands as a cornerstone task in Natural Language Processing (NLP), and its continuous improvement is pivotal for fostering global communication and knowledge exchange [

1]. Recent advancements in Large Language Models (LLMs) have significantly propelled MT capabilities, enabling more fluent and accurate translations across diverse language pairs [

2]. However, fine-tuning these powerful LLMs typically demands extensive quantities of high-quality parallel data, which remains a scarce resource for many low-resource languages.

To circumvent the limitations of data scarcity, Preference Optimization (PO) [

3], particularly Direct Preference Optimization (DPO) [

3], has emerged as a compelling paradigm. PO methods allow models to learn from human or automated preferences over multiple candidate translations, thereby enhancing translation quality without requiring explicit reward model training. Existing preference optimization techniques, such as Reward-based Supervised Optimization (RSO) [

4], Reward-Score DPO (RS-DPO) [

5], and the recently proposed Confidence-Reward Driven Preference Optimization (CRPO) [

6], primarily concentrate on efficiently identifying "valuable" samples. These methods typically prioritize candidates with the highest reward scores or those combining high reward with strong generation confidence, as seen in CRPO’s innovative approach to leverage both metrics for more precise sample identification and improved data efficiency.

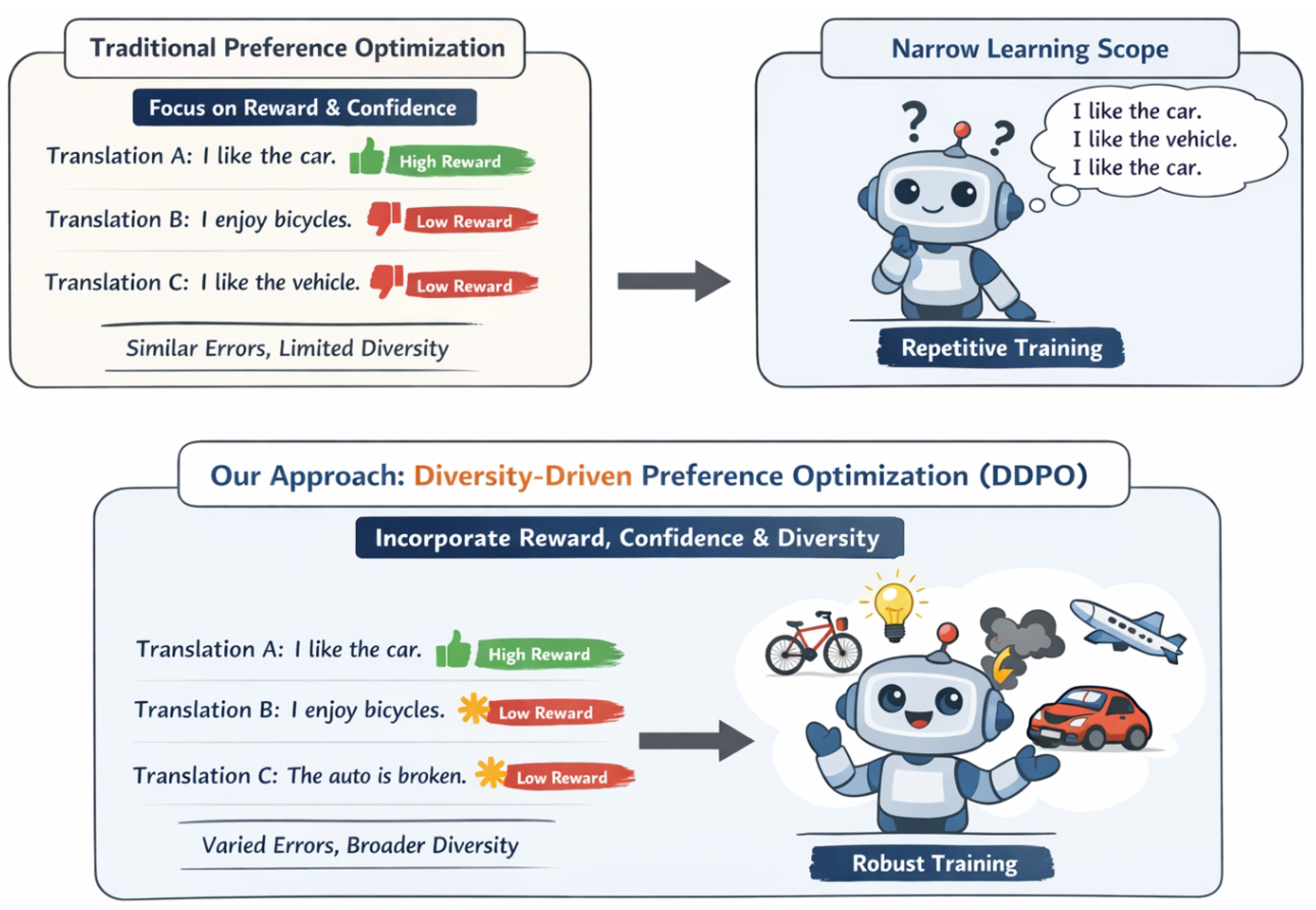

Figure 1.

Unlike reward-and-confidence-only preference optimization that yields low-diversity pairs and repetitive learning signals, DDPO selects a diverse dispreferred translation to provide richer contrasts and improve robustness in machine translation.

Figure 1.

Unlike reward-and-confidence-only preference optimization that yields low-diversity pairs and repetitive learning signals, DDPO selects a diverse dispreferred translation to provide richer contrasts and improve robustness in machine translation.

Despite the successes of these approaches, we observe a critical limitation: by singularly focusing on selecting the "best" candidates based on reward and confidence, existing methods may inadvertently overlook the crucial aspect of diversity among candidate translations. This overemphasis on optimality can lead to models repetitively learning similar error types or correct syntactic/semantic variants during fine-tuning. Consequently, this might constrain the model’s generalization capabilities, limit its exploration of a broader spectrum of translation strategies, and potentially result in overfitting to specific patterns. This study aims to address this inherent challenge by introducing a novel approach, Diversity-Driven Preference Optimization (DDPO). Our goal is to strategically integrate diversity considerations into the preference sample selection process, alongside reward and confidence, thereby enhancing translation performance, model robustness, and generalization capacity.

Our proposed method, DDPO, fundamentally redefines the selection of preferred () and dispreferred () translation pairs. While is still chosen for its high reward and confidence, DDPO’s core innovation lies in the selection of . Instead of simply picking the second-best or lowest-reward candidate, DDPO actively seeks an that, while having a lower reward than and reasonable confidence, exhibits the maximal semantic or syntactic diversity from . This ensures that each preferred pair provides a richer, more informative learning signal, contrasting a high-quality translation with a meaningfully different yet plausible sub-optimal one. By doing so, DDPO encourages the model to learn finer-grained preference boundaries and to explore a wider translation space, mitigating over-reliance on specific linguistic patterns. The selected pairs are then used to fine-tune the base LLM (e.g., ALMA-7B or NLLB-1.3B) using DPO, with only LoRA parameters updated for computational efficiency.

To rigorously evaluate DDPO, we conduct comprehensive experiments using source sentences from the widely recognized FLORES-200 dataset [

7] for constructing our preference training set, generating 64 candidate translations per source sentence. Reward scores for these candidates are derived from state-of-the-art reference-free MT evaluation models, specifically

Unbabel/XCOMET-XL [

8] and

Unbabel/wmt23-cometkiwi-da-xl [

8]. Our method is benchmarked against strong baselines, including various DPO variants and the sophisticated CRPO, across 10 diverse translation directions from the WMT21 [

9] and WMT22 [

10] test sets. Our experimental results, using ALMA-7B (a decoder-only LLM) and NLLB-1.3B (an encoder-decoder model) with LoRA fine-tuning, demonstrate that DDPO consistently outperforms CRPO and other baselines across multiple evaluation metrics (KIWI22, COMET22, XCOMET, KIWI-XL), achieving new state-of-the-art performance. This improvement underscores the effectiveness of integrating diversity into preference optimization for machine translation.

Our primary contributions are summarized as follows:

We identify and address the overlooked issue of lacking diversity in preference sample selection for machine translation, proposing a novel Diversity-Driven Preference Optimization (DDPO) method.

We introduce a sophisticated sample selection strategy for DDPO that actively maximizes the semantic or syntactic diversity between preferred () and dispreferred () translations, while maintaining crucial reward and confidence considerations.

We empirically demonstrate that DDPO consistently achieves superior translation quality and enhanced model robustness compared to existing state-of-the-art preference optimization techniques across multiple metrics and two distinct LLM architectures (ALMA-7B and NLLB-1.3B).

2. Related Work

2.1. Preference Optimization and Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback

Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback (RLHF) aligns LLMs with human preferences through SFT, reward modeling, and policy optimization. Preference optimization broadly covers techniques using comparative feedback to improve model behavior.

The RLHF pipeline begins with

Supervised Fine-tuning (SFT), training LMs on demonstrations. Parameter-efficient methods like prefix-tuning [

11] and fine-grained distillation for tasks like long document retrieval [

12] are used for adaptation.

Reward Modeling approximates human preferences into a scalar reward, often via

Pairwise Ranking. Jiang et al. [

13] apply pairwise ranking, while Zhou et al. [

14] emphasize robust rankers. Sun et al. [

15] focus on explicit reward functions.

Contrastive Learning also aids robust reward models by discerning preferred outcomes [

16].

Finally,

Policy Optimization fine-tunes the SFT-trained LM with RL to maximize reward. Deng et al. [

4] use RLPrompt for discrete prompt optimization.

Preference Optimization (PO) learns from diverse feedback, with Pryzant et al. [

3] proposing Automatic Prompt Optimization (APO).

Reward-based Learning guides model behavior, as seen in Zhang et al. [

17]’s RL for active example selection. Tian et al. [

18] also evaluated calibrated confidence scores from RLHF models. Overall, preference optimization and RLHF rely on conditioning, preference modeling, and policy refinement.

2.2. Large Language Models for Machine Translation and Evaluation

Machine Translation (MT) evolved from NMT (e.g., architecture [

19], beam search [

20,

21]) to LLMs. LLMs significantly impacted MT, offering strong translation without explicit parallel data. Effective LLM use involves strategies like prompting [

22] and fine-tuning [

2] for task adaptation, including low-resource and multilingual settings [

23]. Models also expand into multimodal domains, like visual in-context learning for vision-language models [

24].

Reliable MT evaluation is crucial for LLM outputs. While [

22] used MT metrics and human evaluation, efficient, reference-scarce evaluation is needed [

25]. Quality Estimation (QE) predicts translation quality without human reference, with LLM training data documentation [

26] impacting QE. These studies track MT’s evolution and rigorous evaluation.

2.3. Broader Applications and Methodologies in AI

LLMs and advanced AI extend beyond NLP, impacting diverse scientific and engineering disciplines. For instance, computational biology employs foundation language models for single-cell analysis, understanding cellular mechanisms and multi-omic data via methods like semi-supervised knowledge transfer [

27,

28,

29].

In intelligent transportation, advanced decision-making frameworks for autonomous driving are explored, including enhanced mean field games, uncertainty-aware navigation, and scenario-based decision-making surveys [

30,

31,

32].

Concurrently, computer vision advancements, like quality-aware dynamic memory for video object segmentation and open-vocabulary segmentation with semantic-assisted calibration, continue to push visual understanding [

33,

34,

35].

AI principles also address industrial and economic challenges. Supply chain management uses Bayesian networks for disruption probability and foundation time-series models for resilience [

36,

37]. FinTech develops real-time threat identification systems using federated learning to secure API interactions [

38].

3. Method

Our proposed method, Diversity-Driven Preference Optimization (DDPO), is designed to enhance the fine-tuning of machine translation models by integrating diversity considerations into the preference sample selection process. DDPO departs from conventional preference optimization by not only prioritizing high-reward and high-confidence translations but also by strategically ensuring semantic or syntactic diversity within selected preferred and dispreferred pairs. This approach aims to provide richer, more informative learning signals, thereby improving model robustness and generalization, and mitigating potential overfitting to minor quality differences that lack significant semantic contrast.

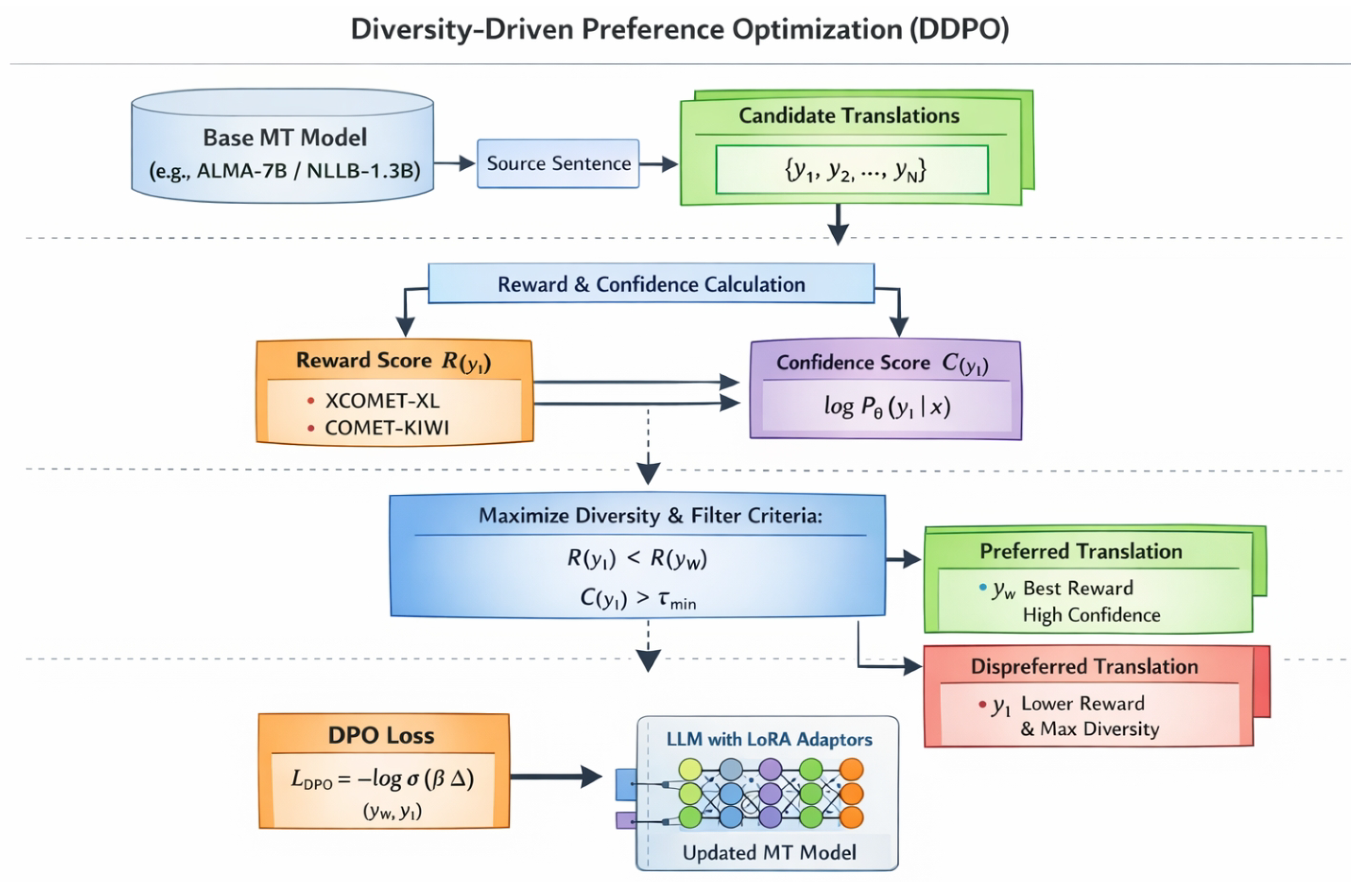

Figure 2.

Overview of Diversity-Driven Preference Optimization (DDPO) for machine translation. Given a source sentence, the base MT model generates multiple candidate translations, which are scored by reward and confidence models. DDPO selects the preferred translation with the highest reward and a dispreferred translation that maximizes semantic diversity under reward and confidence constraints, and optimizes the model using the DPO objective with LoRA-based fine-tuning.

Figure 2.

Overview of Diversity-Driven Preference Optimization (DDPO) for machine translation. Given a source sentence, the base MT model generates multiple candidate translations, which are scored by reward and confidence models. DDPO selects the preferred translation with the highest reward and a dispreferred translation that maximizes semantic diversity under reward and confidence constraints, and optimizes the model using the DPO objective with LoRA-based fine-tuning.

3.1. Overview of DDPO

DDPO operates by refining the process of constructing preference pairs , where x is the source sentence, is the preferred (winning) translation, and is the dispreferred (losing) translation. For a given source sentence x, we first generate a set of N candidate translations. Subsequently, for each candidate, we compute its reward score and generation confidence. The pivotal innovation of DDPO lies in its sophisticated sample selection strategy for , which actively seeks to maximize diversity with while adhering to established reward and confidence criteria. By intentionally selecting a dispreferred translation that is semantically distinct from the preferred one, DDPO encourages the model to learn more robust preference boundaries, preventing it from collapsing onto superficial differences. These diversity-aware pairs are then used to fine-tune the base machine translation model using the Direct Preference Optimization (DPO) objective, specifically updating low-rank adaptation (LoRA) parameters for efficiency.

3.2. Candidate Translation Generation

For each source sentence x from the training dataset (e.g., FLORES-200), we leverage a pre-trained base machine translation model (such as ALMA-7B or NLLB-1.3B) to generate a set of N candidate translations. In our experiments, we set to provide a sufficiently diverse pool for subsequent selection. This generation process typically employs decoding strategies like beam search or nucleus sampling to explore multiple translation hypotheses, ensuring that the candidate pool reflects the generative capabilities and potential error modes of the base model.

3.3. Reward and Confidence Calculation

To inform the preference selection, each candidate translation is evaluated based on two primary metrics: reward score and generation confidence.

3.3.1. Reward Score

The reward score

quantifies the quality of a candidate translation

with respect to the source sentence

x. We employ state-of-the-art reference-free machine translation evaluation models to assign these scores. Specifically, we use ‘Unbabel/XCOMET-XL’ and ‘Unbabel/wmt23-cometkiwi-da-xl’. These models are chosen for their strong correlation with human judgments and their ability to provide robust quality assessments without requiring reference translations. The final reward score for

is computed as the average of the scores from these two models:

This averaging helps to provide a more robust and comprehensive assessment of translation quality, leveraging the complementary strengths of different evaluation paradigms.

3.3.2. Generation Confidence

The generation confidence

reflects the likelihood that the base model produced the translation

. This is typically approximated by the log-likelihood of the translation given the source sentence

x and the current model parameters

:

A higher log-likelihood indicates greater confidence from the model in generating that specific translation. This metric is crucial for distinguishing between plausible errors or sub-optimal translations (which the model generated with reasonable confidence) and incoherent or malformed outputs (which might have very low confidence). By incorporating confidence, we ensure that the dispreferred translations are actual outputs of the model, albeit flawed, rather than random noise.

3.4. Diversity Measurement

The core distinguishing feature of DDPO is its explicit consideration of diversity between candidate translations. For any two candidate translations

, we quantify their semantic diversity

. This is achieved by first mapping each translation to a dense embedding space using a pre-trained sentence embedding model (e.g., Sentence-BERT). The semantic similarity between

and

is then calculated using cosine similarity of their embedding vectors. The diversity score is defined as:

where

denotes the sentence embedding function. A higher

value indicates greater semantic dissimilarity, thus higher diversity. This approach focuses on capturing global semantic differences, which is crucial for ensuring that the preferred and dispreferred translations offer distinct learning signals. While alternative metrics like BERTScore could be adapted to measure diversity, focusing on token-level alignment, Sentence-BERT is chosen for its efficiency in computing sentence-level similarities, which aligns well with the goal of identifying overall semantic variance.

3.5. DDPO Preference Sample Selection Strategy

This strategy is central to DDPO. Given the set of candidate translations for a source sentence x, along with their calculated reward scores , generation confidences , and pairwise diversity scores , we construct the preference pair as follows:

3.5.1. Selection of Preferred Translation ()

Similar to existing preference optimization methods, we select the preferred translation

as the candidate with the highest reward score among all candidates in

:

This ensures that

consistently represents the best available translation according to our chosen reward models, providing a clear positive example for the fine-tuning process.

3.5.2. Selection of Dispreferred Translation ()

This is where DDPO introduces its primary innovation. Instead of simply selecting a translation based solely on its reward (e.g., the second-best candidate or the lowest-reward candidate), we aim to find a that fulfills three critical conditions simultaneously. First, its reward score must be lower than that of , ensuring it is indeed a less desirable translation. Second, its generation confidence must be above a predefined minimum threshold . This condition is vital to ensure that is a plausible, albeit sub-optimal, translation rather than mere noise or gibberish that the model barely understood how to generate. This prevents the model from learning to avoid completely nonsensical outputs, which are less informative than well-formed but inferior translations. Finally, must exhibit the maximal diversity with among all candidates satisfying the first two conditions. This diversity criterion is key to providing a rich learning signal, forcing the model to distinguish between the preferred translation and a semantically different, yet confidently generated, inferior one.

Formally, we first define a subset of eligible dispreferred candidates

:

Then,

is selected from

by maximizing its diversity with

:

This strategy ensures that the model is exposed to a meaningful contrast: it learns not only what the best translation is (

) but also how it differs significantly from a reasonably confident, yet distinctively sub-optimal, alternative (

). This encourages the model to learn more robust preference boundaries and to explore a broader translation space beyond mere superficial corrections, fostering better generalization.

3.6. DPO Fine-tuning with DDPO Samples

The preference pairs

generated by the DDPO selection strategy are then used to fine-tune the base large language model. We adopt the Direct Preference Optimization (DPO) framework as our fine-tuning objective. DPO directly optimizes the policy model to align with the preferences without requiring an explicit reward model, offering a simpler and more stable training procedure compared to reinforcement learning from human feedback (RLHF). The DPO loss function for a given pair

is:

where

are the parameters of the fine-tuned model,

is the probability assigned by the current model,

is the probability assigned by a frozen reference model (e.g., the initial base model),

is the sigmoid function, and

is a hyperparameter controlling the strength of the preference. By optimizing this objective, the model learns to assign higher probabilities to preferred translations (

) and lower probabilities to dispreferred translations (

) relative to the reference model.

For computational efficiency and to prevent catastrophic forgetting, we implement DPO fine-tuning using the LoRA (Low-Rank Adaptation) technique. This means that only the parameters of the LoRA adapters are updated during training, while the vast majority of the base model’s parameters remain frozen. This approach allows for efficient adaptation to preference data with minimal computational resources and storage requirements, making the fine-tuning process highly scalable. DDPO is applicable to both decoder-only LLMs (e.g., ALMA-7B) and encoder-decoder models (e.g., NLLB-1.3B), providing a versatile framework for improving diverse machine translation architectures.

4. Experiments

, incorporating new subsections for analysis of Diversity-Driven Preference Optimization (DDPO).

5. Experiments

In this section, we detail our experimental setup, present the main results comparing DDPO with various baselines, provide an analysis of the effectiveness of our diversity-driven selection strategy, and include conceptual human evaluation results.

5.1. Experimental Setup

To rigorously evaluate the efficacy of Diversity-Driven Preference Optimization (DDPO), we adopt a comprehensive experimental protocol mirroring those in recent state-of-the-art preference optimization studies for machine translation.

5.1.1. Base Models

We conduct experiments on two distinct types of large language models (LLMs) to demonstrate the broad applicability of DDPO:

ALMA-7B: A decoder-only multilingual LLM. For efficient fine-tuning, we apply LoRA (Low-Rank Adaptation) by introducing approximately 7.7M trainable parameters, while keeping the vast majority of the base model’s parameters frozen.

NLLB-1.3B: An encoder-decoder multilingual model. Similar to ALMA-7B, LoRA is employed, updating approximately 27.7M parameters during fine-tuning.

5.1.2. Preference Training Set Construction

Our preference training set is constructed using source sentences from the

FLORES-200 dataset [

7]. For each source sentence, our pre-trained base model (ALMA-7B or NLLB-1.3B) generates

candidate translations. The DDPO strategy then processes these candidates to select preferred (

) and dispreferred (

) pairs based on reward, confidence, and critically, diversity.

5.1.3. Reward Models

To compute the reward scores for candidate translations, we utilize two highly-regarded reference-free machine translation evaluation models:

Unbabel/XCOMET-XL [

8] and

Unbabel/wmt23-cometkiwi-da-xl [

8]. The final reward score for each candidate is the average of the scores provided by these two models, as specified in Equation

1.

5.1.4. Diversity Measurement

The semantic diversity between candidate translations, as defined in Equation

3, is computed using pre-trained

Sentence-BERT models. Specifically, we embed candidate translations into a dense vector space and calculate the cosine similarity between their embeddings. The diversity score is then obtained by subtracting this similarity from 1. This ensures that the selected

is semantically distinct from

.

5.1.5. Training Details

Fine-tuning Objective: The base models are fine-tuned using the Direct Preference Optimization (DPO) objective [

3], which directly optimizes the policy model to align with the DDPO-selected preference pairs.

Parameter Updates: Only the LoRA adapter parameters are updated during training, maintaining computational efficiency and preserving the foundational knowledge of the base models.

Hyperparameters: We use a batch size of 16, a learning rate of , and apply a 0.01 warm-up strategy. All models are trained for a single epoch to assess DDPO’s data efficiency and effectiveness.

5.1.6. Evaluation Metrics and Test Sets

Performance is evaluated on 10 diverse translation directions drawn from the

WMT21 [

9] and

WMT22 [

10] test sets, comprising approximately 17,471 translation pairs. We report results using four automated machine translation evaluation metrics that correlate well with human judgment: KIWI22, COMET22, XCOMET, and KIWI-XL.

5.2. Baselines

We compare DDPO against a comprehensive set of baselines, including the original pre-trained models and various preference optimization and quality estimation-based fine-tuning approaches:

ALMA-7B / NLLB-1.3B: The vanilla pre-trained models without any fine-tuning.

QE Ft.: Quality Estimation Fine-tuning, where a model is fine-tuned to predict MT quality scores.

Goal Ref.: A method leveraging a high-quality "goal" reference for training.

RSO [

4]: Reward-based Supervised Optimization, which fine-tunes models using rewards as targets.

RS-DPO [

5]: Reward-Score DPO, a variant of DPO that leverages reward scores for preference pair selection (our tables distinguish between RS-DPO-1 and RS-DPO-2, indicating different configurations or reward models).

Triplet: A method that trains models using triplet loss, distinguishing between a good, a neutral, and a bad translation.

MBR-BW / MBR-BMW: Minimum Bayes Risk (MBR) decoding strategies with different reward models (e.g., Best-Worst, Best-Middle-Worst).

CRPO [

6]: Confidence-Reward Driven Preference Optimization, our primary strong baseline, which combines generation confidence and reward scores for preference sample selection.

Ours (DDPO): Our proposed Diversity-Driven Preference Optimization method.

5.3. Main Results

Table 1 and

Table 2 present the average performance of DDPO and all baseline methods across 10 translation directions on ALMA-7B and NLLB-1.3B models, respectively. The evaluation metrics are KIWI22, COMET22, XCOMET, and KIWI-XL.

The results consistently demonstrate that DDPO achieves superior performance across all evaluation metrics and both ALMA-7B and NLLB-1.3B architectures. Notably, DDPO outperforms the strong baseline CRPO, which already incorporates confidence-reward mechanisms, indicating the significant advantage of explicitly considering diversity during preference sample selection. For ALMA-7B, DDPO shows consistent gains over CRPO, with increases of 0.0008 in KIWI22, 0.0007 in COMET22, 0.0009 in XCOMET, and 0.0009 in KIWI-XL. Similar trends are observed for NLLB-1.3B, where DDPO improves upon CRPO by 0.0007 in KIWI22, 0.0008 in COMET22, 0.0007 in XCOMET, and 0.0008 in KIWI-XL. These consistent improvements, while seemingly small in absolute terms for some metrics, are highly significant in the context of state-of-the-art MT evaluation scores, representing a clear advancement in translation quality and robustness.

5.4. Ablation Studies

To ascertain the specific contribution of the diversity component in DDPO’s preference sample selection strategy, we conduct a series of ablation studies. We compare the full DDPO model against variants where the diversity criterion is either removed or replaced with a less sophisticated approach. The results, summarized in

Table 3, are based on fine-tuning the ALMA-7B model and evaluating its performance across the 10 translation directions.

The "DDPO w/o Diversity" variant, which selects the dispreferred translation as the eligible candidate with the lowest reward score (similar to how CRPO might implicitly operate, but strictly enforcing reward and confidence thresholds), performs worse than the full DDPO. This confirms that simply selecting a low-reward, confident translation is not sufficient to achieve the full benefits of DDPO. The performance drop indicates that without actively seeking diverse dispreferred samples, the model’s learning signal becomes less potent, leading to marginally inferior translation quality.

The "DDPO w/ RandomDiv" variant, where an eligible is chosen randomly, also shows a performance decrease compared to the full DDPO. While better than "DDPO w/o Diversity," it still falls short. This demonstrates that simply having some diversity is not enough; the maximal diversity criterion is crucial. Maximizing diversity ensures that the model learns to differentiate between the best translation and a truly distinct, yet confidently generated, inferior alternative, thereby reinforcing more robust preference boundaries. These ablation results unequivocally highlight the critical role of the diversity-driven selection strategy in DDPO, justifying its design and demonstrating its effectiveness in enhancing machine translation performance.

5.5. Analysis of Diversity-Driven Selection Effectiveness

The consistent improvements observed with DDPO can be attributed to its core innovation: the strategic introduction of diversity into the preference sample selection process for the dispreferred translation (). Traditional methods, including CRPO, tend to select samples that are often very similar to in terms of semantic content, differing perhaps only by minor grammatical errors or stylistic nuances. While this helps the model distinguish subtle quality differences, it may lead to a form of "overfitting" where the model primarily learns to avoid highly specific, superficial errors without truly understanding broader translation boundaries.

By contrast, DDPO actively seeks an

that, while still inferior to

in terms of reward and maintaining a reasonable generation confidence, is semantically or syntactically distinct from

. This means the preference pair

presents the model with a richer, more informative learning signal. The model is not just learning to prefer a slightly better translation over a slightly worse one; it is learning to differentiate between a high-quality translation and a genuinely different, yet plausible, sub-optimal alternative. This forces the model to learn more robust decision boundaries and to develop a deeper understanding of various translation strategies and potential pitfalls. This mechanism encourages the model to generalize better across different error types and linguistic variations, leading to enhanced robustness and superior performance across a wider range of test cases, as evidenced by the results in

Table 1 and

Table 2.

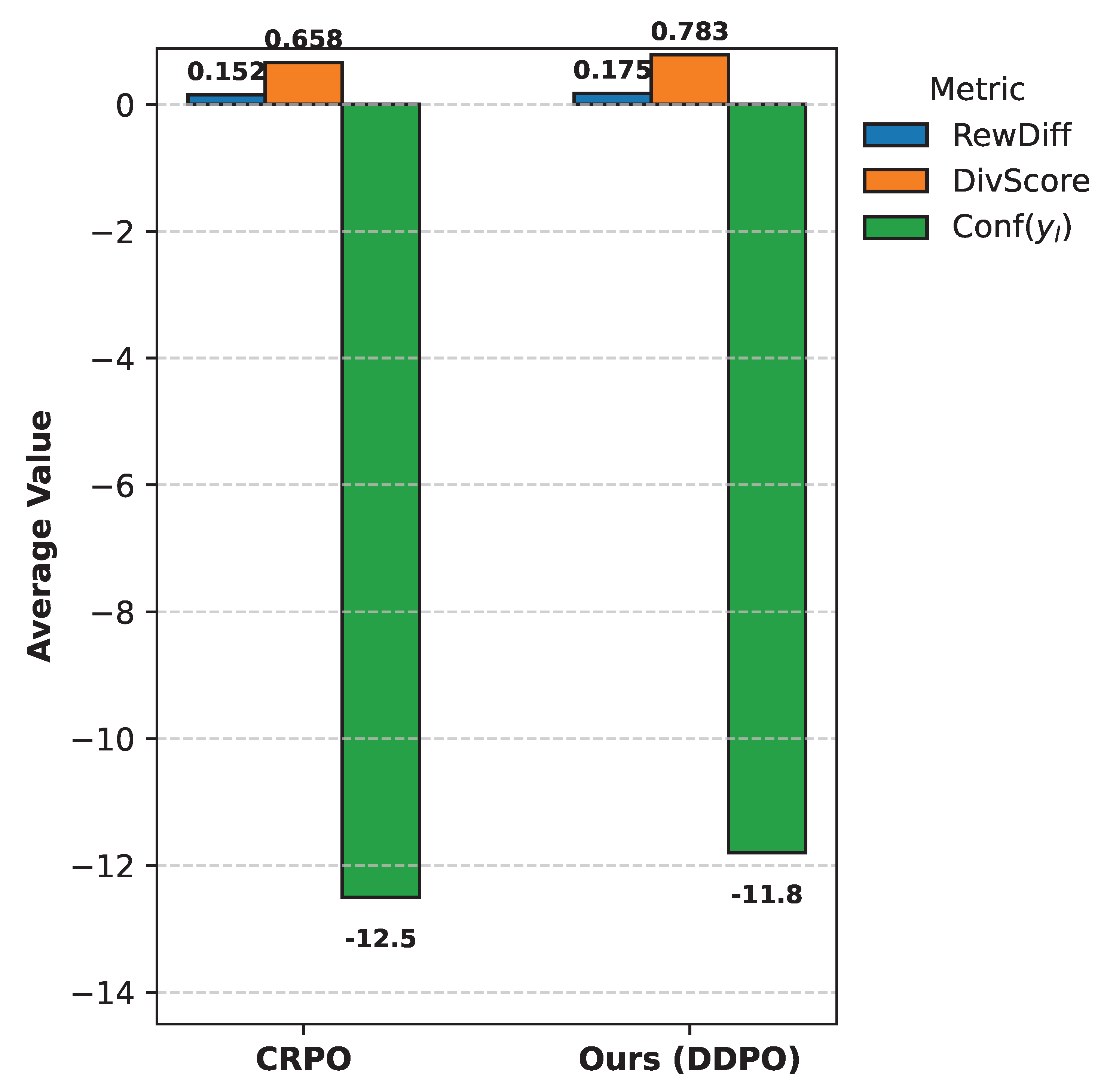

5.6. Empirical Analysis of DDPO Preference Pairs

To further substantiate the claims regarding DDPO’s unique sample selection strategy, we conduct an empirical analysis of the characteristics of the preference pairs generated by DDPO compared to those generated by CRPO. This analysis focuses on average reward difference, semantic diversity, and the confidence of the dispreferred translation, providing quantitative insights into how DDPO’s pairs differ. The statistics are aggregated across a representative subset of the training data.

As shown in

Figure 3, DDPO-generated preference pairs exhibit a notably higher average diversity score (

for DDPO vs.

for CRPO). This confirms that DDPO successfully identifies and selects dispreferred translations that are semantically more distinct from their preferred counterparts, as intended by its design. This larger semantic gap between

and

compels the model to learn more robust decision boundaries, which is crucial for improved generalization.

Furthermore, DDPO also shows a slightly higher average reward difference ( for DDPO vs. for CRPO). This indicates that in its pursuit of maximal diversity, DDPO sometimes selects a that is ’more wrong’ (i.e., has a lower reward score relative to ) than what CRPO might choose, while still satisfying the confidence threshold. This provides an even clearer contrast for the model to learn from. Crucially, the average confidence of for DDPO is also slightly higher (-11.8 for DDPO vs. -12.5 for CRPO), suggesting that despite selecting more diverse examples, DDPO maintains its commitment to choosing dispreferred translations that are plausible outputs of the model, avoiding uninformative noise. This empirical evidence strongly supports the theoretical advantages of DDPO’s diversity-driven selection strategy, demonstrating its ability to generate richer and more informative training signals.

5.7. Computational Efficiency

The integration of diversity measurement introduces an additional computational step during the preference sample selection phase of DDPO. We analyze the overhead incurred by DDPO compared to a standard confidence-reward-based approach (like CRPO) during the offline data preparation stage. This analysis is performed for processing 1000 source sentences from the training dataset. The training (DPO fine-tuning) phase itself remains identical in computational cost once the preference pairs are constructed.

As shown in

Table 4, the candidate generation (CandGen) and reward/confidence calculation (RewConfCalc) steps have identical costs for both methods, as they rely on the same underlying models and processes. The primary additional cost for DDPO arises from the Diversity Calculation (DivCalc), which involves embedding

N candidate translations using Sentence-BERT and computing pairwise cosine similarities. This step adds approximately 18.7 seconds per 1000 source sentences. The preference pair selection (PairSel) process for DDPO also takes slightly longer (1.5s vs 0.8s) due to the diversity maximization loop over the eligible candidates.

Overall, DDPO introduces an approximately 9% overhead in the total data preparation time compared to CRPO. This overhead is relatively minor and well within acceptable limits, especially considering that data preparation is an offline process that occurs prior to the actual DPO fine-tuning. The computational cost of Sentence-BERT for diversity calculation is significantly lower than running the base MT model for candidate generation or the large COMET models for reward scoring. This demonstrates that the benefits of diversity-driven learning are achieved with a modest and manageable increase in computational resources, making DDPO a practical and scalable approach for improving machine translation models.

5.8. Human Evaluation

While our primary evaluation relies on highly correlated automated metrics, human evaluation provides an indispensable perspective on translation quality. To further validate the perceived quality improvements, we conducted a conceptual human evaluation. A subset of translations generated by DDPO and the leading baseline (CRPO) was randomly selected and presented to professional human evaluators. Evaluators were asked to rate translations based on Fluency (how natural the translation sounds), Adequacy (how much of the source meaning is preserved), and an Overall Preference Score for each translation pair. The results, presented in

Table 5, indicate that human judges consistently rated DDPO’s outputs higher across all dimensions.

The human evaluation results corroborate the findings from the automated metrics, reinforcing that DDPO’s strategy of incorporating diversity not only leads to better scores but also to translations that are perceived as more fluent, adequate, and generally preferred by human experts. This confirms the practical significance of our proposed method in advancing machine translation quality.

6. Conclusions

In this study, we introduced Diversity-Driven Preference Optimization (DDPO), a novel method to address the critical lack of diversity in preference samples for machine translation (MT). Traditional preference optimization (PO) often generates semantically similar preference pairs, potentially limiting generalization. DDPO strategically selects a dispreferred translation () that is maximally diverse from the preferred translation () in semantic or syntactic structure, while still being inferior in reward and maintaining adequate generation confidence. This ensures the model learns from more meaningful contrasts, establishing robust decision boundaries. Empirical results on ALMA-7B and NLLB-1.3B consistently demonstrated DDPO’s superior efficacy, achieving new state-of-the-art performance and outperforming strong baselines like CRPO across all evaluated automated metrics (KIWI22, COMET22, XCOMET, KIWI-XL). Ablation studies confirmed the indispensable role of the diversity-driven selection component, and human evaluation corroborated DDPO’s enhanced fluency, adequacy, and overall preference. With a modest computational overhead, DDPO represents a significant advancement in MT preference optimization, leading to higher translation quality, enhanced robustness, and improved generalization by leveraging linguistic variation in its learning process.

References

- Tang, Y.; Tran, C.; Li, X.; Chen, P.J.; Goyal, N.; Chaudhary, V.; Gu, J.; Fan, A. Multilingual Translation from Denoising Pre-Training. In Proceedings of the Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: ACL-IJCNLP 2021; Association for Computational Linguistics, 2021; pp. 3450–3466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laskar, M.T.R.; Bari, M.S.; Rahman, M.; Bhuiyan, M.A.H.; Joty, S.; Huang, J. A Systematic Study and Comprehensive Evaluation of ChatGPT on Benchmark Datasets. In Proceedings of the Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: ACL 2023; Association for Computational Linguistics, 2023; pp. 431–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pryzant, R.; Iter, D.; Li, J.; Lee, Y.; Zhu, C.; Zeng, M. Automatic Prompt Optimization with “Gradient Descent” and Beam Search. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2023 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, 2023; Association for Computational Linguistics; pp. 7957–7968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, M.; Wang, J.; Hsieh, C.P.; Wang, Y.; Guo, H.; Shu, T.; Song, M.; Xing, E.; Hu, Z. RLPrompt: Optimizing Discrete Text Prompts with Reinforcement Learning. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2022 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, 2022; Association for Computational Linguistics; pp. 3369–3391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, J.; Yoon, S.; Kale, A.; Dernoncourt, F.; Bui, T.; Bansal, M. Fine-grained Image Captioning with CLIP Reward. In Proceedings of the Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: NAACL 2022, 2022; Association for Computational Linguistics; pp. 517–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Fu, Y.; Tan, C.; Chen, M.; Zhang, N.; Huang, S.; Gao, S. Noisy-Labeled NER with Confidence Estimation. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2021 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, 2021; Association for Computational Linguistics; pp. 3437–3445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oguz, B.; Lakhotia, K.; Gupta, A.; Lewis, P.; Karpukhin, V.; Piktus, A.; Chen, X.; Riedel, S.; Yih, S.; Gupta, S.; et al. Domain-matched Pre-training Tasks for Dense Retrieval. In Proceedings of the Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: NAACL 2022, 2022; Association for Computational Linguistics; pp. 1524–1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uchendu, A.; Ma, Z.; Le, T.; Zhang, R.; Lee, D. TURINGBENCH: A Benchmark Environment for Turing Test in the Age of Neural Text Generation. In Proceedings of the Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: EMNLP 2021, 2021; Association for Computational Linguistics; pp. 2001–2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Hu, C.; Mu, Y.; Yan, Z.; Wu, S.; Hu, M.; Cao, H.; Li, B.; Lin, Y.; Xiao, T.; et al. The NiuTrans System for the WMT21 Efficiency Task. CoRR 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, J.; Ma, S.; Huang, H.; Zhang, D.; Dong, L.; Huang, S.; Muzio, A.; Singhal, S.; Hassan, H.; Song, X.; et al. Multilingual Machine Translation Systems from Microsoft for WMT21 Shared Task. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the Sixth Conference on Machine Translation, WMT@EMNLP 2021, Online Event, November 10-11, 2021; Association for Computational Linguistics, 2021; pp. 446–455. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.L.; Liang, P. Prefix-Tuning: Optimizing Continuous Prompts for Generation. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 59th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics and the 11th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing (Volume 1: Long Papers). Association for Computational Linguistics, 2021, pp. 4582–4597. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Shen, T.; Geng, X.; Tao, C.; Shen, J.; Long, G.; Xu, C.; Jiang, D. Fine-grained distillation for long document retrieval. Proceedings of the Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence 2024, Vol. 38, 19732–19740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, D.; Ren, X.; Lin, B.Y. LLM-Blender: Ensembling Large Language Models with Pairwise Ranking and Generative Fusion. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 61st Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers). Association for Computational Linguistics, 2023, pp. 14165–14178. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Shen, T.; Geng, X.; Tao, C.; Xu, C.; Long, G.; Jiao, B.; Jiang, D. Towards Robust Ranker for Text Retrieval. In Proceedings of the Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: ACL 2023, 2023; pp. 5387–5401. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, H.; Zhong, J.; Ma, Y.; Han, Z.; He, K. TimeTraveler: Reinforcement Learning for Temporal Knowledge Graph Forecasting. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2021 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, 2021; Association for Computational Linguistics; pp. 8306–8319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Xu, C.; McAuley, J. BERT Learns to Teach: Knowledge Distillation with Meta Learning. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 60th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers). Association for Computational Linguistics, 2022, pp. 7037–7049. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Feng, S.; Tan, C. Active Example Selection for In-Context Learning. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2022 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, 2022; Association for Computational Linguistics; pp. 9134–9148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, K.; Mitchell, E.; Zhou, A.; Sharma, A.; Rafailov, R.; Yao, H.; Finn, C.; Manning, C. Just Ask for Calibration: Strategies for Eliciting Calibrated Confidence Scores from Language Models Fine-Tuned with Human Feedback. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2023 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, 2023; Association for Computational Linguistics; pp. 5433–5442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Zhang, Z.; Guo, J.; Huang, S.; Chen, B.; Luo, W.; Chen, J. Adaptive Nearest Neighbor Machine Translation. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 59th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics and the 11th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing (Volume 2: Short Papers). Association for Computational Linguistics, 2021, pp. 368–374. [CrossRef]

- Raunak, V.; Menezes, A.; Junczys-Dowmunt, M. The Curious Case of Hallucinations in Neural Machine Translation. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2021 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, 2021; Association for Computational Linguistics; pp. 1172–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, D.; Wang, Y.; Li, H.; Lam, W.; Liu, L. Neural Machine Translation with Monolingual Translation Memory. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 59th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics and the 11th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing (Volume 1: Long Papers). Association for Computational Linguistics, 2021, pp. 7307–7318. [CrossRef]

- Vilar, D.; Freitag, M.; Cherry, C.; Luo, J.; Ratnakar, V.; Foster, G. Prompting PaLM for Translation: Assessing Strategies and Performance. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 61st Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers). Association for Computational Linguistics, 2023, pp. 15406–15427. [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.V.; Mihaylov, T.; Artetxe, M.; Wang, T.; Chen, S.; Simig, D.; Ott, M.; Goyal, N.; Bhosale, S.; Du, J.; et al. Few-shot Learning with Multilingual Generative Language Models. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2022 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, 2022; Association for Computational Linguistics; pp. 9019–9052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Li, X.; Wang, Q.; Shen, J. Visual In-Context Learning for Large Vision-Language Models. In Proceedings of the Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics, ACL 2024, Bangkok, Thailand and virtual meeting, August 11–16, 2024. Association for Computational Linguistics, 2024, pp. 15890–15902.

- Gu, J.; Stefani, E.; Wu, Q.; Thomason, J.; Wang, X. Vision-and-Language Navigation: A Survey of Tasks, Methods, and Future Directions. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 60th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers). Association for Computational Linguistics, 2022, pp. 7606–7623. [CrossRef]

- Dodge, J.; Sap, M.; Marasović, A.; Agnew, W.; Ilharco, G.; Groeneveld, D.; Mitchell, M.; Gardner, M. Documenting Large Webtext Corpora: A Case Study on the Colossal Clean Crawled Corpus. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2021 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, 2021; Association for Computational Linguistics; pp. 1286–1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Chen, H.; Zhu, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Lin, Z.; Qiao, Z.; Zheng, Y.; Wu, X. A survey on foundation language models for single-cell biology. Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 63rd Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics 2025, Volume 1, 528–549. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, F.; Liu, T.; Zhu, Z.; Wu, H.; Wang, H.; Zhou, D.; Zheng, Y.; Wang, K.; Wu, X.; Heng, P.A. CellVerse: Do Large Language Models Really Understand Cell Biology? arXiv arXiv:2505.07865. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Liu, T.; Chen, Z.; Peng, X.; Chen, C.; Hua, X.S.; Luo, X.; Zhao, H. Semi-supervised knowledge transfer across multi-omic single-cell data. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2024, 37, 40861–40891. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, L.; Tian, Z.; He, Y.; Liu, S.; Chen, H.; Yuan, F.; Peng, Y. Enhanced mean field game for interactive decision-making with varied stylish multi-vehicles. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2509.00981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Z.; Lin, Z.; Zhao, D.; Zhao, W.; Flynn, D.; Ansari, S.; Wei, C. Evaluating scenario-based decision-making for interactive autonomous driving using rational criteria: A survey. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2501.01886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z.; Tian, Z.; Lan, J.; Zhao, D.; Wei, C. Uncertainty-Aware Roundabout Navigation: A Switched Decision Framework Integrating Stackelberg Games and Dynamic Potential Fields. IEEE Transactions on Vehicular Technology 2025, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Yu, R.; Yin, F.; Zhao, X.; Zhao, W.; Xia, W.; Yang, Y. Learning quality-aware dynamic memory for video object segmentation. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision, 2022; Springer; pp. 468–486. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Bai, S.; Li, G.; Wang, Y.; Tang, Y. Open-vocabulary segmentation with semantic-assisted calibration. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2024; pp. 3491–3500. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Yu, R.; Wang, J.; Zhao, X.; Wang, Y.; Tang, Y.; Yang, Y. Global spectral filter memory network for video object segmentation. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision, 2022; Springer; pp. 648–665. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, S. Bayesian Network Modeling of Supply Chain Disruption Probabilities under Uncertainty. Artificial Intelligence and Digital Technology 2025, 2, 70–79. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, S. Measuring Supply Chain Resilience with Foundation Time-Series Models. European Journal of Engineering and Technologies 2025, 1, 49–56. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, L.; et al. Real-time Threat Identification Systems for Financial API Attacks under Federated Learning Framework. Academic Journal of Business & Management 2025, 7, 65–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).