1. Introduction

Stress affects millions of people worldwide. The prevalence of the increasing rise in stress may be attributed to many factors, such as environmental stress, socioeconomic pressures, and/or unhealthy lifestyle changes (Kivimäki et al., 2023; Kumar et al., 2022). Acute stress triggers the release of epinephrine and norepinephrine from the sympathetic nervous system (SNS). This leads to the fight-or-flight response (Won and Kim, 2016; Ebert et al., 2004). However, chronic or ongoing stress activates the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis (Byrne et al., 2018; Sharma, 2018; Giles et al., 2014). This activation stimulates the hypothalamus to release corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) (James et al., 2023; Molina-Hidalgo et al., 2023). Additionally, CRH prompts the adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) released by the pituitary to stimulates cortisol release from the adrenal glands (Molina-Hidalgo et al., 2023; Kageyama et al., 2021).

While acute stress is essential for physiological functioning and maintenance, chronic stress disrupts the physiological responses of the body’s allostatic systems (Malhotra et al., 2024). Allostasis refers to the process by which stability or homeostasis is achieved through adaptation (Sterling and Eyer, 1998). However, the cumulative “wear and tear” on the body (Juster et al., 2010) due to prolonged adaption to chronic adverse physical or psychosocial situations is termed allostatic load (AL) (Osei et al., 2024; McEwen and Stellar, 1993). AL can be assessed through various biomarkers across physiological systems. Researchers have identified key mediators of AL (Beckie, 2012; Sun et al., 2007; Goldman et al., 2006; Seplaki et al., 2005; Seeman et al., 2001) which are classified into primary and secondary mediators based on their immediate impact on the body’s physiological systems. For instance, cortisol, epinephrine, norepinephrine and dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate (DHEA-S) are considered to be the primary mediators of AL (Seeman et al., 2001).

Chronic stress has been associated with the development of various stress-related disorders, metabolic risk factors, and metabolic diseases including metabolic syndrome (MetS) (Osei et al., 2022; Park et al., 2011; Phillips et al., 2010; Torpy et al., 2007; Ebert et al., 2004). MetS is described as the presence of high blood pressure, abdominal obesity, low high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol, increased triglycerides, and hyperglycemia (Osei et al., 2022; Alberti et al., 2009). Cortisol, for example, plays a crucial role in regulating glucose metabolism, immune response, and blood pressure. However, chronic elevations in cortisol levels are linked to the development of visceral obesity, insulin resistance, and hypertension, all of which are associated with MetS (Athanasiou et al., 2023; Zhao et al., 2023). Similarly, prolonged activation of the SNS, as evidenced by higher epinephrine and norepinephrine, raises cardiometabolic risk by increasing heart rate, blood pressure, and vascular resistance (Torpy et al., 2007; Ebert et al., 2004). DHEA-S, a counter-regulatory hormone, helps mitigate the negative effects of cortisol. However, its levels often decline in response to chronic stress, thereby contributing to the development of MetS (Heaney et al., 2012). Therefore, preventive lifestyle modifications, such as exercise training, is essential to counteracting the harmful effects of chronic stress.

Exercise refers to the subset of planned and repetitive physical activity (PA) aimed at promoting physical fitness and, thus, maintaining a good health status (Martínez-Vizcaíno et al., 2023). PA can be categorized into two types: exercise, which refers to engaging in high-intensity PA akin to that of an athlete (e.g., a minimum of 10 hours per week of training), and leisure sports, which involves moderate PA during recreational or leisure time (Bull et al., 2020). Acute exercise, such as endurance exercise and high-intensity interval training (HIIT) (Çınar et al., 2025), leads to stimulation of the HPA axis and locus coeruleus/norepinephrine (LC/NE) system, leading to secretion of cortisol, epinephrine, and norepinephrine (Çınar, et al., 2025; Athanasiou et al., 2023; Bogdanis et al., 2022; Bracken and Brooks, 2010). However, regular endurance exercise and HIIT training leads to lower secretion of cortisol, epinephrine, and norepinephrine. This implicates the adaptive response of the HPA axis and catecholamine responses due to the activity of catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT) to both regular endurance exercise and HIIT exercise (Athanasiou et al., 2023; Bogdanis et al., 2022; Bracken and Brooks, 2010). Regarding the influence of exercise on buffering stress load related to the impairment of metabolic risk markers and the development of MetS, it is important to consider the different types of exercise and the various influencing factors. It has been shown that moderate PA reduce hyperactivity of the HPA axis, lower cortisol levels, and inhibit overactivation of the SNS (Daniela et al., 2022). Exercise also boosts DHEA-S synthesis, which acts as a cortisol counterweight and promotes stress recovery (Heaney et al., 2013). These effects are mediated by several pathways, including endorphin release, improved autonomic balance, and increased neuroplasticity (Ribeiro et al., 2021; Liu and Nusslock, 2018; Heaney et al., 2012). In summary, regular PA or exercise training helps mitigate the accumulation of AL by enhancing adaptive stress responses and improving metabolic health (D'Alessio et al., 2020; McEwen, 2007).

To better understand the underlying pathophysiological mechanisms, it would be valuable to conduct research in a healthy population. This is because most research has been conducted in diseased populations (Osei et al., 2024; Osei et al., 2022; Wiltink et al., 2018; Block et al., 2016). Individuals especially with high AL may exhibit subclinical metabolic markers abnormalities such as impaired glucose tolerance or borderline hypertension, which over time, can progress to MetS (Gruenewald et al., 2012). The absence of overt MetS in these healthy people complicates early detection and intervention. In Germany, earlier research has highlighted the association between MetS and stress-related conditions such as depression in both young and older adults (Wiltink et al., 2018; Block et al., 2016). Moreover, six months of telemonitoring-supported exercise training has been shown to reduce MetS severity, depression severity, and improve metabolic risk markers such as BMI, systolic blood pressure, and waist circumference in adults (Haufe et al., 2019). Although, the reported evidence links PA, metabolic risk markers and as well as MetS. Studies on PA, the primary mediators of AL and metabolic risk in healthy adults in Germany is scarce. The current study investigated different PA volumes on the primary mediators of AL and metabolic risk markers and the incidence of MetS in healthy adults in Germany. This method allows for sensitive analysis of metabolic dysregualtion in regards to stress physiology.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

The analysis is based on data from parallel study 3 (i.e., PSA3 study) within the National Research Network, “Medicine in Spine Exercise (MiSpEx) Network”. PSA-3 was a longitudinal observational study with measurement time points (M1–M4) taken every four months between August 2013 and June 2015 (see Wippert et al., 2022; Wippert et al., 2014). Data were collected using standardized questionnaires (M1–M4) and biomarkers from hair, blood, and urine (M1, M4), with laboratory assessments conducted by trained nurses. For the current study, only baseline data (M1) were used. For collection procedures for urine and blood samples (see Wippert et al., 2022; Wippert et al., 2014).

2.2. Study Population

Participants were recruited from the Ernst von Bergmann clinic and the University of Potsdam outpatient clinic, with a final sample of n = 140 individuals aged 18 to 45 years included in the study. As an incentive, participants received their exam results and a personalized stress profile upon study completion (Wippert et al., 2022). The inclusion criteria were as follows: the ability to understand the study's content and complete a German questionnaire; at least one episode of non-specific low back pain (LBP) lasting four or more days in the previous 12 months, in accordance with national treatment guidelines (Kanowski et al., 2017) defined by a minimum pain intensity score of 20 on a pain 100-point visual analog scale (VAS)]. Exclusion criteria were pregnancy, acute infections, hormone therapy, or the use of specific medications (such as glucocorticoids and antibiotics); certain diseases (such as cardiovascular, metabolic, thyroid, vascular, malign, lung, or autoimmune diseases); hemophilia; psychological disorders (such as those listed in ICD-10: F70–79); and hair shorter than 2 cm (see Wippert et al., 2022). n = 110 persons completed baseline (M1), n = 73 (M2), n = 72 (M3), and n = 63 (M4). For this current study, (n = 46) participants from the baseline sample took part in the AL laboratory testing (see Wippert et al., 2022). Also, the participants included in this current study did not have any cardiovascular or metabolic diseases and followed the same exclusion criteria as described by (Wippert et al., 2022).

2.3. Ethical Approval

The study was carried out in compliance with the values outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki of 1975, as revised in 2013. A study nurse provided written and spoken information about the study to each participant before they all signed the written informed consent form. The main institutional ethics review board of the University of Potsdam, Germany, granted the final ethical approval on May 6, 2013 (No. 44/2012).

2.4. Physical Activity Assessments

A self-structured PA questionnaire (i.e., frequency per week and duration of unit) by World health organization (WHO) guidelines (Bull et al., 2020) was used to assess PA participation; High intensity PA (labelled as exercise) was defined as above 10 hours a week, leisure sport was defined as below 10 hours a week. Leisure sports was calculated as the product of time (min) and days spent performing activities such as walking, stair climbing, and cycling. Similar, exercise was calculated as the product of time (min) and days spent performing exercise training (e.g., football, judo, swimming, basketball, etc.). Furthermore, an additional scale was calculated for the total PA (PA, min/wk) which was the product of days and time (min) spent performing both exercise and leisure sports. On this base study participants were categorized into two groups: regular PA (n = 37 , ≥ 150 minutes/week) and non-regular PA (n = 8 , <150 minutes/week) related to the minimum threshold of the WHO guidelines for health-promotion.

2.5. Metabolic Risk Markers and Metabolic Syndrome Diagnosis

MetS was diagnosed and measured based on the established metabolic risk markers from Alberti et al. (2009). This include elevated waist circumference (≥ 80 cm for women, ≥ 94 cm for men, European threshold cut-off recommendation); elevated blood pressure (systolic ≥ 130 mmHg and/or diastolic ≥ 85 mmHg, or antihypertensive drug treatment with a clinical diagnosis of hypertension); elevated fasting blood glucose (≥ 100 mg/dl or drug treatment of elevated glucose with clinical diagnosis of diabetes mellitus) (Wiltink et al., 2018; Alberti et al., 2009); elevated triglycerides (≥ 150 mg/dl); reduced HDL-C (< 50 mg/dl); or elevated fasting blood glucose (≥ 100 mg/dl or medication treatment of elevated glucose with a clinical diagnosis of diabetes mellitus). MetS is diagnosed by the presence of three or more of all the criteria above (Wiltink et al., 2018; Alberti et al., 2009).

2.6. Primary Mediators of Allostatic Load

12-h urinary cortisol (μg/12h) was assessed via enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA, RE52241, ILB International GmbH, Germany). Serum DHEAS (μg/ml) was assessed via ELISA (RE52181, TECAN Hydro Flex, ILB International GmbH Germany) (Wippert et al., 2022). 12-h overnight urinary epinephrine (μg/12h) and norepinephrine (μg/12h) levels were assessed via ELISA (epinephrine RE59251, norepinephrine RE5926, both by ILB International GmbH Germany) (Wippert et al., 2022). Cortisol, epinephrine, norepinephrine, and DHEA-S were computed to calculate primary allostatic load index (ALI). Primary (ALI) scores were calculated as the sum of single biomarkers falling within the high-risk quartile of the sample (Wippert et al., 2022; Wippert et al., 2014). Participants with results in the fourth quartile (> 75%) were given the value 1 (burdened), while the remaining participants received the value 0 (unburdened) (Wippert et al., 2022; Wippert et al., 2014).

2.7. Blood Pressure Measurement

Outpatient nurses measured systolic and diastolic blood pressure at three different times, with a 30-second rest interval in between each measurement. The readings of the second and third were averaged to provide the final blood pressure readings. The measurement was taken with (BOSO BS 90 Blood pressure device, BOSCH + SOHN GmbH u. Co., KG, Jungingen, Germany) (see Wippert et al., 2022; Wippert et al., 2014).

2.8. Lipid and Glucose Metabolic Biomarkers

Using enzymatic colorimetric assays (ABBOTT Architect ci8200; Abbott Laboratories, IL, USA), triglycerides, HDL-C, and LDL-C were measured. In addition, measurements of height (Seca 222 telescopic measuring rod; Seca AG, Switzerland), weight (Kern MPS scale; Kern & Sohn GmbH, Balingen, Germany), and waist/hip circumference (customary measuring tape) were taken (Wippert et al., 2022). The waist circumference was measured above the umbilicus at the narrowest point between the ribs and the iliac crest, and the hip circumference was measured at the widest point across the buttocks. The ratio of weight (kg) to height (m2) was calculated for body mass index (BMI) (Wippert et al., 2022; Wippert et al., 2014). Glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1c) was measured using high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) Bio-Rad Variant II (Bio-Rad Laboratories, CA, United States); fasting insulin was measured using an electrochemiluminescence enzyme immunoassay (ECLIA) using a Roche Cobas 8000 Modul E620 (Roche Diagnostics Ltd., Basel, Switzerland); and fasting glucose was measured by a hexokinase enzymatic reaction using a Roche Cobas 400 Plus (Roche Diagnostics Ltd., Basel, Switzerland) (Wippert et al., 2022). The following formula was used to compute insulin resistance [using the Homeostasis Model Assessment Index (HOMA)]: glucose [mg/dl] x insulin [mU/ml]/405 (see Wippert et al., 2022; Wippert et al., 2014).

2.9. Statistical Analysis

Data was analysed using the Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS 29.0, Chicago, IL, USA) computer software. The data was tested for normality using the Shapiro-Wilk test. The data was skewed; hence, non-parametric analysis was performed. Descriptive data are presented in

Table 1. Mann-Whitney U-test was used to find the differences between groups of different

PA concerning primary mediators of AL and MetS criteria. The significance level was set at

p < 0.05.

3. Results

Finally, a total of n = 46 participants were included in the study (65.2% female, 32.6% male; median age = 30 years). Among them, 37 participants (80.4%) engaged in regular exercise, and 97.4% additionally participated in leisure sports activities. One participant reported being physically active only through leisure sports. Regarding the biomarkers, all participants were within recommended normal or physiological ranges such as for cortisol (μg/12h), epinephrine (μg/12h), norepinephrine (μg/12h), DHEA-S (μg/ml). The MetS diagnosis criteria were met by only n = 2 participants (4.3%) – one from the regular and one from the non-regular PA group. Applying the diagnosis criteria of the MetS (Alberti et al. 2009), n = 9 (19.6 %) of the sample were identified with elevated waist circumferences, n = 4 (8.7 %) with elevated blood pressure, n = 2 (4.3 %) with elevated blood glucose, n = 2 (4.3 %) with elevated triglycerides and additional n = 2 (4.3 %) with reduced HDL-C.

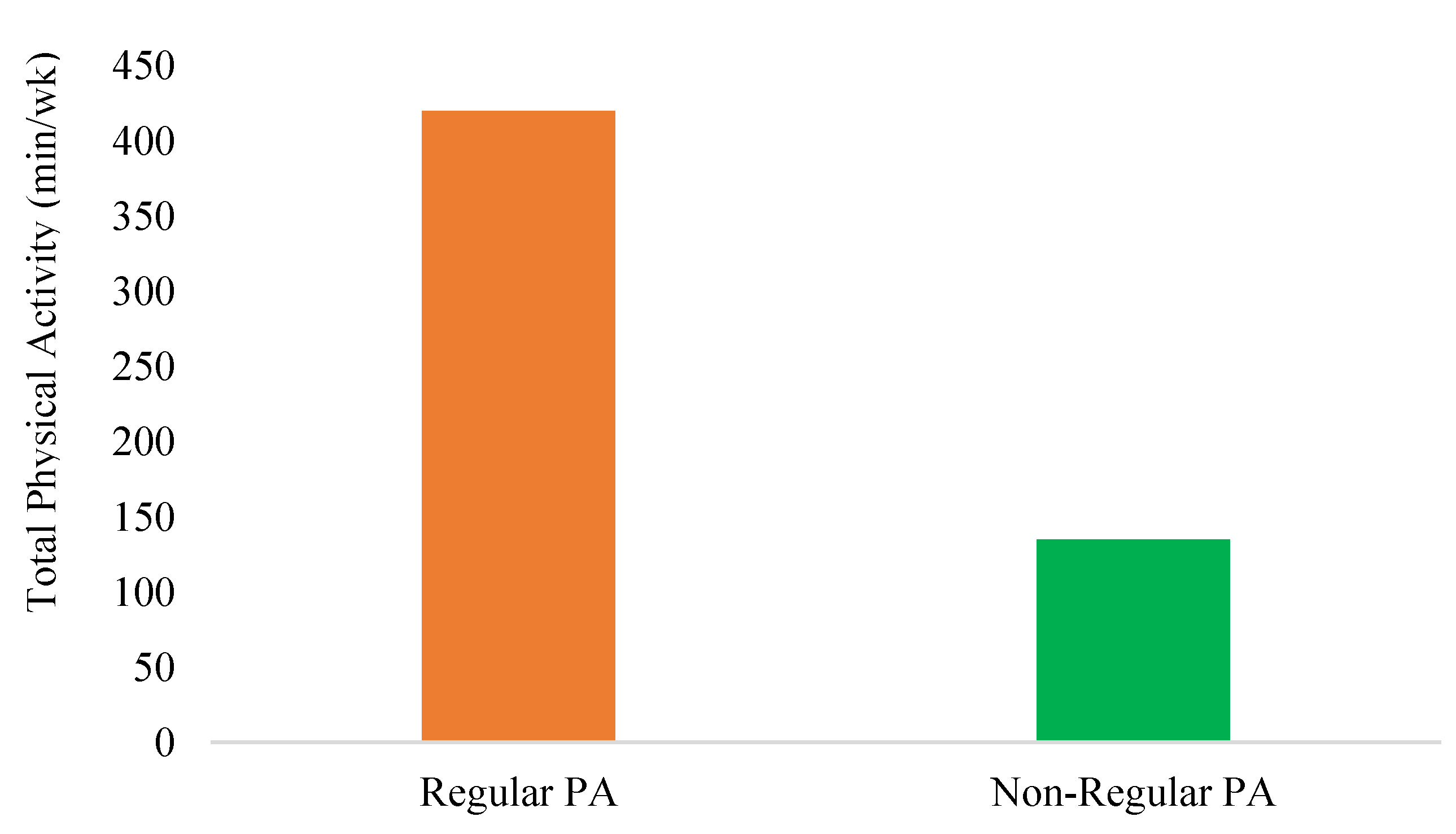

Descriptive analyses revealed differences between individuals who engage in regular PA and those who incorporate PA only occasionally into their daily routines (non-regular PA). Regularly active individuals exhibit approximately a fourfold higher level of activity (regular PA: Mdn = 420 min vs. non-regular PA: Mdn = 135 min; U = 35.500, Z = -2.648, p = 0.008). The higher physiological strain in this group is reflected in the primary AL mediators cortisol (regular PA: Mdn = 130.60 μg/12h vs. non-regular PA: Mdn = 71.50 μg/12h; U = 61.00, Z = -2.583, p = 0.01). No significant differences were observed between epinephrine, norepinephrine and DHEA-S. Additionally, no significant differences (p > 0.05) were found on metabolic risk markers such as triglycerides, blood pressure, waist circumference, fasting blood glucose, BMI, WC, and HDL-C among the two group (see

Table 2).

Figure 1.

Differences in Total physical activity (min/wk) between regular PA and non-regular PA participants.

Figure 1.

Differences in Total physical activity (min/wk) between regular PA and non-regular PA participants.

4. Discussion

The present study investigated different PA volumes on the primary mediators of AL, metabolic risk markers and the incidence of MetS in healthy adults. The population under investigation was therefore considered healthy based on subjective self-reports of illnesses and the biological markers measured. Only two participants met the clinical criteria for MetS. Individuals who engaged in regular PA demonstrated an approximately fourfold higher activity level compared to the non-regularly active group.

In the regular PA group, the total PA (min/week) was (mdn = 420 min/week). Previous studies have reported that 150 ≥ 300 minutes of moderate-to-vigorous PA per week reduces MetS incidence (Cleven et al., 2023; Seo et al., 2023). The current findings align with these data and underscore the preventive relevance of maintaining consistent PA across adulthood. However, in the non-regular PA group, the total PA (min/week) was (mdn = 135 min/week) with (n = 1, 2.17%) having MetS. This is in contrast with the findings from Rosenberger et al., (2013) who reported (n = 33, 18.3%) of their participants meeting at least 150 activity minutes had MetS. This differences may arise from the small sample size (n = 7) of our healthy non-regular PA participants as compared to the bigger sample size (n = 180) of already overweight/Obese prediabetic participants used in the study by (Rosenberger et al., (2013). Hence, caution should be taken when interpretating this current results.

Additionally, the higher physiological strain in the regularly PA group is reflected in significantly elevated cortisol levels, as well as slightly increased in epinephrine and norepinephrine levels. A more detailed analysis of the descriptive data reveals that presented cortisol levels are influenced by the volume and intensity of exercising. This finding aligns with other studies, which have reported higher cortisol levels in individuals who engage in exercise training compared to those who do not participate in exercise training (Athanasiou et al., 2023; Zouhal et al., 2008). This phenomenon can be attributed to the exercise-induced glucocorticoid paradox (Chen et al., 2017).

The repeated stress from exercise training frequently activates the HPA axis, leading to ACTH hypersecretion due to adrenal enlargement, which triggers cortisol release. On one hand, this can result in higher basal and exercise-induced cortisol levels as the body becomes more efficient in responding to stress (Athanasiou et al., 2023; Zouhal et al., 2008). On the other hand, excessive and high intense exercise training without adequate recovery may lead to overtraining syndrome, which results from prolonged HPA axis activation and disrupted circadian rhythms (Kreher and Schwartz, 2012). Nevertheless, cortisol levels in both study groups remained within the normal range.

Previous study by Park et al., (2011) with (n = 1881) participants, reported higher cortisol was significantly associated with MetS. This contradicts to this current study as only one participant from the regular PA had MetS. The plausible explanations could be due to the physically high intensely active of our sample, which could lead to a higher baseline of AL-primary mediator such as cortisol. It has been shown that regular exercise training promotes adaptive stress responses and improving metabolic health (D'Alessio et al., 2020; McEwen, 2007). Also, the age (Mdn = 30.0 years) of our participants was younger as compared to the participants (age = 58.7 ± 10.8 years) in the study by Park et al. (2011). Aging causes reduced sensitivity of the HPA axis to negative cortisol feedback control (Gaffey et al., 2016). Additionally, in sedentary individuals, persistent blunted cortisol responses show HPA hypoactivity. This can lead to fatigue, low-grade inflammation and metabolic dysregulation (Jones and Gwenin, 2021; Henson et al., 2015).

In comparing the two groups (i.e., regular PA vs non-regular PA), no significant group differences were observed for epinephrine, norepinephrine, primary ALI and DHEA-S. Interestingly, similar results have been found in other studies with healthy adults, showing variations in sympathetic activity is seen under chronic stress or obesity (Hamer and Steptoe, 2012; Davy and Orr, 2009). In the regular PA, the slightly increase in catecholamines and lower DHEA-S shows that regular exercise may promote optimal adrenal responsiveness and anabolic – catabolic homeostasis (Heaney et al., 2014). It should be noted that during both acute stress and exercise, epinephrine is released into the bloodstream from the adrenal medulla as a result of SNS activation (Çınar et al., 2025). This triggers the body for energy mobilization by stimulating lipolysis, hepatic glucose output, and suppression of insulin secretion through the β-adrenergic signaling pathways (Daniela et al., 2022; Torpy et al., 2007). Although, chronic stress may lead to adverse cardiometabolic outcomes due to SNS overactivity (Guzzoni et al., 2022; Torpy et al., 2007; Ebert et al., 2004). Also, chronic stress impairs norepinephrine function causing hepatic gluconeogenesis of β-adrenergic receptors activation in hepatocytes (Athanasiou et al., 2023), lipolysis, and visceral fat accumulation, fostering MetS development (Jin et al., 2023; Ross et al., 2021; Lee et al., 2001). However, in physically active individuals, acute or moderate increase in epinephrine have been shown to be associated with enhanced metabolic flexibility and reduced central adiposity (Lin et al., 2022; He et al., 2016). This could be the reason for the low MetS incidence in both groups in this current study. Additionally, regular PA improves norepinephrine activity and function resulting from an adaptive response to the HPA axis and catecholamines by the activity of COMT (Athanasiou et al., 2023; Bogdanis et al., 2022; Bracken and Brooks, 2010). Epinephrine enhances fat oxidation and thermogenesis, resulting in lower visceral fat accumulation, which is one of the key components of MetS (Ziegler et al., 2012). Long term PA participation does not only temporarily increase epinephrine levels during exercise but also improves β-adrenergic sensitivity and mitochondrial efficiency in skeletal muscle. This contributes to better glucose absorption and insulin sensitivity (Bird and Hawley, 2017). The findings of this research are consistent with previous research demonstrating that regular PA can reduce the insulin-antagonistic effects of catecholamines while increasing their lipolytic and anti-inflammatory capabilities, and thus reducing MetS risk (Lin et al., 2022; He et al., 2016). Additionally, it should be noted that the stress response to PA varies differently due to factors such as intensity, duration, and type of PA (Athanasiou et al., 2023; Bogdanis et al., 2022; Bracken and Brooks, 2010).

Furthermore, anthropometric measure such as BMI and waist circumference did not show any significant difference between the two groups. However, lower central adiposity was observed in the regular PA group. This finding aligns with previous data showing regular PA promotes metabolic health irrespective of body weight (Ross et al., 2019). Interestingly, the divergent between cortisol and triglycerides profiles amongst the two groups may show an early adaptation that may precede cumulative burden (Juster et al., 2010). Additionally, regular PA group showed a lower triglycerides and greater HDL-C levels as compared to the non-regular PA group. This is consistent with existing evidence associating PA to improved lipid metabolism, even if lipid and glycemic indicators did not differ significantly (Pedersen and Saltin, 2015). In line with research showing the vascular and autonomic benefits of regular exercise, both regular PA and non regular PA group tended to have similar lower systolic and diastolic blood pressures (Cornelissen and Smart, 2013). These results support the idea that regular PA, even at modest levels, helps to maintain metabolic homeostasis through neuroendocrine and cardiovascular pathways.

Theoretically, in the AL theory, long-term exposure to stress causes cumulative physiological dysregulation in the immunological, metabolic, and neuroendocrine systems (Juster et al., 2010; McEwen, 1998; McEwen and Stellar, 1993; Sterling and Eyer, 1998). However, one powerful behavioral regulator of these processes is PA. Exercise increases systemic flexibility and lowers basal AL by imposing acute, manageable stressors that recalibrate the SNS and HPA axis (D'Alessio et al., 2020; Gerber and Pühse, 2009; McEwen, 2007). These modifications reduce the development of MetS by enhancing insulin sensitivity, lipid turnover, and endothelial function (Ribeiro et al., 2021; Liu and Nusslock, 2018; Smith et al., 2018; Warburton and Bredin, 2017; Heaney et al., 2012; McEwen, 2007). The cortisol and lipid variations found in this study indicate that while insufficient exercise may lead to ineffective or muted stress physiology, regular PA may support-stress regulatory mechanisms and protection against early metabolic dysregulation. However, in the overall sample, higher blood glucose, waist circumferences, triglycerides, and lower HDL-C were observed in some participants. This shows that even in healthy individuals, subclinical cardiometabolic markers may be present which can later lead to MetS (Gruenewald et al., 2012). Hence, in healthy people, personalized preventive measures together with regular PA and routine medical checkup are recommended to foster early metabolic risk diagnosis and management.

The current study has limitations that should be considered by future researchers. This was a secondary data analysis. Thus, the reliance on self self-reported PA, the small sample size, gender imbalance favoring females, and cross-sectional sample limits causal inference and generalization. Also, information concerning the number of years the participants have been participating in PA was unknown; hence, care should be taken when interpretating the results. Future research should replicate these findings with larger, longitudinal cohorts and include objective PA measurements (e.g., accelerometry) to enhance validity. Incorporating more sensitive biomarkers such as inflammatory cytokines could also elucidate mechanistic pathways linking stress regulation and metabolic health. Additionally, there are different scoring procedures and biomarkers used in calculating primary ALI (Beckie, 2012; Goldman et al., 2006). This could lead to different outcomes. In the current study, ALI was calculated from Seeman et al. (1997). However, assessing AL across the various neuroendocrine systems is complex and warrants further research.

5. Conclusions

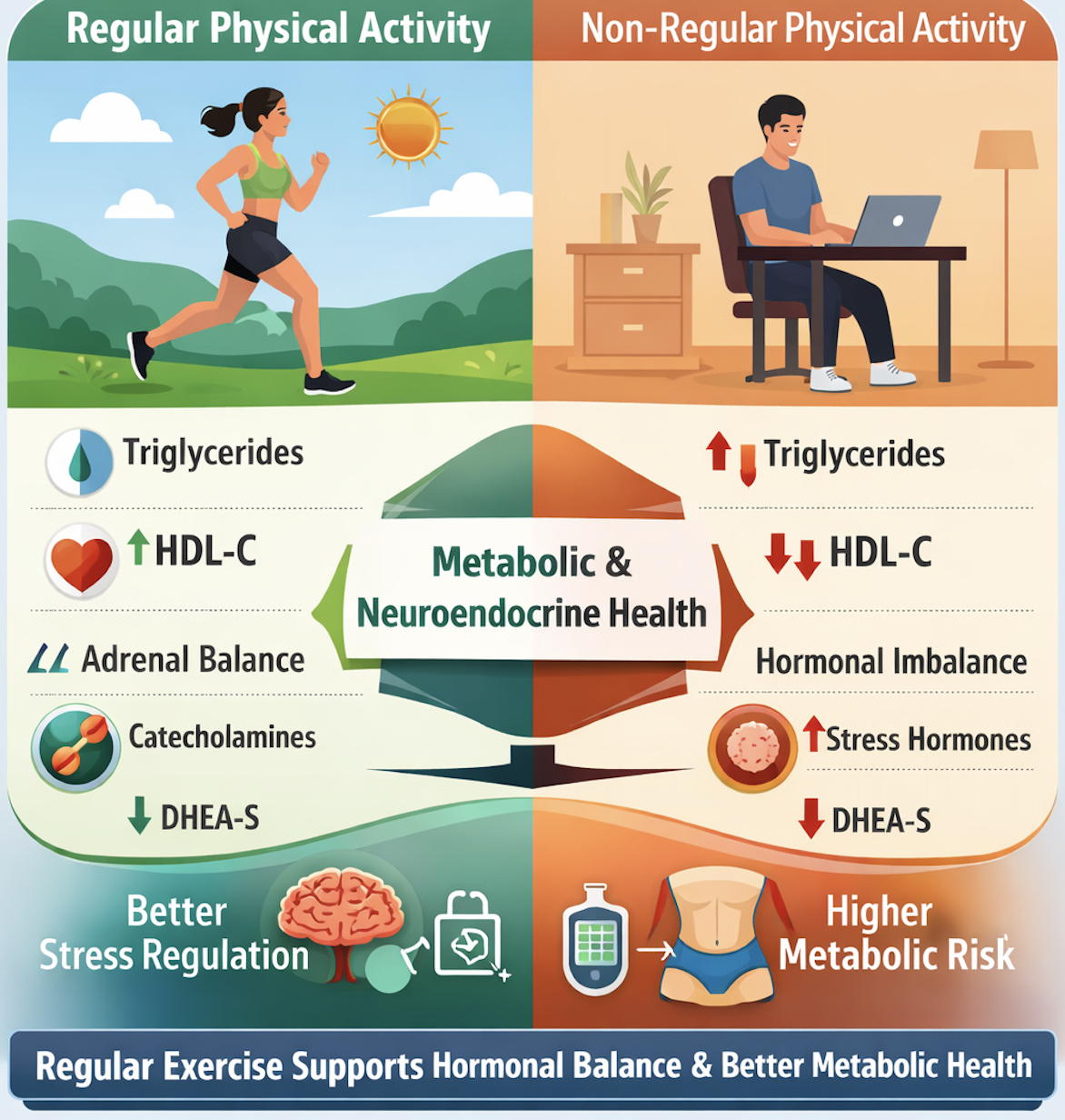

In conclusion, this exploratory investigation shows that, in healthy people, regular PA may support-stress regulatory mechanisms and protection against early metabolic dysregulation. Participants in the regular PA group exhibited a lower triglycerides and higher HDL-C levels compared with those in the non-regular PA group. Furthermore, in the regular PA group, the slightly increased in catecholamines and lower DHEA-S suggests that regular exercise may promote optimal adrenal responsiveness and anabolic – catabolic homeostasis. Collectively, these findings support the role of regular PA as a powerful behavioral regulator in maintaining metabolic and neuroendocrine health prior to the onset of overt metabolic disease.

Author Contributions

“Conceptualization, F.O. and A.B.; methodology, F.O., A.B. and P.M.W; software, P.M.W.; validation, A.B. and P.M.W formal analysis, F.O. and A.B.; investigation, PMW.; resources, P.M.W.; data curation, F.O., A.B., P.M.W.; writing—original draft preparation, F.O.; writing—review and editing, F.O., A.B., P.M.W.; visualization, F.O.; supervision, A.B. and PMW.; project administration, PMW.; funding acquisition, PMW. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by German Federal Institute of Sport Science on behalf of the Federal Ministry of the Interior of Germany realized within MiSpEx – the National Research Network for Medicine in Spine Exercise, grant number 080102A/11-2-14” and “The APC was funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation)—Projektnummer 491466077.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Potsdam, Germany, granted the final ethical approval on (May 6, 2013. No. 44/2012).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data containing potentially identified or sensitive patient information is restricted by European law (GDPR). The data used in this study containing clinical participants is unavailable in a public repository. However, data are available upon reasonable request to Pia-Maria Wippert (wippert@uni-potsdam.de).

Acknowledgments

The present study was supported by a PhD scholarship from the German Academic Exchange Services (DAAD, grant number: 57552340) to Francis Osei.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ACTH |

Adrenocorticotropic Hormone |

| AL |

Allostatic load |

| ALI |

Allostatic load Index |

| BMI |

Body Mass Index |

| COMT |

Catechol-O-Methyltransferase |

| CRH |

Corticotropin-Releasing Hormone |

| DHEAS |

Dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate |

| HDL-C |

High Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol |

| HIIT |

High Intensity Interval Training |

| HOMA |

Homeostasis Model Assessment Index |

| HPA axis |

Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal Axis |

| LBP |

Low Back Pain |

| LC/NE |

Locus Coeruleus/norepinephrine System |

| LDL-C |

Low Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol |

| MiSpEx |

Medicine in Spine Exercise Network |

| PA |

Physical Activity |

| PSA 3 |

Parallel Study 3 |

| SNS |

Sympathetic Nervous System |

| VAS |

Visual Analogue Scale |

| WHO |

World Health Organization |

References

- Alberti, K.; Eckel, R.; Grundy, S.; Zimmet, P.; Cleeman, J.; Donato, K.; Fruchart, J.; James, W.; Loria, C.; Smith, S. International Diabetes Federation Task Force on Epidemiology and Prevention; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; American Heart Association; World Heart Federation; International Atherosclerosis Society; International Association for the Study of Obesity Harmonizing the metabolic syndrome: a joint interim statement of the International Diabetes Federation Task Force on Epidemiology and Prevention; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; American Heart Association; World Heart Federation; International Atherosclerosis Society; and International Association for the Study of Obesity. Circulation 2009, 120(16), 1640–1645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Athanasiou, N.; Bogdanis, G. C.; Mastorakos, G. Endocrine responses of the stress system to different types of exercise. Reviews in endocrine & metabolic disorders 2023, 24(2), 251–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beckie, TM. A Systematic Review of Allostatic Load, Health, and Health Disparities. Biological Research For Nursing 2012, 14(4), 311–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bird, S. R.; Hawley, J. A. Update on the effects of physical activity on insulin sensitivity in humans. BMJ open sport & exercise medicine 2017, 2(1), e000143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Block, A., Schipf, S., Van der Auwera, S., Hannemann, A., Nauck, M., John, U., ... & Grabe, H. J. Sex and age-specific associations between major depressive disorder and metabolic syndrome in two general population samples in Germany. Nordic Journal of Psychiatry 2016, 70(8), 611–620. [CrossRef]

- Bogdanis, G. C.; Philippou, A.; Stavrinou, P. S.; Tenta, R.; Maridaki, M. Acute and delayed hormonal and blood cell count responses to high-intensity exercise before and after short-term high-intensity interval training. Research in sports medicine (Print) 2022, 30(4), 400–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bracken, R. M.; Brooks, S. Plasma catecholamine and nephrine responses following 7 weeks of sprint cycle training. Amino acids 2010, 38(5), 1351–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bull, F. C.; Al-Ansari, S. S.; Biddle, S.; Borodulin, K.; Buman, M. P.; Cardon, G.; Carty, C.; Chaput, J. P.; Chastin, S.; Chou, R.; Dempsey, P. C.; DiPietro, L.; Ekelund, U.; Firth, J.; Friedenreich, C. M.; Garcia, L.; Gichu, M.; Jago, R.; Katzmarzyk, P. T.; Lambert, E.; Willumsen, J. F. World Health Organization 2020 guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behaviour. British journal of sports medicine 2020, 54(24), 1451–1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, C. J.; Khurana, S.; Kumar, A.; Tai, T. C. Inflammatory Signaling in Hypertension: Regulation of Adrenal Catecholamine Biosynthesis. Frontiers in endocrinology 2018, 9, 343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.; Nakagawa, S.; An, Y.; Ito, K.; Kitaichi, Y.; Kusumi, I. The exercise-glucocorticoid paradox: How exercise is beneficial to cognition, mood, and the brain while increasing glucocorticoid levels. Frontiers in neuroendocrinology 2017, 44, 83–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Çınar, V.; Bağ, M. F.; Aslan, M.; Çınar, F.; Gennaro, A.; Akbulut, T.; Migliaccio, G. M. Impact of different exercise modalities on neuroendocrine well-being markers among university students: a study of renalase and catecholamine responses. Frontiers in physiology 2025, 16, 1591132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleven, L.; Dziuba, A.; Krell-Roesch, J.; Schmidt, S. C. E.; Bös, K.; Jekauc, D.; Woll, A. Longitudinal associations between physical activity and five risk factors of metabolic syndrome in middle-aged adults in Germany. Diabetology & metabolic syndrome 2023, 15(1), 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornelissen, V. A.; Smart, N. A. Exercise training for blood pressure: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of the American Heart Association 2013, 2(1), e004473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daniela, M.; Catalina, L.; Ilie, O.; Paula, M.; Daniel-Andrei, I.; Ioana, B. Effects of Exercise Training on the Autonomic Nervous System with a Focus on Anti-Inflammatory and Antioxidants Effects. Antioxidants (Basel, Switzerland) 2022, 11(2), 350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D'Alessio, L.; Korman, G. P.; Sarudiansky, M.; Guelman, L. R.; Scévola, L.; Pastore, A.; Obregón, A.; Roldán, E. J. A. Reducing Allostatic Load in Depression and Anxiety Disorders: Physical Activity and Yoga Practice as Add-On Therapies. Frontiers in psychiatry 2020, 11, 501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davy, K. P.; Orr, J. S. Sympathetic nervous system behavior in human obesity. Neuroscience and biobehavioral reviews 2009, 33(2), 116–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebert, S. N.; Rong, Q.; Boe, S.; Thompson, R. P.; Grinberg, A.; Pfeifer, K. Targeted insertion of the Cre-recombinase gene at the phenylethanolamine n-methyltransferase locus: a new model for studying the developmental distribution of adrenergic cells. Developmental dynamics: an official publication of the American Association of Anatomists 2004, 231(4), 849–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaffey, A. E.; Bergeman, C. S.; Clark, L. A.; Wirth, M. M. Aging and the HPA axis: Stress and resilience in older adults. Neuroscience and biobehavioral reviews 2016, 68, 928–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerber, M.; Pühse, U. Review article: do exercise and fitness protect against stress-induced health complaints? A review of the literature. Scandinavian journal of public health 2009, 37(8), 801–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giles, G. E.; Mahoney, C. R.; Brunyé, T. T.; Taylor, H. A.; Kanarek, R. B. Stress effects on mood, HPA axis, and autonomic response: comparison of three psychosocial stress paradigms. PloS one 2014, 9(12), e113618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldman, N.; Turra, C. M.; Glei, D. A.; Lin, Y. H.; Weinstein, M. Physiological dysregulation and changes in health in an older population. Experimental gerontology 2006, 41(9), 862–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruenewald, T. L.; Karlamangla, A. S.; Hu, P.; Stein-Merkin, S.; Crandall, C.; Koretz, B.; Seeman, T. E. History of socioeconomic disadvantage and allostatic load in later life. Social science & medicine (1982) 2012, 74(1), 75–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzzoni, V.; Sanches, A.; Costa, R.; de Souza, L. B.; Firoozmand, L. T.; de Abreu, I. C. M. E.; da Costa Guerra, J. F.; Pedrosa, M. L.; Casarini, D. E.; Marcondes, F. K.; Cunha, T. S. Stress-induced cardiometabolic perturbations, increased oxidative stress and ACE/ACE2 imbalance are improved by endurance training in rats. Life sciences 2022, 305, 120758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamer, M.; Steptoe, A. Cortisol responses to mental stress and incident hypertension in healthy men and women. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism 2012, 97(1), E29–E34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haufe, S.; Kerling, A.; Protte, G.; Bayerle, P.; Stenner, H. T.; Rolff, S.; Sundermeier, T.; Kück, M.; Ensslen, R.; Nachbar, L.; Lauenstein, D.; Böthig, D.; Bara, C.; Hanke, A. A.; Terkamp, C.; Stiesch, M.; Hilfiker-Kleiner, D.; Haverich, A.; Tegtbur, U. Telemonitoring-supported exercise training, metabolic syndrome severity, and workability in company employees: a randomised controlled trial. The Lancet. Public health 2019, 4(7), e343–e352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heaney, J. L.; Carroll, D.; Phillips, A. C. DHEA and cortisol responses to acute stress in healthy humans. Journal of Endocrinology 2012, 215(3), 419–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heaney, J. L.; Carroll, D.; Phillips, A. C. Physical activity, life events stress, cortisol, and DHEA: preliminary findings that physical activity may buffer against the negative effects of stress. Journal of aging and physical activity 2014, 22(4), 465–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heaney, J. L.; Carroll, D.; Phillips, A. C. DHEA, DHEA-S and cortisol responses to acute exercise in older adults in relation to exercise training status and sex. Age (Dordrecht, Netherlands) 2013, 35(2), 395–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, F.; Li, J.; Liu, Z.; Chuang, C. C.; Yang, W.; Zuo, L. Redox Mechanism of Reactive Oxygen Species in Exercise. Frontiers in physiology 2016, 7, 486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henson, J; Edwardson, CL; Morgan, B; Horsfield, MA; Bodicoat, DH; Biddle, SJ; Gorely, T; Nimmo, MA; McCann, GP; Khunti, K; Davies, MJ; Yates, T. Associations of Sedentary Time with Fat Distribution in a High-Risk Population. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2015, 47(8), 1727–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- James, K. A.; Stromin, J. I.; Steenkamp, N.; Combrinck, M. I. Understanding the relationships between physiological and psychosocial stress, cortisol and cognition. Frontiers in endocrinology 2023, 14, 1085950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, X.; Qiu, T.; Li, L.; Yu, R.; Chen, X.; Li, C.; Proud, C. G.; Jiang, T. Pathophysiology of obesity and its associated diseases. Acta pharmaceutica Sinica. B 2023, 13(6), 2403–2424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, C.; Gwenin, C. Cortisol level dysregulation and its prevalence-Is it nature's alarm clock? Physiological reports 2021, 8(24), e14644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Juster, R. P.; McEwen, B. S.; Lupien, S. J. Allostatic load biomarkers of chronic stress and impact on health and cognition. Neuroscience and biobehavioral reviews 2010, 35(1), 2–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kageyama, K.; Iwasaki, Y.; Daimon, M. Hypothalamic Regulation of Corticotropin-Releasing Factor under Stress and Stress Resilience. International journal of molecular sciences 2021, 22(22), 12242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanowski, C; Schorr, S; Schaefer, C; Menzel, C; Prien, P; Vader, I; Nothacker, M. Nationale Versorgungsleitlinie Nicht-spezifischer Kreuzschmerz. In Leitlinienreport; Äzq, AWMF-Registernr: nvl-007: Berlin, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Kivimäki, M.; Bartolomucci, A.; Kawachi, I. The multiple roles of life stress in metabolic disorders. Nature reviews. Endocrinology 2023, 19(1), 10–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreher, J. B.; Schwartz, J. B. Overtraining syndrome: a practical guide. Sports health 2012, 4(2), 128–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Rizvi, M. R.; Saraswat, S. Obesity and Stress: A Contingent Paralysis. International journal of preventive medicine 2022, 13, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Z. S.; Critchley, J. A.; Tomlinson, B.; Young, R. P.; Thomas, G. N.; Cockram, C. S.; Chan, T. Y.; Chan, J. C. Urinary epinephrine and norepinephrine interrelations with obesity, insulin, and the metabolic syndrome in Hong Kong Chinese. Metabolism: clinical and experimental 2001, 50(2), 135–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Fan, R.; Hao, Z.; Li, J.; Yang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Xia, Y. The Association Between Physical Activity and Insulin Level Under Different Levels of Lipid Indices and Serum Uric Acid. Frontiers in physiology 2022, 13, 809669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P. Z.; Nusslock, R. Exercise-Mediated Neurogenesis in the Hippocampus via BDNF. Frontiers in neuroscience 2018, 12, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malhotra, N.; Sinha, P.; Rathoria, R.; Rathoria, E. Corticotropin-releasing hormone. In FOGSI focus on harmony of hormones; Evangel Publishing, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Vizcaíno, V.; Cavero-Redondo, I.; Reina-Gutiérrez, S.; Gracia-Marco, L.; Gil-Cosano, J. J.; Bizzozero-Peroni, B.; Rodriguez-Artalejo, F.; Ubago-Guisado, E. Comparative effects of different types of exercise on health-related quality of life during and after active cancer treatment: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Journal of sport and health science 2023, 12(6), 726–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McEwen, B. S. Physiology and neurobiology of stress and adaptation: central role of the brain. Physiological reviews 2007, 87(3), 873–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McEwen, B. S.; Stellar, E. Stress and the individual. Mechanisms leading to disease. Archives of internal medicine 1993, 153(18), 2093–2101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina-Hidalgo, C.; Stillman, C. M.; Collins, A. M.; Velazquez-Diaz, D.; Ripperger, H. S.; Drake, J. A.; Gianaros, P. J.; Marsland, A. L.; Erickson, K. I. Changes in stress pathways as a possible mechanism of aerobic exercise training on brain health: a scoping review of existing studies. Frontiers in physiology 2023, 14, 1273981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osei, F.; Wippert, P. M.; Block, A. Allostatic Load and Metabolic Syndrome in Depressed Patients: A Cross-Sectional Analysis. Depression and anxiety 2024, 2024, 1355340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osei, F.; Block, A.; Wippert, P. M. Association of primary allostatic load mediators and metabolic syndrome (MetS): A systematic review. Frontiers in endocrinology 2022, 13, 946740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, S. B.; Blumenthal, J. A.; Lee, S. Y.; Georgiades, A. Association of cortisol and the metabolic syndrome in Korean men and women. Journal of Korean medical science 2011, 26(7), 914–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pedersen, B. K.; Saltin, B. Exercise as medicine - evidence for prescribing exercise as therapy in 26 different chronic diseases. Scandinavian journal of medicine & science in sports 2015, 25 Suppl 3, 1–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, A. C.; Carroll, D.; Gale, C. R.; Lord, J. M.; Arlt, W.; Batty, G. D. Cortisol, DHEA sulphate, their ratio, and all-cause and cause-specific mortality in the Vietnam Experience Study. European journal of endocrinology 2010, 163(2), 285–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, D.; Petrigna, L.; Pereira, F. C.; Muscella, A.; Bianco, A.; Tavares, P. The Impact of Physical Exercise on the Circulating Levels of BDNF and NT 4/5: A Review. International journal of molecular sciences 2021, 22(16), 8814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenberger Hale, E; Goff, DC; Isom, S; Blackwell, C; Whitt-Glover, MC; Katula, JA. Relationship of weekly activity minutes to metabolic syndrome in prediabetes: the healthy living partnerships to prevent diabetes. J Phys Act Health 2013, 10(5), 690–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ross, J. A.; Van Bockstaele, E. J. The Locus Coeruleus- Norepinephrine System in Stress and Arousal: Unraveling Historical, Current, and Future Perspectives. Frontiers in psychiatry 2021, 11, 601519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ross, R.; Goodpaster, B. H.; Koch, L. G.; Sarzynski, M. A.; Kohrt, W. M.; Johannsen, N. M.; Skinner, J. S.; Castro, A.; Irving, B. A.; Noland, R. C.; Sparks, L. M.; Spielmann, G.; Day, A. G.; Pitsch, W.; Hopkins, W. G.; Bouchard, C. Precision exercise medicine: understanding exercise response variability. British journal of sports medicine 2019, 53(18), 1141–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seeman, T.E.; McEwen, B.S.; Rowe, J.W.; Singer, B.H. Allostatic load as a marker of cumulative biological risk: MacArthur studies of successful aging. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2001, 98(8), 4770–4775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seeman, T. E.; Singer, B. H.; Rowe, J. W.; Horwitz, R. I.; McEwen, B. S. Price of adaptation--allostatic load and its health consequences. MacArthur studies of successful aging. Archives of internal medicine 1997, 157(19), 2259–2268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, M. W.; Eum, Y.; Jung, H. C. Leisure time physical activity: a protective factor against metabolic syndrome development. BMC public health 2023, 23(1), 2449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seplaki, C. L.; Goldman, N.; Glei, D.; Weinstein, M. A comparative analysis of measurement approaches for physiological dysregulation in an older population. Experimental gerontology 2005, 40(5), 438–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, D. K. Physiology of stress and its management. Journal of Medicine Study & Research 2018, 1(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, R. L.; Soeters, M. R.; Wüst, R. C. I.; Houtkooper, R. H. Metabolic Flexibility as an Adaptation to Energy Resources and Requirements in Health and Disease. Endocrine reviews 2018, 39(4), 489–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterling, P; Eyer, J. Allostasis: A new paradigm to explain arousal pathology. In Handbook of Life Stress, Cognition and Health.; Fisher, S, Reason, J, Eds.; John Wiley & Sons: New York, 1988; pp. pp 629–649. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, J.; Wang, S.; Zhang, J. Q.; Li, W. Assessing the cumulative effects of stress: The association between job stress and allostatic load in a large sample of Chinese employees. Work & Stress 2007, 21(4), 333–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torpy, JM; Lynm, C; Glass, RM. Chronic Stress and the Heart. JAMA. 2007, 298(14), 1722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warburton, D. E. R.; Bredin, S. S. D. Health benefits of physical activity: a systematic review of current systematic reviews. Current opinion in cardiology 2017, 32(5), 541–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiltink, J.; Michal, M.; Jünger, C.; Münzel, T.; Wild, P. S.; Lackner, K. J.; Blettner, M.; Pfeiffer, N.; Brähler, E.; Beutel, M. E. Associations between degree and sub-dimensions of depression and metabolic syndrome (MetS) in the community: results from the Gutenberg Health Study (GHS). BMC psychiatry 2018, 18(1), 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wippert, P.-M.; Honold, J.; Wang, V.; Kirschbaum, C. Assessment of chronic stress: Comparison of hair biomarkers and allostatic load indices. Psychology Research 2014, 4(7), 517–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wippert, P. M.; Puerto Valencia, L.; Drießlein, D. Stress and Pain. Predictive (Neuro)Pattern Identification for Chronic Back Pain: A Longitudinal Observational Study. Frontiers in medicine 2022, 9, 828954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wippert, P.-M.; Honold, J.; Wang, V.; Kirschbaum, C. Assessment of chronic stress: Comparison of hair biomarkers and allostatic load indices. Psychology Research 2014, 4(7), 517–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Won, E.; Kim, Y. K. Stress, the Autonomic Nervous System, and the Immune-kynurenine Pathway in the Etiology of Depression. Current neuropharmacology 2016, 14(7), 665–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; An, X.; Yang, C.; Sun, W.; Ji, H.; Lian, F. The crucial role and mechanism of insulin resistance in metabolic disease. Frontiers in endocrinology 2023, 14, 1149239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziegler, M. G.; Elayan, H.; Milic, M.; Sun, P.; Gharaibeh, M. Epinephrine and the metabolic syndrome. Current hypertension reports 2012, 14(1), 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zouhal, H.; Jacob, C.; Delamarche, P.; Gratas-Delamarche, A. Catecholamines and the effects of exercise, training and gender; Sports medicine: Auckland, N.Z.), 2008; Volume 38, 5, pp. 401–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics of study participants (n = 46, 100%).

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics of study participants (n = 46, 100%).

| Variables |

N |

% |

Median |

IQR |

Range |

| Age (years) |

45 |

97.8 |

30.00 |

15.00 |

25.00 |

| Sex |

|

| Male |

15 |

32.6 |

- |

- |

- |

| Female |

30 |

65.2 |

- |

- |

- |

| Primary mediators of AL |

|

|

| Cortisol (μg/d) |

46 |

100.0 |

113.55 |

73.70 |

238.60 |

| Epinephrine (μg/d) |

46 |

100.0 |

5.95 |

5.30 |

16.80 |

| Norepinephrine (μg/d) |

46 |

100.0 |

24.40 |

20.60 |

95.50 |

| DHEA-S (μg/ml) |

46 |

100.0 |

0.53 |

0.89 |

2.48 |

| Primary ALI |

46 |

100.0 |

1.00 |

2.00 |

4.00 |

| Anthropometry |

|

|

| BMI(kg/m2) |

44 |

95.7 |

22.29 |

3.13 |

13.07 |

| Waist circumference (cm) |

45 |

97.8 |

75.20 |

13.00 |

42.30 |

| Blood pressure |

|

|

|

|

|

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) |

45 |

97.8 |

100.00 |

13.75 |

50.00 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) |

45 |

97.8 |

60.00 |

10.00 |

35.00 |

| Lipid profile |

|

|

|

|

|

| Triglycerides (mg/dl) |

46 |

100.0 |

89.90 |

48.90 |

129.80 |

| HDL-C (mg/dl) |

46 |

100.0 |

62.25 |

17.60 |

59.50 |

| Glycemia |

|

|

|

|

|

| Fasting blood glucose (mg/dl) |

46 |

100.0 |

86.30 |

7.40 |

29.40 |

| Lifestyle habits |

|

|

|

|

|

| Leisure Sports (min/week) |

38 |

82.6 |

150.00 |

225.00 |

460.00 |

| Exercise (min/week) |

37 |

80.4 |

240.00 |

345.00 |

1275.00 |

| Total Physical Activity (PA) (min/week) |

43 |

93.5 |

330.00 |

453.00 |

1680.00 |

| MetS diagnosis |

|

|

|

|

|

| Yes |

2 |

4.3 |

- |

- |

- |

| No |

44 |

95.7 |

- |

- |

- |

| MetS criteria count |

46 |

100.0 |

0.00 |

1.00 |

3.00 |

| 1 biomarker |

7 |

15.2 |

- |

- |

- |

| 2 biomarkers |

4 |

8.7 |

- |

- |

- |

| 3 biomarkers |

2 |

4.3 |

- |

- |

- |

| 4 biomarkers |

0 |

0.0 |

- |

- |

- |

| 5 biomarkers |

0 |

0.0 |

- |

- |

- |

Table 2.

Differences between Anthropometric and biomarkers between regular PA and non-regular PA group.

Table 2.

Differences between Anthropometric and biomarkers between regular PA and non-regular PA group.

Variables

|

Regular PA

(n = 37) |

Non-regular PA

(n = 8) |

U |

Z |

p |

N

(%) |

Mdn |

Mean rank |

Sum of

Mean ranks |

N

(%) |

Mdn |

Mean rank |

Sum of

mean

ranks |

| Age |

37

(80.43) |

28.00 |

22.07 |

816.50 |

8

(17.40) |

37.50 |

27.31 |

218.50 |

110.500 |

-1.026 |

0.30 |

| Sex |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Male |

14

(30.43) |

- |

- |

- |

1

(2.17) |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

| Female |

23

(50.00) |

- |

- |

- |

7

(15.22) |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

| Anthropometry |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| BMI (kg/m2) |

35

(76.08) |

22.34 |

22.63 |

792.00 |

8

(17.40) |

21.92 |

19.25 |

154.00 |

118.000 |

-1.694 |

0.49 |

Waist circumference

(cm) |

36

(78.26) |

75.60 |

22.42 |

807.00 |

8

(17.40) |

79.10 |

22.88 |

183.00 |

141.000 |

-.091 |

0.92 |

| Primary Mediators of AL |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Cortisol (μg/12h) |

37

(80.43) |

130.60 |

25.35 |

938.00 |

8

(17.40) |

71.50 |

12.13 |

97.00 |

61.000 |

-2.583 |

0.01 |

| Epinephrine (μg/12h) |

37

(80.43) |

7.00 |

24.27 |

898.00 |

8

(17.40) |

4.40 |

17.13 |

137.00 |

101.000 |

-1.396 |

0.16 |

| Norepinephrine (μg/12h) |

37

(80.43) |

25.30 |

23.89 |

884.00 |

8

(17.40) |

19.00 |

18.88 |

151.00 |

115.000 |

-.980 |

0.32 |

| DHEA-S (μg/ml) |

37

(80.43) |

0.50 |

22.38 |

828.00 |

8

(17.40) |

0.69 |

25.88 |

207.00 |

125.000 |

-.683 |

0.49 |

| Primary ALI |

37

(80.43) |

1.00 |

23.41 |

866.00 |

8

(17.40) |

0.50 |

21.13 |

169.00 |

133.000 |

-.473 |

0.63 |

| Blood Pressure |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Systolic blood

pressure (mmHg) |

36

(78.26) |

100.00 |

21.68 |

780.50 |

8

(17.40) |

102.50 |

26.19 |

209.50 |

114.500 |

-.909 |

0.36 |

Diastolic blood

pressure (mmHg) |

36

(78.26) |

60.00 |

22.36 |

805.00 |

8

(17.40) |

60.00 |

23.13 |

185.00 |

139.000 |

-.167 |

0.86 |

| Lipid Profiles |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Triglycerides (mg/dl) |

37

(80.43) |

87.70 |

21.58 |

798.50 |

8

(17.40) |

110.95 |

29.56 |

236.50 |

95.500 |

-1.559 |

0.11 |

| HDL-C (mg/dl) |

37

(80.43) |

65.70 |

23.84 |

882.00 |

8

(17.40) |

59.55 |

19.13 |

153.00 |

117.000 |

-.921 |

0.35 |

| Glycemia |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Fasting blood

Glucose (mg/dl) |

37

(80.43) |

86.30 |

22.61 |

836.50 |

8

(17.40) |

86.05 |

24.81 |

198.50 |

133.500 |

-.431 |

0.66 |

| Total Physical Activity (min/wk) |

37

(80.43) |

420.00 |

24.04 |

889.50 |

6

(13.04) |

135.00 |

9.42 |

56.50 |

35.500 |

-2.648 |

0.008 |

MetS present

count

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 0-2 biomarkers |

36 (78.26) |

- |

- |

- |

7

(15.22) |

- |

- |

-

-

|

- |

- |

- |

| 3-5 biomarkers |

1

(2.17) |

- |

- |

- |

1

(2.17) |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |