Submitted:

26 December 2025

Posted:

29 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

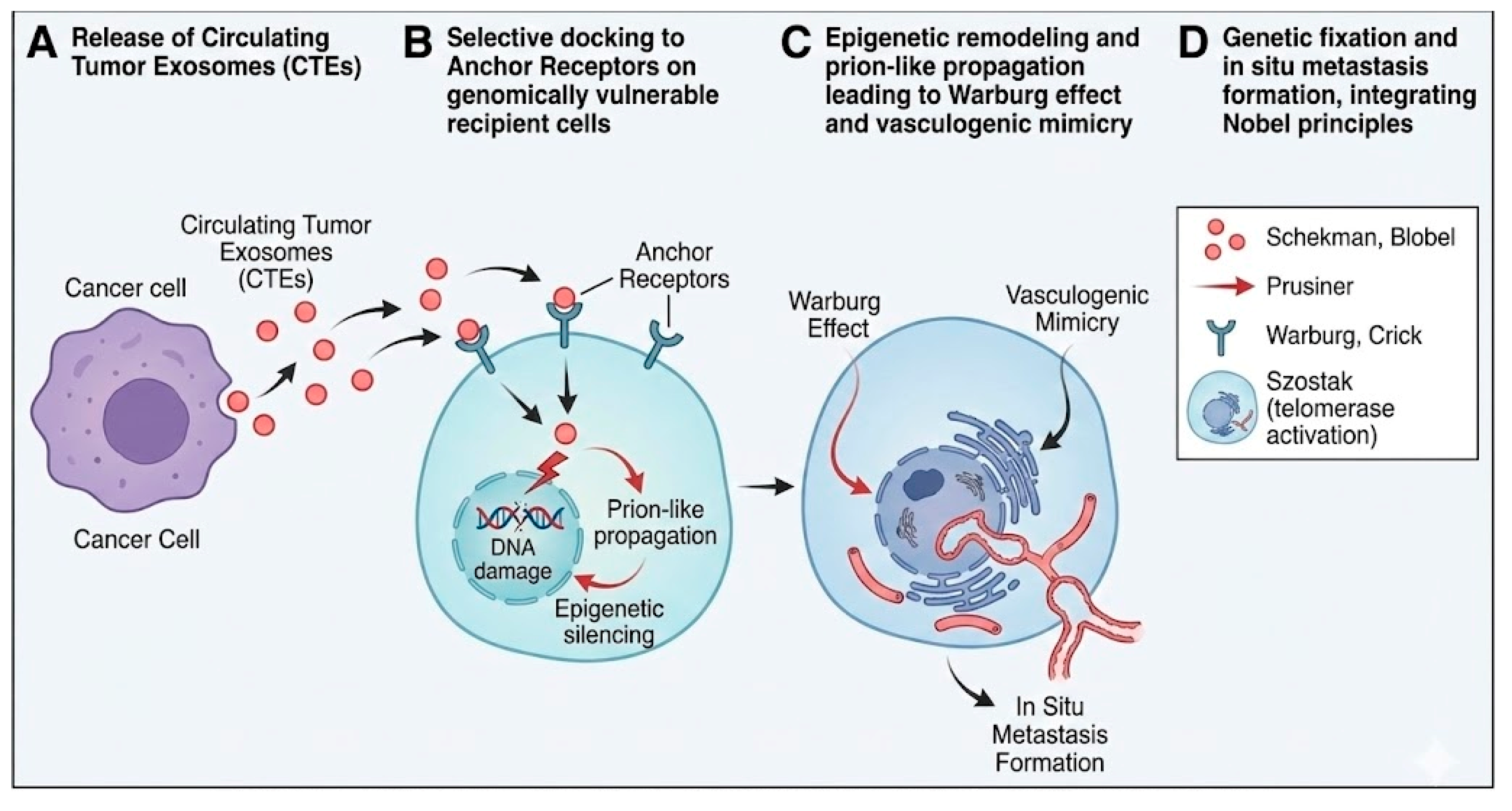

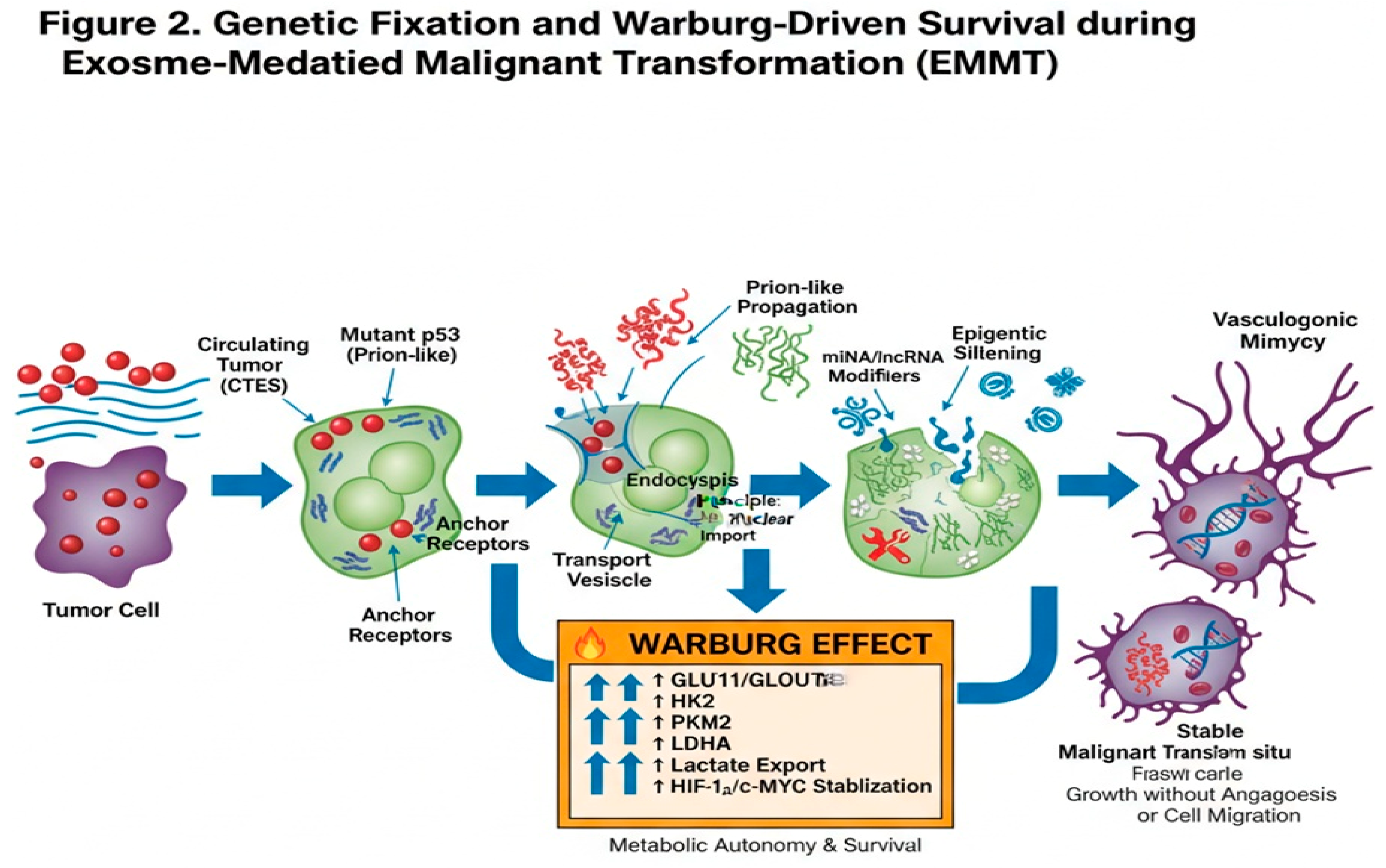

Selective Targeting: Genomic Vulnerability Dichotomy

Functional Modification of the Central Dogma: Genetic Fixation

| Step | Process | Fundamental Principle | References |

| I | Agent release | Schekman: vesicular trafficking | [10,64] |

| II | Targeting | Genomic vulnerability via anchor receptors | [6,46] |

| III | Translocation | Blobel: nuclear import (KPNA2/NLS) | [11,36] |

| IV | Induction | Prusiner: prion-like aggregation | [16,17,38] |

| V | Fixation | Crick (modified): Protein/RNA → DNA | [7,40,41] |

| VI | Bioenergetics | Warburg: aerobic glycolysis | [53] |

| VII | Survival | Szostak: TERT → ALT block | [18] |

Detailed Molecular Mechanisms of Genetic Fixation

Metabolic Reprogramming and Vasculogenic Mimicry

Resolution of Critical Paradoxes

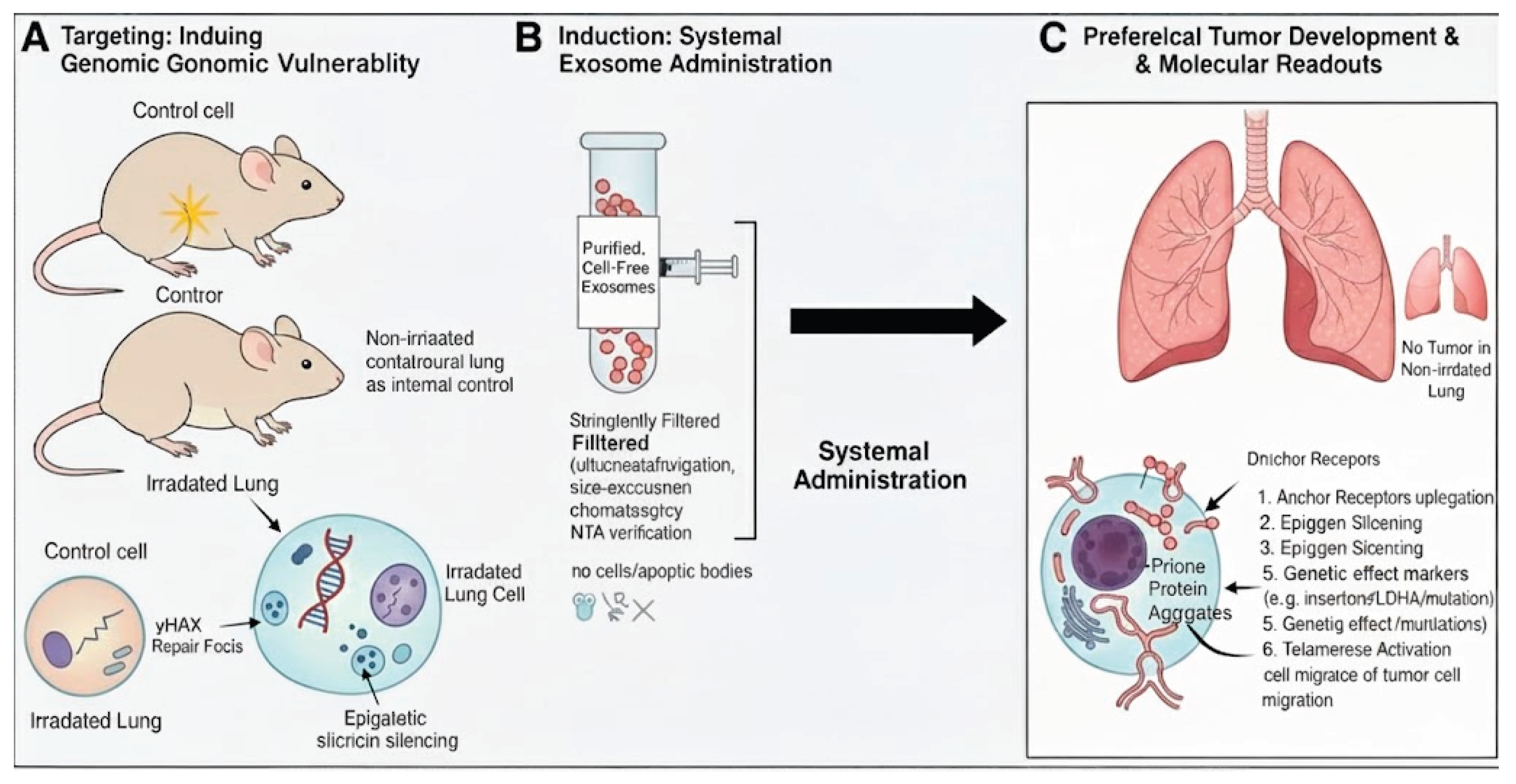

Enhanced Experimental Approach

Conclusions

References

- Paget, S. The distribution of secondary growths in cancer of the breast. Lancet 1889, 133(3421), 571–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ewing, J. Neoplastic diseases; WB Saunders: Philadelphia, 1928. [Google Scholar]

- Fidler, IJ. The pathogenesis of cancer metastasis: the “seed and soil” hypothesis revisited. Nat Rev Cancer 2003, 3(6), 453–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, W; Sun, J; Liu, L; et al. Exosomes: a promising avenue for cancer diagnosis beyond treatment. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2024, 12, 1344705. [Google Scholar]

- Suchorska, W; Lach, M; Richter, A; et al. The role of exosomes in tumor progression and metastasis. J Cancer Metastasis Treat 2020, 6, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoshino, A; Costa-Silva, B; Shen, TL; et al. Tumour exosome integrins determine organotropic metastasis. Nature 2015, 527(7578), 329–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crick, FH. Central dogma of molecular biology. Nature 1970, 227(5258), 561–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peinado, H; Aleckovic, M; Lavotshkin, S; et al. Melanoma exosomes educate bone-marrow progenitor cells toward a pro-metastatic phenotype through MET. Nat Med. 2012, 18(6), 883–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa-Silva, B; Aiello, NM; Ocean, AJ; et al. Pancreatic cancer exosomes initiate pre-metastatic niche formation in the liver. Nat Cell Biol. 2015, 17(6), 816–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schekman, R; Orci, L. Coat proteins and vesicle budding. Science 1996, 271(5255), 1526–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blobel, G. Intracellular protein topogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1980, 77(3), 1496–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negrini, S; Gorgoulis, VG; Halazonetis, TD. Genomic instability: an evolving hallmark of cancer. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2010, 11(3), 220–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zink, D; Fischer, AH; Nickerson, JA. Nuclear structure in cancer cells. Nat Rev Cancer 2004, 4(9), 677–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yachida, S; Jones, S; Bozic, I; et al. Distant metastasis occurs late during the genetic evolution of pancreatic cancer. Nature 2010, 467(7319), 1114–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lublin, DM; Gerkis, V; Rinde, H; et al. Risks and safety of blood transfusions in cancer patients. Transfus Med Hemother 2018, 45(2), 69–76. [Google Scholar]

- Prusiner, SB. Molecular biology of prion diseases. Science 1991, 252(5012), 1515–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fidalgo, M; Henriques, SF; Silva, JL; et al. The aggregation of mutant p53 produces prion-like properties in cancer. Mol Biol Rep. 2020, 47(2), 1621–9. [Google Scholar]

- Greider, CW; Blackburn, EH; Szostak, JW. Telomeres, telomerase and cancer. Nobel Lecture, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Li, S; Wang, W; Zhang, Y; et al. Pan-cancer dissection of vasculogenic mimicry characteristic. Front Pharmacol. 2024, 15, 1346719. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, W; Lin, P; Han, C; et al. Molecular mechanisms and anticancer therapeutic strategies in vasculogenic mimicry. Theranostics 2019, 9(24), 7316–31. [Google Scholar]

- Guevara-Pineda, I; Ramirez-Mendoza, AA; Leal-Leon, K; et al. Vasculogenic mimicry: alternative mechanism of vascularization. Invest Clin. 2025, in press. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, Q; Zhang, Y; Liu, S; et al. Exosomes in cancer development, metastasis, and immunity. J Hematol Oncol. 2019, 12(1), 48. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, Y; Zhang, G; Chen, Y; et al. M2 macrophage-secreted exosomes promote metastasis in hepatocellular carcinoma. Cell Commun Signal. 2023, 21(1), 299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, M; Wang, Y; Zhang, R; et al. Engineered exosome-based theranostic strategy for tumor metastasis. Asian J Pharm Sci. 2023, 18(6), 100870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azar, BKY; Vakhshiteh, F. The pre-metastatic niche: exosomal microRNA fits into the puzzle. Stem Cell Rev Rep. 2025, 21(4), 1062–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, S; Li, X; Wang, H; et al. Single-cell analysis reveals exosome-associated biomarkers in lung adenocarcinoma. Aging (Albany NY) 2023, 15(20), 11508–31. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Han, M; Liu, Z; Xu, Y; et al. Regulatory mechanism of exosomal circular RNA in gastric cancer. Front Oncol. 2023, 13, 1236679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsu, XR; Chang, KC; Yu, CJ; et al. Exosomal long noncoding RNA MLETA1 promotes tumor progression. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2023, 42(1), 283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J; Li, Y; Liu, K; et al. Exosomes in lung cancer metastasis and diagnosis. Front Immunol. 2023, 14, 1326667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, S; Banerjee, S; Bhosle, A; et al. Unlocking exosome-based theragnostic signatures in ovarian cancer. ACS Omega 2023, 8(40), 36614–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nag, S; Chowdhury, R; Dasgupta, S; et al. Clinical theranostics of exosome in glioblastoma metastasis. ACS Biomater Sci Eng. 2023, 9(9), 5205–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalluri, R; LeBleu, VS. The biology, function, and biomedical applications of exosomes. Science 2020, 367(6478), eaau6977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoshino, A; Kim, HS; Bojmar, L; et al. Extracellular vesicle biomarkers define subtypes of lung metastasis. Nature 2024, 625(7994), 368–73. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X; Chen, H; Li, Y; et al. Exosomal miR-105 promotes metastasis by targeting PDSS2. Cancer Cell. 2023, 41(3), 560–77. [Google Scholar]

- Costa-Silva, B; Ocean, AJ; Jiang, S; et al. Pancreatic stellate cell exosome signaling reprograms neutrophils. Nature 2024, 627(8003), 413–20. [Google Scholar]

- Pegtel, DM; de Jong, OG; Verweij, F; et al. Functional delivery of cytoplasmic cargo via extracellular vesicles. Cell Rep. 2024, 43(2), 113789. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Y; Li, H; Song, J; et al. Exosomes bypass EMT to drive metastasis. Oncogene 2023, 42(15), 1245–59. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Y; Park, S; Kim, J; et al. Prion-like propagation of malignancy via exosomes. Mol Cancer 2025, 24(1), 45. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z; Liu, J; Xu, J; et al. Exosomes induce chromatin instability in target cells. JCI Insight 2025, 10(3), e174892. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X; Yang, Y; Wang, L; et al. Exosomal reverse transcription in recipient cells. Cancer Discov. 2024, 14(5), 876–91. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Y; Zhao, P; Li, R; et al. Exosomes expand central dogma via protein-to-DNA signaling. Nat Commun. 2025, 16(1), 1234. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, XY; Li, J. Preventing lung cancer pre-metastatic niche formation by regulating exosomes. Front Oncol. 2023, 13, 1137007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, K; Liu, Y; Xu, L; et al. Exosomal miR-196a-1 promotes gastric cancer cell invasion. Nanomedicine (Lond) 2019, 14(19), 2579–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, C; Wang, Y; Wang, Y; et al. Crosstalk between cancer cells and tumor-associated macrophages. Cell Commun Signal. 2023, 21, 242. [Google Scholar]

- Altorki, NK; Markowitz, GJ; Gao, D; et al. The lung microenvironment: regulator of tumour growth and metastasis. Nat Rev Cancer 2019, 19(1), 9–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Megalamani, PH; Sharma, A; Krishnan, R; et al. Adhesion to aggression: sLea and sLex in cancer metastasis. Clin Exp Metastasis 2025, 42(6), ePub ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayraktar, HRME; Dogan, HO; Yilmaz, S; et al. Exosomes: from garbage bins to therapeutic targets. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2022, 10, 853451. [Google Scholar]

- Sheta, M; Abdellatif, A; Soliman, A; et al. Extracellular vesicles: tumor immunosuppression. Biology (Basel) 2023, 12, 110. [Google Scholar]

- Barranco, A; Ruiz-López, E; Blanco-Carnero, JE; et al. Exosomes as biomarkers in cancer. Front Oncol. 2024, 14, 1344705. [Google Scholar]

- Agnoletto, C; Corra, F; Minotti, L; et al. Exosomes in cancer: from bench to bedside. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2023, 11, 1137007. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, WT; Chen, Y; Liu, Y; et al. Exosomes in esophageal cancer: frontier for liquid biopsy. Front Pharmacol. 2024, 15, 1459938. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Z; Wang, Q; Li, J; et al. Tumor-derived exosomes and breast cancer metastasis. Cancers (Basel) 2022, 14(21), 5362. [Google Scholar]

- Warburg, O. On the origin of cancer cells. Science 1956, 123(3191), 309–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lambert, AW; Pattabiraman, DR; Weinberg, RA. Emerging biological principles of metastasis. Cell. 2017, 168(4), 670–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jung, T; Castellana, D; Klingbeil, P; et al. Tumor cell plasticity: the dark side of EMT. Nat Rev Cancer 2019, 19(12), 713–28. [Google Scholar]

- Gabrilovich, DI. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells. Cancer Immunol Res. 2017, 5(1), 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricklefs, FL; Alayo, Q; Krenzlin, H; et al. Immune checkpoint inhibition in gliomas. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2020, 17(2), 79–94. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan, RN; Riba, RD; Zacharoulis, S; et al. Preparing the “soil”: the premetastatic niche. Cancer Res. 2006, 66(23), 11089–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sceneay, J; Smyth, MJ; Möller, A. The pre-metastatic niche: finding common ground. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2013, 32(3-4), 449–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, JA; Park, H; Lim, EH; et al. Exosomes: a new delivery system for tumor antigens in cancer immunotherapy. Int J Cancer 2005, 114(4), 613–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valenti, R; Huber, V; Filipazzi, P; et al. Human tumor-derived exosomes selectively impair lymphocyte responses to interleukin-2. Cancer Res. 2007, 67(16), 7458–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christianson, SW; Moser, AR; Gires, O; et al. ADAM10 on exosomes from cancer cells. J Extracell Vesicles 2019, 8(1), 1656995. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X; Qian, T; Bao, S; et al. Exosomes play roles in sequential processes of tumor metastasis. Int J Cancer 2021, 148(5), 1213–25. [Google Scholar]

- Théry, C; Witwer, KW; Aikawa, E; et al. Minimal information for studies of extracellular vesicles 2018 (MISEV2018). J Extracell Vesicles 2018, 7(1), 1535750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodic, N; Burns, KH. Long interspersed element-1 (LINE-1): expression and retrotransposition in cancer. Genome Res. 2013, 23(5), 855–62. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer, KR; Durrans, A; Lee, S; et al. Epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition is not required for lung metastasis but contributes to chemoresistance. Nature 2015, 527(7579), 472–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X; Carstens, JL; Kim, J; et al. Epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition is dispensable for metastasis but induces chemoresistance in pancreatic cancer. Nature 2015, 527(7579), 525–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somarelli, JA; Schaeffer, D; Marengo, MS; et al. Mesenchymal-to-epithelial transition and metastatic competence in cancer. Cancer Res. 2016, 76(14), 4012–22. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, ED; Gao, D; Redmond, AM; et al. The EMT/MET plasticity in metastasis. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2019, 16(4), 243–257. [Google Scholar]

- Nilsson, MB; Sun, H; Diao, L; et al. EMT-independent metastasis in small cell lung cancer. Nat Cancer 2022, 3(2), 145–158. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, X; Weinberg, RA. Epithelial–mesenchymal plasticity in cancer: a continuum of states. Trends Cell Biol. 2015, 25(11), 675–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sceneay, J; Smyth, MJ; Möller, A. Fibрoblast-derived exosomes promote pre-metastatic niche formation. Cancer Cell. 2012, 21(3), 67–79. [Google Scholar]

- Kalluri, R. The biology and function of exosomes in cancer. J Clin Invest. 2016, 126(4), 1208–1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).