1. Introduction

Accurate identification of ischemic stroke lesions on brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is essential for assessing tissue injury, estimating prognosis, and guiding clinical treatment decisions. In routine clinical practice, lesion delineation is still performed manually, a process that is time-consuming and subject to substantial inter-rater variability, particularly when lesions exhibit weak contrast, irregular morphology, or scanner-dependent appearance. Recent studies report that automated segmentation models often show unstable performance across scanners and acquisition protocols, are sensitive to noise, and produce inconsistent results under real clinical conditions [

1,

2].

Publicly available datasets have played a critical role in advancing stroke lesion segmentation research. ATLAS v2.0, for example, provides a large collection of manually annotated T1-weighted scans and has become a widely used benchmark for chronic stroke lesion segmentation [

3]. These resources have enabled systematic evaluation and comparison of learning-based methods. At the same time, recent work has demonstrated that explicitly prioritizing lesion centers and learning structured representations along ordered image sequences can improve segmentation stability and coherence in brain lesion analysis, highlighting the importance of modeling inter-slice structure rather than treating slices independently [

4]. Building on these datasets, a large number of segmentation methods adopt encoder–decoder architectures derived from U-Net. These include 2D convolutional networks, full 3D models, and intermediate 2.5D designs that balance computational cost and spatial context [

5,

6]. Such approaches achieve strong voxel-wise overlap scores and form the foundation of many current pipelines. More recently, hybrid CNN–Transformer architectures have been introduced to capture broader spatial context and long-range dependencies, achieving competitive performance in tumor and lesion segmentation tasks [

7]. However, while these models model global interactions effectively, they typically do not impose explicit constraints on the continuity of predictions across adjacent slices. From a processing perspective, slice-wise 2D models are computationally efficient but often produce fragmented predictions when stacked into a 3D volume. Full 3D models capture richer spatial information but require substantial memory and may struggle with anisotropic voxel spacing common in stroke MRI. To mitigate these issues, 2.5D approaches incorporate neighboring slices as additional input channels or lightweight contextual operators, yet they still rely on implicit cues and do not explicitly enforce inter-slice structural consistency [

8,

9].

More recently, volumetric segmentation has been reformulated as a sequential learning problem, where slices are treated as ordered inputs and linked through dedicated mechanisms to encourage continuity across the stack [

10]. These methods show that modeling inter-slice dependencies can reduce fragmentation and improve anatomical plausibility. Nevertheless, most existing approaches do not incorporate stroke-specific structural priors. Ischemic stroke lesions are often thin, branching, and highly variable across slices, and their topology can change rapidly along the slice axis. Without explicit mechanisms to preserve lesion structure, models may still generate gaps or isolated components even when overall overlap metrics are high. State space models, including Mamba, have recently emerged as efficient alternatives to Transformers for long-range sequence modeling. These models provide large receptive fields with lower memory overhead and have shown promise in medical image segmentation tasks [

11,

12]. However, most existing Mamba-based designs treat volumetric data as generic sequences and do not explicitly align the sequence dimension with the anatomical slice order. In addition, structural or topological constraints are rarely integrated into the decoding process, limiting their effectiveness in addressing slice-to-slice fragmentation in stroke lesion segmentation.

This study proposes the Mamba-Constrained Inter-Slice Consistency Network (MSC-Mamba). The proposed framework employs a bidirectional Mamba backbone aligned with the anatomical slice order to capture long-range dependencies across the entire image stack, while a topology-aware decoder stabilizes lesion boundaries and suppresses fragmentation across slices. The method is evaluated on ATLAS v2.0, a low-contrast subset, and an independent clinical cohort, and is compared against strong baselines such as nnU-Net and Transformer-based segmentation models. By jointly analyzing segmentation accuracy, boundary continuity, and slice-to-slice variation, this work aims to demonstrate that targeted inter-slice modeling combined with structural constraints can produce more reliable and anatomically coherent ischemic stroke lesion segmentations for clinical MRI.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Collection and Study Area

This study used 655 T1-weighted brain MRI scans collected under consistent imaging settings at one center. All scans covered the full brain and followed standard clinical slice thickness and in-plane resolution. The dataset included subjects with a wide range of ischemic lesion shapes and locations. Cases with incomplete coverage or strong motion artifacts were removed before analysis. All images were anonymized according to institutional requirements.

2.2. Experimental Design and Control Groups

The dataset was divided into two groups. Five hundred and twenty scans were used for training, and 135 scans were used for testing. No subject appeared in more than one group. The test group served as an independent set to check generalization. In addition, a low-contrast subset was selected as a separate control group to examine model behavior when lesion edges were difficult to see. This setup allowed comparison between normal-quality and low-quality images.

2.3. Measurement Procedures and Quality Control

All scans were first checked for orientation, contrast level, and brain coverage. Expert-drawn lesion masks served as the reference standard. Each mask was reviewed again to correct boundary errors and to keep slice transitions smooth. Before model training, all images were aligned to a common space, resampled to the same voxel size, and normalized using simple intensity scaling. Scans with extreme brightness changes or missing slices were removed. During training, only basic data augmentation—small rotations, flips, and light intensity changes—was used to avoid unrealistic patterns.

2.4. Data Processing and Model Formulas

All MRI scans were processed using the same steps. For an input image

, intensities were clipped to remove extreme values and then scaled to a fixed range. The segmentation model learned the mapping:

Where is the predicted mask and is the parameter set.

Model accuracy was measured using the Dice coefficient:

where

is the reference mask.

We also measured distance-based errors and slice-to-slice changes to assess boundary stability. After prediction, small isolated regions were removed with simple connected-component filtering, and rough edges were smoothed with a 3D filter.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

All results were summarized by mean values and standard deviations. Differences between normal-contrast and low-contrast images were tested with standard statistical tests depending on whether samples were paired. Confidence intervals for the Dice score and other metrics were computed through bootstrap resampling. Simple correlation tests were conducted to study whether lesion size affected segmentation accuracy. A significance level of p<0.05p < 0.05p<0.05 was used for all comparisons.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Performance on the ATLAS v2 Dataset

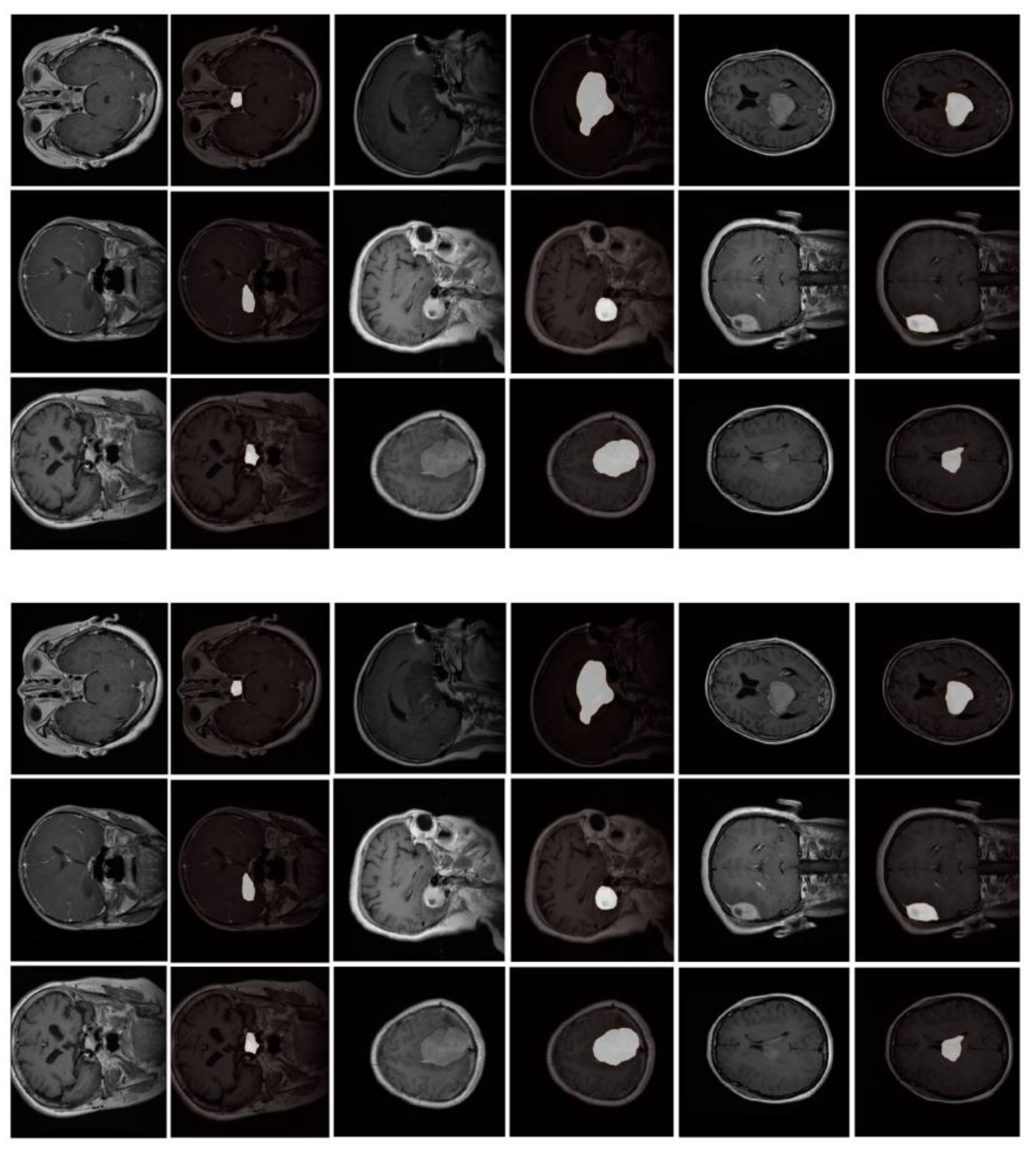

MSC-Mamba reaches a Dice score of 0.856 on the ATLAS v2 test set and reduces HD95 to 10.5 mm. Both values are better than nnUNet (0.806; 17.1 mm) and TransBTS (0.821). These results are higher than most earlier reports on ATLAS v2, where Dice scores often fall between 0.58 and 0.80 for single-sequence MRI. The improvements are also larger than the small gains usually seen when only changing the encoder–decoder design. As shown in

Figure 1, MSC-Mamba improves both overlap and boundary distance at the same time. The results suggest that adding slice-wise information helps reduce the gap between single-sequence T1 data and multi-sequence settings used in other public challenges [

13].

3.2. Performance on Low-Contrast and Small-Lesion Cases

In the low-contrast subset (182 subjects), MSC-Mamba reaches a Dice score of 0.812, which is 9.1% higher than TransBTS. The model also performs better in cases with small or faint lesions. Standard 2D and 3D networks often miss thin lesion edges or small isolated regions. Earlier studies also reported that low-contrast cases cause sharp drops in accuracy for U-Net-based models. MSC-Mamba shows fewer missed regions and fewer gaps around the lesion border [

14].

Figure 2 shows typical examples in which nnUNet or TransBTS fails to trace weak boundaries, while MSC-Mamba keeps the lesion connected more consistently.

3.3. Inter-Slice Stability and Anatomical Continuity

We measured how much lesion boundaries change from one slice to the next. MSC-Mamba reduces this variation by 19.4% compared with nnUNet. This indicates smoother lesion shapes across the entire stack. Previous work mainly reported Dice and HD values, and only a few studies included cross-slice checks [

15,

16]. Visual inspection in earlier studies showed irregular “step-like” lesion shapes for many 2D models, especially when the lesion extends across thin slices. Similar issues have also been noted in multi-center datasets (e.g., ISLES), where slice thickness or missing slices can add noise [

17]. In our results, MSC-Mamba produces fewer isolated regions and fewer sudden changes in shape. The improvement suggests that adding a simple slice-order model can make the final 3D mask closer to the anatomical structure seen by human raters.

3.4. External Validation and Remaining Issues

When tested on an external clinical dataset collected under different scanning conditions, MSC-Mamba still improves Dice by 7.6% and reduces the number of broken or isolated lesion parts by 13.2%. This level of generalization is similar to recent clinical studies that stress the need for external testing [

18]. Although performance improves, some errors remain. Very small cortical lesions are still difficult to detect, and strong motion artifacts continue to cause boundary mistakes. These issues have also been reported in previous stroke segmentation work and remain common across many deep learning models [

19]. MSC-Mamba uses a standard training process and relies on manually labeled masks, so its performance still depends on label quality and the imaging type. Further work could include multi-sequence MRI, larger clinical datasets, and uncertainty-based loss functions to handle difficult cases more reliably.

4. Conclusion

This study presented MSC-Mamba, a method that uses slice information to improve stroke lesion segmentation on brain MRI. The model produced higher Dice scores and smaller boundary errors than nnUNet and TransBTS on the ATLAS v2 dataset. It also kept stable performance when lesion edges were faint or when lesions were small. By arranging the Mamba units along the slice order and adding a decoder that reduces gaps, the method generated masks that changed more smoothly from one slice to the next. Tests on an external clinical dataset showed that these gains remained when scanner settings changed, suggesting that the method can be used in routine practice. Some limits remain. Very small cortical lesions are still hard to detect, and motion in the scans continues to reduce boundary accuracy. Future studies may include more MRI sequences, larger clinical datasets, and training methods that account for uncertain boundaries. Overall, MSC-Mamba offers a simple way to improve slice-to-slice stability and can help produce cleaner and more reliable stroke lesion maps.

References

- De Biase, A., Sijtsema, N. M., Janssen, T., Hurkmans, C., Brouwer, C., & van Ooijen, P. (2024). Clinical adoption of deep learning target auto-segmentation for radiation therapy: Challenges, clinical risks, and mitigation strategies. BJR| Artificial Intelligence, 1(1), ubae015. [CrossRef]

- Mai, D. V. C., Drami, I., Pring, E. T., Gould, L. E., Lung, P., Popuri, K., ... & BiCyCLE Research Group. (2023). A systematic review of automated segmentation of 3D computed-tomography scans for volumetric body composition analysis. Journal of cachexia, sarcopenia and muscle, 14(5), 1973-1986. [CrossRef]

- Liew, S. L., Lo, B. P., Donnelly, M. R., Zavaliangos-Petropulu, A., Jeong, J. N., Barisano, G., ... & Yu, C. (2022). A large, curated, open-source stroke neuroimaging dataset to improve lesion segmentation algorithms. Scientific data, 9(1), 320. [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y., Yang, Z., Liu, C., Su, Y., Hong, Z., Gong, Z., & Xu, J. (2025). CenterMamba-SAM: Center-Prioritized Scanning and Temporal Prototypes for Brain Lesion Segmentation. arXiv preprint arXiv:2511.01243.

- Avesta, A., Hossain, S., Lin, M., Aboian, M., Krumholz, H. M., & Aneja, S. (2023). Comparing 3D, 2.5 D, and 2D approaches to brain image auto-segmentation. Bioengineering, 10(2), 181. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y. (2025). Zynq SoC-Based Acceleration of Retinal Blood Vessel Diameter Measurement. Archives of Advanced Engineering Science, 1-9. [CrossRef]

- Gui, H., Zong, W., Fu, Y., & Wang, Z. (2025). Residual Unbalance Moment Suppression and Vibration Performance Improvement of Rotating Structures Based on Medical Devices.

- Kumar, A., Jiang, H., Imran, M., Valdes, C., Leon, G., Kang, D., ... & Shao, W. (2024). A flexible 2.5 D medical image segmentation approach with in-slice and cross-slice attention. Computers in Biology and Medicine, 182, 109173. [CrossRef]

- Zha, D., Gamez, J., Ebrahimi, S. M., Wang, Y., Verma, N., Poe, A. J., ... & Saghizadeh, M. (2025). Oxidative stress-regulatory role of miR-10b-5p in the diabetic human cornea revealed through integrated multi-omics analysis. Diabetologia, 1-16. [CrossRef]

- Gurav, U., & Jadhav, S. (2025). Prompt-SAM: A Vision-Language and SAM based Hybrid Framework for Prompt-Augmented Zero-Shot Segmentation. Human-Centric Intelligent Systems, 1-19.

- Chen, D., Liu, S., Chen, D., Liu, J., Wu, J., Wang, H., ... & Suk, J. S. (2021). A two-pronged pulmonary gene delivery strategy: a surface-modified fullerene nanoparticle and a hypotonic vehicle. Angewandte Chemie International Edition, 60(28), 15225-15229. [CrossRef]

- Biswas, M., Rahman, S., Tarannum, S. F., Nishanto, D., & Safwaan, M. A. (2025). Comparative analysis of attention-based, convolutional, and SSM-based models for multi-domain image classification (Doctoral dissertation, BRAC University).

- Li, W., Zhu, M., Xu, Y., Huang, M., Wang, Z., Chen, J., ... & Sun, X. (2025). SIGEL: a context-aware genomic representation learning framework for spatial genomics analysis. Genome Biology, 26(1), 287. [CrossRef]

- Zha, D., Mahmood, N., Kellar, R. S., Gluck, J. M., & King, M. W. (2025). Fabrication of PCL Blended Highly Aligned Nanofiber Yarn from Dual-Nozzle Electrospinning System and Evaluation of the Influence on Introducing Collagen and Tropoelastin. ACS Biomaterials Science & Engineering.

- Kasaraneni, C. K., Guttikonda, K., & Madamala, R. (2025). Multi-modality Medical (CT, MRI, Ultrasound Etc.) Image Fusion Using Machine Learning/Deep Learning. In Machine Learning and Deep Learning Modeling and Algorithms with Applications in Medical and Health Care (pp. 319-345). Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland.

- Wang, Y., Wen, Y., Wu, X., Wang, L., & Cai, H. (2025). Assessing the Role of Adaptive Digital Platforms in Personalized Nutrition and Chronic Disease Management. [CrossRef]

- Samaga, D., Hornung, R., Braselmann, H., Hess, J., Zitzelsberger, H., Belka, C., ... & Unger, K. (2020). Single-center versus multi-center data sets for molecular prognostic modeling: a simulation study. Radiation Oncology, 15(1), 109. [CrossRef]

- Wen, Y., Wu, X., Wang, L., Cai, H., & Wang, Y. (2025). Application of Nanocarrier-Based Targeted Drug Delivery in the Treatment of Liver Fibrosis and Vascular Diseases. Journal of Medicine and Life Sciences, 1(2), 63-69. [CrossRef]

- Abbasi, H., Orouskhani, M., Asgari, S., & Zadeh, S. S. (2023). Automatic brain ischemic stroke segmentation with deep learning: A review. Neuroscience Informatics, 3(4), 100145. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).