Submitted:

27 December 2025

Posted:

29 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Endothelial Cells from iPSCs: Differentiation and Characterization

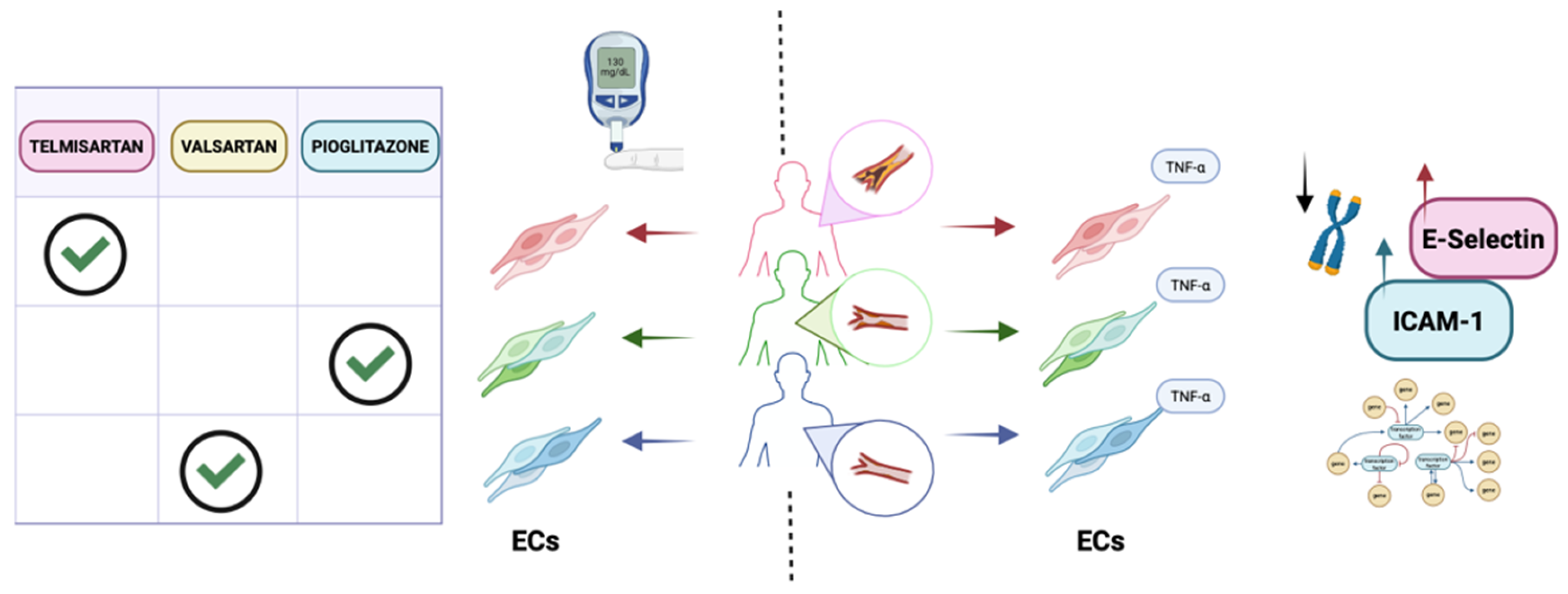

3. Patient-Specific iPSC-ECs as Predictive and Personalized Models for Cardiovascular Applications

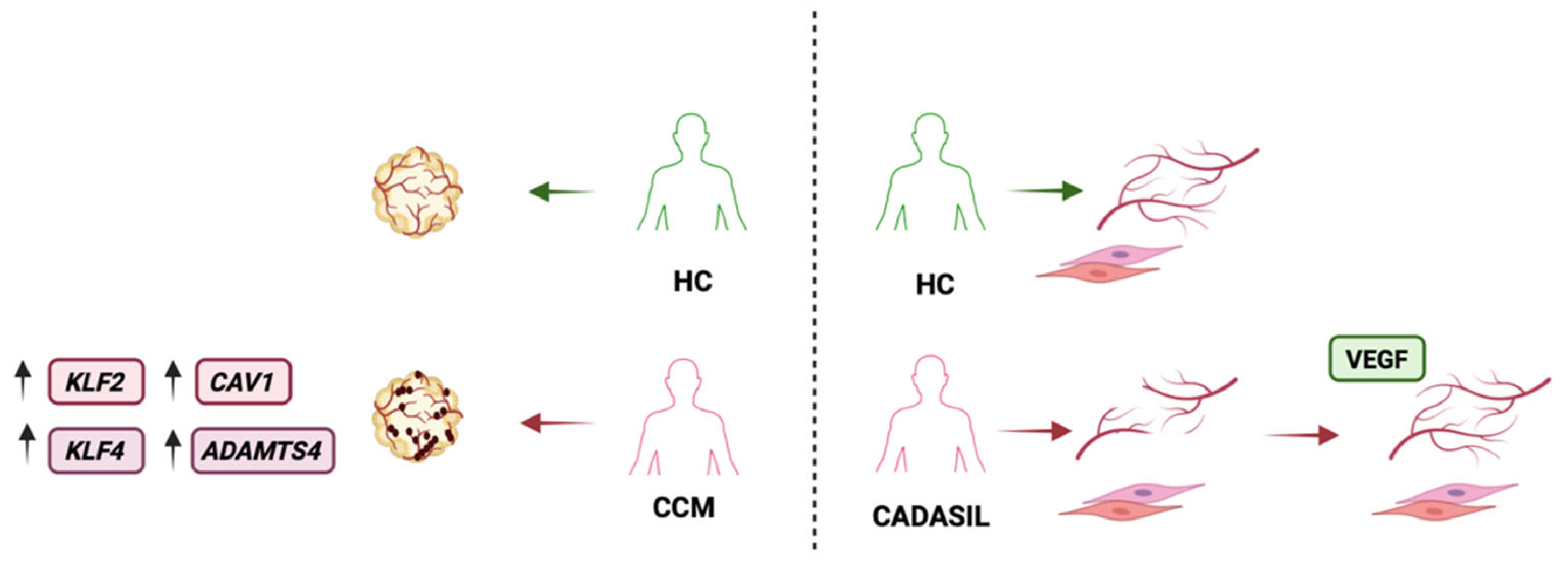

4. Patient-Specific iPSC-ECs as Predictive and Personalized Models for Cerebrovascular Studies

6. Limitations

7. Future Applications

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| aHUS | Atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome |

| BMP | Bone morphogenetic protein |

| CADASIL | Cerebral Autosomal Dominant Arteriopathy with Subcortical Infarcts and Leukoencephalopathy |

| ECs | Endothelial cells |

| eNOS | Endothelial nitric oxide synthase |

| FH | Familial hypercholesterolemia |

| H9-ECs | H9 human embryonic stem cells - derived endothelial cells |

| hiPSC-ECs | Human induced pluripotent stem cell – derived endothelial cells |

| MMD | Moyamoya disease |

| MMP | Matrix metalloproteinases |

| PRC | Polycomb Repressive Complex |

| TEnCs | Tumor-associated endothelial cells |

| VSMCs | Vascular smooth muscle cells |

| vWF | Von Willebrand factor |

References

- Trimm, E.; Red-Horse, K. Vascular Endothelial Cell Development and Diversity. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2023, 20, 197–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrova, T. V.; Koh, G.Y. Biological Functions of Lymphatic Vessels. Science 2020, 369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krüger-Genge, A.; Blocki, A.; Franke, R.-P.; Jung, F. Vascular Endothelial Cell Biology: An Update. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 4411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- dela Paz, N.G.; D’Amore, P.A. Arterial versus Venous Endothelial Cells. Cell. Tissue Res. 2009, 335, 5–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.; Chen, Q.; Chen, X.; Han, F.; Chen, Z.; Wang, Y. The Blood–Brain Barrier: Structure, Regulation and Drug Delivery. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2023, 8, 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Favero, G.; Paganelli, C.; Buffoli, B.; Rodella, L.F.; Rezzani, R. Endothelium and Its Alterations in Cardiovascular Diseases: Life Style Intervention. Biomed. Res. Int. 2014, 2014, 801896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gimbrone, M.A.; García-Cardeña, G. Endothelial Cell Dysfunction and the Pathobiology of Atherosclerosis. Circ. Res. 2016, 118, 620–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, D. V.; Shaw, L.C.; Grant, M.B. Inflammation in the Pathogenesis of Microvascular Complications in Diabetes. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne) 2012, 3, 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurakula, K.; Smolders, V.F.E.D.; Tura-Ceide, O.; Jukema, J.W.; Quax, P.H.A.; Goumans, M.-J. Endothelial Dysfunction in Pulmonary Hypertension: Cause or Consequence? Biomedicines 2021, 9, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Zhao, B.; Yu, Y.; Gao, W.; Liu, W.; Chen, L.; Xia, Z.; Cao, Q. Vascular Aging in Ischemic Stroke. J. Am. Heart. Assoc. 2024, 13, e033341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mekala, A.; Qiu, H. Interplay Between Vascular Dysfunction and Neurodegenerative Pathology: New Insights into Molecular Mechanisms and Management. Biomolecules 2025, 15, 712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moncada, S.; Higgs, E.A. The Discovery of Nitric Oxide and Its Role in Vascular Biology. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2006, 147, 193–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, H.; Harrison, D.G. Endothelial Dysfunction in Cardiovascular Diseases: The Role of Oxidant Stress. Circ. Res. 2000, 87, 840–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chistiakov, D.A.; Orekhov, A.N.; Bobryshev, Y. V. Endothelial Barrier and Its Abnormalities in Cardiovascular Disease. Front. Physiol. 2015, 6, 365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paik, D.T.; Chandy, M.; Wu, J.C. Patient and Disease–Specific Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells for Discovery of Personalized Cardiovascular Drugs and Therapeutics. Pharmacol. Rev. 2020, 72, 320–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nashun, B.; Hill, P.W.; Hajkova, P. Reprogramming of Cell Fate: Epigenetic Memory and the Erasure of Memories Past. EMBO J. 2015, 34, 1296–1308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sriram, G.; Tan, J.Y.; Islam, I.; Rufaihah, A.J.; Cao, T. Efficient Differentiation of Human Embryonic Stem Cells to Arterial and Venous Endothelial Cells under Feeder- and Serum-Free Conditions. Stem. Cell. Res. Ther. 2015, 6, 261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, J.; Hirschi, K.K. Endothelial Cell Development and Its Application to Regenerative Medicine. Circ. Res. 2019, 125, 489–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Schwartz, M.A.; Simons, M. Developmental Perspectives on Arterial Fate Specification. Front. Cell. Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 691335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aranguren, X.L.; Beerens, M.; Coppiello, G.; Wiese, C.; Vandersmissen, I.; Lo Nigro, A.; Verfaillie, C.M.; Gessler, M.; Luttun, A. COUP-TFII Orchestrates Venous and Lymphatic Endothelial Identity by Homo- or Hetero-Dimerisation with PROX1. J. Cell. Sci. 2013, 126, 1164–1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arora, S.; Yim, E.K.F.; Toh, Y.-C. Environmental Specification of Pluripotent Stem Cell Derived Endothelial Cells Toward Arterial and Venous Subtypes. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2019, 7, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selim, M.S.; Matani, B.R.; Henry-Ojo, H.O.; Narayanan, S.P.; Somanath, P.R. Claudin 5 Across the Vascular Landscape: From Blood–Tissue Barrier Regulation to Disease Mechanisms. Cells 2025, 14, 1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goncharov, N. V.; Popova, P.I.; Avdonin, P.P.; Kudryavtsev, I. V.; Serebryakova, M.K.; Korf, E.A.; Avdonin, P. V. Markers of Endothelial Cells in Normal and Pathological Conditions. Biochem. (Mosc) Suppl. Ser. A. Membr. Cell. Biol. 2020, 14, 167–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Boer, S.; Laan, S.; Dirven, R.; Eikenboom, J. Approaches to Induce the Maturation Process of Human Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell Derived-Endothelial Cells to Generate a Robust Model. PLoS One 2024, 19, e0297465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belt, H.; Koponen, J.K.; Kekarainen, T.; Puttonen, K.A.; Mäkinen, P.I.; Niskanen, H.; Oja, J.; Wirth, G.; Koistinaho, J.; Kaikkonen, M.U.; et al. Temporal Dynamics of Gene Expression During Endothelial Cell Differentiation From Human IPS Cells: A Comparison Study of Signalling Factors and Small Molecules. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2018, 5, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanner, F.; Sohl, M.; Farnebo, F. Functional Arterial and Venous Fate Is Determined by Graded VEGF Signaling and Notch Status During Embryonic Stem Cell Differentiation. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2007, 27, 487–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carcamo-Orive, I.; Hoffman, G.E.; Cundiff, P.; Beckmann, N.D.; D’Souza, S.L.; Knowles, J.W.; Patel, A.; Hendry, C.; Papatsenko, D.; Abbasi, F.; et al. Analysis of Transcriptional Variability in a Large Human IPSC Library Reveals Genetic and Non-Genetic Determinants of Heterogeneity. Cell Stem. Cell 2017, 20, 518–532.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.; Doi, A.; Wen, B.; Ng, K.; Zhao, R.; Cahan, P.; Kim, J.; Aryee, M.J.; Ji, H.; Ehrlich, L.I.R.; et al. Epigenetic Memory in Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells. Nature 2010, 467, 285–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Torres, J.A.; Virumbrales-Muñoz, M.; Sung, K.E.; Lee, M.H.; Abel, E.J.; Beebe, D.J. Patient-Specific Organotypic Blood Vessels as an in Vitro Model for Anti-Angiogenic Drug Response Testing in Renal Cell Carcinoma. EBioMedicine 2019, 42, 408–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zakharova, I.S.; Shevchenko, A.I.; Arssan, M.A.; Sleptcov, A.A.; Nazarenko, M.S.; Zarubin, A.A.; Zheltysheva, N. V.; Shevchenko, V.A.; Tmoyan, N.A.; Saaya, S.B.; et al. IPSC-Derived Endothelial Cells Reveal LDLR Dysfunction and Dysregulated Gene Expression Profiles in Familial Hypercholesterolemia. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, M.S.; Goldstein, J.L. Familial Hypercholesterolemia: Defective Binding of Lipoproteins to Cultured Fibroblasts Associated with Impaired Regulation of 3-Hydroxy-3-Methylglutaryl Coenzyme a Reductase Activity. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 1974, 71, 788–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, P. Brown and Goldstein: The Cholesterol Chronicles. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2013, 110, 14829–14832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chrzanowska-Wodnicka, M. Rap1 in Endothelial Biology. Curr. Opin. Hematol. 2017, 24, 248–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, B.; Kosuru, R.; Lakshmikanthan, S.; Sorci-Thomas, M.G.; Zhang, D.X.; Sparapani, R.; Vasquez-Vivar, J.; Chrzanowska, M. Endothelial Rap1 (Ras-Association Proximate 1) Restricts Inflammatory Signaling to Protect From the Progression of Atherosclerosis. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2021, 41, 638–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, D.; Tan, Y.; Liu, X.; Tang, L.; Wang, H.; Shen, J.; Wang, W.; Zhuang, L.; Tao, J.; Su, J.; et al. Patient-Specific IPSC-Derived Endothelial Cells Reveal Aberrant P38 MAPK Signaling in Atypical Hemolytic Uremic Syndrome. Stem Cell Reports 2021, 16, 2305–2319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavanagh, D.; Goodship, T.H.J. Atypical Hemolytic Uremic Syndrome, Genetic Basis, and Clinical Manifestations. Hematology 2011, 2011, 15–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chu, L.-Y.; Wang, Y.-F.; Cheng, H.-H.; Kuo, C.-C.; Wu, K.K. Endothelium-Derived 5-Methoxytryptophan Protects Endothelial Barrier Function by Blocking P38 MAPK Activation. PLoS One 2016, 11, e0152166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dejana, E.; Orsenigo, F.; Lampugnani, M.G. The Role of Adherens Junctions and VE-Cadherin in the Control of Vascular Permeability. J. Cell Sci. 2008, 121, 2115–2122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, S.; Reece, E.A.; Shen, W.-B.; Yang, P. Restoring BMP4 Expression in Vascular Endothelial Progenitors Ameliorates Maternal Diabetes-Induced Apoptosis and Neural Tube Defects. Cell Death Dis. 2020, 11, 859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mace, K.A.; Hansen, S.L.; Myers, C.; Young, D.M.; Boudreau, N. HOXA3 Induces Cell Migration in Endothelial and Epithelial Cells Promoting Angiogenesis and Wound Repair. J. Cell Sci. 2005, 118, 2567–2577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sauteur, L.; Krudewig, A.; Herwig, L.; Ehrenfeuchter, N.; Lenard, A.; Affolter, M.; Belting, H.-G. Cdh5/VE-Cadherin Promotes Endothelial Cell Interface Elongation via Cortical Actin Polymerization during Angiogenic Sprouting. Cell Rep. 2014, 9, 504–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorashi, R.; Rivera-Bolanos, N.; Dang, C.; Chai, C.; Kovacs, B.; Alharbi, S.; Ahmed, S.S.; Goyal, Y.; Ameer, G.; Jiang, B. Modeling Diabetic Endothelial Dysfunction with Patient-specific Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells. Bioeng Transl. Med. 2023, 8, e10592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, M.; Mordwinkin, N.M.; Kooreman, N.G.; Lee, J.; Wu, H.; Hu, S.; Churko, J.M.; Diecke, S.; Burridge, P.W.; He, C.; et al. Pravastatin Reverses Obesity-Induced Dysfunction of Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell-Derived Endothelial Cells via a Nitric Oxide-Dependent Mechanism. Eur. Heart J. 2015, 36, 806–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, M.; Donato, M.; Guo, M.; Wary, N.; Miao, Y.; Mao, S.; Saito, T.; Otsuki, S.; Wang, L.; Harper, R.L.; et al. IPSC–Endothelial Cell Phenotypic Drug Screening and in Silico Analyses Identify Tyrphostin-AG1296 for Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension. Sci. Transl. Med. 2021, 13, eaba6480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandy, M.; Obal, D.; Wu, J.C. Elucidating Effects of Environmental Exposure Using Human-induced Pluripotent Stem Cell Disease Modeling. EMBO Mol. Med. 2022, 14, e13260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sgromo, C.; Cucci, A.; Venturin, G.; Follenzi, A.; Olgasi, C. Bridging the Gap: Endothelial Dysfunction and the Role of IPSC-Derived Endothelial Cells in Disease Modeling. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 13275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, L.; Su, J.; Liang, P. Modeling Cadmium-Induced Endothelial Toxicity Using Human Pluripotent Stem Cell-Derived Endothelial Cells. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 14811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tellez-Plaza, M.; Navas-Acien, A.; Menke, A.; Crainiceanu, C.M.; Pastor-Barriuso, R.; Guallar, E. Cadmium Exposure and All-Cause and Cardiovascular Mortality in the U.S. General Population. Environ. Health Perspect. 2012, 120, 1017–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Straessler, E.T.; Kraenkel, N.; Landmesser, U. RNA-Sequencing Reveals Significant Differences in the Inflammatory Response of IPSC-Derived Endothelial Cells from ACS Patients and Healthy Controls. Eur. Heart J. 2022, 43, ehac544.3058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Straessler, E.T.; Kiamehr, M.; Aalto-Setala, K.; Kraenkel, N.K.; Landmesser, U.L. IPSC-Derived Endothelial Cells Reflect Accelerated Senescence and Increased Inflammatory Response in a CVD-Risk Stratified Manner. Eur. Heart J. 2020, 41, ehaa946.3747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chabriat, H.; Joutel, A.; Dichgans, M.; Tournier-Lasserve, E.; Bousser, M.-G. CADASIL. Lancet Neurol. 2009, 8, 643–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, W.; Zhao, X.; Qi, X.; Kimber, S.J.; Hooper, N.M.; Wang, T. Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell Model Revealed Impaired Neurovascular Interaction in Genetic Small Vessel Disease Cerebral Autosomal Dominant Arteriopathy with Subcortical Infarcts and Leukoencephalopathy. Front. Cell Neurosci. 2023, 17, 1195470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ihara, M.; Yamamoto, Y.; Hattori, Y.; Liu, W.; Kobayashi, H.; Ishiyama, H.; Yoshimoto, T.; Miyawaki, S.; Clausen, T.; Bang, O.Y.; et al. Moyamoya Disease: Diagnosis and Interventions. Lancet Neurol. 2022, 21, 747–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hitomi, T.; Habu, T.; Kobayashi, H.; Okuda, H.; Harada, K.H.; Osafune, K.; Taura, D.; Sone, M.; Asaka, I.; Ameku, T.; et al. Downregulation of Securin by the Variant RNF213 R4810K (Rs112735431, G>A) Reduces Angiogenic Activity of Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell-Derived Vascular Endothelial Cells from Moyamoya Patients. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2013, 438, 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamauchi, S.; Shichinohe, H.; Uchino, H.; Yamaguchi, S.; Nakayama, N.; Kazumata, K.; Osanai, T.; Abumiya, T.; Houkin, K.; Era, T. Cellular Functions and Gene and Protein Expression Profiles in Endothelial Cells Derived from Moyamoya Disease-Specific IPS Cells. PLoS One 2016, 11, e0163561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stupack, D.G.; Cheresh, D.A. Integrins and Angiogenesis. Curr. Top. Dev. Biol. 2004, 64, 207–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokairin, K.; Hamauchi, S.; Ito, M.; Kazumata, K.; Sugiyama, T.; Nakayama, N.; Kawabori, M.; Osanai, T.; Houkin, K. Vascular Smooth Muscle Cell Derived from IPS Cell of Moyamoya Disease - Comparative Characterization with Endothelial Cell Transcriptome. J. Stroke Cerebrovasc. Dis. 2020, 29, 105305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arce, M.; Erzar, I.; Yang, F.; Senthilkumar, N.; Onyeogaziri, F.C.; Ronchi, D.; Ahlstrand, F.C.; Noll, N.; Lugano, R.; Richards, M.; et al. KRIT1 Heterozygous Mutations Are Sufficient to Induce a Pathological Phenotype in Patient-Derived IPSC Models of Cerebral Cavernous Malformation. Cell. Rep. 2025, 44, 115576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Queisser, A.; Seront, E.; Boon, L.M.; Vikkula, M. Genetic Basis and Therapies for Vascular Anomalies. Circ, Res 2021, 129, 155–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cerneckis, J.; Cai, H.; Shi, Y. Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells (IPSCs): Molecular Mechanisms of Induction and Applications. Signal Transduct. Target Ther. 2024, 9, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, G.; Gao, J.; Ding, P.; Gao, Y. The Role of Endothelial Cell–Pericyte Interactions in Vascularization and Diseases. J. Adv. Res. 2025, 67, 269–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Méndez-Barbero, N.; Gutiérrez-Muñoz, C.; Blanco-Colio, L. Cellular Crosstalk between Endothelial and Smooth Muscle Cells in Vascular Wall Remodeling. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 7284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pober, J.S.; Sessa, W.C. Evolving Functions of Endothelial Cells in Inflammation. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2007, 7, 803–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaeffer, S.; Iadecola, C. Revisiting the Neurovascular Unit. Nat. Neurosci. 2021, 24, 1198–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segarra, M.; Aburto, M.R.; Hefendehl, J.; Acker-Palmer, A. Neurovascular Interactions in the Nervous System. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2019, 35, 615–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vozzi, F.; Campolo, J.; Cozzi, L.; Politano, G.; Di Carlo, S.; Rial, M.; Domenici, C.; Parodi, O. Computing of Low Shear Stress-Driven Endothelial Gene Network Involved in Early Stages of Atherosclerotic Process. Biomed. Res. Int. 2018, 2018, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceccherini, E.; Persiani, E.; Cabiati, M.; Guiducci, L.; Del Ry, S.; Gisone, I.; Falleni, A.; Cecchettini, A.; Vozzi, F. A Dynamic Cellular Model as an Emerging Platform to Reproduce the Complexity of Human Vascular Calcification In Vitro. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 7427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gisone, I.; Boffito, M.; Persiani, E.; Pappalardo, R.; Ceccherini, E.; Alliaud, A.; Cabiati, M.; Laurano, R.; Guiducci, L.; Caselli, C.; et al. Integration of Co-Culture Conditions and 3D Gelatin Methacryloyl Hydrogels to Improve Human-Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells-Derived Cardiomyocytes Maturation. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2025, 13, 1576824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontanelli, L.; Nisini, N.; Pirola, S.; Recchia, F.A. Neuromuscular and Cardiac Organoids and Assembloids: Advanced Platforms for Drug Testing. Pharmacol. Ther. 2025, 272, 108876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).