Introduction

Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is one of the most common neurodevelopmental conditions on the planet. About 5–7 % of kids carry the diagnosis, and roughly two-thirds of them still meet the criteria as adults; in the general adult population the rate sits around 2.5–4 % [

1,

2]. The hallmark problems—chronic inattention, hyperactivity and impulsivity—can snowball into poor grades, shaky relationships and a higher chance of developing other psychiatric illnesses [

3]. Stimulant drugs are still the go-to treatment and often work well, but plenty of patients either don't get full relief or can't tolerate the side-effects, so clinicians are eager for new options [

4].

Family and twin studies tell us ADHD is largely genetic, with heritability hovering around 70–80 % [

5]. Big genome-wide association studies paint the same picture. The newest meta-analysis, which included more than 38 000 cases, flagged 27 risk loci and showed that thousands of common variants—each nudging risk only a little—add up to make a difference [

6]. Those common SNPs explain only about a quarter of the total genetic risk, underscoring how tangled the mix of genes and environment really is [

6].

For many years, ADHD research focused on dopamine and norepinephrine. Now, however, the glutamate system is getting more and more attention [

7]. In animal studies, knocking the NMDA receptors in the prefrontal cortex off balance derails those plasticity pathways and guts executive functions [

8,

9,

10]. Early clinical work hints that tweaking this same glutamatergic gear train—with drugs like the NMDA antagonist memantine or AMPA-receptor modulators—can ease symptoms in people who don't get enough help from standard stimulants [

11,

12].

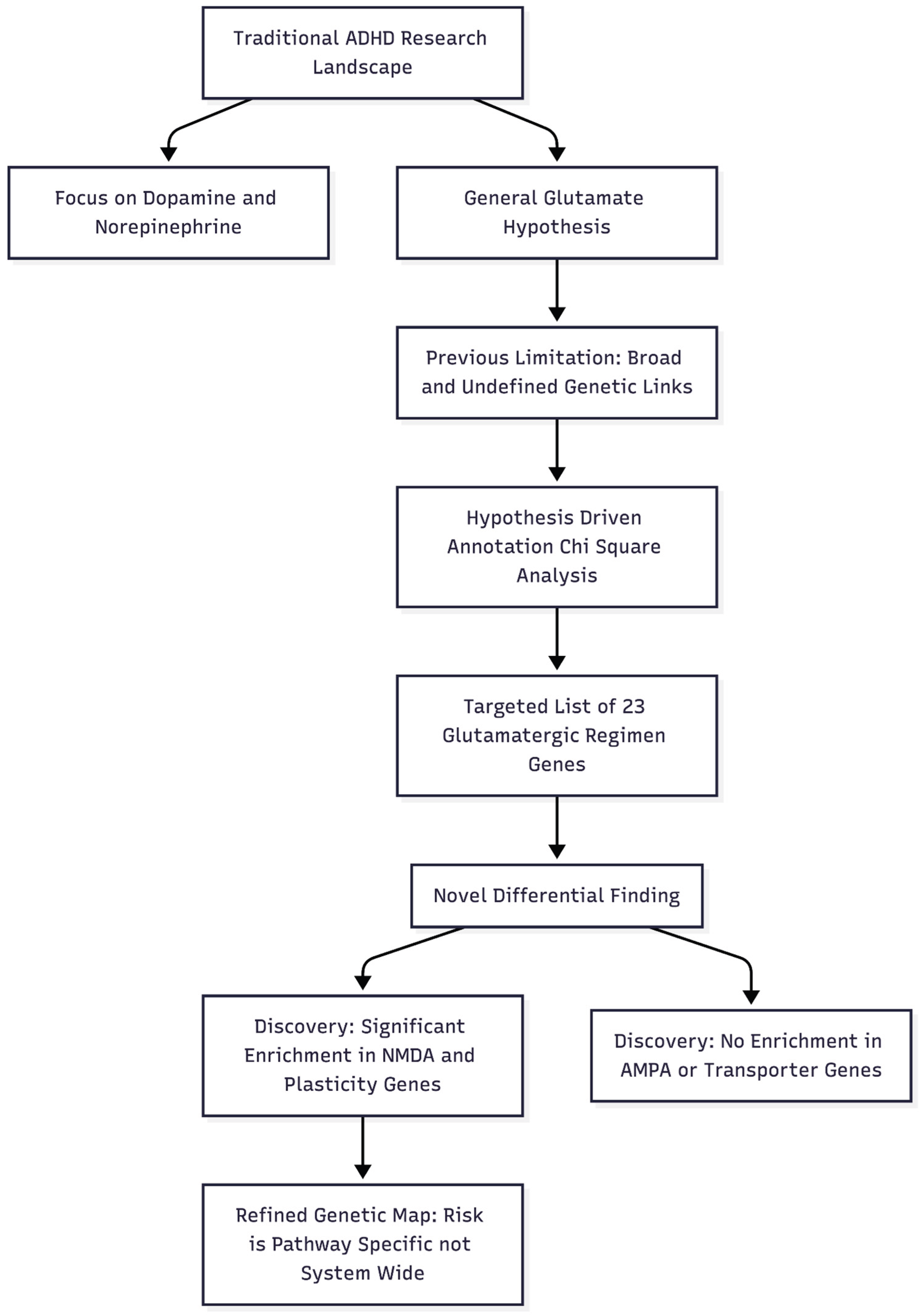

Still, we don't have a clear genetic map of glutamate's role in ADHD. Broad heritability studies show ADHD risk variants tend to pile up in genes expressed across neurons, but detailed pathway analyses are rare [

6]. That gap is what we tackle here. We built a hand-picked list of "glutamatergic regimen targets": genes for NMDA and AMPA/kainate receptor subunits, plasticity-related signaling players like brain-derived neurotrophic factor and mTOR, plus the transporters and enzymes that shuttle or break down glutamate. These candidates could influence both who gets ADHD and who might respond to upcoming glutamate-focused treatments.

Using the summary statistics from the 2023 ADHD GWAS mega-study [

6], we ran an annotation χ² test to ask a simple question: do SNPs sitting near those glutamatergic genes carry more ADHD association signal than random chance would predict? The approach is narrower than standard heritability partitioning but gives a sharper, hypothesis-driven look at which slices of the glutamate pathway matter most. Pinpointing those slices could guide precision-medicine efforts and speed up the hunt for targeted ADHD therapies.

Methods

We set out to ask whether common variants that lie in or near genes targeted by glutamatergic drugs carry more attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) signal than variants elsewhere in the genome. To that end we used an annotation χ² approach, which simply compares the average association statistic (Z²) for single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) inside a predefined gene list with the average for all remaining SNPs. Because it treats each SNP independently, the method does not need pre-computed linkage disequilibrium scores and can be run quickly on very large files.

Publicly available summary statistics from the most recent European-ancestry ADHD meta-analysis (38,691 cases, 186,843 controls) formed the analytic base [

6]. After standardising column names we derived Z-scores from p values (two-tailed) and signed them according to the reported odds ratio. Per-SNP effective sample size was calculated as 4 / (1/N_cases + 1/N_controls), yielding an average effective N of ~128,000. Variants with INFO < 0.90 or minor-allele frequency < 1 % were removed, leaving 6,699,009 SNPs (≈ 99 % of the original file). The mean χ² for this QC-filtered set was 1.405 (λ_GC = 1.325).

Twenty-three candidate genes were chosen because they participate in glutamatergic neurotransmission or in downstream plasticity cascades that can be reached by drugs such as ketamine or dextromethorphan/quinidine. They were grouped into five functional classes—NMDA-receptor subunits (GRIN1, GRIN2A-D), AMPA/kainate subunits (GRIA1-4, GRIK2), metabolic modifiers (CYP2D6, SIGMAR1, CYP3A4), plasticity signalling components (BDNF, NTRK2, MTOR, AKT1, PTEN, CREB1, ARC) and glutamate transporters (SLC1A1, SLC1A2, DLGAP3). Genomic coordinates (GRCh37/hg19) were padded by 10 kb on either side to capture nearby regulatory elements and converted into BED files. Overlap with the 1000 Genomes European reference panel (22.7 M variants) produced binary annotations (1 = inside the extended region, 0 = outside).

For every annotation we merged the tag with the ADHD summary statistics, computed χ² = Z² for each SNP and then averaged χ² separately inside and outside the annotation. Enrichment was expressed as the ratio of these two means. We assessed significance three ways: Welch's t test for unequal variances, a one-sided Mann-Whitney U test, and a 200-block delete-one jack-knife to derive a standard error for the ratio itself. SNP-based heritability captured by each set was approximated as (mean χ² − 1) × number of SNPs / effective N. All analyses were run for each functional class and for the combined 23-gene list.

Results

After merging the annotations with the cleaned GWAS file, 6,648,566 SNPs remained in every comparison. Annotated variants were rare, accounting for 0.02 – 0.15 % of the total, depending on the gene class.

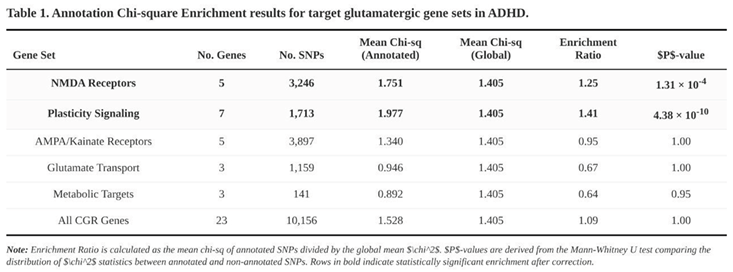

Clear enrichment emerged in two of the five classes (Table 1). SNPs within the five NMDA-receptor genes showed a 1.25-fold higher mean χ² than the background (annotated = 1.751, unannotated = 1.405; Mann-Whitney p = 1.3 × 10⁻⁴). The seven plasticity-signalling genes performed even better, with a 1.41-fold inflation (1.977 vs. 1.405; p = 4.4 × 10⁻¹⁰). When all 23 genes were collapsed into a single list the enrichment was modest (1.09) but still significant by parametric testing (Welch p = 4.2 × 10⁻⁸); the non-parametric test was neutral.

No signal surfaced for AMPA/kainate subunits (enrichment 0.95), for glutamate transporters (0.67) or for the three metabolic genes (0.64). In fact, the latter two categories trended toward depletion, suggesting that ADHD risk is not evenly distributed across the broader glutamatergic pathway.

Together these findings point to NMDA-receptor components and their immediate plasticity partners as disproportionate carriers of ADHD common-variant risk, highlighting them as plausible biological substrates for the disorder.

Discussion

The present chi-square annotation analysis suggests that genetic variation within a narrow slice of the glutamatergic system—chiefly NMDA-receptor genes and their plasticity-related partners—accounts for more ADHD heritability than would be expected by chance. Summary statistics drawn from a recent GWAS meta-analysis [

6] revealed a 1.25-fold enrichment for loci that encode NMDA receptor subunits and a 1.41-fold enrichment for genes tied to downstream plasticity cascades such as BDNF, NTRK2, and mTOR. When all 23 genes chosen a priori as "glutamatergic-regimen targets" were considered together, the enrichment signal remained but was driven almost entirely by the NMDA and plasticity subsets. Notably, genes related to AMPA/kainate receptors, glutamate transporters, or glutamate metabolism did not show enrichment, implying that glutamatergic risk is confined to specific pathways rather than spread uniformly across the system.

The genetic pattern dovetails with functional data. PFC networks depend on a tight interplay between NMDA- and AMPA-mediated currents to maintain sustained firing and suppress impulsive responses [

8,

9]. Disturbing this balance—particularly by weakening NMDA-driven calcium entry—undercuts the plasticity needed for working memory and executive control [

13,

14]. Variants that blunt NMDA receptor efficiency have been reported in people with ADHD [

10], and SHR rats—an accepted ADHD model—show reduced NMDA-stimulated calcium uptake alongside exaggerated AMPA-evoked catecholamine release [

15,

16]. The current enrichment results echo those mechanistic links.

By contrast, the non-significant signal for AMPA/kainate genes may reflect compensatory circuitry rather than a lack of involvement. In some models, excessive AMPA drive appears secondary to diminished NMDA tone, and dopaminergic state can bias AMPA trafficking in opposite directions via D1 and D2 pathways [

17,

18]. Thus, AMPA-related risk alleles might not cluster consistently in population data even when AMPA function is altered in experimental settings.

These results make the case for going beyond pure catecholaminergic strategies stronger from a therapeutic point of view. Classic stimulants such as methylphenidate don't just ramp up dopamine; they also put AMPA receptors back where they belong, rescuing long-term potentiation and behavior in the process [

9,

19]. Compounds that hit the glutamate system more directly are starting to shine as well. Memantine may reduce ADHD symptoms in kids and adults without causing major side effects [

11,

12,

20]. And although the first trials of AMPA positive allosteric modulators (ampakines) have been a mixed bag, the overall signal is promising [

21,

22].

A more recent proposal is to pair a stimulant-induced glutamate pulse with a gentle AMPA "pull." Small trials suggest that adding piracetam to methylphenidate can lift residual executive and motivational problems [

23,

24]. For amphetamine formulations, combining low-dose dextromethorphan as an NMDA brake with piracetam may limit excitotoxic risk while preserving plasticity gains [

25]. Such regimens echo the AMPA-dominant state thought to underlie ketamine's rapid antidepressant effects.

Several caveats need emphasis. First, our annotations were targeted and did not capture all glutamatergic genes or distant regulatory elements, so some risk may have been missed. Second, the chi-square framework is a coarse approximation of partitioned heritability; methods such as LD-score regression would offer finer resolution but were beyond the scope of this exercise. Third, the GWAS meta-analysis is still heavily weighted toward European ancestry, limiting immediate generalization. Finally, sample overlap between discovery and replication sets could inflate enrichment estimates.

Even with these problems, the data point to a model of ADHD as a disorder of dopamine and glutamate not talking to each other at the right time in prefrontal circuits [

7]. Genes that control the assembly of NMDA receptors and plasticity signaling are important factors that increase risk. This genetic signal fits with what we know from animals and people, and it gives us a solid reason to test glutamate-modulating treatments, to see if they can help with symptoms that don't go away after standard stimulant therapy.

Figure 1.

Novelty and Impactfulness of the Study. This diagram illustrates how the study moves away from broad, generalized theories to a specific, hypothesis-driven genetic analysis that differentiates between sub-components of the glutamate system.

Figure 1.

Novelty and Impactfulness of the Study. This diagram illustrates how the study moves away from broad, generalized theories to a specific, hypothesis-driven genetic analysis that differentiates between sub-components of the glutamate system.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethics Declaration

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

None declared.

References

- Polanczyk GV, Willcutt EG, Salum GA, et al. ADHD prevalence estimates across three decades: An updated systematic review and meta-regression analysis. International Journal of Epidemiology. 2014;43(2):434-442. [CrossRef]

- Faraone SV, Biederman J, Mick E. The age-dependent decline of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: A meta-analysis of follow-up studies. Psychological Medicine. 2021;36(2):159-165. [CrossRef]

- Erskine HE, Norman RE, Ferrari AJ, et al. Long-term outcomes of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and conduct disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2016;55(10):841-850. [CrossRef]

- Cortese S, Adamo N, Del Giovane C, et al. Comparative efficacy and tolerability of medications for attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder in children, adolescents, and adults: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. The Lancet Psychiatry. 2018;5(9):727-738. [CrossRef]

- Faraone SV, Larsson H. Genetics of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Molecular Psychiatry. 2019;24(4):562-575. [CrossRef]

- Demontis D, Walters GB, Athanasiadis G, et al. Genome-wide analyses of ADHD identify 27 risk loci, refine the genetic architecture and implicate several cognitive domains. Nature Genetics. 2023;55(2):198-208. [CrossRef]

- MacDonald HJ, Kleppe R, Szigetvari PD, et al. The dopamine hypothesis for ADHD: An evaluation of evidence accumulated from human studies and animal models. Frontiers in Psychiatry. 2024;15:1492126. [CrossRef]

- Russell VA, Sagvolden T, Johansen EB. Animal models of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Behavioral and Brain Functions. 2005;1:9. [CrossRef]

- Cheng J, Liu A, Shi MY, et al. Disrupted glutamatergic transmission in prefrontal cortex contributes to behavioral abnormality in an animal model of ADHD. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2017;42(10):2096-2104. [CrossRef]

- Kuś J, Saramowicz K, Czerniawska M, et al. Molecular Mechanisms Underlying NMDARs Dysfunction and Their Role in ADHD Pathogenesis. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2023;24(16):12983. [CrossRef]

- Surman CB, Hammerness PG, Petty C, et al. A pilot open label prospective study of memantine monotherapy in adults with ADHD. The World Journal of Biological Psychiatry. 2013;14(4):291-298. [CrossRef]

- Choi WS, Wang SM, Woo YS, et al. Therapeutic efficacy and safety of memantine for children and adults with ADHD with a focus on glutamate-dopamine regulation: A systematic review. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2024;86(1):24r15507. [CrossRef]

- Durstewitz D, Seamans JK, Sejnowski TJ. Dopamine-mediated stabilization of delay-period activity in a network model of prefrontal cortex. Journal of Neurophysiology. 2000;83(3):1733-1750. [CrossRef]

- Seamans JK, Yang CR. The principal features and mechanisms of dopamine modulation in the prefrontal cortex. Progress in Neurobiology. 2004;74(1):1-58. [CrossRef]

- Lehohla M, Kellaway L, Russell VA. NMDA receptor function in the prefrontal cortex of a rat model for attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Metabolic Brain Disease. 2004;19(1-2):35-42. [CrossRef]

- Russell VA. Increased AMPA receptor function in slices containing the prefrontal cortex of spontaneously hypertensive rats. Metabolic Brain Disease. 2001;16(3-4):143-149. [CrossRef]

- Sun X, Zhao Y, Wolf ME. Dopamine receptor stimulation modulates AMPA receptor synaptic insertion in prefrontal cortex neurons. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2005;25(32):7342-7351. [CrossRef]

- Tseng KY, O'Donnell P. Dopamine–glutamate interactions controlling prefrontal cortical pyramidal cell excitability involve multiple signaling mechanisms. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2004;24(22):5131-5139. [CrossRef]

- Alkam T, Mamiya T, Yamada K, et al. Methylphenidate restores behavioral and neuroplasticity impairments in the prenatal nicotine exposure mouse model of ADHD: Evidence for involvement of AMPA receptor subunit composition and synaptic spine morphology in the hippocampus. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2022;23(13):7099. [CrossRef]

- Mohammadzadeh S, Ahangari TK, Yousefi F. The effect of memantine in adult patients with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Human Psychopharmacology. 2019;34(1):e2687. [CrossRef]

- Kadriu B, Musazzi L, Johnston JN, et al. Positive AMPA receptor modulation in the treatment of neuropsychiatric disorders: A long and winding road. Drug Discovery Today. 2021;26(12):2816-2838. [CrossRef]

- Radin DP, Cerne R, Smith JL, et al. Low-impact ampakine CX717 exhibits promising therapeutic profile in adults with ADHD - A phase 2A clinical trial. European Journal of Pharmacology. 2025;1005:178047. [CrossRef]

- Alavi K, Shirazi E, Akbari M, et al. Effects of piracetam as an adjuvant therapy on attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Iranian Journal of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences. 2021;15(2):e59421. [CrossRef]

- Cheung N. Methylphenidate plus piracetam: A two-drug, AMPA-centric alternative replicating ketamine's neuroplastic signature. Preprints. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Cheung N. Proposing A Novel Glutamatergic Regimen as a Missing Link in ADHD Treatment. Preprints. 2025. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |