Submitted:

26 December 2025

Posted:

29 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Background: Migraine, including vestibular migraine (VM), is a complex neurological disorder with diverse symptoms. VM is primarily characterized by vertigo attacks, while episodic migraine (EM) is more associated with headache features. This study aims to identify the distinguishing characteristics and comorbidities of VM and EM. Methods: A retrospective analysis was conducted using databases from Mersin University and Brain 360 Integrative Brain Health Center, encompassing 333 patients (248 EM, 85 VM) diagnosed according to the International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition (ICHD-3) criteria between 2021 and 2023 to examine various migraine features and comorbidities. Results: Both EM and VM were predominantly observed in women with similar age distributions. EM patients exhibited significantly longer symptom duration and higher frequencies of nausea, photophobia, and phonophobia (p<0.05). No significant differences were found in vomiting, osmophobia and allodynia rates (p=0.147, p=0.109, p=0.822), while motion sickness was more prevalent in EM (p<0.05). EM patients also showed greater prevalence of migraine family history, menstrual associations, metabolic syndromes, and fibromyalgia (p<0.05). Although headache severity was similar, EM attacks lasted longer. Sleep disorders and medication overuses were more common among EM patients (p<0.05). EM patients reported more sleep disorders, medication overuse, and emotional stress, while dizziness was more common in VM patients (p<0.05). Conclusions: Migraine-like features and comorbidities are generally more prevalent and diverse in EM patients, revealing a distinct pattern compared to VM patients. These findings suggest a broader spectrum of VM symptoms beyond current diagnostic criteria, highlighting the need for more comprehensive longitudinal studies.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Study Population

2.2.1. Inclusion Criteria

2.2.2. Exclusion Criteria

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Demographic and Headache Characteristics

3.2. Migraine-Associated Symptoms

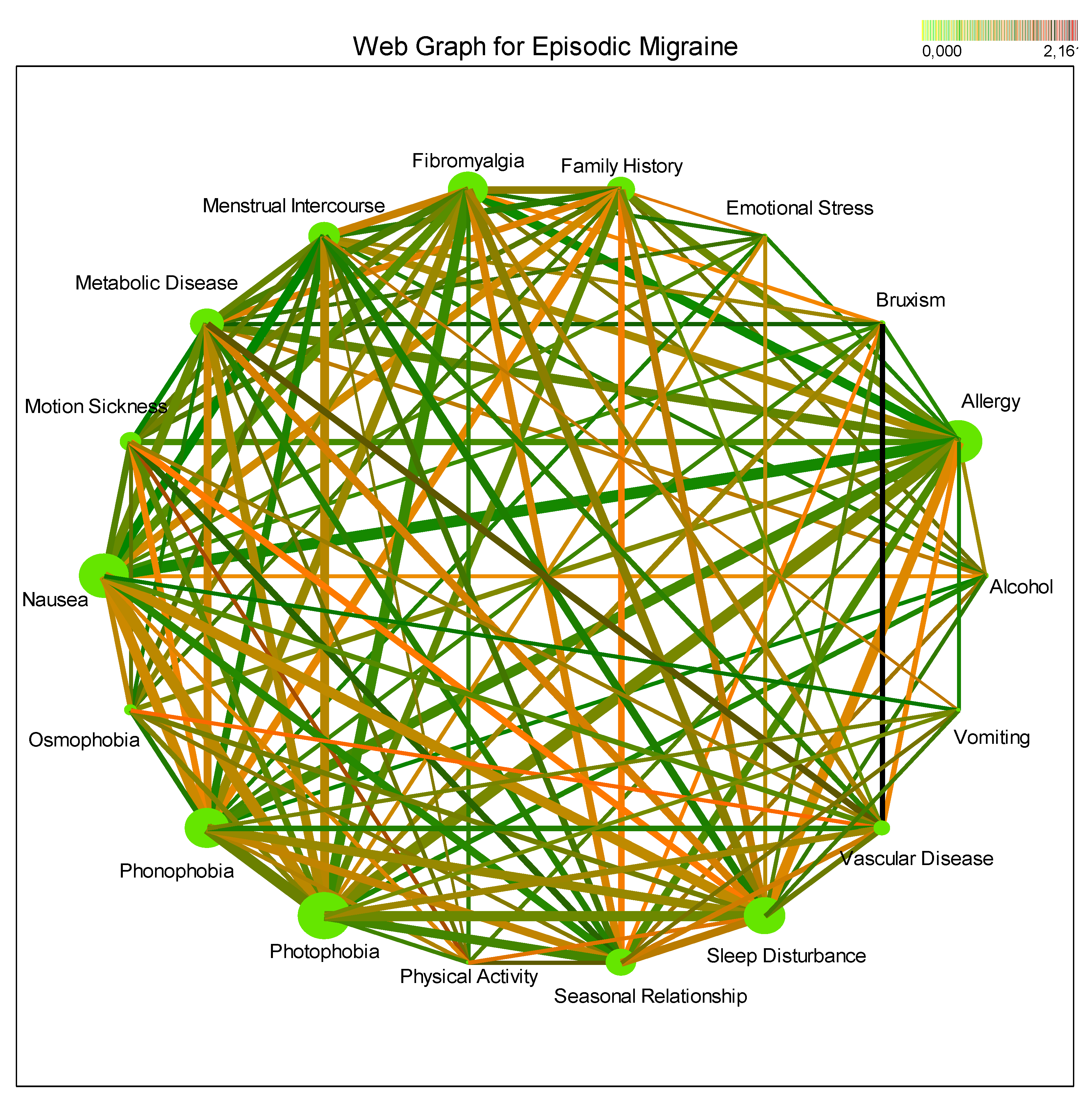

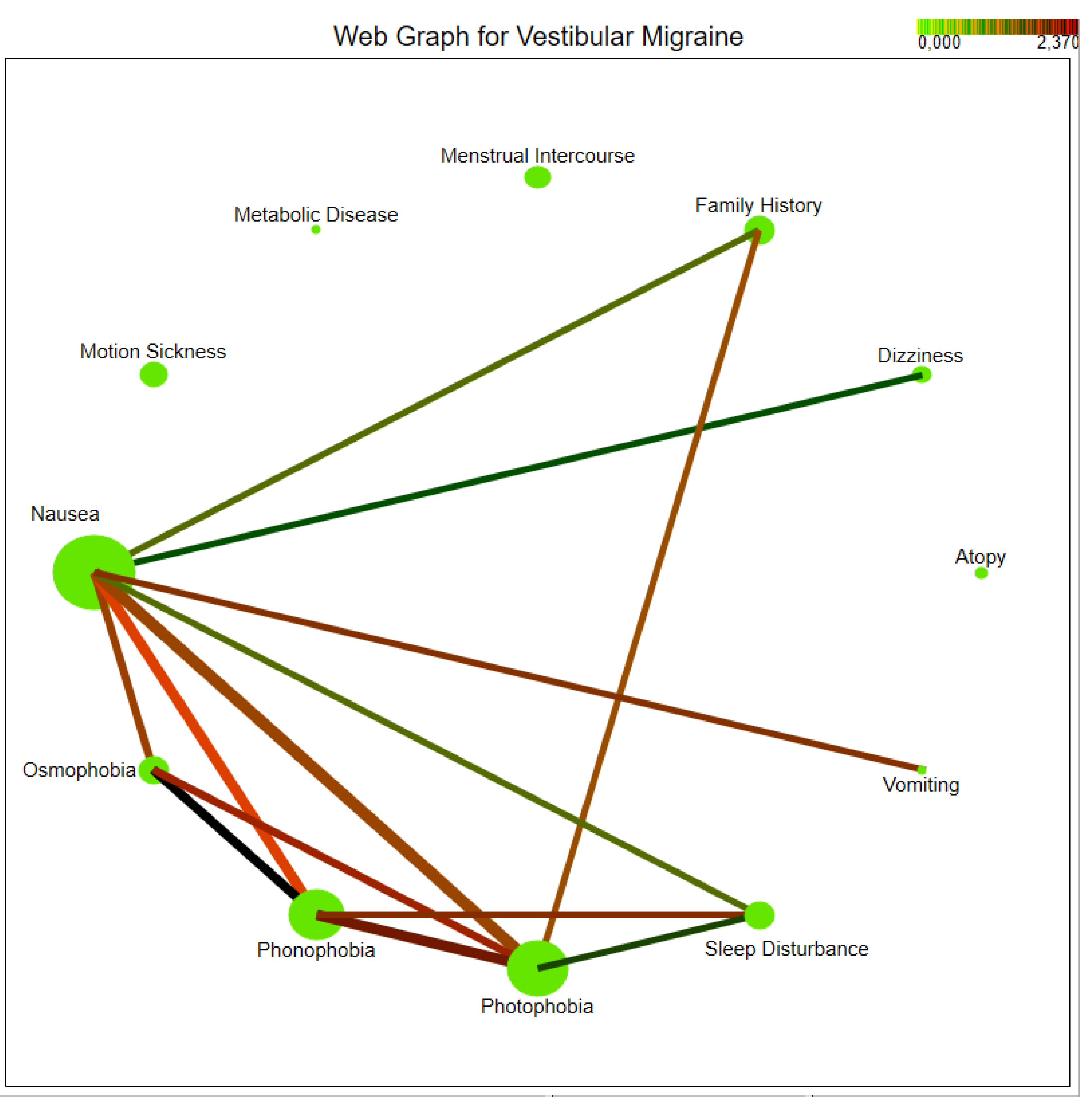

3.3. Comorbidities and Triggers

3.4. Alignment with Bárány Society Diagnostic Criteria

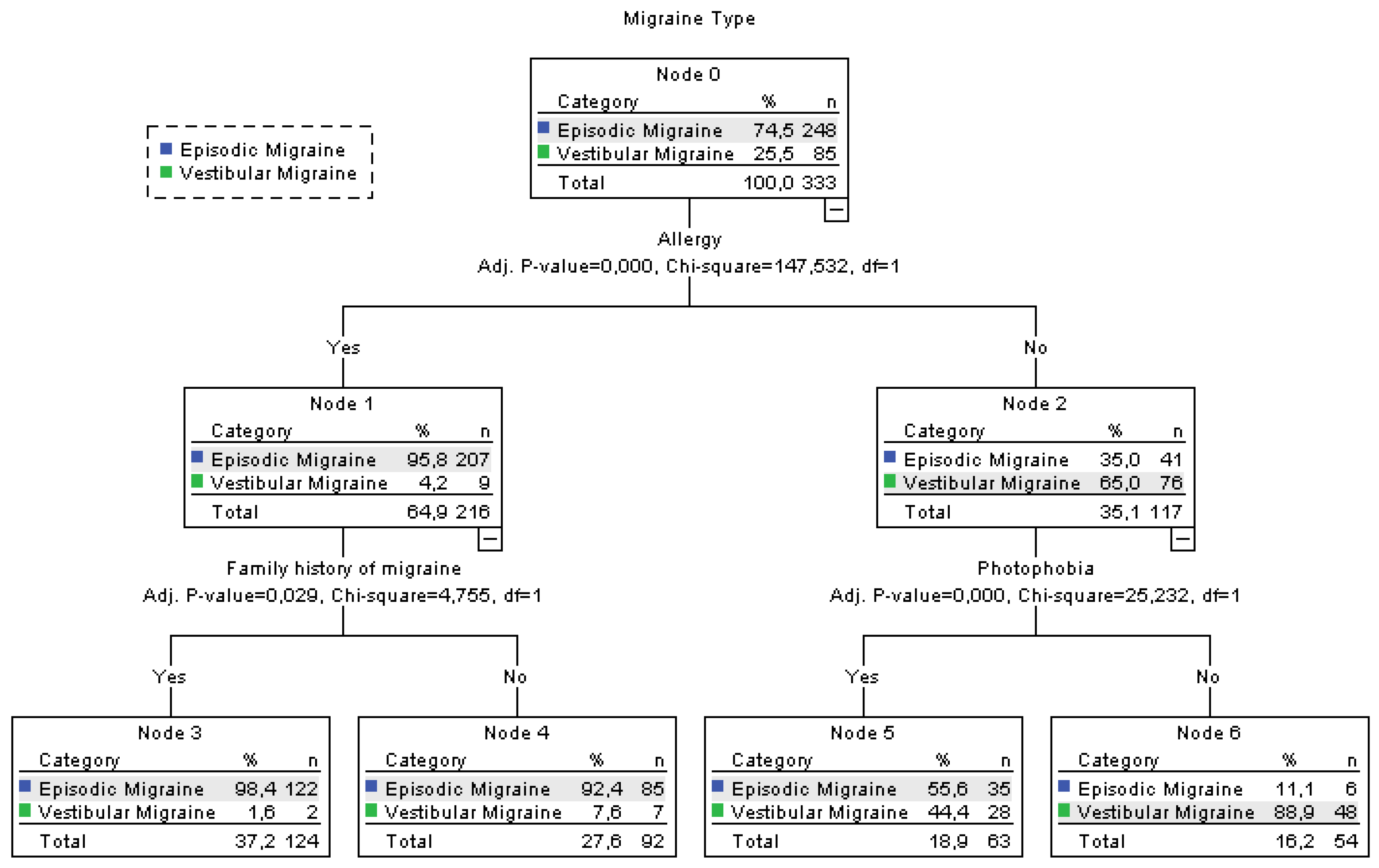

3.5. Allergy-Centered Diagnostic Differentiation Between Episodic and Vestibular Migraine

4. Discussion

4.1. Comparison of Migraine Episodes

4.2. Vestibular Symptoms and Their Importance

4.3. Migraine Features and Diagnostic Clues

4.4. Comorbidities and Their Impact

4.5. Migraine Triggers and Lifestyle Factors

4.6. Limitations

4.7. Clinical Implications and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CART | Classification and Regression Tree |

| df | degrees of freedom |

| EM | Episodic Migraine |

| VM | Vestibular Migraine |

| ICHD-3 | International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition |

| IHS | International Headache Society |

| IRB | Institutional Review Board |

| VAS | Visual Analog Scale |

References

- Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society (IHS). The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition. Cephalalgia 2018, 38, 1–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelman, L. The triggers or precipitants of the acute migraine attack. Cephalalgia: an international journal of headache 2007, 27(5), 394–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, J. H.; Lin, Y. K.; Yang, C. P.; Liang, C. S.; Lee, J. T.; Lee, M. S.; Tsai, C. L.; Lin, G. Y.; Ho, T. H.; Yang, F. C. Prevalence and association of lifestyle and medical-, psychiatric-, and pain-related comorbidities in patients with migraine: A cross-sectional study. Headache 2021, 61(5), 715–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whealy, M.; Nanda, S.; Vincent, A.; Mandrekar, J.; Cutrer, F.M. Fibromyalgia in migraine: a retrospective cohort study. The journal of headache and pain 2018, 19(1), 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Engel, E. R.; Kudrow, D.; Rapoport, A. M. A prospective, open-label study of milnacipran in the prevention of headache in patients with episodic or chronic migraine. Neurological sciences: official journal of the Italian Neurological Society and of the Italian Society of Clinical Neurophysiology 2014, 35(3), 429–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsarava, Z.; Buse, D. C.; Manack, A. N.; Lipton, R. B. Defining the differences between episodic migraine and chronic migraine. Current pain and headache reports 2012, 16(1), 86–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, T.D.; Cutrer, F.M.; Smith, J.H. Episodic status migrainosus: A novel migraine subtype. Cephalalgia 2018, 38(2), 304–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manack, A. N.; Buse, D. C.; Lipton, R. B. Chronic migraine: epidemiology and disease burden. Current pain and headache reports 2011, 15(1), 70–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Domitrz, I.; Lipa, A.; Rożniecki, J.; Stępień, A; Kozubski, W. Treatment and management of migraine in neurological ambulatory practice in Poland by indicating therapy with monoclonal anti-CGRP antibodies. Neurologia i neurochirurgia polska 2020, 54(4), 337–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lempert, T.; Olesen, J.; Furman, J.; Waterston, J.; Seemungal, B.; Carey, J.; Bisdorff, A.; Versino, M.; Evers, S.; Kheradmand, A.; Newman-Toker, D. Vestibular migraine: Diagnostic criteria1. Journal of vestibular research: equilibrium & orientation 2022, 32(1), 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akdal, G.; Ozge, A.; Ergör, G. The prevalence of vestibular symptoms in migraine or tension-type headache. Journal of vestibular research: equilibrium & orientation 2013, 23(2), 101–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domitrz, I.; Lipa, A.; Rożniecki, J.; Stępień, A; Kozubski, W. Treatment and management of migraine in neurological ambulatory practice in Poland by indicating therapy with monoclonal anti-CGRP antibodies. Neurologia i neurochirurgia polska 2020, 54(4), 337–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akdal, G.; Özge, A.; Ergör, G. Vestibular symptoms are more frequent in migraine than in tension type headache patients. Journal of the neurological sciences 2015, 357(1-2), 295–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, Y.; Qi, X.; Wan, T. The Treatment of Vestibular Migraine: A Narrative Review. Annals of Indian Academy of Neurology 2020, 23(5), 602–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richter, F.; Lehmenkühler, A. Cortical spreading depression (CSD): Ein neurophysiologisches Korrelat der Migräneaura [Cortical spreading depression (CSD): a neurophysiological correlate of migraine aura]. Schmerz (Berlin, Germany) 2008, 22(5), 544–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beh, S. C.; Masrour, S.; Smith, S. V.; Friedman, D. I. (The Spectrum of Vestibular Migraine: Clinical Features, Triggers, and Examination Findings. Headache 2019, 59(5), 727–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akdal, G.; Özçelik, P.; Özge, A. Vestibular migraine: Considered from both the vestibular and the migraine point of view. Neurological Sciences and Neurophysiology 2020, 37(2), 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usman, H. O.; Balaban, C. D. Distribution of 5-HT1F Receptors in Monkey Vestibular and Trigeminal Ganglion Cells. Frontiers in neurology 2016, 7, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lempert, T.; Olesen, J.; Furman, J.; Waterston, J.; Seemungal, B.; Carey, J.; Bisdorff, A.; Versino, M.; Evers, S.; Newman-Toker, D. Vestibular migraine: diagnostic criteria. Journal of vestibular research: equilibrium & orientation 2012, 22(4), 167–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neuhauser, H.; Lempert, T. Vertigo and dizziness related to migraine: a diagnostic challenge. Cephalalgia: an international journal of headache 2004, 24(2), 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stolte, B.; Holle, D.; Naegel, S.; Diener, H. C.; Obermann, M. Vestibular migraine. Cephalalgia: an international journal of headache 2015, 35(3), 262–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bisdorff, A.R. Management of vestibular migraine. Therapeutic advances in neurological disorders 2011, 4(3), 183–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çelebisoy, N.; Ak, A. K.; Ataç, C.; Özdemir, H. N.; Gökçay, F.; Durmaz, G. S.; Kartı, D. T.; Toydemir, H. E.; Yayla, V.; Işıkay, İ. Ç.; Erkent, İ.; Sarıtaş, A. Ş.; Özçelik, P.; Akdal, G.; Bıçakcı, Ş.; Göksu, E. O.; Uyaroğlu, F. G. Comparison of clinical features in patients with vestibular migraine and migraine. Journal of neurology 2023, 270(7), 3567–3573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lempert, T.; Neuhauser, H.; Daroff, R.B. Vertigo as a symptom of migraine. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 2009, 1164, 242–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preysner, T. A.; Gardi, A. Z.; Ahmad, S.; Sharon, J. D. Vestibular Migraine: Cognitive Dysfunction, Mobility, Falls. Otology & neurotology: official publication of the American Otological Society, American Neurotology Society [and] European Academy of Otology and Neurotology 2022, 43(10), 1216–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehmet, K. Migraine and vertigo. Headache Res Treat 2011, 2011, 201. [Google Scholar]

- TÜRK, B G.; Yeni, S. N.; Atalar, A. Ç.; Ekizoğlu, E.; Gök, D. K.; Baykan, B.; Özge, A. Exploring shared triggers and potential etiopathogenesis between migraine and idiopathic/genetic epilepsy: Insights from a multicenter tertiary-based study. Clinical Neurology and Neurosurgery 2024, 237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ozcelik, E.U.; Uludüz, E.; Karacı, R.; Domaç, F.M.; İskender, M.; Özge, A.; Uludüz, D. Do comorbidities and triggers expedite chronicity in migraine? Neurological Sciences and Neurophysiology 2023, 40(1), 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Feature | Episodic Migraine (n=248) | Vestibular Migraine (n=85) |

Total (n=333) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 0.180 | |||

| Male | 37 (14.9%) | 18 (21.2%) | 55 (16.5%) | |

| Female | 211 (85.1%) | 67 (78.8%) | 278 (83.5%) | |

| Age (years) | 41.65 ± 10.35 | 39.92 ± 12.62 | 41.2 ± 10.98 | 0.211 |

| Headache Frequency (days/month) |

6.92 ± 4.04 | 6.41 ± 4.08 | 6.86 ± 4.04 | 0.487 |

| Attack Duration (hours) |

8.13 ± 7.8 (2-24) |

6.54 ± 7.97 (1-24) |

7.97 ± 7.82 (1-24) |

0.001 |

| Duration of Symptoms (months) |

228 (132-312) | 60 (24-180) | 204 (96-288) | <0.001 |

| Current Smoker | 26 (10.5%) | 15 (17.6%) | 41 (12.3%) | 0.083 |

| Regular Alcoholic | 81 (32.7%) | 8 (9.4%) | 89 (26.7%) | <0.001 |

| Family History | 146 (58.9%) | 25 (29.4%) | 171 (51.4%) | <0.001 |

| Metabolic Syndrome | 163 (65.7%) | 18 (21.2%) | 181 (54.4%) | <0.001 |

| Vascular Comorbidities | 109 (44%) | 10 (11.8%) | 119 (35.7%) | <0.001 |

| Depression | 44 (17.7%) | 2 (2.4%) | 46 (13.8%) | <0.001 |

| Anxiety | 42 (16.9%) | 12 (14.1%) | 54 (16.2%) | 0.543 |

| Bruxism | 80 (32.3%) | 7 (8.2%) | 87 (26.1%) | <0.001 |

| Fibromyalgia | 182 (73.4%) | 16 (18.8%) | 198 (59.5%) | <0.001 |

| Atopy | 14 (5.6%) | 19 (22.4%) | 33 (9.9%) | <0.001 |

| Dizziness | 0 (0%) | 21 (24.7%) | 21 (6.3%) | <0.001 |

| Medication Overuse | 44 (17.7%) | 4 (4.7%) | 48 (14.4%) | 0.002 |

| VAS Median (Min-Max) |

8 (2-10) | 8 (2-10) | 8 (2-10) | 0.348 |

| Headache Location | 0.362 |

|||

| Unilateral | 134 (54.3%) | 14 (66.7%) | 148 (55.2%) | |

| Bilateral | 113 (45.7%) | 7 (33.3%) | 120 (44.8%) |

| Symptom | Episodic Migraine (n=248) | Vestibular Migraine (n=85) | Total (n=333) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nausea | 213 (85.9%) | 42 (49.4%) | 255 (76.6%) | <0.001 |

| Photophobia | 222 (89.5%) | 35 (41.2%) | 257 (77.2%) | <0.001 |

| Phonophobia | 196 (79%) | 33 (38.8%) | 229 (68.8%) | <0.001 |

| Vomiting | 71 (28.6%) | 18 (21.2%) | 89 (26.7%) | 0.180 |

| Osmophobia | 97 (39.1%) | 25 (29.4%) | 122 (36.6%) | 0.109 |

| Motion Sickness | 124 (50%) | 24 (28.2%) | 148 (44.4%) | <0.001 |

| Allodynia | 13 (5.2%) | 5 (5.9%) | 18 (5.4%) | 0.822 |

| Trigger | Episodic Migraine (n=248) | Vestibular Migraine (n=85) | Total (n=333) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Menstrual Association | 156 (62.9%) | 23 (27.1%) | 179 (53.8%) | <0.001 |

| Seasonal Changes | 152 (61.3%) | 13 (15.3%) | 165 (49.5%) | <0.001 |

| Sleep Disorder | 187 (75.4%) | 25 (29.4%) | 212 (63.7%) | <0.001 |

| Physical Activity | 70 (28.2%) | 3 (3.5%) | 73 (21.9%) | <0.001 |

| Emotional Stress | 75 (30.2%) | 13 (15.3%) | 88 (26.4%) | 0.007 |

| Allergy | 207 (83.5%) | 9 (10.6%) | 216 (64.9%) | <0.001 |

| Barany Society Vestibular Migraine Diagnostic Criteria | Our Data Variables | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| A. At least five episodes | Episode Frequency | Our data includes the frequency of headache days per month: EM (6.92±4.04), VM (6.41±4.08) days. |

| B. Current or previous history of migraine with or without aura | Diagnosis of EM or VM | Our study population includes 248 EM and 85 VM patients. |

| C. Vestibular symptoms of moderate or severe intensity, lasting between 5 minute and 72 hours | Duration and Severity of Vestibular Symptoms | Duration of symptoms: EM (8.13±7.8 hours), VM (6.54±7.97 hours). Dizziness is more common in VM (24.7%). |

| D. At least 50% of episodes are associated with at least one of the following three migranous features: | ||

| 1. Headache with at least two of the following characteristics: | Headache Characteristics | |

| - Unilateral location | Headache Location (Unilateral/Bilateral) | Unilateral headaches: EM (54.3%), VM (66.7%). |

| - Pulsating quality | Not directly measured | Inferred from patient descriptions. |

| - Moderate or severe pain intensity | Headache Severity (VAS score) | Both groups had a median VAS score of 8 (range 2-10). |

| - Aggravation by routine physical activity | Physical Activity Trigger | Physical activity trigger: EM (28.2%), VM (3.5%). |

| 2. Photophobia and phonophobia | Photophobia and Phonophobia | Photophobia: EM (89.5%), VM (41.2%). Phonophobia: EM (79%), VM (38.8%). |

| 3. Visual aura | Not measured | This variable was not directly measured in our study. |

| E. Not better accounted for by another ICHD-3 diagnosis or another vestibular disorder | Exclusion of Other Diagnoses | Exclusion criteria ensured the exclusion of other primary headaches and significant psychiatric or neurological disorders. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.