Submitted:

25 December 2025

Posted:

25 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

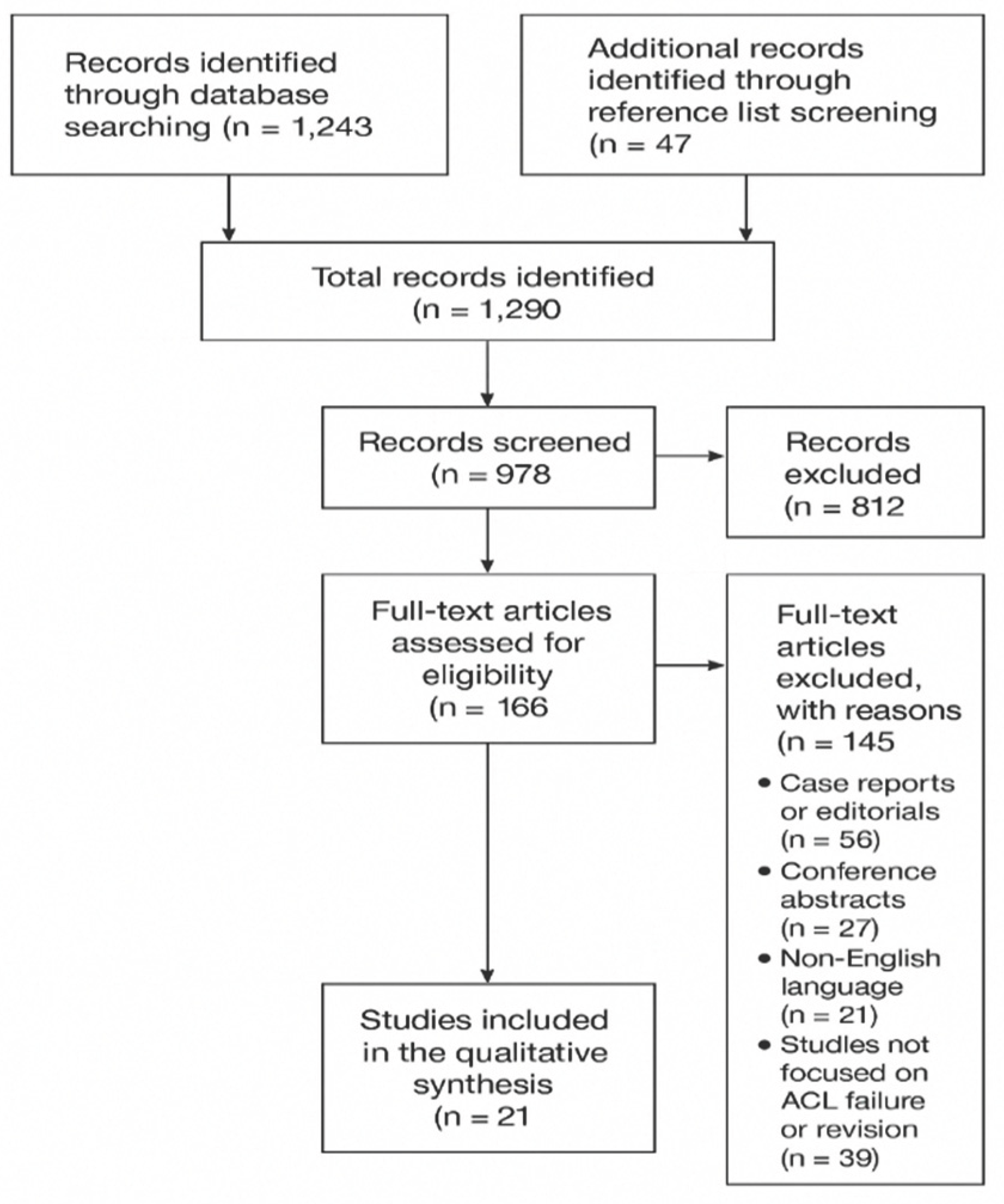

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Etiology of ACL Reconstruction Failure

3.2. Classification of Failure

3.3. Treatment and Surgical Strategies

4. Discussion

4.1. Study Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ACL | Anterior Cruciate Ligament |

| ALL | Anterolateral Ligament |

| BPTB | Bone–Patellar Tendon–Bone |

| CT | Computed Tomography |

| LET | Lateral Extra-articular Tenodesis |

| MRI | Magnetic Resonance Imaging |

| MARS | Multicenter ACL Revision Study |

| PLC | Posterolateral Corner |

| ROM | Range of Motion |

| ESSKA | European Society of Sports Traumatology, Knee Surgery & Arthroscopy |

| BMI | Body Mass Index |

References

- Domnick, C.; Raschke, M.J.; Herbort, M. Biomechanics of the anterior cruciate ligament: Physiology, rupture and reconstruction techniques. World J Orthop. 2016, 7, 82–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Brinlee, A.W.; Dickenson, S.B.; Hunter-Giordano, A.; Snyder-Mackler, L. ACL Reconstruction Rehabilitation: Clinical Data, Biologic Healing, and Criterion-Based Milestones to Inform a Return-to-Sport Guideline. Sports Health 2022, 14, 770–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Yao, S.; Fu, B.S.; Yung, P.S. Graft healing after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction (ACLR) https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asmart.2021.03.003. Asia Pac J Sports Med Arthrosc Rehabil Technol. Erratum in: Asia Pac J Sports Med Arthrosc Rehabil Technol. 2021 Aug 13, 26, 58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asmart.2021.08.001. PMID: 34094881; PMCID: PMC8134949. 2021, 25, 8–15. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gerami, M.H.; Haghi, F.; Pelarak, F.; Mousavibaygei, S.R. Anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injuries: A review on the newest reconstruction techniques. J Family Med Prim Care 2022, 11, 852–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Samitier, G.; Marcano, A.I.; Alentorn-Geli, E.; Cugat, R.; Farmer, K.W.; Moser, M.W. Failure of Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction. Arch Bone Jt Surg. 2015, 3, 220–240. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Aldag, L.; Dallman, J.; Henkelman, E.; Herda, A.; Randall, J.; Tarakemeh, A.; Morey, T.; Vopat, B.G. Various Definitions of Failure Are Used in Studies of Patients Who Underwent Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction. Arthrosc Sports Med Rehabil. 2023, 5, 100801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Tischer, T.; Andriolo, L.; Beaufils, P.; Ahmad, S.S.; Bait, C.; Bonomo, M.; Cavaignac, E.; Cristiani, R.; Feucht, M.J.; Fiodorovas, M.; Grassi, A.; Helmerhorst, G.; Hoser, C.; Karahan, M.; Komnos, G.; Lagae, K.C.; Madonna, V.; Monaco, E.; Monllau, J.C.; Ollivier, M.; Ovaska, M.; Petersen, W.; Piontek, T.; Robinson, J.; Samuelsson, K.; Scheffler, S.; Sonnery-Cottet, B.; Filardo, G.; Condello, V. Management of anterior cruciate ligament revision in adults: the 2022 ESSKA consensus part III-indications for different clinical scenarios using the RAND/UCLA appropriateness method. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2023, 31, 4662–4672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kakarlapudi, T.K.; Bickerstaff, D.R. Knee instability: isolated and complex. West J Med. 2001, 174, 266–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Nedder, V.J.; Raju, A.G.; Moyal, A.J.; Calcei, J.G.; Voos, J.E. Impact of Psychological Factors on Rehabilitation After Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction: A Systematic Review. Sports Health 2025, 17, 291–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Tátrai, M.; Halasi, T.; Tállay, A.; Tátrai, A.; Karácsony, A.F.; Papp, E.; Pavlik, A. Higher revision and secondary surgery rates after ACL reconstruction in athletes under 16 compared to those over 16: a case-control study. J Orthop Surg Res. 2025, 20, 597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Wilde, J.; Bedi, A.; Altchek, D.W. Revision anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Sports Health 2014, 6, 504–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Diquattro, E.; Jahnke, S.; Traina, F.; Perdisa, F.; Becker, R.; Kopf, S. ACL surgery: reasons for failure and management. EFORT Open Rev. 2023, 8, 319–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Roethke, L.C.; Braaten, J.A.; Rodriguez, A.N.; LaPrade, R.F. Revision Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction (ACLR): Causes and How to Minimize Primary ACLR Failure. Arch Bone Jt Surg. 2023, 11, 80–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Belkhelladi, M.; Cierson, T.; Martineau, P.A. Biomechanical Risk Factors for Increased Anterior Cruciate Ligament Loading and Injury: A Systematic Review. Orthop J Sports Med. 2025, 13, 23259671241312681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kemler, B.; Coladonato, C.; Perez, A.; Erickson, B.J.; Tjoumakaris, F.P.; Freedman, K.B. Considerations for revision anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: A review of the current literature. J Orthop. 2024, 56, 57–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; Chou, R.; Glanville, J.; Grimshaw, J.M.; Hróbjartsson, A.; Lalu, M.M.; Li, T.; Loder, E.W.; Mayo-Wilson, E.; McDonald, S.; McGuinness, L.A.; Stewart, L.A.; Thomas, J.; Tricco, A.C.; Welch, V.A.; Whiting, P.; Moher, D. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Yan, X.; Yang, X.G.; Feng, J.T.; Liu, B.; Hu, Y.C. Does Revision Anterior Cruciate Ligament (ACL) Reconstruction Provide Similar Clinical Outcomes to Primary ACL Reconstruction? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Orthop Surg. 2020, 12, 1534–1546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Li, X.; Yan, L.; Li, D.; Fan, Z.; Liu, H.; Wang, G.; Jiu, J.; Yang, Z.; Li, J.J.; Wang, B. Failure modes after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int Orthop. 2023, 47, 719–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burnham, J.M.; Malempati, C.S.; Carpiaux, A.; Ireland, M.L.; Johnson, D.L. Anatomic Femoral and Tibial Tunnel Placement During Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction: Anteromedial Portal All-Inside and Outside-In Techniques. Arthrosc Tech. 2017, 6, e275–e282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ostojic, M.; Indelli, P.F.; Lovrekovic, B.; Volcarenghi, J.; Juric, D.; Hakam, H.T.; Salzmann, M.; Ramadanov, N.; Królikowska, A.; Becker, R.; Prill, R. Graft Selection in Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction: A Comprehensive Review of Current Trends. Medicina (Kaunas) 2024, 60, 2090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Runer, A.; Suter, A.; Roberti di Sarsina, T.; Jucho, L.; Gföller, P.; Csapo, R.; Hoser, C.; Fink, C. Quadriceps tendon autograft for primary anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction show comparable clinical, functional, and patient-reported outcome measures, but lower donor-site morbidity compared with hamstring tendon autograft: A matched-pairs study with a mean follow-up of 6.5 years. J ISAKOS 2023, 8, 60–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albishi, W.; Baltow, B.; Albusayes, N.; Sayed, A.A.; Alrabai, H.M. Hamstring autograft utilization in reconstructing anterior cruciate ligament: Review of harvesting techniques, graft preparation, and different fixation methods. World J Orthop. 2022, 13, 876–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Spindler, K.P. The Multicenter ACL Revision Study (MARS): a prospective longitudinal cohort to define outcomes and independent predictors of outcomes for revision anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. J Knee Surg. 2007, 20, 303–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, D.; Slawaska-Eng, D.; Almasri, M.; Sheean, A.; de Sa, D. Quadricep ACL Reconstruction Techniques and Outcomes: an Updated Scoping Review of the Quadricep Tendon. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med. 2021, 14, 462–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Moretti, L.; Garofalo, R.; Cassano, G.D.; Geronimo, A.; Reggente, N.; Piacquadio, F.; Bizzoca, D.; Solarino, G. Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction with LARS Synthetic Ligament: Outcomes and Failures. J Clin Med. 2024, 14, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Stranger, N.; Kaulfersch, C.; Mattiassich, G.; Mandl, J.; Hausbrandt, P.A.; Szolar, D.; Schöllnast, H.; Tillich, M. Frequency of anterolateral ligament tears and ramp lesions in patients with anterior cruciate ligament tears and associated injuries indicative for these lesions-a retrospective MRI analysis. Eur Radiol. 2023, 33, 4833–4841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Dadgostar, H.; Zarrini, M.; Hoveidaei, A.H.; Sattarpour, R.; Razi, S.; Arasteh, P.; Razi, M. Two-Year Functional Outcomes of Nonsurgical Treatment in Concomitant Anterior Cruciate Ligament and Medial Collateral Ligament Injuries: A Case-Control Study. J Knee Surg. 2024, 37, 730–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nazzal, E.M.; Zsidai, B.; Pujol, O.; Kaarre, J.; Curley, A.J.; Musahl, V. Considerations of the Posterior Tibial Slope in Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction: a Scoping Review. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med. 2022, 15, 291–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Madhan, A.S.; Ganley, T.J.; McKay, S.D.; Pandya, N.K.; Patel, N.M. Trends in Anterolateral Ligament Reconstruction and Lateral Extra-articular Tenodesis With ACL Reconstruction in Children and Adolescents. Orthop J Sports Med. 2022, 10, 23259671221088049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Guarino, A.; Farinelli, L.; Iacono, V.; Screpis, D.; Piovan, G.; Rizzo, M.; Mariconda, M.; Zorzi, C. Lateral extra-articular tenodesis and anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction in young patients: clinical results and return to sport. Orthop Rev (Pavia) 2022, 14, 33696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zampolini, M; Selb, M; Boldrini, P; Branco, CA; Golyk, V; Hu, X; Kiekens, C; Negrini, S; Nulle, A; Oral, A; Sgantzos, M; Shmonin, A; Treger, I; Stucki, G. UEMS-PRM Section and Board. The Individual Rehabilitation Project as the core of person-centered rehabilitation: the Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine Section and Board of the European Union of Medical Specialists Framework for Rehabilitation in Europe. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med. 2022, 58, 503–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Comodo, R. M.; Grassa, D.; Motassime, A. E.; Bocchino, G.; Totti, R.; De Fazio, A.; Meschini, C.; Capece, G.; Maccauro, G.; Vitiello, R. Telerehabilitation in Hip and Knee Arthroplasty: A Narrative Review of Clinical Outcomes, Patient-Reported Measures, and Implementation Challenges. Journal of Functional Morphology and Kinesiology 2025, 10, 370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.; Liu, D.; Zhou, G.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, X. Robot-assisted anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction based on three-dimensional images. J Orthop Surg Res. 2024, 19, 246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Capece, G.; Andriollo, L.; Sangaletti, R.; Righini, R.; Benazzo, F.; Rossi, S.M.P. Advancements and Strategies in Robotic Planning for Knee Arthroplasty in Patients with Minor Deformities. Life (Basel) 2024, 14, 1528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Migliorini, F.; Lucenti, L.; Mok, Y.R.; Bardazzi, T.; D'Ambrosi, R.; De Carli, A.; Paolicelli, D.; Maffulli, N. Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction Using Lateral Extra-Articular Procedures: A Systematic Review. Medicina (Kaunas) 2025, 61, 294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Bian, D.; Lin, Z.; Lu, H.; Zhong, Q.; Wang, K.; Tang, X.; Zang, J. The application of extended reality technology-assisted intraoperative navigation in orthopedic surgery. Front Surg. 2024, 11, 1336703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Xiao, M.; van Niekerk, M.; Trivedi, N.N.; Hwang, C.E.; Sherman, S.L.; Safran, M.R.; Abrams, G.D. Patients Who Return to Sport After Primary Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction Have Significantly Higher Psychological Readiness: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of 3744 Patients. Am J Sports Med. 2023, 51, 2774–2783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria |

|---|---|

| Original research, narrative/systematic reviews, consensus statements, and multicenter studies on ACL reconstruction failure | Case reports, editorials, letters, conference abstracts |

| Studies addressing definitions, etiology (technical, biological, or traumatic), or surgical management of ACL failure | Studies not directly related to ACL reconstruction or revision |

| English-language publications (2000–2024) | Non-English publications |

| Etiology | Description | Approximate Frequency |

| Technical causes | Tunnel malposition (femoral anterior, tibial posterior), poor graft choice, fixation errors | 60 % – 70 % |

| Traumatic causes | High-energy trauma, especially within first postoperative year | 15 % – 25 % |

| Biological causes | Poor graft osteointegration, revascularization or ligamentization | 10 % – 15 % |

| Factor | Incidence / Rate | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Overall failure rate | 4 % – 25 % | Varies by demographics and activity level |

| Female patients (< 20 or > 40 years) | Higher incidence | Hormonal and biomechanical influences |

| Adolescents (< 20 years) | Up to 35 % failure | Highest risk subgroup; early return to sport |

| Revision surgery success rate | ~ 75 % | Lower in adolescents and high-level athletes |

| Early return to sport (< 9 months) | ↑ failure risk | Associated with incomplete graft maturation |

| Time from Surgery | Common Causes | Clinical Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Early (< 3 months) | Fixation failure, infection | Requires urgent management |

| Mid-term (3–12 months) | Technical errors, aggressive rehab, missed lesions | Surgical re-evaluation critical |

| Late (> 12 months) | New trauma, graft elongation, degenerative widening | Assess for secondary instability |

| Graft Type | Advantages | Disadvantages | Indications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bone–Patellar Tendon–Bone (BPTB) | Strong bone-to-bone healing, rigid fixation | Anterior knee pain, donor-site morbidity | Reuse of previous tunnels, high-demand athletes |

| Quadriceps Tendon | Versatile, low donor-site morbidity, large cross-section | Less widespread familiarity | Complex or revision cases |

| Hamstring Tendon | Good strength, minimal anterior knee pain | Weaker fixation in enlarged tunnels | Primary or single-stage revisions |

| Allograft | No donor morbidity, shorter operative time | Higher re-rupture rate in young patients | Older or low-demand individuals |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).