Submitted:

24 December 2025

Posted:

25 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Unsuccessful Disease-Modifying Therapies in PD

2.1. MAO-B Inhibitors and Dopaminergic Modulators

2.2. L-Type Calcium Channel Block

2.3. Antioxidants and Bioenergetic Supplements

2.4. αSyn Immunotherapies

2.5. c-Abl Kinase Inhibition

2.6. Iron Chelation

2.7. GLP-1 Receptor Agonists and Incretin-Based Strategies

3. Repurposing Existing Drugs

3.1. Glycolysis-Enhancing Drugs

3.2. Challenges in Repurposing

4. Ongoing Trials

4.1. αSyn Targeted

4.2. Inflammation/Immune Pathways

4.3. GLP1 Agonists

4.4. Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors

4.5. Cell-Based Therapies

4.6. RNA-Based Therapies

5. Gene Therapy

5.1. GBA

5.2. GAD-65 and GAD-67

5.3. GDNF and Neurturin (CERE-120)

5.4. TH, GCH, and AADC

6. Future Studies

7. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AADC | Aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase deficiency |

| AAV | Adeno-associated virus |

| ASO | Antisense oligonucleotide |

| BBB | Blood-brain barrier |

| CCB | Calcium channel blocker |

| CNS | Central nervous system |

| CSF | Cerebrospinal fluid |

| DME | Disease-modifying effect |

| DMT | Disease-modifying therapy |

| GABA | γ-aminobutyric acid |

| GAD | Glutamic acid decarboxylase |

| GBA | Glucocerebrosidase |

| GCH | GTP cyclohydrolase I |

| H&Y | Hoehn and Yahr |

| IRR | Incidence rate ratio |

| LSMD | Least squares mean difference |

| LRRK2 | Leucine-rich repeat kinase 2 |

| MAO | Monoamine oxidase |

| MPTP | 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine |

| PD | Parkinson’s disease |

| PPAR-γ | Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor gamma |

| STN | Subthalamic nucleus |

| TH | Tyrosine hydroxylase |

| UPDRS | Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale |

| αSyn | α-Synuclein |

Appendix A

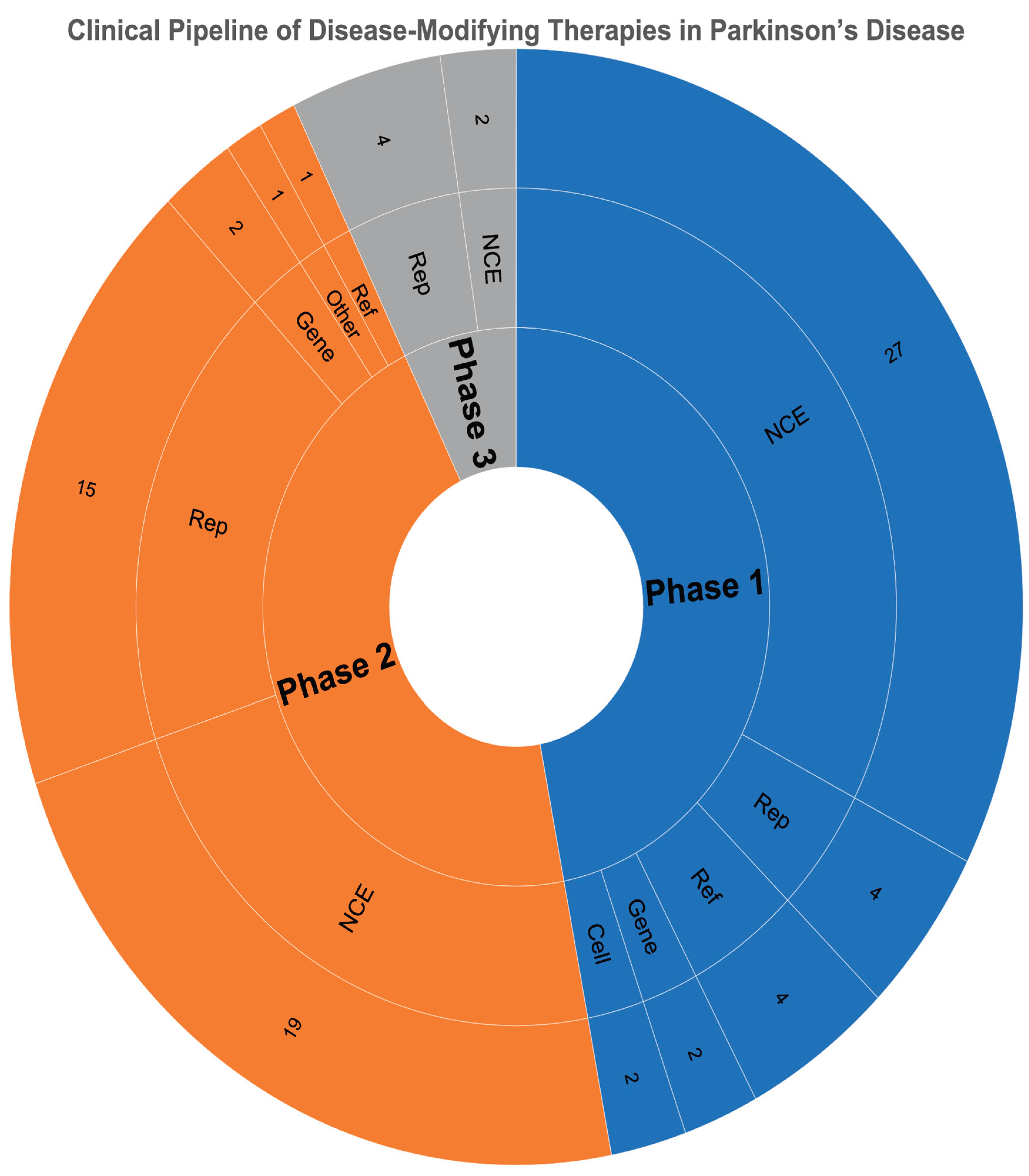

| Type | Phase 1 | Phase 2 | Phase 3 |

| Cell | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Gene | 2 | 2 | 0 |

| NCE | 27 | 19 | 2 |

| Reformulation | 4 | 1 | 0 |

| Repurposed | 4 | 15 | 4 |

| Other | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Total | 39 | 38 | 6 |

References

- Buchmann, C.; Bouchard, M. New Perspectives on Parkinson’s Disease Subtyping: A Narrative Review. Can J Neurol Sci 2025, 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Trevisan, L.; Gaudio, A.; Monfrini, E.; Avanzino, L.; Di Fonzo, A.; Mandich, P. Genetics in Parkinson’s Disease, State-of-the-Art and Future Perspectives. Br Med Bull 2024, 149, 60–71. [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, M. Parkinson’s Disease: Bridging Gaps, Building Biomarkers, and Reimagining Clinical Translation. Cells 2025, 14. [CrossRef]

- Wüllner, U.; Borghammer, P.; Choe, C.-U.; Csoti, I.; Falkenburger, B.; Gasser, T.; Lingor, P.; Riederer, P. The Heterogeneity of Parkinson’s Disease. J Neural Transm (Vienna) 2023, 130, 827–838. [CrossRef]

- Pitton Rissardo, J.; McGarry, A.; Shi, Y.; Fornari Caprara, A.L.; Kannarkat, G.T. Alpha-Synuclein Neurobiology in Parkinson’s Disease: A Comprehensive Review of Its Role, Mechanisms, and Therapeutic Perspectives. Brain Sciences 2025, 15, 1260. [CrossRef]

- Smith, L.J.; Lee, C.-Y.; Menozzi, E.; Schapira, A.H.V. Genetic Variations in GBA1 and LRRK2 Genes: Biochemical and Clinical Consequences in Parkinson Disease. Front Neurol 2022, 13, 971252. [CrossRef]

- Kalia, L.V.; Lang, A.E. Parkinson’s Disease. Lancet 2015, 386, 896–912. [CrossRef]

- Espay, A.J.; Kalia, L.V.; Gan-Or, Z.; Williams-Gray, C.H.; Bedard, P.L.; Rowe, S.M.; Morgante, F.; Fasano, A.; Stecher, B.; Kauffman, M.A.; et al. Disease Modification and Biomarker Development in Parkinson Disease: Revision or Reconstruction? Neurology 2020, 94, 481–494. [CrossRef]

- Kaitwad, R.; Gulwe, A.; Dipke, C.; Suryawanshi, H.; Murge, N.; Nalage, D. Current and Emerging Therapies for Parkinson’s Disease: Advances toward Disease Modification. Life Res 2025, 8, 22. [CrossRef]

- Rissardo, J.P.; Caprara, A.L. A Narrative Review on Biochemical Markers and Emerging Treatments in Prodromal Synucleinopathies. Clinics and Practice 2025, 15. [CrossRef]

- Stocchi, F.; Bravi, D.; Emmi, A.; Antonini, A. Parkinson Disease Therapy: Current Strategies and Future Research Priorities. Nat Rev Neurol 2024, 20, 695–707. [CrossRef]

- Costa, J.; Lunet, N.; Santos, C.; Santos, J.; Vaz-Carneiro, A. Caffeine Exposure and the Risk of Parkinson’s Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies. J Alzheimers Dis 2010, 20 Suppl 1, S221-238. [CrossRef]

- Torti, M.; Vacca, L.; Stocchi, F. Istradefylline for the Treatment of Parkinson’s Disease: Is It a Promising Strategy? Expert Opin Pharmacother 2018, 19, 1821–1828. [CrossRef]

- Lang Anthony E.; Siderowf Andrew D.; Macklin Eric A.; Poewe Werner; Brooks David J.; Fernandez Hubert H.; Rascol Olivier; Giladi Nir; Stocchi Fabrizio; Tanner Caroline M.; et al. Trial of Cinpanemab in Early Parkinson’s Disease. New England Journal of Medicine 2022, 387, 408–420. [CrossRef]

- Pagano, G.; Taylor, K.I.; Anzures-Cabrera, J.; Marchesi, M.; Simuni, T.; Marek, K.; Postuma, R.B.; Pavese, N.; Stocchi, F.; Azulay, J.-P.; et al. Trial of Prasinezumab in Early-Stage Parkinson’s Disease. N Engl J Med 2022, 387, 421–432. [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Jiménez, F.J.; Alonso-Navarro, H.; García-Martín, E.; Agúndez, J.A.G. Coenzyme Q10 and Parkinsonian Syndromes: A Systematic Review. J Pers Med 2022, 12. [CrossRef]

- Attia; Ahmed, H.; Gadelkarim, M.; Morsi, M.; Awad, K.; Elnenny, M.; Ghanem, E.; El-Jaafary, S.; Negida, A. Meta-Analysis of Creatine for Neuroprotection Against Parkinson’s Disease. CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets 2017, 16, 169–175. [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Pang, D.; Li, C.; Ou, R.; Yu, Y.; Cui, Y.; Huang, J.; Shang, H. Calcium Channel Blockers and Parkinson’s Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Ther Adv Neurol Disord 2024, 17, 17562864241252713. [CrossRef]

- Dooley, M.; Markham, A. Pramipexole. A Review of Its Use in the Management of Early and Advanced Parkinson’s Disease. Drugs Aging 1998, 12, 495–514. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Chen, M. The Effect and Safety of Ropinirole in the Treatment of Parkinson Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Medicine (Baltimore) 2021, 100, e27653. [CrossRef]

- Rajendran, A.; Reddy, A.J.; Bisaga, K.; Sommer, D.A.; Prakash, N.; Pokala, V.T.; Yu, Z.; Bachir, M.; Nawathey, N.; Brahmbhatt, T.; et al. A Systematic Review of the Usage of Rotigotine During Early and Advanced Stage Parkinson’s. Cureus 2023, 15, e36211. [CrossRef]

- Hickey, P.; Stacy, M. AAV2-Neurturin (CERE-120) for Parkinson’s Disease. Expert Opin Biol Ther 2013, 13, 137–145. [CrossRef]

- Jankovic, J.; Hunter, C. A Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled and Longitudinal Study of Riluzole in Early Parkinson’s Disease. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 2002, 8, 271–276. [CrossRef]

- Schapira, A.H.V. Monoamine Oxidase B Inhibitors for the Treatment of Parkinson’s Disease: A Review of Symptomatic and Potential Disease-Modifying Effects. CNS Drugs 2011, 25, 1061–1071. [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Tao, Y.; Li, J.; Kang, M. Pioglitazone Use Is Associated with Reduced Risk of Parkinson’s Disease in Patients with Diabetes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Clin Neurosci 2022, 106, 154–158. [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.; Qiao, L.; Tian, J.; Liu, A.; Wu, J.; Huang, J.; Shen, M.; Lai, X. Effect of Statins on Parkinson’s Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Medicine (Baltimore) 2019, 98, e14852. [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.; Yuan, P.; Kou, L.; Chen, X.; Li, J.; Li, Y. Nilotinib in Parkinson’s Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front Aging Neurosci 2022, 14, 996217. [CrossRef]

- Basile, M.S.; Bramanti, P.; Mazzon, E. Inosine in Neurodegenerative Diseases: From the Bench to the Bedside. Molecules 2022, 27. [CrossRef]

- McGhee, D.J.M.; Ritchie, C.W.; Zajicek, J.P.; Counsell, C.E. A Review of Clinical Trial Designs Used to Detect a Disease-Modifying Effect of Drug Therapy in Alzheimer’s Disease and Parkinson’s Disease. BMC Neurol 2016, 16, 92. [CrossRef]

- Macleod, A.D.; Counsell, C.E.; Ives, N.; Stowe, R. Monoamine Oxidase B Inhibitors for Early Parkinson’s Disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2005, 2005, CD004898. [CrossRef]

- DATATOP: A Multicenter Controlled Clinical Trial in Early Parkinson’s Disease. Parkinson Study Group. Arch Neurol 1989, 46, 1052–1060. [CrossRef]

- Ward, C.D. Does Selegiline Delay Progression of Parkinson’s Disease? A Critical Re-Evaluation of the DATATOP Study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1994, 57, 217–220. [CrossRef]

- Olanow, C.W.; Rascol, O.; Hauser, R.; Feigin, P.D.; Jankovic, J.; Lang, A.; Langston, W.; Melamed, E.; Poewe, W.; Stocchi, F.; et al. A Double-Blind, Delayed-Start Trial of Rasagiline in Parkinson’s Disease. N Engl J Med 2009, 361, 1268–1278. [CrossRef]

- Jenner, P.; Langston, J.W. Explaining ADAGIO: A Critical Review of the Biological Basis for the Clinical Effects of Rasagiline. Mov Disord 2011, 26, 2316–2323. [CrossRef]

- Verschuur, C.V.M.; Suwijn, S.R.; Boel, J.A.; Post, B.; Bloem, B.R.; van Hilten, J.J.; van Laar, T.; Tissingh, G.; Munts, A.G.; Deuschl, G.; et al. Randomized Delayed-Start Trial of Levodopa in Parkinson’s Disease. N Engl J Med 2019, 380, 315–324. [CrossRef]

- Schapira, A.H.V.; McDermott, M.P.; Barone, P.; Comella, C.L.; Albrecht, S.; Hsu, H.H.; Massey, D.H.; Mizuno, Y.; Poewe, W.; Rascol, O.; et al. Pramipexole in Patients with Early Parkinson’s Disease (PROUD): A Randomised Delayed-Start Trial. Lancet Neurol 2013, 12, 747–755. [CrossRef]

- Parkinson Study Group CALM Cohort Investigators Long-Term Effect of Initiating Pramipexole vs Levodopa in Early Parkinson Disease. Arch Neurol 2009, 66, 563–570. [CrossRef]

- Stowe, R.L.; Ives, N.J.; Clarke, C.; van Hilten, J.; Ferreira, J.; Hawker, R.J.; Shah, L.; Wheatley, K.; Gray, R. Dopamine Agonist Therapy in Early Parkinson’s Disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2008, CD006564. [CrossRef]

- Becker, C.; Jick, S.S.; Meier, C.R. Use of Antihypertensives and the Risk of Parkinson Disease. Neurology 2008, 70, 1438–1444. [CrossRef]

- Parkinson Study Group Phase II Safety, Tolerability, and Dose Selection Study of Isradipine as a Potential Disease-Modifying Intervention in Early Parkinson’s Disease (STEADY-PD). Mov Disord 2013, 28, 1823–1831. [CrossRef]

- Simuni, T. A Phase 3 Study of Isradipine as a Disease Modifying Agent in Patients with Early Parkinson’s Disease (STEADY-PD III): Final Study Results: 206. Mov Disord 2019, 34, S87.

- Siddiqi, F.H.; Menzies, F.M.; Lopez, A.; Stamatakou, E.; Karabiyik, C.; Ureshino, R.; Ricketts, T.; Jimenez-Sanchez, M.; Esteban, M.A.; Lai, L.; et al. Felodipine Induces Autophagy in Mouse Brains with Pharmacokinetics Amenable to Repurposing. Nat Commun 2019, 10, 1817. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, S.; Wang, Y.; Tang, S.; Guo, Y.; Ma, D.; Jiang, X. Mechanism of Nimodipine in Treating Neurodegenerative Diseases: In Silico Target Identification and Molecular Dynamic Simulation. Front Pharmacol 2025, 16, 1549953. [CrossRef]

- Beal, M.F.; Oakes, D.; Shoulson, I.; Henchcliffe, C.; Galpern, W.R.; Haas, R.; Juncos, J.L.; Nutt, J.G.; Voss, T.S.; Ravina, B.; et al. A Randomized Clinical Trial of High-Dosage Coenzyme Q10 in Early Parkinson Disease: No Evidence of Benefit. JAMA Neurol 2014, 71, 543–552. [CrossRef]

- Kieburtz, K.; Tilley, B.C.; Elm, J.J.; Babcock, D.; Hauser, R.; Ross, G.W.; Augustine, A.H.; Augustine, E.U.; Aminoff, M.J.; Bodis-Wollner, I.G.; et al. Effect of Creatine Monohydrate on Clinical Progression in Patients with Parkinson Disease: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2015, 313, 584–593. [CrossRef]

- Rissardo, J.P.; Caprara, A.L.F. The Role of Vitamin D in Parkinson’s Disease: Evidence from Serum Concentrations, Supplementation, and VDR Gene Polymorphisms. NeuroSci 2025, 6, 130. [CrossRef]

- Snow, B.J.; Rolfe, F.L.; Lockhart, M.M.; Frampton, C.M.; O’Sullivan, J.D.; Fung, V.; Smith, R.A.J.; Murphy, M.P.; Taylor, K.M. A Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Study to Assess the Mitochondria-Targeted Antioxidant MitoQ as a Disease-Modifying Therapy in Parkinson’s Disease. Mov Disord 2010, 25, 1670–1674. [CrossRef]

- Berven, H.; Kverneng, S.; Sheard, E.; Søgnen, M.; Af Geijerstam, S.A.; Haugarvoll, K.; Skeie, G.-O.; Dölle, C.; Tzoulis, C. NR-SAFE: A Randomized, Double-Blind Safety Trial of High Dose Nicotinamide Riboside in Parkinson’s Disease. Nat Commun 2023, 14, 7793. [CrossRef]

- Schwarzschild, M.A.; Ascherio, A.; Casaceli, C.; Curhan, G.C.; Fitzgerald, R.; Kamp, C.; Lungu, C.; Macklin, E.A.; Marek, K.; Mozaffarian, D.; et al. Effect of Urate-Elevating Inosine on Early Parkinson Disease Progression: The SURE-PD3 Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2021, 326, 926–939. [CrossRef]

- Postuma, R.B.; Lang, A.E.; Munhoz, R.P.; Charland, K.; Pelletier, A.; Moscovich, M.; Filla, L.; Zanatta, D.; Rios Romenets, S.; Altman, R.; et al. Caffeine for Treatment of Parkinson Disease: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Neurology 2012, 79, 651–658. [CrossRef]

- Volc, D.; Poewe, W.; Kutzelnigg, A.; Lührs, P.; Thun-Hohenstein, C.; Schneeberger, A.; Galabova, G.; Majbour, N.; Vaikath, N.; El-Agnaf, O.; et al. Safety and Immunogenicity of the α-Synuclein Active Immunotherapeutic PD01A in Patients with Parkinson’s Disease: A Randomised, Single-Blinded, Phase 1 Trial. Lancet Neurol 2020, 19, 591–600. [CrossRef]

- Simuni, T.; Fiske, B.; Merchant, K.; Coffey, C.S.; Klingner, E.; Caspell-Garcia, C.; Lafontant, D.-E.; Matthews, H.; Wyse, R.K.; Brundin, P.; et al. Efficacy of Nilotinib in Patients With Moderately Advanced Parkinson Disease: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Neurol 2021, 78, 312–320. [CrossRef]

- Imam, S.Z.; Trickler, W.; Kimura, S.; Binienda, Z.K.; Paule, M.G.; Slikker, W.J.; Li, S.; Clark, R.A.; Ali, S.F. Neuroprotective Efficacy of a New Brain-Penetrating C-Abl Inhibitor in a Murine Parkinson’s Disease Model. PLoS One 2013, 8, e65129. [CrossRef]

- Karuppagounder, S.S.; Wang, H.; Kelly, T.; Rush, R.; Nguyen, R.; Bisen, S.; Yamashita, Y.; Sloan, N.; Dang, B.; Sigmon, A.; et al. The C-Abl Inhibitor IkT-148009 Suppresses Neurodegeneration in Mouse Models of Heritable and Sporadic Parkinson’s Disease. Sci Transl Med 2023, 15, eabp9352. [CrossRef]

- Devos, D.; Labreuche, J.; Rascol, O.; Corvol, J.-C.; Duhamel, A.; Guyon Delannoy, P.; Poewe, W.; Compta, Y.; Pavese, N.; Růžička, E.; et al. Trial of Deferiprone in Parkinson’s Disease. N Engl J Med 2022, 387, 2045–2055. [CrossRef]

- Devos, D.; Moreau, C.; Devedjian, J.C.; Kluza, J.; Petrault, M.; Laloux, C.; Jonneaux, A.; Ryckewaert, G.; Garçon, G.; Rouaix, N.; et al. Targeting Chelatable Iron as a Therapeutic Modality in Parkinson’s Disease. Antioxid Redox Signal 2014, 21, 195–210. [CrossRef]

- Martin-Bastida, A.; Ward, R.J.; Newbould, R.; Piccini, P.; Sharp, D.; Kabba, C.; Patel, M.C.; Spino, M.; Connelly, J.; Tricta, F.; et al. Brain Iron Chelation by Deferiprone in a Phase 2 Randomised Double-Blinded Placebo Controlled Clinical Trial in Parkinson’s Disease. Sci Rep 2017, 7, 1398. [CrossRef]

- Shachar, D.B.; Kahana, N.; Kampel, V.; Warshawsky, A.; Youdim, M.B.H. Neuroprotection by a Novel Brain Permeable Iron Chelator, VK-28, against 6-Hydroxydopamine Lession in Rats. Neuropharmacology 2004, 46, 254–263. [CrossRef]

- Vijiaratnam, N.; Girges, C.; Auld, G.; McComish, R.; King, A.; Skene, S.S.; Hibbert, S.; Wong, A.; Melander, S.; Gibson, R.; et al. Exenatide Once a Week versus Placebo as a Potential Disease-Modifying Treatment for People with Parkinson’s Disease in the UK: A Phase 3, Multicentre, Double-Blind, Parallel-Group, Randomised, Placebo-Controlled Trial. Lancet 2025, 405, 627–636. [CrossRef]

- Zeissler, M.-L.; Boey, T.; Chapman, D.; Rafaloff, G.; Dominey, T.; Raphael, K.G.; Buff, S.; Pai, H.V.; King, E.; Sharpe, P.; et al. Investigating Trial Design Variability in Trials of Disease-Modifying Therapies in Parkinson’s Disease: A Scoping Review Protocol. BMJ Open 2023, 13, e071641. [CrossRef]

- NINDS Exploratory Trials in Parkinson Disease (NET-PD) FS-ZONE Investigators Pioglitazone in Early Parkinson’s Disease: A Phase 2, Multicentre, Double-Blind, Randomised Trial. Lancet Neurol 2015, 14, 795–803. [CrossRef]

- Wouters, O.J.; McKee, M.; Luyten, J. Estimated Research and Development Investment Needed to Bring a New Medicine to Market, 2009-2018. JAMA 2020, 323, 844–853. [CrossRef]

- Mahlknecht, P.; Poewe, W. Pharmacotherapy for Disease Modification in Early Parkinson’s Disease: How Early Should We Be? J Parkinsons Dis 2024, 14, S407–S421. [CrossRef]

- Stocchi, F.; Olanow, C.W. Neuroprotection in Parkinson’s Disease: Clinical Trials. Ann Neurol 2003, 53 Suppl 3, S87-97; discussion S97-99. [CrossRef]

- Kalinderi, K.; Papaliagkas, V.; Fidani, L. GLP-1 Receptor Agonists: A New Treatment in Parkinson’s Disease. Int J Mol Sci 2024, 25. [CrossRef]

- Dhruv, N.T.; Robinson Schwartz, S.; Swanson-Fischer, C.; Cho, H.J.; Corlew, R.; Jakeman, L.; Laboissonniere, L.A.; Price, R.; Sarraf, S.; Sieber, B.-A.; et al. Mapping the Developmental Path for Parkinson’s Disease Therapeutics. NPJ Parkinsons Dis 2025, 11, 313. [CrossRef]

- Boucherie, D.M.; Duarte, G.S.; Machado, T.; Faustino, P.R.; Sampaio, C.; Rascol, O.; Ferreira, J.J. Parkinson’s Disease Drug Development Since 1999: A Story of Repurposing and Relative Success. J Parkinsons Dis 2021, 11, 421–429. [CrossRef]

- Kulkarni, S.R.; Thokchom, B.; Abbigeri, M.B.; Bhavi, S.M.; Singh, S.R.; Metri, N.; Yarajarla, R.B. The Role of L-DOPA in Neurological and Neurodegenerative Complications: A Review. Mol Cell Biochem 2025, 480, 5221–5242. [CrossRef]

- Guimarães, T.G.; Parmera, J.B.; Castro, M.A.A.; Cury, R.G.; Barbosa, E.R.; Kok, F. X-Linked Levodopa-Responsive Parkinsonism-Epilepsy Syndrome: A Novel PGK1 Mutation and Literature Review. Mov Disord Clin Pract 2024, 11, 556–566. [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Zhao, C.; Li, X.; Wang, T.; Li, Y.; Cao, C.; Ding, Y.; Dong, M.; Finci, L.; Wang, J.-H.; et al. Terazosin Activates Pgk1 and Hsp90 to Promote Stress Resistance. Nat Chem Biol 2015, 11, 19–25. [CrossRef]

- Cai, R.; Zhang, Y.; Simmering, J.E.; Schultz, J.L.; Li, Y.; Fernandez-Carasa, I.; Consiglio, A.; Raya, A.; Polgreen, P.M.; Narayanan, N.S.; et al. Enhancing Glycolysis Attenuates Parkinson’s Disease Progression in Models and Clinical Databases. J Clin Invest 2019, 129, 4539–4549. [CrossRef]

- Weber, M.A.; Sivakumar, K.; Tabakovic, E.E.; Oya, M.; Aldridge, G.M.; Zhang, Q.; Simmering, J.E.; Narayanan, N.S. Glycolysis-Enhancing α(1)-Adrenergic Antagonists Modify Cognitive Symptoms Related to Parkinson’s Disease. NPJ Parkinsons Dis 2023, 9, 32. [CrossRef]

- Kokotos, A.C.; Antoniazzi, A.M.; Unda, S.R.; Ko, M.S.; Park, D.; Eliezer, D.; Kaplitt, M.G.; De Camilli, P.; Ryan, T.A. Phosphoglycerate Kinase Is a Central Leverage Point in Parkinson’s Disease-Driven Neuronal Metabolic Deficits. Sci Adv 2024, 10, eadn6016. [CrossRef]

- Schultz, J.L.; Gander, P.E.; Workman, C.D.; Boles Ponto, L.L.; Cross, S.; Nance, C.S.; Groth, C.L.; Taylor, E.B.; Ernst, S.E.; Xu, J.; et al. A Dose-Finding Study Shows Terazosin Enhanced Energy Metabolism in Neurologically Healthy Adults. J Parkinsons Dis 2025, 15, 1253–1263. [CrossRef]

- Schultz, J.L.; Brinker, A.N.; Xu, J.; Ernst, S.E.; Tayyari, F.; Rauckhorst, A.J.; Liu, L.; Uc, E.Y.; Taylor, E.B.; Simmering, J.E.; et al. A Pilot to Assess Target Engagement of Terazosin in Parkinson’s Disease. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 2022, 94, 79–83. [CrossRef]

- Lamichhane, P.; Tariq, A.; Akhtar, A.N.; Raza, M.; Lamsal, A.B.; Agrawal, A. Risk of Parkinson’s Disease among Users of Alpha-Adrenergic Receptor Antagonists: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Ann Med Surg (Lond) 2024, 86, 3409–3415. [CrossRef]

- Lang, A.E.; Espay, A.J. Disease Modification in Parkinson’s Disease: Current Approaches, Challenges, and Future Considerations. Mov Disord 2018, 33, 660–677. [CrossRef]

- Vijiaratnam, N.; Foltynie, T. How Should We Be Using Biomarkers in Trials of Disease Modification in Parkinson’s Disease? Brain 2023, 146, 4845–4869. [CrossRef]

- McFarthing, K.; Buff, S.; Rafaloff, G.; Pitzer, K.; Fiske, B.; Navangul, A.; Beissert, K.; Pilcicka, A.; Fuest, R.; Wyse, R.K.; et al. Parkinson’s Disease Drug Therapies in the Clinical Trial Pipeline: 2024 Update. J Parkinsons Dis 2024, 14, 899–912. [CrossRef]

- Fiske, B.; Klapper, K.; Schorken, Z.; Sweet-Byrnes, M. Parkinson’s Priority Therapeutic Clinical Pipeline Report 2025.

- Pitton Rissardo, J.; Fornari Caprara, A.L. Protein Aggregation and Proteostasis Failure in Neurodegenerative Diseases: Mechanisms, Structural Insights, and Therapeutic Strategies. Preprints 2025. [CrossRef]

- Wong, Y.C.; Krainc, D. α-Synuclein Toxicity in Neurodegeneration: Mechanism and Therapeutic Strategies. Nat Med 2017, 23, 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Fabbri, M.; Corvol, J.C.; Rascol, O. Disease-Modifying Therapies in Parkinson’s Disease. Neurol Clin 2025, 43, 319–340. [CrossRef]

- Han, Q.-Q.; Le, W. NLRP3 Inflammasome-Mediated Neuroinflammation and Related Mitochondrial Impairment in Parkinson’s Disease. Neurosci Bull 2023, 39, 832–844. [CrossRef]

- Yao, J.; Wang, Z.; Song, W.; Zhang, Y. Targeting NLRP3 Inflammasome for Neurodegenerative Disorders. Mol Psychiatry 2023, 28, 4512–4527. [CrossRef]

- Athauda, D.; Foltynie, T. Insulin Resistance and Parkinson’s Disease: A New Target for Disease Modification? Prog Neurobiol 2016, 145–146, 98–120. [CrossRef]

- Werner, M.H.; Olanow, C.W. Parkinson’s Disease Modification Through Abl Kinase Inhibition: An Opportunity. Mov Disord 2022, 37, 6–15. [CrossRef]

- Barker, R.A.; Lao-Kaim, N.P.; Guzman, N.V.; Athauda, D.; Bjartmarz, H.; Björklund, A.; Church, A.; Cutting, E.; Daft, D.; Dayal, V.; et al. The TransEuro Open-Label Trial of Human Fetal Ventral Mesencephalic Transplantation in Patients with Moderate Parkinson’s Disease. Nat Biotechnol 2025. [CrossRef]

- Barker, R.A.; Parmar, M.; Studer, L.; Takahashi, J. Human Trials of Stem Cell-Derived Dopamine Neurons for Parkinson’s Disease: Dawn of a New Era. Cell Stem Cell 2017, 21, 569–573. [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, J. Stem Cell Therapy for Parkinson’s Disease. Expert Rev Neurother 2007, 7, 667–675. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.T.; John, N.; Delic, V.; Ikeda-Lee, K.; Kim, A.; Weihofen, A.; Swayze, E.E.; Kordasiewicz, H.B.; West, A.B.; Volpicelli-Daley, L.A. LRRK2 Antisense Oligonucleotides Ameliorate α-Synuclein Inclusion Formation in a Parkinson’s Disease Mouse Model. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids 2017, 8, 508–519. [CrossRef]

- Christine, C.W.; Starr, P.A.; Larson, P.S.; Eberling, J.L.; Jagust, W.J.; Hawkins, R.A.; VanBrocklin, H.F.; Wright, J.F.; Bankiewicz, K.S.; Aminoff, M.J. Safety and Tolerability of Putaminal AADC Gene Therapy for Parkinson Disease. Neurology 2009, 73, 1662–1669. [CrossRef]

- Bartus, R.T. Gene Therapy for Parkinson’s Disease: A Decade of Progress Supported by Posthumous Contributions from Volunteer Subjects. Neural Regen Res 2015, 10, 1586–1588. [CrossRef]

- Mendell, J.R.; Al-Zaidy, S.A.; Rodino-Klapac, L.R.; Goodspeed, K.; Gray, S.J.; Kay, C.N.; Boye, S.L.; Boye, S.E.; George, L.A.; Salabarria, S.; et al. Current Clinical Applications of In Vivo Gene Therapy with AAVs. Mol Ther 2021, 29, 464–488. [CrossRef]

- Kordower, J.H.; Bjorklund, A. Trophic Factor Gene Therapy for Parkinson’s Disease. Mov Disord 2013, 28, 96–109. [CrossRef]

- Balestrino, R.; Schapira, A.H.V. Glucocerebrosidase and Parkinson Disease: Molecular, Clinical, and Therapeutic Implications. Neuroscientist 2018, 24, 540–559. [CrossRef]

- LeWitt, P.A.; Rezai, A.R.; Leehey, M.A.; Ojemann, S.G.; Flaherty, A.W.; Eskandar, E.N.; Kostyk, S.K.; Thomas, K.; Sarkar, A.; Siddiqui, M.S.; et al. AAV2-GAD Gene Therapy for Advanced Parkinson’s Disease: A Double-Blind, Sham-Surgery Controlled, Randomised Trial. Lancet Neurol 2011, 10, 309–319. [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.; Kim, H.; Jedrychowski, M.P.; Bakiasi, G.; Park, J.; Kruskop, J.; Choi, Y.; Kwak, S.S.; Quinti, L.; Kim, D.Y.; et al. Irisin Reduces Amyloid-β by Inducing the Release of Neprilysin from Astrocytes Following Downregulation of ERK-STAT3 Signaling. Neuron 2023, 111, 3619-3633.e8. [CrossRef]

- Mullin, S.; Stokholm, M.G.; Hughes, D.; Mehta, A.; Parbo, P.; Hinz, R.; Pavese, N.; Brooks, D.J.; Schapira, A.H.V. Brain Microglial Activation Increased in Glucocerebrosidase (GBA) Mutation Carriers without Parkinson’s Disease. Mov Disord 2021, 36, 774–779. [CrossRef]

- Menozzi, E.; Schapira, A.H.V. Prospects for Disease Slowing in Parkinson Disease. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 2025, 65, 237–258. [CrossRef]

- Schiffmann, R.; Cox, T.M.; Dedieu, J.-F.; Gaemers, S.J.M.; Hennermann, J.B.; Ida, H.; Mengel, E.; Minini, P.; Mistry, P.; Musholt, P.B.; et al. Venglustat Combined with Imiglucerase for Neurological Disease in Adults with Gaucher Disease Type 3: The LEAP Trial. Brain 2023, 146, 461–474. [CrossRef]

- Kaplitt, M.G.; Feigin, A.; Tang, C.; Fitzsimons, H.L.; Mattis, P.; Lawlor, P.A.; Bland, R.J.; Young, D.; Strybing, K.; Eidelberg, D.; et al. Safety and Tolerability of Gene Therapy with an Adeno-Associated Virus (AAV) Borne GAD Gene for Parkinson’s Disease: An Open Label, Phase I Trial. Lancet 2007, 369, 2097–2105. [CrossRef]

- Niethammer, M.; Tang, C.C.; LeWitt, P.A.; Rezai, A.R.; Leehey, M.A.; Ojemann, S.G.; Flaherty, A.W.; Eskandar, E.N.; Kostyk, S.K.; Sarkar, A.; et al. Long-Term Follow-up of a Randomized AAV2-GAD Gene Therapy Trial for Parkinson’s Disease. JCI Insight 2017, 2, e90133. [CrossRef]

- Niethammer, M.; Tang, C.C.; Vo, A.; Nguyen, N.; Spetsieris, P.; Dhawan, V.; Ma, Y.; Small, M.; Feigin, A.; During, M.J.; et al. Gene Therapy Reduces Parkinson’s Disease Symptoms by Reorganizing Functional Brain Connectivity. Sci Transl Med 2018, 10, eaau0713. [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.; Aldawood, Y.O.; Kazi, N.; Sideeque, S.; Ansari, N.; Mohammed, H.; Byroju, V.V.; Caprara, A.L.F.; Rissardo, J.P. Brain Structural and Functional Alteration in Movement Disorders: A Narrative Review of Markers and Their Dynamic Changes. NeuroMarkers 2025, 100130. [CrossRef]

- Marks, W.J.J.; Bartus, R.T.; Siffert, J.; Davis, C.S.; Lozano, A.; Boulis, N.; Vitek, J.; Stacy, M.; Turner, D.; Verhagen, L.; et al. Gene Delivery of AAV2-Neurturin for Parkinson’s Disease: A Double-Blind, Randomised, Controlled Trial. Lancet Neurol 2010, 9, 1164–1172. [CrossRef]

- Warren Olanow, C.; Bartus, R.T.; Baumann, T.L.; Factor, S.; Boulis, N.; Stacy, M.; Turner, D.A.; Marks, W.; Larson, P.; Starr, P.A.; et al. Gene Delivery of Neurturin to Putamen and Substantia Nigra in Parkinson Disease: A Double-Blind, Randomized, Controlled Trial. Ann Neurol 2015, 78, 248–257. [CrossRef]

- Witt, J.; Marks, W.J.J. An Update on Gene Therapy in Parkinson’s Disease. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep 2011, 11, 362–370. [CrossRef]

- Sehara, Y.; Fujimoto, K.-I.; Ikeguchi, K.; Katakai, Y.; Ono, F.; Takino, N.; Ito, M.; Ozawa, K.; Muramatsu, S.-I. Persistent Expression of Dopamine-Synthesizing Enzymes 15 Years After Gene Transfer in a Primate Model of Parkinson’s Disease. Hum Gene Ther Clin Dev 2017, 28, 74–79. [CrossRef]

- Bankiewicz, K.S.; Forsayeth, J.; Eberling, J.L.; Sanchez-Pernaute, R.; Pivirotto, P.; Bringas, J.; Herscovitch, P.; Carson, R.E.; Eckelman, W.; Reutter, B.; et al. Long-Term Clinical Improvement in MPTP-Lesioned Primates after Gene Therapy with AAV-hAADC. Mol Ther 2006, 14, 564–570. [CrossRef]

- Kojima, K.; Nakajima, T.; Taga, N.; Miyauchi, A.; Kato, M.; Matsumoto, A.; Ikeda, T.; Nakamura, K.; Kubota, T.; Mizukami, H.; et al. Gene Therapy Improves Motor and Mental Function of Aromatic L-Amino Acid Decarboxylase Deficiency. Brain 2019, 142, 322–333. [CrossRef]

- Hwu, W.-L.; Muramatsu, S.; Tseng, S.-H.; Tzen, K.-Y.; Lee, N.-C.; Chien, Y.-H.; Snyder, R.O.; Byrne, B.J.; Tai, C.-H.; Wu, R.-M. Gene Therapy for Aromatic L-Amino Acid Decarboxylase Deficiency. Sci Transl Med 2012, 4, 134ra61. [CrossRef]

- Christine, C.W.; Bankiewicz, K.S.; Van Laar, A.D.; Richardson, R.M.; Ravina, B.; Kells, A.P.; Boot, B.; Martin, A.J.; Nutt, J.; Thompson, M.E.; et al. Magnetic Resonance Imaging-Guided Phase 1 Trial of Putaminal AADC Gene Therapy for Parkinson’s Disease. Ann Neurol 2019, 85, 704–714. [CrossRef]

- Pitton Rissardo, J.; Fornari Caprara, A.L. Disease-Modifying Trials in Parkinson’s Disease: Challenges, Lessons, and Future Directions. Preprints 2025. [CrossRef]

- Fabbri, M.; Rascol, O.; Foltynie, T.; Carroll, C.; Postuma, R.B.; Porcher, R.; Corvol, J.C. Advantages and Challenges of Platform Trials for Disease Modifying Therapies in Parkinson’s Disease. Mov Disord 2024, 39, 1468–1477. [CrossRef]

- Simuni, T.; Coffey, C.; Siderowf, A.; Tanner, C.; Marek, K.; Brumm, M.; Investigators, P.; Chowdhury, S.; Sherer, T.; Kopil, C. Path To Prevention (P2P) Therapeutics Platform Trial in Biomarker Defined Prodromal Parkinson’s Disease: Study Design. Mov Disord 2023, 38, S50–S51.

- Rissardo, J.P.; Fornari Caprara, A.L. Alpha-Synuclein Seed Amplification Assays in Parkinson’s Disease: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis. Clin Pract 2025, 15. [CrossRef]

- Parnetti, L.; Bellomo, G.; Gaetani, L. Unlocking the Full Clinical Potential of the α-Synuclein Seed Amplification Assay. Lancet Neurol 2025, 24, 559–561. [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, C.C.; Ushakova, A.; Alves, G.; Tysnes, O.-B.; Blennow, K.; Zetterberg, H.; Maple-Grødem, J.; Lange, J. Serum Neurofilament Light at Diagnosis: A Prognostic Indicator for Accelerated Disease Progression in Parkinson’s Disease. NPJ Parkinsons Dis 2024, 10, 162. [CrossRef]

- Williams-Gray, C.H.; Wijeyekoon, R.; Yarnall, A.J.; Lawson, R.A.; Breen, D.P.; Evans, J.R.; Cummins, G.A.; Duncan, G.W.; Khoo, T.K.; Burn, D.J.; et al. Serum Immune Markers and Disease Progression in an Incident Parkinson’s Disease Cohort (ICICLE-PD). Mov Disord 2016, 31, 995–1003. [CrossRef]

- Pardoel, S.; Kofman, J.; Nantel, J.; Lemaire, E.D. Wearable-Sensor-Based Detection and Prediction of Freezing of Gait in Parkinson’s Disease: A Review. Sensors (Basel) 2019, 19. [CrossRef]

- Lipsmeier, F.; Taylor, K.I.; Postuma, R.B.; Volkova-Volkmar, E.; Kilchenmann, T.; Mollenhauer, B.; Bamdadian, A.; Popp, W.L.; Cheng, W.-Y.; Zhang, Y.-P.; et al. Reliability and Validity of the Roche PD Mobile Application for Remote Monitoring of Early Parkinson’s Disease. Sci Rep 2022, 12, 12081. [CrossRef]

- Wayland, R.; Meyer, R.; Tang, K. Speech Markers of Parkinson’s Disease: Phonological Features and Acoustic Measures. Brain Sci 2025, 15. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, R.; Gulati, A.; Chopra, K. Era of Surrogate Endpoints and Accelerated Approvals: A Comprehensive Review on Applicability, Uncertainties, and Challenges from Regulatory, Payer, and Patient Perspectives. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 2025, 81, 605–623. [CrossRef]

- Getz, K.A.; Campo, R.A. New Benchmarks Characterizing Growth in Protocol Design Complexity. Ther Innov Regul Sci 2018, 52, 22–28. [CrossRef]

- Wyse, R.K.; Isaacs, T.; Barker, R.A.; Cookson, M.R.; Dawson, T.M.; Devos, D.; Dexter, D.T.; Duffen, J.; Federoff, H.; Fiske, B.; et al. Twelve Years of Drug Prioritization to Help Accelerate Disease Modification Trials in Parkinson’s Disease: The International Linked Clinical Trials Initiative. J Parkinsons Dis 2024, 14, 657–666. [CrossRef]

| Class | Medication | MOA | Possible failure cause | Note | NCT/ References |

| Adenosine A₂A receptors | Caffeine | Non-selective adenosine receptor antagonist | Epidemiological signal not replicated in RCTs | Observational benefit not confirmed | NCT01738178 Costa et al. [12] |

| Istradefylline | Selective A₂A receptor antagonist | Symptomatic benefit only; no DME | Approved for motor fluctuations, not progression | NCT00199433 Torti et al. [13] |

|

| Anti-αSyn monoclonal antibody | Cinpanemab (BIIB054) | Binds the N-terminal region of αSyn | Lack of target engagement or insufficient CNS penetration | SPARK (Phase II) stopped for lack of efficacy | NCT03318523 Lang et al. [14] |

| Prasinezumab (RO7046015/PRX002) | Targets the C-terminal region of αSyn | Possible late intervention; limited clinical effect | PASADENA did not meet primary endpoint (signals on Part III; ongoing OLE); PADOVA primary negative | NCT03100149 Pagano et al. [15] |

|

| Coenzyme Q10 (CoQ10) | Mitochondrial electron transport cofactor; antioxidant | Poor CNS bioavailability; inadequate oxidative stress modulation | QE3 stopped for futility; no benefit | NCT00740714 Jiménez-Jiménez et al. [16] |

|

| Creatine | Cellular energy buffer (phosphocreatine system) | No measurable neuroprotection | NET-PD LS-1 terminated for futility | NCT00449865 Attia et al. [17] |

|

| Calcium channel blocker | Isradipine | Dihydropyridine L-type Ca²⁺ channel blocker | Dose limited by hypotension; insufficient nigral protection | Phase III (STEADY-PD III) negative for slowing progression | NCT02168842 Lin et al. [18] |

| Dopamine agonists | Pramipexole | D2/D3 receptor agonist | Delayed-start design; no biomarker confirmation | Phase III (PROUD) negative for slowing progression | NCT00321854 Dooley et al. [19] |

| Ropinirole | D2/D3 receptor agonist | Symptomatic improvement appears slower; no biomarker confirmation | REAL-PD trial negative; no evidence of neuroprotection | NCT00243855 Zhu et al. [20] |

|

| Rotigotine | Non-ergoline dopamine agonist | Symptomatic improvement appears slower; no biomarker confirmation | No significant difference in progression; exploratory analyses inconclusive | NCT00474058 Rajendran et al. [21] |

|

| Gene therapy | CERE-120 (AAV2-neurturin) | Gene therapy delivering neurturin | Limited axonal transport; poor distribution | Phase 2 trials failed primary endpoint; post-mortem shows limited expression | NCT00985517 Hickey et al. [22] |

| Glutamate antagonists | Riluzole | Glutamate release inhibitor | Insufficient effect on excitotoxicity | Small trials negative; no large confirmatory study | NCT00013624 Jankovic et al. [23] |

| MAO-B inhibitors | Selegiline / Rasagiline | Irreversible MAO-B inhibition (dopamine metabolism) | Symptomatic only; delayed-start designs inconclusive | ADAGIO failed to confirm DME | NCT00256204 Schapira et al. [24] |

| PPAR-γ agonists | Pioglitazone | PPAR-γ agonist (metabolic/inflammatory modulation) | Weak CNS penetration; insufficient anti-inflammatory effect | Phase II futility trial: unlikely to modify progression | NCT01280123 Chen et al. [25] |

| Statins | Simvastatin | HMG-CoA reductase inhibitor; pleiotropic anti-inflammatory effect | Observational signal not replicated; possible off-target toxicity | PD STAT trial negative | NCT02787590 Yan et al. [26] |

| Tyrosine kinase inhibitor | Nilotinib | c-Abl inhibitor (proteostasis/ autophagy) | Biomarker changes without clinical benefit | Multicenter RCT: no efficacy; biomarker shifts without clinical benefit | NCT03205488 Xie et al. [27] |

| Urate precursor | Inosine | Antioxidant hypothesis | No clinical benefit despite biomarker elevation | SURE-PD3: no clinical benefit | NCT02642393 Basile et al. [28] |

| Medication | Mechanistic rationale in PD | Preclinical evidence | Epidemiological evidence | NCT |

| Ambroxol | Chaperone for GCase; ↑ lysosomal function; ↓ αSyn aggregation | ↑ GCase activity & ↓ αSyn pathology in GBA-mutant PD mouse models | Observational studies suggest benefit | NCT06193421; NCT05830396; NCT05778617; NCT05287503; NCT02941822; NCT02914366 |

| Allopregnanolone | ↑ GABAergic signaling & neurogenesis; ↓ DA neuronal loss & mitochondrial dysfunction | ↑ DA neuron survival; ↓ inflammation in toxin-induced PD models | Limited population data | NCT06263010 |

| Carvedilol | β-adrenergic blockade can ↓ ROS & inflammation | ↓ DA neuronal loss & oxidative markers in MPTP mouse models | β-blocker use linked to lower PD incidence in some cohorts | NCT03775096 |

| Cilostazol | PDE-3 inhibition ↑ cAMP, ↑ cerebral perfusion, and ↓ apoptosis in DA neurons | ↑ DA neuron survival & motor function in 6-OHDA rat models | Stroke prevention cohorts suggest ↓ PD risk with PDE inhibitors | NCT06612593 |

| Doxycycline | ↓ microglial activation & αSyn oligomerization | ↓ αSyn oligomerization and inflammation in transgenic PD models | Antibiotic exposure studies show mixed associations with PD risk | NCT05492019 |

| DPP-4 inhibitors (sitagliptin, vildagliptin) | ↑ GLP-1 signaling, ↑ insulin sensitivity, ↓ inflammation | ↑ motor function & ↓ DA loss in diabetic PD models | Diabetes cohorts suggest GLP-1 agonists ↓ PD incidence | NCT06263673; NCT06951334 |

| Febuxostat | ↓ ROS & UA imbalance, ↓ oxidative stress in DA neurons | ↓ ROS and preserved DA neurons in rotenone-induced PD models | ↑ UA associated with ↓ PD risk | NCT07170475 |

| Fexofenadine | ↓ inflammation & glial activation | ↓ microglial activation and ROS in PD rodent models | Antihistamine use linked to ↓ PD risk in populational studies | NCT06785298 |

| Gemfibrozil | PPAR-α activation ↑ lipid metabolism & mitochondrial function | ↓ inflammation & ↑ lipid metabolism in PD models | Lipid-lowering drugs show mixed associations with PD risk | NCT05931484 |

| Hydroxychloroquine | Modulates autophagy and lysosomal clearance of misfolded proteins, potentially ↓ αSyn burden | ↑ clearance of misfolded proteins and ↓ αSyn burden in vitro | Limited data; autoimmune cohorts show variable PD risk | NCT06816810 |

| Lithium | GSK-3β inhibition ↑ neurotrophic signaling & autophagy | ↑ autophagy & DA neuron survival in PD models | Bipolar disorder cohorts suggest lithium may ↓ PD risk | NCT06592014; NCT06339034; NCT06099886; NCT04273932 |

| Metformin | AMPK activation ↑ mitochondrial bioenergetics & ↓ ROS | ↓ ROS & ↑ motor function in PD rodent models | Diabetes cohorts show metformin use linked to ↓ PD risk | NCT07229651, NCT07055958 |

| Montelukast | ↓ inflammation & BBB disruption in PD | ↓ inflammation; preserve DA neurons in PD models | Asthma cohorts suggest leukotriene antagonists may reduce PD risk | NCT06113640 |

| Nicotinamide riboside | NAD⁺ precursor ↑ mitochondrial function & sirtuin activity | ↑ neuronal survival & ROS in PD models | Limited epidemiological data | NCT05589766; NCT05546567; NCT05344404; NCT04044131; NCT03816020; NCT03568968 |

| Sargramostim | GM-CSF modulates microglial phenotype toward neuroprotection | ↑ neuroprotective microglia & ↓ DA loss in PD models | No large-scale epidemiological data | NCT05677633; NCT03790670; NCT01882010 |

| Semaglutide | ↓ inflammation & ROS, supporting DA neuron survival | ↑ DA neuron survival & motor function in PD models | Diabetes cohorts show GLP-1 agonists associated with ↓ PD risk | NCT03659682 |

| Telmisartan | Angiotensin II receptor blockade and PPAR-γ activation ↓ inflammation & ROS in PD | ↓ROS and ↑ mitochondrial function in PD models | Hypertension cohorts suggest ARBs may lower PD risk | NCT07207057 |

| Terazosin | Activates PGK1, ↑ glycolysis & ATP production, improving neuronal energy metabolism in PD | ↑ neuronal energy metabolism & survival in PD models | Observational studies show α1-blockers linked to reduced PD risk | NCT07207057; NCT05855577; NCT05109364; NCT04386317; NCT03905811 |

| Tocotrienols | Potent antioxidant properties ↓ lipid peroxidation & ROS in DA neurons | Protected DA neurons from oxidative damage in PD models | Vitamin E intake inversely associated with PD risk | NCT04491383; NCT01923584 |

| Vinpocetine | PDE inhibition ↑ cerebral blood flow and ↓ inflammation, supporting neuronal metabolism | ↓ inflammation & ↑ motor function in PD models | Limited population data | NCT07229664 |

| Mechanism | Drug | Key Feature | Key Challenges | Development Stage |

| Local production of dopamine | TH | Rate-limiting enzyme for dopamine production | Invasive surgery; limited non-motor benefit | Phase I/II trials |

| GCH | Cofactor synthesis for TH | Phase I/II trials | ||

| AADC | Approved for AADC deficiency; tested in PD | Phase I/II trials | ||

| Protection of dopaminergic neurons | GDNF | Neurotrophic factor delivery | Advanced disease limits efficacy | Phase II (negative) |

| Neurturin (CERE-120) | Dual-site infusion (putamen + SN) | Poor axonal transport | Phase II (negative) | |

| GBA | Targets glucocerebrosidase activity | Biomarker validation | Early-phase trials | |

| Suppression of STN hyperactivity | GAD-65 and GAD67 | Boosts GABA synthesis for circuit modulation | Modest benefit vs DBS | Phase I/II trials |

| Reduction of αSyn | Irisin | Stimulates neprilysin release | Translational gap | Preclinical |

| Neprilysin | Direct proteolytic degradation of aggregates | Off-target effects | Preclinical |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.