Submitted:

26 December 2025

Posted:

29 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Patients and Methods

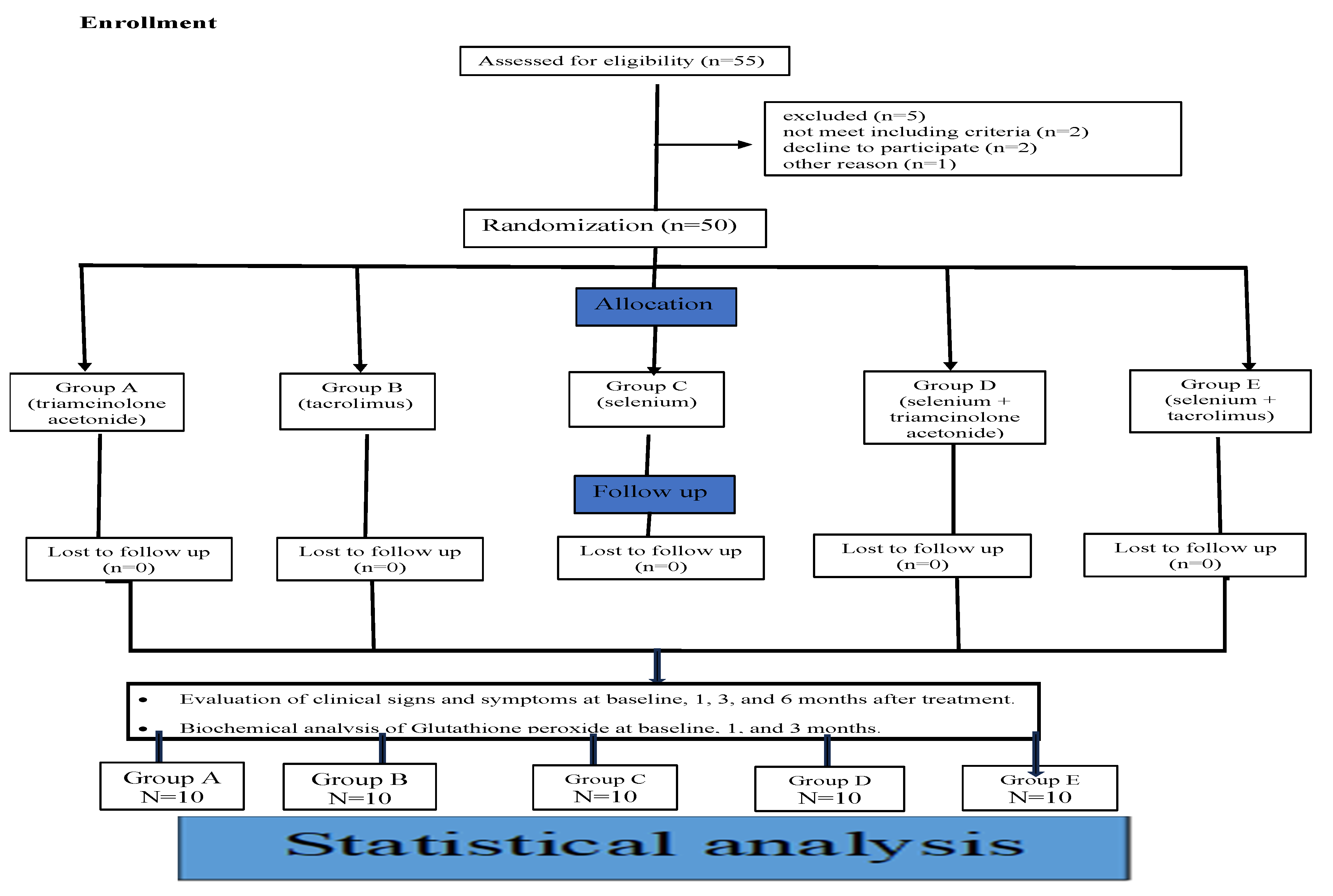

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Patients:

2.2.1. Inclusion Criteria

2.2.2. Exclusion Criteria

2.3. Ethical Considerations

2.4. Sample Size Calculation and Power Analysis

2.5. Grouping and Randomization

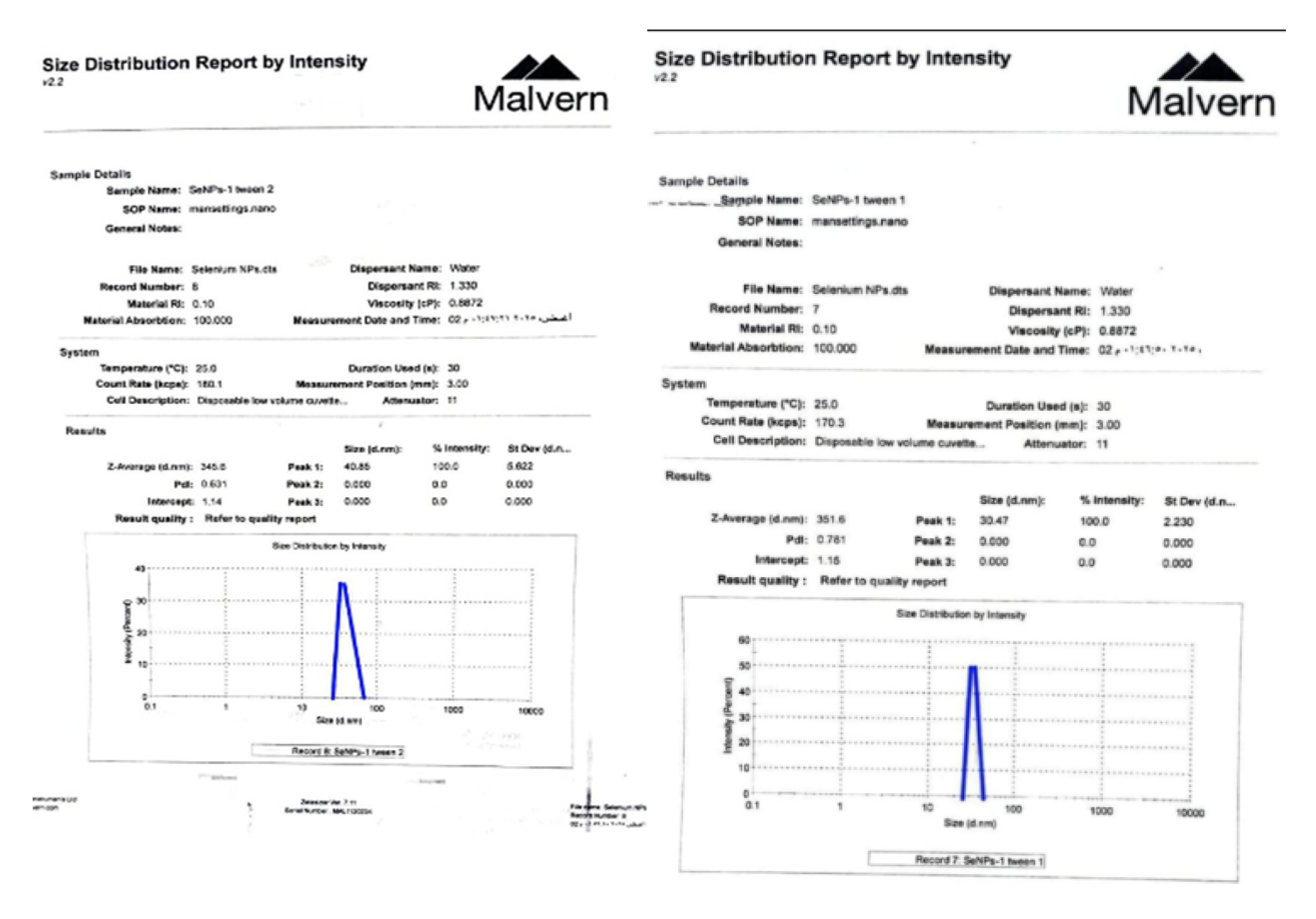

2.6. Materials

2.6.1. Therapeutic Agents:

2.7.1. Clinical Evaluation:

- Primary Clinical evaluation:

- Secondary clinical evaluation:

2.7.2. Saliva Sampling

2.7.3. Biochemical Evaluation:

2.8. Statistical Analysis

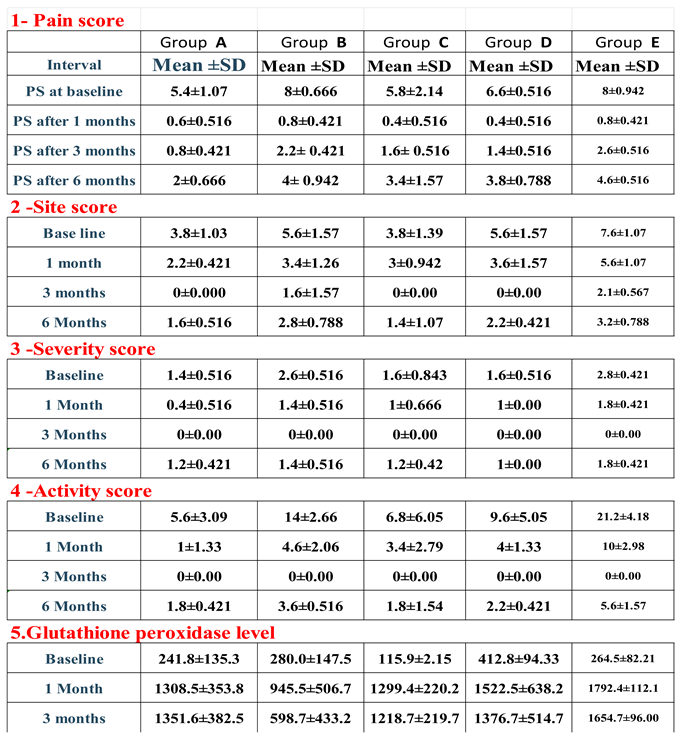

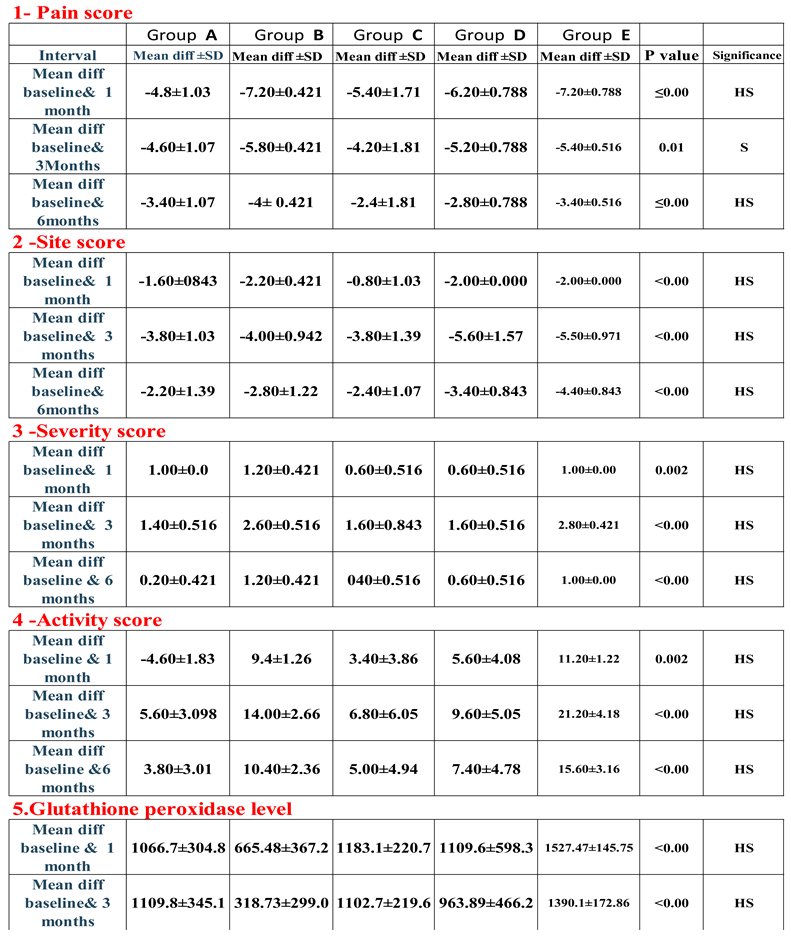

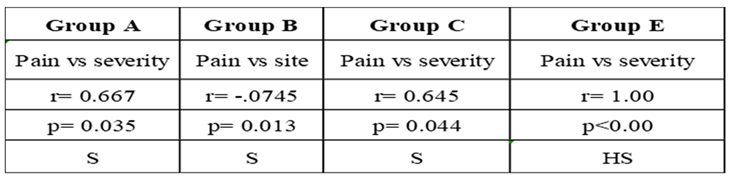

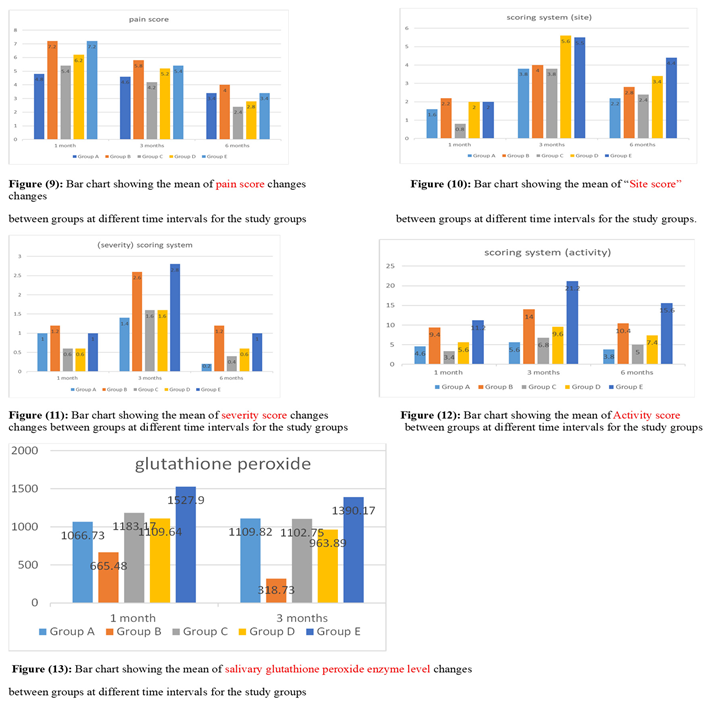

3. Results: Demographic Data

|

4. Discussion:

5. Conclusions

- Selenium nanoparticle gel proved to be a highly effective alternative treatment for OLP, offering better results than standard methods by easing pain, providing longer-lasting effects, speeding up lesion healing, and reducing their size and severity.

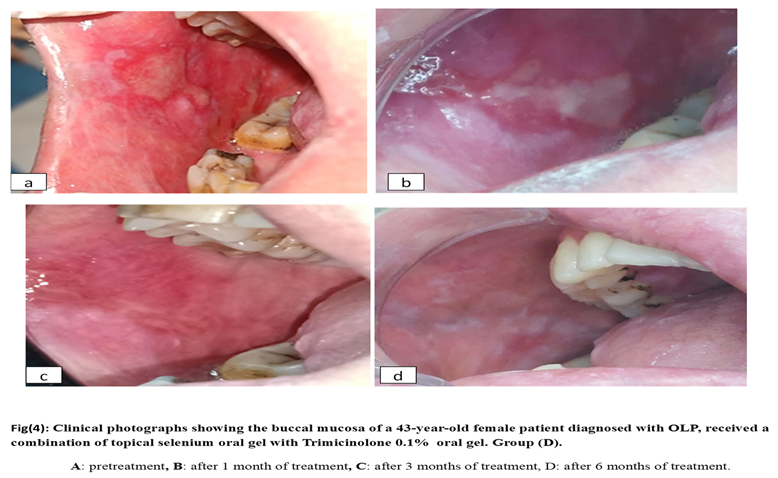

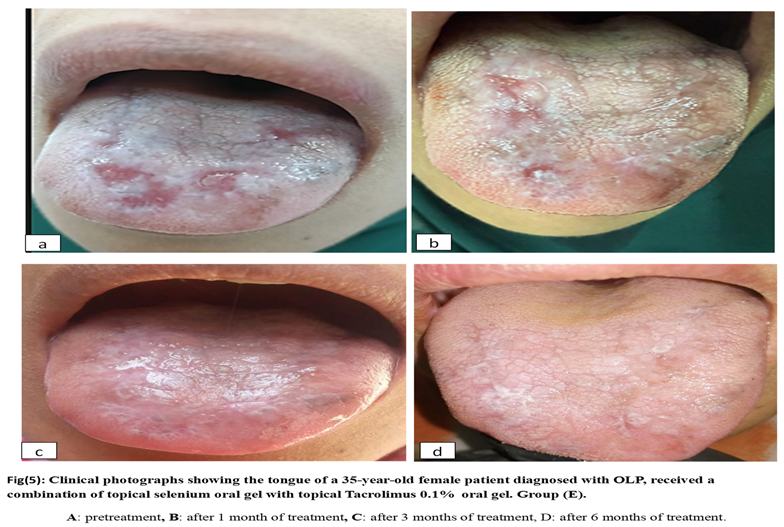

- Combination therapy, whether Selenium nanoparticles with triamcinolone acetonide or Selenium nanoparticles with tacrolimus, is more effective than monotherapy, considered a promising approach for managing advanced, resistant OLP cases, presenting a practical and cost-efficient way to improve outcomes for OLP patients while lowering the risk of drug resistance.

- Salivary glutathione peroxide appears to be a promising non-invasive biomarker for monitoring and treating OLP.

Limitation

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier

| 1 | DEVA HOLDİNG A.Ş. gizli içine uygulanır |

References

- Munde, AD; Karle, RR; Wankhede, PK; Shaikh, SS; Kulkarni, M. Demographic and clinical profile of oral lichen planus: A retrospective study. Contemp Clin Dent. 2013, 4(2), 181–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Payeras, MRCK; Figueiredo, MA; Salum, FG. Oral lichen planus: focus on etiopathogenesis. Arch Oral Biol. 2013, 58, 1057–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- kotb, s.; AlAziz, Y.; AbdRabbouh, A.; Fouad, M.; Sayed, D.; Shoukheba, M. Pathophysiological association between oxidative stress and oral lichen planus and its future implication on treatment” review article. International Journal of Research and Scientific Innovation 2024, XI(XI), 449–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoukheba, M.; Ali, S. Silymarin: adjunctive treatment in hepatitis C-associated oral lichen planus. Egyptian Dental Journal 2018, 64(2), 1203–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nosratzehi, Tahereh; Kadeh, Hamideh1; Mohsenzadeh, Hedyeh2. Demographic and clinical profile of oral lichen planus: A retrospective study. Journal of Medical Society 2023, 37(2), 89–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lillig, CH; Berndt, C. Cellular functions of glutathione. Biochim Biophys Acta 2013, 1830(5), 3137–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amirchaghmaghi, M; Delavarian, Z; Iranshahi, M; Shakeri, MT; Mosannen MozafariP; Mohammadpour, AH; et al. A randomized placebo-controlled double Blind Clinical Trial of Quercetin for treatment of oral Lichen Planus. J Dent Res Dent Clin Dent Prospects 2015, 9(1), 23–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotb, Shimaa; El-Din, Barra A.; Shehata, Rofaida R; Hosny, Amal M.; Fouad, Mohamed. The efficacy of topically applied curcumin 1% as an alternative or complementary to triamcinolone acetonate in treatment of oral lichen planus (randomized control trial). Tanta Dental Journal 2025, 22(1), 112–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalkoo, AH; Rajput, D. Evaluation of efficacy of tacrolimus 0.1% and trimicinolone acetonide 0.1% in the management of symptomatic oral lichen planus. international journal of contemporary Medical Research 2022, 9(8), H8–H12. [Google Scholar]

- Hettiarachchi, P.V.K.S.; Hettiarachchi, R.M.; Jayasingh, R.D.; Sitheeque, M. Comparison of topical tacrolimus and clobetasol in the management of symptomatic oral lichen planus: A double-blinded, randomized clinical trial in Sri Lanka. J. Invest. Clin. Dent. 2016, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branca, J.J.V.; Gulisano, M.; Pacini, A. Protective Roles of Zinc and Selenium Against Oxidative Stress in Brain Endothelial Cells Under Shear Stress. Antioxidants 2025, 14, 451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Husain, S; Sultan, RMS; Saxena, K; Bano, F; Goyal, R; Chopra, S; et al. Nano Selenium: A Promising Solution for Infectious Diseases - Current Status and Future Prospects. Curr Pharm Des. 2025, 31(35), 2795–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, JM; Garon, E; Wong, DT. Salivary diagnostics. Orthodontics & craniofacial research 2009, 12(3), 206–11. [Google Scholar]

- World Medical Association. World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA 2013, 27;310(20), 2191–4. [Google Scholar]

- Tawfeek, H; Abdellatif DAAH; Abd Elaleem Elnashar, J; Abdelaleem, Y; Fathalla, D. Transfersomal gel nanocarriers for enhancement the permeation of lornoxicam. J Drug Deliv Sci Technol. 2020, 56, 101540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajeshkumar, S; Tharani, M; Sivaperumal, P; Lakshmi, T. Green Synthesis of Selenium Nanoparticles Using Black Tea (Camellia Sinensis) And Its Antioxidant and Antimicrobial Activity. J Complement Med Res. 2020, 11(5), 75–82. [Google Scholar]

- Boroumand, S; Safari, M; Shaabani, E; Shirzad, M; Faridi - Majidi, R. Selenium nanoparticles: synthesis, characterization and study of their cytotoxicity, antioxidant and antibacterial activity. Materials Research Express 2019, 12;6(8), 0850d8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chainani-Wu, N.; Silverman, S.; Reingold, A.; Bostrom, A.; Lozada-Nur, F.; Weintraub, J. Validation of instruments to measure the symptoms and signs of oral lichen planus. Oral Surg, Ora lMed., Oral Pathol, Oral Radiol and Endodontol 2008, 105;1, 51–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malhotra AK, Khaitan BK, Sethuraman G. Sharma VK. Betamethasone oral mini-pulse therapy compared with topical triamcinolone acetonide (01%) paste in oral lichen planus: a randomized comparative study. J Am Acad Dermatol 2008, 58.596–602.

- Escudier, M; Ahmed, N; Shirlaw, P; Setterfield, J; Tappuni, A; Black, M.M; et al. A scoring system for mucosal disease severity with special reference to oral lichen planus. Br J Dermatol 2007, 157, 765–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tvarijonaviciute, A.; Aznar-Cayuela, C.; Rubio, C. P.; Ceron, J. J.; López Jornet, P. Evaluation of salivary oxidate stress biomarkers, nitric oxide and C-reactive protein in patients with oral lichen planus and burning mouth syndrome. Journal of Oral Pathology & Medicine 2017, 46, 387–92. [Google Scholar]

- Rezazadeh, F; Mahdavi, D; Fassihi, N; Sedarat, H; Tayebi Khorami, E; Tabesh, A. Evaluation of the salivary level of glutathione reductase, catalase and free thiol in patients with oral lichen planus. BMC Oral Health 2023, 9;23(1), 547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merkow, RP; Kaji, AH; Itani, KMF. The CONSORT Framework. JAMA Surg. 2021, 1;156(9), 877–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munde, AD; Karle, RR; Wankhede, PK; Shaikh, SS; Kulkurni, M. Demographic and clinical profile of oral lichen planus: A retrospective study. Contemp Clin Dent. 2013, 4(2), 181–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, S; Jawanda, MK. Oral Lichen Planus: An Update on Etiology, Pathogenesis, Clinical Presentation, Diagnosis and Management. Indian J Dermatol 2015, 60(3), 222–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youssef, M. I.; Darwish, Z.; Fahmy, R.; Sayed, N. M. E. The effect of topically applied hyaluronic acid gel versus topical corticosteroid in the treatment of erosive oral lichen planus. Alexandria Dental Journal 2019, 44(1), 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorouhi, F; Solhpour, A; Beitollahi, JM; Afshar, S; Davari, P; Hashemi, P; et al. Randomized trial of pimecrolimus cream versus triamcinolone acetonide paste in the treatment of oral lichen planus. J Am Acad Dermatol 2007, 57(5), 806–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arunkumar, S; Kalappanavar, AN; Annigeri, RG; Kalappa, SG. Relative efficacy of pimecrolimus cream and triamcinolone acetonide paste in the treatment of symptomatic oral lichen planus. Indian J Dent. 2015, 6, 14–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoukheba, MY; Ali, SA. Silymarin: Adjunctive Treatment in Hepatitis C-Associated Oral Lichen Planus. Egyptian Dental Journal. 2018, 1;64, 2- 1203-13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serafini, G; De Biase, A; Lamazza, L; Mazzucchi, G; Lollobrigida, M. Efficacy of Topical Treatments for the Management of Symptomatic Oral Lichen Planus: A Systematic Review. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2023, 10;20(2), 1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Resende, JP; Chaves, MD; Aarestrup, FM; Aarestrup, BV; Olate, S; Netto, HD. Oral lichen planus treated with tacrolimus 0.1%. J Clin Exp Med 2013, 6, 917–21. [Google Scholar]

- Utz, S.; Suter, V.G.A.; Cazzaniga, S.; Borradori, L.; Feldmeyer, L. Outcome and long-term treatment protocol for topical tacrolimus in oral lichen planus. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2022, 36, 2459–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qataya, P.O.; Elsayed, N.M.; Elguindy, N.M.; Ahmed Hafiz, M.; Samy, W.M. Selenium: A sole treatment for erosive oral lichen planus (Randomized controlled clinical trial). Oral Dis. 2020, 26, 789–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belal, MH. Management of symptomatic erosive-ulcerative lesions of oral lichen planus in an adult Egyptian population using Selenium-ACE combined with topical corticosteroids plus antifungal agent. Contemp Clin Dent. 2015, 6(4), 454–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirzaiy, M; Salehian, MA; Dalirsani, Z. Salivary Antioxidants Levels in Patients with Oral Lichen Planus. Indian J Dermatol 2022, 67(6), 651–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y; Mao, C; Zhu, J; Yang, W; Wang, Y; Yu, W; et al. Comparing the efficacy of topical interventions for pain management in oral lichen planus: a time-stratified bayesian network analysis of randomized controlled trials. BMC Oral Health 2025, 1;25(1), 962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeghian, R; Rohani, B; Golestannejad, Z; Sadeghian, S; Mirzaee, S. Comparison of therapeutic effect of mucoadhesive nano-triamcinolone gel and conventional triamcinolone gel on oral lichen planus. Dent Res J (Isfahan) 2019, 16, 277–82. [Google Scholar]

- Sans-Serramitjana, E; Obreque, M; Muñoz, F; Zaror, C; Mora, ML; Viñas, M; et al. Antimicrobial Activity of Selenium Nanoparticles (SeNPs) against Potentially Pathogenic Oral Microorganisms: A Scoping Review. Pharmaceutics 2023, 31;15(9), 2253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mal, J.; Veneman, W.J.; Nancharaiah, Y.V.; van Hullebusch, E.D.; Peijnenburg, W.J.; Vijver, M.G.; et al. A comparison of fate and toxicity of selenite, biogenically, and chemically synthesized selenium nanoparticles to zebrafish (Danio rerio) embryogenesis. Nanotoxicology 2017, 11, 87–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, EL; de Lima, TB; Rados, PV; Visioli, F. Efficacy of topical non-steroidal immunomodulators in the treatment of oral lichen planus: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Oral Investig. 2021, 25(9), 5149–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.