1. Introduction

Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) represents a serious global public health issue [

1]. Once inside the body, HIV affects the immune system, making the organism susceptible to opportunistic diseases. Due to progressive impairment of the immune system, HIV infection creates a chronic health condition with social and economic impacts [

2]. Over the past few decades, effective intervention strategies such as global access to antiretroviral therapy (ART), safe childbirth and breastfeeding practices, and post-exposure prophylaxis administered to the newborn (NB) have successfully reduced HIV transmission from mother to fetus and newborn [

3]. As a result, there has been a significant reduction in the rates of children infected through vertical transmission (VT), despite intrauterine exposure to the virus [

1,

4]. In Brazil, HIV detection rate among pregnant women in 2022 was 3.1 per 1.000 live births (LB), with the Southern region accounting for 28.7% of all cases in the country. Rio Grande do Sul is the second state with the highest detection rate of HIV in pregnancy (12% of all cases nationwide), with a rate of 7.9 cases per 1.000 LB. The city of Porto Alegre, capital of Rio Grande do Sul, exhibits the highest detection rate among Brazilian capitals, being 17 per 1.000 LB, almost six times the national rate [

5]. Children born to HIV-positive mothers but without HIV infection through VT are considered exposed uninfected (HEU). According to data from the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS), it is estimated that the cumulative population of HEU worldwide in 2022 was approximately 16 million [

6].

For a long time, researchers have sought to understand the impacts of HIV on infected children’s lives. Currently, with the increasing population of HEU, efforts have been made to understand how the intrauterine exposure to the virus, maternal ARV and an immunologically adverse intrauterine environment may affect these children in the first months and years of their lives [

4,

7]. Recent studies show that intrauterine exposure to HIV can have negative repercussions throughout development into adulthood. Compared to unexposed children, HEU have a higher risk of morbi-mortality, as well as impairments in growth and neurodevelopment, compromising motor, language, cognition, and behavior areas [

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13].

Among the numerous complications caused, either directly or indirectly, by HIV, auditory system alterations stand out. According to several studies, there seems to be an association between auditory abnormalities and HIV infection in the pediatric population, with hearing loss (HL) taxes ranging from 24 - 39%, primarily conductive HL [

9,

15]. Most of these patients present with middle ear pathologies, such as otalgia, tympanic membrane perforations and otorrhea, with otitis media being the most common finding [

17]. However, regarding HL in HEU children, the literature remains controversial. These children seem to have a higher risk of HL compared to their unexposed peers, but a lower risk when compared to those infected with HIV. 18 It is still unclear how HIV and ART exposure may impact the auditory system of these children [

14].

Early diagnosis of HL in childhood is highly desirable, since its occurrence in the first years of life can lead to significant limitations in speech and language acquisition. Even conductive HL can have negative impacts on child development [

16]. Moreover, without proper auditory rehabilitation, HL can result in adverse effects on psychomotor, cognitive, and educational development [

9,

19].

Despite this, there is no consensus on the need for monitoring these children. The Joint Committee on Infant Hearing (JCIH) does not list HIV as an Indicator of Risk for Auditory Deficiency (IRAD) [

20]. In Brazil, however, the Multiprofessional Committee on Auditory Health (COMUSA) includes HIV exposure in the list of IRAD and recommends monitoring auditory function until the third year of life [

21]. However, this regular follow-up is not the reality in the vast majority of health services in Brazil, despite of public health policies on auditory health and existing recommendations in our country, thus justifying initiatives that contribute to a better understanding of the audiological findings in this population.

2. Materials and Methods

Prospective study, conducted at a public and university-based quaternary hospital located in southern Brazil, which is a reference in prenatal and neonatal care for HIV-positive pregnancies and HIV-exposed NB. The sample was recruited by convenience, including all LB from HIV-positive mothers between May 2021 and March 2023 who continued follow-up after discharge at the Pediatric Infectious Disease Outpatient Clinic of the institution during the first year of life.

Newborns with coexisting congenital infections (rubella, toxoplasmosis, cytomegalovirus [CMV], and syphilis), major congenital anomalies, or genetic syndromes that could result in hearing impairment were excluded. Preterm NB with less than 34 weeks of gestational age (GA), patients who presented with perinatal asphyxia, hyperbilirubinemia with levels indicative of exchange transfusion, and those who received ototoxic medication during the neonatal period (furosemide, vancomycin, or aminoglycosides) or needed to remain in the Intensive Care Unit for 5 days or longer were also excluded.

After birth, eligible NB were identified, and their parents were invited to participate in the study. A NB’s urine sample was collected for Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) testing for CMV infection, to avoid misattributing any HL due to CMV to HIV.

Maternal and gestational data related to HIV infection and treatment were collected through electronic medical record review. Data related to delivery and the NB were also collected, along with information on Neonatal Hearing Screening (NHS). According to the institution’s protocol, HIV-exposed NB underwent Transient Evoked Otoacoustic Emissions (TEOAE) before hospital discharge. Since these NB had no other IRAD, Auditory Brainstem Response (ABR) testing was only performed in cases where TEOAE failed.

All NB received ARV prophylaxis for 28 days, according to the guidelines of Brazilian Ministry of Health (MoH) [

7,

22]. After discharge, they were referred to the Pediatric Infectious Disease Outpatient Clinic of the same hospital, with routine clinical and laboratory follow-up for this population.

The risk of VT was considered as “high” or “low” according to MoH protocol [

7,

22]. The NB was considered at low risk for VT when their mothers used ART regularly, with good adherence to treatment, had started these medications in the first half of pregnancy, and had an undetected viral load (VL) quantification test in the third trimester of pregnancy. All other pregnancy situations were considered high risk for VT. The ART prophylaxis for the NB was given according to the VT risk [

7,

22].

The NB were also classified as appropriate (AGA), small (SGA), or large (LGA) for their gestational age (GA), according to the Intergrowth chart [

23]. According to the routine appointments at the outpatient clinic, infants began the second phase of the study, conducted at a private clinic, where they were referred for the following procedures:

Otolaryngological evaluation, with a focused history related to otolaryngological physical examination;

Audiological evaluation, including Wideband Tympanometry and Auditory Brainstem Response (ABR) with Frequency-Specific Stimulus (FS-ABR);

Wideband Tympanometry was performed using Titan equipment from Interacoustics. Tympanometric curves with test tones of 1000Hz and 226Hz were analyzed according to the recommendation for each age group. For the 1000Hz probe, the curves were classified as normal or abnormal. 24 When using the 226Hz probe, based on the values found for compliance and tympanometric gradient, the responses were classified as type A, B, or C curves. Additionally, acoustic reflexes were tested, classifying them as “present” or “absent” based on the automatic analysis of the equipment.

The FS-ABR was performed using the Eclipse EP25 equipment from Interacoustics and included analysis of the auditory pathway integrity and electrophysiological threshold testing. Tests were conducted during natural sleep, on the lap of the mother or caregiver. Electrodes were placed on the forehead (Fz and Fpz) and on the right (A2) and left (A1) mastoids.

The integrity of the auditory pathway was tested with a click stimulus in alternating polarity and filters from 100 to 3000Hz. A total of 2000 stimuli were presented at a rate of 27.1 per second, at an intensity of 80dBnNA in a monaural mode through insert earphones. The absolute latencies of waves I, III, and V were analyzed, as well as the inter-peak latencies I-III, III-V, and I-V. The electrophysiological threshold testing was performed with the NB CE-Chirp LS® stimulus and alternating polarity, at frequencies of 500, 1000, 2000. and 4000Hz via air conduction. The electrophysiological threshold was considered the lowest value where wave V was present, observed in at least two collections to assess replicability. Thresholds of 35, 30, 30, and 25dBnNA, respectively, were considered normal.

In cases of abnormal electrophysiological thresholds via air conduction, bone conduction testing was performed using the B71 bone transducer at frequencies of 2000 and 500Hz, in an ascending manner, starting at 30 and 20dBnNA, respectively. The electrophysiological threshold was considered the lowest value at which wave V was present.

All infants were defined as HIV not-infected after three undetectable VL tests in the first year of life, along with a non-reactive chemiluminescence serological test at 12-18 months of age [

7].

Data were transcribed into an Excel spreadsheet and subsequently analyzed using the Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS 29.0) software. Quantitative variables with symmetric distribution were described using mean and standard deviation, while quantitative variables with asymmetric distribution were described using median and interquartile range. Categorical variables were analyzed using absolute and relative frequencies. To evaluate the association between HL and maternal, gestational, and neonatal variables, Fisher’s exact test was used. A significance level of 5% (p<;0.05) was considered. The project was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the institution, and all mothers or guardians signed the Informed Consent Form for participation in the study.

3. Results

3.1. Sample Characterization

Between May 1st 2021 and March 31st 2023, a total of 5.931 LB occurred at the study hospital. Of these, 107 births were HIV-exposed, resulting in an incidence of HIV-exposed NB of 1.8 per 1.000 LB. Among the 107 HIV-exposed NB, 27 met exclusion criteria, and 80 were eligible for the study and invited to participate. Of these 80 patients, 38 (47.5%) completed all the planned stages of the study. All NB started ARV prophylaxis in the first hours of life and were not breastfed. The complete characterization of the sample is presented in

Table 1.

3.2. Neonatal Hearing Screening

All patients and underwent Neonatal Hearing Screening (NHS) before hospital discharge. Of the 38 patients, 31 passed the initial testing with TEOAE and 7 were referred for retesting; 4 passed the retesting and 3 failed and were referred for Automatic Auditory Brainstem Response (AABR). All 3 patients failed the AABR and were then referred for specific auditory testing, in the outpatient Otorhinolaryngology clinic in the same hospital.

3.3. Hearing testing

Infants underwent the second phase of the study with a mean age of 7 ± 3.3 months. Tympanometric findings and ABR results were analyzed, divided into evaluation of integrity (absolute latencies and inter-peak latencies) and electrophysiological thresholds.

Table 2 presents the values of absolute latencies and inter-peak latencies along with the tympanometric findings.

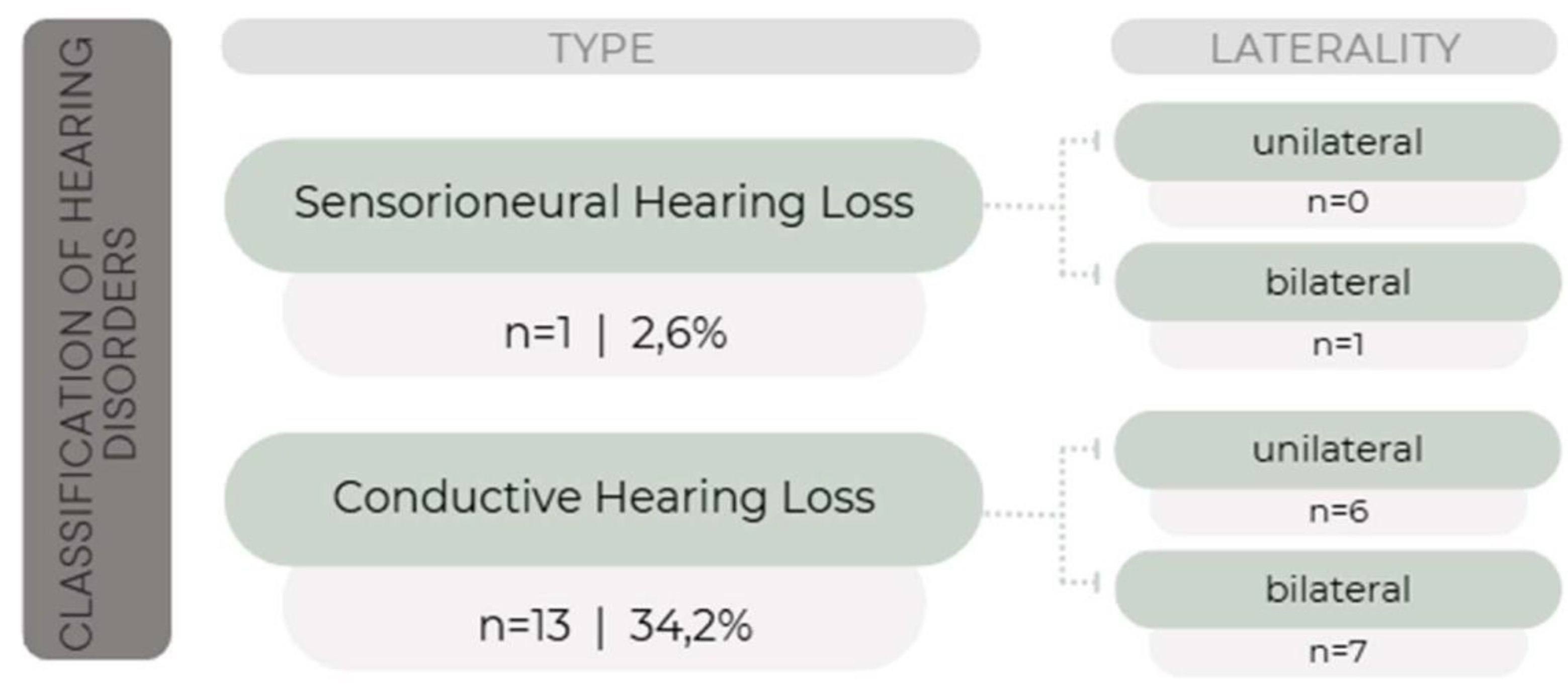

The absolute values of waves I, III, and V and inter-peak intervals were analyzed according to the patterns defined by the equipment for each age group and classified as “normal” or “with delayed latency”. In 23 infants (60.5%), the values were considered normal. Block delay was observed in 13 infants (34.2%) and delay of waves III and V and/or inter-peak latencies I-III and I-V in 2 infants (5.3%). Electrophysiological thresholds were within normal limits at all frequencies assessed in 24 infants (63.1%). In 14 infants (36.8%), there was an abnormality in the electrophysiological threshold at least at one frequency, with 13 having altered air conduction (AC) and normal bone conduction (BC), and 1 patient having altered both AC and BC.

Among the 24 infants with normal electrophysiological thresholds, 2 (5.3%) showed delay of waves III and V and/or inter-peak latencies I-III and I-V. For the 14 infants with threshold abnormalities, findings were classified according to the alteration as: “conductive HL” (when tympanometry and AC were altered, with normal BC), and “sensorineural HL” (when tympanometry was normal but AC and BC were altered). These results are shown in

Figure 1.

All patients who attended the follow-up underwent evaluation by an otolaryngologist. All the infants with normal auditory exams and the only patient with sensorineural HL had normal otoscopy. Infants with conductive HL had otoscopy findings with abnormalities in the middle ear, such as otitis media with effusion.

3.4. Association Between Hearing Loss and Maternal Variables

Table 3 presents the analysis of the association between the HL and maternal

variables (timing of maternal HIV diagnosis), gestational variables (regular ART use, VL quantification, CD4 count, and mode of delivery), and neonatal ones (weight adequacy for GA and VT risk). For analysis purposes, the only infant who presented sensorineural HL was excluded, as it was not possible to test for CMV infection in this patient, making it impossible to determine if HL was caused by HIV exposure or CMV infection. One of the pregnant women was unaware of the timing of the HIV diagnosis. Therefore, the association analyses considered 37 infants, with 24 having normal exams and 13 with conductive HL, except for the “HIV diagnosis” variable, which considered 36 infants.

A significant association was found between HL and maternal CD4 count, with higher maternal CD4 cell count associated with a higher risk of conductive HL. Other associations were not statistically significant.

3.5. Status of HIV Infection

All the evaluated infants were confirmed as HIV not-infected through 3 undetectable VL tests during the first year of life, as well as a negative anti-HIV serology performed after 12 months of age, in accordance with the MoH guidelines for excluding infection in HIV-exposed infants.

4. Discussion

Authors should discuss the results and how they can be interpreted from the perspective of previous studies and of the working hypotheses. The findings and their implications should be discussed in the broadest context possible. Future research directions may also be highlighted.

This study found conductive HL in 34.2% of HIV HEU infants, as well as 1 patient (2.6%) with bilateral sensorineural HL, despite the favorable prognostic characteristics of the sample (full-term births, appropriate weight for GA, high Apgar scores). Most of the pregnant women HIV diagnosed before pregnancy, received regular antenatal care, used ART regularly, had undetectable VL in the 3rd trimester, and had adequate CD4 cell counts.

Studies found in the literature describe middle ear pathologies in children infected with HIV, primarily conductive abnormalities, in up to 18-25% of the patients [

7,

15,

16,

17]. However, regarding HEU NB and infants, the literature is still scarce and limited to the first few months of life, making it impossible to infer data on auditory development [

27]. To date, there is no consensus regarding the association between HEU infants and HL.

Some authors have found normal NHS in this population, inferring normal cochlear function at birth. However, the absence of cochlear alterations observed in NHS does not exclude the possibility of later auditory impairment [

28]. This study found altered NHS in 3 NB (7.9%), considering both test and retest. Of these, 2 (5.3%) showed later normal diagnostic hearing tests (tympanometry and ABR) and 1 (2.6%) was diagnosed with moderate bilateral sensorineural HL and was referred for auditory rehabilitation. This patient was subsequently excluded from the association analyses as there was no CMV detection test performed, making it impossible to infer whether the cause of HL was associated with HIV exposure.

A previous study evaluating auditory responses of HEU using ABR did not find a significant difference in the prevalence of HL between HEU and non-exposed NB [

27]. The same authors demonstrated higher average auditory thresholds at 1, 3, 6, and 9 months in HEU infants when compared to non-exposed ones, using the click stimulus in ABR [

29].

This study is pioneering in evaluating HL in HEU infants during the first months of life using FS-ABR. We have found a 36.8% prevalence of hearing impairment, mainly conductive HL (13 out of 14 patients - 92.8%). These findings demonstrate that, even in the absence of HIV infection, exposure to the virus may interfere in some way with the immune system of these children, making them more susceptible to middle ear infections in the first months of life when compared to the non-exposed population. The causes of this potential immunological alteration are not yet fully understood, with one hypothesis being placental inflammation, that could result in reduced antibody transfer to the fetus, altering its immune capacity. Some studies have revealed differences in CD4 maturation, reduced thymus size, and frequent neutropenia in these patients [

7]. This abnormal immune response also appears to have a direct association with maternal VL at the time of delivery, with children born to mothers with a VL greater than 1000 copies/ml being exposed to a higher risk of immunosuppression due to compromised development of their immune system [

7]. Additionally, the absence of breastfeeding in these patients could be an additional cause of immune deficiency, although the exact contribution of this situation has not been fully clarified [

7]

Maternal, gestational, and neonatal variables were analyzed to try to find an association with the HL detected in the study. No association was found between HL and the timing of HIV diagnosis or the mode of delivery. There was also no association between HL and ART use, which agrees with other studies. 30.31 Little is still known about the effects of ART on the auditory health of children and adolescents.

The present study found no significant association between maternal VL quantification and auditory alterations. It is worth noting that pregnant women included in the study mostly undetectable VL (71.1% of cases), and 68.4% of them had a CD4 count above 500 cells/mm³. These data are consistent with proper prenatal care, following the guidelines of the Brazilian MoH [

7]. A positive association was found between conductive HL and a higher maternal CD4 count, a result not found in any study from the reviewed literature, such as studies by Fasunla et al [

27,

29], which assessed HEU NB and found no significant relationship between HL and maternal CD4 count.

The main limitation of this study was the number of patients who were able to complete the second phase of the research. The number of losses reflects the difficulty in following up with this population, whether due to socioeconomic and mobility challenges, parent’s lack of understanding that HEU infants may still have clinical and laboratory abnormalities resulting from an unfavorable immunological situation, or due to the stigma that HIV exposure causes in families. Additionally, this study was conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic, which further hindered patients’ access to the healthcare system.

Another study’s limitation was the absence of a control group of non-HIV-exposed infants, which would allow for comparison of the results with HEU group, since middle ear alterations occur in the general pediatric population in the first years of life [

9,

26]. To reduce the occurrence of confounding biases, the sample in the present study consisted of infants with no other risk factors for HL besides intrauterine HIV exposure.

Additionally, it was not possible to collect PCR test for CMV in all recruited patients, preventing us from safely excluding HL due to this infection. However, although only 34.2% of the sample was tested, all of these patients had negative results. The HL detected in the present study was conductive HL, which is not compatible with sensorineural HL caused by congenital CMV infection. The only patient with sensorineural HL was excluded from the subsequent analyses. This difficulty in collecting urine for CMV PCR testing was primarily due to the early discharge of most of the NB in the study, who were healthy and stayed only in the Rooming-In Unit, often being discharged before the research team could request and collect the test.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrated a high occurrence of conductive HL in HEU infants with no other IRAD. The importance of auditory monitoring for these children in the first years of life is evident.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to the development of the project, and subsequently to its execution by data collection, analysis, and interpretation. Conceptualization of the study: AZB, ALC, LPSR, LF. Methodology: AZB, ALC, PP, LPSR, LF. Software / Creation of the database of the study: AZB, ALC, PP, LPSR, LF. Validation of the tested methods: AZB, PP, LPSR. Formal Statistical analysis of the results: AZB, ALC, LPR, LF. Data Curation / Tables: AZB, ALC, LF. Writing of the original paper, draft preparation, reviewing, editing: AZB, ALC, LPSR, SSC, LF. Translation / paper submission: LF.

Funding

This research received no external funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of Hospital de Clínicas de Porto Alegre (protocol number code 2021-0230, approved in November, 2021).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.”

Data Availability Statement

The authors declare that all data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files. Some personal patients’ data are not publicly but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. The authors declare that they have no affiliations with or involvement in any organization or entity with any financial interest in the subject matter or materials discussed in this manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

No financial or non-financial benefits have been received or will be received from any party related directly or indirectly to the subject of this article. The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AABR |

Automatic Auditory Brainstem Response |

| ABR |

Auditory Brainstem Response |

| AC |

Air conduction |

| AGA |

Adequate for Gestational Age |

| ART |

Antiretroviral Therapy |

| BC |

Bone Conduction |

| CMV |

Cytomegalovirus |

| COMUSA |

Multiprofessional Committee on Auditory Health (Portuguese) |

| FS-ABR |

Frequence-Specific Automatic Brainstem Response |

| GA |

Gestational Age |

| HEU |

HIV exposed-uninfected |

| HIV |

Human Immunodeficiency Virus |

| HL |

Hearing Loss |

| Hz |

Hertz |

| IRAD |

Indicator of Risk for Auditory Deficiency |

| JCIH |

Joint Commission on Human Hearing |

| LB |

Live Births |

| LGA |

Large for Gestational Age |

| MoH |

Ministry of Health |

| NB |

Newborn |

| NHS |

Neonatal Hearing Screening |

| PCR |

Polymerase Chain Reaction |

| SGA |

Small for Gestational Age |

| SPSS |

Statistical Package for Social Sciences |

| TEOAE |

Transient Evoked Otoacustic Emissions |

| UNAIDS |

United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS |

| VL |

Viral Load |

| VT |

Vertical Transmission |

References

- Friedrich, L; Menegotto, M; Magdaleno, AM; da Silva, CLO. Transmissão vertical do HIV: uma revisão sobre o tema. Boletim Científico de Pediatria 2016, 05(3), 81–6. [Google Scholar]

- de Vasconcelos, MSB; Silva D dos, SB; Peixoto, IB. Coinfecção entre HIV e Sífilis: principais complicações clínicas e interferências no diagnóstico laboratorial. Revista Brasileira de Análises Clínicas 2021, 53(1), 15–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miranda, AE; Santos, PC; Coelho, RA; Pascom, ARP; de Lannoy, LH; Ferreira, ACG; et al. Perspectives and challenges for mother-to-child transmission of HIV, hepatitis B, and syphilis in Brazil. Front Public Health 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slogrove, AL; Powis, KM; Johnson, LF; Stover, J; Mahy, M. Estimates of the global population of children who are HIV-exposed and uninfected, 2000-18: a modelling study. Lancet Glob Health 2020, 8(1), e67–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brasil. Ministério da Saúde. Boletim Epidemiológico - HIV e Aids 2023 [Internet]. 2023. Available online: https://www.gov.br/aids/pt-br/central-de-conteudo/boletins-epidemiologicos/2023/hiv-aids/boletim-epidemiologico-hiv-e-aids-2023.pdf/view.

- UNAIDS. UNAIDS Data 2023 [Internet]. 2023. Available online: https://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/data-book-2023_en.pdf.

- Brasil. Ministério da Saúde. Protocolo Clínico e Diretrizes Terapêuticas Manejo da Infecção pelo HIV em Crianças e Adolescentes. Módulo 1 - Diagnóstico, manejo e acompanhamento de crianças expostas ao HIV [Internet]. 2023, p. 56. Available online: https://www.gov.br/conitec/pt-br/midias/relatorios/2023/RR_PCDTHIVCrianasmdulo1_Final.pdf.

- Benki-Nugent, SF; Yunusa, R; Mueni, A; Laboso, T; Tamasha, N; Njuguna, I; et al. Lower neurocognitive functioning in HIV-exposed uninfected children compared with that in HIV-unexposed children. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr (1988) 2022, 89(4), 441–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawood, G; Klop, D; Olivier, E; Elliott, H; Pillay, M; Grimmer, K. Nature and extent of hearing loss in HIV-infected children: a scoping review. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 2020, 134, 110036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brennan, AT; Bonawitz, R; Gill, CJ; Thea, DM; Kleinman, M; Useem, J; et al. A meta-analysis assessing all-cause mortality in HIV-exposed uninfected compared with HIV-unexposed uninfected infants and children. AIDS 2016, 30(15), 2351–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, K; Kalk, E; Madlala, HP; Nyemba, DC; Jacob, N; Slogrove, A; et al. Preterm birth and severe morbidity in hospitalized neonates who are HIV exposed and uninfected compared with HIV unexposed. AIDS 2021, 35(6), 921–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wedderburn, CJ; Evans, C; Yeung, S; Gibb, DM; Donald, KA; Prendergast, AJ. Growth and neurodevelopment of HIV-exposed uninfected children: a conceptual framework. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2019, 16(6), 501–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fowler, MG; Aizire, J; Sikorskii, A; Atuhaire, P; Ogwang, LW; Mutebe, A; et al. Growth deficits in antiretroviral and HIV-exposed uninfected versus unexposed children in Malawi and Uganda persist through 60 months of age. AIDS 2022, 36(4), 573–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torre, P; Zhang, ZJ; Hoffman, HJ; Frederick, T; Purswani, M; Williams, PL; et al. Auditory function in the pediatric HIV/AIDS cohort study adolescent master protocol up young adults: a pilot study. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes [Internet] 2023 [cited 2024 Jul 6], 92(4), 340–7. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36729663/. [CrossRef]

- Ensink, RJH; Kuper, H. Is hearing impairment associated with HIV? A systematic review of data from low- and middle-income countries. Tropical Medicine & International Health [Internet] 2017 [cited 2024 Jul 6], 22(12), 1493–504. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29078020/.

- Sebothoma, B; Maluleke, M. Middle ear pathologies in children living with HIV: A scoping review. The South African Journal of Communication Disorders 2022, 69(1), e1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khoza-Shangase, K; Anastasiou, J. An exploration of recorded ontological manifestations in South African children with HIV/AIDS: A pilot study. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 2020, 133. [Google Scholar]

- Coleman, M. Exposure to HIV increases risk of hearing loss in children. Hear J 2012, 65(8). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lieu, JEC; Kenna, M; Anne, S; Davidson, L. Hearing loss in children: a review. JAMA 2020, 324(21), 2195–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joint Committee on Infant Hearing. Year 2019 position statement: principles and guidelines for early hearing detection and intervention programs. J Early Hear Detect Interv. 2019, 4(2), 1–44. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, DR; Marone, SAM; Mendes, BCA; Cruz, OLM; de Nóbrega, M. Multiprofessional committee on auditory health: COMUSA. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol. 2010, 76(1), 121–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brasil. Ministério da Saúde. Nota informativa n o 12/2023-CGAHV/.DATHI/SVSA/MS [Internet]. 2023. Available online: https://www.gov.br/aids/pt-br/central-de-conteudo/notas-informativas/2023/sei_ms-0038033904-nota-informativa-12_2023_ral-granulado_revoga-nota-n-11.pdf/view.

- Villar, J; Giuliani, F; Fenton, TR; Ohuma, EO; Ismail, LC; Kennedy, SH. INTERGROWTH-21st very preterm size at birth reference charts. The Lancet 2016, 387(10021), 844–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- British Society of Audiology. Tympanometry - Recommended Procedures [Internet]. 2013, 25. Available online: https://www.thebsa.org.uk/resources/recommended-procedure-tympanometry/.

- Jerger, J. Clinical experience with impedance audiometry. Archives of Otolaryngology - Head and Neck Surgery 1970, 92(4), 311–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buriti, AKL; Oliveira, SHS; Muniz, LF; Soares, MJGO. Evaluation of hearing health in children with HIV/AIDS. Audiology - Communication Research 2014, 19(2), 105–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fasunla, A; Ogunbosi, B; Odaibo, G; Nwaorgu, O; Taiwo, B; Osinusi, D; et al. Comparison of auditory brainstem response in HIV-1 exposed and unexposed newborns and correlation with the maternal viral load and CD4+ cell counts. AIDS 2014, 28(15), 2223–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padilha, MAD; Maruta, ECS; de Azevedo, MF. Ocorrência de alterações auditivas em lactentes expostos à transmissão vertical do HIV. Audiology - Communication Research 2018, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fasunla, A; Omisore, AG; Nwaorgu, OG; Akinyinka, OO. Long-term effects of maternal HIV infection and anti-retroviral medications on the hearing of HIV-exposed infants. West Afr J Med. 2018, 35(2), 90–6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Chao, CK; Czechowicz, JA; Messner, AH; Alarcoń, J; Roca, LK; Larragán Rodriguez, MM; et al. High prevalence of hearing impairment in HIV-infected Peruvian children. Otolaryngology--Head and Neck Surgery 2012, 146(2), 259–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torre, P; Zeldow, B; Yao, TJ; Hoffman, HJ; Siberry, GK; Purswani, MU; et al. Newborn hearing screenings in human immunodeficiency virus-exposed uninfected infants. J AIDS Immune Res. 2016, 1(1), 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Bentivi, JO; Azevedo C de, MP e S; Lopes, MKD; Rocha, SCM; Silva, PCR; Costa, VM; et al. Audiological assessment of children with HIV/AIDS: a meta-analysis. J Pediatr (Rio J) 2020, 96(5), 537–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).