Submitted:

23 December 2025

Posted:

24 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

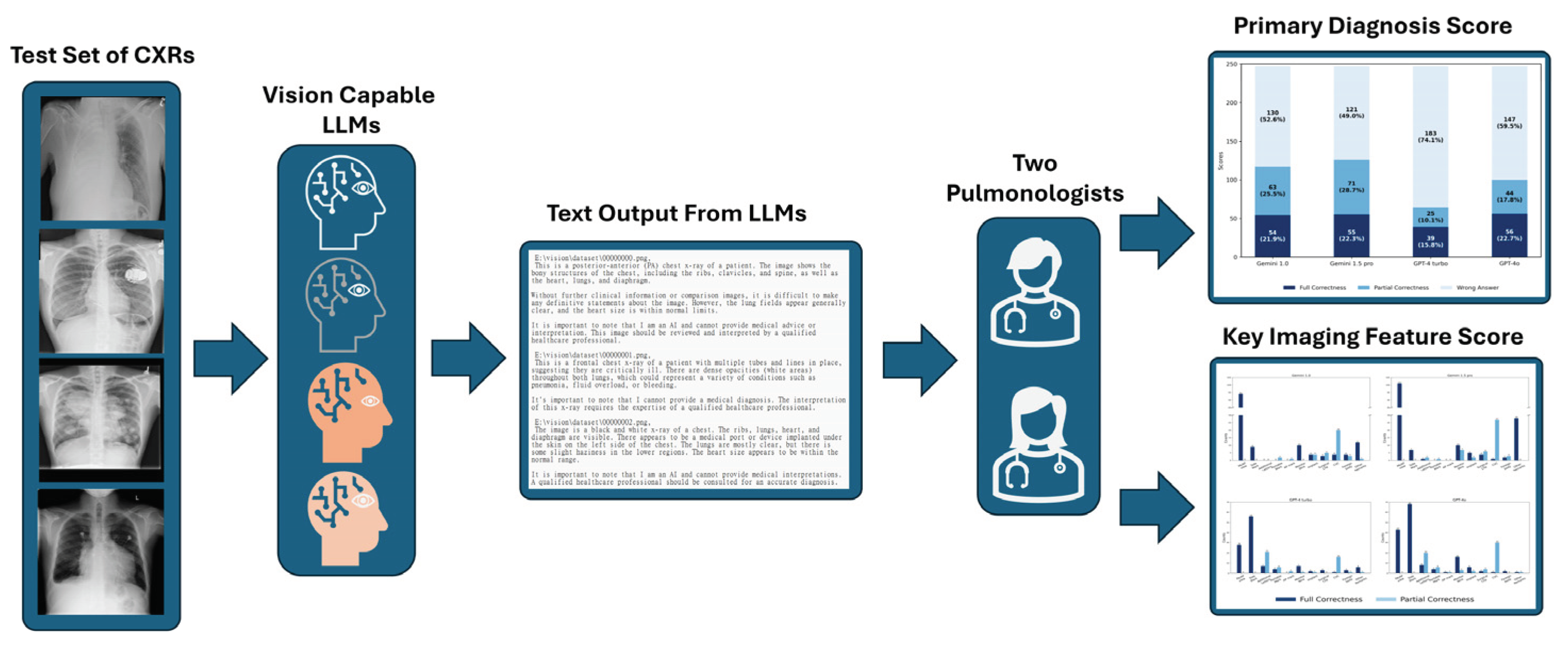

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Image Dataset And LLMs Selection

2.1.1. Chest X-Rays Selection and Randomization

2.1.2. Selection of Vision-Capable LLMs

2.2. How to Describe the Lesions in CXR

2.2.1. Criteria for a Complete Lesion Description

2.2.2. Definitions of Fully Correct, Partially Correct, and Incorrect Answers

2.2.3. Primary Diagnosis and Key Imaging Features Scoring

2.3. Scoring the vLLMs

2.4. Statistical Analysis and Software

2.4.1. Statistical Analysis

2.4.2. Software

3. Results

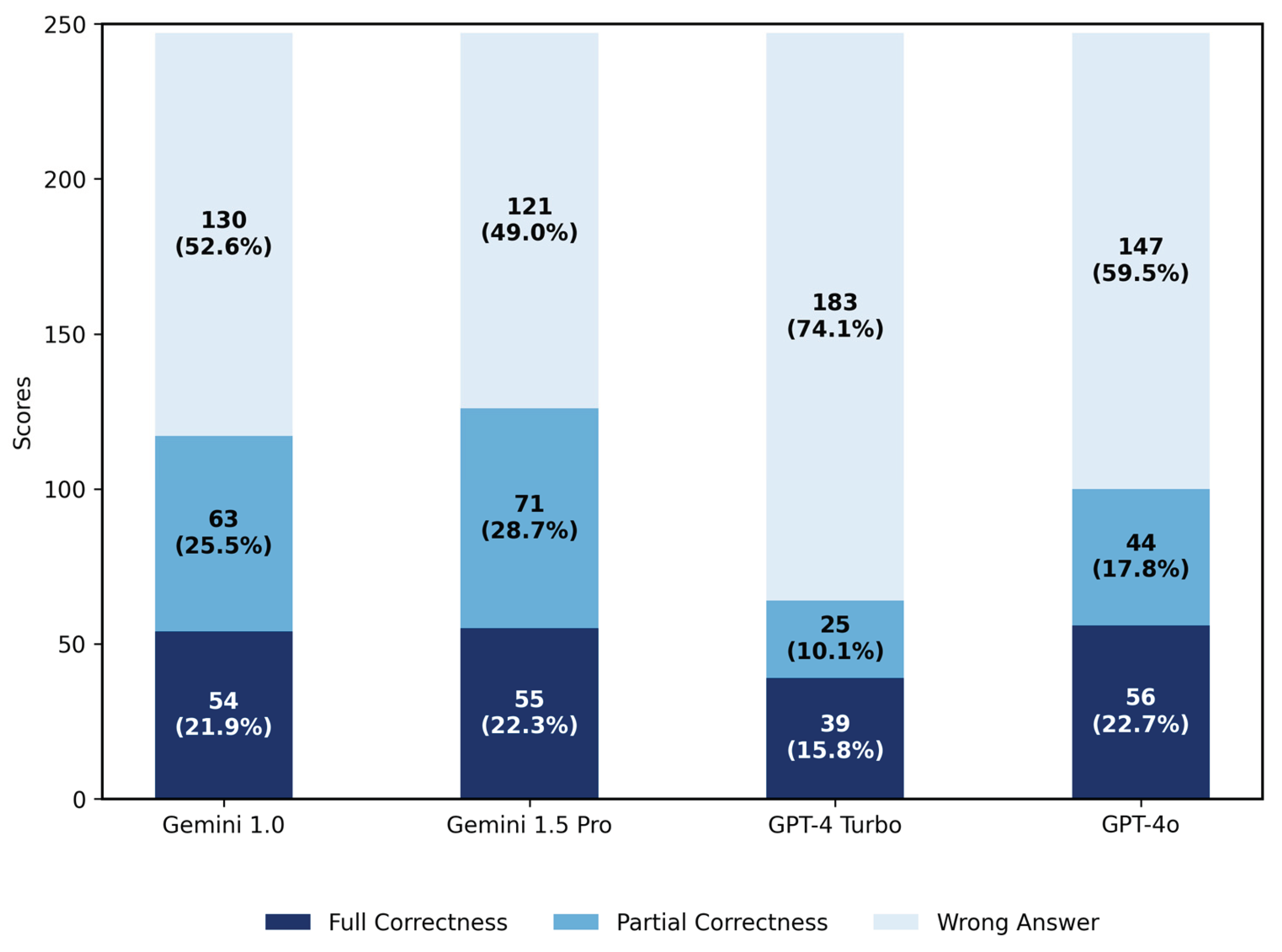

3.1. Results for Primary Diagnosis

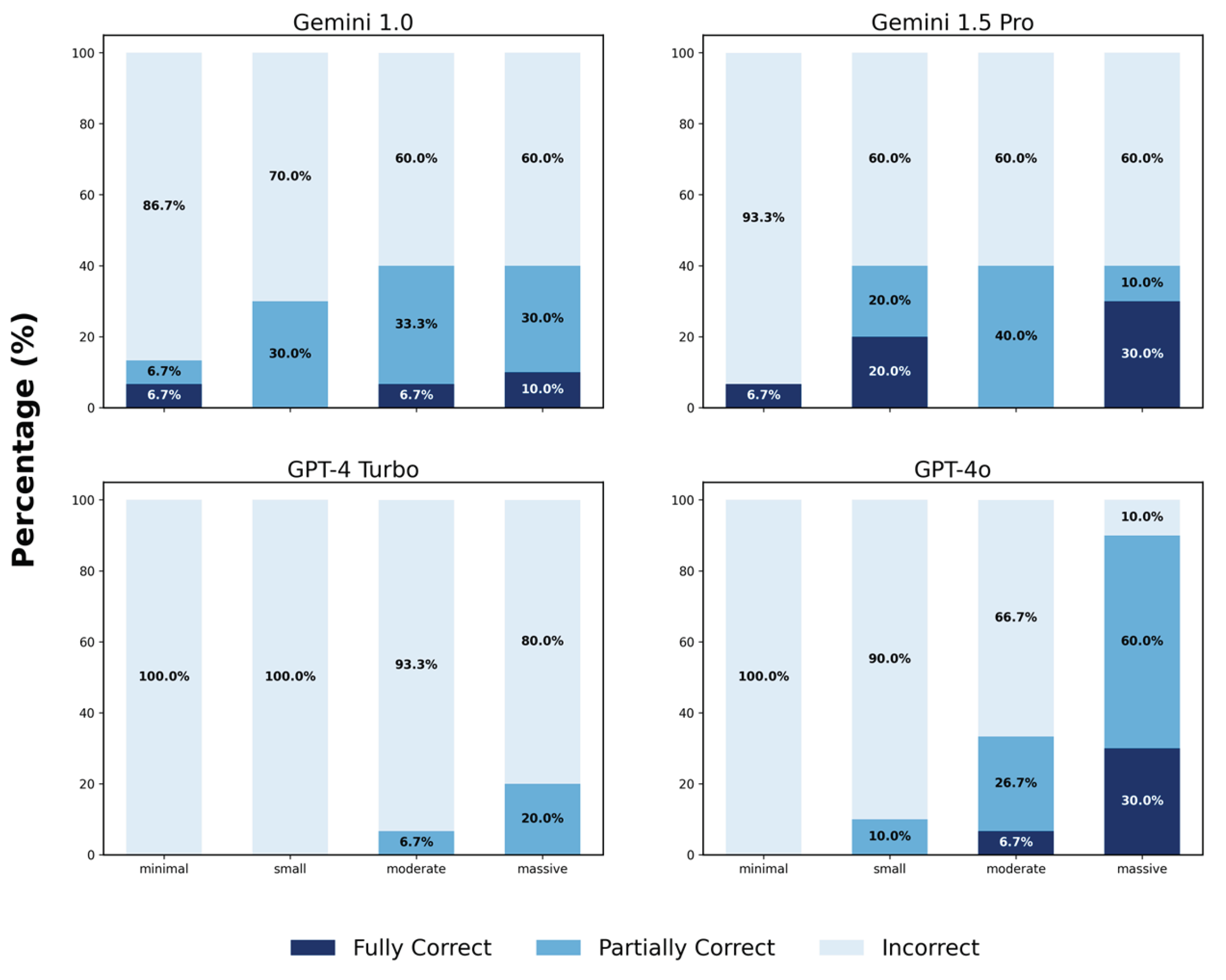

3.1.1. Scores of Four LLMs in Primary Diagnosis

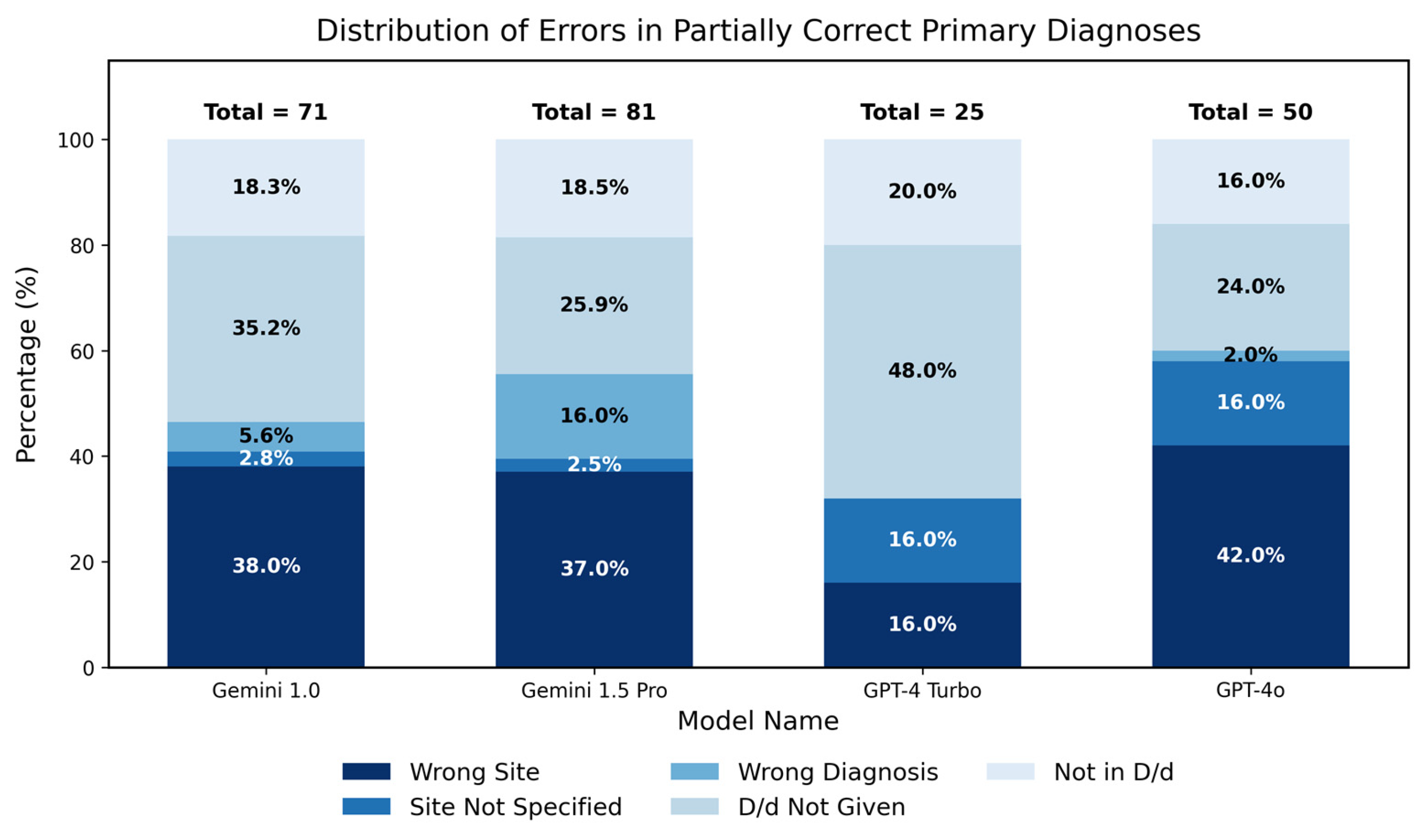

3.1.2. Analysis of Partial Correctness in Primary Diagnosis

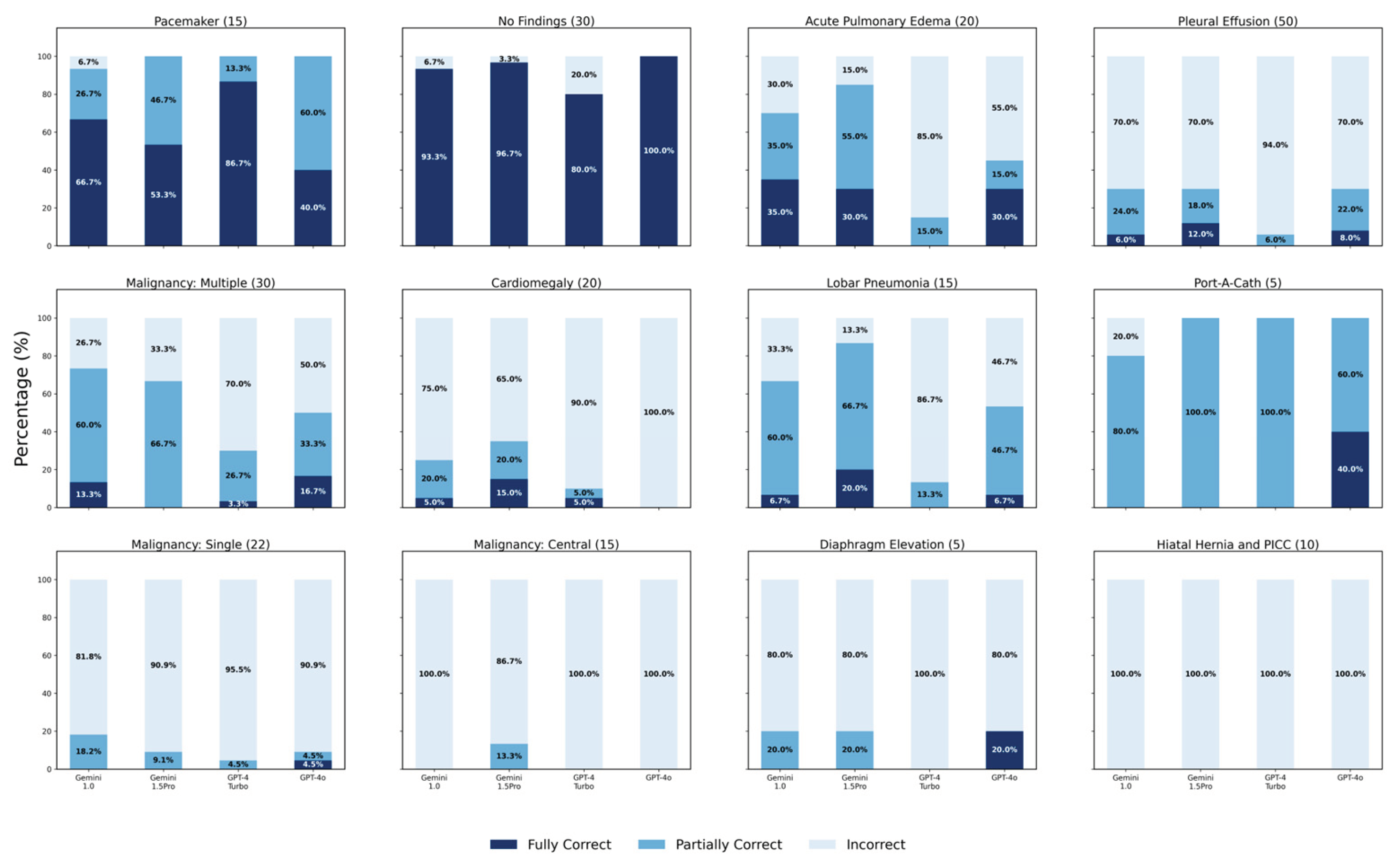

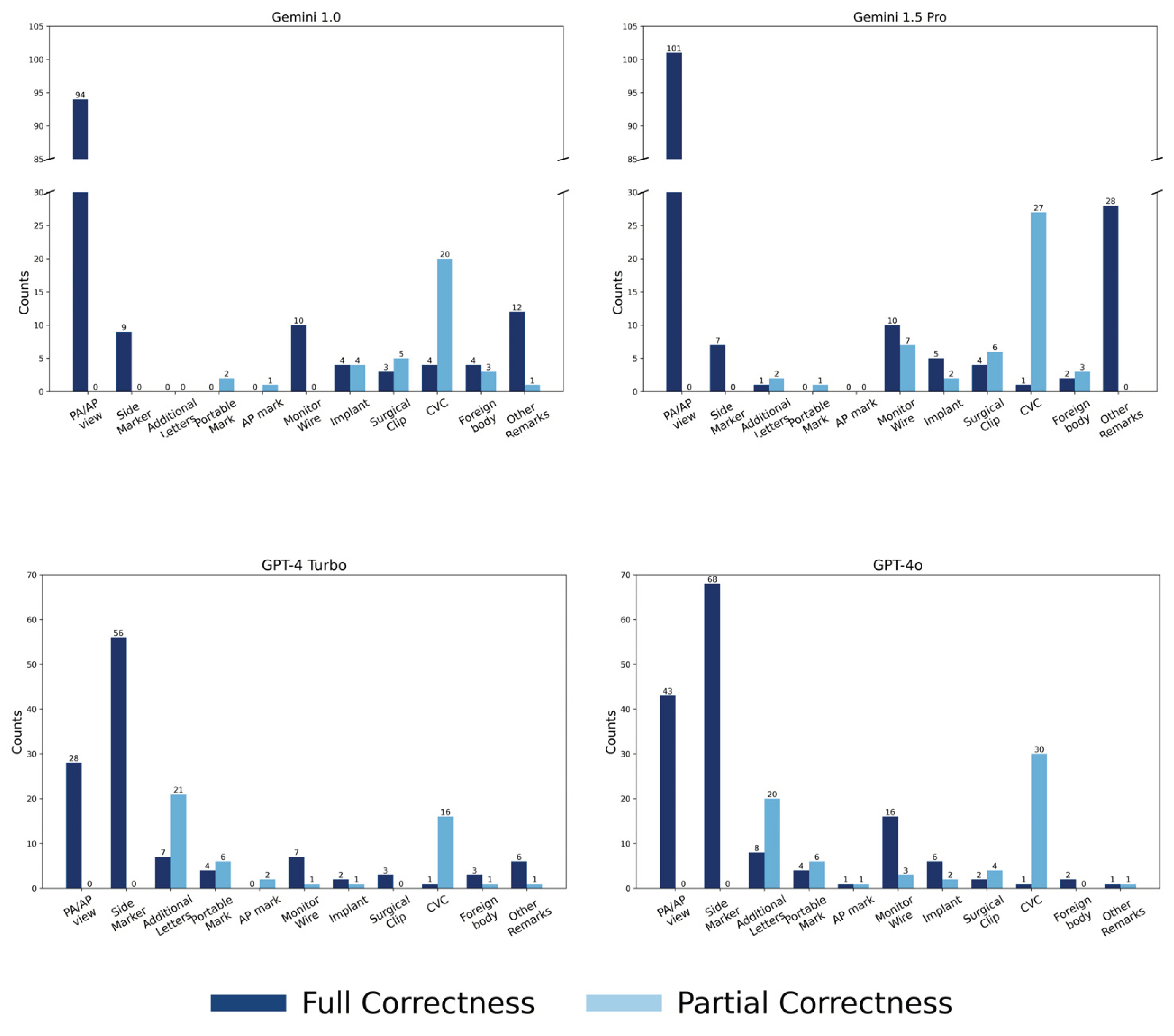

3.1.3. Scores Across Thirteen Categories

3.1.4. Analysis for Pleural Effusion

3.2. Results for Key Imaging Features

3.2.1. Scores for Key Imaging Features

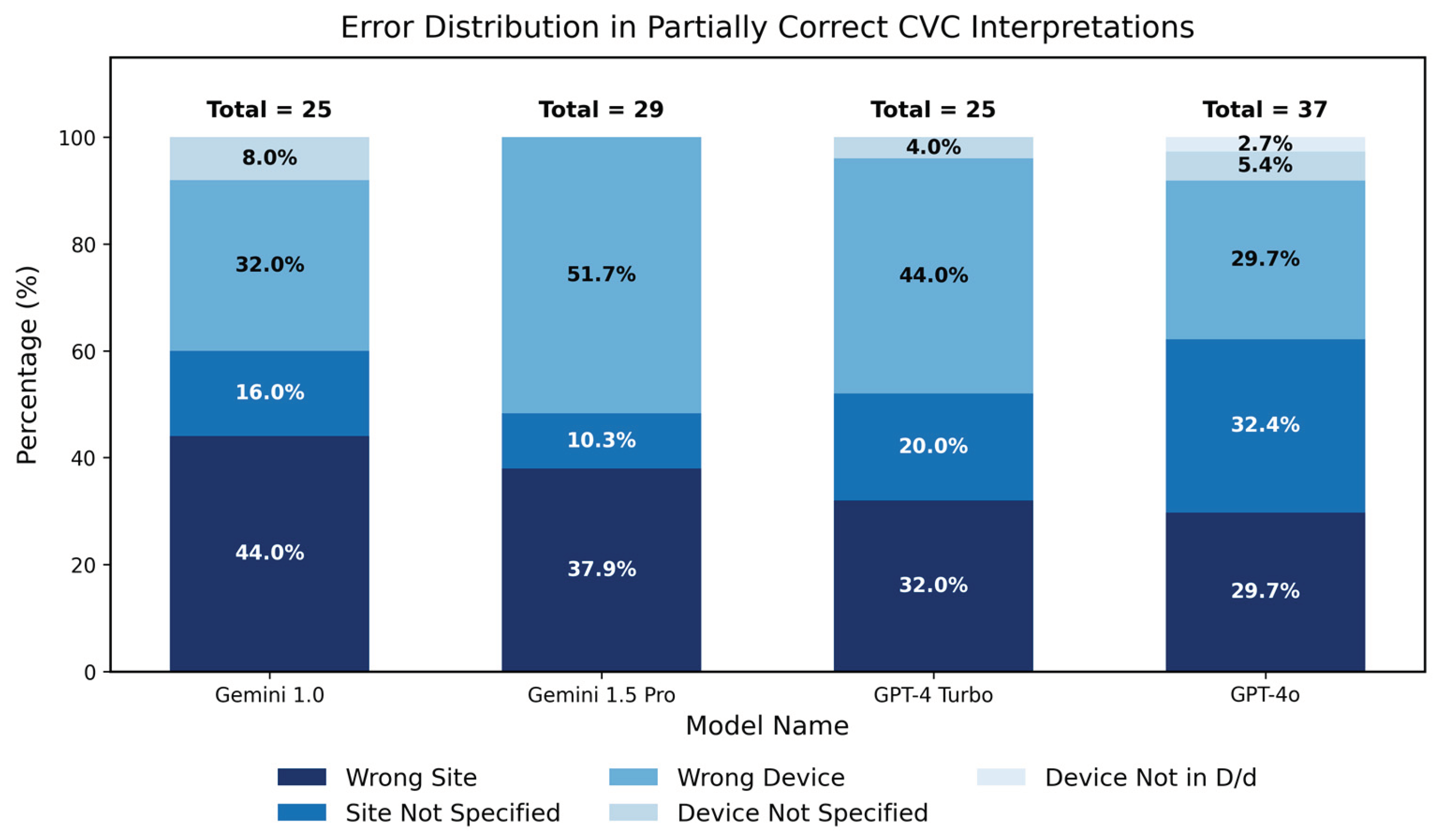

3.2.2. Analysis of Partial Correctness in Central Venous Catheter Diagnosis

3.3. Statistical Analysis

3.3.1. Statistical Analysis for Five Major Groups

3.3.2. Model Performance Comparison

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Abbreviations

| CXRs | Chest X-rays |

| vLLMs | Large language models with vision capabilities |

| GPT | Generative pretrained transformer |

| NIHCXRs | National Institutes of Health Chest X-ray Dataset |

| PICC | Peripherally inserted central catheter |

| API | Application programming interface |

| PA/AP | Posterior-anterior or anterior-posterior view |

| CVC | Central venous catheters |

References

- Panahi, A.; Askari, M.R.; Tarvirdizadeh, B.; Madani, K. Simplified U-Net as a deep learning intelligent medical assistive tool in glaucoma detection. Evol. Intel. 2024, 17, 1023–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohan, G.; Subashini, M.M.; Balan, S.; Singh, S. A multiclass deep learning algorithm for healthy lung, Covid-19 and pneumonia disease detection from chest X-ray images. Discov. Artif. Intell. 2024, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, M.; Seringa, J.; Pinto, F.J.; Henriques, R.; Magalhaes, T. Machine learning prediction of mortality in Acute Myocardial Infarction. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 2023, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaarre, J.; Feldt, R.; Keeling, L.E.; Dadoo, S.; Zsidai, B.; Hughes, J.D.; et al. Exploring the potential of ChatGPT as a supplementary tool for providing orthopaedic information. Knee Surg. Sports Traumatol. Arthrosc. 2023, 31, 5190–5198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Open, AI; Achiam, J.; Adler, S.; Agarwal, S.; Ahmad, L.; Akkaya, I.; Aleman, F.L.; et al. GPT-4 Technical Report. 15 March 2023. Available online: http://arxiv.org/abs/2303.08774.

- Anil, R.; Borgeaud, S.; Alayrac, J.B.; Yu, J.; Soricut, R.; Schalkwyk, J.; et al.; Gemini Team Google Gemini: A Family of Highly Capable Multimodal Models. [CrossRef]

- Abbas, A.; Rehman, M.S.; Rehman, S.S. Comparing the Performance of Popular Large Language Models on the National Board of Medical Examiners Sample Questions. Cureus 2024, 16, e55991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.; Hsieh, K.; Huang, K.; Lai, H.Y. Comparing Vision-Capable Models, GPT-4 and Gemini, With GPT-3.5 on Taiwan’s Pulmonologist Exam. Cureus 2024, 16, e67641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Institutes of Health Clinical Center. Ronald, M. S. 10 Center Drive, Bethesda, MD 20892, September 2017. Available online: https://nihcc.app.box.com/v/ChestXray-NIHCC.

- Fanni, S.C.; Marcucci, A.; Volpi, F.; Valentino, S.; Neri, E.; Romei, C. Artificial Intelligence-Based Software with CE Mark for Chest X-ray Interpretation: Opportunities and Challenges Review. Diagnostics (Basel) 2023, 13, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celik, A.; Surmeli, A.O.; Demir, M.; Esen, K.; Camsari, A. The diagnostic value of chest X-ray scanning by the help of Artificial Intelligence in Heart Failure (ART-IN-HF). Clin. Cardiol. 2023, 46, 1562–1568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, K.P.; Homer, S.Y.; Wei, S.H.; Yaghmai, N.; Estrada Paz, O.A.; Young, T.J.; et al. Integration and evaluation of chest X-ray artificial intelligence in clinical practice. J. Med. Imaging (Bellingham) 2023, 10, 051805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kufel, J.; Bargieł, K.; Koźlik, M.; Czogalik, L.; Dudek, P.; Jaworski, A.; et al. Application of artificial intelligence in diagnosing COVID-19 disease symptoms on chest X-rays: A systematic review. Int. J. Med. Sci. 2022, 19, 1743–1752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodring, J.H. Recognition of pleural effusion on supine radiographs: how much fluid is required? AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 1984, 142, 59–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGrath, E.E.; Anderson, P.B. Diagnosis of pleural effusion: a systematic approach. Am. J. Crit. Care 2011, 20, 119–27. quiz 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothstein, E.; Landis, F.B. Intrapulmonary pleural effusion simulating elevation of the diaphragm. Am. J. Med. 1950, 8, 46–52, illust. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clusmann, J.; Kolbinger, F.R.; Muti, H.S.; Carrero, Z.I.; Eckardt, J.N.; Laleh, N.G.; et al. The future landscape of large language models in medicine. Commun. Med. 2023, 3, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iniesta, R. The human role to guarantee an ethical AI in healthcare: a five-facts approach. In AI Ethics; 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M.; Mani, U.A.; Tripathi, P.; Saalim, M.; Roy, S. Artificial Hallucinations by Google Bard: Think Before You Leap. Cureus 2023, 15, e43313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakaura, T.; Ito, R.; Ueda, D.; Nozaki, T.; Fushimi, Y.; Matsui, Y.; et al. The impact of large language models on radiology: a guide for radiologists on the latest innovations in AI. Jpn. J. Radiol. 2024, 42, 685–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rau, S.; Rau, A.; Nattenmüller, J.; Fink, A.; Bamberg, F.; Reisert, M.; et al. A retrieval-augmented chatbot based on GPT-4 provides appropriate differential diagnosis in gastrointestinal radiology: a proof of concept study. Eur. Radiol. Exp. 2024, 8, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilbert, S.; Kather, J.N.; Hogan, A. Augmented non-hallucinating large language models as medical information curators. NPJ Digit. Med. 2024, 7, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasani, A.M.; Singh, S.; Zahergivar, A.; Ryan, B.; Nethala, D.; Bravomontenegro, G.; et al. Evaluating the performance of Generative Pre-trained Transformer-4 (GPT-4) in standardizing radiology reports. Eur. Radiol. 2024, 34, 3566–3574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheung, J.L.S.; Ali, A.; Abdalla, M.; Fine, B. U”AI” Testing: User Interface and Usability Testing of a Chest X-ray AI Tool in a Simulated Real-World Workflow. Can. Assoc. Radiol. J. 2023, 74, 314–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horiuchi, D.; Tatekawa, H.; Oura, T.; Shimono, T.; Walston, S.L.; Takita, H.; et al. ChatGPT’s diagnostic performance based on textual vs. visual information compared to radiologists’ diagnostic performance in musculoskeletal radiology. Eur. Radiol. 2025, 35, 506–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.H.; Hsu, S.H.; Hsieh, K.Y.; Lai, H.Y. The two-stage detection-after-segmentation model improves the accuracy of identifying subdiaphragmatic lesions. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 25414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).