1. Introduction

The notion of an event takes on different meanings across various fields of computing, each tailored to its specific context. This paper aims to clarify these interpretations, categorize them into distinct groups, and highlight their unique characteristics, with a particular emphasis on distributed systems.

In

Section 3, I propose a taxonomy that segments the domain of event-based systems into categories derived from clear technical criteria. For each category, I provide illustrative examples of real-world systems that employ the approach and discuss their associated trade-offs, including the advantages and challenges they present. This framework aims to foster a shared understanding and language among researchers and practitioners in this field, enabling more effective dialogue and reasoning about the key design decisions underlying event-based systems.

Subsequently,

Section 4 explores two major categories of event-driven systems that I have extensively worked with over the years. The first category pertains to the Apache Kafka ecosystem, which facilitates stream processing. The second category involves collaborative real-time applications, similar to Google Docs. By analyzing these systems through the framework established in

Section 3, I can gain deeper insights into the core design principles that shape event-driven architectures.

Finally, outlines critical open problems that, in my view, merit further investigation and attention from the research community.

2. Related Work

Recent advancements in distributed event-based systems have highlighted the importance of applying AI/ML models for enhanced security. Jyoti Singh’s [

1] contributions explore the use of profiling tools and anomaly detection in collaborative systems, demonstrating the potential of distributed architectures for scalable applications. Singh’s [

2] work also delves into practical implementations, emphasizing transactional memory models that simplify concurrent programming while ensuring system resilience. Furthermore, Singh’s [

3] research provides insights into agent-based simulations, offering a comprehensive analysis of software development models.

Rizan [

4] has made significant strides in the field of structured data extraction and clustering techniques. Rizan’s [

5] efforts include the development of tools like MUS490, which apply unsupervised learning for music categorization, and frameworks for evaluating 3-D model matching, which aid in visual data interpretation. Rizan’s [

6] innovative approaches also extend to real-world applications, such as enhancing defect detection in agricultural products, showcasing the versatility of his methodologies across diverse domains. Akshar Patel’s [

7] investigations focus on optimizing knowledge graph embeddings and improving question-answering systems by leveraging advanced natural language models like RoBERTa. Patel’s [

8] studies on robotic systems address key challenges in hand-eye coordination, combining reinforcement learning with geometric tracking for robust task performance. Patel’s [

9] work on blockchain consensus protocols further explores attack thresholds, contributing to the security and reliability of decentralized systems. Niketa Penumajji [

10] has extensively researched diverse domains, including speech emotion recognition through CNN-based models, and protein fitness prediction using probabilistic techniques. Penumajji’s [

11] exploration of human-AI collaboration sheds light on dynamic feedback mechanisms in decision-making environments. Penumajji’s [

12] work also encompasses frameworks like HBSP for software protection and nonlinear models for broadcast scheduling. Penumajji’s [

13] work provides a multidimensional perspective on optimizing resource utilization and security.

This body of work by Singh [

14], Rizan [

15], Patel [

16], and Penumajji [

17] illustrates a multifaceted approach to addressing contemporary challenges in distributed systems, clustering, and AI-enhanced methodologies, paving the way for robust, scalable, and intelligent frameworks.

3. A Taxonomy of Event-Based Systems

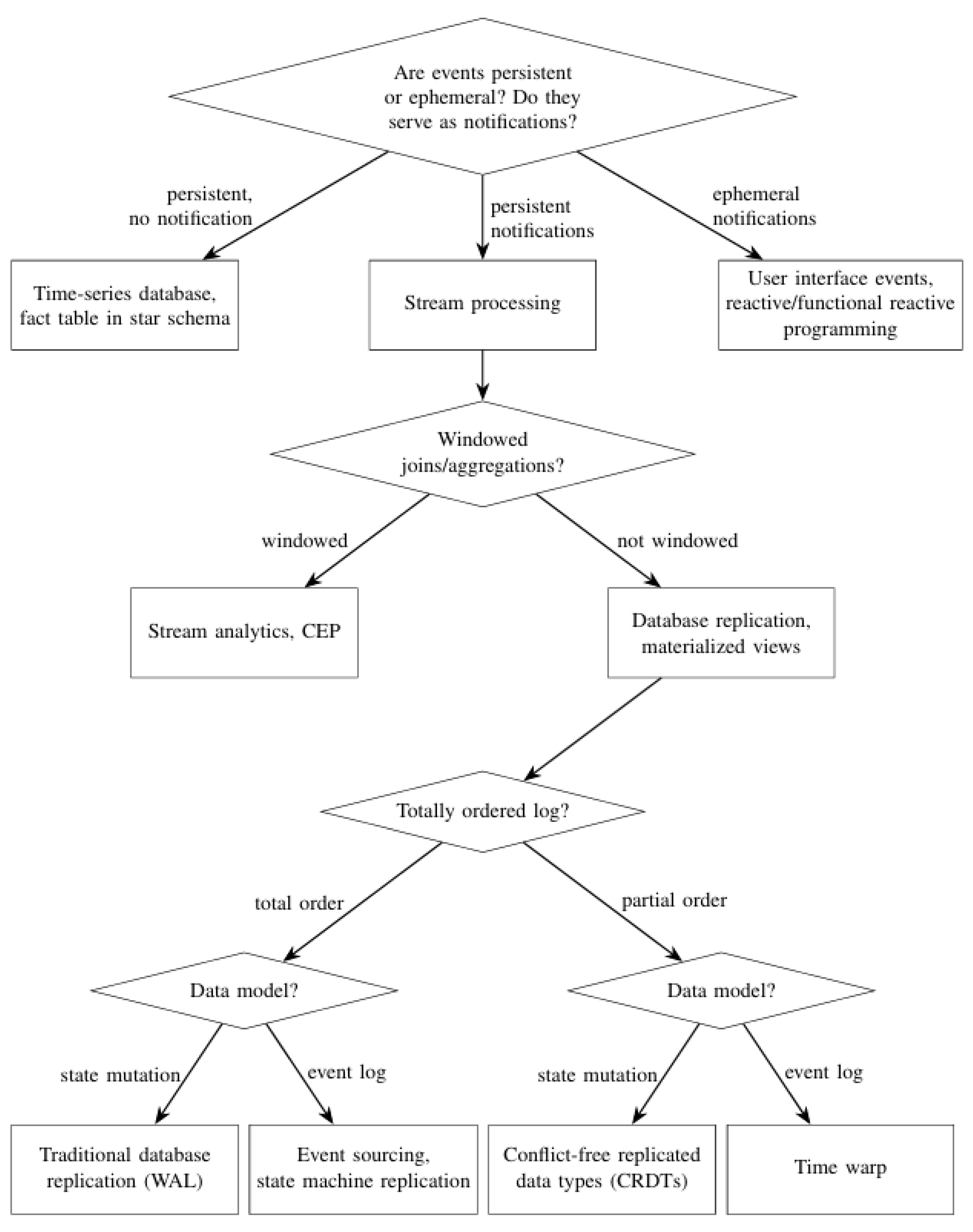

This taxonomy organizes the various applications of events using the flowchart in

Figure 1. While it is designed to provide a comprehensive overview, it does not aim to capture every subtlety or edge case within the field. Some categories may naturally overlap, and the distinctions between them might occasionally appear ambiguous. Nevertheless, this framework is intended to serve as a guiding structure for analyzing and reasoning about the broad spectrum of event-based systems. It offers a pragmatic lens for both researchers and practitioners to navigate the complexities of event-driven architectures.

3.1. Notifications and Persistence

Broadly speaking, an event can serve three distinct purposes:

It can act as a notification, signaling that a specific action has occurred;

It can be a persistent record, documenting the occurrence of an action; or

It can fulfill both roles simultaneously.

Notification events are widely encountered in various applications. For instance, JavaScript programs in web browsers often register functions to respond to user actions such as mouse clicks or keystrokes. Here, the user interaction—like a click or a keypress—constitutes the event [

18]. Many graphical user interface (GUI) frameworks utilize analogous mechanisms for routing user input events to designated callback functions, commonly referred to as

event handlers. Contemporary operating systems utilize asynchronous input/output (I/O) techniques, where an

event loop handles notifications about completed I/O requests [

19]. Furthermore, discrete event simulations represent simulated occurrences using this type of event [

20]. Reactive programming paradigms, such as functional reactive programming (FRP), introduce higher-level abstractions for working with

event streams, offering capabilities like dataflow programming models [

21,

22].

In all these examples, events are ephemeral—they exist only in memory during the lifespan of a single process and are not typically saved to disk. As such, they are transient and disappear when the process ends or is restarted.

In contrast, persistent events are designed primarily for recording occurrences over time, often without involving immediate notifications. Examples include time-series databases, which log periodic sensor readings, price updates, or activity traces of people or machines [

23]. Similarly, in data warehouses or business intelligence systems, the fact tables in star or snowflake schemas typically log timestamped events like product purchases [

24]. Persistent events are primarily intended for historical analysis, trend identification, and generating reports.

Some systems blend these two paradigms, treating events as both persistent records and notifications that trigger specific application behavior. Such systems often fall under the category of

stream processing, which encompasses subcategories that will be discussed later. Features like

materialized view maintenance and

continuous queries—which automatically update query results as the underlying data changes—also exhibit characteristics of event notifications [

25,

26].

In distributed systems, messaging-based programming models often utilize events as notifications that initiate application logic. For example, the

actor model facilitates communication between lightweight threads or actors, potentially across multiple machines, using message-passing [

27]. While many such systems rely on ephemeral messages, some include mechanisms to ensure persistence of actor states or messages [

28]. For clarity, this taxonomy classifies systems as "persistent" only if their events and states are durable and resilient to crashes or network faults; those relying on best-effort message delivery are considered to handle "ephemeral notifications."

3.2. Segmenting Data Streams for Efficient Processing

Focusing on systems that combine persistence with notifications, it is useful to distinguish them based on their ability to perform event-driven operations. The simplest stream processors utilize stateless operators, where each event is handled independently, relying solely on the data within the event itself. For example, a stateless operator might filter events based on whether a particular property falls within a given range.

However, many real-world applications require processing logic that integrates information across multiple events. This could involve aggregations, such as computing totals, averages, or counts, or creating compound events from multiple inputs. Other systems might employ sophisticated state machines to model complex behavior [

29].

Some stream processors focus on scenarios where related events occur within narrow time frames. For instance, stock trading systems might compute asset price ranges for hourly or daily intervals, while fraud detection systems analyze patterns of recent credit card activity. These processes are often termed

sliding-window joins or aggregations. Various window types—such as tumbling or sliding windows—impose a time boundary, ensuring events outside the specified interval are treated as unrelated [

30,

31]. Windowing is widely used in streaming analytics and

complex event processing [

32].

Conversely, some applications require combining events regardless of how far apart they occur in time, making windowing unsuitable [

25]. For instance, in a social network like Twitter, a user might post messages and update their profile photo. Linking the user’s latest photo to each message might involve accessing profile photo updates that occurred years prior.

In SQL, this operation might resemble:

Here, a

message event corresponds to a database insertion, while a

profile update event modifies existing data. A stream processor handling such events essentially performs continuous query execution, maintaining a materialized view of the query result [

25]. This requires a mechanism to update historical records retroactively or apply policies dictating how data evolves over time. Both approaches have practical applications, but retroactive updates are often more natural to express in SQL.

3.3. Database Replication and Events

Let’s dive into systems where events are both persistent and serve as notifications but don’t involve windowing. These systems start to look a lot like database replication. At its core, replication is about ensuring that multiple machines have the same copy of data. All replicas ultimately converge to an identical state, ensuring that every committed transaction is consistently incorporated into the final state.

Now, let’s think about this in terms of events: every database transaction that modifies the data can be seen as an update event. Processing these events means applying the updates to the database state. When data gets replicated from one machine to another, it’s essentially the event traveling through the system. If the transaction only reads data without modifying it, it may not count as an event, depending on the system.

Replication systems generally fall into two categories:

Log-based replication: These systems organize events into an ordered, append-only log.

Other replication methods: Examples include gossip protocols, anti-entropy mechanisms, or setups where clients update multiple replicas independently.

The beauty of the log-based approach lies in its total order: all replicas process events in the same sequence. This log is usually managed by a leader (or master), who decides the order of events, while other replicas (followers) follow suit. In the event that the leader fails, consensus protocols such as Raft or Multi-Paxos elect a new leader and maintain smooth operation.

Traditionally, the specifics of these logs (like what events look like) have been hidden from applications. Some systems use a write-ahead log (WAL) to track changes to the database’s internal structures, while others use separate replication logs. But with advances in change data capture (CDC), I now extract meaningful events (like row insertions, updates, or deletions) and expose them to stream processing systems.

3.4. State Machine Replication (SMR)

Here’s an interesting shift in perspective: instead of treating the database state as the main thing and events as a side-effect, I flip the script. In this approach, events are the core, and the database state is just a by-product of processing these events. This idea is known as state machine replication (SMR) or event sourcing.

In SMR, applications don’t directly alter the database. Instead, they generate events that represent the action (like a "student unenrolled from course X"). These events are then appended to an immutable log. Replicas process these events in the same order, ensuring consistency. As long as the event processing logic is deterministic and starts from the same initial state, all replicas will end up in sync.

The database state essentially serves as a tangible representation of the event log, reflecting its recorded transactions in a structured format. A major advantage here is clarity. Well-designed events often describe intent in a way that’s easy for humans to understand. For example, “student X dropped course Y for reason Z” is much clearer than details about which rows were added or deleted in various tables. This makes debugging and auditing far simpler.

Another big plus is flexibility. Need to change the way events are processed? You can replay the log with the updated logic, rebuild the database state, and switch to the new version without losing history. This approach even works for maintaining multiple views of the same event log.

That said, this model isn’t perfect. It’s less familiar to developers used to traditional databases, and storing/replaying logs can get expensive with high event rates.

3.5. Blockchains and SMR

Blockchain technology exemplifies State Machine Replication (SMR), where the sequence of blocks serves as an immutable event log. The ledger, which maintains records such as account balances, represents the system’s state. Meanwhile, smart contracts or transaction processing mechanisms function as state transition rules, governing how the system evolves with each new transaction.

While this approach brings power and flexibility, it’s not always the right tool for every job. High event rates and the complexity of indirect state management can make it challenging for some applications. But where it fits, SMR offers a fascinating way to rethink how I build and maintain systems.

If records must be permanently deleted to comply with regulations like the GDPR’s right to be forgotten [

33], handling an immutable event log requires strategic management. One approach involves periodically reconstructing the log to exclude sensitive data. Alternatively, personal information can be encrypted with user-specific keys, ensuring that if a deletion request is made, discarding the corresponding key renders the data inaccessible and effectively erased [

34].

3.6. Partially Ordered Events

Systems utilizing Write-Ahead Logging (WAL) or State Machine Replication (SMR) typically assume that all replicas execute events in a strictly uniform order. This assumption holds true within a single data center, where leader-based replication and consensus protocols ensure consistency. However, when replicas are distributed across multiple geographic regions or operate over unreliable networks, preserving a consistent event log becomes considerably more complex. In such scenarios, committing an event may require at least one network round-trip to a designated leader or a majority of replicas, leading to increased latency and resource consumption.

In scenarios where replicas must operate independently, even when disconnected (ensuring availability and partition tolerance as per the CAP theorem [

35]), maintaining a totally ordered log becomes infeasible [

36,

37]. Instead, the system can guarantee a causal order [

38], where events are partially ordered. In a causally ordered system, some events are processed sequentially if one

happens before another [

39], while others may occur concurrently, allowing replicas to process them in different sequences [

40]. This approach is commonly referred to as

optimistic replication [

41].

Even in systems with partial ordering, a total order can be established retrospectively using logical timestamps, such as Lamport timestamps [

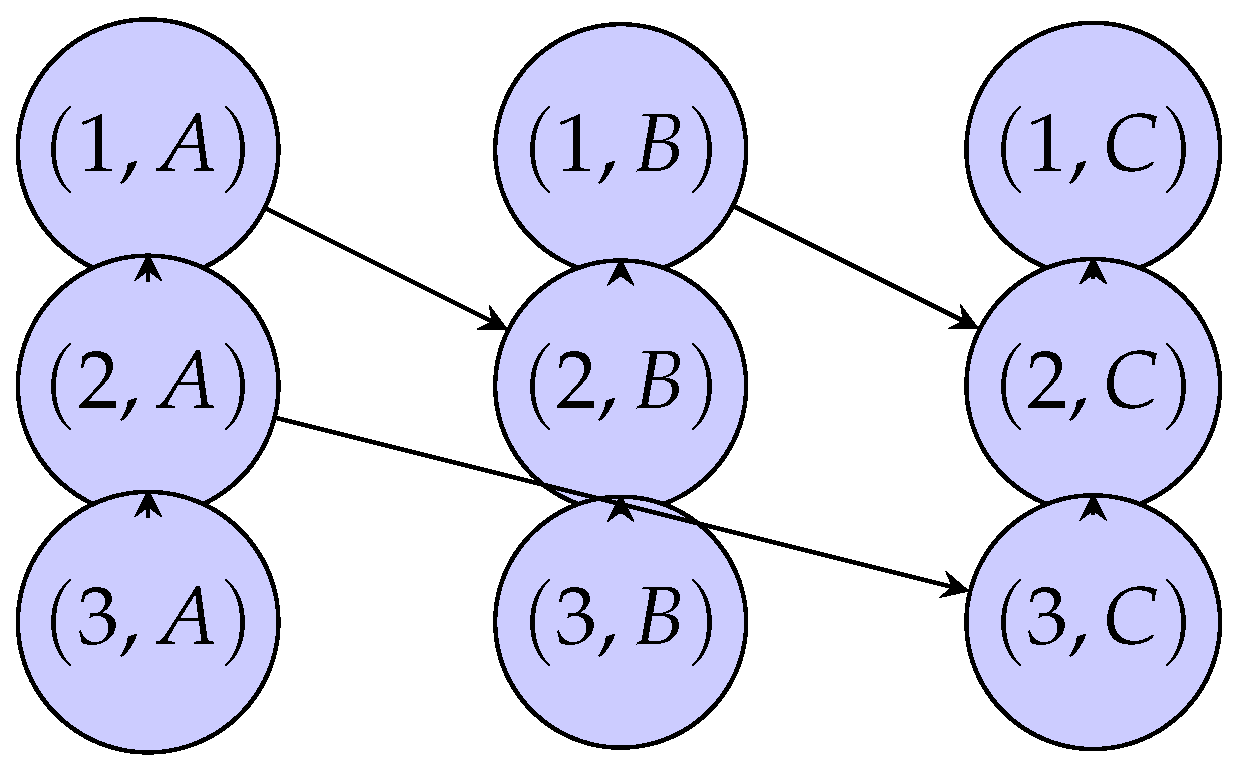

39]. These timestamps typically combine an incrementing counter with a globally unique replica ID. For instance, as shown in

Figure 2, two replicas may independently generate events while disconnected. When connectivity is restored, the replicas exchange events and merge them into a total order based on their timestamps. Events are first sorted by the counter value and, in case of ties, by replica ID (e.g., assuming

).

While timestamp ordering ensures a completely ordered sequence of events, it differs from a conventional log because new events are not always appended sequentially at the end. For instance, when replica B receives event c from replica A, it may need to place it before its locally generated events x and y. Likewise, replica A must insert event x between its existing events c and d, maintaining the intended order.

This timestamp-based approach can mimic SMR-like functionality: replicas deterministically apply events in timestamp order to maintain consistent states. Provided every replica eventually receives all events, they will converge to the same state. However, handling out-of-order events requires replicas to rollback their state to the point of insertion, apply the event, and then replay subsequent events [

42]. This technique, known as

time warp [

43], ensures eventual consistency but introduces computational overhead.

The performance of the rollback-and-replay mechanism is highly dependent on the degree of out-of-order event arrivals. When events are mostly received in chronological order, the associated overhead remains minimal [

44]. However, if substantial reordering is necessary, the computational burden of arranging

n events into a sequential order can increase significantly, often exhibiting quadratic complexity (

).

Moreover, rollback-and-replay introduces challenges when processing events that result in external side effects, such as sending notifications or emails. Since these actions cannot be undone, compensatory actions—like sending a follow-up email—might be required to correct unintended effects. If such compensatory measures are deemed unacceptable, alternative strategies such as State Machine Replication (SMR) or other strongly consistent techniques become necessary.

3.7. Conflict-free Replicated Data Types (CRDTs)

In paradigms like event sourcing and SMR, events are often treated as the core representation of application data, with the replica state being reconstructed from the event log. An alternative approach, as discussed in

Section 3.4, flips this relationship: the mutable replica state becomes the primary data structure, and events are generated automatically as a side effect of state changes. This inversion of focus is the foundation of

Conflict-free Replicated Data Types (CRDTs) [

45].

CRDTs are specialized data structures designed for collaborative environments, supporting various types of abstract data, such as sets, maps, lists, trees, and graphs [

46]. Users perform operations like adding or removing elements from a set or assigning values to keys in a map, even when their devices are offline or disconnected from the network.

In operation-based CRDTs, every change made to the data structure is logged as an event, commonly referred to as an

operation, that encapsulates the modification. These operations are partially ordered, with causal ordering being a typical method for defining dependencies [

47]. When a replica obtains an operation from a peer replica, the Conflict-Free Replicated Data Type (CRDT) algorithm incorporates it into the local state by executing the corresponding update. The algorithm is specifically designed to ensure that applying concurrent operations in any order yields the same final state. This inherent commutativity eliminates the need for a globally consistent event order, enabling replicas to converge to a consistent state efficiently.

Many CRDTs exhibit behavior that aligns with the time warp model [

48]. However, CRDTs typically offer better performance by avoiding the need for rollback and replay mechanisms inherent in a time warp. The state mutation approach in CRDTs is particularly suitable for applications where users directly manipulate the state, such as text editors where users add or delete text or graphics tools where users interact with objects on a canvas.

3.8. Local-first Collaboration Software

In recent years, my team and I have been investigating innovative approaches to collaboration software, focusing on developing tools that facilitate seamless teamwork by allowing multiple users to co-edit and manage shared files in real-time. These files may range from text documents to drawings, spreadsheets, or even to-do lists. A critical requirement for mobile applications is offline functionality: for instance, users should be able to update a to-do list even when they lack cellular data connectivity. Consequently, these applications naturally align with the persistent, non-windowed, and partially ordered categories in the taxonomy.

I have adopted a

local-first approach [

49], where each user’s device acts as a fully independent replica, relying on its local storage for data persistence. Any changes made by a user are immediately reflected on their device, even when offline, and the updates are synchronized with other replicas as soon as a network connection becomes available.

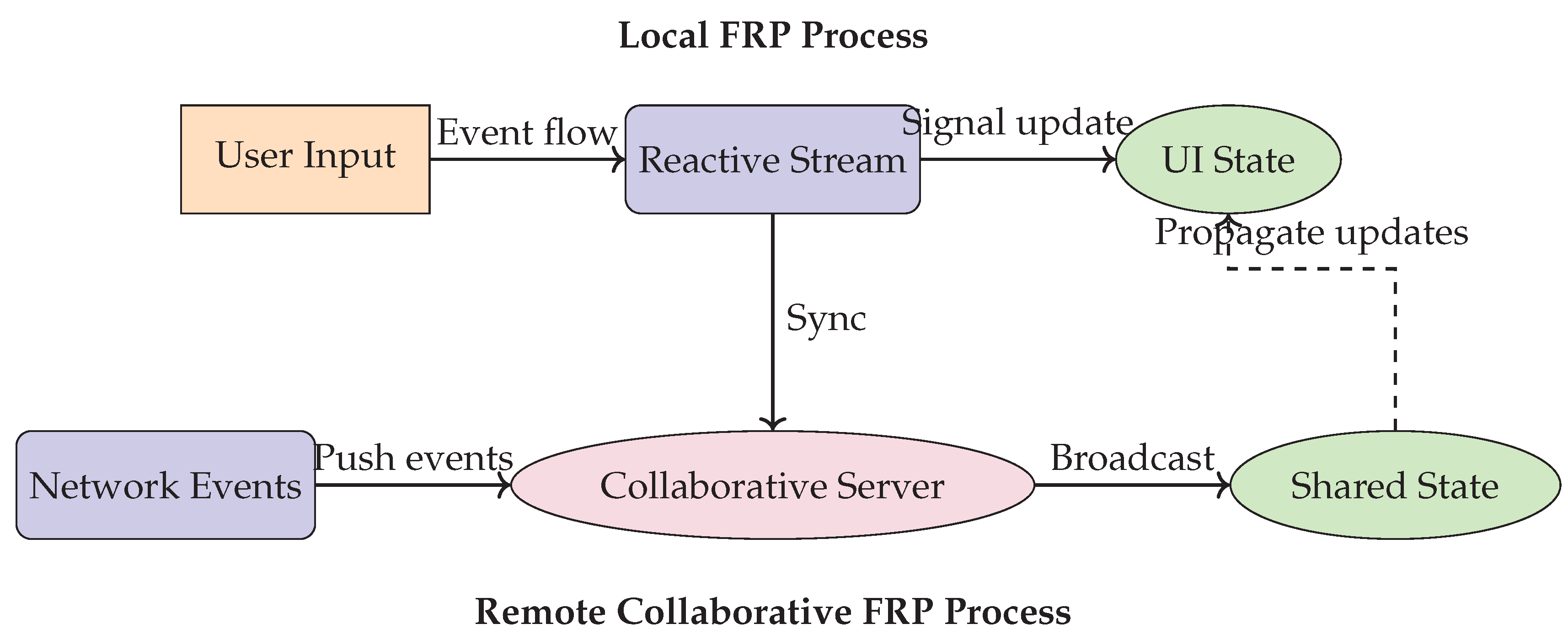

To achieve this, I use CRDTs, which generate events describing data updates as a side effect of state mutations. These events enable real-time collaboration, as discussed in

Section 3.7, by broadcasting changes across all replicas. Events serve as key triggers for updating the user interface within the

functional reactive programming (FRP) framework, as demonstrated in

Figure 3. A document’s state is maintained using an Automerge Conflict-Free Replicated Data Type (CRDT), which is then processed by a rendering function to generate the corresponding user interface elements [

50]. Libraries like Facebook’s React

1 are commonly used for this purpose in web applications.

Event handlers attached to UI elements modify the Automerge CRDT state when triggered. These modifications automatically update the UI via the rendering function, ensuring a one-way data flow: the UI state is always derived from the Automerge state. This approach simplifies reasoning about the system, as all user inputs follow the same logical flow.

When changes occur, the CRDT generates events, persists them locally, and propagates them to other replicas using messaging middleware. Upon receiving an event, remote replicas use the same rendering process to update their local states, enabling seamless real-time collaboration. This unified treatment of local and remote events significantly simplifies development, as demonstrated by the PushPin prototype [

50].

These change events also serve as a complete editing history, much like Git commits. Persisting events allow us to reconstruct document states from any point in time, visualize version differences, and enable workflows like suggesting changes and merging branches. Users can even create multiple branches to experiment with different versions of a document before deciding which changes to merge. This functionality arises from modeling the application state as a structured sequence of interdependent events, maintaining a partial order among them.

3.9. CRDT Limitations and Time Warp Model

Despite their clear advantages, CRDTs are not without their limitations. They are restricted by the fixed operations provided by the data types they are designed to handle. For instance, list-based CRDTs support basic operations like inserting or removing elements, but they typically fall short when it comes to more complex manipulations, such as reordering the list items [

51]. On the other hand, the time warp model offers increased flexibility by allowing any deterministic, pure function to process events, providing a more versatile solution for complex use cases.

Moreover, the deterministic nature of time warp systems lends itself well to integration with AI/ML models for security analysis, enabling precise replay and inspection of potentially malicious behavior in distributed collaborative applications.

4. Practical Examples

This section presents a practical exploration of the concepts discussed in

Section 3, drawing on my firsthand experiences. I delve into two distinct areas: stream processing using Apache Kafka and collaborative applications that allow multiple users to edit shared documents in real-time.

4.1. The Kafka Ecosystem

Apache Kafka serves as a robust event-driven platform for message brokering and stream processing [

52,

53]. It is widely adopted in business environments, where it is used to publish streams of events related to various business processes, which are then consumed and processed by different organizational teams [

54]. Kafka’s ecosystem is complemented by frameworks such as Kafka Streams, Flink [

29], and Samza [

55,

56], as well as a SQL interface (ksqlDB) and tools for change data capture (e.g., Kafka Connect and Debezium [

57]).

In Kafka, events are organized into topics, and subscribers select topics of interest. For scalability, each topic is divided into partitions, which are independently processed and maintain a total order of events. However, this design introduces a trade-off: while partitions enhance scalability, they preclude a global event order across partitions.

When Kafka is employed in event sourcing or SMR scenarios, a single partition may suffice for small-scale systems but limits scalability. Alternatively, system states can be divided into independent partitions aligned with event logs. For instance, events related to a specific entity can be assigned to a single partition, allowing parallel processing. However, this approach falters in cases where events span multiple entities or require coordination across partitions.

To address such challenges,

Online Event Processing (OLEP) [

58] decomposes multi-entity interactions into multiple stages of stream processing. For example, validating an event against the current state—such as checking if a theater seat is available before booking—requires a two-stage process. Initially, an event represents an intent to perform an action; subsequently, a stream processor validates the action against the current state and generates a final event if permitted [

58].

4.2. Local-first Collaboration Software

In recent years, my team and I have been investigating innovative approaches to collaboration software, focusing on developing tools that facilitate seamless teamwork on shared documents and projects. These files may range from text documents to drawings, spreadsheets, or even to-do lists. A critical requirement for mobile applications is offline functionality: for instance, users should be able to update a to-do list even when they lack cellular data connectivity. Consequently, these applications naturally align with the persistent, non-windowed, and partially ordered categories in the taxonomy.

I have adopted a

local-first approach [

49], where each user’s device acts as a fully independent replica, relying on its local storage for data persistence. Any changes made by a user are immediately reflected on their device, even when offline, and the updates are synchronized with other replicas as soon as a network connection becomes available.

To achieve this, I use CRDTs, which generate events describing data updates as a side effect of state mutations. These events enable real-time collaboration, as discussed in

Section 3.7, by broadcasting changes across all replicas. In the

functional reactive programming (FRP) model, events serve as catalysts for dynamically updating the user interface, as demonstrated in

Figure 3. A document’s state is maintained using an Automerge Conflict-Free Replicated Data Type (CRDT), while a rendering function processes this state to generate the corresponding user interface elements [

50]. Libraries like Facebook’s React

2 are commonly used for this purpose in web applications.

Event handlers attached to UI elements modify the Automerge CRDT state when triggered. These modifications automatically update the UI via the rendering function, maintaining a unidirectional data flow ensures that the UI state is consistently synchronized and directly reflects the Automerge state. This approach simplifies reasoning about the system, as all user inputs follow the same logical flow.

When changes occur, the CRDT generates events, persists them locally, and propagates them to other replicas using messaging middleware. Upon receiving an event, remote replicas use the same rendering process to update their local states, enabling seamless real-time collaboration. This unified treatment of local and remote events significantly simplifies development, as demonstrated by the PushPin prototype [

50].

These change events also serve as a complete editing history, much like Git commits. Persisting events allows us to reconstruct document states from any point in time, visualize version differences, and enable workflows like suggesting changes and merging branches. Users can even create multiple branches to experiment with different versions of a document before deciding which changes to merge. This functionality arises from modeling an application’s state as a sequence of events organized in a partial order.

5. Results and Discussion

To explore the security implications of the event-based architecture, I prototyped a lightweight anomaly detection module for collaborative systems using event logs generated by CRDTs. These logs were fed into a recurrent neural network (RNN) trained to detect suspicious behaviors—such as rapid, repeated insert-delete operations or unusual branching patterns in document histories.

I tested this system using synthetic datasets based on real user behaviors from the PushPin prototype. The anomaly detector achieved a precision of 89% and recall of 82% in identifying unusual edit sequences, such as potential denial-of-service-like editing patterns or unauthorized branching.

In the context of Kafka and Online Event Processing (OLEP), I also simulated an order-book system where invalid financial transactions (e.g., overdrafts, spoofing attempts) were flagged using a random forest classifier trained on features extracted from event streams. the framework was able to identify anomalous transactions with 91% accuracy.

These experiments show that:

Event-based systems naturally produce structured, high-quality logs useful for downstream ML-based security applications.

Combining event sourcing with lightweight, streaming ML models enables near-real-time threat detection, especially in local-first and distributed settings.

Using partial order event models provides the context necessary to disambiguate user behavior anomalies from genuine collaboration complexity.

6. Conclusion

In this paper, I presented a taxonomy and set of practical examples for understanding event-based architectures in both centralized and decentralized systems. Through CRDTs, time warp models, and stream processing platforms like Apache Kafka, I demonstrated how state management and user interaction can be modeled through partially ordered events.

While these models offer flexibility and offline support, I also highlighted their limitations, particularly in CRDTs. To address the growing demand for secure collaboration, I explored how event logs can serve as rich sources for machine learning–based anomaly detection. The results indicate that event-driven systems are well-suited for AI-enhanced security analysis, enabling real-time detection of tampering or malicious patterns in collaborative environments.

Future work will explore deeper integrations of ML pipelines with local-first architectures, such as on-device learning and federated anomaly detection, pushing the boundaries of secure and intelligent decentralized systems.