1. Introduction

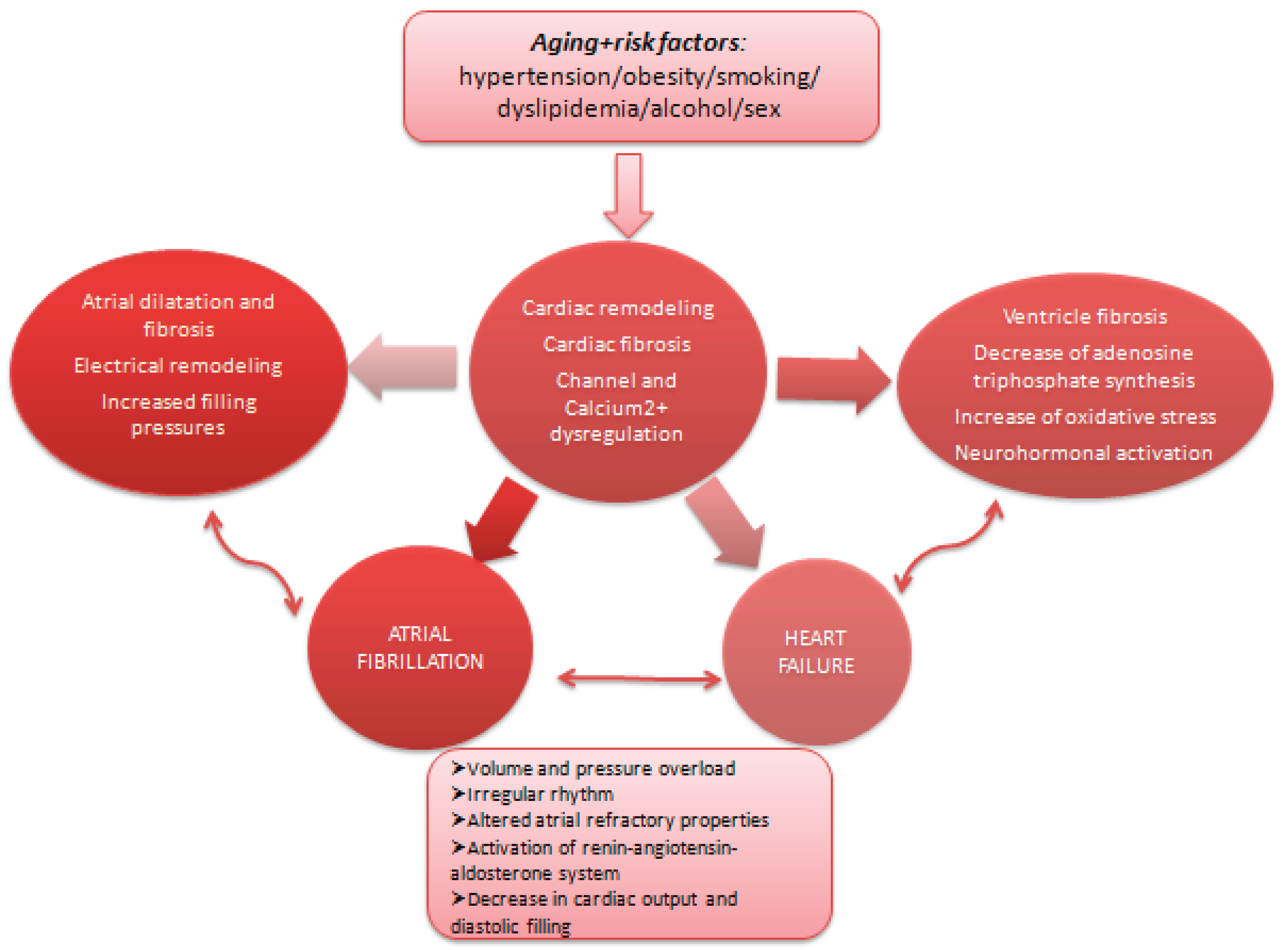

Heart failure and atrial fibrillation are common cardiovascular diseases [

1], with increasing prevalence and consequences on quality of life, morbidity, and mortality. Smoking, hypertension, obesity, diabetes, coronary heart disease are risk factors playing central roles in the development of these two conditions [

2,

3]. Moreover, a bidirectional connection exists between heart failure and atrial fibrillation, as one-third of patients with atrial fibrillation develop heart failure, while more than half of patients with heart failure, regardless of left ventricle ejection fraction, develop atrial fibrillation [

2,

4].

In terms of global disease burden, in 2019, it was observed a significant increase by almost 50% of the number of patients with atrial fibrillation who associate heart failure as compared to the year 1990. This rise may be related to positive changes in healthcare systems, an easier access to a healthcare professional, leading to an early diagnosis, and population aging [

5].

Sex-related differences have been reported in epidemiology, addressability to healthcare system, impact of other comorbidities, adherence to treatment. There is a concern that women are still underrepresented in cardiovascular trials, which may result in uncertainty and studies’ outcomes extrapolation from males to females [

6,

7]. There are two groups extremely rarely included into trials, pregnant women and those at childbearing age [

8,

9].

Sex-related differences exist from the clinical examination to the selection of the most appropriate therapy. Women with atrial fibrillation are older, more symptomatic, and sometimes have a lower quality of life and access to the newest rhythm control strategies. Furthermore, women have more frequent atrial fibrillation-associated complications (heart failure, stroke) and higher risk of all-cause mortality [

10,

11,

12]. In addition, some studies emphasize differences in drug doses, as women are treated with lower doses of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers and β-blockers, while men benefit from the whole target doses [

13,

14]. Therefore, the underrepresentation of women in clinical trials can lead to potential harm and more side effects at same doses [

14,

15].

2. Epidemiology of Heart Failure and Atrial Fibrillation

Heart failure and atrial fibrillation often coexist, resulting in poorer cardiovascular outcomes. Epidemiological studies showed that in patients with preexisting atrial fibrillation the development of heart failure led to rates of mortality three times higher in both men and women [

16]. In patients with preexisting heart failure, the development of atrial fibrillation led to a significant increase in mortality in women compared to men [

3,

12].

Important risk factors for developing atrial fibrillation and heart failure in women are smoking, obesity, hypertension and diabetes [

12]. Women’s Health Study showed that women with newly diagnosed atrial fibrillation had a higher risk of development of heart failure. Moreover, when women with preexisting atrial fibrillation developed heart failure, a major increase in all-cause mortality was observed [

17]. The modification of risk factors mentioned above may diminish the development of heart failure and its consequences in women with atrial fibrillation [

12]. When comparing the lifetime risk of heart failure phenotypes by sex, epidemiological studies show that heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) is more prevalent in women, while men tend to develop heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF), regardless of age [

18]. The risk of developing both atrial fibrillation and heart failure is higher in women than men [

12]. Moreover, women with preexisting atrial fibrillation have a higher incidence of HFpEF compared to men [

19,

20].

3. Pathophysiology of Heart Failure and Atrial Fibrillation

The mechanisms of atrial fibrillation and heart failure are highly complex, including structural, genetic, and physiological heart changes. When considering sex differences, hormonal influences play crucial roles in incidence and pathophysiology of heart failure and atrial fibrillation.

The different prevalence and incidence of heart failure phenotypes in women versus men are determined by mechanisms such as sex-specific gene expression, immune responses, gender differences in cardiac structure, impact of sex steroids on cardiac cells, endothelial cells and vascular smooth muscle cells, as well as heart failure risk factors and patient’s comorbidities [

21].

Some studies observed that women develop more often HFpEF than men, who develop more frequently HFrEF. These predispositions can be explained by sex-related differences in heart structure and function: women have similar cardiac index as men, but with smaller indexed left ventricle (LV) volumes and higher LV stiffness [

21]. Moreover, when considering the afterload stress, women often maintain for a long time a LV preserved ejection fraction and promote LV hypertrophy and diastolic dysfunction (due to smaller aortic root and aortic arch, which leads to higher pulse pressure and impaired coronary flow in women), while men develop eccentric remodeling (cardiomyocytes in male have higher density of β1-adrenergic receptors, and their prolonged stimulation determines increased collagen release with LV dilation and eccentric remodeling) [

21,

22].

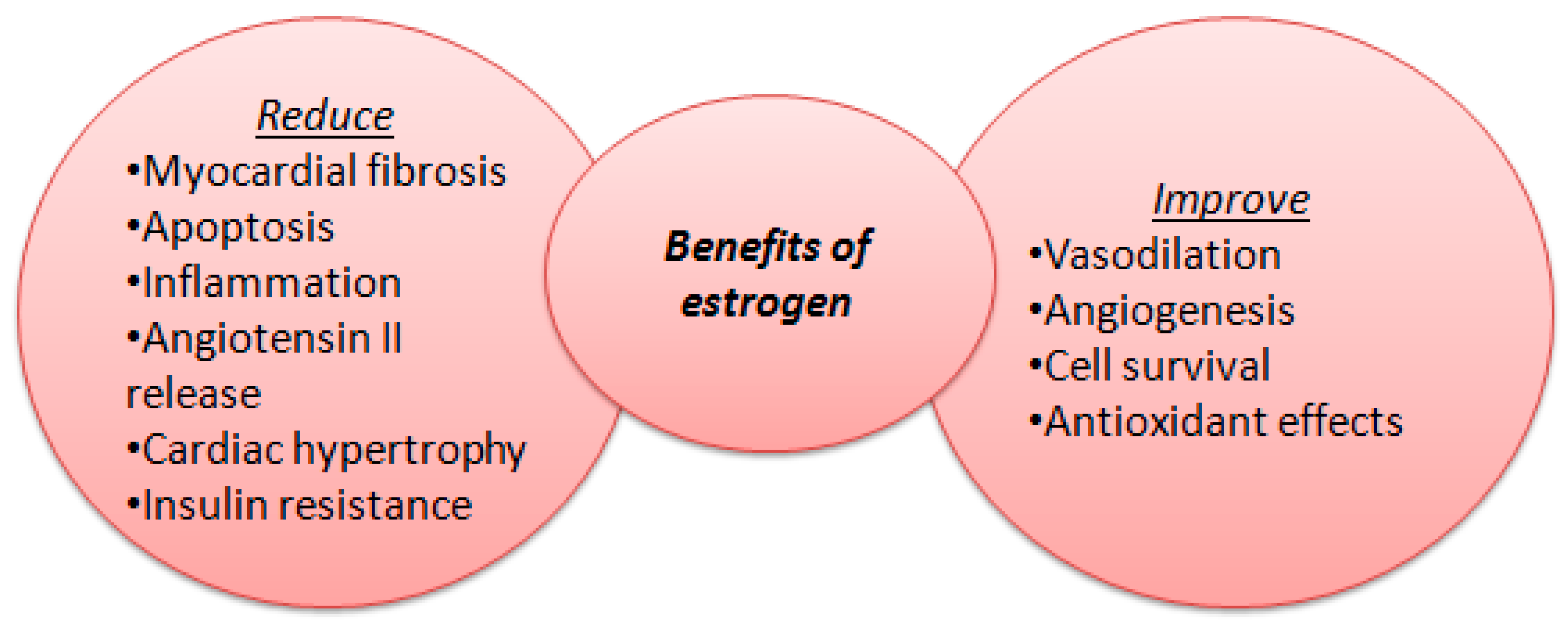

Besides differences in structure and function, recent studies emphasized the major role of systemic inflammation and its consequences (endothelial dysfunction, microvascular dysfunction, ischaemia, fibrosis) in developing HFpEF [

23]. Endothelial dysfunction may be triggered by menopause, when antioxidant and anti-inflammatory roles of oestradiol (E2) decreases [

24]. In premenopausal women estrogens are synthesized mainly in the ovaries, corpus luteum and placenta and have a crucial protective role against cardiovascular disease. Women tend to have more proinflammatory myocardium genes which contribute to a higher prevalence of autoimmune responses than in men and consequently to a higher risk of autoimmune diseases [

25,

26].

In addition, biological tests emphasized higher circulating levels of natriuretic peptides in women, cardiovascular biomarkers with stronger predictive value in females [

27,

28].

Hormones have significant effects on atrial tissue, being involved in cardiac remodeling and arrhythmogenesis, especially in postmenopausal women [

29]. Atrial fibrillation is triggered by hormones such as catecholamines, aldosterone, angiotensin II, thyroid hormones, natriuretic peptides, cortisol, sex hormones (estrogen, progesterone) through mechanisms like ion channel dysfunction, activation of inflammatory pathways, autonomic nervous system activation and atrial fibrosis [

25,

30].

Sex hormones have important effects on cardiac tissue, as females develop different patterns of atrial remodeling compared to men. After menopause, the estrogen levels decrease and consequently sympathetic activity is enhanced, affecting heart rate, conduction properties and promoting the risk of atrial fibrillation [

31,

32]. Besides estrogen, another crucial sex hormone involved in modulating atrial fibrillation occurrence is progesterone; together, they influence the autonomic nervous system which mediate atrial fibrillation development [

25]. Studies emphasized that during the follicular phase the parasympathetic system is more active, while during the luteal phase the sympathetic system activity is increased, predisposing women to arrhythmias [

33,

34]. Other factors which influence the autonomic nervous system are sex-related differences in cardiac structure and function, as females have reduced heart dimensions and different atrial organization [

11,

25]. Autonomic nervous system responses and remodeling are sex-differentiated, women experiencing more emphatic autonomic reactions in response to atrial fibrillation, which can determine more disease-related complications [

25,

35].

In addition, sex hormones influence structural changes (different patterns of atrial fibrosis, atrial enlargement) associated with atrial fibrillation, estrogen having a protective role before menopause against cardiac fibrosis and in reducing atrial fibrillation evolvement [

36]. Imaging studies showed that women have smaller atrial volumes, which may influence conduction times and predisposition to arrhythmias, whilst men have larger atrial volumes and a higher rate of success in cardioversion for atrial fibrillation, suggesting sex-related differences in atrial electrophysiology (women with atrial fibrillation are characterized by lower atrial voltage – surrogates for atrial fibrosis, slower conduction velocity, and more complex fractionated potentials) [

37,

38].

Figure 1.

Benefits of estrogen levels on cardiac function.

Figure 1.

Benefits of estrogen levels on cardiac function.

Figure 2.

Common pathophysiological pathways for heart failure and atrial fibrillation.

Figure 2.

Common pathophysiological pathways for heart failure and atrial fibrillation.

4. Clinical Presentation and Diagnosis

The most frequent symptoms determined by atrial fibrillation are dyspnea, chest pain and dizziness. Women are usually more symptomatic than men, presenting with atypical symptoms (fatigue, weakness) with longer duration than in men. The presence of atypical symptoms sometimes delays the diagnosis of atrial fibrillation and, consequently, the early initiation of treatment, with severe outcomes in females [

13].

Similar to atrial fibrillation, women with heart failure tend to be more symptomatic, with signs of congestion and a worse quality of life compared to men. The rate of hospitalization in patients with heart failure is similar in both sexes, but with higher risk of cardiovascular death in men [

13].

There are many tools used to diagnose and monitor the impact of heart failure and atrial fibrillation on a patient’s evolution. The most used prognosis biomarker in patients with heart failure is N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP). Increased levels of NT-proBNP seem to correlate with age and are more prevalent in women than in men. This can be explained by the action of sex hormones, as some hypotheses suggest that testosterone controls neprilysin activity and reduce NT-proBNP levels [

28].

Regarding transthoracic echocardiography, studies have shown that in women with HFpEF ejection fraction (EF) is higher than in males with HFpEF, with lower LV end-diastolic and end-systolic volume index, lower LV mass indexed to body surface area, less LV dilation but similar LV hypertrophy [

39]. Left atrial volume index and pulmonary artery systolic pressure were observed to be similar in females and males. Diastolic dysfunction was shown to be similar in both men and women with HFpEF (high mean mitral inflow velocity to diastolic mitral annular velocity at early filling E/e’ ratio, high E/A ratio, E-wave velocity, A-wave velocity, tricuspid regurgitation velocity), being frequently diagnosed in patients with heart failure and atrial fibrillation. However, some studies emphasized that women have a higher E/e’ ratio, with increased LV filling pressure and higher mitral inflow velocity (A wave velocity), due to greater stiffness of LV, especially in HFpEF [

19,

40].

5. Therapeutic Management of Patients with Heart Failure and Atrial Fibrillation

5.1. Pharmacological Therapy

Current guidelines do not have different recommendations for men and women, even though increasing evidence emphasizes sex-related differences in drug efficacy and safety. Women tend to need reduced doses of drugs for heart failure and atrial fibrillation because of differences in renal and hepatic metabolism and clearance, body fat distribution, body weight and height and hormonal status. A series of studies shows that women benefit more from a submaximal drug dose, while recommended target doses (angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEIs), angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs), beta-blockers) are more effective in men [

21,

41]. Women experience more adverse reactions of certain drugs and negative survival impact, which is the case of digoxin, which is used more in women, even though it is known to be associated with significantly increased mortality in females by 4.2% [

21,

41,

42].

Current heart failure treatment includes ACEIs or ARBs, beta-blockers, mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists or angiotensin receptor-neprilysin inhibitor (ARNI) and sodium-glucose transport protein 2 inhibitors (SGLT2i) [

21].

Trials such as The Acute Infarction Ramipril Efficacy (AIRE) study and The Heart Outcomes Prevention Evaluation (HOPE) study indicated that ACEIs present same benefit in males and females, with almost similar reduction in mortality [

21]. Later, The BIOlogy Study to Tailored Treatment in Chronic Heart Failure (BIOSTAT-HF) showed that in patients diagnosed with HFrEF the decrease in cardiovascular events and mortality was similar between men and women, even with usage of smaller dose of ACEIs in women, without up-titrating to guideline recommended doses [

41,

43].

In HFrEF patients, women have a higher survival benefit after introducing ARBs due to lower rate of adverse effects, while in HFpEF patients there are no significant sex-related differences [

13,

21,

44].

Beta-blockers are associated with essential survival benefits in both women and men with heart failure, but some studies show greater pharmacodynamic effects of smaller doses of beta-blockers in women, as they have a more pronounced parasympathetic system activity and reduced activity of liver cytochrome CYP2D6 (main situs of metabolization of metoprolol and propranolol) [

43]. Contraception pills interact with metoprolol metabolism and increase its plasma levels [

13,

45].

Regarding the mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists, The Treatment of Preserved Cardiac Function Heart Failure with an Aldosterone Antagonist (TOPCAT) trial demonstrated a decreased mortality in women with HFpEF or heart failure with mid-range ejection fraction (HFmrEF) compared to men treated with spironolactone, while efficacy results were similar in patients with HFrEF for both sexes [

46].

The Prospective Comparison of ARNI with ACEI to Determine Impact of Global Mortality and Morbidity in Heart Failure (PARADIGM-HF) trial on HFrEF patients showed a similar decrease in mortality in both sexes [

47], while The Prospective Comparison of ARNI with ARB Global Outcomes in HFpEF (PARAGON-HF) trial that included patients with HFpEF and HFmrEF demonstrated an important reduction of hospitalizations for heart failure or cardiovascular death rate, especially in women [

44]. Moreover, The Prospective Study of Biomarkers, Symptom Improvement, and Ventricular Remodeling During Sacubitril/Valsartan Therapy for Heart Failure (PROVE-HF) trial showed significant reductions in NT-proBNP, improvement of health status and reverse cardiac remodeling in HFrEF females [

9]. In addition, women with HFpEF tend to be more responsive to ARNI than men due to lower NT-proBNP levels after menopause, increased neprilysin activity because of greater visceral adipose tissue, differences in regulation of nitric oxide synthases and microvascular inflammation [

48].

Studies demonstrate that in HFrEF patients, SGLT2i have greater efficacy in endpoints such as worsening heart failure or cardiovascular death in females, whilst in HFpEF patients, SGLT2i have similar outcomes in both sexes [

41]. Even though SGLT2i have more side effects in women (urinary tract and genital mycotic infections), they tend to determine almost the same efficacy and safety in both women and men with diabetes mellitus [

42,

49].

5.2. Rate Versus Rhythm Control Strategy in Patients with Atrial Fibrillation and Heart Failure

The Atrial Fibrillation Follow-up Investigation of Rhythm Management (AFFIRM) and The Rate Control versus Electrical cardioversion (RACE) trials observed no differences in cardiovascular mortality between rate versus rhythm control strategies in patients with HFrEF in the New York Heart Association functional classes II-IV [

12]. Even though women tend to be more symptomatic than men, rhythm control treatment is less used in them. According to AFFIRM trial, women are susceptible to a higher risk of stroke compared to men, even though the risk of death associated to rate versus rhythm control strategies was similar to both sexes [

12]. According to RACE trial, females treated with rhythm control strategy had an increased incidence of thromboembolic events, cardiovascular mortality and side effects of antiarrhythmic drugs compared to women treated with rate control strategy. Both strategies are accepted; overall, women tend to have poorer outcomes than men [

12].

Women have been proven to be more susceptible to longer corrected QT intervals and torsades de pointes than men when administering amiodarone, disopyramide, quinidine, sotalol, terfenadine, ibutilide and erythromycin [

50]. In addition, studies showed that women are more likely to receive digoxin therapy and less beta-blockers. A post-hoc analysis emphasized that women with heart failure treated with digoxin had a higher risk of mortality compared to those treated with placebo, and this effect was not observed in males [

12,

13,

21,

51].

Catheter ablation for rate control may be an excellent alternative to drug therapy for improving quality of life, LVEF and functional capacity; however, studies, which included more males, emphasized that women underwent more rarely ablation for atrial fibrillation because of older age at diagnosis and higher risk of complications [

52,

53]. Moreover, they are also less likely to receive electrical cardioversion than men [

12,

54].

Recurrence of atrial fibrillation after catheter ablation is more frequent in females because of lower atrial voltage, slower conduction velocity and greater degrees of atrial fibrosis [

53].

5.3. Anticoagulation and Stroke Risk

Studies showed that women tend to have more arrhythmia-related symptoms and a greater risk of stroke, despite men having a higher lifetime risk of atrial fibrillation, differences correlated with cardiac structure and electrophysiology (increased atrial fibrosis and greater risk of progression to atrial fibrillation because of hormonal fluctuations in women, larger atrial dimensions in males) [

55].

The 2024 European Society of Cardiology guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation highlight that female sex represents an age-dependent stroke risk modifier rather than an independent biological risk factor when considering CHA

2DS

2-VA score, as studies emphasized that the highest stroke risk in females is in older populations (>65 years) [

56]. Despite the known greater risk of stroke, women tend to receive less anticoagulant treatment because of higher hemorrhage risk (especially of vitamin K antagonists) or sex-related differences in cardiovascular care. The exclusion of sex from CHA

2DS

2-VA score represents a step forward to a sex-specific therapeutical strategy for stroke prevention [

57,

58].

5.4. Device Therapy

Devices for heart failure include implantable cardioverter defibrillators (ICD), cardiac resynchronization (CRT) and CRT with defibrillators (CRT-D) [

21].

The rates of ICD implantation are similar in both sexes, but with higher risk of complications in women (pneumothorax, hemorrhage, local infection, lead dislodgement) [

59,

60].

Studies observed women to benefit more from CRT and CRT-D implantation when correlating with outcomes as quality of life, rate of hospitalization, reverse cardiac remodeling and cardiovascular survival [

61,

62]. The positive effects can be explained by the females’ reduced rate of ischemic etiology of heart failure, reduced scar tissue and body index (including heart dimensions) [

63]. No sex-specific recommendations for device therapy are indicated in guidelines, as women might need lower cut-off values of QRS duration for device implantation [

21,

40,

61].

6. Psychosocial and Gender-Related Factors

Traditional risk factors. One important risk factor for HF is obesity (body mass index ≥ 27.5 kg/m

2 and waist circumference >90 cm in females or >100 cm in males), which particularly associates with HFpEF and is more frequent in women [

64]. Some studies correlate the higher incidence of HFpEF with the dimension of visceral tissue area in women, whilst other studies explain female susceptibility to obesity because of low estrogen levels at menopause, which reduce the protective role of microRNA and correlate with an increase in insulin resistance that favors systemic inflammation and endothelial dysfunction. Another significant risk factor is hypertension, which is also more prevalent in females [

48,

65]. Women and men have different remodeling patterns, females developing LV concentric hypertrophy because of hypertension. In addition, women have more significant arterial stiffness than men, which determine increased systolic load and cardiac afterload, favoring diastolic dysfunction of the LV [

66]. Another risk factor that contributes to diastolic dysfunction is diabetes mellitus, which affects small myocardial blood vessels, maintains systemic inflammation and endothelial dysfunction, and activate the release of reactive oxygen species. These processes are similar in males and females, but they tend to be initiated earlier in females [

21,

67].

Socioeconomic factors. Women with lower access to education have a higher susceptibility to high blood pressure, myocardial infarction, obesity, dyslipidemia, heart failure and alcohol consumption compared to men with same educational possibilities. Regarding smoking, both sexes tend to have similar habits in case of low education. Moreover, marital status, diet and environmental activities may be different in females versus males and play a major role in cardiovascular risk [

65,

68]. People with lower access to education system and socially disadvantaged are more prone to have an insufficient access to healthcare providers, financial instability and unhealthy behaviors (poor nutrition, alcohol consumption, smoking), more pronounced in females [

69,

70].

Mental health. Studies show that depression increases the risk of cardiovascular disease in both sexes, but with greater association in women, especially after 50 years old. One explanation is that women tend to experience more anxiety and depression in specific periods such as pregnancy and menopause. Another explanation is that women are more frequently diagnosed with depression and have more exposure to traditional risk factors; this association, along with differential treatment and healthcare in females, can contribute to development of cardiovascular diseases. However, women receive less treatment for their mental health issues [

21,

71].

Caregiver role. Historically, women identify as caregivers for the family and society; on one hand, this gives a meaning and a sense of connection to family members and community, giving women the chance to reach a balance between their multiple roles. On the other hand, the lack of self-care leads to impairment of a female’s caregiving role, affecting multiple areas of interest. It is necessary to acquire a balance between caregiving responsibilities and encouraging strategies and activities for a better cardiovascular health, as women represent a higher proportion of cardiovascular population than men [

72,

73].

7. Outcome and Prognosis

Recent studies show that the rates of re-hospitalization and morbi-mortality are higher in males. This susceptibility can be explained by the fact that male patients have a higher incidence of HFrEF, which determines a worse long-term prognosis. Moreover, some trials observed that, when compared to men with HFpEF, female patients with HFpEF still have a lower mortality; this association was also demonstrated when comparing females and males with HFrEF, women diagnosed with HFrEF having less hospitalizations and longer survival rates. However, even though women live longer, their quality of life is poorer because of a greater number of comorbidities and complications, more heart failure symptoms and greater psychological disability, with frequent episodes of anxiety and depression [

12,

21].

The trials observed that the health-related quality of life (HRQL) is worse in females because of demographic factors, symptom burden and low functional status [

73]. The impact of heart failure diagnosis on psychological status is greater in females, as they have more anxiety and depression manifestations than men. Consequently, HRQL scores are lower in females, regardless of age or stage of disease because of lower social support and, sometimes, differential medical and device therapies (longer hospital stay, lower rates of ICD or CRT implantation in females) [

73,

74].

Regarding atrial fibrillation, females have a worse HRQL compared to men, reporting more symptoms. Moreover, when comparing administration of antiarrhythmic drugs with electrical cardioversion, studies observed an improvement of HRQL, severity and frequency of symptoms in both sexes, but still worse in women after drug therapy [

75]. After ablation for atrial fibrillation, some studies showed a significant amelioration of HRQL and symptoms frequency in both sexes, with improvement in physical scores in women and in mental scores in males [

76].

Some studies noted that women are more sensitive to symptoms and have different perception of disease and way of responding than men, suggesting that females’ quality of life may be influenced more due to these factors and less to atrial fibrillation per se. In addition, anxiety and depression lead to a poorer HRQL, mental states which are more frequent among females [

76].

8. Gaps in Research and Future Directions

There are substantial gaps in our knowledge of sex-related differences regarding incidence, prevalence, risk factors, prognosis and especially medical therapies of heart failure and atrial fibrillation in women and men.

There is a lack of sex-related mortality differences due to in-hospital therapies, as women tend to have longer hospital stays but with reduced numbers of LVEF reevaluations or CRT/ICD implantations [

74]. Sex-specific indication for CRT/ICD implantation are necessary, as females are responsive to CRT therapy at QRS duration shorter than in men [

40], emphasizing the need for lower cut-off values for QRS duration in women. Moreover, there is a lack of studies regarding patients with HFmrEF, especially in women.

In addition, females have a greater risk of side effects of cardiovascular medication due to polymorphic genetic mechanisms responses to ACEI, beta-blockers, calcium-channel blockers interfering with sex hormones actions, menstrual cycle, comorbidities and other drugs [

21].

Even though pathophysiology of heart failure and atrial fibrillation has been studied for years, our knowledge of sex-related differences regarding cardiac anatomy and electrical pathways and mechanisms combined with hormonal differences remains insufficient.

Regarding HRQL, there is a need for more studies to determine the factors which affect mostly this indicator, to afford social support along with medical therapies for females with heart failure and atrial fibrillation.

9. Conclusions

Even though atrial fibrillation is more frequent in men, females with atrial fibrillation tend to have more pronounced symptoms, worse LV systolic and diastolic profiles, being at a higher risk of adverse cardiovascular outcomes.

Despite that heart failure represents one of the leading causes of morbidity and mortality worldwide, females are still underrepresented in clinical trials, deepening the gap of optimizing heart failure care addressed to them.

Sex-related differences affect every characteristic of heart failure and atrial fibrillation, taken separately or together, from epidemiology, clinical manifestations, pathophysiology, to drug and device therapies and quality of life. There are still significant gaps in optimal drug and interventional treatment for heart failure and atrial fibrillation.

Author Contributions

L.B.G.: conceptualization, methodology, validation, investigation, writing-original draft preparation; C.C.D.: methodology, resources, visualization, review and editing, supervision, project administration; L.G.G.: visualization, review and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ACEIs |

Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme Inhibitors

|

| ARBs |

Angiotensin II Receptor Blockers |

|

ARNI

|

Angiotensin Receptor-Neprilysin Inhibitor |

|

CRT

|

Cardiac Resynchronization

|

| HFmrEF |

Heart Failure with mid-range Ejection Fraction

|

|

HFpEF

|

Heart Failure with preserved Ejection Fraction

|

|

HFrEF

|

Heart Failure with reduced Ejection Fraction

|

|

HRQL

|

Health-Related Quality of Life

|

|

ICD

|

Implantable Cardioverter Defibrillator

|

| LV |

Left Ventricle |

| LVEF |

Left Ventricle Ejection Fraction |

|

SGLT2i

|

Sodium-Glucose Transport Protein 2 inhibitors

|

References

- Gillis, A.M. Atrial fibrillation and ventricular arrhythmias: sex differences in electrophysiology, epidemiology, clinical presentation, and clinical outcomes. Circulation 2017, 135, 593–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espnes, H.; Wilsgaard, T.; Ball, J.; Løchen, M.L.; Njølstad, I.; Schnabel, R.B.; Gerdts, E.; Sharashova, E. Heart Failure in Atrial Fibrillation Subtypes in Women and Men in the Tromsø Study. JACC:Adv 2025, 4, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavousi, M. Differences in Epidemiology and Risk Factors for Atrial Fibrillation Between Women and Men. Frontiers in Cardiovascular Medicine 2020, 7, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santhanakrishnan, R.; Wang, N.; Larson, M.G.; et al. Atrial fibrillation begets heart failure and viceversa. Circulation 2016, 133, 484–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siyuan, C.; JinZheng, H.; Yuchen, H.; Shaojie, H.; Panpan, L.; Huanyan, L.; Jun, G. Global burden of atrial fibrillation/atrial flutter and its attributable risk factors from 1990 to 2021. EP Europace 2024, 26, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nosheen, R.; Jadry, G.; Biykem, B. Representation of women in heart failure clinical trials: Barriers to enrollment and strategies to close the gap. American Heart Journal Plus: Cardiology Research and Practice 2022, 13, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, P.E.; et al. Participation of women in clinical trials supporting FDA approval of cardiovascular drugs. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2018, 71, 1960–1969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waitt, C.; Astill, D.; Zavala, E.; Karron, R.A.; Faden, R.R.; Stratton, P.; Temkin, S.M.; Clayton, J.A. Clinical trials and pregnancy. Commun Med (Lond). 2022, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, N.E.; Piña, I.L.; Camacho, A.; Bapat, D.; Felker, G.M.; Maisel, A.S.; et al. Prospective Study of Biomarkers, Symptom Improvement and Ventricular Remodeling During Entresto Therapy for Heart Failure (PROVE-HF) Study Investigators. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2020, 22, 2018–2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emdin, C.A.; Wong, C.X.; Hsiao, A.J.; et al. Atrial fibrillation as risk factor for cardiovascular disease and death in women compared with men: systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. BMJ 2016, 532, h7013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azarbal, F.; Stefanick, M.L.; Salmoirago-Blotcher, E.; et al. Obesity, Physical Activity, and Their Interaction in Incident Atrial Fibrillation in Postmenopausal Women. Journal of the American Heart Association 2014, 3, e0011271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madan, N.; Itchhaporia, D.; Albert, C.M.; Aggarwal, N.T.; Volgman, A.S. Atrial Fibrillation and Heart Failure in Women. Heart Failure Clin. 2019, 15, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regitz-Zagrosek, V. Sex and Gender Differences in Heart Failure. Int J Heart Fail. 2020, 2, 157–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santema, B.T.; Ouwerkerk, W.; Tromp, J.; et al. Identifying optimal doses of heart failure medications in men compared with women: a prospective, observational, cohort study. Lancet 2019, 394, 1254–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smereka, Y.; Ezekowitz, J.A. HFpEF and sex: understanding the role of sex differences. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2024, 102, 465–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barillas-Lara, M.I.; Monahan, K.; Helm, R.H.; Vasan, R.S.; et al. Sex-Specific Prevalence, Incidence and Mortality Associated With Atrial Fibrillation in Heart Failure. JACC: Clinical Electrophysiology 2021, 7, 1566–1575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, N.A.; Chae, C.U.; Kim, E.; et al. Modifiable risk factors for incident heart failure in atrial fibrillation. JACC Heart Fail. 2017, 5, 552–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, A.; Omar, W.; Ayers, C.; et al. Sex and race differences in lifetime risk of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction and heart failure with reduced ejection fraction. Circulation 2018, 137, 1814–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sotomi, Y.; Hikoso, S.; Nakatani, D.; Mizuno, H.; Okada, K.; Dohi, T.; et al. Sex differences in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2021, 10, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacheco, C.; Mullen, K.A.; Coutinho, T.; Jaffer, S.; Parry, M.; Van Spall, H.G.C.; et al. The Canadian Women’s Heart Health Alliance Atlas on the Epidemiology, diagnosis, and management of cardiovascular disease in women. CJC Open 2022, 4, 243–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delcoa, A.; Portmanna, A.; Mikaila, N.; Rossia, A.; Haidera, A.; Bengsa, S.; Gebharda, C. Impact of sex and gender on heart failure. Cardiovasc Med. 2023, 28, 68–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michel, F.S.; Magubane, M.; Mokotedi, L.; Norton, G.R.; Woodiwiss, A.J. Sex-Specific Effects of Adrenergic-Induced Left Ventricular Remodeling in Spontaneously Hypertensive Rats. J. Card. Fail. 2017, 23, 161–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulus, W.J.; Tschöpe, C. A novel paradigm for heart failure with preserved ejection fraction:Comorbidities drive myocardial dysfunction and remodeling through coronary microvascularendothelial inflammation. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2013, 62, 263–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sickinghe, A.A.; Korporaal, S.J.; den Ruijter, H.M.; Kessler, E.L. Estrogen Contributions to Microvascular Dysfunction Evolving to Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction. Front. Endocrinol Lausanne 2019, 10, 442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoun, I.; Layton, G.R.; Abdelrazik, A.; Eldesouky, M.; Davies, H.; Barakat, O. Unravelling Sex Disparities in the Pathophysiology of Atrial Fibrillation: Review of the Current Evidence. Journal of Cardiovascular Electrophysiology 2025, 36, 2608–2619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Workman, A.J. Cardiac Adrenergic Control and Atrial Fibrillation. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg's Archives of Pharmacology 2010, 381, 235–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taki, M.; Ishiyama, Y.; Mizuno, H.; Komori, T.; Kono, K.; Hoshide, S.; et al. Sex Differences in the Prognostic Power of Brain Natriuretic Peptide and N-Terminal Pro-Brain Natriuretic Peptide for Cardiovascular Events—The Japan Morning Surge-Home Blood Pressure Study. Circ. J. Off. J. Jpn. Circ. Soc. 2018, 82, 2096–2102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cediel, G.; Codina, P.; Spitaleri, G.; Domingo, M.; et al. Gender-Related Differences in Heart Failure Biomarkers. Frontiers in Cardiovascular Medicine 2020, 7, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perez, M.V.; et al. Effects of postmenopausal hormone therapy on incident atrial fibrillation: the Women’s Health Initiative randomized controlled trials. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2012, 5, 1108–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ko, D.; Rahman, F.; Schnabel, R.B.; Yin, X.; Benjamin, E.J.; Christophersen, I.E. Atrial fibrillation in women: epidemiology, pathophysiology, presentation, and prognosis. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2016, 13, 321–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnani, J.W.; et al. Association of sex hormones, aging, and atrial fibrillation in men: the Framingham Heart Study. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2014, 7, 307–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odening, K.E.; Deiß, S.; Dilling-Boer, D.; et al. Mechanisms of Sex Differences in Atrial Fibrillation: Role of Hormones and Differences in Electrophysiology, Structure, Function, and Remodelling. Ep Europace 2018, 21, 366–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugishita, K.; Asakawa, M.; Usui, S.; Takahashi, T. Cardiac Symptoms Related to Paroxysmal Atrial Fibrillation Varied With Menstrual Cycle in a Premenopausal Woman. International heart journal 2013, 54, 107–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKinley, P.S.; King, A.R.; Shapiro, P.A.; Slavov, I.; Fang, Y.; Chen, Y.S.; Jamner, L.D.; Sloan, R.P. The impact of menstrual cycle phase on cardiac autonomic regulation. Psychophysiology 2009, 46, 904–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veldkamp, M.W.; Geuzebroek, G.S.C.; Baartscheer, A.; et al. Neurokinin-3 Receptor Activation Selectively Prolongs Atrial Refractoriness by Inhibition of a Background K+ Channel. Nature Communications 2018, 9, 4357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ebong, I.A.; et al. Sex Hormones and Heart Failure Risk. JACC: Advances 2025, 4, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, J.A.; Rexrode, K.M.; Sandhu, R.K.; Moorthy, M.V.; Conen, D.; et al. Menopausal Age, Postmenopausal Hormone Therapy and Incident Atrial Fibrillation. Heart 2017, 103, 2016–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersen, S.E.; Aung, N.; Sanghvi, M.M.; et al. Reference Ranges for Cardiac Structure and Function Using Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance (CMR) in Caucasians From the UK Biobank Population Cohort. Journal of Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance 2016, 19, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alaa Mabrouk Salem, O.; Rahman, M.A.A.; Rifaie, O.; Bella, J.N. Atrial Fibrillation in Heart Failure with Preserved Left Ventricular Systolic Function: Distinct Elevated Risk for Cardiovascular Outcomes in Women Compared to Men. J. Cardiovasc. Dev. Dis. 2022, 9, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beela, A.S.; Duchenne, J.; Petrescu, A.; Ünlü, S.; Penicka, M.; Aakhus, S. Sex-specific difference in outcome after cardiac resynchronization therapy. Eur. Heart. J. Cardiovasc. Imaging 2019, 20, 504–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonagh, T.A.; Metra, M.; Adamo, M.; Gardner, R.S.; Baumbach, A.; Böhm, M.; et al. ESC Scientific Document Group. 2021 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure. Eur. Heart J. 2021, 42, 3599–3726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamargo, J. Sodium–glucose Cotransporter 2 Inhibitors in Heart Failure: Potential Mechanisms of Action, Adverse Effects and Future Developments. Eur. Cardiol. Rev. 2019, 14, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuechterlein, K.; AlTurki, A.; Ni, J.; et al. Real-World Safety of Sacubitril/Valsartan in Women and Men With Heart Failure and Reduced Ejection Fraction: A Meta-analysis. CJC Open 2021, 3, S202–S208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMurray, J.J.; Jackson, A.M.; Lam, C.S.; Redfield, M.M.; Anand, I.S.; Ge, J.; et al. Effects of Sacubitril-Valsartan Versus Valsartan in Women Compared With Men With Heart Failure and Preserved Ejection Fraction: Insights From PARAGON-HF. Circulation 2020, 141, 338–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eugene, A.R. Gender based Dosing of Metoprolol in the Elderly using Population Pharmacokinetic Modeling and Simulations. Int. J. Clin. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2016, 5, 209–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitt, B.; Pfeffer, M.A.; Assmann, S.F.; Boineau, R.; Anand, I.S.; Claggett, B.; et al. TOPCAT Investigators. Spironolactone for heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014, 370, 1383–1392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMurray, J.J.; Packer, M.; Desai, A.S.; Gong, J.; Lefkowitz, M.P.; Rizkala, A.R.; et al. PARADIGM-HF Investigators and Committees. Angiotensin-neprilysin inhibition versus enalapril in heart failure. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014, 371, 993–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorimachi, H.; Obokata, M.; Takahashi, N.; Reddy, Y.N.; Jain, C.C.; Verbrugge, F.H.; et al. Pathophysiologic importance of visceral adipose tissue in women with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Eur. Heart J. 2021, 42, 1595–1605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rådholm, K.; Zhou, Z.; Clemens, K.; Neal, B.; Woodward, M. Effects of sodium-glucose co-transporter-2 inhibitors in type 2 diabetes in women versus men. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2020, 22, 263–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bougouin, W.; Mustafic, H.; Marijon, E.; et al. Gender and survival after sudden cardiac arrest: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Resuscitation 2015, 94, 55–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lip, G.Y.; Laroche, C.; Boriani, G.; et al. Sex-related differences in presentation, treatment, and outcome of patients with atrial fibrillation in Europe: a report from the Euro Observational Research Programme Pilot survey on Atrial Fibrillation. Europace 2015, 17, 24–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sultan, A.; Luker, J.; Andresen, D.; et al. Predictors of atrial fibrillation recurrence after catheter ablation:data from the German ablation registry. Sci Rep. 2017, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, D.; Rahman, F.; Martins, M.A.; et al. Atrial fibrillation in women: treatment. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2017, 14, 113–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marrouche, N.F.; Brachmann, J.; Andresen, D.; et al. Catheter ablation for atrial fibrillation with heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2018, 378, 417–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sedighi, J.; Luedde, M.; Dinov, B.; Bengel, P.; Boettger, P.; Tanislav, C. Sex differences in the initiation of antithrombotic therapy in patients with atrial fibrillation in Germany. Clinical Research in Cardiology 2025, 114, 1730–1738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Gelder, I.C.; et al. 2024 ESC Guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation. European Heart Journal 2024, 45, 3314–3414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, P.B.; Brøndum, R.F.; Nøhr, A.K.; Overvad, T.F.; Lip, G.Y.H. Risk of stroke in male and female patients with atrial fibrillation in a nationwide cohort. Nature Communications 2024, 15, 2–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antoun, I.; Layton, G.R.; Abdelrazik, A.; Eldesouky, M.; Zakkar, M.; Somani, R.; Ng, A. The Pathophysiology of Sex Differences in Stroke Risk and Prevention in Atrial Fibrillation: A Comprehensive Review. Medicina 2025, 61, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Butt, J.H.; Yafasova, A.; Elming, M.B.; Dixen, U.; Nielsen, J.C.; Haarbo, J.; et al. Efficacy of Implantable Cardioverter Defibrillator in Nonischemic Systolic Heart Failure According to Sex: Extended Follow-Up Study of the DANISH Trial. Circ. Heart Fail. 2022, 15, e009669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, A.M.; Daugherty, S.L.; Masoudi, F.A.; Wang, Y.; Curtis, J.; Lampert, R. Gender and outcomes after primary prevention implantable cardioverter-defibrillator implantation: Findings from the National Cardiovascular Data Registry (NCDR). Am. Heart J. 2015, 170, 330–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, M.O.; Contractor, T.; Zachariah, D.; van Spall, H.G.; Parwani, P.; Minissian, M.B.; et al. Sex Disparities in the Choice of Cardiac Resynchronization Therapy Device: An Analysis of Trends, Predictors, and Outcomes. Can. J. Cardiol. 2021, 37, 86–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, A.W.; O’Regan, D.P.; Gould, J.; Sidhu, B.; Sieniewicz, B.; Plank, G.; et al. Sex-Dependent QRS Guidelines for Cardiac Resynchronization Therapy Using Computer Model Predictions. Biophys. J. 2019, 117, 2375–2381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Bijl, P.; Delgado, V. Understanding sex differences in response to cardiac resynchronization therapy. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging 2019, 20, 498–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savji, N.; Meijers, W.C.; Bartz, T.M.; Bhambhani, V.; Cushman, M.; Nayor, M.; et al. The Association of Obesity and Cardiometabolic Traits With Incident HFpEF and HFrEF. JACC Heart Fail. 2018, 6, 701–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haykowsky, M.J.; Nicklas, B.J.; Brubaker, P.H.; Hundley, W.G.; et al. Regional adipose distribution and its relationship with exercise intolerance in older obese patients who have heart failure with preserved efction fracture. JACC Heart Fail. 2018, 6, 640–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sorimachi, H.; Omote, K.; Omar, M.; Popovic, D.; Verbrugge, F.H.; Reddy, Y.N.; et al. Sex and central obesity in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2022, 24, 1359–1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambikairajah, A.; Walsh, E.; Tabatabaei-Jafari, H.; Cherbuin, N. Fat mass changes during menopause: A metaanalysis. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2019, 221, 393–409.e50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, C.L.; Chao, T.F.; Su, C.H.; Liao, J.N.; Sung, K.T.; Yeh, H.I.; et al. Income level and outcomes in patients with heart failure with universal health coverage. Heart 2021, 107, 208–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Velásquez, I.M.; et al. Sex Differences in the Relationship of Socioeconomic Position With Cardiovascular Disease, Cardiovascular Risk Factors, and Estimated Cardiovascular Disease Risk: Results of the German National Cohort. J Am Heart Assoc. 2025, 14, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pencina, M.J.; Navar, A.M.; Wojdyla, D.; Sanchez, R.J.; Khan, I.; Elassal, J.; D’Agostino, R.B., Sr.; Peterson, E.D.; Sniderman, A.D. Quantifying importance of major risk factors for coronary heart disease. Circulation 2019, 139, 1603–1611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, W.; Wu, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Liang, W.; Xue, R.; Wu, Z.; et al. Living Alone and Clinical Outcomes in Patients With Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction. Psychosom. Med. 2021, 83, 470–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiGiacomo, M.; Davidson, P.M.; Zecchin, R.; Lamb, K.; Daly, J. Caring for Others, but Not Themselves: Implications for Health Care Interventions in Women with Cardiovascular Disease. Nursing Research and Practice 2011, 2011, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tapia, J.; et al. Psychosocial factors partially explain gender differences in health-related quality of life in heart failure patients. ESC Heart Failure 2023, 10, 1090–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shih, M.L.; Tsai, S.T.; Chen, H.M.; Chou, F.H.; Liu, Y. Gender differences? Factors related to quality of life among patients with heart failure. Women Health 2020, 60, 382–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sandhu, R.K.; Smigorowsky, M.; Lockwood, E.; Savu, A.; Kaul, P.; McAlister, F.A. Impact of electrical cardioversion on quality of life for the treatment of atrial fibrillation. Can J Cardiol. 2017, 33, 450–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strømnes, L.A.; Ree, H.; Gjesdal, K.; Ariansen, I. Sex Differences in Quality of Life in Patients With Atrial Fibrillation: A Systematic Review. Journal of the American Heart Association 2019, 8, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, I.Y.; et al. Temporal trends of women enrollment in major cardiovascular randomized clinical trials. Can. J. Cardiol. 2019, 35, 653–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawson, C.A.; Zaccardi, F.; Squire, I.; Ling, S.; Davies, M.J.; Lam, C.S.; et al. 20-year trends in cause-specific heart failure outcomes by sex, socioeconomic status, and place of diagnosis: A population-based study. Lancet Public Health 2019, 4, e406–e20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redfield, M.M.; Jacobsen, S.J.; Borlaug, B.A.; Rodeheffer, R.J.; Kass, D.A. Age- and gender-related ventricular-vascular stiffening: A community-based study. Circulation 2005, 112, 2254–2262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pieske, B.; Patel, M.J.; Westerhout, C.M.; Anstrom, K.J.; Butler, J.; Ezekowitz, J.; Hernandez, A.F.; Koglin, J.; Lam, C.S.; Ponikowski, P.; et al. Baseline features of the VICTORIA (Vericiguat Global Study in Subjects with Heart Failure with Reduced Ejection Fraction) trial. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2019, 21, 1596–1604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamargo, J.; Caballero, R.; Delpón, E. Sex-related differences in the pharmacological treatment of heart failure. Pharmacol. Ther. 2022, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dewan, P.; Rørth, R.; Raparelli, V.; et al. Sex-related differences in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Circ Heart Fail. 2019, 12, e006539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beale, A.L.; Nanayakkara, S.; Segan, L.; Mariani, J.A.; Maeder, M.T.; van Empel, V.; Vizi, D.; Evans, S.; Lam, C.S.P.; Kaye, D.M. Sex differences in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction pathophysiology: a detailed invasive hemodynamic and echocardiographic analysis. JACC Heart Fail. 2019, 7, 239–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).