1. Introduction

Despite the availability of an organized cervical cancer screening program, approximately 4,300 women are newly diagnosed with cervical cancer each year in Germany [

1]. The age-standardized annual incidence rate is about 8.6 per 100,000 individuals. In 2019, 1,597 women died from cervical cancer, corresponding to an age-standardized mortality rate of 2.5 per 100,000 individuals [

1].

Cervical cancer is largely preventable through regular screening. Since the 1970s, the implementation of screening programs in high-income countries has led to a substantial decline in both incidence and mortality [

2]. In Germany, an opportunistic screening program has been in place since 1971, with a steady annual participation rate of about 50% [

3]. As of 2020, the program was reorganized as part of the national cancer screening initiative. In the new organized cervical cancer screening program, women aged 20–34 are eligible for annual cytology (Pap smear), while women aged 35 and older receive human papillomavirus (HPV)-Pap co-testing every three years [

4]. This is complemented by HPV vaccination, which has been recommended for girls since 2007 and for both boys and girls starting at age 9 since 2018 [

3,

5].

Nevertheless, a significant portion of the target population eligible for screening does not participate regularly [

6]. HPV self-sampling (HPV-SS) has emerged as a promising strategy to increase screening participation. Studies suggest that mailing self-sampling kits can boost participation by up to 15% and provide diagnostic accuracy comparable to clinician-collected samples [

7,

8].

Therefore, we systematically evaluated the long-term effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of various HPV-SS strategies targeting non-attenders within Germany’s organized cervical cancer screening program.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Type and Framework

We used a previously published Markov state-transition model validated for the German context [

3,

9,

10] to perform a decision-analytic incremental benefit-harm and cost-effectiveness analysis [

11] of offering HPV-SS to women not attending the organized cervical cancer screening program in Germany. The analyses were based on deterministic cohort simulations performed from the perspective of the German statutory health insurance system in the health-economic evaluation and from the perspective of the individual woman in the benefit-harm analysis. Evaluated outcomes included prevented cervical cancer cases, prevented deaths, life-years gained [LYG], total number of positive screening findings, colposcopies and conizations, total lifetime costs (in Euros), the incremental harm-benefit ratios (IHBR) and the incremental cost-effectiveness ratios (ICER; in Euros/LYG), compared to the next non-dominated strategy. In the cost-effectiveness analyses, all costs and effects were discounted by three percent per year [

12].

2.2. Screening Strategies

The evidence-based decision model was used to compare different screening strategies offering HPV-SS for non-attendees in the established organized cervical cancer screening program. These strategies (

Table 1) differ in terms of their mode (opt-in or send-to-all) and the age at which screening using self-sampling begins (from 35, 30 or 25 years up to the age of 65 in each case). In the opt-in strategies, women are given the opportunity to order an HPV-SS test kit at home at the time they receive the information and invitation letter for organized screening sent out regularly every 5 years. In contrast, in the send-to-all strategies, the HPV-SS test kit is directly sent together with the information and invitation letter for organized screening.

The reference strategy is the current organized screening program in Germany with an annual Pap test for women aged 20 to 34 and triennial HPV- Pap co-testing for women aged 35 and older with no upper age limit for screening to end. In the reference strategy no additional HPV-SS strategy for non-attendees is offered.

2.3. Model Design, Structure, and Data

A previously published Markov state-transition model [

3,

9,

10] simulating cervical cancer onset and progression, detection, and management for women not vaccinated against HPV16/18 in the Germany context was updated. The model structure and parameters were updated and adapted to the context of the current new standard of organized screening with annual cytology age 20 to 34 and triennial HPV-Pap co-testing from age 35 onwards, the current clinical practice algorithms for follow-up of positive test results, and the implementation of different self-sampling strategies for women not attending the organized screening program [

2] (see Supplementary Material

Figure S1). The design of the model follows the international ISPOR-SMDM Modeling Good Research Practices Task Force standards of decision-analytic modelling, and international key principles for health technology assessment (HTA) [

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20] as well as national and international health-economic evaluation and reporting guidelines [

12,

21]. Reporting of the model and reporting of analyses results were conducted in accordance with the Consolidated Health Economic Evaluation Reporting Standards 2022 (CHEERS 2022) statement [

22]. The model was developed to be applied in the context of HTA and comparative effectiveness research. The model structure, parameters, calibration, and validation process are described in detail elsewhere [

3,

9,

10].

In brief, a hypothetical cohort of women not vaccinated against oncogenic HPV types from the general population moves through different health states (Markov states) over time in annual cycles. Health states include a “No lesion/no HPV infection” state, a “No Lesion/HPV infection” state and different stages of undetected and screen-detected preinvasive cervical lesions (cervical intra-neoplasia [CIN]), different stages of undetected or screen- and symptom-detected invasive cancer stages I-IV following the classification of the Fédération Internationale de Gynécologie et d’Obstétrique (FIGO) system, as well as death from cancer or from other causes. A graphical illustration of the model including health states as well as important model input parameters have been published previously [

23]. Annual transition probabilities of disease onset and progression were calibrated to German epidemiological data of an unscreened population [

9].

Information on the clinical algorithms after a positive test result and further follow-up procedures was derived from current German guidelines on the diagnosis and treatment of preinvasive and invasive cervical carcinomas and the recommendation for the organized cancer screening programs in Germany [

2,

3,

4] (Supplementary Material

Figure S1).

German age- and gender-specific all-cause mortality rates were derived from German life tables for the female population [

24]. In the model, age-specific mortality due to causes other than cervical cancer was used by subtracting age-specific cervical cancer mortality from all-cause mortality. Stage-specific cervical cancer relative survival rates were retrieved from German cancer registries and used to model disease-specific mortality [

1,

5].

Screening test accuracy data were derived from published international meta-analyses (

Table 2) [

7,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29]. Relative test accuracy data for HPV testing in a self-swab sample compared to a swab taken by medical staff were based on a published meta-analysis (

Table 3) [

7].

For colposcopy, 96% sensitivity and 48% specificity were assumed based on published literature [

30]. A biopsy is only performed in the model if the colposcopy is positive. For simplicity, it was assumed that a colposcopy-assisted biopsy always correctly identifies the underlying disease. Compliance with follow-up measures in cases of abnormal screening results, diagnoses, and treatments was modelled to be complete in the base-case analysis.

For the participation rate, in the established organized screening program, national, age-specific, aggregated data on the uptake of screening for cervical cancer were used (

Table 4) [

6]. Data on participation in HPV-SS were retrieved from a randomized controlled trial (RCT) in Norway [

31]. In this trial, the participation in HPV-SS among non-attendees of the Norwegian national screening program was 12.2% (95% CI: 10.3; 14.2) using the opt-in mode and 22.9% (95% CI: 20.7; 25.2) using the send-to-all mode [

31].

Direct medical outpatient and inpatient costs were derived from the perspective of the German statutory health insurance system (

Table 5). Outpatient costs associated with screening including physician-based examination, cervical swab, management of abnormal screening results, diagnostic procedures such as colposcopy with biopsy, laboratory procedures, conization, and follow-up after treatment were based on the German reimbursement system for ambulatory fees using the Standardised Valuation Scale (Einheitlicher Bewertungsmaßstab [EBM]) and specified point values for the index year 2023 [

32].

The costs for the HPV-SS test kit include the costs for an Evalyn Brush test kit, a sample container for collection and the postage costs for dispatch, return and results dispatch and were taken from the Hanover Self-Sampling Study (HaSCo) [

33].

Costs for inpatient treatment and care including treatment of detected invasive carcinoma by stage, pre-treatment tumour staging and other diagnostic procedures, laboratory and post-treatment follow-up were calculated based on the diagnosis-related groups (DRG). These cost data were obtained from published literature based on German data [

34]. All costs were collected for or converted to the year 2023 using the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) Index [

35].

Table 5 shows the aggregated costs (per unit) for screening, diagnostics, treatment and follow-up procedures.

2.4. Model Analyses

Our analyses were based on deterministic cohort simulations. For each of the alternative screening strategies, we calculated the total remaining life expectancy in life years (LY), total lifetime costs (in Euros) and the discounted ICER in Euros per life-years gained (Euros/LYG) over a woman’s lifetime. The ICER is calculated as the ratio of the discounted incremental total costs to the discounted incremental total health effects between two alternatives. Strategies yielding lower health benefits at higher costs are dominated and were excluded before ICER calculation. Furthermore, extended dominance is applied to exclude strategies whose costs and benefits are dominated by a linear combination of two other alternatives. A dominant strategy, in contrast, yields greater health benefits at lower cost than all comparators [

36,

37]. The incremental stepwise cost-effectiveness approach is illustrated using efficiency frontiers, plotting discounted total costs against discounted life-years gained versus no screening. Strategies on the efficiency frontier yield higher benefits per unit cost than those below the frontier.

In Germany, no external, cross-indication willingness-to-pay (WTP) threshold has been established as a criterion for cost-effectiveness [

12]. Gandjour et al. estimated a WTP- threshold of about 90,000 Euros per life-year gained for innovative, life-prolonging health technologies in Germany [

38]. In our analysis, we adopt this threshold as the upper limit for determining cost-effectiveness [

38].

We conducted one-way and multi-way sensitivity analyses to assess the robustness of our results and to identify influential parameters. Specifically, we varied the participation rate in HPV-SS based screening, test accuracy (relative sensitivity and specificity of HPV-SS) including different test approaches such as signal amplification (SA) or poly- chain reaction (PCR), compliance following a positive HPV-SS result based on the 95% confidence intervals. As HPV-SS is currently not reimbursed by health insurance in Germany, we varied the HPV-SS costs over a wide range (10 to 100 Euros) using a multiplicative factor.

In multi-way sensitivity analyses, participation rates for both HPV-SS modes (opt-in and opt-out) were simultaneously varied in the same direction.

The decision-analytic model was programmed, calibrated, and analysed using TreeAge Pro Healthcare software (version 2021, R2.0; TreeAge Software, LLC) [

39]. Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Corporation, Microsoft 365 MSO, 2021) was used for parameter calculation and data transformation.

3. Results

3.1. Base-Case Analyses

3.1.1. Cancer Risk Reduction

Compared to established current standard screening, additionally offering HPV-SS to non-attendees every five years yields a relative risk reduction for developing cervical cancer of 4.1% (HPV-SS, opt-in, age 25-65) to 7.6% (HPV-SS, send-to-all, age 25-65), respectively. The corresponding relative risk reduction for cancer deaths is 4.9% (HPV-SS, opt-in, age 25-65) to 9.1% (HPV-SS, send-to-all, age 25-65), respectively (results not shown).

3.1.2. Benefit-Harm Balance

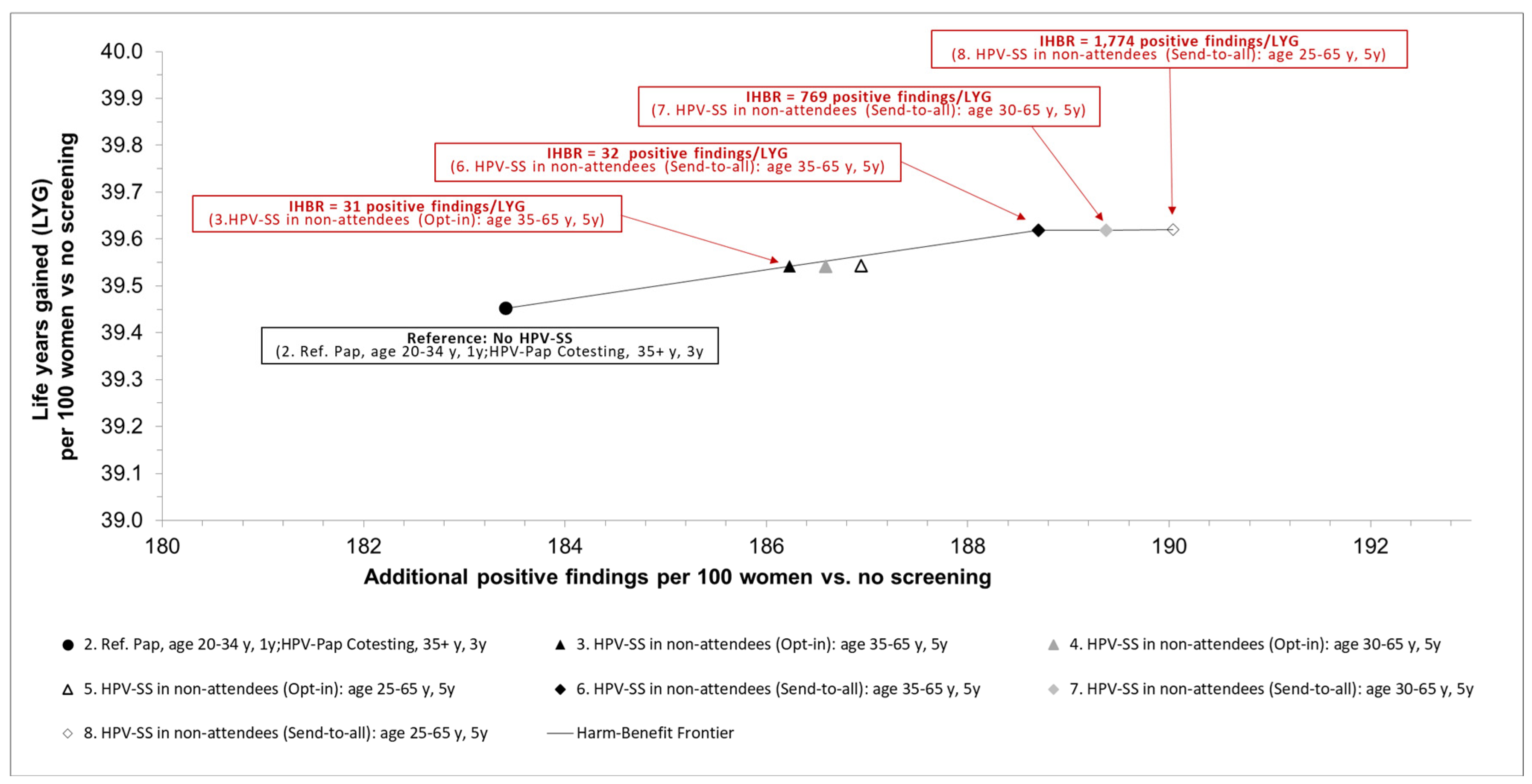

In the benefit-harm analysis, the total incremental undiscounted benefits (in terms of life-years gained) were traded-off against the total incremental undiscounted harms (in terms of potential psychological and/or physical harms associated with positive screening findings or colposcopies) of the investigated screening strategies.

Figure 1 shows the trade-offs between benefits in terms of life-years gained and potential psychological and physical harms associated with positive findings.

Compared to established current standard screening, additionally offering HPV-SS (opt-in) to non-attendees every five years from age 35 to age 65, results in an incremental harm-benefit ratio of 31 additional positive screening tests per LYG. Offering to non-attendees HPV-SS in a send-to-all setting every five years between age 35 and 65 yields a higher benefit in terms of life-years gained and results in an IHBR of additional 32 positive screening results per additional LYG. If HPV-SS is offered earlier at age 30 or 25 years in the send-to-all setting, the incremental gains in life-years are small, resulting in increased IHBRs of 770 or 1,770 additional positive screening results per additional LYG (

Figure 1).

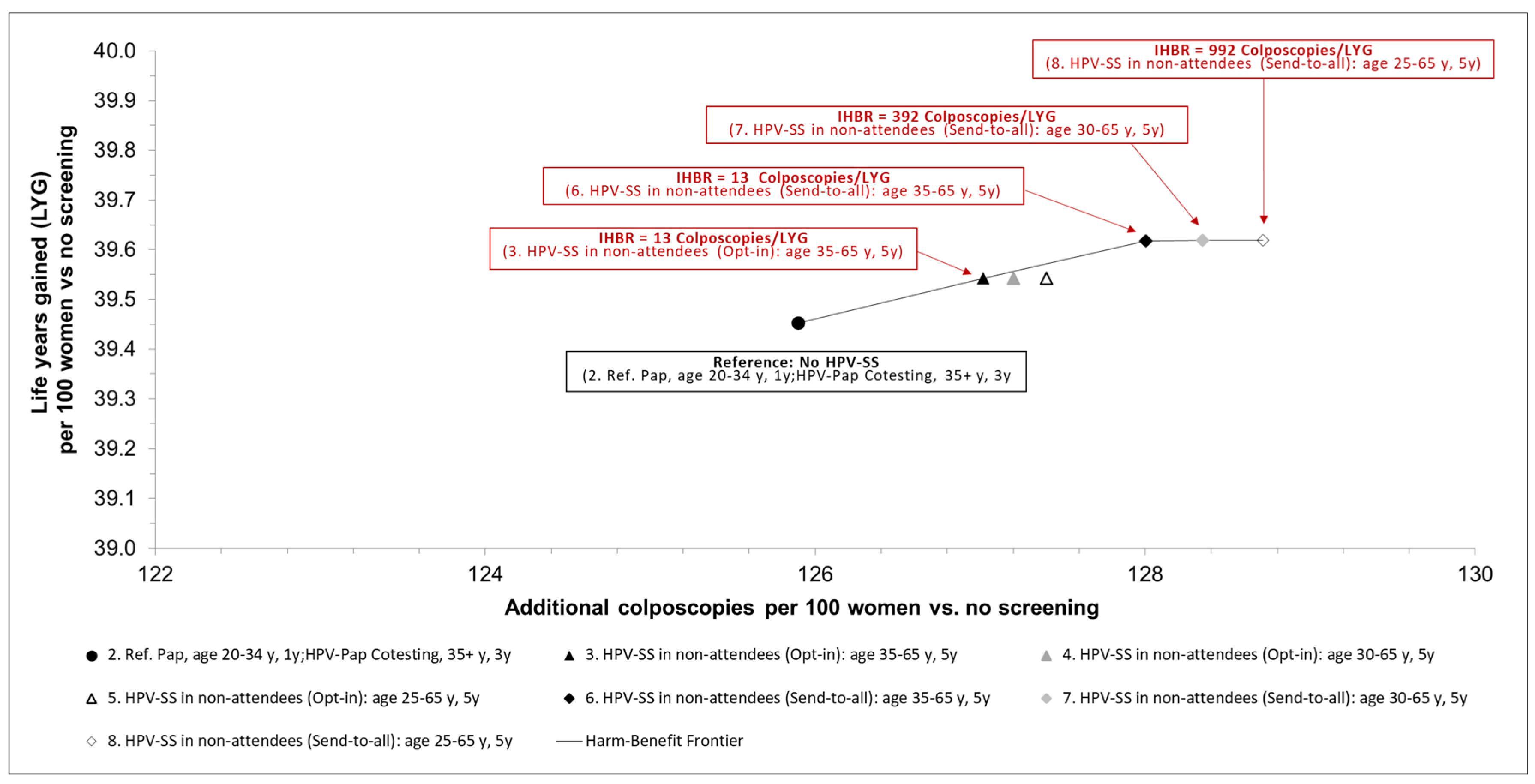

Figure 2 shows the trade-offs between benefits in terms of life-years gained and potential psychological and physical harms associated with colposcopy-guided biopsies.

Compared to established current standard screening, additionally offering HPV-SS (opt-in) to non-attendees every five years between age 35 and 65, results in an IHBR of 13 additional colposcopies per LYG. Offering HPV-SS in a send-to-all setting to non-attendees every five years between age 35 and 65 yields a higher benefit in terms of life-years gained and results in an IHBR of 13 additional colposcopies results per additional LYG. If HPV-SS is offered earlier at age 30 or 25 years in the send-to-all setting, the incremental gains in life-years are small, resulting in increased IHBRs of 392 or 992 additional colposcopies per additional LYG (

Figure 2).

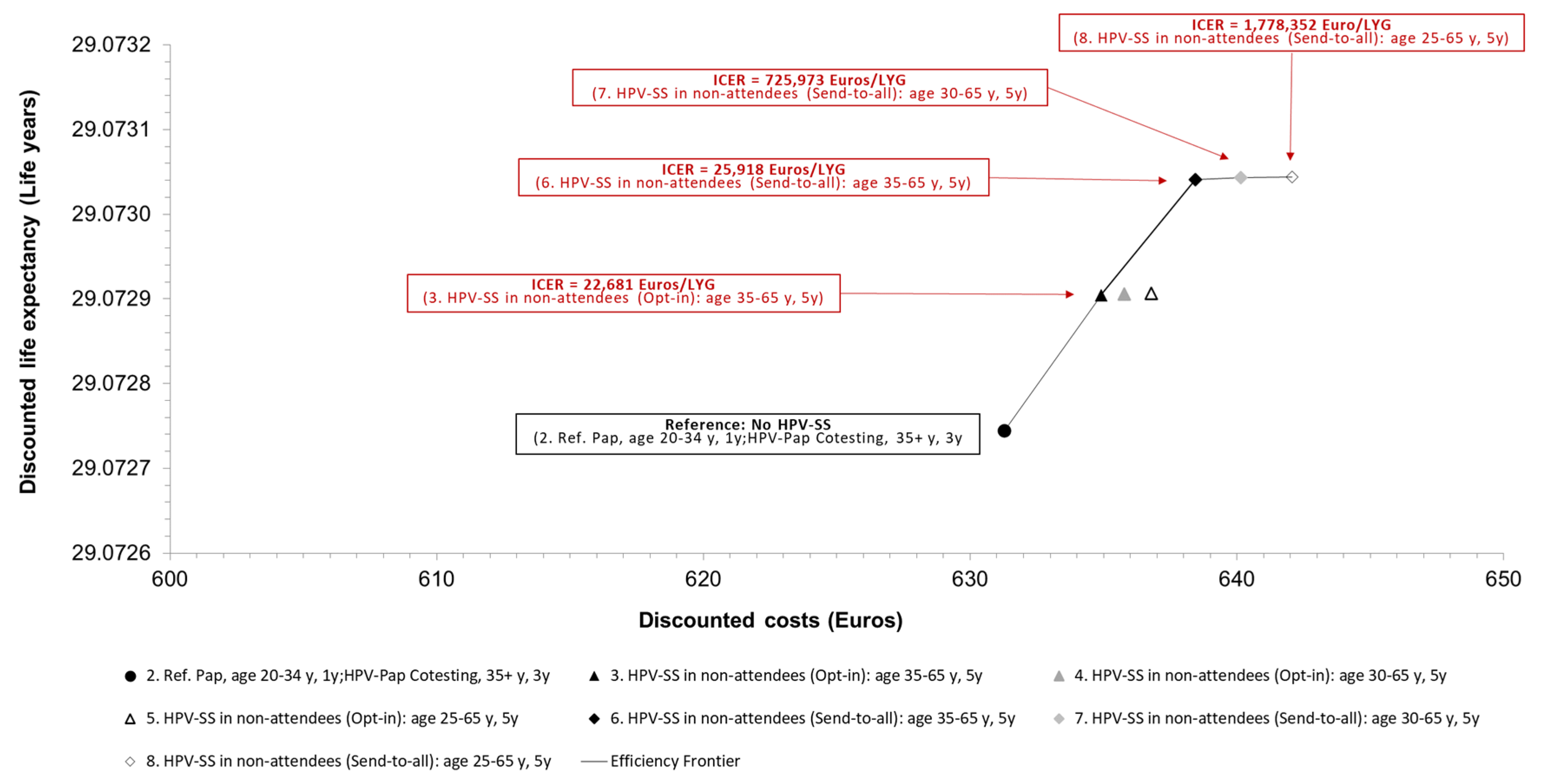

3.1.3. Cost-Effectiveness

In the cost-effectiveness analysis, the total incremental discounted costs were related to the total incremental discounted benefits of the investigated screening strategies (

Table 6). Compared to current standard screening for cervical cancer, additionally offering HPV-SS (opt-in) to non-attendees every five years from the age of 35 to age 65 yields an ICER of 23,000 Euro/LYG. If HPV-SS every five years between age 35 and 65 is offered to non-attendees in a send-to-all compared to an opt-in setting, the ICER was 26,000 Euros/LYG. If HPV-SS in the send-to-all setting is offered earlier at age 30 or 25 years, the ICERs increase to 726,000 Euros/LYG (compared to HPV-SS age 35-65) and 1,780,000 Euros/LYG (compared to HPV-SS age 30-65) and cannot be considered cost-effective adopting a WTP-threshold of 90,000 Euros/LYG (

Figure 3).

3.2. Sensitivity Analyses

To assess the robustness of the base case results, deterministic one-way and multi-way sensitivity analyses were conducted. Key model parameters were varied to identify influential factors, including HPV test accuracy (PCR vs. SA), participation rate in HPV-SS, HPV-SS test performance and cost, and compliance following a positive HPV test. The following subsections present the main findings from these analyses with a focus on their effects on the ICERs.

The results were robust over a wide variation of relevant parameter values for HPV test accuracy, relative test performance of HPV-SS, using the HPV tests with signal amplification, and HPV-SS participation rate (results not shown).

Sensitivity analyses examining the effect of varying the cost of the HPV-SS kit - including shipping and return - show that if the cost exceeds 90 Euros, the ICER for the send-to-all strategy (for non-participants aged 35 and older, every 5 years) exceeds 90,000 Euros per life year gained. This means the strategy would no longer be considered cost-effective under a WTP-threshold of 90,000 Euros per life year gained. In contrast, the opt-in strategy remains cost-effective across the evaluated range for the costs of the HPV-SS kit (10-100 Euros) (results not shown).

Sensitivity analysis on the effect of compliance after a positive HPV test within the HPV-SS strategies reveals that if compliance falls below 20%, the ICERs of all HPV-SS strategies exceed 90,000 Euros per life year gained when compared to the next most effective non-dominated screening strategy. Under a WTP-threshold of 90,000 Euros per LYG, none of the HPV-SS strategies would be considered cost-effective in this scenario.

Table 7 provides the results for compliance levels ranging from 10% to 100%.

4. Discussion

The aim of this study was to use an evidence-based decision-analytic modelling approach for the German context to assess the long-term benefits, potential risks, the benefit-harm balance and the cost-effectiveness of HPV-SS testing in women in Germany who do not participate in conventional screening in addition to the established organized cervical cancer screening program. For this purpose, a decision-analytic Markov model based on the best available evidence from various sources was developed to represent the consequences of different cervical cancer screening strategies investigated with respect to various benefit and harm endpoints. Extensive sensitivity analyses were performed to assess the uncertainty of the results.

Based on the results from the base-case-analyses, an additional screening strategy with HPV-SS every five years for women who do not participate in the established screening program reduces the lifetime risk of developing cervical cancer and dying from detected cervical cancer across all examined strategies, with varying starting ages and modalities (opt-in or send-to-all). The earlier HPV-SS is offered (at ages 25 vs. 30 vs. 35), the greater the benefit in terms of preventing cervical cancer-related deaths. Associated with the participation rate, the effect is higher in the send-to-all mode, where self-tests are sent directly to women’s homes, compared to the opt-in model, where women need to order the test kit.

Screening can also have harmful aspects, such as potential psychological harm from positive (including false-positive) screening results and overdiagnosis, which can lead to overtreatment and significantly impair quality of life during treatment. This potential harm increases with the intensity of the screening, reflected in the rising expected values of harm endpoints, such as the number of positive screening results, colposcopies, or cone biopsies. For this reason, various benefit-harm endpoints were compared explicitly, with IHBRs calculated and presented. The benefit, measured as life years gained, was compared to the harm, measured by the number of positive screening results, colposcopies, or cone biopsies.

The results of all analyses show that an additional offer of HPV-SS screening every five years for women not participating in the established screening program can be more effective and cost-effective than the established organized screening (based on a clinician-performed smear) without HPV-SS in the German context. The send-to-all strategy for non-participants, starting at age 35, was optimal in terms of the benefit-harm ratio and cost-effectiveness. Initiating the send-to-all strategy earlier at age 30 or 25 resulted in only a marginal increase in life expectancy, but the IHBRs and incremental ICERs were significantly higher.

Our findings are consistent with international model-based studies examining similar strategies [

40,

41,

42]. However, direct comparisons are challenging, as some studies only compared strategies with no screening in non-participants and did not conduct incremental analyses of different strategies, particularly those with varying starting ages [

43,

44]. Additionally, in most international studies, the established reference strategy was HPV testing alone every five years with an upper age limit of 60 or 65 years. In Germany, the current reference strategy is co-testing with Pap and HPV every three years starting at age 35, with no upper age limit.

A key strength of this decision-analytic study is that it quantifies and transparently presents the long-term trade-offs between health benefits and potential harms associated with various screening strategies. These strategies differ not only in the starting age but also in the mode (opt-in or send-to-all along with the established five-year invitation procedure) for implementation of HPV-SS within the established screening program in Germany. Furthermore, the approach of explicit trade-offs with the quantification of IHBRs showed largely consistent results with results of the cost-effectiveness analysis, enabling the identification of optimal screening strategies based on both ratios. Thus, this decision-analytic modelling study provides a transparent and robust foundation for healthcare decision-makers and complements the results of clinical studies, such as the HaSCo study, which often cannot track the long-term effects of screening and may involve heterogeneous study designs and conditions that differ from real-world screening settings.

As any decision-analytic model, this model is based on current evidence regarding various epidemiological and clinical parameters, as well as assumptions that may influence the results which should therefore be considered as limitations. First, due to the lack of detailed individual data, it was assumed that the age-specific participation rate in the established screening program during each screening round would correspond to the average age-specific participation rates, regardless of a woman’s previous screening history. Individual-level data on more complex participation rates were unavailable. Second, no empirical data on quality of life could be incorporated into the model. Therefore, the long-term effectiveness was calculated based on life expectancy (measured in years) rather than quality-adjusted life expectancy (measured in quality-adjusted life years, QALYs). Since screening results in a relatively small average gain in life expectancy, changes in quality of life due to psychological distress associated with the communication of screening results or adverse events during cancer prevention treatments could significantly influence the estimated IHBRs and/or ICERs. Third, the data on the sensitivity and specificity of the primary screening tests, as well as the relative test performance of HPV-SS compared to HPV tests from physician-collected samples, are based on results from international meta-analyses with data from randomized clinical trials. However, these test performance values may be significantly lower in practice. Fourth, although selected alternative screening strategies for non-participants with different starting ages in both the opt-in and send-to-all modes were analysed, not all possible alternatives were fully explored. Alternative screening strategies could alter the IHBR and ICER and should be considered in future studies [

45]. For instance, no strategies were examined that ended at ages other than 65 years or employed a shorter screening interval (e.g., every three years). Furthermore, no screening strategy was tested where all women, including those already participating in the established screening program, were offered the option for HPV-SS. Future modelling studies should explore these alternative screening strategies.

Another limitation of our study is that the results only apply to unvaccinated women. In the future, the cervical cancer screening program will likely be adjusted as vaccinated cohorts reach the screening age. A separate analysis for this future scenario is necessary, but it falls outside the scope of the current project. However, it can be assumed that offering HPV-SS for non-participants who are vaccinated against HPV will be less effective and therefore associated with higher ICERs, as fewer health benefits can be achieved in this population due to the lower background risk.

The relative sensitivity and specificity of HPV testing in self-sampling compared to physician-collected samples depend on the choice of testing methods, here PCR and SA. However, even with the use of a validated PCR test, it is possible that the sensitivity and specificity of HPV-SS may be lower than that of physician-collected samples in practice. Sensitivity analysis results regarding the impact of variations in the relative sensitivity and specificity of HPV-SS compared to HPV tests from physician-collected samples on the ICER show that an HPV-SS offer can still be cost-effective, even with lower relative sensitivity and specificity.

Finally, there is currently no empirical evidence on the distribution of acceptability thresholds of screening-eligible women in Germany for the acceptable harm per additional unit of benefit, that is, how many cases of overtreatment women consider acceptable to prevent one additional death from cervical cancer. This acceptability threshold can vary considerably among individuals depending on women’s age, their individual preferences, and their individual perceptions of the severity of treatment consequences and their impact on individual quality of life. Future research should elicit the distribution of harm-benefit acceptability thresholds for women in Germany eligible for cervical cancer screening.

5. Conclusions

Based on our simulation results offering non-attendees of the German national cervical cancer screening program the possibility to perform a self-sample for HPV testing by sending the test kit every five years starting as of age 35 may provide an acceptable benefit-harm balance and be cost-effective for the German context. Results may inform decision makers and clinical guideline developers regarding the specific strategy of HPV-SS implementation in Germany.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org. Figure S1: Screening and follow-up algorithms of (a) HPV-Pap contesting as of age 35, and (b) HPV self-sampling.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.S., and U.S.; methodology, G.S., and U.S; software, G.S., M.M.; validation, G.S.., L.H., M.M.; formal analysis, G.S., L.H., M.M.; investigation, G.S., L.H., M.M., and U.S.; resources, G.S., and U.S.; data curation, G.S.., L.H., M.M., L.S., P.H. and M.J.; writing—original draft preparation, G.S..; writing—review and editing, G.S.., L.H., M.M., L. S., P.H., M. J., U.S.; visualization, G.S.., L.H., M.M.; supervision, G.S., and U.S.; project administration, G.S.., P. H., M. J., and U.S.; funding acquisition, G.S., P.H., M. J. and U.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.”.

Funding

This work was performed within the Hannover Self Collection (HaSCo) study, which was funded by a grant of the German Cancer Aid (Deutsche Krebshilfe), grant agreement no. DKH-70113664. The funding agreement ensured the authors’ independence in designing the study, analysing, and interpreting the data, writing, and publishing the report. The article processing charge (APC) was funded by XXX.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The institutional review board of the Medical Faculty of the Hannover Medical School, Hannover, Germany has given ethics approval for the Hannover Self Collection (HaSCo) study (No. 8692_BO_S_2019). In addition, this decision-analytic study was approved and registered at the Research Committee for Scientific Ethical Questions at UMIT TIROL - University for Health Sciences and Technology, Hall i. T., Austria (Registration 2808).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

This study used a decision-analytic simulation model, which was parametrized by aggregated model input data from different sources. The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/supplementary material. All model input data and corresponding sources are explicitly described in the manuscript and/or are available in the public domain. No original individual-based data or datasets were used or generated. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We thank Lennart Koch for editing, formatting and quality check and Ellen John for English native speaker check and proof reading. During the preparation of this manuscript, the author(s) used [Microsoft Copilot, powered by GPT-5, developed by OpenAI and integrated by Microsoft.] for the purposes of generating a graphical abstract. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

All authors have completed a unified conflict of Interest declaration form and declare that no company has supported the submitted work. The authors declare no conflicts of interest.:.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CI |

Confidence interval |

| CIN |

cervical intra-neoplasia |

| FIGO |

Fédération Internationale de Gynécologie et d’Obstétrique |

| DRG |

Diagnosis related groups |

| GDP |

Gross domestic product |

| HPV |

Human papillomavirus |

| HPV-SS |

HPV self-sampling |

| HTA |

Health technology assessment |

| ICER |

Incremental cost-effectiveness ratio |

| IHBR |

Incremental harm-benefit ratio |

| LY |

Life years |

| LYG |

Life-years gained |

| PCR |

Polymerase chain reaction. |

| RCT |

Randomized controlled trial |

| SA |

Signal amplification |

| WHO |

World health organization |

| WTP |

Willingness-to-pay |

References

- Robert Koch-Institut (RKI). Gebärmutterhalskrebs (Zervixkarzinom) ICD-10 C53. 2019.

- Gemeinsamer Bundesausschuss (G-BA). Richtlinie des Gemeinsamen Bundesausschusses für organisierte Krebsfrüherkennungsprogramme oKFE-Richtlinie/oKFE-RL. 2023.

- Deutsche Krebsgesellschaft, D.K., AWMF. S3-Leitlinie Prävention des Zervixkarzinoms, Langversion. 2017.

- Gemeinsamer Bundesausschuss (G-BA). Beschluss des Gemeinsamen Bundesausschusses über eine Änderung der Krebsfrüherkennungs-Richtlinie und eine Änderung der Richtlinie für organisierte Krebsfrüherkennungsprogramme: Programm zur Früherkennung von Zervixkarzinomen. Vom 22. November 2018. 2018.

- Robert Koch-Institut (RKI). Krebs in Deutschland für 2017/2018. 2021.

- Kerek-Bodden, H.; Altenhofen, L.; Brenner, G.; Franke, A. Durchführung einer versichertenbezogenen Untersuchung zur Inanspruchnahme der Früherkennung auf Zervixkarzinom in den Jahren 2002, 2003 und 2004 auf der Basis von Abrechnungsdaten; Zentralinstitut für die kassenärztliche Versorgung in der Bundesrepublik Deutschland: Berlin, 2008.

- Arbyn, M.; Smith, S.B.; Temin, S.; Sultana, F.; Castle, P. Detecting cervical precancer and reaching underscreened women by using HPV testing on self samples: updated meta-analyses. Bmj 2018, 363, k4823. [CrossRef]

- Verdoodt, F.; Jentschke, M.; Hillemanns, P.; Racey, C.S.; Snijders, P.J.F.; Arbyn, M. Reaching women who do not participate in the regular cervical cancer screening programme by offering self-sampling kits: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised trials. European Journal of Cancer 2015, 51, 2375-2385. [CrossRef]

- Sroczynski, G.; Schnell-Inderst, P.; Muhlberger, N.; Lang, K.; Aidelsburger, P.; Wasem, J.; Mittendorf, T.; Engel, J.; Hillemanns, P.; Petry, K.U.; et al. Cost-effectiveness of primary HPV screening for cervical cancer in Germany - a decision analysis. Eur J Cancer 2011, 47, 1633-1646. [CrossRef]

- Sroczynski, G.; Schnell-Inderst, P.; Muhlberger, N.; Lang, K.; Aidelsburger, P.; Wasem, J.; Mittendorf, T.; Engel, J.; Hillemanns, P.; Petry, K.U.; et al. Decision-analytic modeling to evaluate the long-term effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of HPV-DNA testing in primary cervical cancer screening in Germany. GMS Health Technol Assess 2010, 6, Doc05. [CrossRef]

- Siebert, U. When should decision-analytic modeling be used in the economic evaluation of health care? The European Journal of Health Economics, formerly: HEPAC 2003, 4, 143-150. [CrossRef]

- Institut für Qualität und Wirtschaftlichkeit im Gesundheitswesen (IQWiG). Allgemeine Methoden. Version 7.0 (vom 19.09.2023). 2023.

- Caro, J.J.; Briggs, A.H.; Siebert, U.; Kuntz, K.M. Modeling good research practices--overview: a report of the ISPOR-SMDM Modeling Good Research Practices Task Force--1. Value Health 2012, 15, 796-803. [CrossRef]

- Drummond, M.; Weatherly, H.; Ferguson, B. Economic evaluation of health interventions. Bmj 2008, 337, a1204. [CrossRef]

- Siebert, U.; Alagoz, O.; Bayoumi, A.M.; Jahn, B.; Owens, D.K.; Cohen, D.J.; Kuntz, K.M. State-Transition Modeling: A Report of the ISPOR-SMDM Modeling Good Research Practices Task Force-3. Value in Health 2012, 15, 812-820.

- (EUnetHTA), E.N.f.H.T.A. Guideline. Methods for health economic evaluations – A guideline based on current practices in Europe. 2015. https://www.eunethta.eu/wp-content/uploads/2018/2003/Methods_for_health_economic_evaluations.pdf.

- Caro, J.J.; Briggs, A.H.; Siebert, U.; Kuntz, K.M. Modeling good research practices--overview: a report of the ISPOR-SMDM Modeling Good Research Practices Task Force-1. Med Decis Making 2012, 32, 667-677. [CrossRef]

- Roberts, M.; Russell, L.B.; Paltiel, A.D.; Chambers, M.; McEwan, P.; Krahn, M. Conceptualizing a model: a report of the ISPOR-SMDM Modeling Good Research Practices Task Force-2. Med Decis Making 2012, 32, 678-689. [CrossRef]

- Siebert, U.; Alagoz, O.; Bayoumi, A.M.; Jahn, B.; Owens, D.K.; Cohen, D.J.; Kuntz, K.M. State-transition modeling: a report of the ISPOR-SMDM Modeling Good Research Practices Task Force-3. Med Decis Making 2012, 32, 690-700. [CrossRef]

- Drummond, M.F.; Schwartz, J.S.; Jönsson, B.; Luce, B.R.; Neumann, P.J.; Siebert, U.; Sullivan, S.D. Key principles for the improved conduct of health technology assessments for resource allocation decisions. Int J Technol Assess Health Care 2008, 24, 244-258; discussion 362-248. [CrossRef]

- Husereau, D.; Drummond, M.; Augustovski, F.; de Bekker-Grob, E.; Briggs, A.H.; Carswell, C.; Caulley, L.; Chaiyakunapruk, N.; Greenberg, D.; Loder, E.; et al. Correction to: Consolidated Health Economic Evaluation Reporting Standards 2022 (CHEERS 2022) Statement: Updated Reporting Guidance for Health Economic Evaluations. Appl Health Econ Health Policy 2022, 20, 781-782. [CrossRef]

- Husereau, D.; Drummond, M.; Augustovski, F.; de Bekker-Grob, E.; Briggs, A.H.; Carswell, C.; Caulley, L.; Chaiyakunapruk, N.; Greenberg, D.; Loder, E.; et al. Consolidated Health Economic Evaluation Reporting Standards 2022 (CHEERS 2022) statement: updated reporting guidance for health economic evaluations. MDM Policy Pract 2022, 7, 23814683211061097. [CrossRef]

- Sroczynski, G.; Siebert, U. Decision analysis for the evaluation of benefits, harms and cost-effectiveness of different cervical cancer screening strategies to inform the S3 clinical guideline “Prevention of Cervical Cancer” in the context of the German health care system.; Leitlinienprogramm Onkologie: 2016.

- DESTATIS. Sterbetafel (Periodensterbetafel): Deutschland, Jahre, Geschlecht, Vollendetes Alter. [Accessed: 23/11/2020]. Available online: https://www-genesis.destatis.de/genesis//online?operation=table&code=12621-0001&bypass=true&levelindex=0&levelid=1606127446797#abreadcrumb (accessed on.

- Nanda K, M.D., Myers Er, Bastian La, Hasselblad V, Hickey Jd, Matchar Db. Accuracy of the Papanicolaou Test in Screening for and Follow-up of Cervical Cytologic Abnormalities: A Systematic Review. Ann Intern Med 2000, 810-819. [CrossRef]

- Mayrand, M.H.; Duarte-Franco, E.; Rodrigues, I.; Walter, S.D.; Hanley, J.; Ferenczy, A.; Ratnam, S.; Coutlée, F.; Franco, E.L. Human papillomavirus DNA versus Papanicolaou screening tests for cervical cancer. N Engl J Med 2007, 357, 1579-1588. [CrossRef]

- Koliopoulos, G.; Nyaga, V.N.; Santesso, N.; Bryant, A.; Martin-Hirsch, P.P.; Mustafa, R.A.; Schunemann, H.; Paraskevaidis, E.; Arbyn, M. Cytology versus HPV testing for cervical cancer screening in the general population. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews 2017, 8, Cd008587. [CrossRef]

- Arbyn, M.; Ronco, G.; Anttila, A.; Meijer, C.J.; Poljak, M.; Ogilvie, G.; Koliopoulos, G.; Naucler, P.; Sankaranarayanan, R.; Peto, J. Evidence regarding human papillomavirus testing in secondary prevention of cervical cancer. Vaccine 2012, 30 Suppl 5, F88-99. [CrossRef]

- Cuzick, J.; Clavel, C.; Petry, K.U.; Meijer, C.J.; Hoyer, H.; Ratnam, S.; Szarewski, A.; Birembaut, P.; Kulasingam, S.; Sasieni, P.; et al. Overview of the European and North American studies on HPV testing in primary cervical cancer screening. Int J Cancer 2006, 119, 1095-1101. [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, M.F.; Schottenfeld, D.; Tortolero-Luna, G.; Cantor, S.B.; Richards-Kortum, R. Colposcopy for the diagnosis of squamous intraepithelial lesions: a meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol 1998, 91, 626-631. [CrossRef]

- Aasbø, G.; Tropè, A.; Nygård, M.; Christiansen, I.K.; Baasland, I.; Iversen, G.A.; Munk, A.C.; Christiansen, M.H.; Presthus, G.K.; Undem, K.; et al. HPV self-sampling among long-term non-attenders to cervical cancer screening in Norway: a pragmatic randomised controlled trial. Br J Cancer 2022, 127, 1816-1826. [CrossRef]

- Kassenärztliche Bundesvereinigung (KBV). Einheitlicher Bewertungsmaßstab (EBM). 2023.

- Hannover Self-Collection Study for cervical cancer prevention (HaSCo Study). German Clinical Trials Register DRKS00019200. Available at: https://drks.de/search/en/trial/DRKS00019200/details. [Accessed: 10/12/2025].

- Armstrong, S.F.; Guest, J.F. Cost-Effectiveness and Cost-Benefit of Cervical Cancer Screening with Liquid Based Cytology Compared with Conventional Cytology in Germany. Clinicoecon Outcomes Res 2020, 12, 153-166. [CrossRef]

- DESTATIS. Volkswirtschaftliche Gesamtrechnungen: Bruttoinlandsprodukt (BIP). [Accessed: 23/01/2024]. Available online: https://www.destatis.de/DE/Themen/Wirtschaft/Volkswirtschaftliche-Gesamtrechnungen-Inlandsprodukt/Tabellen/bip-bubbles.html (accessed on.

- Hunink MGM, W., M. C., Wittenberg, E., Drummond, M. F., Pliskin, J. S., Wong, J. B., Wong, J. B., & Glasziou, P. P. . Decision making in health and medicine: Integrating evidence and values., 2nd ed.; Press, C.U., Ed.; 2014.

- Neumann, P.J.; Thorat, T.; Zhong, Y.; Anderson, J.; Farquhar, M.; Salem, M.; Sandberg, E.; Saret, C.J.; Wilkinson, C.; Cohen, J.T. A Systematic Review of Cost-Effectiveness Studies Reporting Cost-per-DALY Averted. PLoS One 2016, 11, e0168512. [CrossRef]

- Gandjour, A. A Model-Based Estimate of the Cost-Effectiveness Threshold in Germany. Applied Health Economics and Health Policy 2023, 21, 627-635. [CrossRef]

- TreeAge Software, W., MA TreeAge Pro 2021, 2.0; http://www.treeage.com, 2021.

- Östensson, E.; Hellström, A.-C.; Hellman, K.; Gustavsson, I.; Gyllensten, U.; Wilander, E.; Zethraeus, N.; Andersson, S. Projected cost-effectiveness of repeat high-risk human papillomavirus testing using self-collected vaginal samples in the Swedish cervical cancer screening program. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2013, 92, 830-840. [CrossRef]

- Malone, C.; Barnabas, R.V.; Buist, D.S.M.; Tiro, J.A.; Winer, R.L. Cost-effectiveness studies of HPV self-sampling: A systematic review. Prev Med 2020, 132, 105953. [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Patel, S.; Fiorina, C.; Glass, A.; Rochaix, L.; Consortium, C.-S.; Foss, A.M.; Legood, R. A systematic review of the cost-effectiveness of interventions to increase cervical cancer screening among underserved women in Europe. Eur J Health Econ 2023. [CrossRef]

- Tsiachristas, A.; Gittins, M.; Kitchener, H.; Gray, A. Cost-effectiveness of strategies to increase cervical screening uptake at first invitation (STRATEGIC). J Med Screen 2018, 25, 99-109. [CrossRef]

- Vassilakos, P.; Poncet, A.; Catarino, R.; Viviano, M.; Petignat, P.; Combescure, C. Cost-effectiveness evaluation of HPV self-testing offered to non-attendees in cervical cancer screening in Switzerland. Gynecol Oncol 2019, 153, 92-99. [CrossRef]

- O’Mahony, J.F.; Naber, S.K.; Normand, C.; Sharp, L.; O’Leary, J.J.; de Kok, I.M. Beware of Kinked Frontiers: A Systematic Review of the Choice of Comparator Strategies in Cost-Effectiveness Analyses of Human Papillomavirus Testing in Cervical Screening. Value Health 2015, 18, 1138-1151. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Results of the base-case analysis: incremental harm-benefit ratios (IHBR) of the different strategies expressed as additional positive screening results per life years gained. IHBR: incremental harm-benefit ratio, HPV: Human papillomavirus, y: years, LYG: life years gained, Pap: Papanicolaou cytologic examination, Ref: Reference strategy.

Figure 1.

Results of the base-case analysis: incremental harm-benefit ratios (IHBR) of the different strategies expressed as additional positive screening results per life years gained. IHBR: incremental harm-benefit ratio, HPV: Human papillomavirus, y: years, LYG: life years gained, Pap: Papanicolaou cytologic examination, Ref: Reference strategy.

Figure 2.

Results of the base-case analysis: incremental harm-benefit ratios (IHBR) of the different strategies expressed as additional positive screening results per life years gained. IHBR: incremental harm-benefit ratio, HPV: Human papillomavirus, y: years, LYG: life years gained, Pap: Papanicolaou cytologic examination, Ref: Reference strategy.

Figure 2.

Results of the base-case analysis: incremental harm-benefit ratios (IHBR) of the different strategies expressed as additional positive screening results per life years gained. IHBR: incremental harm-benefit ratio, HPV: Human papillomavirus, y: years, LYG: life years gained, Pap: Papanicolaou cytologic examination, Ref: Reference strategy.

Figure 3.

Base-case analyses results: Cost-effectiveness frontiers and incremental cost-effectiveness ratios (ICERs) expressed as Euros per life-year gained [LYG] of evaluated screening strategies. HPV-SS: human papillomavirus self-sampling, ICER: incremental cost-effectiveness ratio, LYG: life years gained, Ref.: reference strategy, y: years.

Figure 3.

Base-case analyses results: Cost-effectiveness frontiers and incremental cost-effectiveness ratios (ICERs) expressed as Euros per life-year gained [LYG] of evaluated screening strategies. HPV-SS: human papillomavirus self-sampling, ICER: incremental cost-effectiveness ratio, LYG: life years gained, Ref.: reference strategy, y: years.

Table 1.

Screening strategies considered in the analyses.

Table 1.

Screening strategies considered in the analyses.

| No. |

Strategy (primary screening test, age, interval) |

| 1. |

No screening |

| 2. |

Reference: Annual Pap cytology at age 20-34 years; Triennial HPV-Pap co-testing age 35 and older, no HPV-SS in non-attendees |

| 3. |

HPV-SS (opt-in) in non-attendees, at age 35, 40, 45, 50, 55, 60 and 65 years |

| 4. |

HPV-SS (opt-in) in non-attendees, at age 30, 35, 40, 45, 50, 55, 60 and 65 years |

| 5. |

HPV-SS (opt-in) in non-attendees, at age 25, 30, 35, 40, 45, 50, 55, 60 and 65 years |

| 6. |

HPV-SS (sent-to-all) in non-attendees, at age 35, 40, 45, 50, 55, 60 and 65 years |

| 7. |

HPV-SS (sent-to-all) in non-attendees, at age 30, 35, 40, 45, 50, 55, 60 and 65 years |

| 8. |

HPV-SS (sent-to-all) in non-attendees, at age 25, 30, 35, 40, 45, 50, 55, 60 and 65 years |

Table 2.

Sensitivity and specificity of different screening tests (sample taken by medical staff).

Table 2.

Sensitivity and specificity of different screening tests (sample taken by medical staff).

| Screening test |

Threshold |

Sensitivity (%) |

95% CI (%) |

Specificity (%) |

95% CI (%) |

Source |

| Pap Cytology |

(ASCUS+)/CIN1+ |

47.1 |

44.8-49.4 |

94.1 |

93.4-94.8 |

Nanda et al. 2000, Mayrand et al. 2007 [25,26] |

| (ASCUS+)/CIN2+ |

55.4 |

33.6-77.2 |

|

|

| (ASCUS+)/CIN3+ |

55.4 |

33.6-77.2 |

|

|

| HPV |

(1 pg/ml)/CIN1 + |

80.6 |

76.3-84.3 |

91.4 |

89.8-92.9 |

Arbyn et al. 2012, Cuzick et al. 2006. Koliopoulos et al. 2017 [27,28,29] |

| (1 pg/ml)/CIN2 + |

96.3 |

94.5-98.1 |

|

|

| (1 pg/ml)/CIN3 + |

98.0 |

97.0-99.0 |

|

|

| HPV + Pap |

(1 pg/ml)/ASCUS+)/CIN1+ |

81.5 |

76.8-84.8 |

88.8 |

85.5-92.1 |

Arbyn et al. 2012, Cuzick et al. 2006. Koliopoulos et al. 2017 [27,28,29] |

| (1 pg/ml)/ASCUS+)/CIN2+ |

99.8 |

99.0-100 |

|

|

| (1 pg/ml)/ASCUS+)/CIN3+ |

99.8 |

99.0-100 |

|

|

Table 3.

Relative Sensitivity and specificity of HPV testing in self-samples compared to sample taken by medical staff.

Table 3.

Relative Sensitivity and specificity of HPV testing in self-samples compared to sample taken by medical staff.

| Screening test |

Threshold |

Relative Sensitivity (95% CI) |

Relative Specificity (95% CI) |

Source |

| HPV-SA |

(ASCUS+)/CIN1 + |

0.85 (0.80 – 0.89) |

0.96 (0.93 – 0.98) |

Arbyn et al. 2018 [7] |

| (ASCUS+)/CIN2 + |

0.85 (0.80 – 0.89) |

|

| (ASCUS+)/CIN3 + |

0.86 (0.76 – 0.98) |

|

| HPV-PCR |

(1 pg/ml)/CIN1 + |

0.99 (0.97 – 1.00) |

0.98 (0.97 – 0.99) |

| (1 pg/ml)/CIN2 + |

0.99 (0.97 – 1.00) |

|

| (1 pg/ml)/CIN3 + |

0.99 (0.96 – 1.00) |

|

Table 4.

Age-specific participation rate in established cervical cancer screening in Germany.

Table 4.

Age-specific participation rate in established cervical cancer screening in Germany.

| Age (years) |

Screening participation (%) |

Source |

| 20 - 29 |

0.79-0.81 |

Kerek-Bodden et al. 2008 [6] |

| 30 - 39 |

0.80-0.78 |

| 40 - 49 |

0.74-0.72 |

| 50 - 59 |

0.69-0.66 |

| 60 - 69 |

0.62-0.55 |

| 70 - 79 |

0.43-0.32 |

| 80 + |

0.17 |

Table 5.

Aggregated costs of screening, staging, diagnostics, treatment and follow-up procedures (index year 2023).

Table 5.

Aggregated costs of screening, staging, diagnostics, treatment and follow-up procedures (index year 2023).

| Procedure |

Cost (2023 Euros) |

| Clinician-based screening |

|

| Pap Screening at ages 20 – 34 including examination and cytology (EBM 01761, EBM 01762) |

34.02 |

| HPV-Pap co-testing at age 35 or older including examination, cytology, HPV test (EBM 01761, EBM 01762, EBM 1764) |

53.33 |

| HPV self-sampling (HPV-SS) testinga

|

29.74 |

| Follow-up diagnostic proceduresb |

|

| Pap Screening at ages 20 – 34 years: HPV-triage after abnormal finding including follow-up diagnostics, HPV, laboratory (EBM 1764, EBM 01767) |

30.00 |

| HPV-Pap co-testing at age 35 or older including follow-up diagnostics, cytology, HPV, laboratory (EBM 1764, EBM 1766, EBM 01767) |

63.10 |

| HPV-SS positive: follow-up by a physician including follow-up diagnostics, cytology, laboratory (EBM 1764, EBM 1766) |

43.79 |

| Colposcopy after abnormal findings including follow-up colposcopy, biopsy, histology (EBM 01765, EBM 01768) |

112.16 |

| Treatment |

|

| Conization (EBM 31301, 31821, 31695, 31502) and Follow-up at month 12 and 24 (EBM 01764, 01766, 01767, 33044) with assumption of 8% reconization rate (EBM 31303, 31823, 31697, 31505) |

468.53 |

| Therapy FIGO Ic

|

9,687.31 |

| Therapy FIGO IIc

|

14,620.44 |

| Therapy FIGO IIIc

|

15,799.27 |

| Therapy FIGO IVc

|

13,547.57 |

| Follow-up proceduresd after cancer therapy, year 1, 2 and 3 after therapye

|

646.80 |

| Follow-up proceduresd after cancer therapy, year 4 and 5 after therapyf

|

323.40 |

| Follow-up proceduresd after cancer therapy, year 6 after therapy |

161.70 |

| Palliative careg

|

9,574.08 |

Table 6.

Base-case analysis results: Discounted total lifetime costs (in Euros), life expectancy (in years), and the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER; in Euros per life-year gained [LYG]) for different screening strategies.

Table 6.

Base-case analysis results: Discounted total lifetime costs (in Euros), life expectancy (in years), and the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER; in Euros per life-year gained [LYG]) for different screening strategies.

Strategy

(screening interval, age at start-end)

|

Discounted costs |

Discounted incremental costs |

Discounted life expectancy |

Discounted incremental life expectancy |

Discounted ICER |

| (2023 Euros) |

(2023 Euros) |

(LY) |

(LYG) |

(Euros/

LYG)

|

| Ref: screening, no HPV-SS |

631.28 |

|

29.072744 |

|

--- |

| HPV-SS (opt-in), 5yr, age 35-65 |

634.90 |

3.62 |

29.072904 |

0.000160 |

22,681 |

| HPV-SS (opt-in), 5yr, age 30-65 |

635.79 |

0.89 |

29.072906 |

0.000001 |

ext. dom. |

| HPV-SS (opt-in), 5yr, age 25-65 |

636.79 |

1.00 |

29.072906 |

0.000001 |

ext. dom. |

| HPV-SS (send-to-all), 5yr, age 35-65 |

638.43 |

3.53 |

29.073041 |

0.000136 |

25,918 |

| HPV-SS (send-to-all), 5yr, age 30-65 |

640.14 |

1.71 |

29.073043 |

0.000002 |

725,973 |

| HPV-SS (send-to-all), 5yr, age 25-65 |

642.07 |

1.93 |

29.073044 |

0.000001 |

1,778,352 |

Table 7.

Sensitivity analysis results: Impact of variation of compliance after positive HPV test on the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (in Euros per life-year gained [LYG]) for different HPV-Self Samling (HPV-SS) screening strategies.

Table 7.

Sensitivity analysis results: Impact of variation of compliance after positive HPV test on the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (in Euros per life-year gained [LYG]) for different HPV-Self Samling (HPV-SS) screening strategies.

| |

ICER (EUR/LYG) |

| |

Compliance after a positive HPV test |

| Strategy |

100%

(base case) |

70%

|

50%

|

30%

|

10%

|

| Ref: screening, no HPV-SS |

--- |

--- |

--- |

--- |

--- |

| HPV-SS (opt-in), 5yr, age 35-65 |

22,681 |

27,931 |

35,552 |

54,153 |

149,596 |

| HPV-SS (opt-in), 5yr, age 30-65 |

ext. dom. |

ext. dom. |

ext. dom. |

ext. dom. |

ext. dom. |

| HPV-SS (opt-in), 5yr, age 25-65 |

ext. dom. |

ext. dom. |

ext. dom. |

ext. dom. |

ext. dom. |

| HPV-SS (send-to-all), 5yr, age 35-65 |

25,918 |

32,087 |

41,018 |

62,773 |

174,232 |

| HPV-SS (send-to-all), 5yr, age 30-65 |

725,973 |

855,556 |

1,048,840 |

1,526,224 |

3,989,929 |

| HPV-SS (send-to-all), 5yr, age 25-65 |

1,778,352 |

2,080,591 |

2,532,575 |

3,650,790 |

9,428,232 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).