1. Introduction

The treatment of Diffuse midline glioma (DMG) which is a fatal pediatric high-grade glioma (pHGG) is a global challenge [

1,

2]. According to 2016 updated Central Nervous System World Health Organization (WHO) classification, pHGG covers all pediatric gliomas that are classified as ‘grade 3’ or ‘grade 4’ [

3]. DMG is mostly diagnosed in the midline of the brain especially in the pons and historically referred to as diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma (DIPG/DMG). Due to the anatomical localization of the tumor and its infiltrative growth characteristics, surgery remains particularly challenging, and radiotherapy is the only standard treatment providing symptoms relief and a significant delay in disease spread and progression [

4,

5]. DIPG/DMG represents 10-15% of all pediatric brain tumors and is a leading cause of death in children with brain tumors. DIPG patients face an extremely poor median overall survival (OS) up to 12 months and about 90% of children die within two years of initial diagnosis and less than 1% survive after 5 years.

In the last decades, distinct pHGG entities have been identified based on recurrent epigenetic alterations [

6]. Tyrosine kinases have been proposed as molecular targets in DIPG. The H3.1 or H3.3 variants (HIST1H3B/C and H3F3A) of the Histone H3, altering the epigenetic landscape of precursor astrocyte or primitive oligodendrocyte cells of the pontine region of the brainstem are the common somatic mutations in this disease. H3K27M co-occur with alterations in the cascade of signaling genes, including the extracellular receptor tyrosine kinases (KIT/MET/EGFR/PDGFR/VEGFR), cyclin-dependent kinases (CDKs1/4/6), activin A receptor (ACVR1), transcriptional regulators (MYCN) and tumor suppressors (PTEN/TP53) genes, and intracellular kinases (PI

3K/AKT/mTOR) [

7]. Among those, mTOR emerged as targetable molecular pathways across DIPG patient models, using a blood-brain barrier penetrant PI3K/Akt/mTOR inhibitors like paxalisib. This drug potentiates calcium-activated PKC signaling, and in combination with the brain penetrant protein kinase C (PKCb) inhibitor enzastaurin, prolonged the survival of multiple orthotopic patient-derived and immunocompetent allograft models [

8]. Based on these encouraging results, in the present work, we investigated the antiproliferative effects of TKI targeting different tyrosine kinases such as everolimus (mTOR), crizotinib (ALK/HFGR), dasatinib (ABL/PTKSrc/EAR2), erlotinib (EGFR), lapatinib (EGFR/RTKErbB2), perifosine (Pi3K-AKT1) and midostaurin (FLT3/PDGFR/VEGFR/PKCa/c-Syk, c-Fgr/c-Kit and CDK1) in SU-DIPG-36 and SU-DIPG-50 cells. Midostaurin has also been reported as a potent antiproliferative drug in high through screening (HTS) in different SU-DIPG-cells after 72h of incubation [

8]. Here, we describe the pharmacological investigation conducted on two patient autopsy-derived DIPG cell cultures (SU-DIPG-36, SU-DIPG- 50) (Dr Michelle Monje). Specifically, SU-DIPG-36 cells are H3.1K27M mutated cells and SU-DIPG-50 are H3.3K27M mutated cells selected as representatives of diverse DIPG pathological characteristics and conditions. Specifically, they respond differently to ONC201 [

2] and are characterize by the predominant molecular profile (SU-DIPG-36 has H3.1K27M, whereas SU-DIPG-50 has H3.3K27M) of the patients diagnosed with DIPG. In addition, these two cell lines derived from DIPG patients were selected to investigate unexplored DIPG biochemical pathways to identify new therapeutic strategies for the treatment of DIPG.

Ion channels and transporters are up-regulated in 33% and down- regulated in 48% of cases in pediatric tumor brain and can be a novel target in cancer [

9]. This macromolecular complex and transporters have a role in cell division [

10] and are increasingly considered to be of pathophysiological relevance in tumor biology [

11,

12]. Although these proteins are inherent in brain functioning (neuronal and glial) and dysregulated in brain tumors [

13,

14,

15], currently no data is available on genes encoding ion channels and transporters and their relevance in DIPG.

We recently found that repaglinide is very effective in reducing cell proliferation and apoptosis in either SU-DIPG-36 and SU-DIPG-50 cells and the effects were associated with histone deacetylase modulation; this makes it an interesting candidate in the study, also with regard to its known action on KATP channels, where it acts as a blocker of ATP-dependent potassium channels [

16]. KATP - ATP-sensitive potassium channel - is a type of potassium channel that is gated by intracellular nucleotides, ATP and ADP. The channel is an octameric complexes of inwardly rectifier potassium channel family Kir6.1 and Kir6.2 subunits and of the sulfonylurea’s receptor type 1 SUR1 and type 2 SUR2. These channels are specifically modulated by class of drugs known as KATP channel openers like diazoxide and inhibited by sulfonylureas repaglinide and glibenclamide [

17,

18,

19]. A high expression of

ABCC8 gene encoding for the SUR1 subunit has been reported in patients with glioma with longer survival rate and response to temozolomide [

20], and in glioma cells regulating ERK [

21]. In our experiments we also found a capsaicin and capsazepine sensitive ion channel currents in SU-DIPG-36 and SU-DIPG-50 cells; the TRPV1 channel modulators affect cell proliferation [

16]. The Transient Receptor (TRP) channels have a role in cancers. They mostly carry Ca

2+ ions with a role in cell proliferation, apoptosis, and resistant mechanisms. The downregulation of the family members:

TRPM3 (melastatin 3), TRPV1 (vanilloid 1), TRPV2 (vanilloid 2), and

TRPML1 (

mucolipin 1) gene expression has been found inversely correlated with tumor grade increases suggesting their prognostic marker for glioblastoma patients [

22], in particular the

TRPV1V3 variant mRNA is correlated with the survival rate of these patients [

23]. The TRPV1- transient receptor potential cation channel subfamily V member 1, is also known as the capsaicin receptor, a member of the TRPV group of the TRP channels that are drug targets [

24]. The function of TRPV1 is detection and regulation of body temperature and analgesic response to thermal stimulus [

25]. In this respect, we found that the TRPV1 channel agonist capsaicin 1 µM and the antagonist capsazepine 1 µM, caused respectively, +26% and −15% changes in cell proliferation after 6h of incubation in SU-DIPG-36 cells. Higher concentrations of 20 µM capsaicin caused a mild reduction in cell proliferation of −17% in this cell after 48 h of incubation [

16]. In DIPG-50 cells, the TRPV1 agonist capsaicin reduced cell survivals by -35% after 72h of incubation while capsazepine was not effective [

16] in line with positive prognostic role of the TRPV1 gene observed in glioblastoma [

22,

23].

The effects of TKI on SU-DIPG cells were studied in 96 multi-wells crystal violet, CCK-8 assays, and clonogenic assays. The most effective TKI found in cell proliferation experiments was tested on ion channel currents by patch-clamp. The response of the TKI sensitive currents to KATP channel inhibitors such as glibenclamide, repaglinide and Ba2+ ions, and to TRP inhibitors such as ruthenium red and capsazepine were evaluated in the same cells. The effects of the most effective TKI in different cell proliferation assays on cell death signaling and target proteins were investigated by western blot in these cells.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cell Culture

Patient-derived diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma (DIPG) cell cultures (DIPG-36 and DIPG-50) were supplied by Dr. Michelle Monje with approval from the Stanford University Institutional Review Board. These cells were cultured as a monolayer in Tumor Stem Media (TSM), which is a 1:1 mixture of DMEM/F12 (Invitrogen) and Neurobasal (-A) (Invitrogen), supplemented with B27 (-A) (Life Technologies). The medium also included human basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF) at 20 ng/ml, recombinant human epidermal growth factor (EGF) at 20 ng/ml, platelet-derived growth factor-AA (PDGF-AA) at 10 ng/mL, PDGF-BB at 10 ng/mL (Life Technologies), and heparin at 20 ng/mL (StemCell Technologies). Cells were maintained at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere.

2.2. Multi-Wells Crystal Violet Staining Test

Cells were seeded on a 96-well plate at a density of 8 x 10

3 cells. After 24 hours, increasing concentrations of each drug were added. Following incubation periods of 48 and 72 hours, the medium was removed, and cells were fixed with 10% buffered formalin for 20 minutes at 18-20 °C. They were then stained with 1% crystal violet (CV) for 30 minutes and analyzed at a wavelength of 560 nm. Each condition was performed at least four times. This procedure aims to quantify live, adherent cells in culture, as crystal violet binds to DNA and cell proteins [

16].

2.3. CCK-8 Intracellular Dehydrogenase Assay

The activity of intracellular dehydrogenases was measured using the Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8) (Sigma-Aldrich), which employs water-soluble tetrazolium salt [

16]. Cells were counted and seeded into 96-well plates at a density of 8 x 10

3 cells per well, then pre-incubated for 24 hours under standard conditions. Subsequently, cells were treated for 48 and 72 hours with different concentrations of each drug.

2.4. Clonogenic Assay

Clonogenic assay aimed to assess the cells’ ability to form colonies. Cells, seeded onto 60 mm plates in a population of 250 cells/plate, were counted using the Scepter 2.0 cell counter. After a 24-hour pre-incubation, we examined how the substance affected colony formation after 72 hours. Each condition was tested in triplicate. Following treatment, the culture medium containing the cytotoxic compound was replaced with fresh, drug-free medium, and cells were cultured for an additional two weeks. Colony analysis was performed using OpenCFU 3.9.0 (My Biosoftware, USA), supplemented by manual counts from three operators, with the average taken for final results [

26].

2.5. Impedentiometric Cell Count and Volume Assay

The cells size and count were performed using the Scepter™ 2.0 cell counter (MERK- Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA).

2.6. Protein Analysis by Western Blot

Western Blot was conducted using whole cell lysates, following the previously described method [

16]. To identify apoptotic markers, Cell Signaling Technology reagents were employed. The detection of immunoreactive bands involved horseradish peroxidase-labelled secondary anti-rabbit IgG and anti-mouse IgG (Cell Signaling Technology), along with enhanced chemiluminescence (Pierce, Thermo Fisher Scientific). Details are provided in

Table S1 for mAb. Images and densitometry data were analyzed with Image Lab software (Bio-Rad).

2.7. Whole-Cell Recordings in the Cells

Ion channel currents in DIPG cells were measured using whole-cell patch clamp by applying a depolarization protocol. The potentials ranged from −100 to +180 mV (Vm) in 20 mV steps, with the holding potential (HP) set at −60 mV (Vm) and included asymmetrical K+ ion concentrations. Recordings were performed at room temperature (20–22 °C) with a sampling rate of 2 kHz (filtering at 1 kHz) using an Axopatch-1D amplifier paired with a CV-4 head-stage (Axon Instruments, Foster City, CA, USA). Patch pipettes were pulled from PG52165-4 #8250 glass capillaries, measuring 1.65 mm outer diameter and 1.20 mm inner diameter (World Precision Instruments, 175 Sarasota Center Blvd., Sarasota, FL, USA), using a vertical puller (PP-82 Narishige, Tokyo, Japan) to achieve a resistance of 4–5 MΩ. Cells that did not form a seal with resistance greater than 1 GΩ were not considered for the analysis.

2.8. Drugs and Solution

Ion channel activators and inhibitors such as glibenclamide (GLIB), repaglinide (REPA), tetraethylammonium chloride (TEA), Ba2+ ions, ruthenium red (RR), and capsazepine (CAPSZ) were sourced from Sigma (Sigma-Aldrich, Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany, Italy). Stock solutions of GLIB, REPA, TEA, BaCl2, and CAPSZ were prepared by dissolving each compound in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) at concentrations of 118.6x10-3 M; RR was dissolved in water. During experiments, tested substances included everolimus (EVE), dasatinib (DASA), perifosine (PERIF), crizotinib (CRIZO), lapatinib (LAPA), erlotinib (ERLO), and midostaurin (MIDO). Their stock solutions were made by dissolving each drug in DMSO and stored at -20 °C. Dilutions with DMEM (Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium) provided solutions at required concentrations, prepared on the experiment day and kept at room temperature.

For patch clamp experiments, small volumes of these stock solutions were added to the bath solutions provided by different protocols. DMSO concentration did not exceed 0.07%, which typically does not influence ion channel current or cell proliferation. The bath solution comprised 142 mM NaCl, 2.8 mM KCl, 1 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MgCl2, 11 mM glucose, and 10 mM HEPES (pH 7.4). The pipette solution included 132 mM K+-glutamate, 1 mM EGTA, 10 mM NaCl, 2 mM MgCl2, 10 mM HEPES, 1 mM Na2ATP, and 0.3 mM Na2GDP (pH 7.2).

2.9. Data Analysis and Statistics

Statistical results are shown as mean ± SEM. Data collection and analysis were conducted using Excel (Microsoft Office 2010) and GraphPad Prism 8 to calculate IC50, Emax, and Hill slope through curve fitting algorithms. Significant differences between two group means were determined with p values < 0.05 using Student’s t-test. Additionally, one-way ANOVA was employed to compare the means of three or more groups, assessing whether at least one differs significantly. This test was used to examine differences across independent groups and within groups to analyze variations in means within the same group. Patch-clamp data acquisition and analysis were carried out using the pCLAMP 10 software suite (Axon Instruments, Foster City, CA, USA).

SCOPUS search database key words: drug name AND DIPG AND “diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma” AND “Diffuse midline glioma” AND DMG.

3. Results

3.1. Effects of TKI (Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors) in “In Vitro” Cell Viability Experiments on SU-DIPG-36

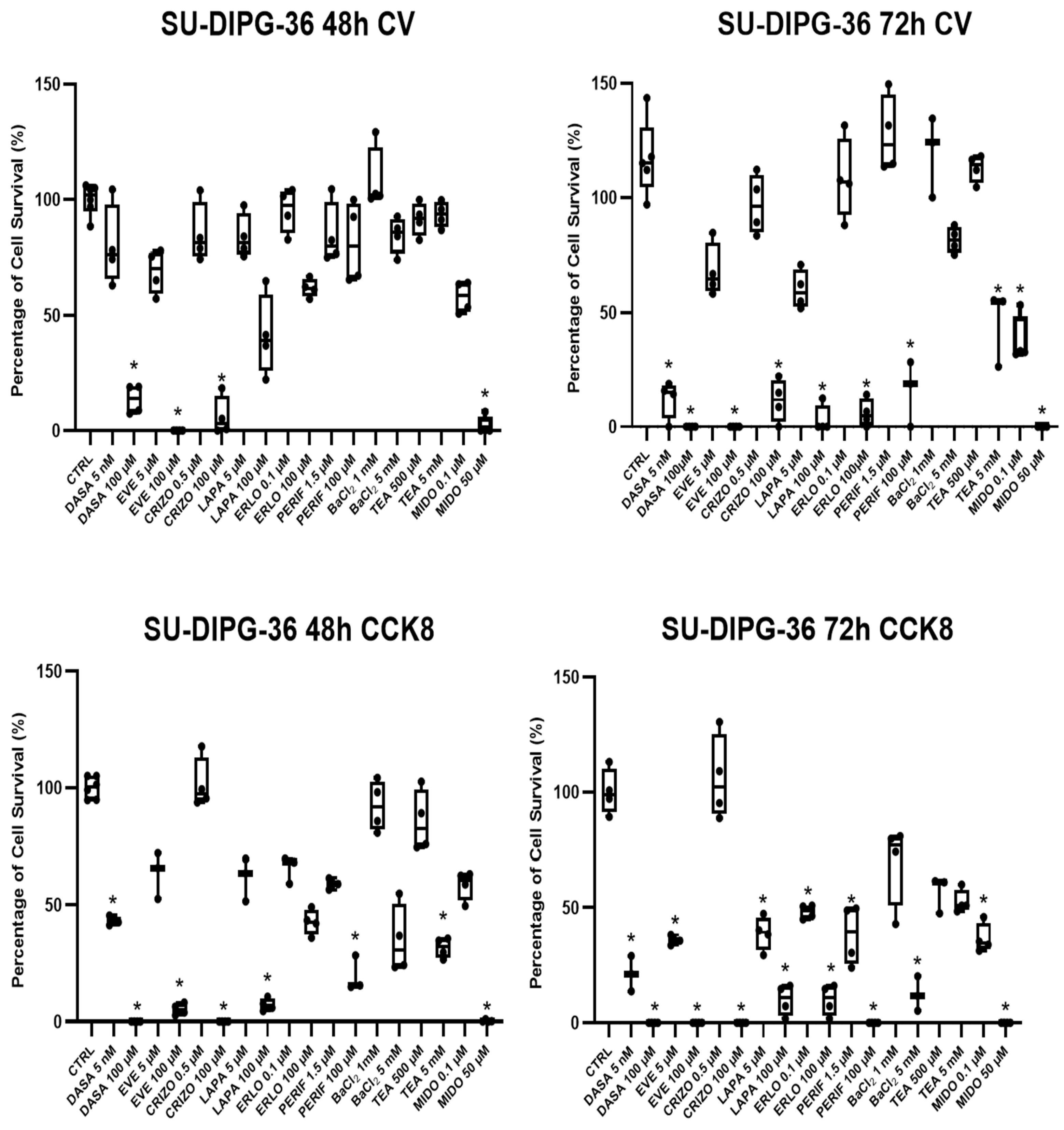

The antiproliferative effect of different TKI were investigated in neuronal SU-DIPG-36 in CV and CCK-8 assays in the range of concentrations of 0.001-100 mM. Crystal violet labels nuclear DNA fixing adherent cells while CCK-8 assay is a functional assay and the cell count is based on evaluation of mitochondrial dehydrogenase activity. The Crystal Violet (CV) assay and the CCK-8 assay measure different parameters of cell viability, which is why they can give divergent results. CV quantifies adherent cells but does not provide information on their functional status. CCK-8, instead, detects metabolic activity through the reduction of WST-8 by intracellular dehydrogenases: the signal may decrease due to metabolic inhibition even in the absence of cell loss, or be relatively high if few cells remain metabolically active. This can explain why in some experiments we obtain different results for the same drugs tested with different assays.

DASA 100 μM, EVE 100 μM, CRIZO 100 μM and 50 μM MIDO were markedly effective in CV assay after 48 h of incubation time, decreasing cell survival. After 72 h of incubation time the effects were also observed with PERIF 100 μM, LAPA 100 μM, ERLO 100 μM and with low concentrations of DASA 5 nM and MIDO 0.1 μM (

Figure 1). In CCK-8 assay, the effects of the TKI were also markedly observed (

Figure 1). The unselective blocker of potassium channels, TEA, and the inwardly rectifier potassium (Kir) channels blocker, Ba

2+ ions, concentration-dependently reduced cell proliferation in particular in CCK-8 assays. TEA also blocks calcium activated K

+ channels (BK) and aquaporin channels.

In some cases, we can see an increase in cell viability between 48h and 72h incubation times, in experiments where cells are treated with low drug concentrations and prolonged incubation time, as for PERIF (1.5 µM), ERLO (0.1 µM) and BaCl2 (1 mM). This may be due to the fact that low concentrations of drugs may not be sufficient to inhibit growth but, on the contrary, may induce an adaptive response that stimulates survival over time.

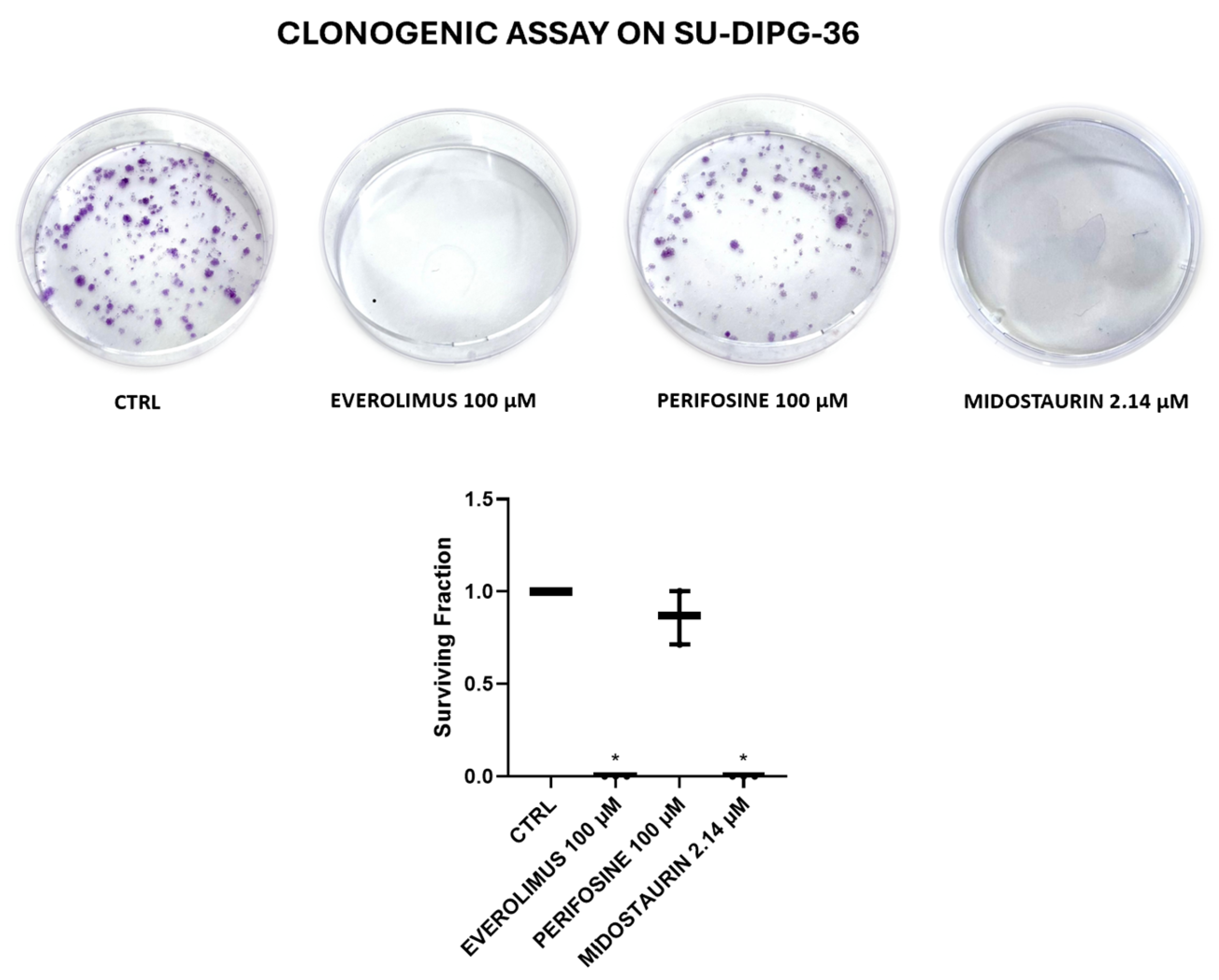

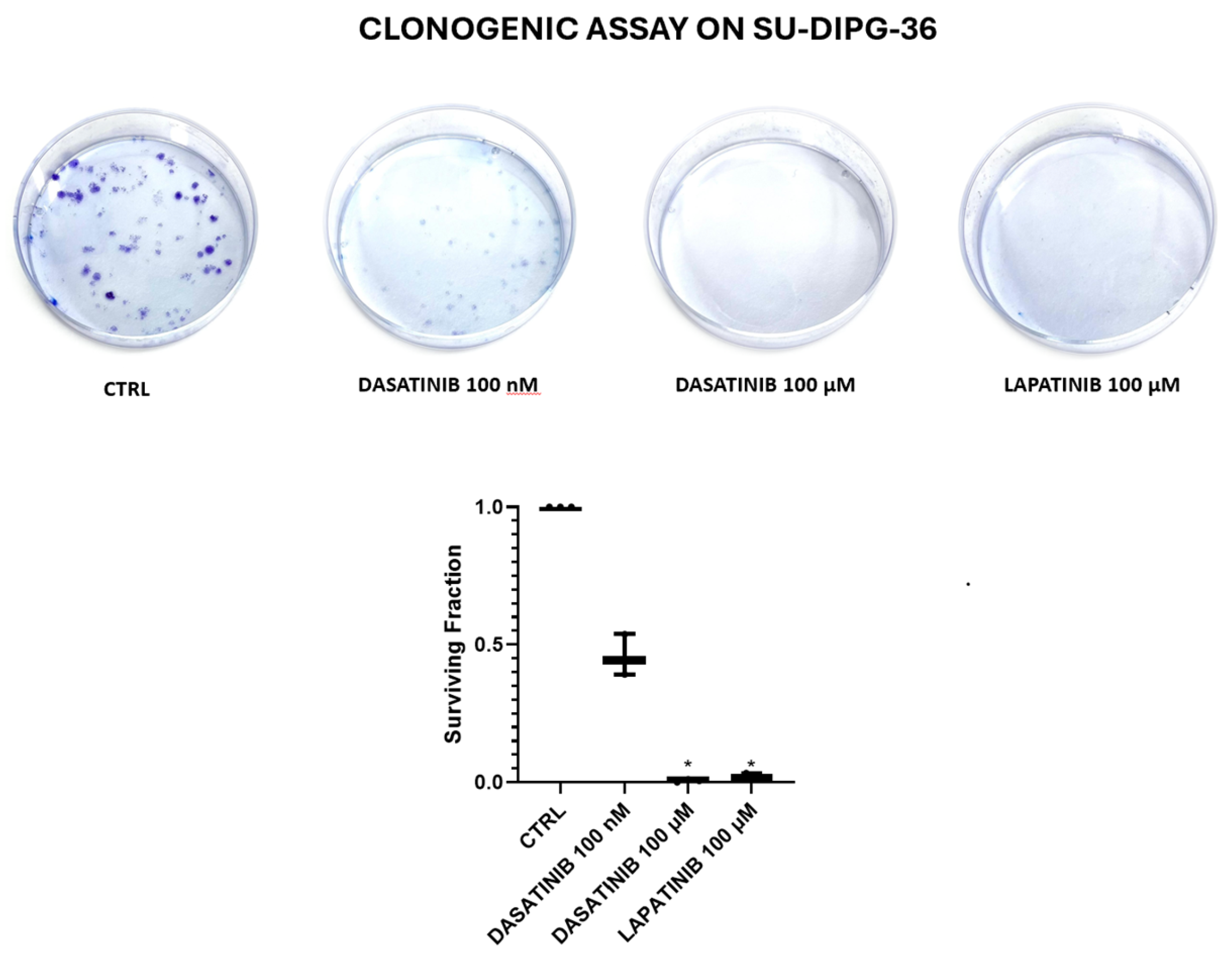

3.2. Clonogenic Assay on SU-DIPG-36 Performed to Investigate Substances Demonstrating Greater Efficacy

In clonogenic assay on SU-DIPG-36 cells, 2.14 μM MIDO and 100 μM, EVE fully reduced the number of colonies after 72h of incubation time following washout of the drug solution but not 100 μM PERIF (

Figure 2;

Table 1). LAPA and DASA at 100 μM concentrations were fully effective in this assay, and DASA also at nanomolar concentration (

Figure 3;

Table 2).

Midostaurin, which was already proven to be effective at low concentrations in crystal violet and CCK-8 assays, completely eliminated colony formation at 2.14 µM, with no detectable colonies in the clonogenic assay. This result indicates that the minimum concentration required to achieve the maximum effect is ≤ 2.14 µM in the cell line tested. Testing 100 µM for midostaurin in clonogenic assay would not provide new information on efficacy parameters; so, it is therefore reasonable to omit concentrations much higher than those already reaching maximum effect. Instead, with the other substances tested, higher concentrations are required to achieve the maximum effect, which is why the 100 μM concentration had to be tested for the other drugs in clonogenic assay.

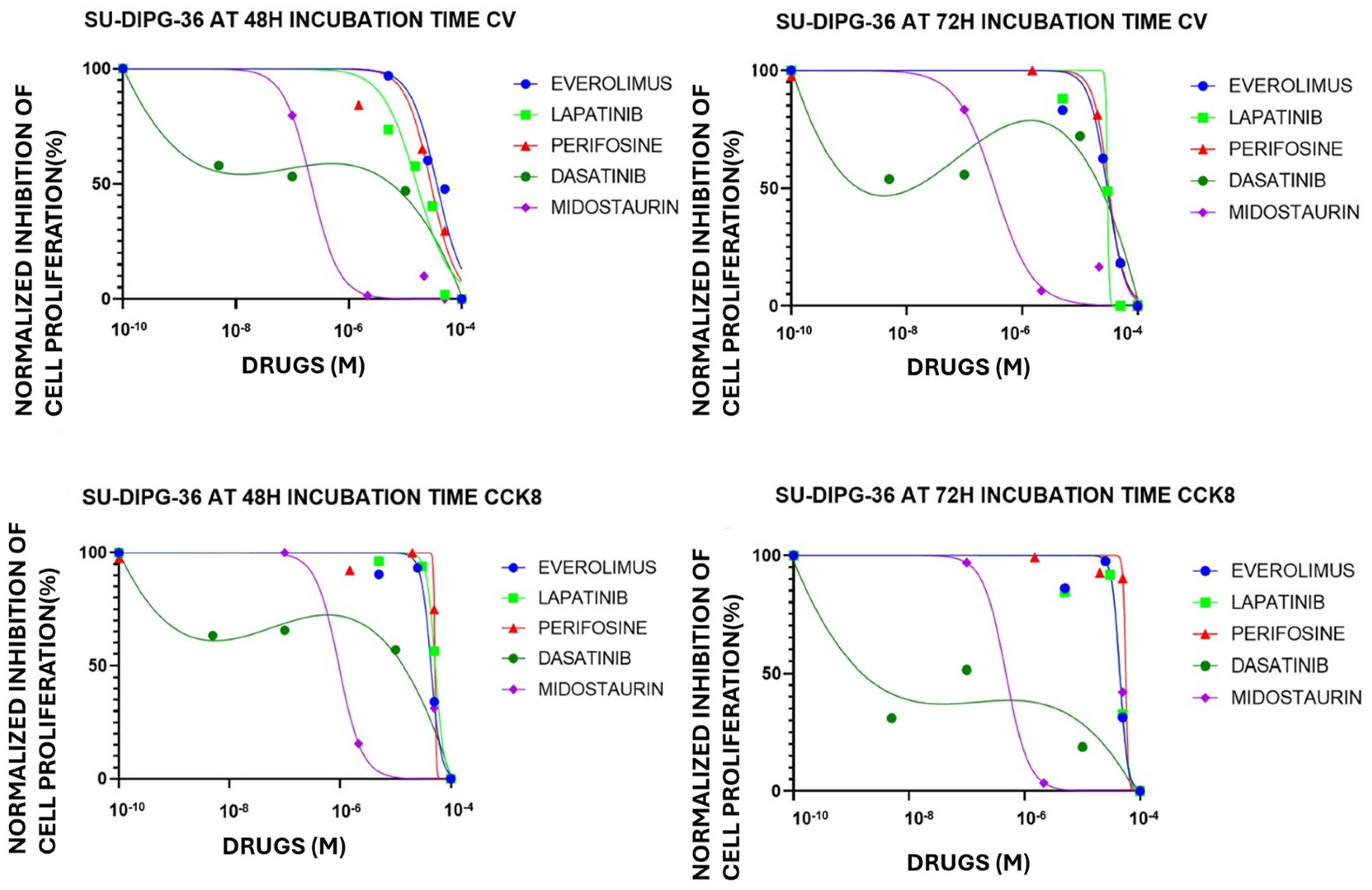

3.3. TKI-Induced Concentration-Dependent Inhibition of Cell Proliferation in SU-DIPG Cells

A concentration-dependent reduction of cell proliferation was observed with EVE, LAPA, PERIF, CRIZO, and ERLO (0.01-100 μM) in the micromolar ranges. But MIDO and DASA (0.001-100 μM) at all investigated incubation times reduced cell viability at lower concentrations (

Figure 4). MIDO was the most potent TKI in SU-DIPG-36 cells showing a monophasic concentration-response relationships vs other drug. While the concentration-dependent response of DASA was biphasic with lower efficacy at higher concentrations (

Figure 4;

Table 3).

The biphasic concentration-response relationship of DASA suggests that dasatinib may have different dose-dependent effects, possibly affecting multiple targets with different affinities. At very low concentrations, inhibition of a high-affinity target induces strong cytotoxicity. At intermediate concentrations, compensatory or adaptive pathways may be activated, that partially saves cells viability, reducing apparent inhibition. At high doses, simultaneous inhibition of multiple kinases or non-specific effects restore complete suppression of proliferation, creating what we consider a biphasic effect.

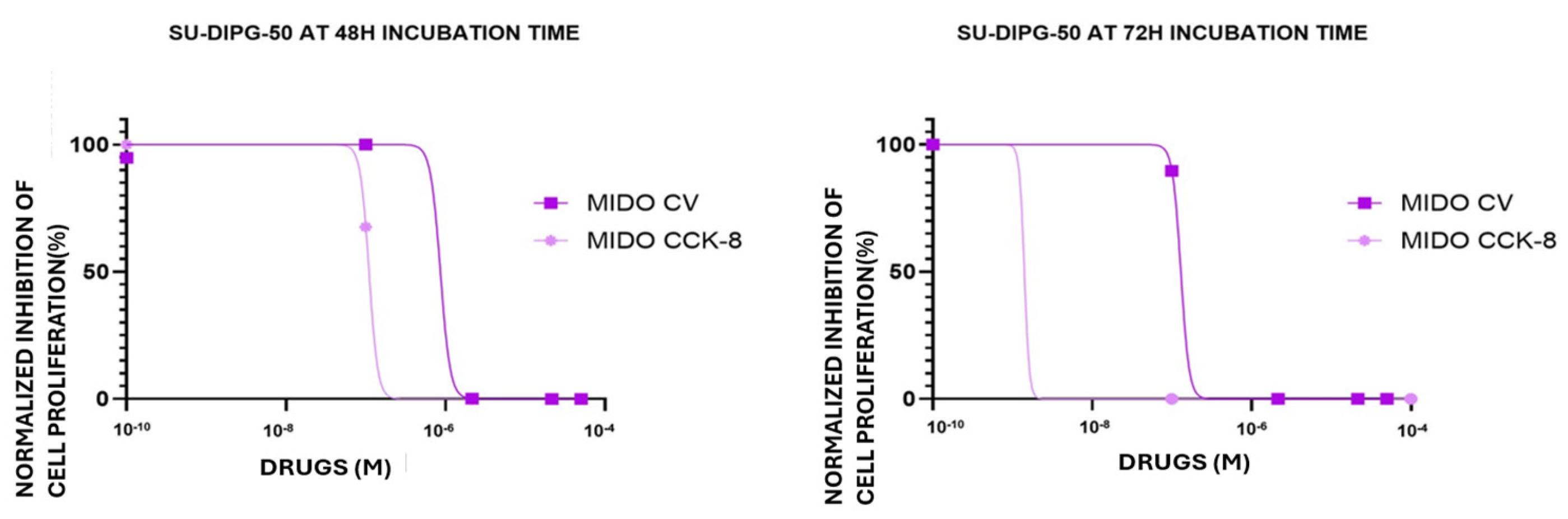

MIDO was therefore investigated in SU-DIPG-50; we found that it caused a -80.8±8% and -100% of cell proliferation after 48 h and 72 h of incubation time, respectively. Concentration-response curve fitting analysis revealed that the IC

50 (M) to reduce cell proliferation were in sub micromolar concentrations ranges in all experimental conditions and in nanomolar concentration in the CCK-8 assay (

Figure 5;

Table 4) after 72 h.

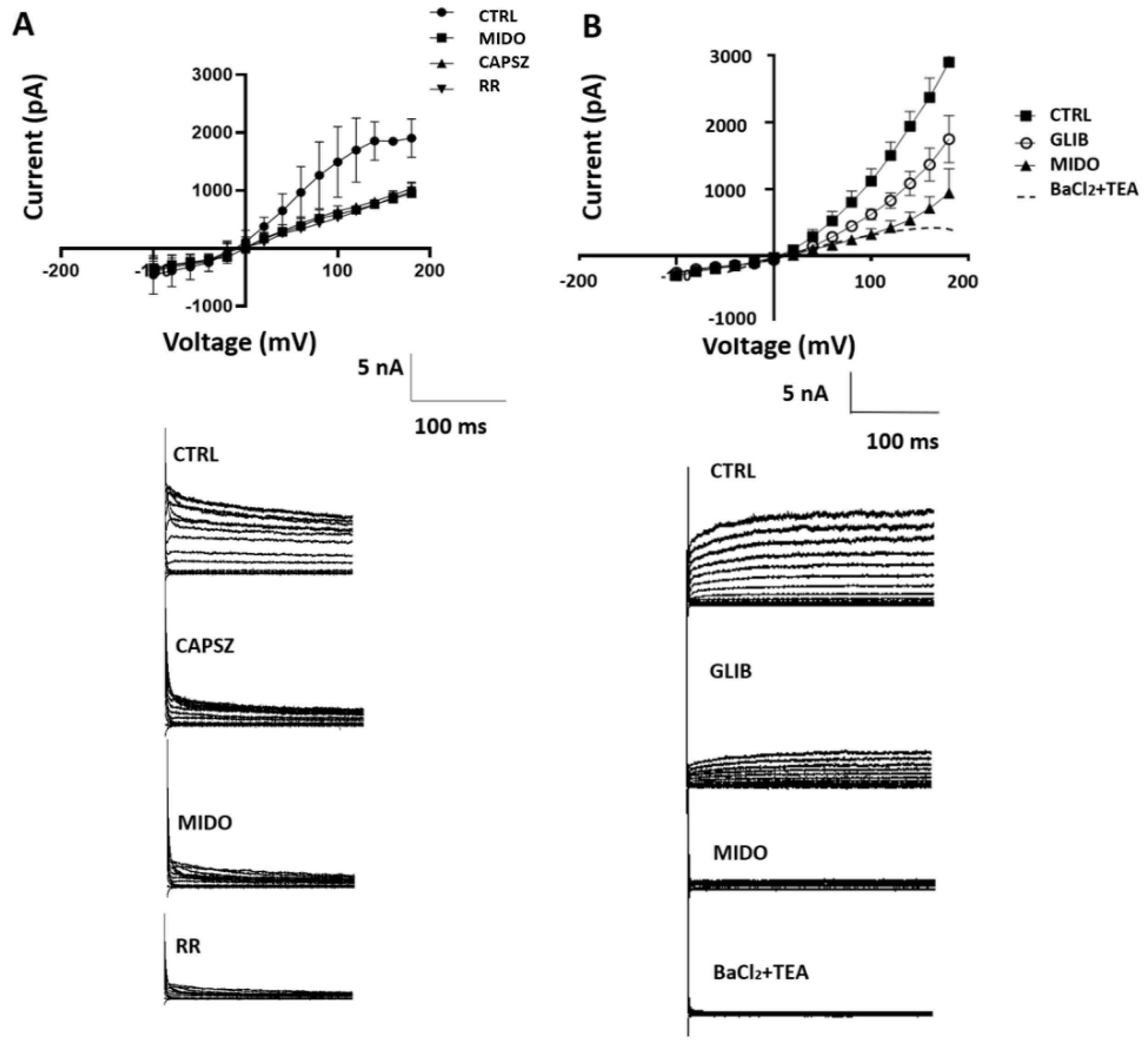

3.4. Mechanism of Actions of MIDO in SU-DIPG Cells: Characterization of Channel Currents in SU-DIPG Cells

Whole cells currents with hyperbolic current–voltage relationship can be recorded in in both cell types in physiological K

+ ion concentrations. The SU-DIPG-36 cells (N cells = 30) had a resting potential of -11.2±12 mV (Vm), capacitance of 4.02±7 pF. Patch-clamp investigations showed that the TRPV1 antagonist 10 μM CAPSZ reduced the control currents (

Figure 6A) (N cells= 10) of -60%±9 at +40 mV (Vm) and -49%±9 at +100 mV (Vm). The addition of MIDO reduced the CTRL currents that were CAPSZ -sensitive of -48%±10 at +80 Vm (Vm) in the cells (

Figure 6A). The CTRL currents were further reduced by the unselective TRP antagonist 10 μM RR. 100 μM GLIB also reduced the CTRL currents in these cells (N cells=20) that were further reduced by MIDO (

Figure 6B); these currents were fully reduced by TEA-BaCl

2 that are not selective K

+ channel blockers (

Figure 6B).

These findings suggest that MIDO reduced CTRL currents is due to inhibition of TRPV1 and KATP channels in the SU-DIPG-36 cells.

Although we are dealing with the same cell type in these experiments, we can see that the control current trend between +150 and +200 mV is slightly different, which may depend on intrinsic cell variability, as the trend remains the same in the rest of the range.

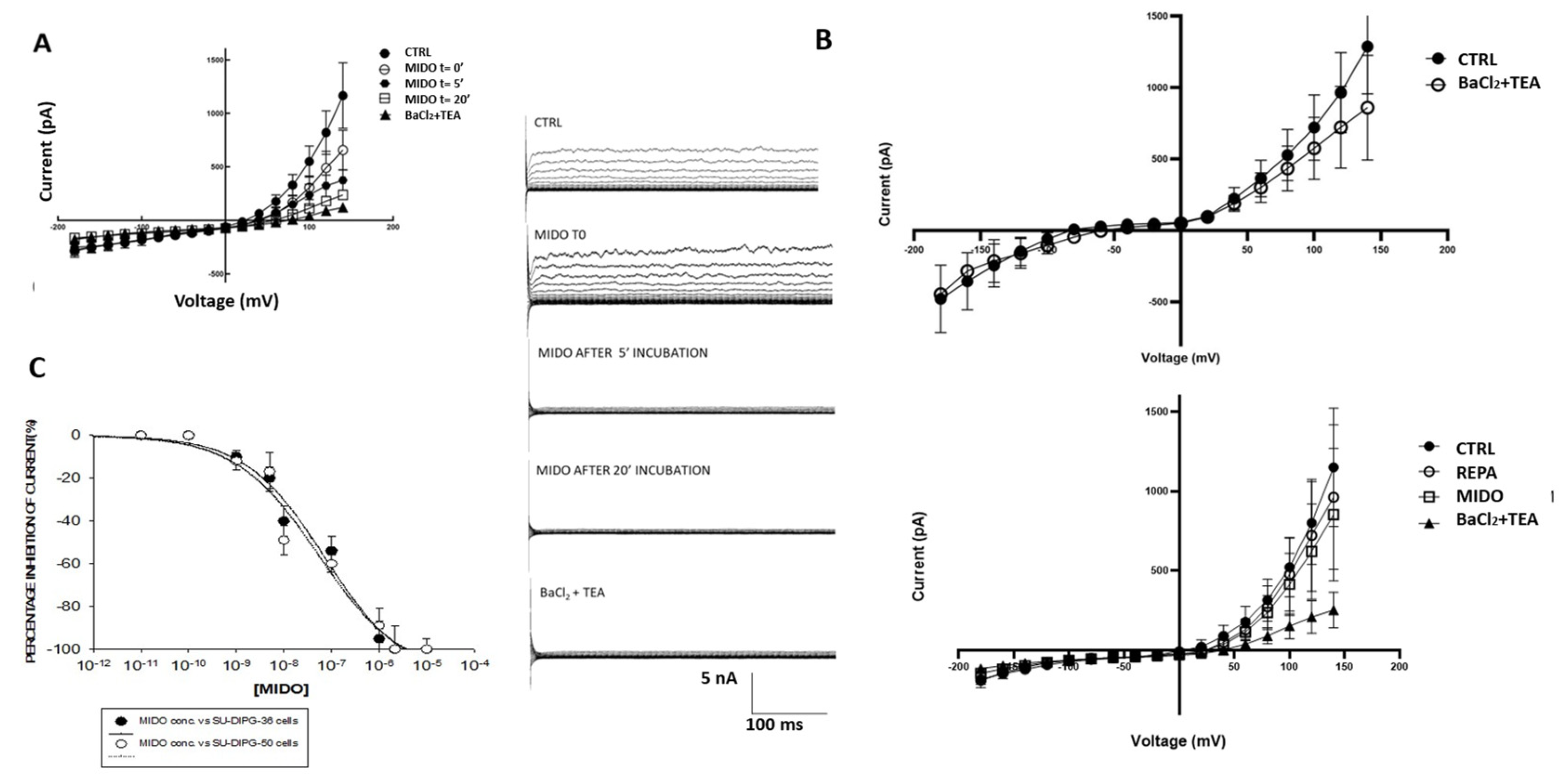

On some SU-DIPG-50 cells (N cells= 3) with resting of +20±9 mV (Vm) and capacitance of 8±11 pF, 2.14 μM MIDO reduced currents vs controls at positive membrane potential after 20 min of incubation time, but at t= 0 failed to inhibit this current at negative potentials. An increasing inhibitory effect was observed during time on these same cells, at positive potentials (

Figure 7A). SU-DIPG-50 cells were therefore markedly depolarized with I/V crossing the voltage axis at +23±8 mV (Vm) and a membrane capacitance of 3.02±10 pF (N cells= 4) were sensitive to REPA, the KATP channel inhibitor, and MIDO (

Figure 7B).

We also found some cells (N cells = 3) with hyperbolic current-voltage relationships crossing the I/V at -90±8 mV (Vm) (membrane capacitance of 3.01±8 pF) close to equilibrium potential for K

+ ions like normal neurons that were sensitive to 5 mM BaCl

2 and 10 mM TEA (

Figure 7B).

The fact that BaCl2+TEA shows a slightly different trend among the panels presented is related to the treatments carried out before BaCl2+TEA, which certainly modify the electrical state of the cell.

Concentration-response analysis calculated an IC

50 M of MIDO of 7.13x10

-8 M (Hill slope=-0.5) on SU-DIPG-36 cell current and of 6.9x10

-8 M(Hill slope=-0.45) on SU-DIPG-50 cell current (

Figure 7C).

Table 5.

Changes in percentage (%) of CTRL current, after the application of MIDO at t= 0 and after 5 and 20 minutes of incubation times.

Table 5.

Changes in percentage (%) of CTRL current, after the application of MIDO at t= 0 and after 5 and 20 minutes of incubation times.

| Incubation times (min) |

MIDO (%) at +60 mV (Vm) |

MIDO (%) at -60 mV (Vm) |

| 0 |

0 |

0 |

| 5 |

-84±8 |

-40±7 |

| 20 |

-100 |

-100 |

Table 6.

Changes in percentage (%) of membrane potential, after the application of REPA, MIDO and BaCl2+TEA at 4 different voltages: -80, -60, +60 and +80 mV.

Table 6.

Changes in percentage (%) of membrane potential, after the application of REPA, MIDO and BaCl2+TEA at 4 different voltages: -80, -60, +60 and +80 mV.

| Voltage membrane (mV) |

REPA (%) |

MIDO (%) |

BaCl2+TEA (%) |

| -80 |

-15.2±12 |

-11.69±8 |

-9.92±4 |

| -60 |

-3.89±1 |

-6.0±3 |

-2.4±1 |

| +60 |

-27.62±14 |

-35.72±9 |

-78.78±11 |

| +80 |

-13.78±21 |

-24.77±8 |

-99.4±1 |

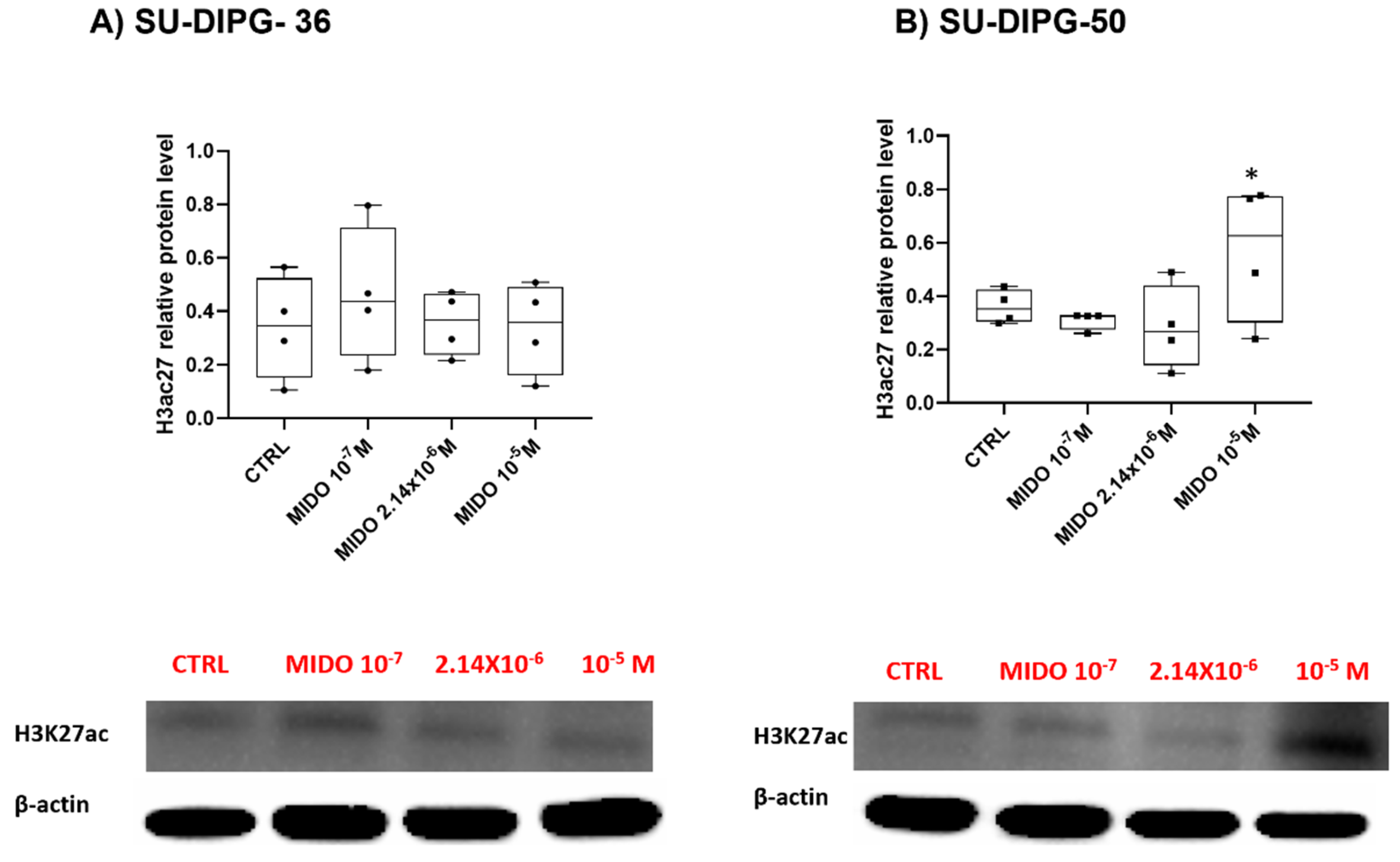

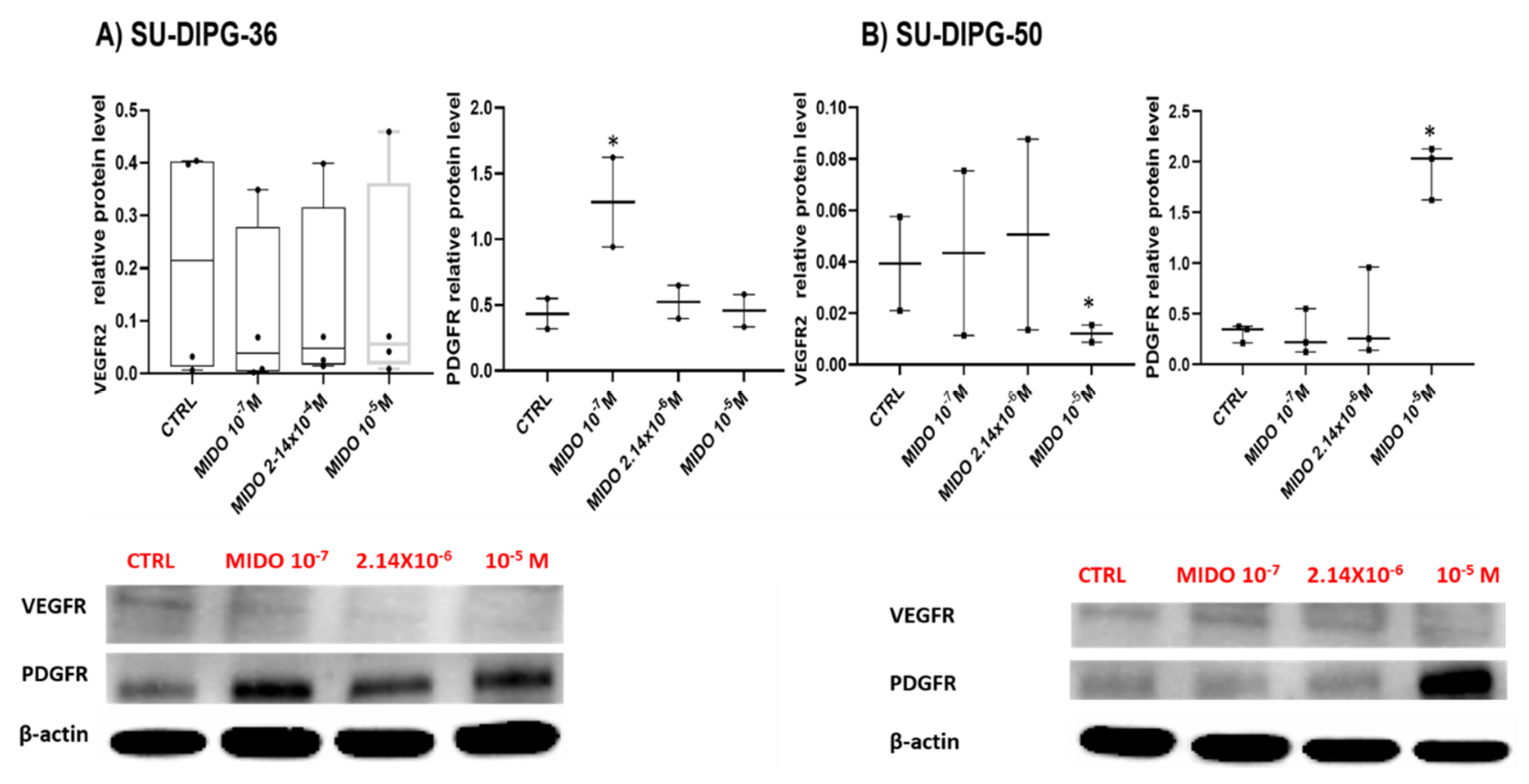

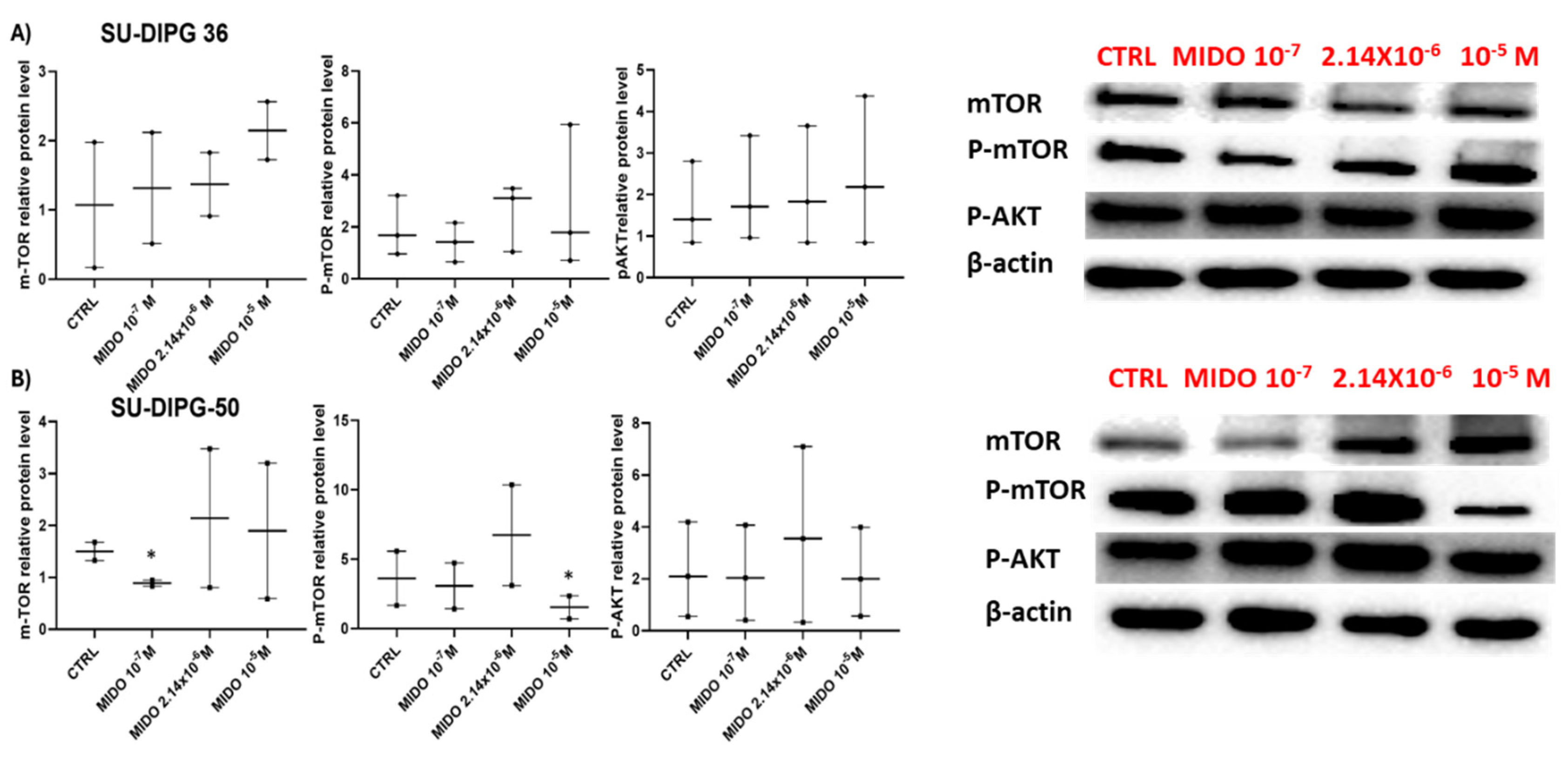

3.5. Effects of MIDO on Target Proteins After 48 h of Incubation Time in SU-DIPG Cells

Due to the observed efficacy of MIDO particularly in the SU-DIPG-36 cells after 48 h of incubation, we investigated some target proteins in both cell lines by western blot using β-actin as normalization standard. The H3K27ac protein content was firstly evaluated and are expected to be elevated following treatment with antiproliferative HDAC drugs in DIPG [

27].

MIDO did not affect H3K27ac protein content at all concentrations in SU-DIPG-36, and markedly increased it only at 10 μM concentration in SU-DIPG-50 (

Figure 8A, B). The disease is monoallelic with possible enhancement of the normal H3K27ac in our experiments following MIDO in SU-DIPG-50. The antibody used in western blot experiments (

Table 1A) does not distinguish between the two forms, so we believed that we observed the upregulation of the normal allele. In our previous work, the KATP channel inhibitor repaglinide concentration-dependently enhanced H3K27 acetylation in both SU-DIPG-cells with antiproliferative effects in the sub-nanomolar concentrations range using the same mAbs for western blot experiments [

16].

MIDO decreased the target receptor VEGFR2 level in the SU- DIPG-50 at high 10 μM concentration with no effects on SU- DIPG-36 (

Figure 9A, B). This drug paradoxically up-regulated PDGFR in both cells (

Figure 9A, B).

MIDO affected mTOR/AKT content but not significantly in SU-DIPG-36 cells (

Figure 10A). However, MIDO at a sub- micromolar concentration significantly downregulated m- TOR in the SU-DIPG-50 cells. At high concentration of 10 μM caused mTOR dephosphorylation in SU-DIPG-50 (

Figure 10B).

Phospho-ERK1-2 and ERK1-2 contents were not modified following 48 h of treatment of both cells with MIDO (data not shown).

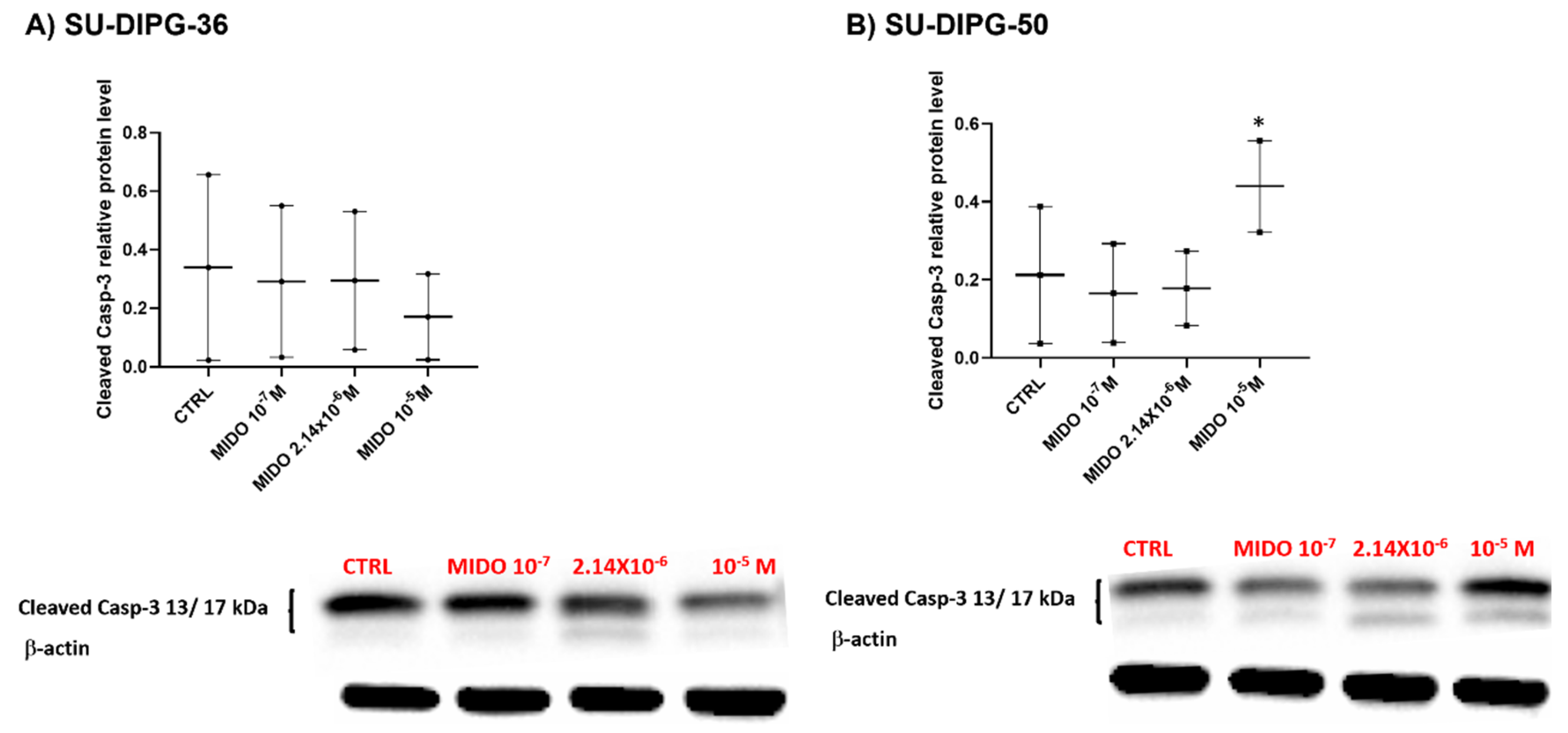

A concentration-dependent decrease of the apoptotic marker the cleaved caspase 3, following 48 h of treatment of SU- DIPG-36 was observed with MIDO (

Figure 11A). But SU-DIPG- 50 cells treated with 10 μM MIDO showed an enhanced content of this protein (

Figure 11B). This finding supports the idea that caspase 3 is not a target of MIDO action in SU-DIPG-36 cell but it can be in SU-DIPG-50 at high MIDO concentrations.

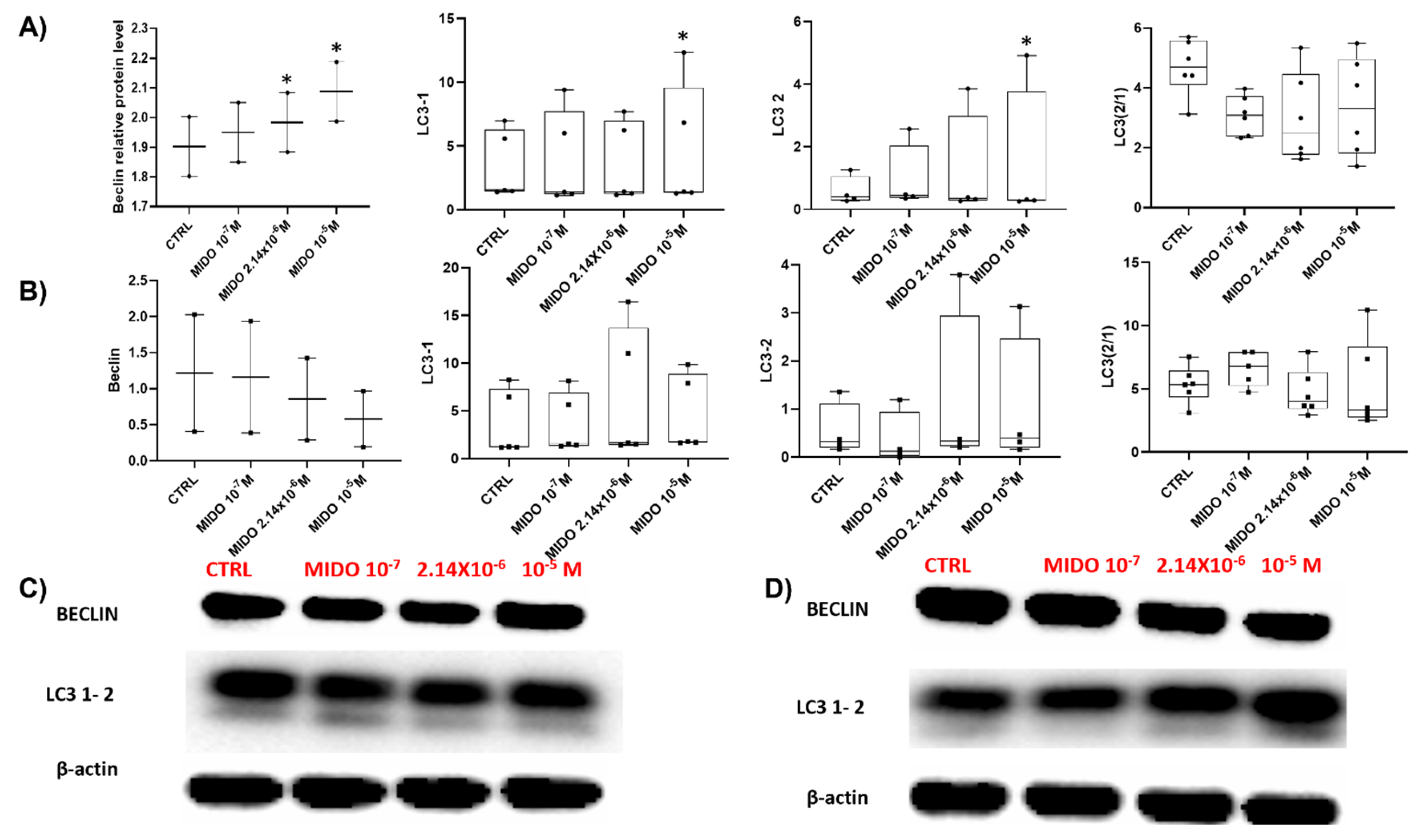

We also investigated some autophagic markers such as Beclin and LC3 1-2 and found a concentration -dependent increase of Beclin and LC3-1 and 2 content in the SU-DIPG-36 cells (

Figure 12A, C) while a concentration-dependent decrease of Beclin was observed in the SU-DIPG-50 cells (

Figure 12B, D). The LC3-2 and LC3-1 contents were not affected by MIDO in the SU-DIPG-50 and Beclin was down regulated supporting the idea of MIDO-induced autophagy in the SU-DIPG-36 cells.

4. Discussion

Tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) that are approved for different cancers are under investigation in brain tumors [

28,

29,

30]. However, there is to date no tyrosine kinase inhibitor approved for the brain tumor treatments such as glioblastoma or DIPG [

31,

32].

We firstly compared the effects of TKI targeting different kinases such as everolimus (mTOR), crizotinib (ALK/HFGR), dasatinib (ABL/PTKSrc/EAR2), erlotinib (EGFR), lapatinib (EGFR/RTKErbB2), perifosine (Pi3K-AKT1) and midostaurin (FLT3/PDGFR/VEGFR/PKC/c-Syk, c-Fgr/c-Kit and CDK1) in SU-DIPG-36 cells. In box plot analysis, everolimus, lapatinib, midostaurin, dasatinib, and perifosine were effective at low concentrations, at different incubation times and in either CCK-8 and CV assays and were investigated for their concentration-response relationships.

Concentration-response relationships analysis revealed that all drugs have IC50 values in the 10-5M concentrations range with the exception of midostaurin and dasatinib that showed IC50 values in the sub micromolar concentration ranges. Dasatinib showed however a bimodal concentration-response relationship reducing its efficacy at high concentrations. This can be due to signaling escaping the inhibitory effects of dasatinib.

Midostaurin was the most potent and effective drug and therefore investigated in SU-DIPG-50 cells. In box plot analysis, midostaurin confirmed its efficacy in SU-DIPG-50 cells at different incubation times and in either CV and CCK-8 assays. Concentration-response relationships investigations revealed that midostaurin have IC50 values in the sub micromolar concentrations ranges in all conditions and in the nanomolar concentrations after 72 h of incubation time in CCK-8 assay.

The actions of the drug were investigated on the ion channel currents by patch clamp and on the phosphorylation of target proteins by western blot. Considering that staurosporine, a structural analog and precursor of MIDO, is also known to reduce chloride and ATP-dependent potassium channels activity in other tissues [

33,

34], we tested the ability of MIDO to reduce ion channel current through patch clamp experiments. Patch-clamp investigations show that the acute application of 2.14 μM midostaurin, reduced the whole-cell inward and outward cation currents vs controls in the presence of low internal ATP. These currents were reduced by KATP channel inhibitors glibenclamide and repaglinide, and the unselective blockers TEA-BaCl

2. Midostaurin also reduced currents that are sensitive to TRPV1 channel blockers the capsazepine and ruthenium-red. In RT-PCR experiments, the expression of the

ABCC8 gene encoding for the SUR1 subunit, and

TRPV1 genes in DIPG-50 were higher than that observed in DIPG-36 suggesting that these subunits can mediate MIDO actions in the DIPG-50 cells [

16]. But the involvement of other ion channels cannot be excluded to date. Here, we further observed that Ba

2+ ions, the unselective inhibitor of Kir channels, and TEA, the unselective inhibitor of Kv and BK channels, also markedly reduce cell proliferation in DIPG cells. In SU-DIPG-50 the effects were also time dependent leading to a full reduction of the control current after 20 min of incubation time suggesting an additional mechanism based on the dephosphorylation of ion channel subunits. Several ion channels have tyrosine consensus site for phosphorylation that regulate channel openings. The fact that the calculated IC

50 of MIDO in either SU-DIPG cells were in the range of the IC

50 as antiproliferative drug support the action of MIDO as ion channel inhibitor.

In SU-DIPG-36 cells MIDO caused a concentration-dependent up- regulation of the autophagy markers and a decrease of the cleaved caspase 3 in the range of concentrations effective as antiproliferative suggesting of mayor contribution of the autophagic cell death in this cell. In these cells we also found the induction of PDGFR which has been recently associated with autophagic regulation in cancer [

35,

36,

37].

In SU-DIPG-50 cells, low concentrations of MIDO downregulates the VEGFR2. At high concentration of 10 μM MIDO caused also mTOR dephosphorylation, enhanced the acetyl histone H3 content and the cleaved caspase-3 with apoptosis and anti-proliferative effects. The combined inhibitory actions of ion channels and down- regulation of VEGFR2 and phospho-mTOR, and the activation of apoptotic pathway explain the higher potency of MIDO in SU-DIPG-50 vs the SU-DIPG-36 cells in the long term use.

Bibliographic analysis found no experimental data for lapatinib, perifosine, and dasatinib in DIPG, while experimental data for erlotinib, midostaurin and everolimus were reported with promising data [

8]. In our experimental setting on SU-DIPG-50 vs the SU-DIPG-36 cells, MIDO was more potent than everolimus and erlotinib with stable response all over 72 h of incubation time. MIDO shows a favorable safety factors with antiproliferative IC

50 values of about 10-

7 M and 10

-9M that are in the range of the reported Cmax of the free drug concentration of 3.5-35 × 10⁻⁹ M at steady-state calculated for 50 mg per os twice daily [

38]. Midostaurin is also considered a weak inhibitor of hERG with IC

50 values >10 mM (Rydapt

®) and low cardiovascular risk.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, TKI such as midostaurin are of interest in DIPG and can be combined for long term responses. The dephosphorylation of mTOR which is a well-known mechanism in the immune-response in transplant and in several cancers is also a key mechanism shared by midostaurin in SU-DIPG cells. Enzastaurin, a structural analog of midostaurin, is of some success in DIPG in animal models and in humans supporting the use of the staurosporine analogs in DIPG [

8]. The inhibition of cation channel currents by midostaurin observed in either SU-DIPG-36 and SU-DIPG-50 cells and the autophagy potentiation in SU-DIPG-36 variant can be additional mechanisms in DIPG. Inhibitors of KATP channels like glibenclamide and repaglinide were potent antiproliferative drugs in DIPG cells [

16]. Here, we further observed that Ba

2+ ions, the unselective inhibitor of Kir channels, and TEA, the unselective inhibitor of Kv and BK channels, also reduce cell proliferation in DIPG cells. The emerging role of ion channels in cancers and the developments of new data obtained in High-throughput screening (HTS) planar patch clamp, support the idea that cancer is a channelopathies [

39].

It should be of note that inhibition of different type of K

+ channels in hearth cells including the KATP channels can be responsible for arrhythmias, while inhibition of TRPV1 is associated with loss of analgesic response. Capsaicin patches are effective in neuropathic pain induced by chemotherapy but the effects of TRPV1 modulators in cancers are under investigation [

40].

A limitation of our work is that we do not a direct prove of the involvement of the TRPV1 and KATP channels in the MIDO responses and further study are needed to overcame this issue.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: Preprints.org, Table S1: Antibodies used in western blot experiments.

Author Contributions

Participated in research design: D. Tricarico. Performed experiments: M. Antonacci, A. Di Turi, M. Maqoud, M. Miciaccia, M. Denora. Performed data analysis: M. Antonacci, F. Maqoud, A. Di Turi. All authors contributed to write the manuscript.

Funding

The Italian Foundations: Fondazione GAIA (Marche), Heal Foundation (Lazio), Onlus Mia Neri Foundation (Lazio) and Matibellula Foundation (Piemonte) for their support in the form of studentship.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data is available on requests.

Acknowledgments

Thanks are due to Javad Nazarian (University of Zurich) for helpful scientific discussion. Also, thank the “XIX Premio Nazionale di Medicina “Santi Medici”, Sala Polifunzionale della Fondazione Santi Medici di Bitonto, Bari for support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| TKI |

Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors |

| MIDO |

Midostaurin |

| STS |

Staurosporine |

| DASA |

Dasatinib |

| EVE |

Everolimus |

| CRIZO |

Crizotinib |

| LAPA |

Lapatinib |

| ERLO |

Erlotinib |

| PERIF |

Perifosine |

| BaCl2

|

Barium Chloride |

| TEA |

Tetraethylammonium Hydrochloride |

| CAPSZ |

Capsazepine |

| RR |

Ruthenium Red |

| VEGFR2 |

Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Receptor 2 |

| mTOR |

Mammalian target of rapamycin |

| PDGFR |

Platelet-derived Growth Factor Receptor |

| LC3 |

Microtubule-associated protein 1A/1B-light chain |

| AKT |

Serine/threonine protein kinase |

| GLIB |

Glibenclamide |

| REPA |

Repaglinide |

| K-ATP |

ATP-sensitive potassium channels |

| TRP |

Transient Receptor Potential |

References

- Perrone, M.G.; Ruggiero, A.; Centonze, A.; Carrieri, A.; Ferorelli, S.; Scilimati, A. Diffuse Intrinsic Pontine Glioma (DIPG): Breakthrough and Clinical Perspective. Curr. Med. Chem. 2021, 28, 3287–3317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearson, A.D.; Mueller, S.; Filbin, M.G.; Grill, J.; Hawkins, C.; Jones, C.; Donoghue, M.; Drezner, N.; Weiner, S.; Russo, M.; et al. Paediatric strategy forum for medicinal product development in diffuse midline gliomas in children and adolescents ACCELERATE in collaboration with the European Medicines Agency with participation of the Food and Drug Administration. Eur. J. Cancer 2025, 217, 115230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louis, D.N.; Perry, A.; Reifenberger, G.; Von Deimling, A.; Figarella-Branger, D.; Cavenee, W.K.; Ohgaki, H.; Wiestler, O.D.; Kleihues, P.; Ellison, D.W. The 2016 World Health Organization Classification of Tumors of the Central Nervous System: A summary. Acta Neuropathol. 2016, 131, 803–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miciaccia, M.; Rizzo, F.; Centonze, A.; Cavallaro, G.; Contino, M.; Armenise, D.; Baldelli, O.M.; Solidoro, R.; Ferorelli, S.; Scarcia, P.; et al. Harmaline to Human Mitochondrial Caseinolytic Serine Protease Activation for Pediatric Diffuse Intrinsic Pontine Glioma Treatment. Pharmaceuticals 2024, 17, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shariff, N.; Moreno, A.S.; Bennett, J.; Ramaswamy, V.; Das, A.; Liu, A.P.; Huang, A.; Tabori, U.; Hawkins, C.; Dirks, P.; et al. Re-irradiation for children with diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma and diffuse midline glioma. Radiother. Oncol. 2025, 207, 110865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monje, M. The neuroscience of brain cancers. Neuron 2025, 113, 2734–2739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duchatel, R.J.; Jackson, E.R.; Alvaro, F.; Nixon, B.; Hondermarck, H.; Dun, M.D. Signal Transduction in Diffuse Intrinsic Pontine Glioma. Proteomics 2019, 19, e1800479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duchatel, R.J.; Jackson, E.R.; Parackal, S.G.; Kiltschewskij, D.; Findlay, I.J.; Mannan, A.; Staudt, D.E.; Thomas, B.C.; Germon, Z.P.; Laternser, S.; et al. PI3K/mTOR is a therapeutically targetable genetic dependency in diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma. J. Clin. Investig. 2024, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masselli, M.; Laise, P.; Tonini, G.; Fanelli, D.; Pillozzi, S.; Cetica, V.; Da Ros, M.; Sardi, I.; Buccoliero, A.M.; Aricò, M.; et al. Deregulation of Ion Channel and Transporter Encoding Genes in Pediatric Gliomas. Front. Oncol. 2012, 2, 17204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosendo-Pineda, M.J.; Moreno, C.M.; Vaca, L. Role of ion channels during cell division. Cell Calcium 2020, 91, 102258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arcangeli, A.; Yuan, J.X.-J. American Journal of Physiology-Cell Physiology theme: ion channels and transporters in cancer. Am. J. Physiol. Physiol. 2011, 301, C253–C254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arcangeli, A.; Crociani, O.; Lastraioli, E.; Masi, A.; Pillozzi, S.; Becchetti, A. Targeting Ion Channels in Cancer: A Novel Frontier in Antineoplastic Therapy. Curr. Med. Chem. 2009, 16, 66–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preußat, K.; Beetz, C.; Schrey, M.; Kraft, R.; Wölfl, S.; Kalff, R.; Patt, S. Expression of voltage-gated potassium channels Kv1.3 and Kv1.5 in human gliomas. Neurosci. Lett. 2003, 346, 33–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sontheimer, H. An Unexpected Role for Ion Channels in Brain Tumor Metastasis. Exp. Biol. Med. 2008, 233, 779–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuddapah, V.A.; Sontheimer, H. Ion channels and tranporters in cancer. 2. Ion channels and the control of cancer cell migration. Am. J. Physiol. Physiol. 2011, 301, C541–C549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonacci, M.; Maqoud, F.; Di Turi, A.; Miciaccia, M.; Perrone, M.G.; Scilimati, A.; Tricarico, D. KATP Channel Inhibitors Reduce Cell Proliferation Through Upregulation of H3K27ac in Diffuse Intrinsic Pontine Glioma: A Functional Expression Investigation. Cancers 2025, 17, 358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puljung, M.C. Cryo-electron microscopy structures and progress toward a dynamic understanding of KATP channels. J. Gen. Physiol. 2018, 150, 653–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, G.M.; Patton, B.L.; Shyng, S.-L. KATP channels in focus: Progress toward a structural understanding of ligand regulation. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2023, 79, 102541–102541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Aziz, Q.; Tinker, A. The Pharmacology of ATP-Sensitive K(+) Channels (K(ATP)). Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2021, 267, 357–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, K.; Liu, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Wang, Y.; Huang, L.; Chai, R.; Li, G.; Jiang, T. ABCC8 mRNA expression is an independent prognostic factor for glioma and can predict chemosensitivity. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 12682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Li, B.; Li, W.; Guo, H.; Zou, F. ATP-sensitive potassium channels control glioma cells proliferation by regulating ERK activity. Carcinog. 2009, 30, 737–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chinigò, G.; Castel, H.; Chever, O.; Gkika, D. TRP Channels in Brain Tumors. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 617801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabissi, M.; Morelli, M.B.; Arcella, A.; Cardinali, C.; Santoni, M.; Bernardini, G.; Santoni, A.; Santoni, G.; Amantini, C. Post-transcriptional regulation of 5'-untranslated regions of human Transient Receptor Potential Vanilloid type-1 (TRPV-1) channels: role in the survival of glioma patients. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 81541–81554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chubanov, V.; Grimm, C.; Hill, K.; Schaefer, M.; Köttgen, M.; Storch, U.; Schnitzler, M.M.Y.; Kudrina, V.; Erbacher, A.; Gudermann, T. Physiological functions and pharmacological targeting of transient receptor potential channels. Pharmacol. Rev. 2025, 77, 100089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baez, D.; Raddatz, N.; Ferreira, G.; Gonzalez, C.; Latorre, R. Gating of thermally activated channels. Curr Top Membr. 2014, 74, 51–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curci, A.; Maqoud, F.; Mele, A.; Cetrone, M.; Angelelli, M.; Zizzo, N.; et al. Antiproliferative effects of neuroprotective drugs targeting big Ca2+-activated K+ (BK) channel in the undifferentiated neuroblastoma cells. Curr Top Pharmacol 2016, 20, 113–131. Available online: https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-85019677647&partnerID=40&md5= 907df274e01877184ef686aaf48984cf.

- Noll, A.; Myers, C.; Biery, M.C.; Meechan, M.; Tahiri, S.; Rajendran, A.; Berens, M.E.; Paine, D.; Byron, S.; Zhang, J.; et al. Therapeutic HDAC inhibition in hypermutant diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma. Neoplasia 2023, 43, 100921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foroughi-Nia, B.; Barar, J.; Memar, M.Y.; Aghanejad, A.; Davaran, S. Progresses in polymeric nanoparticles for delivery of tyrosine kinase inhibitors. Life Sci. 2021, 278, 119642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Jiang, S.; Shi, Y. Tyrosine kinase inhibitors for solid tumors in the past 20 years (2001–2020). J. Hematol. Oncol. 2020, 13, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, G.; Ko, Y.T. Small molecule tyrosine kinase inhibitors in glioblastoma. Arch. Pharmacal Res. 2020, 43, 385–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jirousek, M.R.; Goekjian, P.G. Protein kinase C inhibitors as novel anticancer drugs. Expert Opin. Investig. Drugs 2001, 10, 2117–2140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Rocha, A.B.; Mans, D.; Regner, A.; Schwartsmann, G. Targeting Protein Kinase C: New Therapeutic Opportunities Against High-Grade Malignant Gliomas? Oncol. 2002, 7, 17–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricarico, D.; Camerino, D.C.; Govoni, S.; Bryant, S.H. Modulation of rat skeletal muscle chloride channels by activators and inhibitors of protein kinase C. Pflugers Arch. Eur. J. Physiol. 1991, 418, 500–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mele, A.; Camerino, G.M.; Calzolaro, S.; Cannone, M.; Conte, D.; Tricarico, D. Dual response of the KATP channels to staurosporine: A novel role of SUR2B, SUR1 and Kir6.2 subunits in the regulation of the atrophy in different skeletal muscle phenotypes. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2014, 91, 266–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaaf, M.B.; Houbaert, D.; Meçe, O.; To, S.K.; Ganne, M.; Maes, H.; Agostinis, P. Lysosomal Pathways and Autophagy Distinctively Control Endothelial Cell Behavior to Affect Tumor Vasculature. Front. Oncol. 2019, 9, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lv, D.; Yang, K.; Rich, J.N. Growth factor receptor signaling induces mitophagy through epitranscriptomic regulation. Autophagy 2023, 19, 1034–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paugh, B.S.; Qu, C.; Jones, C.; Liu, Z.; Adamowicz-Brice, M.; Zhang, J.; Bax, D.A.; Coyle, B.; Barrow, J.; Hargrave, D.; et al. Integrated Molecular Genetic Profiling of Pediatric High-Grade Gliomas Reveals Key Differences With the Adult Disease. J. Clin. Oncol. 2010, 28, 3061–3068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooreman, K.; De Spiegeleer, B.; Van Poucke, C.; Vanavermaete, D.; Delbare, D.; Wynendaele, E.; De Witte, B. Emerging pharmaceutical therapies of Ascidian-derived natural products and derivatives. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2023, 102, 104254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, D.C.; Leanza, L.; Gentile, S.; Sauter, D.R. News and views on ion channels in cancer: is cancer a channelopathy? Front. Pharmacol. 2023, 14, 1258933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szallasi, A. Targeting TRPV1 for Cancer Pain Relief: Can It Work? Cancers 2024, 16, 648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Box-plot analysis of cell survival normalized percentage (%) changes with TKI in SU-DIPG-36 cells after 48h and 72h of incubation times in 96 multi-wells crystal violet (CV) and CCK-8 assays. Dasatinib (DASA) (5 nM and 100 µM), everolimus (EVE) (5 µm and 100 µM), crizotinib (CRIZO) (0.5 µM and 100µM), lapatinib (LAPA) (5 µM and 100 µM), erlotinib (ERLO) (0.1 µM and 100 µM), perifosine (PERIF) (1.5 µM and 100 µM), BaCl2 (1 mM and 5 mM), TEA (500 µM and 5 mM) and midostaurin (MIDO)(0.1µM and 50µM). One-way ANOVA test showed data significantly different within and between groups with F values>2(*). At least three samples per condition were selected for data representation.

Figure 1.

Box-plot analysis of cell survival normalized percentage (%) changes with TKI in SU-DIPG-36 cells after 48h and 72h of incubation times in 96 multi-wells crystal violet (CV) and CCK-8 assays. Dasatinib (DASA) (5 nM and 100 µM), everolimus (EVE) (5 µm and 100 µM), crizotinib (CRIZO) (0.5 µM and 100µM), lapatinib (LAPA) (5 µM and 100 µM), erlotinib (ERLO) (0.1 µM and 100 µM), perifosine (PERIF) (1.5 µM and 100 µM), BaCl2 (1 mM and 5 mM), TEA (500 µM and 5 mM) and midostaurin (MIDO)(0.1µM and 50µM). One-way ANOVA test showed data significantly different within and between groups with F values>2(*). At least three samples per condition were selected for data representation.

Figure 2.

Clone formation with everolimus 100 µM (EVE) and perifosine 100 µM (PERIF) and 2.15 μM midostaurin (MIDO) on SU-DIPG-36 using the clonogenic assay after 72h of incubation. It should of note in this assay that the drug solution is washed out following treatment. Student t test for p<0.05* was used to test for significance between the two groups. At least three samples per condition were selected for data representation.

Figure 2.

Clone formation with everolimus 100 µM (EVE) and perifosine 100 µM (PERIF) and 2.15 μM midostaurin (MIDO) on SU-DIPG-36 using the clonogenic assay after 72h of incubation. It should of note in this assay that the drug solution is washed out following treatment. Student t test for p<0.05* was used to test for significance between the two groups. At least three samples per condition were selected for data representation.

Figure 3.

Clone formation with dasatinib (DASA) 100 nM and 100 µM, and lapatinib 100 µM (LAPA) on SU-DIPG-36 using the clonogenic assay after 72h of incubation. It should of note in this assay the drug solution is washed out following treatment. Student t test for p<0.05* was used to test for significance between the two groups. At least three samples per condition were selected for data representation.

Figure 3.

Clone formation with dasatinib (DASA) 100 nM and 100 µM, and lapatinib 100 µM (LAPA) on SU-DIPG-36 using the clonogenic assay after 72h of incubation. It should of note in this assay the drug solution is washed out following treatment. Student t test for p<0.05* was used to test for significance between the two groups. At least three samples per condition were selected for data representation.

Figure 4.

Everolimus (EVE), lapatinib (LAPA), perifosine (PERIF), dasatinib (DASA) and midostaurin (MIDO) (0.001-100 μM) concentration-dependent inhibition of cell proliferation, expressed as normalized percentage (%), on SU-DIPG-36 cells in multi-wells crystal violet (CV) and CCK-8 assays after 48 h and 72 h of incubation times.

Figure 4.

Everolimus (EVE), lapatinib (LAPA), perifosine (PERIF), dasatinib (DASA) and midostaurin (MIDO) (0.001-100 μM) concentration-dependent inhibition of cell proliferation, expressed as normalized percentage (%), on SU-DIPG-36 cells in multi-wells crystal violet (CV) and CCK-8 assays after 48 h and 72 h of incubation times.

Figure 5.

Midostaurin (MIDO) (0.001-100 μM) concentration-dependent inhibition of cell proliferation, expressed as normalized percentage (%), on SU-DIPG-50 cells in multi-wells crystal violet (CV) and CCK-8 assays after 48 h and 72 h of incubation times.

Figure 5.

Midostaurin (MIDO) (0.001-100 μM) concentration-dependent inhibition of cell proliferation, expressed as normalized percentage (%), on SU-DIPG-50 cells in multi-wells crystal violet (CV) and CCK-8 assays after 48 h and 72 h of incubation times.

Figure 6.

I/V relationships and effects of midostaurin (MIDO) on the macroscopic K+ currents recorded in SU-DIPG-36 cells during voltage step application to the cells. (A) Sample traces of CTRL current, after the application of CAPSZ, MIDO and RR. The application of 1 μM CAPSZ, 2.14 μM MIDO, and 10 μM RR reduced control currents with 10 μM RR being the most effective compound. (B) Sample traces of CTRL current, after the application of GLIB, MIDO and RR. The application of GLIB 100 μM, 2.14 μM MIDO and 5 mM BaCl2 + 10 mM TEA reduced control currents with 5 mM BaCl2 + 10 mM TEA being the most effective drugs. A washout period of 5 sec follows the application of drug solutions.

Figure 6.

I/V relationships and effects of midostaurin (MIDO) on the macroscopic K+ currents recorded in SU-DIPG-36 cells during voltage step application to the cells. (A) Sample traces of CTRL current, after the application of CAPSZ, MIDO and RR. The application of 1 μM CAPSZ, 2.14 μM MIDO, and 10 μM RR reduced control currents with 10 μM RR being the most effective compound. (B) Sample traces of CTRL current, after the application of GLIB, MIDO and RR. The application of GLIB 100 μM, 2.14 μM MIDO and 5 mM BaCl2 + 10 mM TEA reduced control currents with 5 mM BaCl2 + 10 mM TEA being the most effective drugs. A washout period of 5 sec follows the application of drug solutions.

Figure 7.

I/V relationships and effects of midostaurin (MIDO) on the macroscopic K+ currents recorded in SU-DIPG-50 cells during voltage step application to the cells. (A) Sample traces of CTRL current, after the application of MIDO at t= 0 and after 5 and 20 minutes of incubation times. The application of 2.14 μM MIDO at different incubation time reduced time dependently the currents. (B) I/V relationships of cells with resting potentials close to the equilibrium potentials for K+ ions (upper panel) and (lower panel) of cells markedly depolarized sensitive to 100 μM REPA, a KATP channel inhibitor, and 2.14 μM MIDO. (C) Concentration-response relationships of MIDO concentrations vs ion channel currents at -60 mV(Vm) in SU-DIPG 36 and SU-DIPG-50 cells.

Figure 7.

I/V relationships and effects of midostaurin (MIDO) on the macroscopic K+ currents recorded in SU-DIPG-50 cells during voltage step application to the cells. (A) Sample traces of CTRL current, after the application of MIDO at t= 0 and after 5 and 20 minutes of incubation times. The application of 2.14 μM MIDO at different incubation time reduced time dependently the currents. (B) I/V relationships of cells with resting potentials close to the equilibrium potentials for K+ ions (upper panel) and (lower panel) of cells markedly depolarized sensitive to 100 μM REPA, a KATP channel inhibitor, and 2.14 μM MIDO. (C) Concentration-response relationships of MIDO concentrations vs ion channel currents at -60 mV(Vm) in SU-DIPG 36 and SU-DIPG-50 cells.

Figure 8.

Acetyl histone H3 protein expression in SU- DIPG-36 and SU-DIPG-50 cells after treatment with increasing concentrations of MIDO after 48 h of treatment. A) Box-plot representations of Acetyl-Histone H3 (Lys27) content in SU-DIPG-36 cells. Western blotting images showing acetyl histone H3 content, below gel panel. B) Box-plot representations of Acetyl-Histone H3 (Lys27) content in SU-DIPG-50 cells. Western blotting images showing acetyl histone H3 content, below gel panel. β-actin was used as a housekeeping protein. The actin panels were obtained from the same gels and captured under the same exposure conditions as the target proteins. All data were normalized to β- actin. Data significantly different by ANOVA * p < 0.05 vs the control group (CTRL). Box-plot data are the mean±SEM of three independent experiments.

Figure 8.

Acetyl histone H3 protein expression in SU- DIPG-36 and SU-DIPG-50 cells after treatment with increasing concentrations of MIDO after 48 h of treatment. A) Box-plot representations of Acetyl-Histone H3 (Lys27) content in SU-DIPG-36 cells. Western blotting images showing acetyl histone H3 content, below gel panel. B) Box-plot representations of Acetyl-Histone H3 (Lys27) content in SU-DIPG-50 cells. Western blotting images showing acetyl histone H3 content, below gel panel. β-actin was used as a housekeeping protein. The actin panels were obtained from the same gels and captured under the same exposure conditions as the target proteins. All data were normalized to β- actin. Data significantly different by ANOVA * p < 0.05 vs the control group (CTRL). Box-plot data are the mean±SEM of three independent experiments.

Figure 9.

Expression of VEGFR2 and PDGFR in SU- DIPG-36 and SU-DIPG-50 cells after treatment with increasing concentrations of MIDO after 48 h of incubation time. A) Box-plot representations of VEGFR2 and PDGFR content in SU-DIPG-36 cells. Western blotting images showing VEGFR2 and PDGFR protein expression, below gel panel. B) Box-plot representations of VEGFR2 and PDGFR content in SU-DIPG-50 cells. Western blotting images showing VEGFR2 and PDGFR protein content, below panel. β-actin was used as a housekeeping protein. The actin panels were obtained from the same gels and captured under the same exposure conditions as the target proteins. All data were normalized to β- actin. Data significantly different by ANOVA * p < 0.05 vs the control group (CTRL). Box-plot data are the mean ± SEM of three independent experiments.

Figure 9.

Expression of VEGFR2 and PDGFR in SU- DIPG-36 and SU-DIPG-50 cells after treatment with increasing concentrations of MIDO after 48 h of incubation time. A) Box-plot representations of VEGFR2 and PDGFR content in SU-DIPG-36 cells. Western blotting images showing VEGFR2 and PDGFR protein expression, below gel panel. B) Box-plot representations of VEGFR2 and PDGFR content in SU-DIPG-50 cells. Western blotting images showing VEGFR2 and PDGFR protein content, below panel. β-actin was used as a housekeeping protein. The actin panels were obtained from the same gels and captured under the same exposure conditions as the target proteins. All data were normalized to β- actin. Data significantly different by ANOVA * p < 0.05 vs the control group (CTRL). Box-plot data are the mean ± SEM of three independent experiments.

Figure 10.

Expression of mTOR and AKT in SU-DIPG-36 and SU-DIPG-50 cells after treatment with different concentrations of MIDO after 48 h of incubation time. A) Box-plot representations of mTOR, phospho-mTOR and phospho-AKT contents and sample western blotting images showing mTOR, phospho-TOR, and phospho-AKT protein content. β- actin was used as a housekeeping protein. B) Box-plot representations of mTOR, phospho-mTOR and phospho-AKT in SU-DIPG-50 and sample western blotting images showing these protein contents. β-actin was used as a housekeeping protein. The actin panels were obtained from the same gels and captured under the same exposure conditions as the target proteins. All data were normalized to β- actin. Data significantly different by ANOVA * p < 0.05 vs the control group (CTRL). Box-plot data are the mean ± SEM of three independent experiments.

Figure 10.

Expression of mTOR and AKT in SU-DIPG-36 and SU-DIPG-50 cells after treatment with different concentrations of MIDO after 48 h of incubation time. A) Box-plot representations of mTOR, phospho-mTOR and phospho-AKT contents and sample western blotting images showing mTOR, phospho-TOR, and phospho-AKT protein content. β- actin was used as a housekeeping protein. B) Box-plot representations of mTOR, phospho-mTOR and phospho-AKT in SU-DIPG-50 and sample western blotting images showing these protein contents. β-actin was used as a housekeeping protein. The actin panels were obtained from the same gels and captured under the same exposure conditions as the target proteins. All data were normalized to β- actin. Data significantly different by ANOVA * p < 0.05 vs the control group (CTRL). Box-plot data are the mean ± SEM of three independent experiments.

Figure 11.

Expression of cleaved caspase-3 in SU-DIPG- 36 and SU-DIPG-50 cells after treatment with increasing concentrations of MIDO after 48 h of incubation time. A) Box-plot representations of cleaved caspase-3 content in -SU-DIPG-36 cells. Western blotting images showing cleaved caspase-3 protein content, below gel panel. B) Box-plot representations of cleaved caspase-3 content in SU-DIPG-50. Western blotting images showing cleaved caspase-3 protein content, below gel panel. β- actin was used as a housekeeping protein. The actin panels were obtained from the same gels and captured under the same exposure conditions as the target proteins. All data were normalized to β- actin. Data significantly different by ANOVA * p < 0.05 vs the control group (CTRL). Box-plot data are the mean ± SEM of three independent experiments.

Figure 11.

Expression of cleaved caspase-3 in SU-DIPG- 36 and SU-DIPG-50 cells after treatment with increasing concentrations of MIDO after 48 h of incubation time. A) Box-plot representations of cleaved caspase-3 content in -SU-DIPG-36 cells. Western blotting images showing cleaved caspase-3 protein content, below gel panel. B) Box-plot representations of cleaved caspase-3 content in SU-DIPG-50. Western blotting images showing cleaved caspase-3 protein content, below gel panel. β- actin was used as a housekeeping protein. The actin panels were obtained from the same gels and captured under the same exposure conditions as the target proteins. All data were normalized to β- actin. Data significantly different by ANOVA * p < 0.05 vs the control group (CTRL). Box-plot data are the mean ± SEM of three independent experiments.

Figure 12.

Expression of Beclin and LC3 1-2 in SU-DIPG- 36 and SU-DIPG-50 cells after treatment with increasing concentrations of MIDO after 48 h of incubation time. A) Box-plot representations of Beclin and LC3 1-2 content in SU-DIPG-36 cells. B) Box-plot representations of Beclin and LC3 1-2 content after 48 h of treatment in SU-DIPG-50 cells. C) Western blotting images showing Beclin and LC3 1-2 protein content in SU-DIPG-36 cells. D) Western blotting images showing Beclin and LC3 1-2 protein content in SU-DIPG-50. β-actin was used as a housekeeping protein. The actin panels were obtained from the same gels and captured under the same exposure conditions as the target proteins. All data were normalized to β- actin. Data significantly different by ANOVA * p <0.05 vs the control group (CTRL). Box-plot data are the mean ± SEM of three independent experiments.

Figure 12.

Expression of Beclin and LC3 1-2 in SU-DIPG- 36 and SU-DIPG-50 cells after treatment with increasing concentrations of MIDO after 48 h of incubation time. A) Box-plot representations of Beclin and LC3 1-2 content in SU-DIPG-36 cells. B) Box-plot representations of Beclin and LC3 1-2 content after 48 h of treatment in SU-DIPG-50 cells. C) Western blotting images showing Beclin and LC3 1-2 protein content in SU-DIPG-36 cells. D) Western blotting images showing Beclin and LC3 1-2 protein content in SU-DIPG-50. β-actin was used as a housekeeping protein. The actin panels were obtained from the same gels and captured under the same exposure conditions as the target proteins. All data were normalized to β- actin. Data significantly different by ANOVA * p <0.05 vs the control group (CTRL). Box-plot data are the mean ± SEM of three independent experiments.

Table 1.

Surviving fraction (%) and N of formed colonies after 72h of incubation for SU-DIPG-36 treated with everolimus 100 µM, perifosine 100 µM and midostaurin 2.14 µM.

Table 1.

Surviving fraction (%) and N of formed colonies after 72h of incubation for SU-DIPG-36 treated with everolimus 100 µM, perifosine 100 µM and midostaurin 2.14 µM.

| Experimental condition |

Surviving fraction (%) after 72h of incubation |

N of formed colonies after 72h of incubation |

| CTRL |

100 |

186.3 |

| EVEROLIMUS 100 µM |

0.06 ± 0.0006 |

0.1 |

| PERIFOSINE 100 µM |

86.2 ± 0.08 |

160.6 |

| MIDOSTAURIN 2.14 µM |

0 ± 0 |

0 |

Table 2.

Surviving fraction (%) and N of formed colonies after 72h of incubation for SU-DIPG-36 treated with dasatinib 100 nM, dasatinib 100 µM and lapatinib 100 µM.

Table 2.

Surviving fraction (%) and N of formed colonies after 72h of incubation for SU-DIPG-36 treated with dasatinib 100 nM, dasatinib 100 µM and lapatinib 100 µM.

| Experimental condition |

Surviving fraction (%) after 72h of incubation |

N of formed colonies after 72h |

| CTRL |

100 |

89.2 |

| DASATINIB 100 nM |

45.7 ± 0.05 |

40.8 |

| DASATINIB 100 µM |

0.6 ± 0.003 |

0.5 |

| LAPATINIB 100 µM |

2.05 ± 0.003 |

1.8 |

Table 3.

Fitting parameters of Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors (TKI) concentration-response relationships in SU-DIPG-36 cells in 96 multi-wells Crystal violet (CV) and CCK-8 assays after 48 h and 72 h incubation times.

Table 3.

Fitting parameters of Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors (TKI) concentration-response relationships in SU-DIPG-36 cells in 96 multi-wells Crystal violet (CV) and CCK-8 assays after 48 h and 72 h incubation times.

| SU-DIPG-36 cells |

EVEROLIMUS

IC50(M) HillSlope Emax(%) |

LAPATINIB

IC50(M)

HillSlope

Emax(%) |

PERIFOSINA

IC50(M)

HillSlope

Emax(%) |

DASATINIB

IC50(M)

HillSlope

Emax(%) |

MIDOSTAURIN

IC50(M)

HillSlope

Emax(%) |

CV

48 h

|

3.607 x 10-5

-1.870

-100% |

1.587 x 10-5

-1.426

-53.61% |

2.829 x 10-5

-1.937

-99.88% |

1.912 x 10-7

-0.2534

-81.81% |

2.170 x 10-7

-1.762

-100% |

CCK-8

48 h

|

4.361 x 10-5

-4.869

-91.80% |

5.210 x 10-5

-5.676

-92.77% |

5.159 x 10-5

-3.475

-65.47% |

1.057 x 10-5

-5.059

-100% |

9.486 x 10-7

-2.064

-100% |

CV

72 h

|

2.954 x 10-5

-2.805

-100% |

2.995 x 10-5

-29.17

-100% |

3.154 x 10-5

-3.246

-100% |

1.095 x 10-5

-10.44

-100% |

3.356 x 10-7

-1.311

-100% |

CCK-8

72 h

|

4.435 x 10-5

-6.532

-100% |

4.447 x 10-5

-6.161

-100% |

5.615 x 10-5

-19.10

-100% |

1.478 x 10-8

-0.294

-100% |

14.739 x 10-7

-2.189

-100% |

Table 4.

Fitting parameters of midostaurin (MIDO) concentration-response in SU-DIPG-50 cells after 48 h and 72 h incubation times in 96 multi-wells crystal violet (CV) and CCK-8 assays.

Table 4.

Fitting parameters of midostaurin (MIDO) concentration-response in SU-DIPG-50 cells after 48 h and 72 h incubation times in 96 multi-wells crystal violet (CV) and CCK-8 assays.

SU-

DIPG-50 cells |

MIDO CV |

MIDO CCK-8

|

| IC50(M) |

HillSlope |

Emax(%) |

IC50(M) |

HillSlope |

Emax(%) |

| 48h |

8.6x10-7 |

-6.9 |

-100% |

1.2x10-7 |

-7.9 |

-100% |

| 72h |

1.3x10-7 |

-8.3 |

-100% |

1.4x10-9 |

-11.8 |

-100% |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).