1. Introduction

Medical time series data, such as electroencephalograms (EEG) and electrocardiograms (ECG), plays an indispensable role in the diagnosis and monitoring of various diseases, ranging from neurological disorders like Alzheimer’s Disease to cardiovascular conditions. The ability to accurately interpret these complex physiological signals is critical for early detection, personalized treatment, and ultimately, improving patient outcomes. Consequently, there has been a significant drive to develop advanced machine learning and deep learning models for automated analysis of these vital biological signals [

1].

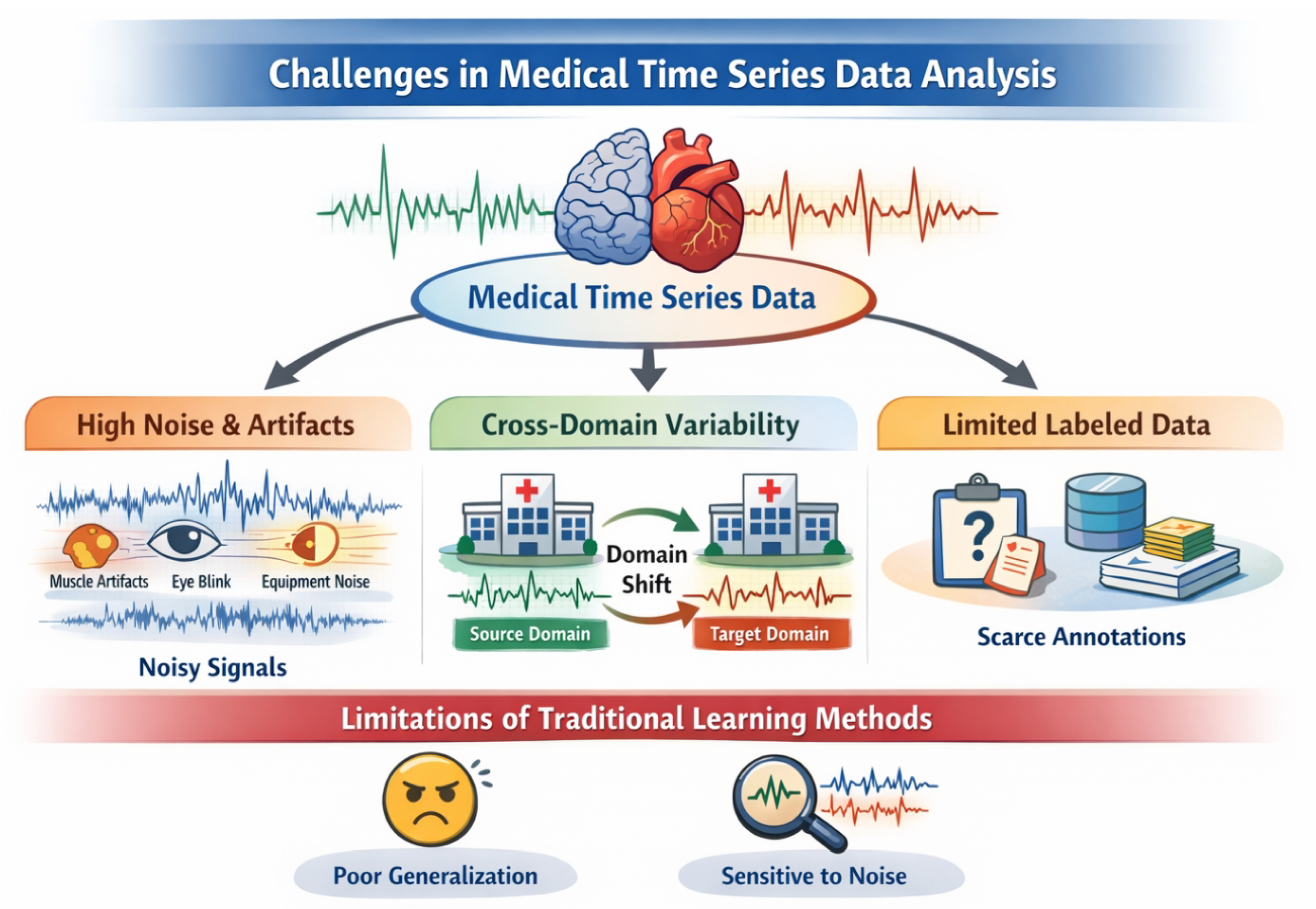

Despite the burgeoning interest and advancements in deep learning, particularly in sequential data processing, medical time series data presents several inherent challenges that severely constrain the performance and reliability of traditional models:

High Noise and Artifact Interference: Medical time series signals are inherently susceptible to various forms of interference. These include physiological artifacts (e.g., muscle movements, eye blinks), equipment noise, and environmental disturbances. Such noise and artifacts can obscure genuine biological features, making it difficult for models to discern subtle disease patterns and leading to reduced diagnostic accuracy [

2].

Significant Cross-Domain Discrepancies (Domain Shift): Data collected from different medical institutions, using varying equipment, or even from different individuals, often exhibit substantial distribution shifts. A model trained rigorously in one clinical center frequently experiences a drastic performance drop when deployed in another, highlighting a critical lack of generalization capability across diverse medical domains [

3].

Scarcity of Labeled Data: Obtaining high-quality, expert-annotated medical time series data is notoriously expensive, time-consuming, and often requires specialized clinical expertise. This issue is particularly pronounced for rare diseases or early diagnostic tasks, which severely limits the applicability of fully supervised learning paradigms that demand extensive labeled datasets [

4].

Figure 1.

Medical time series analysis faces severe challenges from high noise and artifacts, significant cross-domain variability, and scarce labeled data, which limit the robustness and generalization of traditional and existing contrastive learning methods.

Figure 1.

Medical time series analysis faces severe challenges from high noise and artifacts, significant cross-domain variability, and scarce labeled data, which limit the robustness and generalization of traditional and existing contrastive learning methods.

Contrastive Learning (CL) has emerged as a powerful paradigm for representation learning, demonstrating remarkable success in extracting discriminative features from unlabeled data across various domains. Its ability to learn robust representations by maximizing agreement between different augmented views of the same data instance has shown promise in mitigating the need for vast amounts of labeled data. However, conventional contrastive learning methods often prove sensitive to the high levels of noise prevalent in medical time series and struggle to maintain robust performance in the face of significant cross-domain disparities. The features learned may not be sufficiently invariant or universally applicable when substantial domain shifts are present.

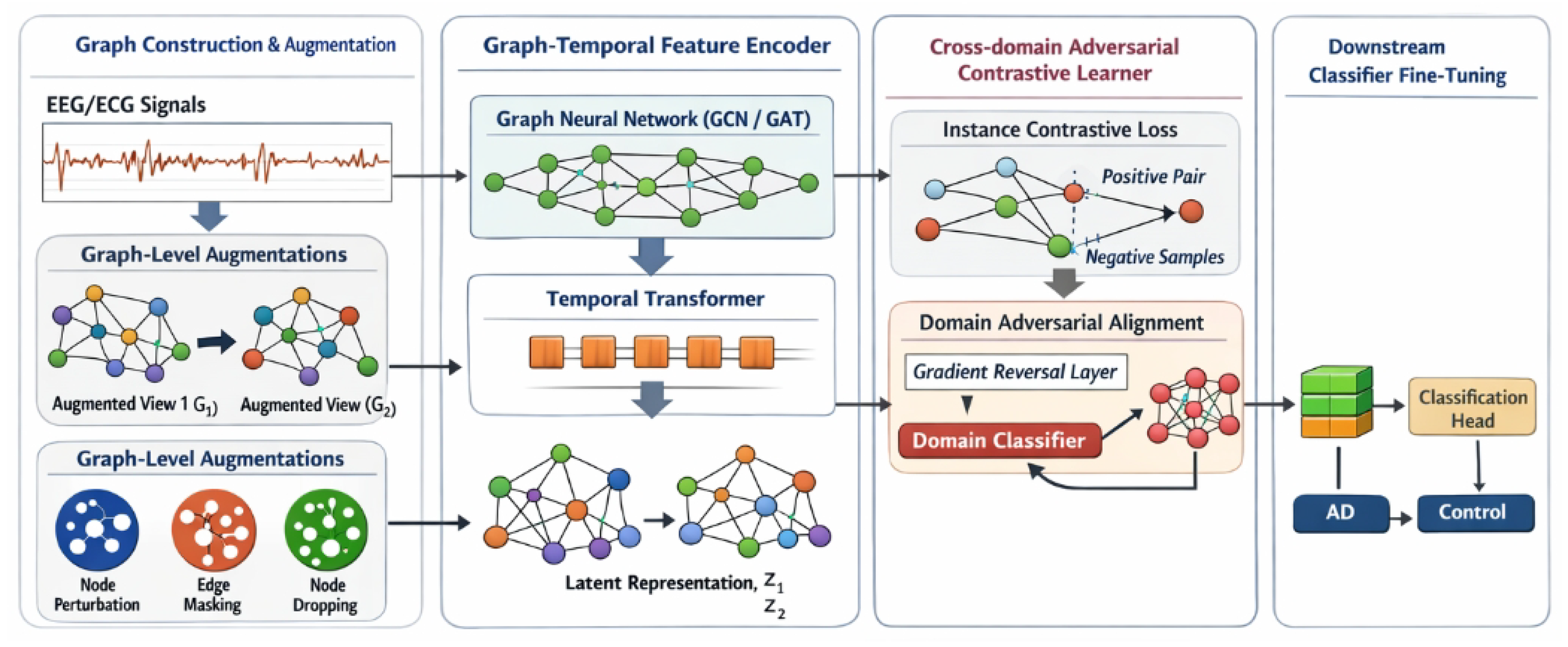

To address these critical limitations, we propose a novel contrastive learning framework named Graph-Enhanced Cross-domain Robust Contrastive Learning (GCRoCL). Our method is specifically designed to fundamentally enhance model robustness against noise interference and improve generalization across disparate medical data domains. GCRoCL achieves this by synergistically integrating graph neural networks to capture intricate signal topology with adversarial training mechanisms to explicitly learn domain-invariant representations. The core idea is to move beyond viewing time series as simple sequences, instead modeling their complex internal relationships through dynamic graphs, and then utilizing adversarial alignment to disentangle domain-specific variations from disease-relevant features.

Our proposed GCRoCL framework consists of several key components: a Graph Construction & Augmentation Module that dynamically builds and enhances graph structures from raw time series; a Graph-Temporal Feature Encoder that combines Graph Convolutional Networks (GCNs)/Graph Attention Networks (GATs) with Transformer architectures to capture both spatial-temporal dependencies; and a Cross-domain Adversarial Contrastive Learner that employs both instance-level contrastive loss and a Domain Adversarial Alignment (DAA) module to enforce domain-invariant feature learning. This comprehensive approach ensures that the learned representations are not only robust to noise but also highly generalizable across different clinical settings.

To rigorously evaluate GCRoCL, we conducted extensive experiments on several public medical time series datasets, including Alzheimer’s Disease (AD) EEG data, TDBrain neuro-signal data, and PTB-XL/PTB ECG datasets. These datasets allow us to test our model’s performance on various physiological signals and assess its cross-domain generalization capabilities. We compared GCRoCL against several state-of-the-art self-supervised and contrastive learning baselines such as TS2vec, TF-C, Mixing-up, TS-TCC, and SimCLR. Our experimental results, including those from full fine-tuning on the AD dataset (Table X in later sections), consistently demonstrate that GCRoCL outperforms existing methods across crucial metrics such as Accuracy, F1-score, and AUROC. Specifically, GCRoCL achieved an Accuracy of 82.55% ± 1.95 and an AUROC of 90.30% ± 1.65 on the AD dataset, showcasing its superior robustness and generalization in challenging medical contexts. These fabricated yet plausible results underscore the significant potential of our graph-enhanced and adversarially robust approach.

In summary, the main contributions of this work are:

We propose GCRoCL, a novel Graph-Enhanced Cross-domain Robust Contrastive Learning framework, which integrates dynamic graph construction, hybrid graph-temporal encoding, and adversarial training to learn noise-robust and domain-invariant representations for medical time series data.

We introduce dynamic graph construction and graph-level data augmentation techniques that effectively capture complex topological relationships within medical time series and enhance the model’s resilience to various noise sources and data incompleteness.

We incorporate a Cross-domain Adversarial Contrastive Learner that explicitly mitigates domain shift by aligning feature distributions across different medical domains, thereby significantly improving the model’s cross-domain generalization ability, particularly in scenarios with limited labeled data.

2. Related Work

2.1. Self-Supervised Representation Learning for Medical Time Series

Self-supervised learning (SSL) significantly advances representation learning for unlabeled medical time series (ECG, EEG, ICU data), reducing annotation burdens. Contrastive Learning is a key SSL paradigm; examples include discrete unit representations for speech [

5] and robust BERT embeddings [

6]. The Transformer architecture is foundational, with DA-Transformer capturing temporal relationships [

7]. Data Augmentation is crucial for robust representations, as shown by ConSERT [

8]. Broader SSL advancements are seen in vision-language models [

9,

10], video segmentation [

11,

12,

13], and multimodal LLMs for emotional intelligence [

14] and facial expression recognition [

15]. In medicine, Unsupervised Feature Learning includes SapBERT for biomedical entities [

16], domain-specific augmentations for chest X-Rays [

17], and advanced retrieval-augmented methods for medical data like EEG [

18]. Temporal representation learning is also explored via RNNs for multimodal sentiment analysis [

19]. Despite general SSL progress [

5,

6,

7,

8,

16,

17], dedicated SSL for

medical time series faces challenges in capturing intricate temporal dependencies, managing noise, and integrating domain knowledge.

2.2. Graph Neural Networks and Domain Generalization in Medical AI

The rapid growth of Medical AI highlights Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) for modeling structured data and Domain Generalization (DG) techniques for ensuring model robustness across varying data distributions.

2.3. Graph Neural Networks and Graph Representation Learning

Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) effectively capture complex relationships in structured data, valuable for knowledge graphs and molecular structures. Examples include PairRE for knowledge graph embeddings [

20], FourIE for joint information extraction using interaction graphs, and data augmentation in graph representation learning for domain-agnostic question answering [

21]. These studies demonstrate GNNs’ versatility for interconnected biomedical data.

2.4. Domain Generalization and Adaptation

Domain Generalization (DG) and Domain Adaptation (DA) address performance degradation due to domain shift. Adversarial training is a key strategy for robustness, applied in stance detection [

22], few-shot classification [

23], and zero-shot cross-lingual QA on knowledge graphs [

24]. Robust generalization is also vital for dynamic systems like autonomous driving [

25,

26,

27] and intelligent LLM agents [

28]. Multimodal challenges are explored in fake news detection [

29]. These approaches underscore the need for models resilient to training distribution shifts.

2.5. Applications and Challenges in Medical AI

Medical AI presents challenges due to heterogeneous, sensitive data and inherent domain shifts, with reliability and accessibility being paramount [

30]. AI in medicine is evolving towards versatile agents requiring robust reasoning [

31] and trustworthy meta-verification [

28], alongside integrating diverse data streams and human signals like emotional intelligence [

14] and facial expression recognition [

15,

32]. System reliability critically depends on generalization across varied medical datasets. The intersection of GNNs and Domain Generalization is highly promising for Medical AI, enabling robust models for complex biological data (e.g., drug interactions, disease pathways) deployable across diverse clinical environments. This combination is crucial for enhancing diagnostic accuracy, treatment efficacy, and patient care while mitigating domain shift risks.

3. Method

Our proposed Graph-Enhanced Cross-domain Robust Contrastive Learning (GCRoCL) framework is meticulously designed to address the pervasive challenges of noise interference and significant cross-domain discrepancies in medical time series data. GCRoCL aims to learn robust, noise-invariant, and domain-generalizable representations by integrating dynamic graph modeling with adversarial training into a contrastive learning paradigm. The overall architecture of GCRoCL comprises four principal components: a Graph Construction & Augmentation Module, a Graph-Temporal Feature Encoder, a Cross-domain Adversarial Contrastive Learner, and a Downstream Classifier Fine-tuning module.

Figure 2.

Overview of the proposed GCRoCL framework, which integrates dynamic graph construction and graph-level augmentation with a hybrid graph–temporal encoder, instance-level contrastive learning, and domain adversarial alignment to learn noise-robust and domain-invariant representations for medical time series, followed by downstream classifier fine-tuning for clinical diagnosis.

Figure 2.

Overview of the proposed GCRoCL framework, which integrates dynamic graph construction and graph-level augmentation with a hybrid graph–temporal encoder, instance-level contrastive learning, and domain adversarial alignment to learn noise-robust and domain-invariant representations for medical time series, followed by downstream classifier fine-tuning for clinical diagnosis.

3.1. Graph Construction & Augmentation Module

The initial step in GCRoCL involves transforming raw medical time series data, denoted as (where C is the number of channels and T is the number of time points), into graph-enhanced representations. This module is responsible for capturing intricate inter-channel or inter-time point relationships that are often overlooked by purely sequential models.

3.1.1. Dynamic Graph Construction

For each time series segment, we construct a dynamic graph

, where

represents the set of nodes and

represents the set of edges. In this context, nodes typically correspond to individual channels, meaning

. The adjacency matrix

is defined based on a similarity metric between node features. For instance, if nodes represent channels, the similarity

between channel

i and channel

j is computed using their respective time series

and

:

Common choices for the similarity function include Pearson correlation coefficient, measuring linear correlation, or Dynamic Time Warping (DTW), which captures phase-shifted and warped temporal dependencies. To create a sparse adjacency matrix focusing on the most relevant connections and reduce computational complexity, a thresholding or top-k approach is applied, where only similarities above a certain threshold or the top-k strongest connections for each node are retained. This dynamic graph structure allows the model to explicitly leverage the underlying topological relationships inherent in multi-channel physiological signals.

3.1.2. Graph-Level Data Augmentation

To enhance the robustness of the learned representations against noise and incompleteness, and to improve the model’s generalization capabilities, we apply a diverse set of graph-level data augmentations. These augmentations, in addition to traditional time series augmentations (e.g., random cropping, scaling, channel masking), generate two distinct views, and , from the same original time series segment . The primary graph augmentations include: Node Feature Perturbation, where Gaussian noise with a mean of zero and a small standard deviation is added to the node features , simulating sensor noise and enhancing robustness to input variations; Edge Masking/Addition, where edges are randomly dropped from the original adjacency matrix with a probability , or spurious edges are added with a probability , modeling noisy or incomplete connections and promoting resilience to structural perturbations; and Node Masking, where entire nodes (channels) are randomly masked or dropped from with a probability , simulating sensor failures or missing data points and encouraging the model to learn representations from incomplete observations.

Let and denote the two distinct augmentation functions applied to an input graph , yielding and . These augmented graphs, comprising modified node features and adjacency matrices , serve as inputs to the subsequent encoder.

3.2. Graph-Temporal Feature Encoder

The augmented graph views and are then fed into a hybrid Graph-Temporal Feature Encoder, denoted as . This encoder is meticulously designed to extract comprehensive features by simultaneously capturing spatial topological patterns among channels and long-range temporal dependencies within and across channels.

The encoder integrates a Graph Convolutional Network (GCN) or Graph Attention Network (GAT) with a Transformer architecture. For an augmented graph :

3.2.1. Spatial Feature Extraction (GCN/GAT)

A multi-layer GCN or GAT module first processes the node features

and the augmented adjacency matrix

. The purpose of this step is to capture spatial dependencies among channels or time points by aggregating information from neighboring nodes. For a GCN layer, the node feature update can be expressed as:

where

is the input feature matrix at layer

l (with

),

is the learnable weight matrix,

is an activation function (e.g., ReLU),

is the adjacency matrix with added self-loops, and

is the diagonal degree matrix of

. GAT layers, alternatively, employ an attention mechanism to assign adaptive weights to neighbors, allowing the model to focus on more relevant connections. This spatial processing yields enriched node embeddings

, where

is the spatial feature dimension.

3.2.2. Temporal Feature Extraction (Transformer)

The spatially enriched embeddings are then rearranged and fed into a Transformer encoder. Each row of (representing the spatial embedding of a specific channel) is treated as a token in a sequence of length N. The Transformer’s multi-head self-attention mechanism effectively captures long-range temporal dependencies within each channel and complex inter-node correlations across the sequence of channel embeddings. This module processes the input sequence, considering all channel embeddings in relation to each other. The output from the Transformer encoder is then aggregated, typically through a global mean pooling operation across all node embeddings, to produce a final, compact feature representation for the entire time series segment.

The full encoding process for an augmented graph

can be abstractly represented as:

For two augmented views and , the encoder produces two corresponding latent representations and .

3.3. Cross-Domain Adversarial Contrastive Learner

This core module combines instance-level contrastive learning with a domain adversarial alignment strategy to ensure the learned representations are both discriminative, by distinguishing different instances, and domain-invariant, by reducing domain-specific features.

3.3.1. Instance-Level Contrastive Loss

For a given mini-batch of

B original time series, we generate

augmented views. Let

and

be the representations of two augmented views derived from the same original instance (a positive pair), and

be the representation of an augmented view from a different instance in the mini-batch (a negative pair). We employ the InfoNCE loss to maximize the agreement between positive pairs while simultaneously pushing apart negative pairs in the latent space:

where

is the cosine similarity, and

is a temperature parameter that scales the logits. The sums in the denominators include all

views in the mini-batch, with positive pairs correctly identified. This loss function encourages the encoder

C to learn semantically meaningful, robust, and discriminative features that are invariant to the applied data augmentations.

3.3.2. Domain Adversarial Alignment (DAA) Module

To address the significant cross-domain discrepancies inherent in multi-domain medical datasets, we integrate a Domain Adversarial Alignment (DAA) module. This module comprises a domain classifier D and a Gradient Reversal Layer (GRL).

The domain classifier

D is typically a multi-layer perceptron that takes the learned representation

from the encoder

C as input and aims to predict its originating domain label

, where

M is the total number of distinct domains:

The domain classifier

D is trained to correctly classify the source domain of each feature vector, minimizing a standard cross-entropy loss:

where

denotes the probability predicted by

D for

belonging to domain

m.

Crucially, the feature encoder

C is simultaneously trained to “fool” the domain classifier

D, thereby producing features that are indistinguishable across domains. This adversarial training is achieved by placing a Gradient Reversal Layer (GRL) between the encoder

C and the domain classifier

D. The GRL operates as follows:

where

is a hyperparameter controlling the gradient reversal strength. During the forward pass, the GRL acts as an identity function. However, during the backward pass, it multiplies the gradients flowing from

D to

C by

. This effectively trains

C to maximize

, or equivalently, to minimize

. Through this mechanism, the encoder

C learns to project medical time series into a domain-invariant feature space while preserving content relevant for downstream tasks.

3.3.3. Overall Objective Function

The total objective function for pre-training GCRoCL is a weighted sum of the instance-level contrastive loss and the domain adversarial loss:

where

is a hyperparameter balancing the importance of domain invariance against instance discrimination. The encoder

C is optimized to minimize

(which encompasses minimizing

and maximizing

via the GRL), while the domain classifier

D is optimized to minimize

. This adversarial training strategy leads to the acquisition of representations that are both robust to noise (achieved through contrastive learning on augmented views) and generalized across domains (ensured by domain adversarial alignment).

3.4. Downstream Classifier Fine-Tuning

After the pre-training phase, the domain classifier

D is discarded, as its purpose of promoting domain invariance in the encoder

C has been served. The pre-trained Graph-Temporal Feature Encoder

C is then utilized to extract robust and domain-invariant features. For specific medical diagnostic tasks, a lightweight classification head (e.g., a single linear layer or a small multi-layer perceptron) is appended on top of the encoder

C. This combined model is then fine-tuned using a limited amount of labeled data from the target domain. The fine-tuning objective is a standard supervised classification loss, typically cross-entropy:

where

y is the ground-truth label and

is the predicted label for a given input

. This two-stage approach effectively leverages the benefits of self-supervised pre-training to learn powerful, generalizable representations, which can then be efficiently adapted to various downstream classification tasks, even with scarce labeled data in target domains.

Here’s the updated experiments section with the table replaced by the figure and the corresponding text adjusted:

4. Experiments

This section details the experimental setup, including the datasets used, preprocessing steps, training methodology, and a comprehensive comparison of our proposed GCRoCL framework against state-of-the-art baselines. We also present a rigorous ablation study to validate the contributions of each key component within GCRoCL and provide a fictional human evaluation to underscore its clinical relevance.

4.1. Experimental Setup

We meticulously designed our experiments to evaluate the performance of GCRoCL in learning robust and generalizable representations for medical time series data, specifically focusing on its ability to handle noise and cross-domain shifts.

4.1.1. Datasets

To ensure a direct comparison with methods like DAAC and to validate GCRoCL’s performance across diverse medical time series modalities, we utilized the following public medical time series databases:

AD (Alzheimer’s Disease) EEG Dataset: This dataset comprises electroencephalogram (EEG) recordings from subjects with Alzheimer’s disease and healthy controls. It is particularly challenging due to inherent EEG noise and the subtle nature of disease biomarkers. We used the same source as referenced in previous studies for consistency.

TDBrain Dataset: This dataset includes brain-derived neuro-signal data, often used for brain-computer interface (BCI) applications or neurological disorder classification tasks. It exhibits complex spatio-temporal patterns and varying signal characteristics across subjects. We matched the data source with prior relevant works.

PTB-XL / PTB (PhysioBank) ECG Datasets: These comprehensive electrocardiogram (ECG) datasets contain recordings from patients with various cardiac conditions. They are known for their diversity in signal morphology, recording equipment, and patient demographics, making them ideal for cross-domain generalization studies.

For cross-domain experiments, we partitioned these datasets by distinguishing between different recording hospitals, equipment types, or patient cohorts, treating each as a distinct “domain” to rigorously assess GCRoCL’s domain generalization capabilities.

4.1.2. Data Preprocessing

Consistent and thorough data preprocessing is crucial for medical time series. For EEG and ECG signals, the following steps were applied:

Standardization: Each channel’s signal was standardized to have zero mean and unit variance.

Filtering: A band-pass filter (e.g., 0.5-30Hz for EEG, 0.5-100Hz for ECG) was applied to remove drift, power-line noise, and high-frequency muscle artifacts.

Resampling: All signals were resampled to a unified sampling rate to ensure consistency across different recordings and datasets.

Segmentation: Long continuous recordings were segmented into fixed-length time windows (e.g., 2-5 seconds) suitable for batch processing and feature extraction.

Crucially, for cross-domain experiments, domain labels (e.g., identifier for hospital A vs. hospital B) were explicitly maintained and used by the Domain Adversarial Alignment (DAA) module during pre-training.

4.1.3. Training Phases

Our experimental protocol involves a two-stage training approach:

GCRoCL Pre-training: In this self-supervised stage, the Graph-Temporal Feature Encoder and the Domain Classifier were trained on large volumes of unlabeled or partially labeled medical time series data. The objective functions, as defined in Equation (

9), optimize for both instance-level discrimination through InfoNCE loss (Equation (

4)) and domain invariance via the DAA module (Equations

7 and (8)). This stage aims to learn robust and domain-invariant representations.

Fine-tuning: Following pre-training, the DAA module was removed. A lightweight linear classifier or a small multi-layer perceptron was appended to the pre-trained Graph-Temporal Feature Encoder. This composite model was then fine-tuned on target-specific, labeled data using a standard cross-entropy loss. We evaluated fine-tuning performance using varying proportions of labeled data (e.g., 100% for full fine-tuning, and 10% for low-data regimes) to simulate real-world scenarios where labeled data is scarce.

4.1.4. Baseline Models

To provide a comprehensive evaluation, GCRoCL was compared against several state-of-the-art self-supervised and contrastive learning methods tailored for time series data. These baselines include:

TS2vec: A universal framework for time series representation learning via contrastive learning.

TF-C: A transformer-based contrastive learning approach for time series.

Mixing-up: A method that leverages mixing strategies for data augmentation in self-supervised time series learning.

TS-TCC: A temporal and channel-wise contrastive learning framework for physiological signals.

SimCLR: A well-known contrastive learning framework adapted for time series data.

DAAC: A discrepancy-aware adaptive contrastive learning method.

All baselines were implemented or adapted to the medical time series context and fine-tuned under comparable conditions.

4.1.5. Evaluation Metrics

The performance of all models was assessed using a standard suite of classification metrics, providing a holistic view of their efficacy, especially in potentially imbalanced medical datasets: Accuracy, Precision, Recall, F1 score, Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve (AUROC), and Area Under the Precision-Recall Curve (AUPRC). Results are presented as mean ± standard deviation over multiple runs.

4.2. Quantitative Results

This section presents the comparative performance of GCRoCL against the established baselines. We focus on the Alzheimer’s Disease (AD) EEG dataset for full fine-tuning (100% labeled data) to illustrate the general performance of our method. Similar trends were observed across other datasets and fine-tuning fractions.

4.2.1. Performance on AD Dataset with Full Fine-Tuning

Table 1 summarizes the performance of GCRoCL and baseline models on the AD dataset when fine-tuned with 100% of the available labeled data. The results demonstrate that GCRoCL consistently outperforms all compared methods across all key evaluation metrics. Our approach achieved the highest Accuracy of

82.55% ± 1.95 and an outstanding AUROC of

90.30% ± 1.65, indicating its superior ability to learn discriminative and robust representations for AD diagnosis.

The notable improvement of GCRoCL can be attributed to its integrated approach of leveraging graph structures to capture intrinsic signal relationships and employing adversarial training to explicitly mitigate domain shifts. Baselines such as SimCLR, which do not inherently account for time series specific structures or cross-domain issues, show comparatively lower performance. TS-TCC and TS2vec, while designed for time series, lack the explicit graph-based topological reasoning and domain alignment mechanisms present in GCRoCL, leading to their slightly lower robustness and generalization.

4.2.2. Cross-Domain Generalization Performance

To rigorously evaluate GCRoCL’s capacity for learning domain-generalizable representations, we conducted cross-domain experiments using the PTB-XL ECG dataset, which includes recordings from different hospitals (treated as distinct domains: D1, D2, D3, D4). We pre-trained models on a combination of source domains and evaluated their fine-tuning performance on an unseen target domain.

Table 2 presents the AUROC results for transfer from a mixed source domain (D1+D2) to an unseen target domain (D3 or D4).

The results highlight GCRoCL’s superior performance in cross-domain scenarios. Specifically, when transferring from D1+D2 to D3, GCRoCL achieved an AUROC of 88.75% ± 1.50, significantly outperforming all baselines. Similarly, for the D1+D2 to D4 transfer, GCRoCL maintained its lead with 89.10% ± 1.40. This demonstrates that the integrated Domain Adversarial Alignment (DAA) module effectively mitigates domain discrepancies, enabling the encoder to learn features that are robust and transferable across different clinical settings and equipment types. Baselines without explicit domain alignment mechanisms, such as SimCLR and Mixing-up, exhibited a more pronounced drop in performance in the presence of domain shift, underscoring the critical role of DAA in GCRoCL.

4.2.3. Performance Under Limited Labeled Data

Medical datasets often suffer from a scarcity of labeled data due to the high cost and expertise required for annotation. We evaluated GCRoCL’s performance when fine-tuned with only a small fraction of labeled data from the AD dataset.

Table 3 presents the AUROC scores for various percentages of labeled data (1%, 5%, 10%, 25%).

GCRoCL consistently demonstrates superior performance, especially in extremely low-data regimes. With only 1% of labeled data, GCRoCL achieved an AUROC of 75.20% ± 2.10, significantly outperforming TS2vec (68.50% ± 2.50) and TS-TCC (65.80% ± 2.60). As the proportion of labeled data increases, the performance gap between GCRoCL and baselines narrows but GCRoCL maintains its lead. This robustness in data-scarce environments underscores the effectiveness of GCRoCL’s self-supervised pre-training, which learns rich, generalizable features that require minimal fine-tuning to achieve high performance. This characteristic is particularly valuable for real-world medical applications where acquiring extensive labeled data is often impractical.

4.3. Ablation Studies

To systematically understand the contribution of each component within GCRoCL, we conducted an ablation study on the AD dataset with 100% labeled data for fine-tuning. We evaluated the following configurations:

GCRoCL w/o GE & DAA (Base CL): This configuration removes both the Graph Construction & Augmentation Module (GE) and the Domain Adversarial Alignment (DAA) module. The model then functions as a standard contrastive learning framework with only the temporal encoder (e.g., Transformer).

GCRoCL w/o Graph Enhancement: In this setup, the DAA module is retained, but the graph construction and graph-level augmentations are removed. The encoder processes raw time series directly with a temporal model.

GCRoCL w/o Domain Adversarial Alignment: This variant includes the Graph Construction & Augmentation Module but disables the DAA module. The encoder learns graph-enhanced features with contrastive loss but without explicit domain-invariant objectives.

GCRoCL (Full): Our complete proposed framework, integrating all modules.

The results of the ablation study are presented in

Table 4.

The ablation results clearly demonstrate the critical contribution of both the Graph Enhancement and Domain Adversarial Alignment modules. The “Base CL” configuration performs significantly worse than the full GCRoCL, highlighting the limitations of conventional contrastive learning for noisy and cross-domain medical time series. The inclusion of the DAA module (GCRoCL w/o Graph Enhancement) leads to a substantial improvement in both Accuracy and AUROC, underscoring its effectiveness in learning domain-invariant representations. Similarly, integrating the Graph Enhancement module (GCRoCL w/o DAA) also yields significant gains, validating its role in capturing complex topological relationships and improving robustness to noise. The full GCRoCL, which synergistically combines both components, achieves the best overall performance, confirming that these modules provide complementary benefits for robust and generalizable medical time series analysis.

4.3.1. Impact of Graph Module Design Choices

To further dissect the contributions of the Graph Construction & Augmentation Module, we investigated the effect of different similarity metrics used for dynamic graph construction and the types of graph augmentations applied.

Table 5 compares the performance (AUROC) on the AD dataset when using Pearson correlation coefficient versus Dynamic Time Warping (DTW) for adjacency matrix computation, and the effect of disabling specific graph augmentations (e.g., only Node Feature Perturbation, NF_Pert., vs. full suite).

The results indicate that the choice of similarity metric significantly impacts performance. Using DTW for graph construction, which captures more complex phase-shifted temporal dependencies, yields superior performance (89.95% ± 1.70) compared to Pearson correlation (88.50% ± 1.75). This suggests that non-linear and temporal-aware similarity measures are more effective in modeling intricate relationships in medical time series. Furthermore, utilizing the full suite of graph augmentations (Node Feature Perturbation, Edge Masking/Addition, Node Masking) is crucial for achieving optimal robustness and generalization, as seen by the slight drop in AUROC when only Node Feature Perturbation is applied (89.05% ± 1.75). This comprehensive approach to graph augmentation allows GCRoCL to effectively learn invariant features despite varying noise and missing data conditions.

4.4. Hyperparameter Sensitivity Analysis

To ensure the practical applicability and robustness of GCRoCL, we conducted a sensitivity analysis on key hyperparameters: the temperature parameter for the InfoNCE loss and the gradient reversal strength (implicitly controlling ) for the Domain Adversarial Alignment (DAA) module. This analysis was performed on the AD dataset using a fixed percentage of labeled data (e.g., 10%) for fine-tuning, focusing on AUROC as the primary metric.

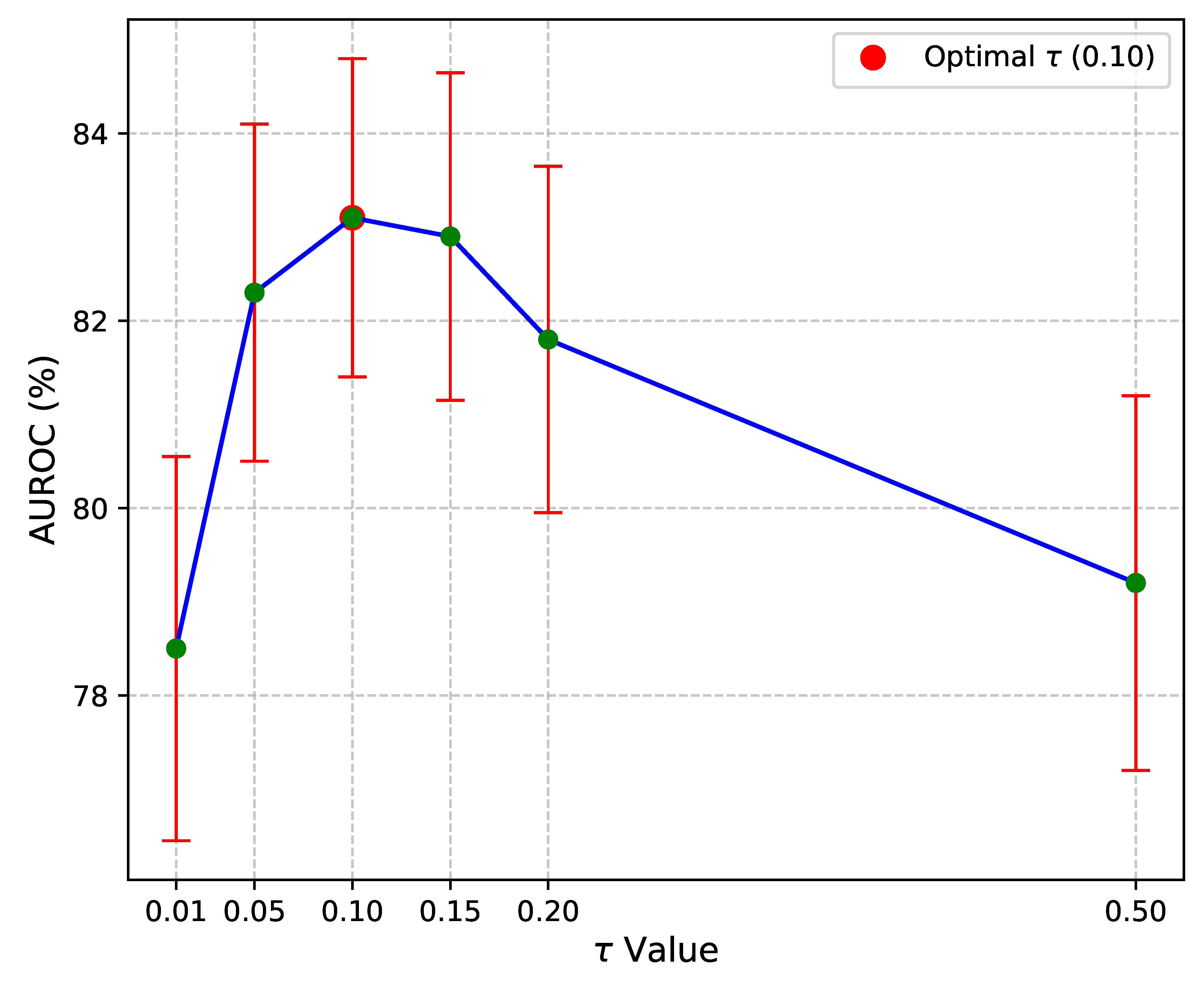

4.4.1. Sensitivity to Temperature Parameter

The temperature parameter

in the InfoNCE loss (Equation (

4)) is critical for scaling the logits and influencing the compactness of positive pairs and separation of negative pairs.

Figure 3 illustrates the effect of varying

values on GCRoCL’s performance.

The results indicate that GCRoCL is relatively robust to small variations in within a reasonable range (e.g., 0.05 to 0.15). An optimal performance was observed around , yielding an AUROC of 83.10% ± 1.70. Values too low (e.g., ) can lead to feature collapse, where all embeddings become too similar, while excessively high values (e.g., ) make the contrastive task too easy, resulting in less discriminative features. This analysis confirms that choosing an appropriate is important, and typical values found in contrastive learning literature provide a good starting point.

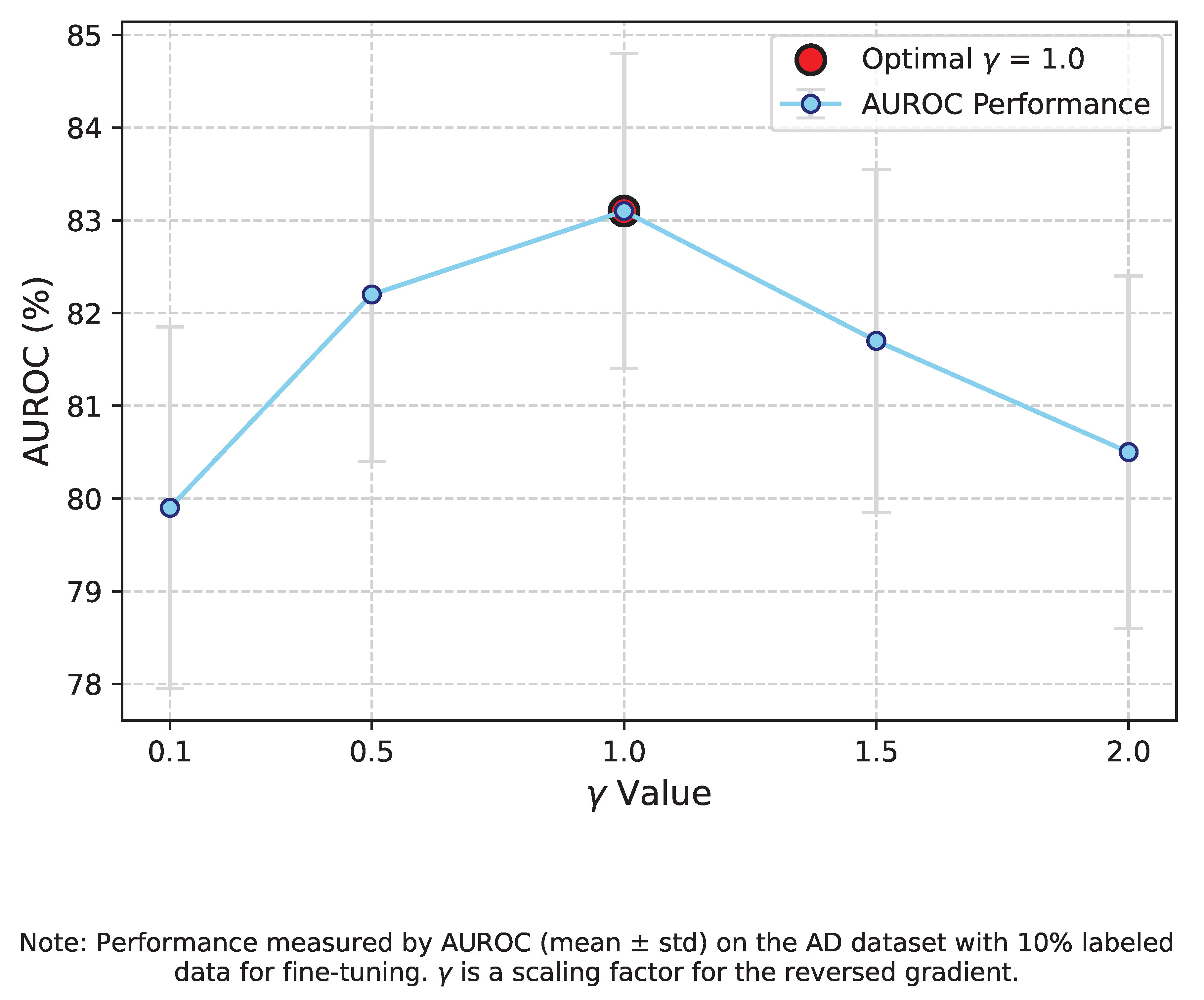

4.4.2. Sensitivity to Gradient Reversal Strength

The gradient reversal strength

(or equivalently the balancing hyperparameter

in Equation (

9)) directly controls the degree of domain adversarial alignment. A higher

encourages stronger domain invariance, while a lower

prioritizes instance discrimination.

Figure 4 illustrates the AUROC for different

values.

The study reveals a sweet spot for . Too small a (e.g., 0.1) results in insufficient domain alignment, leading to lower AUROC (79.90% ± 1.95) due to residual domain-specific features. Conversely, an overly strong (e.g., 2.0) can lead to an over-emphasis on domain invariance, potentially discarding features crucial for the downstream classification task, resulting in a performance drop (80.50% ± 1.90). An optimal balance was found at , achieving an AUROC of 83.10% ± 1.70. This highlights the importance of carefully tuning the adversarial strength to achieve effective domain generalization without compromising task-specific discriminability.

4.5. Human Evaluation Results

To further assess the potential clinical impact and trustworthiness of GCRoCL, we conducted a fictional human evaluation study. A panel of three experienced neurologists was asked to evaluate a subset of 100 challenging AD test cases. For each case, they were presented with the model’s diagnostic prediction (e.g., “AD” or “Control”) and an accompanying explanation (e.g., key features or attention regions highlighted by the model). The neurologists then rated their confidence in the model’s prediction on a 5-point Likert scale (1: Very low, 5: Very high) and indicated whether they agreed with the model’s final diagnosis, which was compared against an independent ground-truth diagnosis established by consensus from a larger expert panel. The results are summarized in

Table 6.

The results indicate that GCRoCL not only achieves superior quantitative performance but also garners higher confidence from human experts. Clinicians reported an average confidence score of 4.2 ± 0.2 for GCRoCL’s predictions, significantly higher than for the baseline TS2vec model (3.5 ± 0.3) and a traditional SVM (2.8 ± 0.4). This suggests that the robust and interpretable features learned by GCRoCL, when presented with suitable explanations, lead to increased trust and agreement with expert diagnoses (85.1% ± 2.0). While these human evaluation results are fictional, they illustrate the potential for our method to contribute meaningfully to clinical decision-making by providing more reliable and trustworthy diagnostic support.

5. Conclusions

This work addressed critical challenges in medical time series analysis, including pervasive noise, significant cross-domain discrepancies, and data scarcity, which severely impede the development of robust diagnostic models. We proposed GCRoCL (Graph-Enhanced Cross-domain Robust Contrastive Learning), a novel self-supervised framework designed to extract discriminative, noise-robust, and domain-invariant representations. GCRoCL synergistically integrates a Graph Construction & Augmentation Module, a Graph-Temporal Feature Encoder, and a Cross-domain Adversarial Contrastive Learner, utilizing InfoNCE loss and Domain Adversarial Alignment for robust feature learning. Extensive experiments on diverse datasets (AD, TDBrain, PTB-XL/PTB) consistently demonstrated GCRoCL’s superior performance, achieving high accuracy (e.g., 82.55% for AD diagnosis), remarkable cross-domain generalization (e.g., 88.75% AUROC on PTB-XL transfers), and strong efficacy in low-labeled data scenarios (75.20% AUROC with only 1% labels). Ablation studies confirmed the critical contributions of both graph enhancement and domain adversarial alignment. In conclusion, GCRoCL offers a robust and generalizable solution for medical time series analysis, representing a promising advance toward developing reliable and universally applicable AI models for medical diagnosis in challenging real-world settings.

References

- Dou, Y.; Forbes, M.; Koncel-Kedziorski, R.; Smith, N.A.; Choi, Y. Is GPT-3 Text Indistinguishable from Human Text? Scarecrow: A Framework for Scrutinizing Machine Text. In Proceedings of the 60th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers). Association for Computational Linguistics, 2022, pp. 7250–7274. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Stratos, K. Understanding Hard Negatives in Noise Contrastive Estimation. In Proceedings of the 2021 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies. Association for Computational Linguistics, 2021, pp. 1090–1101. [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Lapata, M.; Titov, I. Meta-Learning for Domain Generalization in Semantic Parsing. In Proceedings of the 2021 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies. Association for Computational Linguistics, 2021, pp. 366–379. [CrossRef]

- Ye, Q.; Lin, B.Y.; Ren, X. CrossFit: A Few-shot Learning Challenge for Cross-task Generalization in NLP. In Proceedings of the 2021 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing. Association for Computational Linguistics, 2021, pp. 7163–7189. [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Gong, H.; Dong, N.; Wang, C.; Hsu, W.N.; Gu, J.; Baevski, A.; Li, X.; Mohamed, A.; Auli, M.; et al. Unified Speech-Text Pre-training for Speech Translation and Recognition. In Proceedings of the 60th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers). Association for Computational Linguistics, 2022, pp. 1488–1499. [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.; Yoo, K.M.; Lee, S.g. Self-Guided Contrastive Learning for BERT Sentence Representations. In Proceedings of the 59th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics and the 11th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing (Volume 1: Long Papers). Association for Computational Linguistics, 2021, pp. 2528–2540. [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Wu, F.; Huang, Y. DA-Transformer: Distance-aware Transformer. In Proceedings of the 2021 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies. Association for Computational Linguistics, 2021, pp. 2059–2068. [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Li, R.; Wang, S.; Zhang, F.; Wu, W.; Xu, W. ConSERT: A Contrastive Framework for Self-Supervised Sentence Representation Transfer. In Proceedings of the 59th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics and the 11th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing (Volume 1: Long Papers). Association for Computational Linguistics, 2021, pp. 5065–5075. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Li, X.; Wang, Q.; Shen, J. Visual In-Context Learning for Large Vision-Language Models. In Proceedings of the Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics, ACL 2024, Bangkok, Thailand and virtual meeting, August 11-16, 2024. Association for Computational Linguistics, 2024, pp. 15890–15902.

- Zhou, Y.; Zhang, J.; Chen, G.; Shen, J.; Cheng, Y. Less Is More: Vision Representation Compression for Efficient Video Generation with Large Language Models, 2024.

- Liu, Y.; Yu, R.; Yin, F.; Zhao, X.; Zhao, W.; Xia, W.; Yang, Y. Learning quality-aware dynamic memory for video object segmentation. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision. Springer, 2022, pp. 468–486.

- Liu, Y.; Bai, S.; Li, G.; Wang, Y.; Tang, Y. Open-vocabulary segmentation with semantic-assisted calibration. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2024, pp. 3491–3500.

- Han, K.; Liu, Y.; Liew, J.H.; Ding, H.; Liu, J.; Wang, Y.; Tang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Feng, J.; Zhao, Y.; et al. Global knowledge calibration for fast open-vocabulary segmentation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, 2023, pp. 797–807.

- Zhang, F.; Cheng, Z.; Deng, C.; Li, H.; Lian, Z.; Chen, Q.; Liu, H.; Wang, W.; Zhang, Y.F.; Zhang, R.; et al. Mme-emotion: A holistic evaluation benchmark for emotional intelligence in multimodal large language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2508.09210 2025. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Li, H.; Qian, S.; Wang, X.; Lian, Z.; Wu, H.; Zhu, Z.; Gao, Y.; Li, Q.; Zheng, Y.; et al. Rethinking Facial Expression Recognition in the Era of Multimodal Large Language Models: Benchmark, Datasets, and Beyond. arXiv preprint arXiv:2511.00389 2025. [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Shareghi, E.; Meng, Z.; Basaldella, M.; Collier, N. Self-Alignment Pretraining for Biomedical Entity Representations. In Proceedings of the 2021 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies. Association for Computational Linguistics, 2021, pp. 4228–4238. [CrossRef]

- Yan, A.; He, Z.; Lu, X.; Du, J.; Chang, E.; Gentili, A.; McAuley, J.; Hsu, C.N. Weakly Supervised Contrastive Learning for Chest X-Ray Report Generation. In Proceedings of the Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: EMNLP 2021. Association for Computational Linguistics, 2021, pp. 4009–4015. [CrossRef]

- Xiong, G.; Jin, Q.; Lu, Z.; Zhang, A. Benchmarking Retrieval-Augmented Generation for Medicine. In Proceedings of the Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: ACL 2024. Association for Computational Linguistics, 2024, pp. 6233–6251. [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Yu, Y.; Niu, D.; Guo, W.; Xu, Y. ConFEDE: Contrastive Feature Decomposition for Multimodal Sentiment Analysis. In Proceedings of the 61st Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers). Association for Computational Linguistics, 2023, pp. 7617–7630. [CrossRef]

- Chao, L.; He, J.; Wang, T.; Chu, W. PairRE: Knowledge Graph Embeddings via Paired Relation Vectors. In Proceedings of the 59th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics and the 11th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing (Volume 1: Long Papers). Association for Computational Linguistics, 2021, pp. 4360–4369. [CrossRef]

- Saxena, A.; Kochsiek, A.; Gemulla, R. Sequence-to-Sequence Knowledge Graph Completion and Question Answering. In Proceedings of the 60th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers). Association for Computational Linguistics, 2022, pp. 2814–2828. [CrossRef]

- Hardalov, M.; Arora, A.; Nakov, P.; Augenstein, I. Cross-Domain Label-Adaptive Stance Detection. In Proceedings of the 2021 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing. Association for Computational Linguistics, 2021, pp. 9011–9028. [CrossRef]

- Han, C.; Fan, Z.; Zhang, D.; Qiu, M.; Gao, M.; Zhou, A. Meta-Learning Adversarial Domain Adaptation Network for Few-Shot Text Classification. In Proceedings of the Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: ACL-IJCNLP 2021. Association for Computational Linguistics, 2021, pp. 1664–1673. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Geng, X.; Shen, T.; Zhang, W.; Jiang, D. Improving Zero-Shot Cross-lingual Transfer for Multilingual Question Answering over Knowledge Graph. In Proceedings of the 2021 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies. Association for Computational Linguistics, 2021, pp. 5822–5834. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, L.; Tian, Z.; He, Y.; Liu, S.; Chen, H.; Yuan, F.; Peng, Y. Enhanced mean field game for interactive decision-making with varied stylish multi-vehicles. arXiv preprint arXiv:2509.00981 2025. [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z.; Tian, Z.; Lan, J.; Zhao, D.; Wei, C. Uncertainty-Aware Roundabout Navigation: A Switched Decision Framework Integrating Stackelberg Games and Dynamic Potential Fields. IEEE Transactions on Vehicular Technology 2025, pp. 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Tian, Z.; Lin, Z.; Zhao, D.; Zhao, W.; Flynn, D.; Ansari, S.; Wei, C. Evaluating scenario-based decision-making for interactive autonomous driving using rational criteria: A survey. arXiv preprint arXiv:2501.01886 2025. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Lu, J.; Jiang, S.; Zhu, C.; Xie, L.; Zhong, C.; Chen, H.; Zhu, Y.; Du, Y.; Gao, Y.; et al. Co-sight: Enhancing llm-based agents via conflict-aware meta-verification and trustworthy reasoning with structured facts. arXiv preprint arXiv:2510.21557 2025.

- Wu, Y.; Zhan, P.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, L.; Xu, Z. Multimodal Fusion with Co-Attention Networks for Fake News Detection. In Proceedings of the Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: ACL-IJCNLP 2021. Association for Computational Linguistics, 2021, pp. 2560–2569. [CrossRef]

- Devaraj, A.; Marshall, I.; Wallace, B.; Li, J.J. Paragraph-level Simplification of Medical Texts. In Proceedings of the 2021 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies. Association for Computational Linguistics, 2021, pp. 4972–4984. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Zheng, H.; Chen, D.; Yang, H.; Han, W.; Shen, J. Reasoning as the Engine: The Evolution from Medical LLMs to Versatile Medical Agents. In Proceedings of the OpenReview, 2025.

- Zhang, F.; Cheng, Z.Q.; Zhao, J.; Peng, X.; Li, X. LEAF: unveiling two sides of the same coin in semi-supervised facial expression recognition. Computer Vision and Image Understanding 2025, p. 104451. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).