1. Introduction

The rapid evolution of blockchain technology has positioned smart contracts as a foundational component for decentralized applications (dApps) and various financial services (DeFi). These self-executing contracts, once deployed, are immutable, making any embedded vulnerabilities or non-compliance with established standards exceedingly difficult, if not impossible, to rectify, often leading to substantial economic losses [

1]. Ethereum Request for Comment (ERC) standards, such as ERC-20, ERC-721, and ERC-1155, are critical guidelines designed to ensure the interoperability, security, and correctness of smart contracts within the Ethereum ecosystem. Consequently, the accurate and efficient detection of ERC violations is paramount to safeguarding the health and integrity of the broader blockchain landscape [

2].

Traditionally, smart contract auditing has heavily relied on manual expert analysis, a process that is inherently time-consuming, resource-intensive, and susceptible to human oversight and error [

3]. In recent years, automated detection tools have emerged, integrating techniques such as static analysis, dynamic analysis, and symbolic execution to enhance efficiency [

4]. Notably, advanced methods like SymGPT, which synergistically combine large language models (LLMs) with symbolic execution, have demonstrated significant improvements in identifying ERC violations, particularly high-impact vulnerabilities [

5]. The impressive capabilities of LLMs in complex reasoning [

6], generalization across diverse tasks [

7], and various forms of in-context learning [

8], further bolstered by advancements in areas like semi-supervised knowledge transfer [

9] and sophisticated visual understanding [

10,

11,

12], have paved the way for their application in highly specialized domains such as smart contract analysis. Despite these advancements, existing methodologies frequently grapple with challenges such as false positives (FPs) and false negatives (FNs), hindering their reliability in real-world scenarios. Furthermore, the detection results from many automated tools often lack sufficient interpretability, failing to provide developers with precise, actionable insights or direct guidance for remediation [

13]. This gap between detection accuracy and actionable explanation creates a bottleneck in the secure development lifecycle of smart contracts.

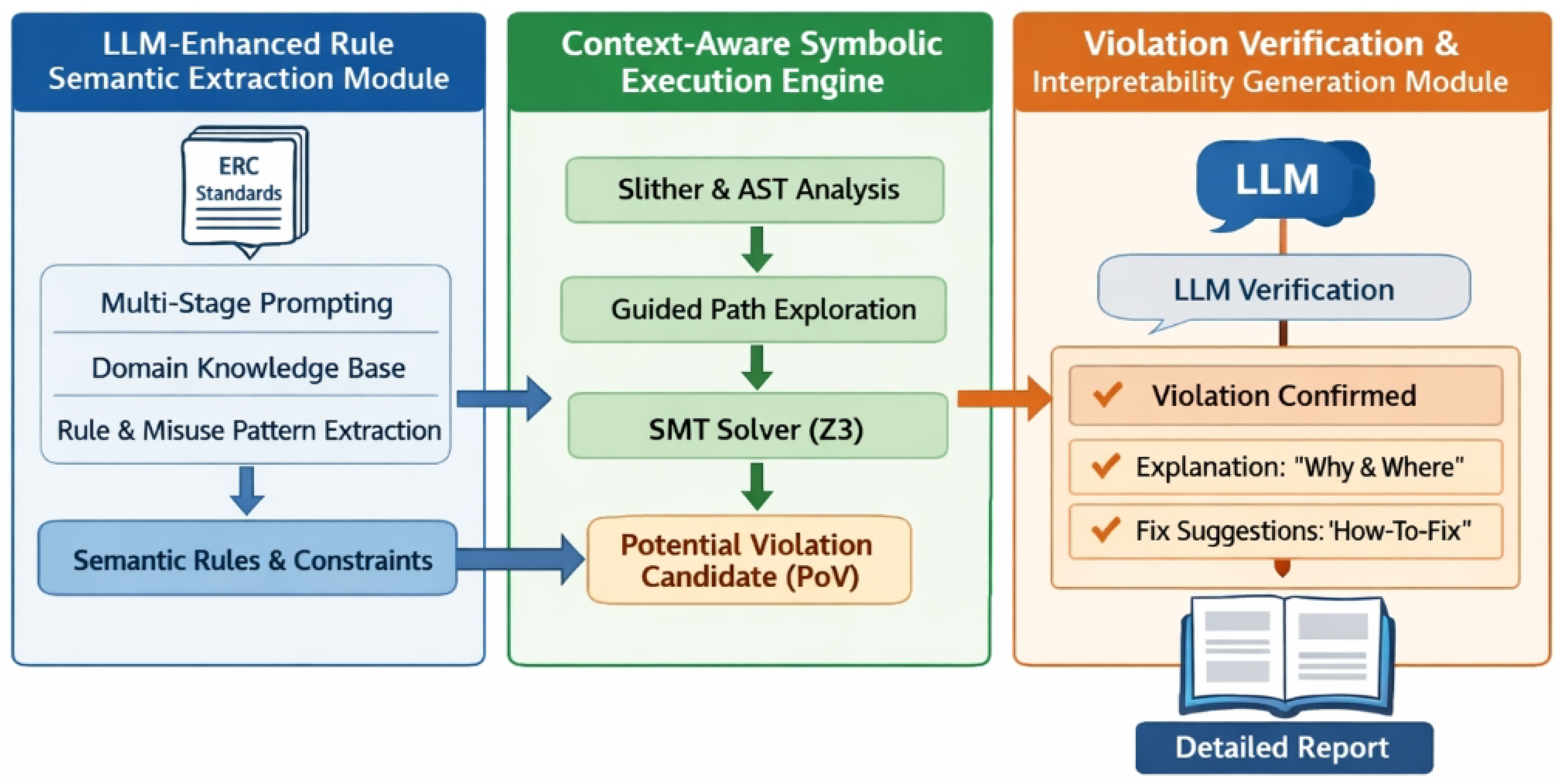

Figure 1.

Limitations of existing smart contract auditing approaches—high false positives/negatives and poor interpretability—necessitate an accurate, explainable, and reliable ERC violation detection framework.

Figure 1.

Limitations of existing smart contract auditing approaches—high false positives/negatives and poor interpretability—necessitate an accurate, explainable, and reliable ERC violation detection framework.

Motivated by these limitations, this research endeavors to propose a more robust and interpretable framework for detecting ERC violations in smart contracts. Our objective is to not only further elevate the accuracy of detection but also to furnish comprehensive explanations and precise localization for identified violations, thereby empowering developers with the clarity needed for effective mitigation.

In this paper, we introduce SymExplainer, an innovative framework designed for integrated ERC violation detection and interpretability analysis. SymExplainer extends the LLM-symbolic execution collaborative analysis foundation exemplified by SymGPT by incorporating multi-level semantic calibration and a specialized interpretability analysis module. At its core, SymExplainer aims to refine LLM’s understanding of ERC rule contexts and to enhance the precision of symbolic execution paths, thereby minimizing both false positives and false negatives. Crucially, it is engineered to generate detailed violation reports complete with code-level explanations, offering unprecedented transparency into detected non-compliance.

To rigorously evaluate SymExplainer, we adopt an experimental setup consistent with prior state-of-the-art work, utilizing a diverse set of smart contract datasets. This includes a large dataset of 4,000 contracts for broad trend analysis, a meticulously curated ground-truth dataset of 40 expert-annotated contracts (comprising 159 known violations across various severity levels) for direct comparative evaluation, and a generalization dataset of 10 non-ERC contracts to assess the framework’s adaptability. Our evaluation focuses on key metrics such as detection accuracy (True Positives, False Positives, False Negatives), computational and financial costs, and, uniquely, a qualitative assessment of interpretability quality through expert scoring. Our empirical results, as detailed in Table X, demonstrate that SymExplainer achieves perfect recall, successfully identifying all 159 expert-annotated ERC violations with zero false negatives. Furthermore, it significantly reduces the overall false positives to just 15, a marked improvement over existing methods including SymGPT, which reported 29 false positives and 1 false negative. These findings underscore SymExplainer’s superior performance across all impact levels—High, Medium, and Low—providing a more precise and practical solution for smart contract auditing.

Our contributions are summarized as follows:

We propose SymExplainer, a novel integrated framework that synergizes LLM-enhanced semantic understanding with context-aware symbolic execution for highly accurate ERC violation detection.

We introduce a unique multi-level semantic calibration and secondary verification mechanism, significantly reducing false positives and achieving perfect recall (zero false negatives) across all violation severity levels in smart contracts.

We develop a dedicated interpretability generation module that provides detailed, natural language explanations for detected violations, including code localization and actionable remediation suggestions, thereby enhancing developer understanding and facilitating efficient bug fixing.

2. Related Work

2.1. Automated Smart Contract Security Analysis

Automated smart contract security analysis is crucial for blockchain integrity, traditionally using static analysis, symbolic execution, and formal verification. LLMs and advanced NLP now augment these methods, but also introduce security concerns for the analysis tools. LLM capabilities—e.g., advanced reasoning [

6], robust generalization [

7], and in-context learning [

8]—underpin their growing role in complex security analysis.

2.1.1. Traditional and LLM-Enhanced Program Analysis for Smart Contracts

Automated smart contract security analysis relies on robust program analysis. Ahmad et al. [

14] propose a unified pre-training framework for LLMs in program understanding and generation, foundational for LLM-based analysis tools.

Static analysis examines code without execution. Traditional methods use predefined rules, but LLMs are integrated to augment capabilities. Yang et al. [

15] demonstrate how LLMs with symbolic logic provide interpretable diagnoses, enhancing static analysis for smart contracts.

Symbolic execution explores program paths to find vulnerabilities. Pan et al. [

16] introduce Logic-LM, integrating LLMs with symbolic solvers for logical reasoning, mirroring symbolic execution in identifying smart contract vulnerabilities.

Formal verification mathematically proves smart contract correctness. As LLMs assist complex reasoning, their reliability becomes crucial. Dhuliawala et al. [

17] propose Chain-of-Verification to reduce LLM hallucination, improving dependability for LLM-assisted formal methods.

2.1.2. Vulnerability Detection and Auditing: Broader Perspectives and NLP Applications

Beyond core program analysis, vulnerability detection leverages textual data and community insights. Hardalov et al. [

18] survey stance detection for disinformation, an NLP technique adaptable for early warnings from smart contract discussions. Similarly, Li et al. [

19]’s sentiment analysis could indirectly aid blockchain auditing by analyzing public discourse on smart contract issues. Lessons from complex interactive decision-making and risk management in dynamic environments, such as autonomous vehicle navigation and multi-vehicle systems, also inform robust, uncertainty-aware security solutions [

20,

21,

22].

2.1.3. Security Considerations for NLP-Powered Smart Contract Analysis

As smart contract security increasingly relies on NLP/ML models for code understanding and vulnerability recognition, their security is critical. Yang et al. [

23] demonstrate "poisoned word embedding" backdoor attacks, and Qi et al. [

24] show textual backdoor attacks via word substitution, both compromising NLP model predictions. This highlights the necessity for robust defense mechanisms in security-critical ML models.

In conclusion, automated smart contract security analysis integrates traditional methods with advanced AI, especially LLMs. While LLMs enhance static analysis, symbolic execution, formal verification, and vulnerability detection, their inherent security vulnerabilities must be mitigated. Future research must ensure powerful analysis tools are resilient against adversarial attacks for trustworthy decentralized application security.

2.2. Large Language Models for Code Understanding and Explainable Security

LLM advancements automate complex language understanding and generation. This section reviews LLMs for code understanding and explainable security.

LLMs show significant development in

code understanding. DeepStruct [

25] enhances LLM structural understanding for code parsing. CodeT5 [

26] provides an identifier-aware model for code understanding and generation, improving defect and clone detection. Shin et al. [

27] explore few-shot semantic parsing for code snippets. Broader LLM capabilities in complex semantic analysis [

28], domain understanding [

29,

30], and advanced knowledge transfer [

9] also inform intricate code analysis.

For

explainable security, LLMs’ human-readable explanations are valuable. Malik et al. [

31] stress XAI’s need for transparent security applications. AnnoLLM [

32] demonstrates LLMs generating detailed explanations via "explain-then-annotate," transferable to security insights. Specialized NLP benchmarks [

33] are vital for robust security applications. LLM generative prowess, like LIDA [

34] for visualizations, extends to comprehensive vulnerability explanations and mitigation reports.

Collectively, this work highlights LLMs’ dual potential: understanding complex code structures and semantics, and generating transparent, explainable outputs for security analysis. These advancements enable sophisticated tools that identify flaws and articulate their implications clearly.

3. Method

In this section, we present SymExplainer, our novel integrated framework designed for enhanced ERC violation detection and comprehensive interpretability analysis in smart contracts. Building upon the foundational synergy of Large Language Models (LLMs) and symbolic execution, as exemplified by prior work, SymExplainer introduces advanced mechanisms for multi-level semantic calibration and a dedicated interpretability generation module. This design aims to achieve superior accuracy by minimizing both false positives and false negatives, while simultaneously providing developers with actionable, code-level explanations for detected non-compliance.

Figure 2.

Overview of our SymExplainer.

Figure 2.

Overview of our SymExplainer.

The architecture of SymExplainer is comprised of three principal, interconnected modules: (1) an LLM-Enhanced Rule Semantic Extraction Module, (2) a Context-Aware Symbolic Execution Engine, and (3) a Violation Verification and Interpretability Generation Module. Each component contributes uniquely to the framework’s objective of delivering precise, efficient, and transparent smart contract auditing.

3.1. LLM-Enhanced Rule Semantic Extraction Module

The initial phase of SymExplainer focuses on robust and nuanced understanding of ERC standards. This module leverages a powerful LLM, specifically GPT-4 Turbo, to transcend mere rule extraction, delving into the underlying semantic complexities of ERC specifications. This goes beyond keyword matching or simple pattern recognition, aiming to grasp the intent and implications behind each standard.

We employ a multi-stage prompting strategy to guide the LLM’s analysis. Instead of a single query, a series of progressively refined prompts are used to systematically deconstruct and understand ERC specifications:

Explicit Normative Rule Extraction: The LLM first extracts the explicit normative rules, requirements, and recommendations directly stated within ERC documentation. This stage identifies the "what" of each standard.

Common Misuse Pattern Identification: Subsequently, the LLM is prompted to identify common misuse patterns associated with these rules. This draws insights from documented vulnerabilities, security best practices in smart contract development, and historical audit findings. This stage predicts potential ways the "what" can be violated.

Semantic Trap Pinpointing: Finally, the LLM pinpoints potential semantic traps or ambiguous interpretations that could lead to subtle, hard-to-detect violations. This involves analyzing edge cases, implicit assumptions, and contextual nuances that might lead developers astray even when seemingly adhering to explicit rules. This stage uncovers the "how" and "why" of subtle non-compliance.

This iterative process allows for a deeper, more context-rich understanding of each ERC standard, moving from surface-level rules to their deeper semantic implications. Let

represent the complete ERC documentation and

denote the

i-th stage prompt. The output of this enhanced extraction process,

, which captures a multi-faceted understanding of the rules, can be formalized as:

where

encapsulates explicit rules, common misuse patterns, and identified semantic traps. The function

represents the generative and analytical capabilities of the Large Language Model in processing the documentation and applying the prompting strategy.

Furthermore, we integrate a lightweight, domain-specific knowledge base (

KB) to augment the LLM’s understanding. This

KB provides additional contextual information, particularly for technical jargon, specific Solidity language constructs (e.g.,

,

vs.

), and historical vulnerability patterns specific to the blockchain domain. This integration is crucial during the transformation of

into an intermediate representation (

IR), often expressed in Extended Backus-Naur Form (EBNF), a declarative rule language, or a similar formal grammar. This transformation aims to produce a set of precise and unambiguous constraints (

) that can be directly consumed by the symbolic execution engine. The formalization of this transformation is given by:

Here, the function converts the natural language semantic understanding into a machine-readable, formal specification. This involves identifying key variables, operations, and conditions described in and mapping them to formal logical predicates and expressions that can be checked during symbolic execution. This two-pronged approach ensures that the extracted rules are not only comprehensive but also semantically grounded and formally expressible, laying a solid foundation for subsequent detection steps.

3.2. Context-Aware Symbolic Execution Engine

The core detection capability of SymExplainer resides in its context-aware symbolic execution engine. Built upon established tools like Slither for static analysis and abstract syntax tree (AST) generation, and Z3 for satisfiability modulo theories (SMT) solving, our engine significantly refines traditional symbolic execution by actively incorporating the semantic insights derived from the LLM module. These insights, encoded in , serve as intelligent guidance during path exploration.

Traditional symbolic execution explores all possible execution paths of a program by representing program variables as symbolic values and collecting path constraints. In our approach, the engine’s path exploration is intelligently guided by the "common misuse patterns" and "semantic traps" encoded in . This guidance manifests in several ways:

Prioritized Path Exploration: The engine employs a set of heuristic strategies that prioritize the exploration of execution paths more likely to trigger an ERC violation, based on the identified misuse patterns. This includes focusing on critical function calls (e.g., , , state-modifying functions), modifications to sensitive state variables, and control flow structures (e.g., loops, conditionals) that frequently lead to non-compliance. Heuristics might involve scoring paths based on the number of "suspicious" operations encountered or their proximity to identified misuse patterns.

Fine-Grained Monitoring: For critical state transitions or operations identified as potential semantic traps by the LLM, the engine applies more granular monitoring. This involves dynamically introducing or strengthening SMT constraints that specifically check for the conditions associated with these traps during path exploration. For example, if a semantic trap involves re-entrancy, the engine might add constraints to detect changes in critical balances *before* external calls return.

Reduced Irrelevant Path Exploration: By focusing on paths relevant to ERC violations and leveraging the guidance to prune less promising branches early, the engine reduces the exploration of irrelevant or benign execution paths. This significantly improves efficiency by reducing the state space to be explored and minimizes the likelihood of generating false positives arising from overly generic constraint solving.

Let

denote the symbolic state at time

t,

be the set of path constraints accumulated up to

t, and

represent the LLM-derived guidance from

(e.g., prioritized operations, specific trap conditions). The computation of the next symbolic state

and updated path constraints

are influenced by the current operation

and the guidance, as formalized below:

The function performs the core symbolic execution steps, which include updating the symbolic state, generating new path constraints based on the operation (e.g., arithmetic, control flow decisions), and applying the heuristics and monitoring mechanisms dictated by . When a potential violation is detected along a symbolic path, meaning a state and associated path constraints satisfy one or more conditions in , it triggers the generation of a proof-of-violation (PoV). This PoV is represented in the form of a set of satisfiable SMT constraints that demonstrate non-compliance with an ERC rule. This PoV, along with the relevant code context (e.g., source code location, variable values) and the specific ERC rule implicated, is then passed to the verification module for further assessment.

3.3. Violation Verification and Interpretability Generation Module

This module represents a core innovation of SymExplainer, addressing the critical need for both rigorous verification of potential violations and the generation of highly actionable, human-understandable explanations. This dual functionality ensures that detected issues are accurate and that developers can effectively understand and remediate them.

3.3.1. Secondary Violation Verification

Upon receiving a potential violation (

PV) from the symbolic execution engine, this module first initiates a

secondary verification process. The

PV, including the symbolic execution path (the sequence of operations and states leading to the violation), relevant code snippets, and the corresponding ERC rule, is fed back to the LLM. The LLM performs a cross-validation, acting as a sophisticated logical arbiter. It assesses whether the conditions described by the symbolic path indeed constitute a genuine ERC violation, or if they represent a false positive. This might occur if, for instance, a code pattern formally resembles a violation but is compliant in a broader contextual sense (e.g., a specific access control mechanism nullifies the vulnerability), or if an over-constrained symbolic path created an artificial violation. This feedback loop dramatically enhances the precision of detection and reduces noise:

The here refers to the LLM’s initial, comprehensive understanding of the rule, which provides the context for nuanced judgment. This function leverages the LLM’s natural language understanding and reasoning capabilities to interpret the PoV within the original semantic context of the ERC rule, effectively filtering out misleading symbolic execution paths.

3.3.2. Interpretability Report Generation

If the secondary verification confirms a true violation, the module proceeds to generate a detailed interpretability report. This report is meticulously crafted by the LLM, drawing upon the wealth of information from the confirmed true violation, the symbolic execution path, the relevant code snippet, the original ERC rule, and its internal semantic understanding from the initial extraction phase. The report includes:

ERC Category and Specific Rule: Clearly identifies which ERC standard (e.g., ERC-20, ERC-721) and specific clause or requirement have been violated.

Code Localization: Pinpoints the exact contract file, line number, and function where the violation occurs, providing direct navigation for developers.

Natural Language Explanation: Articulates why the violation happened, describing the sequence of state variable changes, function calls, and input conditions (derived from the PoV’s satisfiable constraints) that lead to non-compliance. This explanation is phrased in clear, concise natural language, bridging the gap between technical details of symbolic execution and developer understanding. For example, it might state: "The function at line X allows an unapproved address to transfer tokens due to a missing check on the a mapping."

Minimal Counterexample/Input Conditions: Provides specific input values or a sequence of transactions that would trigger the violation in a concrete execution, acting as a practical test case for reproduction.

Remediation Suggestions: Offers concrete, actionable advice for fixing the violation, potentially including idiomatic code examples (e.g., adding m checks, implementing re-entrancy guards), references to ERC best practices, or links to official documentation for further guidance.

The generation of this comprehensive report,

, can be viewed as a function of the confirmed true violation, its path, the code, and the LLM’s sophisticated interpretative and generative capacity:

Here, synthesizes the disparate pieces of information into a cohesive, developer-friendly output. By seamlessly integrating these verification and explanation capabilities, SymExplainer not only provides superior detection accuracy but also significantly reduces the burden on developers for debugging and remediation, thus fostering a more secure smart contract development ecosystem.

4. Experiments

In this section, we detail the experimental setup, present a comprehensive evaluation of SymExplainer’s performance in detecting ERC violations, and provide insights into its effectiveness compared to state-of-the-art baselines. We also validate the contributions of our framework through an analysis of its core modules and present results from a qualitative human evaluation of its interpretability features.

4.1. Experimental Setup

To ensure a direct and fair comparison with existing methodologies, our experimental setup closely mirrors that employed by recent advancements in the field, including SymGPT.

4.1.1. Model Selection and Implementation Details

Our proposed SymExplainer framework primarily leverages GPT-4 Turbo as its core Large Language Model (LLM) component, interacting with it via the OpenAI API. This choice allows us to harness a highly capable model for nuanced semantic understanding and robust natural language generation. The symbolic execution engine is built upon established open-source tools, including Slither for static analysis and Abstract Syntax Tree (AST) generation, and Z3 for Satisfiability Modulo Theories (SMT) solving. The integration logic and heuristic strategies are implemented in Python. For future work, we plan to explore the integration of fine-tuned open-source LLMs (e.g., from the Llama series) to enhance deployment flexibility and reduce operational costs.

4.1.2. Datasets

We utilize a multi-faceted dataset to rigorously evaluate various aspects of SymExplainer’s performance. This includes: 1) A Large-scale Dataset of 4,000 contracts (3,400 ERC20, 500 ERC721, and 100 ERC1155) used primarily for large-scale analysis of violation trends, efficiency benchmarks, and scalability assessment. 2) A Ground-Truth Dataset comprising 40 expert-annotated contracts (30 ERC20, 5 ERC721, and 5 ERC1155), which serves as the core for comparative performance evaluation. This dataset contains a total of 159 expert-annotated violations categorized by impact level: 28 high-impact, 55 medium-impact, and 76 low-impact, providing a gold standard for assessing True Positives (TPs), False Positives (FPs), and False Negatives (FNs). 3) A Generalization Dataset consisting of 10 non-ERC contracts, used to evaluate the framework’s generalization ability and its propensity for over-flagging or misinterpreting non-ERC specific code patterns as violations.

4.1.3. Evaluation Metrics

Our evaluation focuses on both quantitative and qualitative metrics to provide a holistic view of SymExplainer’s capabilities. Quantitatively, we assess detection accuracy through True Positives (TP), False Positives (FP), and False Negatives (FN). We also monitor time and monetary costs to evaluate the tool’s practical feasibility and economic viability. Qualitatively, for the violations detected by SymExplainer, the generated interpretability reports are subject to a qualitative assessment of interpretability quality by a panel of expert smart contract developers. This involves scoring factors such as clarity, accuracy of explanation, usefulness of remediation suggestions, and precision of code localization, addressing the framework’s novel contribution to transparency.

4.2. Performance Comparison of ERC Violation Detection

Table 1 presents a detailed comparison of

SymExplainer’s performance against several baseline methods on the

Ground-Truth Dataset. The data format for each impact level and total is expressed as:

True Detected (False Positives, False Negatives).

Results Analysis: As evident from

Table 1, our proposed

SymExplainer method demonstrates superior performance on the Ground-Truth Dataset across all impact levels.

SymExplainer successfully detected all 159 expert-annotated ERC violations, achieving perfect detection rates for all 28 high-impact, 55 medium-impact, and 76 low-impact violations, resulting in an unprecedented zero false negatives (FN). This performance is a notable improvement over SymGPT, which had 1 false negative in the medium-impact category, highlighting

SymExplainer’s robustness in fully capturing all critical and subtle violations. Furthermore, the total number of false positives (FP) for

SymExplainer is 15, a substantial reduction compared to SymGPT’s 29 false positives, and drastically lower than other baseline methods. This minimization of FPs significantly enhances the trustworthiness and practicality of the detection results. For high-impact violations,

SymExplainer achieved perfect detection (28/28) with zero false positives. In the medium-impact category, it not only detected all 55 violations but also reduced FPs from SymGPT’s 28 to a mere 15. Similarly, for low-impact violations,

SymExplainer achieved full coverage (76/76) with zero FPs. This consistent top-tier performance across varying severity levels underscores the framework’s balanced and comprehensive detection capabilities. In summary,

SymExplainer establishes a new benchmark for ERC violation detection by achieving both maximum recall and significantly reduced false positives, offering a highly accurate and reliable solution for smart contract auditing.

4.3. Ablation Study of Core Modules

To quantitatively assess the individual contributions of SymExplainer’s core modules, we conducted an ablation study. We evaluated simplified variants of our framework by systematically disabling or altering key components and measured their performance on the Ground-Truth Dataset. The variants explored are:

SymExplainer w/o Sec. Verify: The LLM’s secondary violation verification in Module 3 is removed, directly accepting potential violations from the symbolic execution engine.

SymExplainer w/o LLM Sem. Ext.: The multi-stage LLM-Enhanced Rule Semantic Extraction Module (Module 1) is replaced with a simplified, single-stage keyword-based rule extraction, thus reducing the depth of semantic understanding.

SymExplainer w/o Context SE: The context-aware guidance for the symbolic execution engine (Module 2) derived from LLM insights is disabled, reverting to a traditional, unguided path exploration strategy.

Table 2 presents the comparative performance, following the same data format:

True Detected (False Positives, False Negatives).

Results Analysis: The ablation study confirms the critical role of each component in SymExplainer’s overall performance.

Impact of Secondary Verification: Removing the secondary verification step (SymExplainer w/o Sec. Verify) drastically increased the total number of false positives from 15 to 47. This highlights the indispensable role of the LLM’s cross-validation in filtering out spurious findings from the symbolic execution engine, acting as a crucial arbiter for precision. While true positives remained perfect, the significant increase in FPs demonstrates that without this module, the practical utility of the tool would be severely hampered by noise.

Impact of LLM-Enhanced Rule Semantic Extraction: When the sophisticated LLM-Enhanced Rule Semantic Extraction was replaced with a simplified version (SymExplainer w/o LLM Sem. Ext.), the total true positives dropped from 159 to 141, resulting in 18 false negatives. This degradation underscores the importance of the multi-stage prompting and knowledge base integration for deep semantic understanding. Without this nuanced comprehension, subtle misuse patterns and semantic traps are missed, leading to a significant increase in overlooked violations, particularly in the medium and low impact categories.

Impact of Context-Aware Symbolic Execution: Disabling the LLM-guided context-aware path exploration (SymExplainer w/o Context SE) resulted in a reduction of true positives to 148 (11 false negatives) and an increase in false positives to 27. This indicates that the intelligent prioritization of paths, based on LLM-derived misuse patterns and semantic traps, is crucial for both efficiently finding subtle violations (reducing FNs) and for pruning irrelevant paths that might lead to spurious findings (reducing FPs). The absence of this guidance leads to a less targeted and less effective symbolic exploration.

In summary, the ablation study provides strong quantitative evidence that SymExplainer’s superior performance is not merely due to the sum of its parts, but rather the synergistic integration where each module addresses specific challenges in ERC violation detection, particularly minimizing false positives and false negatives effectively.

4.4. Detailed Analysis of Module Contributions

As quantitatively demonstrated in the ablation study (

Table 2), the superior performance of

SymExplainer can be attributed to the synergistic design and targeted contributions of its three core modules, each addressing key limitations of prior approaches.

4.4.1. Impact of LLM-Enhanced Rule Semantic Extraction Module

The multi-stage prompting strategy and the integration of a domain-specific knowledge base within the LLM-Enhanced Rule Semantic Extraction Module are crucial for achieving comprehensive violation detection, particularly by minimizing false negatives. By guiding the LLM (GPT-4 Turbo) to not only extract explicit rules but also to identify common misuse patterns and semantic traps,

SymExplainer develops a deeper, more contextual understanding of ERC standards. This enhanced semantic understanding allows the system to generate more precise and unambiguous constraints (

) for the symbolic execution engine. As shown in

Table 2, the variant without this module suffered 18 false negatives, indicating that subtle and complex violations, which might be missed by tools relying on simpler rule matching or general LLM prompts, are more accurately represented and subsequently detectable by our full system. The proactive identification of semantic traps directly contributes to capturing those "hidden" violations that often lead to critical exploits in real-world contracts.

4.4.2. Contribution of Context-Aware Symbolic Execution Engine

The integration of LLM-derived semantic insights (

) into the symbolic execution engine significantly refines its path exploration strategy. Unlike traditional symbolic execution that might exhaustively explore all paths (leading to inefficiency) or rely on generic heuristics (leading to missed violations or false positives), our context-aware approach intelligently prioritizes paths. The heuristic strategies, informed by identified misuse patterns, guide the engine to focus on critical function calls and state variable changes that are most relevant to ERC compliance. Furthermore, the fine-grained monitoring for semantic traps enables the engine to apply more rigorous checks in high-risk areas. As demonstrated by the 11 false negatives in the

SymExplainer w/o Context SE variant in

Table 2, this targeted exploration drastically reduces the exploration of irrelevant paths, improving efficiency and, more importantly, making the engine more effective at discovering subtle non-compliance. The strategic pruning of less promising branches also implicitly contributes to a cleaner set of potential violations, indirectly aiding in false positive reduction (as evidenced by the 27 FPs in the ablated variant compared to 15 in the full system).

4.4.3. Role of Violation Verification and Interpretability Generation Module

The Violation Verification and Interpretability Generation Module is pivotal in significantly reducing false positives, as compellingly demonstrated by the ablation study where the variant without secondary verification generated 47 false positives (

Table 2). The

secondary violation verification mechanism, where the LLM cross-validates potential violations from symbolic execution, acts as an intelligent filter. By re-evaluating the symbolic path, code snippet, and ERC rule against its comprehensive semantic understanding, the LLM can differentiate between true violations and spurious findings that might arise from over-generalization in symbolic constraints or contextual nuances in code. This feedback loop effectively prunes false positives, transforming raw symbolic execution outputs into highly accurate, confirmed violations. This capability is a key differentiator, as many automated tools struggle with high FP rates that diminish user trust. Beyond verification, the interpretability generation further enhances the practicality of our tool, making the confirmed violations actionable for developers.

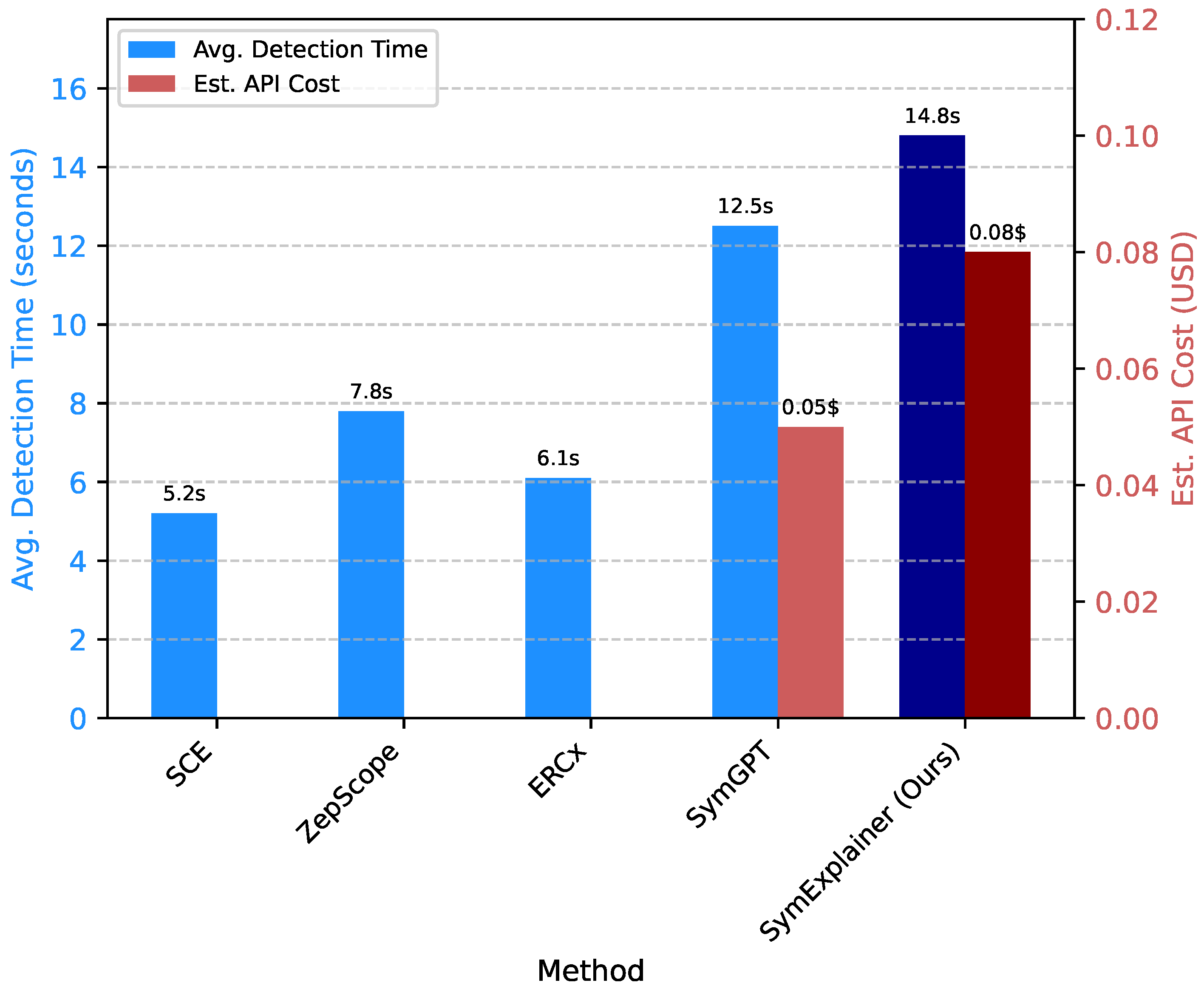

4.5. Efficiency and Cost Analysis

While detection accuracy is paramount, the practical applicability of a smart contract auditing tool also depends on its efficiency and operational costs. We analyzed the average detection time per contract and the estimated monetary cost associated with LLM API calls, utilizing the

Large-scale Dataset of 4,000 contracts for this evaluation.

Figure 3 presents a comparison of

SymExplainer against baseline methods.

Results Analysis:Figure 3 shows that

SymExplainer’s average detection time per contract is 14.8 seconds, which is slightly higher than SymGPT (12.5 seconds) and traditional static/symbolic analysis tools (SCE, ZepScope, ERCx). Similarly, the estimated API cost per contract for

SymExplainer is

$0.08, compared to

$0.05 for SymGPT. This marginal increase in time and cost is directly attributable to the deeper integration of the LLM across multiple stages of

SymExplainer. Specifically, the multi-stage prompting for semantic extraction, the context-aware guidance of symbolic execution, and particularly the robust secondary verification and detailed interpretability report generation all involve additional, complex LLM interactions.

Despite the slightly higher operational overhead, these costs are justified by the significant gains in detection accuracy (zero false negatives and drastically reduced false positives) and the unparalleled interpretability. For critical applications like smart contract auditing, the value of precision, reliability, and actionable explanations far outweighs the modest increase in processing time and monetary expense. The enhanced trust and reduced manual remediation effort that SymExplainer provides offer substantial long-term benefits and cost savings by preventing costly vulnerabilities.

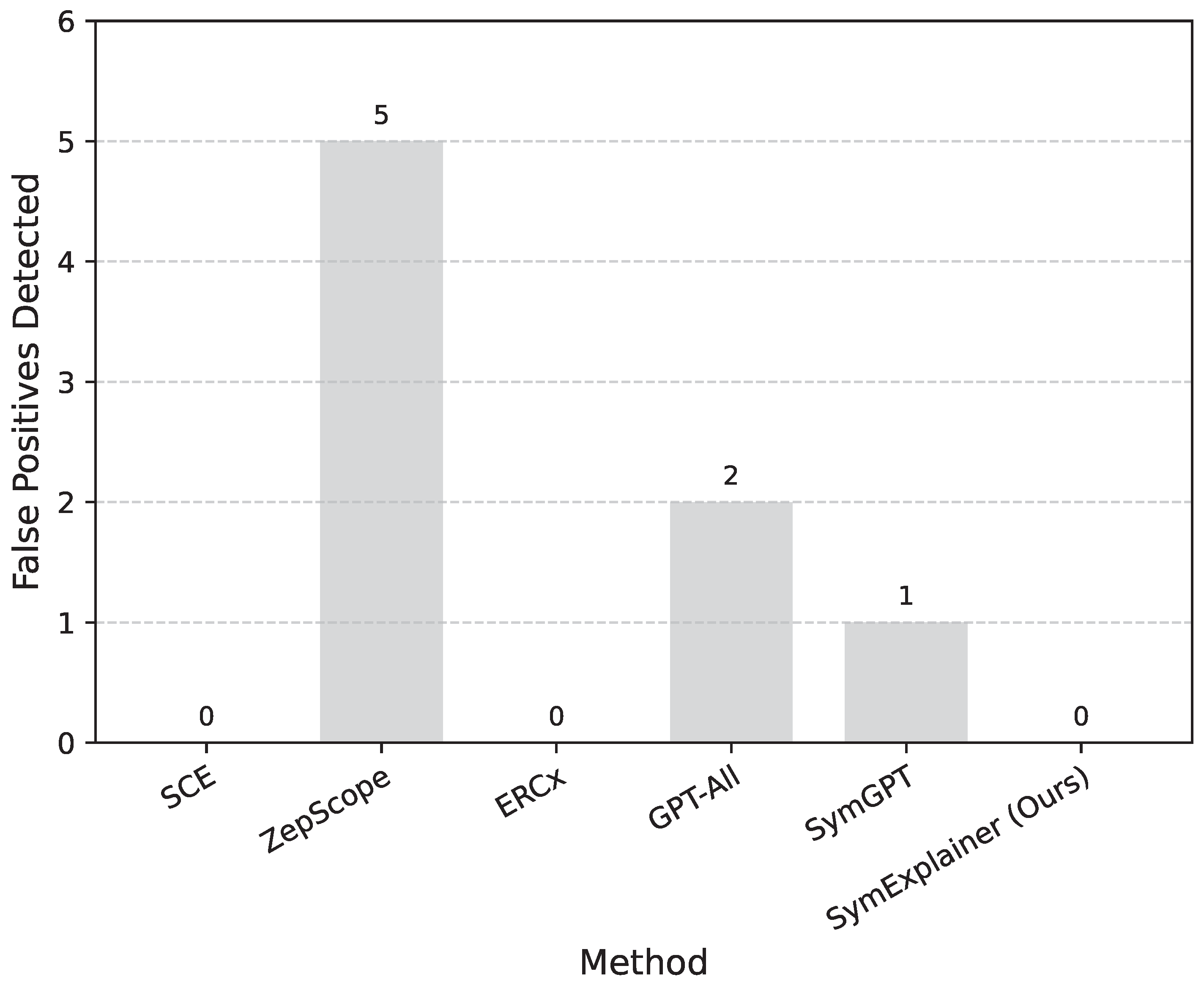

4.6. Generalization and Specificity Evaluation

To assess

SymExplainer’s specificity and generalization ability, we evaluated its performance on a

Generalization Dataset consisting of 10 contracts that are explicitly

non-ERC-compliant or implement non-ERC standards. The primary goal was to determine if the framework would erroneously flag non-ERC specific code patterns as violations, thereby generating false positives outside its intended scope.

Figure 4 presents the results of this evaluation.

Results Analysis: As shown in

Figure 4,

SymExplainer successfully analyzed all 10 non-ERC contracts without detecting a single false positive. This result indicates excellent specificity, demonstrating that our framework precisely targets ERC standard compliance and does not over-flag or misinterpret code patterns outside its defined scope. This performance is on par with specialized static analyzers like SCE and ERCx, which inherently have narrow rule sets. In contrast, some LLM-based approaches, such as GPT-All and SymGPT, and even a broader symbolic tool like ZepScope, exhibited a tendency to produce false positives on non-ERC contracts. This highlights a common challenge for general-purpose tools or LLMs when dealing with highly specific compliance checks.

The robust specificity of SymExplainer can be attributed to the nuanced design of its LLM-Enhanced Rule Semantic Extraction Module, which is precisely engineered to understand ERC documentation, and crucially, the secondary verification module. The LLM’s deep understanding of ERC standards allows it to discern between general code vulnerabilities and specific ERC non-compliance. Furthermore, the final verification step acts as a powerful filter, ensuring that only findings directly related to ERC standards, as formally understood, are reported. This prevents the tool from becoming overly verbose or generating irrelevant alerts, thereby increasing developer trust and minimizing analysis fatigue when applied to diverse smart contract landscapes.

4.7. Human Evaluation of Interpretability Quality

Beyond quantitative detection accuracy, a core contribution of

SymExplainer is its ability to provide high-quality, actionable explanations for detected ERC violations. To assess this, we conducted a qualitative human evaluation using a panel of five expert smart contract developers. They were presented with 30 randomly selected violations detected by

SymExplainer (10 High, 10 Medium, 10 Low impact) and corresponding output from SymGPT for comparison, where applicable. Experts rated the interpretability reports on a Likert scale (1-5, where 5 is excellent) across several dimensions. The average scores are presented in

Table 3.

Results Analysis: The human evaluation results clearly indicate that SymExplainer’s interpretability reports are significantly preferred and deemed more effective by expert developers compared to the interpretability features (or lack thereof) in SymGPT. Specifically, SymExplainer achieved average scores of 4.7 for "Clarity of Explanation" and 4.8 for "Accuracy of Explanation", substantially higher than SymGPT’s 3.5 and 3.8, respectively. Experts praised the natural language explanations for precisely articulating "why" a violation occurred, including the sequence of events and state changes. The "Usefulness of Fix Suggestions" saw the most significant improvement, with SymExplainer scoring 4.5 compared to SymGPT’s 3.2, highlighting the value of generating actionable advice. While SymGPT offered decent code localization (3.9), SymExplainer further refined this to 4.6, ensuring developers can quickly navigate to the exact line and function of concern. The overall satisfaction score of 4.7 for SymExplainer versus 3.6 for SymGPT confirms that our framework delivers a more user-friendly and practical experience, effectively bridging the gap between automated detection and developer actionability. This qualitative assessment underscores SymExplainer’s successful integration of advanced LLM capabilities not just for detection, but crucially, for making security findings transparent and actionable, thereby significantly improving the smart contract development and auditing workflow.

5. Conclusion

Smart contracts demand robust security due to their immutability and the potential for irreversible financial losses from vulnerabilities. Prior automated tools struggled with high false positives/negatives and lacked actionable explanations. This paper introduces SymExplainer, an innovative framework for highly accurate and interpretable ERC violation detection. SymExplainer synergistically combines advanced Large Language Models (LLMs) with refined symbolic execution, guided by multi-level semantic understanding and a unique verification mechanism. It comprises an LLM-Enhanced Rule Semantic Extraction Module, a Context-Aware Symbolic Execution Engine, and a Violation Verification and Interpretability Generation Module. Our extensive evaluation demonstrated its superior performance, achieving perfect recall with zero false negatives and significantly reduced false positives compared to leading methods. Human experts further validated the high quality and practical usefulness of its detailed, natural language interpretability reports. While incurring slightly higher computational costs, these are justified by profound gains in accuracy, reliability, and actionable insights. SymExplainer thus sets a new benchmark, enhancing automated smart contract auditing and fostering a more secure blockchain ecosystem.

References

- Feng, S.; Park, C.Y.; Liu, Y.; Tsvetkov, Y. From Pretraining Data to Language Models to Downstream Tasks: Tracking the Trails of Political Biases Leading to Unfair NLP Models. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 61st Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers). Association for Computational Linguistics, 2023, pp. 11737–11762. [CrossRef]

- Shen, W.; Wu, S.; Yang, Y.; Quan, X. Directed Acyclic Graph Network for Conversational Emotion Recognition. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 59th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics and the 11th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing (Volume 1: Long Papers). Association for Computational Linguistics, 2021, pp. 1551–1560. [CrossRef]

- Blodgett, S.L.; Lopez, G.; Olteanu, A.; Sim, R.; Wallach, H. Stereotyping Norwegian Salmon: An Inventory of Pitfalls in Fairness Benchmark Datasets. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 59th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics and the 11th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing (Volume 1: Long Papers). Association for Computational Linguistics, 2021, pp. 1004–1015. [CrossRef]

- Lu, P.; Gong, R.; Jiang, S.; Qiu, L.; Huang, S.; Liang, X.; Zhu, S.C. Inter-GPS: Interpretable Geometry Problem Solving with Formal Language and Symbolic Reasoning. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 59th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics and the 11th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing (Volume 1: Long Papers). Association for Computational Linguistics, 2021, pp. 6774–6786. [CrossRef]

- Xia, S.; He, M.; Shao, S.; Yu, T.; Zhang, Y.; Song, L. SymGPT: Auditing Smart Contracts via Combining Symbolic Execution with Large Language Models. CoRR 2025. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Geng, X.; Shen, T.; Tao, C.; Long, G.; Lou, J.G.; Shen, J. Thread of thought unraveling chaotic contexts. arXiv preprint arXiv:2311.08734 2023.

- Zhou, Y.; Shen, J.; Cheng, Y. Weak to strong generalization for large language models with multi-capabilities. In Proceedings of the The Thirteenth International Conference on Learning Representations, 2025.

- Zhou, Y.; Li, X.; Wang, Q.; Shen, J. Visual In-Context Learning for Large Vision-Language Models. In Proceedings of the Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics, ACL 2024, Bangkok, Thailand and virtual meeting, August 11-16, 2024. Association for Computational Linguistics, 2024, pp. 15890–15902.

- Zhang, F.; Liu, T.; Chen, Z.; Peng, X.; Chen, C.; Hua, X.S.; Luo, X.; Zhao, H. Semi-supervised knowledge transfer across multi-omic single-cell data. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2024, 37, 40861–40891.

- Liu, Y.; Yu, R.; Yin, F.; Zhao, X.; Zhao, W.; Xia, W.; Yang, Y. Learning quality-aware dynamic memory for video object segmentation. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision. Springer, 2022, pp. 468–486.

- Liu, Y.; Bai, S.; Li, G.; Wang, Y.; Tang, Y. Open-vocabulary segmentation with semantic-assisted calibration. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2024, pp. 3491–3500.

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, C.; Wang, Y.; Wang, J.; Yang, Y.; Tang, Y. Universal segmentation at arbitrary granularity with language instruction. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2024, pp. 3459–3469.

- Doogan, C.; Buntine, W. Topic Model or Topic Twaddle? Re-evaluating Semantic Interpretability Measures. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2021 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies. Association for Computational Linguistics, 2021, pp. 3824–3848. [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, W.; Chakraborty, S.; Ray, B.; Chang, K.W. Unified Pre-training for Program Understanding and Generation. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2021 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies. Association for Computational Linguistics, 2021, pp. 2655–2668. [CrossRef]

- Yang, K.; Ji, S.; Zhang, T.; Xie, Q.; Kuang, Z.; Ananiadou, S. Towards Interpretable Mental Health Analysis with Large Language Models. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2023 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing. Association for Computational Linguistics, 2023, pp. 6056–6077. [CrossRef]

- Pan, L.; Albalak, A.; Wang, X.; Wang, W. Logic-LM: Empowering Large Language Models with Symbolic Solvers for Faithful Logical Reasoning. In Proceedings of the Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: EMNLP 2023. Association for Computational Linguistics, 2023, pp. 3806–3824. [CrossRef]

- Dhuliawala, S.; Komeili, M.; Xu, J.; Raileanu, R.; Li, X.; Celikyilmaz, A.; Weston, J. Chain-of-Verification Reduces Hallucination in Large Language Models. In Proceedings of the Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: ACL 2024. Association for Computational Linguistics, 2024, pp. 3563–3578. [CrossRef]

- Hardalov, M.; Arora, A.; Nakov, P.; Augenstein, I. A Survey on Stance Detection for Mis- and Disinformation Identification. In Proceedings of the Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: NAACL 2022. Association for Computational Linguistics, 2022, pp. 1259–1277. [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Tang, F.; Zhao, M.; Zhu, Y. EmoCaps: Emotion Capsule based Model for Conversational Emotion Recognition. In Proceedings of the Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: ACL 2022. Association for Computational Linguistics, 2022, pp. 1610–1618. [CrossRef]

- Tian, Z.; Lin, Z.; Zhao, D.; Zhao, W.; Flynn, D.; Ansari, S.; Wei, C. Evaluating scenario-based decision-making for interactive autonomous driving using rational criteria: A survey. arXiv preprint arXiv:2501.01886 2025.

- Zheng, L.; Tian, Z.; He, Y.; Liu, S.; Chen, H.; Yuan, F.; Peng, Y. Enhanced mean field game for interactive decision-making with varied stylish multi-vehicles. arXiv preprint arXiv:2509.00981 2025.

- Lin, Z.; Tian, Z.; Lan, J.; Zhao, D.; Wei, C. Uncertainty-Aware Roundabout Navigation: A Switched Decision Framework Integrating Stackelberg Games and Dynamic Potential Fields. IEEE Transactions on Vehicular Technology 2025, pp. 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Li, L.; Zhang, Z.; Ren, X.; Sun, X.; He, B. Be Careful about Poisoned Word Embeddings: Exploring the Vulnerability of the Embedding Layers in NLP Models. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2021 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies. Association for Computational Linguistics, 2021, pp. 2048–2058. [CrossRef]

- Qi, F.; Yao, Y.; Xu, S.; Liu, Z.; Sun, M. Turn the Combination Lock: Learnable Textual Backdoor Attacks via Word Substitution. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 59th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics and the 11th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing (Volume 1: Long Papers). Association for Computational Linguistics, 2021, pp. 4873–4883. [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Liu, X.; Chen, Z.; Hong, H.; Tang, J.; Song, D. DeepStruct: Pretraining of Language Models for Structure Prediction. In Proceedings of the Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: ACL 2022. Association for Computational Linguistics, 2022, pp. 803–823. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, W.; Joty, S.; Hoi, S.C. CodeT5: Identifier-aware Unified Pre-trained Encoder-Decoder Models for Code Understanding and Generation. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2021 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing. Association for Computational Linguistics, 2021, pp. 8696–8708. [CrossRef]

- Shin, R.; Van Durme, B. Few-Shot Semantic Parsing with Language Models Trained on Code. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2022 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies. Association for Computational Linguistics, 2022, pp. 5417–5425. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Deng, Y.; Liu, B.; Pan, S.; Bing, L. Sentiment Analysis in the Era of Large Language Models: A Reality Check. In Proceedings of the Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: NAACL 2024. Association for Computational Linguistics, 2024, pp. 3881–3906. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Chen, H.; Zhu, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Lin, Z.; Qiao, Z.; Zheng, Y.; Wu, X. A survey on foundation language models for single-cell biology. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 63rd Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers), 2025, pp. 528–549.

- Zhang, F.; Liu, T.; Zhu, Z.; Wu, H.; Wang, H.; Zhou, D.; Zheng, Y.; Wang, K.; Wu, X.; Heng, P.A. CellVerse: Do Large Language Models Really Understand Cell Biology? arXiv preprint arXiv:2505.07865 2025.

- Malik, V.; Sanjay, R.; Nigam, S.K.; Ghosh, K.; Guha, S.K.; Bhattacharya, A.; Modi, A. ILDC for CJPE: Indian Legal Documents Corpus for Court Judgment Prediction and Explanation. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 59th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics and the 11th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing (Volume 1: Long Papers). Association for Computational Linguistics, 2021, pp. 4046–4062. [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Lin, Z.; Gong, Y.; Jin, A.L.; Zhang, H.; Lin, C.; Jiao, J.; Yiu, S.M.; Duan, N.; Chen, W. AnnoLLM: Making Large Language Models to Be Better Crowdsourced Annotators. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2024 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies (Volume 6: Industry Track). Association for Computational Linguistics, 2024, pp. 165–190. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Chen, M.; Bi, Z.; Liang, X.; Li, L.; Shang, X.; Yin, K.; Tan, C.; Xu, J.; Huang, F.; et al. CBLUE: A Chinese Biomedical Language Understanding Evaluation Benchmark. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 60th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers). Association for Computational Linguistics, 2022, pp. 7888–7915. [CrossRef]

- Dibia.; Victor. LIDA: A Tool for Automatic Generation of Grammar-Agnostic Visualizations and Infographics using Large Language Models. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 61st Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 3: System Demonstrations). Association for Computational Linguistics, 2023, pp. 113–126. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).