1. Introduction

Melanoma is an aggressive form of skin cancer that, despite comprising only a small fraction of skin cancer cases, it accounts for most skin cancer-related deaths [

1]. Advances in early detection and novel therapies (including immune checkpoint inhibitors and targeted agents) have dramatically improved survival outcomes in recent years[

2]. In fact, the overall 5-years relative survival rate for melanoma now approaches 94% (exceeding 99% for localized disease), with a marked improvement in advanced-stage survival since the mid-2000s [

3]. As a result, an expanding population of melanoma into a chronic condition for years [

4] . In this context, survivorship issues such as psychological well-being, social reintegration, and sexual health have become increasingly important components of comprehensive melanoma care.

Sexual health is a fundamental aspect of HRQoL that is often adversely affected by cancer and its treatment, yet it remains frequently overlooked in oncology practice [

5]. Like other cancers, melanoma can affect sexual functioning through physical, hormonal, and psychological pathways. Surgical excisions may result in disfigurement and body image and self-esteem concerns, while systemic therapies can cause fatigue, neuropathy, and endocrine changes. These factors, alongside emotional distress and fear of recurrence, can significantly reduce sexual desire and satisfaction [

5]. Moreover, the advent of immunotherapies and targeted therapies in advanced melanoma, while extending survival, has introduced new chronic side effects that impact sexual health, such as hormonal changes in both men and women can manifest as decreased libido, erectile dysfunction, vaginal dryness, or infertility

1,2. Notably, immune checkpoint inhibitor treatment has been linked to endocrine dysfunctions such as hypophysitis, leading to hypogonadism in a subset of patients

3. Emotional factors are equally significant: patients with melanoma often experience anxiety, depression, and fear of recurrence, which can suppress sexual desire and strain partner relationships [

6]. Importantly, these sexual difficulties are not confined to those with late-stage disease- even early-stage melanoma survivors (especially older adults and those with visible treatment scars) have reported challenges in sexual function and satisfaction [

7]. Taken together, these issues illustrate that sexual health should be recognized as a relevant domain in the holistic care of melanoma patients [

8].

Major cancer organizations and guidelines advocate routine assessment of sexual health as part of survivorship planning [

9]. In practice, however, discussions about sexuality between patients and providers remain infrequent [

10]. Studies across cancer populations have revealed that while most patients experience some degree of treatment-related sexual dysfunction, most are never offered information or support on this topic by their healthcare team [

11]. For instance, one survey found that approximately 87% of cancer patients reported an adverse impact of treatment on their sexual life, yet only ~28% had ever been asked about sexual health by clinicians [

11]. This disconnects highlights pattern of underreporting and under-recognition of sexual concerns. Patients often hesitate to voice sexual difficulties due to embarrassment from the perception that the topic is “taboo”, whereas providers cite barriers such as limited time, insufficient training, and uncertainty about whose role it is to initiate the conversation [

12]. In melanoma care, where attention historically centered on acute treatment outcomes, the integration of sexual health counseling and interventions is only beginning to gain traction [

13].

A scoping review is warranted to thoroughly map the current knowledge on sexual issues in melanoma and to identify gaps in practice and research. Unlike in some other malignancies (e.g. breast or genitourinary cancers) where sexual side effects are well documented and management guidelines have evolved; there is a dearth of consolidated evidence regarding sexual function in melanoma patients. Preliminary studies suggested that melanoma survivors may indeed suffer significant sexual dysfunction and related distress, but no standardized approaches for prevention or management have been established. By conducting a scoping review, we aim to elucidate the extent, range, and nature of literature on this topic-spanning qualitative reports of patient experiences, quantitative studies of sexual outcomes, and any described intervention or clinical guidelines. This exploration will help clarify what is known and what is missing, thereby guiding future research and informing clinicians about best practices for managing sexual issues in melanoma patients.

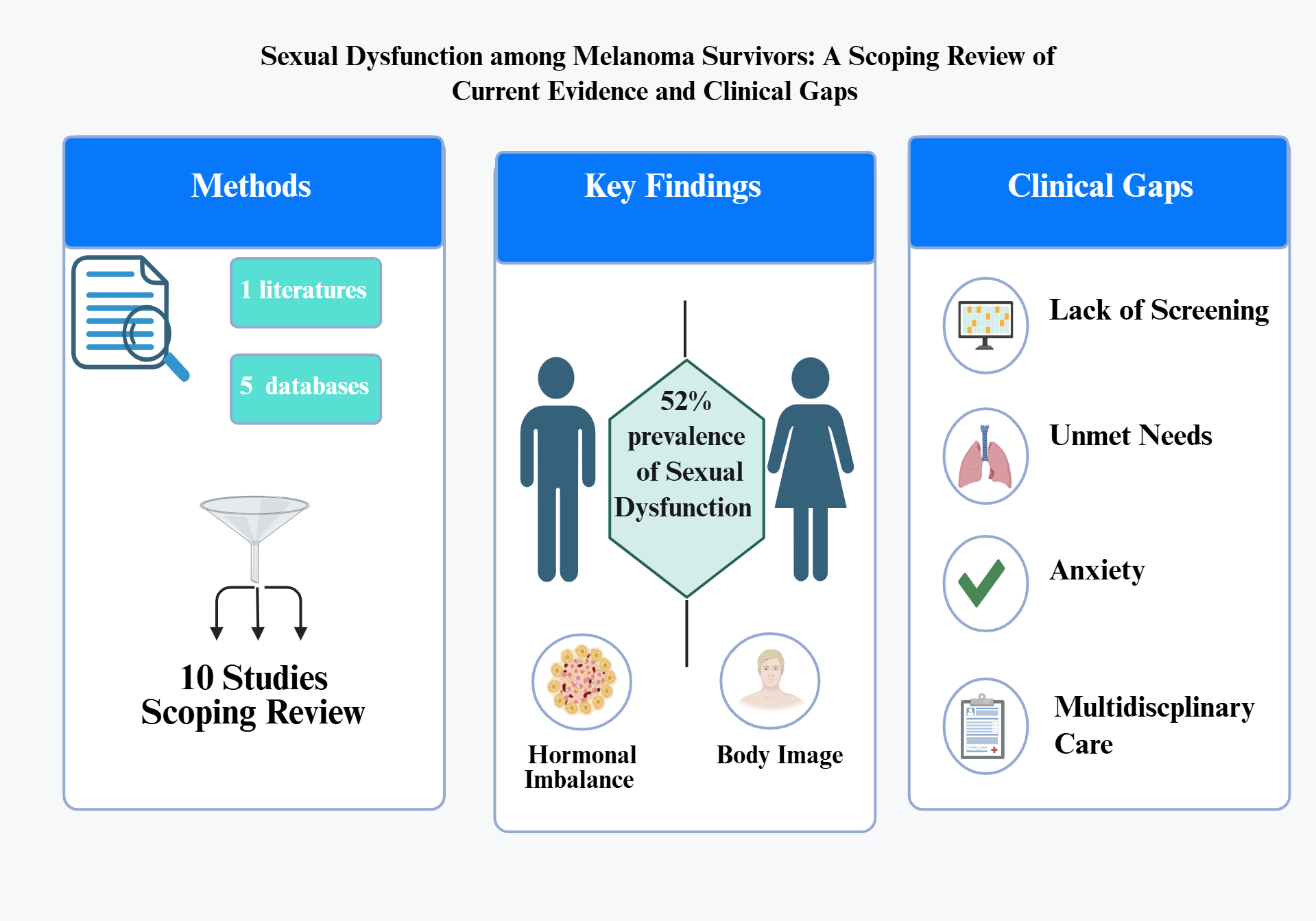

2. Materials and Methods

This scoping review followed the methodological framework outlined by Arksey and O’Malley

4 and further refined by Levac et al.

5, adhering to preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analysis extension for scoping review (PRISMA-ScR) guidelines

6. The review protocol was developed a priori to comprehensively map the existing literature on sexual health issues in melanoma patients and identify key concepts, research gaps, and opportunities for future investigation.

2.1. Research Question

This scoping review was guided by following research question: ‘what is the current state of knowledge regarding sexual health issues in melanoma patients, and how are these issues being addressed or managed in the existing literature and clinical practices?’ The question was structured using the population-concept-context (PCC) framework, in which the population included melanoma patients and survivors of all stages; the concept encompassed sexual health issues, dysfunction, and related interventions; and the context referred to oncological care settings and survivorship programs.

2.2. Eligibility Criteria (Table 1)

2.3. Search Strategy

Systematic research was carried out in five electronic databases: Scopus, Medline, PubMed, ScienceDirect and Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), covering the period from 2010 through 2025

7,8. The search strategy combined controlled vocabulary (e.g., MeSH terms) and free- text key words related to three core concepts: Melanoma (“melanoma,” “ malignant melanoma,” “cutaneous melanoma,” “skin neoplasms”) ; sexual health (“sexual health,” “ sexual function,” “ sexual dysfunction,” “ sexuality,” “body image”; and cancer context (“neoplasms”, “cancer survivors”, “ survivorship”, “oncology” ). These terms were adapted for each database and combined using Boolean operators (AND, OR) and truncation symbols where appropriate.

Two reviewers (OA and SA) independently screened all titles and abstract for relevance, and full text were obtained for potentially eligible studies. The same two reviewers then independently assessed full text articles against the inclusion criteria, with any discrepancies resolved by discussion. Data from included studies were extracted in duplicate by OA and SA using a standardized charting form; discrepancies were resolved by consensus.

2.4. Quality Appraisal (JBI)

Each study was evaluated independently by two reviewers using critical appraisal checklists tailored to the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) design. Informed by the interpretation of study findings, items were rated YES/NO/UNCLEAR and classified as high (7–10), moderate (4-6), or low (≤3). The focus was on combining data from better studies to support the review's findings. Although they were carefully weighed up, studies that were judged to be of low quality provided contextual understanding. Study-level quality scores are displayed in supplementary materials.

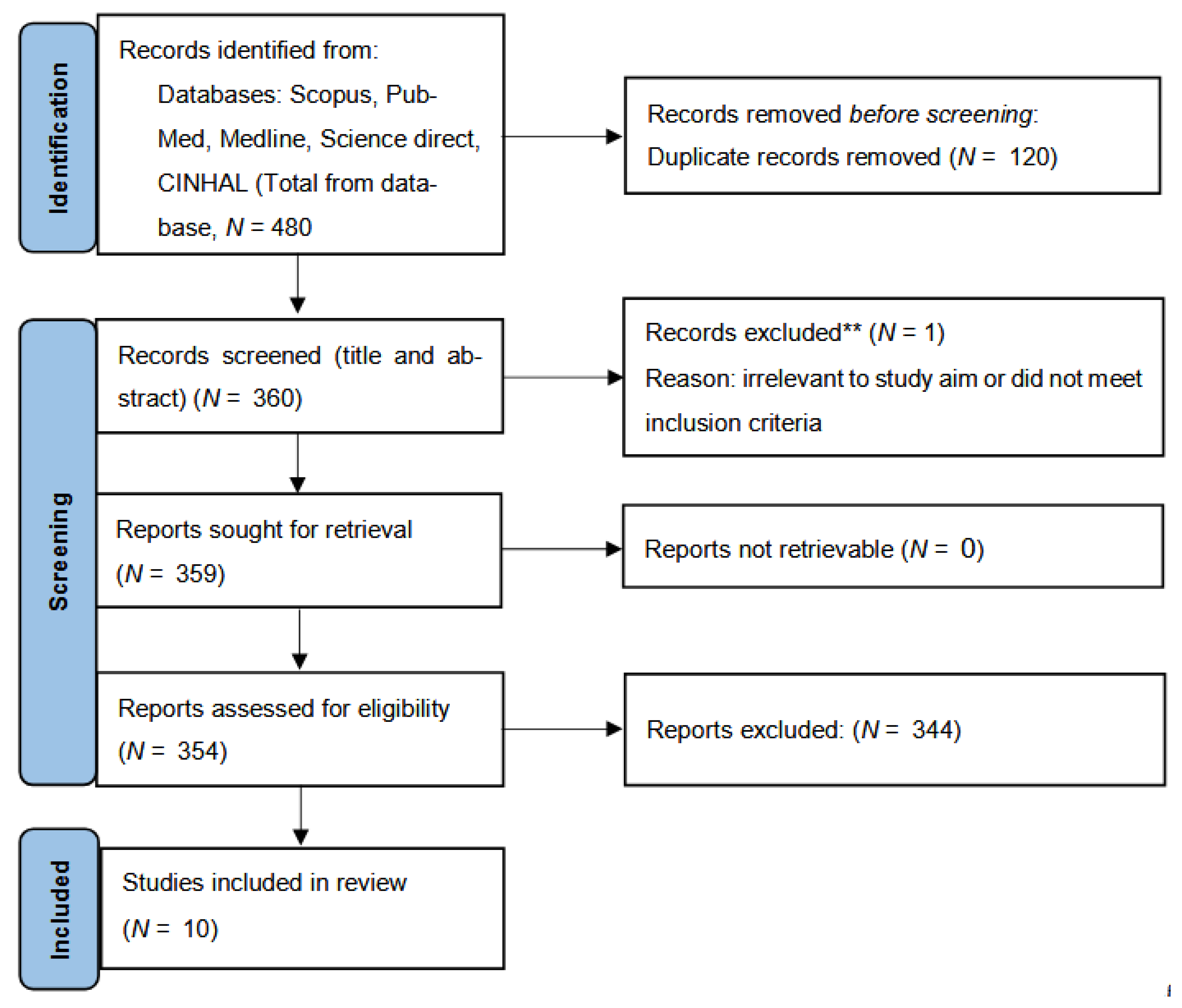

Following PRISMA-ScR recommendation, the study selection process is summarized in

Figure 1. A total of 480 records were retrieved through database searching (Scopus, PubMed midline, ScienceDirect, and CINHAL). After removing 120 duplicates, 360 records remined for title/abstract screening. Of these, 344 were excluded for irrelevance, leaving 16 full-text articles assessed for eligibility. Following full-text evaluation, 10 studies met all inclusion criteria and were included in the final review.

2.5. Data Extraction

From the 10 studies that were included in the final literature review, the following data were abstracted and inserted into

Table 2: author and year of publication, purpose of study, country, sample size, design, and main findings.

3. Results

The systematic search identified 10 studies that met the inclusion criteria for this scoping review on sexual health issues in melanoma patients. The included studies represented diverse geographical locations, with research conducted in Spain, Italy, Germany, Portugal and the United States, and. The study designs varied considerably, encompassing cross sectional studies, systematic reviews, qualitative research, prospective cohort studies, and narrative reviews. The sample sizes ranged from 22 participants in qualitative studies to large-scale analyses involving over 2,000 patients.

3.1. Study Characteristics and Populations

Most studies (n=

7) [

5,

15,

17,

19,

20,

21,

22] employed quantitative methodologies, while one utilized qualitative [

16] approach and two were review studies [

14,

18]. Study populations predominantly consisted of adult melanoma patients across various disease stages, with some studies specifically focusing on advanced melanoma patients [

16], or long-term survivors [

17,

19]. Sample demographics varied, with several studies reporting female predominance in their cohorts, particularly among survivorship studies [

17,

19].

3.2. Prevalence of Sexual Dysfunction in Melanoma Patients

Sexual dysfunction emerged as a significant concern among melanoma patients, with prevalence rates varying across studies. The most comprehensive assessment was conducted by Munoz-barba (2025), who reported an overall sexual dysfunction prevalence of 52% among 75 melanoma patients in Spain [

5]. Notably, 29.3% of participants reported a direct negative impact of melanoma on their sexual function, with decrease sexual desire being the most frequently reported issue.

In a broader cancer survivorship context, Heyne (2023) found that nearly half of long-term cancer survivors, including melanoma patients, reported reduced sexual satisfaction compared to their pre-diagnosis level [

17]]. This finding was consistent across both 5-years and 10-years survivor cohorts, indicating the persistent nature of sexual health challenges following melanoma treatment.

Table 3 summarized key prevalence estimates. Several melanoma cohorts also identified psychosocial correlates: for example, mood disturbance (anxiety/depression) and poorer quality of life were consistently linked to sexual dysfunction. One Italian cross-sectional study noted that nearly 30% of melanoma patients explicitly attributed sexual difficulties to their cancer, primarily reduced desire (54.5% of affected patients) and postoperative discomfort.

3.3. Gender-Specific Differences in Sexual Health Outcomes

Gender disparities were evident throughout literature. Munoz-barba (2025) demonstrated that 68.9% of men and 41.3% of women experienced sexual dysfunction [

5]. Multiple studies identified important gender differences in sexual health experiences among melanoma patients. Women were more likely than men to report changes in appearance and fear of recurrences or developing a second melanoma. However, they also demonstrated a greater likelihood of reporting positive impacts from their melanoma experiences [

19]. Queirolo (2025) conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis demonstrating that women had significantly higher risks of thyroid-related adverse events and dermatological complication with targeted therapy, which could indirectly impact sexual health through body image concerns and hormonal disruptions [

14].

Men showed distinct patterns of sexual health impairment. The narrative review by Cosci (2023) highlighted that men generally have higher melanoma incidence, progression rates, and mortality compared to women [

18]. Furthermore, this review emphasized that immune checkpoint inhibitors may adversely affect male fertility and testicular function, leading to recommendations for sperm cryopreserved in men undergoing such therapies.

3.4. Hormonal Effects

Peters (2021) focused specifically on male melanoma patients undergoing immunotherapy and identified testosterone deficiency in 69% of participants [

20]. This hormonal disruption was frequently associated with fatigue and sexual dysfunction, yet few patients received appropriate testosterone replacement therapy, highlighting significant gaps in clinical recognition and management. Hypophysitis with subsequent hypopituitarism occurred primarily with ipilimumab treatment, with obesity and participation in clinical trials increasing the risk of testosterone deficiency.

Figure 2. Hormonal pathway of sexual dysfunction in male melanoma patients receiving immunotherapy. Ipilimumab treatment induces Hypophysitis (Pituitary inflammation), leading to decreased testosterone production and subsequent erectile dysfunction. This pathway affects approximately 69% of men undergoing immunotherapy.

Heyne (2023) demonstrated that physical symptom burden had a stronger impact on sexual satisfaction than psychosocial factors among cancer survivors [

17]. Factors independently associated with higher sexual satisfaction included female gender, absences of hormone therapy, lower comorbidity burden, reduced fatigue, and better emotional and social functioning.

3.5. Body Image and Psychosocial

Body image concerns emerged as a central theme affecting sexual health in melanoma patients. Carli (2024) conducted qualitative study with 22 interviewed advanced melanoma patients and identified significant negative impacts on body image, including feelings of estrangement from their bodies, concerns about visible scars, and fear of body exposure [

16]. These findings were supported by patients experiencing isolation and reduced social support during treatment, despite having access to medical and family support systems.

Craca Pereira (2017) provided empirical evidence for the mediating role of body image in the relationship between illness perceptions and quality of life among 106 patients with skin tumor [

22]. Their analysis demonstrated that body image concerns the mediated relationship between illness perceptions, family stress, psychological morbidity, and overall quality of life. Additionally, social support was found to mediate the relationship between family stress, psychological morbidity, and quality of life, underscoring the interconnected nature of psychosocial factors in sexual health outcomes.

As previously noted in the gender differences sections, Vogel (2021) found that female were more likely than males to report changes in appearance [

19], reinforcing the particular vulnerability of women to body image-related sexual health concerns in melanoma survivorship. An example is a lady with advanced cutaneous melanoma lesion located in the posterior auricular region which would result in visible disfigurement and scarring that contribute to body image disturbances and related sexual health concerns postoperatively.

3.6. Treatment-Related Issues

Several studies identified specific treatment-related factors contributing to sexual dysfunction in melanoma patients. Peters (2021) found that hypophysitis and hypopituitarism occurred primarily with ipilimumab treatment, with obesity and participation in clinical trials increasing the risk of testosterone deficiency [

20]. The high prevalence of unrecognized and untreated testosterone deficiency highlighted significant gaps in clinical care.

The relationship between melanoma diagnosis and emotional well-being significantly influenced sexual health outcomes. Sampogna (2019) compared quality of life melanoma and non-melanoma skin cancer patients and found that melanoma patients reported significantly more emotional distress, particularly feelings of depression [

21]. While non-melanoma skin cancer patients experienced higher symptoms scores indicating greater physical burden, melanoma patients demonstrated greater psychological and emotional quality of life impairment.

4. Discussion

4.1. Research Gaps and Methodological Considerations

The reviewed studies revealed significant gaps in current research on sexual health in melanoma patients. Most studies were cross-sectional in design, limiting understanding of temporal relationships and changes in sexual function over time. Additionally, several studies included mixed cancer populations or focused on general quality of life measures without specific sexual health assessments, making it difficult to isolate melanoma-specific sexual health issues.

The geographics distribution of research was limited, with most studies conducted in European countries and the United States, potentially limiting generalizability to other populations. Furthermore, intervention studies addressing sexual health issues in melanoma patients were notably absent from the literature, indicating a significant gap in evidence-based management strategies. The findings of this scoping review are consistent with the broader consensus in psycho-oncology literature regarding cancer and sexual health. In contrast to melanoma highly visible skin changes, many other cancers also result in internal or concealable alterations. For example, breast cancer treatments often cause physiological and body image changes (like mastectomy, chemotherapy-induced menopause, or hair loss), but these can usually be hidden under clothing or by prosthesis. In psycho-oncology studies of breast cancer, sexual problems are linked not only to physical effects (e.g. vaginal dryness or hormonal changes) but also to body-image distress and relational strain [

23] . Similarly, genitourinary caners (e.g. prostate cancer) typically disrupt sexual function through internal mechanisms (nerve damage, hypogonadism, hormonal therapy) rather than through visible disfigurement. In men with prostate cancer, for instance, treatment like radical prostatectomy often lead to erectile dysfunction and a threatened sense of masculinity- “feeling as if they had lost a bit of their manhood” – even though no external changes are apparent [

24]. What sets melanoma apart is the external, visible scarring and pigmentation on exposed skin, which can exacerbate body image concerns and stigma. Carli (2024). note that “due to its visibility and scaring outcomes, melanoma often results in impaired body image”[

16]. Munoz-barba (2025). also found that melanoma survivors’ sexual dysfunction was strongly associated with location of visible scar postoperatively [

5]. Pereira. emphasize that body image disturbances are central to melanoma patients’ quality of life, arguing that psychological care should explicitly target these visible changes [

22]. In short, while sexual health issues in other cancers often stem from internal or surgically concealed changes and their hormonal/relational sequalae [

23,

24], melanoma adds the extra burden of conspicuous skin scars and pigment changes that heighten

the stigma and body-image distress [

5,

16]. These differences underscore why melanoma patients may experience unique challenges in sexuality and self-esteem that merit tailored psychological support [

16,

22]. Clinical implications: given that more than half of melanoma patients report some sexual dysfunction [

5], oncologists and dermatologists should incorporate routine sexual-health screening into care. A multidisciplinary team (including mental-health and endocrine specialists [

5]) can then address the full spectrum of issues-from hormonal side effects to the psychological impact of visible differences) may help mitigate the stigma and distress unique to melanoma survivors [

16,

22]. Likewise, awareness that female patients often worry about appearance (and that men on immunotherapy may develop hypogonadism) can guide gender-sensitive support strategies. Overall, these findings echo broader psycho-oncology evidence that cancer care must go beyond survival to improve patients quality of life [

22,

23]. Regarding the role and recommendations for improving sexuality care for patients, our previous work provides detailed methods, including structured notes, role-play workshops, and a proactive approach to breaking the silence.

9,10

4.2. Limitation of Current Evidence

Although recent studies have generated valuable insights that may inform clinical guidelines, several methodological shortcomings must be acknowledged. Most investigations to date employ cross sectional designs, which preclude the establishment of casual relationships between risk factors and sexual dysfunction. Furthermore, the predominant reliance on self-reported questionnaires introduces subjectively, with findings vulnerable to recall bias and social desirability effects-particularly salient given the stigma surrounding sexual health. These methodological constraints limit both the internal validity and generalizability of current evidence.

4.3. Directions for Future Research

To strengthen the evidence base, future studies should adopt longitudinal designs to clarify temporal associations and better delineate causal pathways. In addition, interventional research is critically needed to address the paucity of evidence regarding effective management strategies. Such trials should evaluate the impact of targeted psychosocial, pharmacologic, and rehabilitative interventions on sexual health outcomes. Importantly, standardized assessments of sexual function should be incorporated routinely into melanoma clinical trials, particularly those involving immunotherapies, where endocrine toxicities may impair sexual functions. Collectively, these strategies will advance a more robust and clinically actionable understanding of sexual dysfunction in melanoma populations.

5. Conclusions

This scoping review provides a comprehensive synthesis of the existing literature on sexual health issues in melanoma patients. The compilation of existing research shows that sexual health has been continuously underrepresented in melanoma research and practice, despite the fact that quality of life, psychological wellbeing, and coping mechanisms have all gotten a lot of attention. Intimate relationship issues, diminished self-esteem, and changes in body image are common complaints from patients. There is a significant gap in holistic patient care because these issues are rarely addressed in clinical interactions, despite their significant influence on wellbeing. Our knowledge of how melanoma and its treatments impact sexual functioning over time is further limited by the dearth of intervention studies, the literature's lack of cultural diversity, and the absence of longitudinal data. Increased clinical awareness, systematic screening for sexual health needs, and the creation of patient-centered, evidence-based interventions are all necessary to close these gaps. Future studies ought to give special attention to cross-cultural viewpoints, incorporate patient and partner voices, and assess the efficacy of educational and supportive initiatives aimed at enhancing sexual wellbeing. It is not only possible, but also essential, to incorporate sexual health into standard melanoma care in order to guarantee thorough, considerate, and genuinely patient-centered cancer care. We recommend that future clinical guidelines integrate standardized sexual health assessments into routine melanoma care pathways and that clinicians receive targeted training on initiating conversations about sexuality with patients.

Supplementary Materials

The critical appraisal table as Table S1.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.T. and O.A.; methodology, P.T. and O.A.; software, O.A.; validation, A.A. and O.A.; formal analysis, O.A.; investigation, O.A.; resources, P.T. and K.J.; data curation, O.A.; writing—original draft preparation, O.A.; writing—review and editing, O.A.; P.T. and L.S.; supervision, P.T. and K.J.; project administration, P.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created and all used references are listed in this manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

|

ADOREG – Arbeit gemeinschaft Dermatologist Oncology Registry |

|

AEs – adverse events |

|

BRAF – Rapidly Accelerated Fibrosarcoma B-type |

|

DLQI – Dermatology Life Quality Index |

|

EORTC QLQ-C30 – European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of life Questionnaire - Core 30 |

|

FSFI – Female Sexual Function Index |

|

GAD-7 – general anxiety disorder - 7 items |

|

HADS – The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale |

|

HRQoL – health-related quality of life |

|

ICI – immune checkpoint inhibition |

|

IIEF – International Index of Erectile Function |

|

JBI – Joanna Briggs Institute |

|

MeSH terms – Medical Subject Headings terms |

|

MEK – Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase |

|

N/A – Not Available |

|

NMSC – non-melanoma skin cancers |

|

NRS – Numeric Rating Scale |

|

PCC – population-concept-context |

|

PD-1 – programmed cell death protein 1 |

|

PHQ-9 – Patient Health Questionnaire - 9 items |

|

PRISMA – Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses |

|

PRISMA-ScR – Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis extension for scoping review |

|

QoL – quality of life |

|

SD – sexual dysfunction |

|

TT – targeted therapy |

Notes

| 1 |

Kasparian NA, McLoone JK, Butow PN. Psychological responses and coping strategies among patients with malignant melanoma: a systematic review of the literature. Archives of dermatology, 2009. 145(12): p. 1415-1427. |

| 2 |

Saw RPM, Bartula I, Winstanley JB, Morton, RL, Dieng M, Lai-Kwon J, Thompson J, Mostafa N, et al. Melanoma and quality of life, in Handbook of Quality of Life in Cancer. 2022, Springer. p. 439-466. |

| 3 |

Camejo N, Montenegro C, Amarillo D, Castillo C, Krygier G. Addressing sexual health in oncology: perspectives and challenges for better care at a national level. ecancermedicalscience, 2024. 18: p. 1765. |

| 4 |

|

| 5 |

|

| 6 |

Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O'Brien KK, Colquhoun H, Levac D, Moher D, Peters MDJ, Horsley T, Weeks L, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(7):467–73. doi:10.7326/M18-0850. Available from: https://www.acpjournals.org/doi/10.7326/M18-0850

|

| 7 |

Bulechek GM, Butcher HK, Dochterman JM, Wagner CM. Nursing Interventions Classification (NIC). 7th ed. St. Louis: Elsevier; 2022. |

| 8 |

|

| 9 |

Alqaisi O, Subih M, Joseph K, Yu E, Tai P. Oncology nurses' attitudes, knowledge, and practices in providing sexuality care to cancer patients: a scoping review. Curr Oncol 2025;32(6):337-46. |

| 10 |

Alqaisi O, Al-Ghabeesh S, Tai P, Wong K, Joseph K, Yu E. A narrative review of nursing roles in addressing sexual dysfunction in oncology patients. Curr Oncol. 2025;32(8):457-75. |

References

- Roky, A.H.; et al. Overview of skin cancer types and prevalence rates across continents. Cancer pathogenesis and therapy 2025, 3, 89–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, M.; et al. Advances in cancer immunotherapy: historical perspectives, current developments, and future directions. Molecular Cancer 2025, 24, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marquez-Rodas, I.; et al. Immune checkpoint inhibitors: therapeutic advances in melanoma. Annals of translational medicine 2015, 3, 267. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Schadendorf, D.; et al. Melanoma. Nature reviews Disease primers 2015, 1, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muñoz-Barba, D.; et al. Sexual Dysfunction in Melanoma Survivors: A Cross-Sectional Study on Prevalence and Associated Factors. Journal of Clinical Medicine 2025, 14, 4891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kasparian, N.A.; McLoone, J.K.; Butow, P.N. Psychological responses and coping strategies among patients with malignant melanoma: a systematic review of the literature. Archives of dermatology 2009, 145, 1415–1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saw, R.P.; et al. Melanoma and quality of life. In Handbook of Quality of Life in Cancer; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022; pp. 439–466. [Google Scholar]

- Camejo, N.; et al. Addressing sexual health in oncology: perspectives and challenges for better care at a national level. ecancermedicalscience 2024, 18, 1765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanft, T.; et al. NCCN Guidelines® Insights: Survivorship, Version 2.2025: Featured Updates to the NCCN Guidelines®. Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network 2025, 23, 208–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haboubi, N.; Lincoln, N. Views of health professionals on discussing sexual issues with patients. Disability and rehabilitation 2003, 25, 291–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katz, A., L.S. Agrawal, and B. Sirohi. Sexuality After Cancer as an Unmet Need: Addressing Disparities, Achieving Equality. in American Society of Clinical Oncology Educational book. American Society of Clinical Oncology. Annual Meeting. 2022.

- Krouwel, E.; et al. Discussing sexual health in the medical oncologist’s practice: exploring current practice and challenges. Journal of Cancer Education 2020, 35, 1072–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amarsi, A.; et al. Bridging gaps throughout a patient’s journey with melanoma: A systematic review. medRxiv 2025, 2025.05. 13.25327522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Queirolo, P.; et al. Sex and gender influence on adverse events for melanoma patients: A comprehensive review and meta-analysis. 2025, American Society of Clinical Oncology.

- Leven, A.-S.; et al. Sex-specific survival in advanced metastatic melanoma–a DeCOG study on 2032 patients of the multicenter prospective skin cancer registry ADOREG. European Journal of Cancer 2025, 115668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carli, B.; et al. The Impact of Advanced Melanoma on the Relational Sphere, Body and Quality of Life: A Phenomenological-Hermeneutic Study. 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Heyne, S.; et al. Physical and psychosocial factors associated with sexual satisfaction in long-term cancer survivors 5 and 10 years after diagnosis. Scientific reports 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cosci, I.; et al. Cutaneous melanoma and hormones: focus on sex differences and the testis. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2022, 24, 599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vogel, R.I.; et al. Cross-sectional study of sex differences in psychosocial quality of life of long-term melanoma survivors. Supportive Care in Cancer 2021, 29, 5663–5671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peters, M., et al., Testosterone deficiency in men receiving immunotherapy for malignant melanoma. Oncotarget. 2021, 12, 199–208. A novel study assessing the association between immunotherapy and testosterone deficiency.) Article PubMed PubMed Central.

- Sampogna, F.; et al. Comparison of quality of life between melanoma and non-melanoma skin cancer patients. European Journal of Dermatology 2019, 29, 185–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pereira, M.G.; et al. Quality of life in patients with skin tumors: the mediator role of body image and social support. Psycho-oncology 2017, 26, 815–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fobair, P.; et al. Body image and sexual problems in young women with breast cancer. Psycho-Oncology: Journal of the Psychological, Social and Behavioral Dimensions of Cancer 2006, 15, 579–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bowie, J.; et al. Body image, self-esteem, and sense of masculinity in patients with prostate cancer: a qualitative meta-synthesis. Journal of Cancer Survivorship 2022, 16, 95–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).