1. Introduction

Over the past two decades, emerging market economies have undergone profound financial transformation. Banking systems have been recapitalized, macroprudential frameworks have been institutionalized, and domestic capital markets have expanded in depth and sophistication. In parallel, financial integration has intensified, granting firms and governments greater access to global funding and a broader investor base. Yet despite these structural advances, emerging markets remain persistently vulnerable to global financial shocks. Episodes such as the Global Financial Crisis, the taper tantrum, the COVID-19 market turmoil of March 2020, and the recent cycle of abrupt monetary tightening have repeatedly demonstrated that financial stress originating in core markets continues to transmit rapidly and forcefully to emerging economies.

This persistence of vulnerability poses a fundamental puzzle. Conventional policy narratives suggest that stronger bank regulation, deeper financial markets, and improved institutional frameworks should enhance resilience to external shocks. Indeed, following the Global Financial Crisis, regulatory reforms substantially strengthened the banking sector through higher capital and liquidity requirements, enhanced supervision, and the widespread adoption of macroprudential policy instruments. Many emerging economies, in particular, moved quickly to implement borrower-based measures, countercyclical capital buffers, and prudential limits on foreign-currency exposures, often ahead of advanced economies. At the same time, financial intermediation became more diversified and market-based, reducing reliance on bank balance sheets and, in principle, improving risk sharing.

Nevertheless, the empirical record indicates that these reforms have not delivered the expected insulation from global disturbances. Capital flow reversals, sharp exchange-rate adjustments, sudden asset price corrections, and episodes of market illiquidity remain recurring features of emerging market financial cycles. These dynamics cannot be fully explained by weak domestic fundamentals or by deficiencies in bank balance sheets alone. Instead, they point to deeper structural mechanisms that shape how shocks are transmitted and amplified in contemporary financial systems.

This paper argues that the persistent exposure of emerging markets reflects the interaction of three structural forces that lie largely outside the reach of traditional, bank-centric regulatory frameworks. First, global financial cycles—driven by common factors such as global liquidity conditions, investor risk appetite, and leverage dynamics in major financial centers—continue to dominate domestic financial conditions in open economies. Second, the rapid expansion of non-bank, market-based financial intermediation has shifted the locus of systemic risk toward activities reliant on short-term funding, collateral valuation, and leverage, rather than on bank solvency alone. Third, institutional and regulatory fragmentation has created macro-financial blind spots, limiting the capacity of macroprudential policy to address system-wide vulnerabilities that cut across sectors, instruments, and borders.

The central contribution of this article is to develop an integrated conceptual framework that links these forces into a coherent explanation of why emerging markets remain structurally vulnerable to global shocks. The framework emphasizes funding liquidity, margin dynamics, and market plumbing as the primary channels through which global disturbances are transmitted and amplified, particularly via non-bank financial intermediaries. It further highlights how regulatory boundaries and data gaps weaken the effectiveness of entity-based macroprudential tools, allowing vulnerabilities to accumulate outside the traditional regulatory perimeter.

This paper contributes to the literature by offering an integrated conceptual framework that explains the persistence of emerging market vulnerability through the interaction of global financial cycles, non-bank financial intermediation, and regulatory fragmentation, with particular emphasis on funding liquidity and market-based transmission mechanisms.

By synthesizing insights from the macroprudential literature, research on market liquidity and leverage cycles, and recent evidence on non-bank financial intermediation, this paper advances three related arguments. First, the post-crisis focus on bank resilience, while necessary, is insufficient to ensure system-wide stability in financial systems increasingly dominated by market-based finance. Second, the transmission of global shocks to emerging markets operates primarily through funding and liquidity channels that are weakly constrained by existing regulatory frameworks. Third, addressing these vulnerabilities requires a shift toward system-wide, activity-based approaches to macro-financial governance, complemented by improved data, cross-agency coordination, and international cooperation.

While the analysis is global in scope, the framework is particularly relevant for emerging market economies, where financial openness and market-based intermediation amplify exposure to external shocks.

This article adopts a conceptual analytical research design based on theory-informed synthesis and institutional evidence. The next section revisits the evolution of macroprudential policy since the Global Financial Crisis and examines the structural limits of bank-centric regulatory frameworks in the presence of financial innovation and regulatory arbitrage. The subsequent section analyzes the rise of non-bank financial intermediation and the mechanisms through which funding liquidity, leverage, and market plumbing generate fragility. The paper then situates these dynamics within the context of global financial cycles and commodity-linked exposures, explaining why emerging markets continue to function as price-takers in global markets. Building on these elements, the final analytical section presents an integrated framework of macro-financial blind spots and derives implications for the design of macro-financial governance in emerging economies. The conclusion summarizes the main findings and outlines directions for future research.

This article adopts a conceptual and analytical research approach. Rather than presenting new empirical estimations, the paper develops an integrative framework grounded in established theoretical contributions on macroprudential policy, market liquidity, leverage cycles, and non-bank financial intermediation, complemented by recent institutional evidence from international financial authorities. The analysis proceeds through critical synthesis of the academic literature and policy reports to identify structural mechanisms underlying the transmission and amplification of global financial shocks in emerging markets. This approach is particularly suitable for examining system-wide vulnerabilities that arise from interactions across institutions, markets, and regulatory boundaries, and for deriving policy-relevant implications in settings where purely bank-centric or country-specific analyses are insufficient.

2. Macroprudential Policy, Financial Cycles, and Structural Limits

The emergence of macroprudential policy as a central pillar of financial regulation represents one of the most significant institutional shifts in the aftermath of the Global Financial Crisis. Its intellectual roots, however, precede the crisis by several decades. Early contributions associated with Minsky’s financial instability hypothesis emphasized that periods of stability breed risk-taking behavior, leverage expansion, and increasingly fragile balance sheets. From this perspective, financial crises are not exogenous accidents but endogenous outcomes of the financial cycle itself. Subsequent formulations, notably those articulated by Crockett at the turn of the millennium, translated these insights into a regulatory problem: safeguarding financial stability requires tools that address systemic risk rather than the soundness of individual institutions in isolation.

Macroprudential regulation was thus conceived as a response to the failure of microprudential supervision to internalize system-wide externalities. While microprudential oversight seeks to ensure that individual institutions remain solvent, macroprudential policy targets the collective dynamics that arise when many institutions respond simultaneously to changes in prices, risk, and funding conditions. The key intuition is that behavior which is rational at the level of the individual institution can be destabilizing when replicated across the system. When intermediaries tighten lending standards, reduce leverage, or hoard liquidity in response to rising uncertainty, their actions reinforce asset price declines and funding stress, amplifying the downturn they seek to avoid.

In institutional terms, this shift translated into a new regulatory architecture following the Global Financial Crisis. Jurisdictions across advanced and emerging economies adopted countercyclical capital buffers, borrower-based measures, dynamic provisioning rules, and stress-testing frameworks explicitly designed to incorporate adverse macro-financial scenarios. These instruments were intended to operate countercyclically: restraining credit expansion and leverage accumulation during booms, while preserving lending capacity during downturns. Empirically, this agenda achieved notable success in strengthening bank balance sheets. By the time of the COVID-19 shock, banks entered the crisis with substantially higher capital and liquidity buffers than in 2008, allowing them to absorb losses without triggering a generalized banking panic.

Despite these achievements, the macroprudential turn has remained structurally bank-centric. This orientation reflected both historical experience and regulatory practicality. Banks were the epicenter of the Global Financial Crisis and remain central to payment systems, credit provision, and monetary policy transmission. Moreover, bank balance sheets are comparatively transparent and amenable to regulation through standardized prudential metrics. As a result, macroprudential authorities naturally concentrated their efforts on banking institutions as the primary locus of systemic risk.

Over time, however, this focus has revealed important limitations. As regulatory constraints on banks tightened, financial intermediation did not contract proportionally; instead, it was reconfigured. Credit provision, liquidity transformation, and leverage increasingly migrated toward capital markets and non-bank financial intermediaries. Investment funds, hedge funds, broker-dealers, and other market-based actors assumed a growing role in financing economic activity, particularly through securities financing transactions, derivatives markets, and short-term wholesale funding. From a system-wide perspective, risk did not disappear—it changed form and location.

This structural reallocation of financial activity exposed a fundamental mismatch between the scope of macroprudential tools and the evolving architecture of financial systems. Traditional macroprudential instruments are designed to operate on balance-sheet quantities—capital ratios, liquidity buffers, and leverage constraints—that are well-defined for banks but difficult to apply uniformly to heterogeneous non-bank intermediaries. Moreover, many of the most destabilizing dynamics in market-based finance originate not at the level of institutions, but at the level of activities. Securities lending, repurchase agreements, derivatives margining, and collateral valuation practices generate procyclical feedback loops that are poorly captured by entity-based regulation.

The literature increasingly characterizes this mismatch as a boundary problem. When regulatory constraints are applied unevenly across institutions and activities, financial intermediation migrates toward less regulated segments of the system. Empirical evidence confirms that macroprudential tightening directed at banks often induces offsetting expansions of credit and leverage outside the regulated perimeter. This phenomenon—commonly described as regulatory leakage—does not merely dilute the effectiveness of macroprudential policy; it can alter the composition of systemic risk in ways that are more difficult to monitor and manage.

The boundary problem is particularly acute in financially open economies with deep capital markets. In such settings, credit intermediation can shift rapidly across institutional forms and national borders, undermining the effectiveness of purely domestic, entity-based regulation. The presence of global investors, cross-border funding chains, and internationally mobile capital further complicates enforcement, as activities constrained in one jurisdiction may simply relocate to another. From a systemic standpoint, this fragmentation weakens the capacity of macroprudential policy to lean against the financial cycle ex ante and increases reliance on discretionary interventions during crises.

For emerging market economies, these limitations interact with structural external vulnerability. Many EMs have successfully strengthened bank regulation and improved supervisory capacity over the past decade. Yet they remain deeply exposed to global market-based dynamics that lie beyond the reach of domestic regulators. When global financial conditions tighten, deleveraging by non-bank intermediaries and global investors transmits stress through funding, collateral, and liquidity channels that domestic macroprudential frameworks are ill-equipped to restrain. Regulatory leakage thus becomes a conduit through which external shocks are amplified rather than absorbed.

Taken together, these developments suggest that the effectiveness of macroprudential policy cannot be assessed solely by the resilience of the banking sector. While bank-centric reforms have reduced the likelihood of traditional banking crises, they have not eliminated systemic fragility in financial systems increasingly dominated by market-based intermediation. Understanding the persistence of global shock transmission to emerging markets therefore requires shifting analytical focus from individual institutions to the structure of financial intermediation itself, including the activities, funding arrangements, and institutional boundaries through which risk propagates. This shift provides the foundation for analyzing non-bank financial intermediation and market-based fragility, to which the paper now turns.

3. Market-Based Finance, Non-Bank Intermediation, and Liquidity Fragility

The transformation of global financial intermediation over the past two decades has fundamentally altered the sources and transmission of systemic risk. Whereas banks once dominated credit provision and liquidity transformation, contemporary financial systems are increasingly characterized by market-based finance and a diverse ecosystem of non-bank financial intermediaries. Investment funds, hedge funds, broker-dealers, insurance companies, and other asset managers now account for a substantial share of financial assets and play a central role in securities financing, asset management, and risk transfer. This structural shift has enhanced financial efficiency in normal times, but it has also introduced new and often less visible forms of fragility.

Non-bank financial intermediation differs from traditional banking not only in institutional form, but also in its reliance on market mechanisms for funding and risk management. Many non-bank intermediaries depend heavily on short-term, collateralized funding obtained through repurchase agreements, securities lending, and derivatives markets. Their balance sheets are therefore tightly coupled to market prices, collateral valuations, and margining practices. Unlike banks, which benefit from deposit insurance and lender-of-last-resort facilities, most non-bank intermediaries operate without explicit public backstops, rendering them acutely sensitive to changes in funding conditions.

This reliance on market-based funding creates a direct link between funding liquidity and market liquidity. When asset prices are stable and volatility is low, collateralized funding is abundant and inexpensive, supporting leverage and market-making activity. However, when uncertainty rises, the same mechanisms operate in reverse. Haircuts widen, margin requirements increase, and funding maturities shorten, forcing leveraged investors to either post additional collateral or liquidate positions. These adjustments are mechanical and often synchronized across institutions, generating liquidity spirals in which declining market liquidity and tightening funding conditions reinforce one another.

A defining feature of market-based fragility is that stress propagates through price-based mechanisms rather than through the withdrawal of insured deposits. Market-based runs manifest as refusals to roll over short-term funding, sudden increases in haircuts, and margin calls that compel asset sales. Because these processes are governed by contractual rules and risk management models, they unfold rapidly and leave little scope for discretionary intervention. Moreover, they operate across asset classes and borders, transmitting shocks far beyond their point of origin.

Leverage plays a central role in amplifying these dynamics. Many non-bank investment strategies rely on leverage to enhance returns, particularly in low-volatility environments. Prime brokerage relationships allow hedge funds and other leveraged investors to finance positions through borrowed funds and rehypothecated collateral, effectively embedding leverage deep within market plumbing. While such arrangements improve market liquidity and price efficiency in tranquil periods, they magnify losses and accelerate deleveraging when funding conditions deteriorate.

Empirical evidence from past crises illustrates how abrupt reductions in allowable leverage by prime brokers can trigger widespread asset liquidation. When funding providers reassess risk and tighten constraints, leveraged investors are forced to unwind positions simultaneously, overwhelming market liquidity and driving prices below fundamental values. Because many strategies are crowded and rely on similar funding arrangements, deleveraging by one segment of the market quickly spills over to others, creating feedback loops that destabilize the broader financial system.

These dynamics are further exacerbated by structural changes in dealer intermediation. Regulatory reforms have strengthened bank balance sheets but have also reduced banks’ willingness and capacity to absorb large inventory positions during periods of stress. As a result, market liquidity increasingly depends on non-bank liquidity providers whose participation may be highly procyclical. When volatility rises, these providers often withdraw, leaving markets vulnerable to sharp price dislocations. This shift in market-making capacity has increased the sensitivity of prices to order flow and amplified the impact of forced selling during stress episodes.

From a systemic perspective, the fragility of market-based finance arises not from the weakness of individual institutions, but from the interaction of leverage, funding structures, and market infrastructure. These interactions generate non-linear dynamics in which modest shocks can produce disproportionate effects. Importantly, such dynamics are poorly captured by regulatory frameworks that focus on solvency metrics or institution-specific risk assessments. Instead, they require an analytical lens that emphasizes activities, funding arrangements, and the collective behavior of market participants.

For emerging market economies, the implications are particularly severe. Assets issued by EM borrowers are often treated as riskier and less liquid, leading to sharper increases in haircuts and margin requirements during periods of global stress. When global investors deleverage, EM assets are frequently sold first, not because of deteriorating fundamentals, but because they serve as adjustment margins in global portfolios. The resulting price declines and liquidity shortages transmit stress to domestic financial systems, even when banks remain well-capitalized and solvent.

The expansion of non-bank financial intermediation thus represents a double-edged sword for emerging markets. On the one hand, it broadens access to global capital and supports financial development. On the other, it embeds emerging markets more deeply into global funding and liquidity cycles over which domestic authorities have limited control. Understanding this tension is essential for explaining why improvements in bank regulation and financial integration have not translated into greater resilience to global shocks.

These observations underscore the need to move beyond a bank-centric view of financial stability. Market-based finance and non-bank intermediaries are now central to the transmission and amplification of financial stress, particularly in open economies. Any attempt to explain the persistence of emerging market vulnerability must therefore grapple with the mechanics of funding liquidity, leverage, and market plumbing that define contemporary financial intermediation. The next section situates these mechanisms within the broader context of global financial cycles and commodity-linked exposures, highlighting how global forces interact with market-based fragility to shape outcomes in emerging economies.

4. Global Financial Cycles, Commodity Dynamics, and Emerging Market Vulnerability

The growing prominence of market-based finance and non-bank intermediation must be understood within the broader context of global financial cycles. Contemporary financial integration has produced a system in which credit conditions, asset prices, and risk-taking behavior are increasingly synchronized across countries. These dynamics are shaped by common global factors, including monetary conditions in major financial centers, shifts in investor risk appetite, and leverage cycles among globally active financial intermediaries. As a result, domestic financial conditions in open economies are no longer determined primarily by local fundamentals or policy settings, but by forces that originate outside national borders.

A central insight of the global financial cycle literature is that financial integration constrains the autonomy of domestic macroeconomic policy. Even under flexible exchange rate regimes, emerging market economies remain highly sensitive to global shocks transmitted through financial channels. Empirical evidence consistently shows that changes in global funding conditions—often proxied by monetary policy in advanced economies or by measures of global risk—have a powerful influence on credit growth, asset prices, and financial stability in emerging markets. This pattern challenges traditional views that exchange rate flexibility alone can insulate economies from external disturbances and underscores the importance of financial channels in shaping macroeconomic outcomes.

From a systemic perspective, global financial cycles operate primarily through balance sheets rather than through trade flows. Cross-border portfolio reallocations, funding decisions by global investors, and shifts in leverage among market-based intermediaries transmit shocks rapidly and with limited regard for domestic conditions. When global liquidity is abundant and risk appetite is strong, emerging markets experience capital inflows, currency appreciation, and asset price booms. Conversely, when global conditions tighten, these flows reverse abruptly, generating sharp adjustments in exchange rates, asset valuations, and domestic financial conditions. These dynamics reflect the fact that emerging markets often function as marginal recipients of global capital, adjusting to shifts in global portfolios rather than shaping them.

Commodity markets play a particularly important role in this transmission process. Many emerging economies are either major exporters or importers of commodities, making their macroeconomic and financial performance highly sensitive to global price fluctuations. Commodity price movements affect not only trade balances and fiscal revenues, but also corporate profitability, sovereign risk, and investor perceptions of macroeconomic stability. In periods of global expansion, rising commodity prices often coincide with capital inflows and credit booms in commodity-exporting economies, reinforcing domestic financial cycles. When global conditions deteriorate, commodity prices fall, capital flows reverse, and financial conditions tighten simultaneously, producing severe adjustment pressures.

Importantly, commodity markets have become increasingly financialized. The expansion of futures markets, exchange-traded products, and derivatives has integrated commodity pricing more closely with global financial conditions. As a result, commodity prices now respond not only to physical supply and demand, but also to changes in risk sentiment, funding constraints, and portfolio rebalancing by global investors. This financialization strengthens the link between global liquidity conditions and commodity price dynamics, amplifying the exposure of emerging markets to global financial cycles.

These mechanisms help explain why emerging markets continue to function as price-takers in global financial markets. Structural asymmetries in the international financial system—such as shallower domestic capital markets, higher borrowing costs, and greater reliance on foreign currency funding—limit the ability of emerging economies to absorb shocks internally. When global financial conditions tighten, capital outflows occur regardless of domestic fundamentals, reflecting the reallocation decisions of global investors rather than country-specific developments.

Exchange rate depreciation can mitigate some of the impact of external shocks by restoring competitiveness and absorbing capital flow pressures. However, depreciation also increases the local currency burden of foreign currency liabilities, constraining balance sheets and amplifying financial stress. Monetary tightening to stabilize exchange rates may further depress domestic activity, while fiscal policy is often constrained by procyclical revenue dynamics linked to commodity prices. These trade-offs illustrate the limited policy space available to emerging markets in the face of global financial cycles.

Recent empirical evidence reinforces this interpretation. Studies consistently find that global shocks account for a substantial share of variation in systemic risk measures across countries, with emerging markets exhibiting greater sensitivity than advanced economies. Commodity price movements and cross-border capital flows emerge as key conduits through which global financial conditions affect domestic stability. These findings are consistent with the empirical results documented in the first two articles of this thesis, which show that global energy price shocks exert a causal influence on emerging market asset prices and that deeper financial integration does not eliminate, but rather reshapes, exposure to external disturbances.

Taken together, these observations suggest that the vulnerability of emerging markets is not primarily a function of inadequate domestic regulation or insufficient integration. Instead, it reflects the interaction between global financial cycles, commodity-linked exposures, and market-based transmission mechanisms that operate beyond the reach of traditional macroprudential frameworks. In such an environment, improvements in bank resilience and institutional quality are necessary but not sufficient conditions for financial stability. Understanding the persistence of emerging market vulnerability therefore requires integrating global financial dynamics with the microstructure of market-based finance, a task undertaken in the next section through the development of an integrated framework of macro-financial blind spots.

5. Macro-Financial Blind Spots: An Integrated Framework and Policy Implications

The preceding sections have shown that the persistence of emerging market vulnerability cannot be fully understood through bank balance sheets, domestic macroeconomic fundamentals, or institutional development alone. Instead, it reflects the interaction between global financial cycles, market-based intermediation, and regulatory architectures that remain fragmented and incomplete. This section brings these elements together in an integrated conceptual framework that identifies the macro-financial blind spots through which global shocks are transmitted and amplified in emerging markets, and derives implications for the design of macro-financial governance.

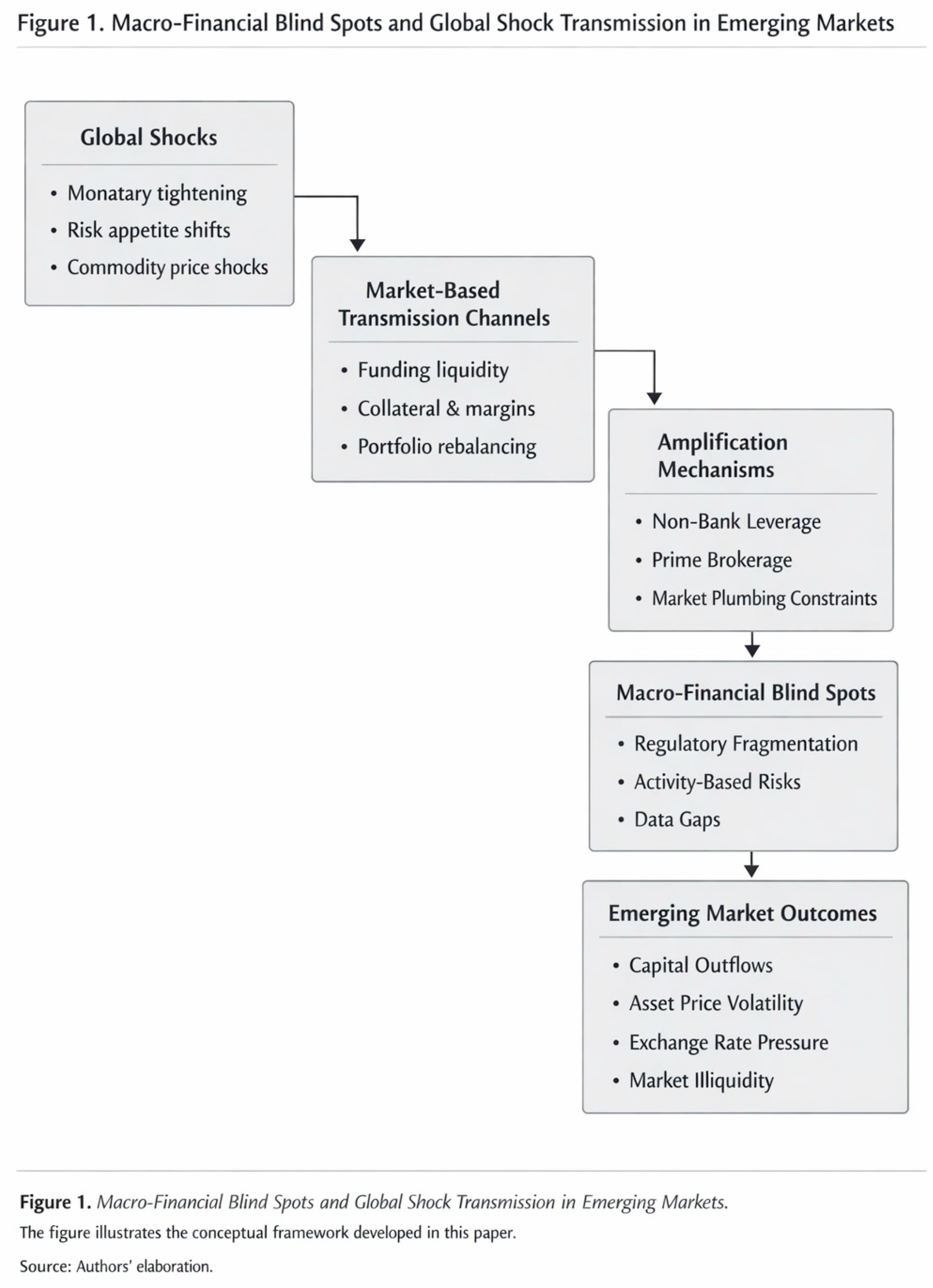

Figure 1 summarizes the integrated conceptual framework developed in this section.

The figure illustrates the conceptual framework developed in this paper. Global financial shocks—such as monetary tightening, shifts in risk appetite, and commodity price fluctuations—are transmitted through market-based channels dominated by funding liquidity, collateral valuation, and portfolio rebalancing. These channels are amplified by non-bank leverage, prime brokerage arrangements, and constraints in market plumbing. Regulatory and institutional fragmentation creates macro-financial blind spots that limit the effectiveness of bank-centric macroprudential frameworks, resulting in persistent financial vulnerability in emerging markets.

At the core of the framework lies the observation that systemic risk increasingly originates in activities rather than institutions. Market-based finance relies on short-term funding, collateral valuation, and leverage that are inherently procyclical. When global financial conditions are benign, these mechanisms support liquidity, compress risk premia, and facilitate cross-border capital allocation. However, when conditions tighten, the same mechanisms generate nonlinear adjustments that propagate stress rapidly across markets and jurisdictions. Crucially, these dynamics operate largely outside the scope of traditional macroprudential tools, which remain focused on regulated banks and entity-level balance sheet constraints.

The framework traces a sequence of transmission from global shocks to domestic financial stress. Global disturbances—such as shifts in monetary policy in core economies, abrupt changes in investor risk appetite, or commodity price shocks—first affect funding conditions and asset valuations in major financial markets. These effects are transmitted internationally through portfolio rebalancing, cross-border funding flows, and changes in collateral requirements. Market-based intermediaries respond by adjusting leverage and liquidity positions, often in a synchronized manner, amplifying price movements and tightening funding conditions. Emerging markets, positioned at the periphery of global portfolios, absorb a disproportionate share of these adjustments.

Funding liquidity plays a central role in this process. Because non-bank intermediaries depend on short-term, collateralized funding, access to liquidity is highly sensitive to changes in market prices and volatility. In periods of stress, haircuts widen, margins increase, and funding maturities shorten. These adjustments force deleveraging and asset sales, reinforcing declines in market liquidity. Unlike traditional bank runs, which unfold through depositor withdrawals, market-based runs materialize through mechanical margining and collateral valuation rules that leave little room for discretionary intervention.

Collateral dynamics further intensify these feedback loops. Assets issued by emerging market borrowers are typically treated as riskier and less liquid, leading to sharper increases in haircuts during periods of global stress. As a result, EM assets are often sold first in global deleveraging episodes, not because of deteriorating fundamentals, but because they function as adjustment margins in global portfolios. This mechanism links global funding conditions directly to domestic financial stress, independent of local banking sector health.

Leverage acts as a powerful amplifier within this framework. Prime brokerage arrangements and securities financing transactions embed leverage deep within market plumbing, allowing investors to expand positions rapidly during tranquil periods. When funding providers reassess risk, leverage can be withdrawn abruptly, triggering forced asset sales and price dislocations. Because leverage is often opaque and unevenly monitored, regulators may underestimate its systemic importance until deleveraging is already underway. In emerging markets, leverage amplification is compounded by currency mismatches and reliance on foreign funding, which magnify balance sheet stress during exchange rate depreciations.

Market plumbing and dealer intermediation represent another critical dimension of the framework. Regulatory reforms have enhanced bank resilience but have also constrained dealer balance sheets, reducing market-making capacity during periods of stress. As a result, liquidity provision increasingly depends on non-bank actors whose participation is highly sensitive to funding conditions. When volatility rises, these actors often withdraw, leaving markets vulnerable to disorderly price adjustments. This shift has increased the fragility of markets central to emerging market financing, such as sovereign bond and foreign exchange markets.

Institutional and regulatory fragmentation constitutes the final and perhaps most consequential blind spot. Oversight of market-based finance is typically divided across multiple agencies with narrow mandates, while cross-border activities fall between national jurisdictions. Macroprudential tools remain largely entity-based and bank-focused, even as systemic risk migrates toward activities and funding arrangements that span institutions and borders. Data gaps further limit the ability of authorities to monitor leverage, liquidity mismatches, and interconnectedness in real time. As a result, vulnerabilities accumulate outside the regulatory perimeter, and policy responses are often delayed until stress has already materialized.

These structural blind spots help explain why macroprudential policy, despite its success in strengthening banks, has not eliminated systemic vulnerability in emerging markets. They also clarify why authorities have repeatedly resorted to extraordinary interventions—such as broad-based liquidity provision, asset purchases, and emergency funding facilities—to stabilize markets during crises. Such interventions are effective in the short term but raise concerns about moral hazard and the sustainability of market-based finance in the absence of stronger ex ante safeguards.

The framework developed here carries important implications for macro-financial governance in emerging markets. First, it underscores the need to move beyond bank-centric macroprudential regulation toward system-wide, activity-based approaches that address leverage, liquidity, and funding risk wherever they arise. This does not imply replicating bank regulation across all market participants, but rather tailoring tools to specific activities, such as securities financing, derivatives margining, and open-ended fund liquidity management.

Second, the framework highlights the importance of improving data and transparency. Effective oversight of market-based finance requires granular, timely information on leverage, collateral usage, and interconnectedness across institutions and markets. Closing data gaps is a prerequisite for identifying emerging vulnerabilities and calibrating policy responses before stress escalates.

Third, institutional coordination must be strengthened both domestically and internationally. Fragmented mandates and jurisdictional boundaries undermine the effectiveness of macroprudential policy in an integrated financial system. Establishing clear mechanisms for cross-agency coordination, information sharing, and joint decision-making can enhance the capacity of authorities to address system-wide risks. At the international level, cooperation is essential to limit regulatory arbitrage and manage cross-border spillovers that disproportionately affect emerging markets.

Finally, the framework suggests that financial resilience in emerging markets depends not only on domestic reforms, but also on the evolution of the global financial architecture. As long as global financial cycles and market-based intermediation dominate capital allocation, emerging markets will remain exposed to shocks originating elsewhere. Strengthening macro-financial governance therefore requires a combination of domestic policy innovation and international coordination aimed at aligning financial integration with stability.

In sum, the persistence of emerging market vulnerability reflects structural features of contemporary finance rather than policy failures in isolation. By identifying the macro-financial blind spots through which global shocks are transmitted and amplified, this framework provides a basis for rethinking macroprudential policy in an era of market-based finance and globalized funding.

6. Conclusion

This paper has argued that the persistent vulnerability of emerging market economies to global financial shocks cannot be adequately explained by weaknesses in bank balance sheets, domestic macroeconomic fundamentals, or insufficient regulatory effort. Instead, it reflects deeper structural features of contemporary financial systems in which market-based intermediation, short-term funding, and fragmented regulatory oversight play a central role in the transmission and amplification of global disturbances.

The analysis has shown that the macroprudential turn following the Global Financial Crisis, while successful in strengthening bank resilience, has remained largely bank-centric. As financial intermediation has shifted toward non-bank actors and market-based mechanisms, systemic risk has increasingly migrated to activities that lie outside the effective reach of traditional macroprudential tools. Funding liquidity, collateral valuation, margin dynamics, and leverage embedded in market plumbing have emerged as key drivers of instability, particularly in periods of global stress.

Within this environment, global financial cycles continue to exert a dominant influence over domestic financial conditions in emerging markets. Shifts in global liquidity, risk appetite, and leverage propagate rapidly through capital flows, asset prices, and commodity markets, constraining the autonomy of domestic policy frameworks. The resulting adjustment burden falls disproportionately on emerging economies, which often function as price-takers in global portfolios and absorb shocks through abrupt capital flow reversals, exchange rate movements, and market illiquidity.

The integrated framework developed in this paper highlights the existence of macro-financial blind spots that arise from the interaction of these forces. Systemic vulnerabilities accumulate not because of regulatory neglect per se, but because regulatory architectures remain fragmented and ill-suited to address activity-based risks that cut across institutions, markets, and borders. As a result, policy responses are frequently delayed until stress has already materialized, forcing authorities to rely on extraordinary interventions to stabilize markets.

These findings carry important implications for the design of macro-financial governance in emerging markets. Strengthening financial stability in an era of market-based finance requires moving beyond entity-based regulation toward system-wide approaches that address leverage, liquidity, and funding risk wherever they arise. It also requires improved data and transparency to monitor interconnectedness and vulnerabilities in real time, as well as stronger coordination among domestic regulatory agencies and across jurisdictions. While such reforms are complex and politically challenging, they are essential for aligning financial integration with stability.

More broadly, the persistence of emerging market vulnerability underscores the limits of purely national solutions in a globalized financial system. As long as global financial cycles and market-based intermediation dominate capital allocation, emerging markets will remain exposed to shocks originating elsewhere. Enhancing resilience therefore depends not only on domestic policy innovation, but also on progress toward a more coherent and cooperative international financial architecture.

Future research could extend the framework developed here by empirically testing specific transmission channels, examining the effectiveness of activity-based macroprudential tools, and exploring how institutional design influences policy outcomes across different emerging market contexts. Such work would further clarify the conditions under which financial integration can support sustainable growth without undermining stability.

In conclusion, understanding and addressing macro-financial blind spots is essential for rethinking macroprudential policy in the twenty-first century. By shifting analytical focus from institutions to activities and from domestic balance sheets to global funding dynamics, this paper contributes to ongoing debates on how to reconcile financial integration with systemic resilience in emerging markets.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Aiyar, S., Calomiris, C. W., & Wieladek, T. (2014). Does macro-prudential regulation leak? Evidence from a UK policy experiment. Journal of Money, Credit and Banking, 46(1), 181–214. [CrossRef]

- Aramonte, S., Schrimpf, A., & Shin, H. S. (2021). Non-bank financial intermediaries and financial stability. BIS Working Papers, No. 972. Bank for International Settlements.

- Bank for International Settlements. (2025). BIS quarterly review: International banking and financial market developments (December). BIS.

- Brunnermeier, M. K., & Pedersen, L. H. (2009). Market liquidity and funding liquidity. Review of Financial Studies, 22(6), 2201–2238. [CrossRef]

- Calvo, G. A. (1998). Capital flows and capital-market crises: The simple economics of sudden stops. Journal of Applied Economics, 1(1), 35–54.

- Claessens, S., Ratnovski, L., & Singh, M. (2021). Macroprudential policies and non-bank financial intermediation. International Journal of Central Banking, 17(2), 1–45.

- Crockett, A. (2000). Marrying the micro- and macro-prudential dimensions of financial stability. BIS Speeches. Bank for International Settlements.

- Deku, S. Y., Kara, A., & Zhou, H. (2019). Securitisation and financial stability: A systematic review of the literature. International Review of Financial Analysis, 63, 189–202. [CrossRef]

- Duffie, D. (2020). Intermediation of U.S. Treasury securities after the COVID-19 crisis. Hutchins Center Working Paper No. 72. Brookings Institution.

- Eichengreen, B., & Hausmann, R. (Eds.). (2005). Other people’s money: Debt denomination and financial instability in emerging market economies. University of Chicago Press.

- European Systemic Risk Board. (2024). A system-wide approach to macroprudential policy. ESRB.

- Falato, A., Goldstein, I., & Hortaçsu, A. (2020). Financial fragility in the COVID-19 crisis: The case of investment funds in corporate bond markets. NBER Working Paper No. 27559. [CrossRef]

- Financial Stability Board. (2020). Holistic review of the March 2020 market turmoil. FSB.

- Financial Stability Board. (2025). Global monitoring report on non-bank financial intermediation 2025. FSB.

- Financial Stability Board. (2025). Leverage in non-bank financial intermediation: Final report. FSB.

- Gorton, G., & Metrick, A. (2012). Regulated banking and the run on repo. Journal of Financial Economics, 104(3), 425–451. [CrossRef]

- Haddad, V., Moreira, A., & Muir, T. (2021). When selling becomes viral: Disruptions in debt markets in the COVID-19 crisis and the Fed’s response. Review of Financial Studies, 34(11), 5309–5351. [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y., & Jiang, Y. (2025). Shadow banking and systemic risk: Evidence and channels. Research in International Business and Finance, 69, Advance online publication.

- Kindleberger, C. P., & Aliber, R. Z. (2011). Manias, panics, and crashes: A history of financial crises (6th ed.). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Minsky, H. P. (1986). Stabilizing an unstable economy. Yale University Press.

- Mitchell, M., Pedersen, L. H., & Pulvino, T. (2012). Slow moving capital. Journal of Finance, 67(6), 2151–2193. [CrossRef]

- Mishra, A. K., Narayan, P. K., & Smyth, R. (2020). Stock market liquidity, funding liquidity, and monetary policy. International Review of Economics & Finance, 67, 51–65. [CrossRef]

- Rey, H. (2015). Dilemma not trilemma: The global financial cycle and monetary policy independence. In Proceedings of the Jackson Hole Economic Policy Symposium. Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City.

- Ryu, D., Webb, R. I., & Yu, J. (2022). Funding liquidity shocks and market liquidity providers. Finance Research Letters, 47, 102734. [CrossRef]

- Schrimpf, A., Shin, H. S., & Sushko, V. (2020). Leverage and margin spirals in fixed income markets during the COVID-19 crisis. BIS Bulletin, No. 2.

- Sikalao-Lekobane, O. (2025). Macroprudential tightening and FinTech credit: Evidence of regulatory arbitrage. Economic Modelling, 123, Advance online publication.

- Zhu, Y., & Ma, S. (2025). Global financial cycle downturns and systemic risk: Evidence and transmission channels. Borsa Istanbul Review, 25(1), 1–15.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).