Submitted:

22 December 2025

Posted:

23 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

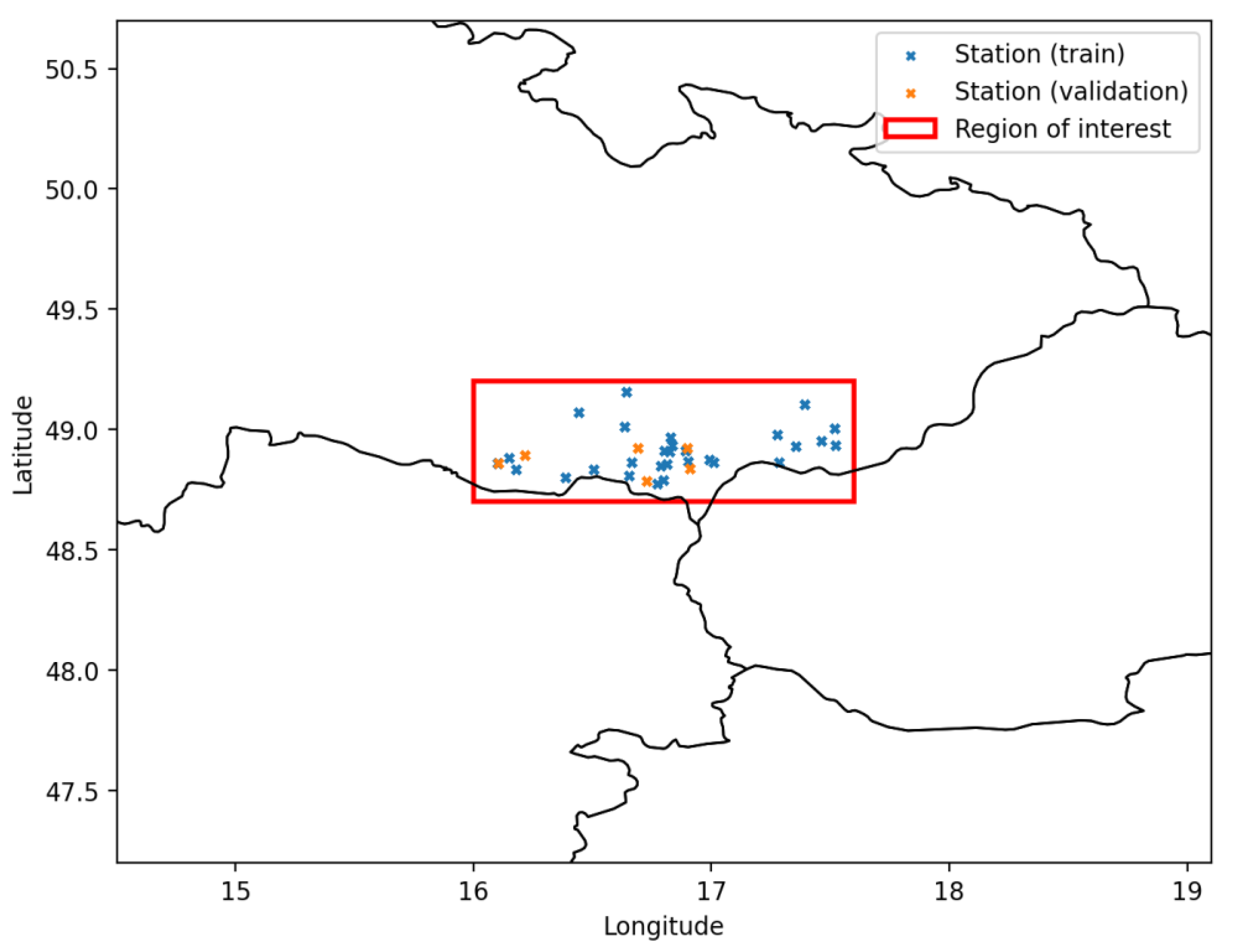

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Data

2.2.1. Numerical Weather Prediction Data (GFS)

2.2.2. Agricultural Weather Station Network

2.2.3. Static Geographic Data

- Latitude and longitude;

- Elevation from the ASTER Global Digital Elevation Model at 500 m resolution;

- North–south and east–west elevation gradients computed by finite differences, used to represent slope magnitude and aspect-related effects.

2.2.4. Data Integration and Feature Construction

- Station-based predictors: recent temperature history and, where available, other meteorological variables aggregated over the preceding hours;

- GFS-based predictors: the full set of selected surface and low-level fields at the station grid cell, optionally including derived features such as helicity, minimum temperature above ground, and precipitable water;

- Static physiographic descriptors: elevation and slope components as described above.

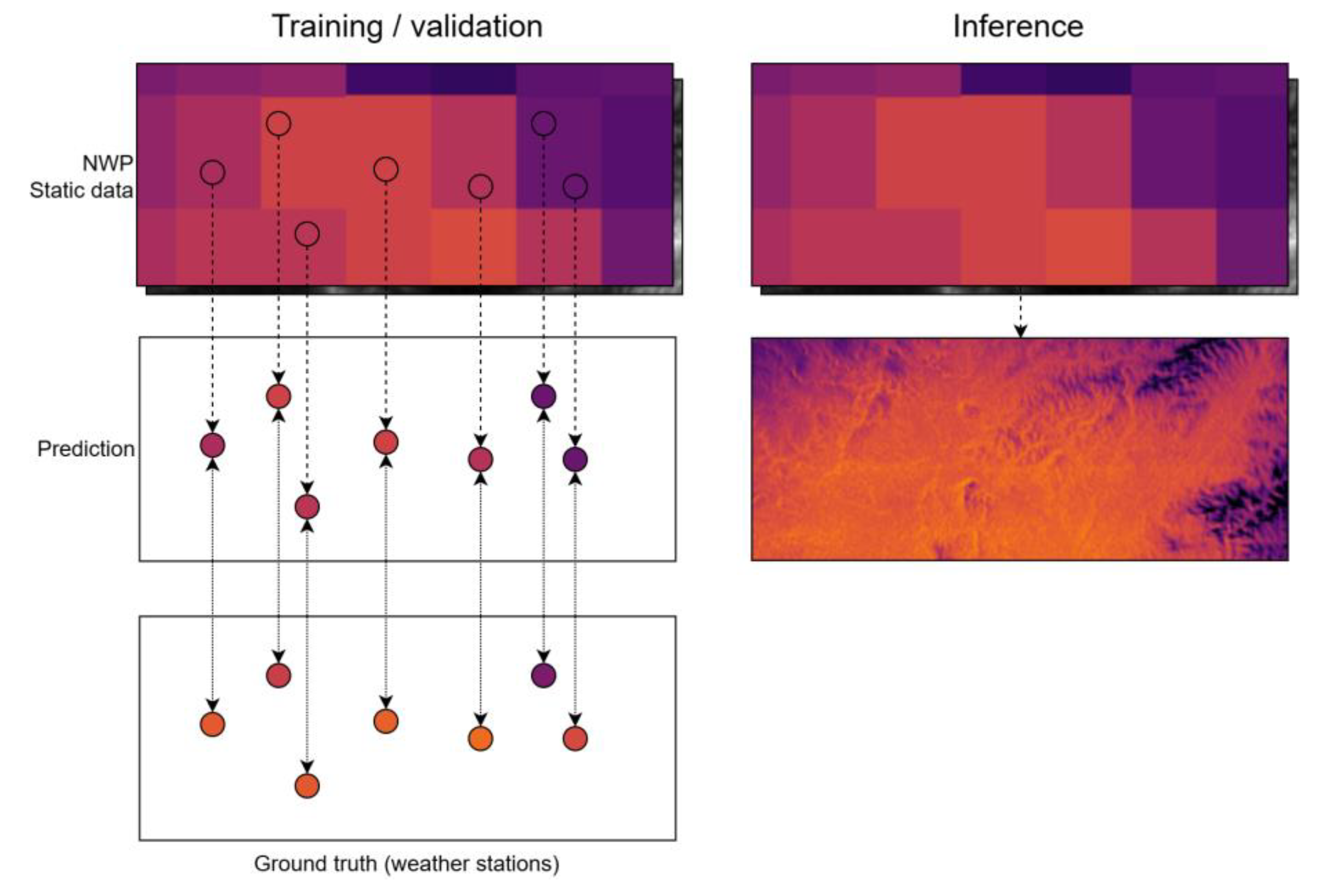

2.3. Overall System Architecture

2.3.1. Logical Workflow

-

Acquisition and ingestion

- ○

- External forecast data (GFS) are downloaded on a rolling basis and stored in a dedicated repository

- ○

- Station measurements are ingested into SensLog through feeder services, which normalize formats and apply basic quality control.

-

Pre-processing and feature assembly

- ○

- A preprocessing layer maps station locations to the GFS grid, merges dynamic predictors with static physiographic attributes, and constructs feature vectors and target values for each station and time step.

- ○

- The same layer prepares a high-resolution prediction grid over the southern Moravia domain by sampling static geographic predictors at the desired spatial resolution.

-

Model training

- ○

- Models are trained using historical data, with different model families evaluated under identical spatiotemporal cross-validation schemes (Section 2.4).

-

Operational inference and superresolution

- ○

- For a given forecast time, a trained model ingest the latest available GFS forecast fields and, where relevant, static attributes to produce 24-hour temperature predictions at the desired resolution.

-

Publication and integration

- ○

- Resulting high-resolution temperature fields and station-level forecasts are stored in SensLog and exposed via standardized APIs so that other ALIANCE components (e.g., localized weather forecast services, crop and risk models) can consume them.

2.3.2. Infrastructure Integration

2.4. Models

2.4.1. Problem Formulation

2.4.2. Base Predictive Model

- Bayesian Neural Fields (BayesNF)

- LightGBM

- TabPFN

- Transformer for tabular bias correction

2.4.3. Hybrid KNN Superresolution

- For each station, a base model (LightGBM, TabPFN, Transformer, or BayesNF) is trained and used to generate a 24-h temperature forecast at the station location.

- For each target grid cell, KNN interpolation is applied in the space of static geographical predictors (latitude, longitude, elevation, gradients). All features are normalized prior to distance computation. The optimal number of neighbours is set to the number of available stations, which empirically provided the best trade-off between stability and local adaptation.

2.4.4. Training and Evaluation Protocol

- Temporal partitioning of the dataset into training and validation periods;

- Spatial partitioning into training and validation subsets of stations.

3. Results

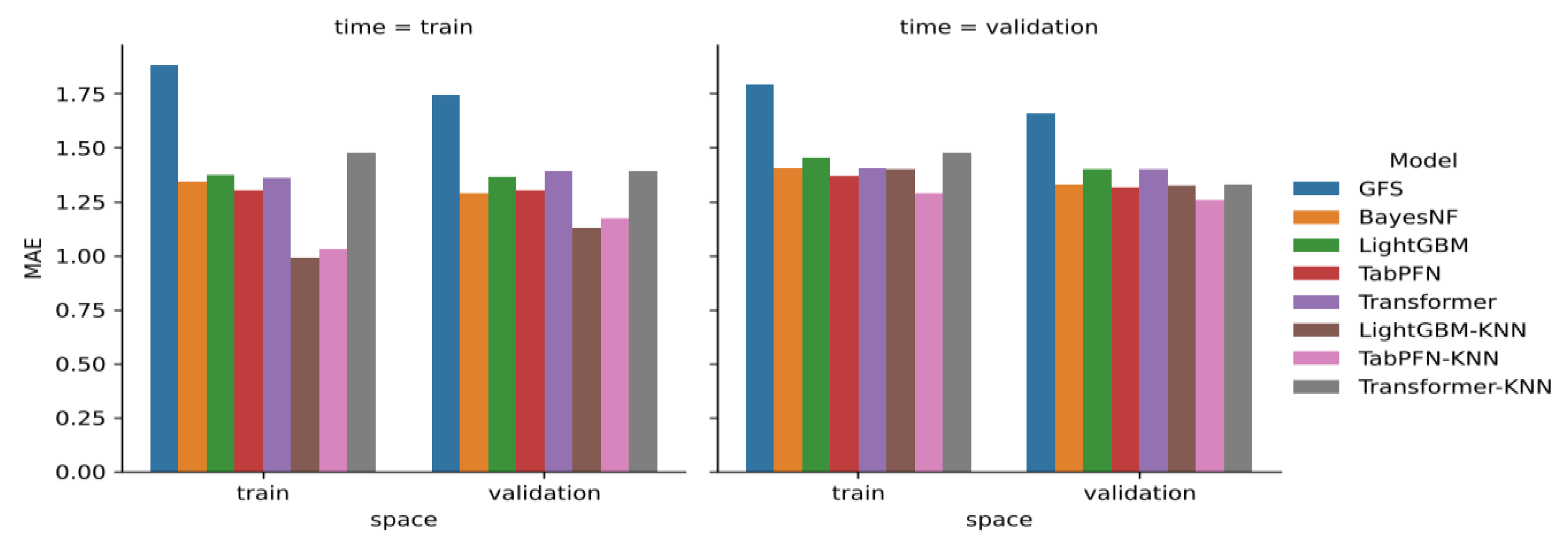

3.1. Quantitative Evaluation on Spatiotemporal Splits

3.2. Comparative Overview of Split-Dependent Performance

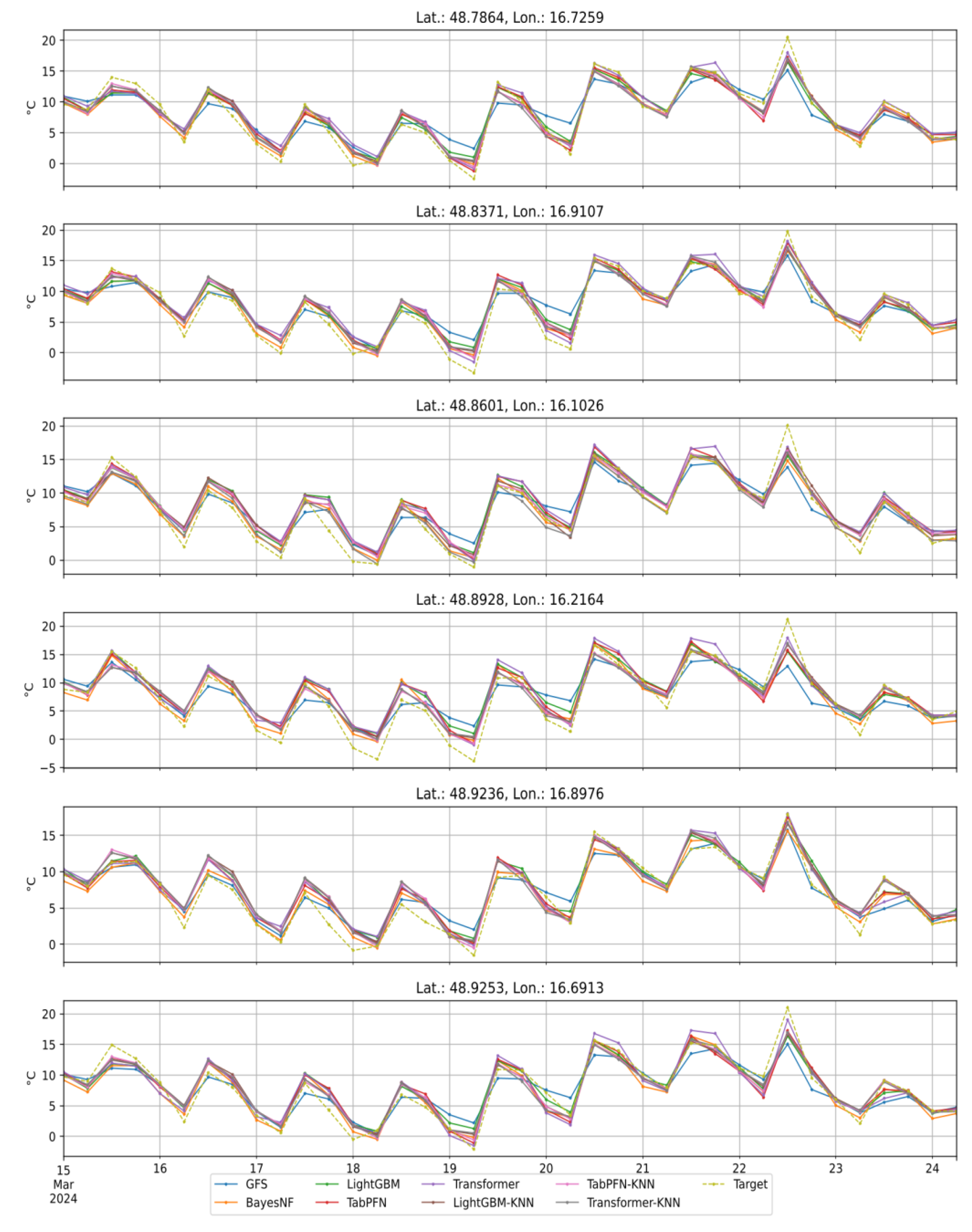

3.3. Time-Series Example at Validation Stations

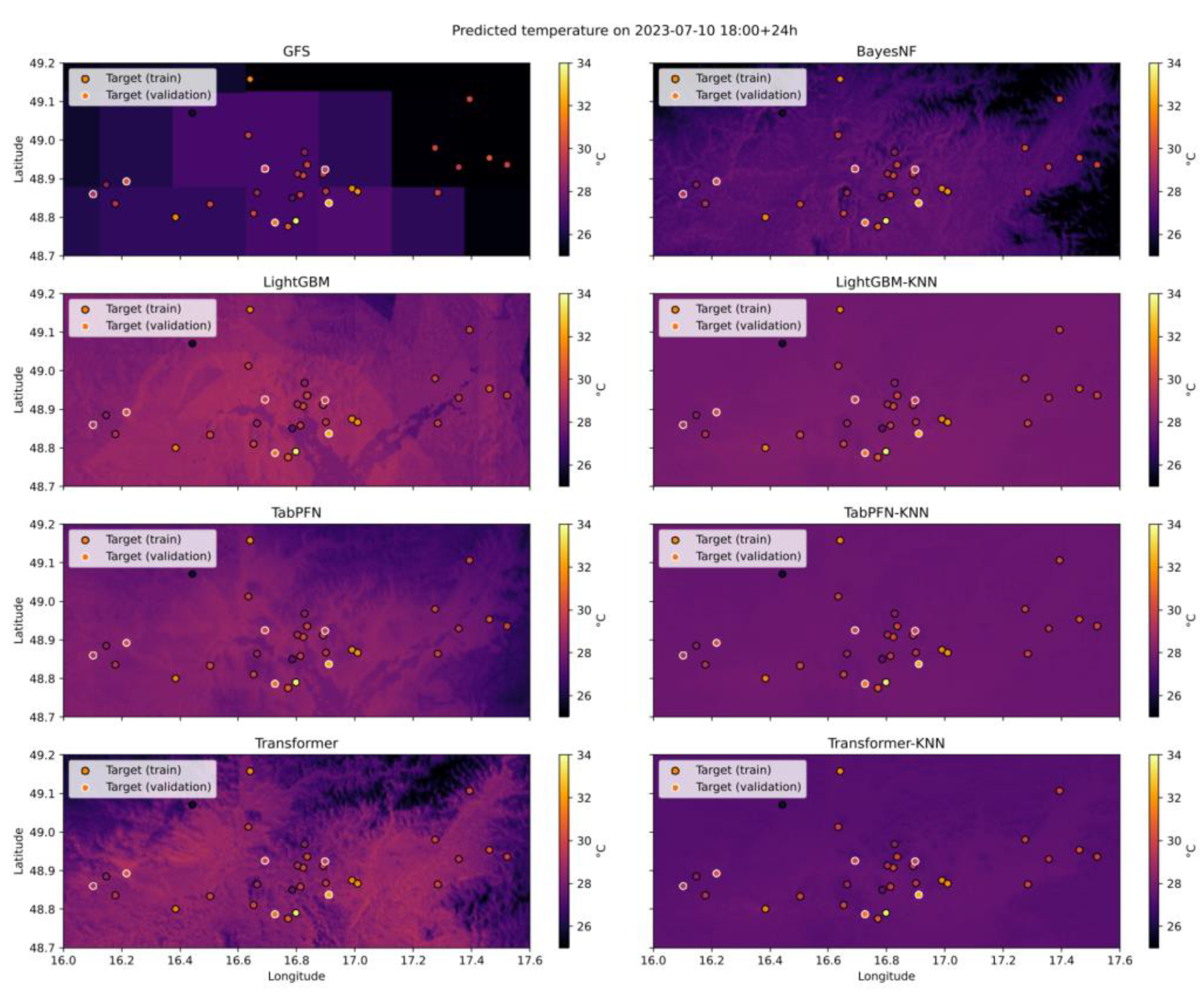

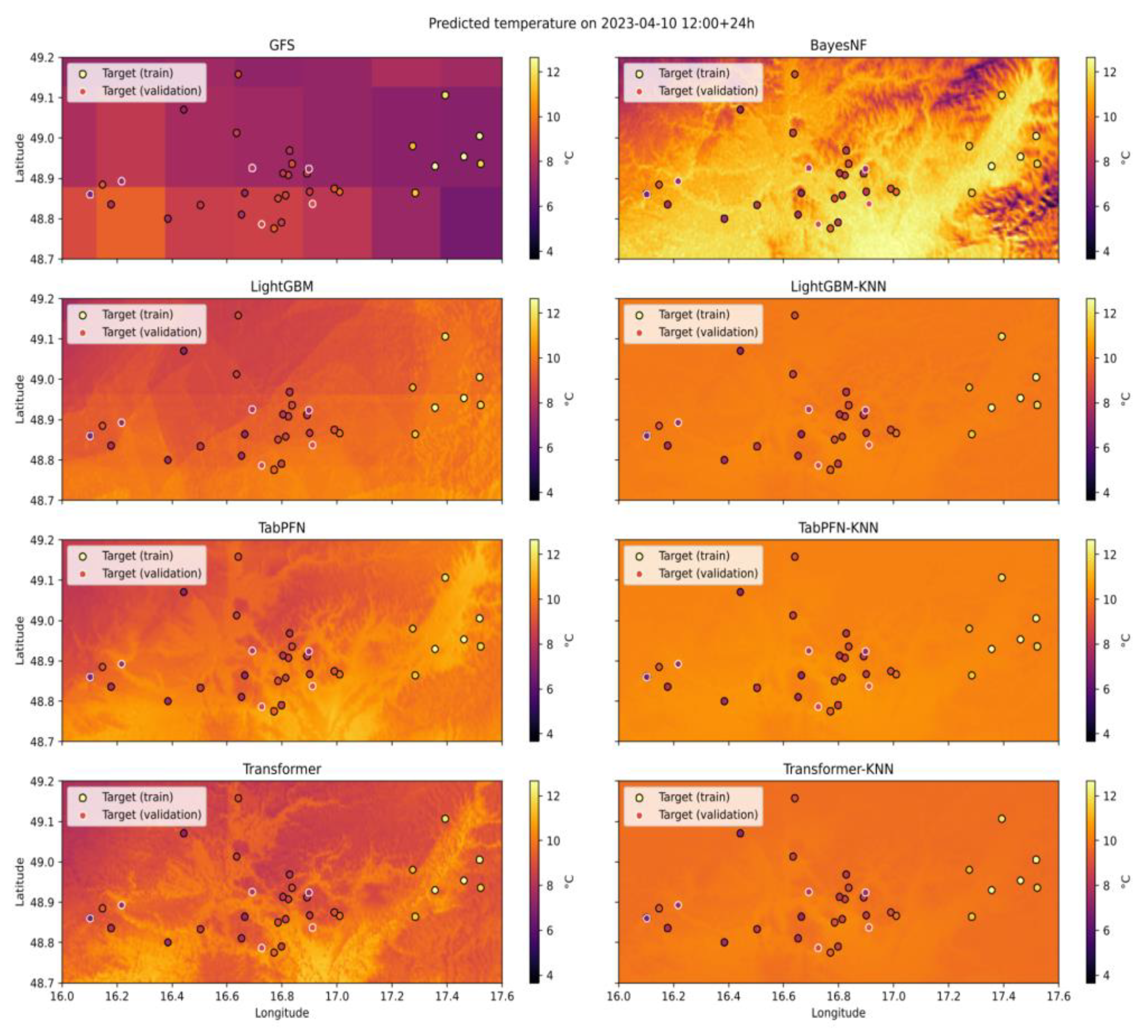

3.4. Spatial Superresolution Maps (Qualitative Assessment)

4. Discussion

4.1. Model Ranking and Generalization Behaviour

4.2. Interpretation of the KNN Superresolution Effect

4.3. Practical Recommendation for Operational Deployment

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ALIANCE | Advanced Lightweight Infrastructure for Agriculture through Novel Computing and Environmental services |

| ASTGTM | ASTER Global Digital Elevation Model |

| CTU | Czech Technical University in Prague |

| ERA5 | Fifth Generation ECMWF Atmospheric Reanalysis |

| ERA5-Land | ERA5 Dataset Focused on Land Variables |

| EO | Earth Observation |

| GFS | Global Forecast System |

| KNN | K-Nearest Neighbours |

| MAE | Mean Absolute Error |

| ML | Machine Learning |

| NWP | Numerical Weather Prediction |

| SensLog | Sensor Logging and Integration Platform |

| SHAP | SHapley Additive exPlanations |

| TabPFN | Tabular Prior-Data Fitted Network |

| TA ČR | Technology Agency of the Czech Republic |

| U-Net | Convolutional Neural Network Architecture for Image Segmentation |

References

- United Nations; Department of Economic and Social Affairs; Population Division. World Population Prospects 2019: Highlights; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- IPCC. Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Bongiovanni, R.; Lowenberg-DeBoer, J. Precision agriculture and sustainability. Precision Agriculture 2004, 5, 359–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finger, R.; Swinton, S.M.; El Benni, N.; Walter, A. Precision farming at the nexus of agricultural production and the environment. Annu. Rev. Resour. Econ. 2019, 11, 313–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Getahun, S.; Kefale, H.; Gelaye, Y. Application of precision agriculture technologies for sustainable crop production and environmental sustainability: A systematic review. Sci. World J. 2024, 2024, 2126734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Global Forecast System (GFS) Technical Documentation; National Weather Service: Silver Spring, MD, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.; D’Odorico, P.; Evans, J.P.; Eldridge, D.J.; McCabe, M.F.; Caylor, K.K.; King, E.G. The effects of local topography on precipitation distribution in a mountainous watershed. J. Hydrometeorol. 2018, 19, 1131–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollinger, S.E.; Angel, J.R. Standard meteorological measurements. Agron. Monogr. 2013, 47, 3–31. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Zhang, M.; Liang, Y. Agricultural meteorological monitoring system for intelligent agricultural management. Int. J. Agric. Biol. Eng. 2017, 10, 89–97. [Google Scholar]

- Dunn, R.J.H.; Willett, K.M.; Parker, D.E.; Mitchell, L. Expanding HadISD: Quality-controlled, sub-daily station data from 1931. Geosci. Instrum. Method. Data Syst. 2016, 5, 473–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunn, R.J.H. HadISD Version 3: Monthly Updates. Hadley Centre Technical Note, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Hersbach, H.; Bell, B.; Berrisford, P.; Hirahara, S.; Horányi, A.; Muñoz-Sabater, J.; Nicolas, J.; Peubey, C.; Radu, R.; Schepers, D.; et al. The ERA5 global reanalysis. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 2020, 146, 1999–2049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Sabater, J.; Dutra, E.; Agustí-Panareda, A.; Albergel, C.; Arduini, G.; Balsamo, G.; Boussetta, S.; Choulga, M.; Harrigan, S.; Hersbach, H.; et al. ERA5-Land: A state-of-the-art global reanalysis dataset for land applications. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2021, 13, 4349–4383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balsamo, G.; Agustí-Panareda, A.; Albergel, C.; Arduini, G.; Beljaars, A.; Bidlot, J.; Blyth, E.; Bousserez, N.; Boussetta, S.; Brown, A.; et al. Satellite and in situ observations for advancing global Earth surface modelling: A review. Remote Sens. 2018, 10, 2038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koutenský, F.; Pihrt, J.; Cepek, M.; Rybář, V.; Šimánek, P.; Kepka, M.; Jedlička, K.; Charvát, K. Combining Local and Global Weather Data to Improve Forecast Accuracy for Agriculture. Unpublished manuscript;based on experiments with HadISD, GFS, and ERA5-Land for the Czech Republic. [CrossRef]

- LeCun, Y.; Bengio, Y.; Hinton, G. Deep learning. Nature 2015, 521, 436–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grover, A.; Kapoor, A.; Horvitz, E. A deep hybrid model for weather forecasting. In Proceedings of the 21st ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, New York, NY, USA, 2015; ACM; pp. 379–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Jia, Y.; Gao, J.; Song, W.; Leung, H. Short-term rainfall forecasting using multi-layer perceptron. IEEE Trans. Big Data 2018, 6, 93–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hancock, J.T.; Khoshgoftaar, T.M. CatBoost for big data: An interdisciplinary review. J. Big Data 2020, 7, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ke, G.; Meng, Q.; Finley, T.; Wang, T.; Chen, W.; Ma, W.; Ye, Q.; Liu, T.-Y. LightGBM: A highly efficient gradient boosting decision tree. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2017, 30. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, W.; Peng, J.; Cai, Y. Multifactor spatio-temporal correlation model based on a combination of convolutional neural network and long short-term memory neural network for wind speed forecasting. Energy Convers. Manag. 2019, 185, 783–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hewage, P.; Behera, A.; Trovati, M.; Pereira, E.; Ghahremani, M.; Palmieri, F.; Liu, Y. Temporal convolutional neural (TCN) network for an effective weather forecasting using time-series data from the local weather station. Soft Comput. 2020, 24, 16453–16482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabaei, S.; Sharafati, A.; Yaseen, Z.M.; Shahid, S. Copula based assessment of meteorological drought characteristics: Regional investigation of Iran. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2019, 276, 107611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Racah, E.; Correa, J.; Khosrowshahi, A.; Lavers, D.; Kunkel, K.; Wehner, M.; Collins, W.; et al. Application of deep convolutional neural networks for detecting extreme weather in climate datasets. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1605.01156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, G.J.; Lucas, D.D. Machine learning predictions of a multiresolution climate model ensemble. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2018, 45, 4273–4280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichstein, M.; Camps-Valls, G.; Stevens, B.; Jung, M.; Denzler, J.; Carvalhais, N.; Prabhat. Deep learning and process understanding for data-driven Earth system science. Nature 2019, 566, 195–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasp, S.; Pritchard, M.S.; Gentine, P. Deep learning to represent subgrid processes in climate models. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, 9684–9689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandal, T.; Kodra, E.; Ganguly, S.; Michaelis, A.; Nemani, R.; Ganguly, A.R. DeepSD: Generating high resolution climate change projections through single image super-resolution. In Proceedings of the 23rd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, New York, NY, USA, 2017; ACM; pp. 1663–1672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sha, Y.; Gagne, D.J., II; West, G.; Stull, R. Deep-learning-based gridded downscaling of surface meteorological variables in complex terrain. Part II: Daily precipitation. J. Appl. Meteorol. Climatol. 2020, 59, 2075–2092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Li, Q.; Peng, X.; Lv, Q. A temporal downscaling model for gridded geophysical data with enhanced residual U-Net. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronneberger, O.; Fischer, P.; Brox, T. U-Net: Convolutional networks for biomedical image segmentation. In Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention—MICCAI 2015; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 234–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Yang, A.; Amor, R.A.; Zhang, B.; Rao, D. Super Resolution on Global Weather Forecasts. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2409.11502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bendre, M.R.; Thool, R.C.; Thool, V.R. Precision agriculture using wireless sensor network system: Opportunities and challenges. Int. J. Comput. Appl. 2015, 128, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Ukhurebor, K.E.; Adetunji, C.O.; Olugbemi, O.T.; Nwankwo, W.; Olayinka, A.S.; Umezuruike, C.; Hefft, D.I. Precision agriculture: Weather forecasting for future farming. In AI, Edge and IoT-Based Smart Agriculture; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022; pp. 101–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bramantoro, A.; Suhaili, W.S.; Siau, N.Z. Precision agriculture through weather forecasting. 2022 International Conference on Digital Transformation and Intelligence (ICDI), 2022; IEEE: New York, NY, USA; pp. 203–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Hachimi, C.; Belaqziz, S.; Khabba, S.; Chehbouni, A. Towards precision agriculture in Morocco: A machine learning approach for recommending crops and forecasting weather. 2021 International Conference on Digital Age & Technological Advances for Sustainable Development (ICDATA), 2021; IEEE: New York, NY, USA; pp. 88–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kepka, M.; Charvát, K.; Šplíchal, M.; Křivánek, Z.; Musil, M.; Leitgeb, Š.; Bērziņš, R. The senslog platform–a solution for sensors and citizen observatories. In International Symposium on Environmental Software Systems; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 372–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kepka, M.; Charvát, K.; Šplíchal, M.; Křivánek, Z.; Musil, M.; Leitgeb, Š.; Bērziņš, R. The SensLog Platform–A Solution for Sensors; Environmental Software Systems. Computer Science for Environmental Protection: 12th IFIP WG 5.11 International Symposium, ISESS 2017, Zadar, Croatia, May 10–12, 2017, Proceedings, Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; Vol. 507, p. 372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Model | Time=train, Space=train | Time=train, Space=validation | Time=validation, Space=train | Time=validation, Space=validation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GFS | 1.88 | 1.75 | 1.79 | 1.66 |

| BayesNF | 1.34 | 1.29 | 1.40 | 1.33 |

| LightGBM | 1.37 | 1.37 | 1.46 | 1.40 |

| TabPFN | 1.30 | 1.30 | 1.37 | 1.32 |

| Transformer | 1.36 | 1.39 | 1.40 | 1.40 |

| LightGBM–KNN | 0.99 | 1.13 | 1.40 | 1.32 |

| TabPFN–KNN | 1.03 | 1.17 | 1.29 | 1.26 |

| Transformer–KNN | 1.48 | 1.39 | 1.48 | 1.33 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).