1. Introduction

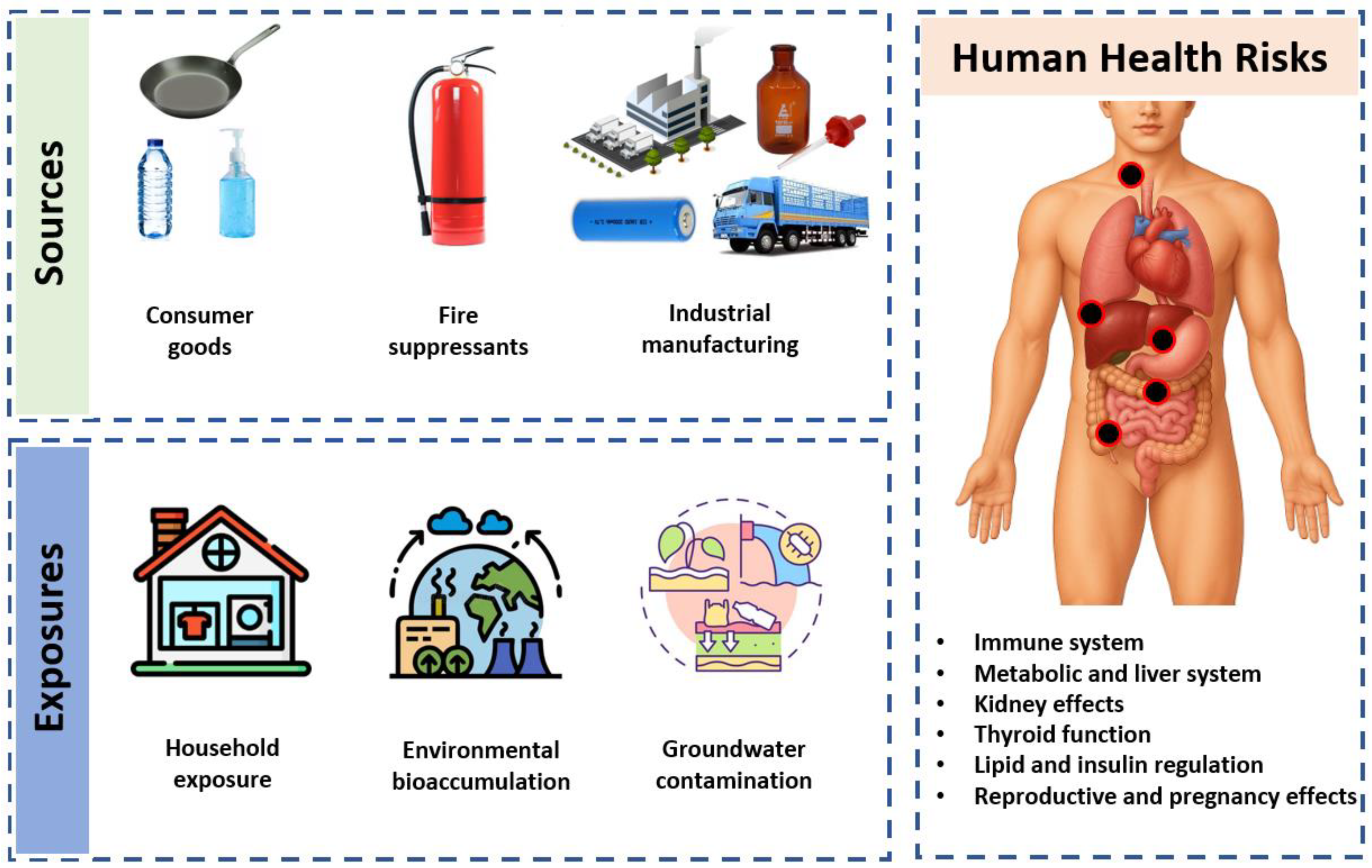

Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) are a broad class of synthetic, fluorinated organic compounds widely used in industrial and consumer products (e.g. firefighting foams, non-stick coatings, textiles) due to their unique surfactant properties and extreme chemical stability [

1,

2]. PFAS molecules consist of a fully fluorinated carbon chain of varying length attached to a polar functional head (commonly a carboxylate or sulfonate group), imparting them with both hydrophobic (fluorocarbon tail) and hydrophilic (polar head) character [

3,

4]. These compounds are often termed “forever chemicals” because of their resistance to environmental degradation and propensity to persist and accumulate in ecosystems and organisms [

5]. PFAS contamination of water resources has become a global concern, and exposure to certain PFAS is linked to adverse health effects (e.g. immune [

6], developmental [

7], and carcinogenic outcomes [

8]). Regulatory agencies are rapidly tightening drinking water standards for legacy PFAS [

9], for example, the U.S. EPA’s health advisory for PFOA and PFOS was 70 ng/L (combined) in 2016 [

10] and has since been lowered to near-zero in interim guidelines [

11]. Many jurisdictions have listed long-chain PFAS as persistent organic pollutants, and there is increasing pressure to treat PFAS-contaminated water to trace levels [

9].

Among available treatment methods, adsorption-based processes are considered the most practical for PFAS remediation in water due to their simplicity and cost-effectiveness [

12,

13]. Granular activated carbon (GAC) is the most established adsorbent and is widely implemented for PFAS removal at full scale [

14]. GAC’s porous structure (particularly high surface area and hydrophobic domains) effectively sequesters long-chain PFAS like PFOA and PFOS via hydrophobic interactions and dispersion forces [

15]. However, GAC has well-recognized limitations when it comes to short-chain PFAS (e.g. PFBA) and challenging water matrices. Short-chain PFAS exhibit significantly lower adsorption affinities on GAC [

16]. For example, adsorption coefficients decrease by about 0.5–0.6 log units for each CF2 group lost [

17], meaning PFBA (C4) sorbs an order of magnitude less than PFOA (C8) under similar conditions. In field applications, short-chain PFAS tend to break through GAC filters much earlier than long-chain analogues [

18,

19]. Moreover, natural organic matter (NOM) in water can foul GAC and competitively occupy adsorption sites, dramatically reducing GAC’s PFAS removal efficiency [

20]. This necessitates frequent media replacement or regeneration, driving up operational costs. A major drawback of GAC is that it does not destroy PFAS but merely transfers them to the solid phase. Consequently, spent GAC loaded with PFAS must be treated as a concentrated hazardous waste [

21,

22]. Additionally, the supply and cost of high-quality activated carbon are subject to market and supply chain factors [

23]. These limitations motivate the search for alternative or supplementary adsorbents that can more efficiently and sustainably capture the broad spectrum of PFAS.

Ion exchange resins with quaternary ammonium functional groups have emerged as an alternative for PFAS removal, as they can strongly bind anionic PFAS, including short chains, via electrostatic attraction [

24,

25]. Ion exchange (IX) resins typically outperform GAC for short-chain PFAS uptake [

14,

26,

27], however, IX resins are substantially more expensive and require regeneration or disposal of spent resin, which can be challenging [

24,

28,

29] (regeneration often uses aggressive chemical elution and produces a concentrated brine waste [

30]). Other treatment technologies under exploration include high-pressure membrane separations (nanofiltration/reverse osmosis) [

31,

32,

33], advanced oxidation/reduction processes [

34,

35], and novel electrochemical [

36] or sonochemical [

37] PFAS destruction methods. Yet, these approaches can be cost-prohibitive for large flows or produce secondary waste streams. In practice, many full-scale systems currently rely on adsorption processes as a stop-gap to remove PFAS from water pending more permanent solutions [

13].

Natural and engineered minerals are attractive as low-cost adsorbents for environmental remediation [

38]. Zeolites, in particular, are microporous aluminosilicate minerals with high surface area, cation-exchange capacity, and tuneable surface chemistry [

39]. Pristine (hydrophilic) zeolites have shown limited ability to adsorb PFAS because the polar, negatively charged framework preferentially holds water and repels PFAS anions. For example, natural clinoptilolite typically has sodium or calcium cations balancing its framework charge; in water these cations hydrate and the surface is dominated by hydrophilic –OH and –O- sites [

40], which do not interact favourably with PFAS. As a result, untreated zeolites or clays achieve little to no removal of PFAS like PFOA in adsorption tests. However, there is evidence that modifying the surface of these minerals can impart “organophilic” character and make them effective PFAS sorbents [

41,

42]. Previous studies on clays and silica have shown that attaching long-chain organic cations or other hydrophobic functional groups can create dual-function adsorbents that engage PFAS via both hydrophobic tail interactions and electrostatic head attraction [

43]. For instance, quaternary-ammonium modified clays (organoclays) have achieved much higher PFAS uptake than the unmodified clay [

44], and specialized swellable organically modified silica decorated with fluorophobic and cationic groups was reported to remove C4–C10 PFAS to >99% in water [

45]. These findings underscore that by tailoring the surface chemistry of a porous mineral, it is possible to strongly bind PFAS. Two key mechanisms are targeted: (1) electrostatic attraction to capture the anionic functional group (e.g. using positively charged sites), and (2) hydrophobic (or fluorophobic) interactions to capture the perfluorinated tail (e.g. via hydrophobic coatings or organo-silane grafts). An ideal adsorbent for diverse PFAS would combine both types of sites, since short-chain PFAS rely mostly on electrostatic binding (their tails are too short to drive adsorption to hydrophobic surfaces), whereas long-chain PFAS are readily taken up by hydrophobic surfaces.

Granular modified zeolites offer a potentially low-cost, regenerable adsorbent for PFAS if effective surface modifications can be achieved. Natural clinoptilolite is abundant and inexpensive compared to activated carbon or synthetic resins, and it remains stable at high temperatures [

46,

47]. This latter property is important because it opens possibilities for thermal regeneration or PFAS destruction: a spent PFAS-loaded zeolite could potentially be heated to incineration temperatures to break down PFAS and then be reused, since the mineral framework will not combust or degrade at those temperatures. In contrast, activated carbon loses a portion of its mass and structure upon thermal regeneration and can only be reactivated a limited number of cycles before it must be replaced [

48]. A thermally stable inorganic adsorbent that can be repeatedly regenerated (or even one that can be baked in a field setting to destroy PFAS and then redeployed) would greatly reduce the burden of spent media disposal. Additionally, modified zeolites could be used in tandem with carbon in a treatment train, for example, a layered filter where zeolite targets short-/mid-chain PFAS and downstream GAC polishes off the rest, optimizing overall media usage.

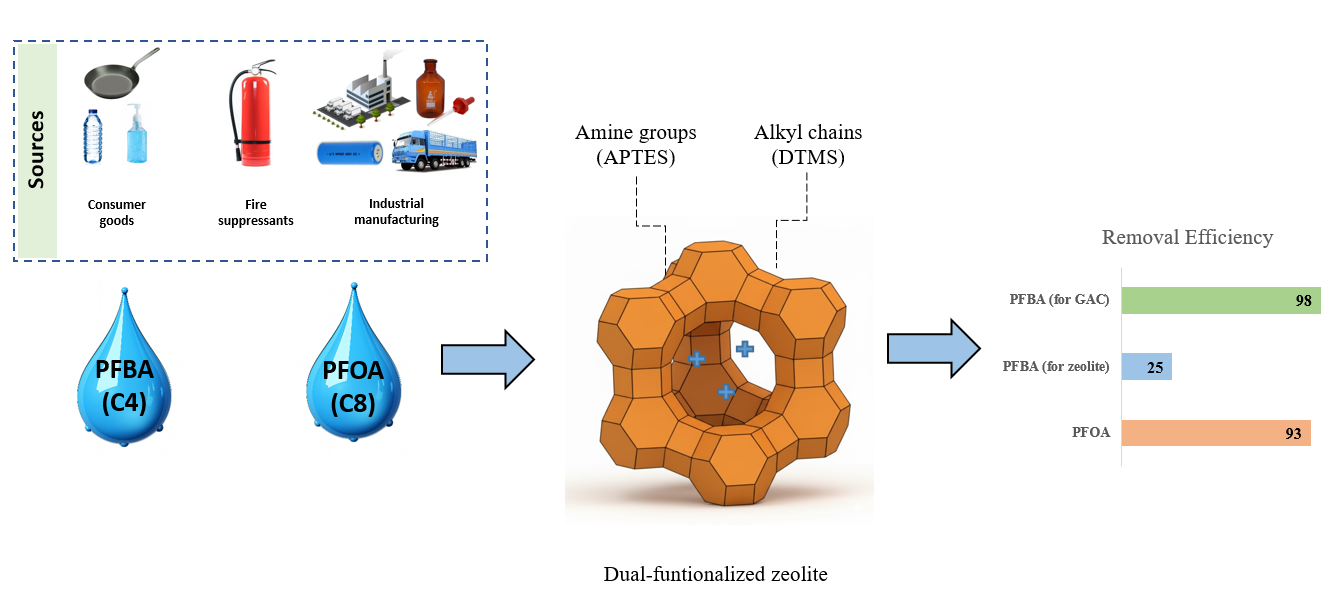

In this context, the present study investigates surface-modified natural zeolites as alternative adsorbents to GAC for PFAS removal. A suite of modified Australian clinoptilolite zeolites was developed using multiple functionalization strategies: ion exchange with cationic metals (lanthanum, iron) to introduce electrostatic sites; silane grafting with long alkyl chains (dodecyltrimethoxysilane, DTMS) to enhance hydrophobicity; grafting with amino-silane ((3-aminopropyl)triethoxysilane, APTES) to impart cationic amine functionality; co-grafting of hydrophobic and amine silanes; and graphene oxide (GO) coating to potentially increase surface area and enable π–π interactions. Two types of GACs (coal-based and coconut-based) are tested in parallel as benchmarks. The objectives of this work are to compare the PFAS adsorption performance of these modified zeolites against standard GAC, to understand how each modification influences removal of short-chain (PFBA, C4), and long-chain (PFOA, C8) to identify the most promising formulations for practical water treatment. The focus is placed specifically on PFAS carboxylates, rather than sulfonates, due to their greater resistance to adsorption by conventional adsorbents and the increasing concern surrounding short-chain variants (C4), which pose a significant treatment challenge. Batch experiments are conducted at two concentration scales: an initial high concentration screening (1.0 mg/L PFAS) to gauge adsorption capacity differences, and more environmentally relevant low concentrations (100 μg/L, or 100 ppb), including tests with single compounds and a mixture of (PFBA, C4), (PFOA, C8), and long-chain (PFTDA, C14) perfluorocarboxylates, to evaluate effectiveness under realistic conditions. PFTDA was used to check the effect of competition between long and short chain PFAS on adsorption capacity of the adsorbents, but its own adsorption was not individually measured. Through the integration of detailed adsorption data and mechanistic analysis, the study illustrates how dual functionalization of a low-cost zeolite can achieve PFAS removal performance comparable to activated carbon for longer-chain compounds, while also addressing the remaining challenges associated with short-chain PFAS and proposing potential strategies to overcome them. The potential for thermal regeneration and reuse of the zeolite adsorbents after PFAS capture is highlighted as a future direction, in line with the goal of developing sustainable PFAS treatment technology.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials and Chemicals

The target contaminants in this study were three perfluoroalkyl carboxylic acids representing a range of chain lengths: perfluorobutanoic acid (PFBA, C4HF7O2), perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA, C8HF15O2), and perfluorotetradecanoic acid (PFTDA, C14HF27O2). All three were obtained as analytical-grade solids from Sigma-Aldrich (Merck Australia) and were used without further purification. Stock solutions of each PFAS were prepared in Milli-Q deionized water. This

Figure 1 illustrates how PFAS released from consumer products, fire suppressants, and industrial activities lead to household and environmental exposures that ultimately impact multiple human organs and systems, including the immune, metabolic, liver, kidney, thyroid, and reproductive systems.

Natural zeolite (clinoptilolite-rich tuff, 0.7–1.2 mm granule size) was supplied by Zeolite Australia and used as the base substrate for modification. Prior to surface modifications, the zeolite was either used as normal-washed (NW) or given an acid-wash (AW) pretreatment. Acid washing was done by soaking the zeolite in dilute HCl (0.1–1 M) for several hours, then rinsing thoroughly with deionized water until neutral pH and drying at 105 °C. Two granular activated carbons were used as received (pre-washed with hot water by the supplier to remove fines): GAC1, a coconut shell-based GAC, and GAC2, a coal-based GAC (both provided by PET International). The GACs were included as benchmark adsorbents. Additional chemicals for zeolite modification included lanthanum (III) chloride heptahydrate (LaCl3.7H2O, Sigma-Aldrich), Ammonium iron (III) sulfate dodecahydrate ((NH4)2Fe(SO4)2·12H2O, Sigma-Aldrich), graphene oxide (GO) aqueous suspension (4 mg/mL, Sigma-Aldrich), and two silane coupling agents: APTES (3-aminopropyl triethoxysilane, 98%) and DTMS (dodecyltrimethoxysilane, 95%). All chemicals were used as received without further purification.

2.2. Zeolite Surface Modification Procedures

A variety of modified zeolite samples were prepared, targeting either increased electrostatic affinity for PFAS, increased hydrophobicity, or both. All modifications were performed on the 0.7–1.2 mm clinoptilolite granules. For samples designated “-AW”, the acid-washed zeolite was used as the starting material; “-NW” indicates normal-washed (unacidified) zeolite as the base. A summary of the sample codes is provided in

Table 1.

2.2.1. Lanthanum Coated Zeolite (AZ-La)

Strongly cationic sites were introduced on the zeolite via ion exchange with La³⁺ by mixing zeolite granules (either NW or AW) with an excess of LaCl₃ solution and stirring for 24 hours at room temperature. The ratio of solution to zeolite was chosen to target ~80% of the zeolite’s cation exchange capacity being filled by La. The slurry was then drained and the zeolite dried. Calcination was done in an electric furnace: temperature was carefully ramped (to avoid thermal shock) to 400 °C in 20 minutes and kept at this level for 2h, followed by a heating step to 750 °C in 20 minutes and kept at this level for 1h and 30 minutes to convert La into oxide/hydroxide forms on the surface. The resulting samples are denoted AZ-La-NW or AZ-La-AW (for normal- or acid-washed base, respectively).

2.2.2. Iron Treatment (AZ-Fe)

To introduce more cost-effective and environmentally friendly cationic sites on the zeolite, ion exchange was carried out using Fe³⁺. As a general method to prepare iron-coated zeolites, 12 g of dried zeolites (either NW or AW) were added to 40 ml of a 0.176 M of Ammonium iron (III) sulphate dodecahydrate and maintained on reflux at 60 °C for 6 h. Then, the zeolites were filtered and dried in an oven overnight at 110 °C. The coating solution could be used for further coating batches without going through the heating process. The resulting samples are denoted AZ-Fe-NW or AZ-Fe-AW (for normal- or acid-washed base, respectively).

2.2.3. APTES Grafting (AZ-APTES)

To provide amino functional groups on the surface, zeolite was grafted with (3-aminopropyl) triethoxysilane. Zeolite was immersed in a mix of 5% v/v APTES, 5% v/v Milli-Q water and 90% v/v Absolute ethanol. The suspension was mixed for 3-4 h. During this process, APTES molecules hydrolyse and covalently bond to surface silanol (≡Si–OH) groups. Then the samples were washed with ethanol, followed by Milli-Q water and dried. Two versions were prepared: AZ-APTES-NW and AZ-APTES-AW, corresponding to grafting on normal vs. acid-washed zeolite. The acid-washed substrate generally yields a higher grafting density because it has more -OH groups and fewer extraneous cations to interfere. APTES grafting was intended to introduce amine groups that can protonate in water (forming -NH3+) and act as fixed cationic sites to attract PFAS anions.

2.2.4. DTMS Grafting (AZ-DTMS)

To increase hydrophobicity, zeolite was grafted with dodecyltrimethoxysilane (DTMS), which carries a long alkyl chain. The procedure was like APTES grafting: zeolite was immersed in a 5% v/v DTMS in 5% v/v Milli-Q water and 90% v/v Absolute ethanol. Two versions: AZ-DTMS-NW and AZ-DTMS-AW were made. The DTMS attaches hydrophobic hydrocarbon chains onto the internal and external surface of zeolite pores, creating an organophilic surface environment. This was expected to enhance the adsorption of the fluorocarbon tails of PFAS by providing a less polar surface (somewhat analogous to carbon’s surface). However, DTMS provides no specific interaction for the PFAS head group, so by itself it was thought to mainly benefit longer-chain PFAS capture.

2.2.5. Combined APTES + DTMS Functionalization

Two strategies were explored to incorporate both amine and hydrophobic groups onto the same material to achieve synergistic effects. Co-grafting was conducted by simultaneously introducing APTES and DTMS in a single reaction step, with volume ratios of APTES:DTMS set at 1:1, 1:3, and 3:1 to adjust the relative densities of amine and alkyl functional groups. For example, in the 1:1 case, equal volumes of APTES and DTMS (each 2.5%) were combined. The co-grafted samples are denoted AZ-D: A (x:y) where D: A indicates DTMS:APTES ratio. These formulations were prepared using both NW and AW zeolite bases, resulting in samples such as AZ-D: A (1:1)-NW and AZ-D: A (1:3)-AW. In co-grafting, both silane types react simultaneously, potentially decorating each particle with a mixture of functionalities. Physical mixture of individually grafted granules: Separate batches of AZ-DTMS and AZ-APTES were first synthesized, followed by a simple 1:1 mass ratio blending of the two granule types. This yields a composite sample (denoted AZ-D+A-NW or AZ-D+A-AW) where half the grains are hydrophobic, and half are amine-functionalized. The idea was to see if a blend of functionalities (but separated on different grains) could mimic the performance of co-grafted samples or not.

2.2.6. Graphene Oxide Coating (AZ-GO)

Graphene oxide, with its high surface area and aromatic structure, was tested as a coating to potentially provide additional sorption sites (π–π interactions, hydrophobic domains). However, GO is highly oxygenated and generally negatively charged, which by itself might not favour PFAS adsorption. Graphene oxide (GO) was affixed to the zeolite using APTES as a molecular linker; initially, AZ-APTES was synthesized to introduce surface –NH₂ groups, followed by the addition of this material to an acidic aqueous GO suspension with stirring for 4 hours. The composite was filtered and dried at 60 °C, yielding AZ-GO (on an APTES-modified NW base). Visually, the zeolite turned grey black, indicating GO deposition. The GO coating was expected to increase the overall surface area and perhaps introduce some hydrophobic graphitic regions.

2.3. Batch Adsorption Experiments

All adsorption tests were carried out in batch mode. In each experiment, a measured mass of adsorbent was added to the PFAS solution, and the mixture was agitated at room temperature (~21 ± 2 °C) for 1.0 hour. All tests were conducted with continuous mixing for 1 h, although true equilibrium might take longer, 1 h gives a snapshot of performance under a reasonable contact time.

For batch experiments, the following solutions were used: (1) a high concentration PFOA solution at 1.0 mg/L (1 ppm) PFOA, prepared by dissolving PFOA in Milli-Q water; (2) individual 100 μg/L (100 ppb) solutions of PFBA and PFOA; and (3) a PFAS mixture containing 100 ppb of each of the three compounds (total PFAS = 300 ppb). PFDTA was added to study the effect of competition of very long chained PFAS in adsorption capacity of adsorbents in removal of PFBA and PFOA. These concentrations were chosen to simulate, respectively, a scenario with elevated PFAS (to probe adsorption capacity and screen materials) and a scenario reflecting contaminated groundwater or surface water in need of treatment (hundreds of ppt to low ppb range). All solutions were prepared in polypropylene or high-density polyethylene containers (to minimize PFAS adsorption to vessel walls) and were stored at fridge. No pH adjustment was made.

After 1 h, the suspensions were allowed to settle briefly (a few minutes) and then sampled. The water samples were filtered through 0.45 μm PTFE syringe filters to remove any particulates. The filtered samples were collected in polypropylene vials. Alongside each batch test, a blank control (PFAS solution with no adsorbent) was run to check for any PFAS loss to the container or filter.

2.4. Analytical Method

PFAS concentrations in filtered samples were quantified by liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) at the Western Sydney University analytical facility at Campbeltown campus. External calibration standards for each PFAS (ranging from low ng/L to μg/L) were used to ensure accurate quantification down to 1 ng/L levels. PFBA and PFOA concentrations were measured in each sample, and for mixed-analyte samples, the instrument method was optimized to minimize signal suppression or inter-analyte interference. Validation with spiked and recovered samples indicated minimal matrix effects for these PFAS within the sample matrix. Data are reported as residual concentrations (μg/L) or as % removal. No attempt was made in this study to regenerate the spent adsorbents, each test used fresh adsorbent. The potential for regenerating or reusing these materials is also considered as part of the discussion.

3. Results

3.1. PFOA Removal at High Concentration (1 ppm Screening)

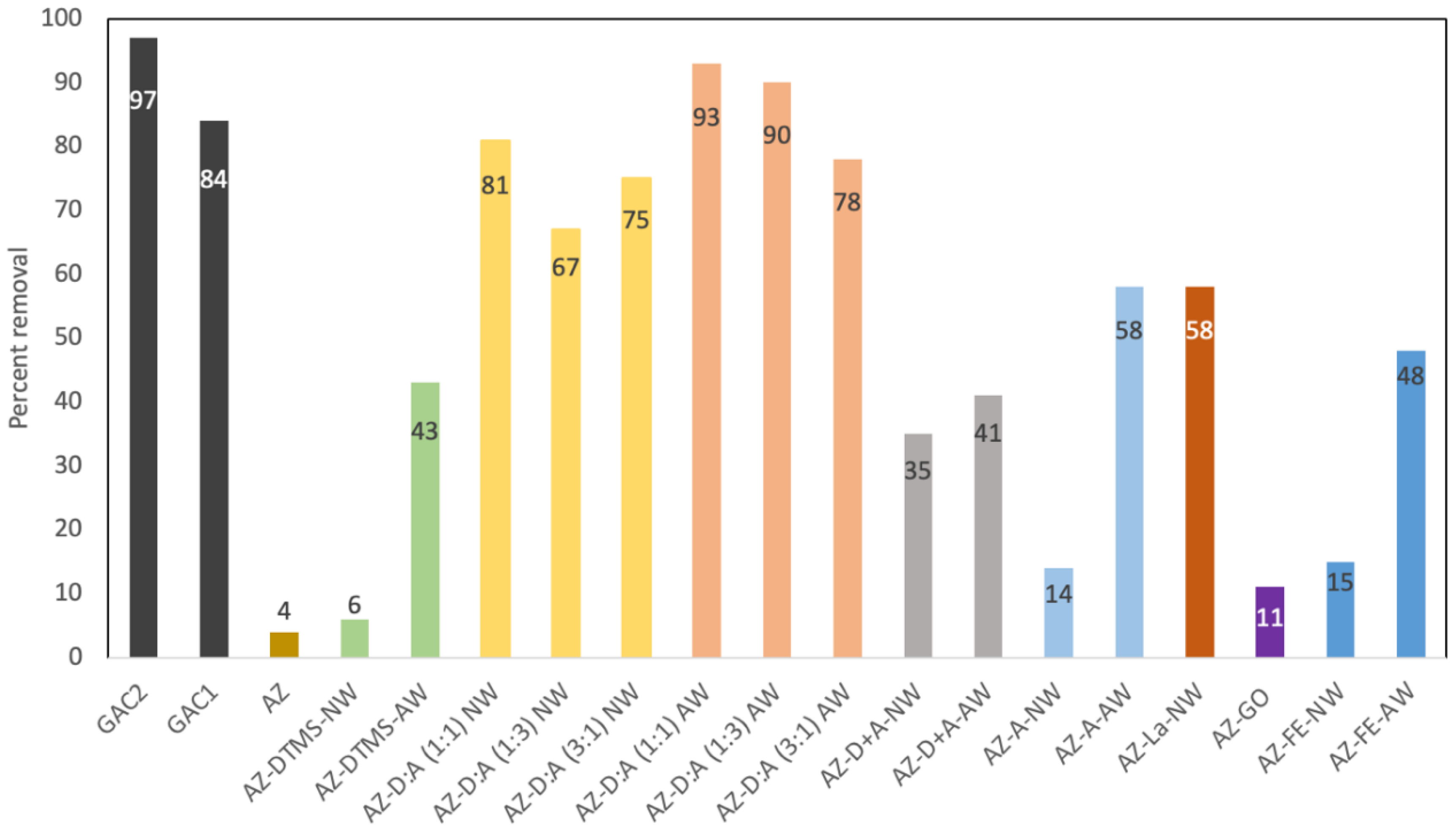

The initial high-concentration screening revealed stark differences in performance among the various adsorbents (

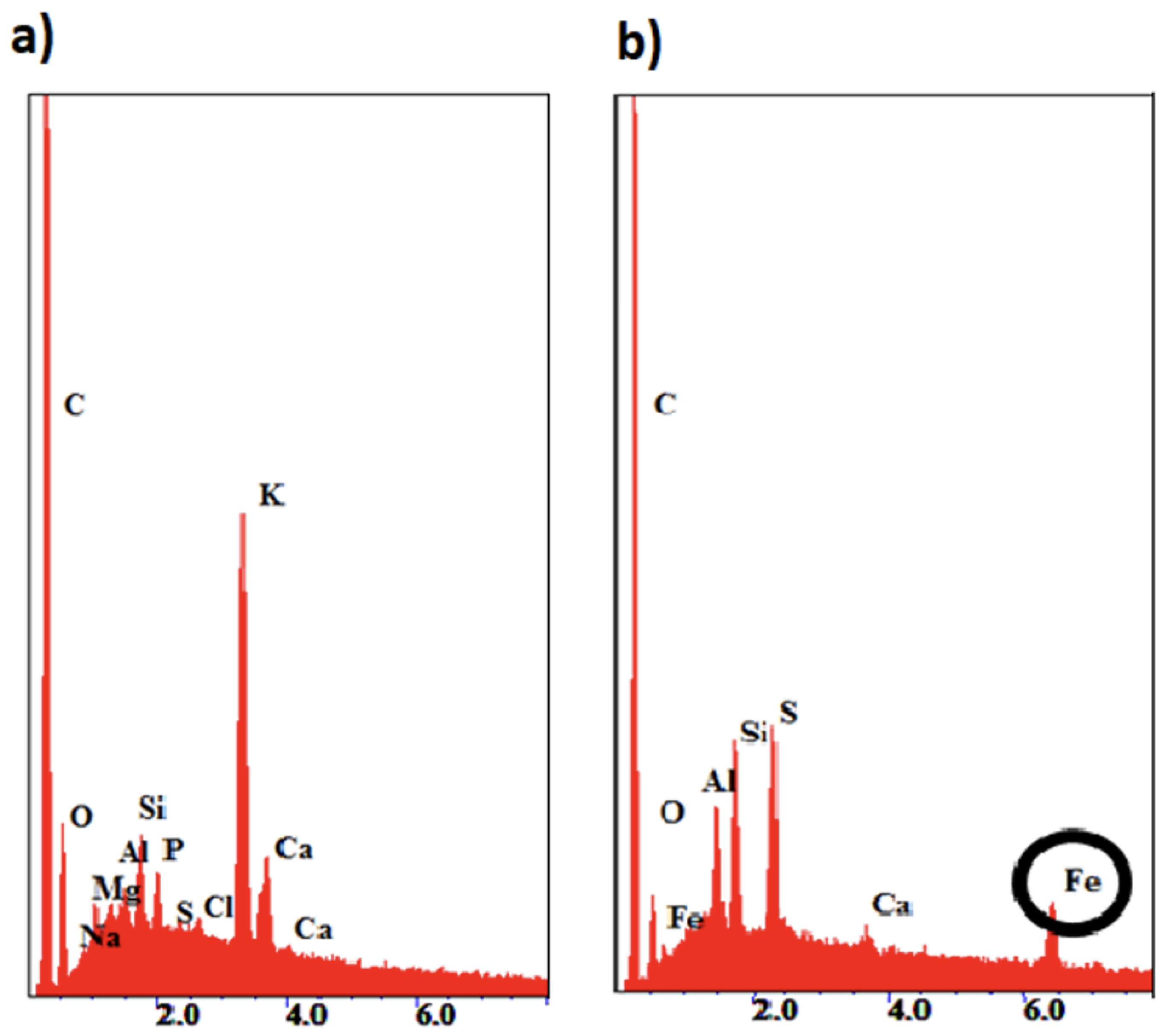

Figure 2). Unmodified natural zeolite (AZ) was essentially ineffective, removing only 4% of PFOA (final 960 μg/L from 1000 μg/L start). This was expected given the hydrophilic nature of raw zeolite – PFAS anions have little incentive to leave water and stick to the polar zeolite surface. In contrast, the GAC materials performed excellently for PFOA: the coconut-based GAC1 achieved 84% removal, and the coal-based GAC2 achieved 97% removal. The superior performance of GAC2 (coal) over GAC1 (coconut) is consistent with literature and likely due to its broader pore size distribution and possibly surface chemistry differences. Coal-based carbons often have more microporosity which facilitates diffusion of larger adsorbates and can exhibit higher adsorption capacity for PFAS [

49]. Aside from pore structure, EDX analysis of our two GAC adsorbents (

Figure 3) showed that the coal based one contains Fe, which could affect the electrostatic interaction between PFAS and GAC. Nonetheless, these findings are another testament on the importance of source of GAC for adsorption purposes. Given GAC2’s nearly complete removal of PFOA, it was used as the primary benchmark in subsequent tests.

Notably, in all cases involving zeolite, the acid-washed variants consistently outperformed the conventionally washed ones. This was expected, as acid washing not only alters the porosity of the zeolite but also enhances the surface conditions, making it more suitable for grafting organ silanes within the pores.

According to

Figure 2 , several modified zeolites approached or even equalled GAC’s performance in this 1 ppm PFOA test, underscoring the effectiveness of the surface functionalization strategies. Among the covalently grafted samples, the dual-functionalized (APTES + DTMS) zeolites were outstanding. The acid-washed zeolite co-grafted with APTES and DTMS in a 1:1 ratio (AZ-D: A (1:1)-AW) removed 93% of PFOA (final 70 μg/L). The 1:3 and 3:1 DTMS:APTES ratios on acid-washed zeolite achieved 90% and 78% removal, respectively. Even without acid pre-treatment, the co-grafted AZ-D: A (1:1)-NW removed 81%. These results show a clear synergy when hydrophobic and amine groups are combined on the same surface: neither modification alone was as effective. For comparison, DTMS-only zeolite removed a mere 6% PFOA (on NW base), improved to 43% on AW base. APTES-only removed 14% PFOA (NW), improved to 58% on AW. So, while acid-washing boosted each single-silane’s performance (by allowing higher silane loading and perhaps increasing surface area), even the best single-silane (APTES-AW, 58%) was far below the co-silane (93%). This indicates that a single type of interaction was insufficient: a purely hydrophobic surface (DTMS-only) does not grab the anionic head of PFOA, and a purely amine-modified surface (APTES-only) offers electrostatic attraction but provides limited hydrophobic domain to accommodate the fluorinated tail. On the dual-modified surfaces, a PFOA molecule can simultaneously engage with a positively charged amine (for its –COO- group) and with adjacent C12 chains (for its CF7 tail), resulting in a much stronger overall adsorption (a “bidentate” binding in a sense). This aligns with the design principle reported in other studies that dual functionality is key for short-to-mid chain PFAS sorbents [

50,

51].

Interestingly, as shown in

Figure 2, the physical mixture of APTES-modified and DTMS-modified zeolite grains (AZ-D+A) exhibited significantly lower performance compared to the co-grafted counterpart. The 1:1 physical mixture on NW base achieved only 35% PFOA removal (and 41% when using AW-modified components). This confirms that the cooperative binding requires co-localization of functionalities on the same particle, not just the same system. In the mixed-grain system, a PFOA might interact with one particle’s hydrophobic surface or another’s amine site, but it cannot anchor strongly to either since the complementary interaction is missing on each particle and the PFAS may shuttle between particles without being firmly captured. This result underscores the advantage of chemical bonding of multiple functional groups to the same adsorbent surface for PFAS capture.

The lanthanum and iron modified zeolites showed moderate success in the 1 ppm PFOA test. AZ-La-NW removed 58% of PFOA. La³⁺ sites are presumed to bind PFOA through electrostatic interactions or ligand exchange mechanisms, potentially forming inner-sphere La–carboxylate complexes, consistent with lanthanum’s known affinity for carboxylic and phosphoric functional groups [

52,

53,

54]. The fact that 58% removal was achieved is promising (significantly better than raw 4%), but it also indicates many PFOA molecules remained unabsorbed, likely because once the limited number of La sites were occupied, additional PFOA saw a mostly hydrophilic surface. AZ-Fe was less effective: AZ-Fe-NW removed only 15%, while AZ-Fe-AW reached 48%. The improvement with acid-washing suggests higher Fe loading or better distribution in AZ-Fe-AW as well as introduction of higher surface area, but even 48% removal indicates Fe provided a weaker adsorption enhancement than La.

The graphene oxide-coated zeolite (AZ-GO) was largely ineffective, removing only 11% of PFOA. This result is telling, increasing surface area with a high-surface-area material like GO does not help if the surface chemistry is not suited to PFAS. GO is highly oxidized and hydrophilic [

55], it likely introduced more negative charges (carboxylates on GO) and competed with the zeolite surface for PFAS. Literature reports have found GO alone is a poor sorbent for PFAS, but GO functionalized with cationic surfactants can be excellent [

56,

57]. In our case, without an added surfactant on GO, the GO layer was not beneficial. In fact, it could block some zeolite pores and slightly worsen performance relative to raw zeolite.

To summarize the 1 ppm screening: Coal-based GAC2 was the top performers (~97% PFOA removal). The APTES+DTMS co-grafted zeolites (especially on acid-washed base) closely followed, achieving 78–93% removal depending on the ratio. Middle-tier were La-exchanged zeolite (58%) and the best single-silanes (43–58% for DTMS-AW and APTES-AW). The poorest were raw zeolite (4%), GO-coated (11%), and DTMS-NW (6%). These results clearly indicate which modifications significantly enhance PFAS uptake. Based on these findings, candidate materials were narrowed for further investigation at low PFAS concentrations.

3.2. PFAS Removal at 100 μg/L – Single-Compound Tests

Adsorption performance was subsequently evaluated for each PFAS individually at an initial concentration of 100 μg/L. Nine adsorbent systems were tested in these single-solute experiments: (1) GAC2 (coal GAC, baseline carbon), (2) AZ (raw) (3) AZ-DTMS-NW, (4) AZ-D:A(1:1)-NW, (5) A-D:A(1:3)-NW, (6) AZ-D:A(3:1)-NW, (7) AZ-A-NW, (8) a AZ-La-NW, and (9) AZ-Fe-NW. This selection covers the range from unmodified to various modifications; note that The NW base was selected for modified zeolite samples in this phase due to practical considerations, as the acid-washing process would introduce additional preparation steps, increasing both cost and safety concerns. Each adsorbent was used in 100 ppb PFAS solutions for 1 h.

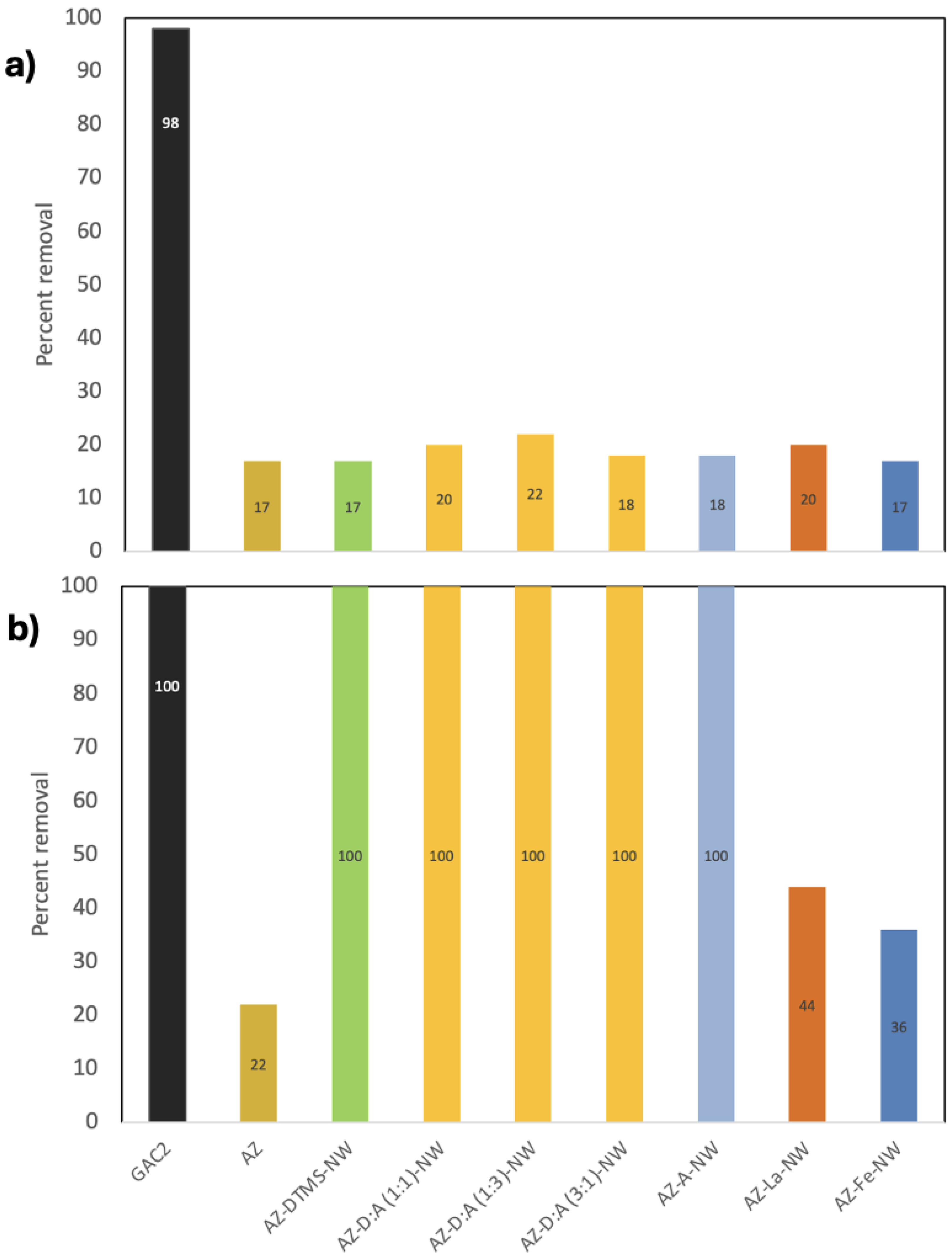

Figure 4 presents the removal percentages for PFBA (C4) and PFOA (C8) by each selected adsorbent.

Several important trends are evident from

Figure 3 (numerical values are also discussed below). PFBA proved the most difficult for the adsorbents to remove. Raw zeolite captured only 17% of PFBA. Neither Fe nor La modification made any meaningful difference: AZ-Fe removed 17%, AZ-La 20%, essentially within error of the raw zeolite’s performance. In other words, introducing positive charges via Fe or La on zeolite did not measurably improve PFBA uptake at 100 ppb. This result was initially unexpected, given the hypothesis that electrostatic attraction would play a crucial role in short-chain PFAS adsorption. However, the extreme hydrophilicity and short tail length of PFBA appear to prevent effective adsorption, even when cationic sites are introduced on an otherwise hydrophilic mineral surface, indicating a strong preference for remaining in the aqueous phase. Organosilane-functionalized zeolites exhibited limited PFBA removal; for example, AZ-APTES-NW and AZ-D: A (x:y)-NW achieved removal efficiencies in the range of 17–22%, comparable to that of AZ-La under the tested conditions. Essentially, no zeolite-based formulation in this study achieved more than 25% removal of PFBA at 100 ppb. By stark contrast, the activated carbon had a very high removal for PFBA under these batch conditions. GAC (coal) removed 98% of PFBA, reducing it from 100 μg/L to 2 μg/L. This is an interesting result because it’s known that in continuous flow systems, short chain PFAS often breaks through GAC quickly [

16]; However, in the batch test, the use of a high GAC dose (2.5 g/L) combined with adequate contact time enabled GAC to effectively adsorb the 100 μg/L of PFBA present, functioning as a near-complete removal agent. This suggests that GAC can take up PFBA given enough adsorbent and time, but its capacity for PFBA is much lower than for PFOA, so in flow systems with finite bed volumes, PFBA will exhaust the carbon faster.

For PFOA at 100 ppb, GAC again showed essentially complete removal. The raw zeolite removed only 22% of PFOA, confirming its poor affinity for PFAS in native form. Importantly, the modifications on zeolite made a bigger difference for PFOA than they did for PFBA. AZ-La-NW removed 44% of PFOA (double that of raw) and AZ-Fe-NW about 36%. This indicates that electrostatic attractions do contribute for PFOA: introducing La3+ (or to a lesser extent Fe) can pull some PFOA out of solution. PFOA’s larger perfluorinated tail likely also benefits slightly from any hydrophobic patches on the zeolite or from being held at the cation site. However, the metal-exchanged zeolites still fell far short of carbon or of the organosilanes. In separate tests (and in the PFAS mixture, discussed next), the APTES, DTMS, and dual-silane modified zeolites achieved 100% removal of PFOA at 100 ppb comparable to GAC. The fact that amine-silane modifications nearly quadrupled PFOA uptake on zeolite compared to raw sample, whereas PFBA uptake stayed low, reinforces that the mechanism for PFOA involves both tail and head interactions that the amine+hydrophobic surface can provide, while PFBA’s very weak adsorption isn’t solved by these relatively mild functional groups.

The single-solute tests highlight the chain-length-dependent adsorption behaviour: PFBA (C4) is barely adsorbed by anything except a high dose of GAC and PFOA (C8) is moderate-to-strongly adsorbed by tailored zeolites and strongly by GAC. GAC, being a predominantly hydrophobic adsorbent, shines for C8, and can manage C4 only when present in large excess. The modified zeolites can partly bridge the gap for C8 by providing some hydrophobic and electrostatic sites, but for C4 they still lack the strong binding needed.

3.3. PFAS Removal from a Mixed Solution (Competitive Effects)

In real-world waters, PFAS do not exist in isolation; mixtures of various chain lengths are common [

58]. To evaluate competitive adsorption behaviour, the adsorbents were tested in the presence of a mixture containing PFBA, PFOA, and PFTDA, each at 100 μg/L, resulting in a total PFAS concentration of 300 μg/L. The selected adsorbents for this mixture test were similar to the previous section, and the results are presented in

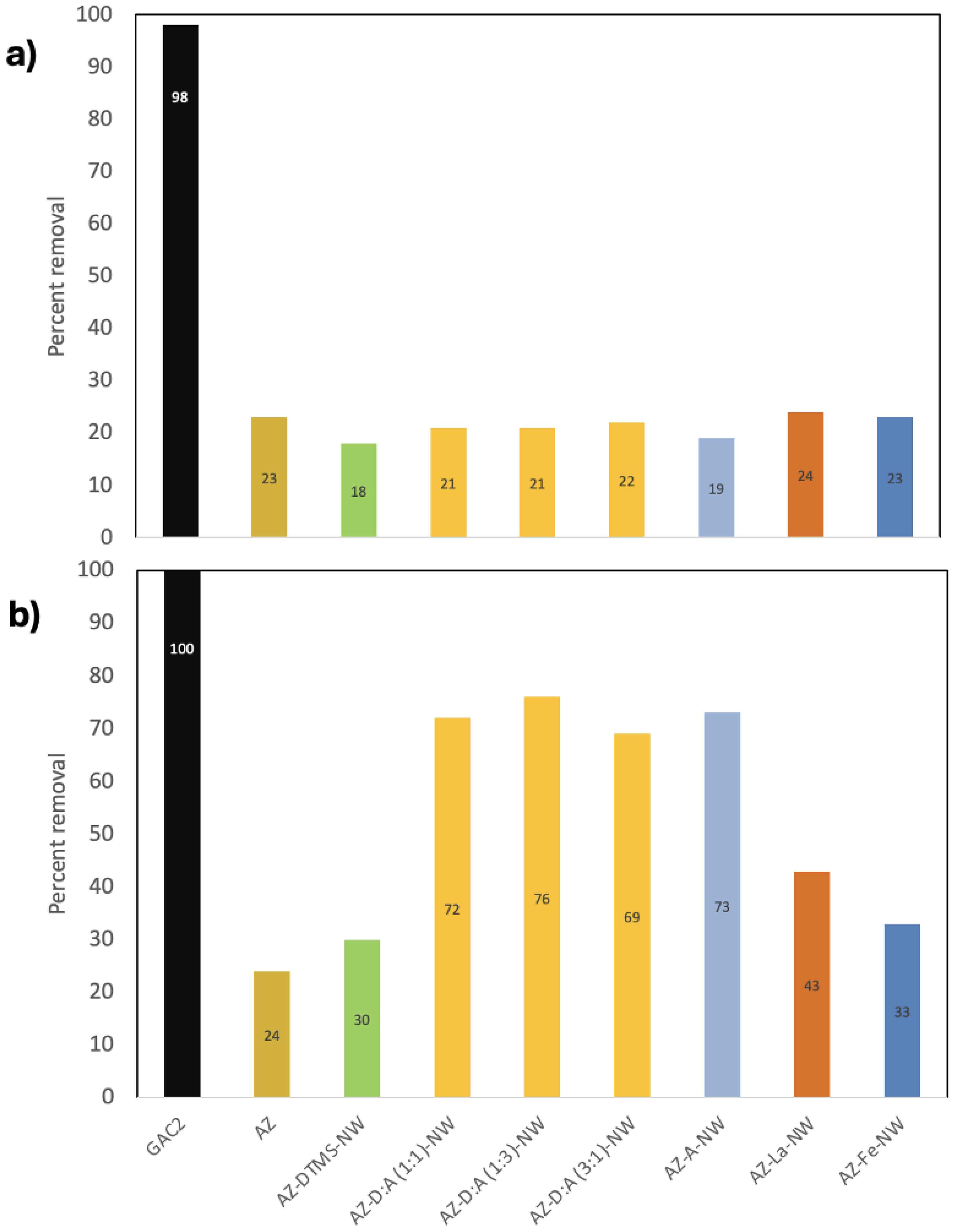

Figure 5.

For PFBA in the mixture, the presence of the other PFAS did not significantly change its uptake on any of the zeolites. All the modified zeolites still showed very low PFBA removal: for example, AZ-Fe 23%, AZ-La 24%, AZ-DTMS 18%, AZ-APTES 19%, AZ-DTMS+APTES mixtures 21–22%. These values are within a few percent of those observed in single-solute tests, with some slightly elevated results likely attributable to experimental variability or minor co-solute interactions. In other words, PFBA remained largely unabsorbed in the presence of PFOA and PFTDA, it was neither helped nor significantly hindered by them, because none of the zeolite-based materials had strong affinity for PFBA to begin with. The GAC2 in the mixture still removed ~98% of PFBA (final ~1.6 μg/L), essentially the same as it did in single solute, indicating the GAC’s capacity was not yet challenged by the added PFOA/PFTDA at these concentrations. Thus, at least in this short-term batch context, PFBA did not exhibit competitive displacement by the longer PFAS on GAC. In a continuous system, one would expect PFBA to break through earlier, but in batch with excess carbon, everything was captured. The take-home point is that none of the tested zeolite modifications provided a viable improvement for short-chain PFAS in mixture, reinforcing that a fundamentally different functional group (e.g. strong quaternary ammonium, or specialized binding chemistry) would likely be needed to remove PFBA from water. The short-chain PFAS is likely too hydrophilic and molecularly compact to be effectively captured by the moderate amine and hydrophobic functional groups introduced.

For PFOA in the mixture, more discernible differences emerged among the adsorbents, but the trends mostly mirrored the single-solute results. GAC2 again removed 100% of PFOA in the mixture (no detectable PFOA remaining). Raw zeolite removed 24% of PFOA in the mixture, nearly identical to its single-solute performance (22%), indicating no significant change. The DTMS-only zeolite (AZ-DTMS-NW) achieved 30% removal, slightly higher than raw zeolite, suggesting a modest enhancement from added hydrophobicity, but this represented a 70% decrease compared to its performance in the single-solute system. The APTES-only zeolite (AZ-APTES-NW) removed 73% of PFOA in the mixture, reflecting a 30% reduction from its single-solute value. A similar 30% drop in removal efficiency was observed for all co-grafted DTMS+APTES samples. All co-grafted samples showed similar PFOA removal performance to the APTES-only sample, suggesting that the hydrophobic domains were primarily occupied by the longer-chain PFTDA. Consequently, electrostatic interactions, driven by the amine functionality, became the dominant mechanism for PFOA adsorption. The addition of hydrophobic chains from DTMS did not significantly enhance PFOA uptake in the mixed system, likely because the amine-modified surface (with propyl chains from APTES) was already sufficient to accommodate PFOA at 100 ppb. Furthermore, PFTDA likely occupied the available hydrophobic sites due to its stronger affinity for such domains, while the amine sites, being unique to APTES, remained accessible for PFOA. As a result, amine-functionalized zeolites (APTES and APTES+DTMS) maintained high PFOA removal (70–75%) even in the presence of other PFAS, whereas samples lacking amine groups (raw, DTMS-only, Fe-, and La-modified) showed significantly lower performance (24–43%). Notably, La- and Fe-zeolites removed 43% and 33% of PFOA, respectively, which closely matched their single-component values (44% and 36%), indicating minimal competitive suppression. These results highlight that the presence of amine groups, rather than additional hydrophobic chains, is the key factor in PFOA adsorption under mixed PFAS conditions.

3.4. Mechanistic Insights and Discussion of Adsorbent Performance

The experimental results above provide a basis to analyse the mechanisms by which each modification influences PFAS adsorption, and why certain adsorbents succeeded or failed for PFAS.

Raw clinoptilolite zeolite was virtually ineffective for PFBA and PFOA. This aligns with the surface chemistry of natural zeolite: the framework is aluminosilicate with exchangeable cations (Na+, Ca2+, etc.), which means the surface is polar, often negatively charged (from deprotonated silanol or Al-O− sites), and hydrophilic [

59]. PFAS anions in water remain hydrated and are electrostatically repelled by the like-charged sites on zeolite. There are no organic/hydrophobic regions on the raw zeolite for the PFAS tail to stick to, except perhaps defect siloxane patches or internal pores that might fit part of a PFAS molecule [

60]. GAC, in contrast, offers a highly hydrophobic, high-surface-area substrate to which PFAS, especially long ones, sorb strongly via London dispersion forces and hydrophobic partitioning [

4]. GAC’s pores create deep potential wells for organic molecules [

61]. However, GAC’s lack of polar or charged sites means short-chain PFAS (which remain hydrated and don’t gain much from van der Waals interactions) are not strongly held [

16]. Batch testing demonstrated that GAC can remove PFBA at sufficiently high doses; however, under flow conditions, PFBA is expected to exhibit early breakthrough due to its weak adsorption affinity. Thus, raw zeolite requires surface modification to be PFAS-active, whereas GAC is inherently active for longer PFAS but might need augmentation for short ones.

DTMS was grafted to introduce long hydrocarbon chains within the zeolite pores and on external surfaces, creating a fluorophobic and hydrophobic interior. The modest outcome, only slight improvement for PFOA after acid-wash (43% vs 4% raw), and essentially no help for PFBA, reveals the limitations of purely hydrophobic modification. Several factors can be deduced: (1) Incomplete surface coverage and steric effects: on the NW zeolite, DTMS grafting was probably sparse (hence 6% removal, basically raw). Acid-washing improved salinisation density, but still likely left many polar patches or narrow pores where PFAS couldn’t enter due to grafting or still felt polar interactions. The presence of residual charge could still repel PFAS even if nearby areas are hydrophobic. Also, grafting long chains in micropores can reduce pore volume and even obstruct PFAS access. (2) No electrostatic attraction: DTMS provides no positive charge, so PFAS anions are not drawn in; adsorption relies solely on the tail’s affinity for the surface. For PFOA’s C8 tail, this hydrophobic driving force is moderate but not overwhelmingly high in water (especially with only 1 h contact). For PFBA’s C4 tail, it’s very weak, so PFBA saw no benefit from DTMS. (3) Orientation and solvation: a PFAS molecule at a hydrophobic surface still needs to shed water from its headgroup, which is unfavorable if no polar interaction compensates. So PFOA might stick by its tail to a DTMS-coated spot but leave its head solvated in water, resulting in only a loose association that could easily desorb. This would manifest as low net removal. Overall, hydrophilization alone was insufficient. The DTMS-coated zeolite functioned analogously to a low-surface-area activated carbon, providing insufficient binding strength for PFOA and exhibiting negligible effectiveness for PFBA.

APTES grafting was intended to introduce amine groups that could become protonated and act as anion-exchange sites for PFAS. On acid-washed zeolite, APTES made a significant difference: PFOA removal went from 4% to 58% at 1 ppm, and from 22% to 73–100% at 100 ppb (depending on conditions). This indicates that electrostatic attraction was indeed activated, the –NH3+ groups can pull the PFOA anion out of solution. At pH ~7, not all APTES groups are protonated (primary amine pK_a ~9–10, but on a surface, it could be lower), so perhaps a fraction are in –NH3+ form [

62]. Those that are protonated provide sites akin to weak anion-exchange resins. Additionally, even the unprotonated –NH2 can interact via H-bond [

63] or dipole with the PFAS head [

64], and the propyl chain adds a little hydrophobic moiety. All these contribute to improved PFOA adsorption. The APTES-NW (no acid wash) was less effective (14% at 1 ppm PFOA), likely because fewer amines grafted. Yet at 100 ppb, APTES-NW did reach 100% for PFOA, showing that at low concentration even a sparsely grafted amine surface can capture a lot of PFOA, possibly because PFOA concentrates on the few amine sites available. For PFBA, APTES gave only a minor uptick (raw 17% → APTES 20% at 100 ppb), meaning a weak base anion exchanger is not enough for PFBA in the presence of water. PFBA’s carboxylate might not bind strongly to a protonated primary amine (compared to a quaternary ammonium on a resin) and the short tail gives no hydrophobic assistance. Also, if many amines are neutral at pH 7, their benefit for PFBA is further limited. In summary, APTES provided moderate anion-exchange functionality and slight hydrophobicity, which was quite effective for PFOA (C8) but still inadequate for PFBA (C4). This aligns with expectations: a stronger fixed cation (like a quaternary amine) might be needed to snag PFBA, whereas the weaker, pH-dependent APTES works for mid-chain but struggles for the shortest chain.

The co-grafted APTES+DTMS zeolites were among the top performers, achieving PFOA removal on par with GAC in some cases. At 1 ppm, AZ-D: A (1:1)-AW got 93% vs GAC’s 97%, a remarkable result for a mineral adsorbent. This confirms the synergy of dual functionalization. PFOA can simultaneously interact with an –NH3+ and a hydrophobic chain on the same surface, greatly stabilizing its adsorption. The ratio experiments indicated that the balance of functionalities was best: the 1:1 ratio outperformed 3:1 or 1:3 on AW base. Excess amines (1:3, APTES-rich) may crowd the surface with polar groups and not enough hydrophobic domains for tails, while excess silane (3:1) may leave too few cationic sites to anchor the heads. The physical mixture (separate APTES and DTMS grains) underscored that co-location is necessary – as discussed, the mixture was much less effective (35% vs 81% for co-grafted NW in 1 ppm test). At 1 ppm, clearly the DTMS was beneficial (APTES-AW 58% vs APTES+DTMS-AW 93%). Likely, as the surface loading of PFOA increases, having long alkyl chains helps to accommodate and maybe even cooperatively organize a layer of PFAS (similar to hemi-micelle formation on cationic surfactant-coated surfaces [

65]). Nevertheless, dual-grafted zeolite nearly matched GAC for PFOA, indicating that the right combination of functional groups can transform a cheap mineral into a PFAS adsorbent of comparable efficacy to activated carbon for long/mid-chain PFAS. As expected, even the dual-functional surface did not effectively address PFBA, reinforcing the necessity of incorporating a strong anion-exchange functionality. Nonetheless, for PFOA- and PFOS-type contaminants, the combination of hydrophobic and cationic sites proved highly effective.

These aim to utilize electrostatic binding via multivalent cations. The results for PFOA were moderate (La ~44%, Fe ~36% at 100 ppb) and negligible for PFBA, so what is happening at those La/Fe sites? Lanthanum, a hard Lewis acid, can form complexes with carboxylate groups; PFOA is likely to coordinate to La³⁺ at the surface, potentially in a bidentate manner involving both oxygen atoms of the carboxylate group [

66]. This would explain the roughly 2 times increase in PFOA uptake vs raw: each La provides a high-affinity site, but once those are filled, additional PFOA won’t stick elsewhere. For PFBA, maybe the interaction is too weak. The fact that in the mixture, La-zeolite didn’t preferentially take PFBA over PFOA suggests La sites actually preferred PFOA. Fe-treated zeolite gave smaller improvements, probably Iron forms nano-Fe (OH)3 on zeolite. Fe(OH)3 has a point of zero charge ~8, so at pH ~7 it’s near neutral to slightly positive [

67], weaker attraction than a trivalent cation like La3+. So, Fe provided fewer effective sites. In any case, La3+ exchange on zeolite showed that adding strong cationic sites can improve PFAS uptake (especially for mid-chain), but by itself it’s not enough to rival carbon or amine-functionalization. The La/Fe results indicate that simple metal exchange facilitates moderate PFAS removal, likely via outer-sphere or inner-sphere interactions between PFAS molecules and metal sites; however, these sites function more as isolated “sticky spots” on an otherwise non-adsorptive surface.

The GO-coated zeolite result (11% PFOA removal) highlights that increasing surface area alone is not a solution if surface chemistry is wrong. GO has many hydrophilic oxygen groups; it essentially made the zeolite even more hydrophilic (and dark coloured). PFAS likely remained in water rather than adsorb to GO. In the composite, GO was attached via APTES without the addition of any supplementary hydrophobic cation, which likely explains its lack of effectiveness. If anything, GO might have covered up some of the APTES sites too (though presumably APTES was mostly at the zeolite surface and GO layered on top). The lesson is high surface area carbons or graphene need proper functionalization to work for PFAS; just making tiny particles or sheets won’t adsorb PFAS if those surfaces behave like polar or charged entities that compete with water.

3.5. Implications for Practical Use and Regeneration

The promising results of the modified zeolites, especially the dual-silane ones, suggest that natural zeolite can be turned into an effective PFAS adsorbent for longer-chain PFAS. This is significant given the low cost and wide availability of natural zeolites. If the modification process is scalable, one could produce large quantities of modified zeolite media for use in PFAS remediation. The use of silane reagents (APTES, DTMS) and organic solvents in laboratory-scale modifications introduces added cost and necessitates appropriate waste solvent management. For scale-up, alternative approaches such as aqueous-phase silane deposition, utilization of more cost-effective silanes, or in-situ polymerization on zeolite surfaces could be explored to improve economic and environmental feasibility. APTES/DTMS grafts are covalently bound, likely robust during use (Minimal leaching of silanes is expected after proper curing).

One key advantage of inorganic media like zeolite is the ability to handle thermal regeneration. Spent GAC is often thermally reactivated, essentially baking off organics and restoring pore structure, though PFAS require high temperatures to destroy (and can off-gas hazardous fluorinated compounds if not fully destroyed). Zeolite, being mineral, could potentially be regenerated by heating to high temperatures to desorb PFAS. In fact, zeolites can withstand >500 °C easily; PFAS will decompose at high temperatures (~300–600 °C for breaking C–F bonds, often requiring >1000 °C for complete mineralization). If done in a controlled furnace (with off-gas treatment), one could incinerate PFAS-laden zeolite and reuse the zeolite since it won’t burn. One major limitation is that functional groups such as silanes and amines are prone to thermal degradation or combustion during regeneration, thereby restoring the zeolite to its unmodified state. However, perhaps a moderate-temperature bake (e.g., 300 °C) could desorb PFAS (as they have relatively low boiling points or will degrade) without fully destroying the silane layer, this would require investigation. Alternatively, chemical regeneration could be attempted: for instance, flushing a column with a solvent like methanol or an alkaline solution might strip off PFAS into a smaller volume for disposal. Ion-exchange resins often use high-salt plus alcohol mixtures to regenerate PFAS, but it’s tricky for long-chain PFAS. Given the lower cost of the modified zeolites, a single-use approach followed by incineration of the spent media may also be a viable disposal strategy. Still, a reusable adsorbent is preferable if possible. The feasibility of regenerating PFAS-laden media is an ongoing challenge in the field, often, spent media are just incinerated in hazardous waste facilities. The thermal stability of zeolite at least gives it a better chance to be regenerated than polymeric resins (which can’t handle high heat) or even GAC (which lose mass when burned).

4. Conclusions

This work demonstrates that surface functionalization can transform natural clinoptilolite zeolite from an ineffective sorbent into a highly effective PFAS adsorbent for certain PFAS. The most successful approach was dual functionalization with APTES (amine silane) and DTMS (hydrophobic silane) on acid-washed zeolite, which yielded PFOA removal efficiencies more than 90% at 1 mg/L – on par with a high-performance activated carbon. This superior performance confirms a synergistic binding mechanism: the co-grafted amine groups provide strong electrostatic attraction for the PFAS head, while adjacent alkyl chains offer hydrophobic domains for the fluorinated tail, together enabling much stronger adsorption than either functionality alone. Single-modification zeolites (only APTES or only DTMS) and metal-exchanged zeolites (La- or Fe-treated) showed only moderate improvements (typically 15–58% PFOA removal in 1 mg/L tests) and could not match the dual-silane’s effectiveness. Similarly, a graphene oxide-coated zeolite did not significantly adsorb PFAS, likely due to GO’s intrinsic hydrophilicity. These findings underscore that dual surface functionality is key to adsorbing mid- to long-chain PFAS on inorganic substrates, validating the dual-tail+head interaction design principle for PFAS sorbents.

Despite the impressive performance of PFOA, the modified zeolites in this study exhibited little affinity for short-chain PFBA. Neither the introduction of cationic sites (La³⁺, Fe²⁺/Fe³⁺) nor the addition of moderate amine/hydrophobic groups was sufficient to capture PFBA, with removal efficiencies generally below 25% at 100 µg/L. In contrast, the GAC benchmark was able to uptake nearly all PFBA in batch tests (due to the high adsorbent dose and contact time), highlighting the short-chain adsorption gap. This outcome indicates that current modifications, while effective for longer PFAS, do not provide the necessary binding force for the highly water-soluble short-chain PFAS. Future research should explore stronger ionic functional groups or tailored binding chemistries (for example, quaternary ammonium functionalization or ion-exchange polymers on the zeolite) to enhance short-chain PFAS capture. Additionally, evaluating these modified zeolites in continuous flow systems and investigating regeneration methods will be important for practical deployment. The high thermal stability of the clinoptilolite base offers a unique opportunity for thermal regeneration or even onsite incineration of spent media to destroy captured PFAS, potentially allowing the mineral to be re-functionalized and reused.