1. Introduction

Cloud-native software development has emerged as the dominant paradigm for building scalable, resilient applications in modern enterprise environments. Organizations increasingly adopt microservices architectures, containerization, and Kubernetes orchestration to achieve operational agility and resource efficiency [

1]. However, developing cloud-native applications remains a complex undertaking that requires expertise across multiple domains, including API design, backend and frontend development, infrastructure-as-code (IaC), testing, and container orchestration.

The advent of large language models (LLMs) has catalyzed significant progress in automated code generation. Models such as GPT-4 [

2] and Claude [

3] have demonstrated remarkable capabilities in synthesizing code from natural language descriptions, achieving approximately 90% accuracy on function-level benchmarks like HumanEval [

4]. These advances have spawned a new generation of AI-powered development tools, from code completion assistants to autonomous coding agents.

Despite these achievements, a substantial gap remains between generating isolated code snippets and delivering production-ready cloud-native applications. Real-world software development requires intricate coordination across design, implementation, testing, and deployment phases, each demanding specialized knowledge and iterative refinement. Existing LLM-based approaches typically address only fragments of this workflow, leaving developers to manually integrate outputs and resolve inconsistencies.

Recent work on multi-agent systems offers a promising direction for addressing this challenge. Frameworks such as MetaGPT [

5] and ChatDev [

6] have demonstrated that assigning specialized roles to multiple LLM agents can improve coherence and reduce errors in software generation tasks. Similarly, AutoGen [

7] provides infrastructure for composing conversable agents that collaborate through natural language. However, these systems have not been systematically evaluated on cloud-native development workflows that span from requirements to deployment. Unlike MetaGPT and ChatDev, which primarily target general software generation, our work focuses on end-to-end cloud-native workflows—including IaC and Kubernetes deployment—evaluated on a benchmark specifically designed for this setting.

This paper makes three primary contributions. First, we present CloudMAS (Cloud-native Multi-Agent System), an end-to-end framework that orchestrates specialized agents to transform natural language requirements into deployable microservices. Our architecture introduces novel mechanisms for inter-agent communication, conflict resolution, and responsibility attribution when failures occur. Second, we construct CloudDevBench, a benchmark dataset comprising 50 development tasks derived from real open-source projects, complete with requirement specifications, reference implementations, test suites, and deployment validation scripts. Third, we conduct comprehensive experiments comparing CloudMAS against single-LLM and single-agent baselines, demonstrating significant improvements across compilation success, test pass rates, and deployment success metrics. The CloudDevBench benchmark and evaluation framework are publicly available to facilitate future research.

2. Related Work

2.1. LLM-Based Code Generation

The application of large language models to code generation has progressed rapidly since the introduction of Codex [

4]. Contemporary models achieve impressive performance on standard benchmarks, with GPT-4 and Claude 3.5 both attaining approximately 90% pass@1 on HumanEval [

2,

3]. These benchmarks evaluate function-level code synthesis, where models generate implementations from docstrings and unit tests validate correctness.

Beyond function-level benchmarks, more challenging evaluations have emerged to assess repository-level code generation capabilities. SWE-bench [

8] presents models with real GitHub issues and measures their ability to generate correct patches. Top-performing agents currently resolve approximately 45% of verified issues, indicating substantial room for improvement on complex software engineering tasks. Other benchmarks including MBPP [

9], BigCodeBench [

10], and LiveCodeBench [

11] provide complementary perspectives on code generation quality.

2.2. Multi-Agent Systems for Software Development

The multi-agent paradigm has gained traction as a means to leverage the strengths of LLMs while mitigating their limitations. MetaGPT [

5] encodes standardized operating procedures (SOPs) into prompt sequences, enabling agents with specialized roles to verify intermediate results and reduce cascading errors. The framework achieves 85.9% pass@1 on HumanEval through its assembly-line approach to task decomposition.

ChatDev [

6] simulates a virtual software company with agents assuming roles such as CEO, programmer, and tester. Communication proceeds through structured chat chains that guide design, coding, and testing phases. AgentCoder [

12] introduces a three-agent framework comprising programmer, test designer, and test executor agents, demonstrating improved code quality through iterative feedback. The Self-Organized Agents (SoA) framework [

13] addresses scalability by automatically multiplying agents based on problem complexity.

AutoGen [

7] provides a general-purpose framework for building multi-agent applications through conversable agents that can integrate LLMs, humans, and tools. The framework supports flexible conversation patterns and has been applied to domains including mathematics, coding, and operations research. Recent extensions enable event-driven architectures and cross-language support.

2.3. Cloud-Native Development Automation

Automation of cloud-native development has received growing attention in both industry and academia. The DORA metrics [

14] establish benchmarks for measuring software delivery performance, including deployment frequency, lead time, and change failure rate. Platform engineering has emerged as a discipline focused on providing developers with self-service capabilities for building and deploying applications.

Tools such as AWS Kiro and various AI-powered DevOps assistants have begun exploring automated generation of Dockerfiles, Kubernetes manifests, and CI/CD pipelines. However, despite growing industrial interest, systematic academic evaluation of end-to-end cloud-native development automation remains limited. Our work addresses this gap by proposing both a framework and benchmark for assessing multi-agent performance on cloud-native development tasks.

3. System Design

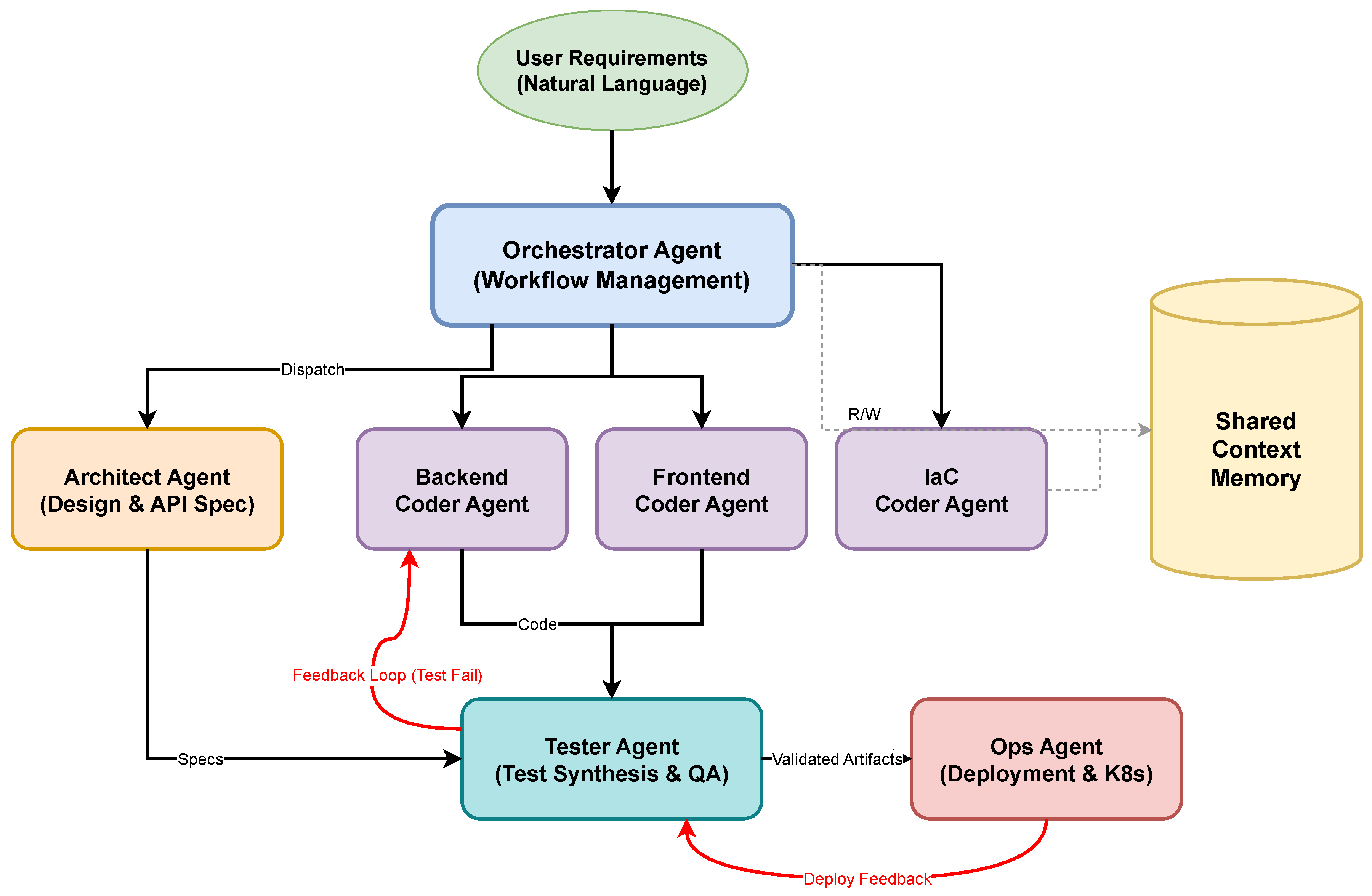

CloudMAS comprises six specialized agents coordinated by a dedicated Orchestrator Agent, as illustrated in

Figure 1. The six specialized agents are: (1) Architect Agent, (2) Backend Coder Agent, (3) Frontend Coder Agent, (4) IaC Coder Agent, (5) Tester Agent, and (6) Ops Agent. The Orchestrator Agent serves as an additional coordinating agent that manages the overall workflow and inter-agent communication. Each agent is implemented using a state-of-the-art LLM (Claude 3.5 Sonnet in our experiments) with role-specific prompts and tool access. Agents communicate through a shared context memory that maintains project state and enables cross-referencing of artifacts.

3.1. Orchestrator Agent

The Orchestrator Agent serves as the entry point for user requirements and coordinates the overall workflow. Upon receiving a natural language requirement specification, it performs initial parsing to identify key entities, desired functionality, and non-functional constraints. The orchestrator decomposes complex requirements into subtasks and dispatches them to appropriate specialized agents.

The orchestrator maintains a global execution plan represented as a directed acyclic graph (DAG) of tasks, where edges encode dependencies. It monitors agent progress, aggregates outputs, and triggers conflict resolution procedures when inconsistencies arise. The execution plan is dynamically updated based on intermediate results and feedback from downstream agents.

3.2. Architect Agent

The Architect Agent is responsible for high-level system design, including service decomposition, API specification, and data model definition. Given parsed requirements from the orchestrator, it produces a structured design document comprising the following artifacts:

Service boundaries and responsibilities following domain-driven design principles.

RESTful API specifications in OpenAPI format, including endpoints, request/response schemas, and authentication requirements.

Data models with entity relationships and validation constraints.

Inter-service communication patterns (synchronous REST, asynchronous messaging).

The agent is prompted to consider scalability, loose coupling, and operational concerns during design. Its outputs are stored in shared context memory and serve as specifications for downstream Coder Agents.

3.3. Coder Agents

Three parallel Coder Agents handle implementation across distinct domains. The separation enables focused expertise and parallel execution, improving both quality and efficiency.

The Backend Coder Agent generates server-side application code based on API specifications from the Architect Agent. It produces RESTful endpoints, business logic, database access layers, and authentication mechanisms. The agent is prompted to follow best practices for the target framework (e.g., FastAPI, Spring Boot) and to include proper error handling and logging.

The Frontend Coder Agent creates client-facing interfaces when required. It generates responsive UI components, API integration code, and state management logic. The agent supports multiple frontend frameworks and produces accessible, high-performance implementations.

The Infrastructure-as-Code (IaC) Coder Agent generates configuration for cloud resources, including database provisioning, message queues, and storage buckets. It produces Terraform or CloudFormation templates aligned with the architectural design.

3.4. Tester Agent

The Tester Agent synthesizes and executes test cases to validate generated code. Its responsibilities include generating unit tests for individual functions and classes, integration tests for API endpoints, contract tests for inter-service communication, and executing tests and parsing results.

Test generation follows a specification-based approach, deriving test cases from API specifications and expected behaviors documented by the Architect Agent. The agent employs techniques including boundary value analysis, equivalence partitioning, and edge case generation. Failed tests trigger feedback to relevant Coder Agents with detailed error information to guide corrections.

3.5. Ops Agent

The Ops Agent produces deployment artifacts and validates that generated services can be successfully deployed to a Kubernetes cluster. Its outputs include Dockerfiles for containerizing each service, Kubernetes manifests (Deployments, Services, ConfigMaps, Secrets), health check and readiness probe configurations, and resource requests and limits based on expected workload.

The agent performs deployment validation by applying manifests to a test cluster and verifying that pods reach ready state, services are accessible, and inter-service communication functions correctly. Deployment failures trigger feedback loops with diagnostic information.

3.6. Inter-Agent Communication and Conflict Resolution

Agents communicate through a structured message protocol that includes sender and receiver identifiers, message type (request, response, feedback), artifact references, and confidence scores. The shared context memory stores all generated artifacts with versioning, enabling agents to reference and build upon each other’s work.

When conflicts arise, such as API implementations that deviate from specifications, the orchestrator initiates a resolution procedure. The responsible agent receives detailed feedback including the nature of the discrepancy, relevant artifacts, and suggested remediation. Agents may iterate up to a configurable maximum number of attempts before escalating to human review.

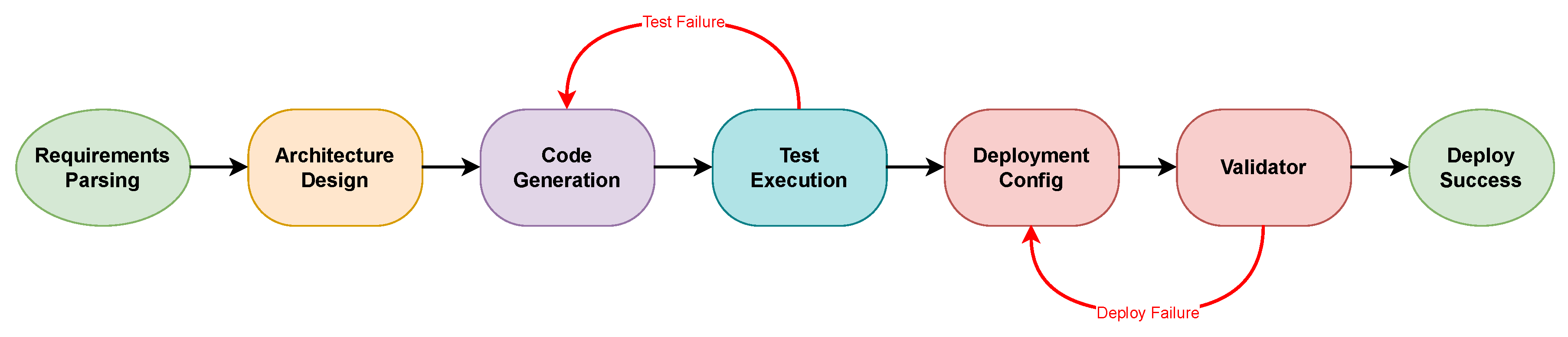

Figure 2 illustrates the agent workflow including feedback loops.

The conflict resolution mechanism implements a responsibility attribution algorithm. When a test fails, the system traces the failure to specific code segments, API specifications, or configuration errors. This enables targeted feedback rather than requiring wholesale regeneration of artifacts.

4. CloudDevBench: A Benchmark for End-to-End Development

To enable systematic evaluation of multi-agent coding assistants for cloud-native development, we construct CloudDevBench, a benchmark comprising 50 development tasks with comprehensive evaluation criteria.

4.1. Task Collection

Tasks are derived from three sources and span four complexity levels. Open-source projects contribute 20 tasks sourced from GitHub issues in popular repositories including Django, FastAPI, and Spring Boot, filtered for those requiring complete feature implementation rather than bug fixes. Synthetic requirements provide 20 tasks spanning common cloud-native patterns such as CRUD APIs, authentication services, data pipelines, and event-driven architectures, authored by experienced developers. Complex scenarios include 10 tasks involving multi-service architectures with non-trivial inter-service dependencies, database migrations, and deployment constraints.

We categorize the 50 tasks by complexity: 15 simple CRUD tasks involving single-service applications with basic database operations, 25 medium-complexity tasks comprising single-service or two-service applications with moderate integration requirements (e.g., REST APIs with authentication, basic frontend integration), and 10 complex multi-service scenarios requiring three or more coordinated services with advanced features such as message queues and distributed transactions.

Each task includes a natural language requirement specification, reference implementation, comprehensive test suite, deployment validation scripts, and expected output artifacts.

4.2. Evaluation Metrics

We evaluate systems across four primary dimensions. Compilation Success Rate (CSR) measures the percentage of generated projects that compile without errors. Test Pass Rate (TPR) captures the percentage of unit and integration tests passed. Deployment Success Rate (DSR) indicates the percentage of projects successfully deployed to a Kubernetes test cluster with all services healthy. API Consistency Score (ACS) quantifies alignment between implemented APIs and specifications using automated schema comparison.

Additionally, we measure token consumption and execution time to assess efficiency. Human evaluation of code quality is conducted on a random sample of 20% of outputs.

4.3. Baseline Systems

We compare CloudMAS against two baseline configurations. Single LLM represents a monolithic prompt approach where the entire requirement is provided to a single LLM invocation, which must generate all artifacts in one response. Single Agent employs a single autonomous agent with access to tools for code generation, testing, and deployment, but without specialized role decomposition.

Both baselines use the same underlying LLM (Claude 3.5 Sonnet) to ensure fair comparison. The single agent baseline implements a ReAct-style [

15] reasoning loop with tool access.

5. Experimental Results

5.1. Overall Performance

Table 1 presents the main experimental results across all evaluation metrics. CloudMAS achieves the highest scores on compilation success (92%), test pass rate (81%), and deployment success (84%), substantially outperforming both baselines.

The single LLM baseline struggles with complex tasks, frequently producing incomplete implementations or inconsistent artifacts. Context length limitations prevent it from generating comprehensive solutions for multi-service architectures. The single agent baseline shows improved performance through iterative refinement but lacks the specialized expertise that multi-agent collaboration provides.

CloudMAS demonstrates particularly strong improvements on deployment success rate (+32% over single agent), attributable to the dedicated Ops Agent that specializes in container and orchestration configuration. The Tester Agent’s feedback loops enable iterative correction of implementation errors, contributing to higher test pass rates.

5.2. Performance by Task Complexity

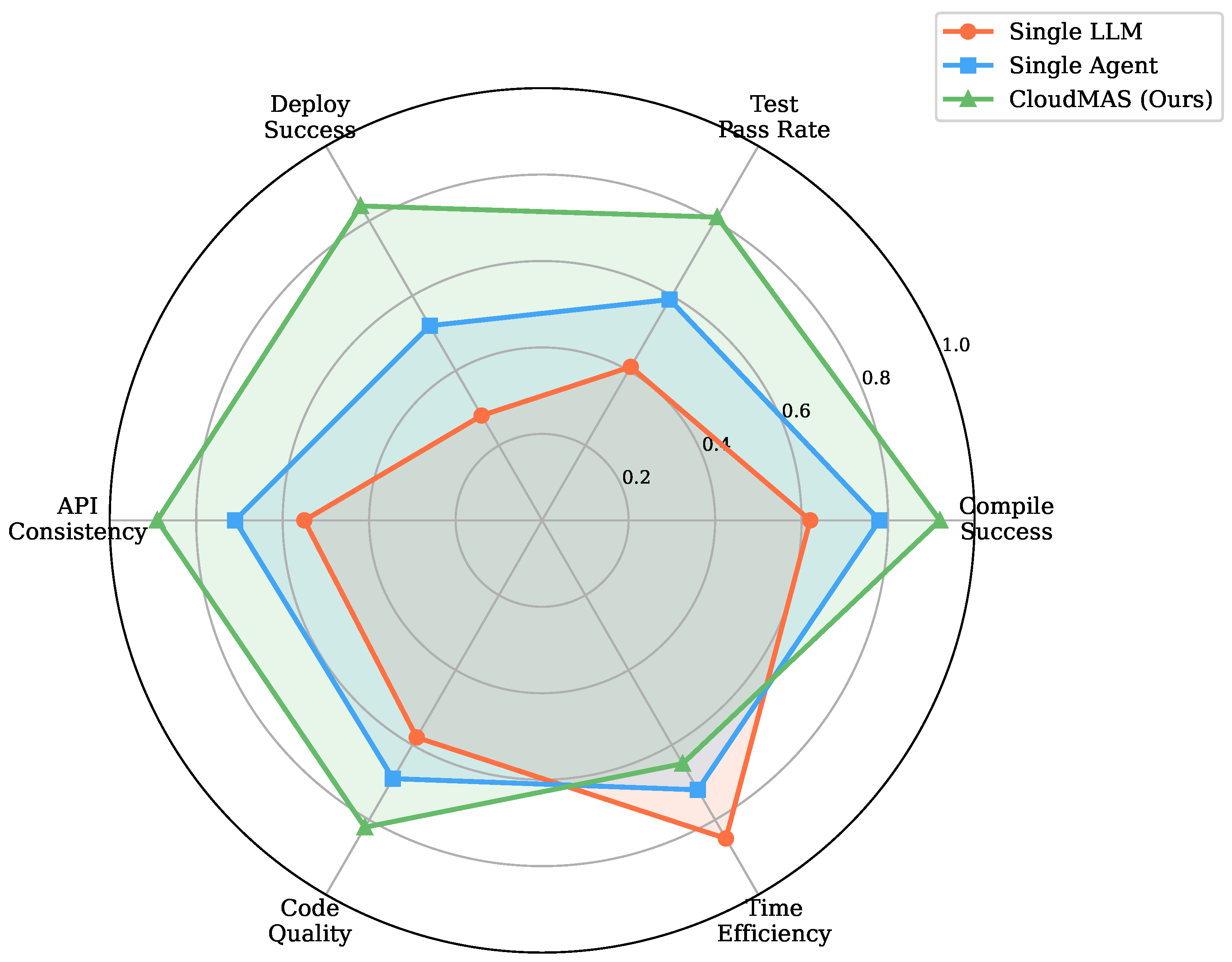

Figure 3 presents a radar chart comparing the three systems across evaluation dimensions. CloudMAS maintains strong performance across all metrics, while baselines show pronounced weaknesses in deployment and testing.

We analyze performance stratified by task complexity. Simple CRUD tasks (n=15) show all systems achieving reasonable compilation rates, but deployment success varies substantially (Single LLM: 53%, Single Agent: 73%, CloudMAS: 93%). Medium-complexity tasks (n=25) show CloudMAS maintaining 85% deployment success compared to 48% for Single Agent. Complex multi-service scenarios (n=10) reveal the greatest performance gaps, with CloudMAS achieving 70% deployment success compared to 20% for Single LLM and 35% for Single Agent.

5.3. Ablation Study

To understand the contribution of each component, we conduct ablation experiments removing individual agents or mechanisms. Results are presented in

Figure 4.

Removing the Architect Agent causes the most severe degradation in API consistency (0.89 → 0.68), as Coder Agents lack coherent specifications to implement. Removing the Tester Agent substantially reduces test pass rate (0.81 → 0.56), demonstrating the value of automated test generation and feedback. Removing the Ops Agent devastates deployment success (0.84 → 0.45), confirming the importance of specialized expertise for containerization and orchestration.

Disabling feedback loops reduces all metrics, with test pass rate dropping from 0.81 to 0.65 and deployment success from 0.84 to 0.71. This validates our iterative refinement approach. Removing shared context memory similarly degrades performance, particularly for API consistency (0.89 → 0.75), as agents lose the ability to reference each other’s artifacts.

5.4. Efficiency Analysis

Multi-agent systems incur overhead from inter-agent communication and multiple LLM invocations compared to the single-agent baseline.

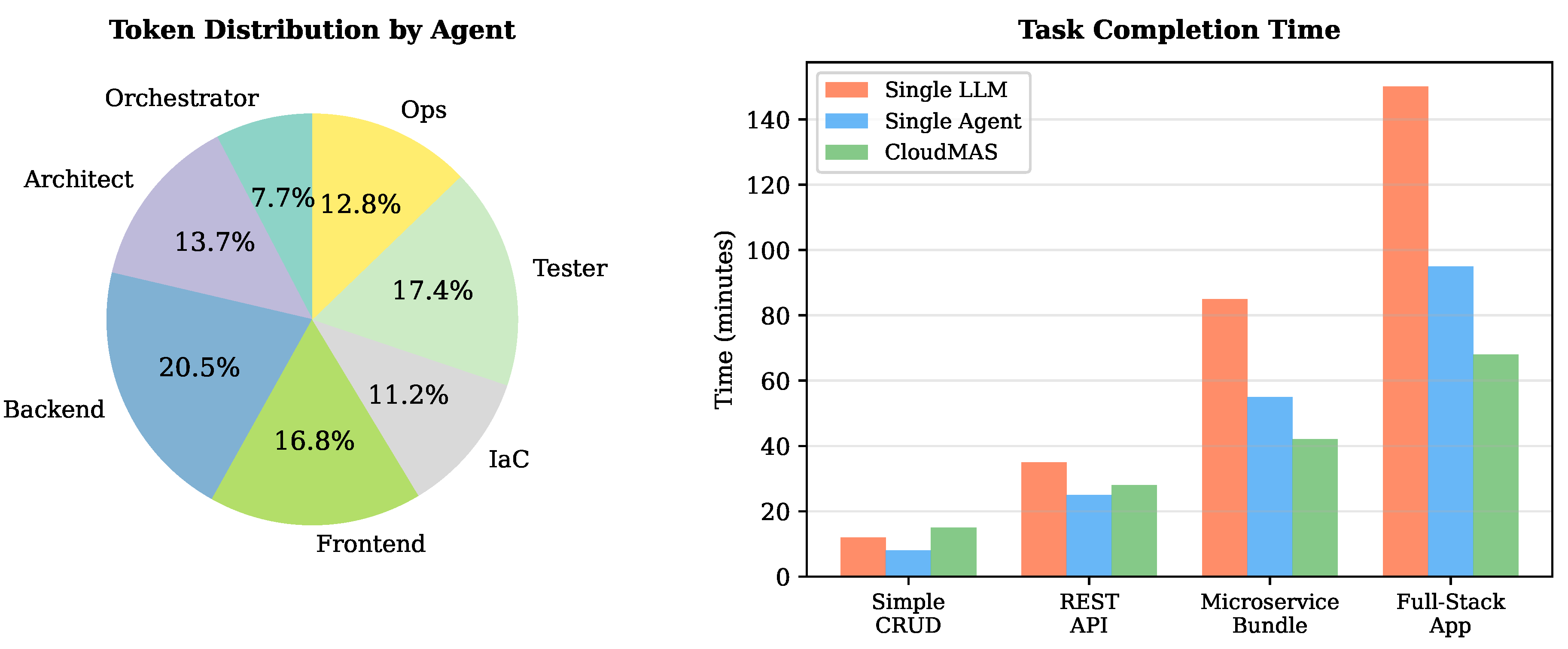

Figure 5 analyzes token consumption and execution time.

For simple tasks, total token consumption averages 111K tokens, distributed across agents as shown. Backend and Tester agents consume the most tokens due to code generation and test synthesis complexity. However, complex multi-service tasks exhibit significantly higher consumption, averaging 450K–650K tokens due to multiple feedback iterations and larger codebases. This explains the cost variation: simple tasks cost approximately $0.8–1.5, while complex scenarios with extensive retry loops reach $4–8 at current API pricing (based on Claude 3.5 Sonnet rates of $3 per 1M input tokens and $15 per 1M output tokens).

For simple tasks, the single agent baseline is faster (8 vs. 15 minutes on average), as multi-agent coordination overhead exceeds benefits. However, for complex multi-service scenarios, CloudMAS completes tasks in 68 minutes on average compared to 95 minutes for the single agent, a 28% improvement.

5.5. Human Evaluation

We conducted human evaluation on 10 randomly sampled outputs per system. Three experienced developers rated code quality on dimensions of correctness, readability, best practices adherence, and documentation. Results are presented in

Table 2.

CloudMAS receives the highest ratings across all dimensions. Evaluators noted that the architectural design document produced by the Architect Agent improves code organization, and the Ops Agent’s deployment configurations follow production best practices.

6. Discussion

6.1. Key Findings

Our experiments reveal several insights. First, role specialization is beneficial. Assigning focused responsibilities to agents enables deeper expertise than generalist approaches. The Ops Agent’s specialized knowledge of containerization patterns contributes substantially to deployment success. Second, iterative feedback is critical. The feedback loops between Tester and Coder Agents, and between Ops Agent and the system, enable progressive refinement that single-pass approaches cannot achieve. Third, architectural consistency matters. The Architect Agent’s specifications provide a coherent foundation that reduces integration errors downstream.

6.2. Limitations and Threats to Validity

CloudMAS has several limitations. The current implementation supports a limited set of technology stacks (Python/FastAPI, React, Terraform). Extending to additional languages and frameworks requires developing new prompts and tool integrations. The system assumes cloud-native microservices architectures; monolithic or serverless patterns are not well supported.

Token consumption and API costs remain substantial for complex tasks, averaging $4–8 per multi-service scenario at current pricing due to extensive feedback iterations (simple tasks cost $0.8–1.5). Optimization through prompt compression, caching, and selective regeneration could reduce costs.

The CloudDevBench benchmark, while more comprehensive than existing alternatives, contains only 50 tasks. Expanding the benchmark with additional domains and complexity levels is an important direction for future work.

Threats to Validity. Several factors may limit the generalizability of our findings. First, our benchmark tasks are predominantly based on Python/FastAPI backend and React frontend stacks, which may not represent the full diversity of enterprise cloud-native projects. Second, all experiments use a single underlying LLM (Claude 3.5 Sonnet); cross-model transferability remains to be validated with other foundation models such as GPT-4 or open-source alternatives. Third, our evaluation focuses on functional correctness and deployment success, but does not comprehensively assess non-functional requirements such as security vulnerabilities, performance under load, or long-term maintainability.

6.3. Implications for Practice

Our results suggest that multi-agent architectures can substantially accelerate cloud-native development while maintaining code quality. Organizations exploring AI-assisted development should consider role-specialized approaches rather than monolithic AI assistants.

The feedback mechanisms we introduce could be integrated into existing development workflows, enabling AI agents to learn from CI/CD pipeline failures and progressively improve their outputs.

7. Conclusion

This paper presented CloudMAS, a multi-agent coding assistant that transforms natural language requirements into deployable cloud-native microservices. Through specialized agents for architecture, coding, testing, and operations, combined with iterative feedback mechanisms, CloudMAS achieves 92% compilation success, 81% test pass rate, and 84% deployment success on our CloudDevBench benchmark.

Our contributions include a novel multi-agent architecture with conflict resolution mechanisms, a publicly available benchmark for end-to-end cloud-native development evaluation, and comprehensive experiments demonstrating the benefits of role specialization and iterative refinement.

Future work will extend CloudMAS to additional technology stacks, incorporate human-in-the-loop refinement, and explore multi-agent collaboration on larger-scale enterprise applications. The CloudDevBench benchmark and evaluation framework will be released to facilitate further research in this area.

References

- Richardson, C. Microservices Patterns: With Examples in Java; Manning Publications, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- OpenAI, *!!! REPLACE !!!*. GPT-4 Technical Report. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2303.08774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anthropic. The Claude Model Family: Claude 3.5 Sonnet Model Card Addendum. Online. 2024.

- Chen, M.; et al. Evaluating Large Language Models Trained on Code. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2107.03374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, S.; et al. MetaGPT: Meta Programming for A Multi-Agent Collaborative Framework. In Proceedings of the Proc. ICLR, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Qian, C.; et al. ChatDev: Communicative Agents for Software Development. In Proceedings of the Proc. ACL, 2024; pp. 15174–15186. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Q.; et al. AutoGen: Enabling Next-Gen LLM Applications via Multi-Agent Conversation. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2308.08155. [Google Scholar]

- Jimenez, C.E.; et al. SWE-bench: Can Language Models Resolve Real-World GitHub Issues? In Proceedings of the Proc. ICLR, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Austin, J.; et al. Program Synthesis with Large Language Models. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2108.07732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuo, T.Y.; et al. BigCodeBench: Benchmarking Code Generation with Diverse Function Calls and Complex Instructions. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2406.15877. [Google Scholar]

- Jain, N.; et al. LiveCodeBench: Holistic and Contamination Free Evaluation of Large Language Models for Code. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2403.07974. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, D.; et al. AgentCoder: Multi-Agent-based Code Generation with Iterative Testing and Optimisation. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2312.13010. [Google Scholar]

- Ishibashi, Y.; Nishimura, Y. Self-Organized Agents: A LLM Multi-Agent Framework toward Ultra Large-Scale Code Generation and Optimization. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2404.02183. [Google Scholar]

- Forsgren, N.; Humble, J.; Kim, G. Accelerate: The Science of Lean Software and DevOps; IT Revolution Press, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, S.; et al. ReAct: Synergizing Reasoning and Acting in Language Models. In Proceedings of the Proc. ICLR, 2023. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).