Introduction

Standard ADHD pharmacotherapy has long centred on boosting synaptic DA and norepinephrine. Over the past decade, however, converging data indicate that symptoms also reflect a mis-paced exchange between DA and glutamatergic circuits in the prefrontal cortex [

1,

2]. Stimulants normalise this interaction to a degree, yet residual cognitive complaints are common. Ketamine research offers a clue: mood and cognition can improve rapidly once synapses shift from an "NMDA-dominant" to an "AMPA-dominant" state [

3].

Ngo Cheung recently proposed a four-component, all-oral stack—dextromethorphan (DXM), a CYP2D6 inhibitor, piracetam, and L-glutamine—that aims to mimic ketamine's full plasticity cascade [

3]. The present paper considers whether that framework, with stimulant-specific adjustments, might target the lingering deficits in adults with ADHD.

Dopamine–Glutamate Coupling in ADHD

In the healthy prefrontal cortex (PFC), DA modulates excitatory drive by steering AMPA and NMDA receptor function. Activation of D1 receptors recruits protein kinase A, prompting GluA1-containing AMPA receptors to insert into the postsynaptic membrane—a prerequisite for long-term potentiation [

4]. D2 signalling plays the foil, constraining over-excitation [

5].

Evidence of Mis-timed Signalling Animal work supports the notion of a coupling error. Spontaneously hypertensive rats (SHR), commonly utilized as a model for ADHD, exhibit increased AMPA-dependent norepinephrine release while demonstrating diminished NMDA-mediated calcium influx [

6,

7]. The human DRD4 7-repeat allele diminishes NMDA receptor activity in prefrontal cortex neurons at the genetic level [

8]. In summary, these results show that ADHD is a condition in which DA does not align NMDA and AMPA throughput, which makes network plasticity less effective.

Why AMPA Enhancement and NMDA Modulation Are Important

An expanding corpus of research on rapid-acting antidepressants indicates that sustained symptom alleviation occurs subsequent to a pronounced shift towards AMPA signaling, alongside a transient reduction of NMDA noise [

3,

9]. In rodent studies, the inhibition of AMPA receptors negates the behavioral advantages of ketamine, while positive AMPA modulators replicate these effects [

10].

Memantine, an uncompetitive NMDA antagonist, already shows promise in ADHD [

11]. These observations imply that a therapy combining modest NMDA antagonism with AMPA potentiation could accelerate synaptic repair in ADHD, especially for patients whose stimulant response is incomplete.

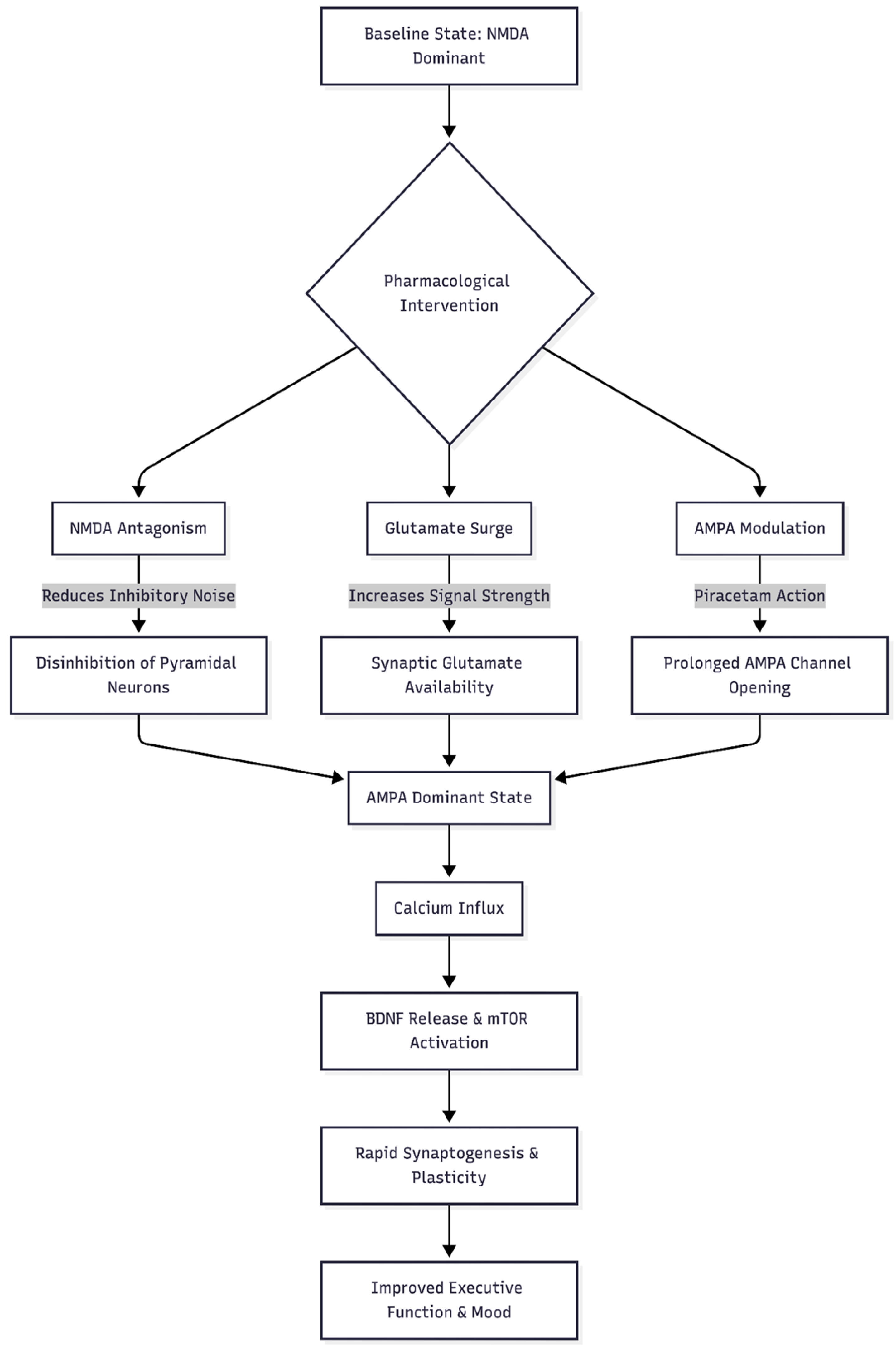

Figure 1.

This flowchart demonstrates the theoretical "Cheung Glutamatergic Regimen" mechanism, showing how the different components interact to shift the brain state from NMDA-dominant to AMPA-dominant.

Figure 1.

This flowchart demonstrates the theoretical "Cheung Glutamatergic Regimen" mechanism, showing how the different components interact to shift the brain state from NMDA-dominant to AMPA-dominant.

The Original Cheung Glutamatergic Regimen

Cheung's protocol pairs four low-cost agents [

3]:

Dextromethorphan (DXM) – delivers a rapid but short-lived NMDA block.

A strong CYP2D6 inhibitor (e.g., fluoxetine, paroxetine) – prolongs DXM exposure.

Piracetam – a positive allosteric modulator (PAM) at AMPA receptors, keeping channels open longer.

L-glutamine – replaces presynaptic glutamate stores and buffers excitotoxic spikes.

The sequence unfolds as follows: NMDA inhibition lowers baseline noise; pyramidal neurons discharge a glutamate pulse; piracetam heightens AMPA throughput; calcium entry releases BDNF and activates mTOR; rapid synaptogenesis follows [

12]. In principle, the same cascade might restore PFC network efficiency in ADHD.

Adapting the Regimen for Stimulant Classes

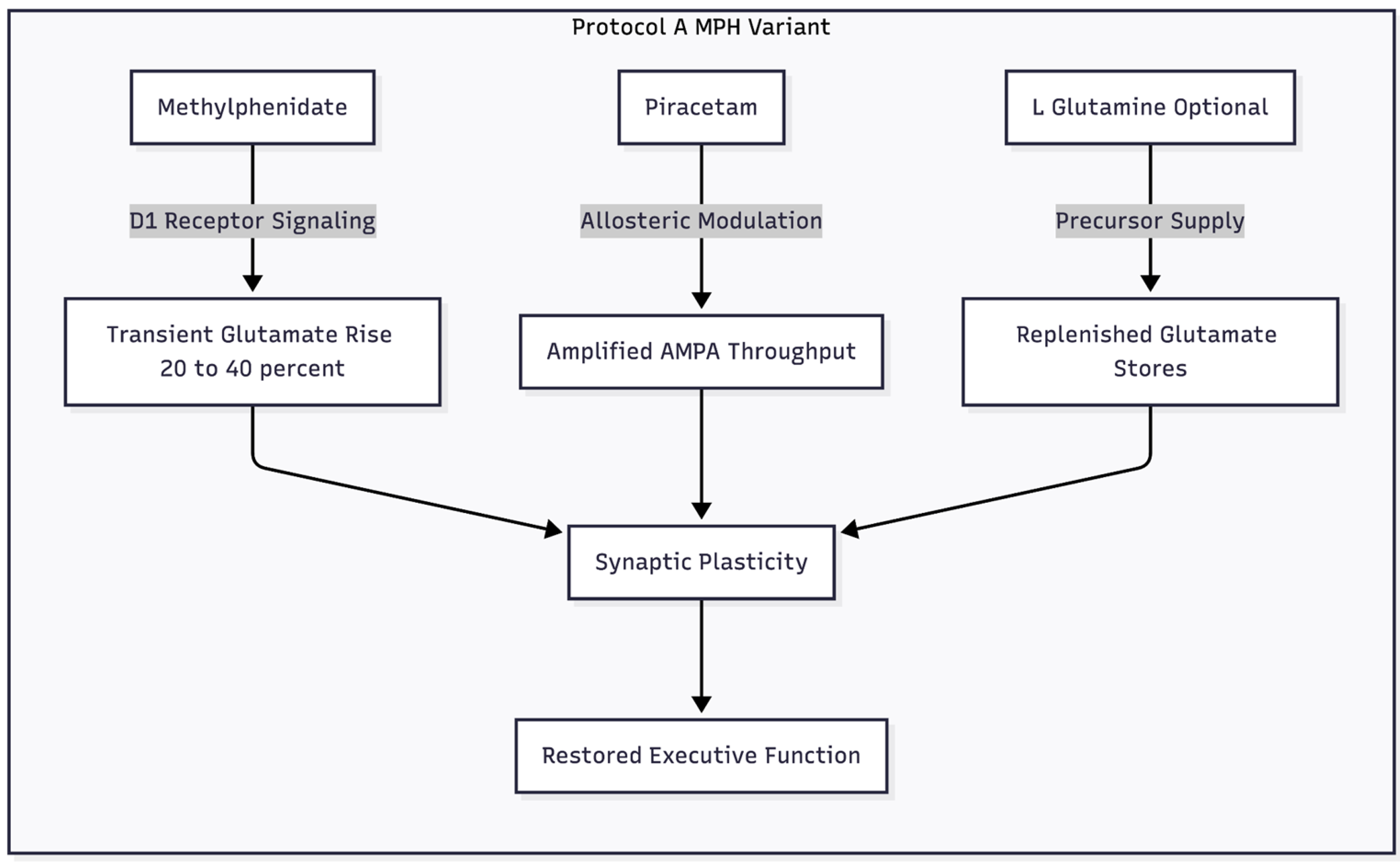

Modification A: Methylphenidate Plus Piracetam (± Glutamine)

Therapeutic doses of methylphenidate (MPH) raise extracellular glutamate in the PFC by roughly 20–40 % through D1-ERK pathways [

13]. The increase is transient—plasma clearance occurs within three hours—limiting excitotoxic risk. Hence, MPH itself can supply the "push," rendering high-dose DXM unnecessary.

Piracetam, the "pull," slows AMPA receptor desensitisation and boosts conductance [

14]. Stacking the two may sharpen executive functions and lift motivational tone. L-glutamine can be included for patients under chronic stress whose glutamate reserves are depleted [

15].

Dosage sketch: MPH at the individual’s established dose; piracetam 600-1200 mg/day in divided doses; optional L-glutamine 500-1000 mg/day.

Figure 2.

This diagram illustrates the specific adaptation for patients taking Methylphenidate, highlighting why DXM is removed and how the stimulant provides the glutamate "push."

Figure 2.

This diagram illustrates the specific adaptation for patients taking Methylphenidate, highlighting why DXM is removed and how the stimulant provides the glutamate "push."

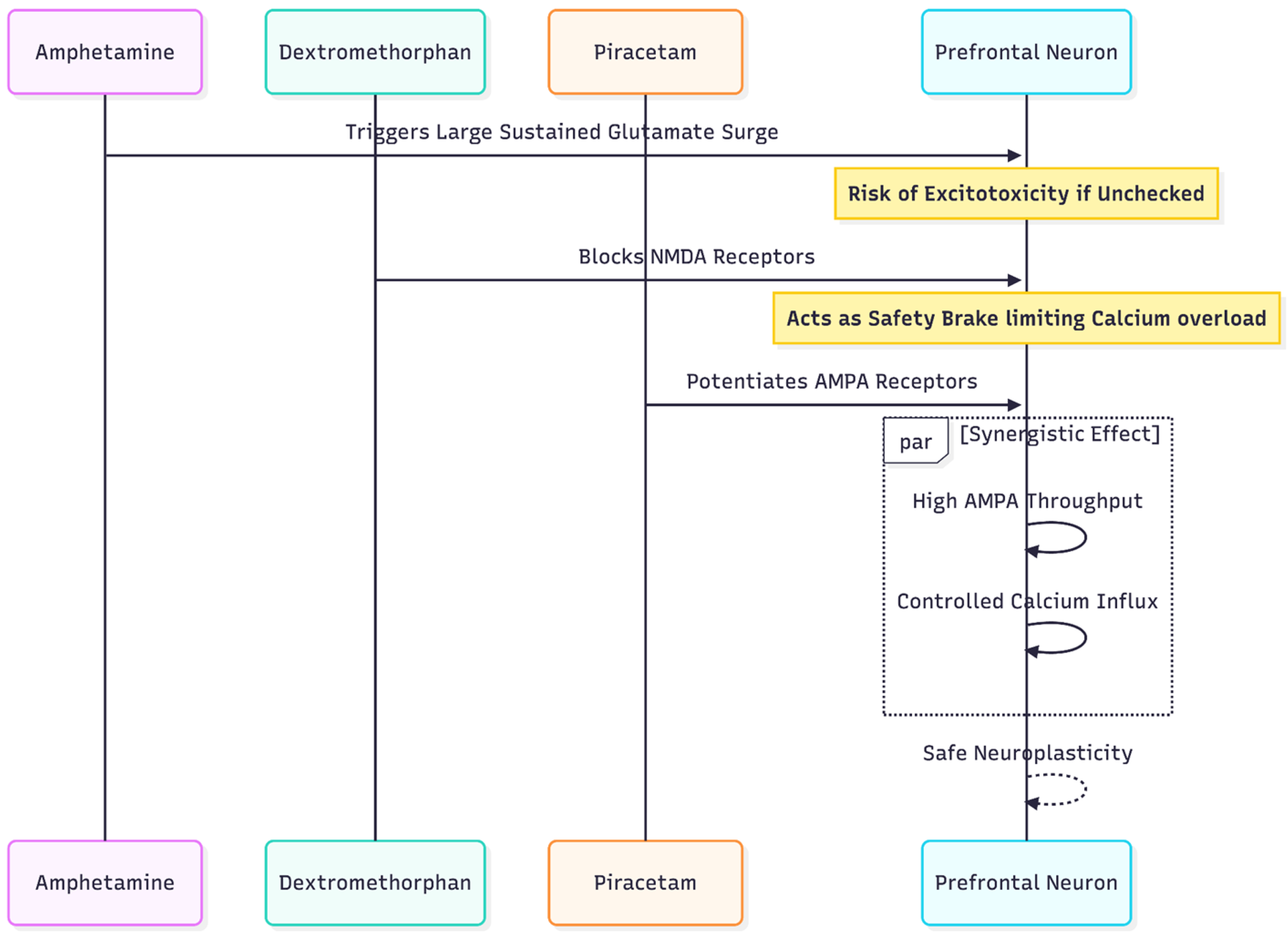

Modification B: Amphetamine + DXM + Piracetam (± Glutamine)

Amphetamines provoke larger, longer glutamate surges—often doubling extracellular levels for 6–12 h [

16]. If piracetam were added alone, sustained AMPA opening could tip neurons toward calcium overload. Introducing DXM provides a concurrent NMDA "brake," trimming calcium influx while still permitting AMPA-mediated plasticity.

Dosage sketch: standard amphetamine prescription; DXM 45–60 mg timed-release (no CYP2D6 booster to avoid amphetamine toxicity); piracetam 1,200 mg twice daily; optional L-glutamine as above.

Figure 3.

This diagram illustrates the more complex adaptation for Amphetamine users, emphasizing the necessity of adding DXM as a safety brake against excitotoxicity due to the stronger glutamate surge caused by amphetamines.

Figure 3.

This diagram illustrates the more complex adaptation for Amphetamine users, emphasizing the necessity of adding DXM as a safety brake against excitotoxicity due to the stronger glutamate surge caused by amphetamines.

Pharmacokinetic Caveats: The CYP2D6 Constraint

DXM and many amphetamines share CYP2D6 metabolic pathways. Strong inhibitors such as fluoxetine, paroxetine, or bupropion can elevate blood levels of both drugs, risking hypertension or serotonergic toxicity [

17]. Therefore, the MPH-piracetam plan may safely pair with CYP2D6 inhibitors if DXM is omitted. By contrast, the amphetamine-based protocol should avoid additional CYP2D6 blockade unless the patient is considered a CYP2D6 fast metabolizer.

Clinical Evidences

Preliminary case observations endorse the MPH-piracetam combination: one adult with ADHD indicated that the addition of 1,200 mg piracetam to 18 mg MPH reinstated sustained attention and motivation; the benefits dissipated upon withdrawal and re-emerged upon rechallenge [

18]. A small controlled trial also found that cognitive scores were better when piracetam was added to stimulant therapy [

19].The next step is to do a lot of testing.

Conclusion

A growing literature frames ADHD as a disorder of DA-guided glutamatergic timing. The Cheung Glutamatergic Regimen offers a mechanistic blueprint—brief NMDA dampening, amplified AMPA drive, and replenished glutamate stores—for correcting that timing. With stimulant-specific adjustments, the protocol could alleviate residual cognitive symptoms while avoiding excitotoxic pitfalls. Prospective trials will determine whether this hypothesis translates into everyday clinical benefit.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethics Declaration

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

None declared.

References

- Kuś, J.; Saramowicz, K.; Czerniawska, M.; Wiese, W.; Siwecka, N.; Rozpędek-Kamińska, W.; Kucharska-Lusina, A.; Strzelecki, D.; Majsterek, I. Molecular Mechanisms Underlying NMDARs Dysfunction and Their Role in ADHD Pathogenesis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 12983. [CrossRef]

- MacDonald, H.J.; Kleppe, R.; Szigetvari, P.D.; Haavik, J. The dopamine hypothesis for ADHD: An evaluation of evidence accumulated from human studies and animal models. Front. Psychiatry 2024, 15, 1492126. [CrossRef]

- Cheung, N. DXM, CYP2D6-inhibiting antidepressants, piracetam, and glutamine: Proposing a ketamine-class antidepressant regimen with existing drugs. Preprints. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Zhao, Y.; Wolf, M.E. Dopamine Receptor Stimulation Modulates AMPA Receptor Synaptic Insertion in Prefrontal Cortex Neurons. J. Neurosci. 2005, 25, 7342–7351. [CrossRef]

- Tseng, K.Y.; O'Donnell, P. Dopamine–Glutamate Interactions Controlling Prefrontal Cortical Pyramidal Cell Excitability Involve Multiple Signaling Mechanisms. J. Neurosci. 2004, 24, 5131–5139. [CrossRef]

- Lehohla, M.; Kellaway, L.; Russell, V.A. NMDA Receptor Function in the Prefrontal Cortex of a Rat Model for Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder. Metab. Brain Dis. 2004, 19, 35–42. [CrossRef]

- Russell, V.A. Increased AMPA Receptor Function in Slices Containing the Prefrontal Cortex of Spontaneously Hypertensive Rats. Metab. Brain Dis. 2001, 16, 143–149. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhong, P.; Gu, Z.; Yan, Z. Regulation of NMDA Receptors by Dopamine D4Signaling in Prefrontal Cortex. J. Neurosci. 2003, 23, 9852–9861. [CrossRef]

- Duman, R.S.; Aghajanian, G.K. Synaptic Dysfunction in Depression: Potential Therapeutic Targets. Science 2012, 338, 68–72. [CrossRef]

- Maeng, S., Zarate, C. A., Du, J., et al. Cellular mechanisms underlying the antidepressant effects of ketamine: Role of AMPA receptors. Biological Psychiatry. 2008;63(4):349–352.

- Choi, W.-S.; Wang, S.-M.; Woo, Y.S.; Bahk, W.-M. Therapeutic Efficacy and Safety of Memantine for Children and Adults With ADHD With a Focus on Glutamate-Dopamine Regulation. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2024, 86, 58158. [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Lee, B.; Liu, R.-J.; Banasr, M.; Dwyer, J.M.; Iwata, M.; Li, X.-Y.; Aghajanian, G.; Duman, R.S. mTOR-Dependent Synapse Formation Underlies the Rapid Antidepressant Effects of NMDA Antagonists. Science 2010, 329, 959–964. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.; Xiong, Z.; Duffney, L.J.; Wei, J.; Liu, A.; Liu, S.; Chen, G.-J.; Yan, Z. Methylphenidate Exerts Dose-Dependent Effects on Glutamate Receptors and Behaviors. Biol. Psychiatry 2014, 76, 953–962. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, A.H.; Oswald, R.E. Piracetam Defines a New Binding Site for Allosteric Modulators of α-Amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazole-propionic Acid (AMPA) Receptors. J. Med. Chem. 2010, 53, 2197–2203. [CrossRef]

- Baek, J.H.; Jung, S.; Son, H.; Kang, J.S.; Kim, H.J. Glutamine Supplementation Prevents Chronic Stress-Induced Mild Cognitive Impairment. Nutrients 2020, 12, 910. [CrossRef]

- Rowley, H.L.; Kulkarni, R.S.; Gosden, J.; Brammer, R.J.; Hackett, D.; Heal, D.J. Differences in the neurochemical and behavioural profiles of lisdexamfetamine methylphenidate and modafinil revealed by simultaneous dual-probe microdialysis and locomotor activity measurements in freely-moving rats. J. Psychopharmacol. 2013, 28, 254–269. [CrossRef]

- Flockhart, D. A., Thacker, D., McDonald, C., et al. The Flockhart Cytochrome P450 Drug-Drug Interaction Table. Division of Clinical Pharmacology, Indiana University School of Medicine. 2021.

- Cheung, N. Methylphenidate plus piracetam: A two-drug, AMPA-centric alternative replicating ketamine's neuroplastic signature. Preprints. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Alavi, K.; Shirazi, E.; Akbari, M.; Shahrivar, Z.; Noori, F.-S.; Shirazi, S. Effects of Piracetam as an Adjuvant Therapy on Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial. Iran. J. Psychiatry Behav. Sci. 2021, 15. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |