1. Introduction

Climate change represents one of the most complex challenges of the modern era, primarily driven by continuous increase in greenhouses gas (GHG) concentration; carbon dioxide (CO2), methane (CH4) and nitrous oxide (N2O), in the atmosphere. These gases have led to a rise in the global mean air temperature by more than 1 °C compared to pre-industrial levels, accompanied by altered precipitation patterns, reduced soil fertility and biodiversity loss. Such changes strongly affect food production system that depend on stable agroecological conditions.

The agricultural sector is both a source and a potential sink of greenhouse gases. According to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [

1] agriculture contributes over 10% of total global GHG emissions, mainly through soil management, livestock production and fertilizer use. In recent years, as concerns about climate change continue to intensify, land management has become increasingly important due to its potential influence on regulating greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions from agricultural soils [

2]. The exchange of greenhouse gases between agricultural soils and the atmosphere is expectedly variable in both space and time, depending on the season and landscape position [

3]. Agricultural land occupies approximately 37% of Earth’s terrestrial surface and accounts for 52–84% of global anthropogenic methane and nitrous oxide emissions. Global assessments indicate that agricultural and degraded soils have lost substantial amounts of organic carbon (42–78 Gt C), while more recent studies suggest losses up to 133 Gt C. These declines are linked to intensive tillage, which accelerates organic matter decomposition, residue removal and disturbances of soil microbial processes [

4]. Implementing appropriate agricultural practices is therefore crucial for addressing these issues. Increasing soil carbon stocks can be achieved through adapted management practices such as reduced or no tillage, retention of crop residues or mulch, application of organic amendments and other conservation-oriented techniques [

5,

6]. Thus, a better understanding and quantification of the factors influencing agricultural GHG emissions, as well as knowledge of how, when and where these emissions can be mitigated, is needed [

7]. According to [

8] restoring 750 million hectares of degrading soils could sequester up to 1.1 Gt C annually. The global technical mitigation potential of the agricultural sector, considering all greenhouse gases, is estimated at approximately 5.5–6.0 Gt CO

2 eq per year [

9,

10].

However, through biological carbon sequestration, agriculture also offers an effective means to mitigate climate change by storing atmospheric carbon in plant biomass and after its decomposition as soil organic matter. Soil is recognized as the largest terrestrial carbon reservoir, containing two to three times more carbon than the atmosphere, while plants play a vital role in capturing and transferring carbon to the soil through photosynthesis and incorporation of biomass into the soil. The efficiency of carbon sequestration depends on both environmental conditions and management practices. Soil texture, mineral composition and microbial activity influence the stabilization of soil organic carbon, while climate related variables such as temperature and moisture regulate carbon turnover and mineralization rates [

11]. Importantly, root derived carbon has been shown to contribute more effectively to the formation of stable, mineral associated organic matter compared with aboveground residues, emphasizing the role of crops with substantial below ground biomass [

12]. The advantage of biological carbon sequestration lies primarily in the direct ability of plants to remove CO

2 from the atmosphere. This not only reduces the concentration of a major greenhouse gas and slows the rise in global temperature but also contributes to improving soil fertility. A portion of plant material remains permanently stored in the soil as humus following organic matter decomposition, while roots and rhizosphere exudates constitute more slowly decomposable carbon pools [

13]. Another important advantage is that biomass-based sequestration can be immediately implemented in existing agricultural systems without requiring new infrastructure or technologies. With appropriate biomass management, crop and cultivar selection, crop rotation and conservation tillage, it is possible to systematically enhance the capacity of agricultural land to store carbon in both biomass and soil [

14].

The quantity of carbon stored in plant biomass varies among crop species, cultivars and management practices. In addition to crop type, genetic variability within a species can significantly affect dry matter yield and carbon sequestration capacity. Among cereal crops, barley (

Hordeum vulgare L.) stands out for its adaptability, short growing season and ability to thrive under diverse climatic conditions. Previous studies have shown notable differences among barley cultivars in terms of biomass yields, carbon content and allocation among plant organs. There are lot of possibilities for mitigating climate change in the agricultural sector, through implementation of new technologies and sustainable agricultural practices. One of these technologies is agricultural biotechnology, a promising tool for the development of cultivars that can contribute to mitigation and adaptation to climate change [

15,

16].

Therefore, this study aims to evaluate the potential of different barley cultivars to mitigate climate change by analyzing their capacity for dry matter production, carbon accumulation and distribution within plant biomass. The research focuses on four cultivars; Rex, Lord, Barun and Panonac, grown under continental climatic conditions in eastern Croatia (Osijek city). Understanding these varietal differences contributes to optimizing sustainable biomass management and selecting genotypes with higher carbon sequestration potential within agricultural systems.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Site, Soil Properties, Climate Conditions, Agrotechnical Measures

The experiment was conducted during the 2021 and 2022 growing season at the Agricultural Institute Osijek ((45°31′55.6″ N, 18°44′13.8″ E; 94 m a.s.l.), located in the continental part of Croatia.

The region of Osijek city is characterized by moderately warm humid climate (Cfwbx) according to the Köppen classification [

17]. The long-term averages for the period 1991-2018 indicate a mean air temperature of 11.7 °C, while the average temperature during the growing season reached 18.6 °C. The mean annual precipitation for the same period is 707 mm, with 390 mm recorded during the growing season, and evapotranspiration of 590 mm. Soil water deficit typically occurs from July to September, whereas a surplus occurs during the period from December to March. For the analysis of weather conditions and the calculation of agro-climatic indicators during the study period, data on mean air temperature and precipitation were obtained from the Osijek main meteorological station (h = 88 m n.m., φ = 45°28’ 4˝ N, λ = 18°48’23˝ E) of Croatian Meteorological and Hydrological Service (DHMZ) [

18]

In 2020, prior the experiment, soil samples (0-30cm) were collected to determinate the physical and chemical properties of the soil. The soil at the site has classified as silty-clay texture with a content of 2.33% sand, 56% silt, and 41.67% clay. The water holding capacity is 37.7%, air holding capacity is 10.2%, soil porosity is 47.8%, and bulk density is 1.39 g cm-3. Chemical analysis revealed alkaline soil with moderate 2.3% of humus, 0.11% of total nitrogen, 1.25% of total carbon, 0.06% of total sulfur. The soil was well supplied with plant available phosphorus and potassium, slightly calcareous.

2.2. Barely Cultivars

The experiment includes 4 different barley cultivars bred by the Agricultural Institute Osijek. The studied varieties were:

-

o

Barun - winter barely (Hordeum vulgare L.) an early, two row cultivar with a low habitus (80 cm). Very strong stems, excellent lodging resistance and large, high-quality grains. Sowing rate of 220 kg ha-1 and an average yield of 10 t ha-1

-

o

Lord - winter barely (Hordeum vulgare L.) a medium-late, six row cultivar with a medium tall habitus (95 cm). Notable tolerance to low temperatures and drought, stable performance under stress conditions. Sowing rate of 160 kg ha-1 and an average yield of 10 t ha-1

-

o

Panonac - winter barely (Hordeum vulgare L.) a medium-late, six row cultivar with a medium tall habitus. High adaptability to variable climatic and nutrient limited conditions, achieving stable yields even under reduced nitrogen input. Sowing rate of 200 kg ha-1 and an average yield of 1 t ha-1

-

o

Rex - winter barely (Hordeum vulgare L.) a medium-late, two row cultivar with a low habitus (87-90 cm). Strong stems and good tillering capacity, high tolerance to late season drought. Sowing rate of 200 kg ha-1 and an average yield of 11 t ha-1

More on barley cultivars can be found at [

19]

Standard agrotechnical practices were applied, including soil tillage, fertilization, precise sowing and harvesting operations, as well as routine weed and pest management. All can be found in [

19].

2.3. Determination of Carbon Content in Below Ground and Above Ground Biomass

Biomass sampling was conducted during the barely harvest in July 2021 and June 2022 by destructive sampling method from an area od 1 m2 per cultivar. Sampling of below-ground (roots and stubble) and above-ground biomass (stem, rachis, grain with husk and awns) was conducted in three replicates for each barley cultivar. After sampling all plant material was transported to the laboratory where soil particles were carefully removed from below ground biomass. The above ground biomass was separated into individual morphological components corresponding to the total physiological yield. Each component was then weighed to determinate fresh biomass mass. Subsamples of each plant part were subsequently prepared for laboratory analysis. Total carbon content in the plant biomass was determinated using the dry combustion method, dried in an oven with (Nueve, FN 120, Turkey) at 105 ◦C to a constant weight, weighed (Sartorius CP 64; d = 0.1 mg, Germany), and analyzed using the Vario Macro CHNS (Elementar, 2006). To obtain carbon and nitrogen yields in t/ha, the dry matter yield of each biomass fraction is multiplied by the carbon and nitrogen concentrations of each fraction.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted using SAS statistical software (version 9.1; SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). Differences among the evaluated barely cultivars were assessed using analysis of variance (ANOVA) and when significant effects were detected, Fishers LSD post hoc test was applied to distinguish treatment means. A significance level of p < 0.05 was used for all statistical comparisons. All procedures were preformed within a quality management framework consistent with good laboratory practice (GLP).

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Climate Conditions

Climate conditions during 2021 and 2022 growing season deviated from the recent multi-year average (1991-2018). The mean air temperature of the 2021 is 12.0 °C, which is 0,3 higher than the long-term average of 11,7 °C, and of growing season 18.4 °C. Total annual precipitation amounted 697,8 mm and during the growing season 335 mm, representing 56 mm less than the multi-year mean of 390 mm. Although precipitation showed pronounced monthly fluctuations, the most notable deficit occurred in June. Soil eater deficit was therefore limited to a short period in June, coinciding with elevated temperatures and reduced rainfall.

Table 1.

Monthly air temperature (t, °C) and precipitation (p, mm) values during the 2020/2021 growing seasons.

Table 1.

Monthly air temperature (t, °C) and precipitation (p, mm) values during the 2020/2021 growing seasons.

| 2021. |

I. |

II. |

III. |

VI. |

V. |

VI. |

VII. |

VIII. |

IX. |

X. |

XI. |

XII. |

annual |

|

2,7 |

5,2 |

6,2 |

9,4 |

15,0 |

22,9 |

24,3 |

21,5 |

17,2 |

9,8 |

6,4 |

3,2 |

12 |

| tmax |

17,5 |

22,1 |

22,7 |

26,3 |

29,4 |

38,4 |

38,0 |

37,6 |

32,6 |

28,8 |

24,8 |

17,0 |

28 |

| tmin |

-11.0 |

-9,7 |

-8,1 |

-5,1 |

1,5 |

4,8 |

10,8 |

8,2 |

3,6 |

-2,5 |

-5,3 |

-7,3 |

|

| p |

77,5 |

36,3 |

34,4 |

60,7 |

58,9 |

18,4 |

96,7 |

74,3 |

21,1 |

72,9 |

71,0 |

75,6 |

697,8 |

In contrast, the 2022 was characterized by markedly warmer and dried conditions compared to both 2021 and the long-term reference period. The mean annual air temperature reached 13.0 °C, which is 1,3 °C higher than the 1991-2018 average. Total annual precipitation amounted 585.9 mm, representing a decline of more than 120 mm relative to the long-term average. During the growing season, 348 mm of precipitation was recorded, still below the reference value of 390 mm. Pronounced precipitation deficit occurred in July and August, while an exceptionally high rainfall event was recorded in September. In addition, a severe hailstorm in June further contributed to abiotic stress, negatively affecting plant growth and final yield.

Table 2.

Monthly air temperature (t, °C) and precipitation (p, mm) values during the 2020/2021 growing seasons.

Table 2.

Monthly air temperature (t, °C) and precipitation (p, mm) values during the 2020/2021 growing seasons.

| 2022. |

I. |

II. |

III. |

IV. |

V. |

VI. |

VII. |

VIII. |

IX. |

X. |

XI. |

XII. |

annual |

|

1,7 |

5,6 |

5,8 |

10,7 |

18,7 |

23,7 |

23,7 |

23,1 |

16,6 |

13,9 |

7,9 |

5,0 |

13 |

| tmax |

20,4 |

18,1 |

23,4 |

25,9 |

31,5 |

37,0 |

39,2 |

37,4 |

32,1 |

25,8 |

24,9 |

18,4 |

28 |

| tmin |

-12,6 |

-5,8 |

-10,6 |

-4,4 |

1,6 |

8,9 |

9,2 |

11,0 |

2,0 |

0,2 |

-1,7 |

-6,0 |

|

| p |

7,5 |

28,7 |

6,4 |

35,0 |

66,0 |

77,2 |

19,2 |

30,8 |

148,4 |

1,08 |

78,7 |

77,2 |

585,9 |

Overall, the 2022 exhibited stronger climatic stress, with higher temperatures, lower precipitation and extended soil water deficit, compared with the more moderate conditions of 2021.

3.2. Average Dry Matter and Carbon Yields in Different Growing Seasons

Significant differences in total dry matter yield and carbon sequestration (average of all cultivars) were observed between two studied years. In 2021, average total dry matter yield reached 16,72 t ha

-1, whereas in 2022 it decreased to 11,81 t ha

-1, representing a 29,4% reduction (p<0,05). A similar pattern was recorded for average total carbon content, 7,42 t C ha

-1 in 2021 compared with 5,26 t C ha

-1 in 2022, corresponding to a 29,1% decrease (p<0,05). (

Table 3), indicating that carbon accumulation closely followed biomass production (

Table 3).

A detailed analysis of average individual plant fractions revealed that the most substantial reductions occurred in the grain plus husk and stem components, which correspond to the principal sinks for assimilates during generative phase. Dry matter of grain plus husk decreased from 8,32 t ha

-1 (2021) to 7,84 t ha

-1 (2022), accompanied by sharp decline in carbon content from 3,70 t C ha

-1 to 2,17 t C ha

-1. A similar but less pronounced trend was observed from the stem fraction 4,3 t ha

-1 to 3,48 t ha

-1, with a corresponding decline in carbon content. In contrast, below ground biomass, roots and stubble, remained relatively stable across years, suggesting the root allocation may be less sensitive to seasonal climatic stress. This aligns with findings by [

12], who observed the root biomass in wreath exhibited considerably lower inter annual variability than above ground biomass under drought conditions. The climatic anomalies recorded in 2022 indicating higher temperatures, reduced precipitation and the occurrence of hail storm correspond to conditions known to suppress carbon assimilation, limit grain gilling and reduce overall biomass production. Similar reductions in cereal biomass under heat and drought stress have been reported by [

20] and [

21]. The minimal reduction in root biomass across seasons suggests that barley may adopt a stress avoidance strategy by maintaining below ground biomass even at the expense of above ground growth. This corroborated by observations from [

22], who showed that root derived carbon contributes more significantly to long term soil carbon pools, even when above ground biomass fluctuates due to inter annual climate variability. Thus, the relatively stable root carbon values recorded in this study highlight the importance of root residues for sustaining soil organic carbon under increasingly variable climatic conditions. The magnitude of the reduction in above ground carbon pools observed in 2022 (notably in stems and grain fractions) is indicative of impaired photosynthetic activity and carbon translocation. This is consistent with the findings of [

23], who reported that drought stress leads to decreased carbon assimilation and altered biomass partitioning in cereals.

Table 4.

Mean dry matter (DM) yield and carbon content (C) of different biomass fractions in 2021 and 2022.

Table 4.

Mean dry matter (DM) yield and carbon content (C) of different biomass fractions in 2021 and 2022.

| Parameter |

DM 2021(t ha-1) |

DM 2022(t ha-1) |

LSD (DM) |

C 2021(t ha-1) |

C 2022(t ha-1) |

LSD (C) |

Root

Stubble |

1,62a |

1,60a |

0,37 |

0,70a |

0,70a |

0,17 |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

| 1,20a |

1,16a |

0,17 |

0,52a |

0,50a |

0,07 |

Stem

Rachis |

4,31a |

3,48b |

0,73 |

1,94a |

1,94b |

0,32 |

| 0,32a |

0,19a |

0,23 |

0,15a |

0,09a |

0,10 |

Awns

Grain + husk |

0,94a |

0,55b |

0,16 |

0,42a |

0,24b |

0,07 |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

| 8,32a |

4,48b |

1,02 |

3,70a |

2,18b |

0,46 |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

| Total |

16,72a |

18,81b |

1,95 |

7,42a |

7,42a |

0,82 |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

Overall, the inter annual comparison clearly demonstrates that barley carbon sequestration is highly sensitive to climatic variability, particularly the timing and distribution of rainfall and temperature extremes. The results underscore the need to consider multi-year climatic patterns when evaluating cultivar performance, as single year data may underestimate the variability in biomass and carbon dynamics. The substantial reduction in above ground biomass in 2022, coupled with relatively stable below ground carbon inputs, also reinforces the importance of cultivar selection and residue management as strategies to enhance the resilience of agroecosystems and sustain soil carbon stocks under future climate scenarios.

3.3. Average Dry Matter Yield and Carbon Content of Different Barley Cultivars

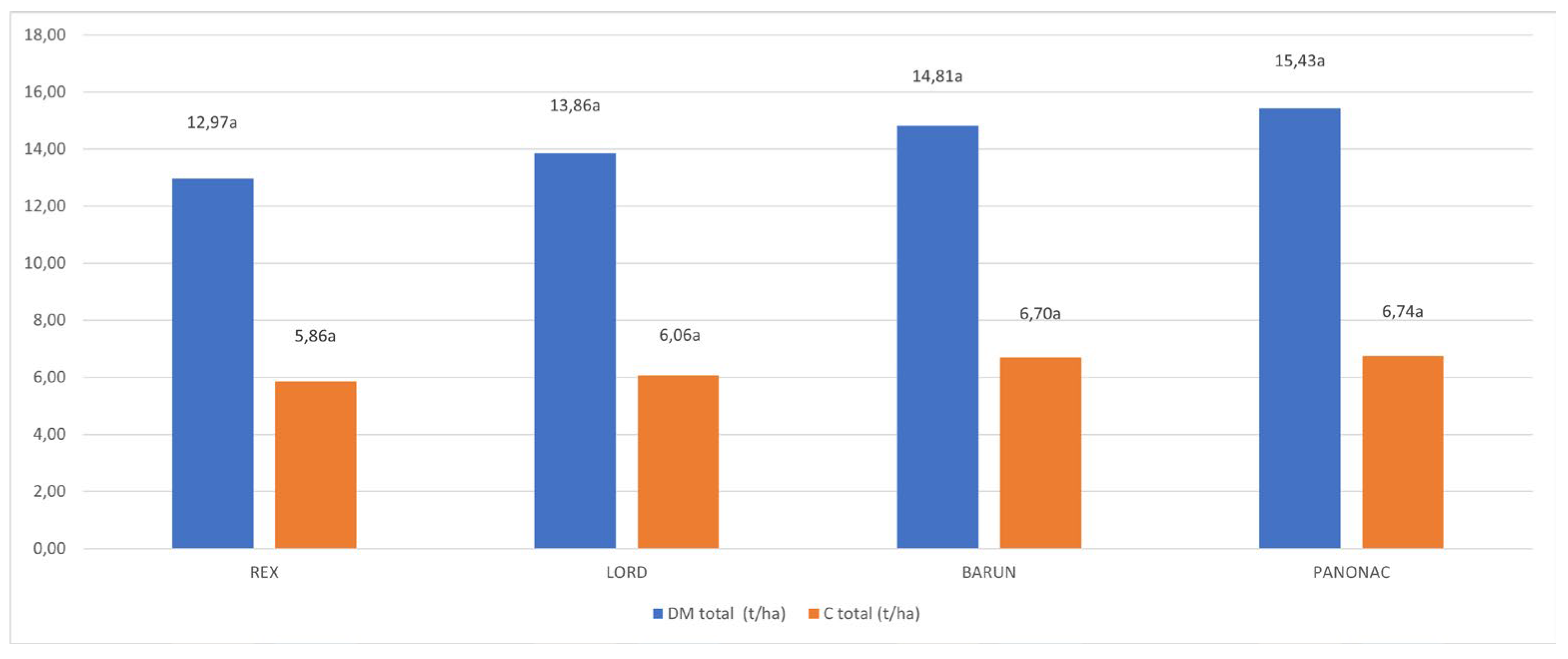

Figure 1. presents the total dry matter and carbon content of the evaluated barley cultivars. Total dry matter ranged from 12,97 t ha

-1 in Rex to 15,43 t ha

-1 in Panonac, while total carbon content varied between 5,86 t C ha

-1 in Rex and 6,74 t C ha

-1 in Panonac. Although Panonac and Barun showed numerically higher values for both traits, no statistically significant differences among cultivars were observed (p < 0,05). Cultivars with deeper and more developed root systems, such as Lord and Panonac, exhibited higher below ground biomass and carbon accumulation, likely reflecting genotypic differences in root architecture and carbon allocation. This observation is consistent with the findings of [

24], who reported the plant genotype influences the quality and composition of root exudates, thereby affecting rhizosphere microbial dynamics and carbon turnover. These results highlight the role of cultivar selection in enhancing root mediated carbon sequestration and improving resilience under variable environmental conditions.

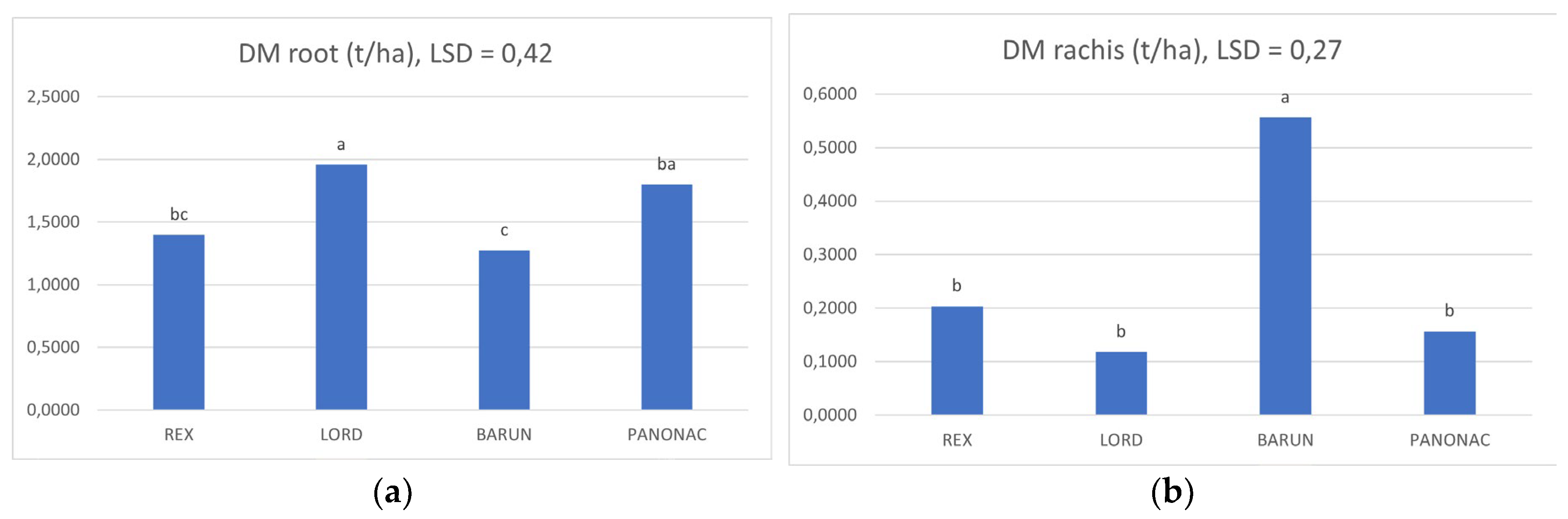

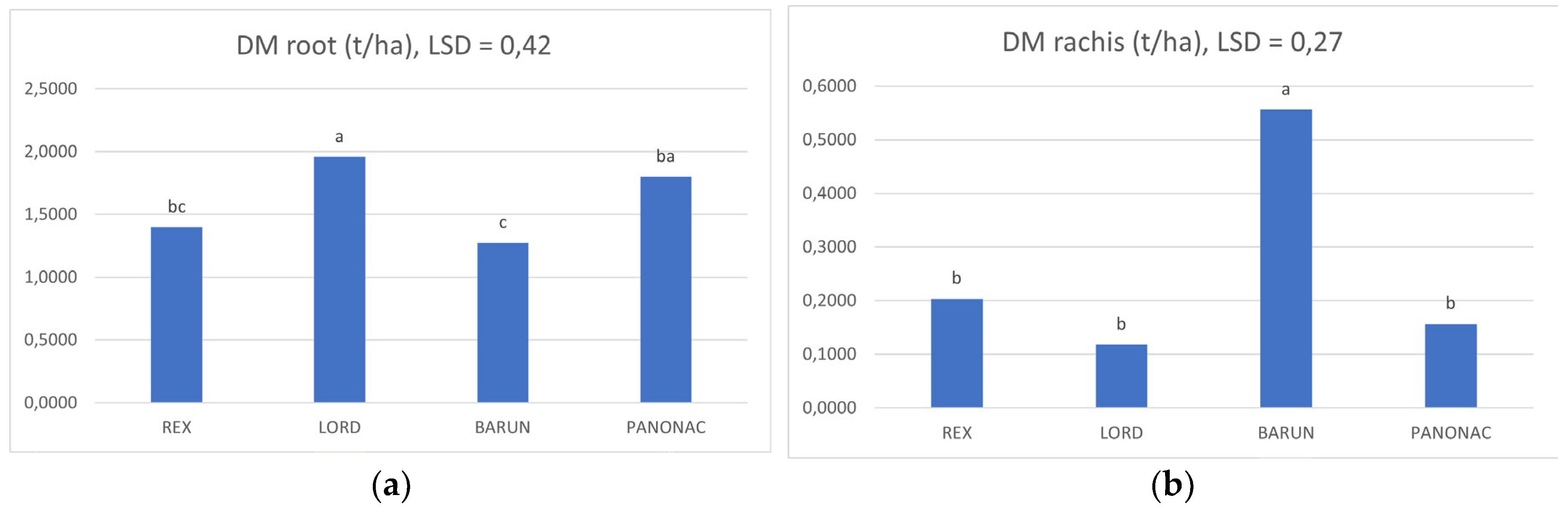

Figure 2. shows the mean dry matter values (across both study years) for individual biomass fractions of the evaluated barley cultivars. Statistically significant differences were detected only for root biomass and rachis (spike axis). Root dry matter was highest in Lord (1.96 t ha

−1), which differed significantly from Barun (1.28 t ha

−1) and Rex (1.40 t ha

−1). Panonac (1.80 t ha

−1) did not differ significantly from Lord, but it did differ from Barun. No significant differences were observed between Panonac and Rex. For the rachis, Barun showed the highest dry matter value (0.56 t ha

−1) and differed significantly from all other cultivars (Rex, Lord, Panonac). For all other biomass components, stem, stubble, awns, and grain plus husk, no statistically significant differences among cultivars were found, despite numerical variability. Stem dry matter ranged from 3.43 to 4.33 t ha

−1, stubble from 1.08 to 1.26 t ha

−1, and awns from 0.64 to 0.87 t ha

−1. Grain plus husk mass was numerically higher in Barun and Panonac, but differences were not statistically confirmed. Overall, although Panonac and Barun achieved higher values in several biomass fractions, significant cultivar effects were confirmed only for root and rachis dry matter, indicating the presence of genotypic differences primarily in below ground allocation and specific structural components.

Figure 2. shows the mean carbon content (averaged across both growing seasons) for individual biomass fractions of the evaluated barley cultivars. Statistically significant differences were observed only for root and rachis carbon content, while no significant differences were detected for the other biomass fractions. Root carbon content ranged from 0.54 t ha

−1 (Barun) to 0.86 t ha

−1 (Lord), with a mean value of 0.70 t ha

−1. Lord and Panonac showed significantly higher root carbon content compared with Rex and Barun, while no significant differences were found between Lord and Panonac, nor between Rex and Barun. For rachis, carbon content ranged from 0.05 t ha

−1 (Lord) to 0.25 t ha

−1 (Barun), with a mean value of 0.12 t ha

−1. Barun exhibited significantly higher rachis carbon content than all other cultivars, among which no significant differences were observed. For all other biomass fractions—stubble, stem, awns, and grain + husk—no statistically significant differences were recorded. Stubble carbon content ranged from 0.46 to 0.55 t ha

−1, stem from 1.57 to 1.94 t ha

−1, awns from 0.29 to 0.38 t ha

−1, and grain + husk from 2.60 to 3.27 t ha

−1. Overall, the results indicate that genotypic differences among cultivars were expressed only in root and rachis carbon content, whereas no significant differences were detected in the stem, stubble, awns, or grain plus husk fractions. Barun and Panonac generally showed higher carbon values across most vegetative tissues, suggesting a greater potential for carbon sequestration and return of organic matter to the soil.

Figure 3.

Mean root (a) and rachis (b) total carbon (t ha-1) across both growing seasons. Error bars (LSD) for root(a) 0,18, rachis (b) 0,12.

Figure 3.

Mean root (a) and rachis (b) total carbon (t ha-1) across both growing seasons. Error bars (LSD) for root(a) 0,18, rachis (b) 0,12.

In the study by [

25], barley roots were shown to contribute to the formation of stable soil organic matter to a much greater extent than above ground residues. In experiments conducted on eroded soils, between 35% and 65% of root derived carbon became mineral-associated, whereas shoot residues decomposed more rapidly and exhibited greater carbon losses, with only a small portion remaining stored in the soil. These findings highlight the importance of roots and stubble as key components of carbon sequestration, particularly in the context of sustainable biomass and soil management.

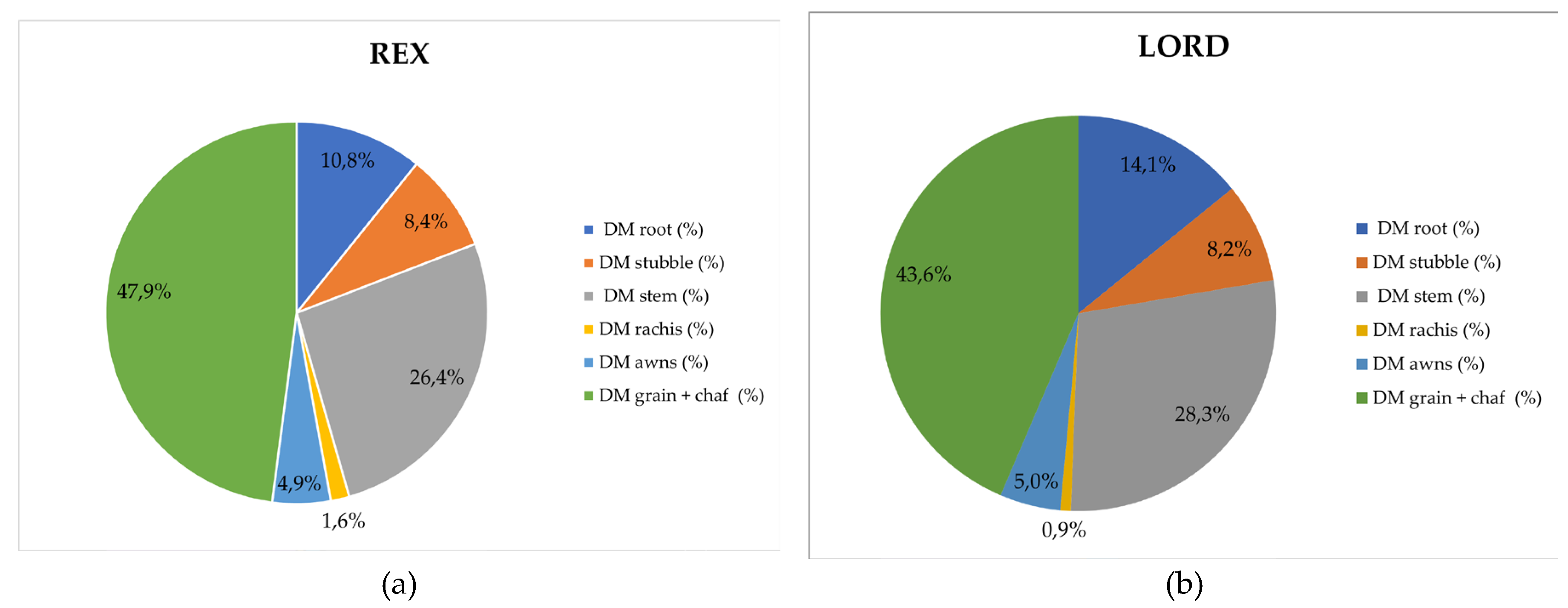

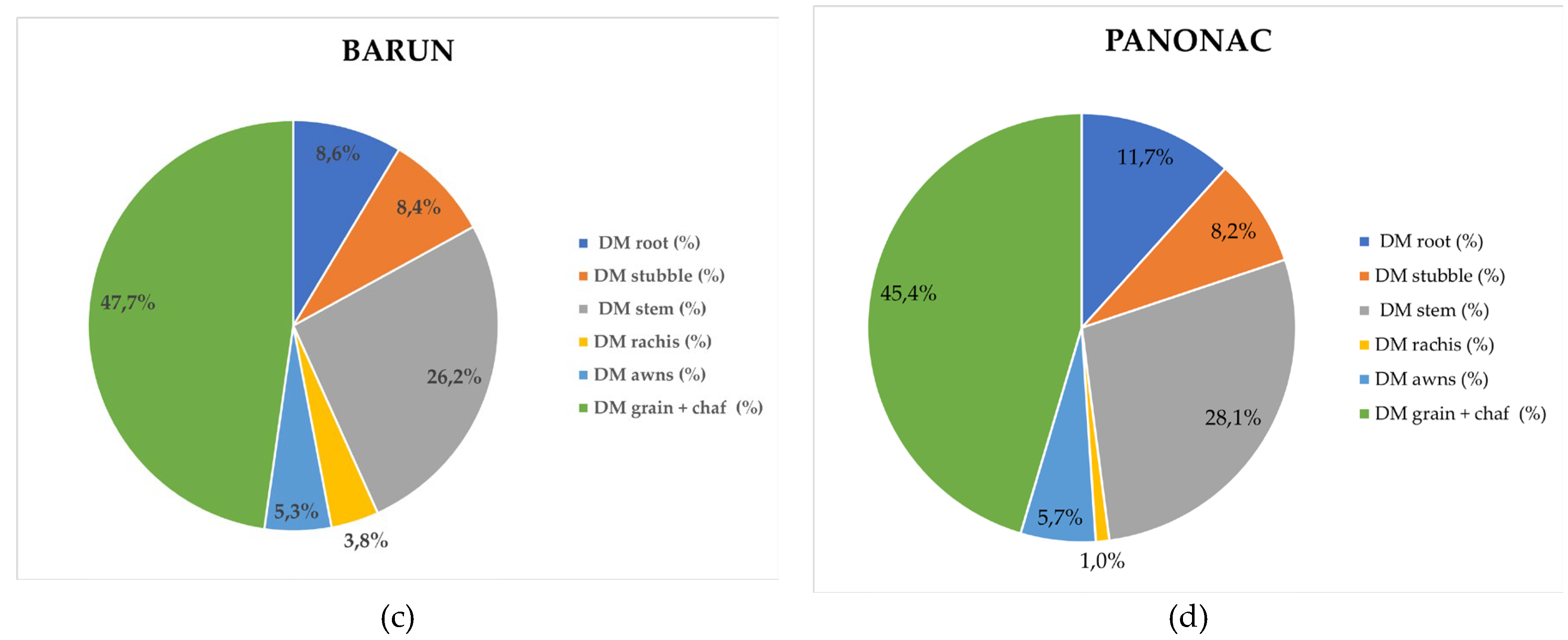

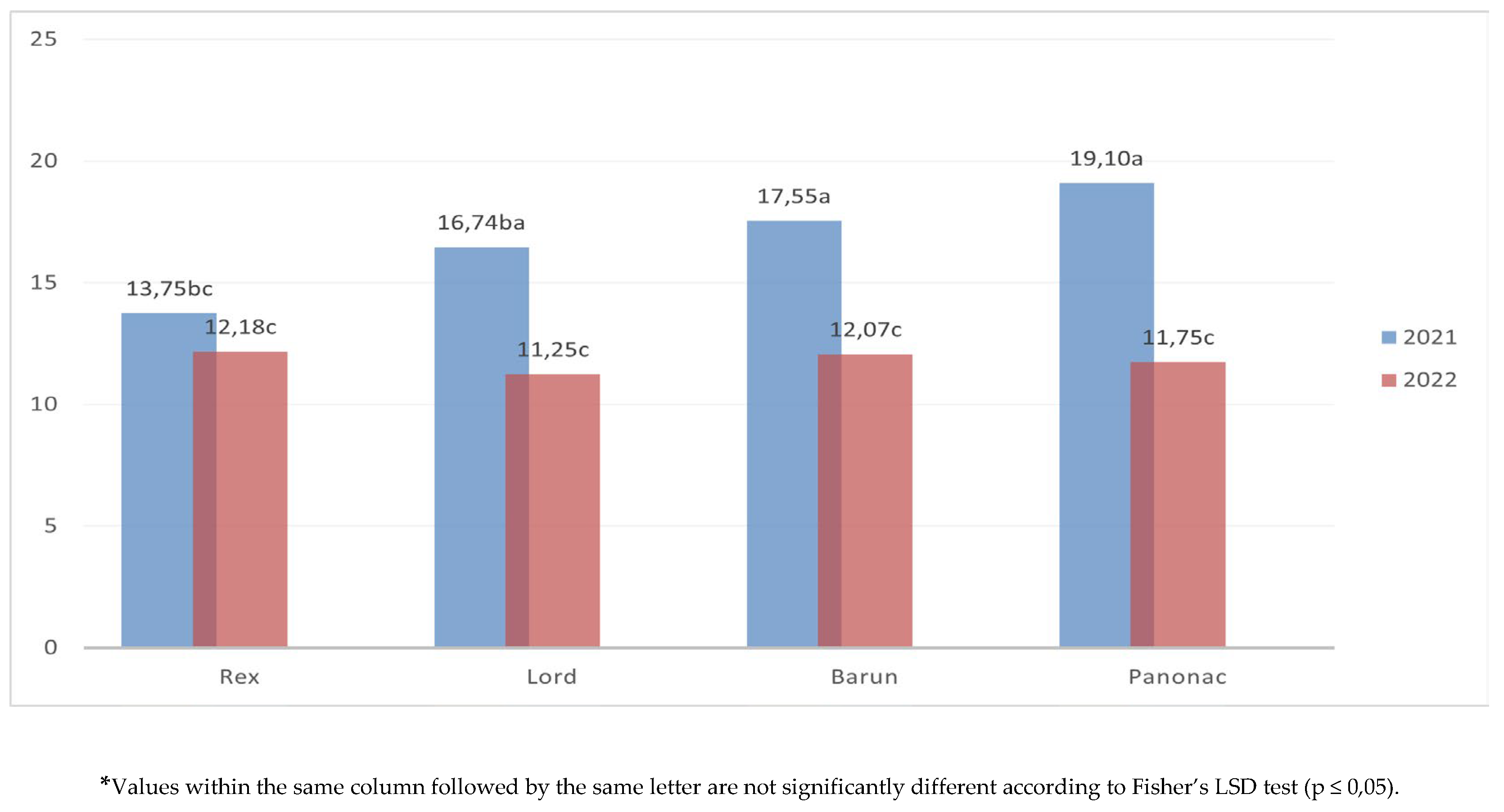

3.4. Redistribution of Dry Matter and Carbon Among Plant Organs

Based on the presented redistribution of total barely biomass dry matter across individual plant parts (

Figure 4), certain differences were observed among the analyzed cultivars. In the cultivar Rex, the proportion of dry matter was distributed as follows: grain with chaff (47.9%), stem (26.4%), root (10.8%), stubble (8.4%), awns (4.9%), and rachis (1.6%). In the cultivar Lord, grain with chaff accounted for 43.6%, stem 28.3%, root 14.1%, stubble 8.2%, awns 5.0%, and rachis 0.9%. The cultivar Barun showed the following order: grain with chaff (47.7%), stem (26.2%), root (8.6%), stubble (8.4%), awns (5.3%), and rachis (3.8%). In the cultivar Panonac, the distribution was: grain with chaff (45.4%), stem (28.1%), root (11.7%), stubble (8.2%), awns (5.7%), and rachis (1.0%). Across all cultivars, the highest share of dry matter was found in the grain with chaff (43.57% - 47.95%), indicating that the plant directs most of its accumulated biomass into the generative organs. The largest proportion of grain with chaff was recorded in Rex (47.9%) and Barun (47.7%), while the lowest proportion was found in Lord (43.6%). The proportion of stems was relatively uniform among the cultivars, ranging from 26,24% to 28.31%. Slightly higher values were recorded for Lord and Panonac, whereas Rex and Barun showed somewhat lower stem dry matter shares. The proportion of root dry matter within total biomass ranged from 8.61% to 14.14%. The cultivar Lord had the highest root biomass share compared to the other cultivars, indicating a potentially greater contribution to below ground carbon inputs. Other plant organs, stubble, rachis and awns accounted for less than 9% of total biomass. However, despite their smaller share, these components contribute meaningfully to the overall quantity of crop residues remaining in the field after harvest.

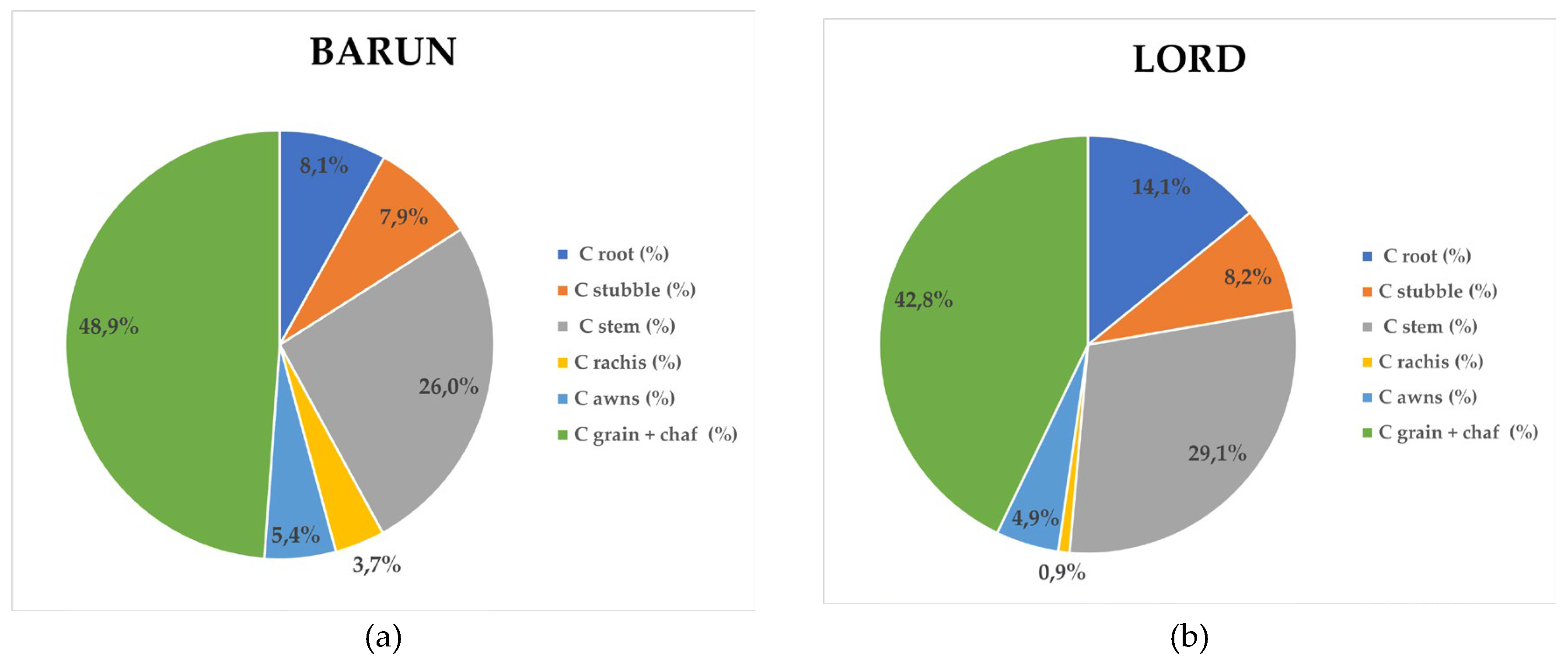

The distribution of sequestered carbon among barley plant organs (

Figure 5.4.2) followed a pattern similar to that observed for dry matter allocation. In Rex, carbon was primarily allocated to grain with chaff (48.7%), followed by stem (26.8%), root (10.1%), stubble (7.8%), awns (5.0%), and rachis (1.6%). In Lord, the proportions were 42.8% (grain with chaff), 29.1% (stem), 14.1% (root), 8.2% (stubble), 4.9% (awns), and 0.9% (rachis). The cultivar Barun exhibited the sequence: grain with chaff (48.9%), stem (26.0%), root (8.1%), stubble (7.9%), awns (5.4%), and rachis (3.7%). In Panonac, carbon allocation was distributed as follows: grain with chaff (44.8%), stem (28.7%), root (11.7%), stubble (8.2%), awns (5.3%), and rachis (1.0%). The carbon share in grain with chaff ranger from 42.84 – 48.85%, with the highest values observed in Rex (48.7%) and Barun (48.9%). These results mirror the dry matter distribution but simultaneously highlight that most of the stored carbon is located in the plant fraction removed from the field at harvest, thus not contributing to long-term soil organic matter accumulation. Similar results for different winter wheat cultivars on same location was determined, where total biomass was composed of 40–47% grain, 10–11% roots, 32–36% stems + leaves, 9–11% chaff, and 1–2% spindle [

26]. From a carbon sequestration standpoint, the most relevant plant components are the stem, root and stubble. Carbon allocation to the stem ranger from 26.0% (Barun) to 29.1% (Lord) of total biomass, indicating that sustainable residue management and stem incorporation can support substantial long term soil carbon storage. Root associated carbon ranged from 8.1% (Barun) to 14.1% (Lord), underscoring the cultivar Lords greater potential for stable below ground carbon inputs. Carbon associated with the remaining plant parts accounted less than 6% of total biomass.

Overall, the redistribution patterns of dry matter and sequestered carbon in barely biomass showed strong mutual dependance, as plant organs with the highest dry matter shares also contained the highest proportions of carbon. This distribution reflects physiological processes characteristic of the generative growth phase. During grain filling, barely directs most photosynthetically derived assimilates, carbon rich organic compounds, toward the grain, which represents the final stage of reproductive development [

27]. Although metabolically less active, the chaff remains physically linked to the grain and together they form the largest reservoir of dry matter and carbon within the plant. Despite this dominance, carbon stored in grain and chaff does not contribute to long-term soil organic matter accumulation, as this fraction is removed from the field at harvest. In contrast, the stem, root, and stubble components incorporated into soil or retained as residues represent the most relevant contributors to carbon sequestration. Our findings indicate that the cultivar Lord exhibits the highest potential for below ground and residue-based carbon storage, while Rex shows the lowest. Long term evidence supports the role of root and residue retention in enhancing soil carbon stocks. A 33-year trial demonstrated that a combination of no-till management and residue retention, including roots, stems, and stubble, resulted in the highest net soil carbon sequestration (4.5 Mg CO

2) [

28]. Similarly, in a jute, rice, wheat rotation system, root and stubble retention increased soil carbon storage capacity to an average of 22 Mg ha

-1, confirming the soil’s function as a long-term carbon reservoir [

29]. Differences in biomass production and carbon accumulation among barley cultivars are well documented. [

30] reported significant variability, with stress tolerant cultivars achieving higher biomass and carbon content, while sensitive cultivars performed poorly. The superior carbon accumulation observed in BH-902 demonstrated the importance of cultivar specific morphological traits. [

23] highlighted that cultivars with greater biomass and more developed root systems can increase carbon sequestration by over 20% compared with standard varieties. Residual biomass, especially roots and stubble, substantially contributes to soil organic matter and long-term stability [

9,

29]. As chaff remains on the field, its proportion further influences a cultivars agroecological value. Climatic stress also sharps carbon storage potential. [

2,

31] showed that above ground biomass is more sensitive to stress than below ground biomass, directly affecting total carbon input to soil. Biomass partitioning strongly influences sequestration capacity [

2,

20,

27], with cultivars maintaining higher biomass under stress, largely due to a strong root system, showing the greatest long term carbon storage potential.

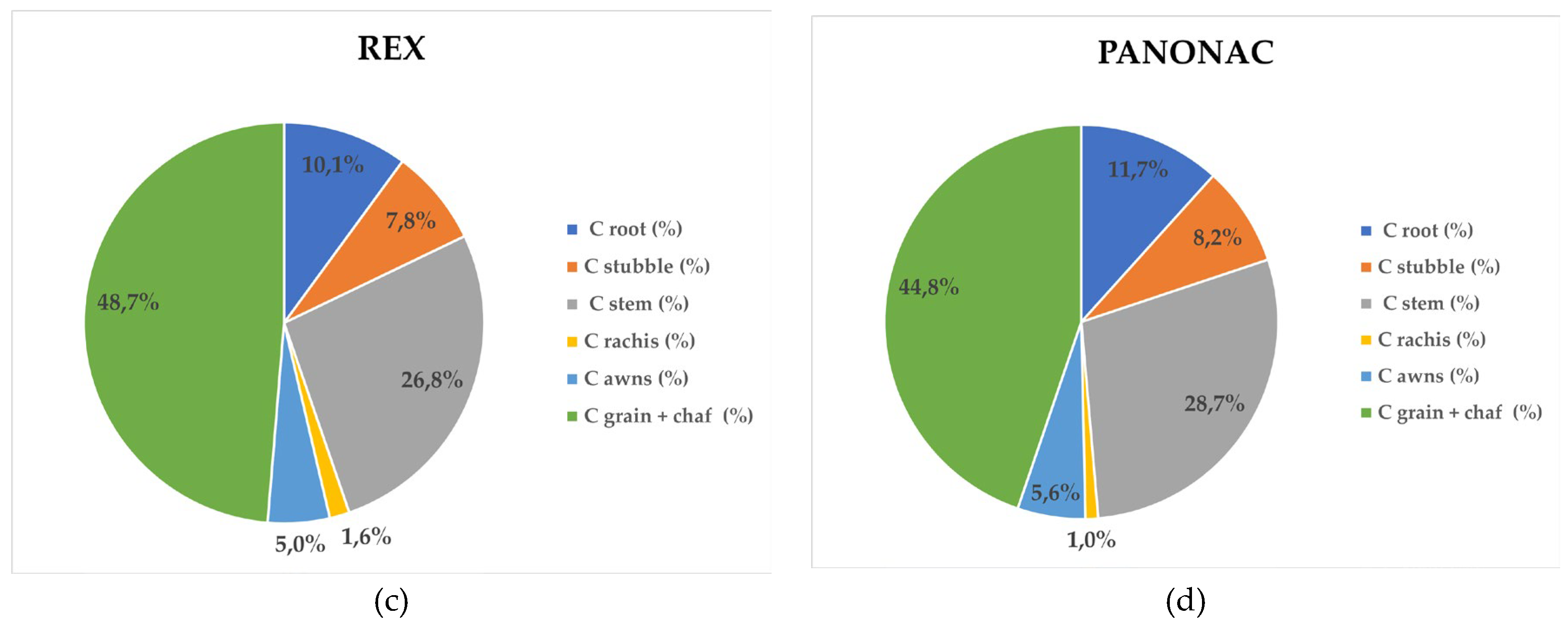

3.5. Effect of the Interaction Between Barely Cultivars and Growing Seasons on Dry Matter Yield and Carbon Content

The average values of total dry matter content among cultivars and between two studied years (

Figure 6). In 2021, a significantly higher dry matter yield was recorded for all cultivars except Rex, which showed similar yields in both years. The highest dry matter yields in 2021 were obtained by Panonac (19.10 t ha

-1), the lowest in Rex (13.75 t ha

-1). In 2022, differences among cultivars were not statistically significant, with dry matter yield ranging from 11.25 t ha

-1 (Lord) to 12.18 t ha

-1 (Rex).

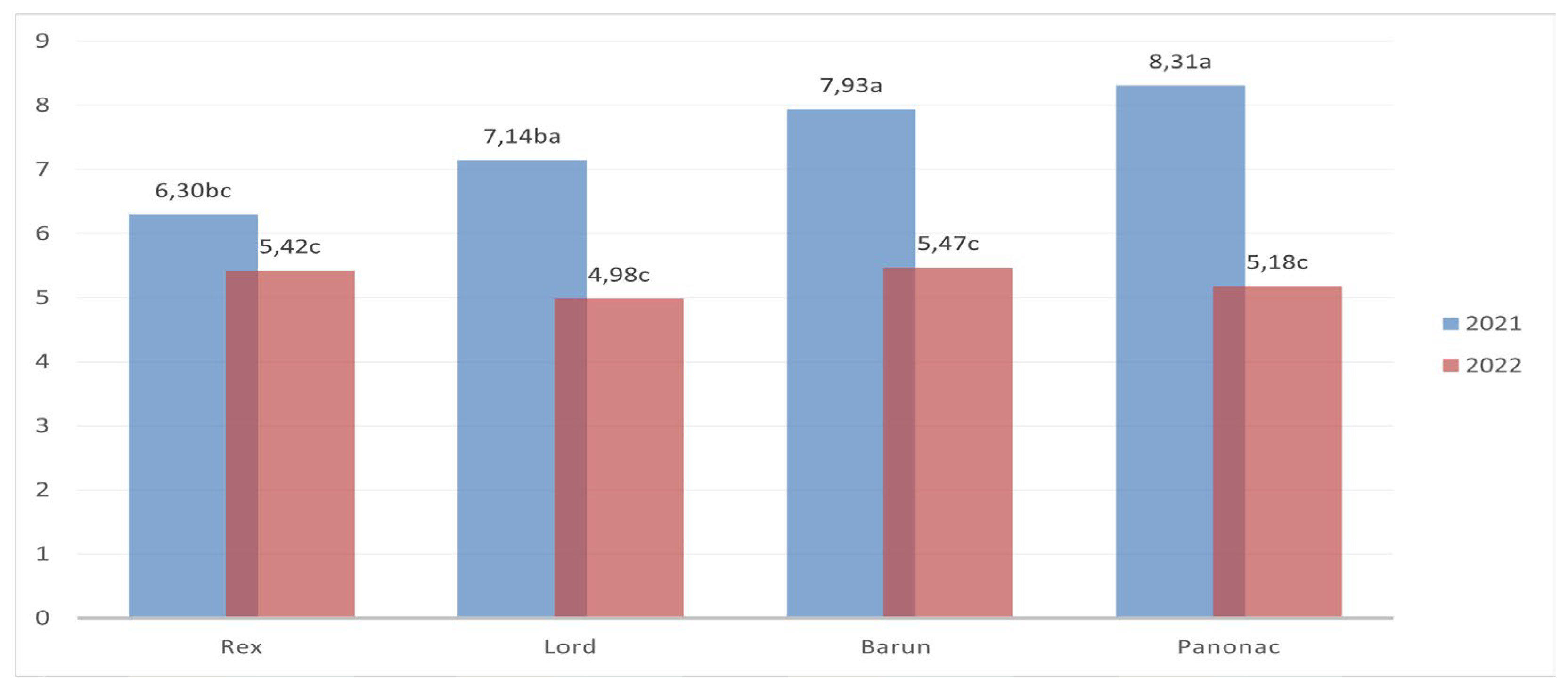

A similar pattern was observed for total carbon content (

Figure 7.), which closely followed dry matter yield. Significant differences between years were recorded for all cultivars except Braun. In 2021, Panonac and Barun accumulated the highest amounts of carbon (8.31 and 7.93 t ha

-1), whereas Lord and particularly Rex exhibited lower values (7.14 and 6.30 t ha

-1). In contrast, carbon content in 2022 was generally lower (4.98 – 5.47

t ha

-1), with no statistically significant differences among cultivars.

These results demonstrate that the influence of growing season plays a decisive role in determining both biomass production and carbon accumulation. The interaction analysis further confirmed that differences among cultivars cannot be interpreted independently of seasonal conditions. Although all cultivars exhibited a measurable capacity for carbon sequestration, the intensity and distribution of biomass varied between years, with some cultivars showing greater interannual variability than others. This indicates that the stability of biomass and carbon allocation between above ground and below ground organs is closely linked to environmental conditions in each season. Since all cultivars were grown under identical field conditions, the observed differences in dry matter yield and carbon sequestration can be attributed primarily to cultivar specific morphological and physiological traits.

4. Conclusions

This study was based on the assumption that different barely cultivars would exhibit variation in dry matter yield, the amount of sequestrated carbon and its distribution within the plant. The experiment, conducted on four barley cultivars (Hordeum vulgare), confirmed this hypothesis. Biomass yield and carbon accumulation varied markedly between the two growing seasons; demonstrating the climatic conditions strongly influence biomass production. These findings highlight the sensitivity of biomass production and carbon sequestration to climate variability and emphasize the need to adapt cultivar selection and agronomic practices to increasingly frequent climatic stresses. Genotypic differences were also evident; both dry matter and total bound carbon varied significantly among cultivars and between years, demonstrating the influence of cultivar specific traits on biomass formation and carbon sequestration potential. Cultivars Panonac and Barun showed the most favorable overall potential, while Rex cultivar exhibited lower but stable performance. The distribution of biomass and carbon within the plant was closely linked, with roots, stems and stubble representing the key fractions contributing to long term sail carbon storage. Because the removal of grain limits its sequestration role, the choice of cultivar becomes increasingly important for sustainable production. Overall, the findings demonstrated that cultivars differences influence biomass and carbon sequestration, biomass yield depends on climate, cultivars Panonac and Barun show the strongest potential and cultivar selection is essential for long term sustainability and climate smart agriculture.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.B.; Methodology, D.B. & N.B.; Software, K.K. & D.B.; Formal analysis, D.B., N.B. & K.K.; Investigation, D.B., M.G. & N.B.; Writing—K.K., D.B.; Writing—review & editing, K.K., D.B. & N.B.; Supervision, T.K. & Z.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by European union from Operational Program Competitiveness and cohesion of European Regional Development Fund via project via project “Production of food, biocomposites and biofuels from cereal sinthecircular bioeconomy” (grantnumberKK.05.1.1.02.0016). The publication was supported by the Open Access Publication Fund of the University of Zagreb Faculty of Agriculture.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- IPCC (2023). AR6 Synthesis Report. Climate Change 2023. https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/syr/ (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- Ngidi, D. D., Hlongwane, N. S., Mthembu, M. S. (2024). Comparative analysis of carbon sequestration potential and yield in selected barley (Hordeum vulgare L.) cultivars. Emerging Trends in Climate Change (ETCC), 2(2), pp. 14–25.

- Piccoli I., Schjønning P., Lamandé M., Zanini F., Morari F. 2019. Coupling gas transport measurements and X-ray tomography scans for multiscale analysis in silty soils. Geoderma, 338: pp. 576–584. [CrossRef]

- Sanderman J., Hengl T., Fiske J.G. (2017). Soil carbon dept of 12,000 years of human land use. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 114 (36) pp. 9575-9580. [CrossRef]

- Lal R., Negassa W., Lorenz K. (2015). Carbon sequestration in soil. U Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability (Sv. 15, pp. 79–86).

- Lar R. (2003). Global potential of soil carbon sequestration to mitigate the greenhouse effect. Critical Reviews in Plant Sciences 22(2): pp. 151-184. [CrossRef]

- Gregorich E.G., Rochette P., VandenBygaart A.J., Angers D.A. 2005. Greenhouse gas contributions of agricultural soils and potential mitigation practices in Eastern Canada. Soil Tillage Res. 83(1): pp. 53–72. [CrossRef]

- Lal R., (2018). Digging deeper: A holistic perspective of factors affecting soil organic carbon sequestration in agroecosystems. Review. Glob Chang. (8): pp. 3285-3301. [CrossRef]

- Sumitray R., Sahu G., Bisen N. (2022). Carbon Sequestration and Its Effect on Soil Quality and Crop Productivity: A Review International Journal of Multidisciplinary Research and Explorer (IJMRE), Vol. 1(3), pp. 41–47.

- NIR - National inventory report (2024). Croatian greenhouse gas inventory for the period 1990 – 2022. Ministarstvo gospodarstva i održivog razvoja, Zagreb, Hrvatska.

- Jungić D. i Husnjak S. (2024). Manjak vode u tlu pri uzgoju lucerne, rajčice i vinove loze u Osječko-Baranjskoj županiji u uvjetima klimatskih promjena. Agronomski glasnik. Volume 86, No. 3/2024.

- Bilandžija, D., i Martinčić, S. (2021). Agroclimatic conditions of the Osijek area during referent (1961–1990) and recent (1991–2018) climate periods. Hrvatski meteorološki časopis, pp. 55–64. [CrossRef]

- Bilandžija D., Galić M., Zgorelec Ž. (2023). Tlo i klimatske promjene. Proizvodnja hrane, biokompozita i biogoriva iz žitarica u kružnom gospodarstvu. Zadar, Sveučilište u Zadru, pp. 261-304.

- Lal R. (2004). Soil carbon sequestration to mitigate climate change. Geoderma, 123(1–2): pp. 1–22. [CrossRef]

- Kätterer T. (2024). Carbon sequestration in Swedish cropland soils. EU Research. [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, N.; Lipper, L.; Zilberman, D. Economics of Climate Smart Agriculture: An Overview. In Climate Smart Agriculture— Building Resilience to Climate Change; Lipper, L., McCarthy, N., Zilberman, D., Asfaw, S., Branca, G., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 31–49.

- Gajić-Capka, M.; Zaninović, K. Climate. In Climate Atlas of Croatia 1961–1990. 1971–2000; Zaninović, K., Ed.; Meteorological and Hydrological Service: Zagreb, Croati, 2008; pp. 11–15.

- 18. DHMZ Državni hidrometeorološki sustav. https://meteo.hr/klima.php?section=klima_pracenje¶m=srednja_temperatura (accessed on 22 June 2025).

- Poljoprivredni institut Osijek (2020). Katalog Poljoprivrednog instituta Osijek: Proljeće 2020 - KUKURUZ | SOJA | SUNCOKRET LUCERNA | JARI JEČAM, Poljoprivredni institut, Osijek | 2020. https://www.poljinos.hr/wpcontent/uploads/2022/04/POLJINOS_KATALOG_JESEN_2021.pdf (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- Bilandžija, D.; Martinčić, S. Agroclimatic conditions of the Osijek area during referent (1961–1990) and recent (1991–2018) climate periods. Hrvatski Meteorološki Časopis 2021. in press. Author 1, A.; Author 2, B. Book Title, 3rd ed.; Publisher: Publisher Location, Country, 2008; pp. 154–196. [CrossRef]

- Shrestha A., Fendel A., Nguyen T.H., Adebabay A., Kullik A.S., Benndorf J., Leon J., Naz A.A. (2022). Natural diversity uncovers P5CS1 regulations and its role in drought stress tolerance and yield sustainability in barley. Plant, Cell & Environment, Volume 45, Issue 12; pp. 3523-3536. [CrossRef]

- Tan Z., Wang S., Eei F. Li C., Fu F., Wang L. (2025). The biomass carbon sequestration potential in China’s drylands. Earth’s Future, 13.

- Kaštovská E., Choma M., Angst G., Remus R., Augustin J., Kolb S., Wirth S. (2004). Root but not shoot litter fostered the formation of mineral-associated organic matter in eroded arable soils. Soil and Tillage Research. Volume 235. [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues C.I.D., Brito L.M., Nunes L.J.R. (2023). Soil Carbon Sequestration in the Context of Climate Change Mitigation: A Review. Soil syst., 7(3), 64. [CrossRef]

- Wang W. i Dalal R. (2006). Carbon inventory for cereal cropping system under contrasting, nitrogen fertilization and stubble management practices. Soil and tillage research. Volume 91, Issues 1-2; pp. 68-74. [CrossRef]

- Bilandžija, D.; Zgorelec, Ž.; Galić, M.; Grubor, M.; Krička, T.; Zdunić, Z.; Bilandžija, N. Comparing the Grain Yields and Other Properties of Old and NewWheatCultivars. Agronomy 2023, 13, 2090. [CrossRef]

- Bašić F., Herceg N. (2010). Temelji uzgoja bilja. Synopsis, Zagreb.

- Singh A., Behera M., Mazumdar S., Kundu D.K. (2019). Soil carbon sequestration in long-term fertilization under jute-rice-wheat agro-ekosystem. Communications in Soil Science and Plant Analysis. Volume 50, Issue 6. [CrossRef]

- Yadav, M. R., Kumar, S., Behera, B., Yadav, V. P., Khrub, A. S., Yadav, L. R., Gupta, K. C., Meena, O. P., Baloda, A. S., Raza, M. B., et al. (2023). Energy-carbon footprint, productivity and profitability of barley cultivars under contrasting tillage-residue managements in semi-arid plains of North-West India. Journal of Soil Science and Plant Nutrition, 23(3), pp. 1109–1124. [CrossRef]

- Krishnan, P., Patra A.K. i Kumar M., (2022). Soil carbon sequestration in context of climate change: A review of strategies, indicators and limitations. Soil System, 6(2), pp. 33.

- Rogers C.W., Adams C.B., Marshall J.M., Hatzenbuehler P., Thurgood G., Dari B., Loomis G. Tarkalson D.D. (2024). Barely residue biomass, nutrient content, and relationships with grain yield. Crop Ecology, Management & Quality. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).