Submitted:

19 December 2025

Posted:

22 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Research Motivation and Purpose

1.2. Literature Review and Research Gap

- Systemic: Covers both technical (EV component) and systemic (Infrastructure, Policy) failure modes.

- Comparative: Explicitly models the risk profile divergence between developed and emerging markets.

- Actionable: Utilizes a multi-criteria decision-making method (AHP) to prioritize corrective actions based on strategic criteria (Cost, Time, Impact) rather than a single risk score.

2. Theoretical Framework and Methodological Foundation

2.1. Sustainable Development in Automotive Engineering

- Environmental (E): Failure modes such as "Insufficient battery recycling" directly challenge the environmental sustainability of EVs.

- Social (S): "Market/customer resistance," "Safety risks due to battery thermal events," or "Distributional effects of pollution" affect social acceptance and equity [18].

- Governance (G): "Regulatory volatility" and "Lack of national charging standards" relate to the stability and effectiveness of governance structures.

- Intensive Type (Usage): Resulting from the actual usage over the life cycle, where the clear sustainability advantage of EVs is potentially diminished by safety risks in accidents [20] or aspects of energy security.

- Extensive Type (Production/Stock): Influenced by the accumulation of knowledge (learning-effects) and by the beneficial effects of charging infrastructure development [15].

2.2. Electrification Transformation, the Continuum Redefinition of ICE-EV Transition

2.3. Risk Assessment Tools: FMEA and Beyond

2.4. Al-Enabled Dynamic Risk Management

- Occurrence (ΔO): Predictive Maintenance systems and Digital Twins can use real-time data to forecast failures, effectively reducing the Occurrence score (O′) of unexpected component failures.

- Detection (ΔD): Al-driven diagnostics drastically reduce the Mean Time To Detect (MTTD) a defect, providing quantitative proof for the reduction of the Detection score (D) by offering timely alerts.

3. Research Method

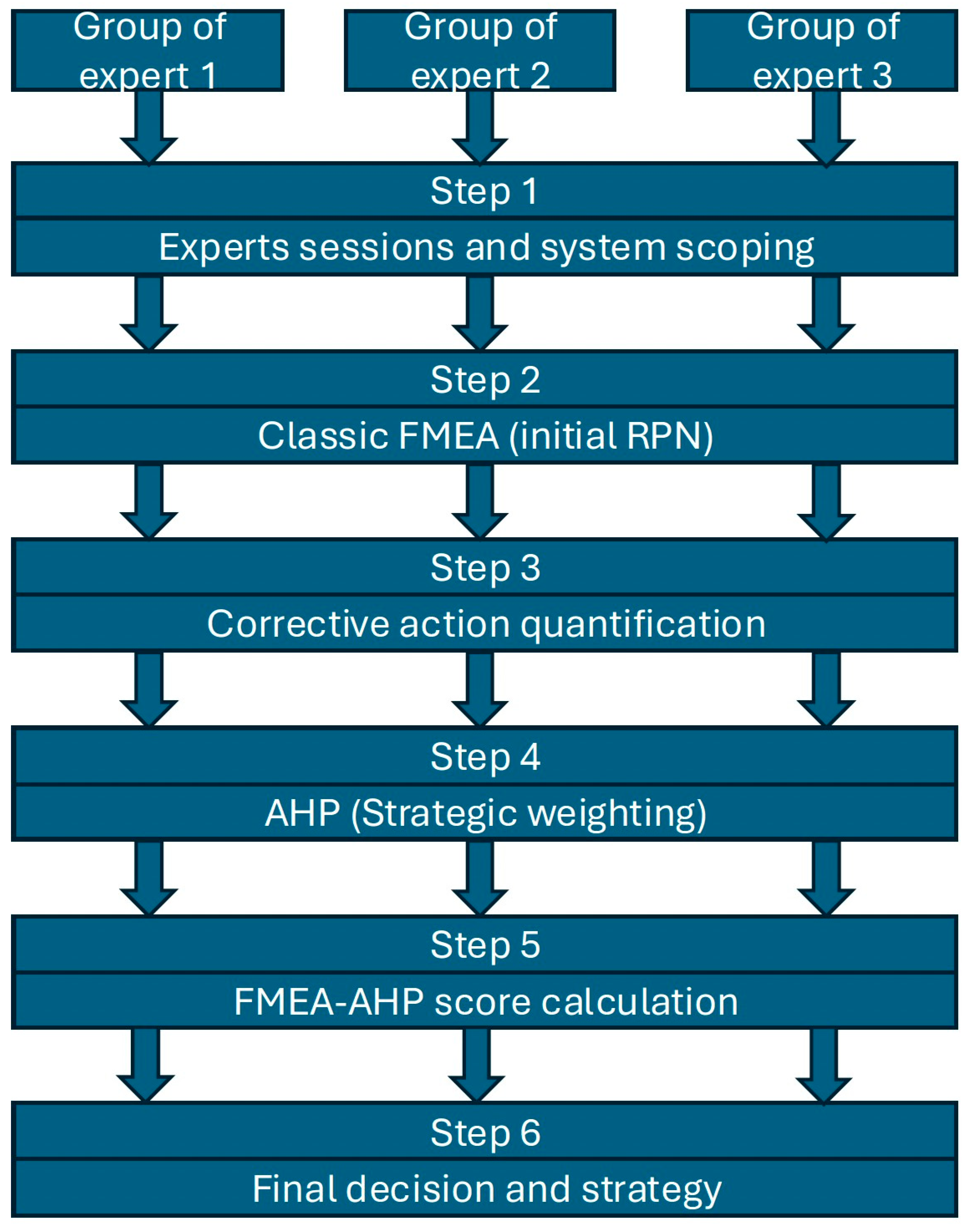

3.1. Overview of Methodological Steps

- Definition of scope and system decomposition (technology, policy, infrastructure, consumer behavior).

- Identification of failure modes for each subsystem.

- Scoring (S, O, D) and computation of RPNs (qualitative emphasis).

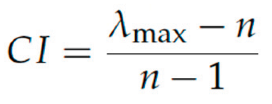

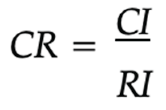

- Integration of AHP for criterion weighting and Consistency Ratio (CR) calculation.

- Comparative analysis between developed and emerging market profiles.

- Interpretation using adaptive risk management principles.

4. Detailed FMEA and Integration with AHP Toward a Hybrid Model FMEA-AHP

4.1. FMEA Step 1: Planning and Structure Analysis

- Technology subsystem: battery systems, power electronics, vehicle software, thermal management.

- Policy subsystem: emissions regulations, incentives, tariffs, trade policy.

- Infrastructure subsystem: public and private charging stations, grid capability, maintenance network.

- Consumer subsystem: purchasing power, usage patterns, range expectations, service ecosystems.

4.2. FMEA Corrective Actions

- Severity (S): measures the impact of the failure on safety, system functionality, customer satisfaction, or market adoption.

- Occurrence (O): estimates the probability that the failure mode will occur within a given time or operating cycle.

- Detection (D): represents the likelihood that the failure will be detected and mitigated before it generates a critical effect.

- Reducing Severity (S) through design improvements, redundancy, or advanced safety mechanisms (e.g., thermal protection systems in batteries).

- Reducing Occurrence (O) by addressing the root cause of the failure (e.g., diversification of suppliers to reduce dependency on rare materials).

- Reducing Detection (D) by enhancing monitoring and diagnostic capabilities (e.g., predictive maintenance using lot sensors, simulation-based validation, or digital twins).

- Supply-side mitigations: actions targeting sourcing and procurement vulnerabilities.

- Infrastructure investments: initiatives that improve the external environment of product operation.

- Technological strategies: improvements at the design and process level.

- Policy interventions: regulatory or institutional measures to stabilize the transition context.

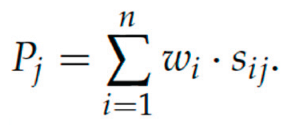

4.3. Hybrid Model FMEA-AHP

- Define the goal of the decision: prioritize the corrective actions for the transition program.

- Select criteria: e.g., reduction in Severity (ΔS), reduction in Occurrence (ΔO), improvement in Detection (ΔD), cost feasibility, time-to-implement, social impact.

- Construct pairwise comparison matrices among criteria according to expert judgment (Saaty scale).

- Compute normalized priority vector (weights wi) as the principal right eigenvector of the pairwise matrix (or by geometric mean method), and validate the consistency using the Consistency Ratio (CR).

- Score each corrective action against criteria (qualitative or semi-quantitative scores Sij).

- Compute global priority for each action:

| Failure mode | S | O | DS′ O′ D′ | |||

| Battery shortages | 9 | 7 | 4 | 9 | 4 | 3 |

| Battery thermal risk | 10 | 3 | 3 | 10 | 2 | 2 |

| Insuff. charging infra. | 8 | 6 | 5 | 8 | 4 | 3 |

| Insuff. battery recycling | 7 | 5 | 5 | 7 | 3 | 3 |

| Software bugs | 9 | 4 | 4 | 7 | 3 | 3 |

| Failure mode | ∆S | ∆O | ∆D |

| Battery shortages | 9 − 9 = 0 | 7 − 4 = 3 | 4 − 3 = 1 |

| Battery thermal risk | 10 − 10 = 0 | 3 − 2 = 1 | 3 − 2 = 1 |

| Insuff. charging infra. | 8 − 8 = 0 | 6 − 4 = 2 | 5 − 3 = 2 |

| Insuff. battery recycling | 7 − 7 = 0 | 5 − 3 = 2 | 5 − 3 = 2 |

| Software bugs | 9 − 7 = 2 | 4 − 3 = 1 | 4 − 3 = 1 |

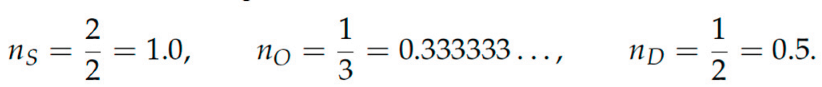

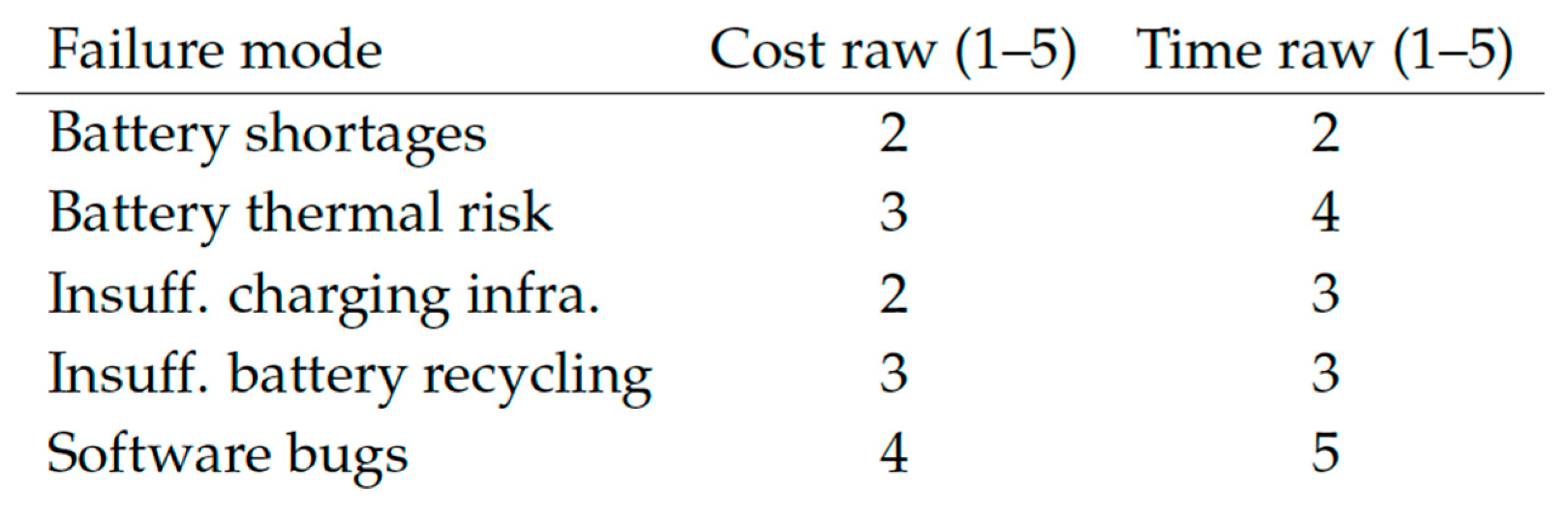

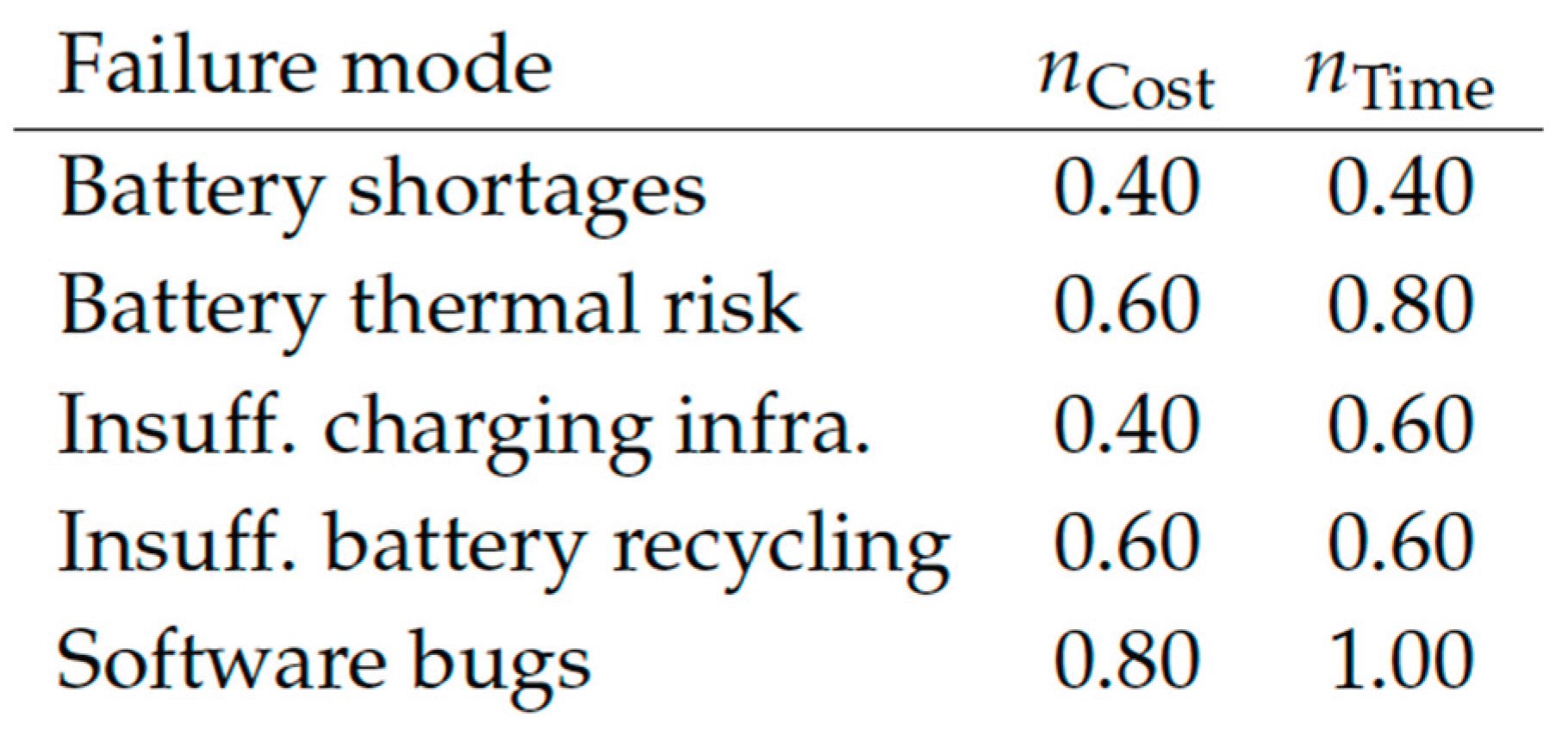

| Failure mode | nS | nO | nD |

| Battery shortages | 0/2 = 0.00 | 3/3 = 1.00 | 1/2 = 0.50 |

| Battery thermal risk | 0/2 = 0.00 | 1/3 ≈ 0.333333 | 1/2 = 0.50 |

| Insuff. charging infra. | 0/2 = 0.00 | 2/3 ≈ 0.666667 | 2/2 = 1.00 |

| Insuff. battery recycling | 0/2 = 0.00 | 2/3 ≈ 0.666667 | 2/2 = 1.00 |

| Software bugs | 2/2 = 1.00 | 1/3 ≈ 0.333333 | 1/2 = 0.50 |

- Software bugs (P=0.705)

- Insufficient battery recycling (P=0.440)

- Battery shortages (P=0.410)

- Insufficient charging infrastructure (P=0.420)

- Battery thermal risk (P=0.275)

- Software bugs score highest because the corrective action (software fixes, testing and OTA updates) produces the largest normalized improvement in Severity (ΔS) and is both low-cost and fast to implement in this illustrative scoring scheme.

- Battery shortages rank high because, although severity reduction (ΔS) is zero in the used post-action estimate (S stayed 9), the corrective action produces a large reduction in Occurrence (ΔO=3) and has moderate feasibility.

- The numerical values here are illustrative - the method is the deliverable: to apply this in practice, hold an AHP workshop with domain experts to (i) fill pairwise matrices and compute consistent weights, and (ii) produce authoritative Cost/Time feasibility scores.

4.4. Scenario Simulation and Comparative Validation

4.4.1. Simulation Parameters and Constraints

- Infrastructure Density: Market A possesses high density (>5 chargers/100km) versus Market B's low density (<1 charger/100km].

- Grid Robustness: Market A assumes a stable nuclear-renewable mix; Market B assumes a grid susceptible to load volatility under high EV penetration.

- Supply Chain Visibility: Market A utilizes Industry 4.0 digital tracking (Low Detection scores); Market B relies on traditional Tier-2 monitoring (Higher Detection scores).

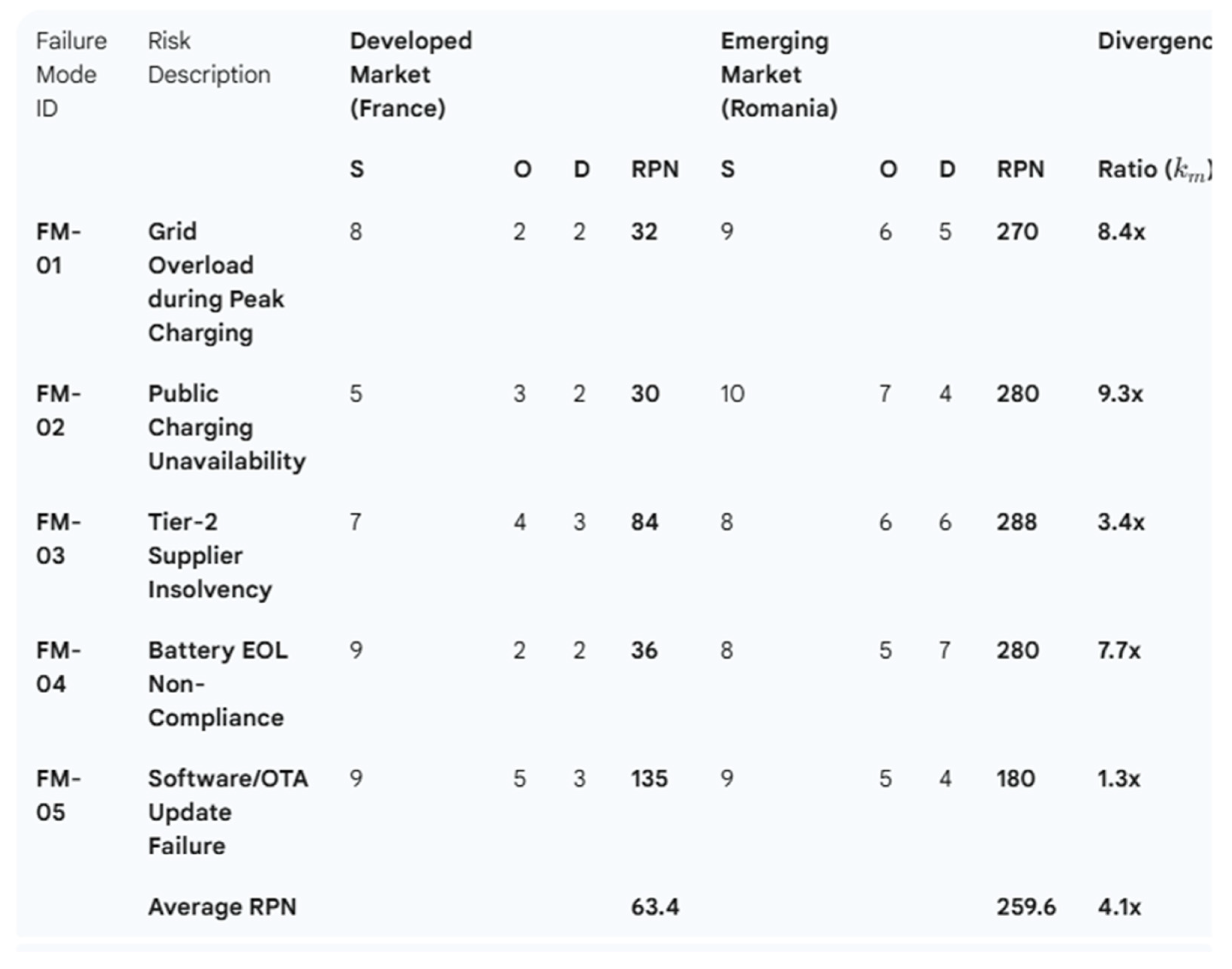

4.4.2. Comparative Risk Profile (RPN Divergence)

- The simulation reveals a profound asymmetry in risk profiles. While technological risks (FM-05) remain comparable across regions (RPN Ratio ≈1.3), systemic risks show extreme divergence.

- FM-01 (Grid Overload): In Market A, smart-grid technologies and stable baseload power result in a low RPN (32). In Market B, the combination of weaker infrastructure (High O) and lack of real-time monitoring (High D) spikes the RPN to 270.

- FM-02 (Charging Unavailability): The Severity score in Market B is critical (S=10) because a failure leaves the user stranded due to network sparsity. In Market A, redundancy (S=5) mitigates this impact.

4.4.3. Application of AHP Prioritization

- Using the AHP weights derived in Section 4.3 (w∆S = 0.40, w∆O = 0.30, wCost = 0.10), the model prioritizes corrective actions differently for each region.

- Developed Market Priority: The model prioritizes FM-05 (Software).

- Logic: Although the RPN is moderate, the effectiveness of mitigation (ΔS) is high, and the Detection improvement (ΔD) via Al is feasible. The strategy focuses on Product Reliability.

- Emerging Market Priority: The model prioritizes FM-01 (Grid) and FM-02 (Infra).

- Logic: The exorbitant RPNs demand immediate reduction in Occurrence (ΔO). The AHP output explicitly rejects high-cost software perfection in favor of Infrastructure Robustness and Basic Service Continuity.

4.4.4. The Market Maturity Coefficient (km)

5. Discussion

5.1. Interpretation of the Hybrid Mechanism

- Correction of Subjectivity: The simulation demonstrated that while "Tier-2 Supplier Insolvency" (FM-03) generated a high RPN in both markets, the AHP weighting—prioritizing Time-to-Implement and Cost—reordered the priority list differently for each region. This confirms that FMEA RPNs alone are insufficient for strategic resource allocation.

- Resolution of Conflicts: The framework successfully resolved the tension between "Engineering Severity" (technical failures) and "Strategic Feasibility" (cost/time). For instance, in the Emerging Market scenario, the model deprioritized high-tech software fixes (FM-05) in favor of foundational grid stability (FM-01), reflecting the harsh reality of resource scarcity [1,2].

5.2. The Structural Asymmetry of Risk (km)

- Global Technical Risks (km≈1.3): Risks associated with vehicle technology, such as software bugs (FM-05) or battery chemistry, show low divergence (≈1.3x). These are "universal" challenges inherent to the technology itself.

- Local Systemic Risks (km>8.0): Risks associated with the operating environment, such as Grid Overload (FM-01, km=8.4) and Charging Unavailability (FM-02, km=9.3), show extreme divergence.

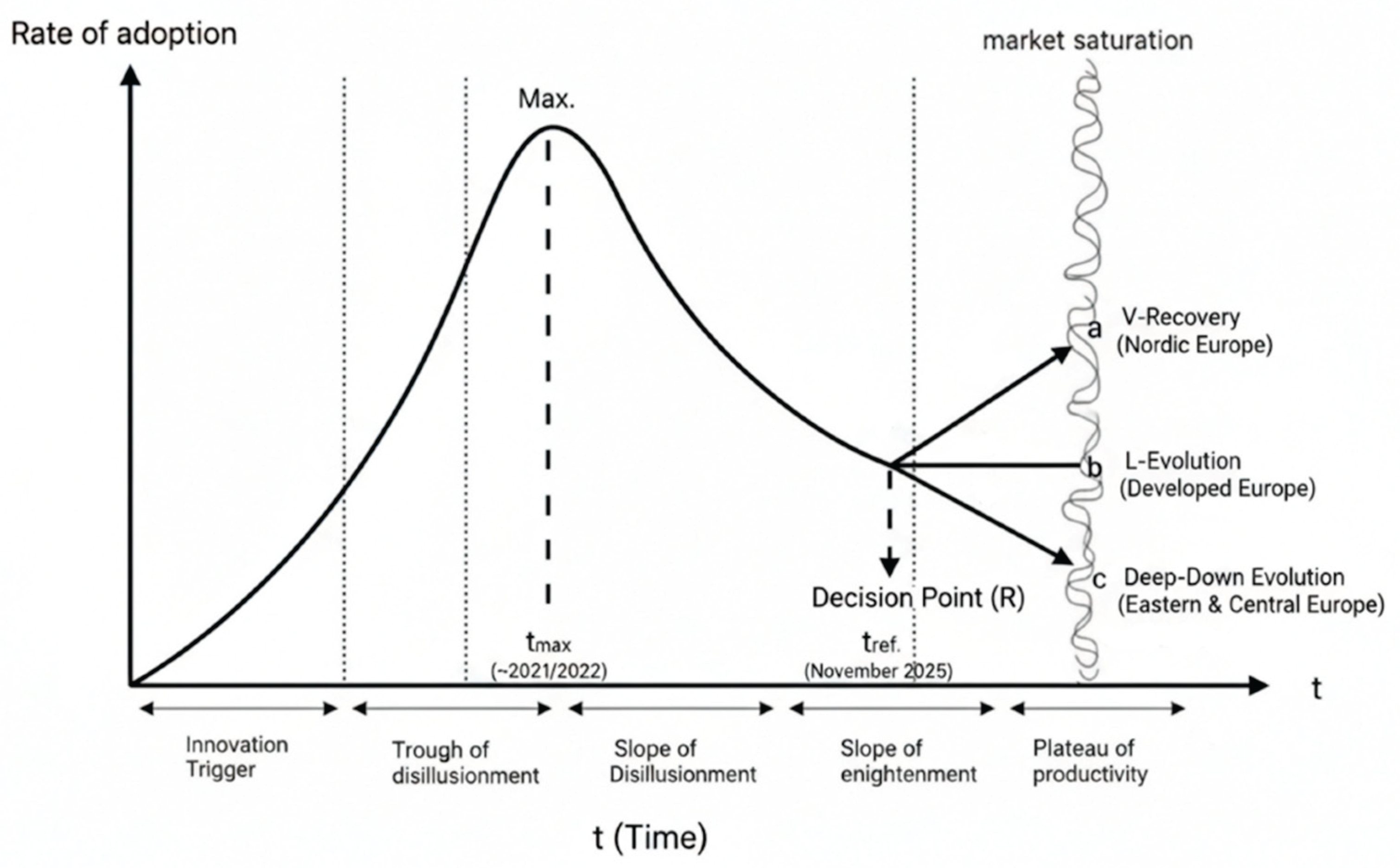

5.3. Transition Trajectories and the "Hype Cycle" Dynamics

- Trajectory (a): V-shaped Recovery (e.g., Nordic European countries). This path occurs when the net balance of forces is favorable to transformation. In this case, the ICE-EV transition is pursued rigorously, with the market offering significant growth rates despite possible contagion effects from the broader economy.

- Trajectory (b): L-shaped Evolution (e.g., Developed European markets such as Germany, France, Italy, UK). This represents a quasi-equilibrium. In these markets, customer focus has shifted towards long-distance performance expectations. However, adoption has been dampened by the reduction or cancellation of subsidies. In the context of a persistent price differential and higher insurance costs, the market maintains a good stability rather than accelerated growth.

- Trajectory (c): Deep-down Evolution (e.g., Eastern and Central European - ECE countries). This illustrates the most unfavorable dynamic. Recovery is hindered because opposing factors are dominant: criteria related to high initial price, lack of subsidies, and the poor quality of infrastructure have a significant negative impact on adoption.

- a: in this case, the ICE-EV transition was considered extremely seriously, the market offering significant growth rates despite possible contagion effects.

- b: in large European markets such as GB, Germany, Fr, Italy, customer focus has been on long-distance performance and customers have felt the reduction or cancellation of subsidies, in the context of a persistent relatively large price differential and more expensive insurance; a quasi-equilibrium is observed, which will probably be maintained.

- c: in ECE countries we are witnessing the most unfavorable dynamic, the criteria related to initial price, subsidies, and infrastructure quality having a significant impact.

5.4. The "Digital Divide" in Dynamic Risk Management

- In Developed Markets, Al transforms FMEA into a dynamic, "living" system where D approaches 1 (instant detection).

- In Emerging Markets, reliance on manual reporting keeps D scores high (3-5).

6. Conclusions

References

- International Electrotechnical Commission. IEC 60812:2018 – Failure Modes and Effects Analysis (FMEA and FMECA). IEC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018.

- AIAG; VDA. FMEA Handbook: Design, Process, and Machinery; Automotive Industry Action Group: Southfield, MI, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Haimes, Y.Y. Risk Modeling, Assessment, and Management, 4th ed.; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Sodhi, M.S.; Tang, C.S. Supply Chain Management for Extreme Conditions; SSRN, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Paksoy, T.; Deveci, M. Sustainable Vehicle Fleet Management with Electric Vehicles Using a Two-Stage Approach. Sustainability 2023, 15, 6087. [Google Scholar]

- Saaty, T.L. The Analytic Hierarchy Process: What It Is and How It Is Used; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Archsmith, K.; Kendall, P.; Rapson, D. From cradle to junkyard: Assessing the life cycle greenhouse gas benefits of electric vehicles. Research in Transportation Economics 2015, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archsmith, K. Attribute substitution in household vehicle portfolios. The RAND Journal of Economics 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahel, V.; Ndeye, P. Strategic resource dependence and adoption of a substitute under learning-by-doing. 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Bento, A.; Knittel, C.; Li, H.; Roth, K.; Zampolli, L. The effect of fuel economy standards on vehicle weight dispersion and accident fatalities. 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Chakravorty, U.; Krul, A.; Koundouri, P. Cycles in nonrenewable resource prices with pollution and learning-by-doing. Journal of Economic Dynamics and Control 2012, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creti, A.; Maïzi, N.; Ziv, K. Defining the abatement cost in presence of learning-by-doing: Application to the fuel cell electric vehicle. Environmental and Resource Economics 2018, 71. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, L.; Metcalf, G. Estimating the effect of a gasoline tax on carbon emissions. Journal of Applied Econometrics 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, L.; Knittel, C.; Li, H. Evidence of a homeowner-renter gap for electric vehicles. App Economic Letters 2019, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardman, S.; Shiu, F.; Gillingham, K. A review of consumer preferences of and interactions with electric vehicle charging infrastructure. In Transportation Research Part D: Transport and Environment; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Helveston, J.; Liu, Y.; Van Arman, J. Will Subsidies Drive Electric Vehicle Adoption? Measuring Consumer Preferences in the U.S. and China. Transportation Research 2015, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holland, S.; Mansur, E.; Yates, A. Are there environmental benefits from driving electric vehicles? The importance of local factors. Am Ec Review 2016, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holland, S.; Mansur, E.; Yates, A. Distributional effects of air pollution from electric vehicle adoption. Journal of the Association of Environmental and Resource Economics 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holland, S.; Mansur, E.; Yates, A. The electric vehicle transition and the economics of banning gasoline vehicles. American Economic Journal: Economic Policy 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobsen, M.; van Benthem, A. Fuel economy and safety: The influences of vehicle class and driver behavior. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 2013, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langer, O.; Archsmith, K. Designing dynamic subsidies to spur adoption of new technologies. 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Li, S.; Li, J.; Li, S. Compatibility and Investment in the U.S. electric vehicle market. 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Li, S.; Xing, R.; Li, S. The market for electric vehicles: indirect network effects and policy design. Journal of the Association of Environmental and Resource Economists 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muehleger, N.; Jansson, M. Subsidizing mass adoption of electric vehicles: Quasi-experimental evidence from California. 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Springel, A. Network externality and subsidy structure in two-sided markets: Evidence from electric vehicle incentives. 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Springel, A. Network Externality and Subsidy Structure in Two-Sided Markets: Evidence from Electric Vehicle Incentives. American Economic Journal 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuksel, T.; Green, M.; R. S. Effect of regional grid mix, driving patterns and climate on the comparative. 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, J.; Wang, S.; J. L. Impact of charging infrastructure on electric vehicle adoption: A spatiotemporal analysis. 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Boscoianu, M.; Toth, Z.; Goga, A.S. The Proliferation of Artificial Intelligence in the Forklift Industry—An Analysis for the Case of Romania. Sustainability 2024, 16, 9306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boscoianu, M.; Toth, Z.; Goga, A.S. Sustainable Strategies to Reduce Logistics Costs Based on Cross-Docking—The Case of Emerging European Markets. Sustainability 2025, 17, 6471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toth, Z.; Puiu, I.R.; Wang, S.S.; Vraˇjitoru, E.S.; Boscoianu, M. Dynamic capabilities and high-quality standards in S.C. Jungheinrich Romania, S.R.L. In Proceedings of the Review of Management and Economic Engineering 8th International Management Conference: “Management Challenges and Opportunities in a Post-Pandemic Reality”, Cluj-Napoca, Romania, 22–24 September 2022; pp. 44–49. [Google Scholar]

- Goga, A.S.; Boscoianu, M. Sustainability and the risks of introducing AI. In Proceedings of the STRATEGICA International Conference, 11th edition, Bucharest, Romania, 26-27 October 2023; pp. 231–243. [Google Scholar]

- Bruckner, R.; Heekeren, H.; Nassar, M. Understanding learning through uncertainty and bias. In Communication Psychology; 2025. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).