1. Introduction

Accurate and detailed knowledge of Land Use and Land Cover (LULC) is one of the most significant areas of interest in spatial planning and landscape science. It inherently involves diverse research fields, from the strictly ecological to the technological [

1,

2], and holds central importance in a wide range of studies and applications. These include urban planning, natural and environmental resource monitoring, land-use policy development, and even in understanding global climate evolution [

3].

LULC classifiers can be distinguished as either supervised or unsupervised [

4] and as parametric or non-parametric [

5,

6].

The first distinction is based on whether a dataset is required to train the classification algorithm. In practice, supervised algorithms are provided with input data alongside the correct corresponding outputs—for instance, ‘this pixel with these characteristics is grassland.’ The algorithm thus learns the relationship between input and output and replicates this procedure across the entire dataset to be analysed. In contrast, unsupervised algorithms do not require a preliminary dataset for training; instead, they autonomously identify patterns, similarities, and clusters within the dataset under analysis [

7] (Lu & Weng, 2007).

Algorithms can further be distinguished as parametric or non-parametric. The key discriminator here is the requirement for a strong preliminary assumption about the statistical distribution of the data [

5], typically assumed to be Gaussian for parametric methods. For non-parametric algorithms, these initial assumptions are unnecessary, making them considerably more adaptable in situations where in-depth prior knowledge of the analysis area is lacking [

8].

These two broad categories are not mutually exclusive but rather intersect, providing a deeper interpretative framework for the tools. In this sense, we can identify algorithms that are: Supervised Parametric, Supervised Non-Parametric, Unsupervised Parametric, and Unsupervised Non-Parametric (see

Table 1).

As can be observed from

Table 1, there is currently access to a significant and heterogeneous range of algorithms. However, there is still no single ideal or universally superior algorithm in terms of robustness and result accuracy [

9]. In other words, there is no perfect algorithm, only the one most suited to a specific problem, dataset, user skill level, and final objective, in line with the “No Free Lunch Theorem” formulated by Wolpert in 1995 [

10,

11].

This principle implies that an algorithm’s superiority only emerges in specific contexts, as its performance results from a trade-off between bias, variance, and computational complexity [

12]. Consequently, the relative performance of algorithms is strictly dependent on the nature of the dataset, the size of the training set, and the specific characteristics of the thematic classes to be distinguished [

13].

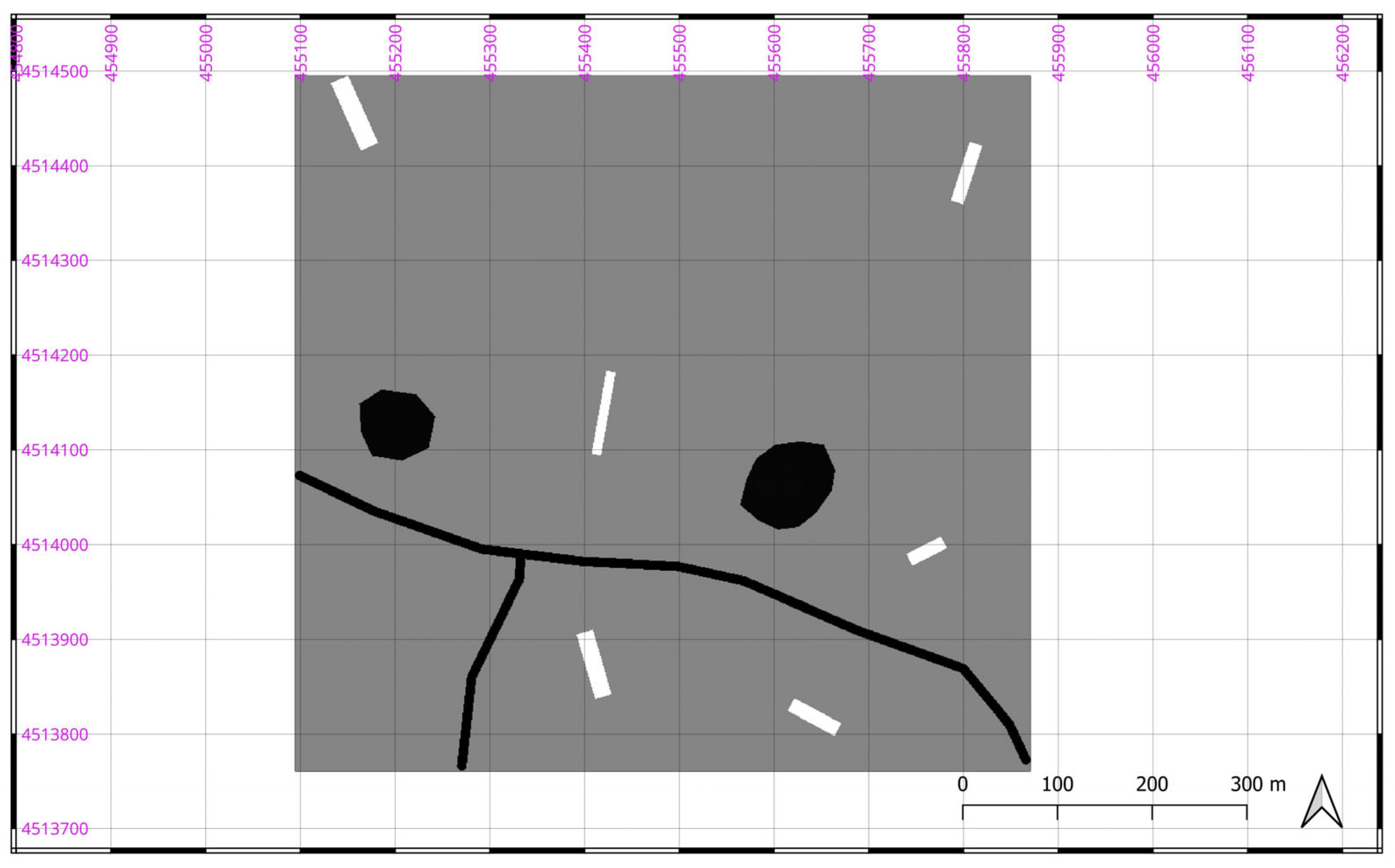

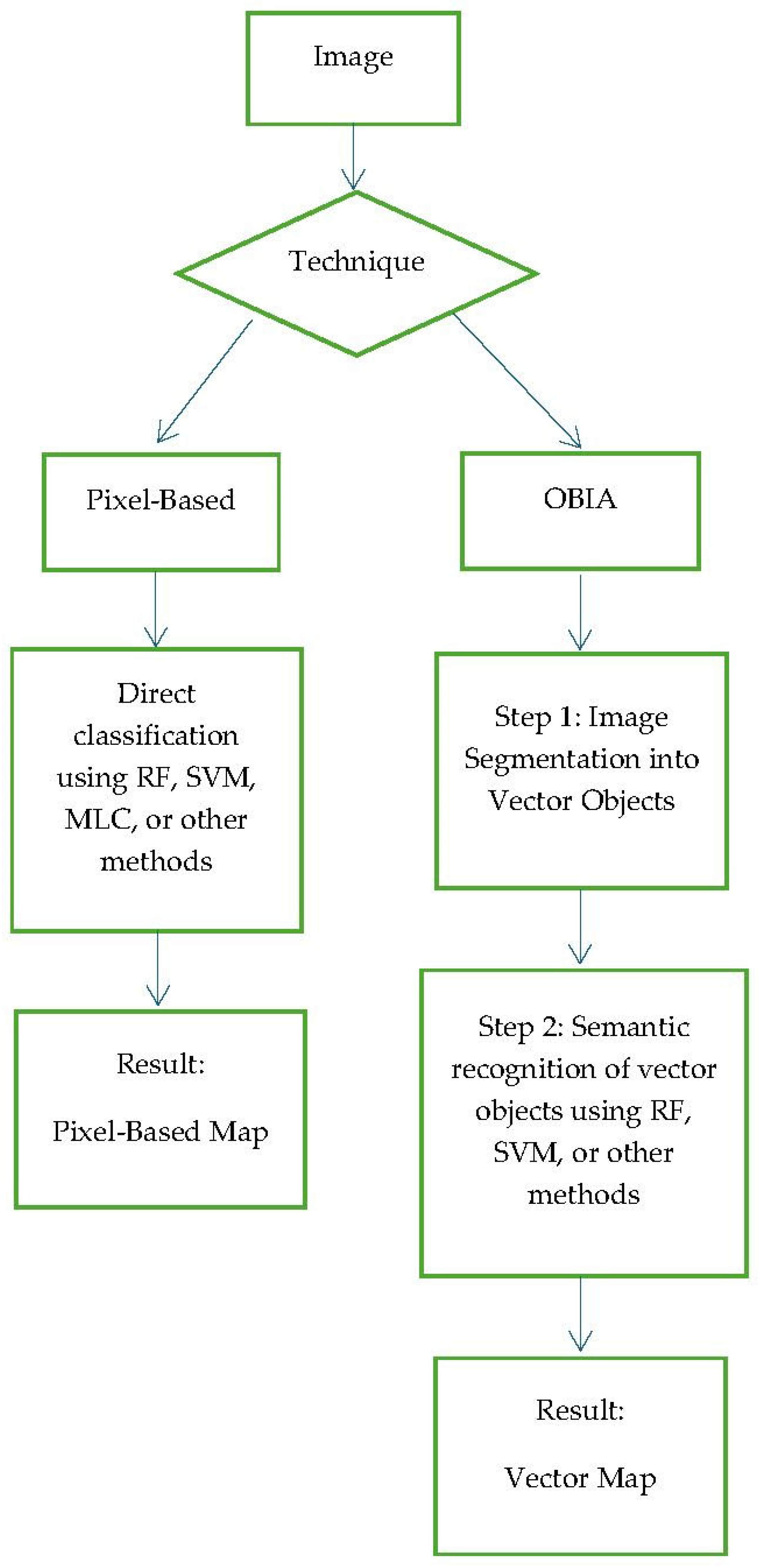

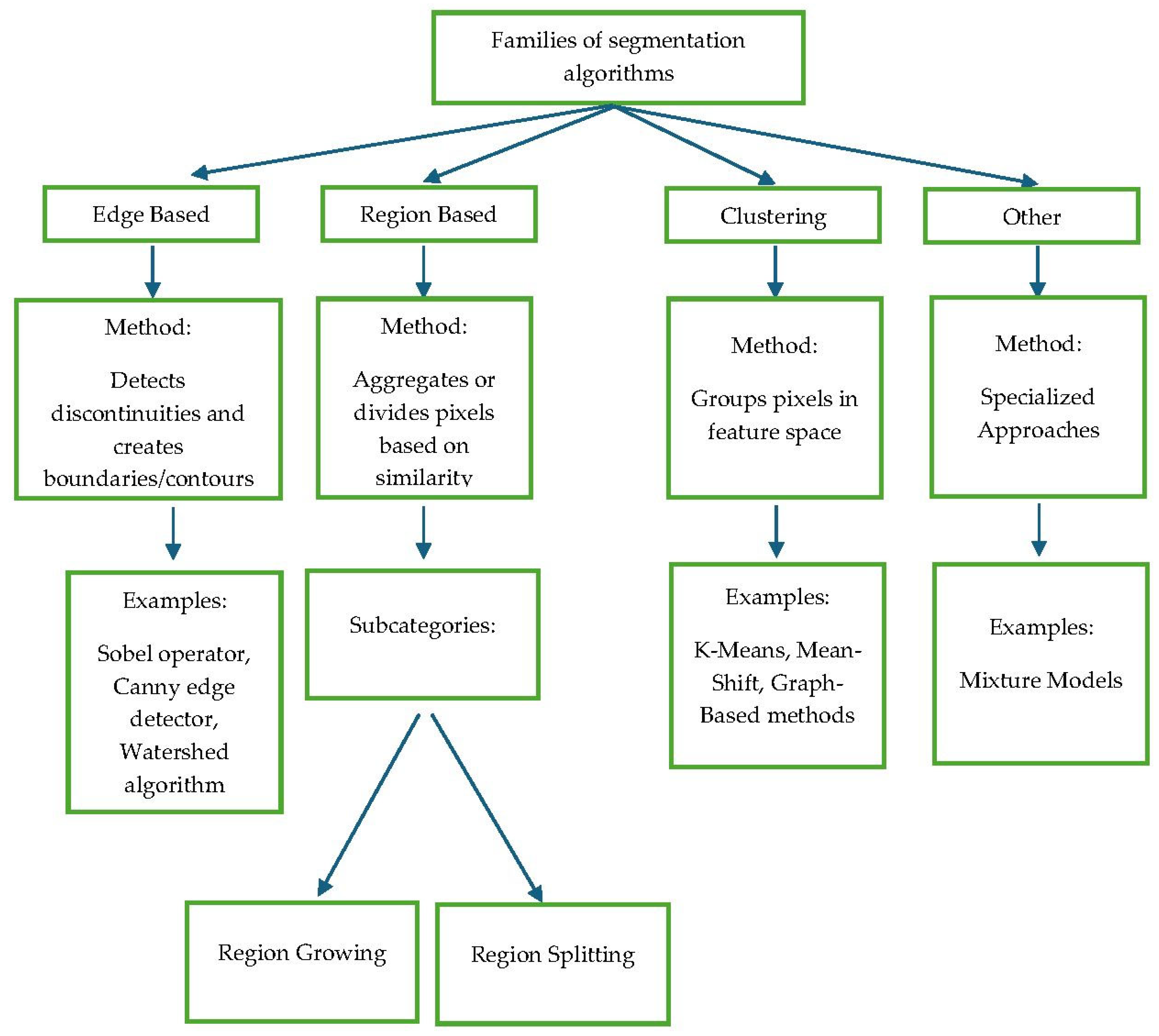

Furthermore, LULC recognition algorithms can be used individually, following the well-established pixel-based technological approach, or they can be associated with, and applied consecutively to, more specific image segmentation methods (

Figure 1) within the more recent theoretical and technological paradigm of Object-Based Image Analysis (OBIA) [

14].

More specifically, the former classifies each pixel based on its spectral signature, which in many cases generates classifications affected by noise, producing a ‘salt-and-pepper’ effect [

15]. Conversely, in the second possibility—the OBIA approach—the image is first segmented into homogeneous regions (objects) that correspond to real-world entities, distinguishing them from what could be termed the “background.” Subsequently, a semantic classification is performed based not only on the spectral characteristics of these objects, but also on their shape, texture, and context [

16].

Although algorithms can be effectively employed in both approaches, comparative studies have shown that OBIA surpasses pixel-based methods in accuracy, particularly when using high-resolution imagery and classifying complex categories, such as those in urban environments [

17]. However, in this case as well, the choice between the two approaches is not a matter of “right or wrong,” or “better or worse,” but of fitness for purpose. The pixel-based approach is simpler, more direct, and often sufficient for medium-to-low-resolution data where the goal is a general estimate of land cover; whereas an OBIA approach is preferable when working with very high-resolution imagery, such as that acquired by drones [

18], and/or in situations where the classes to be distinguished have similar spectral signatures but different shapes or textures. Examples include distinguishing a roof from a road [

19] or differentiating between tree species, where, in some cases, texture features are more important than purely spectral ones [

20].

Following the OBIA procedure flow (

Figure 1), it becomes clear that the choice of segmentation algorithm is crucial for the final quality of the objects. It is upon these objects that, in the subsequent phase, semantic classification will be applied using the algorithms previously described.

A detailed examination of various segmentation algorithms and their applications is provided in the edited volume by Blaschke et al. (2008) [

16], which compiles several pioneering works in the field. It delves into the theoretical foundations of segmentation and the concept of scale within the principal and most widely used algorithms. A thorough exploration and classification of these would warrant a dedicated discussion. However, a sufficiently general synthesis can be attempted, starting from the seminal and foundational research by Haralick & Shapiro (1985) [

21], which categorises these algorithms into logical families based on their operating principles (

Figure 2).

The first family comprises algorithms that operate on the direct detection of edges (Edge Detection), identifying them where a significant gradient in brightness/colour is measured. For instance, Jin & Davis (2005) [

22] utilised techniques from this family to identify building outlines using high-resolution imagery, demonstrating the utility of these algorithms within an OBIA workflow for land analysis.

The second family (Region Growing) includes algorithms that function in a diametrically opposite manner to the former. Instead of seeking edges, they directly seek homogeneous areas. More specifically, they start from a ‘seed pixel’ and iteratively aggregate adjacent pixels that meet a similarity criterion, for example, a spectral difference below a certain threshold. A valid and widespread example of this family is the Multiresolution Segmentation developed by Baatz & Schäpe (2000) [

23], which simultaneously considers spectral and shape similarity.

A third family incorporates clustering techniques that group pixels based on statistical parameters. For example, the K-Means algorithm [

24,

25], despite its simplicity, remains a benchmark for this technique, although it requires the a priori definition of the number of clusters (K). A more robust and non-parametric evolution is represented by the Mean-Shift algorithm [

26], which automatically determines the number of clusters by seeking the modes in the dataset’s density distribution.

The last category encompasses more modern and specialised algorithms. These develop techniques to model the physical properties of the scene, such as illumination or reflectance, to separate objects. Others are based on Graph-Based approaches, which represent the image as a graph where nodes are pixels and edges connect neighbours; similarity between pixels is assigned to the edge as a weight attribute, and segmentation occurs by removing edges with minimal weight, thereby partitioning the graph [

27,

28].

Also, within this last family, one finds techniques based on Mixture Models, which assume the data is generated from a mixture of statistical distributions, where each mixture component represents an image region with distinct statistical properties [

29].

Of course, from 1985 to the present day, theoretical and technological progression has made significant advances, and the kaleidoscope of algorithms has grown considerably. For example, Pal & Ghosh (1992) [

30] explicitly acknowledge the role of fuzzy set theory in segmentation; subsequently, Cheng et al. (2001) [

31] focus on colour image segmentation, incorporating specific methods, such as those based on colour physics, separating reflectance components from illumination to achieve segmentation more robust to changes in light, shadows, and reflections.

Furthermore, the advent of Deep Learning has revolutionised the playing field, developing methods capable of learning hierarchical features according to neural network architectures (e.g., FCN, U-Net), marking a significant leap forward in performance (Garcia et al., 2017) [

32]. For conceptual accuracy, Deep Learning technology, like Fuzzy logic or Graph Theory itself, could be considered as transversal tools, potentially applicable to all classical segmentation families, rather than as criteria for generating new families. For instance, one could operate with a Region-Based approach, automated via a convolutional neural network that incorporates Fuzzy logic.

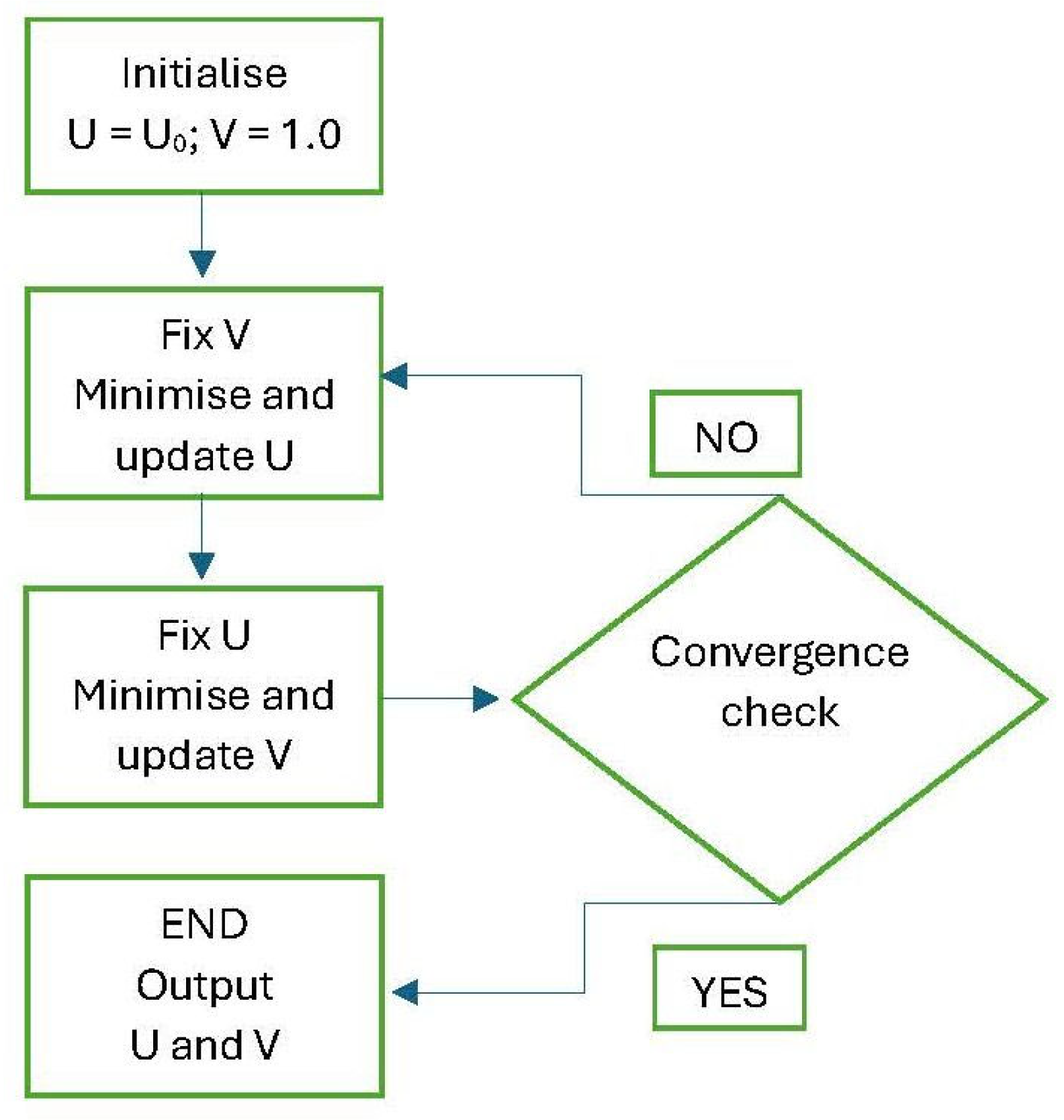

An additional class of tools can be identified in variational methods or energy-based models. This class distinguishes itself from the previous ones through its more strictly mathematical and geometric approach to the segmentation problem. Its seminal representative can be found in the Mumford-Shah functional [

33]. Through energy optimisation, it allows the image to be segmented into homogeneous regions by differentiating its pixels into those belonging to a “smooth” zone, such as the interior of a sought-after object or the image background, and those identifying the separation, or more precisely, the boundary between objects and background.

The technique of image segmentation via this procedure occurs by minimising the energy value produced by the pixels of an image. However, minimising the Mumford-Shah functional directly is highly complex because the set of object boundaries can have wide variability. Minimising the functional means finding the best segmentation of an image that balances three objectives [

34]:

a) having smooth regions, inside of which there are no large variations in the image; thus, low variance between pixel values.

b) having boundaries that are as short and regular as possible.

c) the processed image, where pixels are classified as boundary or background, must resemble the original image as closely as possible.

In more formal terms, for an original two-dimensional image

, one seeks an image

that simplifies

and a set of boundaries

, which minimise the overall energy

as in the following (equation 1):

The first part of the equation, known as the regularity term, “penalises” variation within the smooth regions. In other words, the simplified image should be as uniform as possible inside each region, such as the interior of an object or the background itself.

The second term controls the fidelity, or more precisely, the similarity between the original image and its simplified copy , through the tuning parameter . Assuming a high value for this parameter forces the objects in the copy to be characterised by a high level of detail. However, this inevitably leads to an increase in the length of the segmentation boundary and, consequently, in the overall energy value .

Finally, the last part of the functional penalises overly long and complex boundaries through the parameter

. Increasing this parameter produces solutions with shorter and simpler contours [

35], but conversely, there is a risk of losing useful details that are not merely “noise.”

The original formulation of the problem by Mumford and Shah stipulates that

must be a finite union of closed, regular (more precisely, analytic) curves. However, as is customary in modern Mathematical Analysis, it is preferable to work with a version where such regularity is not directly required. One can then attempt to prove that the minimising sets

are, in fact, more regular, using their minimality to demonstrate this. For generic sets

, the concept of length can be generalised using one-dimensional Hausdorff measure. With this nuance, for each fixed

, the functional

can be minimised with respect to the variable

in a classical manner, using appropriate Sobolev spaces, to obtain minimisers

. The subsequent minimisation—that is, minimising

with respect to

—is more complex and requires considering the Hausdorff convergence of sets

and the minimality properties of the solution [

36]. Solving minimisation problems involving the Mumford-Shah functional in the presented form is therefore extremely complex, as it involves two variables, the function

and the set

, of very different natures.

A completely different viewpoint is due to De Giorgi, who interprets the variable

as the sole variable of the problem, with the set

replaced by the set

of essential discontinuity points of

. To implement this approach, appropriate spaces of Special functions of Bounded Variation (from which the acronym SBV is derived) were introduced and studied. Using these, the functional can be defined as follows (equation 2):

This represents the

weak form of the Mumford-Shah functional, where

is replaced by

and a suitable meaning is given to the “approximate gradient,” allowing for the resolution of the related minimisation problems. Furthermore, regularity theorems then ensure that

can be considered as a union of curves [

37,

38,

39]. Despite this conceptual effort, the implementation of a direct numerical minimisation of the Mumford-Shah functional—even via the De Giorgi method—still presents significant difficulties. These stem from its dependence on the unknown one-dimensional set

, whether considered as an arbitrary closed set or as a finite union of closed curves.

However, the formulation in terms of SBV functions allows the functional

to be framed within a variational setting. In this setting, one can construct approximations capable of guaranteeing the convergence of the minimisation problems, understood as the convergence of both the minimal values and the minimising functions. A sequence of functionals possessing this property is said to

Gamma-converge to

[

40]. This approach offers greater flexibility, which translates into the possibility of developing approximations in spaces different from that of the Gamma-limit—in our case, the Mumford-Shah functional in its weak form [

41].

In this research, an approximation technique for the Mumford-Shah functional and a dynamic approach directly aimed at the recognizing contours will be implemented to test their potential and limitations in recognising objects within raster images. These two solutions, which can be succinctly referred to as Ambrosio-Tortorelli and Snakes, will be explained in detail in the following section.

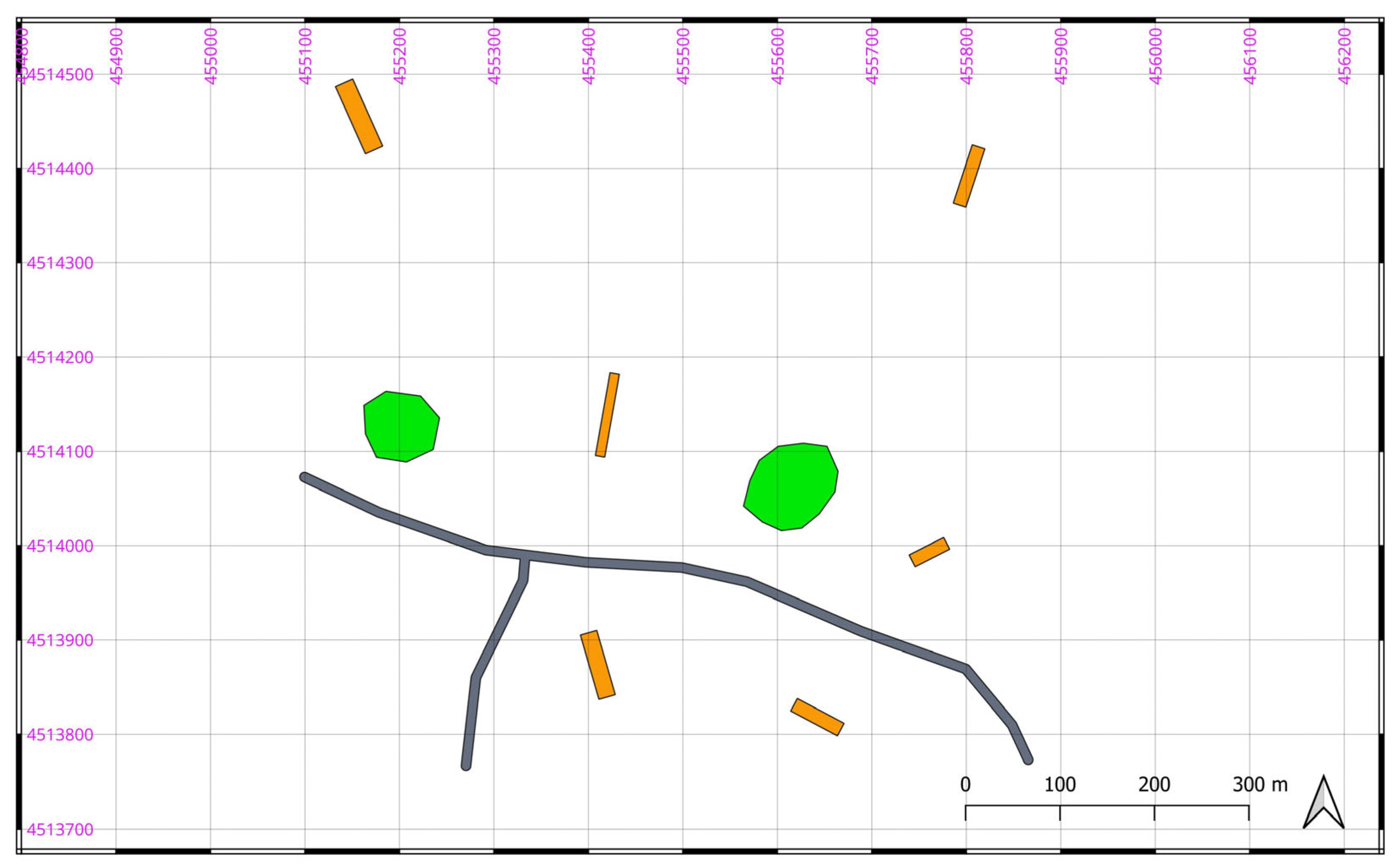

3. Material, Experiment and Results

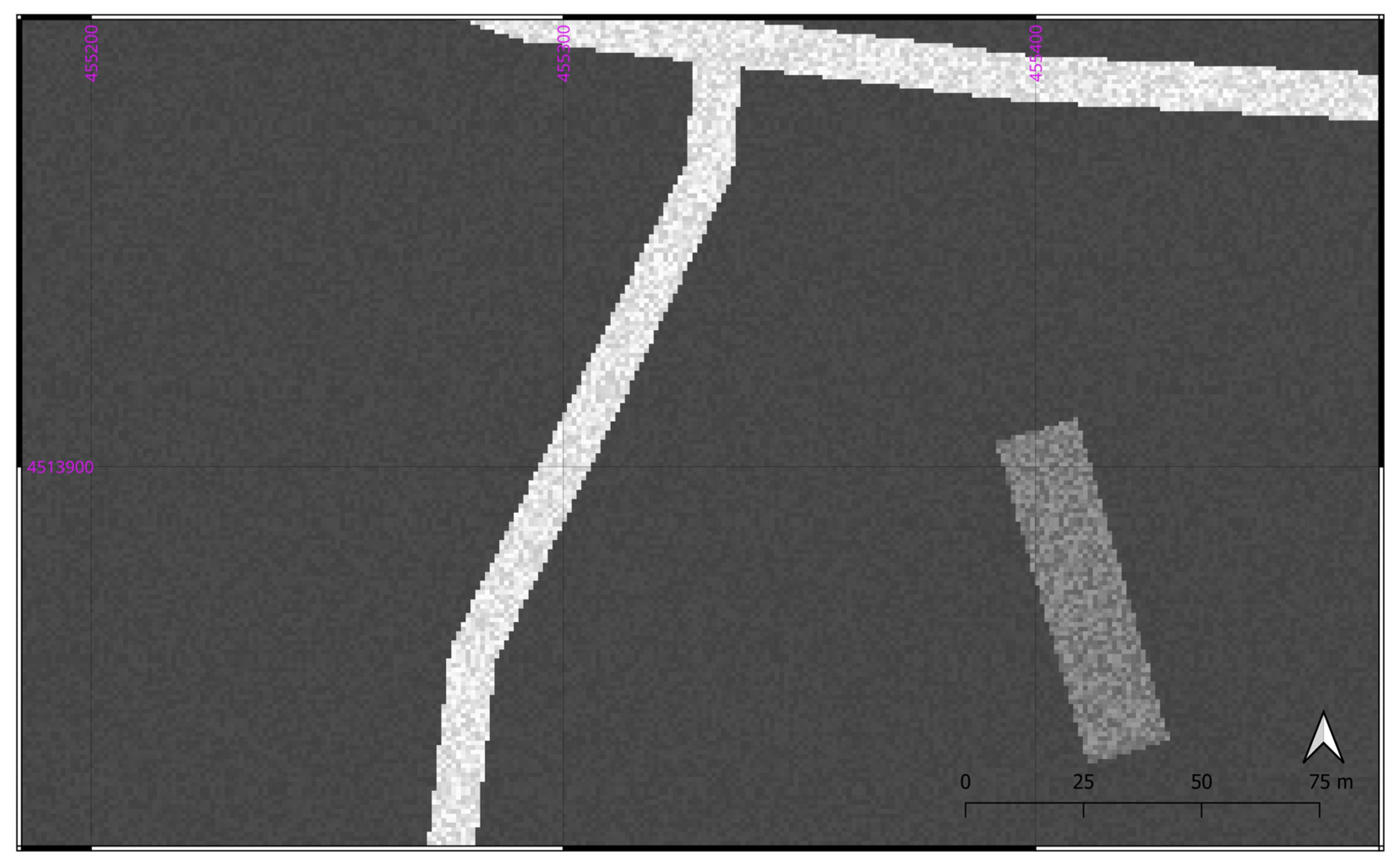

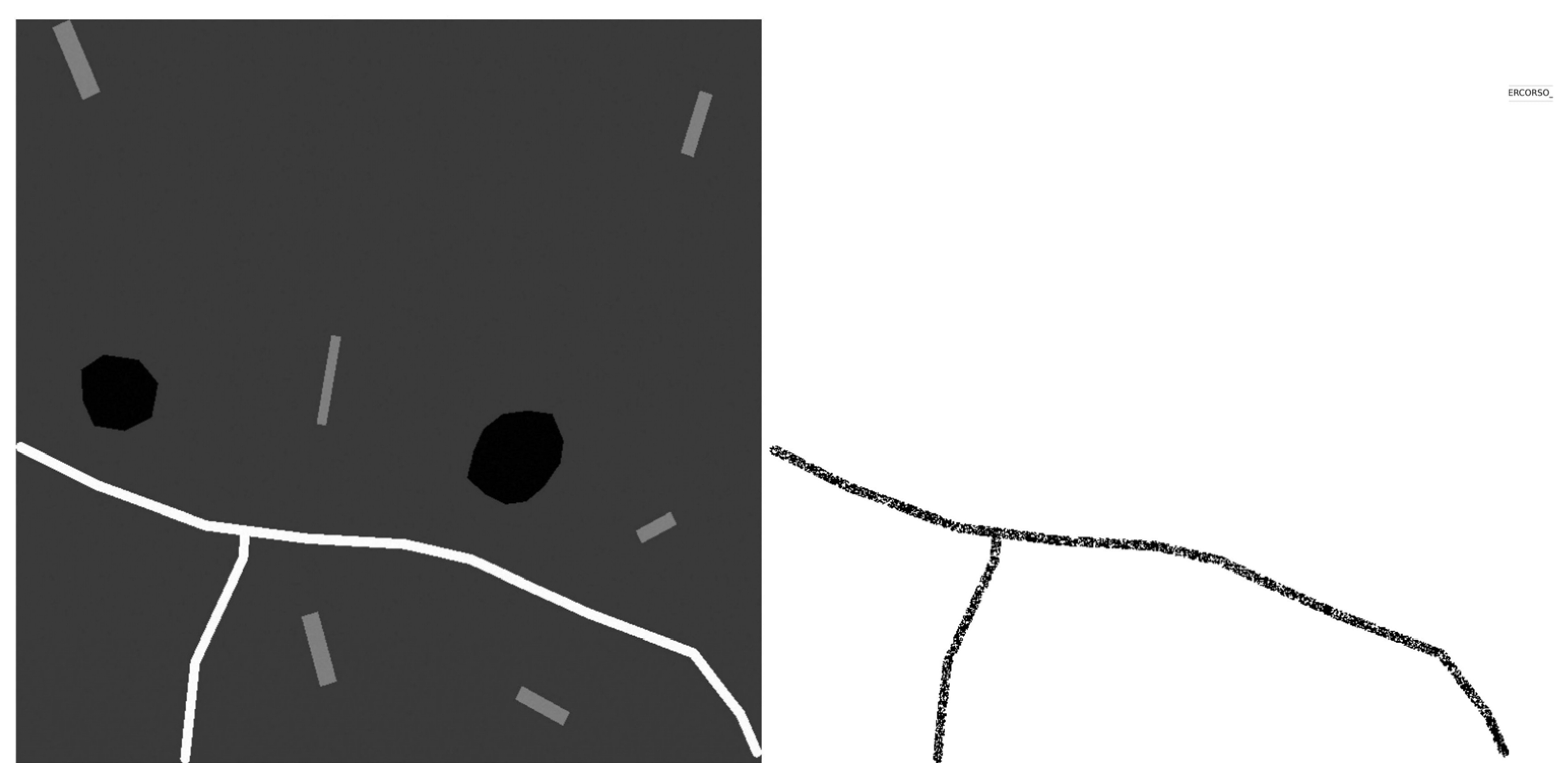

To evaluate the performance of the two procedures and the algorithmic efficiency achieved through their implementation in the Python™ programming language, it was decided to test the Ambrosio–Tortorelli model and the Snake on a library of images specifically generated for this purpose. These images were created within the QGIS environment (

https://qgis.org/) starting from vectorised elementary shapes, typically representative of common geographic features such as roads, buildings, trees, or small bodies of water (

Figure 4). Using this type of imagery, albeit very simple, offers the advantage of having full control over the results obtained from the Ambrosio–Tortorelli model and the Snake. Indeed, by assuming these base images to be the “ground truth,” the precise location and semantic classification of each pixel are known with absolute certainty, as they were generated according to predetermined specifications.

These original images can therefore be reliably used as reference bases against which to assess the algorithms’ ability to determine the shape, size, and position of the objects contained within the images.

Subsequently, the original image was converted into a raster-type matrix, with a pixel resolution of 1m × 1m, resulting in a total of 760 × 760 pixels. Thus, the image matrix comprises 577,600 elements in total. Each pixel was then assigned an energy value through a greyscale (0–255), determined by its spatial position—specifically, whether the pixel was located inside one of the circulars, rectangular, or polygonal shapes, or outside of them. For this first experimental step, it was hypothesised that the circular shapes could represent trees, the rectangles buildings, the polygon a road, and all pixels not included within these geometries were classified as background. Ten test scenarios were then generated by assigning a specific greyscale energy value to each object class. This value differed between pixels belonging to different object classes but was uniform for pixels within the same class. Furthermore, the energy value assigned to each class was scaled to achieve an overall variance of the entire image matrix that increased progressively from Scenario 1 to Scenario 10, as detailed in the subsequent

Table 5. Having obtained the initial results, which will be examined and discussed in detail later, it was decided to increase the complexity within the original image to understand the current limitations of the algorithmic solutions. For this reason, a further 9 scenarios were generated. In these, variance in the energy value was also introduced within objects belonging to the same geometric class. This was achieved using a “random” function with predetermined bounds, as outlined in the subsequent

Table 6.

Table 5.

The ten scenarios featuring constant energy within each class and differing energy between classes.

Table 5.

The ten scenarios featuring constant energy within each class and differing energy between classes.

| Scenario |

Trees |

Buildings |

Roads |

Background |

Global Variance |

| S1 |

67 |

77 |

65 |

73 |

12 |

| S2 |

62 |

82 |

60 |

73 |

25 |

| S3 |

57 |

87 |

55 |

73 |

45 |

| S4 |

52 |

92 |

50 |

73 |

85 |

| S5 |

47 |

97 |

45 |

73 |

165 |

| S6 |

42 |

102 |

40 |

73 |

330 |

| S7 |

37 |

107 |

35 |

73 |

660 |

| S8 |

32 |

112 |

30 |

73 |

1230 |

| S9 |

27 |

117 |

25 |

73 |

2640 |

| S10 |

22 |

122 |

20 |

73 |

5280 |

Figure 5.

The overall raster image matrix (760px × 760px) with energy values assigned to the pixels according to scenario S10. Processed by the Authors.

Figure 5.

The overall raster image matrix (760px × 760px) with energy values assigned to the pixels according to scenario S10. Processed by the Authors.

Following the acquisition of results from both the Ambrosio-Tortorelli model and the Snake algorithm for these scenarios as well, the evaluation of object recognition and segmentation performance across the different described scenarios was undertaken. This assessment employed several statistical metrics, including Cohen’s Kappa [

43] and the Jaccard Index [

44].

Table 6.

The nine scenarios with noise were introduced both within and between classes.

Table 6.

The nine scenarios with noise were introduced both within and between classes.

| Scenario |

Trees

(range)

|

Buildings

(range)

|

Roads

(range)

|

Background

(range)

|

Global Variance |

| S1_R |

28-32 |

118-122 |

208-212 |

69-71 |

450-500 |

| S2_R |

25-35 |

115-125 |

205-215 |

68-72 |

550-650 |

| S3_R |

20-40 |

110-130 |

200-220 |

66-74 |

800-1000 |

| S4_R |

15-45 |

100-140 |

190-230 |

63-77 |

1500-2000 |

| S5_R |

8-50 |

90-150 |

180-240 |

60-80 |

2500-3500 |

| S6_R |

18-42 |

105-135 |

195-215 |

69-71 |

700-900 |

| S7_R |

22-38 |

112-128 |

205-215 |

68-72 |

600-750 |

| S8_R |

24-36 |

116-124 |

202-218 |

67-73 |

500-600 |

| S9_R |

26-34 |

116-124 |

206-214 |

68-72 |

480-520 |

Figure 6.

Detail of the raster image matrix developed according to the parameters of scenario S9_R. It can be observed how the value assigned to the pixels tends to vary within the geometric shapes. Processing by the Authors.

Figure 6.

Detail of the raster image matrix developed according to the parameters of scenario S9_R. It can be observed how the value assigned to the pixels tends to vary within the geometric shapes. Processing by the Authors.

The former estimates the measure of agreement between two raters and is formally expressed as (equation 17):

where ωₒ denotes the observed agreement—that is, the agreement observed between the two raters, calculated as the ratio of all concordant judgments to the total number of judgments. The term ωₑ expresses the value of the expected agreement, i.e., the agreement that would be expected if the two raters were statistically independent, maintained the same observed marginal distributions, and responded randomly. This approach is considered robust because it provides the percentage of agreement corrected for the component of chance agreement. In other words, it answers the question: “What percentage of the observed agreement is NOT explainable by mere chance?”

The second statistical metric, the Jaccard Index, measures the similarity between two sets based on the positions of the “1”s in the two matrices. This second evaluator is particularly useful when the “1” values are relatively rare, are considered more important for the analysis, and one wishes to estimate the overlap of the “1” areas. Formally, the Jaccard Index can be expressed as (equation 18):

In this context, A∩B corresponds to the number of positions where both matrices have the value “1”, while A∪B represents the number of positions where at least one of the two matrices records a “1”. Within the framework of this research, the role of the two “raters” is played, on one side, by the original image matrix and, on the other, by the matrices produced by the Ambrosio-Tortorelli and Snake algorithms. To conduct this final comparative analysis, it was necessary to convert all image matrices into binary matrices. In these, value 0 was assigned to background pixels and the value 1 to all pixels belonging to an object, regardless of their class. This transformation is an essential prerequisite for making the results comparable. While this conversion was straightforward for the original matrices, it presented greater complexity for the results obtained from the Ambrosio-Tortorelli model. This algorithm identifies pixels of strong discontinuity but does not directly provide a continuous, closed boundary delineating an object. Furthermore, an additional ambiguity arises it is necessary to specify to the system whether the object of interest is the area enclosed by the boundary pixels or the area outside them—to use a metaphor, whether one is seeking the doughnut or the doughnut hole. To overcome these two issues, two additional Python™ scripts were developed. The first task is to connect the boundary pixels into a continuous and closed path, even when discontinuities exist between them. In practice, when a pixel with a value of 1 is not adjacent to another, the script searches for the nearest subsequent pixel, allowing for a maximum tolerable discontinuity of 5 pixels. The second script, conversely, identifies and assigns value 1 to all pixels located inside these closed paths. To determine whether a pixel is inside a contour, a horizontal line is traced from that pixel in one direction (right or left, it does not matter). If this line intersects an odd number of boundaries before reaching the edge of the matrix, the pixel is classified as inside an object; if the number of intersections is even, the pixel is considered part of the background.

The tests conducted on the first image library—specifically, the scenarios without energy variance

within objects—seem to indicate that both procedures deliver highly satisfactory results. The Snake algorithm performed well in 9 out of 10 cases, and the Ambrosio-Tortorelli model in 10 out of 10, albeit with some reservations regarding scenario S1 (

Table 7 and

Table 8). It appears that when the energy gradient between objects, and between objects and the background, falls below a certain threshold, the algorithms exhibit greater uncertainty in the object recognition process. The subsequent image shows the analytical graphical result of the Ambrosio-Tortorelli model applied to S1 (

Figure 7). It can be observed that it fails to recognise the rectangular objects, yet it still yields a more effective outcome than the Snake algorithm, which in this case does not recognise a single object.

The situation changes dramatically when energy variance is introduced within objects, yet again with significant differences between the two algorithms. Except for scenario S5_R, where the intra-object variance reaches its maximum value, the Ambrosio-Tortorelli model demonstrates consistent performance across all scenarios. Naturally, the values for both Cohen’s Kappa and the Jaccard Index are significantly lower than in the previous, simpler scenarios. The Snake algorithm, however, appears to be more sensitive to the variance parameter (

Table 9 and

Table 10). It must also be noted that while the Ambrosio-Tortorelli model, despite evident difficulties, recognises and segments some objects largely in their original entirety, the Snake algorithm seems only to identify certain fragments. The subsequent analyses of the analytical graphical results illustrate these differences more effectively.

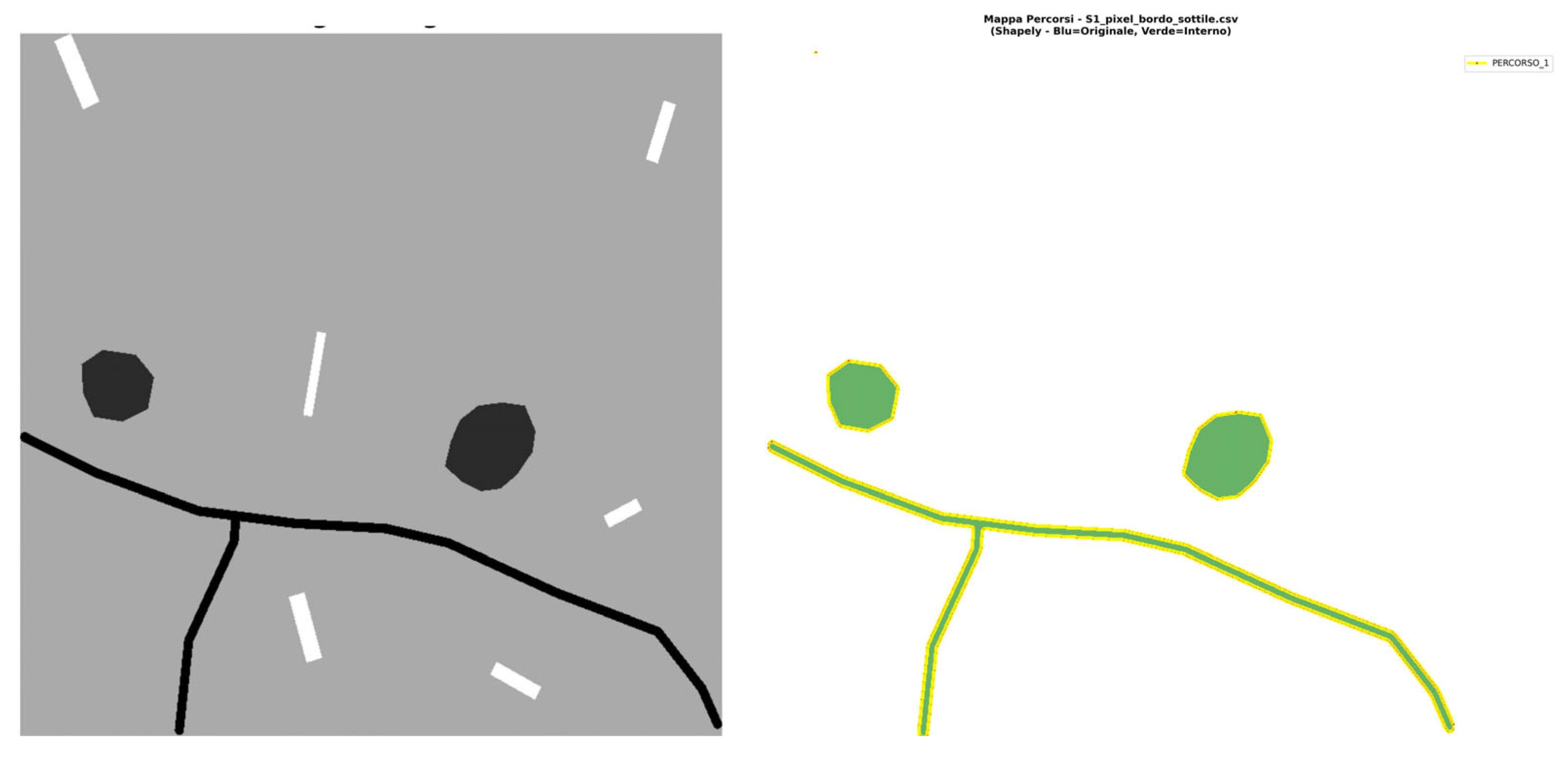

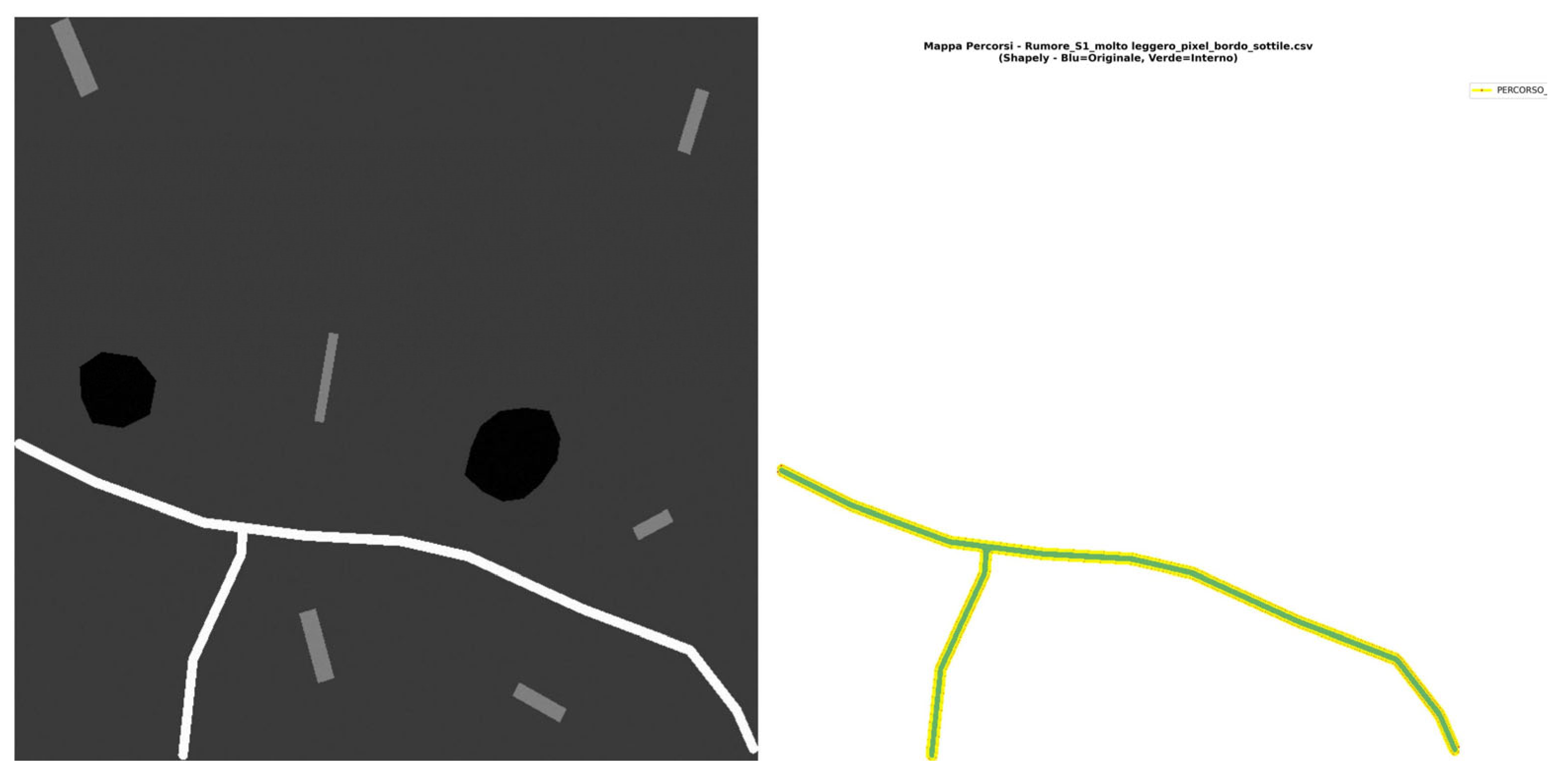

The subsequent

Figure 8 shows the results of the Ambrosio-Tortorelli model for scenario S1_R: it recognizes the road but loses all other features. Nevertheless, by the end of the process, the road is successfully identified as a single, coherent object. Subsequently,

Figure 9 shows the analytical graphical result of the Snake algorithm applied to the same scenario. As also indicated by the two statistical conformity estimators, there are no significant differences.

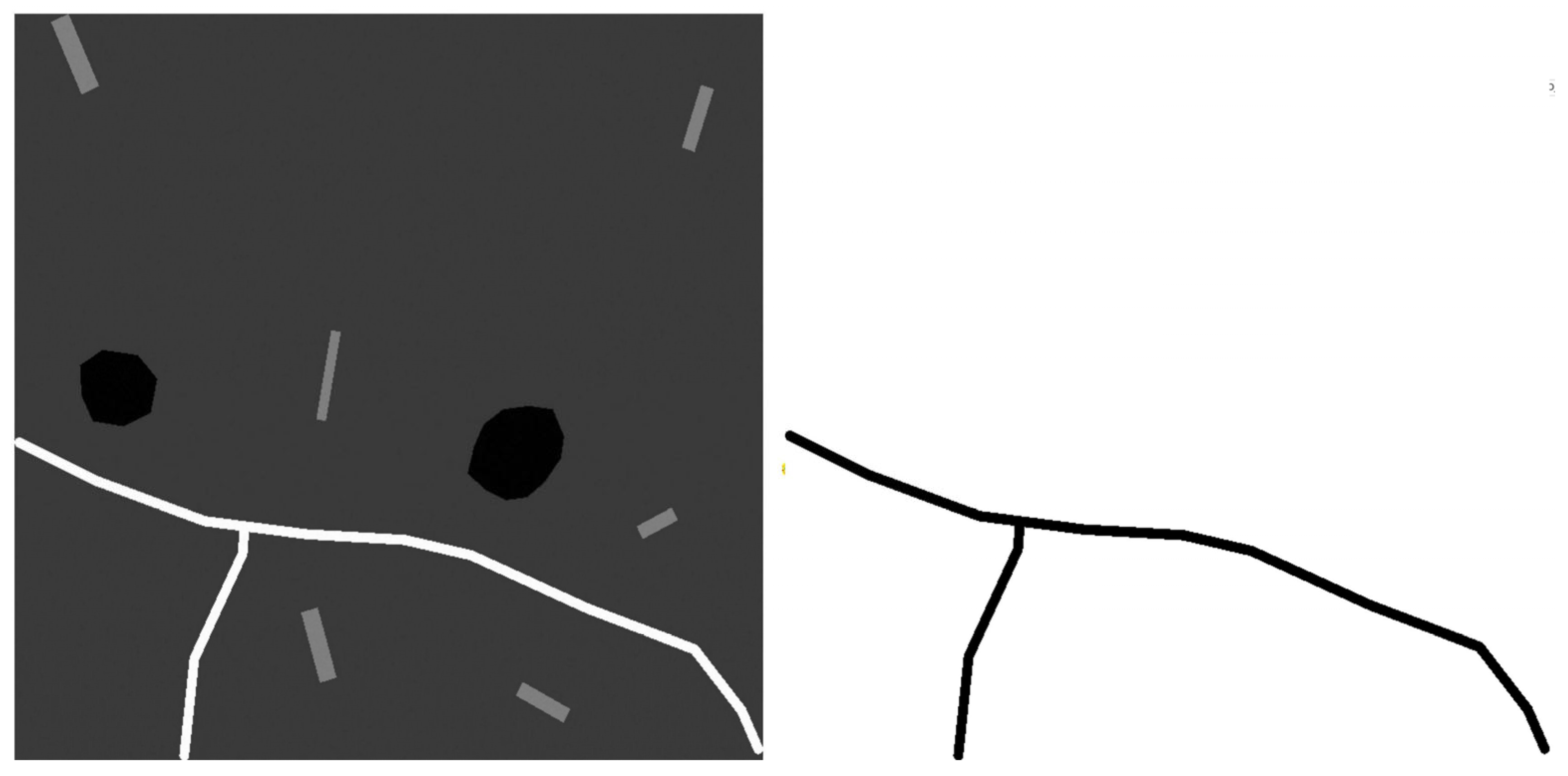

Effectiveness decreases significantly as variance increases. For example, consider scenario S4_R, which features high variance values—though not the maximum reached in this experiment. The Ambrosio-Tortorelli model works with consistent efficacy, as can be observed in the following images: it recognises the polygonal object as a single, unified entity. The Snake algorithm, on the other hand, also detects that there are other objects in the image, but it perceives them as fragmented—that is, it fails to establish continuity in their shape (

Figure 10).

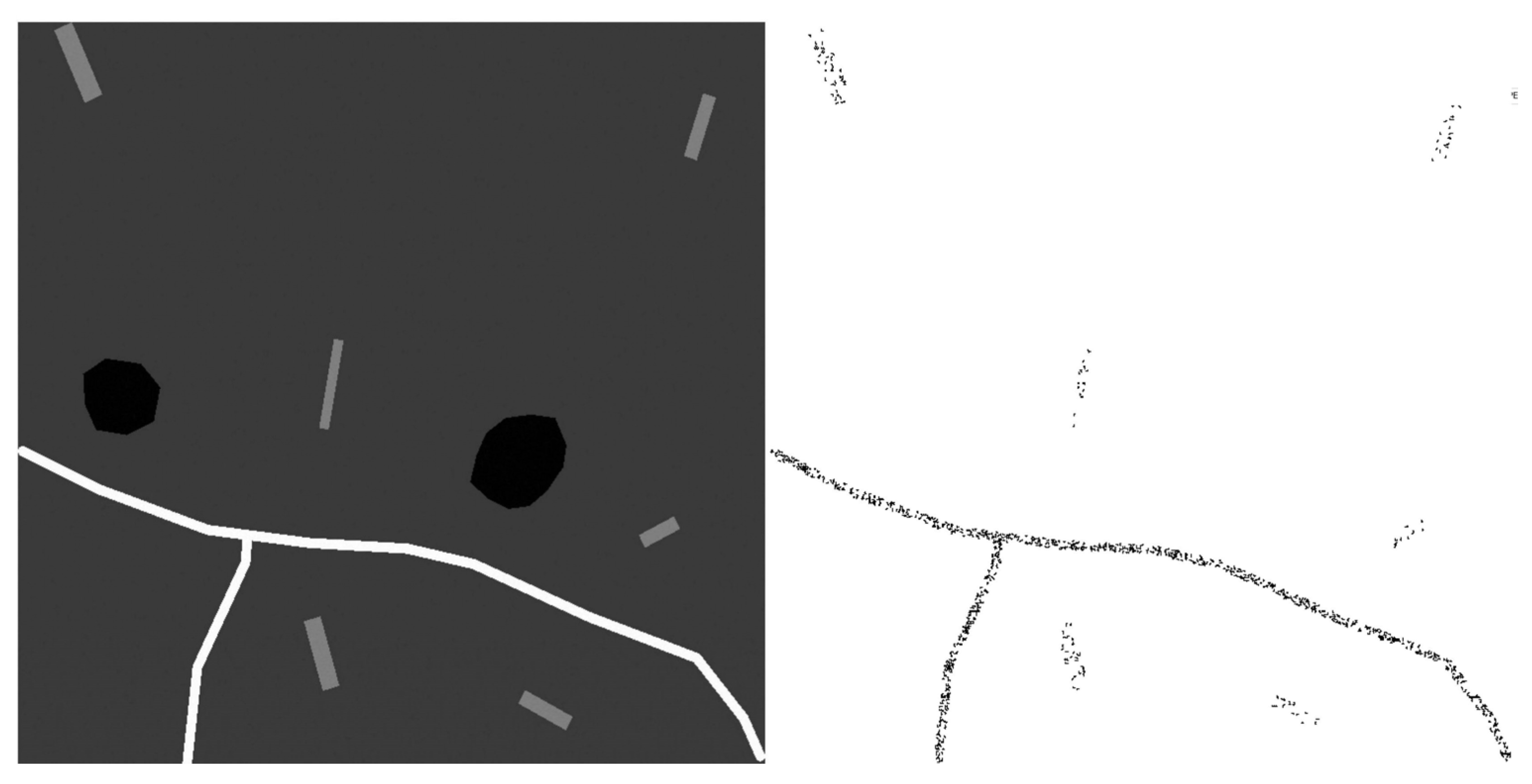

These differences between the two algorithms appear to diminish as the internal variance within objects decreases. Take scenario S3_R as an example: a certain degree of object fragmentation is still observed, although it is more contained; however, the perception that rectangular-shaped objects also exist is lost.

Figure 11.

Left: the original raster image for scenario S3_R. Right: the image reconstructed using the Snake model, showing the determination of edges and the pixels internal to the objects. Processing by the Authors.

Figure 11.

Left: the original raster image for scenario S3_R. Right: the image reconstructed using the Snake model, showing the determination of edges and the pixels internal to the objects. Processing by the Authors.

4. Discussion

This study has explored the application of the Mumford-Shah functional through two different numerical approximation techniques—the Ambrosio-Tortorelli (AT) method and the Active Contour Snake model—as potential tools to support satellite image segmentation for Land Use/Land Cover (LuLc) analysis within the Object-Based Image Analysis (OBIA) paradigm. From experimental results conducted on synthetic images with controlled complexity, significant differences emerge between the two methods, both in terms of numerical performance and algorithmic behavior.

It is essential to recall that these are still preliminary tests carried out on relatively simple and ad hoc objects; therefore, future work will involve analyses of real-world cases. The most notable strength of the AT method lies in its ability to identify an object’s boundary as a single, continuous entity, even when some pixels are missing. This stems from its mathematical formulation, which inherently identifies contrast in the presence of an object. In contrast, the Snake model, due to its evolutionary mathematical structure, tends to “skip over” potential boundaries when uncertain—for instance, in cases of low energy variance—and thus fails to recognize them. This phenomenon becomes more pronounced in noisy conditions, where AT still attempts to provide a global, albeit less detailed, response, while the Snake struggles significantly.

From a mathematical standpoint, both methods naturally face challenges in recognizing objects with low energetic variance, as they are built upon competing parameter families. It would likely be beneficial to adapt parameter settings regionally, differentiating them after an initial reconstruction—for example, by recalibrating parameters zone by zone following the initial identification of high-contrast areas.

In summary, in scenarios without internal noise, both methods achieve high accuracy levels when the energy differences between objects and background are sufficiently marked (scenarios S2–S10). However, in scenario S1, characterized by low energetic contrast, AT maintains an acceptable recognition capability, while the Snake fails completely, demonstrating greater sensitivity to weak gradients. When intra-class variance is introduced as noise, AT shows superior robustness, maintaining consistent performance across various noise levels (except in the extreme case S5_R). Conversely, the Snake exhibits a progressive decline in segmentation ability as noise increases, tending to fragment objects rather than delineate continuous contours.

Regarding output shape, AT tends to produce closed and continuous boundaries, identifying objects as unified entities even under noisy conditions. The Snake, on the other hand, may yield discontinuous or fragmented contours, especially where gradients are non-uniform or interrupted. The explanation for these behaviors lies in the fundamental nature of the two approaches: Ambrosio-Tortorelli is a static and global method, working simultaneously across the entire image by minimizing an energy functional that balances internal regularization, data fidelity, and contour length. Its variational nature makes it particularly suitable for identifying structures even in the presence of partial discontinuities. In contrast, the Snake is an evolutionary and local method, based on the dynamic evolution of an initial curve attracted by local gradients. This makes it more agile for well-defined, convex contours but also more vulnerable to noise, weak gradients, and the need for accurate initialization.

The results suggest that Ambrosio-Tortorelli may be preferable in contexts where the objects to be segmented exhibit low spectral contrast against the background, the presence of noise or variable internal texture, and the need for closed and topologically coherent contours. Conversely, Snakes can be effective in high-contrast scenarios with regular, convex-shaped objects, especially when supported by good initialization and well-calibrated parameters.

This research represents a preliminary investigation conducted on synthetic data. Future steps will require testing on real high-resolution satellite imagery, extending the analysis to more complex and irregular shapes typical of real landscapes, developing dynamic parameter adaptation based on local image characteristics—such as zone-by-zone calibration after initial region detection—and integrating post-processing techniques to regroup discontinuous boundaries (in the case of Snakes) and to enable semantic classification after segmentation.

In conclusion, the Mumford-Shah functional, in the two approximations tested here, confirms its potential as a powerful mathematical tool for segmentation within OBIA. The choice between AT and Snake is not absolute but depends on the application context, data quality, and required level of detail. Specifically, AT demonstrates greater reliability under noisy and low-contrast conditions, while Snakes can offer precision in more controlled and high-contrast scenarios. This work thus provides a solid comparative framework to guide the selection of segmentation algorithms based on the characteristics of the analyzed landscape, contributing to the optimization of workflows for sustainable landscape monitoring through remote sensing.