Submitted:

21 December 2025

Posted:

22 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

I. Introduction

II. Literature Review

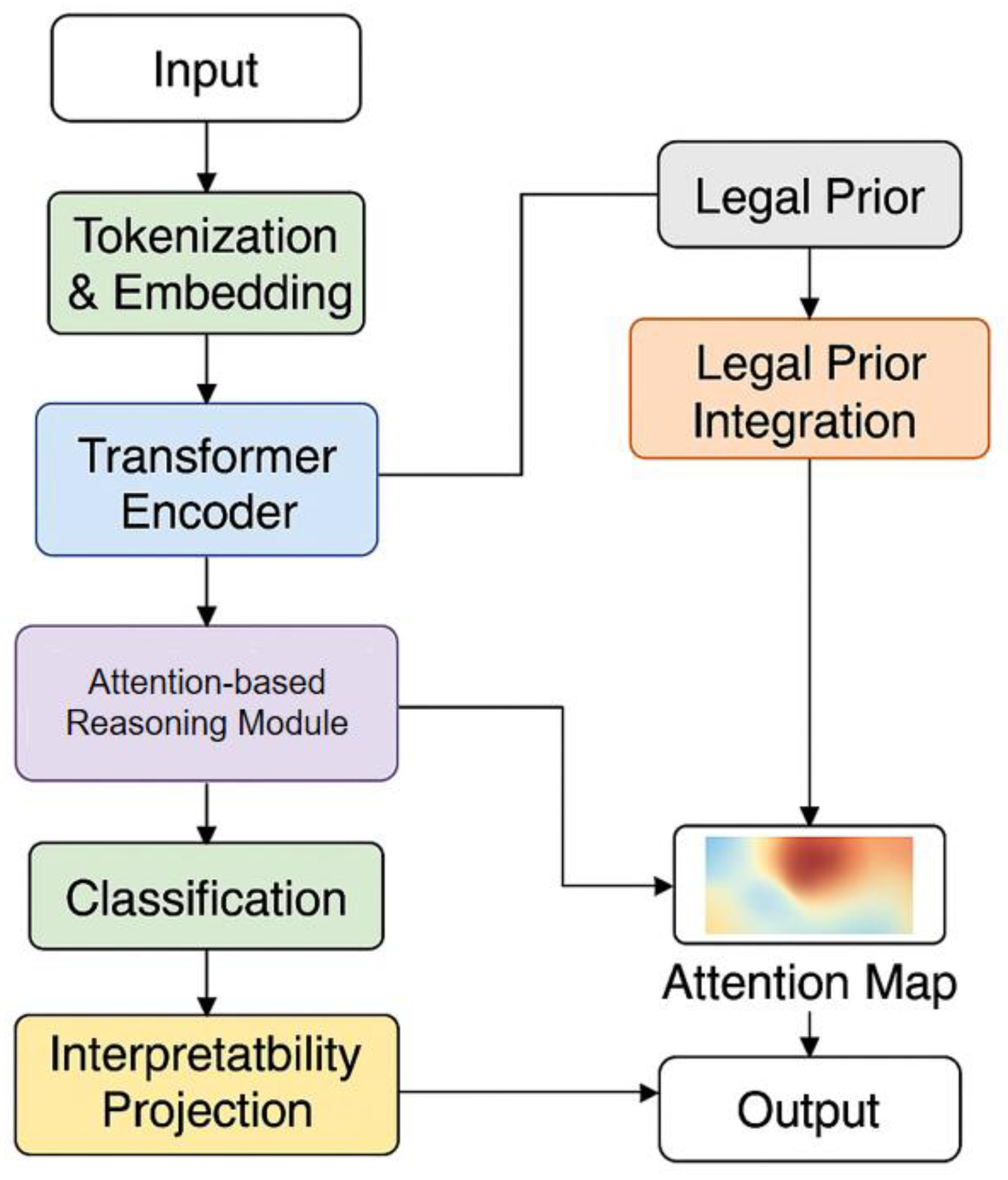

III. Proposed Framework

A. Legal Text Representation

B. Legal Prior Integration

C. Attention-Based Reasoning Module

D. Classification and Interpretability Projection

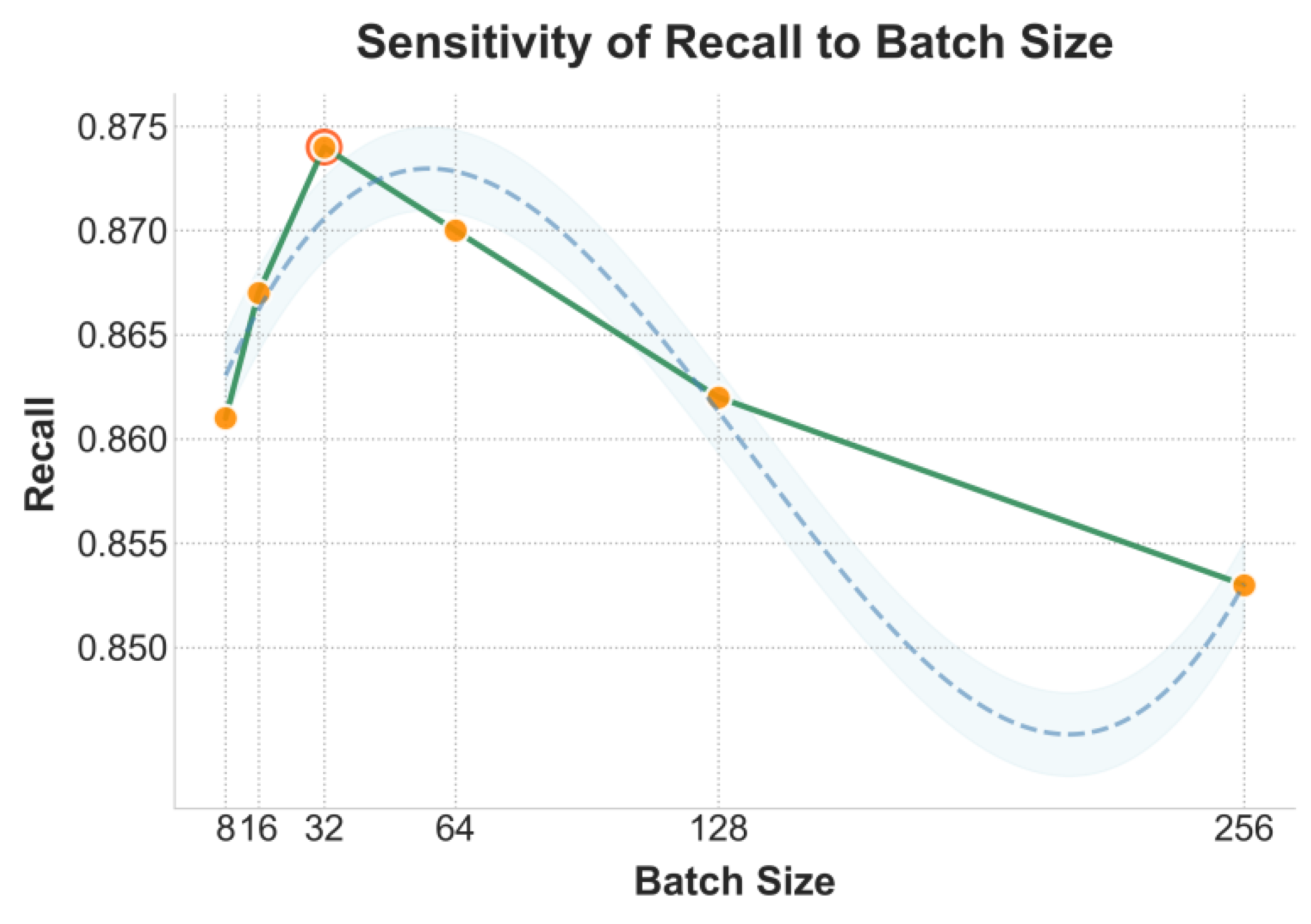

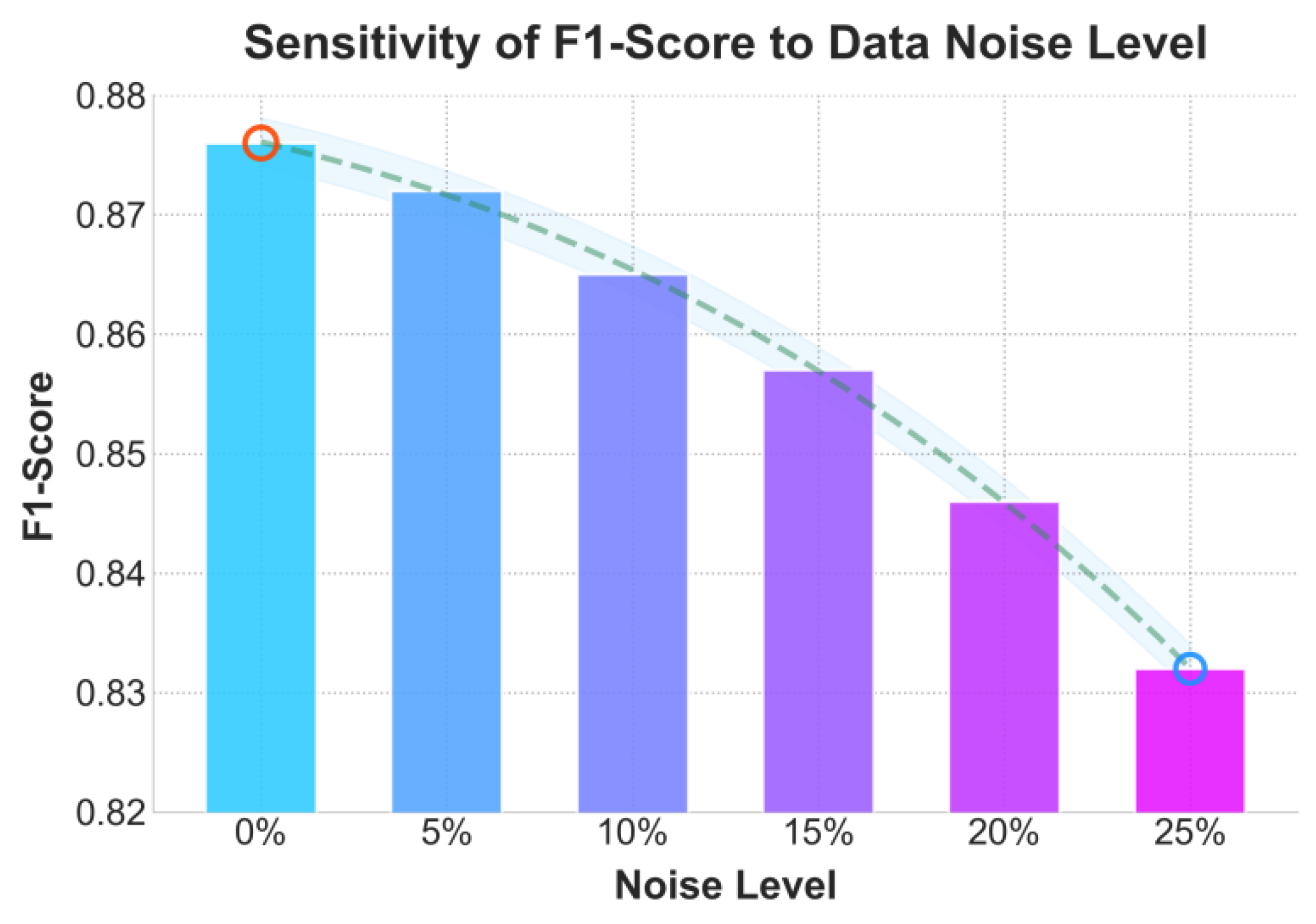

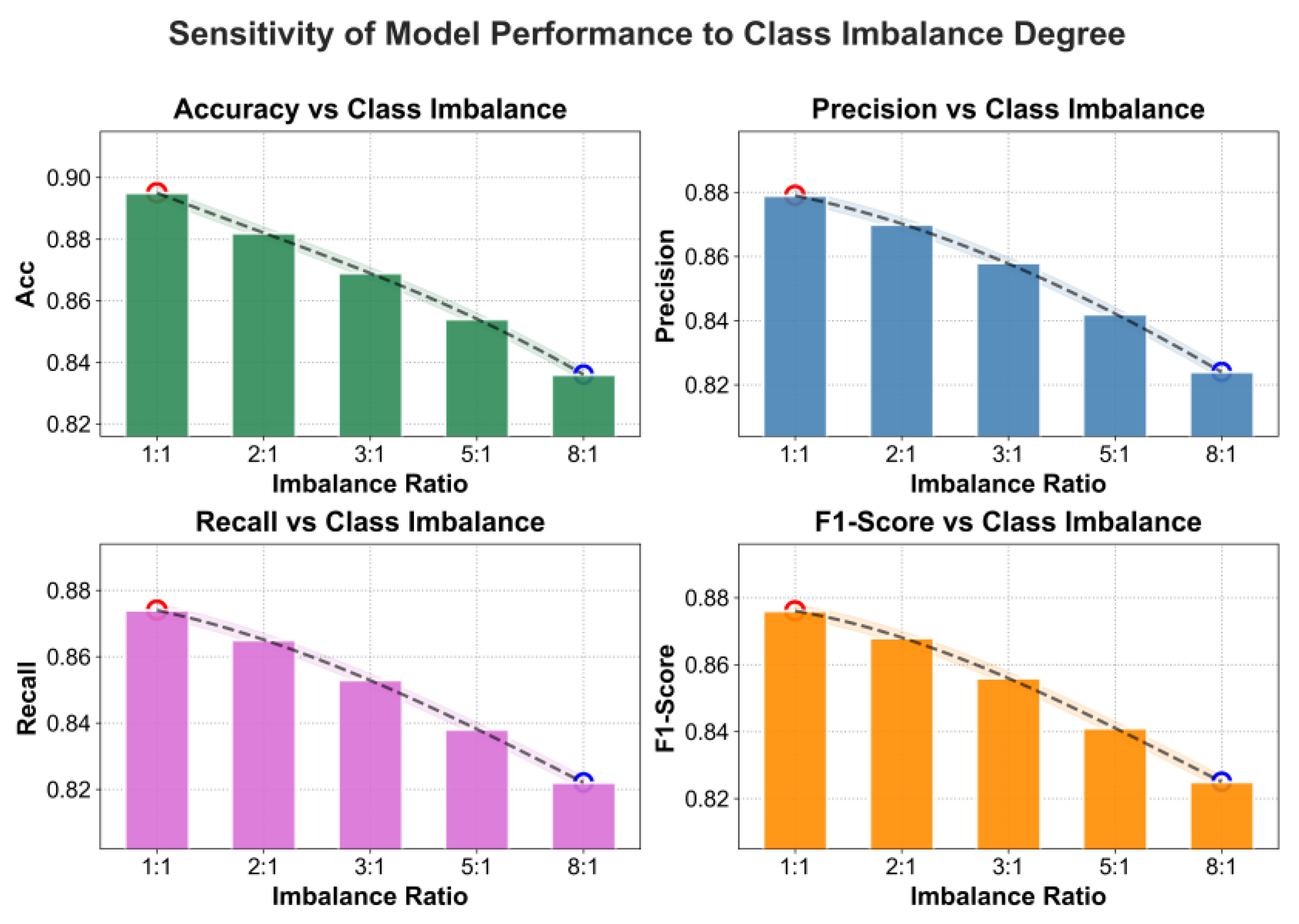

IV. Experimental Analysis

A. Dataset

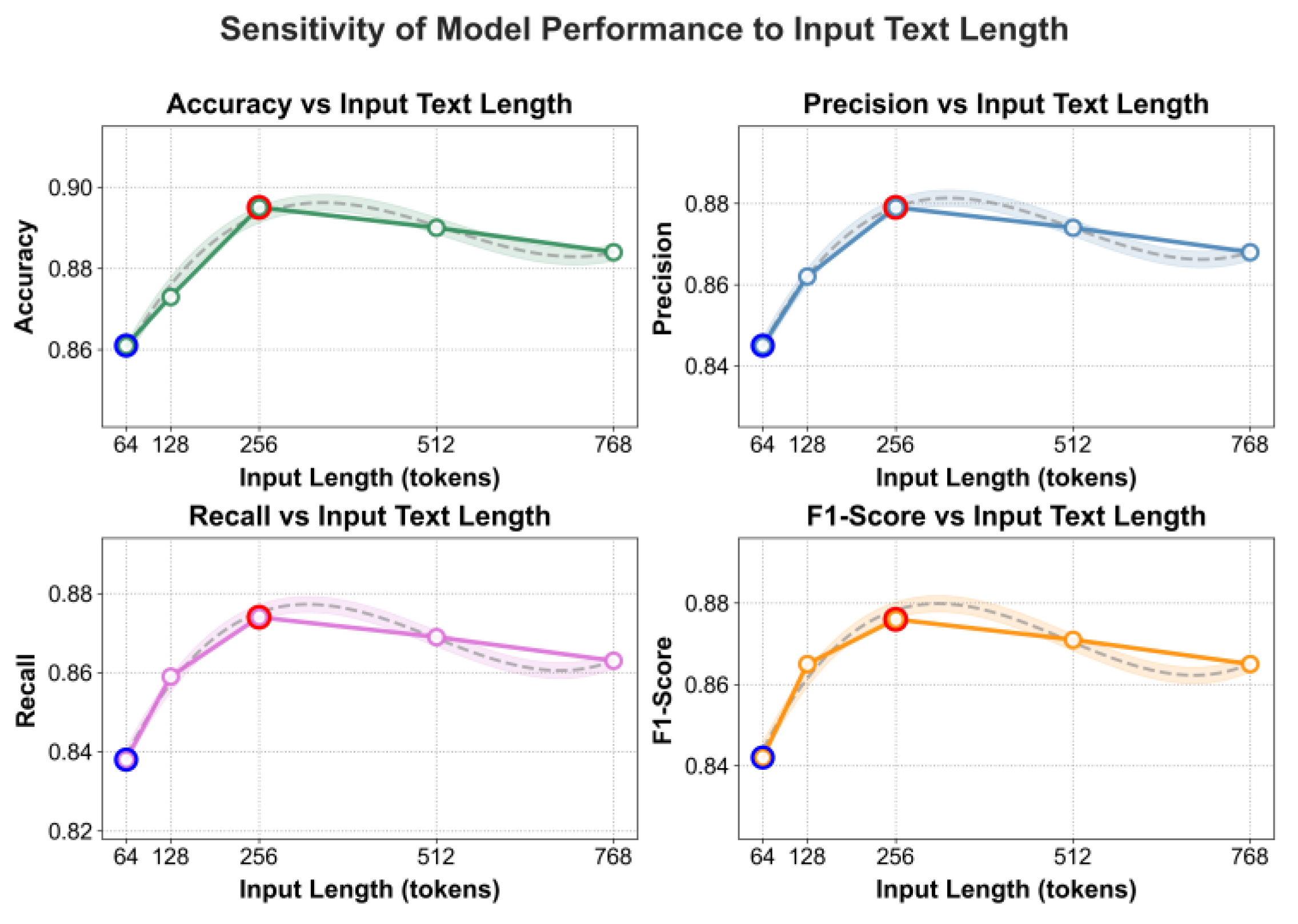

B. Experimental Results

V. Conclusion

References

- Chalkidis; Jana, A.; Hartung, D. LexGLUE: A benchmark dataset for legal language understanding in English. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2110.00976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niklaus, J.; Matoshi, V.; Rani, P. LEXtreme: A multilingual and multi-task benchmark for the legal domain. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2301.13126. [Google Scholar]

- Guha, N.; Nyarko, J.; Ho, D. LegalBench: A collaboratively built benchmark for measuring legal reasoning in large language models. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2023, vol. 36, 44123–44279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendrycks, D.; Burns, C.; Chen, A. CUAD: An expert-annotated NLP dataset for legal contract review. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2103.06268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modi, A.; Kalamkar, P.; Karn, S. SemEval 2023 Task 6: LegalEval—understanding legal texts. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2304.09548. [Google Scholar]

- Semo, G.; Bernsohn, D.; Hagag, B. ClassActionPrediction: A challenging benchmark for legal judgment prediction of class action cases in the United States. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2211.00582. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, Y.; Li, C.; Ng, V. Legal judgment prediction: A survey of the state of the art. In Proceedings of the International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence, 2022; pp. 5461–5469. [Google Scholar]

- Ariai, F.; Mackenzie, J.; Demartini, G. Natural language processing for the legal domain: A survey of tasks, datasets, models, and challenges. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2410.21306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louis, A.; van Dijck, G.; Spanakis, G. Interpretable long-form legal question answering with retrieval-augmented large language models. Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence 2024, vol. 38(no. 20), 22266–22275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, C. F.; Bhambhoria, R.; Dahan, S. Prototype-based interpretability for legal citation prediction. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2305.16490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahoney, C.; Gronvall, P.; Huber-Fliflet, N. Explainable text classification techniques in legal document review: Locating rationales without using human-annotated training text snippets. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE International Conference on Big Data, 2022; pp. 2044–2051. [Google Scholar]

- Herrewijnen, E.; Nguyen, D.; Bex, F. Human-annotated rationales and explainable text classification: A survey. Frontiers in Artificial Intelligence 2024, vol. 7, 1260952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qi, N. Deep learning and NLP methods for unified summarization and structuring of electronic medical records. Transactions on Computational and Scientific Methods 2024, vol. 4(no. 3). [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, M.; Liu, S.; Xu, W.; Long, S.; Yi, Y.; Lin, Y. Function-driven knowledge-enhanced neural modeling for intelligent financial risk identification. 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, W.; Jiang, M.; Long, S.; Lin, Y.; Ma, K.; Xu, Z. Graph neural network and temporal sequence integration for AI-powered financial compliance detection. 2025. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Yang, H.; Wang, M.; Dai, L.; Wu, Y.; Du, J. Federated graph neural networks for heterogeneous graphs with data privacy and structural consistency. 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, C.; Cheng, Z.; Wu, D.; Wang, Y.; Liu, F.; Qiu, Z. Structural generalization for microservice routing using graph neural networks. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2510.15210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Xia, J.; Yi, Y.; Chang, M.; Liu, Z. Discrimination of financial fraud in transaction data via improved Mamba-based sequence modeling. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, R.; Wang, H.; Sun, Y.; Wu, Q.; Lian, L.; Zhang, R. Behavioral anomaly detection in distributed systems via federated contrastive learning. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2506.19246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, H.; Long, N.; Yao, G. Federated anomaly detection for multi-tenant cloud platforms with personalized modeling. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2508.10255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, R.; Chang, W. C.; Hu, J.; Gao, M. Federated learning-driven health risk prediction on electronic health records under privacy constraints. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Y.; Qi, N.; Deng, Y.; Xue, Z.; Gong, M.; Zhang, W. Autonomous resource management in microservice systems via reinforcement learning. In Proceedings of the 2025 8th International Conference on Computer Information Science and Application Technology (CISAT), 2025; pp. 991–995. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, G.; Liu, H.; Dai, L. Multi-agent reinforcement learning for adaptive resource orchestration in cloud-native clusters. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2508.10253. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Han, S.; Wang, S.; Wang, M.; Meng, R. Collaborative evolution of intelligent agents in large-scale microservice systems. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2508.20508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Zhuang, Y.; Zhang, R. Adaptive human-computer interaction strategies through reinforcement learning in complex environments. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2510.27058. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, Y.; Li, Z.; Yin, Y. Advancing legal citation text classification: A Conv1D-based approach for multi-class classification. Journal of Theory and Practice of Engineering Science 2024, vol. 4(no. 2), 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benedetto; Sportelli, G.; Bertoldo, S. On the use of pretrained language models for legal Italian document classification. Procedia Computer Science 2023, vol. 225, 2244–2253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, R.; Boit, S.; Gudivada, V. A survey of text representation and embedding techniques in NLP. IEEE Access 2023, vol. 11, 36120–36146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagh, V.; Khandve, S.; Joshi, I. Comparative study of long document classification. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE Region 10 Conference (TENCON), 2021; pp. 732–737. [Google Scholar]

- Liapis, C. M.; Kyritsis, K.; Perikos, I. A hybrid ensemble approach for Greek text classification based on multilingual models. Big Data and Cognitive Computing 2024, vol. 8(no. 10), 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Wu, L.; Chen, J. A comparative study of automated legal text classification using random forests and deep learning. Information Processing & Management 2022, vol. 59(no. 2), 102798. [Google Scholar]

| Method | Acc | Precision | Recall | F1-Score |

| 1DCNN [26] | 0.842 | 0.818 | 0.801 | 0.809 |

| BERT [27] | 0.878 | 0.861 | 0.855 | 0.858 |

| Text2Vec [28] | 0.856 | 0.832 | 0.824 | 0.828 |

| MLP [29] | 0.864 | 0.846 | 0.839 | 0.842 |

| XGBoost [30] | 0.871 | 0.852 | 0.847 | 0.849 |

| Random Forest [31] | 0.867 | 0.845 | 0.838 | 0.841 |

| Ours | 0.895 | 0.879 | 0.874 | 0.876 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).