1. Introduction

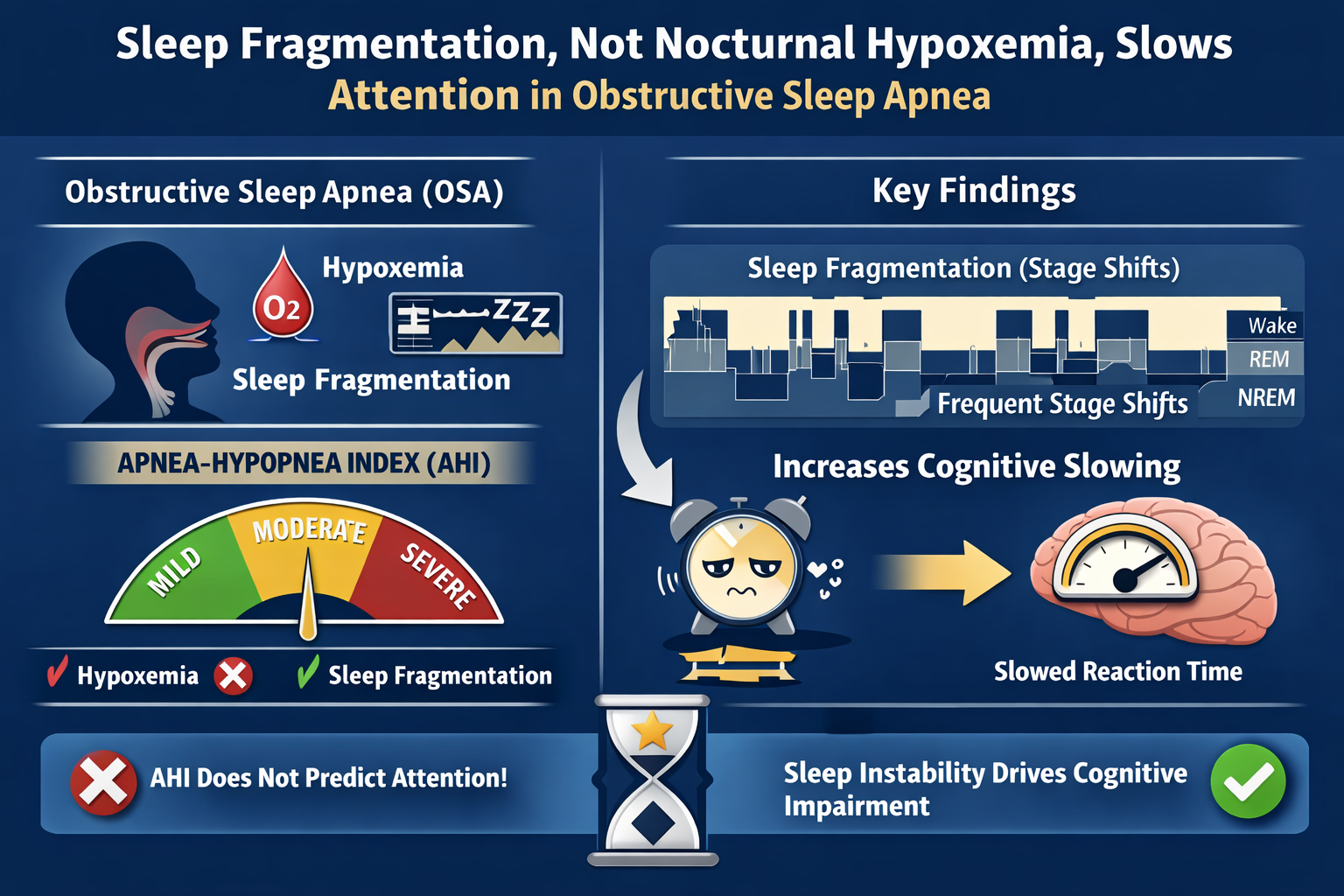

Global estimates indicate that obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) affects nearly one billion adults worldwide, with prevalence ranging from ~9% to 38% depending on diagnostic criteria [

1]. The OSA is characterized by recurrent upper-airway collapse, resulting in intermittent hypoxemia and sleep fragmentation that disrupts restorative stages such as slow-wave and REM sleep [

2]. Obstructive sleep apnea is conventionally diagnosed and classified in severity based on the Apnea–Hypopnea Index (AHI) [

3]. However, AHI may not entirely reflect the physiological burden of OSA, including desaturation depth and duration, as well as sleep fragmentation [

4].

Previous studies have reported the presence of cognitive deficits in OSA patients [

5,

6]. Attention is a core cognitive domain, since the other domains depend on attentional performance [

7]. Consistent with limitations of the AHI, the association of AHI with attentional deficits has been weak or even absent [

8,

9,

10]. These findings suggest that the physiological consequences of OSA (desaturation and sleep fragmentation) may exert a more direct influence on attention dysfunction.

Indeed, evidence from multiple modalities indicates that OSA is consistently associated with attentional alterations, as highlighted by the recent systematic review on MRI data [

11]. Specifically, previous research has shown that individuals affected by this condition exhibit extended reaction time (RT) [

9,

10] . However, these studies were conducted with a small sample size of OSA patients and controls. Additionally, the controls did not undergo polysomnography type 1 to rule out sleep disorders, and the data on RT were not standardized.

Based on this context, the present study had two main objectives. The first objective was to compare attentional performance between a larger sample of patients with OSA and sleep-disorder-free controls, verified by full-night type 1 polysomnography, using a 15-minute Go/No-Go task (Continuous Visual Attention Test – CVAT) as well as standardized measures of RT. The second objective was to clarify the strength of association between RT — as an index of vigilance — and markers of sleep fragmentation and/or nocturnal hypoxemia, beyond conventional severity metrics such as the AHI.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

Between December 2021 and January 2025, outpatients undergoing type 1 polysomnography (PSG) at a private Sleep Medicine Service (RIOSONO) in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, were asked to participate in this study. Of them, 207 consented. Eligible participants were aged between 18 and 60 and could present with or without sleep-related complaints.

A semi-structured clinical interview was conducted to screen for exclusion criteria, which included current or past history of alcohol or drug abuse, use of psychotropic medication, neurological (stroke, traumatic brain injury, epilepsy) or psychiatric conditions, pulmonary or neuromuscular disorders, and pregnancy. All participants underwent the 15-minute version of the CVAT before PSG. Following the overnight PSG, the Epworth Sleepiness Scale and the Hamilton Depression and Anxiety Rating Scales were completed.

Two hundred and seven adults underwent full-night, type 1 polysomnography and completed a 15-minute Go/No-Go Continuous Visual Attention Test (CVAT). Based on PSG results, after exclusion of other primary sleep disorders (e.g., severe insomnia, narcolepsy), 84 individuals with an AHI ≥ 5 events/h were classified as having OSA and included in the patient group, and 22 individuals with normal PSG findings were included in the control group. The remaining 101 participants were excluded due to other sleep disorders or not meeting specific inclusion/exclusion criteria for the study groups.

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Federal University of the State of Rio de Janeiro (CAAE: 69406817.1.0000.5258). All participants provided written informed consent (Declaration of Helsinki).

2.2. Polysomnography and Parameter Quantification

Full-night assisted polysomnography was performed using Sleep and monitored with digital polysomnography (BNT 36/BNT Poli; Emsamed, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil), with comprehensive monitoring including standard electroencephalographic (C3-A2, C4-A1, O1-A2, O2-A1), electrooculographic, and electromyographic (submental and bilateral tibialis anterior) leads, supplemented by respiratory measurements (nasal pressure transducer, oronasal thermistor, thoracic/abdominal strain belts) and continuous pulse oximetry with body position monitoring. Obstructive sleep apnea was diagnosed with an apnea-hypopnea index (AHI) ≥5 events/hour according to the 2012 American Academy of Sleep Medicine criteria [

3], defining apnea as ≥90% airflow cessation for ≥10 seconds and hypopnea as ≥30% airflow reduction with ≥3% oxygen desaturation or arousal. Oxygen desaturation parameters included: event frequency (D1, dips ≥3%), desaturation index (D2), duration of hypoxemia (D3, SpO₂<90%), and basal saturation (D4). Sleep fragmentation was assessed using the microarousal index (F1), sleep stage shifts (F2), which were operationally defined as transitions between different sleep stages occurring between consecutive 30-second epochs and sustained for at least one full epoch (≥30 s), in accordance with standard AASM scoring rules [

3] and previous approaches to quantify sleep continuity [

12], wakefulness after sleep onset (F3), and sleep fragmentation index (F4). We quantified the Sleep Fragmentation Index (SFI) as the total number of awakenings/shifts to Stage 1 (from deeper non-rapid eye movement [NREM] or REM sleep) divided by the total sleep time in hours [

13]. Sleep efficiency was calculated as the total sleep time relative to the time in bed, minus the sleep onset latency, with all analyses restricted to artifact-free periods.

2.3. Attention Assessment

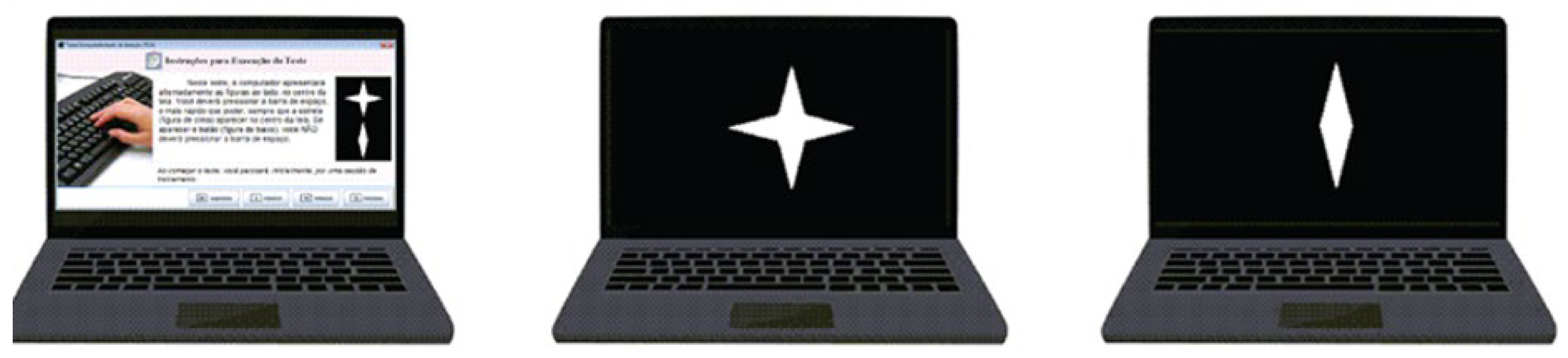

Participants completed the 15-minute Computerized Visual Attention Test (

CVAT, Figure 1), administered on a Windows 10 laptop (13” LCD display, <30 ms latency). Testing occurred in a quiet examination room with standardized conditions: 50 cm viewing distance, visual acuity ≥20/30 (corrected if needed).

The task required responses to target stimuli (star) among distractors (diamond). The paradigm consisted of 6 blocks (3 sub-blocks each, 20 trials/sub-block) with randomized interstimulus intervals (1, 2, or 4 s). Stimuli appeared for 250 ms. Primary outcomes were omission errors (OE), commission errors (CE), reaction time of correct responses (RT), and variability of reaction time (VRT - standard deviation of individual reaction times of correct responses). Participants were instructed to press the space bar as quickly and accurately as possible with the dominant hand.

2.4. Reference Group

Next, the raw CVAT parameters were standardized based on age and sex using a normative sample of 1,244 individuals who completed the 15-minute CVAT. The raw scores were normalized to rule out the effects of age and sex.

The reference group consisted of a subsample of individuals who underwent mandatory medical and psychological assessments for certification of fitness to drive between December 2021 and January 2025 in Brazil. These assessments were conducted by certified physicians and psychologists according to national regulatory standards. All individuals who presented for assessment were invited to participate in a national normative study involving the CVAT. Consenting participants completed the 15-minute version of the CVAT on the same day and at the same location as their health examination for obtaining a driver’s license. A total of 1,244 individuals who met the general inclusion criteria and passed the mandatory driving fitness assessment were included in the reference group. Eligibility required a normal neurological examination, intact visual and auditory function, and Mini-Mental State Examination scores within normative limits adjusted for educational level. Furthermore, all subjects scored above the 25th percentile on validated psychometric measures of intelligence quotient, global attention, and memory.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

Demographic and PSG variables were compared using a t-test for independent samples or a chi-squared test, where appropriate. The study was divided into two parts.

First objective: A univariate analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was conducted with raw reaction time (RT) as the dependent variable, group (OSA vs. control) as the fixed factor, and age and sex as covariates. To confirm the results, we also performed an ANOVA using age- and sex-adjusted Z-scores for reaction time, derived from a normative database of 1,244 healthy individuals. A Pearson correlation was calculated between AHI and reaction time (RT) within the OSA group to assess whether the severity of sleep-disordered breathing predicted cognitive slowing.

Second objective: Secondly, within the OSA group, the association between normalized reaction time and the measures of desaturation and sleep fragmentation derived from polysomnography. For this, all measures of desaturation (D1 – D4) and sleep fragmentation (F1 – F4) were included in a backward regression model. To avoid multicollinearity, first, all variables were forced into the model, and those with a variance inflation factor (VIF) of ≥5 were excluded from the backward model to reduce redundancy. Variable entry and removal were based on the F-probability criterion (0.05 and 0.10, respectively).

3. Results

3.1. Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

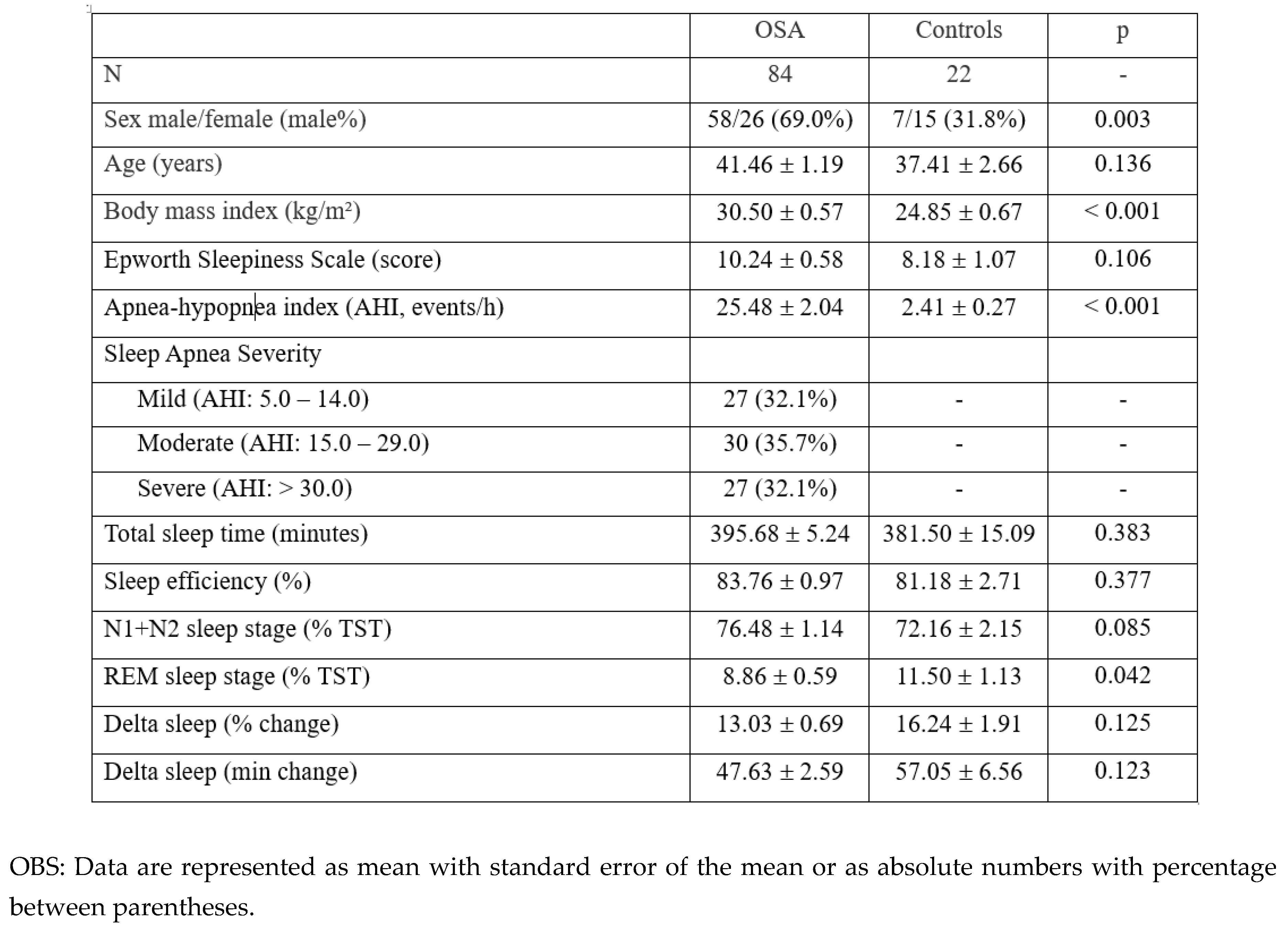

As shown in

Table 1, individuals with OSA were predominantly male and had higher BMI compared to comparison group (

p = 0.003 and

p < 0.001, respectively). We did not find significant group differences in age or subjective sleepiness (Epworth Sleepiness Scale; all

p > 0.05). The AHI was significantly higher in the OSA group (

p < 0.001), with a balanced number of mild, moderate, and severe OSA across the patient group. No significant differences were observed in total sleep time, sleep efficiency, or delta sleep (all

p > 0.05) between the two groups. In contrast, REM sleep percentage was lower in OSA subjects (

p = 0.042).

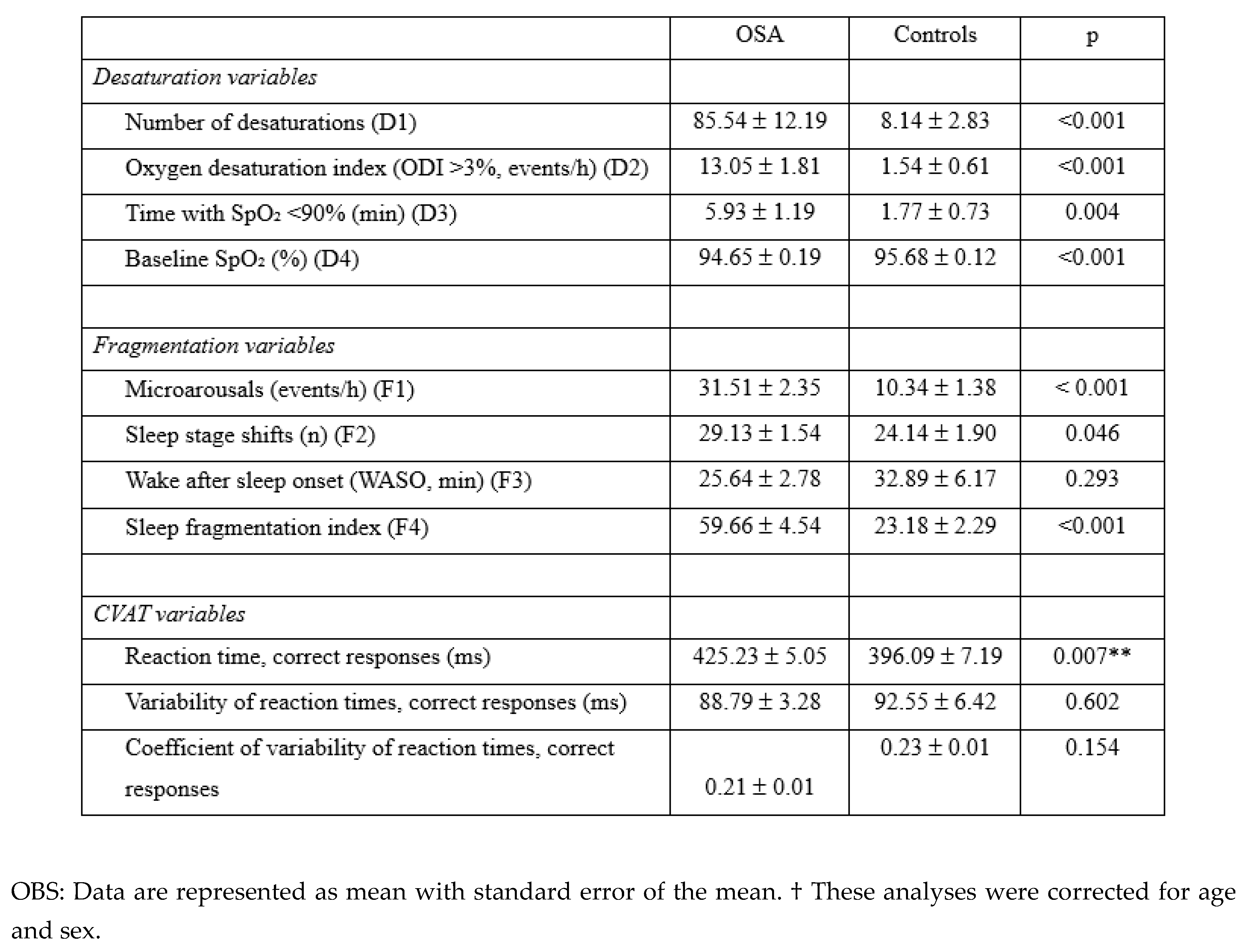

3.2. Desaturation and Sleep Fragmentation

As shown in

Table 2, compared to the comparison group, participants with OSA exhibited significantly more severe nocturnal oxygen desaturation, as reflected by a higher number of desaturation events, an elevated oxygen desaturation index (ODI), and a longer cumulative time with SpO₂ <90% (all

p < 0.01). Baseline oxygen saturation was also lower in the OSA group (

p < 0.001). OSA subjects showed greater sleep fragmentation, with higher microarousal index and fragmentation index (both

p < 0.001), and a modest increase in the number of sleep stage transitions (

p = 0.046). Wake after sleep onset (WASO) did not differ significantly between groups.

3.3. First Objective

The ANCOVA with raw mean reaction time revealed a statistically significant main effect of group on reaction time (F (1, 102) = 4.91, p = .029, partial η² = .046), indicating that individuals with OSA had significantly slower RTs compared to the control group after controlling for age and sex. Neither age nor sex was a significant covariate (p = .106 and p = .678, respectively). The ANOVA with the mean reaction time normalized for age and sex indicated a significant effect of group (F (1, 104) = 8.30, p = .005, partial η² = .074). These results confirm that the OSA group performed significantly worse than the comparison group, further supporting the robustness of the group difference.

No significant association between AHI and normalized RT within the OSA group was found (r = .093, p = .398), replicating previous findings that suggest the severity of OSA, as measured by AHI, does not predict reaction time performance within individuals with OSA.

3.4. Second Objective

The regression model, which included all desaturation measures (D1–D4) and sleep-fragmentation indices (F1–F4), showed that event frequency (D1, number of desaturations ≥3%) and the desaturation index (D2) exhibited VIF values above 5 but below 10, indicating moderate collinearity. These variables were therefore removed during the backward linear regression procedure, and all remaining predictors showed VIF values below 4. In the final model, only sleep-stage instability (F2) remained significant. Higher sleep-stage instability was associated with longer normalized reaction time, reflecting worse intrinsic alertness (F (1,82) = 6.512, p = .013, R= .271, p = .013).

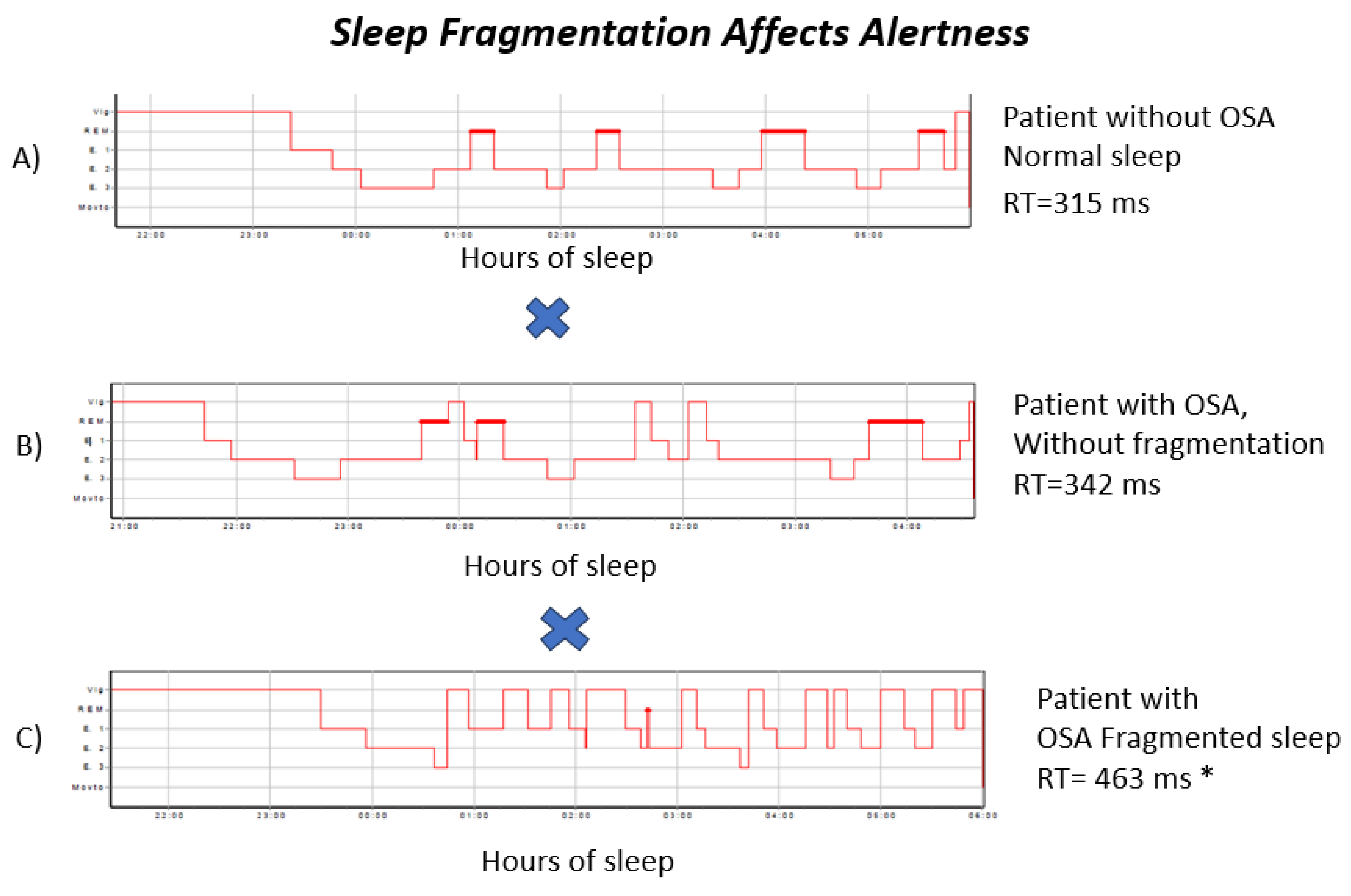

The hypnograms in

Figure 2 show examples of a control subject, one OSA participant without fragmentation, and one OSA participant with fragmentation. This illustrates that, despite elevated AHI values, no clear correlation is observed between the apnea–hypopnea that AHI alone does not capture the degree of attentional impairment associated with prolonged reaction times.

4. Discussion

This study confirms our previous study that individuals with OSA exhibit significantly slower reaction times compared to rigorously verified, sleep-disorder-free controls, even after adjusting for age and sex using z-scores referenced to a large normative dataset. The AHI showed no association with attentional performance, highlighting the limited value of this traditional severity marker in predicting cognitive impairment. Of all polysomnography-derived measures, only sleep stage shifts correlated with slower RT. These results indicate that attentional deficits in OSA are dissociable from respiratory event frequency and are likely driven by sleep fragmentation.

The present finding of an increase in RT using another larger OSA sample and a control group that had Type 1 PSG demonstrated that our previous study [

9,

10] is stable and reliable. Moreover, the use of Z- scores from a large normative sample gives further support for the reliability of our results. Although the control group included a higher proportion of women, who typically exhibit slower reaction times than males [

14], the OSA group, which was predominantly male, still showed significantly longer reaction times. This pattern suggests that slowing is more strongly driven by OSA-related mechanisms than by sex differences. In fact, the overrepresentation of women in the control group may have introduced a conservative bias, potentially increasing mean reaction times in that group and reducing the between-group contrast, thereby further reinforcing the robustness of our findings.

Our results further indicate that sleep continuity and microarchitecture are key factors in reaction time (RT) impairment associated with OSA. This result supports previous studies linking microstructural alterations (e.g., compound action potential rate, spindle dynamics) to cognitive dysfunction [

15], as well as evidence that measures based on sleep continuity better predict cognitive gains related to CPAP use than nocturnal hypoxemia [

16,

17].

The finding of an absence of association between desaturation indices and slowness in OSA is in contrast with the results of Kainulainen et al. [

5]. These authors use a refined metric of hypoxic load and found that this metric was associated with slow responses in the Psychomotor Vigilance Task (PVT) [

5]. Despite the fact that we did not calculate this metric, it is important to consider that the PVT selectively requires stimulus-guided vigilance, which may be particularly susceptible to hypoxemia-related fluctuations in alertness. In contrast, the Go/No-Go paradigm used in the present investigation requires sustained monitoring and descending inhibitory control, in addition to motor speed. Neuroimaging data indicate that these partially dissociable attentional networks are modulated by sleep stage stability, suggesting that fragmentation acts through pathways extending beyond transient alertness failures [

18].

In the multivariate context, when physiological markers are evaluated concurrently, conventional desaturation indices lose their predictive value for attentional performance, whereas sleep-stage shifts retain independent explanatory significance. This pattern supports the interpretation that disruption of stable sleep continuity represents a meaningful pathological mechanism rather than a statistical artefact. In a Go/No-Go paradigm, reaction-time slowing should therefore not be regarded as mere psychomotor delay; instead, it reflects reduced efficiency of sustained monitoring and top-down inhibitory control – attentional processes that are particularly sensitive to fragmentation-related instability in sleep architecture.

From a mechanistic perspective, recurrent transitions between non-REM (NREM) and REM (rapid eye movement) sleep are known to disrupt autonomic balance [

19] and thalamo-cortical organization [

20], both of which are crucial for maintaining attentional networks. Furthermore, instability in sleep stages is postulated to compromise the neuro-dependent mechanism of “neuronal pumping” described by Jiang-Xie et al. [

21]. In this mechanism, synchronized neuronal activation drives waves of interstitial fluid essential for glymphatic clearance. Disruption of neuronal synchrony due to fragmentation can negatively affect this process, leading to decreased metabolic clearance. Consequently, instability in sleep architecture may be directly linked to attentional functioning.

Sleep-stage shifts have emerged as a clinically relevant marker of attentional vulnerability in OSA. Beyond indicating non-restorative sleep, repeated shifts in vigilance states trigger sympathetic surges and cardiometabolic strain. Remarkedly, arousal burden has been independently associated with hypertension, regardless of apnea severity [

22], supporting fragmentation as an active pathological driver rather than merely a consequence of respiratory events. Interventions that enhance sleep continuity – through optimized CPAP adherence, behavioral strategies, or targeted adjunctive therapies – may therefore provide cognitive benefits that exceed those achieved by AHI reduction alone. Despite this clinical relevance, fragmentation metrics such as Sleep-stage shifts remain absent from most routine PSG reports. Incorporating them into standard evaluation may improve cognitive risk stratification and guide more mechanism-based management in OSA.

A few limitations warrant consideration. First, the cross-sectional design precludes causal inference. Secondly, residual confounding, such as genetic susceptibility or vulnerability to sleep disruption, cannot be excluded. Third, fragmentation metrics did not distinguish between respiratory-related and spontaneous arousals. Fourth, high-resolution hypoxic indices, such as hypoxic load[

5], were unavailable due to software constraints. Finally, although sleep stage shifts showed independent predictive value, routine clinical implementation is limited by the lack of standardized automated scoring tools. Future research should develop automated microstructure metrics and use longitudinal designs to validate their clinical relevance.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, the average reaction time was significantly increased in individuals with OSA, independent of AHI severity. Importantly, sleep-stage shifts, but not oxygen desaturation, predicted slower responses in a Go/No-Go Continuous Performance Test, identifying sleep continuity as a modifiable target for reducing cognitive deficits in OSA. These findings support an expansion of the current diagnostic paradigm for obstructive sleep apnea by complementing traditional respiration-centered metrics with sleep-continuity–based risk markers that more accurately capture attentional deficits. Within a precision sleep medicine framework, the incorporation of sleep fragmentation measures can enhance individualized phenotyping, enable the identification of patients at increased neurocognitive risk, and inform targeted interventions aimed at stabilizing sleep architecture, rather than relying solely on AHI-based severity classification.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.L.d.S.B., S.L.S., E.v.D., and K.-U.L.; methodology, M.L.d.S.B., S.L.S., E.v.D., and K.-U.L.; software, M.L.d.S.B.; validation, M.L.d.S.B., S.L.S., E.v.D., A.M., and K.-U.L.; formal analysis, M.L.d.S.B. and E.v.D.; investigation, M.L.d.S.B., A.M., A.L.C., and K.-U.L.; resources, S.L.S. and K.-U.L.; data curation, M.L.d.S.B. and A.M.; writing—original draft preparation, M.L.d.S.B., E.v.D., and K.-U.L.; writing—review and editing, S.L.S., E.v.D., and K.-U.L.; visualization, M.L.d.S.B., A.L.C., and K.-U.L.; supervision, S.L.S., E.v.D., and K.-U.L.; project administration, S.L.S. and K.-U.L.; funding acquisition, E.v.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by a personal senior postdoctoral grant awarded to EvD by the Fundação Carlos Chagas Filho de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado do Rio de Janeiro (FAPERJ).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the local Ethics Committee (CAAE: 30547720.3.0000.0008).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Raw deidentified data will be available upon request made to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Bezerra, M.L.d.S.; van Duinkerken, E.; Simões, E.; Schmidt, S.L. General low alertness in people with obstructive sleep apnea. J. Clin. Sleep Med. 2024, 20, 689–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bezerra, M.L.d.S.; van Duinkerken, E.; Simões, E.; Schmidt, S.L. General low alertness in people with obstructive sleep apnea. J. Clin. Sleep Med. 2024, 20, 689–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kapur, V.K.; Auckley, D.H.; Chowdhuri, S.; Kuhlmann, D.C.; Mehra, R.; Ramar, K.; Harrod, C.G. Clinical Practice Guideline for Diagnostic Testing for Adult Obstructive Sleep Apnea: An American Academy of Sleep Medicine Clinical Practice Guideline. J. Clin. Sleep Med. 2017, 13, 479–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgeson, T.; Atkins, L.; Zahnleiter, A.; I Terrill, P.; Eeles, E.; Coulson, E.J.; Szollosi, I. Sleep fragmentation and hypoxaemia as key indicators of cognitive impairment in patients with obstructive sleep apnoea. Sleep Sci. Pr. 2025, 9, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kainulainen, S.; Duce, B.; Korkalainen, H.; Leino, A.; Huttunen, R.; Kalevo, L.; Arnardottir, E.S.; Kulkas, A.; Myllymaa, S.; Töyräs, J.; et al. Increased nocturnal arterial pulsation frequencies of obstructive sleep apnoea patients is associated with an increased number of lapses in a psychomotor vigilance task. ERJ Open Res. 2020, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelelli, P.; Macchitella, L.; Toraldo, D.M.; Abbate, E.; Marinelli, C.V.; Arigliani, M.; De Benedetto, M. The Neuropsychological Profile of Attention Deficits of Patients with Obstructive Sleep Apnea: An Update on the Daytime Attentional Impairment. Brain Sci. 2020, 10, 325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lezak, M. D.; Howieson, D. B.; Bigler, E. D.; Tranel, D. Neuropsychological assessment, 5th ed.; Oxford University Press, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Nance, R.M.; Fohner, A.E.; McClelland, R.L.; Redline, S.; Bryan, R.N.; Desiderio, L.; Habes, M.; Longstreth, J.W.; Schwab, R.J.; Wiemken, A.S.; et al. The Association of Upper Airway Anatomy with Brain Structure: The Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. Brain Imaging Behav. 2024, 18, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simões, E.N.; Padilla, C.S.; Bezerra, M.S.; Schmidt, S.L. Analysis of Attention Subdomains in Obstructive Sleep Apnea Patients. Front. Psychiatry 2018, 9, 435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezerra, M.L.d.S.; van Duinkerken, E.; Simões, E.; Schmidt, S.L. General low alertness in people with obstructive sleep apnea. J. Clin. Sleep Med. 2024, 20, 689–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaderi, S.; Mohammadi, S.; Mohammadi, M. Obstructive sleep apnea and attention deficits: A systematic review of magnetic resonance imaging biomarkers and neuropsychological assessments. Brain Behav. 2023, 13, e3262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laffan, A.; Caffo, B.; Swihart, B.J.; Punjabi, N.M. Utility of Sleep Stage Transitions in Assessing Sleep Continuity. Sleep 2010, 33, 1681–1686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrell, M.J.; Finn, L.; Kim, H.; Peppard, P.E.; Badr, M.S.; Young, T. Sleep Fragmentation, Awake Blood Pressure, and Sleep-Disordered Breathing in a Population-based Study. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2000, 162, 2091–2096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silverman, I.W. Sex Differences in Simple Visual Reaction Time: A Historical Meta-Analysis. Sex Roles 2006, 54, 57–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- E Beaudin, A.; Younes, M.; Gerardy, B.; Raneri, J.K.; Allen, A.J.M.H.; Gomes, T.; Gakwaya, S.; Sériès, F.; Kimoff, J.; Skomro, R.P.; et al. Association between sleep microarchitecture and cognition in obstructive sleep apnea. Sleep 2024, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djonlagic, I.E.; Guo, M.; Igue, M.; Kishore, D.; Stickgold, R.; Malhotra, A. Continuous Positive Airway Pressure Restores Declarative Memory Deficit in Obstructive Sleep Apnea. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2021, 203, 1188–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benkirane, O.; Simor, P.; Mairesse, O.; Peigneux, P. Sleep Fragmentation Modulates the Neurophysiological Correlates of Cognitive Fatigue. Clocks Sleep 2024, 6, 602–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Long, N.M.; Kuhl, B.A. Bottom-Up and Top-Down Factors Differentially Influence Stimulus Representations Across Large-Scale Attentional Networks. J. Neurosci. 2018, 38, 2495–2504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, C.; Bianchi, M.T.; Yun, C.-H.; Shin, C.; Thomas, R.J. Multicomponent Analysis of Sleep Using Electrocortical, Respiratory, Autonomic and Hemodynamic Signals Reveals Distinct Features of Stable and Unstable NREM and REM Sleep. Front. Physiol. 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halassa, M.M.; Sherman, S.M. Thalamocortical Circuit Motifs: A General Framework. Neuron 2019, 103, 762–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang-Xie, L.-F.; Drieu, A.; Bhasiin, K.; Quintero, D.; Smirnov, I.; Kipnis, J. Neuronal dynamics direct cerebrospinal fluid perfusion and brain clearance. Nature 2024, 627, 157–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, R.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, L.; Somers, V.K.; Covassin, N.; Tang, X.; 22. Association Between Arousals During Sleep and Hypertension Among Patients With Obstructive Sleep Apnea. J. Am. Hear. Assoc. 2022, 11, e022141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |